Abstract

Bacteriophage T7 DNA polymerase (gene 5 protein, gp5) interacts with its processivity factor, Escherichia coli thioredoxin, via a unique loop at the tip of the thumb subdomain. We find that this thioredoxin-binding domain is also the site of interaction of the phage-encoded helicase/primase (gp4) and ssDNA binding protein (gp2.5). Thioredoxin itself interacts only weakly with gp4 and gp2.5 but drastically enhances their binding to gp5. The acidic C termini of gp4 and gp2.5 are critical for this interaction in the absence of DNA. However, the C-terminal tail of gp4 is not required for binding to gp5 when the latter is bound to a primer/template. We propose that the thioredoxin-binding domain is a molecular switch that regulates the interaction of T7 DNA polymerase with other proteins of the replisome.

Keywords: DNA replication, molecular switch, replisome, gene 4 protein, thioredoxin

The replication fork of bacteriophage T7 (Fig. 1) can be reconstituted by using only four proteins (1). Polymerization of nucleotides is carried out by T7 DNA polymerase, a 1:1 complex (KD = 5 nM) of gene 5 protein (gp5) and its processivity factor, Escherichia coli thioredoxin (2). The helicase and primase activities reside in the same polypeptide chain, the gene 4 protein (gp4) (1). The helicase activity, required for unwinding the parental DNA strand, is located in the C-terminal half, and the primase activity, required to initiate lagging-strand DNA synthesis, is located in the N-terminal half (3, 4). Gene 2.5 protein (gp2.5), the ssDNA-binding protein, coats ssDNA and interacts with other replication proteins (5, 6).

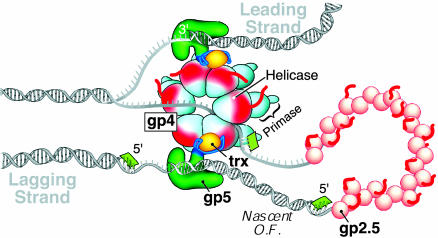

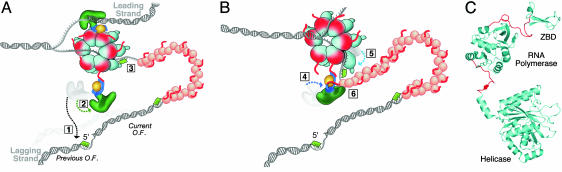

Fig. 1.

Model of the replication fork of phage T7. The replisome consists of DNA polymerase (gp5), the processivity factor thioredoxin (trx), the hexameric helicase/primase (gp4), and the ssDNA-binding protein (gp2.5). The leading strand is extended continuously by gp5/trx in association with gp4, whose helicase domain is responsible for unwinding the duplex DNA. The ssDNA (lagging strand) extruded behind the helicase is coated by gp2.5. The polarity of lagging-strand synthesis is aligned with synthesis of the leading strand through loop formation. Another gp5/trx, tethered to the hexameric gp4, synthesizes the replication of Okazaki fragments (O.F.) that are initiated by RNA primers (in green), which are synthesized by the primase domain of gp4. The acidic C termini of gp4 and gp2.5 are shown schematically as red tails.

The four proteins are sufficient to form a replisome that mediates leading- and lagging-strand synthesis in a coordinated manner (7, 8). Synthesis of the two strands is coupled because inhibition of synthesis on one strand leads to inhibition on the other (8). Whereas the leading strand is synthesized continuously, the lagging strand is synthesized in a discontinuous manner, giving rise to multiple Okazaki fragments with an average length of 3,000 nt (Fig. 1) (8, 9). The lagging-strand polymerase recycles from one completed Okazaki fragment to the next primer without dissociation (8). Electron microscopy has revealed the presence of replication loops on the lagging strand that contain nascent Okazaki fragments (Fig. 1) (9).

Physical interactions between the proteins at the replication fork coordinate their activities to achieve coupled DNA synthesis. Thioredoxin binds to a unique 76-aa loop (thioredoxin-binding domain, TBD) between helices H and H1 in the thumb subdomain of gp5 (Fig. 2). Thioredoxin confers processivity on gp5 presumably by ordering the TBD such that its basic residues point toward the DNA binding crevice (Fig. 2) (10). The presence of the T7 helicase and primase within a single gp4 polypeptide offers several advantages. The covalent association insures both translocation of the primase and its immediate access to the ssDNA generated behind the translocating helicase (Fig. 1). The tight binding of the hexameric helicase to ssDNA enhances the low affinity of the primase for DNA (11). Gp4 interacts with the gp5/thioredoxin complex (gp5/trx), and this interaction is essential for the coordination of DNA unwinding and nucleotide polymerization on duplex DNA (12). In additional, the zinc-binding domain (ZBD) of the primase domain of gp4 assists in the positioning of the primer in the active site of gp5/trx (13). Gp2.5 interacts with both gp5/trx and gp4 to stimulate DNA and primer synthesis, respectively (6, 14).

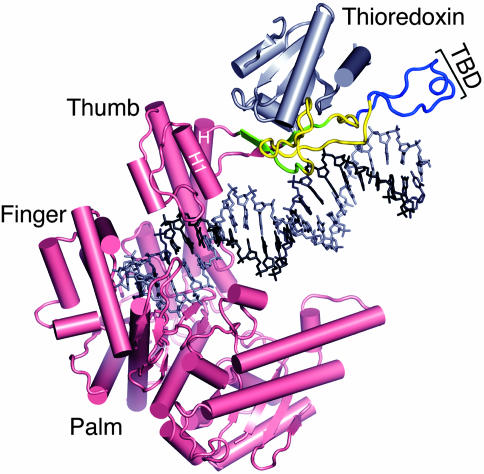

Fig. 2.

Crystal structure of T7 gp5/trx bound to its primer/template and an incoming nucleotide (32). Gp5 is shown in pink, and thioredoxin is shown in gray. The DNA is depicted as sticks with the template in black and the primer in gray. Thioredoxin binds to a unique 76-residue loop between helices H and H1. The three deletions in the TBD discussed in this article are indicated either in blue (Δ297–318), blue and yellow (Δ271–324), or blue, yellow, and green (Δ264–328).

Both gp4 and gp2.5 have acidic C termini through which they interact with gp5 (12, 15). Among the C-terminal 21 residues of gp4 and gp2.5, 7 and 15 residues, respectively, are acidic. The C termini of gp4 and gp2.5 share no sequence homology and are most likely unstructured; gp2.5 only crystallized when the C terminus was deleted (16), and in the crystals of gp4 the C terminus did not diffract (17). Deletion of the C terminus of gp4 (12) or gp2.5 (15) eliminates their ability to interact with gp5/trx.

Most replicative DNA polymerases belong to either the polymerase II or III family. DNA polymerases in these families function within multiprotein complexes (18), with accessory subunits maintaining several interactions between the holoenzyme and other replication proteins (19). In contrast, T7 DNA polymerase, a member of the polymerase I family, interacts directly with other replication proteins, yet nonetheless performs coordinated DNA synthesis. We demonstrate that the center of these interactions resides within the unique TBD, which not only is important in the interaction with thioredoxin and primer/template, but also provides at least one site of interaction of the polymerase with gp4 and gp2.5.

Materials and Methods

Mutagenesis of T7 Gene 5. Three mutants of T7 gene 5 were constructed in which 66, 162, and 195 nt in the sequence encoding the TBD were deleted. The amino acid residues deleted in each case were 297–318 (gp5Δ22), 271–324 (gp5Δ54), and 264–328 (gp5Δ65). Mutagenesis was carried out by using PCR to obtain the desired deletions in the gene 5 plasmid pGP5-3 (2). The identity of all clones was confirmed by using DNA sequencing.

Gene Expression and Purification of Proteins. Gp5 and the three deletion mutants were overproduced in E. coli strain A307(DE3) (20) and then purified as described (2). The 63-kDa gp4 and the gp4 missing 17 residues from the C terminus (gp4-CΔ17) were purified as described (12). His-tagged gp4E (residues 272–566) was purified as described (4). His-tagged gp2.5 and His-tagged gp2.5 lacking the 26 C-terminal residues (gp2.5-Δ26C) were purified, and the His tags were removed as described (21). Thioredoxin was purified as described (2).

Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR). SPR analysis was performed by using a Biacore-3000 instrument (Biacore, Uppsala, Sweden). Sensor chips and coupling reagents were from Biacore. Protein coupling via primary amine groups to the carboxymethyl-5 chip (CM-5) was performed according to the manufacturer's instructions at a flow rate of 5 μl/min. The following proteins were coupled to the matrix by injecting them under the following conditions: gp4 and gp4-CΔ17 at 125 μg/ml in 10 mM Na-acetate (pH 5.0) and 10 mM MgCl2, gp4E at 30 μg/ml in 10 mM Na-acetate (pH 5.5), and gp2.5 and gp2.5-CΔ26 at 15 μg/ml in 10 mM Na-acetate (pH 5.0). A control flow cell was activated and blocked in the absence of protein to subtract the response units (RU) resulting from nonspecific interactions and bulk refractive index. Binding studies were performed at 20°C at a flow rate of 40 μl/min in buffer A [20 mM Hepes, pH 7.5/10 mM MgCl2/5 mM DTT/250 mM K-glutamate/0.005% (vol/vol) Tween 20]. The chip surface was regenerated by using two injections of 100 μl of buffer A containing 1.5 M NaCl at 100 μl/min. Gp5/trx was formed by incubating gp5 with thioredoxin at a 1:40 molar ratio at 20°C for 20 min followed by 0°C for ≈2 h. The observed dissociation binding constant, KD, was calculated by using the average RU under steady-state conditions. Data were fitted by using the steady-state model provided by biaeval 3.0.2 computational software (Biacore).

To investigate the binding of gp4 and gp2.5 to gp5/trx in the presence of a primer/template, biotinylated DNA was coupled to a streptavidin-coated chip. Two template strands were used that contained a biotin group attached to either the 5′ or 3′ end (5′-biotin-TTCCCCCTTGGCACTGGCCGTCGTTTTCACG-3′ and 5′-CCCCCTTGGCACTGGCCGTCGTTTTCACGTT-biotin-3′). A primer strand (5′-CGTGAAAACGACGGCCAGTGCCA-3′) was annealed to each of the template strands. Equal amounts of the two duplex DNAs were coupled at a concentration of 0.25 μM in HBS-P buffer [10 mM Hepes, pH 7.4/150 mM NaCl/0.005% (vol/vol) Tween 20] at a flow rate of 10 μl/min. Free streptavidin on the flow cells was then blocked by washing with biotin. Binding studies were carried out in buffer B [20 mM Hepes, pH 7.5/5 mM MgCl2/2.5 mM DTT/200 mM K-glutamate/1% (wt/vol) glycerol/0.5 mM dGTP] at a flow rate of 10 μl/min. Gp5/trx was passed over the chip at 0.25 μM in buffer B containing 10 μM 2′,3′-dideoxy-ATP and 1 mM dGTP, to incorporate the dideoxynucleotide at the 3′ end of the primer strand. To prevent hydrolysis of DNA by the 3′ to 5′ exonuclease activity associated with gp5, a mutant protein was used in which residues Asp-5 and Asp-65, both located in the exonuclease active site (10), were changed to Ala. Gp4 and gp2.5 were injected over the chip in buffer B containing 0.1 mM ATP and 2 mM dGTP. As a control, a flow cell blocked with biotin was used to measure the nonspecific interaction and bulk refractive index of the sample buffer containing either the gp4 or gp2.5 variants. The chip surface was stripped of bound proteins by using three sequential injections of 150 μl of 1 M NaCl, 100 μl of 0.025% SDS, and 100 μl of 0.035% SDS at a flow rate of 100 μl/min. The stoichiometry of the binding of gp5/trx to the primer/template and to gp4 and gp2.5 was calculated according to Eq. 1:

|

[1] |

where Rmax is the maximum response during injection (under saturating binding conditions), MrA and MrL are the molecular weights of the injected protein (analyte) and the immobilized material (ligand), respectively, RI is the response unit from the immobilized material, and N is the stoichiometry of the binding, which represents the number of molecules of analyte bound to each molecule of ligand.

Results

Characterization of the Binding of Gp4 to Gp5/trx. We have used SPR to measure the interaction of gp4 with gp5/trx. In the experiment presented in Fig. 3, gp4 was immobilized via its amine groups to the sensor chip CM-5. When gp5/trx is injected over the immobilized gp4 (Fig. 3A), it associates rapidly with gp4 as evidenced by the sharp increase in RU at the start of injection. After an initial rapid decrease in RU at the end of injection, there is a second phase involving a slow decrease in RU. This later phase is indicative of a tight binding of gp4 and gp5/trx. The binding of gp5/trx to gp4 depends on the C-terminal tail of gp4; no interaction is detected when gp4 is replaced by gp4 lacking its C-terminal 17 residues (gp4-CΔ17) (Fig. 3B). This result is in agreement with an earlier observation with SPR and mobility-shift assays that gp5/trx did not bind to gp4-CΔ17 bound to DNA (12).

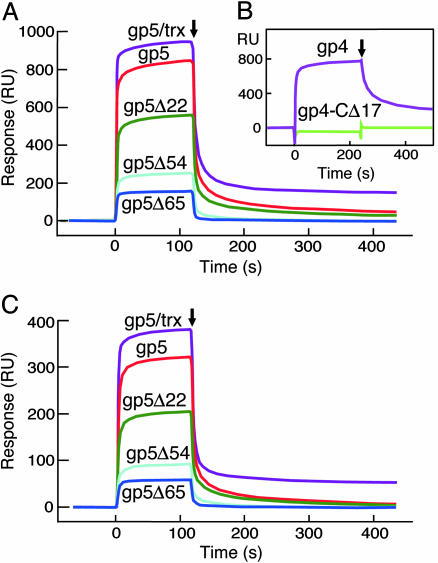

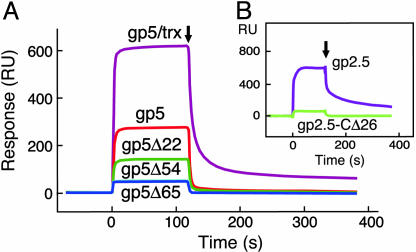

Fig. 3.

Binding of gp5 to gp4. In all cases gp4 was immobilized via its amine groups to the sensor chip CM-5, and gp5 variants were flowed over the immobilized gp4. Binding studies were carried out as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Binding of gp5/trx, gp5, gp5Δ22, gp5Δ54, and gp5Δ65 to gp4. A total of 2,800 RU of gp4 was coupled to the chip, and the concentration of the gp5 variants in the flow buffer was 0.5 μM. The coupling step is omitted and baseline was adjusted to zero. The end of injection is indicated by an arrow. (B) Binding of gp5/trx to gp4 or gp4-CΔ17. Either 7,800 RU of gp4 or 5,300 RU of gp4-CΔ17 were coupled to two different flow cells, and the concentration of gp5/trx was 0.25 μM. (C) Binding of gp5/trx, gp5, gp5Δ22, gp5Δ54, and gp5Δ65 to gp4E. A total of 750 RU of gp4E was coupled to the chip, and the concentration of each of the gp5 variants was 0.5 μM.

Comparison of the binding of gp5 and gp5/trx to gp4 reveals that both have fast on rates (Fig. 3A). This conclusion is based on the similarity of the shapes of their sensograms during injection and the plateau values of the total RU; the value with gp5/trx is 13% larger than gp5 alone because of its larger mass. The off rates of the two proteins are remarkably different. Gp5/trx interacts more tightly, as reflected by the larger amount of bound protein at the end of injection and the slower rate of dissociation; fitting the rate of signal decay from the slow dissociation phase at the end of injection in Fig. 3A gives a kd value of 0.7 × 10–3 s–1 for gp5/trx and 2.8 × 10–3 s–1 for gp5. The interaction of gp4 with both gp5/trx and gp5 is electrostatic, because the amount of bound protein decreases with increasing salt concentration (data not shown).

TBD of Gp5 Is Essential for Interaction with Gp4. The increase in stability of the binding of gp5 to gp4 conferred by thioredoxin suggests that thioredoxin and/or the TBD has a role in this interaction. To examine the role of the TBD, we constructed three altered gp5s (gp5Δ22, gp5Δ54, and gp5Δ65) that have deletions of 22, 54, and 65 residues, respectively, in the 76-residue TBD (Fig. 2). None of the mutants could complement the growth of T7 phage lacking gene 5 (data not shown). Purified gp5Δ22, gp5Δ54, and gp5Δ65 retained 50%, 33%, and 25%, respectively, of the polymerase activity of gp5 when assayed on primed M13 DNA (data not shown). Because the altered gp5s retained polymerase activity, we conclude that they all folded properly. We anticipate that the gradual loss of activity is caused by the role of the TBD in increasing the processivity of gp5. The polymerase activities of gp5Δ54 and gp5Δ65 on primed M13 DNA were not stimulated by the presence of thioredoxin, whereas thioredoxin stimulated the activity of gp5Δ22 with an apparent KM that is 15-fold higher than that of gp5 (data not shown).

The affinities of the interactions between gp4 and the three gp5 deletion mutants were compared by using SPR (Fig. 3A). Although all three proteins bind gp4, the strength of the association decreases with increasing deletion of the TBD. The decrease in RU during injection of the gp5 proteins is much greater than that predicted from the decrease in mass of the deletion proteins. The off rates of the mutant gp5s indicate that all had markedly lower affinity to gp4 than did gp5, with only gp5Δ22 binding stably to gp4.

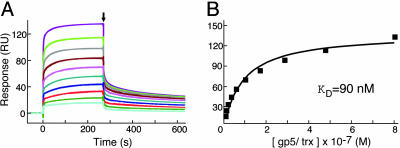

For quantitative kinetic analysis of the binding, we used a genetically altered gp4 that cannot oligomerize. Gp4E is a 36-kDa C-terminal fragment that lacks the primase domain and a linker region essential for oligomerization (4). Previous studies using SPR showed that gp5/trx binds to gp4E and the WT gp4 (4). As shown in Fig. 3C, the sensograms obtained with gp4E are nearly identical to those obtained with WT gp4. We measured the binding of gp5/trx to gp4E by using different concentrations of gp5/trx (Fig. 4A). Because the data could not be fitted as a 1:1 Langmuir binding mode, we used a steady-state analysis to calculate an observed dissociation binding constant, KD, of 90 nM (Fig. 4B and Table 1). We carried out the same analysis to determine the KD between gp4E and gp5 in the absence of thioredoxin to be 370 nM; this result is four times higher than that in the presence of thioredoxin (Table 1). As discussed earlier, this difference can be attributed to the difference in the stability of the interaction, kd, rather than to the association step, ka. Gp5Δ65 binds to gp4E with a KD of 8,200 nM, weaker than that of gp5/trx by a factor of 90 (Table 1). This weaker binding is the result of large differences in both the ka and kd (Fig. 3A). The effect of deleting the TBD is not solely caused by the inability of gp5Δ65 to bind thioredoxin because gp5Δ65 binds to gp4E 20-fold less tightly than does gp5 (Table 1).

Fig. 4.

KD determination of the binding of gp5/trx to gp4E. Two hundred RU of Gp4E was immobilized on a CM-5 chip, and then the gp5/trx was flowed over the chip. (A) Sensograms of the binding of increasing concentrations of gp5/trx to gp4E. The concentrations of gp5/trx used were 10, 15, 20, 40, 60, 100, 170, 290, 480, and 800 nM. (B) KD determination of the binding of gp5/trx to gp4E. Data points represent the equilibrium average response for the last 10 s of the injection in each of the experiments shown in A, where steady-state conditions have been obtained. The solid line represents the theoretical curve calculated from the steady-state fit model provided by biaeval 3.0.2 computational software (Biacore).

Table 1. Binding of gp5 and thioredxin to gp4 and gp2.5.

|

KD, nM

|

||

|---|---|---|

| Protein | gp4E | gp2.5 |

| gp5/trx | 90 | 130 |

| gp5 | 370 | 1600 |

| gp5Δ65 | 8200 | 45,000 |

| Thioredoxin | 130,000 | 500,000 |

KD values of the binding of the proteins indicated were determined as described in Fig. 4. The binding curves are provided in Figs. 9-11, which are published as supporting information on the PNAS web site.

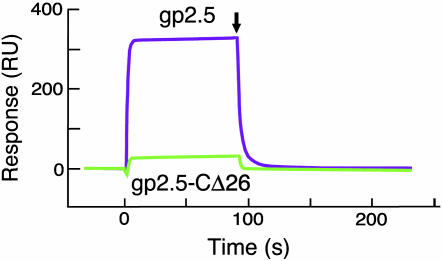

TBD of Gp5 Is Essential for Interaction with Gp2.5. The interaction of gp5/trx with gp2.5 coupled via its amine groups to a CM-5 chip is shown in Fig. 5A. Using steady-state analysis, the KD for the interaction of gp2.5 and gp5/trx is calculated to be 130 nM (Table 1). Deletion of the acidic 26-residue C-terminal tail of gp2.5 (gp2.5-CΔ26) dramatically reduces its affinity for gp5/trx (Fig. 5B). These results are in agreement with earlier observations with fluorescence anisotropy, affinity chromatography, and SPR assays, which show that gp5/trx is defective in binding gp2.5 lacking its C terminus (15, 21).

Fig. 5.

Binding of gp5/trx to gp2.5. In all cases, gp2.5 was immobilized on a CM-5 chip, and the gp5 variants were flowed over. (A) Binding of gp5/trx, gp5, gp5Δ22, gp5Δ54, and gp5Δ65 to gp2.5. Five hundred fifty RU of gp2.5 was coupled to the chip, and the concentration of the gp5 variants was 0.5 μM. (B) Binding of gp5/trx to gp2.5 and gp2.5-CΔ26. Four hundred RU of gp2.5 and gp2.5-CΔ26 was coupled to two different flow cells, and the concentration of gp5/trx was 0.5 μM.

Thioredoxin enhances the binding of gp2.5 to gp5 (Fig. 5A). The KD of gp2.5 and gp5 (1,600 nM) is 13-fold higher than that observed for gp5/trx (Table 1). The gp5s with deletions of 22, 54, and 65 residues in the TBD showed lowered affinities for gp2.5; e.g., the KD of gp5Δ65 and g2.5 is 45,000 nM (Fig. 5A and Table 1). Thus deletion of the TBD results in a greater reduction in binding to gp2.5 than does the absence of thioredoxin.

Thioredoxin Interacts Weakly with Gp2.5 and Gp4. In view of the higher affinity of both gp2.5 and gp4 for gp5 in the presence of thioredoxin, we assessed the ability of thioredoxin to interact directly with these proteins. Using a sensor chip containing immobilized gp2.5, we find that thioredoxin binds weakly (Fig. 6); no stable binding was detected at the end of the injection. With steady-state analysis, the KD value is 500 μM (Table 1). The binding to thioredoxin depends on the acidic C terminus of gp2.5, because the binding is much weaker to gp2.5-CΔ26 (Fig. 6). Similar results were obtained by using immobilized gp4E (data not shown) with a KD for binding thioredoxin calculated to be 130 μM (Table 1).

Fig. 6.

Binding of thioredoxin to gp2.5. Gp2.5 and gp2.5-CΔ26 were coupled to two different flow cells on a CM-5 chip, and then thioredoxin was flowed over at a concentration of 400 μM.

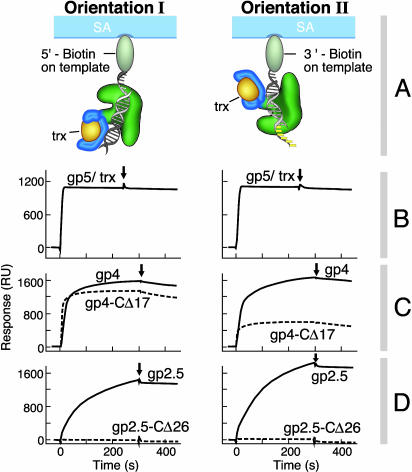

Effect of DNA on the Interaction of Gp4 and Gp5/trx. The binding of DNA to gp5 during DNA synthesis requires electrostatic interactions between the TBD and the duplex portion of the DNA (Fig. 2). Therefore, it seemed likely that the interactions of gp5/trx with gp4 and gp2.5 would be modulated when gp5/trx is bound to a primer/template. We formed a stable complex of gp5/trx, a primer/template, and a dNTP, as described for obtaining stable complexes for crystallization (10). Gp5/trx forms a stable complex with a primer/template in which the primer strand is terminated by 2′,3′-dideoxynucleotide (ddAMP in this experiment), provided the next dNTP specified by the template (dGTP in this experiment) is present. We used two primer/templates that allow the polymerase to bind in opposite orientations, in the event the proximity of gp5/trx to the chip might hinder its interactions (Fig. 7A).

Fig. 7.

Binding of gp4 and gp2.5 to a gp5/trx–primer/template. In all cases, the primer/template strand was immobilized on the chip, then gp5/trx was flowed over the chip, followed by the gp4 or gp2.5 variants. Binding studies were carried out as described in Materials and Methods.(A) Schematic of the two orientations of the biotinylated primer/template bound to a streptavidin (SA)-coated sensor chip and the resulting orientation of the gp5/trx. In orientation I, biotin is coupled to the 5′ end of the template. In orientation II, biotin is coupled to the 3′ end of the template. (B) Gp5/trx forms a stable complex with the primer/template. Two hundred RU of each biotinylated primer/template was coupled to two different flow cells on a SA-coated chip, resulting in the orientations shown in A. Gp5/trx was injected at a concentration of 0.25 μM in a flow buffer containing 1 mM dGTP and 10 μM 2′,3′-dideoxy-ATP. The 200 RU resulting from the coupling of the primer/template was subtracted from the baseline. (C) Binding of gp4 and gp4-CΔ17 to flow cells containing the gp5/trx–primer/template in the two orientations shown in A. The gp5/trx binding step to the biotinylated primer/template shown in B was omitted for clarity and subtracted from the baseline. The concentrations of gp4 and gp4-CΔ17 were 0.8 μM (expressed as monomers) in flow buffer containing 0.1 mM ATP and 2 mM dGTP. (D) Binding of gp2.5 and gp2.5-CΔ26 to flow cells containing the gp5/trx–primer/template in the two orientations shown in A. The concentrations of gp2.5 and gp2.5-CΔ26 were 3.5 μM (expressed as monomers) in flow buffer containing 0.1 mM ATP and 2 mM dGTP.

A total of 1,100 RU of gp5/trx (91.4 kDa) were assembled onto 200 RU of the primer/template bound to the chip (17.5 kDa) (Fig. 7B). This ratio of RU of gp5/trx to primer/template corresponds to a saturating 1:1 binding according to Eq. 1, as described in Materials and Methods. Under these conditions, gp5/trx forms an extremely stable complex that is independent of the orientation of the primer/template. The complex depends on the next incoming nucleotide, dGTP (data not shown). In other control experiments, neither gp4, gp4-CΔ17, gp2.5, nor gp2.5-CΔ26 bound to the primer/template in the absence of gp5/trx (data not shown).

Gp4 binds remarkably tightly to the gp5/trx–primer/template complex, as evidenced by the initial rapid rise in RU and the high stability of the complex in the dissociation phase (Fig. 7C). This binding is independent of the orientation of the polymerase. Although the data in Fig. 7C show the binding of hexameric gp4, we also observe strong binding with the monomeric gp4E (data not shown). Surprisingly, gp4-CΔ17, which does not bind to gp5/trx in the absence of DNA, binds with strong affinity to the gp5/trx–primer/template complex (Fig. 7C). The association, but not the dissociation, of the binding of gp4-CΔ17 to the gp5/trx–primer/template depends on the orientation of the polymerase. Gp2.5 binds well to the gp5/trx–primer/template complex in either orientation (Fig. 7D). Although gp2.5 forms a stable complex, comparable to that observed with gp4, its association is slower. The acidic C-terminal tail of gp2.5 is essential for this binding; no binding is observed with gp2.5-CΔ26 in either orientation.

We have calculated the stoichiometry of binding of gp4 and gp2.5 to the gp5/trx–primer/template complex by using Eq. 1 (Table 2, which is published as supporting information on the PNAS web site). At saturation, a monomer of gp5/trx binds six monomers of gp4. Because the native form of gp4 under these conditions is a hexamer, we conclude that one hexamer of gp4 binds to one gp5/trx molecule. At saturation a monomer of gp5/trx binds six monomers of gp2.5. This finding is in disagreement with the previously reported 1:1 stoichiometry of gp5/trx and gp2.5 observed using fluorescence anisotropy (6). One possibility is that under the conditions used here the gp2.5 is interacting with itself to form higher oligomers.

Discussion

We demonstrate here that in the absence of DNA both gp4 and gp2.5 interact with the basic TBD of gp5 via their acidic C-terminal regions. Although these studies do not address the specificity of the binding of the C termini, they raise the possibility of overlapping binding sites. Of the C-terminal 21 residues of E. coli ssDNA binding protein and T4 gene 32 protein, 5 and 6 residues, respectively, are acidic. Replacing the 21 residues of gp2.5 with the C-terminal tails of E. coli ssDNA binding protein or gene 32 protein yields chimeras that physically interact with gp5/trx, albeit weaker than gp2.5 (22). This result suggests that the acidic charge of the termini is the predominant factor in binding.

The presence of thioredoxin increases the affinity of gp5 for both gp4 and gp2.5. Thioredoxin binds gp4 and gp2.5 directly but far too weakly to account for the stimulation observed. More likely, thioredoxin leads to conformational changes in the TBD that allow gp4 and gp2.5 to bind more avidly. A second possibility is that the binding between thioredoxin and the TBD is cooperative. When gp5/trx is bound to a primer/template, the binding of gp2.5 but not gp4 requires its C-terminal tail. Gp4 binding requires the helicase domain; no interaction was detected between gp5/trx–primer/template and the primase domain alone (S.M.H. and C.C.R., unpublished results). Nevertheless, the acidic C terminus of gp4 has an important role in stimulating gp5/trx polymerase activity on duplex template, because gp4-CΔ17 is unable to substitute for gp4 in this reaction (12). When the TBD is in close proximity to the chip, gp4-CΔ17, but not gp4, has deficiency in associating with gp5/trx, suggesting an importance of the C terminus of gp4 in the initial binding step. We propose that the C terminus provides a site to electrostatically maintain the polymerase in close proximity to the helicase when they lose contact during DNA synthesis. It is not clear whether the binding of gp5/trx to gp4 in the presence of primer/template involves the highly basic TBD and/or thioredoxin. We were unable to bind any of the altered gp5s onto the primer/template, which would have addressed this question. However, it is reasonable to assume that the binding is to the highly basic TBD, because the entire C-terminal surface of gp4 is highly acidic (23). In addition, preliminary results indicate that some point mutations in the TBD disrupt its interaction with gp4 and the ability of the complex to carry out strand displacement DNA synthesis on duplex DNA.

An acidic C terminus is a common feature of all ssDNA binding proteins. Deletion of the acidic C terminus of T4 gp32 protein eliminates its ability to interact with both the T4 DNA polymerase and primase (24–26). Deletion of the acidic C terminus of E. coli ssDNA binding protein eliminates its ability to interact with the χ-subunit of DNA polymerase III (27). On the other hand, not all of the C-terminal tails of the DnaB family of helicases are acidic. E. coli DnaB and T4 gene 41 proteins have only four and three acidic residues, respectively, in their C-terminal 17 residues. Because E. coli DnaB and T4 gene 41 proteins interact with their DNA polymerases via an accessory protein, one possibility is that helicases have acidic C termini only in systems where they interact directly with their polymerases. Interestingly, domain IV of the τ-subunit of E. coli DNA polymerase III, which interacts with E. coli DnaB protein, is highly basic (28), a property shared by the TBD of gp5. This finding suggests that the binding site on E. coli DnaB protein for the τ-subunit is acidic. We predict that such electrostatic interactions are a universal feature of helicases and polymerases at replication forks.

Our current model of the T7 replisome is shown in Fig. 1. Leading- and lagging-strand DNA polymerases are each bound tightly to a processivity factor, thioredoxin. Gp4 assembles as a hexamer with its C-terminal helicase domain facing the fork and the N-terminal primase domain in a position to recognize primase sites on the displaced strand. Gp5/trx interacts with gp4 via interactions that reside in the C-terminal helicase domain but do not require the C-terminal tail for stable binding. On the other hand, the C terminus of gp4 is required for processive DNA synthesis by gp5/trx on duplex DNA (12). Lagging-strand synthesis requires the initiation of Okazaki fragments every ≈3,000 nt (9). Once synthesized, the primer must be transferred to the lagging-strand DNA polymerase via the ZBD of the primase domain of gp4 (13) in a process that requires the polymerase to dissociate from the completed Okazaki fragment without leaving the replisome (8). We propose that the lagging-strand DNA polymerase, upon completing an Okazaki fragment, dissociates from the DNA but remains tethered via its TBD to the flexible acidic C terminus of the helicase domain of gp4 (Fig. 8A). Once released from the primer/template, the highly flexible contact between the TBD and the C terminus of gp4 allows gp5/trx to swing toward the N-terminal primase domain in search of the ZBD and the newly synthesized primer (Fig. 8A). The stability of this complex may be aided by contacts between the TBD and gp2.5 (Fig. 8B). Moreover, the flexible segments linking the catalytic core of the primase domain to its ZBD (13) and the helicase domain (29) (Fig. 8C) allow for movement of the ZBD and its primer to meet the approaching gp5/trx (Fig. 8B).

Fig. 8.

Model for the recycling of lagging-strand DNA polymerase. The components of the T7 replisome are described in Fig. 1. (A) The lagging-strand DNA polymerase interacts with the C-terminal region of gp4 during primer delivery. The lagging-strand DNA polymerase synthesizes an Okazaki fragment (Current O.F.) until it reaches the 5′ end of the previously synthesized Okazaki fragment (Previous O.F.). At this point, the polymerase dissociates from the primer/template (number 1). Dissociation results in a conformational change in the TBD that favors its interaction with the C-terminal tail of gp4 (number 2). Before the interaction shown in step number 2, the lagging-strand DNA polymerase interacts with gp4 in no C-terminal dependent fashion as depicted in Fig. 1. A new tetraribo-nucleotide primer is synthesized by the primase domain and held by the ZBD (see C) (number 3). (B) Recycling of the lagging-strand polymerase. The flexible binding of the polymerase via the TBD to the C-terminal tail of gp4 allows it to search for a new primer located in the N-terminal region of gp4 (number 4). Flexible segments linking the catalytic core of the primase domain to its ZBD and the helicase domain (see C) allow for movement of the ZBD and bound primer to contact the approaching gp5/trx (number 5). Gp2.5 binds to the TBD to assist the union of the polymerase and the ZBD (number 6). (C) Flexible linker regions connect subdomains in gp4. This structural model of monomeric full-length gp4 was generated by overlaying the RNA polymerase catalytic domains from the crystal structures of the primase fragment (13) and a monomer of helicase/primase that lacks the ZBD (29). The linker regions connecting the RNA polymerase domain with the ZBD and helicase domain are shown in red.

The TBD has a unique position at the replication fork. The interaction of the TBD with thioredoxin leads to a conformational change in the TBD that allows its basic residues to bind to the duplex portion of the primer/template and confer processivity on the reaction. However, when gp5/trx loses its contact with the primer/template, we propose that the TBD is now able to interact with gp4 in a mode that differs from the interaction during polymerization. Thus, based on this model the TBD functions as a DNA sensor and a molecular switch that regulates its interaction with gp4 and gp2.5 based on whether or not it is bound to the primer/template. During processive polymerization, the interaction of gp5/trx with gp4 does not require the C terminus of gp4. However, upon dissociation from the primer/template, e.g., when an Okazaki fragment is completed, the TBD becomes free to interact with the acidic C terminus of gp4 or gp2.5. These latter interactions assure the retention of the lagging-strand DNA polymerase within the replisome and assist in delivery of the polymerase to the ZBD and a new primer.

On the lagging strand, the polymerase must repeatedly loosen its grip to initiate the synthesis of the next Okazaki fragment. For DNA polymerases that use a sliding clamp as a processivity factor, the critical step is dissociation from the clamp. In the case of E. coli, regulation of this process resides in the C-terminal region of the polymerase accessory subunit τ. Upon reaching the nick resulting from a completed Okazaki fragment, it displaces the β-clamp from the polymerase subunit α (30), and a set of three step switches delivers the polymerase to the next primer (31). During primer delivery, the binding of the polymerase subunit to the helicase occurs via a highly basic, flexible domain at the C terminus of τ (28). In the case of gp5/trx, it is likely that processivity involves electrostatic interactions of basic residues in the TBD with the DNA phosphate backbone. Dissociation of the polymerase at nicked DNA thus is likely to occur without the dissociation of thioredoxin. The challenge for gp5/trx during primer delivery is to maintain binding to gp4 while locating the ZBD–primer complex. We propose that the TBD is the phage T7 equivalent of the E. coli τ protein, and it regulates interactions relating to primer utilization in accordance with the status of a complete or incomplete Okazaki fragment. According to this model, the key step in each case is regulated by a protein that senses the status of DNA synthesis and switches the activity of the lagging-strand DNA polymerase from an elongation mode into a primer delivery mode via changes in the protein–protein interactions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Donald Johnson (Harvard Medical School) for E. coli A307(DE3), Ying Li (Harvard Medical School) for the initial gp4E sample and help with Fig. 8C, Luis Brieba for help with Fig. 2, Jaya Kumar for thoughtful discussions and critical reading of the manuscript, Thomas Vorup-Jenson for help with SPR data analysis and critical reading of the manuscript, and Steven Moskowitz (Advanced Medical Graphics, Boston) for illustrations. This work was supported in part by Public Health Service Grant GM-54397 and Department of Energy Grant DE-FG02-96ER62251. B.M. was funded by National Institutes of Health Postdoctoral Fellowships ST32A107245-20 and F32GM72305.

Author contributions: S.M.H., S.T., and C.C.R. designed research; S.M.H., B.M., and S.T. performed research; S.M.H., T.C., and S.-J.L. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; S.M.H. analyzed data; and S.M.H., S.T., and C.C.R. wrote the paper.

Abbreviations: TBD, thioredoxin-binding domain; gp2.5, gene 2.5 protein; gp4, gene 4 protein; gp5, gene 5 protein; gp5/trx, gp5/thioredoxin complex; ZBD, zinc-binding domain; SPR, surface plasmon resonance; RU, response units.

References

- 1.Richardson, C. C. (1983) Cell 33, 315–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tabor, S., Huber, H. E. & Richardson, C. C. (1987) J. Biol. Chem. 262, 16212–16223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frick, D. N., Baradaran, K. & Richardson, C. C. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 7957–7962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guo, S. Y., Tabor, S. & Richardson, C. C. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 30303–30309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim, Y. T., Tabor, S., Bortner, C., Griffith, J. D. & Richardson, C. C. (1992) J. Biol. Chem. 267, 15022–15031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim, Y. T., Tabor, S., Churchich, J. E. & Richardson, C. C. (1992) J. Biol. Chem. 267, 15032–15040. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Debyser, Z., Tabor, S. & Richardson, C. C. (1994) Cell 77, 157–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee, J., Chastain, P. D., Kusakabe, T., Griffith, J. D. & Richardson, C. C. (1998) Mol. Cell 1, 1001–1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee, J., Chastain, P. D., Griffith, J. D. & Richardson, C. C. (2002) J. Mol. Biol. 316, 19–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doublie, S., Tabor, S., Long, A. M., Richardson, C. C. & Ellenberger, T. (1998) Nature 391, 251–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frick, D. N. & Richardson, C. C. (2001) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 70, 39–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Notarnicola, S. M., Mulcahy, H. L., Lee, J. & Richardson, C. C. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 18425–18433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kato, M., Ito, T., Wagner, G., Richardson, C. C. & Ellenberger, T. (2003) Mol. Cell 11, 1349–1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakai, H. & Richardson, C. C. (1988) J. Biol. Chem. 263, 9831–9839. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim, Y. T. & Richardson, C. C. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 5270–5278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hollis, T., Stattel, J. M., Walther, D. S., Richardson, C. C. & Ellenberger, T. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 9557–9562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sawaya, M. R., Guo, S. Y., Tabor, S., Richardson, C. C. & Ellenberger, T. (1999) Cell 99, 167–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bruck, I. & O'Donnell, M. (2001) Genome Biol. 2, 3001.1–3001.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Benkovic, S. J., Valentine, A. M. & Salinas, F. (2001) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 70, 181–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson, D. E. & Richardson, C. C. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 23762–23772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rezende, L. F., Hollis, T., Ellenberger, T. & Richardson, C. C. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 50643–50653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kong, D. C. & Richardson, C. C. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273, 6556–6564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Singleton, M. R., Sawaya, M. R., Ellenberger, T. & Wigley, D. B. (2000) Cell 101, 589–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burke, R. L., Alberts, B. M. & Hosoda, J. (1980) J. Biol. Chem. 255, 11484–11493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krassa, K. B., Green, L. S. & Gold, L. (1991) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88, 4010–4014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hurley, J. M., Chervitz, S. A., Jarvis, T. C., Singer, B. S. & Gold, L. (1993) J. Mol. Biol. 229, 398–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Witte, G., Urbanke, C. & Curth, U. (2003) Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 4434–4440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gao, D. X. & McHenry, C. S. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 4441–4446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Toth, E. A., Li, Y., Sawaya, M. R., Cheng, Y. F. & Ellenberger, T. (2003) Mol. Cell 12, 1113–1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leu, F. P., Georgescu, R. & O'Donnell, M. (2003) Mol. Cell 11, 315–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yuzhakov, A., Kelman, Z. & O'Donnell, M. (1999) Cell 96, 153–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brieba, L. G., Eichman, B. F., Kokoska, R. J., Doublie, S., Kunkel, T. A. & Ellenberger, T. (2004) EMBO J. 23, 3452–3461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.