Abstract

The FNT (formate-nitrite transporters) form a superfamily of pentameric membrane channels that translocate monovalent anions across biological membranes. FocA (formate channel A) translocates formate bidirectionally but the mechanism underlying how translocation of formate is controlled and what governs substrate specificity remains unclear. Here we demonstrate that the normally soluble dimeric enzyme pyruvate formate-lyase (PflB), which is responsible for intracellular formate generation in enterobacteria and other microbes, interacts specifically with FocA. Association of PflB with the cytoplasmic membrane was shown to be FocA dependent and purified, Strep-tagged FocA specifically retrieved PflB from Escherichia coli crude extracts. Using a bacterial two-hybrid system, it could be shown that the N-terminus of FocA and the central domain of PflB were involved in the interaction. This finding was confirmed by chemical cross-linking experiments. Using constraints imposed by the amino acid residues identified in the cross-linking study, we provide for the first time a model for the FocA–PflB complex. The model suggests that the N-terminus of FocA is important for interaction with PflB. An in vivo assay developed to monitor changes in formate levels in the cytoplasm revealed the importance of the interaction with PflB for optimal translocation of formate by FocA. This system represents a paradigm for the control of activity of FNT channel proteins.

Keywords: chemical cross-linking, computational docking model, formate-nitrite transporter, fermentation, protein, protein interaction

Introduction

FocA (formate channel A) is the archetype of the FNT (formate nitrite transporters) superfamily of membrane proteins [1–5]. FNT proteins are widely distributed among the archaea, bacteria and certain fungi and the family includes several thousand members that can be divided into minimally three sub-classes, with diverse cellular functions [5–7], suggesting that this family is evolutionarily ancient. As well as a conserved pentameric structure, the FNT proteins are characterized by their translocation of small monovalent anionic species, such as formate, nitrite or hydrosulfide, across bacterial cytoplasmic membranes [2,3,5,8,9]. As many of the microorganisms that synthesize FNT channels are anaerobes, these proteins likely provide microbial cells with the capability of energy-efficient and controlled uptake (or export) of anions [10].

Up to one-third of the carbon derived from glucose is converted to formate by the pyruvate formate-lyase (PflB) enzyme during fermentation in enterobacteria such as Escherichia coli [11,12]. PflB is a glycylradical enzyme that is post-translationally interconverted between inactive and active species [11,13]. The structure of PflB has been determined [14] and it is functional as a dimer exhibiting half-of-the-sites activity [13]. Introduction of the glycyl radical into PflB occurs only when E.coli grows anaerobically or during oxygen limitation and interconversion is strictly controlled in response to the metabolic status of the cell [11,13].

Formic acid has a pKa of 3.75, and therefore at neutral pH, the formate anion could accumulate in the cytoplasm leading to acidification, resulting in destruction of the proton gradient [15]. To counteract cytoplasmic acidification, formate is exported to the periplasm by FocA and probably by at least one further, as yet unidentified, system [1]. Two energy-conserving formate dehydrogenases have their respective active site located facing the periplasm, and therefore in the presence of appropriate electron acceptors, formate can function as an electron donor for respiration. If no acceptor is available, however, which occurs during fermentative growth, formate can be re-imported into the cell where it is metabolized by a formate-inducible formate hydrogenlyase complex to the gaseous products carbon dioxide and hydrogen [1,16]. Formate uptake by the cell also occurs through FocA; however, this is dependent upon an active formate hydrogenlyase complex, which dissipates intracellularly accumulated formate [17].

Physiological studies on fermentative formate metabolism in E. coli have provided evidence that FocA translocates the anion bidirectionally [1,17]. The mechanism underlying control of bidirectional formate translocation by FocA is unknown. Structural studies have suggested pH-dependent conformational control of formate channeling through FocA [4]. Furthermore, a recent electrophysiological study demonstrated that isolated FocA is capable of translocating not only formate but also acetate and lactate in vitro, leading to the suggestion that FocA might have a comparatively broad substrate specificity [8]. However, the tight coupling between FocA and PflB synthesis in vivo, together with the fact that a strong correlation between formate translocation and FocA could be demonstrated for E. coli cells but not for other mixed acids [1,17], suggests that a mechanism exists in vivo, ensuring that only formate is translocated by the channel. Therefore, identifying how in vivo substrate specificity and “gating” of the FNT proteins is governed is an important question to address. In this study, we demonstrate by physiological, biochemical, genetic and biophysical approaches that the PflB enzyme, which is responsible for formate generation in E. coli, interacts directly and specifically with the FocA channel. By modeling the FocA–PflB complex based on experimental restraints, we demonstrate the crucial role of the FocA N-terminus for the interaction. Our data provide the first structural insights into the role of PflB in controlling FocA channel activity.

Results

PflB influences FocA-dependent formate uptake by E. coli

Recent studies have shown that FocA non-selectively translocates formate and other weak acids in an in vitro system [8], while E. coli cells have a mechanism to transport formate selectively [1,17]. Because PflB is responsible for formate generation in bacteria such as E. coli and its synthesis is tightly coupled with that of FocA, we decided to examine whether PflB in its active or inactive form might exert a regulatory influence on the ability of fermenting E. coli to take up formate. To accomplish this, we made use of a recently developed formate-responsive reporter system, which can be used to monitor formate levels inside E. coli cells [18]. This reporter system is based upon the use of the formate-dependent promoter of the fdhF gene [16], which is fused to the gene encoding β-galactosidase. After anaerobic growth with glucose as carbon source, wild-type E. coli cells with a single-copy fdhF‘-’lacZ fusion exhibited a β-galactosidase activity corresponding to 1800 units (Fig. 1a). This reflects the level of formate generated internally from pyruvate by active PflB. Adding 10 mM formate to the growth medium increased the β-galactosidase activity roughly 2-fold and levels of expression increased up to a maximum level of approximately 4500 units when the medium was supplemented with 30 mM sodium formate (Fig. 1a). Introduction of stop codons into the focA gene, which prevented FocA synthesis but that did not affect PflB levels in the cell [1], resulted in a β-galactosidase activity of approximately 2000 units without exogenous addition of formate (Fig. 1b). Supplementation of the growth medium with formate had no apparent effect on intracellular levels of formate, as reflected by the lack of an increase in β-galactosidase enzyme activity compared with no formate addition.

Fig. 1.

Expression of a single-copy, formate-responsive fdhF‘-’lacZ transcriptional fusion in different E. coli strains grown anaerobically. Strains were grown in TGYEP rich medium supplemented with the formate concentrations indicated (see also Materials and Methods). Cultures were harvested for analysis of β-galactosidase enzyme activity in the mid-exponential phase of growth (OD600 nm between 0.6 and 0.8). The strains analyzed included (a) wild-type MC4100, (b) REK701 (focA), (c) 234M1 (pflA) (d) 234M1 containing plasmid pASK-IBA5focA and (e) RM220 (ΔpflB ΔpflA).

A mutant (strain 234M1) unable to synthesize the PflA enzyme, which is required to convert PflB from its inactive to its active, glycyl-radical-containing species [11], exhibited a basal β-galactosidase activity of only 200 units, reflecting the fact that formate could not be generated intracellularly (Fig. 1c). Addition of 10 mM formate to the culture medium resulted in a β-galactosidase activity of only 1400 units despite an active FocA protein being present in these cells. Increasing the concentrations of formate added to the growth medium had no effect on the β-galactosidase activity. This result suggests that the inactive form of PflB somehow prevents excessive FocA-dependent formate uptake.

Increasing the copy number of FocA [18] in the pflA mutant by introducing the focA gene on a multicopy plasmid (pASK-IBA5focA) into the pflA mutant 234M1 restored the ability of the strain to respond to exogenously applied formate (Fig. 1d).

Finally, deletion of both pflA and pflB (strain RM220) partially restored the ability of the strain to respond to exogenous formate (Fig. 1e), consistent with inactive PflB impairing formate uptake by FocA. The fact that the wild-type profile was not restored possibly reflects the fact that the strain cannot generate formate intracellularly. This finding might also suggest that the active, radical-bearing form of PflB potentially influences formate movement through the FocA channel.

Taken together, these results suggest that the inactive form of PflB prevents FocA-dependent formate uptake. This effect can be counteracted, however, by increasing the level of FocA in the cell.

FocA interacts with inactive PflB in vitro

PflB is a soluble protein normally localized within the cytoplasm of E. coli [11]. Upon sub-cellular fractionation of extracts from anaerobically grown cells of E. coli, it was noted that membrane fractions washed with buffer containing 150 mM NaCl bound PflB, while membranes from a mutant lacking FocA showed no PflB association (Fig. S1).

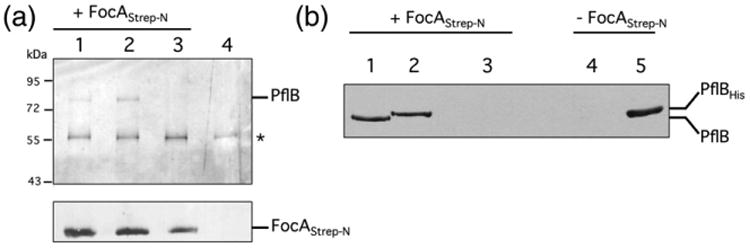

To test this interaction further, we mixed purified, N-terminally Strep-tagged FocA with a crude extract derived from anaerobically grown MC4100 cells (wild type) and we separated the resulting complex by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and challenged it with PflB antibodies (Fig. 2a). The Western blot revealed a clear interaction with an 85-kDa polypeptide and a polypeptide of ca 57 kDa. A similar result was observed with a crude extract derived from anaerobically grown REK702 (Fig. 2a, lane 2), which synthesizes higher levels of both FocA and PflB due to conversion of the focA GUG translation initiation codon to the more efficiently translated AUG codon [1,17]. In contrast, when the experiment was repeated with a crude extract of the pflB mutant RM220, no 85-kDa polypeptide corresponding to PflB was observed (Fig. 2a, lane 3). This result demonstrates that the 85 kDa (polypeptide) is PflB and that it interacts with Strep-tagged FocA. That the 57-kDa polypeptide was also observed in pull-down experiments performed with an extract derived from strain RM220 indicates that this protein is independent of PflB. A further control, in which the crude extract from strain REK702 was mixed with only Streptactin beads but without Strep-tagged FocA, revealed no 85-kDa polypeptide, but it did show a signal corresponding to the 57-kDa protein (Fig. 2a, lane 4). This result indicates that the 57-kDa protein interacts with the Streptactin matrix and cross-reacts with the antiserum raised against PflB but rules out a non-specific interaction between PflB and the matrix. Strep-tagged FocA that had been added to the crude extracts was detected using anti-FocA antiserum and represented a loading control (Fig. 2a, lower panel).

Fig. 2.

Protein–protein interaction studies with purified Strep-tagged FocA. (a) Purified N-terminally Strep-tagged FocA (10 μg of protein) was incubated with the soluble fraction (1 mg of protein) derived from strains MC4100 (lane 1), REK702 (lanes 2 and 4) or RM220 (ΔpflB) (lane 3), which had been grown anaerobically (see Materials and Methods). Equivalent amounts of suspension eluted from the Streptactin matrix were separated by 10% (w/v) (upper panel) or 12.5% (w/v) (lower panel) SDS-PAGE and challenged with antibodies directed against PflB or FocA, as indicated on the right side of each panel. Size markers in kDa are shown on the left (purified FocAStrep-N migrates with a molecular mass of 24 kDa) and the asterisk indicates the unidentified polypeptide that cross-reacts with the anti-PflB antibodies. (b) Purified Strep-tagged FocA (20 μg of protein) was incubated with 100 μg of soluble fraction derived from strains MC4100 containing plasmid p29 (resulting in overproduction of PflB) (lanes 1 and 4), RM201 (ΔfocA ΔpflB) (lane 3) or purified His-tagged PflB (10 μg) (lane 2), and after release of FocA and its interaction partners, the eluate was applied to a 10% (w/v) SDS-PAGE and after transfer to nitrocellulose the membrane was challenged with anti-PflB antibodies. The migration positions of PflB and His-tagged PflB are shown on the right of the panel. (See also Fig. S1.)

To confirm the interaction between purified FocA and purified PflB, we mixed equal amounts of purified Strep-tagged FocA and purified His-tagged PflB (see Materials and Methods and Supplementary Information), and after incubation, the polypeptides bound to Streptactin-coated magnetic beads were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. The results shown in lane 2 of Fig. 2b reveal that N-terminally Streptagged FocA specifically pulls down N-terminally His-tagged PflB. As a positive control, the same experiment was performed with a crude extract derived from strain MC4100 carrying plasmid p29 [19], which results in overproduction of PflB (Fig. 2b, lane 1). The native, untagged PflB protein migrated slightly faster than pure His-tagged PflB protein, which is shown in lane 5 (Fig. 2b). The negative control in which an extract derived from the pflB mutant RM201 was incubated with Strep-tagged FocA (lane 3 in Fig. 2b), or in which an extract derived from MC4100/p29 was not incubated with Strep-tagged FocA (lane 4, Fig. 2b), demonstrated that the interaction between FocA and PflB was specific.

Bacterial two-hybrid analysis indicates that the N-terminus of FocA is important for interaction with PflB

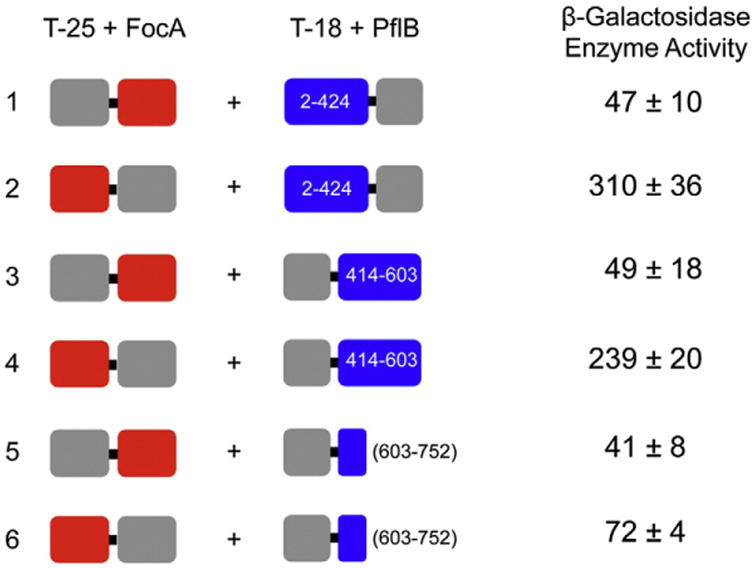

The focA gene was fused in-frame with a portion of the adenylate cyclase gene encoding the T25 fragment of the enzyme [20]. Two fusions were made: T25-FocA in which FocA was fused at the C-terminus of T25 and a FocA-T25 hybrid in which FocA was fused to the N-terminus of T25 (shown schematically in Fig. 3). Similarly, three separate but overlapping truncated polypeptides of PflB were fused with the portion of the cya gene encoding the T18 fragment of adenylate cyclase: these included PflB from amino acid position 2 to amino acid position 424, which was fused to the N-terminus of T18 and peptides encompassing amino acid positions 414–603 and 603–752 of PflB, which were fused to the C-terminus of T18. Different combinations of the two plasmids encoding the FocA fusions were transformed into the E. coli cya mutant DHM1 along with one of the three plasmids encoding the PflB-T18 fusions. These transformants were grown aerobically and were analyzed for β-galactosidase enzyme activity (Fig. 3). Fusion of the C-terminus of the T25 polypeptide with the N-terminus of FocA failed to deliver (β-galactosidase enzyme activity that was significantly above the level observed for the negative control (empty vectors encoding T25 and T18 without fusion partner). This result was observed regardless of which PflB-T18 fusion plasmid derivative was introduced. In contrast, when the T25 portion of adenylate cyclase was fused with the C-terminus of FocA, clearly measureable (β-galactosidase enzyme activity was observed with the PflB fragments that included amino acids 2–424 and 414–603 but not with that including amino acids 603–752. First, this indicates that a “free” N-terminus of FocA is crucial for the interaction with PflB. Second, the data suggest that FocA interacts either with a central region of PflB encompassing minimally amino acids 414 and 424 or with more than one region of PflB, with one interaction region located in the first 424 amino acids and the second between residues 414 and 600 (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Bacterial two-hybrid analysis of the FocA–PflB interaction. The constructs used in the analyses are shown schematically on the left of the figure. The gray boxes indicate either the T25 or the T18 fragment of the catalytic domain of adenylate cyclase, the red boxes signify full-length FocA and the blue boxes indicate PflB fragments. If the gray box is depicted on the left of the fusion construct, this signifies that FocA or PflB was fused to its C-terminus, while if the gray box is on the right, then it was fused to the C-terminus of the respective FocA or PflB fragment. The numbers within or next to the PflB boxes indicate which amino acids of PflB were fused to T18. The β-galactosidase enzyme activity with standard deviation in Miller units (see Materials and Methods) of the respective fusion combinations is shown on the right. Each experiment was performed at least three times in triplicate. The negative control (T25 and T18 plasmids without inserts) had an activity of 44 ± 6 Miller units, while the positive control (T25-zip and T18-zip from GCN4 supplied with the kit; Euromedex GmbH) had an activity of 715 ± 16 units.

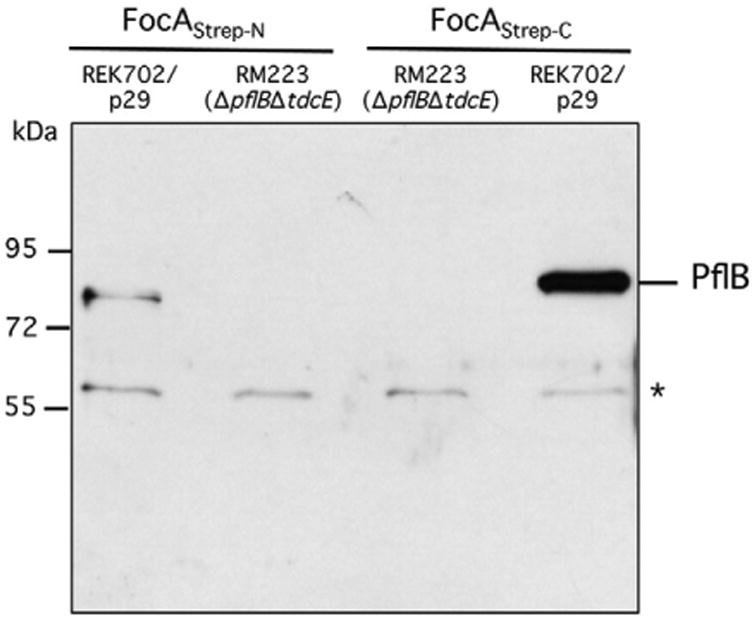

To confirm that the N-terminus of FocA is important for interaction with PflB, we compared the ability of FocA with an N-terminal or a C-terminal Strep-tag to interact in pull-down assays with PflB (Fig. 4). The results clearly indicate that, although N-terminally Strep-tagged FocA interacts specifically with PflB, the interaction is significantly more intense if the N-terminus remains untagged and the C-terminus of FocA carries the Strep-tag.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of the interaction between purified N- and C-terminally Strep-tagged FocA derivatives and PflB. Purified N- or C-terminally Strep-tagged FocA (20 μg of protein) was incubated with the soluble fraction (1 mg of protein) derived from strains REK702 (increased FocA level) transformed with plasmid p29 and RM223 (ΔpflB ΔpflA ΔtdcE), which had been grown anaerobically (see Materials and Methods and Table S3). Equivalent amounts of suspension eluted from the matrix were separated by 10% (w/v) SDS-PAGE and challenged with antibodies directed against PflB. Size markers in kDa are shown on the left and the asterisk denotes the unidentified polypeptide that cross-reacts with the anti-PflB antibodies. (See also Fig. S1.)

Chemical cross-linking analysis of the FocA-PflB interaction

In an initial cross-linking experiment, we aimed to identify potential binding partners of FocA using the heterobifunctional amine-reactive/photo-reactive cross-linker SDAD {succinimidyl 2-([4,4′-azipentanamido]ethyl)-1,3′-dithiopropionate} (see Supplementary Information for details). For this, Strep-tagged FocA was first modified with the amine-reactive site of SDAD before a fraction including soluble proteins of the E. coli strain REK702 (translation initiation codon of focA converted from GUG to AUG) [1] was added. After removing excess cross-linker, we induced the photo-cross-linking reaction by irradiating the mixture with long-wavelength UV. Making use of the C-terminal Strep-tag on FocA, Streptactin affinity chromatography allowed the purification of FocA–protein complexes and FocA-binding proteins were subsequently identified by liquid chromatography (LC)/tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) analysis (Table 1 and Table S1). The protein was identified based on the highest number of identified peptides (117) and the highest score was PflB confirming it as an interaction partner of FocA. Mass spectrometry (MS) and MS/MS data of a representative PflB peptide are presented in Fig. S2. It should be noted that PflB is one of the most abundant proteins in anaerobic E. coli cells (∼3% total cellular protein [11]) resulting in a large number of peptides in our MS-based analysis. Interestingly, pyruvate formate-lyase-activating enzyme (PflA) was also identified as an interaction partner of FocA (Fig. S3). PflA is a radical SAM enzyme that introduces a stable glycyl radical into PflB when E. coli grows anaerobically [21].

Table 1. Selected FocA binding partners.

| ID | Function | Molecular weight | Peptides | Peptide spectral matches | Mascot score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PflB | Formate acetyltransferase 1 | 85,300 | 40 | 117 | 1680 |

| AdhE | Aldehyde-alcohol dehydrogenase | 96,100 | 28 | 56 | 1571 |

| GadA | Glutamate decarboxylase α | 52,700 | 10 | 30 | 428 |

| PflA | Pyruvate formate-lyase 1-activating enzyme | 28,200 | 4 | 7 | 101 |

After having confirmed the formation of a complex between FocA and PflB, we aimed to gain insight into the topology of the complex by chemical cross-linking with the homobifunctional cross-linker bis (sulfosuccinimidyl) glutarate (BS2G). N-Hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) ester cross-linkers, such as BS2G, have been used successfully both by us [22] and by others [23,24] for deriving three-dimensional structural data of protein assemblies.

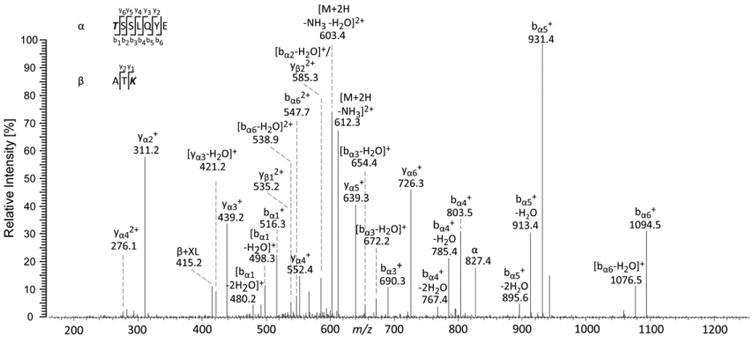

After the cross-linking reaction between FocA and PflB, reaction mixtures were separated by SDS-PAGE, enzymatically digested, and the resulting peptides were analyzed by LC/MS/MS. Altogether, 14 unique intermolecular cross-links were identified between FocA and PflB (Table 2 and Supplementary Information, Table S2). One representative cross-link between Lys29 (FocA) and Lys395 (PflB) is presented in Fig. 5.

Table 2. Cross-links identified between FocA and PflB.

| [M + H]+ theoretical | FocA site of cross-linking | PflB site of cross-linking |

|---|---|---|

| 3953.016 | K17 | K312 |

| 3062.576 | K26 | K197 |

| 2647.332 | K17 | K32 |

| 2513.296 | K17 | K441 |

| 2490.240 | K112 | S463 |

| 2383.182 | K17 | Y126 |

| 2248.101 | K191 | T298 |

| 2232.114 | K17 | S338 |

| 2136.097 | K17 | Y192 |

| 2072.037 | K17 | K643 |

| 2023.997 | S187 | K136 |

| 1925.086 | T28 | K96 |

| 1522.826 | K26 | Y726 |

| 1241.590 | K29 | T395 |

Fig. 5.

Fragment ion mass spectrum (MS/MS) of a doubly charged cross-linked product at m/z 621.298. The cross-linked product was unambiguously assigned to amino acids 27–29 (ATK) of FocA connected to amino acids 395–401 (TSSLQE) of PflB. The fragment ions point to Lys29 (FocA) cross-linked with Thr395 (PflB). (See also Fig. S2.)

Two additional cross-links between Lys112 (FocA) and Ser463 (PflB), as well as between Lys17 (FocA) and Lys441 (PflB), are shown in Fig. S4. The fact that 11 out of 14 cross-links are with amino acids (Lys17, Lys26, Thr28 and Lys29) in the N-terminus of FocA indicates a high flexibility of FocA's N-terminus, allowing it to react with diverse regions in PflB (Table 2). The importance of the N-terminus of FocA for the interaction with PflB had already been indicated by other experiments (see above).

Model of the FocA–PflB complex consistent with cross-linking data

In order to determine a likely binding orientation of PflB to FocA, we generated physically realistic models of the interaction between PflB and FocA by computational docking. Structures of FocA and PflB were downloaded from the Protein Data Bank. The N-terminus of FocA is a conformationally flexible, α-helix-containing peptide and has been crystallized in multiple conformations [4]. In the crystal structure of FocA from Salmonella typhimurium, the N-termini of four chains are resolved and the protomers are labeled as “closed” and “intermediate”. The N-termini of closed and intermediate protomers closely interact in adjacent protomers. Additionally, the loop connecting TM2a and TM3, the Ω-loop, is structurally flexible and has been observed in many conformations [3,4]. In order to assess the full conformational space of the cytoplasmic face of FocA, we homology modeled the N-terminus, Ω-loop and C-terminus of E. coli FocA [25] and/or we folded the N-terminus de novo [26,27] and re-combined conformations from each source in a stochastic manner. The models were energy minimized [28], and low-energy models (1.5% of ∼2000) were carried forward. A rigid-body, global conformational search was performed using a centroid-based side-chain representation [29] wherein the conformation of PflB was fully randomized relative to FocA. The top 10% of ∼50,000 models, as analyzed by interchain interaction energy, were evaluated for agreement with the experimentally derived cross-linking restraints (Fig. S5).

Cross-links generated with BS2G are commonly evaluated at a maximal Cα–Cα distance of 25 Å, accounting for the linker length, side-chain length and additional ambiguity of the atom placement in the crystal structure or model [3,4]. With the use of a restraint cutoff distance of 25 Å, at most 7 out of the 14 cross-linking restraints were satisfied (Fig. S6a). Given the flexibility in the N-termini and the low resolution of our models, we analyzed progressively greater cutoff distances. At cutoff distances of 30 Å and 35 Å, only 9 and 12, respectively, of the 14 cross-links were simultaneously fulfilled. Only at a cutoff distance of 40 Å were all 14 cross-linking restraints simultaneously satisfied by a single model.

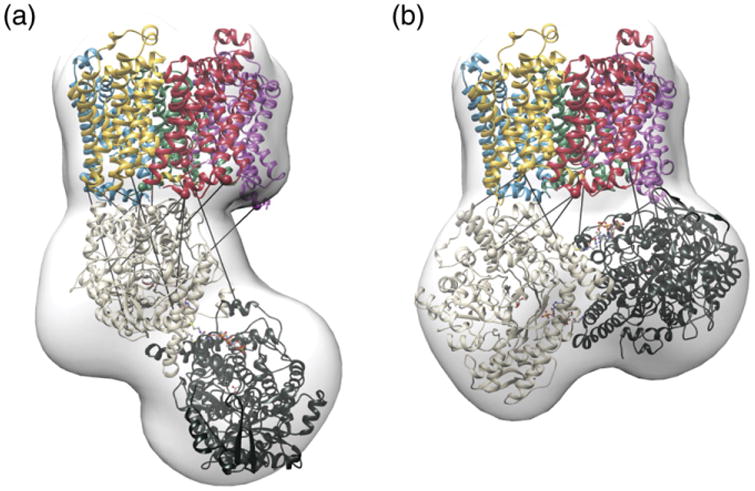

Given that no single model fulfilled all restraints at the lower distance cutoffs, we tested whether there is a combination of two models that satisfy the 14 cross-links at a lower cutoff distance. Indeed, there were 54 model pairs at a cutoff of 30 Å, which satisfied all cross-links simultaneously. Each model of the pair falls into one of two orientations of PflB relative to FocA, named conformation A and conformation B (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Model of the FocA–PflB complex. Conformations a and b were selected by cross-linking restraints from the docking models. FocA and PflB protomers are individually colored. Bars indicate the best-fulfilled cross-link for that model as measured by Cα–Cα distance. Conformational space of the ensemble is represented by the white density envelope. (See also Figs. S3 and S4.)

We then analyzed the relative orientation of PflB to FocA in the model populations that intervene each cutoff distance via clustering, for example, those models satisfying 6 or 7 restraints at 25 Å; 8 or 9 restraints at 30 Å; 10, 11 or 12 restraints at 35 Å; and 13 or 14 restraints at 40 Å. Two well-populated conformations with a cluster size of ∼7–8 Å RMSD were observed at 25 Å and 30 Å cutoff distances. These two clusters correspond to the previously observed conformations A and B. At greater cutoff distances of 35 Å and 40 Å, the model population converges on a single cluster, which includes conformation B. Individually, the two clusters each satisfied 7 restraints with an average Cα–Cα distance of 30–35 Å or better (T28-K96, K17-Y192, K17-Y126, K17-K312, K26-Y726, K29-T395 and K17-K32) (Fig. S6b). In the population selected by greater distance cutoffs, cluster B, an additional four restraints were satisfied at an average Cα-Cα distance of 30–35 Å (K17-K441, S187-K136, K26-K197 and K112-S463). By comparison, two cross-links were better satisfied by the lower-distance-cutoff population: K191-T298 and, to a lesser extent, K17-S338. Finally, the cross-link between Lys17 (FocA) and K643 (PflB) was only rarely satisfied at distances below 40 Å in either conformational population. Taken together, the modeling data indicate the presence of both conformations during the cross-linking experiment and that both conformations are physically realistic. Note that, as the experiment was performed on an ensemble of FocA–PflB complexes, it is consistent with the notion that conformation A is an intermediate on a pathway that ultimately leads to conformation B.

Discussion

Physiological implications of the PflB–FocA interaction

The apparent discrepancy in substrate specificity of FocA channels observed in the in vitro experiments conducted with purified protein [8], in which the products of mixed-acid fermentation were translocated, and in in vivo studies [17], in which formate was the sole substrate of FocA, could potentially be accounted for by the findings presented in the current study. The physical interaction of FocA with PflB likely ensures that formate is the only substrate of FocA in intact bacterial cells. PflB interacts specifically with FocA and our in vivo studies suggest that PflB controls whether substrate is translocated and possibly also the directionality of substrate movement through the pore of each monomer [7,10].In particular, we showed that, if PflB is exclusively in the inactive species (e.g., in a pflA mutant; Fig. 1c) then regardless of how much formate was supplied exogenously, the activity of the reporter remained unaffected with the exception of a low level of accumulation presumably via a further as yet unidentified formate transport system [1,17]. This finding suggests that either formate is continuously exported from the cells by FocA or it cannot be taken up effectively by the channel. Increasing the copy number of FocA in the pflA mutant restored the ability of the cells to accumulate formate intracellularly, suggesting that formate uptake might be impaired when PflB is inactivated. Physiologically, this would make sense because when PflB is not in its active, glycyl-radical form, this signifies that the cells have stopped formate production and presumably formate uptake is also restricted by binding of inactive PflB to FocA [11].

That the inactive form of PflB interacts with FocA was demonstrated in the in vitro pull-down and interaction studies. All of these experiments were performed in the presence of oxygen, and because the glycylradical-bearing form of PflB has a half-life of less than 10 s in air [11], this indicates that all of the interactions analyzed in this study involved only the inactive enzyme species. We currently cannot state categorically whether the active, radical-bearing enzyme species also binds FocA or whether it binds in a different conformation resulting in altered uptake or export properties of the channel (e.g., Fig. 1e).

Binding of the PII signal transduction protein, GlnK, to the ammonia channel AmtB blocks further uptake of ammonia or ammonium by the channel [30]. Depending on the organism, a phosphorylated or a uridydylated form of GlnK binds specifically to AmtB sterically blocking the channel. Protein modification might also be of relevance to the PflB–FocA interaction because the ratio of dimeric PflB to pentameric FocA in the anaerobic E. coli cell is roughly 150:1 and therefore a further level of regulation that controls when and how the appropriate form of PflB interacts with FocA must exist. Based on our cross-linking and modeling studies, we assume a 1:1 stoichiometry of the dimeric PflB: pentameric FocA complex; however, the requirement for detergent has so far prevented an accurate assessment of the stoichiometry of both proteins in the complex. The observation that PflB can be acetylated on specific surface-exposed lysine residues [31] might explain the multiple isoforms of the enzyme previously observed upon two-dimensional PAGE analysis of the protein [19], as well as might provide a means of ensuring that a post-translationally modified sub-species of PflB enters into an interaction with FocA. Future studies will be required to elucidate the physiological significance of this interaction in more detail.

Specificity of the PflB-FocA interaction

PflB interacts with the cytoplasmically oriented face of FocA and the N-terminal helix of FocA is important for the specific interaction with PflB. The in vivo bacterial two-hybrid study also showed that interaction with PflB was prevented when the N-terminus of FocA was fused to the T25 domain of adenylate cyclase. The bacterial two-hybrid approach also proved useful in narrowing down the key regions in PflB that interacted with FocA. Together with the results of chemical cross-linking, two main “regions” of PflB were shown to be important for the interaction with the N-terminus of FocA, namely amino acids in the neighborhood of K32, K96 and K126 and those near S338, T395 and K441. Amino acid K17 of FocA also interacted with K192 and K312 indicating that the N-terminus of FocA exhibits clear flexibility [3,4] in its ability to interact with different regions of PflB. Specific interactions among amino acids K163, T296 and S463 were also identified with amino acids K191, S187 and K112, respectively, which are located at the base of the central pore of the FocA pentamer. A detailed amino acid exchange program is currently being undertaken to determine precisely which amino acids in PflB are involved in the interaction with FocA.

Despite PflB delivering the highest number of peptides cross-linked to FocA, a number of other polypeptides were identified in the cross-linking study that had relevance to fermentative metabolism. These included AdhE, which is an abundant protein during anaerobic growth and has been proposed to regulate the activity of PflB by post-translational modification [32]. The other enzyme that post-translationally modifies PflB is its activating enzyme PflA and this was also identified as a cross-linked product. PflA is a radical SAM enzyme [21] that introduces the free radical onto Gly734 of PflB [13]. Other proteins that formed a complex with FocA included a number of different amino acid decarboxylases and pyruvate dehydrogenase (Table S1), suggesting a potential link between FocA and proteins of CO2/bicarbonate metabolism.

Two-stage model for FocA–PflB interaction

The fact that 11 out of 14 cross-links to PflB were with amino acids (K17, K26, T28 and K29) in the N-terminal helix of FocA indicates a high flexibility of FocA's N-terminus, allowing it to react with diverse regions in PflB (Table 2). Because of this flexibility, it was necessary to decrease the constraint on the Cα–Cα distance, which is usually set at 25 Å, in order to construct a model, particularly for the BS2G cross-links, and this took into consideration the high flexibility of the N-terminal region of FocA. Based on the cross-linking data, it can be considered that both conformations of PflB shown in Fig. 6 are biologically relevant and represent a dynamic process in which multiple orientations are captured during cross-linking. Therefore, we hypothesize that conformation A, being entropically favored, is an intermediate complex and represents a lower-affinity precursor interaction state. As the high-affinity complex forms from this initial intermediate, both protomers of PflB begin to interact with FocA to generate an enthalpically favored interaction, more similar to conformation B in Fig. 6. In this scenario, conformation A is an intermediate on a pathway that ultimately leads to the more intimate interaction observed in conformation B. This enthalpically favored orientation positions the CoA-binding site of PflB [33] toward FocA. The route of formate egress from the enzyme has not been demonstrated [14,33]. In conformation B, one CoASH tunnel is oriented toward FocA. If formate exits through the same entry as CoASH, then a loose channel would be present allowing ready export out of the cell. However, the present models are not of sufficient resolution to prove this hypothesis or suggest any residues that play an active role in funneling formate from PflB to the FocA pore.

In the absence of PflB, the pore is closed through blocking of the channel by the N-terminal helix. It should be noted, however, that recent molecular dynamics simulations [34] suggest that formate can still enter and exit the channel in FocA even when the N-terminal helix covers the pore entrance. This finding further underscores the likely importance of the interaction with PflB for controlled movement of formate through FocA.

If only conformation B in Fig. 6 is of functional relevance, because all constraints are fulfilled, albeit at higher cutoff distances, this would imply that conformation A does not represent a physiologically realistic interaction. Differentiation of conformations A and B is hampered by the flexibility of the N-terminal helix, which was incomplete in the crystal structures [2–4]. It should also be noted that the static crystal structures used for docking and cross-link evaluation will limit the average distances, and in reality, they are expected to be larger as a consequence of N-terminal flexibility. Moreover, the rigid placement of the N-termini across the cytoplasmic face of FocA may limit interaction between FocA and PflB. Finally, the modeling procedure only estimates the local flexibility of the protein during the cross-linking process. This is accomplished by ensemble docking energy-minimized structures but most likely underestimates the true flexibility of the proteins. These caveats notwithstanding our studies provide the first clear demonstration of a protein– protein interaction having consequences for the control of the substrate specificity and potentially gating of a member of the FNT superfamily. These findings open up new possibilities to study the mechanisms controlling substrate movement through these evolutionarily ancient anion channels. Moreover, a further exciting challenge will be to determine whether this regulatory principle for controlling anion movement through channels extends to other FNT family members in archaea and lower eukaryotes.

Materials and Methods

Strains, plasmids and growth conditions

All bacterial strains and plasmids used are listed in Table 1. Strains were grown at 37 °C in Luria Broth [35] or the buffered, rich medium TYEP [TYEP: 1% (w/v) tryptone, 0.5% (w/v) yeast extract and 100 mM potassium phosphate, pH 6.5] including 04% (w/v) glucose (TGYEP) as previously described [36]. Cells used for the preparation of membrane fractions were cultivated as previously described [18]. BL21 cells used for the overproduction of FocA variants were grown in TB medium [18]. The cells used for the overproduction of PflB were grown aerobically in TB medium at 30 °C. The cultivation of the cells for the bacterial two-hybrid system (BACTH System; Euromedex GmbH) was performed under aerobic and anaerobic conditions in Luria Broth medium at 30 °C in 15 ml Hungate tubes [37].

Standard aerobic cultivation of bacteria was performed on a rotary shaker (250 rpm) and at 37 °C. Anaerobic growths were performed at 37 °C in sealed bottles filled with anaerobic growth medium. When required, the growth medium was solidified with 1.5% (w/v) agar. All growth media were supplemented with 0.1% (v/v) SLA trace element solution [38]. The antibiotics chloramphenicol, kanamycin and ampicillin, when required, were added to the medium at the final concentrations of 12.5 μg/ml, 50 μg/ml and 100 μg/ml, respectively.

Construction of the plasmids for the bacterial two-hybrid system

Genomic DNA from E. coli MC4100 was isolated using the DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen). The amplification of the different focA and pflB gene constructs was carried out using the primers described in Table S1 and the Phusion DNA polymerase (Finnzyme). The resulting PCR products were cloned into the vector pKNT25, pKT25, pUT18 or pUT18C (digested with PstI and EcoRI). The plasmids were sequenced to ensure the authenticity of the cloned DNA fragments. Plasmids were transformed into DHM1 via electroporation and tested exactly as described by the manufacturer (Euromedex GmbH).

Sub-cellular fractionation of E. coli crude extracts to examine PflB–FocA interaction

Harvested cells (1 g wet weight) were resuspended in 3 ml of 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0) and 150 mM NaCl (buffer A) containing 1 mg lysozyme, 0.1 μM PMSF and 15 μg DNase I. After incubation for 30 min at 30 °C, cells were disrupted on ice by sonication (Sonoplus Bandlin, Berlin) using a KE76 tip, 30 W power and 3 cycles of 4 min treatment with 0.5 s intervals. Unbroken cells and cell debris were removed by centrifugation at 43,000g for 45 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was termed the crude extract and this was further fractionated by centrifugation at 105,000g for 45 min at 4 °C in a Discovery M120 SE AT4 table-top ultracentrifuge (Sorvall). The supernatant was carefully decanted and represented the soluble fraction while the pellet was resuspended in the original volume of buffer A and centrifuged again as described above to remove contaminating soluble proteins. Finally, the pellet was resuspended in 0.1 ml of buffer A and this represented the membrane fraction.

To examine the effect of increasing the NaCl concentration on the interaction between FocA and PflB, we prepared the membrane fraction in 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0) without NaCl, in 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0) with 150 mM NaCl, in 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0) with 250 mM NaCl and in 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.0) with 500 mM NaCl. After the first centrifugation step, the soluble fraction (S) was decanted, the pellet resuspended in the original volume of buffer containing the indicated NaCl concentration and centrifuged again. The supernatant was referred to as the wash fraction (W) and the pellet was resuspended in 0.1 ml buffer A and was referred to as the membrane (M) fraction.

PAGE and immunoblotting

Aliquots of 25-50 μg of protein from the indicated sub-cellular fractions were separated by SDS-PAGE using either 10% (w/v), 12.5% (w/v) or 15% (w/v) polyacrylamide gels [39] and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes as previously described [40]. Antibodies raised against PflB (1:3000) [1], a FocA peptide (1:500) [18], purified FocA (1:2000) or aconitase A (AcnA) from E. coli (1:5000; a kind gift from J. Green Sheffield, UK) were used. Secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase was obtained from Bio-Rad. Visualization was done by the enhanced chemiluminescent reaction (Agilent Technologies). The N-terminally Strep-tagged FocA fusion protein was purified according to [18] and used to raise polyclonal antibodies in rabbits using the procedures of the company Seqlab (Germany).

Antibody purification

To improve the detection of FocA in Western blot analysis, we produced polyclonal antibodies against the full-length FocA protein in rabbits, using the 3-month standard immunization protocol (Seqlab Göttingen, Germany).

The antibodies were affinity purified from the final serum bleed by using the Amino Link® coupling gel (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, USA) as described by the manufacturer. Elution of the bound antibodies was achieved using 50 mM glycine–HCl (pH 2.5), 0.1% (w/v) Triton X-100 and 0.15 M NaCl.

In Western blot analysis, the FocA antibody was used in a 1:2000 dilution with 5% (w/v) bovine serum albumin in phosphate buffer and the secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Bio-Rad, München, Germany) was used according the manufacturer's instruction.

Purification of tagged proteins and pull-down assay with Streptactin-coated magnetic beads

Strep-tagged FocA derivatives were purified exactly according to Ref. [18].

To identify possible interactions between two proteins, we used the pull-down assay with a 5% suspension of Streptactin magnetic beads (Mag Strep “type I” beads, IBA Biotagnology). Aliquots (20 μg) of purified FocA with an N-terminal or a C-terminal Strep-tag were added to 25 μl of the Streptactin-coated magnetic beads and washed several times with buffer W [100 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) and 1 mM n-dodecyl-β-maltoside (DDM) (pH 8.0)]. Afterwards the beads were incubated by gentle agitation for 2 h at 4 °C with 100–1000 μg of different soluble fractions derived from different anaerobically grown E. coli strains. After extensive washing with 10 ml buffer W, we eluted bound proteins by using 50 μl of buffer W containing 2.5 mM α-desthiobiotin.

SDAD cross-linking

Strep-tagged FocA was diluted with 100 mM Mops, 150 mM NaCl and 0.03% (w/v) DDM (pH 7.0) to give a final protein concentration of 10 μM. A solution (48.4 mM) of the amine-reactive/photo-reactive cross-linker SDAD (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in DMSO was added in a 50-fold molar excess over FocA. FocA was modified with the amine-reactive site of SDAD by incubation for 1 h at room temperature in the dark. Non-reacted cross-linker was removed using Amicon ultra-filtration units (0.5 ml, 10 kDa cutoff; Millipore) before SDAD-modified FocA was recovered in 100 mM Mops, 150 mM NaCl and 1 mM DDM (pH 7.0). A fraction of soluble proteins from E. coli strain REK702 (protein content of 600 μM) was added to SDAD-modified FocA to give a final protein concentration of 100 μM. Photo-cross-linking between FocA and its binding partners was induced by irradiation with long wavelength UV light (maximum at 365 nm, 8000 mJ/cm2).

BS2G cross-linking

Prior to chemical cross-linking with the homobifunctional amine-reactive cross-linker BS2G, protein preparations of FocA and PflB were subjected to buffer exchange using Amicon ultra-filtration units (0.5 ml, 10 kDa cutoff; Millipore). FocA and PflB were recovered in 100 mM Mops, 150 mM NaCl and 1 mM DDM (pH 7.0) and were mixed to a final concentration of 20 μM FocA (pentamer) and 13.1 μM PflB (dimer). Afterwards, a solution (504 mM) of BS2G (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in DMSO was added to a final concentration of 25 mM. BS2G cross-linking was carried out for 30 min at room temperature. The cross-linking reaction was quenched using Tris (final concentration of 50 mM).

Affinity purification of FocA complexes

Cross-linked complexes between FocA and binding proteins were purified using a gravity-flow column filled with 1 ml of Streptactin Sepharose High Performance Matrix (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences). The column was equilibrated with at least five column volumes of equilibration buffer [100 mM Tris–HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA and 1 mM DDM, pH 8.0] and the sample was mixed with 2 ml of the same buffer before loading it onto the column. The column was washed with 15 column volumes of equilibration buffer before FocA–protein complexes were eluted with 100 mM Tris–HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DDM and 2.5 mM desthiobiotin (pH 8.0).

SDS-PAGE and in-gel digestion

SDS-PAGE (12% resolving gel) under non-reducing conditions was used to visualize FocA complexes. After staining the gel with Coomassie Brilliant Blue, we excised cross-linked complexes and in-gel digested them with trypsin (for the interaction partner screening approach) or with a mixture of trypsin and GluC (for the modeling approach) (both enzymes from Promega) following an established protocol [41].

Mass spectrometry

In-gel digested peptide mixtures were analyzed by LC/MS on an UltiMate Nano-HPLC system (LC Packings/Dionex) coupled to an LTQ-Orbitrap XL mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) equipped with a nanoelectrospray ionization source (Proxeon). The samples were loaded onto a trapping column (Acclaim PepMap C18, 100 μm × 20 mm, 5 μm, 100 Å, LC Packings) and washed for 15 min with 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid at a flow rate of 20 ul/min. Trapped peptides were eluted on a separation column (Acclaim PepMap C18, 75 μm × 250 mm, 3 μm, 100 Å, LC Packings) that had been equilibrated with 100% A (5% acetonitrile and 0.1% formic acid). Peptides were separated with linear gradients from 0% to 40% B [80% (v/v) acetonitrile and 0.08% (v/v) formic acid] over 60 or 90 min. The column was kept at 30 °C and the flow rate was 300 nl/min. MS data were acquired throughout the duration of the gradient using the data-dependent MS/MS mode. Each high-resolution full scan (m/z of 300–2000 and resolution of 60,000) in the Orbitrap analyzer was followed by five product ion scans (collision-induced dissociation–MS/MS) in the linear ion trap for the five most intense signals of the full scan mass spectrum (isolation window, 2.5 Th). Dynamic exclusion (repeat count, 3; exclusion duration, 180 s) was enabled to allow detection of less abundant ions. Data analysis was performed using the Proteome Discoverer 1.2 (Thermo Fisher Scientific); MS/MS data of precursor ions in the m/z range 500–5000 were searched against the SwissProt Database (version 11/2010, taxonomy E. coli, 22,729 entries) using Mascot (version 2.2, Matrixscience); mass accuracy was set to 3 ppm and 0.8 Da for precursor and fragment ions, respectively; carbamidomethylation of cysteines was set as fixed modification and oxidation of methionine as variable modification; and up to three missed cleavages of trypsin were allowed.

Identification of cross-linked products

Analysis and identification of cross-linked products were performed with the in-house software StavroX [42]. StavroX was used for automatic comparison of MS and MS/MS data from Mascot generic format (mgf) files. Potential cross-links were manually evaluated. A maximum mass deviation of 3 ppm between theoretical and experimental masses and a signal-to-noise ratio ≥2 were allowed. Lys, Ser, Thr, Tyr and N-termini were considered as potential cross-linking sites for the sulfo-NHS ester BS2G [43]. Additionally, carbamidomethylation of Cys and oxidation of Met were taken into account as potential modifications, in addition to three missed cleavage sites for each amino acid Lys, Arg, Glu and Asp.

Molecular modeling of PflB–FocA interaction

Structural diversity of E. coli FocA was generated through homology modeling. N-termini, Ω-loops and membrane-spanning channels of E. coli (3kcu and 3kcv) (PMID: 19940917), S. typhimurium (3q7k) (PMID: 21493860) and Vibrio cholerae (3kly and 3klz) (PMID: 20010838) were collected; categorized as “closed”, “intermediate” or “open”; and randomly recombined through threading of the E. coli sequence and grafting of atomic coordinates. Conformations of the N-termini in the open conformation are not resolved in the available crystal structures. Therefore, conformations were generated through de novo modeling by fragment insertion [26] and/or grafting of intermediate and closed conformations. As in the S. typhimurium [4] and V. cholerae [3] structures, protomers A and C are modeled in the intermediate conformation, protomers B and D are in the closed conformation and protomer E is in the open conformation. These grafted and threaded models were energy minimized with the Rosetta relax protocol [28]. Atomic coordinates for E. coli PflB (1h16) were energy minimized in the presence of coenzyme A and pyruvate [33] via the relax protocol. FocA and PflB were docked with the coarse-grained, centroid-based (low-resolution) component of the Rosetta protein–protein docking algorithm (PMID: 21829626) after random orientation and rotation of PflB on the cytoplasmic face of FocA. The resulting 50,000 models were sorted by interchain interaction energy and the top 10% for fulfillment of the cross-links were chosen. Ensembles for each major cluster are represented as electron density in Fig. 6, which is simulated using BCL∷PDBToDensity (PMID: 21565271) at 20 Å resolution with a voxel size of 5 after overlaying each of the models in the cluster.

Other methods

Protein concentration was determined according to Ref. [44].

The β-galactosidase activity was determined and calculated according to Refs. [1] and [35]. Each experiment was performed three times independently and the activities for each sample were determined in triplicate. The activities are presented with standard deviations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the GRK1026 (conformational transitions in macromolecular interactions) from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and by the “Exzellenzinitiative” of the region of Saxony-Anhalt. Work in the Meiler laboratory is supported through National Institutes of Health (R01 GM080403, R01 MH090192, R01 GM099842 and R01 DK097376) and National Science Foundation (BIO Career 0742762 and CHE 1305874). Jeff Green from the University of Sheffield is thanked for supplying us with E. coli–AcnA antiserum.

Abbreviations used

- MS

mass spectrometry

- MS/MS

tandem mass spectrometry

- EDTA

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- DDM

n-dodecyl-β-maltoside

- LC

liquid chromatography

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data: Supplementary data to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2014.05.023.

References

- 1.Suppmann B, Sawers G. Isolation and characterisation of hypophosphite-resistant mutants of Escherichia coli: identification of the FocA protein, encoded by the pfl operon, as a putative formate transporter. Mol Microbiol. 1994;11:965–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang Y, Huang Y, Wang J, Cheng C, Huang W, Lu P, et al. Structure of the formate transporter FocA reveals a pentameric aquaporin-like channel. Nature. 2009;462:467–72. doi: 10.1038/nature08610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Waight AB, Love J, Wang DN. Structure and mechanism of a pentameric formate channel. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:31–7. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lü W, Du J, Wacker T, Gerbig-Smentek E, Andrade SL, Einsle O. pH-dependent gating in a FocA formate channel. Science. 2011;332:352–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1199098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Czyzewski BK, Wang DN. Identification and characterization of a bacterial hydrosulphide ion channel. Nature. 2012;483:494–7. doi: 10.1038/nature10881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Unkles SE, Symington VF, Kotur Z, Wang Y, Siddiqi MY, Kinghorn JR, et al. Physiological and biochemical characterization of AnNitA, the Aspergillus nidulans high affinity nitrite transporter. Eukaryot Cell. 2010;10:1724–32. doi: 10.1128/EC.05199-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waight AB, Czyzewski BK, Wang DN. Ion selectivity and gating mechanisms of FNT channels. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2013;23:499–506. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2013.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lü W, Du J, Schwarzer NJ, Gerbig-Smentek E, Einsle O, Andrade SL. The formate channel FocA exports the products of mixed-acid fermentation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:13254–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1204201109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lü W, Schwarzer NJ, Du J, Gerbig-Smentek E, Andrade SL, Einsle O. Structural and functional characterization of the nitrite channel NirC from Salmonella typhimurium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:18395–400. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1210793109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lü W, Du J, Schwarzer NJ, Wacker T, Andrade SL, Einsle O. The formate/nitrite transporter family of anion channels. Biol Chem. 2013;394:715–27. doi: 10.1515/hsz-2012-0339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knappe J, Sawers G. A radical route to acetyl-CoA: the anaerobically induced pyruvate formate-lyase system of Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1990;75:383–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1990.tb04108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sawers G, Blokesch M, Böck A. Anaerobic formate and hydrogen metabolism. In: Curtiss R III, editor. EcoSal—Escherichia coli and Salmonella: Cellular and Molecular Biology. 3.5.4. Washington, DC: ASM Press; 2004. September 2004, posting date. [Online.] http://www.ecosal.org. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wagner AF, Frey M, Neugebauer FA, Schäfer W, Knappe J. The free radical in pyruvate formate-lyase is located on glycine-735. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:996–1000. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.3.996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Becker A, Fritz-Wolf K, Kabsch W, Knappe J, Schulz S, Wagner AFV. Structure and mechanism of the glycyl radical enzyme pyruvate formate-lyase. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6:969–75. doi: 10.1038/13341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sawers RG. Formate and its role in hydrogen production in E. coli Biochem Soc Trans. 2005;33:42–6. doi: 10.1042/BST0330042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rossmann R, Sawers G, Böck A. Mechanism of regulation of the formate-hydrogenlyase pathway by oxygen, nitrate, and pH: definition of the formate regulon. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:2807–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb01989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beyer L, Doberenz C, Falke D, Hunger D, Suppmann B, Sawers RG. Coordinating FocA and pyruvate formate-lyase synthesis in Escherichia coli: preferential translocation of formate over other mixed-acid fermentation products. J Bacteriol. 2013;195:1428–35. doi: 10.1128/JB.02166-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Falke D, Schulz K, Doberenz C, Beyer L, Lilie H, Thiemer B, et al. Unexpected oligomeric structure of the FocA formate channel of Escherichia coli: a paradigm for the formate-nitrite transporter family of integral membrane proteins. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2010;303:69–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01862.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Christiansen L, Pedersen S. Cloning, restriction endonuclease mapping and post-transcriptional regulation of rpsA, the structural gene for ribosomal protein S1. Mol Gen Genet. 1981;181:548–51. doi: 10.1007/BF00428751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karimova G, Pidoux J, Ullmann A, Ladant D. A bacterial two-hybrid system based on a reconstituted signal transduction pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:5752–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.10.5752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Külzer R, Pils T, Kappl R, Hüttermann J, Knappe J. Reconstitution and characterization of the polynuclear iron-sulfur cluster in pyruvate formate-lyase-activating enzyme. Molecular properties of the holoenzyme form. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:4897–903. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.9.4897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dimova K, Kalkhof S, Pottratz I, Ihling C, Rodriguez F, Liepold T, et al. Structural insights into the calmodulin/ Munc13 interaction by cross-linking and mass spectrometry. Biochemistry. 2009;48:5908–21. doi: 10.1021/bi900300r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kalisman N, Adams CM, Levitt M. Subunit order of eukaryotic TRiC/CCT chaperonin by cross-linking, mass spectrometry, and combinatorial homology modeling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:2884–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119472109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herzog F, Kahraman A, Boehringer D, Mak R, Bracher A, Walzthoeni T, et al. Structural probing of a protein phosphatase 2A network by chemical cross-linking and mass spectrometry. Science. 2012;337:1348–52. doi: 10.1126/science.1221483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mandell DJ, Coutsias EA, Kortemme T. Sub-angstrom accuracy in protein loop reconstruction by robotics-inspired conformational sampling. Nat Methods. 2009;6:551–2. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0809-551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rohl CA, Strauss CE, Misura KM, Baker D. Protein structure prediction using Rosetta. Methods Enzymol. 2004;383:66–93. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(04)83004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fleishman SJ, Leaver-Fay A, Corn JE, Strauch EM, Khare SD, Koga N, et al. RosettaScripts: a scripting language interface to the Rosetta macromolecular modeling suite. PLoS One. 2011;6:e20161. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qian B, Raman S, Das R, Bradley P, McCoy AJ, Read RJ, et al. High-resolution structure prediction and the crystallo-graphic phase problem. Nature. 2007;450:259–64. doi: 10.1038/nature06249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gray JJ, Moughon S, Wang C, Scheuler-Furman O, Kuhlman B, Rohl CA, et al. Protein–protein docking with simultaneous optimization of rigid-body displacement and side-chain conformation. J Mol Biol. 2003;331:281–99. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00670-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gruswitz F, O'Connell J, Stroud RM. Inhibitory complex of the transmembrane ammonia channel, AmtB, and the cytosolic regulatory protein, GlnK, at 1.96 Å. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:42–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609796104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang J, Sprung R, Pei J, Tan X, Kim S, Zhu H, et al. Lysine acetylation is a highly abundant and evolutionarily conserved modification in Escherichia coli. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2009;8:215–25. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800187-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kessler D, Herth W, Knappe J. Ultrastructure and pyruvate formate-lyase quenching property of the multienzymic AdhE protein of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:18073–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Becker A, Kabsch W. X-ray structure of pyruvate formate-lyase in complex with pyruvate and CoA. How the enzyme uses the Cys-418 thiyl radical for pyruvate cleavage. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:40036–42. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205821200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lv X, Liu H, Ke M, Gong H. Exploring the pH-dependent substrate transport mechanism of FocA using molecular dynamics simulation. Biophys J. 2013;105:2714–23. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2013.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miller J. Experiments in Molecular Genetics. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Begg Y, Whyte J, Haddock B. The identification of mutants of Escherichia coli deficient in formate dehydrogenase and nitrate reductase activities using dye indicator plates. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1977;2:47–50. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pinske C, Sawers RG. The role of the ferric-uptake regulator Fur and iron homeostasis in controlling levels of the [NiFe]-hydrogenases in Escherichia coli. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2010;35:8938–44. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hormann K, Andreesen JR. Reductive cleavage of sarcosine and betaine by Eubacterium acidaminophilum via enzyme systems different from glycine reductase. Arch Microbiol. 1989;153:50–9. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Laemmli U. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–5. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Towbin H, Staehelin T, Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:4350–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shevchenko A, Tomas H, Havliš J, Olsen JV, Mann M. In-gel digestion for mass spectrometric characterization of proteins and proteomes. Nat Protoc. 2007;1:2856–60. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Götze M, Pettelkau J, Schaks S, Bosse K, Ihling CH, Krauth F, et al. StavroX—a software for analyzing cross-linked products in protein interaction studies. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2012;23:76–87. doi: 10.1007/s13361-011-0261-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kalkhof S, Sinz A. Chances and pitfalls of chemical cross-linking with amine-reactive N-hydroxy succinimide esters. Anal Bioanal Chem. 2008;392:305–12. doi: 10.1007/s00216-008-2231-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lowry O, Rosebrough N, Farr A, Randall R. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.