Significance

Breaking the “central dogma” of molecular biology, RNA editing is a specific posttranscriptional modification of RNA sequences. In seed plant organelle editosomes, each editable cytidine is identified by a specific pentatricopeptide repeat (PPR) protein. Some of these sequence-specific proteins contain an additional C-terminal “DYW” domain, which is supposed to carry the catalytic activity for editing. However, many PPR editing factors lack this domain. In this article, we show that a subfamily of about 60 Arabidopsis proteins might all require two additional PPR proteins for the editing of their sites. One of them, DYW2, is a specific cofactor containing a DYW domain, supporting the hypothesis that this domain might bring the cytidine deaminase activity to these editosomes.

Keywords: RNA editing, organelles, pentatricopeptide repeat

Abstract

RNA editing is converting hundreds of cytosines into uridines during organelle gene expression of land plants. The pentatricopeptide repeat (PPR) proteins are at the core of this posttranscriptional RNA modification. Even if a PPR protein defines the editing site, a DYW domain of the same or another PPR protein is believed to catalyze the deamination. To give insight into the organelle RNA editosome, we performed tandem affinity purification of the plastidial CHLOROPLAST BIOGENESIS 19 (CLB19) PPR editing factor. Two PPR proteins, dually targeted to mitochondria and chloroplasts, were identified as potential partners of CLB19. These two proteins, a P-type PPR and a member of a small PPR-DYW subfamily, were shown to interact in yeast. Insertional mutations resulted in embryo lethality that could be rescued by embryo-specific complementation. A transcriptome analysis of these complemented plants showed major editing defects in both organelles with a very high PPR type specificity, indicating that the two proteins are core members of E+-type PPR editosomes.

In vascular plant organelle RNAs, hundreds of specific cytidines are converted into uridines by the so-called RNA editing mechanism (C to U editing). This phenomenon remained very enigmatic for a long time, raising numerous questions about its purpose, its evolution, and the molecular mechanism behind its very high specificity. Even if editing finality is still a matter of debate, many components of plant editosomes and the molecular elements required for editing specificity have been described (1, 2).

The editable cytidine is identified by a pentatricopeptide repeat (PPR) protein through the recognition of 20–25 bases upstream of the cytidine (1). However, the 5′ cis-elements, defining RNA editing sites, are not conserved between sites. Each editing site is targeted by a specific PPR protein. For example, in Arabidopsis thaliana, a total of 56 PPR proteins were shown so far to be each required for the editing of one to eight specific sites (Table S1). The PPR domain is a degenerated polypeptide showing a conserved structural conformation able to bind RNA molecules when it is repeated in tandem (3–5). A code for RNA recognition by PPR proteins was proposed (6–10). In this code, the nucleotide recognition is achieved by the combination of three amino acids of each PPR motif.

Table S1.

Known editing PPR proteins and corresponding sites

| Chromosome | Genomic position | Site name | Associated PPR | Subfamily | References |

| Plastid | 2931 | matK_2931 | QED1 | DYW | (24) |

| Plastid | 12707 | atpF_12707 | AEF1 = MPR25 | E+ | (24) |

| Plastid | 21806 | rpoC1_21806 | DOT4 | DYW | (24) |

| Plastid | 23898 | rpoB_23898 | QED1 | DYW | (24) |

| Plastid | 25779 | rpoB_25779 | CRR22 | DYW | (24) |

| Plastid | 25992 | rpoB_25992 | YS1 | DYW | (24) |

| Plastid | 35800 | psbZ_35800 | OTP84 | DYW | (24) |

| Plastid | 37161 | rps14_37161 | OTP86 | DYW | (24) |

| Plastid | 57868 | accD_57868 | RARE1 | DYW | (24) |

| Plastid | 58642 | accD_58642 | QED1/PDM1 = SEL1 | DYW/PLS | (24) |

| Plastid | 63985 | psbF_63985 | LPA66 | DYW | (24) |

| Plastid | 64109 | psbE_64109 | CREF3 | DYW | (24) |

| Plastid | 69553 | rps12_69553 | OTP81/QED1 | DYW/DYW | (24) |

| Plastid | 69942 | clpP_69942 | CLB19 | E+ | (24) |

| Plastid | 78691 | rpoA_78691 | CLB19 | E+ | (24) |

| Plastid | 86055 | rpl23_86055 | OTP80 | E+ | (24) |

| Plastid | 94999 | ndhB_94999 | OTP84 | DYW | (24) |

| Plastid | 95225 | ndhB_95225 | CREF7 | DYW | (24) |

| Plastid | 95608 | ndhB_95608 | QED1 | DYW | (24) |

| Plastid | 95644 | ndhB_95644 | OTP82 | DYW | (24) |

| Plastid | 95650 | ndhB_95650 | ELI1 | DYW | (24) |

| Plastid | 96419 | ndhB_96419 | CRR22 | DYW | (24) |

| Plastid | 96698 | ndhB_96698 | CRR28 | DYW | (24) |

| Plastid | 112349 | ndhF_112349 | OTP84 | DYW | (24) |

| Plastid | 116281 | ndhD_116281 | CRR22 | DYW | (24) |

| Plastid | 116290 | ndhD_116290 | CRR28 | DYW | (24) |

| Plastid | 116494 | ndhD_116494 | OTP85 | DYW | (24) |

| Plastid | 116785 | ndhD_116785 | CRR21 | E+ | (24) |

| Plastid | 117166 | ndhD_117166 | CRR4 | E | (24) |

| Plastid | 118858 | ndhG_118858 | OTP82 | DYW | (24) |

| Mitochondrion | 20665 | nad5c_1916 | MEF13 | E+ | (21) |

| Mitochondrion | 21890 | nad5c_1665 | MEF13 | E+ | (21) |

| Mitochondrion | 21975 | nad5c_1580 | AEF1 = MPR25 | E+ | (32) |

| Mitochondrion | 22005 | nad5c_1550 | MEF29 = PPR2263 | DYW | (21) |

| Mitochondrion | 23908 | nad9_328 | SLO1 | E+ | (32) |

| Mitochondrion | 25176 | rpl16_440 | OTP72 | E+ | (32) |

| Mitochondrion | 25407 | rpl16_209 | MEF35 | DYW | (76) |

| Mitochondrion | 25619 | rps3_1534 | REME2 | DYW | (77) |

| Mitochondrion | 30490 | ccmB_28 | MEF7 | DYW | (32) |

| Mitochondrion | 30890 | ccmB_428 | CWM1 | E+ | (78) |

| Mitochondrion | 31028 | ccmB_566 | MEF19 | E | (21) |

| Mitochondrion | 31031 | ccmB_569 | MEF32 | E | (8) |

| Mitochondrion | 41931 | cox2_698 | COD1 | E+ | (79) |

| Mitochondrion | 42376 | cox2_253 | COD1 | E+ | (79) |

| Mitochondrion | 42602 | cox2_27 | MEF32 | E | (8) |

| Mitochondrion | 53197 | ccmFc_415 | MEF13 | E+ | (21) |

| Mitochondrion | 53562 | ccmFc_50 | MEF13 | E+ | (21) |

| Mitochondrion | 60520 | cob_286 | MEF35 | DYW | (76) |

| Mitochondrion | 60559 | cob_325 | MEF7 | DYW | (32) |

| Mitochondrion | 61142 | cob_908 | MEF29 = PPR2263 | DYW | (21) |

| Mitochondrion | 77157 | nad6_103 | GRS1 | E+ | (80) |

| Mitochondrion | 77165 | nad6_95 | MEF8/MEF8S | DYW | (21) |

| Mitochondrion | 79760 | nad2_558 | REME1 | DYW | (32) |

| Mitochondrion | 81239 | nad2_59 | MEF13 | E+ | (21) |

| Mitochondrion | 82161 | rps4_956 | MEF1 | DYW | (21) |

| Mitochondrion | 82740 | rps4_377 | GRS1 | E+ | (80) |

| Mitochondrion | 82891 | rps4_226 | MEF20 | E | (21) |

| Mitochondrion | 82942 | rps4_175 | REME2 | DYW | (77) |

| Mitochondrion | 132094 | nad7_24 | OTP87 | E | (32) |

| Mitochondrion | 133233 | nad7_200 | MEF9 | E | (21) |

| Mitochondrion | 134309 | nad7_213 | MEF13 | E+ | (21) |

| Mitochondrion | 135888 | nad7_739 | SLO2 | E+ | (32) |

| Mitochondrion | 137931 | nad7_963 | MEF1 | DYW | (21) |

| Mitochondrion | 141494 | nad5_676 | MEF8/MEF8S | DYW | (21) |

| Mitochondrion | 141572 | nad5_598 | CWM1 | E+ | (78) |

| Mitochondrion | 141796 | nad5_374 | MEF12 | E+ | (81) |

| Mitochondrion | 143260 | nad1c_937 | PPME | P | (46) |

| Mitochondrion | 143299 | nad1c_898 | PPME | P | (46) |

| Mitochondrion | 144418 | matR_1895 | MEF14 | DYW | (21) |

| Mitochondrion | 144583 | matR_1730 | MEF11 | DYW | (21) |

| Mitochondrion | 157634 | mttB_144 | SLO2 | E+ | (32) |

| Mitochondrion | 157635 | mttB_145 | SLO2 | E+ | (32) |

| Mitochondrion | 158156 | mttb_666 | SLO2 | E+ | (32) |

| Mitochondrion | 161816 | nad4_124 | MEF11 | DYW | (21) |

| Mitochondrion | 161850 | nad4_158 | MEF13 | E+ | (21) |

| Mitochondrion | 161858 | nad4_166 | MEF26 | DYW | (21) |

| Mitochondrion | 162068 | nad4_376 | AHG11 | E+ | (32) |

| Mitochondrion | 162141 | nad4_449 | SLO1 | E+ | (32) |

| Mitochondrion | 164059 | nad4_896 | MEF7 | DYW | (32) |

| Mitochondrion | 167277 | nad4_1033 | SLO4 | E | (82) |

| Mitochondrion | 167373 | nad4_1129 | COD1 | E+ | (79) |

| Mitochondrion | 167599 | nad4_1355 | MEF18 | E | (21) |

| Mitochondrion | 167617 | nad4_1373 | MEF35 | DYW | (76) |

| Mitochondrion | 188574 | atp4_89 | MEF3 | E | (21) |

| Mitochondrion | 189122 | nad4L_110 | SLO2 | E+ | (32) |

| Mitochondrion | 189177 | nad4L_55 | GRS1 | E+ | (80) |

| Mitochondrion | 189191 | nad4L_41 | MEF7 | DYW | (32) |

| Mitochondrion | 218536 | cox3_257 | MEF21 | E+ | (21) |

| Mitochondrion | 218590 | cox3_311 | MEF26 | DYW | (21) |

| Mitochondrion | 218593 | cox3_314 | MEF13 | E+ | (21) |

| Mitochondrion | 218701 | cox3_422 | MEF11 | DYW | (21) |

| Mitochondrion | 240191 | ccmC_568 | MEF11 | DYW | (21) |

| Mitochondrion | 240296 | ccmC_463 | CWM1 | E+ | (78) |

| Mitochondrion | 257133 | ccmFn2_344 | MEF11 | DYW | (21) |

| Mitochondrion | 257301 | ccmFn2_176 | OTP71 | E | (32) |

| Mitochondrion | 260757 | nad3_250 | SLG1 | E+ | (32) |

| Mitochondrion | 260858 | nad3_149 | MEF22 | DYW | (21) |

| Mitochondrion | 288006 | nad1b_571 | MEF32 | E | (8) |

| Mitochondrion | 302512 | atp1_1178 | OTP87 | E | (32) |

| Mitochondrion | 318083 | nad1_308 | MEF25 | E+ | (83) |

| Mitochondrion | 318126 | nad1_265 | GRS1 | E+ | (80) |

| Mitochondrion | 327957 | nad2b_1433 | MEF7 | DYW | (32) |

| Mitochondrion | 329886 | nad2b_1160 | MEF1 | DYW | (21) |

| Mitochondrion | 330204 | nad2b_842 | MEF10 | DYW | (21) |

Shown is a list of the characterized editing PPR proteins and their corresponding sites. Only sites where the edition is completely abolished in the corresponding PPR mutant are shown.

The nature of the PPR domains within proteins is used to divide the PPR family into two subfamilies, the PPR-P and the PPR-PLS. This last subfamily is subdivided in subgroups according to their E1, E2, E+, and DYW C-terminal domains (11, 12). Most members of the P-type PPR subfamily have been implicated in RNA metabolism such as 5′ or 3′ transcript stabilization and processing, splicing, and translation (5), whereas most editing PPR proteins belong to the PLS subfamily (1). Although a function in selecting editing sites is well defined for their PPR domains, the functions of the E1, E2, E+, and DYW domains remain unclear and controversial. Molecular and phylogenetic evidences suggest that the DYW domain is required for the editing activity (13, 14). Despite the lack of definitive biochemical evidence, it has been hypothesized that it could contain the RNA editing enzymatic activity required for the deamination of cytidines into uridines (13–16). However, some editing PPRs do not carry any DYW domain and end with either an E1, E2, or E+ domain (1). Moreover, the DYW domain could be deleted in some PPR-DYW proteins without affecting their function in editing (17). To reconcile the different pieces of evidence, it has been proposed that the cytidine deaminase activity could be provided either in cis by a PPR-DYW specificity factor or in trans when a PPR-E factor is required for the site recognition. This was shown, for example, for the editing of the chloroplastic ndhD-1 site, where the target site is recognized by CRR4, a PPR-E specificity factor, whereas a DYW domain is provided by DYW1, a small protein containing only a DYW domain (18).

Besides PPR proteins, numerous additional proteins were shown to be required for the same editing events, suggesting the existence of high molecular mass editosome protein complexes (2). In particular, three classes of essential non-PPR components of the editosomes were shown to be involved in C to U RNA editing. These proteins are members of small families and are suspected to have partially redundant functions as general factors involved in the editing of organelle transcripts (2). In Arabidopsis, nine Multiple Organellar RNA editing Factors (MORF/RIPs) were described as required for many editing sites of plant organelles (19–21). Members of the ORRM family and the CP31 protein, containing RNA Recognition Motifs (RRMs), were also found to influence RNA editing in plant organelles (22, 23). More recently, OZ proteins were found to copurify with components of the editosomes and also be required for organellar editing (24).

Although extensive studies of plant editosomes have already identified many factors, further studies are needed to discover new components as well as their relations in the protein network. Here, we implemented a tandem affinity purification (TAP) approach to gain insight into the composition of a chloroplast editing complex. We use the known chloroplast editing factor CHLOROPLAST BIOGENESIS 19 (CLB19) required for rpoA and clpP editing (25) as bait for purification. Two unknown PPR proteins, dually targeted to mitochondria and chloroplasts and required for Arabidopsis embryo development, were identified in the CLB19 editing complex. A transcriptome analysis of the mutants showed major editing defects in both organelles with a very high PPR-type specificity indicating that the two proteins are core members of E+-type PPR editosomes.

Results

Exploring the CLB19 Chloroplast Editing Complex.

To improve our knowledge of the in vivo composition of an RNA editing complex of land plant chloroplasts, a TAP approach was performed using the previously characterized chloroplast editing factor CLB19 as bait. CLB19 was fused to a G protein and a streptavidin-binding peptide (GS) tag at its C terminus (26, 27) and was expressed under the control of the cauliflower mosaic virus (CaMV) 35S promoter (Fig. S1A). In clb19-1 mutant plants, the CLB19-TAP tag protein was able to complement the macroscopic phenotype of the mutant (Fig. S1 B and C), indicating that the fusion protein was functionally similar to the wild-type protein. After production in Arabidopsis cell suspension culture PSB-L, two proteins were copurified with CLB19-GS in four independent experiments (Table 1 and Dataset S1). The fourth sample was subjected to RNase treatment before purification without any modification of the proteins identified in the complex (Dataset S1). Both identified proteins, AT3G49240 and AT2G15690, are members of the PPR family. According to the PPR classification, AT3G49240 belongs to the P-type PPR subfamily. This protein was recently shown to be encoded by a maternal imprinted gene named NUWA (28). AT2G15690 belongs to the PPR-DYW subfamily and was named DYW2 (detailed in DYW2 and NUWA Are Two Distant PPR Proteins).

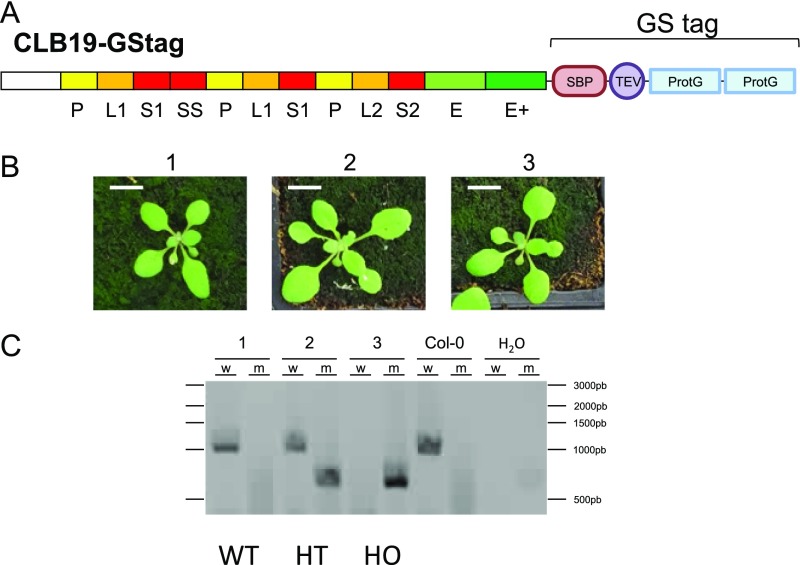

Fig. S1.

Complementation of the clb19 mutant with a TAP-tagged CLB19 construct. (A) Schematic structure of the CLB19-GS protein fusion. Predicted S (red), L (orange), P (yellow), E1 (pale green), and E+ (dark green) domains are labeled on the protein sequence. SBP, strepavidin-binding peptide; TEV, TEV protease site; ProtG, G protein. (B) Phenotype of CLB19-GS–expressing plants. (Scale bar, 1 cm.) (C) Genotype of plants. Plant numbers corresponding to B are indicated. Col-0, genomic DNA from Columbia-0; H2O, negative control; m, PCR with primers specific of T-DNA insertion allele; w, PCR with primers specific of wild-type allele. Deduced genotypes are indicated below the gel: WT (wild-type), HT (heterozygous), and HO (homozygous) for the T-DNA insertion.

Table 1.

Proteins purified by TAP using CLB19 as bait in Arabidopsis cell suspension culture PSB-L

| AGI* | Name† | Prot. mass, KDa | Loc.‡ | No. identified in four TAPs§ |

| AT1G05750 | CLB19 | 56.4 | C (26) | 4 |

| AT2G15690 | DYW2 | 66.3 | M/C (42) | 4 |

| AT3G49240 | NUWA | 71.7 | M/C (34) | 4 |

Arabidopsis genome initiative annotation identifier in TAIR database version 9.

CLB19, ChLoroplast Biogenesis 19.

Loc., subcellular localization of proteins.

See Dataset S1 for mass spectrometry analysis details.

To identify proteins interacting with CLB19, NUWA, and DYW2, we screened these three PPR proteins against a library of more than 12,000 Arabidopsis proteins using an improved high-throughput binary interactome mapping pipeline based on yeast two-hybrid (Y2H). Among the interactions involving DYW2, we identified a direct link between NUWA and DYW2 (Fig. S2). In contrast, we did not identify any interactor of the CLB19 protein in this screen.

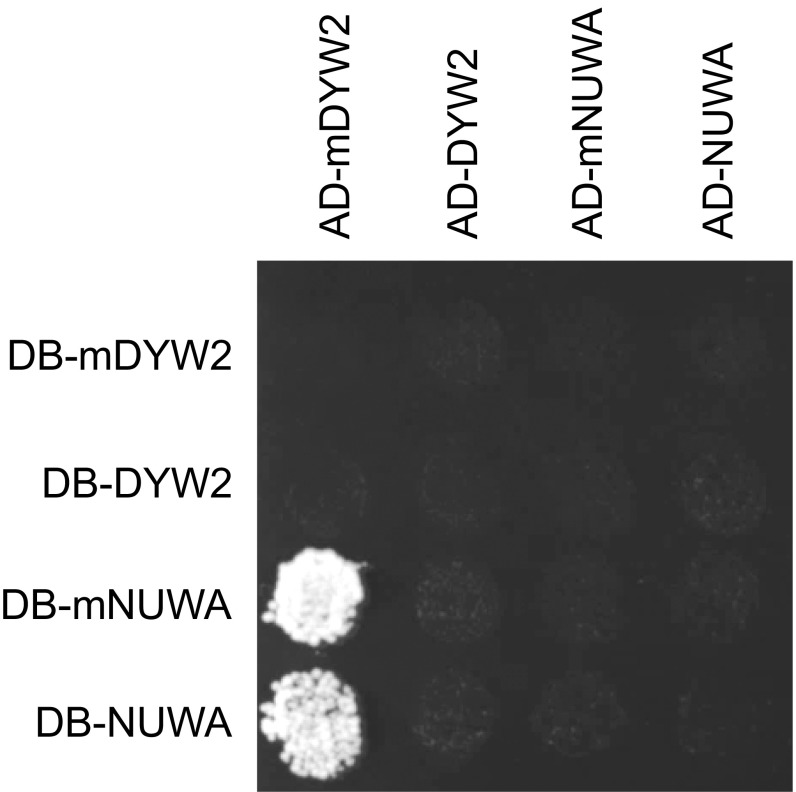

Fig. S2.

Y2H interaction of NUWA protein with cleaved DYW2. Interactions were tested using a mating-based Y2H matrix assay with AD– fusions on the horizontal axis and DNA binding domain (DB–) fusions on the vertical axis. Full-length or matured (m) DYW2 and NUWA were fused to the AD– and DB– domains. mDYW2 and mNUWA correspond to truncated proteins obtained after removal of the predicted targeting peptide. After mating, interactions were identified on –His selective medium. Among these 16 mating assays, only yeasts expressing either DB-mNUWA or DB-NUWA and AD-mDYW2 were able to grow.

DYW2 and NUWA Are Two Distant PPR Proteins.

DYW2 is an atypical PPR-DYW protein containing five predicted PPR domains and a C-terminal DYW domain separated by an amino acid sequence that do not clearly correspond to an E domain (11) (Fig. 1A). This unusual architecture of a PPR protein carrying a DYW domain without any regular E1 and E2 domains is shared by only five other proteins in the A. thaliana genome, among which is the DYW1 chloroplast editing factor (18). The other members of this small subfamily (Fig. S3), called here after the DYW1-like subfamily, are two mitochondrial editing factors, MEF8 and MEF8S (29), and two uncharacterized proteins, AT2G34370 (DYW3) and AT1G29710 (DYW4).

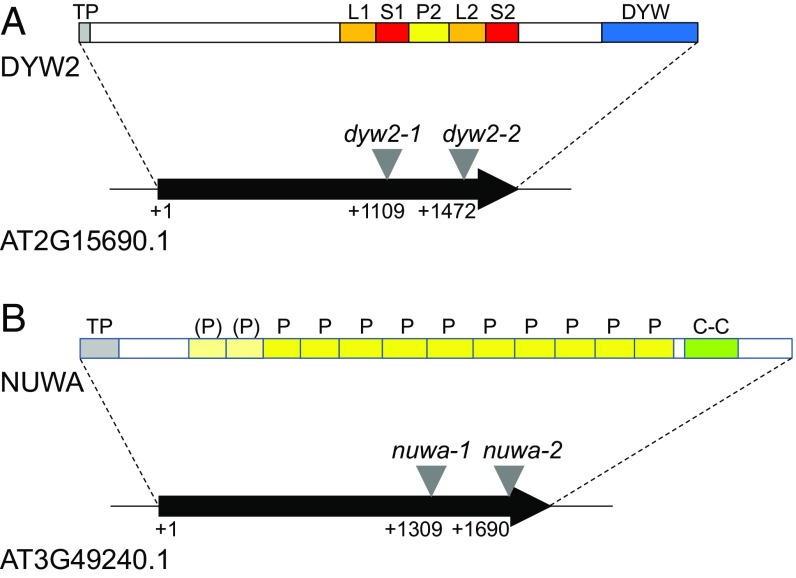

Fig. 1.

DYW2 and NUWA are members of the PPR family. (A) DYW2. (B) NUWA. Schematic structures of the loci and the proteins. Predicted targeting peptide (TP, gray box), S (red), L (orange), P (yellow), DYW (blue), and coiled-coil region (C-C, green) domains are labeled on the protein sequence. The targeting peptide was predicted using the TargetP software at www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TargetP/ for plant organisms using no cutoffs. S, L, P, and DYW domains were located according to the PPR Gene Database (11) and using the TPRpred software at https://toolkit.tuebingen.mpg.de/#/tools/tprpred [(P), light yellow]. Sequence-verified locations of the T-DNA insertions used in this study are indicated (+1 is the transcription start).

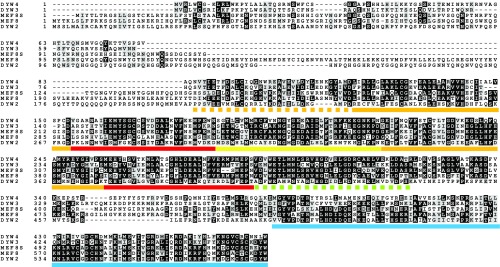

Fig. S3.

Alignment of members of the small DYW family. Predicted S (red), L (orange), P (yellow), E1 (green), and DYW (blue) domains are labeled on the protein sequence. These domains were located according to the PPR Gene Database (11). Dotted lines correspond to domains found in at least one of the members.

In silico prediction of PPR domains using the PPR Gene Database (11) and TPRpred (30) websites showed that NUWA harbors up to 12 PPR domains covering most of its amino acid sequence. As reported previously (28), a coiled-coil domain is predicted in the N-terminal region of the NUWA protein, whereas a 106-amino acid sequence without any conserved domain is present upstream of the PPR motifs (Fig. 1B). Its closest homolog in the Arabidopsis genome is GRP23, a nuclear and mitochondrial PPR (31, 32). GRP23 shares 34% amino acid identity with NUWA but does not carry any coiled coil domain (31).

NUWA and DYW2 Are Dually Targeted to Chloroplast and Mitochondria.

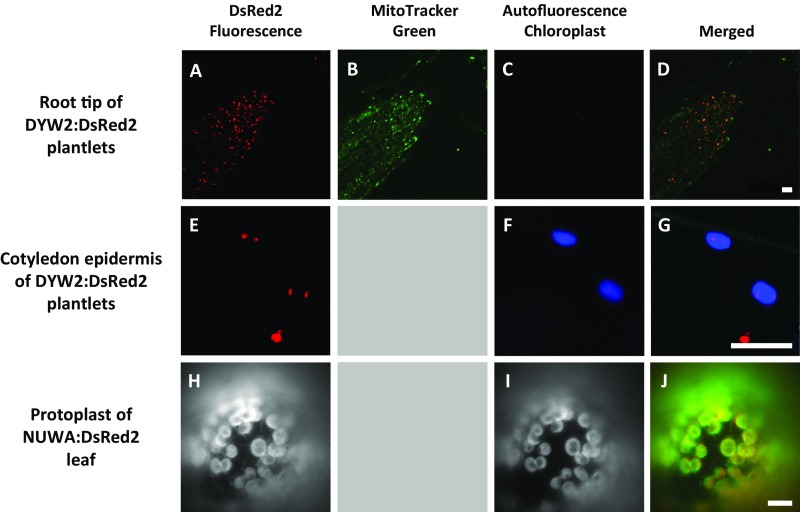

Several independent experiments previously showed that A. thaliana NUWA and DYW2 proteins, or some of their orthologs, are dually targeted to mitochondria and plastids. Whereas NUWA was recently published as localized in mitochondria (28), AT3G49240 (NUWA) was identified in several proteomic data either in A. thaliana mitochondria (33, 34) or chloroplastic samples (35, 36). In accordance with these results, we and Andrés-Colás et al. (32, 37) observed NUWA presequence and full-length fusions to fluorescent proteins in mitochondria and chloroplast (Fig. S4). The two maize orthologs of DYW2 (GRMZM2G073551 and GRMZM2G017821) were identified in plastid nucleoids (38), whereas its rice ortholog was described in mitochondria (39) samples. In A. thaliana, AT2G15690 (DYW2) was observed in both mitochondria and plastids when fused to a GFP protein (Fig. S4) (37, 40). These dual subcellular localizations were further confirmed by reverse genetic analyses and the identification of molecular phenotypes in both mitochondria and plastids of dyw2 and nuwa mutants (see DYW2 and NUWA Proteins Are Functionally Linked and Involved in Editing of Chloroplast and Mitochondria Transcripts).

Fig. S4.

Subcellular localization of DYW2 and NUWA. (A–G) Confocal images of Arabidopsis seedlings expressing 35S-DYW2:DsRed2 construct. The DsRed2 fluorophore (A and E), the MitoTracker Green staining (B), and the chlorophyll autofluorescence (C and F) were simultaneously visualized. Overlay panels (D and G) show combined fluorescence from DsRed2, MitoTracker, and chlorophyll autofluorecence. (Scale bars, 10 μm.) (H and I) Epifluorescence microscopy images of a Nicotiana benthamiana leaf protoplast expressing 35S-NUWA:DsRed2 construct. The DsRed2 fluorophore (H) and the chlorophyll autofluorescence (I) were simultaneously visualized. Overlay panel (J) shows combined fluorescence from DsREd2 and chlorophyll autofluorecence. (Scale bar, 10 μm.)

NUWA and DYW2 Proteins Are Required for Embryo Development.

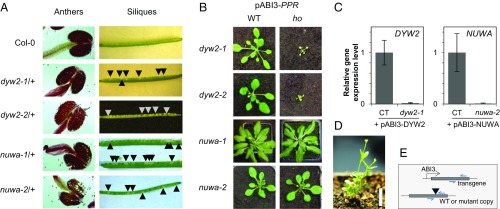

A reverse genetics approach was used to identify the molecular functions of DYW2 and NUWA proteins. Two T-DNA insertions in each gene were selected from the T-DNA Express database (41) and were named dyw2-1 (GK_332A07), dyw2-2 (FLAG_435F11), nuwa-1 (SALK_069042), and nuwa-2 (SAIL_784_A11). The position of each T-DNA was confirmed by sequencing and is indicated in Fig. 1. nuwa-1 and nuwa-2 were previously characterized as two embryo-defective alleles of the EMB1796 locus during the seedgenes project (42). Similarly, another T-DNA insertion mutant, nuwa, was recently shown to be affected in early embryogenesis and endosperm development (28). Accordingly, no homozygous seedling for nuwa-1 and nuwa-2, but also dyw2-1 and dyw2-2, insertions was found from large screens of heterozygous plant progenies, whereas aborted embryos were observed when opening siliques of heterozygous plants (Fig. 2A). Pollen viability was assayed by Alexander staining of mature anthers from heterozygous plants. Results indicated that all pollen grains were viable in both heterozygous mutants and that mutations did not affect male gametophyte viability (Fig. 2A). Finally, genetic complementation assays between, on one hand, dyw2-1 and dyw2-2 lines and, on the other hand, nuwa-1 and nuwa-2 lines confirmed that dyw2-1 and dyw2-2 and nuwa-1 and nuwa-2 are allelic mutations responsible for the observed embryo lethal phenotype (Table S2).

Fig. 2.

Characterization of dyw2 and nuwa mutants. (A) Phenotype of pollen and embryo observed on heterozygous dyw2 and nuwa plants. (Left) The viability of pollen was assayed by Alexander staining of wild-type and heterozygous plant anthers. (Right) Siliques resulting from wild-type or heterozygote self-pollination were opened 10 d after pollination. Abnormal seeds (arrows) accounted for ∼25% of the total observed. (B) Macroscopic phenotype of 1-mo-old homozygous mutant plants obtained after complementation with an embryo-specific construct. Heterozygous plants for dyw2-1 and dyw2-2 mutations were transformed with full-length DYW2 under the control of the embryo-specific pABI3 promoter, whereas heterozygous plants for nuwa-1 and nuwa-2 mutations were transformed with full-length NUWA under the control of the pABI3 promoter. Progeny seedlings of heterozygous T1 plants were genotyped to identify wild-type (Left), heterozygous (not shown), and homozygous (Right) sibling plants carrying the pABI3 embryo-specific construct. After germination on MS + hygromycin media, 10-d-old seedlings were transferred onto soil in a growth chamber with long-day conditions. (C) DYW2 and NUWA gene expression in homozygous mutant plants obtained after complementation with an embryo-specific construct. Gene expression of 1-mo-old plants grown in long-day conditions was measured by qRT-PCR using total RNA extracted from leaves of four biological replicates of dyw2-1 and nuwa-2 homozygous plants expressing the corresponding pABI3 construct and of control sibling plants. For each biological replicate, the mean expression level of three technical qRT-PCR replicates was normalized with the mean of actin2-8 expression, used as reference gene. Controls (CTs) refer to siblings of homozygous mutant plants coming from the same self-progeny, wild type or heterozygous for the mutation, and carrying the corresponding pABI3 transgene. (D) Adult phenotype of dyw2 mutant expressing pABI3-DYW2. A homozygous dyw2-2 adult plant was observed after 7 wk of culture in soil in greenhouse with short day condition (white bar, 1 cm). Flower buds were produced but did not further develop in flowers and siliques. (E) Schematic representation of the primers used for qRT-PCR in Fig. 2C. Primers are surrounding positions of T-DNA insertion. Thus, in homozygous plants expressing pABI3 construct, the expression level reflects the expression of the pABI3 construct, whereas, in CT plants, the expression level corresponds to the expression of both endogenous and transgenic genes.

Table S2.

Genetic complementation tests

| Crosses | Number of seedlings | ||

| Female | Male | Tested | Homozygotes |

| dyw2-1 | dyw2-2 | 122 | 0 |

| dyw2-2 | dyw2-1 | 69 | 0 |

| nuwa-1 | nuwa-2 | 198 | 0 |

| nuwa-2 | nuwa-1 | 105 | 0 |

Complementation of dyw2 and nuwa in Embryos and Seeds.

To bypass the embryo lethality of the mutants, we complemented them by expressing NUWA and DYW2 wild-type proteins under the control of the embryo-specific ABI3 promoter (43). After seedling development, the ABI3 promoter is expected to be no longer active, leading to its absence of expression in seedlings and at the adult stage. This strategy allowed the development of homozygous dyw2 and nuwa mutant embryos in siliques of heterozygous plants and the germination of homozygous seedlings in their progeny (Fig. 2B). The absence of expression of NUWA and DYW2 transcripts in adult plants was confirmed by qRT-PCR (Fig. 2C) and subsequently when analyzing RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) data (see dyw2-1 and nuwa-2 Complete Transcriptome Analysis). Whereas the nuwa mutants were almost indistinguishable from WT, the dyw2 mutants were small pale green plants producing sterile flowers (Fig. 2 B and D).

DYW2 and NUWA Proteins Are Functionally Linked and Involved in Editing of Chloroplast and Mitochondria Transcripts.

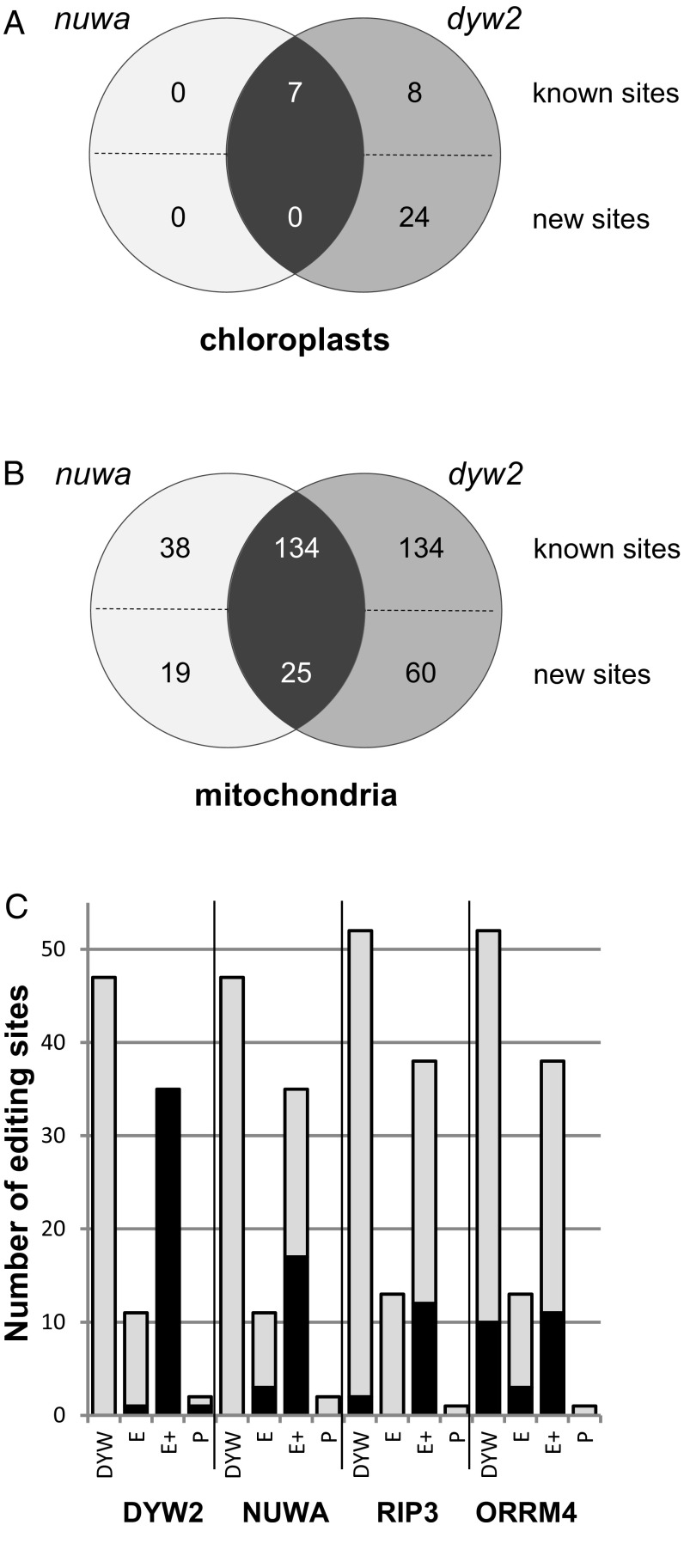

As DYW2 and NUWA are PPR proteins interacting with the editing PPR protein CLB19, we tested their involvement in editing of organelle RNA by total RNA-seq analysis of the rescued dyw2-1 and nuwa-2 mutants. The organellar editing quantification identified 392 and 223 differentially edited sites in dyw2-1 and nuwa-2, respectively (Fig. 3 A and B and Dataset S2 A and B). The differentially edited sites were either mitochondrial or chloroplastic and included previously unidentified editing sites (109 in dyw2-1 and 44 in nuwa-2). Surprisingly, one site (position 20299 of the plastid genome) was edited only in dyw2-1. Targeted Sanger sequencing of several RT-PCR products from the corresponding second allele (rescued dyw2-2 and nuwa-1) mutants showed similar results (Dataset S3), indicating that editing defects were genetically linked to mutations in either DYW2 or NUWA locus. Interestingly, dyw2-1 and nuwa-2 shared 166 differentially edited sites, a number significantly higher to what would be randomly expected (P = 0), and these common sites included the clpP and rpoA editing sites associated with CLB19. This result strongly suggests that CLB19, DYW2, and NUWA are editing partners supporting the physical interactions previously observed.

Fig. 3.

Editing activity of DYW2 and NUWA. The detailed results are provided in Dataset S2 A–D and Dataset S3. (A) Plastidial editing sites affected in dyw2 and nuwa. (B) Mitochondrial editing sites affected in dyw2 and nuwa. Venn diagrams summarizing the number of differentially edited sites in dyw2-1 and nuwa-2. The known sites correspond to the sites identified in Bentolila et al. (44), Sun et al. (24), Shi et al. (60), and Shi et al. (45). The new sites are the editing sites identified in this study. (C) DYW2 and NUWA-dependent sites are targeted by PPR-E+ proteins The PPR specificity of DYW2, NUWA, RIP3, and ORRM4 was estimated by counting the dependent (black) and independent (gray) editing sites associated with PPR of the various subfamilies [DYW, E, E+, and pure (P)]. An editing site is considered as depending on a particular protein if it is differentially edited between CT and mutant (P value < 5% after Bonferroni correction) and its editing extent is decreased by 10% or more in the mutant. It is independent otherwise. Editing sites associated with known PPRs are listed in Table S1 with their corresponding primary references. Values for RIP3 and ORRM4 were obtained by applying our statistical protocol to the raw data from Bentolila et al. (44) and Shi et al. (45), respectively. The total number of sites differs from one study to the other because of missing data from some editing sites in each study.

DYW2 and NUWA Are Required for Editing by PPR-E+.

As DYW2 and NUWA are working together with CLB19 (this work) and SLO2 (37), two PPR-E+s, we explored their association with PPR-E+ in general. Using the same criteria as Bentolila et al. (44), we considered only the editing sites depending on DYW2 or NUWA. There was a strong positive bias for sites associated with PPR-E+ proteins. Out of 47 analyzed sites associated with PPR-DYW proteins, none are depending on DYW2 or NUWA. Conversely, the 35 known PPR-E+ sites analyzed in this study are depending on DYW2 and 17 of them are depending on NUWA (Fig. 3C). Applying the same statistical analysis for RIP3 (44) (Fig. 3C and Dataset S2C) and ORRM4 (45) (Fig. 3C and Dataset S2D), two editing factors controlling numerous chloroplastic and mitochondrial sites, showed no such specificity. These results and the work of Andrés-Colás et al. (37) support an extension of the function of DYW2 and NUWA to all PPR-E+ proteins.

dyw2-1 and nuwa-2 Complete Transcriptome Analysis.

The total RNA-seq approach allowed further complete and parallel quantitative analyses of nuclear, mitochondrial, and plastidial transcriptomes. As PPR proteins of the pure subfamily such as NUWA have rarely been involved in editing (46) and to confirm that DYW2 and NUWA function primarily in RNA editing, total RNA-seq data were used to quantify organelle transcript splicing, processing, and accumulation in nuwa-2 and dyw2-1. The organelle transcriptome of dyw2-1 was highly impacted with 182 differentially expressed genes out of 239 and 21 differentially spliced introns out of 37 (Dataset S2 E–G). Noteworthily, the plastid gene expression profile of dyw2-1 was similar to the expression profile of clb19 as described by Chateigner-Boutin et al. (25), suggesting that the perturbations in the dyw2-1 transcriptome were the consequences of the numerous editing defects, especially in rpoA, which encodes a subunit of the plastid encoded RNA polymerase. On the other hand, the organelle transcriptome of nuwa-2 showed limited perturbations with only 28 differentially expressed genes and 6 differentially spliced introns, including only one that was partially impaired (Dataset S2 E, F, and H). As most of these perturbations were also found in dyw2-1 and no strong processing defect likely to explain the editing defects of nuwa-2 was detected (Dataset S2I), these results strongly suggest that both DYW2 and NUWA are genuine editing factors.

The analysis of the nuclear transcripts confirmed that no functional RNA of DYW2 or NUWA was detected in the corresponding mutants. Indeed, although reads were mapping to the genes, the mutants showed no read overlapping the T-DNA insertion sites as opposed to the controls, indicating that despite normal counts, no full-length RNA was produced in these mutants. The nuclear transcriptome analysis also showed that 12,485 genes were differentially expressed in dyw2-1 versus only 1,097 in nuwa-2, in agreement with their macroscopic phenotype (Dataset S2J). Interestingly, the analysis of the nuclear transcriptome with MapMan showed that the PPR gene family was significantly affected in both mutants (P = 0; Dataset S2K), suggesting that the organelle gene expression was impacted. In particular, NUWA was induced four times in dyw2-1, and DYW2 was induced twice in nuwa-2. Although major, these nuclear transcriptome modifications very probably reflected secondary effects of severe organelle dysfunctions as expected in mitochondria and plastid mutants because of organelle-nuclear signaling (47).

Discussion

Different RNA editing complexes have been described in several organisms, some of them having high molecular mass quaternary structures such as the 20S editosome of Trypanosoma brucei (48), for example. In contrast, it was first suggested that plant editing complexes could simply constitute one or two (PPR) proteins (18, 49, 50), similarly to the initial model of C-to-U mammal editosome where a specificity factor, ACF, binds the RNA sequence and recruits APOBEC-1, the enzyme catalyzing the reaction (51). The composition of plant RNA editosomes recently appeared to be more convoluted and heterogeneous with numerous additional proteins whose functions are still poorly understood (2). In these complexes, one or two PPR proteins of the PLS subfamily are considered to be key factors providing both the specificity and probably the enzymatic activity. Here, we show that two PPR proteins, DYW2 and NUWA, are physically and functionally part of the E+ editosomes and required for the editing activity of probably all PPR-E+ proteins.

Our results predicted that at least three different PPR proteins are at the core of each E+ editosome: a PPR-E+ specific of the target site and two common PPR proteins, DYW2 and NUWA. Whereas, in such a complex, the function of the PPR-E+ is well known as the specificity factor binding the target RNA, the molecular functions of the two other PPR proteins remain unclear. Unexpectedly for PPR proteins, reverse genetics analyses indicated that they could have numerous potential binding sites without any sequence similarity. This suggests that unlike most PPR proteins, DYW2 and NUWA may not bind to RNA or bind RNA with low sequence specificity. As proposed in the companion paper from Andrés-Colás et al. (37) and supported by our results, an interesting hypothesis is that NUWA may bridge and stabilize the interaction between PPR-E+ and DYW2 proteins. As proposed for the DYW1 protein, which brings a DYW domain to the CRR4 protein (18), it is probable that DYW2 brings the cytidine deaminase activity to the E+ editosomes. Thus, the core of any plant organelle editosome would be organized with a PPR protein targeting the editing site and a DYW domain bringing the enzymatic activity. This domain is provided in cis by the PPR specificity factor when it belongs to the PPR-DYW subfamily or could be brought in trans by a member of the DYW1-like clade when the specificity factor is a PPR-PLS, PPR-E, or PPR-E+ protein.

In addition to the severe editing defects observed in E+ sites, we also showed that dyw2 and nuwa mutants had numerous minor negative as well as positive defects in non-E+ editing sites. These results suggested that DYW2 and NUWA editosomes compete with other editosomes for unknown editing factors, supporting Sun et al.’s (2) recent review, which proposed that editosomes result from complex assembly equilibria of numerous editing factors. However, we tested the functional overlap of DYW2 and NUWA with RIP/MORFs, ORRMs, and OZ1 by comparing the lists of impacted editing sites, but none of these comparisons showed significant overlaps. Surprisingly, whereas the bait protein used in our approach, CLB19, is required for editing of two plastidial sites, which are also targets of general factors such as MORF2, MORF9, and ORRM1, we were not able to purify them together with CLB19, NUWA, and DYW2. One possible explanation of the absence of these proteins could be due to weak and/or transient interactions of these factors within the complex. Indeed, when screening the Y2H library with CLB19, NUWA, and DYW2, we were not able to identify any of these editing factors.

Besides these targeted questions regarding the molecular functions of NUWA and DYW2 PPR proteins, an intriguing observation of our study is the requirement of both of them during embryo development, whereas they are dispensable for further plant growth. Mutant studies showed that a large number of nuclear mutations impairing embryo development are associated with proteins targeted to organelles (42). Interestingly, most of these proteins are involved in the regulation of organelle gene expression, from editing to translation via splicing and processing on different RNA targets. The general consensus is that the embryo lethal phenotype of mitochondrial emb mutations is associated with a lack of energy production (52, 53), whereas the understanding of the essential role of plastid function in plant embryogenesis is still very limited. NUWA and DYW2 are required for numerous editing events in both mitochondria and plastids. The impact of these defects on embryo development is not surprising. However, further studies will be needed to understand why, in contrast, these editing defects are not lethal at the adult stage, especially in NUWA mutants that do not show any macroscopic phenotype.

Materials and Methods

Plant Material and Phenotype Characterization of T-DNA Insertion Lines.

The T-DNA insertional mutants, GK_332A07 (dwy2-1), FLAG_435F11 (dyw2-2), SALK_069042 (nuwa-1), and SAIL_784_A11 (nuwa-2), were obtained from the ABRC stock center. NUWA and DYW2 wild-type ORFs were cloned under the control of the embryo-specific pABI3 promoter using the pH7WG-ABI3 vector from Aryamanesh et al. (43). Detailed information on the plant methods used in this study is included in SI Materials and Methods. All sequences of primers used in this study are available in Table S3.

Table S3.

Sequences of primers used in this study

| Name | Sequence, 5′ to 3′ |

| Genotyping | |

| dyw2-1_LP | TCAAAATCCTCAACAAGGTGG |

| dyw2-1_RP | GCAATCGCTAACCTCTCACTG |

| dyw2-2_LP | GTTCTGTGGAAGCTTGGTGAC |

| dyw2-2_RP | ATGACGAAACATGGGTTGAAG |

| nuwa-1_LP | TGGCTGTTAAAGGTTTTGTGG |

| nuwa-1_RP | TTTAGCCATCTCCACCACATC |

| nuwa-2_LP | TGACTTGACCAGTTTGCTGTG |

| nuwa-2_RP | TAATGGGTACTGTGCTGGAGG |

| SALK_LB1.3 | ATTTTGCCGATTTCGGAAC |

| SAIL_LB3 | TAGCATCTGAATTTCATAACCAATCTCGATACAC |

| Flag_Tag5 | CTACAAATTGCCTTTTCTTATCGAC |

| Gabi_o8474 | ATAATAACGCTGCGGACATCTACATTTT |

| Cloning | |

| CLB19_STap_Tag | AAAAAGCAGGCTCCACCATGGGTCTCCTTCCCGTCGTCG |

| CLB19_ETap_Tag | AGAAAGCTGGGTCAGCATTGAGGAGATCACCAGC |

| DYW2_Start | GGAGATAGAACCATGTCTTCTCTAATGGCCATTC |

| DYW2_Stop | TCCACCTCCGGATCCCCAGTAATCCCCGCAAGAAC |

| DYW_Internal | GGAGATAGAACCATGTCTCAATTCCACTTCTCCG |

| NUWA_Start | GGAGATAGAACCATGTCGATTTCTAAAGCCGCCT |

| NUWA_ Stop | TCCACCTCCGGATCMGCAGGACGGTGGATCCTG |

| NUWA_Internal | GGAGATAGAACCATGCCGGTTAATTCATTCAACAGA |

| P35S_C_F | GCCCAGCTATCTGTCACTTTA |

| Otp100_R_center | TTCTCTCCAACAGCTTCCTCA |

| qPCR | |

| dyw2-1_qPCRF | TTGGCTTGTGCTACTGTTGG |

| dyw2-1_qPCRR | TGCTCAGCCTCAACAAGATG |

| nuwa-2_qPCRF | GGAAAGGAGGAAGAGAGGGAG |

| nuwa-2_qPCRR | ACACCACCAGCTTCGTTTTC |

| Editing | |

| RPOA_78691_F | CCACTTATGAAAGGCCAAGC |

| RPOA_78691_R | CAGGCATGAATACAGCATCG |

| NDHB_95608-96698_F | GAGGAATGTTTTTATGTGGTGCT |

| NDHB_95608-96698_R | CCGATTTGACCTATGGACGA |

| CLPP_69942_F | CGAAGTCCTGGAGAAGGAGA |

| CLPP_69942_R | TGAACCGCTACAAGATCAACA |

| RPS4_5_F | GATTTGTCCCCATTAAGATTTCA |

| RPS4_5_R | CGGCATCCCCTCTTAGTTTT |

| RPS3_3_F | TCGGGAACAACTCCTCAATC |

| RPS3_3_R | TTTCGGATATAGCACGTCTCC |

| NAD1_3_F | CTCCGTTTGATCTCCCAGAA |

| NAD1_3_R | AGGAAGCCATTGAAAGGTGA |

| NAD5_MID1_F | GGATGGGAGGGAGTAGGTCT |

| NAD5_MID1_R | AGTTAGAGATGCCGCAAGCA |

| NAD4_5_F | TTTAGCGCCCATCTTTTGAC |

| NAD4_5_R | TGTCTCGAACCCCATACTCC |

| ATP4_F | TTGTGCATTAAGTTCGAAGAAGA |

| ATP4_R | GCAAATTGCTTCCCCACTAA |

| CCMB_5_F | TACGTACGGTGGAGGTTGGT |

| CCMB_5_R | TGGGAAAACCACAGAAAACA |

| MITO043_F | CGCGAACCAAGATCCATAAT |

| MITO043_R | TTCATAATTCAGTGTGGTGGG |

Protein Interaction Methods.

The detailed methods of TAP and Y2H screening are given in SI Materials and Methods. In brief, constructions and Arabidopsis transformation were carried out as previously described (54), protein complex purification was done as described in Van Leene et al. (55), and peptide isolation and analysis were performed according to Van Leene et al. (56). Protein identification details are listed in Dataset S1.

RNA-Seq Analysis.

The detailed methods are given in SI Materials and Methods. In brief, the RNA-seq analysis was performed following the recommendations of Rigaill et al. (57). The organelle transcriptome was studied after mapping of the reads with STAR (v020201) (58) using in-house scripts adapted from the ChloroSeq package (59).

SI Materials and Methods

Plant Material, Phenotype Characterization of T-DNA Insertion Lines, and Subcellular Localizations.

The T-DNA insertional mutants GK_332A07 (dwy2-1), FLAG_435F11 (dyw2-2), SALK_069042 (nuwa-1), and SAIL_784_A11 (nuwa-2) were obtained from the ABRC stock center. Mutants were genotyped by PCR using primers specific of each mutant line, flanking the T-DNA insertion and T-DNA–specific primers to identify heterozygous or homozygous mutant plants. For phenotype characterization, seeds were sown in soil and cultivated in growth chambers under a 16 h light/8 h dark cycle at 22 °C during the day and 17 °C during night. For genetic studies, mutant surface sterilized seeds were sown on Murashige and Skoog solid medium (MS) containing 0.8% (W/V) agar–agar type E (Sigma Aldrich). Seeds were germinated in a growth chamber under long-day conditions (16 h light/8 h dark cycle, 22 °C, 45% hygrometry) after cold treatment for 48 h at 4 °C. Pollen viability was evaluated after Alexander staining (61). A purple cytoplasmic coloration indicates viability, whereas dead pollen is expected to appear in green. Subcellular localization experiments were done using the pGREENII-derived destination vector p0229-RFP2 as described in Colcombet et al. (32).

TAP.

Cloning of CLB19 C-terminal tag fusion under control of the constitutive cauliflower tobacco mosaic virus 35S promoter and transformation of Arabidopsis cell suspension culture PSB-L were carried out as previously described (54). TAP of protein complexes was done using the GS tag followed by the GS purification protocol as described in Van Leene et al. (55). For the protocols of proteolysis and peptide isolation, acquisition of mass spectra by a 4800 Proteomics Analyzer (Applied Biosystems), and MS-based protein homology identification based on the TAIR genomic database, we refer to Van Leene et al. (56). Experimental background proteins were subtracted based on ∼40 TAP experiments on wild-type cultures and cultures expressing TAP-tagged mock proteins GUS, RFP, and GFP (56). Protein identification details are listed in Dataset S1.

Y2H Screening.

CLB19, NUWA, and DYW2 full or truncated ORFs were amplified using ORF_start and ORF_stop or ORF_internal and ORF_stop primers, respectively, and cloned into the pDONR207 vector by Gateway BP reaction (Invitrogen). ORF_internal primers were designed to amplify truncated ORFs encoding mature PPR (mNUWA, mDYW2, and mCLB19) proteins lacking their putative target peptide. LR recombinations were done with the pDEST-AD-CYH2 and pDEST-DB destination vectors (62) allowing N-terminal fusions with the activation domain (AD) or the DNA binding (DB) of the GAL4 transcription factor. Y8800 MATa and Y8930 MATα yeast strains (63) were transformed with AD-PPR and DB-PPR constructs, respectively. Before Y2H screening, DB-PPR strains were shown to be unable to autoactivate the GAL1-HIS3 reporter gene in the absence of any AD-Y plasmid. AD-PPR–expressing yeasts were pooled and screened by mating against the (DB)-AtORFeome library according to the InterATOME platform pipeline adapted from the protocol described in ref. 62 with positive selection of interactions in liquid media. Yeast cultures identified as positive interactions were picked from selective media, and protein pairs were identified by depooling of AD-PPR in a targeted matricial liquid assay in which all of the AD-PPRs were individually tested against all of the positive DB proteins. Identified pairs were cherry-picked and checked by DNA sequencing. In Fig. S2, after mating of yeast expressing AD-mDYW2, AD-DYW2, AD-mNUWA, or AD-NUWA with yeast expressing DB-mDYW2, DB-DYW2, DB-mNUWA, or DB-NUWA and selection of diploids in liquid media, yeasts were spotted on selective His media containing 2% of agar.

Partial Complementation of Mutants with ABI3 Constructs.

NUWA and DYW2 wild-type ORFs in pDONR207 were subcloned into the expression vector pH7WG containing the ABI3 promoter and T35S terminator (43) using Gateway LR Clonase enzyme (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer’s instructions. dyw2-1, dyw2-2, nuwa-1, and nuwa-2 heterozygous plants were genotyped by PCR and transformed with the corresponding construct using Agrobacterium tumefaciens C58C1 (pMP90) by floral dip (64). Transformed seedlings were selected on Gamborg B5 media containing Basta or Kanamycin (depending on the original mutation-causing T-DNA insertion) and hygromycin B (to select for the complementing ABI3 construct). Selected seedlings were subsequently genotyped to identify homozygous and heterozygous plants for the original T-DNA insertion. For the RNA-seq experiments, T2 seeds collected from heterozygous dyw2/DYW2 and homozygous nuwa/nuwa T1 plants were used.

RNA Extraction, Sequencing, and Quality Controls.

Total RNA was extracted from leaves using the Nucleozol protocol (Macherey-Nagel) followed by a treatment with the DNase Max kit (Mobio). The purified RNA were then processed with the TruSeq Stranded Total RNA Library Preparation Kit with Ribo-Zero (Illumina) giving sequencing libraries with an insert size around 260 base pairs and sequenced in single-end with a read length of 75 bases on a Nextseq500 (Illumina). The raw data were deconvoluted and converted to fastq using bcl2fastq (v2.17.1.14) and then trimmed using Trimmomatic (v0.32) (65) to remove bases with Phred Quality Score < 20 and reads shorter than 30 bases. The ribosomal RNA sequences were removed after mapping with Bowtie2 (v2.2.2) (66) or STAR (v020201) (58). Using these parameters, less than 1% of raw reads were discarded.

Gene Expression Analysis.

The mapper Bowtie2 (v2.2.2) (66) was used to align reads against the A. thaliana transcriptome (with local option and other default parameters). The 33,602 genes were extracted from TAIR (v10) database corresponding to the representative gene model (longest CDS) given by TAIR. Using these parameters, 88–92% of reads were associated to a gene and 2–6% of reads with multihits were removed. After mapping and counting, the statistical analysis for differential expression was carried out separately for nuclear, chloroplastic, and mitochondrial genes so that the variations of the relative abundance of the three compartments do not bias the statistical analysis. The differentially expressed genes were identified using a likelihood ratio test for a negative binomial generalized linear model where the dispersion is estimated by the edgeR method for filtered data (v3.6.8) (67) in R (v3.1). In our model, the log of the mean expression is expressed as a linear combination of a genotype (CT or HO) effect and a batch (replicate 1–3) effect. The distribution of the resulting P values followed the quality criterion described by Rigaill et al. (57). To control the false discovery rate, adjusted P values found using the optimized FDR approach of Storey et al. (68) were calculated. We considered as being differentially expressed the genes with a q value < 0.05. The results of the statistical pipeline were further analyzed with MapMan (69) (v3.6.0RC1, mapping Ath_AGI_LOCUS_TAIR10_Aug2012). The P values of the Wilcoxon Rank Sum test were corrected with the Benjamini–Yekutieli procedure (70).

Organelle Gene Expression.

The reads were aligned to the TAIR (v10) genome with STAR (v020201) (58). The index was built using the TAIR (v10) genome and the TAIR10_GFF3_genes.gff annotation file (v2010-12-14) where the mitochondrial transsplicing events were manually curated. The reads were mapped with the alignIntronMax 5000, alignEndsType EndToEnd, and otherwise default parameters. With these parameters, more than 97% of the reads were mapped.

The organelle editing events showing on average at least one edited read per sample and 0.5% of edition in either CT or HO samples were extracted using pysamstats (v0.21) and R (v3.1). Given the large coverage difference between chloroplastic and mitochondrial sites, they were analyzed separately. For each editing site, we retrieved 2 × 2 × 3 read count corresponding to two genotypes (CT or HO), two edition status (edited or unedited), and the three biological replicates. We used Deseq2 (v1.12.3) (71) for the statistical analysis. The normalization size factors were calculated on the sum of the edited and unedited counts. The log mean count was then modeled as a linear combination of a genotype (CT or HO) effect, an edition effect (edited or unedited), and an interaction between genotype and edition. The genotype effect models the fact that expression might be different between CT and HO samples irrespective of edition. The editing effect models the fact that we do not expect edited and unedited RNA to be in equal quantity irrespective of the genotype. The interaction is our parameter of interest and models the fact that the ratio of edition might be different between CT and HO samples. A likelihood ratio test identified the editing sites for which the editing effect depended on the genotype effect. The distribution of the resulting P values followed the quality criterion described by Rigaill et al. (57). To control the false discovery rate for both mitochondrial and chloroplastic sites, the P values were adjusted using the Bonferroni procedure (72) including all of the tested sites. We considered as being differentially edited the sites with an adjusted P value < 0.05.

The get_splicing_efficiency.sh script of the ChloroSeq package (59) was adapted to get the counts of the spliced and unspliced chloroplastic and mitochondrial transcripts. The same statistical analysis as for editing sites was performed except that mitochondrial and chloroplastic splicing events were analyzed together. To mitigate the large coverage difference between the two genetic compartments, the raw counts of each compartment were normalized based on the sum of spliced and unspliced counts before the statistical analysis.

The RNA processing activity was studied through a segmentation analysis of the sequencing coverage. We counted read starts of CT and HO samples (summing over all three replicates).

We then looked for abrupt changes in the proportion of CT and HO counts along the mitochondrial and chloroplastic genome using a binomial multiple change-point model. Note that using a binomial model (rather than modeling the ratio or log-ratio between CT and HO), we easily cope with positions for which either CT or HO have zero count. To infer our multiple-change point model, we implemented the segment neighborhoods algorithm (73) for the binomial distribution in R/C. To speed up the calculation, we used the exact compression scheme (74). We consider a maximum number of changes of K = 250 and selected the number of change-points using the R package capushe (75). We recover the maximum likelihood segmentation (73), report the change-points, compute for each obtained segment the proportion of HO (P_HO) read, and report the normalized log-odd ratio:

The results of the segmentation analysis are available in Dataset S2I. But as the aim of this analysis was to detect potential processing defects, only segments shorter than 1,000 nt with a |logratio| > 1 and not explained by splicing or expression variations were considered.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

M.L.-O. and K.B.’s research was supported by French PhD fellowships from “Ministère de la Recherche et de l’Enseignement Supérieur.” D.G.’s research was supported by a Labex Saclay Plant Sciences-SPS postdoctoral fellowship. M.T. is a Heisenberg fellow, and his work is supported by grants from the DFG. The IPS2 benefits from the support of the Labex Saclay Plant Sciences-SPS (Grant ANR-10-LABX-0040-SPS).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The data reported in this paper have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo (accession no. GSE100298).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1705780114/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Ichinose M, Sugita M. RNA editing and its molecular mechanism in plant organelles. Genes (Basel) 2016;8:5. doi: 10.3390/genes8010005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sun T, Bentolila S, Hanson MR. The unexpected diversity of plant organelle RNA editosomes. Trends Plant Sci. 2016;21:962–973. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2016.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Small ID, Peeters N. The PPR motif - A TPR-related motif prevalent in plant organellar proteins. Trends Biochem Sci. 2000;25:46–47. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01520-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Delannoy E, Stanley WA, Bond CS, Small ID. Pentatricopeptide repeat (PPR) proteins as sequence-specificity factors in post-transcriptional processes in organelles. Biochem Soc Trans. 2007;35:1643–1647. doi: 10.1042/BST0351643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barkan A, Small I. Pentatricopeptide repeat proteins in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2014;65:415–442. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-050213-040159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ke J, et al. Structural basis for RNA recognition by a dimeric PPR-protein complex. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013;20:1377–1382. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barkan A, et al. A combinatorial amino acid code for RNA recognition by pentatricopeptide repeat proteins. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002910. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takenaka M, Zehrmann A, Brennicke A, Graichen K. Improved computational target site prediction for pentatricopeptide repeat RNA editing factors. PLoS One. 2013;8:e65343. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yagi Y, Hayashi S, Kobayashi K, Hirayama T, Nakamura T. Elucidation of the RNA recognition code for pentatricopeptide repeat proteins involved in organelle RNA editing in plants. PLoS One. 2013;8:e57286. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yin P, et al. Structural basis for the modular recognition of single-stranded RNA by PPR proteins. Nature. 2013;504:168–171. doi: 10.1038/nature12651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheng S, et al. Redefining the structural motifs that determine RNA binding and RNA editing by pentatricopeptide repeat proteins in land plants. Plant J. 2016;85:532–547. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lurin C, et al. Genome-wide analysis of Arabidopsis pentatricopeptide repeat proteins reveals their essential role in organelle biogenesis. Plant Cell. 2004;16:2089–2103. doi: 10.1105/tpc.104.022236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Salone V, et al. A hypothesis on the identification of the editing enzyme in plant organelles. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:4132–4138. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.07.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Boussardon C, et al. The cytidine deaminase signature HxE(x)n CxxC of DYW1 binds zinc and is necessary for RNA editing of ndhD-1. New Phytol. 2014;203:1090–1095. doi: 10.1111/nph.12928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rüdinger M, Volkmar U, Lenz H, Groth-Malonek M, Knoop V. Nuclear DYW-type PPR gene families diversify with increasing RNA editing frequencies in liverwort and moss mitochondria. J Mol Evol. 2012;74:37–51. doi: 10.1007/s00239-012-9486-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wagoner JA, Sun T, Lin L, Hanson MR. Cytidine deaminase motifs within the DYW domain of two pentatricopeptide repeat-containing proteins are required for site-specific chloroplast RNA editing. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:2957–2968. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.622084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Okuda K, et al. Pentatricopeptide repeat proteins with the DYW motif have distinct molecular functions in RNA editing and RNA cleavage in Arabidopsis chloroplasts. Plant Cell. 2009;21:146–156. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.064667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boussardon C, et al. Two interacting proteins are necessary for the editing of the NdhD-1 site in Arabidopsis plastids. Plant Cell. 2012;24:3684–3694. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.099507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takenaka M, et al. Multiple organellar RNA editing factor (MORF) family proteins are required for RNA editing in mitochondria and plastids of plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:5104–5109. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1202452109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bentolila S, et al. RIP1, a member of an Arabidopsis protein family, interacts with the protein RARE1 and broadly affects RNA editing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:E1453–E1461. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1121465109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bayer-Császár E, et al. The conserved domain in MORF proteins has distinct affinities to the PPR and E elements in PPR RNA editing factors. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2017;1860:813–828. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2017.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kupsch C, et al. Arabidopsis chloroplast RNA binding proteins CP31A and CP29A associate with large transcript pools and confer cold stress tolerance by influencing multiple chloroplast RNA processing steps. Plant Cell. 2012;24:4266–4280. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.103002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sun T, et al. An RNA recognition motif-containing protein is required for plastid RNA editing in Arabidopsis and maize. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:E1169–E1178. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1220162110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sun T, et al. A zinc finger motif-containing protein is essential for chloroplast RNA editing. PLoS Genet. 2015;11:e1005028. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chateigner-Boutin AL, et al. CLB19, a pentatricopeptide repeat protein required for editing of rpoA and clpP chloroplast transcripts. Plant J. 2008;56:590–602. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03634.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bürckstümmer T, et al. An efficient tandem affinity purification procedure for interaction proteomics in mammalian cells. Nat Methods. 2006;3:1013–1019. doi: 10.1038/nmeth968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van Leene J, Witters E, Inzé D, De Jaeger G. Boosting tandem affinity purification of plant protein complexes. Trends Plant Sci. 2008;13:517–520. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.He S, et al. A novel imprinted gene NUWA controls mitochondrial function in early seed development in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet. 2017;13:e1006553. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Verbitskiy D, Zehrmann A, Härtel B, Brennicke A, Takenaka M. Two related RNA-editing proteins target the same sites in mitochondria of Arabidopsis thaliana. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:38064–38072. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.397992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karpenahalli MR, Lupas AN, Söding J. TPRpred: A tool for prediction of TPR-, PPR- and SEL1-like repeats from protein sequences. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ding YH, Liu NY, Tang ZS, Liu J, Yang WC. Arabidopsis GLUTAMINE-RICH PROTEIN23 is essential for early embryogenesis and encodes a novel nuclear PPR motif protein that interacts with RNA polymerase II subunit III. Plant Cell. 2006;18:815–830. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.039495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Colcombet J, et al. Systematic study of subcellular localization of Arabidopsis PPR proteins confirms a massive targeting to organelles. RNA Biol. 2013;10:1557–1575. doi: 10.4161/rna.26128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ito J, Heazlewood JL, Millar AH. Analysis of the soluble ATP-binding proteome of plant mitochondria identifies new proteins and nucleotide triphosphate interactions within the matrix. J Proteome Res. 2006;5:3459–3469. doi: 10.1021/pr060403j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klodmann J, Senkler M, Rode C, Braun HP. Defining the protein complex proteome of plant mitochondria. Plant Physiol. 2011;157:587–598. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.182352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Olinares PD, Ponnala L, van Wijk KJ. Megadalton complexes in the chloroplast stroma of Arabidopsis thaliana characterized by size exclusion chromatography, mass spectrometry, and hierarchical clustering. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2010;9:1594–1615. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M000038-MCP201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zybailov B, et al. Sorting signals, N-terminal modifications and abundance of the chloroplast proteome. PLoS One. 2008;3:e1994. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Andrés-Colás N, et al. A tripartite PPR protein interaction is involved in the SLO2 editosome in plant mitochondria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:8883–8888. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1705815114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Majeran W, et al. Nucleoid-enriched proteomes in developing plastids and chloroplasts from maize leaves: A new conceptual framework for nucleoid functions. Plant Physiol. 2012;158:156–189. doi: 10.1104/pp.111.188474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huang S, et al. Experimental analysis of the rice mitochondrial proteome, its biogenesis, and heterogeneity. Plant Physiol. 2009;149:719–734. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.131300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tanz SK, et al. SUBA3: A database for integrating experimentation and prediction to define the SUBcellular location of proteins in Arabidopsis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D1185–D1191. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alonso JM, et al. Genome-wide insertional mutagenesis of Arabidopsis thaliana. Science. 2003;301:653–657. doi: 10.1126/science.1086391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bryant N, Lloyd J, Sweeney C, Myouga F, Meinke D. Identification of nuclear genes encoding chloroplast-localized proteins required for embryo development in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2011;155:1678–1689. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.168120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aryamanesh N, et al. The pentatricopeptide repeat protein EMB2654 is essential for trans-splicing of a chloroplast small ribosomal subunit transcript. Plant Physiol. 2017;173:1164–1176. doi: 10.1104/pp.16.01840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bentolila S, Oh J, Hanson MR, Bukowski R. Comprehensive high-resolution analysis of the role of an Arabidopsis gene family in RNA editing. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003584. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shi X, Germain A, Hanson MR, Bentolila S. RNA recognition motif-containing protein ORRM4 broadly affects mitochondrial RNA editing and impacts plant development and flowering. Plant Physiol. 2016;170:294–309. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.01280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Leu K-C, Hsieh M-H, Wang H-J, Hsieh H-L, Jauh G-Y. Distinct role of Arabidopsis mitochondrial P-type pentatricopeptide repeat protein-modulating editing protein, PPME, in nad1 RNA editing. RNA Biol. 2016;13:593–604. doi: 10.1080/15476286.2016.1184384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kleine T, Leister D. Retrograde signaling: Organelles go networking. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1857:1313–1325. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2016.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Göringer HU. ‘Gestalt,’ composition and function of the Trypanosoma brucei editosome. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2012;66:65–82. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-092611-150150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shikanai T. RNA editing in plant organelles: Machinery, physiological function and evolution. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63:698–708. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5449-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chateigner-Boutin AL, Small I. Plant RNA editing. RNA Biol. 2010;7:213–219. doi: 10.4161/rna.7.2.11343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Blanc V, Davidson NO. APOBEC-1-mediated RNA editing. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Syst Biol Med. 2010;2:594–602. doi: 10.1002/wsbm.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Xiu Z, et al. EMPTY PERICARP16 is required for mitochondrial nad2 intron 4 cis-splicing, complex I assembly and seed development in maize. Plant J. 2016;85:507–519. doi: 10.1111/tpj.13122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zmudjak M, et al. mCSF1, a nucleus-encoded CRM protein required for the processing of many mitochondrial introns, is involved in the biogenesis of respiratory complexes I and IV in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 2013;199:379–394. doi: 10.1111/nph.12282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Van Leene J, et al. A tandem affinity purification-based technology platform to study the cell cycle interactome in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2007;6:1226–1238. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700078-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Van Leene J, et al. Isolation of transcription factor complexes from Arabidopsis cell suspension cultures by tandem affinity purification. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;754:195–218. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-154-3_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Van Leene J, et al. Targeted interactomics reveals a complex core cell cycle machinery in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol Syst Biol. 2010;6:397. doi: 10.1038/msb.2010.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rigaill G, et al. Synthetic data sets for the identification of key ingredients for RNA-seq differential analysis. Brief Bioinform. October 11, 2016 doi: 10.1093/bib/bbw092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dobin A, et al. STAR: Ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:15–21. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Castandet B, Hotto AM, Strickler SR, Stern DB. ChloroSeq, an optimized chloroplast RNA-seq bioinformatic pipeline, reveals remodeling of the organellar transcriptome under heat stress. G3 (Bethesda) 2016;6:2817–2827. doi: 10.1534/g3.116.030783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shi X, Hanson MR, Bentolila S. Two RNA recognition motif-containing proteins are plant mitochondrial editing factors. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:3814–3825. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Alexander MP. Differential staining of aborted and nonaborted pollen. Stain Technol. 1969;44:117–122. doi: 10.3109/10520296909063335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Dreze M, et al. High-quality binary interactome mapping. Methods Enzymol. 2010;470:281–315. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(10)70012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.James P, Halladay J, Craig EA. Genomic libraries and a host strain designed for highly efficient two-hybrid selection in yeast. Genetics. 1996;144:1425–1436. doi: 10.1093/genetics/144.4.1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Clough SJ, Bent AF. Floral dip: A simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1998;16:735–743. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods. 2012;9:357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. edgeR: A Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:139–140. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Storey JD, Tibshirani R. Statistical significance for genomewide studies. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:9440–9445. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1530509100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Thimm O, et al. MAPMAN: A user-driven tool to display genomics data sets onto diagrams of metabolic pathways and other biological processes. Plant J. 2004;37:914–939. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313x.2004.02016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Benjamini Y, Yekutieli D. The control of the false discovery rate in multiple testing under dependency by Yoav Benjamini 1 and Daniel Yekutieli 2. Ann Stat. 2001;29:1165–1188. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15:550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dunn OJ. Multiple comparisons among means. J Am Stat Assoc. 1961;56:52–64. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Auger IE, Lawrence CE. Algorithms for the optimal identification of segment neighborhoods. Bull Math Biol. 1989;51:39–54. doi: 10.1007/BF02458835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cleynen A, Koskas M, Lebarbier E, Rigaill G, Robin S. Segmentor3IsBack: An R package for the fast and exact segmentation of Seq-data. Algorithms Mol Biol. 2014;9:6. doi: 10.1186/1748-7188-9-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Baudry JP, Maugis C, Michel B. Slope heuristics: Overview and implementation. Stat Comput. 2012;22:455–470. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Brehme N, Bayer-Császár E, Glass F, Takenaka M. The DYW subgroup PPR protein MEF35 targets RNA editing sites in the mitochondrial rpl16, nad4 and cob mRNAs in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0140680. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0140680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bentolila S, Babina AM, Germain A, Hanson MR. Quantitative trait locus mapping identifies REME2, a PPR-DYW protein required for editing of specific C targets in Arabidopsis mitochondria. RNA Biol. 2013;10:1520–1525. doi: 10.4161/rna.25297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hu Z, et al. Mitochondrial defects confer tolerance against cellulose deficiency. Plant Cell. 2016;28:2276–2290. doi: 10.1105/tpc.16.00540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Dahan J, et al. Disruption of the CYTOCHROME C OXIDASE DEFICIENT1 gene leads to cytochrome c oxidase depletion and reorchestrated respiratory metabolism in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2014;166:1788–1802. doi: 10.1104/pp.114.248526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Xie T, et al. Growing Slowly 1 locus encodes a PLS-type PPR protein required for RNA editing and plant development in Arabidopsis. J Exp Bot. 2016;67:5687–5698. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erw331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Härtel B, Zehrmann A, Verbitskiy D, Takenaka M. The longest mitochondrial RNA editing PPR protein MEF12 in Arabidopsis thaliana requires the full-length E domain. RNA Biol. 2013;10:1543–1548. doi: 10.4161/rna.25484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Weißenberger S, Soll J, Carrie C. The PPR protein SLOW GROWTH 4 is involved in editing of nad4 and affects the splicing of nad2 intron 1. Plant Mol Biol. 2017;93:355–368. doi: 10.1007/s11103-016-0566-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Arenas-M A, Takenaka M, Moreno S, Gómez I, Jordana X. Contiguous RNA editing sites in the mitochondrial nad1 transcript of Arabidopsis thaliana are recognized by different proteins. FEBS Lett. 2013;587:887–891. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.