Abstract

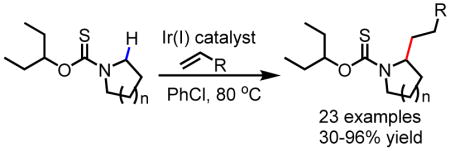

The development of new and practical 3-pentoxythiocarbonyl auxiliaries for Ir(I)-catalyzed C–H alkylation of azacycles is described. This method allows for the α-C–H alkylation of a variety of substituted pyrrolidines, piperidine and tetrahydroisoquinoline through alkylation with alkenes. While the practicality of these simiple carbamate type auxiliaries is underscored in the ease of installation and removal, the method’s novel reactivity is demonstrated in its ability to functionalize biologically relevant (L)-proline and (L)-trans-hydroxyproline, delivering unique 2,5-dialkylated amino acid analogues that are not accessible by other C–H functionalization methods.

Keywords: C–H activation, alkylation, cationic Ir(I), pentoxythiocarbonyl, pyrrolidine

Graphical Abstract

The development of a carbamate type 3-pentoxythiocarbonyl auxiliary for Ir(I)-catalyzed C–H alkylation of azacycles is described. This method allows for the α-C–H alkylation of a variety of substituted pyrrolidines, piperidine and tetrahydroisoquinoline through alkylation with alkenes. This method can also be extended to biologically relevant (L)-proline and (L)-trans-hydroxyproline delivering unique 2,5-dialkylated amino acid analogues.

Alkyl amines, as in acyclic amines or azacycles, are ubiquitous building blocks in biologically and medicinally relevant compounds[1]. Indeed, the myriad of α-functionalization methods is a testament of the importance of these fragments[2] with methods ranging from directed α-lithiation[3] to transition metal-mediated or photochemical synthesis of reactive intermediates.[4–6] The former generates a metalated intermediate that can react with a variety of electrophiles while the latter result in the formation carbocation[4], iminium[5] and α-amino radical[6] intermediates from pyrrolidines that can be intercepted by suitable coupling partners. Direct C–H arylation catalyzed by various transition metal have also been developed[7,8]. In the realm of direct C–H alkylation and related transformations, examples include transition metal-catalyzed C–H activation in the absence (Ta[9], Ti[10], Ru[11] catalysts) or presence of directing groups on nitrogen (Ru[12], Ir[13] and Rh[14] catalysts) had been reported. These strategies generate versatile metal hydride species that can react with either alkenes or a variety of coupling partners such as alkynes and bis(pinacolato)diboron to deliver alkylated, alkenylated and borylated products. Nevertheless, the utility of these C–H activation methods has been undermined by harsh reaction conditions as in the case of the former and lack of practical directing groups in the case of the latter. As such, development of practical methods for α-C–H alkylation of pyrrolidines and piperidines remains an unsolved problem. The lack of a simple directing group for this transformation is mainly due to the unfavorable metal insertion into the α-C–H bond.

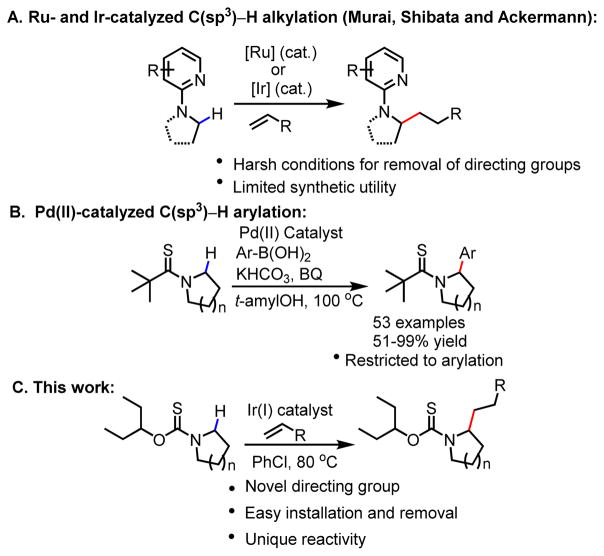

In 2011, Shibata and co-workers reported the first α-C(sp3)–H alkylation of aliphatic amines by cationic Ir(I) catalyst utilizing pyridine directing group[15], an important demonstration of Ir(I)-catalyzed C–H activation reactions (Scheme 1A). Despite achieving high yields and enantioselectivity, the alkylation reaction was only suitable for primary amines thereby limiting its synthetic utility. In 2014, Opatz and co-workers developed the benzoxazole directing group, which allowed for the first time, the α-C–H alkylation of cyclic secondary amines including piperidine and tetrahydroquinoline by cationic Ir(I) catalytic system[16] (Scheme 1A).

Scheme 1.

α-C–H Functionalizations of Azacycles

The main drawback of the benzoxazole directing group is the difficulty associated with its removal as evidenced in the strongly basic or reducing conditions employed to render its deprotection. Herein we report the development of practical alkoxythiocarbonyl directing groups to enable the Ir(I)-catalyzed α-C–H alkylation of pyrrolidines and other biologically important azacycles. This readily removable carbamate type directing group is potentially applicable to other transition metal catalysts.

Previously, our group disclosed the development of thioamides as competent directing groups for Pd(II)-catalyzed racemic and enanantioselective α-arylation of azacycles with aryl boronic acid coupling partners (Scheme 1B)[8]. While these thioamides were competent in directing α-C–H cleavage, deprotection was often problematic. Furthermore, utilization of these thioamide directing groups to achieve α-C–H alkylation has been unsuccessful thus far. To overcome the limitations associated with the thioamide auxiliaries, we were interested in developing a new sulfur-based directing group that exhibits comparable reactivity to the thioamide auxiliaries, yet can also be readily removed. We were encouraged by the work of Hodgson and co-workers in which they demonstrated the ability of tert-butoxy thiocarbonyl auxiliary to direct α-lithiation of azetidine in place of tert-butyl thioamide counterpart[17]. As such, we began our investigation examining the capability of the tert-butoxy thiocarbonyl directing group in directing α-C–H alkylation of pyrrolidine.

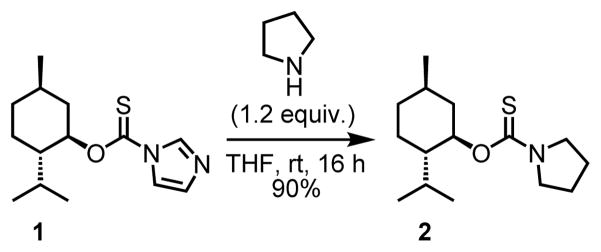

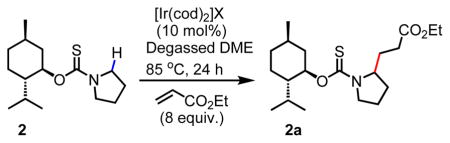

While the tert-butoxy thiocarbonyl directing group proved to be unstable to our reaction conditions, we were pleased to find that its more acid-stable variant, namely the menthoxythiocarbonyl directing group, which was synthesized in two steps from (−)-menthol via intermediate 1 (Scheme 2), gave a promising 45% yield of the desired hydroalkylated product in the presence of cationic [Ir(cod)2]BARF catalyst and ethyl acrylate coupling partner. The switch from tert-butoxythiocarbonyl to menthoxythiocarbonyl directing groups was based on two main considerations in mind. First, we hypothesized that the sterically imposing nature of the menthoxy group will enhance proximity-inducing effect[18] on the initial C–H activation step by Ir(I) catalyst. Second, the menthoxythiocarbonyl directing group can be synthesized in one step from (−)-menthol, a cheap and readily available chiral source with the potential for diastereoselective α-C–H alkylation. Encouraged by the initial hit with cationic [Ir(cod)2]BARF, we subsequently undertook screening for the most suitable non-coordinating counterions (BF4−, PF6−, OTf−), which were previously found to have a profound impact on catalyst’s reactivity[13]. To our delight, we found that triflate was the best counteranion, delivering the desired product in 80% yield (Table 1).

Scheme 2.

Installation of the menthoxythiocarbonyl directing group.

Table 1.

| ||

|---|---|---|

| Entry | Counteranion (X) | Yield 2a (%) |

| 1 | BARF | 45% |

| 2 | BF4− | 64% |

| 3 | PF6− | 74% |

| 4 | OTf− | 80% |

Conditions: 2 (0.1 mmol), ethyl acrylate (8.0 equiv), [Ir(cod)2]X (10 mol%), degassed 1,2-dimethoxyethane (DME), 80 °C, Ar, 24 h.

The yields were determined by 1H NMR using mesitylene as internal standard.

With this result in hand, we were initially interested in investigating the coupling partner scope. While initial results were promising with electronically neutral terminal alkenes, it immediately became apparent that the (−)-menthol derived chiral auxiliary only gave rise to slight diastereoselectivity (1.5:1 dr). Addition of chiral bisdentate phosphine ligands resulted in a reduction in efficiency without any improvement in diasetereoselectivity (see Supporting Information).

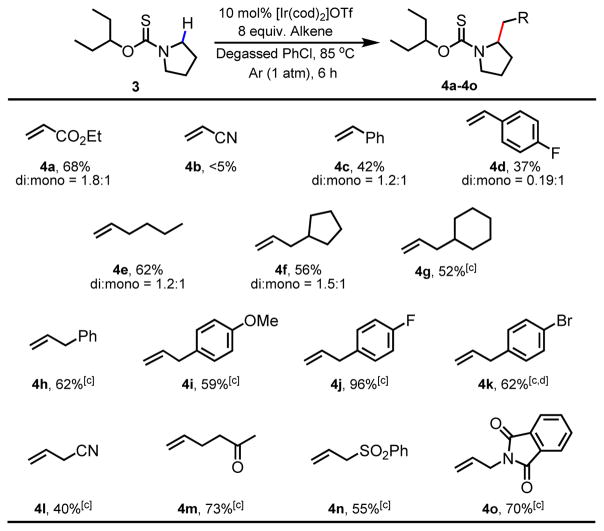

Furthermore, with the menthoxythiocarbonyl auxiliary, extension of the current α-C–H alkylation methodology to piperidine was not successful with only trace product being obtained. In light of these limitations, we decided to opt for a simpler, achiral alkoxythiocarbonyl directing group derived from 3-pentanol. We hypothesized that, due to decreased steric bulk, this directing group might be more accommodating to the binding of more conformationally flexible substrates such as piperidines to Ir(I) center. We were delighted to observe that the 3-pentoxythiocarbonyl auxiliary enabled α-C–H alkylation of pyrrolidine with ethyl acrylate in an encouraging 65% yield. Further tuning of reaction conditions revealed the superiority of chlorobenzene as solvent over 1,2-dimethoxyethane due to improved material balance. Furthermore, reduction of the reaction time was key to limiting desulfurization of the thiocarbonyl directing group, improving the yield of the desired alkylated product 4a to 68% yield (Table 2).

Table 2.

Conditions: 2 (0.1 mmol), alkene (8.0 equiv), [Ir(cod)2]OTf (10 mol%), degassed PhCl, 80 °C, Ar, 6 h.

Isolated yields are given here.

Only di-alkylated products (2,6-disubstituted) were obtained for these substrates,

Isolated yield given here was the yield of product obtained after removal of directing group.

With these optimized conditions in hand, the coupling partner scope was evaluated. A variety of terminal alkenes such as ethyl acrylate (4a), styrenes (4c and 4d), simple alkenes (4e–4g), allylbenzenes (4h–4k) are compatible coupling partners delivering the desired alkylated products in synthetically useful to excellent yields (Table 2). Interestingly, while ethyl acrylate is a competent coupling partner, acrylonitrile was not compatible with the current protocol. We were pleased to find that allyl nitrile, however, was a suitable coupling partner (4l) along with range of other alkenes with pendant functionalities such as 4-bromobenzene (4k), ketone (4m), sulfone (4n) and phthalimide (4o) delivering products that can be subjected to further synthetic manipulations. For a number of coupling partners, such as allylbenzenes (4h–4k) and alkenes with pendant functional groups (4l–4o), only di-alkylated products were observed. Reducing the loading of the alkene coupling partners or reaction time did not change the exclusive formation of di-alkylated products.

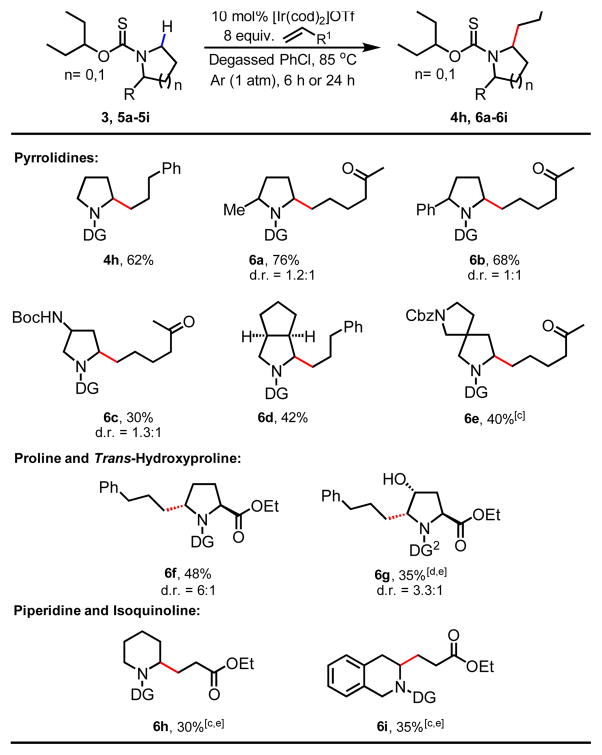

Subsequently, the substrate scope for Ir(I)-catalyzed C–H alkylation was evaluated. Various 2- and 3-substituted pyrrolidines (6a–6c) gave the desired alkylated products in synthetically useful yields (30–76%). We were pleased to observe that under our optimized reaction conditions, sterically incumbent and medicinally relevant bicyclic (6d) and spirocyclic pyrrolidines (6e) are suitable substrates. Furthermore, this method can also be extended to (L)-Proline (6f) and (L)-Hydroxyproline (6g), which feature frequently in investigational antiviral agents[19], delivering for the first time (L)-Proline and (L)-Hydroxyproline analogues with unique 2,5-substitution pattern with moderate diastereoselectivity. These unnatural amino acids will allow for investigation of new chemical space in peptide-based drug discovery which is currently undergoing a renaissance[20].

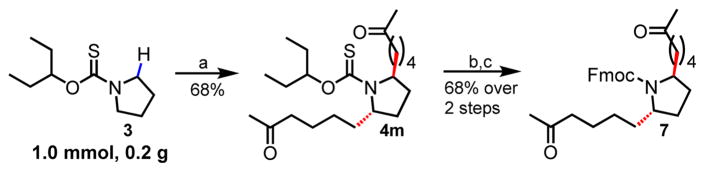

Finally, we were also able to demonstrate that this method could be used to alkylate piperidine (6h) and tetrahydroisoquinoline (6i) albeit in lower yields, in the presence of catalytic HBF4.Et2O as an additive. We also demonstrated the successful α-C–H alkylation of pyrrolidine 3 with allylacetone on large scale (1.0 mmol) delivering 4m with the same efficiency (68%, Scheme 3). The directing group could readily be removed by treatment with an aqueous solution of TFA (75% vol/vol) at 65 °C. The intermediate amine was immediately protected as an Fmoc-carbamate delivering 7 in 68% yield over two steps.

Scheme 3.

Large scale α-C–H alkylation of pyrrolidine and removal of 3-pentoxythiocarbonyl directing group. Reaction conditions: a. 3 (1.0 mmol), [Ir(cod)2]OTf (10 mol%), allylacetone (8 equiv.), degassed PhCl, Ar (1 atm), 85 °C, 6 h, 68%; b. 75% TFA in H2O, 65 °C, 2 h; c. Fmoc-OSu (2 equiv.), Dioxane: saturated aqueous NaHCO3 solution (1:1 v/v), 16 h, rt, 68% over 2 steps.

In conclusion, we have developed a novel and practical 3-pentoxythiocarbonyl directing group that allows for the α-C–H alkylation of a range of pyrrolidines, piperidine and tetrahydroisoquinoline. The synthetic utility of this simple carbamate derived directing group was further demonstrated in the α-C–H alkylation of important medicinally relevant motifs such as (L)-Proline and (L)-Hydroxyproline delivering, for the first time, unique 2,5-di-alkylated proline analogues. Future efforts in our laboratories will focus on the development of enantioselective α-C–H alkylation utilizing the current 3-penthoxythiocarbonyl directing group in the presence of chiral catalysts.

Experimental Section

General procedure for C–H alkylation

A 2-dram vial was charged with substrate 3 (20.2 mg, 0.1 mmol) and the vial was evacuated by passing through alternative cycles of vacuum/Argon. Degassed PhCl (0.5 mL) was then added to the above vial. In a separate 2-dram vial, under an Argon atmosphere (glovebox), [Ir(cod)2]OTf (5.7 mg, 0.01 mmol) was added followed by a solution of substrate 3 in degassed PhCl (0.5 mL). Subsequently, alkene (0.8 mmol) was added to the above reaction mixture and the reaction was allowed to stir at 85 °C, under an Argon atmosphere, for 6 or 24 h. Upon completion, the reaction was filtered over Celite® and the filter cake was thoroughly washed with EtOAc: MeOH (9:1 v/v). Solvent was removed in vacuo to give a crude residue that was purified by preparative TLC. NB: addition of degassed PhCl and alkene was performed outside of glovebox.

Supplementary Material

Table 3.

Conditions: 2 (0.1 mmol), alkene (8.0 equiv), [Ir(cod)2]OTf (10 mol%), degassed PhCl, 80 °C, Ar, 6 h.

Isolated yields are given here.

HBF4.Et2O (10 mol%) was used as an additive.

Menthoxythiocarbonyl directing group was used.

Reaction was run for 24 h.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge The Scripps Research Institute and the NIH (NIGMS, 2R01GM084019) for financial support. We thank the University of Sydney (postdoctoral fellowship to A. T. Tran), Dr. Lara Malins for assistance with preparative HPLC purification and Mr. Ruyi Zhu for obtaining HRMS data.

Footnotes

Supporting information for this article is available on the WWW under http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/anie.201xxxxxx.

References

- 1.Vitaku E, Smith DT, Njardarson JT. J Med Chem. 2014;57:10257. doi: 10.1021/jm501100b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.a Campos KR. Chem Soc Rev. 2007;36:1069. doi: 10.1039/b607547a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Mitchell EA, Peschiulli A, Lefevre N, Meerpoel L, Maes BUW. Chem -Eur J. 2012;18:10092. doi: 10.1002/chem.201201539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Maes J, Maes BUW. In: Advances in Heterocyclic Chemistry. Eric FVS, Christopher AR, editors. Vol. 120. Academic Press; 2016. p. 137. [Google Scholar]

- 3.a Meyers AI, Edwards PD, Rieker WF, Bailey TR. J Am Chem Soc. 1984;106:3270. [Google Scholar]; b Cordier CJ, Lundgren RJ, Fu GC. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:10946. doi: 10.1021/ja4054114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Liniger M, Estermann K, Altmann KH. J Org Chem. 2013;78:11066. doi: 10.1021/jo4017343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.a Asami R, Fuchigami T, Atobe M. Org Biomol Chem. 2008;6:1938–1943. doi: 10.1039/b802961j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Honzawa S, Uchida M, Sugihara T. Heterocycles. 2014;88:975. [Google Scholar]

- 5.a Suga S, Okajima M, Fujiwara K, Yoshida J-i. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:7941. doi: 10.1021/ja015823i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Murahashi SI, Komiya N, Terai H, Nakae T. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:15312. doi: 10.1021/ja0390303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Wei C, Li CJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:5638. doi: 10.1021/ja026007t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Wei C, Mague JT, Li CJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:5749. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307150101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Kumaraswamy G, Murthy AN, Pitchaiah A. J Org Chem. 2010;75:3916. doi: 10.1021/jo1005813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.a Booth SE, Benneche T, Undheim K. Tetrahedron. 1995;51:3665. [Google Scholar]; b Bertrand S, Glapski C, Hoffmann N, Pete JP. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999;40:3169. [Google Scholar]; c Yoshikai N, Mieczkowski A, Matsumoto A, Ilies L, Nakamura E. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:5568. doi: 10.1021/ja100651t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Noble A, MacMillan DWC. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:11602. doi: 10.1021/ja506094d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Johnston CP, Smith RT, Allmendinger S, MacMillan DWC. Nature. 2016;536:322. doi: 10.1038/nature19056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Qin T, Cornella J, Li C, Malins LR, Edwards JT, Kawamura S, Maxwell BD, Eastgate MD, Baran PS. Science. 2016;352:801. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf6123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Xie J, Yu J, Rudolph M, Rominger F, Hashmi ASK. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2016;55:9416. doi: 10.1002/anie.201602347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Joe CL, Doyle AG. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2016;55:4040. doi: 10.1002/anie.201511438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.a Pastine SJ, Gribkov DV, Sames D. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:14220. doi: 10.1021/ja064481j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Prokopcova, Bergman SD, Aelvoet K, Smout V, Herrebout W, Van der Veken B, Meerpoel L, Maes BUW. Chem -Eur J. 2010;16:13063. doi: 10.1002/chem.201001887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Peschiulli A, Smout V, Storr TE, Mitchell EA, Elias Z, Herrebout W, Berthelot D, Meerpoel L, Maes BUW. Chem -Eur J. 2013;19:10378. doi: 10.1002/chem.201204438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Dastbaravardeh N, Schnürch M, Mihovilovic MD. Org Lett. 2012;14:1930. doi: 10.1021/ol300627p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Kumar NYP, Jeyachandran R, Ackermann L. J Org Chem. 2013;78:4145. doi: 10.1021/jo400658d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.a Spangler JE, Kobayashi Y, Verma P, Wang DH, Yu JQ. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:11876. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b06740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Jain P, Verma P, Xia G, Yu JQ. Nat Chem. 2017;9:140. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.a Herzon SB, Hartwig JF. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:6690. doi: 10.1021/ja0718366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Herzon SB, Hartwig JF. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:14940. doi: 10.1021/ja806367e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Eisenberger P, Ayinla RO, Lauzon JMP, Schafer LL. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2009;48:8361–8365. doi: 10.1002/anie.200903656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Garcia P, Lau YY, Perry MR, Schafer LL. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2013;52:9144. doi: 10.1002/anie.201304153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Chong E, Brandt JW, Schafer LL. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:10898. doi: 10.1021/ja506187m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kubiak R, Prochnow I, Doye S. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2009;48:1153. doi: 10.1002/anie.200805169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jovel I, Prateeptongkum S, Jackstell R, Vogl N, Weckbecker C, Beller M. Chem Commun. 2010;46:1956. doi: 10.1039/b924674f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.a Chatani N, Asaumi T, Yorimitsu S, Ikeda T, Kakiuchi F, Murai S. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:10935. doi: 10.1021/ja011540e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Schinkel M, Wang L, Bielefeld K, Ackermann L. Org Lett. 2014;16:1876. doi: 10.1021/ol500300w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tsuchikama K, Kasagawa M, Endo K, Shibata T. Org Lett. 2009;11:1821. doi: 10.1021/ol900404r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kawamorita S, Miyazaki T, Iwai T, Ohmiya H, Sawamura M. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:12924. doi: 10.1021/ja305694r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.a Pan S, Endo K, Shibata T. Org Lett. 2011;13:4692–4695. doi: 10.1021/ol201907w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Pan S, Matsuo Y, Endo K, Shibata T. Tetrahedron. 2012;68:9009. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lahm G, Opatz T. Org Lett. 2014;16:4201–4203. doi: 10.1021/ol501935d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.a Hodgson DM, Kloesges J. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2010;49:2900. doi: 10.1002/anie.201000058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Hodgson DM, Mortimer CL, McKenna JM. Org Lett. 2015;17:330. doi: 10.1021/ol503441d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beak P, Meyers AI. Acc Chem Res. 1986;19:356. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stevenazzi A, Marchini M, Sandrone G, Vergani B, Lattanzio M. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2014;24:5349. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2014.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fosgerau K, Hoffmann T. Drug Disc Today. 2015;20:122–128. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.