Abstract

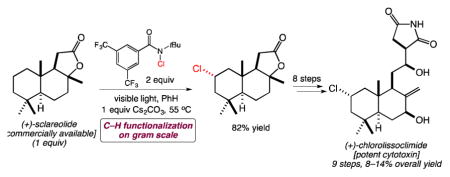

Methods for the practical, intermolecular functionalization of aliphatic C–H bonds remain a paramount goal of organic synthesis. Free radical alkane chlorination is an important industrial process for the production of small molecule chloroalkanes from simple hydrocarbons, yet applications to fine chemical synthesis are rare. Herein, we report a site-selective chlorination of aliphatic C–H bonds using readily available N-chloroamides, and apply this transformation to a synthesis of chlorolissoclimide, a potently cytotoxic labdane diterpenoid. These reactions deliver alkyl chlorides in useful chemical yields with substrate as the limiting reagent. Notably, this approach tolerates substrate unsaturation that poses major challenges in chemoselective, aliphatic C–H functionalization. The sterically- and electronically-dictated site selectivities of the C–H chlorination are among the most selective alkane functionalizations known, providing a unique tool for chemical synthesis. The short synthesis of chlorolissoclimide features a high yielding, gram-scale radical C–H chlorination of sclareolide and a three-step/two-pot process for the introduction of the β-hydroxysuccinimide that is salient to all the lissoclimides and haterumaimides. Preliminary assays indicate that chlorolissoclimide and analogues are moderately active against aggressive melanoma and prostate cancer cell lines.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The free radical chlorination of unactivated alkanes with elemental chlorine is industrially important for the preparation of a number of chlorinated small molecules.1 The vast majority of these applications involve hydrocarbons with only one type of C–H bond, however. This is a consequence of the promiscuity of chlorine free radical, which leads to poor site selectivities in free radical alkane chlorinations and a proclivity for undesired polyhalogenations with more complex substrates. 2 This contrasts the controlled, predictable nature of alkane brominations, which are often highly regioselective for the weakest C–H bond present, such as tertiary, allylic or benzylic positions.3 Alkyl chlorides are highly useful synthetic building blocks, and >2000 chlorine-containing natural products have been identified to date.4 New methods for practical, selective aliphatic C–H chlorinations hold significant potential for streamlining the synthesis and derivatization of broad classes of synthetically and medicinally valuable small molecules.5

Alternative strategies for intermolecular aliphatic C–H chlorination have been developed that avoid the intermediacy of chlorine free radical, and offer improved site selectivities. For example, prior studies have demonstrated that nitrogencentered radicals derived from N-chloroamines can facilitate site-selective C–H chlorination, but these reactions required the use of strong acid as solvent, and are therefore impractical for complex synthesis.6 Recent studies have indicated the potential for biomimetic alkane chlorination using manganese porphyrin catalysts,7 but the intermediacy of reactive high valent metal-oxo species presents challenges in chemoselectivity with functionalized substrates.

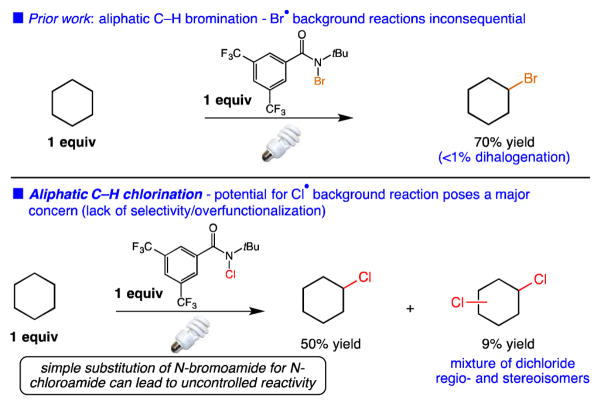

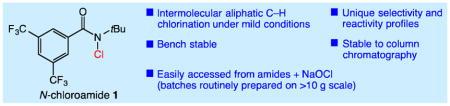

We have previously reported the development of a set of easily accessed, bench stable N-bromoamides for the site-selective, intermolecular bromination of unactivated C–H bonds.8 These reactions used substrate as limiting reagent and delivered products using elements of both steric and electronic control. Herein, we have extended our approach to C–H chlorination using household lamp irradiation and N-chloroamides that are trivially prepared from amides and NaOCl. Our studies have shown that in contrast to C–H bromination with N-bromoamides, background reactions (e.g., Cl• reactivity) were significant in these studies (Figure 1). We have developed a practical protocol that overcomes this unselective background reactivity. We have also demonstrated the unique site and chemoselectivities of our aliphatic C–H chlorination, including applications to substrates containing more reactive tertiary, allylic, or benzylic C–H bonds. Unsaturated substrates are rare in studies of intermolecular aliphatic C–H functionalization, and is a notable aspect of this approach.9 Finally, we demonstrate the practical utility of our chlorination method in the short synthesis of the potent cytotoxin chlorolissoclimide and analogues, wherein gram-scale, highly selective monochlorination of sclareolide plays a pivotal role.

Figure 1.

Aliphatic C–H chlorination using N-chloroamides introduces the possibility of unselective background reactions, potentially lowering reaction site selectivity and chemoselectivity.

DEVELOPMENT OF THE ALIPHATIC C–H CHLORINATION

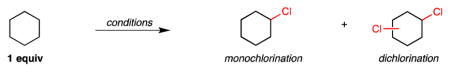

Our studies commenced with the C–H chlorination of 1 equiv of cyclohexane (Table 1). As with aliphatic C–H bromination, methods for intermolecular aliphatic C–H chlorination using substrate as limiting reagent are extremely rare.7 A survey of classical C–H chlorinations demonstrated either low reactivity with N-chlorosuccinimide (entry 1, 5 equiv substrate), or uncontrolled reactivity with SO2Cl2 (entry 2). Chlorination using a biomimetic Mn-porphyrin system provided good conversion, however a significant amount of dichlorination product was formed (entry 3).7a The cyclohexane chlorination using the conditions previously reported for alkane bromination with N-chloroamide 1 (irradiation using 23W compact fluorescent bulbs) also provided moderate conversion and similar mono- versus dichlorination selectivity (entry 4). An alternative approach using radical initiation with benzoyl peroxide (BPO) was also suboptimal (entry 5).

Table 1.

Chlorinations of Cyclohexane with Substrate as Limiting Reagent.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| entry | reagents | % mono-chloride | % dichloride | % conversion |

| 1 | NCS, AIBN, 60 °C (5 equiv cyclohexane) | 71.1 | 28.9 | N/A |

| 2 | SO2Cl2, BPO, 85 °C | 71.1 | 28.9 | 85.7 |

| 3 | Mn(TPP)Cl/NaOCl | 89.9 | 10.1 | 62.3 |

| 4 | chloroamide 1, hv, rt | 85.1 | 14.9 | 58.6 |

| 5 | chloroamide 1, BPO, 65 °C | 86.0 | 14.0 | 46.1 |

| 6 | chloroamide 1, hv, 1 equiv Cs2CO3, rt | 90.5 | 9.5 | 60.8 |

| 7 | chloroamide 1, hv, 1 equiv Cs2CO3, 55 °C | 96.9 | 3.1 | 71.6 |

Reactions were performed with [substrate]0 = 1.0 M in PhH under Ar atmosphere with 1 equiv of substrate and N-chloroamide, unless otherwise noted. Yields and selectivity determined by GC analysis.

At this stage, we hypothesized that the promiscuity of chlorine radical could be adversely affecting our reaction selectivity. This idea is supported by the prior studies of Greene, who demonstrated that the chain carrying species of aliphatic C–H chlorinations with N-chloroamides can vary widely depending upon the exact reaction conditions.10 Specifically, we questioned whether trace acid was reacting with reagent 1 to deliver amide and Cl2. Adding 1 equiv of Cs2CO3 improved the selectivity for monochlorination (90.5%), supporting this hypothesis (entry 6). Increasing the reaction temperature to 55 °C further improved the reaction selectivity to 96.9% monochlorination, potentially owing to greater solubility of the base.

After arriving at our optimized conditions for the C–H chlorination, we next determined the deuterium kinetic isotope effect by the competition reaction between cyclohexane and d12-cyclohexane using reagent 1. The observed primary kinetic isotope effect was kH/kD = 4.9 under these conditions, which is consistent with irreversible hydrogen atom abstraction. For the sake of comparison, the bromination of cyclohexane under these conditions with the N-bromo derivative of 1 also resulted in a kH/kD = 4.9, consistent with an amidyl radical in both C–H abstractions.

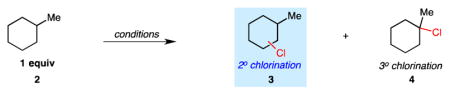

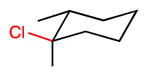

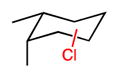

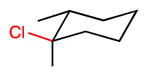

Our studies continued with an investigation of the sterically dictated site selectivities of our C–H chlorination using methylcyclohexane as substrate (Table 2). Prior to conducting reactions with N-chloroamide 1, we surveyed the secondary (desired) versus tertiary (undesired) selectivity using known chlorination methods. Classical methods involving either N-chlorosuccinimide or sulfuryl chloride provided modest selectivities (ksecondary/ktertiary, ks/kt, = 0.31 and 0.28, respectively) after correcting for the number of tertiary (one) and secondary (ten) sites available (entries 1 and 2).11 Chlorination catalyzed by Mn(TPP)Cl provided similar selectivity (ks/kt = 0.38, entry 3).7 As observed in the reactions of cyclohexane in Table 1, chlorination using N-chloroamide 1 in the absence of base provides suboptimal selectivities, likely owing to background reactions involving Cl2 and chlorine free radical (entries 4 and 5). The addition of 10 mol % amylene, a known Cl2 scavenger, 12 greatly favors methylene functionalization (97.7%, ks/kt = 4.2), albeit at low conversion (entry 6). We found that added base could serve a similar role without decreasing conversion, with higher yield at 55 °C (entries 7 and 8). The high level of secondary selectivity in this functionalization of a simple cyclic hydrocarbon is higher than any known system for aliphatic C–H chlorination.

Table 2.

Sterically Selective Aliphatic C–H Chlorination of Diverse Hydrocarbons with Bulky N-Chloroamide 1.

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| entry | reagents | % 2° Cl | % 3° Cl | ksecondary/ktertiary |

| 1 | NCS, AIBN, 60 °C (neat in 2) | 75.9 | 24.1 | 0.31 |

| 2 | SO2Cl2, BPO, 85 °C | 73.9 | 26.1 | 0.28 |

| 3 | Mn(TPP)Cl/NaOCl | 79.1 | 20.9 | 0.38 |

| 4 | chloroamide 1, hv, rt | 74.5 | 25.5 | 0.29 |

| 5 | chloroamide 1, BPO, 65 °C | 75.2 | 24.8 | 0.30 |

| 6 | chloroamide 1, BPO, 10 mol % amylene, 65 °C | 97.7 (<5% yield) | 2.3 | 4.2 |

| 7 | chloroamide 1, hv, 1 equiv Cs2CO3, rt | 93.3 (44% yield) | 6.7 | 1.4 |

| 8 | chloroamide 1, hv, 1 equiv Cs2CO3, 55 °C | 98.5 (74% yield) | 1.5 | 6.6 |

|

| ||||

| entry | substrate (1 equiv) | chlorination products | yield (%) | |

|

| ||||

| 9 |

5 |

6 |

54 exo:endo >99:1 |

|

| 10b |

7 |

8 |

9 |

79 8:9 >99:1 |

| 11b |

10 |

11 |

12 |

73 11:12 11:1 |

| 12 |

13 |

14 |

15 |

69 14:15 19:1 |

See Table 1 for conditions. Yields and selectivities were determined by GC analysis. For further details regarding product distributions, see the Supporting Information.

Reaction yields determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy of crude reaction mixtures using an internal standard.

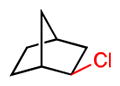

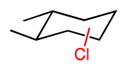

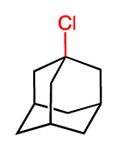

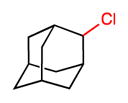

We extended our steric selectivity studies to additional hydrocarbon substrates such as norbornane, which under our standard chlorination conditions delivered a 54% yield of 2-exo-chloronorbornane as a single product (entry 9). As comparison, the C–H chlorination of norbornane with common reagents (e.g., Cl2 or SO2Cl2) leads to mixtures of the exo and endo isomers.11 Both trans- and cis-1,2-dimethyl cyclohexanes– benchmark substrates for sterically-selective aliphatic C– H functionalizations13–exhibited excellent methylene selectivity (entries 10 and 11). Adamantane C–H chlorination involving chlorine free radical is documented to be a poorly selective process, with kt/ks = 3.5.14 Reaction of adamantane under our standard reaction furnished the two regioisomers in a 19:1 ratio (kt/ks = 57), favoring functionalization of the less hindered tertiary site, and highlighting the unique selectivity profile of the current system.

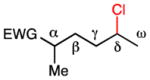

Next we surveyed the potential to achieve an electronically site-selective C–H chlorination using an array of functionalized linear hydrocarbon substrates (Table 3). Using methyl hexanoate as a test substrate, reactions involving either sulfuryl chloride (entry 1) or Mn(TPP)Cl/NaOCl (entry 2) proceeded with relatively poor selectivity between the most electronrich γ and δ positions. As observed with methylcyclohexane in Table 2, reactions with N-chloroamide 1 under radical initiation (entry 3) also resulted in a poorly selective reaction. Under our optimized conditions in the presence of base, we significantly increase the selectivity for the most electron rich (δ) site in the molecule. Chlorination at the δ site accounts for 57.6% of all chlorination products (entry 4, 83% combined yield).

Table 3.

Studies of the Electronic Site Selectivity of the Aliphatic C–H Chlorination with N-Chloroamide 1.

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| entry | reagents | % selectivity of chlorination | |||||

| α | β | γ | δ | ω | |||

| MeO2C —CH2—CH2—CH2—CH2—CH3 | |||||||

| 1 | SO2Cl2, BPO, 85 °C | — | 12.1 | 37.7 | 42.0 | 8.2 | |

| 2 | Mn(TPP)Cl/NaOCl | — | 8.2 | 43.7 | 44.8 | 3.3 | |

| 3 | chloroamide 1, BPO, 65 °C | — | 10.8 | 37.9 | 42.4 | 8.9 | |

| 4 | chloroamide 1, hv, 1 equiv Cs2CO3, 55 °C | 3.6 | 4.6 | 19.7 | 57.6 | 14.4 | |

| (83% combined yield) | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| substrate (1 equiv) | % selectivity of chlorination | combined yield (%) | |||||

| α | β | γ | δ | ω | |||

| EWG —CH2—CH2—CH2—CH2—CH3 | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| 5 |

17 |

— | — | 4.9 | 81.2 | 13.9 | 80 |

| 6 |

18 |

— | — | 15.0 | 65.9 | 19.1 | 79 |

| 7 |

19 |

9.2 | 5.7 | 15.3 | 56.9 | 12.9 | 74 |

| 8 |

20 |

— | 9.0 | 19.8 | 57.3 | 13.8 | 89 |

| 9 |

21 |

3.5 | 5.9 | 16.2 | 56.2 | 18.1 | 86 |

| 10 |

22 |

23.9 | 65.5 | 7.5 | 70 | ||

All reactions were performed with [substrate]0 = 1.0 M in PhH at rt under visible light irradiation with 1 equiv of substrate and 2 equiv chloroamide. Yields and selectivities determined by GC analysis.

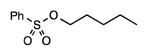

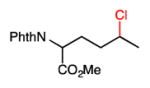

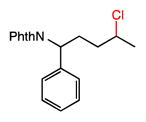

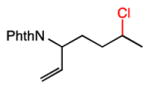

Other synthetically versatile, electron-withdrawing functionality effective at differentiating the methylene sites included protected amines, nitriles, alkyl chlorides, acetates, and sulfonate groups (entries 5–9). The δ selectivity in these studies ranged from 56% to 81%, with the phthalimide group providing the highest level of site selectivity. The general trend in these studies is greater δ selectivity with increased electron withdrawal of the substituent present. The chlorination of n-hexane indicates the possibility of a steric component to the C–H chlorination, with 65.5% 2-chlorohexane produced.

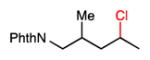

We further explored the site selectivity of the C–H chlorination with functionalized acyclic substrates containing more reactive C–H bonds at tertiary, benzylic, and allylic sites. The results in Table 4 clearly indicate that electronic (and possibly steric) factors are capable of deactivating these typically more reactive C–H bonds in favor of more electron-rich methylene sites. This electronically-dictated selectivity is substantial with multiple functional groups, and with methyl substitution at both the α and β positions of the chain (entries 1–4). The chlorination of phthalimide-protected norleucine methyl ester displays a major preference for the δ site (77.5% selectivity) owing to the strong polar deactivation of the sites adjacent to the amino acid functionality.

Table 4.

Site Selectivity of the Aliphatic C–H Chlorination with N-Chloroamide 1 in the Presence of More Reactive C–H Bonds and Substrate Unsaturation.

| entry | major chlorination product | % selectivity | combined yield (%)a | sites of minor chlorination (% selectivity) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

|

||||

|

| ||||

| 1 | 23: EWG = PhthN | 75.4 | 88 | γ = 8.8; ω = 15.7 |

| 2 |

|

68.3 | 76 | γ = 18.3; ω = 13.6 |

|

| ||||

| 3 |

25 |

63.6 | 69 | β = 2.4; γ = 7.5; ω = 26.5 |

|

| ||||

| 4 |

26 |

77.5 | 66 | ω = 22.5 |

|

| ||||

| 5 |

27 |

67.9 | 81 | γ = 14.9; ω = 17.1 |

|

| ||||

| 6 |

28 |

74.0 | 78 | α = 6.5; ω = 18.9 |

|

| ||||

| 7 |

29 |

100 | 65b | |

All reactions were performed with [substrate]0 = 1.0 M in PhH at rt under visible light irradiation with 1 equiv of substrate and 2 equiv chloroamide. Selectivities determined by GC analysis.

Yields determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy of the crude reaction mixture using 2,5-dimethylfuran as an internal standard.

Isolated yield with 1 equiv chloroamide.

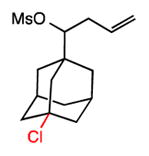

An area of significant interest was the possibility of achieving site-selective aliphatic C–H chlorination in the presence of substrate unsaturation. This chemoselectivity issue remains a roadblock in applying alkane functionalization to many complex substrates, particularly those containing alkenes. This is unsurprising given the propensity for electrophilic heterocycles or metal-oxo complexes–both widely used for alkane functionalization–to react with alkenes. Our preliminary studies in this area are promising (entries 5–7), demonstrating successful C–H chlorinations of substrates with both arene and alkene substitution. Of particularly note is the adamantane functionalization in the presence of a simple allyl group (entry 7). We anticipate that this unique aspect of aliphatic C–H functionalization with tuned amidyl radicals will facilitate applications across a broad range of complex substrates.

The ease of preparation of N-chloroamides, in addition to the useful levels of site selectivity in the reactions, offers attractive opportunities in the C–H chlorination of complex molecules (eqs 1 and 2). Functionalized adamantanes form the structural core of diverse small molecule drugs, yet there are few mild, site-selective protocols available for the C–H functionalization of these compounds. The chlorination of the N-phthalimide derivative of antiviral drug rimantadine (30) using N-chloroamide 1 provided chlorinated derivative 31 in good isolated yield (66%), with complete site-selectivity for the less-hindered tertiary C–H site (eq 1).

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

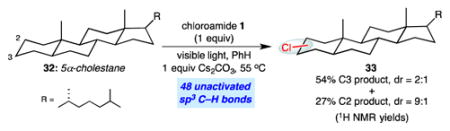

5α-Cholestane is a challenging substrate for site-selective C–H functionalization owing to the presence of 48 unactivated C–H bonds with little electronic differentiation considering the absence of heteroatomic functionality. The functionalization of 32 using 1 equiv of reagent 1 favors C3-chlorination (C3:C2 = 2:1) and provides an 81% yield of chlorinated products (eq 2). By comparison, the functionalization facilitated by the bulky, designed catalyst Mn(TMP)Cl (TMP = tetramesitylporphyrin) provides a C3:C2 of 1.5:1 in 55% yield using 3 equiv of NaOCl.7 We anticipate that the practicality, scalability, and site selectivity of this C–H halogenation are well suited for applications in target-oriented synthesis, as demonstrated by the concise synthesis of the antineoplastic agent chlorolissoclimide described herein.

APPLICATION TO THE SYNTHESIS OF CHLOROLISSOCLIMIDE

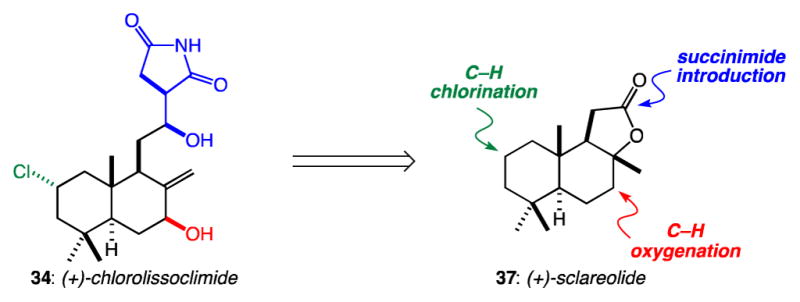

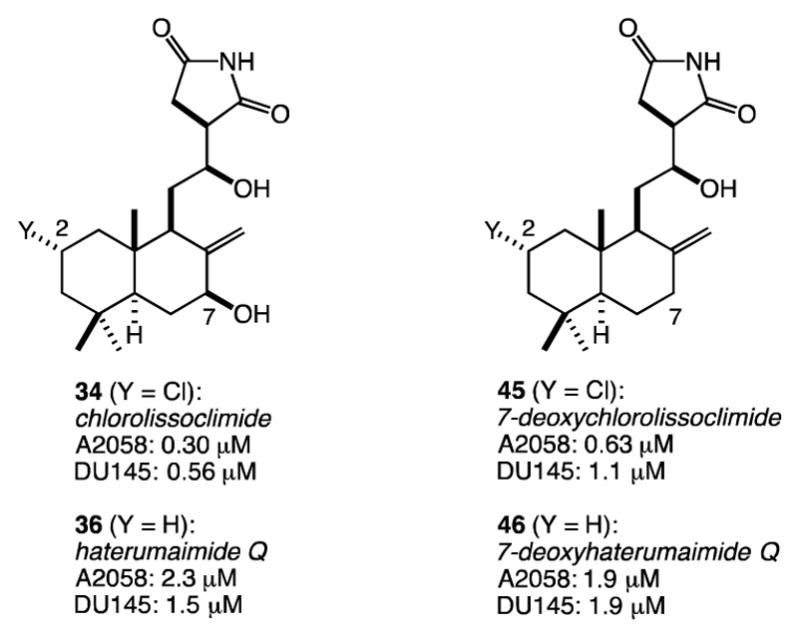

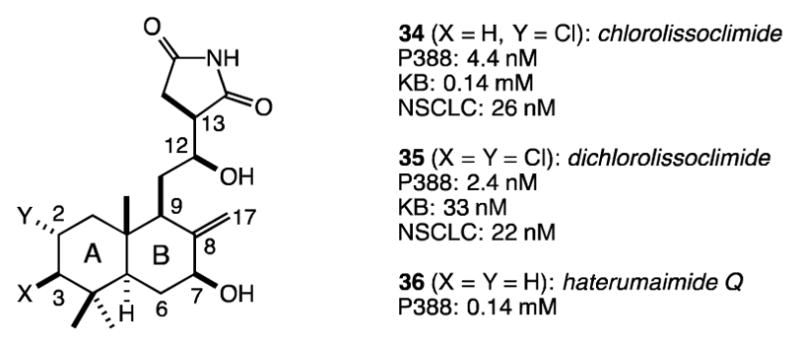

In the early 1990s, the groups of Malochet-Grivois and Roussakis described the structures and cytotoxic activities of the succinimide-containing labdane diterpenoids chlorolissoclimide and dichlorolissoclimide (34 and 35, respectively, Figure 1).15,16 Initially, 35 was shown to have potent activity against both the P388 murine leukemia cell line (IC50 = 2.4 nM) and the KB human oral carcinoma cell line (33 nM).15a Later, both 34 and 35 were shown to interfere with the cell cycle at the G1 phase of non-small-cell bronchopulmonary carcinoma cells (NSCLC-N6), causing antiproliferation.15b

Since 2001, the groups of Ueda/Uemura and Schmitz have reported about 20 closely related labdane diterpenoids that they have called the haterumaimides (see 36, for example).17 Many of these compounds show equally impressive levels of cytotoxicity. In spite of the obvious potential interest in these compounds from the biological perspective, as well as some particularly interesting biogenetic peculiarities—both the C2-chloride and the succinimide are very unusual—only three groups have reported work toward these compounds. Jung and co-workers studied methods to introduce the two chlorides onto simplified decalin scaffolds.18 The González/Betancur-Galvis and Chai groups looked at methods to install the succinimide group onto aldehyde 38 (Scheme 1) derived from readily available (+)-sclareolide (37); the former study used an unselective aldol addition of a succinimide enolate,19 and the latter used Evans aldol chemistry to introduce the heterocycle via a 4-step sequence, but could not avoid isomerization of the C8–C17 exocyclic alkene into the endocyclic positions, nor could these isomers be fully separated from one another.20 In short, there have been no completed syntheses in this family of structurally and biologically intriguing natural products.

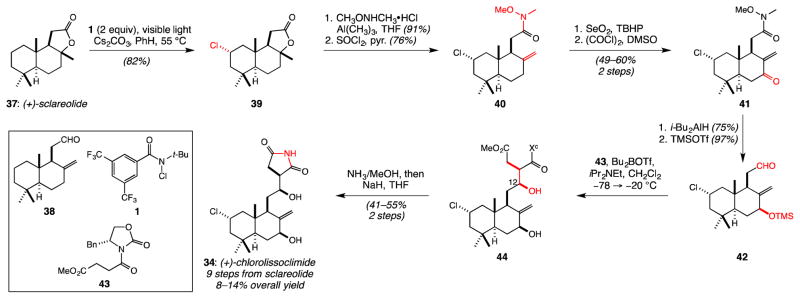

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of (+)-chlorolissoclimide by C–H functionalization of (+)-sclareolide.

As part of a broader study of this family of diterpenoids, we questioned whether C–H functionalization methods might permit the conversion of sclareolide to chlorolissoclimide (Figure 3). In reverse order, key steps would include the stereocontrolled introduction of the β-hydroxysuccinimide—which had proved challenging in earlier studies19,20—stereoselective C7-oxygenation, and regio- and stereoselective C2-chlorination.

Figure 3.

A plan for the conversion of sclareolide to chlorolissoclimide

Previous reports strongly suggested that the C2 position of sclareolide is the most activated for C–H functionalization under radical conditions.21 Prompted by the efficient C2-bromination of sclareolide from the Alexanian group,8 a collaboration was borne to gain efficient access to 2-chlorosclareolide for the purposes of a concise synthesis of chlorolissoclimide. Using reagent 1, we converted 37 into 2-chlorosclareolide (39)7a,22 with remarkable efficiency, even on gram scale. The selectivity of this reagent is outstanding: only product 39 and traces of residual sclareolide can be observed in the 1H NMR spectra of the crude reaction product. Weinreb aminolysis of the lactone and dehydration of the tertiary carbinol—following a process previously performed on sclareolide23—afforded 40 in good yield. C7-oxygenation was performed by selenium dioxide-mediated allylic oxidation19,24 to afford the axial C7 allylic alcohol, which was subjected to Swern oxidation to give enone 41. Concurrent reduction of the Weinreb amide and the enone was efficient and stereoselective for the introduction of the equatorial C7-hydroxyl group. Silylation of this alcohol afforded 42, whose aldehyde was subjected to our optimized sequence for introduction of the β-hydroxysuccinimide.

Evans aldol addition of known imide 4320,25 to aldehyde 42 was initially low-yielding and inconsistent, which we attributed to non-productive coordination of the boron Lewis acid to the pendant ester of 43. This issue was resolved by pretreatment of 43 with dibutylboron triflate for 30 min at −78 °C prior to addition of Hünig’s base, resulting in a reliable aldol addition. The labile TMS ether, which is important for reaction efficiency, is cleaved in this step. Direct ammonolysis of the crude imide (44) in methanol prevented undesired lactone formation as previously observed by Chai and co-workers;20 immediate imide formation via the presumed N-sodiated amide directly affords the β-hydroxysuccinimide without alkene migration and completes the first synthesis of (+)-chlorolissoclimide. This sequence is general and reliable, and this technical advance will prove important in the synthesis of the whole family of lissoclimides/haterumaimides. Notably, chlorolissoclimide is obtained in up to 14% overall yield via the nine-step sequence described in Scheme 1.

Variants of the same sequence have led to the synthesis of haterumaimide Q (36) and the 7-deoxy analogues of both 34 and 36 (45 and 46, respectively, Figure 4).26 We have evaluated all four compounds for their toxicity to aggressive prostate and melanoma cancer cell lines (DU145 and A2058, respectively). While we have found these compounds to be active at about the micromolar level, they are clearly much less potent toward these more relevant cell lines compared with the P388 murine leukemia cell line, against which all haterumaimides and lissoclimides have previously been tested.15,17 Clearly a larger panel of cell lines should be evaluated, given the previously reported potency of chlorolissoclimide against non-small-cell lung cancer (IC50 = 26 nM, see Figure 1). With respect to the two cell lines evaluated in this study, we recognize that this series of compounds affects both the prostate and melanoma cell lines about equally, and that the activities vary less than an order of magnitude depending upon the presence or absence of a C2-chloride or a C7-hydroxyl group.

Figure 4.

Activities (IC50 values) of chlorolissoclimide and analogues against aggressive tumor cell lines (A2058: melanoma; DU145: prostate)

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, we report a practical, site-selective approach to aliphatic C–H chlorination using N-chloroamides and visible light. While the chlorination of alkanes is commonly a poorly selective process owing to the promiscuity of chlorine free radical, these amidyl radical-mediated reactions provide sterically- and electronic-dictated site selectivities that enable chlorination of complex molecules with diverse C–H bonds. These studies also indicate the potential for chemoselective aliphatic C–H functionalization in the presence of alkenes and arenes. The trivial preparation of N-chloroamides, and the use of substrate as the limiting reagent in all cases, bodes well for applications in complex synthesis. In that vein, we also report the first synthesis of natural products in the lissoclimide/haterumaimide family of potent cytotoxins using this chlorination method as the first step. Our semi-synthesis of chlorolissoclimide starting with the gram-scale selective chlorination of (+)-sclareolide is short and efficient, and includes the first example of a stereocontrolled radical halogenation for the incorporation of a halogen-bearing stereogenic center of a natural product.27 The transformation itself is likely relevant to the biosynthesis of the 2-chlorinated lissoclimides and haterumaimides. That this chlorination reaction can support the synthesis of a complex natural product clearly demonstrates its practicality.

Additionally, in the context of the chlorolissoclimide synthesis, we have developed a straightforward and general solution to the β-hydroxysuccinimide motif that is common to all active members of this natural product family. Finally, we have learned that chlorolissoclimide (34) and analogues haterumaimide Q (36), 7-deoxychlorolissoclimide (45), and 7-deoxyhaterumaimide Q (46) are cytotoxic to aggressive melanoma and prostate cancer cell lines with IC50 values of about 1 μM.

Efforts to further improve the site selectivity of the C–H chlorination and applications to other complex substrates are underway. We are also in the process of expanding our work in the synthesis of haterumaimide natural products to better understand their structure-activity relationship. Each of these studies will be reported in due course.

Supplementary Material

Figure 2.

Chlorolissoclimide, dichlorolissoclimide, and haterumaimide Q with IC50 values against cancer cell lines

Acknowledgments

Financial support was provided by the ACS PRF (55108-ND1 to E.J.A.) and the NIH (GM-086483 to C.D.V. and P30 CA-033572 “Drug Discovery and Structural Biology Core of the City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center” to D.A.H.). R.K.Q. thanks the NSF for a Graduate Research Fellowship and Y.S. was supported by a Feodor Lynen Postdoctoral Fellowship from the Humboldt Foundation.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supporting Information. Experimental procedures and spectral data for all new compounds, and full descriptions of the syntheses of compounds 36, 45, and 46, This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.(a) McBee ET, Hass HB, Neher CM, Strickland M. Ind Eng Chem. 1942;34:296. [Google Scholar]; (b) McBee ET, Hass HB. Ind Eng Chem. 1941;34:137. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Skell PS, Baxter HN. J Am Chem Soc. 1985;107:2823. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Djerassi C. Chem Rev. 1948;43:271. doi: 10.1021/cr60135a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gribble GW. Naturally Occurring Organohalogen Compounds: A Comprehensive Update. Springer-Verlag; Weinheim, Germany: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gutekunst WR, Baran PS. Chem Soc Rev. 2011;40:1976. doi: 10.1039/c0cs00182a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Minisci F, Galli R, Galli A, Bernardi R. Tetrahedron Lett. 1967;8:2207. [Google Scholar]; (b) Deno NC, Fishbein R, Wyckoff JC. J Am Chem Soc. 1971;93:2065. [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Liu W, Groves JT. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:12847. doi: 10.1021/ja105548x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Liu W, Groves JT. Acc Chem Res. 2015;48:1727. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.5b00062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmidt VA, Quinn RK, Brusoe AT, Alexanian EJ. J Am Chem Soc. 2014;136:14389. doi: 10.1021/ja508469u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.White MC. Science. 2012;335:807. doi: 10.1126/science.1207661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson RA, Greene FD. J Org Chem. 1975;40:2192. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huyser ES, editor. Methods in Free-Radical Chemistry. 1–2. Dekker; New York: 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kraus GA, Taschner MJ. J Org Chem. 1980;45:1175. [Google Scholar]

- 13.(a) Gormisky PE, White MC. J Am Chem Soc. 2013;135:14052. doi: 10.1021/ja407388y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kamata K, Yonehara K, Nakagawa Y, Uehara K, Mizuno N. Nature Chem. 2010;2:478. doi: 10.1038/nchem.648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Canta M, Font D, Gomez L, Ribas X, Costas M. Adv Synth Catal. 2014;356:818. [Google Scholar]; (d) Moteki SA, Usui A, Zhang T, Alvarado CRS, Maruoka K. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2013;52:8657. doi: 10.1002/anie.201304359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith GW, Williams HD. J Org Chem. 1961;26:2207. [Google Scholar]

- 15.(a) Malochet-Grivois C, Cotelle P, Biard JF, Hénichart JP, Debitus C, Roussakis C, Verbist JF. Tetrahedron Lett. 1991;32:6701. [Google Scholar]; (b) Malochet-Grivois C, Roussakis C, Robillard N, Biard JF, Riou D, Debitus C, Verbist JF. Anti-Cancer Drug Design. 1992;7:493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Roussakis C, Charrier J, Riou D, Biard JF, Malochet C, Meflah K, Verbist JF. Anti-Cancer Drug Design. 1994;9:119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.For X-ray crystallographic studies of 34, see: Toupet L, Biard J-F, Verbist J-F. J Nat Prod. 1996;59:1203.

- 17.(a) Uddin MJ, Kokubo S, Suenaga K, Ueda K, Uemura D. Heterocycles. 2001;54:1039. doi: 10.1021/np010066n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Uddin MJ, Kokubo S, Ueda K, Suenaga K, Uemura D. J Nat Prod. 2001;64:1169. doi: 10.1021/np010066n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Uddin MJ, Kokubo S, Ueda K, Suenaga K, Uemura D. Chem Lett. 2002;10:1028. [Google Scholar]; (d) Fu X, Palomar AJ, Hong EP, Schmitz FJ, Valeriote FA. J Nat Prod. 2004;67:1415. doi: 10.1021/np0499620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Uddin J, Ueda K, Siwu ERO, Kita M, Uemura D. Bioorg Med Chem. 2006;14:6954. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2006.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jung ME, Gomez AV. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993;34:2891. [Google Scholar]

- 19.González MA, Romero D, Zapata B, Betancur-Galvis L. Lett Org Chem. 2009;6:289. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nguyen TM, Vu NQ, Youte J-J, Lau J, Cheong A, Ho YS, Tan BSW, Yogonathan K, Butler MS, Chai CLL. Tetrahedron. 2010;66:9270. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Select examples of 2-functionalization of sclareolide: Oxygenation: Chen MS, White MC. Science. 2010;327:566. doi: 10.1126/science.1183602.Fluorination: Liu W, Huang X, Cheng M-J, Nielsen RJ, Goddard WA, III, Groves JT. Science. 2012;337:1322. doi: 10.1126/science.1222327.Halperin SD, Fan H, Chang S, Martin RE, Britton R. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2014;53:4690. doi: 10.1002/anie.201400420.Bloom S, Knippel JL, Lectka T. Chem Sci. 2014;5:1175.Xia JB, Ma Y, Chen C. Org Chem Front. 2014;1:468. doi: 10.1039/C4QO00057A.Zhang X, Guo S, Tang P. Org Chem Front. 2015;1:806.Chlorination: (g) ref 7a. Bromination: (h) ref 8. Kee CW, Chan KM, Wong MW, Tan C-H. Asian J Org Chem. 2014;3:536–544.Azidation: Huang X, Bergsten TM, Groves JT. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:5300. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b01983.Zhang X, Yang H, Tang P. Org Lett. 2015;17:5828. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b03001.

- 22.We initially began these studies using Groves’s chlorination reaction (ref 7a), but unfortunately this transformation was not efficient enough to support our synthesis efforts.

- 23.(a) de la Torre MC, García I, Sierra MA. Tetrahedron Lett. 2002;43:6351. [Google Scholar]; (b) Boukouvalas J, Wang JX, Marion O, Ndzi B. J Org Chem. 2006;71:6670. doi: 10.1021/jo0610154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Umbreit MA, Sharpless KB. J Am Chem Soc. 1977;99:5526. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hajra S, Giri AK, Karmakar A, Khatua S. Chem Commun. 2007:2408. doi: 10.1039/b618699h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Please see the Supporting Information for details.

- 27.Chung W-j, Vanderwal CD. Angew Chem Int Ed. doi: 10.1002/anie201506388. in press. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.