Abstract

Sepsis is a life-threatening event predominantly caused by gram-negative bacteria. Bacterial infection causes a pronounced macrophage (MΦ) and dendritic cell (DC) activation that leads to excessive pro-inflammatory cytokine interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, and Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α production (cytokine storm), resulting in endotoxic shock. Previous experimental studies have revealed that inhibiting Nuclear Factor kappa Beta (NF-κB) signaling ameliorates disease symptoms; however, the contribution of myeloid p65 in endotoxic shock remains elusive. In this study, we demonstrate increased mortality in mice lacking p65 in the myeloid lineage (p65Δmye) compared to wild type (WT) mice upon ultra-pure LPS (U-LPS) challenge. We show that increased susceptibility to Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced shock was associated with elevated serum level of IL-1β and IL-6. Mechanistic analyses revealed that LPS-induced pro-inflammatory cytokine production was ameliorated in p65-deficient bone marrow–derived macrophages (BMDMs); however, p65-deficient “activated” peritoneal macrophages (MΦs) exhibited elevated IL-1β and IL-6. We show that the elevated pro-inflammatory cytokine secretion was due in part to increased accumulation of IL-1β mRNA and protein in activated inflammatory MΦs. The increased IL-1β was linked with heightened binding of PU.1 and CCAAT/Enhancer Binding Protein Beta (cEBPβ to Il1b and Il6 promoters in activated inflammatory MΦs. Our data provides insight into a role for NF-κB in the negative regulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines in myeloid cells.

Introduction

Sepsis is a life-threatening event that can be complicated by shock, coagulopathy, and multiorgan dysfunction, causing millions of deaths globally each year 1. Sepsis is predominantly caused by Gram-negative bacterial infection 2, and the host–microbial interaction promotes an acute immune/inflammatory response involving both humoral and cellular components that can cause endotoxic shock and death within a few days 3.

The major outer surface membrane component of Gram-negative bacteria cell wall is lipopolysaccharide (LPS). LPS interacts with the LPS-binding protein (LBP) and CD14 and binds toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) on mononuclear cells, including dendritic cells (DCs), monocytes, and macrophages (MΦs) 4. The LPS-TLR4 interaction leads to the recruitment of the adaptor proteins myeloid differentiation primary response protein 88 (MyD88) and toll/IL-1 receptor domain-containing adaptor inducing interferon beta (TRIF), stimulating the subsequent activation of the IκBα kinase (IKK) complex (IKKβ, IKKα, and NEMO) 5, 6. The activated IKK complex phosphorylates IκB, leading to IκB ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation, freeing NF-κB/Rel complexes, and enabling NF-κB translocation to the nucleus and transcription of NF-κB-responsive pro-inflammatory cytokines [e.g. Interleukin (IL)-1, IL-6, and Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α] 5–8. The mammalian NF-κB family comprises of five members, RelA (p65), RelB, c-Rel, p105/p50 (NFκB1), and p100/p52 (NF-κB2). The NF-κB pathway plays a critical functional role in LPS-induced inflammatory gene expression and LPS-induced lethality 5, 6, 8–10. The importance of p50 and p65 of the canonical pathway in the pathophysiology of sepsis has been demonstrated by increased nuclear binding activity of each subunit in both animal models and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) of patients with sepsis 11. Increased NFκB activity is associated with increased mortality and worse clinical outcomes 12, and inhibiting NF-κB activity protects mice from endotoxin-induced shock 13, 14.

The cytokines IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α are thought to promote many of the immunopathologic features of LPS-induced shock 4, 15. Elevated levels of plasma IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α are associated with the onset of septic shock 15–18. Administering LPS into the bloodstream results in a rapid increase in serum IL-1β and TNF-α the latter of which correlated with the pathophysiologic changes (fever, tachycardia, and slight hypertension) in humans 19. Furthermore, intravenous administration of TNF-α and/or IL1-β in mice and humans results in a septic shock–like state 15, 20–26. Though IL-6 has been shown to not have a causal role in septic shock, plasma IL-6 levels correlate with mortality from septic shock 18. Clinical and preclinical murine studies suggest that IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α have differential roles in immunopathogenesis of the septic shock reaction, including modulating thermoregulation, food intake, and lethality of sepsis 27, 28.

There are several lines of clinical and experimental evidence suggesting that pro-inflammatory cytokines derived from macrophages (MΦs) are important in the LPS-induced shock 4. LPS stimulation of human myeloid cell lines (THP-1 and U937) and PBMC-derived MΦs results in the induction of pro-inflammatory cytokine genes 29. Furthermore, transfer of MΦs from C3H/HeN mice to LPS-resistant C3H/HeJ mice reconstituted high sensitivity to the lethal effects of LPS 30. While there is substantial data independently linking NFκB signaling and MΦ-derived pro-inflammatory cytokine response to LPS-induced shock, the requirement of p65 NF-κB signaling in myeloid cells in LPS-induced shock has not been directly demonstrated. As studying the individual contributions of the NF-κB subunits in LPS-induced shock in vivo has been limited by the embryonic lethality of mice lacking p65 31, we recently have generated LysMCrep65fl/fl mice 32. In mice lacking p65 in the myeloid lineage (p65Δmye), we demonstrate increased mortality upon ultra-pure LPS (U-LPS) challenge that was associated with elevated serum levels of IL-1β and IL-6. We show that loss of p65 leads to increased IL-1β and IL-6 levels in peritoneal “activated” MΦs in response to U-LPS which was linked to increased binding of the transcription factors C/EBP-β and PU.1 to the associated genes regulatory elements. This study reveals an important role for NF-κB in restraining PU.1 and CCAAT/Enhancer Binding Protein Beta (cEBPβ-driven pro-inflammatory cytokine production in myeloid cells which confers protection from LPS-induced pro-inflammatory cytokine production and shock.

Material and Methods

Mice

Male and female lysozyme M (LysM)cre/cre RelA/p65fl/fl (RelA/p65Δmye, C57BL/6/129/SvEv) and LysMcre/cre RelA/p65+/+ (WT control line for RelA/p65Δmye mice)32. All mice were housed under specific pathogen–free conditions, animal care was performed by experienced veterinary technicians, and all experimental techniques were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC).

LPS-induced Shock

WT and RelA/p65Δmye mice received one intra-peritoneal (i.p.) injection of ultra-pure LPS from E. coli K12 (LPS-EK Ultrapure) (InvivoGen, San Diego, CA) (40 mg per kg body weight) diluted in pyrogen-free saline and evidence of LPS-induced shock was examined every 12 hrs. In initial dose response experiments 40mg/kg U-LPS was shown to generate a robust inflammatory response (cytokine production IL-1β, TNF-α and IL-6) in the absence of a rapid shock response in the WT C57BL6 mice. In accordance with CCHMC IACUC-approved protocols, we designated mice as experiencing irreversible LPS-induced shock via the following criteria: hunched posture, lethargy, labored breathing, no righting reflex response, and hypothermic (> 5°C temperature loss). When designated as experiencing LPS-induced shock, mice were immediately euthanized by CO2 inhalation.

BMDMs

Bone marrow was obtained from mice femurs using 5 mL harvesting buffer (25 mM HEPES/50 μg/mL Gentamycin in 1X HBSS). Cells were passed through a 70-μM filter and centrifugedat 1200 rpm before being resuspended in 20 mL BMDM media (20% M-CSF in 10% FBS containing complete DMEM) and cultured for 5 days (37°C, 5% CO2).

Peritoneal MΦs

Mice were intraperitoneally injected with 1 mL 3.85% thioglycollate as previously described 33 Three days after the i.p. injection, a peritoneal lavage was performed, and cells were centrifuged and resuspended in 25 mL 10% FBS complete DMEM and plated for 4 h for adherence. Cells were then washed with PBS and detached with trypsin/EDTA (Life Technologies; Carlsbad, CA) at 37°C for 5 min and resuspended in 10% FBS complete DMEM.. Cells were then gently scraped off and resuspended in 10% FBS complete DMEM for analyses.

MΦ stimulation

BMDMs (1 × 105 cells/250 μL) were plated in a 96-well plate and incubated overnight at 37°C, 5% CO2. BMDMs or peritoneal MΦs (2 × 106 or 2.5 × 105) were stimulated with 0, 10 or 100 ng/mL ultra-pure LPS from E. coli K12 (LPS-K12 Ultrapure) (InvivoGen, San Diego, CA) for the indicated hours according to experiments and then stimulated for 1 h with 2 mM adenosine triphosphate (ATP) (InvivoGen; San Diego, CA) for inflammasome activation. Supernatant and mRNA were collected and analyzed for cytokine induction.

ELISA

IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α levels were measured in the supernatant after cell culture using the ELISA Duo-Set kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (R&D System; Minneapolis, Minn). Serum Type I IFN levels were determined with the IFNβ bioassay as previously described 34.

FACS analysis

Single-cell suspensions were washed with FACS buffer (PBS/1% BSA) and incubated for 30 min at room temperature with combinations of the following antibodies: PE anti-mouse F4/80 (clone CI:A3-1; AbD Serotec; Raleigh, NC), PE-Cy7 anti-mouse CD11b (clone M1/70; BD Pharmingen; San Jose, CA), Alexafluor-647 anti-mouse Ly6C (clone ER-MP20; AbD Serotec; Raleigh, NC), and FITC anti-mouse Ly6G (clone 1A8; BD Pharmingen; San Jose, CA). Cells were washed once with FACS buffer and analyzed on a FACSCanto II (BD Immunocytometry System; San Jose, CA), and analysis was performed using Flow Jo software (Tree Star; Ashland, OR). For experiments conducted to determine immune cell populations in the peritoneal cavity, the following antibodies were used: APC anti-mouse CD19 (clone 1D3), PE anti-mouse CD23 (clone B3B4), PE-Cy7 anti-mouse IgM (clone R6-60.2) or CD3 (clone145-2C1) or FcεRIα (clone MAR-1), FITC anti-mouse B220 (clone RA3-6B2), PerCp-Cy5.5 anti-mouse CD11b (clone M1/70) or CD11c (clone HL3), AlexaFluor750 anti-mouse c-KIT (clone 2B8) or CD4 (clone GK1.5, BD Pharmingen; San Jose, CA), and PE anti-mouse MHC class II (clone NIMR-4; eBioscience; San Diego, CA). All antibodies were used in a 1:200 dilution in FACS buffer.

Western blot

BMDM or peritoneal MΦs after stimulation were lysed using mammalian protein extraction reagent (M-PER; Life Technologies; Carlsbad, CA). Approximately 40 μg of protein extract was separated on a 4%–12% Bis-Tris gel and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane (Life Technologies; Carlsbad, CA). The following antibodies were used: rabbit anti-mouse caspase-1 p10 (M20; Santa Cruz; Santa Cruz, CA) and goat anti-mouse IL-1β/IL-1F2 (R&D Systems; Minneapolis, Minn) followed by goat anti-rabbit (Calbiochem; Darmstadt, Germany) or sheep anti-goat (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories; West Grove, PA) peroxidase-conjugated antibodies. Rabbit anti-mouse β-actin (Sigma; St. Louis, MO) was used as loading control, and ECL-plus detection reagent (Life Technologies; Carlsbad, CA) was used for detection.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay

Peritoneal MΦs (~2 × 107 cells) were cross-linked with 0.8% formaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature. Cells were collected, lysed, and then sonicated for 9 min (Peak power 175 W, Duty factor 5%, Cycles/burst 200 count) at 4°C using a Covaris S series Sonicator (Covaris; Woburn, MA), yielding chromatin fragments with an average size of around 400 bp. To reduce unspecific binding, each chromatin sample was pre-cleared with 10 μL Dynabeads® Protein G magnetic beads (Life Technologies; Carlsbad, CA). One μg of primary antibody for C/EBP-β (sc-150X; Santa Cruz Biotechnology; Santa Cruz, CA) or PU.1 (Spi-1) (sc-352X; Santa Cruz Biotechnology; Santa Cruz, CA) was bound to 5 μL of Dynabeads® Protein G magnetic beads (Life Technologies; Carlsbad, CA) for 1 h at room temperature on a rotating wheel. Five μg of chromatin complexes was then added to the antibody/beads mix and immunoprecipitated for 14–16 h at 4°C on a rotating wheel. The precipitates were washed with 1 mL twice for each of the following buffers in succession: low-salt wash buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.6, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% SDS, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate, 1% Triton X-100, 150 mM NaCl), high-salt wash buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.6, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% SDS, 0.1% sodium deoxycholate, 1% Triton X-100, 400 mM NaCl), LiCl wash buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.6, 1 mM EDTA, 250 mM LiCl, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.5% Nonidet P-40), and Triton X-100 buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.6, 1 mM EDTA, 0.2% Triton X-100). Chromatin complexes were eluted in 100 μL elution buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.6, 1 mM EDTA, 250 mM NaCl, 0.3% SDS) and incubated at 37°C for 1 h with shaking. To degrade proteins and reverse cross-link, 5 μL of Proteinase K solution (Life Technologies; Carlsbad, CA) was added to the eluates and incubated at 37°C for 1 h followed by incubation at 65°C for 6 h. DNA was purified with a QIAquick® PCR purification kit (Qiagen; Valencia, CA), eluted in 30 μL molecular biology grade water (Sigma; St. Louis, MO), and analyzed with quantitative real-time PCR.

Real-time PCR analysis

The RNA samples (1 μg) were subjected to reverse transcription analysis using SuperScript II reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies; Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Mouse Il1b, caspase-1, Ifnb, Ccl12, and Cxcl10 were quantified by real-time PCR using the iQ5 multicolor real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad Laboratories; Hercule, CA) with iQ5 software V2.0 and LightCycler FastStart DNA Master SYBR Green I. Sequence of primers and probes used for quantitative RT-PCR are described in Supplemental Table S1. Gene expression was determined as relative expression on a linear curve based on a gel-extracted standard and was normalized to Hprt amplified from the same cDNA mix. Results were expressed as the gene of interest/Hprt ratio that had been normalized for each group to unstimulated p65Δmye group. For analyzing the ChIP samples, a region of the Il1b and Il6 promoters containing putative binding sites for C/EBP-β and PU.1 and an intronic region of the Gapdh gene were quantified with real-time quantitative PCR using the Taqman® Universal PCR Mastermix chemistry (Applied Biosystems® by Life Technologies; Carlsbad, CA) with Prime Time 5′ 6-FAM/ZEN/3′ IBFQ taqman probes (IDT; Coralville, IO). Primer sets used for either expression or ChIP analysis are reported in Supplemental Table S1.

MTT assay

Cells (1 × 106 or 5 × 104) were plated in a 96-well plate and stimulated with ultra-pure LPS from E. coli K12 (LPS-EK) at the indicated concentrations and lengths of time. Supernatant was poured off after stimulation, and 100 μL of 4 mg/mL MTT (Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis, MO) was added and followed by 1 h of incubation at 37°C. The formazan crystals were dissolved using 100 μL of MTT lysis buffer (10% SDS in isopropanol), and absorbance was measured at 570 nm and the background (OD 630 nm) subtracted. Results are presented as percentage of survival with the control (untreated cells) representing 100% survival.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical significance was determined by means of ANOVA, followed by the Tukey’s post-hoc test or a two-tailed unpaired T test with GraphPad Prism 5 (San Diego, CA). p < 0.05 was considered significant. N.D. represents values below the limit of detection.

Results

U-LPS challenge decreases survival rate in p65Δmye mice

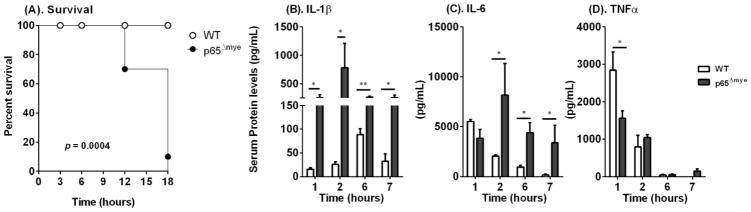

To determine whether myeloid-specific p65 regulates LPS-induced shock, p65Δmye (LysMCre p65fl/fl) mice and littermate WT (LysMCre p65WT/WT) control mice were administered U-LPS (40 mg/kg) by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection. In accordance with CCHMC IACUC-approved protocols, we designated mice as experiencing irreversible LPS-induced shock via the following criteria: hunched posture, lethargy, labored breathing, no righting reflex response, and hypothermic (> 5°C temperature loss). When designated as experiencing LPS-induced shock, mice were immediately euthanized. WT mice did not demonstrate evidence of LPS-induced shock 18 h after U-LPS challenge (Figure 1). In contrast, more than 30% (7/24) of the littermate age-, weight-, and strain-matched p65Δmye mice died within 12 h and 90% (21/24) died within 18 h of U-LPS injection (Figure 1; p < 0.0005). These data indicate that myeloid p65 deletion renders mice more susceptible to U-LPS challenge.

Figure 1. In vivo ultra-pure LPS (U-LPS) challenge results in increased pro-inflammatory cytokine production and mortality in p65Δmye mice.

(A). U-LPS (E. coli K12)–challenged survival of p65Δmye and littermate WT mice. Serum cytokine levels of B) IL-1β, C) IL-6, and D) TNF-α at indicated time points (hours) in WT and p65Δmye mice following one i.p. injection with U-LPS (E. coli K12) (40 mg/kg). Data represent the mean ± SEM of 2 independent experiments with (A). n = 7–11 mice per group and (B – D). n = 3–11 mice per group. (*p < 0.05) between groups.

U-LPS challenge increases pro-inflammatory cytokines and alters cell recruitment in p65Δmye mice

As LPS-induced shock is associated with innate immune activation, we examined pro-inflammatory cytokine levels in the sera and inflammatory cell populations in the peritoneal cavity of U-LPS–challenged WT and p65Δmye mice. U-LPS challenge of WT mice induced a potent pro-inflammatory cytokine response characterized by increased serum IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α (Figure 1B–D). Consistent with previous observations, we observed a rapid rise in serum IL-6 and TNF-α within 1–2 h and an IL-1β response by 6 h after U-LPS challenge in WT mice (Figure 1B–D). Notably, serum cytokine levels tapered by 6 h after U-LPS challenge in WT mice (Figure 1B–D). In p65Δmye mice, we observed a significantly more potent initial IL-1β– and IL-6–specific response (Figure 1B and C). Moreover, U-LPS challenge induced a significantly more rapid, stronger, and sustained IL-1β and IL-6 response, with serum IL-1β and IL-6 levels 30-fold and 4-fold higher respectively in the p65Δmye than WT mice at 2 h (Figure 1B and C). Though serum TNF-α levels 1 h after U-LPS challenge were reduced in the p65Δmye mice compared to WT mice, levels were comparable between groups throughout the rest of the time course (Figure 1D).

To investigate whether the heightened inflammatory response was reflective of altered cellular recruitment, we examined peritoneal cavity cell populations of WT and p65Δmye mice following U-L

PS challenge by flow cytometry analyses (Table 1). At steady state, levels of total MΦs (FSCmidSSClowCD11b+F4/80+), resident MΦs (CD11b+F4/80+Ly6ClowLy6G−), and mast cells (c-KIT+FcεRI+) were significantly reduced in p65Δmye mice compared to WT mice (Table 1). However, numbers of neutrophils (CD11b+F4/80med-lowLy6G+) were significantly higher in p65Δmye mice (Table 1). There was no difference in the numbers of peritoneal inflammatory MΦs (CD11b+F4/80+Ly6ChighLy6G−) and B cells (CD19+B220+) between groups. Intraperitoneal U-LPS challenge induced a cellular infiltrate into the peritoneal cavity of WT mice by 1 h (Table 1). We observed a significant increase in peritoneal resident and inflammatory MΦs, neutrophils (CD11b+F4/80midLy6G+), and B cells (CD19+B220+) following U-LPS challenge (Table 1). Similarly, we observed a significant increase in inflammatory MΦs and B cells in U-LPS–challenged p65Δmye mice compared with unchallenged p65Δmye mice; however, the total MΦ frequency was reduced compared to U-LPS challenged WT mice (Table 1). The number of neutrophils increased after U-LPS challenge in both groups; however, the fold change was 3 times greater in p65Δmye mice than in WT mice (Table 1). These data indicate that increased U-LPS–induced shock in mice with myeloid depletion of p65 was associated with elevated IL-1β and IL-6 response and neutrophil recruitment but with comparable inflammatory MΦ levels.

Table 1.

Cell populations in peritoneal cavity of WT and p65Δmye mice at steady state and following UP-LPS exposure.

| Cell population | Steady State Cell Number (×105) | P value | UP-LPS Cell Number (×105) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | P65Δmye | WT | P65Δmye | |||

| Total MΦ’s CD11b+F4/80+ |

1.64 ± 0.31 | 0.81 ± 0.12 | 0.02* | 3.93 ± 1.26 | 1.22 ± 0.34 | 0.06 |

| Inflammatory MΦ CD11b+F4/80+Ly6ChighLy6G− |

0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.28 | 0.41 ±0.06 | 0.46 ± 0.12 | 0.75 |

| Resident MΦ CD11b+F4/80+Ly6ClowLy6G− |

1.64 ± 0.31 | 0.75 ± 0.14 | 0.02* | 3.52 ± 1.20 | 0.76 ±0.24 | 0.04* |

| Neutrophils CD11b+F4/80med-loLy6G+ |

0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 0.02* | 0.66 ± 0.05 | 2.53 ± 0.21 | 0.001* |

| B cells CD19+B220+ |

0.36 ± 0.15 | 0.59 ± 0.13 | 0.27 | 5.21 ± 0.74 | 4.30 ±0.19 | 0.22 |

| Mast cells c-KIT+FcεRI+ |

0.03 ± 0.01 | 0.015 ± 0.01 | 0.02* | 0.10 ± 0.02 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 0.06 |

Data in the table represents the total cell numbers (×105) in the peritoneal cavity at steady state (n =7–8 mice per group) and 60 minutes following U-LPS (E. Coli K12) challenge (n = 3–4 mice per group). Data represented as mean ± SD are representative of three separate experiments; MΦs: macrophages; p values as indicated.

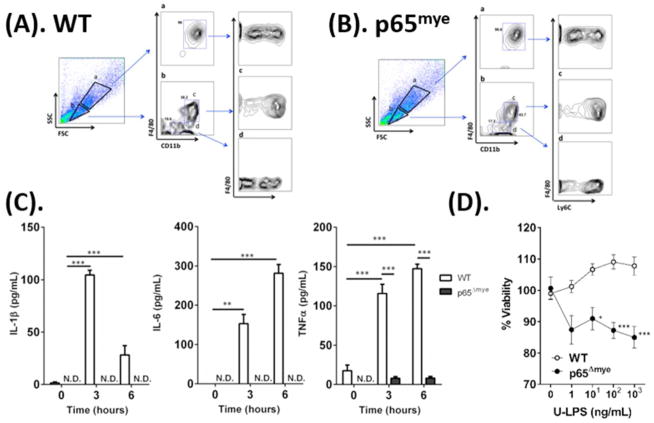

Decreased inflammation and viability in p65Δmye BMDMs upon U-LPS stimulation

As MΦs have long been associated with mortality in sepsis 35, we examined U-LPS responses in BMDMs from WT and p65Δmye mice to determine whether the exaggerated phenotype in p65Δmye mice can be attributed to an inherent defect in myeloid cells after p65 deletion (Figure 2). We initially examined BMDMs that were generated from bone marrow cells after in vitro stimulation with macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) for 5 days 32 as these cells represent a homogenous myeloid cell population that possess most characteristics of macrophages 36. We have previously demonstrated efficient and specific LysM-Cre–mediated deletion of RelA/p65 in the myeloid compartment by 1) loss of total RelA/p65 protein in RelA/p65Δmye BMDMs in the presence of normal levels of total RelA/p65 in the spleen and colonic epithelium of RelA/p65Δmye mice; 2) loss of RelA/p65 activation in RelA/p65Δmye BMDMs following LPS stimulation and 3) normal levels of IKK-α, c-Rel, and p105 in RelA/p65Δmye BMDMs supporting selective RelA/p65 deletion in myeloid cells, and that this is independent of effects of other components of the NF-κB signaling pathway 32. Flow cytometry analyses of WT and p65Δmye BMDMs revealed that the majority of the cultured cells were large in size with granular morphology (SSChiFSChi) (Figure 2A–B, gate a). This population was identified as F4/80+CD11b+ cells that consisted of both Ly6Clo and Ly6Chi cell subsets, representing both mature and immature MΦs, respectively. The comparable level of Ly6Clo and Ly6Chi cell subsets and level of expression of the BMDM maturation marker F4/8037 on WT and p65Δmye BMDM populations (Figure 2A–B), indicates that p65 is dispensable for the development and maturation of BMDMs in vitro. U-LPS stimulation of WT BMDMs induced a pronounced pro-inflammatory cytokine response (IL1β, IL-6, and TNF-α) that was evident at 3 and 6 hours post stimulation (Figure 2C). In contrast, U-LPS stimulation of p65Δmye BMDMs did not induce a pronounced IL1β, IL-6, and TNF-α response. Examining the BMDM viability after U-LPS stimulation did reveal a significant reduction in viability in p65Δmye BMDMs compared to WT BMDMs after high U-LPS (10 ng/mL or higher) stimulation (Figure 2D); however, we only observed ~10% reduction in viability in p65Δmye BMDMs compared to WT BMDMs, suggesting that the absence of a pro-inflammatory cytokine response to U-LPS in p65Δmye BMDMs is not likely attributed to decreased myeloid cell viability. Collectively, these data suggest that myeloid p65 deletion decreases a BMDM’s capability to produce pro-inflammatory cytokines after U-LPS stimulation.

Figure 2. In vitro ultra-pure LPS (U-LPS) stimulation decreases pro-inflammatory cytokine expression and viability in p65Δmye BMDMs.

A and B, Flow cytometry analyses of F4/80, CD11b, and Ly6C expression in WT and p65Δmye BMDMs, respectively. Panel labels of a-d represent indicated gatings. C, Pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α secretion from BMDMs pretreated for 0, 3, or 6 h with 100 ng/mL U-LPS (E. coli K12) followed by 1 h of 2 mM ATP stimulation. D, Viability of BMDMs determined by MTT assay. Cells were treated with 0, 1, 10 100, or 1000 ng/mL U-LPS (E. coli K12) for 24 h prior to MTT assay. Data represent the mean ± SEM from n = 2–3 separate experiments. Significant differences indicated (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.005) between groups. N.D., not detectable.

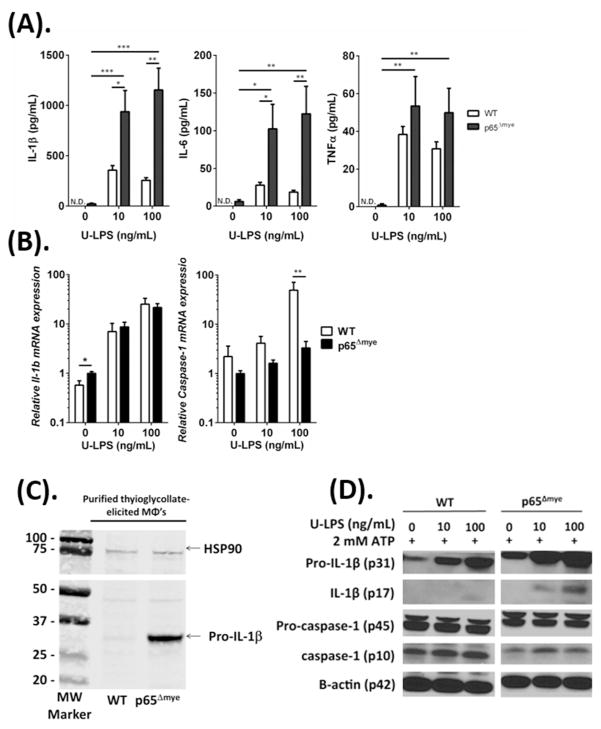

U-LPS stimulation results in increased pro-inflammatory cytokine production in p65Δmye peritoneal MΦs

As our BMDM studies did not reconcile our in vivo observations, we next examined the effect of p65 deletion on inflammatory MΦs. We assessed the responsiveness of thioglycollate-elicited MΦs to U-LPS. Peritoneal cells were acquired from WT and p65Δmye mice 3 days after i.p. thioglycollate injection and purity assessed after 4 hours adherence (Supplemental Figure S1). Flow cytometry analyses of peritoneal cells revealed that myeloid deletion of p65 did not alter the inflammatory cell recruitment into the peritoneal cavity of mice after thioglycollate exposure (Supplemental Figure S1). Moreover, flow cytometry profiles demonstrated the presence of similar proportions of SSChiFSClo F4/80+CD11b+ Ly6Clow and Ly6Chigh cells (Supplemental Figure S1). U-LPS stimulation of thioglycollate-elicited WT and p65Δmye MΦs resulted in a significant increase in IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α secretion (Figure 3A). Notably, the IL-1β and IL-6 levels derived from p65Δmye thioglycollate-elicited MΦs was significantly higher than that of WT cells (Figure 3A; 2-fold IL-1β, p < 0.05; and 4-fold IL-6, p < 0.05), whereas the levels of TNF-α were comparable between groups (Figure 3A). This was strikingly similar to the pro-inflammatory cytokine response observed in vivo after U-LPS administration to WT and p65Δmye mice (Figure 1).

Figure 3. In vitro ultra-pure LPS (U-LPS) challenge increases pro-inflammatory cytokine expression in p65Δmye peritoneal MΦs.

A, Pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α secretion; B, Il1b and caspase-1 gene expression analyzed by quantitative real-time PCR; C, Western blot of pro-IL-1β expression in unstimulated peritoneal inflammatory MΦs. D, Western blot of pro-IL-1β, IL-1β, pro-caspase-1, and caspase-1 expression of peritoneal MΦs pretreated for 6 h with 0, 10, or 100 ng/mL U-LPS (E. coli K12) followed by a 1-h stimulation with 2 mM ATP. Data represent the mean ± SEM of 2 independent experiments with n = 2–3 mice per group. Cytokine expression is normalized to the expression of the reference gene (hprt). Significant differences (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.005) between groups. N.D., not detectable.

To begin to elucidate the molecular basis of the increased IL-1β and IL-6 secretion in p65Δmye MΦs, we examined mRNA and protein levels of IL-1β and inflammasome activation (caspase-1) in WT and p65Δmye MΦs after U-LPS stimulation. We show that U-LPS and ATP stimulation of WT MΦs stimulated an increase in Il1b and caspase-1 mRNA (Figure 3B) and pro-IL-1β and cleaved IL-1β protein (Figure 3A and D). U-LPS and inflammasome activation (2 mM ATP) did not have an observable effect on pro-caspase-1 levels but appeared to increase activated caspase-1 (p10) (Figure 3D). U-LPS and ATP stimulation of p65Δmye MΦs led to comparable increase in IL1β mRNA; however, the level of induction of caspase-1 mRNA was reduced compared with WT MΦs (Figure 3B). Consistent with this observation the protein levels of pro-caspase-1 and active caspase-1 in p65Δmye were reduced in comparison to WT MΦs stimulated with U-LPS and ATP (Figure 3D). Surprisingly, the level of pro-IL-1β mRNA and protein in unstimulated p65Δmye MΦs was greater than that observed in unstimulated WT MΦs (Figure 3B and C). Furthermore, we observed increased pro-IL-1β and cleaved IL-1β after U-LPS and ATP stimulation (Figure 3A and D). These data suggest that p65Δmye inflammatory MΦs possess reduced levels of inflammasome machinery to that of WT, however steady state levels of pro-IL-1β mRNA and protein appear to be significantly elevated.

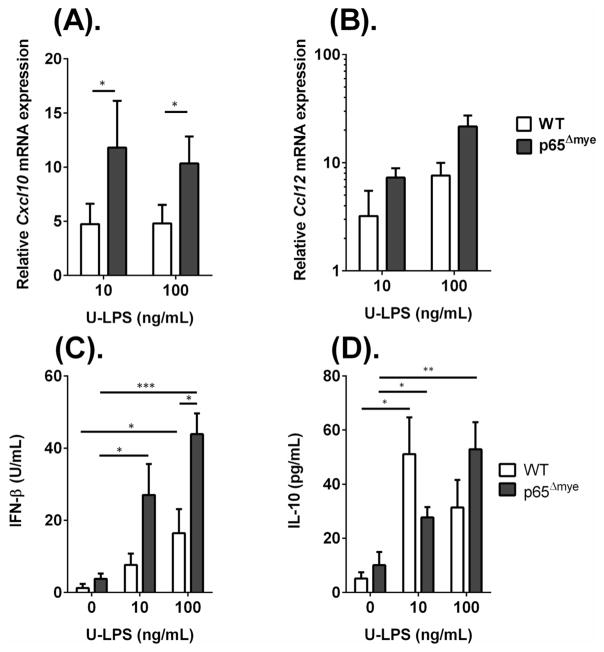

p65 deletion does not alter surface TLR4 expression, MyD88-independent TLR4 signaling, or anti-inflammatory responses in thioglycollate-elicited MΦs

Following our observation of heightened IL-1β and IL-6 cytokine production in p65Δmye peritoneal MΦs after U-LPS stimulation, we were interested in delineating the underlying molecular basis for the exaggerated p65Δmye peritoneal MΦ response. We speculated that heightened U-LPS response by thioglycollate-elicited p65Δmye peritoneal MΦs could be attributed to: 1) differential TLR expression conferring differential signaling magnitude and cytokine levels; 2) heightened activation of the TLR4-MyD88–independent pathway through IRF3; or 3) counter-inflammatory signaling that may dominate the pro-inflammatory cytokine response such that an immunosuppressive state exists in which inflammatory effects may be inadequate.

To test these possibilities, we examined for evidence of altered TLR4 expression, TLR4-MyD88-IRF3 signaling, and IL-10 responses between WT and p65Δmye peritoneal MΦs. We demonstrate that mean fluorescence intensity differences (ΔMFI) of TLR4 protein and Tlr2 and Tlr4 mRNA expression by peritoneal MΦs post thioglycollate activation between WT and p65Δmye mice were comparable between groups (Supplementary Figure S2 and results not shown). These data suggest that the increased pro-inflammatory cytokine response in p65Δmye mice cannot be explained by altered TLR4 expression by MΦs. To assess differences in the MyD88-independent signaling pathway, we examined Ccl12 and Cxcl10 mRNA fold induction in peritoneal MΦs following U-LPS stimulation (Figure 4). We show a ~10-fold increase in Cxcl10 and ~10–25-fold increase in Ccl12 mRNA following U-LPS stimulation of p65Δmye peritoneal MΦs, suggesting that MyD88-independent signaling pathway in p65Δmye MΦs remains intact (Figure 4). U-LPS-induced MΦ chemokine expression is predominantly driven by Type I IFN, IFNβ in an autocrine fashion. We show that steady state level of IFNβ mRNA and protein was not different between WT and p65Δmye peritoneal MΦs (Figure 5C and results not shown). Consistent with our observed increase chemokine production, LPS-stimulation induced an increase IFNβ production in both WT and p65Δmye peritoneal MΦs, however the level of induction in p65Δmye peritoneal MΦs was greater than that observed in WT peritoneal MΦs (Figure 4C). Finally, we show increased IL-10 secretion in both WT and p65Δmye peritoneal MΦs after U-LPS stimulation and that the level of induction was equivalent between WT and p65Δmye MΦs (Figure 4). These data indicate that the elevated inflammatory state in p65Δmye mice is not due to decreased anti-inflammatory responses.

Figure 4. MyD88-independent signaling pathway is intact in p65Δmye peritoneal MΦs following in vitro ultra pure LPS (U-LPS) challenge.

A, Fold change in (A) Cxcl10, and (B) Ccl12 gene expressions and (C), IFNβ and (D), IL-10 secretion in peritoneal MΦs pretreated for 6 hours with 0, 10 or 100 ng/mL U-LPS (E. coli K12) followed by 1 hour 2mM ATP stimulation. Data represent the mean ± SEM of 2 independent experiments with n = 2–3 mice per group. Significant differences (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.005) between groups.

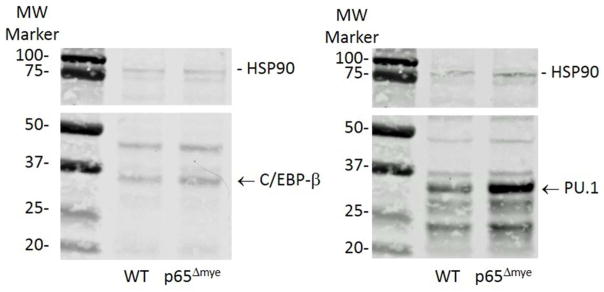

Figure 5. Western blot of c/EBPβ and PU.1 expression in thioglycollate activated WT and p65Δmye purified MΦs.

Representative western blot of c/EBPβ and PU.1 expression in thioglycollate activated WT and p65Δmye purified MΦs.

Binding of C/EBP-β and PU.1 to the 5′ promoter region of Il1b and Il6 genes is increased in p65Δmye peritoneal MΦs

It was particularly striking to us that in the absence of stimulation, the levels of Il1b mRNA and pro-IL-1β in p65Δmye MΦs were elevated compared to WT MΦs (Figure 3). To confirm this observation, we purified thioglycollate-elicited WT and p65Δmye MΦs and examined pro-IL1β levels by western blot. Indeed, pro-IL-1β was significantly increased in unstimulated, purified, thioglycollate-elicited p65Δmye MΦs compared with WT cells (Figure 3C). Given the observed elevated levels of IL-1β mRNA and protein in the unstimulated p65Δmye peritoneal MΦs in the absence of altered steady state cytokines such as IFNβ and inflammasome levels, we speculated that loss of p65 in the myeloid compartment led to altered transcriptional regulation of these cytokines. Inflammatory gene expression (Il1b and Il6) in activated myeloid cells is predominantly regulated by three transcription factors (NF-κB, C/EBP-β and PU.1). C/EBP-β directly binds to a motif in the Il6 promoter, whereas PU.1 is known to bind to the Il6 and Il1b promoters, with the latter promoter binding being via a protein-protein tether with C/EBP-β 38.

To determine whether there was altered binding of C/EBP-β and PU.1 to the Il1b and Il6 promoters, we performed ChIP-PCR analyses. Notably, the amount of binding to the 5′ promoter region of Il1b and Il6 in p65Δmye peritoneal MΦs was significantly increased with respect to a negative control binding site (Gapdh intronic region) for both C/EBP-β and PU.1, whereas there was no binding enrichment of either of the two transcription factors for the Il1b and Il6 promoters in WT peritoneal MΦs (Table 2). Importantly, the increased binding of C/EPB-β and PU.1 in p65Δmye MΦs was associated with increased Il1b and Il6 mRNA in p65Δmye peritoneal MΦs (cytokine mRNA/Hprt ratio: Il1b, 0.9 ± 0.5 vs. 1.7 ± 0.4, II6, 0.1 ± 0.1 vs. 0.5 ± 0.2; mean ± SD, WT vs. p65Δmye peritoneal MΦs; n = 2–6 per group; *p < 0.05). Notably, increased transcription factor:DNA interactions and Il1b and Il6 mRNA expression was associated with increased PU.1 and not C/EPB-β protein level as demonstrated by western blot (Figure 5).

Table 2. Binding of C/EBP-β and PU.1 on the 5′ promoter region of Il1β and Il6 in WT and p65 Δmye peritoneal MΦs.

ChIP data reveal that there is a significantly increased binding of C/EBP-β and PU.1 on Il1b and Il6 promoters in p65 Δmye peritoneal MΦs. The amount of immunoprecipitated DNA was analyzed by real-time PCR and then normalized over the respective input control.

| Transcription factor | Enrichment over negative control (Gapdh intronic region) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peritoneal MΦs | ||||

| Il1b | Il6 | |||

| WT | p65Δmye | WT | p65Δmye | |

| C/EBP-β | 1.60(n.s.) | 2.64* | 60.02(n.s.) | 266.34* |

| PU.1 | 1.41(n.s.) | 34.73* | 0 (n.s.) | 336.62* |

Data in the table represent the fold increase of immunoprecipitated DNA for Il1b or Il6 over a negative control DNA fragment (Gapdh intronic region).

p < 0.05 vs. negative control; n=2 for each group;

Il1b: interleukin 1b; Il6: interleukin 6; MΦs: macrophages; n.s.: not significant.

Discussion

In the present study, we investigated whether the NF-κB RelA/p65 subunit in myeloid cells regulates LPS-induced shock responses. We show 1) that p65Δmye mice had increased susceptibility to LPS-induced cell death and that this susceptibility was associated with an enhanced inflammatory response, as evidenced by increased pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β and IL-6); 2) LPS stimulation of “activated” (thioglycollate-elicited), but not bone marrow–derived MΦs deficient in p65 led to increased secretion of IL-1β and IL-6 and 3) that p65-deficient MΦs possess increased steady state C/EBP-β and PU.1 and Il1b mRNA and pro-IL-1β protein levels and that this was associated with heightened C/EBP-β and PU.1 binding to Il1b and Il6 promoters. These studies identify a previously undescribed transcriptional-based anti-inflammatory mechanism whereby p65 regulates the transcription factors C/EBP-β and PU.1 binding to Il1b and Il6 promoters and myeloid pro-inflammatory cytokine production.

Though it may seem unexpected and counterintuitive, there is significant evidence supporting an anti-inflammatory role for NF-κB signaling in the myeloid cell compartment and promoting a protective response against LPS-induced shock. For example, the p50 homodimer, which lacks a transactivation domain, has been shown to repress expression of NF-κB target genes and inhibit inflammation in MΦs 39. Previous studies have reported increased sensitivity of p50-deficient mice that are heterozygous for p65 (p50−/− p65+/−) to LPS-induced shock, suggesting anti-inflammatory roles of the p50 homodimer and p65:p50 heterodimers in septic shock 40. Similarly, mice deficient in IKKβ in the myeloid cell compartment were more susceptible to LPS-induced shock 41.

Endotoxin is thought to activate the LPS receptor TLR4, which is largely expressed on myeloid cells 4, leading to production of the pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α and Type I IFNβ) 5, 6, 8. These cytokines promote many of the immunopathologic features of LPS-induced shock 4, 15. IL-1β and IL-6 have both been linked to cell death and septic shock 42. IL-6 induces phosphorylation and redistribution of VE-cadherin, which leads to vascular leakage 43 and is associated with increased mortality in patients with endotoxic shock 44. IL-1β is thought to promote the shock-like state including hypotension, neutropenia and thrombocytopenia which via indirect generation cyclooxygenase products, nitric oxide and PAF and TNF-α synergism 22, 45. The importance of IL-1β in the LPS-induced shock is highlighted by the demonstration that neutralization of IL-1β activity with Anakinra (IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Rα)) completely protected against LPS-induced mortality 41. Furthermore, a randomized placebo-controlled open-label Phase II study revealed a dose-dependent improvement in 28-day mortality in individuals who received the IL-1 inhibitor IL-1Rα infusion46. LPS-induced IFNβ is thought to be the primer driver of the LPS-induced shock 47. IFNβ through paracrine and autocrine loops stimulates both MyD88-dependent and independent pathways that augment production of critical chemokines and cytokines, such as IL-6, TNF-α, IL-12, IL-1β and NO 48. IFNβ−/− and IFNαR1−/− mice are resistant to lethal endotoxemia 49, 50. We show that loss of p65 in the myeloid cell compartment does not affect “steady state” IFNβ production however increases U-LPS induced IFNβ production. These studies suggest that p65 in myeloid cells is not involved in the regulation of basal IFNβ production but may impact Type I IFN autocrine effects. Consistent with this argument we observed increased chemokine production in p65Δmye peritoneal MΦs 24h following U-LPS stimulation. Given the kinetics of the observed rapid rise in IL-1β and IL-6 in the p65Δmye myeloid cell compartment, the altered Type I IFN autocrine loop is not likely to explain the observed elevation in these cytokines.

In the present study we show that enhanced levels of pro-inflammatory cytokine appeared to be related to heightened C/EBP-β and PU.1 interactions with the Il1b and Il6 promoters in activated myeloid cells. Moreover, we observed increased binding of C/EBP-β and PU.1 with the Il1b and Il6 promoters and increased Il1b and Il6 mRNA in thioglycollate-elicited MΦs and not BMDMs following p65 deletion. PU.1 is a winged helix-turn-helix (wHTH) factor of the ETS family of proteins and is essential for the myeloid cell development 51, 52. PU.1 binds to purine-rich sequences (the PU box) on the promoter of the target genes and, in collaboration with other transcription factors (C/EBP family C/EBP-α and C/EBP-β), induces gene expression 51. In particular, the Il1b promoter is transactivated by C/EBP-β through the transcription factor PU.1, which acts as a tether in order to allow C/EBP-β to bind the DNA 38. Interestingly, a naturally occurring polymorphism in the human IL1b promoter has been identified and this SNP alters PU.1 and C/EBP-β interactions and controls IL-1β production 53.

Recent studies defining PU.1 and C/EBP family member transcriptional regulation of cell fate decisions have identified an important contribution from antagonistic and co-operative relationships between transcription factors 54. The underlying molecular processes involved in the antagonism-cooperative switch are not yet clear; however, the concentration and ratio of various transcription factors seems to be important. Studies in U937 and PUER cells have revealed that increased C/EBP-α level are sufficient to modulate PU.1-induced myeloid cell differentiation 55, 56. Similarly, G-CSF modulation of C/EBP-α and PU.1 ratio can modulate granulocyte differentiation 55. Furthermore, PU.1 has been shown to modulate T-cell and natural killer cell gene expression by dose-dependent affect 57. Interestingly, we show that increased PU.1 interaction with the IL-1β and IL-6 promoters was associated with heightened total PU.1 levels in the p65Δmye MΦs, whereas the increased binding of C/EBP-β was not associated with increased levels of total C/EBP. Thus we speculate that the dose-dependent increase in PU.1 drives Il1b expression in p65Δmye cells. One possible explanation for the increased PU.1 levels is altered expression of the microRNA miR-155. Moreover, miR-155 levels were significantly decreased in thioglycollate-elicited p65Δmye peritoneal MΦs compared with WT MΦs (miR-155/U6 ratio; 1.4 ± 0.9 vs. 0.5 ± 0.4, WT vs. p65Δmye peritoneal MΦs; mean ± SD; n = 3 per group; *p < 0.05). MiR-155 is a negative regulator of proteins involved in LPS signaling including Fas-associated death domain protein (FADD), IkappaB kinase epsilon (IKKε), and the receptor (TNF-R superfamily)-interacting serine-threonine kinase 1 (Ripk1) as well as PU.1 (Spi1) expression 58,59. Previous studies using an activated B-cell tumor cell line have revealed that NF-κB induces the upregulation of miR-155, which leads to downregulation of PU.1 protein levels and subsequently to reduced expression of PU.1-response genes 59. Indeed, an NF-κB p50/p65-responsive site has been identified in the human MIR155HG promoter 60.

Previously Greten and colleagues demonstrated enhanced IL-1β secretion and increased susceptibility to endotoxin-induced shock in the IkkbΔmye mice; however the enhanced IL-1β production was attributed to altered NF-kB-mediated signaling pathways 41. Moreover, the authors observed that loss of Ikkβ and NF-kB signaling was associated with the loss in NF-κB-mediated negative regulation of caspase-1–dependent IL-1β processing and secretion 41. We observed increased levels of pro-IL-1βmRNA and protein in p65Δmye inflammatory MΦs, however the increased cytokine level was in the presence of reduced levels of inflammasome machinery. Importantly, the level of caspase-1 activity was sufficient to provide inflammasome activity to drive increased IL-1β cleavage and secretion. The observation of decreased levels of caspase-1 and increased IL-1β secretion in p65Δmye inflammatory MΦs further supports the concept of existence of additional pathways involved in altered IL-1β levels in myeloid cells following loss of Ikkβ and NF-kB signaling independent of the negative regulation of inflammasome–dependent IL-1β processing and secretion. Our studies identified an alternative pathway whereby p65/NF-kB regulates IL-1β mRNA expression via transcriptional mechanism involving increased PU.1 and C/EBP-β interaction with the IL-1β and IL-6 promoters. There is emerging evidence of IKK-mediated signaling independent of NF-κB signaling, including regulation of MAPK pathways and TLR-induced IRF-5 signaling 61, 62..

One limitation of these analyses is that deletion of p65 in myeloid cells using the LysM-Cre system leads to deletion of p65 in common myeloid progenitor–derived cells, i.e. MΦs, neutrophils, and DCs. Therefore, we cannot exclude the contribution of p65 signaling in neutrophils and DCs to the increased sera pro-inflammatory cytokines and mortality in vivo. Previous studies in LysMCreIKKβ mice revealed increased IL-1β release in both MΦs and neutrophils after endotoxin challenge 41. However, MΦs were the major source of IL-1β under these conditions; IKKβ-deficient MΦs secrete 7–10 fold more IL-1β per cell after LPS stimulation than IKKβ-deficient neutrophils under the same conditions, and pharmacologic ablation of MΦs (Clondoranate) substantially decreases plasma IL-1β and improves endotoxic shock 41. Consistent with this, we have demonstrated that IL-1β and IL-6 were elevated in serum and in p65Δmye peritoneal MΦs after U-LPS stimulation, indicating that MΦs and the cytokines that they produce are likely the factors contributing to endotoxic shock–induced death in p65Δmye mice.

In conclusion, our study shows that myeloid deletion of p65 aggravates LPS-induced shock via augmenting IL-1β and IL-6 production by LPS-stimulated MΦs via enhanced steady-state C/EBP-β and PU.1 interactions with the IL-1β and IL-6 promoters. Our findings highlight a previously undescribed role for p65 in the negative regulation of myeloid cell-derived pro-inflammatory cytokine production and LPS-induced shock and raise cautionary awareness with respect to the potential of employing NFκB inhibitors for therapy of amplification of immune processes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Grant support: This work was supported by NIH DK090119, AI112626 and The Crohn’s Colitis Foundation of America (S.P.H).

We thank Dr Joseph Qualls and members of the Division of Allergy and Immunology and Immunobiology, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center for critical review of the manuscript and insightful conversations. This work was supported by NIH R01 AI073553, R01 DK090119, P30DK078392 (S.P.H.); U19A1070235, Crohn’s Colitis Foundation of America and Food Allergy Research Education Award. We would also like to thank Shawna Hottinger for editorial assistance and manuscript preparation.

Abbreviations

- BMDM

bone marrow–derived macrophage

- CCHMC

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center

- cEBPβ

CCAAT/Enhancer Binding Protein Beta

- IACUC

Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee

- IFN

interferon

- NF-κB

nuclear factor kappa Beta

- IκB

inhibitor of kappa B

- IKK

activation of IκB kinase

- IL

interleukin

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- TLR

toll-like receptor

- MyD88

myeloid differentiation factor 88

- LysM

lysozyme M

- MΦ

macrophage

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

- WT

wild-type

Footnotes

Disclosures: The other authors have declared that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Pinner RW, Teutsch SM, Simonsen L, et al. Trends in infectious diseases mortality in the United States. Jama. 1996;275:189–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neu HC. Infections due to gram-negative bacteria: an overview. Rev Infect Dis. 1985;7(Suppl 4):S778–82. doi: 10.1093/clinids/7.supplement_4.s778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Riedemann NC, Guo RF, Ward PA. Novel strategies for the treatment of sepsis. Nat Med. 2003;9:517–24. doi: 10.1038/nm0503-517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen J. The immunopathogenesis of sepsis. Nature. 2002;420:885–91. doi: 10.1038/nature01326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonizzi G, Karin M. The two NF-kappaB activation pathways and their role in innate and adaptive immunity. Trends Immunol. 2004;25:280–8. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2004.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kawai T, Akira S. Signaling to NF-kappaB by Toll-like receptors. Trends Mol Med. 2007;13:460–9. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kopp EB, Ghosh S. NF-kappa B and rel proteins in innate immunity. Adv Immunol. 1995;58:1–27. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60618-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karin M. NF-kappaB as a critical link between inflammation and cancer. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2009;1:a000141. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ghosh S, Karin M. Missing pieces in the NF-kappaB puzzle. Cell. 2002;109(Suppl):S81–96. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00703-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu SF, Malik AB. NF-kappa B activation as a pathological mechanism of septic shock and inflammation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;290:L622–L45. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00477.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bohrer H, Qiu F, Zimmermann T, et al. Role of NFkappaB in the mortality of sepsis. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:972–85. doi: 10.1172/JCI119648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arnalich F, Garcia-Palomero E, Lopez J, et al. Predictive value of nuclear factor kappaB activity and plasma cytokine levels in patients with sepsis. Infect Immun. 2000;68:1942–5. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.4.1942-1945.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Altavilla D, Squadrito G, Minutoli L, et al. Inhibition of nuclear factor-kappaB activation by IRFI 042, protects against endotoxin-induced shock. Cardiovasc Res. 2002;54:684–93. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00276-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ikezoe T, Yang Y, Heber D, Taguchi H, Koeffler HP. PC-SPES: a potent inhibitor of nuclear factor-kappa B rescues mice from lipopolysaccharide-induced septic shock. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;64:1521–9. doi: 10.1124/mol.64.6.1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dinarello CA. Pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines as mediators in the pathogenesis of septic shock. Chest. 1997;112:S321–S9. doi: 10.1378/chest.112.6_supplement.321s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Endo S, Inada K, Inoue Y, et al. Two types of septic shock classified by the plasma levels of cytokines and endotoxin. Circ Shock. 1992;38:264–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Calandra T, Gerain J, Heumann D, Baumgartner JD, Glauser MP. High circulating levels of interleukin-6 in patients with septic shock: evolution during sepsis, prognostic value, and interplay with other cytokines. The Swiss-Dutch J5 Immunoglobulin Study Group. Am J Med. 1991;91:23–9. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(91)90069-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Casey LC, Balk RA, Bone RC. Plasma cytokine and endotoxin levels correlate with survival in patients with the sepsis syndrome. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:771–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-8-199310150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Copeland S, Warren HS, Lowry SF, Calvano SE, Remick D. Acute inflammatory response to endotoxin in mice and humans. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2005;12:60–7. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.12.1.60-67.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bauss F, Droge W, Mannel DN. Tumor necrosis factor mediates endotoxic effects in mice. Infect Immun. 1987;55:1622–5. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.7.1622-1625.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Everaerdt B, Brouckaert P, Shaw A, Fiers W. Four different interleukin-1 species sensitize to the lethal action of tumour necrosis factor. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989;163:378–85. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(89)92146-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okusawa S, Gelfand JA, Ikejima T, Connolly RJ, Dinarello CA. Interleukin 1 induces a shock-like state in rabbits. Synergism with tumor necrosis factor and the effect of cyclooxygenase inhibition. J Clin Invest. 1988;81:1162–72. doi: 10.1172/JCI113431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Waage A, Espevik T. Interleukin 1 potentiates the lethal effect of tumor necrosis factor alpha/cachectin in mice. J Exp Med. 1988;167:1987–92. doi: 10.1084/jem.167.6.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith JW, 2nd, Urba WJ, Curti BD, et al. The toxic and hematologic effects of interleukin-1 alpha administered in a phase I trial to patients with advanced malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 1992;10:1141–52. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1992.10.7.1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crown J, Jakubowski A, Kemeny N, et al. A phase I trial of recombinant human interleukin-1 beta alone and in combination with myelosuppressive doses of 5-fluorouracil in patients with gastrointestinal cancer. Blood. 1991;78:1420–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chapman PB, Lester TJ, Casper ES, et al. Clinical pharmacology of recombinant human tumor necrosis factor in patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 1987;5:1942–51. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1987.5.12.1942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kozak W, Kluger MJ, Soszynski D, et al. IL-6 and IL-1 beta in fever. Studies using cytokine-deficient (knockout) mice. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;856:33–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb08310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leon LR, White AA, Kluger MJ. Role of IL-6 and TNF in thermoregulation and survival during sepsis in mice. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:R269–77. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.275.1.R269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sharif O, Bolshakov VN, Raines S, Newham P, Perkins ND. Transcriptional profiling of the LPS induced NF-kappaB response in macrophages. BMC Immunol. 2007;8:1. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-8-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Freudenberg MA, Keppler D, Galanos C. Requirement for lipopolysaccharide-responsive macrophages in galactosamine-induced sensitization to endotoxin. Infect Immun. 1986;51:891–5. doi: 10.1128/iai.51.3.891-895.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beg AA, Sha WC, Bronson RT, Ghosh S, Baltimore D. Embryonic lethality and liver degeneration in mice lacking the RelA component of NF-kappa B. Nature. 1995;376:167–70. doi: 10.1038/376167a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Waddell A, Ahrens R, Tsai YT, et al. Intestinal CCL11 and eosinophilic inflammation is regulated by myeloid cell-specific RelA/p65 in mice. J Immunol. 2013;190:4773–85. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hoover DL, Nacy CA. Macrophage activation to kill Leishmania Tropica: Defective intracellular killing of amastigotes by macrophages elicited with sterile inflammatory agents. J Immunol. 1984;132:1487–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hoebe K, Du X, Georgel P, et al. Identification of Lps2 as a key transducer of MyD88-independent TIR signalling. Nature. 2003;424:743–8. doi: 10.1038/nature01889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O’Riordain MG, Collins KH, Pilz M, Saporoschetz IB, Mannick JA, Rodrick ML. Modulation of macrophage hyperactivity improves survival in a burn-sepsis model. Arch Surg. 1992;127:152–7. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1992.01420020034005. discussion 7–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang C, Yu X, Cao Q, et al. Characterization of murine macrophages from bone marrow, spleen and peritoneum. BMC Immunol. 2013;14:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-14-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gordon S, Taylor PR. Monocyte and macrophage heterogeneity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:953–64. doi: 10.1038/nri1733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang Z, Wara-Aswapati N, Chen C, Tsukada J, Auron PE. NF-IL6 (C/EBPbeta) vigorously activates il1b gene expression via a Spi-1 (PU.1) protein-protein tether. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:21272–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000145200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bohuslav J, Kravchenko VV, Parry GC, et al. Regulation of an essential innate immune response by the p50 subunit of NF-kappaB. J Clin Invest. 1998;102:1645–52. doi: 10.1172/JCI3877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gadjeva M, Tomczak MF, Zhang M, et al. A role for NF-kappa B subunits p50 and p65 in the inhibition of lipopolysaccharide-induced shock. J Immunol. 2004;173:5786–93. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.9.5786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Greten FR, Arkan MC, Bollrath J, et al. NF-kappaB is a negative regulator of IL-1beta secretion as revealed by genetic and pharmacological inhibition of IKKbeta. Cell. 2007;130:918–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dinarello CA. The role of interleukin-1 in host responses to infectious diseases. Infect Agents Dis. 1992;1:227–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lo CW, Chen MW, Hsiao M, et al. IL-6 trans-signaling in formation and progression of malignant ascites in ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2011;71:424–34. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Damas P, Ledoux D, Nys M, et al. Cytokine serum level during severe sepsis in human IL-6 as a marker of severity. Ann Surg. 1992;215:356–62. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199204000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Beasley D, Schwartz JH, Brenner BM. Interleukin 1 induces prolonged L-arginine-dependent cyclic guanosine monophosphate and nitrite production in rat vascular smooth muscle cells. J Clin Invest. 1991;87:602–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI115036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fisher CJ, Jr, Dhainaut JF, Opal SM, et al. Recombinant human interleukin 1 receptor antagonist in the treatment of patients with sepsis syndrome. Results from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Phase III rhIL-1ra Sepsis Syndrome Study Group. JAMA. 1994;271:1836–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mahieu T, Libert C. Should we inhibit Type I interferons in Sepsis? Infection and Immunity. 2007;75:22–9. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00829-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hungness ES, Pritts TA, Luo GJ, Sun X, Penner CG, Hasselgren PO. The transcription factor activator protein-1 is activated and interleukin-6 production is increased in interleukin-1beta-stimulated human enterocytes. Shock. 2000;14:386–91. doi: 10.1097/00024382-200014030-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vadiveloo PK, Vairo G, Hertzog P, Kola I, Hamilton JA. Role of type I interferons during macrophage activation by lipopolysaccharide. Cytokine. 2000;12:1639–46. doi: 10.1006/cyto.2000.0766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Karaghiosoff M, Steinborn R, Kovarik P, et al. Central role for type I interferons and Tyk2 in lipopolysaccharide-induced endotoxin shock. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:471–7. doi: 10.1038/ni910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Laiosa CV, Stadtfeld M, Graf T. Determinants of lymphoid-myeloid lineage diversification. Annu Rev Immunol. 2006;24:705–38. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.24.021605.090742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Laiosa CV, Stadtfeld M, Xie H, de Andres-Aguayo L, Graf T. Reprogramming of committed T cell progenitors to macrophages and dendritic cells by C/EBP alpha and PU.1 transcription factors. Immunity. 2006;25:731–44. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang G, Zhou B, Li S, et al. Allele-specific induction of IL-1beta expression by C/EBPbeta and PU.1 contributes to increased tuberculosis susceptibility. PLoS Pathog. 2014;10:e1004426. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Walsh JC, DeKoter RP, Lee HJ, et al. Cooperative and antagonistic interplay between PU.1 and GATA-2 in the specification of myeloid cell fates. Immunity. 2002;17:665–76. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(02)00452-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dahl R, Walsh JC, Lancki D, et al. Regulation of macrophage and neutrophil cell fates by the PU.1:C/EBPalpha ratio and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:1029–36. doi: 10.1038/ni973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Radomska HS, Huettner CS, Zhang P, Cheng T, Scadden DT, Tenen DG. CCAAT/enhancer binding protein alpha is a regulatory switch sufficient for induction of granulocytic development from bipotential myeloid progenitors. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:4301–14. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.7.4301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kamath MB, Houston IB, Janovski AJ, et al. Dose-dependent repression of T-cell and natural killer cell genes by PU.1 enforces myeloid and B-cell identity. Leukemia. 2008;22:1214–25. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tili E, Michaille JJ, Cimino A, et al. Modulation of miR-155 and miR-125b levels following lipopolysaccharide/TNF-alpha stimulation and their possible roles in regulating the response to endotoxin shock. J Immunol. 2007;179:5082–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.8.5082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thompson RC, Herscovitch M, Zhao I, Ford TJ, Gilmore TD. NF-kappaB down-regulates expression of the B-lymphoma marker CD10 through a miR-155/PU.1 pathway. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:1675–82. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.177063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Thompson RC, Vardinogiannis I, Gilmore TD. Identification of an NF-kappaB p50/p65-responsive site in the human MIR155HG promoter. BMC Mol Biol. 2013;14:24. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-14-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Oeckinghaus A, Hayden MS, Ghosh S. Crosstalk in NF-kappaB signaling pathways. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:695–708. doi: 10.1038/ni.2065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ren J, Chen X, Chen ZJ. IKKbeta is an IRF5 kinase that instigates inflammation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:17438–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1418516111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.