Summary

Nitroreductase from Enterobacter cloacae (NR) reduces diverse nitroaromatics including herbicides, explosives and prodrugs, and holds promise for bioremediation, prodrug activation and enzyme-assisted synthesis. We solved crystal structures of NR complexes with bound substrate or analog for each of its two half-reactions. We complemented these with kinetic isotope effect (KIE) measurements elucidating H-transfer steps essential to each half-reaction. KIEs indicate hydride transfer from NADH to the flavin consistent with our structure of NR with the NADH analog nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide (NAAD). The KIE on reduction of p-nitrobenzoic acid (p-NBA) also indicates hydride transfer, and requires revision of prior computational mechanisms. Our mechanistic information provided a structural restraint for the orientation of bound substrate, placing the nitro group closer to the flavin N5 in the pocket that binds the amide of NADH. KIEs show that solvent provides a proton, enabling accommodation of different nitro group placements, consistent with NR’s broad repertoire.

Keywords: Nitroreductase, flavoenzyme, structure, prodrug activation, remediation

eTOC

Kinetic isotope effects have been combined with two new crystal structures to elucidate the mechanism of nitroreductase, an enzyme crucial to prodrug activation and promising for bioremediation and enzyme-assisted synthesis. The new findings reveal hydride transfer to substrate and supersede a mechanism based on computations.

Introduction

Nitroreductase (NR) from Enterobacter cloacae is a promiscuous enzyme that catalyzes reduction of a variety of nitroaromatic compounds to the corresponding hydroxylaminoaromatics via the intermediary of nitrosoaromatics (Koder and Miller, 1998a; Race et al., 2005). The enzyme was first identified for its ability to reduce TNT (Bryant et al., 1991), but homologues have since been discovered with other activities including BluB and iodotyrosine deiodinase (Bang et al., 2012; Gherasim et al., 2015; Thomas et al., 2009; Yu et al., 2012). These raise the question of how the NR fold is able to support distinct activities in different exemplars, and of how NR is able to specialize in two-electron reduction yet apply this reactivity to diverse substrates.

It is important to understand NR’s mechanism because NR is critical to our ability to combat several devastating pathogens. NR’s action is essential to the efficacy of widely-used antibiotics such as metronidazole and to treatments for stomach ulcers and dysentery (Pal et al., 2009). NRs of gut flora convert nitroaromatic compounds to more toxic products, also raising the incidence of cancer (Guillén et al., 2009). However ongoing efforts to harness NR’s activity to combat cancer demonstrate NR’s promise as an agent for enzymatic activation of prodrugs in therapies and diagnostics (Williams et al., 2015). Optimization of NR/prodrug combinations requires that we understand how the protein binds and activates its substrates, yet structural and mechanistic studies are only available for a few members of this large family (Koder and Miller, 1998a; Pitsawong et al., 2014; Race et al., 2005).

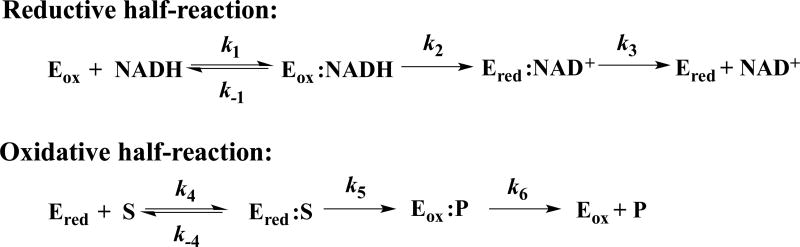

Rapid reaction kinetic studies of NR revealed a simple ping-pong mechanism lacking gating steps able to enforce specificity (Scheme 1) (Pitsawong et al., 2014). Electrons were shown to be transferred pair-wise from NADH to the oxidized flavin and from reduced anionic flavin to nitroaromatic substrates (Koder et al, 2002; Pitsawong et al, 2014).

Scheme 1.

Kinetic mechanism of E. cloacae NR.

It is equally important to understand H transfers involved, as these shape the nature and energetics of the reaction (Massey and Hemmerich, 1980; Schopfer et al., 1991). Substrate reduction by reduced flavin commonly occurs via hydride transfer (Fagan and Palfey, 2010) in which two electrons are transferred as an H−. Yet in NR’s case H equivalents have been proposed to be transferred as solvent-derived protons via electron-coupled proton transfer (Christofferson and Wilkie, 2009; Isayev et al., 2012).

The possibility of hydride transfer depends on the distance between the flavin N5 atom and the atom donating or receiving the H−, with distances ≤ 3.8 Å being optimal (Fraaije and Mattevi, 2000) (Supplemental Fig. S1B for atom numbering). In the E. coli homolog NfsB with nicotinic acid bound, the nicotinic ring was found to stack against the flavin placing the nicotinic C4 3.6 Å from the flavin N5 (Lovering et al, 2001). Therefore, flavin reduction was proposed to occur via a hydride transfer (reductive half reaction). However the absence of the ribitylphosphate-AMP group of NADH from this model allows that the physiological binding mode might be different due to interactions between the protein and the ribitylphosphate-AMP, which play critical roles in NAD(P)H binding in ferredoxin-NADP+ reductase (FNR) and respiratory complex I (Birrell and Hirst, 2013; Deng et al., 1999; Parkinson et al., 2000).

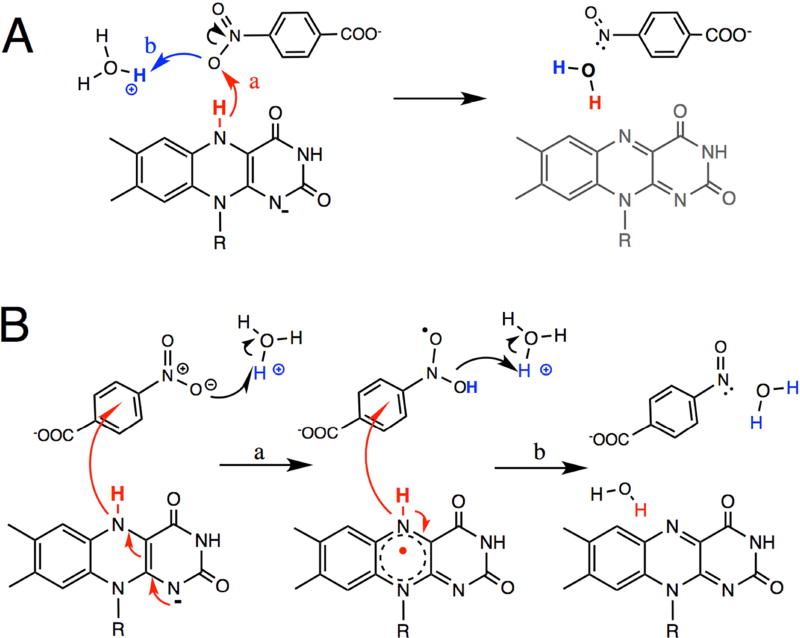

Greater debate is focused on the half-reaction in which the flavin is reoxidized and substrate is reduced (the so-called oxidative half reaction). This has been proposed to occur via serial single electron and proton transfers (Fig. 1B, (Christofferson and Wilkie, 2009; Isayev et al., 2012)) based on the distances involved. Overall, the structures of NR and homologues complexed with oxidizing substrates reveal distances from the flavin N5 to the oxidizing moiety varying from 3.8 – 7.7 Å (Haynes et al., 2002; Hecht et al., 1995; Kobori et al., 2001; Koike et al., 1998; Parkinson et al., 2000; Race et al., 2007; Tanner et al., 1996). Most of these separations are too long to favor transfer of hydride from reduced flavin to the nitro group (step ‘a’ in Fig. 1A), being more compatible with electron transfer from the flavin with protons deriving from different donors (step ‘a’ in Fig. 1B) (Page, 1999). Indeed, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of NfsB and NR found that the substrates CB1954 and nitrobenzene did not remain bound in orientations placing the nitro group near N5, but reoriented or dissociated (Christofferson and Wilkie, 2009; Isayev et al., 2012). Therefore water H-bonded to the ~NOO was proposed to donate protons in conjunction with electron transfer from flavin.

Figure 1. Schematic of two possible mechanisms for nitro-group reduction.

(A) hydride transfer from reduced flavin and proton acquisition from solvent. (B) Transfer of two electrons from reduced flavin each accompanied by acquisition of a proton (Christofferson and Wilkie, 2009). R denotes ribityl phosphate.

Unfortunately, none of the substrate-bound structures of NR represent the reduced state of the enzyme, the state that is catalytically competent, because substrates react immediately upon binding to the reduced state and thereby preclude crystallography. Drug-designers have therefore had to base their strategies on the mode of ligand binding to the oxidized enzyme. However there is evidence that substrate binds differently to oxidized vs. reduced enzyme in NfsB (Race et al., 2005), as in at least one other flavoenzyme (Barna et al., 2001). Substrates’ interactions with the NR protein are relatively few and often mediated by water (Johansson et al., 2003; Race et al., 2005), consistent with substrates’ relatively large Kd values, as well as NR’s capacity to reduce diverse substrates and to reduce a given di-nitro substrate at either of the two nitro positions (Johansson et al., 2003). Thus the NR protein is able to accommodate multiple binding modes.

To clarify this important question we solved crystal structures modeling binding of substrate for each of NR’s half reactions, and paired them with kinetic isotope effect studies to obtain a catalytically-relevant constraint on the distance between the flavin N5 and the substrate nitro group. Our results affirm a different substrate binding mode in the reduced catalytically competent enzyme than in the simpler oxidized models and reveal the source of the second H needed. Thus we elucidate fundamental elements of NR’s mechanism, offer clues as to the basis of its promiscuity and provide information that is essential for efforts to design prodrugs that can bind productively to NR.

Results

Crystal Structures

Structures of NR with bound nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide (NAAD) or p-nitrobenzoic acid (p-NBA) revealed the familiar symmetric dimeric NR fold (Haynes et al., 2002) (Supplemental Fig. S1A, and Table 1 for refinement and statistics). Helices 7 are central to the dimer interface whilst the N- and C-termini of the polypeptide chain tether the two monomers together. This stabilizes the dimer even though substrates and FMN bind between the monomers. Backbone atoms were displaced by an RMSD of only 0.5 Å upon NAAD binding, and 0.6 Å upon p-NBA binding (Supplemental Table S1).

Table 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

| NR•NAAD | NR•p-NBA | |

|---|---|---|

| Data collection# | ||

| Space group | P21 | P21 |

| Cell dimensions | ||

| a, b, c (Å) | 49.4, 113.1, 80.7 | 52.4, 113.4, 82.3 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90.0, 92.6, 90.0 | 90.0,101.6,90.0 |

| Resolution (Å) | 1.85 (1.91–1.85) * | 1.90 (1.97–1.90) |

| Rsym | 0.102 (0.315) | 0.091 (0.270) |

| Rpim | 0.058 (0.189) | 0.060 (0.176) |

| CC1/2 in highest shell (number of pairs) | 0.986 (3060) | 0.885 (3466) |

| I/σI | 15.9 (3.8) | 13.9 (4.6) |

| Completeness (%) | 98.1 (87.8) | 98.3 (97.6) |

| Redundancy | 3.9 (3.1) | 3.3 (3.2) |

| Wilson B-factor | 12.4 | 20.0 |

| Refinement | ||

| Resolution (Å) | 1.85 | 1.90 |

| No. reflections | 71139 | 72793 |

| Rwork / Rfree | 0.175/0.223 | 0.166/0.197 |

| No. macromolecules in a.u. | 4 | 4 |

| No. atoms | ||

| Protein | 6708 | 6708 |

| Ligand/ion | 300 | 172 |

| Water | 1024 | 790 |

| B-factors | ||

| Protein | 20.0 | 27.9 |

| Ligand | 25.7 | 30.5 |

| Water | 29.2 | 37.5 |

| Substrate ligand occupancies (four copies per a.u.) | 0.71, 0.73, 0.77, 0.72 | 0.90, 0.93, 0.94 0.81 |

| No. TLS groups | 22 | 27 |

| R.m.s. deviations | ||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.004 | 0.003 |

| Bond angles (°) | 0.66 | 0.54 |

Each data set was collected from one crystal.

Values in parentheses are for highest-resolution shell.

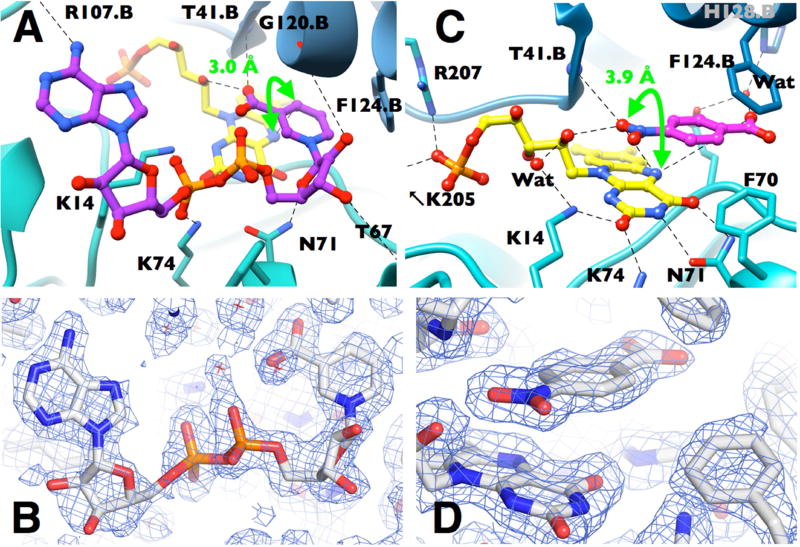

NAAD binds in an extended conformation as in pentaerythritol tetranitrate reductase (PETNR) and FNR (Deng et al., 1999; Pudney et al., 2009). The nicotinic acid ring of NAAD sits deep in the pocket that contains the flavin rings (Supplemental Fig. S2), stacked against the re face of the flavin over the uracyl and diazabenzene rings (Fig. 2a) similar to the binding mode of benzoate and nicotinic acid (Haynes et al., 2002; Lovering et al., 2001). The carboxyl functionality that mimics the carboxamide of NADH interacts with the backbone HN of Thr41.B and the 2’ ribityl OH (2.7 and 2.8 Å respectively and .B indicates residues from the other monomer). The side chain of Phe124.B interacts with the nicotinamide ring (Fig. 2A) (McGaughey et al., 1998). Phe124.B was identified as conferring NR activity as opposed to flavin reductase activity by Zenno et al. (Zenno et al., 1996) and was associated with substrate specificity by Grove et al. (Grove et al., 2003). A few bulky side chains reorient to make way for the nicotinamide, in particular Phe124.B and Phe70 (Supplemental Fig. S3 (Haynes et al., 2002)). These features are conserved in several other NR homologues (Isayev et al., 2012; Johansson et al., 2003; Koike et al., 1998) suggesting that the active site’s capacity to accommodate substrates is conserved and thus that substrate promiscuity may be an evolved property of these enzymes. The placement of the nicotinic acid ring is similar to that observed for E. coli NfsB (Lovering et al., 2001) but with a tilt imposed by attachment to the ribose chain of NAAD in our case.

Figure 2. Binding modes of model substrates for each of NR’s two half reactions.

(A) NAAD•NR with NAAD in purple and FMN in yellow (CPK heteroatoms). (B) Electron density for bound NAAD (SIGMAA weighted 2FO-FC, contour level 0.7 σ). (C) p-NBA•NR with p-NBA in pink depicted with the ~NOO group over the flavin. (D) Electron density for bound p-NBA (SIGMAA weighted 2FO-FC, contour level 1.2 σ). In panels A and C steel blue vs. teal distinguish the two monomers. Interactions mentioned in the text and < 3.5 Å are indicated by dashed lines; distances are provided in Table S2. Distances corresponding to the proposed hydride transfers are indicated with bright green arrows.

The two sugars and phosphates of NAAD bind in a cleft in the protein surface, consistent with their hydrophilicity (Fig. 2A and Supplemental Figs. S2, S4). Weak interactions with the backbone at Gly120.B and Thr67 and with the side chain of Asn71 engage the ribose hydroxyls (3.2 – 4 Å). The dominant interactions stabilizing the phosphates are with the conserved side chains of Lys14 and Lys74 (3.1 and 2.8 Å, respectively, Fig. 2A and Supplemental Fig. S4). These residues also interact with the N1-O2 locus of the flavin, which becomes more negative upon flavin reduction (Supplementary Fig. S2, (Koder and Miller, 1998a; Race et al., 2005)). The phosphate that would be attached to the 2’ adenosine ribose of NADPH would project into solution, consistent with a KM similar to that of NADH (Koder and Miller, 1998a). The adenine ring is bound in all four active sites in the unit cell with a side-to-side position that varies some 0.2 Å consistent with only one interaction with a backbone functionality (adenine amine -carbonyl O of Arg107.B, 2.9 Å, Fig. 2A and Fig. S4). This contrasts with the case of FNR where the adenine of NADH binds tightly to the protein but a Tyr ring stacked against the flavin impedes nicotinamide binding (Deng et al., 1999). In the NAAD•NR complex, refined thermal factors for the nicotinic acid are smaller than those of the adenine and sugar-phosphate, consistent with more extensive interaction with protein and FMN cofactor. The distance from the NAAD C4 to the N5 of NR’s flavin is 3.0 Å (Fig. 2A, Table S2) vs. 3.6 Å for nicotinic acid bound to NfsB (Lovering et al., 2001), indicating that flavin reduction can occur by hydride transfer from NADH and that interactions with the ribityl phosphate AMP significantly improve the proximity of the NADH C4 to the flavin N5.

p-NBA has been used for extensive mechanistic studies because it is a poor substrate and thus makes the chemical step(s) rate-limiting (Koder and Miller, 1998a; Pitsawong et al., 2014). To provide molecular details of p-NBA’s interaction with the protein, we solved the crystal structure of the oxidized p-NBA•NR complex. Binding of p-NBA occurs via H-bonds and pi stacking above the re face of the flavin, as for other substrates and analogs in the active sites of NR and NfsB (Fig. 2C, (Haynes et al., 2002; Race et al., 2005)). Because the crystallographic data do not distinguish the ~COO− group from the ~NOO group of p-NBA, the structure was refined using each of the two possible orientations of p-NBA. However the resulting B-factors and distances were not significantly different (Supplemental Table S2) so we retain generality by referring to the ~COO− and ~NOO as the proximal ~XOO (closer to N5) and the distal ~XOO (further from N5). The proximal ~XOO interacts with the backbone of Thr41.B plus the ribityl 2’OH (2.8 and 2.7 Å, respectively), a tilted stacking arrangement with the side chain of Phe124.B engages the benzene ring (McGaughey et al., 1998), and the distal ~XOO enjoys a 2.7 Å H-bond with a crystallographic water observed in all four active sites which in turn interacts with the NE2 of His128.B (2.7 Å) as well as the side chain of Glu165 (2.9 Å, Fig. 2C, Table S2).

The proximal ~XOO might be thought to be ~COO− based previous work showing that benzoic acid and acetate bind with their ~COO− in that position (Haynes et al., 2002). This would be consistent with electrostatic attraction to nearby side chains of Lys14 and 74 (Fig. 2C, Fig. S5). But the ~NOO functionality is also strongly electronegative and expected based on DFT calculations to bear a net charge of −.33 (vs. −.84 for the carboxylate) even in singly ionized p-NBA (Supplemental Fig. S6). Thus the orientation in which ~NOO is proximal to N5 and directed towards the Lys’ cannot be ruled out on these grounds.

Multiple binding orientations have been observed in NfsB’s active site based on crystal structures of the oxidized enzyme with CB1954 or a dinitrobenzamide prodrug, and these placed nitro groups at distances of 3.9 to 7.4 Å from N5 (Johansson et al., 2003). In NR, if ~NOO occupies the distal position its closest N-bound O would be 5.6 Å from the flavin N5 whereas in the proximal position, it’s closest N-bound O would be only 3.9 Å from N5, within error of close enough for hydride transfer (Fraaije and Mattevi, 2000). Therefore, to resolve the conundrum we interrogated the mechanism of p-NBA reduction, because evidence of hydride transfer from the flavin would constitute demonstration that the ~NOO group must be proximal to N5, in the reduced state of NR.

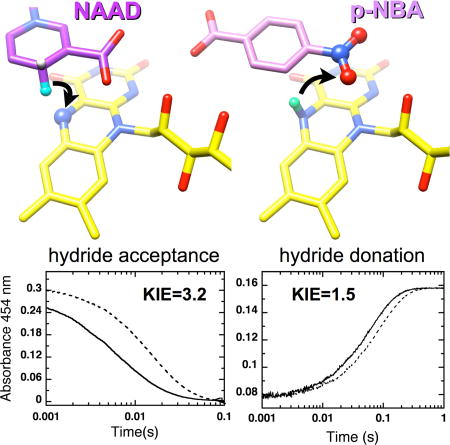

Primary Kinetic Isotope Effects (KIE)

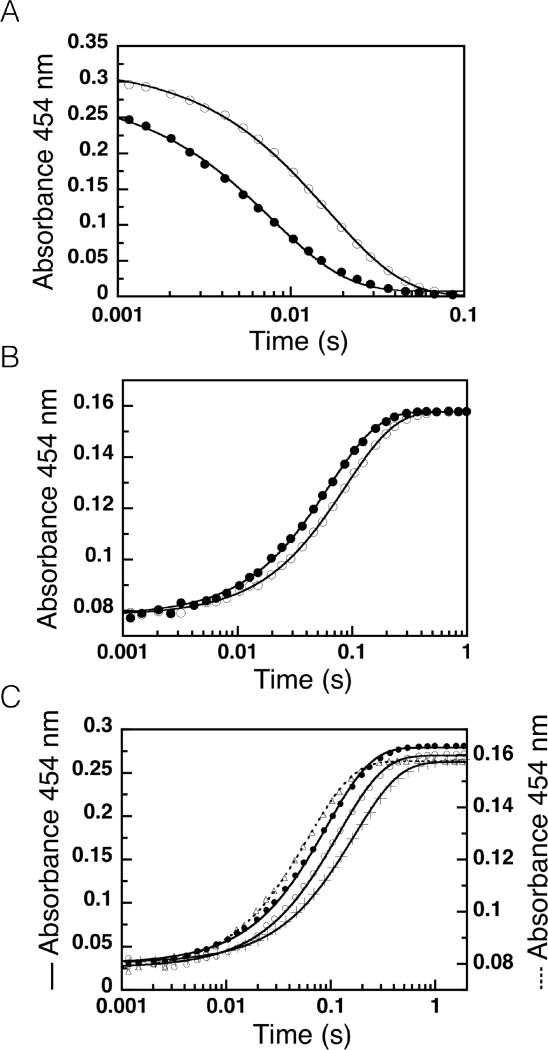

First we probed the source of H acquired by the flavin as part of reduction, by comparing the rate constants for reduction of oxidized NR by [4R-2H]NADH vs. by NADH via stopped flow spectrophotometry monitoring oxidized flavin at 454 nm. Data were analyzed according to the model in Scheme 1 and gave rise to observed rate constants of 75 ± 2 s−1 and 238 ± 3 s−1 for [4R-2H]NADH and NADH, respectively (Fig. 3A) and an observed primary kinetic isotope effect of k2H/k2D = 3.2 ± 0.1 (Table 2). This value is very close to those obtained for morphinone reductase (MR) and PETNR and indicates that NR employs hydride transfer from NADH to the N5 position of flavin (Basran et al., 2003; Pudney et al., 2009) and this step is the rate limiting step in the reductive half-reaction (Pitsawong et al., 2014).

Figure 3. Kinetic isotope effects on NR’s rapid reaction kinetics.

(A) Reductive half-reaction of NR Kinetic traces of the reduction of NR with NADH (●) or [4R-2H]NADH (○) at 4°C (17.5 µM and 100 µM after mixing). Parameters of the fits appear in Table 2. (B) Oxidative half-reaction of NR reduced using NADH (●) or [4R-2H]NADH (○) then mixed with p-NBA (13 µM, 13 µM, 2 mM after mixing). (C) Water access to the active site revealed by comparison of the oxidative half reaction of reduced NR in H2O buffer with 9% (w/v) glycerol mixed with p-NBA equilibrated in the same buffer (17.5 µM and 2 mM after mixing, kobs = 11.5 ± 0.1 s−1 , ●) vs. the reaction with p-NBA equilibrated in D2O buffer (kobs = 9.0 ± 0.1 s−1, ○) vs. the result of mixing NR with p-NBA both in D2O buffer (kobs = 6.1 ± 0.1 s−1, +). Triangles (Δ) show the reaction of reduced NR and p-NBA both equilibrated in H2O buffer without 9% glycerol. Only every 20th data point is shown for clarity.

Table 2.

Primary, solvent, and double kinetic isotope effects on NR kinetics.a

| Rapid Reaction Kinetics | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Reductive-half reactionb

|

Oxidative-half reactionc

|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|||||||

| 238 ± 3 | 75 ± 2 | 16.4 ±0.06 | 11.5 ±0.05 | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| Primary KIE | Primary KIE | |||||||

|

|

|

|||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 3.2 ±0.1 | 1.4 ±0.01 | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Steady-State Kinetics.d | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| kcat (H2O buffer), s−1 | kcat (D2O buffer), s−1 | |||||||

|

| ||||||||

| NADH | NADD | NADH | NADD | |||||

|

|

|

|||||||

| 9.1 ±0.4 (a) | 6.3 ±0.3 (b) | 6.8 ± 0.3(c) | 4.5 ±0.2 (d) | |||||

|

| ||||||||

| Primary KIE | Solvent KIE | Double KIE | ||||||

|

|

|

|||||||

| NADH/NADD (H2O buffer) (a/b) | NADH/NADD (D2O buffer) (c/d) | H2O/D2O (NADH) (a/c) | H2O/D2O (NADD) (b/d) | a/d | ||||

|

|

|

|||||||

| 1.4 ±0.1 | 1.5 ±0.1 | 1.3 ±0.1 | 1.4 ±0.1 | 2.0 ±0.2 | ||||

Rate constants are defined in terms of the mechanism provided in scheme 1.

Reactions were carried out at 4°C.

Reactions were carried out at 25°C.

Assays were performed at 25 °C.

The oxidative half-reaction was studied via double mixing experiments. To test for hydride transfer from the flavin N5 oxidized NR was first mixed with either [4R-2H]NADH or NADH to generate reduced flavin deuterated or proteated at the N5 position, respectively. The resulting solution was then mixed with p-NBA and the kinetic traces recorded are shown in Figure 3B. Rate constants of 11.5 ± 0.05 s−1 and 16.4 ± 0.06 s−1 were obtained yielding an observed primary kinetic isotope effect of k5H/k5D = 1.4 ± 0.1, somewhat smaller than expected for a hydride transfer. However no partially-oxidized flavin intermediate is observed so flavin oxidation involves loss of a pair of electrons and the H nucleus transfer represented by this primary KIE is assigned to hydride transfer.

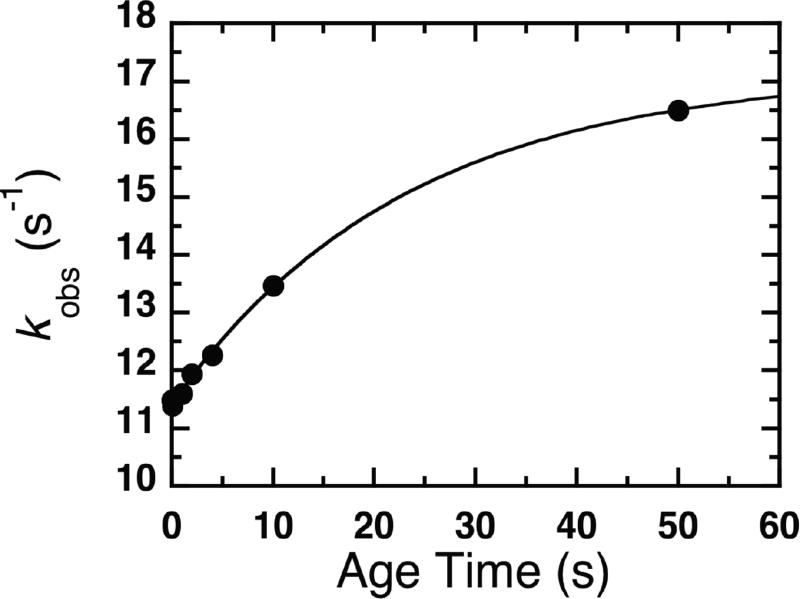

To investigate the possibility that exchange of the reduced flavin N5-2H with proteated solvent is responsible for the small observed primary KIE, we carried out double-mixing experiments using a range of aging times to allow the proposed solvent exchange to decrease deuteration at N5. The observed rate constants increased with increasing ageing time consistent with a rate of solvent exchange of 0.048 ± 0.001 s−1, an [N5-2H]-FMN oxidation rate of 11.4 ± 0.02 s−1 and an FMN oxidation rate of 17.0 ± 0.08 s−1 (Fig. 4). These results indicate a primary KIE of 1.50 ± 0.01 upon accounting for solvent exchange.

Figure 4.

Rate of solvent exchange of the N5-2H of NR reduced by [4R-2H]NADH. Reduced NR containing [N5-2H]-FMN was subject to H/D exchange with H2O for a range of aging times before the rate of flavin reoxidation was measured yielding an exchange rate of kH/D = 0.048 ±0.001 s−1, with and .

Thus the primary KIE on NR oxidation is modest, compared to the values of 3.5 and 3.1 reported MR and PETNR (Basran et al., 2003; Pudney et al., 2009). This is consistent with kinetic complexity and/or non-ideal geometry (Roston et al., 2013; Westheimer, 1961).

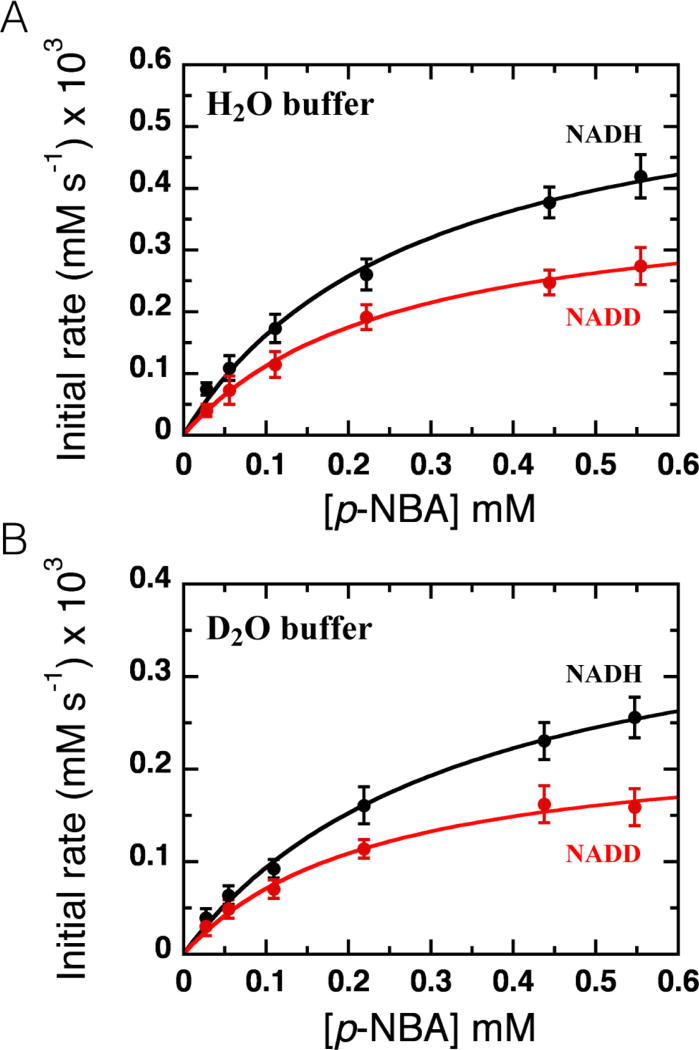

KIEs on Steady-State Kinetics: Primary KIE

Since our primary KIE for the oxidative half reaction of NR was small, we also evaluated it via steady-state kinetic measurements, exploiting the fact that the oxidative half reaction is the rate-limiting step in overall turnover (Pitsawong et al., 2014). The primary KIE values were calculated as the ratio of the rates of catalytic turnover kcatNADH/kcatNADD and are listed in Table 2. The primary KIE in H2O buffer was 1.4 and 1.5 in D2O buffer (Fig. 5), in agreement with the rapid reaction kinetics result. The primary KIE on kcat/KM was 1.3 in H2O and in D2O it was the same within error at 1.2, confirming that kcat captures the rate-limiting step. Finally, the steady-state-derived kcat of NR is pH-independent in the range of pH 7.0 – 8.25 (Supplemental Fig. S7) indicating that any differences in the degree of ionization of deuterated vs. proteated groups are not the basis for the small primary KIE we observe. Thus we confirm a primary KIE of 1.4 – 1.5 ±0.1 for the oxidative half reaction.

Figure 5. Steady-state kinetic isotope effects.

Reactions were performed in (A) H2O buffer with 9% (w/v) glycerol or (B) D2O buffer and a range of p-NBA concentrations at 280 µM NADH (> 8 times the (black circles) or [4R-2H]NADH (red circles). Fits to the Michaelis-Menten model yielded kinetic parameters of of 0.28 ± 0.04 mM, and of 0.26 ± 0.03 mM with kcatvalues of Hkcatof 9.1 ± 0.4 s−1 and Dkcatof 6.3 ± 0.3 s−1 for reactions in H2O buffer with 9% (w/v) glycerol. In D2O buffer yielded , and with kcat values of Hkcat = 6.8 ± 0.3 s−1 and Dkcat= 4.5 ± 0.2 s−1.

Solvent KIE

Steady-state kinetics were also used to investigate the solvent KIE and thereby test for participation of a solvent-derived proton in a rate-contributing step of the reaction in which NR becomes re-oxidized (Fig. 1 and Fig. 5). The catalytic turnover rate of NR using NADH and p-NBA as substrates in H2O buffer with 9% glycerol (w/v, to replicate the viscosity of D2O) was 1.3-fold higher than the value in D2O. A somewhat larger solvent KIE was observed when KIE was measured with [4R-2H]NADH (SKIE = 1.4, Table 2). In both cases the SKIE was >1, demonstrating that a proton derived from solvent participates in a rate-contributing step during the reduction of p-NBA.

The double KIE reveals whether hydride transfer from the flavin N5-H and transfer of the solvent-derived proton are concerted (via a single transition state, Fig. 1A) or occur in different kinetic steps (distinct transition states) (Belasco et al., 1983). By dividing the catalytic turnover rate obtained from the experiment using NADH in H2O buffer by the catalytic turnover rate obtained using [4R-2H]NADH in D2O buffer we obtain a double KIE of 2.0. This is within error of the product of the primary and solvent KIEs (KIE × SKIE = 1.5 × 1.3 = 2.0) (Table 2) suggesting that hydride transfer from N5-H of reduced flavin to the nitro-group of p-NBA and acquisition of the solvent-derived proton constitute a single concerted event (Fig. 1A).

Water Accessibility

The SKIE demonstrates that a proton derived from solvent participates in the rate-limiting step, but the pH independence between pHs 7.0 and 8.25 argues against bulk solvent as the proton source. However the crystal structures reveal ample space for water molecule(s) within the active site, where their protonation state(s) will be modulated by local interactions.

To learn whether a proton could be acquired from bulk solvent on the time scale of the reaction, single-mixing stopped-flow experiments were used. When reduced NR equilibrated in H2O buffer was mixed with p-NBA in H2O buffer the rate of NR oxidation was 1.3 times faster than when reduced NR was mixed with p-NBA in D2O buffer (Fig. 3C), indicating that H+ not present in the active site prior to mixing contributes to the observed rate. The same conclusion was supported by reacting reduced NR in D2O buffer with 2 mM p-NBA equilibrated in either H2O or D2O. While we cannot calculate KIEs from these experiments that produced mixtures of H2O and D2O, it is nonetheless clear that the isotopic content of bulk solvent affected the reaction rate regardless of whether NR’s flavin was proteated or deuterated at N5. Since the solvent exchange rate of the N5-H was 100 times slower than the reaction in these rapid-mixing experiments ( , Table 2, Fig. 4), the isotope effect revealed in Figure 3C must reflect the other H: the solvent-derived proton. Thus solvent in NR’s active site exchanges protons with bulk solvent at a rate of at least 16 s−1 consistent with conduction via active site water molecules with ready access to bulk solvent.

Discussion

Our crystal structure of NR complexed with NAAD makes sense of mechanistic observations. It contrasts with the precedent of the NR ortholog from Vibrio harveyi in which the nicotinamide of NAD+ is stacked on the adenine and away from the flavin (Tanner et al., 1999). Instead, our structure finds that NAAD is bound in an extended conformation (Berrisford and Sazanov, 2009) with its nicotinic ring against the face of the flavin, consistent with observations in other flavoenzymes (Pai et al, 1988), the stereochemistry of hydride transfer in NR (Koder and Miller, 1998a) and competitive inhibition of NR’s reductive half reaction by benzoate which also binds there (Haynes et al, 2002).

The KM for NADH is only two-fold lower than that of reduced nicotinamide monophosphate (Koder and Miller, 1998a), consistent with observed weak interactions with the adenosine component of NAAD. Whereas the three residues, Asn71, Lysl4, and Lys74, that make polar contacts with the sugar phosphate portion of the bound NAAD are conserved or similar in NR homologues, suggesting that NADH binding is similar among family members (Fig. 2A).

The C4 of NAAD is 3.0 Å from the flavin N5 in a position that should promote orbital overlap between the nicotinamide C4 hydrogen of NADH and the N5 of the isoalloxazine ring (Fig. 2A) (Fraaije and Mattevi, 2000; Mesecar, 1997). There are no ordered water molecules near the hydride-donating C4 and it is screened from bulk solvent by Phe124.B, Glu165 and Gly166, in support of efficient hydride transfer to FMN. These results and the >95% stereospecificity of proR hydrogen transfer from C4(Koder and Miller, 1998a) confirm our conclusion of direct hydride transfer to FMN.

Whereas both FNR and respiratory complex I bind the adenine portion of NADH tightly but not the nicotinamide moiety (Birrell and Hirst, 2013; Deng et al., 1999), the reverse is true in NR, which has a weaker less specific interaction with the adenine, as for MR (Barna et al., 2002). Indeed, NAD+ does not compete with substrates that oxidize reduced NR, indicating that affinity for the ADP ribose portion is too low to produce binding on its own (as in bipartite binding (Pudney et al., 2009)).

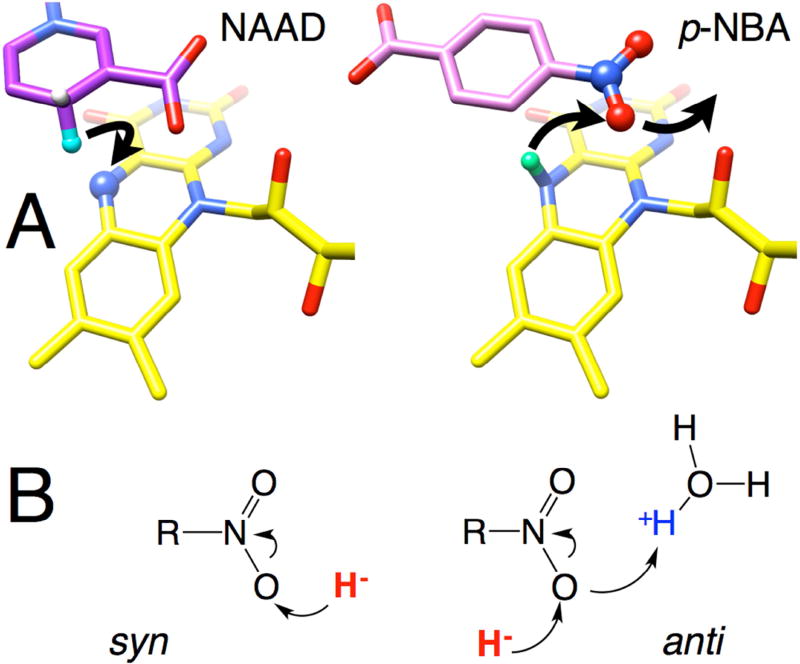

Understanding the structure of the p-NBA•NR complex is less straightforward. Although p-NBA binding appears to elicit protein adjustments it does not produce optimal placement of the substrate for reactivity: regardless of which orientation is assumed for bound p-NBA either the distance to the flavin N5 or the orientation of the N5 to N-bound O vector is non-ideal (Fig. 2C and Fig. 6). Therefore we characterized the KIEs of the oxidative reaction, with the reductive reaction serving as a reference-point and control. For the reduction of NR, the robust KIE of 3.2 indicates that two electrons are transferred from the C4 of NADH to the flavin as hydride in a rate-limiting step, consistent with our crystal structure. This agrees with established mechanisms among flavoenzymes and NR’s primary KIE falls within the range observed for flavin reductase from Photobacterium leiognathi (Lux G) (primary KIE > 3.9 (Nijvipakul et al., 2010)), MR (primary KIE of 4.4 (Basran et al., 2003)) and NADPH-cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase (primary KIE of 2.7 (Shen et al., 1999)). Thus NR’s active site is able to position NADH well relative to the flavin, and non-optimal positioning appears to be specific to the oxidative half reaction.

Figure 6. Depiction of proposed hydride transfers to and from flavin N5 in structures of NAAD•NR and p-NBA•NR.

(A) Arrows indicate a plausible course of hydride transfer from NADH C4 to flavin N5 (left) and then from flavin N5 to the nearest nitro O of p-NBA (right). Reacting atoms are depicted as balls with the H of NAAD equivalent to the hydride of NADH in aqua, and the N5H of reduced flavin in mint green. Flavin is in yellow NAAD is in purple, p-NBA is in pink, with heteroatoms colored in CPK. H atoms were added in chimera and are shown for illustrative purposes only, see Methods for details.

The oxidation of NR (reduction of p-NBA) displayed only a modest primary KIE of 1.4–1.5. H/D exchange at N5-FMNred was documented but did not explain the small KIE. A similar primary KIE of only 2 was observed for complex I and was attributed to hydride transfer’s being only partially rate-determining (Birrell and Hirst, 2013) and a primary KIE of ~1.5 was also observed in the flavin-oxidizing half-reaction of choline oxidase (Gannavaram and Gadda, 2013). More detailed studies are required to establish whether the chemical step is solely responsible for our primary KIE, however this interpretation is strengthened by the similarity of the KIEs on kcat and on kcat/KM. Moreover its modest magnitude is not surprising given the unfavorable geometry revealed by our crystal structure (Westheimer, 1961) including the relatively long distance of 3.9 Å between N5 and the nearest nitro O, in addition to the orientation of the hydride from N5 which does not point towards the nearer O (Fig. 2C and Fig. 6). Indeed, the placement of the nearest nitro O relative to the flavin N5 is most compatible with anti transfer of hydride as opposed to the more favorable and common syn transfer (Fig. 6B, (Nishino and Nakata, 2007)). However the geometry allows that the required proton could be acquired from an active site solvent molecule or a proton temporarily resident near N1 via favorable syn proton transfer. Thus, our crystal structure of p-NBA•NR is compatible with the small primary KIE of the oxidative half reaction.

NR’s solvent KIE (SKIE) of 1.3–1.4 indicates that a proton is derived from solvent in the oxidative half reaction. Moreover, a double deuterium KIE was observed confirming the solvent effect. Our double deuterium KIE, supports concerted transfer of H− and H+ in the reduction of p-NBA by NR (steps “a” and “b” in Fig. 1A). However we caution that within a family of enzymes, or even for a given enzyme but comparing different substrates, the mechanism of substrate reduction can differ, as demonstrated by the examples of PETN which executes 2-cyclohexanone reduction via a concerted reaction (Basran et al., 2003) whereas old yellow enzyme undergoes stepwise reaction with nitrocyclohexene, with hydride transfer occurring before proton transfer (Meah and Massey, 2000). Thus our finding for reduction of p-NBA by NR is predictive rather than prescriptive for other substrates. Moreover the proton responsible for the SKIE was not pre-localized in the enzyme active site as shown by our water accessibility experiment, and therefore could derive from a differently-placed water in the case of a different substrate, and contribute to NR’s ability to reduce diverse substrates.

Our data do not establish which orientation of p-NBA applies in the oxidized enzyme crystal structure, although benzoate places its carboxyl group where we conclude the nitro group of p-NBA binds in reduced NR. However alteration of the orientation of substrate upon reduction of the flavin has been documented in the case of PETNR (Barna et al., 2001) and also for NfsB (Race et al., 2005). Therefore, the oxidized-state structure is less informative of mechanism than our demonstration of a clear primary KIE pointing to hydride transfer. Neither of the possible orientations for p-NBA binding produced good geometry for hydride transfer, in contrast to the excellent geometry obtained for NAAD. Nitro O atoms are prevented from occupying the optimal position of NAAD’s C4 because p-NBA’s ~NOO binds in the same location as the carboxyl of NAAD (Fig 2). Thus we speculate that NR’s capacity to reduce nitro groups on aromatic rings could have evolved from such compounds’ abilities to bind via similarity with NADH’s amide group on a pyridine ring, in combination with the thermodynamic ease with which ~NOO is reduced.

Our kinetic data show that hydride transfer is the predominant pathway for flavin reduction in NR, and that this is also applicable to p-NBA nitro group reduction. We therefore submit that the orientation of p-NBA inferred by analogy to benzoate and based on MD simulations is deceptive, insufficiently constrained by NR’s promiscuous multi-binding mode active site, and biased by the use of the oxidized state of the enzyme for crystallography and starting points for computation. Instead, our KIE studies probe the catalytically competent reduced state. Our refinement of the p-NBA•NR structure assuming that the ~NO2 is placed closest to the flavin is fully compatible with our diffraction data and results in a distance of 3.9 Å from nitro O to N5 that is compatible with our kinetic results (Fig. 2C). Therefore we conclude that in reduced NR, the ~NO2 is closest to N5. Our approach of combining KIE measurements with structural elucidation demonstrates a strategy whereby structural models can be tested for catalytic relevance, and efforts to engineer the active site can be better informed by mechanistic insights.

STAR Methods

Contact for Reagent and Resource Sharing

Requests for further information, resources and reagents should be directed to the Lead Contact, Prof. Anne-Frances Miller, Department of Chemistry at the University of Kentucky, Lexington KY, U.S.A. 40506-0055, afmill3r2@gmail.com

Method Details

Reagents and Proteins

NADH (100% purity) was purchased from Roche. NAD+ (100% purity) was from Boehringer Ingelheim, Germany. p-nitrobenzoic acid (p-NBA) was from Acros Organics. Deuterium oxide (99.9% purity), ethanol-d6 (99% purity), and sodium deuteroxide solution were from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories.

[4R-2H]NADH was synthesized according to the procedure described by Nijvipakul et al. (Nijvipakul et al., 2010). In brief, 25 mg of yeast alcohol dehydrogenase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Sigma-Aldrich) and NAD+ were combined in 5 mL of 0.1 M NH4HPO3 buffer, pH 8.0 containing 0.3 mL ethanol-d6 and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min or until the reaction was complete. The formation of [4R-2H]NADH was monitored at 340 nm. Amicon® Ultra Centrifugal Filters – 10K (Millipore) were used to remove alcohol dehydrogenase from the resulting solution. The filtrate was diluted 5-fold with deionized water and loaded onto a 40 ml DEAE-Sepharose column, DE-52 (GE Healthcare) pre-equilibrated with deionized water. [4R-2H]NADH was eluted using a 300 mL gradient of 0–0.2 M NH4HCO3, pH 8.0. Pooled fractions containing [4R-2H]NADH with A260/A340 ≤ 2.6 were combined. The purified [4R-2H]NADH was analyzed by 1H NMR spectroscopy (400 MHz), lyophilized to a dry powder and stored at −20°C until used. Concentrations of reagents were determined using the extinction coefficients at pH 7.0: ε340 = 6.22 × 103 M−1cm−1 for NADH and [4R-2H]NADH, ε260 = 17.8 × 103 M−1cm−1 for NAD+ (Nijvipakul et al., 2010), ε273 = 10.1 × 103 M−1cm−1 for p-NBA.

Protein Purification

Wild-type NR was expressed from E. coli BL21(DE3) cells harboring the plasmid pRK1 containing the NR gene. A 50 mL overnight culture of Luria-Bertani broth medium (LB) containing 50 µg/mL kanamycin that had been grown at 37°C overnight shaking at 220 rpm was the source of a 5 mL inoculum added to 2 L of LB medium also with kanamycin. This culture was grown until the OD600 reached ~0.8, at which point protein expression was induced by addition of IPTG to a final concentration of 1 mM. The culture was incubated for a further 3 h at 37°C and then the cells were harvested by centrifugation at 9,000 rpm and 4°C for 10 min and stored at −20°C after washing once with lysis buffer (extended details of this procedure can be found in Zhang, 2007). Frozen cell pellet was resuspended in 100 mM Tris buffer (pH = 7.5) containing 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT (dithiothreitol), 1 mg/ml pefablock SC (Sigma- Aldrich), 0.1 mM FMN and 0.2 mg/ml lysozyme. Cells were ruptured by sonication on ice then centrifuged to remove debris. The protein solution was loaded onto a 2 × 50 cm DE-52 anion-exchange column (GE Healthcare) and eluted with a 0 – 500 mM NaCl gradient in 10 mM Tris buffer (pH=7.5) containing 0.02% NaN3, 1 mM DTT, 0.2 mM EDTA. NR-containing fractions were identified based on absorbance at 280 (protein) and 454 nm (FMN) and SDS-PAGE (sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis) and were pooled and concentrated to a volume less than 10 mL using a Millipore Amicon® Ultra-15 centrifugal filter device (10 kDa cutoff). The concentrated enzyme was loaded onto a Sephacryl S-200 gel filtration column (450 mL, 2.5 mm in diameter) pre-equilibrated with 50 mM KH2PO4, 50 mM KCl, 1 mM DTT, 0.2 mM EDTA, 0.02% NaN3, pH 7.50. NR-containing fractions were identified based on absorbance at 280 and 454 nm and SDS-PAGE, and pooled. The pooled fractions were then concentrated until the enzyme concentration was 1 mM using a Millipore Amicon® Ultra-15 centrifugal filter device (10 kDa). The enzyme was stored at 4°C until used. Fully flavinated NR was identified based on a ratio of A280/A454 < 4.5. The concentration of holo NR was estimated using the extinction coefficient, ε454 = 14.3 × 103 M−1cm−1 (Koder and Miller, 1998b)..

Protein crystallization

Purified NR at 4–5 mg/ml was dialyzed against 10 mM HEPES (pH 7) and 50 mM KCl prior to crystal growth. Crystals of NR with bound nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide (NAAD) were produced by first growing crystals of oxidized NR as described previously (Haynes et al., 2002) and then soaking in the NAAD ligand at increasing concentrations, which avoided damage to the crystals. Crystals of oxidized NR complexed with p-NBA were grown by the hanging drop vapor diffusion method after mixing the protein 1:1 with a well solution containing 100 mM homopipes (pH 4.8), 13% w/v PEG-4000, and the ligand p-NBA at a concentration of 20 mM.

Crystal preparation

In preparing NR-NAAD complex, crystals were first dialyzed against 100 mM homopipes (pH 4.8), 20% w/v PEG-4000, 3% w/v glycerol, and 100 µM NAAD for 16 hours. The crystals were then transferred to 100 mM homopipes (pH 4.8), 20% w/v PEG-4000, 6% w/v glycerol, and 500 µM NAAD for 1.5 hours followed by dialysis against 100 mM homopipes (pH 4.8), 20% w/v PEG-4000, 12% w/v glycerol, and 1 mM NAAD for 1.5 hours. The crystal were harvested and immediately preserved by flash cooling in liquid nitrogen (Rodgers, 1997).

NR-p-NBA crystals were prepared for data collection by dialyzing them against a solution containing 100 mM homopipes (pH 4.8), 25mM p-NBA, 20% w/v PEG-4000, and 12% glycerol w/v for four hours prior to flash cooling in liquid nitrogen. Dialysis in the cryoprotectant solution for longer than four hours destabilized the crystal lattice.

Data collection and processing

Oxidized NR:NAAD crystals were held at 115 K throughout data collection (wavelength 0.9793 Å) on beamline 19-ID at the Advanced Photon Source (APS), Argonne National Laboratory, Argonne, IL. Data frames were processed and reduced with the HKL2000 and CCP4 packages (Otwinowski and Minor, 1997). Oxidized NR:p-NBA crystals were held at 115 K throughout data collection (wavelength 0.900 Å) on beamline 14-ID-B at the APS. Data frames were processed and reduced with the HKL2000 and CCP4 packages. Crystal and data parameters for both samples are listed in Table I. In both cases, there are four monomers, or two dimers, in the asymmetric unit.

Structure determination and refinement

Structure determination of the p-NBA•NR complex was performed by molecular replacement with the CNS software package using the coordinate set of the acetate•NR complex (Haynes et al., 2002) as the search object (Brünger et al., 1998). The NAAD•NR complex structure was determined by molecular replacement using the protein model from the refined p-NBA complex. For both crystal structures, manual building was done in Coot (Emsley and Cowtan, 2004) and final refinement was carried out in with the PHENIX package (Adams et al., 2010). Geometry restraints for all ligands were taken from the Grade server (v1.102, http://grade.globalphasing.org) precompiled library. The FMN restraints were modified to allow butterfly-like bending of the isoalloxazine ring system at the N5 and N10 positions and to give more standard phosphorous-oxygen bond distances for the phosphate group. Additional minor modifications to ligand geometry restraints were made based on searches of the Cambridge Structural Database and Protein Data Bank validation reports.

The resolution and data quality were sufficient for refinement without applying non-crystallographic symmetry restraints. Refinement parameters for both models are summarized in Table 1. For both structures, 99 % of the residues are in the Ramachandran favored regions with no outliers. A summary of data and model parameters is found in Table 1.

Rapid Reaction Kinetics

The kinetic isotope effects (KIEs) on NR’s reductive and oxidative half-reactions were studied using a stopped-flow spectrophotometer (TgK Scientific). The flow system was made anaerobic by rinsing with an anaerobic buffer and incubating overnight with a solution of sodium dithionite in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer pH 7.50. The buffer used for the sodium dithionite solution was sparged with N2 and then equilibrated overnight to remove oxygen in an anaerobic glove-box (M BRAUN UNIlab glovebox with Siemens Corosop 15 controller) before use. Sodium dithionite was added to the anaerobic buffer inside the glove-box and the resulting 50 mM solutions were transferred into tonometers. The dithionite solution-containing tonometers were mounted on the stopped-flow apparatus and used to flush the flow system, which was then allowed to stand overnight with dithionite solution throughout. Prior to experiments, the instrument was rinsed thoroughly with anaerobic buffer comprised of 50 mM potassium phosphate pH 7.50 equilibrated with N2 gas that had been passed through an oxygen-removal cartridge (Labclear). Reductive half-reaction experiments were performed at 4°C to slow down the reduction rate whereas the oxidative half-reaction was characterized at 25°C.

Primary Kinetic Isotope Effects (KIEs)

The kinetics of the reductive half-reaction in which NR becomes reduced were investigated at 4 °C using a stopped-flow spectrophotometer (Pitsawong et al., 2014). A solution of (oxidized) 35 µM NR was made anaerobic by equilibration in the anaerobic glove-box for 30 min then placed in a glass tonometer. All buffer and substrate solutions were made anaerobic by sparging with N2 gas that had passed through an O2-removing cartridge. Substrate solutions (200 µM NADH or [4R-2H]NADH) were loaded in tonometers, which in turn were mounted on the stopped-flow spectrophotometer along with the NR solution. Upon rapid mixing of the enzyme with a substrate, NR reduction was monitored by measuring loss of absorbance at 454 nm. After mixing, the final concentration of the enzyme was 17.5 µM, and the concentration of NADH or [4R-2H]NADH was 100 µM.

The oxidative half-reaction in which NR becomes re-oxidized was monitored at 25°C using double-mixing mode on the stopped-flow spectrophotometer under anaerobic conditions (Pitsawong et al., 2014). A solution of 52 µM oxidized NR was first mixed with 52 µM NADH or [4R-2H]NADH to generate proteated or deuterated reduced NR, respectively. The solution was aged for 0.01 s or 1 s (NADH or [4R-2H]NADH, respectively) to generate NR-bound flavin fully proteated or deuterated at the N5 position, respectively. Then in the second mix, the solution from the first mix was reacted with 4 mM p-NBA. After mixing, the final concentration of the enzyme was 13 µM, the concentration of NADH or [4R-2H]NADH was 13 µM, and the concentration of p-NBA was 2 mM (vs. KM ≈0.27 mM). The reactions were monitored as the increase in absorbance at 454 nm.

Analyses were conducted by fitting kinetic data using exponential equations for growth and decay using the Marquardt algorithm in Program A, developed by C. J. Chiu, R. Chung, J. Diverno, and D. P. Ballou at the University of Michigan (Ann Arbor, MI) or with the Kinesyst 3 software provided with the stopped-flow spectrophotometer (TgK Scientific).

Solvent accessibility of the active site

Water access to the active site was assessed by comparing the rate of the oxidative half reaction of reduced NR (35 µM) equilibrated in H2O buffer with 9% (w/v) glycerol mixed with p-NBA (4 mM) equilibrated in the same buffer (oxidative rate constant = 11.5 ± 0.1 s−1, ●) vs. the case of p-NBA (4 mM) equilibrated in D2O buffer pD 7.50 (oxidative rate constant of 9.0 ± 0.1 s−1 , ○). Concentrations after mixing were 17.5 µM and 2 mM for NR and p-NBA, respectively. The cross symbols (+) show the result of mixing 35 µM reduced NR with 4 mM p-NBA both in D2O buffer pD 7.50 (oxidative rate constant of 6.1 ± 0.1 s−1 ) and the triangles (Δ) show the result of mixing reduced NR and p-NBA both equilibrated in H2O buffer without 9% glycerol. In all cases, only every 20th data point is shown for clarity, and the solid lines and dotted line are the curves resulting from fitting each trace.

Rate of solvent exchange of the N5-H of reduced flavin in NR

Reduced NR was produced by initial mixing of oxidized anaerobic 52 µM NR with 52 µM [4R-2H]NADH and then allowed to age for a range of aging time intervals before mixing with 4 mM p-NBA to measure the rate of the oxidative half reaction (13 µM NR and 2 mM p-NBA). Upon initial mixture the FMN of NR accepts deutero-hydride from [4R-2H]NADH and becomes reduced. Once reduced the [N5-2H]-FMN is subject to H/D exchange with excess H from the H2O solvent, yielding FMN that is no longer deuterated at N5. At the end of the age time the partially deuterated reduced NR reacts with p-NBA and the rate of flavin reoxidation was measured. Aging times of 0.01 to 50 s were compared. The observed oxidation rates were plotted as a function of the age time revealing faster reoxidation of NR in which more of the deuterium had exchanged for proteum. The data were fit with the equation for single exponential decay of the population of [N5-2H]-FMNred•NR with an oxidation rate of and production of proteated FMNred•NR with an oxidation rate of , where the rate of H/D exchange is . The best fit was produced by kH/D = 0.048 ± 0.001 s−1, and .

KIEs on Steady-State Kinetic Experiments

Steady-state kinetic measurements were monitored spectrophotometrically at 370 nm to measure oxidation of NADH or [4R-2H]NADH to NAD+ using the known extinction coefficient of NADH at pH 7.50; ε370 = 2.56 × 103 M−1cm−1 (Koder and Miller, 1998a) and a Vanan Cary 300 Bio UV-Visible Spectrophotometer (Agilent Technologies) at 25°C. For determination of the kinetic parameters, the reaction mixture contained 280 µM NADH or [4R-2H]NADH, 60 nM NR, and the concentration of p-NBA was varied (28, 55, 110, 220, 440, and 550 µM) in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer pH 7.50 with 9% (w/v) glycerol (H2O buffer) or pD 7.50 (D2O buffer). Initial velocity was plotted against the p-NBA concentrations used and the data were fit to the Michaelis-Menten equation.

Solvent deuterium kinetic isotope effect (SKIE)

Reactions were performed in (a) 50 mM H2O buffer with 9% (w/v) glycerol pH 7.50 at 25°C of (b) 50 mM D2O buffer pD 7.50 at 25°C. Plots of initial velocity versus p-NBA concentrations (0.028, 0.055, 0.11, 0.22, 0.44, 0.55 mM) at a fixed NADH concentration greater than 8 times the (280 µM NADH, black circles) or [4R-2H]NADH concentration (280 µM, red circles) showed hyperbolic dependence on p-NBA concentrations KmNADH = 35 µM(Koder and Miller, 1998a; Pitsawong et al., 2014)). Error bars depict the standard deviations of the rate values. Fits to the Michaelis-Menten model yielded kinetic parameters of of 0.28 ± 0.04 mM, and of 0.26 ± 0.03 mM with kcat values of Hkcat of 9.1 ± 0.4 s−1 and Dkcat of 6.3 ± 0.3 s−1 for reactions in H2O buffer with 9% (w/v) glycerol. In D2O buffer the kinetic parameters were found to be , and with kcat values of Hkcat = 6.8 ± 0.3 s−1 and Dkcat = 4.5 ± 0.2 s−1.

The deuterated reaction medium was prepared as follows. 99.9% D2O was used to make 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (D2O buffer) by dissolving potassium phosphate powder in 99.9% D2O and incubating overnight (~12 hours). Then the solution was evaporated to dryness at 60°C, 50 mmHg for 3 hours using a rotary evaporator. The entire process was repeated three times to obtain a buffer containing 99.9% D2O. The D2O buffer was adjusted to pD 7.50 (where pD = pH meter reading + 0.4 to correct for the acidity of the pH electrode itself (Glasoe and Long, 1960)) using sodium deuteroxide. Enzyme was exchanged into D2O buffer twice using Econo-Pac® 10DG chromatography columns (Bio-Rad Laboratories) pre-equilibrated with D2O buffer pD 7.50 and reduced by adding stoichiometric sodium dithionite in D2O in an anaerobic glovebox. p-NBA was dissolved in 75% ethanol-d6 and 25% D2O with gentle warming.

Model for proposed hydride transfers to and from flavin N5

Molecular models of NR active site H atoms. Reacting atoms are depicted as balls with the H of NAAD equivalent to the hydride of NADH in aqua, and the N5H of reduced flavin in mint green. Flavin is in yellow, NAAD is in purple, p-NBA is in pink with heteroatoms colored in CPK. We assume that the analog NAAD binds in the same way as the substrate NADH. The structures of p-NBA•NR, NAAD•NR and reduced NR (1KQD.pdb) were overlaid based on all backbone atoms using swissview (Guex and Peitsch, 1997). Only the reduced flavin is shown. H atoms were added in chimera and are shown for illustrative purposes only, without claim of precise positional accuracy. We note that p-NBA binds with ~XOO engaging the same interactions that engage the carboxyl of NAAD. Given the position of the NADH amide vs. the C4, placement of the nitro in the amide-binding position cannot optimize hydride transfer and we speculate that nitroreduction could be a fortuitous result of ~NOO mimicry of ~CONH2, in combination with the ease with which ~NOO is reduced. If the nitro group is to be better positioned in reduced NR, there must be conformational change upon flavin reduction.

Quantification and Statistical Analysis

Results of replicate experiments were tabulated in microsoft Excel which was used to calculate standard deviations. Measurements were made in triplicate at least (n≥3), as indicated in figure legends and the Method Details.

Data and Software Availability

Protein structures and data upon which they rest have been deposited to the protein data bank under the accession codes 5J8D.pdb (Coordinates and structure factors for NAAD•NR) and 5J8G.pdb (Coordinates and structure factors for p-NBA•NR).

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Nitroreductase holds promise for semisynthesis, prodrug activation and remediation.

Kinetic isotope effects establish the mode of substrate binding.

KIEs reveal hydride transfer to substrate in contrast with computational prediction.

Nitroreductase adapts an NADH-binding site to binding of nitroaromatics.

Acknowledgments

AFM and WP acknowledge invaluable discussions with D. Ballou and A. Kohen, and support from NSF I/UCRC grant 0969003 to the Center for Pharmaceutical Development. AFM recognizes WOCM for guidance, WP acknowledges the University of Kentucky for RCTF fellowship support. DR acknowledges support from N.I.H. grants NS38041 and GM110787 and N.S.F. grants MCB9904886. AFM and DR acknowledge support from N.S.F KY EPSCoR grant IIA-1355438.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author contributions

CH and DR solved the crystal structures, RLK prepared enzyme, WP performed kinetic measurements and analyses, WP and CH prepared manuscript drafts, AFM prepared the manuscript, WP, DR and AFM produced figures and tables, all authors read and commented on the manuscript.

References

- Adams PD, Afonine PV, Bunkoczi G, Chen VB, Davis IW, Echols N, Headd JJ, Hung L-W, Kapral GJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, et al. PHENIX: a comprehensive Python-based system for macromolecular structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2010;66:213–221. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909052925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bang SY, Kim JH, Lee PY, Bae K-H, Lee JS, Kim P-S, Lee DH, Myung PK, Park BC, Park SG. Confirmation of Frm2 as a novel nitroreductase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;423:638–641. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.05.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barna TM, Khan H, Bruce NC, Barsukov I, Scrutton NS, Moody PC. Crystal structure of pentaerythritol tetranitrate reductase: “Flipped” binding geometries for steroid substrates in different redox states of the enzyme. J Mol Biol. 2001;310:433–447. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barna TM, Messiha HL, Petosa C, Bruce NC, Scrutton NS, Moody PCE. Crystal structure of bacterial morphinone reductase and properties of the C191A mutant enzyme. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:30976–30983. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202846200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basran J, Harris RJ, Sutcliffe MJ, Scrutton NS. H-tunneling in the multiple H-transfers of the catalytic cyctle of morphinone reductase and in the reductive half-reaction of the homologous pentaerythritol tetranitrate reductase. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:43973–43982. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305983200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belasco JG, Albery WJ, Knowles JR. Double Isotope Fractionation - Test for Concertedness and for Transition-State Dominance. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1983;105:2475–2477. [Google Scholar]

- Berrisford JM, Sazanov LA. Structural basis for the mechanism of respiratory complex I. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:29773–29783. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.032144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birrell JA, Hirst J. Investigation of NADH binding, hydride transfer and NAD+ dissociation during NADH oxidation by mitochondrial complex I using modified nicotinamide nucleotides. Biochem. 2013;52:4048–4055. doi: 10.1021/bi3016873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brünger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, Delano WL, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Jiang JS, Kuszewski JN, Pannu NS, Reed RJ, et al. Crystallography and NMR system: A new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallographica D. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant C, Hubbard L, McElroy WD. Cloning, Nucleotide Sequence, and Expression of the Nitroreductase Gene from Enterobacter cloacae. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:4126–4130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christofferson A, Wilkie J. Mechanism of CB1954 reduction by Escherichia coli nitroreductase. Biochem Soc Trans. 2009;37(2):413–418. doi: 10.1042/BST0370413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLano WL. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. DeLano Scientific 2002 http://wwwpymolorg.

- Deng Z, Aliverti A, Zanetti G, Arakaki AK, Ottado J, Orellano EG, Calcaterra NB, Ceccarelli EA, Carrillo N, Karplus PA. A productive NADP+ binding mode of ferredoxin-NADP+ reductase revealed by protein engineering and crystallographic studies. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6:847–853. doi: 10.1038/12307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon DA, Lindner DL, Branchaud B, Lipscomb WN. Conformations and electronic structures of oxidized and reduced isoalloxazine. Biochemistry. 1979;18:5770–5775. doi: 10.1021/bi00593a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagan RL, Palfey BA. Flavin-Dependent Enzymes. In: Begley T, editor. Comprehensive Natural Products Chemistry II. Oxford, UK: Elsevier; 2010. pp. 37–114. [Google Scholar]

- Fraaije MW, Mattevi A. Flavoenzymes: diverse catalysts with recurrent features. TIBS. 2000;25:126–132. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01533-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gannavaram S, Gadda G. Relative Timing of Hydrogen and Proton Transfers in the Reaction of Flavin Oxidation Catalyzed by Choline Oxidase. Biochemistry. 2013;52:1221–1226. doi: 10.1021/bi3016235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gherasim C, Ruetz M, Li Z, Hudolin S, Banerjee R. Pathogenic mutations differentially affect the catalytic activities of the human B12-processing chaperone CblC and increase futile redox cycling. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:11393–11402. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.637132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasoe PK, Long FA. Use of glass electrodes to measure acidities in deuterium oxide. J Phys Chem. 1960;64:188–190. [Google Scholar]

- Grove JI, Lovering AL, Guise CP, Race PR, Wrighton CJ, White SA, Hyde EI, Searle PF. Generation of Escherichia coli nitroreductase mutants conferring improved cell sensitization to the prodrug CB1954. Cancer Res. 2003;63:5532–5537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guex N, Peitsch MC. SWISS-MODEL and the Swiss-PdbViewer: An environment for comparative protein modeling. Electrophoresis. 1997;18:2714–2723. doi: 10.1002/elps.1150181505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillén H, Curiel JA, Landete JM, Muñoz R, Herraiz T. Characterization of a nitroreductase with selective nitroreduction properties in the food and intestinal lactic acid bacterium Lactobacillus plantarum WCFSI. J Agric Food Chem. 2009;57 doi: 10.1021/jf9024135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haynes CA, Koder RL, Jr, Miller A-F, Rodgers DW. Structures of Nitroreductase in Three States: Effects of Inhibitor Binding and Reduction. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:11513–11520. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111334200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecht H-J, Erdmann H, Park HJ, Sprinzl M, Schmid RD. Crystal structure of NADH oxidase from Thermus thermophilus. Nat Struct Biol. 1995;2 doi: 10.1038/nsb1295-1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isayev O, Crespo-Hernandez CE, Gorb L, Hill FC, Leszczynski J. In silico structure-function analysis of E. cloacae nitroreductase. Proteins. 2012;80:2728–2741. doi: 10.1002/prot.24157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson E, Parkinson GN, Denny WA, Neidle S. Studies of the nitroreductase produg-activating system. Crystal structures of complexes with the inhibitor dicoumarol and dinitrobenzamide prodrugs and of the enzyme active form. J Med Chem. 2003;46:4009–4020. doi: 10.1021/jm030843b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleywegt GJ, Jones TA. Databases in protein crystallography. Acta Crystallographica. 1998;D54:1119–1131. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998007100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobori T, Sasaki H, Lee WC, Zenno S, Saigo K, Murphy MEP, Tanokura M. Structure and site-directed mutagenesis of a flavoprotein from Escherichia coli that reduces nitrocompounds. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:2816–2823. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002617200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koder RL, Haynes CA, Rodgers ME, Rodgers DW, Miller A-F. Flavin thermodynamics explain the oxygen insensitivity of enteric nitroreductases. Biochemistry. 2002;41:14197–14205. doi: 10.1021/bi025805t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koder RL, Jr, Miller A-F. Steady state kinetic mechanism, stereospecificity, substrate and inhibitor specificity of Enterobacter cloacae nitroreductase. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998a;1387:394–405. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(98)00151-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koder RL, Miller A-F. Overexpression, isotopic labeling and spectral characterization of Enterobacter cloacae nitroreductase. Protein Expression and Purification. 1998b;13:53–60. doi: 10.1006/prep.1997.0866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koike H, Sasaki H, Kobori T, Zenno S, Saigo K, Murphy MEP, Adman ET, Tanokura M. 1.8 Å crystal structure of the major NAD(P)H:FMN oxidoreductase of a bioluminescent bacterium, Vibrio fischeri: Overall structure, cofactor and substrate analog binding, and comparison with related flavoproteins. J Mol Biol. 1998;280:259–273. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovering AL, Hyde EI, Searle PF, White SA. The structure of Escherichia coli nitroreductase complexed with nicotinic acid: Three crystal forms at 1.7 Å, 108Å and 2.4 Å resolution. J Mol Biol. 2001;309:203–213. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massey V, Hemmerich P. Active site probes of flavoproteins. Biochem Soc Trans. 1980;8:246–257. doi: 10.1042/bst0080246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGaughey GB, Gagne M, Rappe AK. pi-Stacking interactions. Alive and well in proteins. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:15458–15463. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.25.15458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meah Y, Massey V. Old Yellow Enzyme: Stepwise reduction of nitro-olefins and catalysis of aci-nitro tautomerization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97:10733–10738. doi: 10.1073/pnas.190345597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesecar AD, Stoddard BL, Koshland DE. Orbital steering in the catalytic power of enzymes: small structural changes with large catalytic consequences. Science. 1997;277:202–206. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5323.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijvipakul S, Ballou DP, Chaiyen P. Reduction kinetics of a flavin oxidoreductase LuxG from Photobacterium leiognathi (TH1): half-sites reactivity. Biochem. 2010;49:9241–9248. doi: 10.1021/bi1009985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishino S, Nakata M. Intramolecular hydrogen atom tunneling in 2-chlorobenzoic acid studied by low-temperatre matrix-isolation infrared spectroscopy. J Phys Chem A. 2007;111:7041–7047. doi: 10.1021/jp0717600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods in Enzymology. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page CC, Moser CC, Chen X, Dutton PL. Natural engineering principles of electron tunnelling in biological oxidation-reduction. Nature. 1999;402:47–52. doi: 10.1038/46972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pai EF, Karplus PA, Schulz GE. Crystallographic analysis of the binding of NADPH, NADPH fragments, and NADPH analogues to glutathione reductase. Biochemistry. 1988;27:4465–4474. doi: 10.1021/bi00412a038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal D, Banerjee S, Cui J, Schwartz A, Ghosh SK, Samuelson J. Giardia, Entamoeba, and Trichomonas enzymes activate metronidazole (nitroreductase) and inactivate metronidazole (nitroimidazole reductase) Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:458–464. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00909-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson GN, Skelly JV, Neidle S. Crystal structure of FMN-dependent nitroreductase from Escherichia coli B: a prodrug-activating enzyme. J Med Chem. 2000;43:3624–3631. doi: 10.1021/jm000159m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, Ferrin TE. UCSF Chimera - a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitsawong W, Hoben JP, Miller A-F. Understanding the broad substrate repertoire of nitroreductase based on its simple mechanism. J Biochem Chem. 2014;289:15203–15214. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.547117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pudney CR, Hay S, Scrutton NS. Bipartite recognition and conformatinal sampling mechanisms for hydride transfer from nicotinamide coenzyme to FMN in pentaerythritol tetranitrate reductase. FEBS J. 2009;276:4780–4789. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Race PR, Lovering AL, Green RM, Ossor A, White SA, Searle PF, Wrighton CJ, Hyde EI. Structural and mechanistic studies of Escherichia coli nitroreductase with the antibiotic nitrofurazone: reversed binding orientations in different redox states of the enzyme. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:13256–13264. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409652200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Race PR, Lovering AL, White SA, Grove JI, Searle PF, Wrighton CW, Hyde EI. Kinetic and structural characterisation of Escherichia coli nitroreductase mutants showing improved efficacy for the prodrug substrate CB1954. J Mol Biol. 2007;368:481–492. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers DW. Practical Cryocrystallography. Methods in Enzymology. 1997;276:183–203. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76059-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roston D, Islam Z, Kohen A. Isotope effects as probes for enzyme catalyzed hydrogen-transfer reactions. Molecules. 2013;18:5543–5567. doi: 10.3390/molecules18055543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schopfer LM, Ludwig ML, Massey V. A working proposal for the role of the apoprotein in determining the redox potential of the flavin in flavoproteins: correlations between potentials and flavin pKs. In: Curti B, Ronchi S, Zanetti G, editors. Flavins and Flavoproteins 1990. Berlin: Walter de Güyter; 1991. pp. 399–404. [Google Scholar]

- Shen AL, Sem DS, Kasper CB. Mechanistic studies on the reductive half-reaction of NADPH-cytochrome P450 oxidoreductase. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:5391–5398. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.9.5391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner JJ, Lei B, Tu S-C, Krause KL. Flavin reductase P: structure of a dimeric enzyme that reduces flavin. Biochemistry. 1996;35:13531–13539. doi: 10.1021/bi961400v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner JJ, Tu S-C, Barbour LJ, Barnes CL, Krause KL. Unusual folded conformation of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide bound to flavin reductase P. Protein Sci. 1999;8:1725–1732. doi: 10.1110/ps.8.9.1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas SR, McTamney PM, Adler JM, LaRonde-LeBlanc N, Rokita SE. Crystal structure of iodotyrosine deiodinase, a novel flavoprotein responsible for iodide salvage in thyroid glands. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:19659–19667. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.013458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westheimer FH. The magnitude of the primary kinetic isotope effect for compounds of hydrogen and deuterium. Chem Rev. 1961;61:265–273. [Google Scholar]

- Williams EM, Little RF, Mowday AM, Rich MH, Chan-Hyams JVE, Copp JN, Smaill JB, Pattersion AV, Ackerley DF. Nitroreductase gene-directed enzyme prodrug therapy: insights and advances toward clinical utility. Biochem J. 2015;471:131–153. doi: 10.1042/BJ20150650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu T-YCMK, Kennedy KJ, Valton J, Anderson KS, Walker GC, Taga ME. Active site residues critical for flavin binding and 5,6-dimethylbenzimidazoe biosynthesis in the flavin destructase enzyme BluB. Prot Sci. 2012;21:839–849. doi: 10.1002/pro.2068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zenno S, Koike H, Tanokura M, Saigo K. Conversion of NfsB, a minor Escherichia coli nitroreductase, to a flavin reductase similar in biochemical properties to FRase I, the major flavin reductase in Vibrio fischeri, by a single amino acid substitution. J Bateriol. 1996;178:4731–4733. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.15.4731-4733.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P. Doctoral Thesis, Chemistry, University of Kentucky. 2007. Nitroreductase: evidence for a fluxional low-temperature state and its possible role in enzyme activity. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.