Abstract

Determining which patients with COPD may benefit from a nebulized long-acting beta2-agonist (LABA) is a challenge in current practice. In the absence of strong clinical guidelines addressing this issue, an expert panel convened to develop guiding principles for the use of nebulized LABA therapy in patients with COPD. This article summarizes these guiding principles and other practical issues discussed during a roundtable meeting.

Keywords: copd; copd,bronchodilator; long-acting beta2-agonists; maintenance therapy; LABA; nebulization

Introduction

Despite advances in medical therapy and the availability of clinical practice guidelines for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), the trajectory of the disease is unwavering when considering exacerbations, hospitalizations, and mortality.1,2 There are currently many unmet medical needs in the care of patients with COPD. Smoking continues to be a major contributor to the onset and progression of the disease,3 which is often underdiagnosed and undertreated.4-7 Furthermore, medication adherence is poor,8 device selection may not be thoroughly individualized to patient needs,9 physical and cognitive functions that enable patients to effectively self-manage decline with age,10-13 and there is a lack of disease modifying pharmacological / biological agents in COPD.14

Methods

A roundtable meeting was convened with the purpose of discussing the role of nebulized long-acting beta2-agonist (LABA) therapy in patients with COPD. Seven participants attended the live meeting and discussed the following agenda items: (1) Identification and prioritization of unmet needs of patients with COPD; (2) Discussion of prototypical patients who may benefit from nebulized LABA therapy; and (3) Derivation of guiding principles to help clinicians decide if nebulized LABA therapy is appropriate for their patients. Select literature was retrieved by keyword search in PubMed and summarized as evidence to support the unmet medical needs identified by the panel. Participants acknowledged that the body of evidence needed to make strong guidelines for the use of nebulized LABA therapy is limited. However, guiding principles for the use of nebulized LABA therapy could be derived from available clinical trial evidence, experience in practice, and clinical logic.

Results

Identification and Prioritization of Unmet Needs in COPD

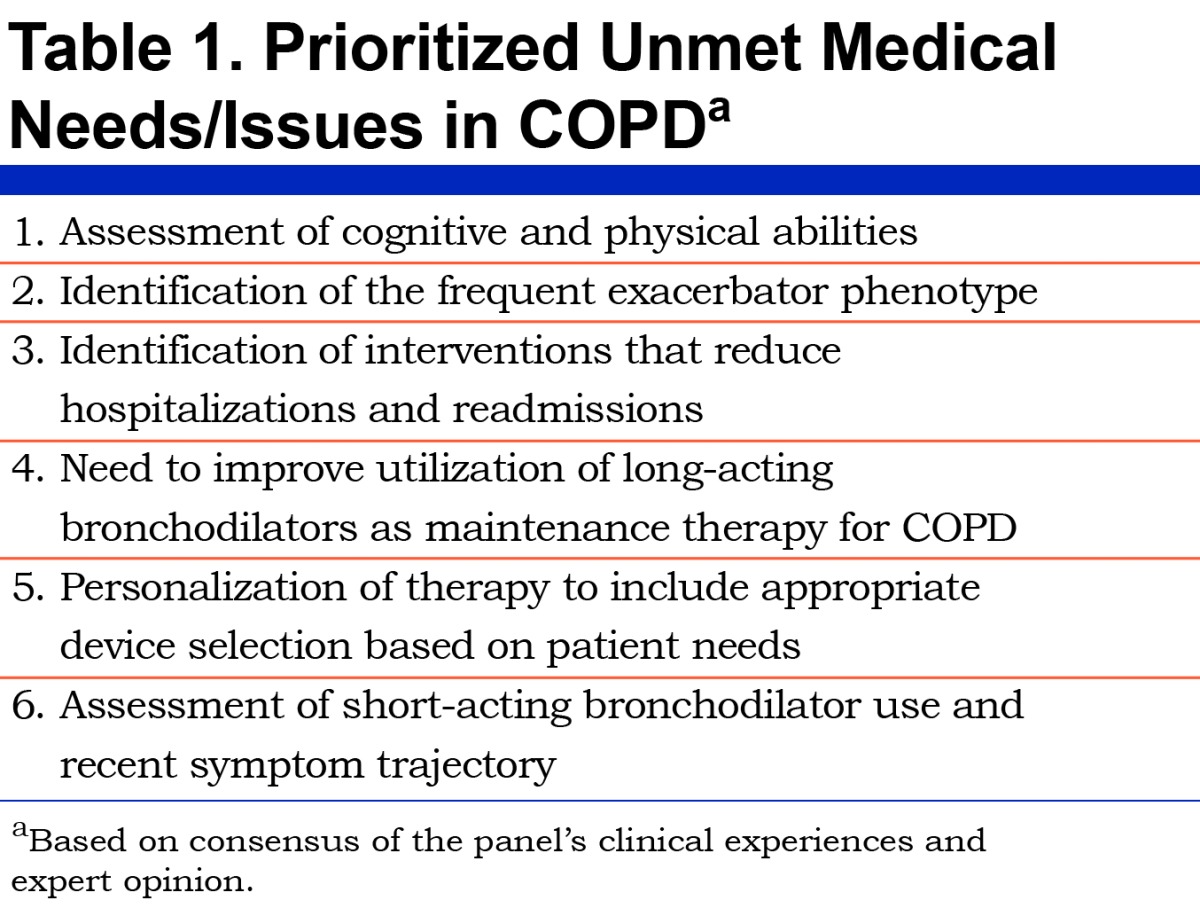

The panel identified and prioritized unmet needs and issues for patients with COPD, in particular those that may be addressed by nebulized LABA therapy (Table 1).

Panel Consensus: The following unmet needs/issues could be explored to further define the role of nebulized LABA therapy: (1) Assessment of cognitive and physical abilities in patients with COPD; (2) Identification of the frequent exacerbators; (3) Identification of interventions that reduce hospitalizations and readmissions; (4) Utilization of long-acting bronchodilators as maintenance therapy; (5) Personalization of therapy including appropriate device selection; and (6) Assessment of short-acting bronchodilator use and recent symptom trajectory.

Physical and Cognitive Decline in the COPD Population

Patients with COPD typically have several comorbidities that put a significant strain on their physical health and well-being.15 Some of these include degenerative bone disease, rheumatoid arthritis, skeletal muscle weakness, and other neuromuscular conditions; all of which may affect a patient’s ability to coordinate breath-actuated devices well. Furthermore, peak inspiratory flow rate (PIFR)in patients with COPD declines over time, which may prevent patients from generating sufficient inspiratory flow for dry powder inhalers (DPIs) with higher resistance.16-18 Evidence also suggests that hypoxemia in COPD is associated with cognitive impairment,10-12,19-23 and the percentage of COPD patients with cognitive impairment is high, ranging from 27% to 61% of patients.10-12,19,22,23 For example, in one study of 1202 patients (mean age 58), COPD was a risk factor for cognitive impairment (2.5 times more likely than a reference group without COPD to develop cognitive impairment).24 Another study of 1425 of patients (1055 with normal cognitive function at baseline; age range 74-83) showed that a diagnosis of COPD increased the risk of mild cognitive impairment by 83%.13 Furthermore, the Mayo Clinic Study of Aging showed that the risk of mild cognitive impairment worsens over time.25 In this study of 1927 patients with mild cognitive impairment (age 70-89 years), 288 (15%) had COPD. There was an overall two-fold risk of cognitive impairment in the patients with COPD in this study, and overall risk for any cognitive impairment increased from 1.60 (97% confidence interval [CI], 0.97 – 2.57) in patients with COPD duration of ≤5 years to 2.10 (95% CI, 1.38 – 3.14) in patients with COPD duration >5 years.25 Taken together, these data challenge the general belief in practice that cognitive impairment is a result of older age alone in the COPD population.

Panel Consensus: The panel recommends that clinicians conduct physical and cognitive assessments for all patients with COPD in their care, in conjunction with assessing clinical symptoms, to determine their ability to successfully coordinate handheld devices.

Burden of Frequent COPD Exacerbations and Hospital Readmissions

In recent years, the focus on patient outcomes in COPD has shifted from managing progressive dyspnea and disability to preventing exacerbations and hospitalizations. Exacerbations are associated with worsening disease, hospitalizations and readmissions, increased health care costs, impaired quality of life, and higher mortality.26 Because they occur unpredictably, exacerbations limit an individual’s ability to plan activities and social engagements, as well as to maintain stable employment. COPD exacerbations also cluster in time with the highest risk of recurrent exacerbation occurring within 8 weeks after an index exacerbation.27 Although exacerbations become more frequent as airflow obstruction worsens, they can occur in patients with mild-to-moderate airflow limitation (i.e., representing a much larger population of patients with COPD). Furthermore, longer symptom duration with each exacerbation is associated with a greater risk and shorter time to the next event,28 while increasing frequency of exacerbations accelerates decline in lung function and quality of life.29 This suggests that repeat events increase a patient’s susceptibility to future exacerbations and poor outcomes. Exacerbations are also associated with worsening hyperinflation,30 and reduced contractility of the diaphragm, which further reduces peak inspiratory flow (PIF).

Per the Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) therapeutic strategy, the goals of COPD care include minimizing symptoms, preventing disease progression, and reducing exacerbations.14,31 Exacerbations are common with 77% of patients experiencing at least one exacerbation annually.32 However, frequent exacerbations (≥2 per year), which increase the risk of hospitalization, are also common and occur in one-third to nearly a half of COPD patients with severe or very severe airflow limitation, and nearly a quarter of patients with moderate airflow obstruction.33 Also, among patients hospitalized for an exacerbation, 22.6% are readmitted to the hospital within 30 days of discharge.34 While reasons for readmission are varied, high rates of readmission to the hospital suggest a breakdown in continuity of care for patients following discharge.2,35 Current transitional care may fail to properly assess risk and monitor patients with persistent COPD symptoms, or unstable comorbidities in these patients that could lead to readmissions, after hospital discharge.34,36 It is also common that following an exacerbation, patients do not receive medications that are known to reduce the risk of future exacerbations (e.g. LABA therapy or LABA therapy plus an inhaled corticosteroid).37 Additionally, lack of appropriate assessments to determine the suitability of treatments for individual patients, as well as their abilities to administer those treatments, is common.

Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS) began tracking 30-day readmissions for COPD via their Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP) in 2015. Payments to hospitals for readmissions within 30 days are reduced to incentivize better care during a hospitalization. In some areas of medicine, the HRRP has had a positive effect.38 Evidence is inconclusive on predictive factors and interventions most likely to reduce readmissions for COPD,39 and efforts are underway to understand more about how to prevent these events.40

Panel Consensus: The panel suggested that addressing and identifying frequent exacerbators is a priority. In the absence of strong evidence detailing how clinicians can reduce or prevent hospital readmissions, a best-practice approach to the care of patients with COPD is warranted based on current recommendations.14,41 Additionally, recognizing risk factors for readmission can help predict which patients are at greatest risk of readmission within the first 30 days of discharge.27 The panel noted however that patients with COPD are frequently readmitted for unstable comorbidities, rather than COPD itself, and proper management of comorbidities is required to prevent non-COPD-related readmissions in patients with COPD.34,42 Across several studies, some of the medical, social, and system-based risk factors for readmissions include but are not limited to: older age, male gender, African American race, lower socioeconomic status, low health literacy, social isolation, low physical activity, prior hospitalization for COPD or emergency admission, longer length of hospital stay, lack of follow-up after discharge, heart failure, and no prescription for a short-acting bronchodilator, oral steroid, or antibiotic therapy on discharge.43-48 In the panel’s experience, social factors are as important as health or systems factors since they are, in most cases, less modifiable. Symptoms also worsen significantly before an exacerbation and patients should be encouraged to report any changes in their symptoms so that appropriate steps can be taken (i.e., change in therapy).49 Furthermore, since undertreatment of COPD after an exacerbation may intensify poor outcomes, the panel recommends that all patients be more closely monitored during the critical window following an exacerbation, and until the patient is recovered. It has been shown that mortality rate in patients admitted for an exacerbation in the year prior is nearly 25% so timely action is warranted for these patients.50

Utilization of Long-acting Bronchodilator Maintenance Therapy for COPD

In today’s practice, the use of long-acting bronchodilator maintenance therapy is low, and many times patients do not receive a long-acting bronchodilator as maintenance therapy even after the diagnosis is made.6,51 Underutilization of long-acting maintenance therapy is both a provider and a patient issue. In a retrospective analysis of about 50,000 U.S. managed care and Medicare patients with COPD, 66.3% of patients with commercial insurance and 70.9% of Medicare patients were not prescribed maintenance therapy for COPD.6 Importantly, patients categorized as high complexity were undertreated, which strongly suggests that practice is not aligned with current COPD guidelines. In another study, 36% of patients with at least one prior exacerbation were not receiving long-acting bronchodilator maintenance therapy.52

There are also issues at the patient level once medication has been prescribed. Among utilizers of handheld devices containing long-acting bronchodilators, adherence varied from 29% to 56% across the COPD disease spectrum for fixed-dose combinations of inhaled corticosteroids with LABA therapy, from 51% to 68% for long-acting anticholinergics, and from 25% to 62% for LABA monotherapy.8 If one considers improper technique with handheld inhalers as another component of poor adherence, then the frequency of poor adherence may be even higher.

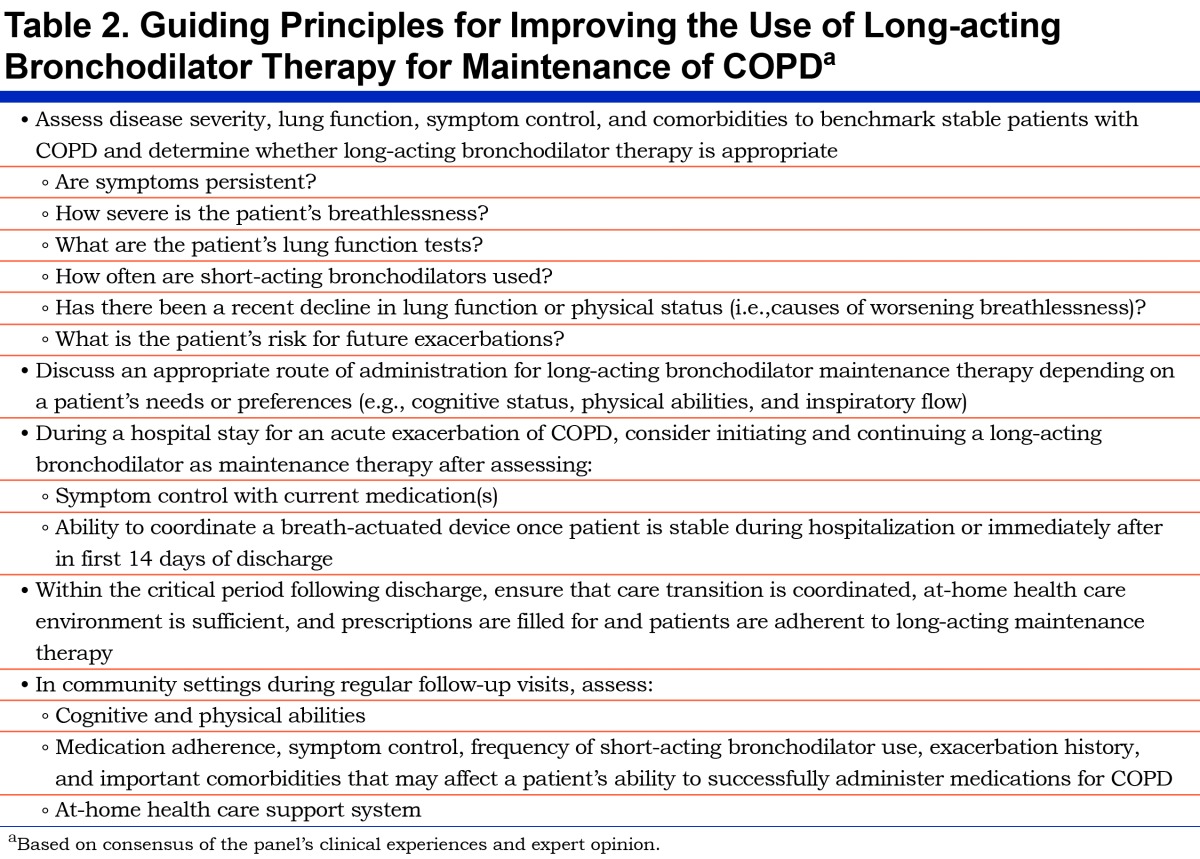

Panel Consensus: Poor patient outcomes such as COPD exacerbations, hospitalizations, and readmissions, as well as health care utilization costs, may be improved with the increased use of long-acting bronchodilator maintenance therapy. While the GOLD therapeutic strategy asserts that exacerbations can often be prevented,14 it may not provide enough guidance on care following hospitalization to prevent readmissions. A summary of guiding principles discussed by the panel for improving the use of long-acting maintenance therapy for COPD is shown in Table 2.

Selection of a Long-Acting Bronchodilator for the Maintenance of COPD

According to the GOLD therapeutic strategy, long-acting formulations of beta2-agonists and anticholinergics are preferred over short-acting agents for COPD maintenance treatment. It is common to see patients receive multiple treatments of a short-acting bronchodilator (by nebulizer or handheld device) as daily maintenance therapy for COPD, which goes against current recommendations.14,41 One study showed that patients reporting use of ≥1.5 short-acting beta2-agonists (SABA) doses per day are at increased risk of exacerbations.53 The initiation of LABA therapy versus SABA therapy alone for maintenance of COPD is associated with a 26% reduced risk of readmission within the first 6 months of a hospitalization for an exacerbation.54 Long-acting bronchodilators improve exercise endurance time and enhance the benefits gained from exercise training.55,56 They also improve health-related quality of life.57 Once a clinician decides to prescribe a long-acting bronchodilator for a patient with COPD, the next step is to determine which device may be appropriate for the patient—pressurized metered dose inhaler (pMDI), DPI, soft mist inhaler (SMI), or nebulizer.

Issues with Handheld Devices for COPD in Real-World Practice

In real-world practice, patients with COPD are highly variable in terms of education level, age, socioeconomic status, physical limitations, cognitive functioning, and chronic disease burden. Many of these variables contribute to medication errors made by patients with their handheld devices. Misuse of handheld devices is associated with decline in symptom control and risk of urgent care.58 In one study, over 94% of patients committed errors related to poor technique despite their affirmation of knowing how to use their devices.59 Specifically, poor inhaler technique and device misuse was associated with older age (P=0.008), lower education level (P=0.001), poor vision (P=0.004), and lack of instruction (P<0.001).58,60 Low health literacy is also a barrier to achieving desired health care outcomes. A recent study showed that teach-to-goal instruction for inhaler technique did not reduce inhaler misuse but was associated with fewer acute-care events 30 days after discharge.61 Although the teach-to-goal method has some benefit, the results are not universal and the improvements are transient. The rate at which handheld inhalers are misused in the elderly population is also a concern. In a 2015 study, 100% of elderly patients (N=24) made at least one error, and 83% made a critical error that impacted delivery of the drug.62 There are many inhaler choices, with their own specific inhalation techniques, often requiring multiple steps for accurate coordination of breath. The array of current choices can be confusing and overwhelming—not only for patients, but for clinicians as well.9

Errors with pMDIs are common and approximately 1 in 3 patients uses their inhaler incorrectly.63 Actuating a pMDI may be more difficult for patients with hand arthritis, memory issues, and poor coordination since there are many steps involved with using a pMDI correctly. Also, not using spacers or valved holding chambers properly can reduce the intended delivered dose.64,65 It has been demonstrated that suboptimal inspiratory force, as well as decline in cognitive function, are directly related to errors with DPIs.17 Adequate inspiratory force is required for patients to successfully inhale powder from a DPI into the lungs, and some patients with severe COPD cannot achieve an adequate inspiratory force against the resistance of their device.65,66 DPI resistance varies greatly across devices, with up to a 10-fold difference between devices (0.02– 0.20 cm H2O1/2 / L / min).67 Incorrect inhaler use can result in increased oropharyngeal deposition of inhaled powders and decreased lung deposition.67 In one study, critical errors were common with 88% of all patient observations with DPIs.62 Moreover, even correct DPI use results in relatively increased oropharyngeal deposition from inertial impaction due to the high inspiratory force required to deagglomerate the powder and generate fine particles, compared with the slower inspiratory flows used with other inhaler devices.

Panel Consensus: The panel recommends that clinicians take the time to identify risk factors for critical medication errors or medication nonadherence. Affirmation of patient knowledge is, in many cases, insufficient to guarantee appropriate use of available inhaler devices. Practical steps (such as the teach-back method) to ensure that patients are confident to self-administer their medication accurately is critical to future success. These items can be covered by clinicians once a patient is stable following treatment for an exacerbation, or immediately thereafter in follow up within the first 2 weeks of discharge. Many hospitalized COPD patients are unable to correctly use a pMDI or a DPI at the time of discharge, and even if taught do not retain instructions for proper device use once they return home. In these cases, a nebulizer may be a more appropriate choice for transitional care and home-bound or long-term care-bound patients, many of whom have the physical or cognitive impairments discussed here. The panel recommends clinicians consider initiating and bridging care with a nebulized LABA in selected patients in the hospital to cover the critical window following a recent hospitalization. There is no “one-size fits all” device for patients with COPD and only a thorough evaluation of patient abilities, physical and cognitive, as well as their home health care environment, will reveal potential barriers to achieving success with prescribed medications.

Nebulization of Long-acting Bronchodilators in Today’s Practice

Although evidence is limited to suggest that one delivery method for long-acting bronchodilator therapy is more advantageous than another for patients with COPD, we do know that incorrect use of handheld devices is linked to suboptimal outcomes.16,68 Patient preference for nebulization, low inspiratory force,17,18,69,70 and cognitive and physical impairments10,11,13,17,24,71 were agreed to be the most common reasons to consider nebulized LABA therapy for patients with COPD. Some evidence suggests that patients prefer nebulizing their medication,72 nebulization may help patients with low inspiratory force (i.e., following an exacerbation),73 and may help when cognitive or neuromuscular conditions are present.16 Currently, 2 LABAs are available for use in standard jet nebulizers, formoterol and arformoterol, and nebulized LAMAs are in development.74,75

About half of patients who remain breathless despite receiving bronchodilators delivered by pMDIs or DPIs derive benefits from home nebulizer use.76 It has been suggested that hospitalizations can be reduced when patients are given nebulizers (56% to 46%; P<0.01).77 Nebulized therapy has also been shown to have a positive impact on quality of life.78 More recent work with retrospective claims analyses has shown that initiating a nebulized LABA versus short-acting bronchodilator therapy alone significantly lowers 30-day hospital readmission rates by 31%.54 Furthermore, COPD patients with PIFR resistance of <60 L / min against the resistance of a DPI benefited from nebulized arformoterol compared with salmeterol given by DPI as measured by volume responses (forced expiratory volume in 1 second [FEV1], forced vital capacity [FVC], inspiratory capacity [IC]).73 The choice of nebulized LABA may also impact patient outcomes. In a recent study, the use of nebulized arformoterol tended to be associated with fewer exacerbations, lower inpatient costs, and lower COPD-related costs (primarily related to hospital readmissions) compared with nebulized formoterol.79

There are characteristics of nebulization that are both positive and negative. The primary advantage of nebulizing medications for COPD is the minimal coordination and inspiratory effort required by the patient. Compared with the coordination and special breathing techniques (full exhalation followed by full inhalation and several-second breathhold) required for pMDIs and DPIs, patients can sit comfortably and use tidal breathing during a nebulized treatment.9 A survey of patients with COPD showed that nebulized treatment helped them feel comfortable and more in charge of their own symptom control.80 In another study, patients and caregivers showed preference for nebulized therapy and stated that the benefits of nebulization therapy outweighed any difficulties or inconveniences.72,80 Patients also believed that their overall quality of life had improved since beginning nebulized treatments.72 Patients can use standard jet nebulizers for both short-acting and long-acting treatments, mucolytics and corticosteroids, and in some cases antibiotics.9 Practical considerations with nebulizers include the time required to nebulize, cleaning of nebulizer, equipment repairs, and non-portability of equipment.66,81 Education may be necessary to address some of these issues and newer, easier to use, more portable nebulizers may address others. As part of a shared decision-making process, clinicians can present patients with all available COPD medication and delivery options in order to make a decision that best meets the needs of an individual patient.

Guiding Principles for Nebulized LABA Therapy

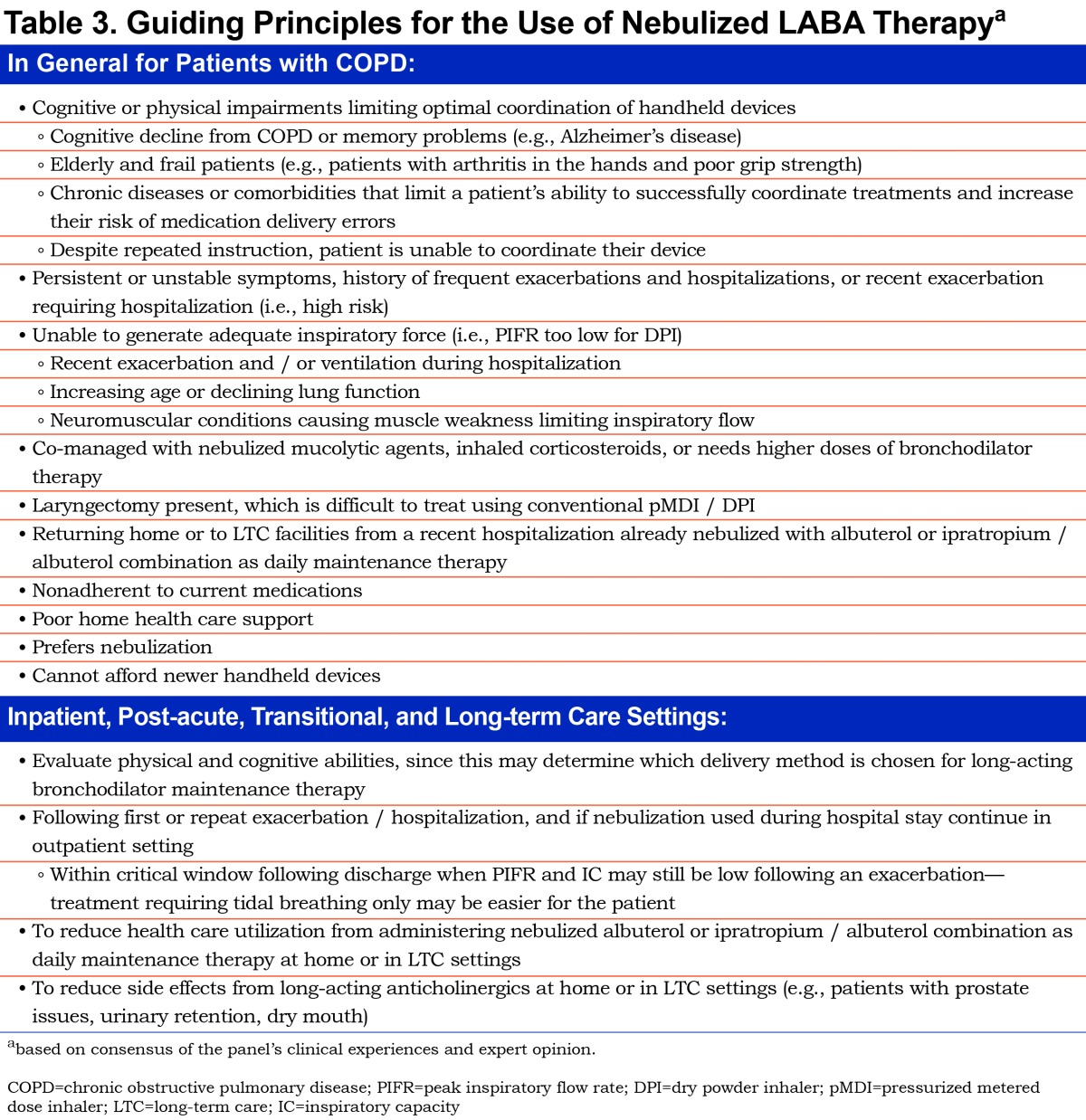

Although many patients can successfully use pMDIs or DPIs for maintenance of COPD, certain populations may benefit from medication delivery by nebulizer.66,72,82,83 Table 3 summarizes the panel’s guiding principles for the use of nebulized LABA therapy in patients with COPD.

Panel Consensus: The panel recommends taking the time to determine which inhalation device is the right device for the right patient. For example, patients who cannot coordinate or generate sufficient inspiratory force for breath-actuated handheld devices are candidates for nebulized therapy.9 The panel also suggested that nebulized LABA therapy should not be reserved for the most severe cases, although the most common scenarios for its use include: (1) the patient with physical and /or cognitive limitations who cannot use a handheld device successfully; (2) the severe COPD patient receiving oxygen therapy bound to home care; and (3) the patient who cannot afford a handheld inhaler. There are many other reasons why a nebulized LABA may be an appropriate choice, and the panel suggested that the most easily addressed opportunities to improve COPD patient outcomes may be to consider a nebulized LABA for: (1) the patient at home or residing in a long-term care center (LTC) facility who exhibits cognitive decline, physical limitations, or poor adherence to their medication; (2) the frequent exacerbator despite treatment with handheld inhalers; and (3) the patient with reduced inspiratory force from coexisting medical conditions, age, or following a recent exacerbation.

Additional Evidence Needed on the Use of Nebulized LABA Therapy in Practice

Although great strides have been made in the medical management of patients with COPD over the last several decades, many unanswered questions remain about appropriate assessment and long-term maintenance of COPD. The American Thoracic Society / European Respiratory Society have issued a thorough statement of ongoing research questions in COPD, which includes the comparative efficacy and outcomes of nebulized versus handheld long-acting bronchodilator therapy for COPD maintenance.84 In addition to comparative data between handheld devices and nebulized therapies, this panel identified a set of select research questions that may provide further clinical guidance on the use of nebulized LABA therapy in practice.

Panel Consensus: The following questions were identified by the panel for further study in this area of medicine:

What is the best method in practice to assess patient physical and cognitive abilities to use handheld devices adequately?

What specific patient criteria should prompt the initiation of a nebulized LABA as maintenance therapy in inpatient, outpatient, or long-term care settings?

Where does nebulized LABA therapy fit into the current treatment paradigm when considering combination therapy (e.g., triple therapy)?

Does initiating a nebulized LABA during and /or following hospitalization for an exacerbation reduce the risk of readmission?

Does continuing a nebulized LABA in transitional or post-acute care, at-home care, and long-term care settings reduce the risk of future exacerbations and hospitalizations?

When is it appropriate to switch a patient’s handheld inhaler to a nebulizer?

What is the pharmacoeconomic impact of using nebulized LABA therapy compared with short-acting bronchodilator therapy?

What is the pharmacoeconomic impact of using nebulized LABA therapy compared with handheld long-acting bronchodilators for maintenance of COPD?

Although limited evidence exists to address these questions, some of which were discussed here, additional data from prospective, randomized studies or long-term observational studies are needed to answer these questions thoroughly. Future studies may yield valuable data that can guide practice with nebulized LABA therapy.

Discussion

COPD represents a significant health care burden in today’s society. This burden is measured in terms of hospitalizations and readmissions for COPD exacerbations, total health care utilization, and patient mortality. Unfortunately, long-acting bronchodilator maintenance therapy is underutilized in current practice, which makes the reduction of COPD exacerbations, hospitalizations, and readmissions difficult. A panel of experts identified and prioritized several unmet medical needs in today’s practice, one of the most important of which was the need for long-acting bronchodilators as maintenance therapy for COPD. Furthermore, guiding principles specific to the use of nebulized LABA therapy in patients with COPD were discussed. Determining who may benefit from nebulized LABA therapy is currently left to best clinical judgment, and the recommendations discussed herein may help improve the identification of patients who are likely to receive the greatest benefit from a nebulized LABA. Another aspect of medication decision making is cost and although the wholesaler acquisition costs of nebulized LABAs may be higher than handheld LABAs,85 medications such as nebulized formoterol or arformoterol are often covered by the durable medical equipment benefit under Medicare Part B or by the prescription benefit under Medicare Part D. These agents are also covered by commercial insurance plans, although the out-of-pocket costs to patients may markedly vary depending on the plan. It is important to note that the misuse of handheld devices containing well-intended long-acting maintenance bronchodilators may increase health care system cost variables such as exacerbations, COPD hospitalizations, and readmissions.

Diligent assessment and consideration of specific patient characteristics (e.g., exacerbates frequently, uses SABA treatments as maintenance therapy, demonstrates cognitive and physical limitations) to determine a medication and delivery method aligned with individual patient needs is recommended in practice. Some of the data discussed by the panel and reviewed here suggest that objective and measurable clinical criteria, such as manual dexterity, cognitive ability, vision, and inspiratory force following an exacerbation can limit a patient’s ability to adequately coordinate a handheld device. In the absence of a specific clinical practice guideline, the panel recommends that health care providers take the time to evaluate their patients, especially following an exacerbation and before hospital discharge, to ensure that they not only receive a long-acting bronchodilator for their COPD symptoms but that their medication is delivered via a device matched to individual patient needs. This can be accomplished by developing an institution-based protocol to evaluate manual dexterity, cognitive ability, vision, and inspiratory force in patients with COPD. Although the panel recognizes that no validated tool currently exists to determine the suitability of nebulization for patients with COPD, using these criteria, in addition to medical logic, may be the next best step to achieving better outcomes in some patients. In some cases, the use of a nebulized LABA as maintenance therapy for COPD may be medically indicated. Furthermore, the recognition and recording of important clinical features may help other members of the health care team provide better care for these patients once they have returned to their medical home.

Collaboration across the spectrum of COPD patient care is necessary to change the trajectory of the disease and improve quality of life and long-term outcomes.

Abbreviations

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, COPD; long-acting beta2-agonist, LABA; peak inspiratory flow rate, PIFR; dry powder inhaler, DPI; confidence interval, CI; peak inspiratory flow, PIF; Global initiative for chronic Obstructive Lung Disease, GOLD; long-acting beta2-agonists, LABA; Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, CMS; Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program, HRRP; short-acting beta2-agonists, SABA; pressurized metered dose inhaler, pMDI; soft-mist inhaler, SMI; forced expiratory volume in 1 second, FEV1; forced vital capacity, FVC; inspiratory capacity, IC; long-term care, LTC

Funding Statement

Funding for the live roundtable meeting held on August 23, 2015 in Boston, Massachusetts and medical writing support was provided by Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, Inc. The sponsor had no role in the development or approval of this manuscript.

References

- 1. Ford ES. Trends in mortality from COPD among adults in the United States. Chest. 2015;148(4):962-970. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1378/chest.14-2311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ford ES. Hospital discharges, readmissions, and ED visits for COPD or bronchiectasis among US adults: findings from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample 2001-2012 and Nationwide Emergency Department Sample 2006-2011. Chest. 2015;147(4):989-998. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1378/chest.14-2146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Liu Y,Pleasants RA,Croft JB,et al. Smoking duration, respiratory symptoms, and COPD in adults aged ≥45 years with a smoking history. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:1409-1416. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S82259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Carlin BW. COPD and associated comorbidities: a review of current diagnosis and treatment. Postgrad Med. 2012;124(4):225-240. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3810/pgm.2012.07.2582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mapel DW,Dalal AA,Johnson P,Becker L,Hunter AG. A clinical study of COPD severity assessment by primary care physicians and their patients compared with spirometry. Am J Med. 2015;128(6):629-637. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.12.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Make B,Dutro MP,Paulose-Ram R,Marton JP,Mapel DW. Undertreatment of COPD: a retrospective analysis of US managed care and Medicare patients. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2012;7:1-9. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S27032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Leidy NK,Kim K,Bacci ED,et al. Identifying cases of undiagnosed, clinically significant COPD in primary care: qualitative insight from patients in the target population. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med. 2015;25:15024. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/npjpcrm.2015.24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ingebrigtsen TS,Marott JL,Nordestgaard BG,et al. Low use and adherence to maintenance medication in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the general population. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(1):51-59. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11606-014-3029-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dolovich MB,Ahrens RC,Hess DR,et al. Device selection and outcomes of aerosol therapy: Evidence-based guidelines: American College of Chest Physicians/American College of Asthma, Allergy, and Immunology. Chest. 2005;127(1):335-371. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1378/chest.127.1.335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dal Negro RW,Bonadiman L,Tognella S, Bricolo FP,Turco P. Extent and prevalence of cognitive dysfunction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic non-obstructive bronchitis, and in asymptomatic smokers, compared to normal reference values. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2014;9:675-683. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S63485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dodd JW. Lung disease as a determinant of cognitive decline and dementia. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2015;7(1):32. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s13195-015-0116-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sachdev PS,Anstey KJ,Parslow RA,et al. Pulmonary function, cognitive impairment and brain atrophy in a middle-aged community sample. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2006;21( 5.6 ):300-308. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000091438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Singh B,Mielke MM,Parsaik AK,et al. A prospective study of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and the risk for mild cognitive impairment. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71(5):581-588. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. GOLD Guidelines Committee; Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease: Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. GOLD website.http://www.goldcopd.org Published 2004 Updated 2016 Accessed November 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chatila WM,Thomashow BM,Minai OA,Criner GJ,Make BJ. Comorbidities in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5(4):549-555. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1513/pats.200709-148ET [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jarvis S,Ind PW,Shiner RJ. Inhaled therapy in elderly COPD patients; time for re-evaluation? . Age Ageing. 2007;36(2):213-218. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afl174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Quinet P,Young CA,Heritier F. The use of dry powder inhaler devices by elderly patients suffering from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2010;53(2):69-76. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rehab.2009.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mahler DA,Waterman LA,Gifford AH. Prevalence and COPD phenotype for a suboptimal peak inspiratory flow rate against the simulated resistance of the Diskus® dry powder inhaler . J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2013;26(3):174-179. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/jamp.2012.0987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Grant I,Heaton RK,McSweeny AJ,Adams KM,Timms RM. Neuropsychologic findings in hypoxemic chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch Intern Med. 1982;142(8):1470-1476. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dodd JW,Getov SV,Jones PW. Cognitive function in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2010;35(4):913-922. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00125109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ortapamuk H,Naldoken S. Brain perfusion abnormalities in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: comparison with cognitive impairment. Ann Nucl Med. 2006;20(2):99-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dodd JW,Chung AW,van den Broek MD,Barrick TR,Charlton RA,Jones PW. Brain structure and function in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a multimodal cranial magnetic resonance imaging study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186(3):240-245. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201202-0355OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Grant I,Prigatano GP,Heaton RK,McSweeny AJ,Wright EC,Adams KM. Progressive neuropsychologic impairment and hypoxemia. Relationship in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1987;44(11):999-1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Thakur N,Blanc PD,Julian LJ,et al. COPD and cognitive impairment: the role of hypoxemia and oxygen therapy. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2010;5:263-269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Singh B,Parsaik AK,Mielke MM,et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and association with mild cognitive impairment: the Mayo Clinic Study of Aging. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88(11):1222-1230. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.08.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Seemungal TA,Hurst JR,Wedzicha JA. Exacerbation rate, health status and mortality in COPD--a review of potential interventions. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2009;4:203-223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hurst JR,Donaldson GC,Quint JK,Goldring JJ,Baghai-Ravary R,Wedzicha JA. Temporal clustering of exacerbations in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179(5):369-374. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200807-1067OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Donaldson GC,Law M,Kowlessar B,et al. Impact of prolonged exacerbation recovery in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;192(8):943-950. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201412-2269OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Halpin DM,Decramer M,Celli B,Kesten S,Liu D,Tashkin DP. Exacerbation frequency and course of COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2012;7:653-661. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S34186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Stevenson NJ,Walker PP,Costello RW,Calverley PM. Lung mechanics and dyspnea during exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;172(12):1510-1516. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200504-595OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Cooper CB,Barjaktarevic I. A new algorithm for the management of COPD. Lancet Respir Med. 2015;3(4):266-268. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00091-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. O'Reilly JF,Williams AE,Holt K,Rice L. Defining COPD exacerbations: impact on estimation of incidence and burden in primary care. Prim Care Respir J. 2006;15(6):346-353. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pcrj.2006.08.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hurst JR,Vestbo J,Anzueto A,et al. Susceptibility to exacerbation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(12):1128-1138. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0909883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jencks SF,Williams MV,Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(14):1418-1428. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa0803563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Elixhauser A,Au DH,Podulka J. Readmissions for Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, 2008: Statistical Brief #121. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. Rockville(MD) 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hurst JR,Wedzicha JA. Management and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations: a state of the art review. BMC Med. 2009;7:40.doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-7-40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Melzer AC,Feemster LM,Uman JE,Ramenofsky DH,Au DH. Missing potential opportunities to reduce repeat COPD exacerbations. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(5):652-659. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11606-012-2276-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lu N,Huang KC,Johnson JA. Reducing excess readmissions: promising effect of hospital readmissions reduction program in US hospitals. Int J Qual Health Care. 2015. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzv090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Prieto-Centurion V,Markos MA,Ramey NI,et al. Interventions to reduce rehospitalizations after chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations. A systematic review. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11(3):417-424. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201308-254OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Krishnan JA,Gussin HA,Prieto-Centurion V,Sullivan JL,Zaidi F,Thomashow BM. Integrating COPD into patient-centered hospital readmissions reduction programs. Chronic Obstr Pulm Dis (Miami). 2015;2(1):70-80. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15326/jcopdf.2.1.2014.0148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Rennard S,Thomashow B,Crapo J,et al. Introducing the COPD Foundation Guide for Diagnosis and Management of COPD, recommendations of the COPD Foundation. COPD. 2013;10(3):378-389. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/15412555.2013.801309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Shah T,Churpek MM,Coca Perraillon M,Konetzka RT. Understanding why patients with COPD get readmitted: a large national study to delineate the Medicare population for the readmissions penalty expansion. Chest. 2015;147(5):1219-1226. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1378/chest.14-2181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sharma G,Kuo YF,Freeman JL,Zhang DD,Goodwin JS. Outpatient follow-up visit and 30-day emergency department visit and readmission in patients hospitalized for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(18):1664-1670. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2010.345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sharif R,Parekh TM,Pierson KS,Kuo YF,Sharma G. Predictors of early readmission among patients 40 to 64 years of age hospitalized for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11(5):685-694. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201310-358OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Baker CL,Zou KH,Su J. Risk assessment of readmissions following an initial COPD-related hospitalization. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2013;8:551-559. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.2147/copd.s51507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Niewoehner DE,Lokhnygina Y,Rice K,et al. Risk indexes for exacerbations and hospitalizations due to COPD. Chest. 2007;131(1):20-28. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1378/chest.06-1316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Chawla H,Bulathsinghala C,Tejada JP,Wakefield D,ZuWallack R. Physical activity as a predictor of thirty-day hospital readmission after a discharge for a clinical exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2014;11(8):1203-1209. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201405-198OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Yu TC,Zhou H,Suh K,Arcona S. Assessing the importance of predictors in unplanned hospital readmissions for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2015;7:37-51. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.2147/CEOR.S74181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Seemungal TA,Donaldson GC,Bhowmik A,Jeffries DJ,Wedzicha JA. Time course and recovery of exacerbations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161(5):1608-1613. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1164/ajrccm.161.5.9908022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Groenewegen KH,Schols AM,Wouters EF. Mortality and mortality-related factors after hospitalization for acute exacerbation of COPD. Chest. 2003;124(2):459-467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Barr RG,Celli BR,Mannino DM,et al. Comorbidities, patient knowledge, and disease management in a national sample of patients with COPD. Am J Med. 2009;122(4):348-355. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.09.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Diette GB,Dalal AA,D'Souza AO,Lunacsek OE,Nagar SP. Treatment patterns of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in employed adults in the United States. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:415-422. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.2147/COPD.S75034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Sharafkhaneh A,Altan AE,Colice GL,et al. A simple rule to identify patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease who may need treatment reevaluation. Respir Med. 2014;108(9):1310-1320. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2014.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Bollu V,Ejzykowicz F,Rajagopalan K,Karafilidis J,Hay JW. Risk of all-cause hospitalization in COPD patients initiating long-acting or short-acting beta agonist therapy. J Med Econ. 2013;16(8):1082-1088. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3111/13696998.2013.815625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Cooper CB,Celli BR,Jardim JR,et al. Treadmill endurance during 2-year treatment with tiotropium in patients with COPD: a randomized trial. Chest. 2013;144(2):490-497. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1378/chest.12-2613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Casaburi R,Kukafka D,Cooper CB,Witek TJ Jr.,Kesten SP. Improvement in exercise tolerance with the combination of tiotropium and pulmonary rehabilitation in patients with COPD. Chest. 2005;127(3):809-817. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1378/chest.127.3.809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Braido F,Baiardini I,Cazzola M,Brusselle G,Marugo F,Canonica GW. Long-acting bronchodilators improve health related quality of life in patients with COPD. Respir Med. 2013;107(10):1465-1480. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2013.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Melani AS,Bonavia M,Cilenti V,et al. Inhaler mishandling remains common in real life and is associated with reduced disease control. Respir Med. 2011;105(6):930-938. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2011.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Souza ML,Meneghini AC,Ferraz E,Vianna EO,Borges MC. Knowledge of and technique for using inhalation devices among asthma patients and COPD patients. J Bras Pneumol. 2009;35(9):824-831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Press VG,Arora VM,Shah LM,et al. Misuse of respiratory inhalers in hospitalized patients with asthma or COPD. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(6):635-642. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11606-010-1624-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Press VG,Arora VM,Trela KC,et al. Effectiveness of interventions to teach metered-dose and diskus inhaler techniques. A randomized trial. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13(6):816-824. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201509-603OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Vanderman AJ,Moss JM,Bailey JC,Melnyk SD,Brown JN. Inhaler misuse in an older adult population. Consult Pharm. 2015;30(2):92-100. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.4140/TCP.n.2015.92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Melani AS,Zanchetta D,Barbato N,et al. Inhalation technique and variables associated with misuse of conventional metered-dose inhalers and newer dry powder inhalers in experienced adults. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2004;93(5):439-446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Mitchell JP,Nagel MW. Valved holding chambers (VHCs) for use with pressurised metered-dose inhalers (pMDIs): a review of causes of inconsistent medication delivery. Prim Care Respir J. 2007;16(4):207-214. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3132/pcrj.2007.00034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Rau JL. The inhalation of drugs: advantages and problems. Respir Care. 2005;50(3):367-382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Dhand R,Dolovich M,Chipps B,Myers TR,Restrepo R,Farrar JR. The role of nebulized therapy in the management of COPD: evidence and recommendations. COPD. 2012;9(1):58-72. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/15412555.2011.630047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Dolovich MB,Dhand R. Aerosol drug delivery: developments in device design and clinical use. Lancet. 2011;377(9770):1032-1045. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60926-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Stevens N. Inhaler devices for asthma and COPD: choice and technique. Prof Nurse. 2003;18(11):641-645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Malmberg LP,Rytila P,Happonen P,Haahtela T. Inspiratory flows through dry powder inhaler in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: age and gender rather than severity matters. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2010;5:257-262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Janssens W,VandenBrande P,Hardeman E,et al. Inspiratory flow rates at different levels of resistance in elderly COPD patients. Eur Respir J. 2008;31(1):78-83. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00024807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Wheaton AG,Ford ES,Cunningham TJ,Croft JB. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hospital visits, and comorbidities: National Survey of Residential Care Facilities, 2010. J Aging Health. 2015;27(3):480-499. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0898264314552419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Sharafkhaneh A,Wolf RA,Goodnight S,Hanania NA,Make BJ,Tashkin DP. Perceptions and attitudes toward the use of nebulized therapy for COPD: patient and caregiver perspectives. COPD. 2013;10(4):482-492. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3109/15412555.2013.773302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Mahler DA,Waterman LA,Ward J,Gifford AH. Comparison of dry powder versus nebulized beta-agonist in patients with COPD who have suboptimal peak inspiratory flow rate. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2014;27(2):103-109. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1089/jamp.2013.1038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Leaker BR,Barnes PJ,Jones CR,Tutuncu A,Singh D. Efficacy and safety of nebulized glycopyrrolate for administration using a high efficiency nebulizer in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;79(3):492-500. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/bcp.12517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Pulido-Rios MT,McNamara A,Obedencio GP,et al. In vivo pharmacological characterization of TD-4208, a novel lung-selective inhaled muscarinic antagonist with sustained bronchoprotective effect in experimental animal models. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2013;346(2):241-250. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1124/jpet.113.203554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. O'Driscoll BR,Kay EA,Taylor RJ,Weatherby H,Chetty MC,Bernstein A. A long-term prospective assessment of home nebulizer treatment. Respir Med. 1992;86(4):317-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Godden DJ,Robertson A,Currie N,Legge JS,Friend JA,Douglas JG. Domiciliary nebuliser therapy--a valuable option in chronic asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease? . Scott Med J. 1998;43(2):48-51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Corden ZM,Bosley CM,Rees PJ,Cochrane GM. Home nebulized therapy for patients with COPD: patient compliance with treatment and its relation to quality of life. Chest. 1997;112(5):1278-1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Chen YJ,Makin C,Bollu VK,Navaie M,Celli BR. Exacerbations, health services utilization, and costs in commercially-insured COPD patients treated with nebulized long-acting β2-agonists . J Med Econ. 2016;19(1):11-20. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3111/13696998.2015.1079530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Barta SK,Crawford A,Roberts CM. Survey of patients' views of domiciliary nebuliser treatment for chronic lung disease. Respir Med. 2002;96(6):375-381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Alhaddad B,Smith FJ,Robertson T,Watman G,Taylor KM. Patients' practices and experiences of using nebuliser therapy in the management of COPD at home. BMJ Open Respir Res. 2015;2(1):e000076. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjresp-2014-000076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Boe J,Dennis JH,O'Driscoll BR,et al. European Respiratory Society Guidelines on the use of nebulizers. Eur Respir J. 2001;18(1):228-242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Sims MW. Aerosol therapy for obstructive lung diseases: device selection and practice management issues. Chest. 2011;140(3):781-788. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1378/chest.10-2068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Celli BR,Decramer M,Wedzicha JA,et al. An Official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society Statement: Research questions in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191(7):e4-e27. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201501-0044ST [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Med Lett Drugs; Olodaterol (Striverdi Respimat) for COPD. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2015;57(1459):1-3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]