Abstract

High tumor recurrence is frequently observed in patients with urinary bladder cancers (UBCs), with the need for biomarkers of prognosis and drug response. Chemoresistance and subsequent recurrence of cancers are driven by a subpopulation of tumor initiating cells, namely cancer stem-like cells (CSCs). However, the underlying molecular mechanism in chemotherapy-induced CSCs enrichment remains largely unclear. In this study, we found that during gemcitabine treatment lncRNA-Low Expression in Tumor (lncRNA-LET) was downregulated in chemoresistant UBC, accompanied with the enrichment of CSC population. Knockdown of lncRNA-LET increased UBC cell stemness, whereas forced expression of lncRNA-LET delayed gemcitabine-induced tumor recurrence. Furthermore, lncRNA-LET was directly repressed by gemcitabine treatment-induced overactivation of TGFβ/SMAD signaling through SMAD binding element (SBE) in the lncRNA-LET promoter. Consequently, reduced lncRNA-LET increased the NF90 protein stability, which in turn repressed biogenesis of miR-145 and subsequently resulted in accumulation of CSCs evidenced by the elevated levels of stemness markers HMGA2 and KLF4. Treatment of gemcitabine resistant xenografts with LY2157299, a clinically relevant specific inhibitor of TGFβRI, sensitized them to gemcitabine and significantly reduced tumorigenecity in vivo. Notably, overexpression of TGFβ1, combined with decreased levels of lncRNA-LET and miR-145 predicted poor prognosis in UBC patients. Collectively, we proved that the dysregulated lncRNA-LET/NF90/miR-145 axis by gemcitabine-induced TGFβ1 promotes UBC chemoresistance through enhancing cancer cell stemness. The combined changes in TGFβ1/lncRNA-LET/miR-145 provide novel molecular prognostic markers in UBC outcome. Therefore, targeting this axis could be a promising therapeutic approach in treating UBC patients.

Keywords: tumor recurrence, cancer stem-like cells, lncRNA-LET, miRNA biogenesis, bladder cancer.

Introduction

Urinary bladder cancer (UBC) is highly recurrent. Although cytotoxic chemotherapeutic reagents such as gemcitabine (GEM) work well for most patients initially, a majority of patients treated with GEM progressively become unresponsive after multiple rounds of treatments, and ultimately lead to tumor relapse. Chemotherapies are usually administered in cycles for fractionated killing of unsynchronized proliferating cancer cells; meanwhile they allow recovery of cells in normal tissues. However, this regimen also provides an opportunity for residual cancer cells to survive (1). Results from recent studies suggest that a small subpopulation of cells with cancer stem-like properties has a survival advantage in response to chemotherapy and may be responsible for tumor recurrence (2-5). This subpopulation is also known as cancer stem-like cells (CSCs) or tumor-initiating cells (TICs) because they retain the capacity of self-renewal and repopulation of the whole tumor bulk (6-8). However, the molecular mechanism in GEM-induced CSCs enrichment in UBC remains unclear, which hampers the application of treatments specifically targeting CSCs.

Treatment-induced cancer cell death may also be accompanied with inflammation, which has been implicated in the development of chemoresistance (9-12). Some pro-inflammatory cytokines derived from either dying cancer cells or tumor microenvironment are involved in cancer relapse. TGFβ1 is one of the most potent cytokines capable of inducing epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT), which is highly associated with the characteristics of CSCs (13).

Long noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs) are those RNA molecules with more than 200 nucleotides. Although lncRNAs do not code for any proteins, they have been implicated in different processes of cancer development including initiation, promotion and metastasis (14). Results from more recently reported studies also suggest that lncRNAs play important roles in the maintenance of cancer cell stemness and chemoresistance (15). Some lncRNAs appear to have the potential to be developed into prognosis biomarkers for chemotherapy (16). LncRNAs regulate gene expression at multiple levels, including transcriptional regulation through interacting with chromatin-modifying factors and post-transcriptional regulation through targeting mRNAs, miRNAs and proteins. How lncRNAs-mediated pro-inflammatory cytokines function in CSC and the downstream networks involved in chemoresistance are elusive. In this study, we found that CSCs were highly enriched in UBC in response to GEM treatment. Mechanistically, GEM treatment-mediated upregulation of TGFβ1 directly involved in the dysregulation of lncRNA-LET/NF90/miR-145 axis. Therefore, targeting this axis could be a potential therapeutic strategy with less recurrence.

Materials and Methods

Cell lines and human cancer tissues

Human UBC cell lines, T24, 5637, J82, SW780, BIU87, ScaBER and UMUC3 were obtained from Cell Bank of Type Culture Collection, Chinese Academy of Science (Shanghai, China). Cells were maintained in RPMI1640 supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 units/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin at 37oC. J82 cells were treated with 50 μg/ml cycloheximide (CHX; Sigma) or 20 μM MG-132 (Sigma) for 3, 6 or 12 h before lysed for protein analysis. For TGFβ1 experiment, UBC cells were treated with 2 nM TGFβ1 (Proteintech, 100-21, Rocky Hill, NJ) for 48 h, and if needed, 10 nM SB431542 (Selleck Chemical, S1067, Boston, MA) was added 1 h prior to TGFβ1 treatment.

UBC tissues (n = 60) and adjacent non-tumor tissues (n = 48) were collected from Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital affiliated to Nanjing University (Jiangsu, China) from January 2012 to October 2013. Fresh tissue samples were collected and processed within 10 min. Each sample was snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and then stored at -80°C. The paired adjacent normal tissues were isolated from at least 3 cm away from tumor boarder and with no microscopic tumor cells. All cases were in accord with the following criteria: diagnosed by postoperative histopathology; complete follow-up data available; no metastasis before surgery; no other malignant disease; and no preoperative anticancer therapy. We defined tumor recurrence as any radiological or pathological tumor found after surgery. Tumor staging was defined according to the 7th Edition of Tumor-Node-Metastasis (TNM). The data do not contain any information that could identify the patients. Informed consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the protocols were approved by the Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital Ethics Committee of Medicine for tissue sample collection (201203601).

RNA isolation, quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR), microarray and RNA immunoprecipitation (RIP) assays

Total RNAs were extracted using TRIzol (Invitrogen, 15596018), following the manufacturer's instructions. Small RNAs were extracted from tissue or cells using miRNeasy Mini isolation kit (QIAGEN). Reverse transcription of mRNA and miRNA was conducted using random primers and primers of stem-loop in TaKaRa system (Dalian, China), respectively. The levels of pri-miRNAs were quantified using the TaqMan Pri-miRNA assay kit (Assay ID Hs03303166_pri for pri-miR-143, Assay ID Hs03303169_pri for pri-miR-145; Applied Biosystems). Real-time PCR was performed using TaqMan Universal Master Mix II kit (Applied Biosystem). The levels of target genes were calculated based on the cycle threshold (Ct) values compared to a reference gene using formula 2-ΔΔCt. β-actin (ACTB) mRNA and U6 (RNU6B) snRNA were used as references for mRNA and mature miRNA, respectively. Sequences of the primer were listed in Table S1. For lncRNA profiling, Human lncRNA Discover PCR array (Bio-Serve Company, BS-lncRNA002, Shanghai, China) was used. Affymetrix miRNA 4.0 microarray was used and performed by GMINIX Company (China).

For RIP assays, cells were irradiated with 254 nm UV light (400 mJ/cm2), and homogenized in lysis buffer [150 mM KCl, 50 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 2 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM DTT, 0.5% NP-40 containing 10 U/ml RNase inhibitor (TaKaRa) and a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche)]. Cell extracts were incubated with anti-NF90 or IgG-coupled protein A beads for 4-6 h at 4°C in NT2 buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.4], 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 0.05% NP-40). After stringently washing the beads with washing buffer [50 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 300 mM KCl, 0.5 mM DTT, 0.05% NP-40, protease inhibitor cocktail, and RNase inhibitor], total RNAs were extracted with TRIzol and subjected to RT-PCR assays.

Immunoblotting

Cells or tissues were lysed in RIPA buffer containing phosphatase inhibitor cocktail I (Sigma) and protease inhibitor cocktail mini-tablet (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). Proteins in the lysates were separated on SDS-PAGE and transferred onto polyvinylidenedifluoride membrane. After blocking with 5% non-fat milk in PBST, primary antibodies for ALDH1A1 (1:500, Proteintech Group, 22109-1-AP, Chicago, IL), CD44 (1:500, Cell Signaling Technology, #3570, Beverly, MA), KLF4 (1:500, Proteintech, 11880-1-AP), HMGA2 (1:500, Proteintech, 20795-1-AP), NF90 (1:1,000, ImmunoWay, YT5036, Newark, DE), FLAG-tag (1:2,000, Cell Signaling Technology, #2368), SMAD4 (1:500, Proteintech, 10231-1-AP), p-SMAD2 (1:250, Phospho-Ser467, Signalway Antibody, 11322, College Park, MA), SMAD2 (1:500, AP0444) and β-actin (1:2,000, Bioworld) were used. The membranes were washed with PBST three times and incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody. The bands were visualized using enhanced chemiluminescence reagents (Millipore, WBKLS0100). Western blots were semi-quantified by Image J software (NIH).

Sphere formation assay

T24, 5637 cells and xenografts were trypsinized by TrypLE (Life Technologies) and washed in PBS. About 1.0×104 cells per well were seeded in the 6-well ultra-low attachment plates (Corning, Steuben County, NY) in DMEM/F12 culture medium supplemented with 10 ng/ml human recombinant bFGF and 10 ng/ml EGF (PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ). After culturing for 9-12 days with or without TGFβ1 and/or SB-431542, spheres were photographed and spheres with the diameter greater than 50 µm were counted.

Flow cytometry

Cells with high ALDH enzyme activity was identified by ALDEFLUOER kit (Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, Canada). 5 µl of activated ALDEFLUOER reagent was added to 1 ml single cell suspension and incubated at 37°C for 40 min. An ALDH-specific inhibitor, Diethylaminobenzaldehyde (DEAB), was added prior to staining as a negative control.

Luciferase assay

Luciferase assays were performed using a luciferase assay kit (Promega). For TGFβ/SMAD pathway, T24 cells were transfected with plasmids containing wild-type or ΔSBE pGL3-LET-promoter and treated with vehicle control or TGFβ1, respectively. Cells were harvested and lyzed for luciferase assay 48 h post transfection. Renilla luciferase was used for normalization.

In vivo tumor xenograft study

Animal studies were approved and carried out in accordance with Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Model Animal Research Center, Nanjing University. 5×106 of T24, 5637 and lncRNA-LET stable over-expression cells (vector control and pLET) in 0.1 ml 50% Matrigel were injected subcutaneously into the right flank of 4~6-week-old male nude mice. 10 days post inoculation, tumor-bearing mice were randomized to saline or GEM groups. GEM (50 mg/kg body weight) was given on day 1, 4, 8 and 11 via intraperitoneal injection. Tumor diameters were measured with calipers every 3 days and tumor volumes were calculated by the formula: tumor volume = π× length × width2/6. The tumors were harvested 24 h after the last treatment and snap frozen or fixed in 10% formalin, followed by embedding in paraffin. Xenografts were rinsed in PBS and mechanically minced with sterile blades in RPMI1640/5% FBS with antibiotics/antimycotics and digested with 0.5% trypsin for 5 to 10 minutes at 37°C. The dissociated cells were strained through strainer (BD) and cultured as primary cells. Cell viability was verified by trypan blue exclusion before FACS analysis, sphere assays or immunoblotting.

To investigate combined TGFβ signaling inhibition and gemcitabine treatment, we treated mice with type I TGFβ receptor kinase inhibitor LY2157299 (100 mg/kg body weight, Selleck) twice a day via orogastric gavage and GEM (50 mg/kg body weight) on day 1, 4, 8 and 11 via intraperitoneal injection.

Limiting dilution analysis of tumor subpopulations

shCTL and shLET cells were serially diluted to the designated cell number, followed by the subcutaneous injection into nude mice. The number of tumors formed from each injection was scored. The frequency of CSCs had been calculated using ELDA software (http://bioinf.wehi.edu.au/software/elda/index.html) provided by the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

5 µm-thick paraffin-embedded sections were used for IHC staining. Primary antibodies against CK5 (Covance, PRB-160P) and CK14 (Covance, PRB-155P) were incubated overnight at 4°C. After washing, biotinylated secondary antibody (Maxin, KIT-9707) was applied, followed by the procedures described previously (17).

Statistics

Data are presented as mean±standard deviation (SD) from three independent experiments unless specially stated. Mann Whitney test, Unpaired t test or Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to compare the differences of the level between cancer tissues and corresponding normal tissues. Other differences between groups were analyzed using Student's t test or One-way ANOVA followed by Newman-Keuls multiple comparison test. Pearson correlation test was used for analyzing the correlation between two continuous factors. The log-rank (Mantel-Cox) t-test was used for survival analysis. P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

GEM treatment enriches UBC stem-like cells

To mimic the process of tumor recurrence in GEM-treated patients, we first inoculated human UBC cell lines T24 or 5637 into nude mice subcutaneously and then 50 mg/kg of GEM were administered to the mice on days 1, 4, 8 and 11, followed by a two-week recovery period. The second round treatment started on day 29 for mice with T24 and 5637 xenografts, and the third round treatment started on day 57 for mice carrying 5637 xenografts. As shown in Fig. 1A and Fig. S1A, overall the tumors derived from either of these cell lines grow much slower in the GEM-treated mice than those in the vehicle group. During the first two weeks, GEM almost completely inhibited the growth of tumors derived from either of these cell lines. During the two-week recovery period, tumors grew much faster in control group, although the tumor growth rate was still lower in the GEM group. However, GEM failed to inhibit the growth of T24 and 5673 xenografts in the second and the third round of treatment, respectively.

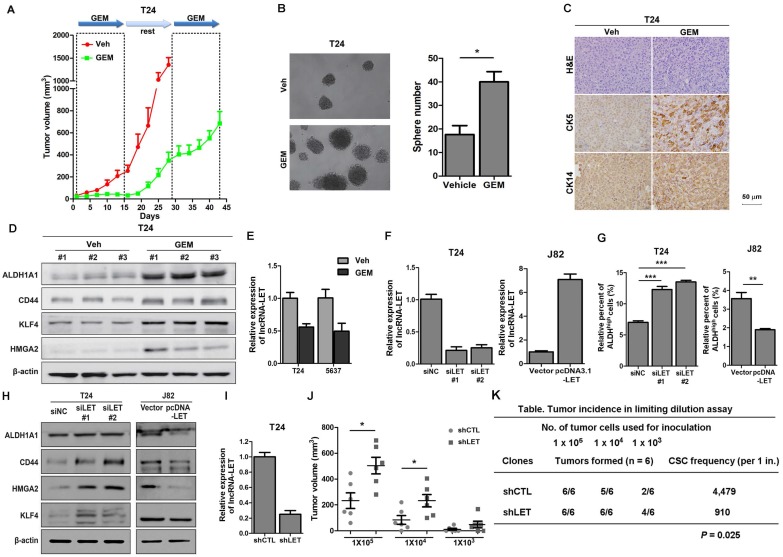

Figure 1.

Cancer stemness markers in cells treated with chemotherapeutic agents in vivo, and downregulation of lncRNA-LET enhances CSC-like properties. (A) In vivo GEM chemotherapy simulates clinical regimen with multiple GEM treatment cycles (dashed boxes) and gap periods. Tumor sizes of T24 xenografts were measured for GEM treatment and vehicle control group (n = 6 per group). (B) Sphere formation assay of primary cells derived from T24 xenografts of control group (Veh) and GEM (n=3 per group). (C) Representative H&E and IHC data showing the expression levels of CSC markers (CK5 and CK14) in T24 xenografts of control and GEM groups (n = 6 per group). (D) Western blotting of CSC markers (ALDH1A1, CD44, KLF4, and HMGA2) in T24 xenografts of control and GEM groups. (E) The levels of lncRNA-LET in T24 and 5637 cells treated with GEM or vehicle. (F) Knockdown efficiency of lncRNA-LET in T24 cells and forced expression of lncRNA-LET in J82 cells. (G-H) ALDHhigh population (G) and CSC markers (H) were determined by flow cytometer and Western blotting in T24 with knockdown and J82 cells with overexpression of lncRNA-LET (n=3 per group). (I) Knockdown efficiency of lncRNA-LET in T24 cells infected with shRNA targeting lncRNA-LET virus (shLET), compared to control (shCTL). (J) Tumor volume of shCTL and shLET T24 cells with limiting dilution. Each dot represents an individual mouse (n=6 per group). Data are shown as mean ± SD and represent three independent experiments with similar results. * P < 0.05; ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001 (Student's unpaired two-tailed t-test). (K) CSC frequency was calculated using extreme limiting dilution analysis (ELDA). There was a significant difference in CSC frequency between two groups, with a P value of 0.025.

To explore the possibility that some of the tumor cells become resistance to GEM treatment due to a subpopulation of CSCs, we sacrificed the mice and collected tumor samples at the end of the 2nd round (T24 xenografts) and the 3rd round (5637 xenografts) of treatments for further analyses. Firstly, we isolated cancer cells from xenografts and performed sphere assays. As shown in Fig. 1B and Fig. S1B, compared to that in the vehicle group, cells in GEM-treated group increased the number of spheres derived from T24 and 5637 xenografts by 2.3 and 2.2 folds, respectively. Consistently, IHC analyses showed that two UBC stemness markers CK5 and CK14 (18) were highly expressed in the GEM-treated xenografts (Fig. 1C and Fig. S1C). Furthermore, Western blotting showed that another four CSC markers (ALDH1A1, CD44, KLF4 and HMGA2) (19-24) elevated dramatically in the GEM-treated samples (Fig. 1D and Fig. S1D). Finally, we treated T24 and 5637 cells in vitro with GEM at IC50 values for T24 (3.8 μM) and 5637 (6.4 μM) cells, respectively, followed by the removal of GEM for cancer cell recovery (Fig. S2A and S2B). Compared with the vehicle, GEM treatment significantly increased the ALDHhigh population from 7.9% to 12.6% for T24 cells, and from 9.7% to 19.0% for 5637 cells (Fig. S2C). GEM-treatment also increased the CD44+ subpopulation, another CSC marker for UBC cells (Fig. S2D) and the levels of different CSC markers (Fig. S2E). Taken together, these data suggest that GEM treatment can enrich the CSC subpopulation in UBC.

Downregulation of lncRNA-LET negatively correlates with cancer stemness

To determine if lncRNAs play any roles in CSC enrichment resulted from GEM treatment, we carried out cancer-related lncRNA PCR array. GEM treatment upregulated 14 and 6 lncRNAs in T24 and 5637 xenografts, respectively; meanwhile 5 and 14 lncRNAs were downregulated by GEM treatment, respectively. Among them, lncRNA-LET was the only lncRNA that was downregulated more than 2 folds in GEM-treated xenografts derived from both T24 and 5637 cells (Table S2). The array results were further validated in these cell lines treated with or without GEM (Fig. 1E). LncRNA-LET was first found to be downregulated in hepatocellular carcinomas (25). However, its exact function in chemoresistance is unclear. Therefore, we decided to focus on this lncRNA for further study.

Next, we examined the expression of lncRNA-LET in several UBC cell lines. 5637 cells express the highest levels of lncRNA-LET, followed by T24 cells and the least in J82 cells (Fig. S1E). To determine the effect of lncRNA-LET on cancer stemness in UBC cells, lncRNA-LET was knocked down by two siRNAs, siLET-#1 and siLET-#2, in T24 and 5637 cells and overexpressed in J82 cells (Fig. 1F and Fig. S1F). The ALDHhigh populations and the levels of cancer stemness markers were assessed. As shown in Fig. 1G and Fig. S1G, depletion of lncRNA-LET increase ALDHhigh populations in T24 and 5637 cells. On the other hand, overexpression of lncRNA-LET in J82 cells reduced the ALDHhigh population by about 50% (Fig. 1G). Western blotting further confirmed the inhibitory effects of lncRNA-LET on UBC stemness, evidenced by the levels of CSC markers (Fig. 1H and Fig. S1H).

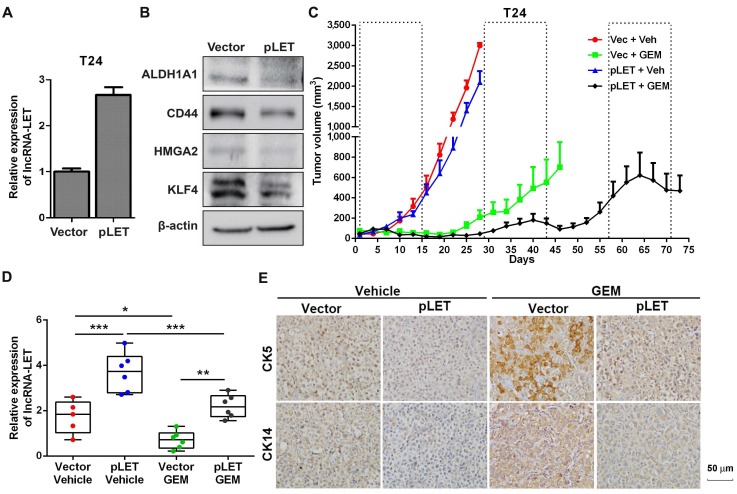

To further confirm the effects of lncRNA-LET on UBC stemness in vivo, we then established lncRNA-LET stable knockdown cells (shLET; Fig. 1I), and conducted the limiting dilution assay to rigorously test the cells' tumor-initiating capacity. We found that depletion of lncRNA-LET significantly increased both cancer incidence and tumor volumes (Fig. 1J and K). To test whether forced expression of lncRNA-LET can reverse tumor recurrence in vivo, we stably overexpressed lncRNA-LET in T24 cells (Fig. 2A), and as expected that overexpression of lncRNA-LET reduced the levels of the stemness markers (Fig. 2B). Then we inoculated the cells with lncRNA-LET overexpression into nude mice, followed by GEM treatment. As shown in Fig. 2C-D, forced expression of lncRNA-LET increased tumor latency with GEM treatment. IHC data showed that CK5 and CK14 were highly induced by GEM treatment in control but not the lncRNA-LET group (Fig. 2E). These data collectively demonstrate that lncRNA-LET is essential and sufficient for maintenance of UBC stemness, whereas forced overexpression of lncRNA-LET could partially reverse chemoresistance in UBC.

Figure 2.

The role of lncRNA-LET in GEM-induced cancer stemness. (A) qRT-PCR showed stable overexpression of lncRNA-LET in T24 cells (pLET). (B) CSC markers were determined by Western blotting in T24 cells overexpressed lncRNA-LET and control vector. (C-E) Tumor size change (C), the levels of lncRNA-LET (D) and representative IHC (E) of xenografts from control (Vec) and overexpression (pLET) cells after GEM or vehicle treatment (Vec+Veh group n=5, other group n=6). Dashed boxes indicate the time frame of each GEM chemotherapy cycle. Data are shown as mean ± SD and represent at least two independent experiments with similar results. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001 (One-way ANOVA followed by Newman-Keuls multiple comparison test).

LncRNA-LET is suppressed by TGFβ1 signaling in chemoresistant cells

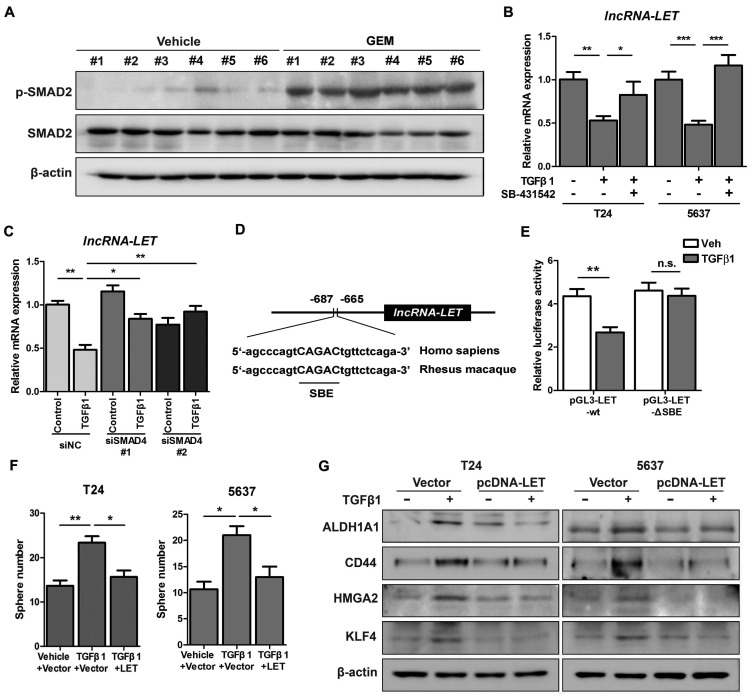

Given the facts that inflammation was proposed to be involved in the development of cancer stemness and GEM treatment might induce inflammation (9), we decided to determine if downregualtion of lncRNA-LET by GEM treatment is due to the activation of the inflammatory pathway. We examined a few well-established pro-inflammatory cytokines in T24 xenografts treated with or without GEM. Among these factors, TGFβ1 is significantly increased when the cells were treated with GEM accompanied with a couple of factors directly involved in the TGFβ signaling pathway (Fig. S3A). This observation was also substantiated by Western blotting, showing phosphorylated SMAD2 (p-SMAD2) in T24 xenografts by GEM treatment (Fig. 3A). In addition, the levels of lncRNA-LET were downregulated by TGFβ1 in both cell lines, and this effect was likely through TGFβRI because the TGFβ1-downregulated lncRNA-LET was successfully rescued by treating cells with either TGFβRI inhibitor SB-431542 (Fig. 3B and Fig. S3B) or SMAD4 siRNAs (Fig. 3C and Fig. S3C). Furthermore, TGFβ1 enhanced cancer stemness, evidenced by its effects on the number of spheres (Fig. S3D-E) and the ALDHHigh subpopulation (Fig. S3F). Overall, both TGFβRI and SMAD4 are important for TGFβ1-induced cancer stemness and the level of lncRNA-LET.

Figure 3.

TGFβ1 represses lncRNA-LET expression in UBC cells. (A) Western blotting showing the levels of p-SMAD2 and total SMAD2 in xenografts treated with or without GEM. (B-C) mRNA levels of lncRNA-LET were measured by qRT-PCR in T24 and 5637 cells treated with or without TGFβ1 or TGFβR1 inhibitor, SB-431542, as well as transfected with control (siNC) or 2 different RNAi of SMAD4 (siSMAD4#1, siSMAD4#2), followed by vehicle or TGFβ1 treatment. (D) Conserved SMAD4 binding element (SBE) in the promoter of human and Rhesus Monkey lncRNA-LET. (E) Relative luciferase activity in T24 cells transfected with plasmids of wild type (pGL3-LET-WT) and SBE deleted (pGL3-LET-ΔSBE) lncRNA-LET promoter, respectively, followed by treatment with vehicle or TGFβ1. (F-G) Sphere numbers (F) and expression of CSC markers (G) in T24 and 5637 cells treated with TGFβ1 alone or TGFβ1 and forced expression of lncRNA-LET. Data are shown as mean ± SD and represent at least two independent experiments with similar results. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001 (Student's unpaired two-tailed t-test).

Additionally, results from bioinformatic analysis identified a conserved SMAD binding element (SBE) in the promoter region of lncRNA-LET (Fig. 3D). The wild-type or ΔSBE-mutant lncRNA-LET promoter sequence was cloned into pGL3-basic plasmid and luciferase activities were measured in cells treated with or without TGFβ1. Fig. 3E shows that TGFβ1 repressed the promoter activity of wild-type but not the mutant reporter, suggesting that lncRNA-LET is a downstream target of the canonical TGFβ signaling pathway. To further validate the essentiality of lncRNA-LET downregulation in TGFβ-induced cancer stemness, we forcedly expressed lncRNA-LET in T24 and 5637 cells. Overexpression of lncRNA-LET reversed TGFβ1-induced cancer stemness, with increase of sphere number (Fig. 3F) and the expression levels of CSC markers (Fig. 3G). These data collectively demonstrate that lncRNA-LET negatively regulates TGFβ1-induced cancer stemness.

NF90 is essential in GEM-induced lncRNA-LET-mediated UBC stemness

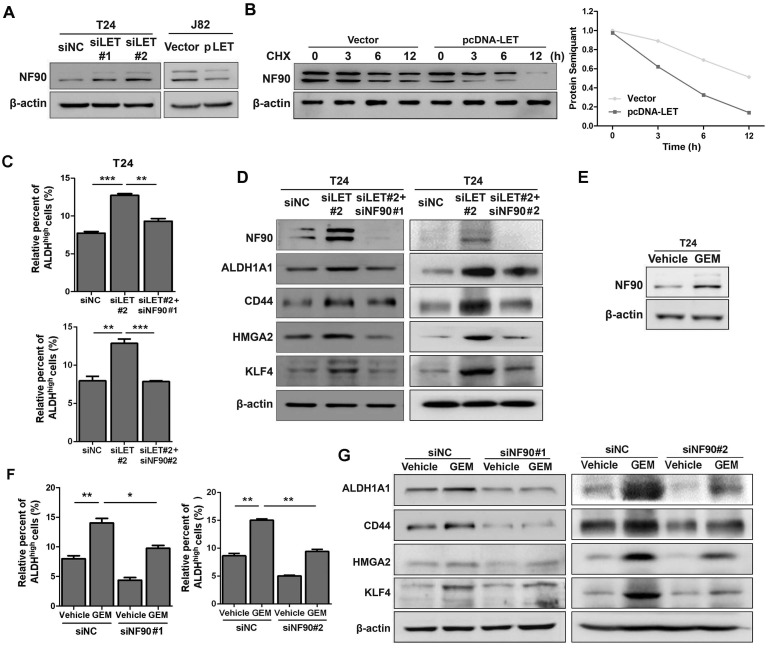

Since lncRNA-LET has been implicated in the regulation of NF90 protein stability in hepatocellular carcinoma (25), we decided to examine if NF90 is regulated by lncRNA-LET in UBC. As shown in Fig. 4A and Fig. S4A, knockdown of lncRNA-LET increased NF90 protein level in both T24 and 5637 cells; whereas forced expression of lncRNA-LET in J82 cells reduced the level of NF90. To test whether lncRNA-mediated NF90 downregulation is through enhancing protein degradation, we treated cells with cycloheximide (CHX) and evaluated NF90 levels at different time points. The half-life of NF90 was about 12 h in the control, which was reduced to about 3 h in the cells with lncRNA-LET overexpression (Fig. 4B), suggesting that lncRNA-LET-mediated NF90 downregulation was through enhancing protein degradation. In addition, NF90 protein degradation by lncRNA-LET was significantly inhibited in the presence of MG-132, an inhibitor against 26S proteasome, indicating the involvement of the 26S proteasome system (Fig. S4B). Next, we tested whether NF90 is required for lncRNA-LET-mediated cancer cell stemness. Consistent with the aforementioned experiments, lncRNA-LET depletion increased ALDHhigh populations in both T24 and 5637 cells. However, simultaneous knockdown of NF90 and lncRNA-LET significantly reduced ALDHhigh population, compared to knockdown of lncRNA-LET alone (Fig. 4C and Fig. S4C). These findings were further verified by Western blotting (Fig. 4D and Fig. S4D). Given the fact that GEM could increase NF90 at protein level in GEM-resistant cells (Fig. 4E and Fig. S4E) and knockdown of NF90 reduces GEM-induced ALDHhigh population and CSC markers (Fig. 4F-G and Fig. S4F), we conclude that NF90 is essential for GEM-induced lncRNA-LET-mediated UBC stemness.

Figure 4.

The stabilized NF90 by the reduced lncRNA-LET is required for cancer cell stemness. (A) Western blotting showing NF90 protein level in T24 with depletion of lncRNA-LET and J82 cells with overexpression of lncRNA-LET. (B) Protein level of NF90 in J82 cells over-expressed lncRNA-LET, followed by 50 μg/ml cycloheximide (CHX) treatment for the indicated time points. (C-D) ALDHhigh population (C) and expression of CSC markers (D) were determined by flow cytometer and Western blotting in control (siNC), lncRNA-LET knockdown (siLET#2), and simultaneous knockdown lncRNA-LET and NF90 (siLET#2 + siNF90#1 or siLET#2 + siNF90 #2) of T24 cells (n=3 per group). (E) Protein level of NF90 was determined by Western blotting in untreated and GEM resistant T24 cells. (F) The ALDHhigh population was determined by flow cytometer in control (siNC) and NF90 knockdown (siNF90 #1 and #2) T24 cells treated with or without GEM. (G) Western blotting showing the levels of CSC markers in control (siNC) and NF90 knockdown (siNF90 #1 and #2) T24 cells, followed by the treatment with or without GEM. Data are shown as mean ± SD and represent at least two independent experiments with similar results. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001 (Student's unpaired two-tailed t-test).

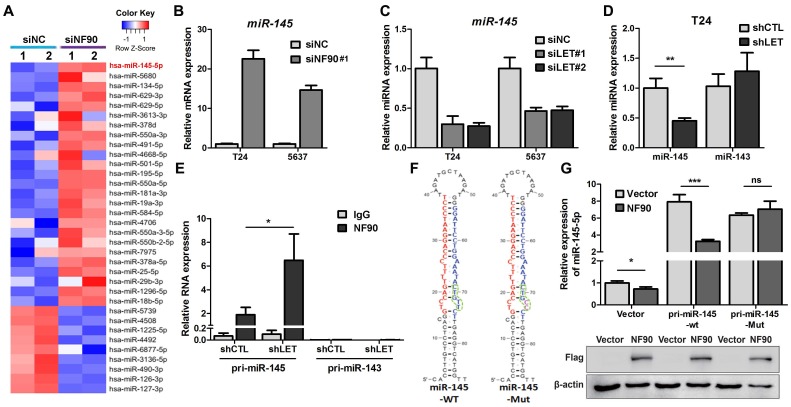

NF90 negatively regulates miR-145 biogenesis

As a RNA binding protein, NF90 plays an important role in mRNA stability and miRNA biogenesis (26). We first tested the effect of NF90 on its two known targets VEGF and HIF1α in 5637 cells and found that lncRNA-LET depletion upregulated NF90 and VEGF at protein levels, but not HIF1α, probably due to different cell type (Fig. S5A). Since the role of VEGF in UBC cell stemness is not well-established and it has been reported that NF90 could be involved in miRNA biogenesis, we conducted microarray assay to identify miRNAs potentially regulated by NF90 (GSE 82024) and found that NF90 knockdown resulted in upregulation of 25 miRNAs (≧ 2 folds) and downregulation of 9 miRNAs (≦ 0.5 fold) (Fig. 5A). Among them, miR-145 was the most highly upregulated miRNAs with 22.5-fold induction. Of note, although miR-143 and miR-145 locate in the same region on the chromosome, the levels of miR-143 was not affected significantly under the same condition.

Figure 5.

NF90 regulates miR-145 biogenesis. (A) Cluster map of microarray showed the altered miRNAs ≥ 2 folds in NF90 knockdown cells, compared with control group (siNC). (B) mRNA level of miR-145 was measured by qRT-PCR in control (siNC) and NF90 knockdown (siNF90) T24 and 5637 cells. (C) qRT-PCR showing the level of miR-145 in control (siNC) and lncRNA-LET knockdown (siLET-#1 and siLET-#2) T24 cells. (D) The levels of miR-145 and miR-143 in control (shCTL) and lncRNA-LET stable knockdown (shLET) T24 cells. (E) RIP combined with qRT-PCR assays of NF90 binding to pri-miR-143 or pri-miR-145 in control (shCTL) or lncRNA-LET knockdown (shLET) T24 cells. Relative enrichment of pri-miRNAs in anti-NF90 group, compared with IgG group. The control GAPDH mRNA level was used for normalization. (F) Schematic illustration of wild-type (WT) and mutant (Mut) miR-145 with consensus binding motif of NF90. (G) qRT-PCR analysis of exogenous miR-145 levels in T24 cells, transfected with wild-type or mutant NF90 binding site pri-miR-145 vector. Expression of FLAG in Western blotting was used to represent the NF90 transfection efficiency. Data are shown as mean ± SD and represent at least two independent experiments with similar results. * P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001 (Student's unpaired two-tailed t-test).

Next, we validated the effect of NF90 on miR-145 in T24 and 5673 cells with miR-143 as a control. Fig. 5B showed that when NF90 was knocked down by siNF90 #1, miR-145 was upregulated by 22.6 and 14.7 folds in T24 and 5637 cells, respectively. Another siRNA targeting different region of NF90 (siNF90 #2) was also used and confirmed the induction of miR-145 when NF90 was depleted (Fig. S5B, left panel). However, NF90 knockdown had no effects on miR-143 (Fig. S5B, middle and right panels). Consistent with the fact that NF90 is a lncRNA-LET target and NF90 knockdown upregulated miR-145, inhibition of lncRNA-LET resulted in downregulation of miR-145 in both cell lines (Fig. 5C). Again, knocking down lncRNA-LET had undetectable effect on miR-143 (Fig. 5D). Consistently, lncRNA-LET overexpression was capable of upregulating miR-145 without affecting miR-143 (Fig. S5C). To test whether NF90 regulates miR-145 through direct interaction, we conducted RIP assay. As shown in Fig. 5E, NF90 interacted specifically with pri-miR-145, but not pri-miR-143. To demonstrate that NF90 interacts with pri-miR-145 through the conserved NF90 binding sequence (27), we synthesized both wild-type and mutant miR-145 with the change of 5'-CTGTT-3' to 5'-CTGCC-3' and estimated the effect of NF90 on these pri-miRNAs (Fig. 5F). Fig. 5G showed that overexpressed NF90 could downregulate the wild-type but not the mutant miR-145 (top panel), although the levels of overexpressed NF90 were comparable under different transfection conditions (bottom panel). These data collectively indicate that a lncRNA-LET/NF90/miR-145 axis exists in UBC cells.

miR-145 suppresses markers of cancer stemness

To determine if miR-145 plays any role in cancer stemness, we transfected miR-145 mimic into UBC cells and monitored its effect on stemness markers. Fig. S5D shows that miR-145 repressed GEM-induced ALDHhigh population. Western blotting data further confirmed the effect of miR-145 on CSC population evidenced by the cancer stemness markers in T24 cells (Fig. S5E). Bioinformatic analyses found that both KLF4 and HMGA2 contain a potential miR-145 binding site in their 3'-UTRs (Fig. S5F). We then co-transfected T24 cells with miR-145 and reporters driven by either wild-type or mutant 3'-UTRs of the KLF4 or the HMGA2 and studied the effects of miR-145 on reporter activity. Fig. S5G shows that miR-145 inhibited reporter activities controlled by wild-type, but not mutant 3'-UTRs of either gene, suggesting that miR-145 is involved in the downregulation of these stemness markers. Consistently, ectopic expression of both KLF4 and HMGA2 were able to rescue the inhibitory effects of miR-145 against cancer stemness (Fig. S5H-I).

Inhibition of TGFβ1 signaling pathway suppressed GEM-induced UBC stemness

Next, we examined whether TGFβ signaling pathway is involved in GEM-induced cancer stemness. Using the protocol that UBC cells were transiently treated with GEM followed by removal of GEM for cancer cell recovery (Fig. S2A and S2B), we observed that GEM treatment increased ALDHHigh subpopulation in T24 cells. However, depletion of SMAD4 by RNA interfering significantly reversed the induction of CSC population (Fig. S6A), supported by consistent changes of CSC markers expression levels (ALDH1A1 and CD44; Fig. S6B). To further validate whether lncRNA-LET/NF90/miR-145 axis are regulated by TGFβ1 pathway in GEM resistant UBC cells, we performed qRT-PCR and found that GEM treatment-repressed lncRNA-LET and miR-145 were significantly increased when SMAD4 was depleted (Fig. S6C and S6D). Western blotting data also confirmed that GEM treatment stabilized NF90 protein, which was abrogated once SMAD4 was knocked down (Fig. S6B). Overall, in vitro data supported the notion that alteration of lncRNA-LET/NF90/miR-145 axis by TGFβ1 signaling accounts for GEM-mediated regulation of UBC stemness.

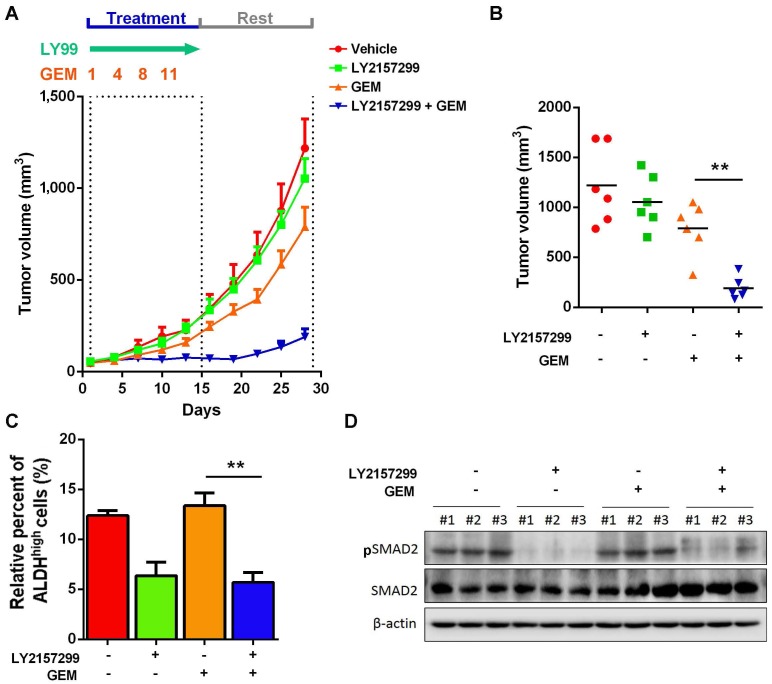

Inhibition of TGFβ1 signaling pathway sensitized GEM-resistant xenograft to chemotherapy

Given that activation of TGFβ1 signaling pathway in recurrent UBC xenografts under GEM treatment, which is essential for cancer cell stemness, we hypothesize that targeting TGFβ1 pathway may reduce CSC population and enhance efficacy of chemotherapy. To examine this hypothesis, we s.c. injected chemoresistant T24 cells, which were primarily cultured from recurrent xenografts under GEM treatment. Once we followed previous regimen, GEM showed slight anticancer effects; while LY2157299, a specific inhibitor to type I TGFβ receptor kinase, did not show remarkable reduction. Notably, combined treatment with LY21577299 and GEM significantly and strikingly repressed tumorigenicity in vivo (Fig. 6A and B). By primarily culturing cancer cells from four different T24 xenograft groups, we found that, compared to untreatment group, suppressing TGFβ1 pathway significantly reduced CSC population, though GEM alone did not further enrich CSC subpopulation in GEM-resistant T24 cells derived from previous GEM treatment (Fig. 6C). Western blotting data confirmed the successful inhibition of TGFβ1 pathway (Fig. 6D). Taken together, targeting TGFβ1 pathway may be a promising approach to suppress GEM treatment-induced cancer stemness and sensitize UBC cells to chemotherapy.

Figure 6.

Inhibition of TGFβ1 signaling pathway enhances chemosensitivity to GEM treatment in T24 UBC xenografts. (A) Tumor size change of xenografts from chemoresistant T24 cells treated with vehicle, LY2157299, GEM or both LY2157299 and GEM (n=6 per group). (B) Tumor volumes calculated on day 30 (n=6 per group). (C) ALDEFLUOR assay. The primary cells derived from xenografts were harvested on day 30, and analyzed for ALDH activity. (D) Western blotting of pSMAD2 and total SMAD2 in xenografts of the four groups. Data are shown as mean ± SD. ** P < 0.01 (Student's unpaired two-tailed t-test).

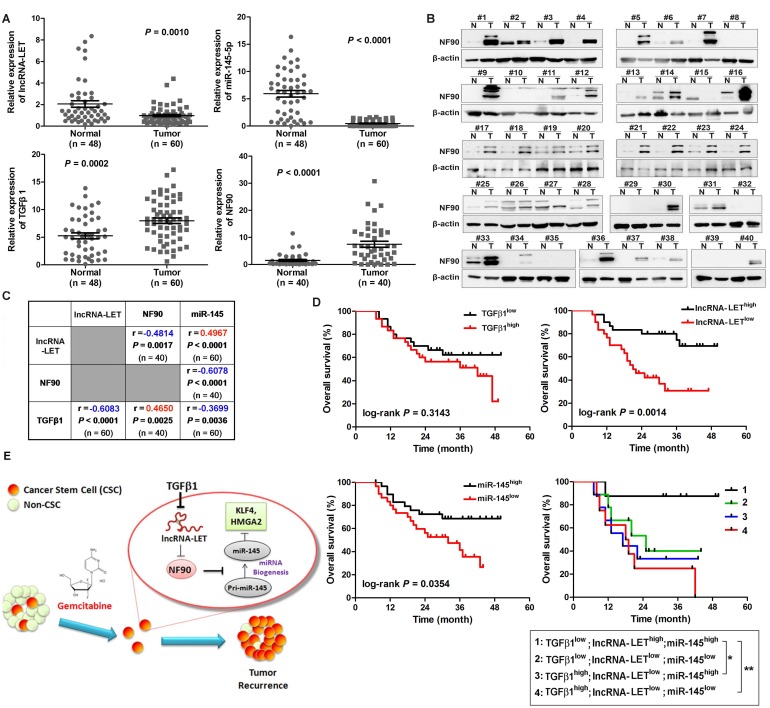

Clinical relevance of lncRNA-LET/NF90/miR-145 axis in UBC specimens

To determine the significance of the TGFβ1/lncRNA-LET/NF90/miR-145 regulatory axis in clinical UBC specimens, we analyzed their expression levels in 60 UBC samples and 48 adjacent normal tissues. Compared with those in the normal tissues, the levels of NF90 and TGFβ1 in these human UBC samples were significantly increased about 5.0 (Fig. 7A-B) and 1.5 folds (Fig. 7B), respectively. On the other hand, the levels of lncRNA-LET and miR-145 in tumors were significantly reduced by about 52% and 92%, respectively (Fig. 7A). The expression level of lncRNA-LET is significantly associated with tumor stage, microvascular invasion, lymph node metastasis and recurrence (Table S3). More importantly, the level of lncRNA-LET in tumor tissues was negatively correlated with TGFβ1 (r = -0.6083; P < 0.0001) and NF90 (r = -0.4814; P = 0.0017), but positively correlated with miR-145 (r = 0.4967; P < 0.0001; Fig. 7C). To examine the prognostic significance of TGFβ1, lncRNA-LET, and miR-145 expression levels, we performed Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of UBC patients. UBC patients which displayed lower expression levels of lncRNA-LET and miR-145 had a reduced survival rate, whereas TGFβ1 expression level did not show significant difference in clinical outcome. Moreover, UBC patients with a profile of TGFβ1low/lncRNA-LEThigh/miR-145high showed a better survival rate compared with patients with other expression profiles, such as TGFβhigh /lncRNA-LETlow/miR-145low (Fig. 7D). Overall, these data suggest that TGFβ1high/lncRNA-LETlow/ miR-145low signature could be served as a predictor of clinical outcome in UBC patients.

Figure 7.

Clinical relevance of lncRNA-LET/NF90/miR-145 axis in UBC specimens. (A). The levels of lncRNA-LET, TGFβ1, miR-145, and that of NF90 in human UBC (Tumor) and the adjacent normal tissues (Normal). Mann Whitney test, Unpaired t test or Wilcoxon signed rank test was used for analysis of statistical significance. (B) Western blotting showing NF90 expression in paired UBC (T) and adjacent normal tissues (N). (C) The correlations among lncRNA-LET, TGFβ1, miR-145 and NF90 were determined by Pearson correlation analysis. ΔCT values of qRT-PCR were used as the levels of lncRNA-LET, TGFβ1 and miR-145 transcripts. NF90 protein bands on Western blotting were semi-quantified by Image J. (D) Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of overall survival of 60 UBC patients with expression profile of TGFβ1high vs TGFβ1low, lncRNA-LET high vs lncRNA-LETlow, miR-145 high vs miR-145low. Subgroup analysis of UBC patients according to the expression profile of TGFβ1high/lncRNA-LETlow/miR-145low signature versus the other combinations. Median value was chosen as cut-off point. The log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test was used to calculate P-values. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. (E) Schematic illustration of enhancement of cancer stem-like cell properties in GEM resistant UBC cells by the dysregulation of lncRNA-LET/NF90/miR-145 axis via TGFβ1.

Discussion

Tumor chemoresistance and subsequent relapse are common in cancers, which raises a key issue for clinicians. Accumulating evidence supports the notion that a small population of CSCs inside the heterogeneous tumor bulk could be accountable for tumor recurrence (8, 28). The CSCs have intrinsic chemoresistant properties and can be selectively enriched during chemotherapy. In this study, we found that UBC stemness is enhanced during chemotherapy with GEM in vivo, evidenced by the increased levels of CSC markers, such as CK14, CK5 and CD44. This is consistent with the observation that cytotoxic chemotherapy induced CK14+ cancer cell proliferation despite reducing tumor size at initial chemotherapy cycle (29). Based on the data from both in vitro and in vivo experiments, we propose that TGFβ1 is upregulated by GEM treatment, and the TGFβ1-mediated dysregulation of the lncRNA-LET/NF90/miR-145 axis promotes cancer cell stemness in residual tumors and subsequently results in chemoresistance (Fig. 7E).

LncRNAs have been found to be frequently dysregulated in cancers and implicated in cancer stemness and chemoresistance (30, 31). LncRNA-LET has been reported to be underexpressed in cancers of digestive system and associated with cancer metastasis (25, 32, 33). We found that lncRNA-LET was also down-regulated in chemoresistant human UBC xenografts. The downregulation of lncRNA-LET was accompanied by increased NF90 protein stability, reduced biogenesis of miR-145, as well as elevated levels of stemness markers. These data indicate that lncRNA-LET plays a central role in the regulation of UBC stemness because forced expression of lncRNA-LET reduces UBC stemness markers and delays tumor relapse.

Maintenance of cancer stemness can also be regulated by extracellular cue. We found that in GEM-treated UBC xenografts TGFβ1 was upregulated and functional. This is consistent with the recent report showing that TGFβ signaling was strongly activated after paclitaxel treatment in triple-negative breast cancer tissues (34). The induction of TGFβ1 could be the results of autocrine or paracrine. We have reported that cancer-associated fibroblasts in tumor microenvironment is capable of enhancing the expression of TGFβ1 than cancer cells (35). In addition, TGFβ1 could also be derived from other cell types, including immune cells which are often recruited to tumor region during therapy (36, 37). Nevertheless, down-regulation of lncRNA-LET by overactivation of TGFβ/SMAD signaling pathway in UBC cells suggests cytokines such as TGFβ1 play important role in the regulation of UBC stemness.

We demonstrated that in different UBC cell lines lncRNA-LET could increase NF90 degradation through the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway, similar to that in hepatoma cell lines (25). NF90 is a double-stranded RNA binding protein involved in stabilization, turnover and translational control of different target mRNAs, including interleukin 2 (IL-2), hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha (HIF-1α) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) (25, 38-40). We found that VEGF, but not HIF-1α, was elevated in UBC cells with knockdown of lncRNA-LET. This suggests that in UBC cells the lncRNA-LET/NF90 axis regulating VEGF and HIF1 differently. In addition to regulating the expression of different genes post-transcriptionally, NF90 also takes part in miRNA biogenesis. As a competitor for the association of the microprocessor complex with pri-miRNAs, NF90 usually inhibits miRNA production (27, 41, 42). We found that lncRNA-LET depletion resulted in elevated level of NF90 which in turn blocks miR-145 biogenesis by competitively binding to pri-miR-145 specifically. Of note, both miR-143 and miR-145 locate on chromosome 5q33 with approximately 1.3 kb away from each other. An 11 kb transcript serves as the precursor of both miRNAs, albeit miR-145 can be generated from another 1.9 kb transcript precursor (43). It has been proposed previously that during bladder CSCs enrichment the expression of miR-145 could be regulated by an undefined mechanism (44, 45). Here we demonstrated that miR-145 biogenesis can be regulated by lncRNA-LET/NF90 axis. Although it is known that miR-145 negatively regulates human embryonic stem cells and CSCs, it is unclear whether it regulates the stemness markers indirectly or directly (45-48). We demonstrated in this report that in UBC cells KLF4 and HMGA2, two miR-145 targets, are responsible for miR-145 mediated inhibition of UBC cell stemness.

In the current study, we also examined whether TGFβ signaling pathway could be a promising therapeutic target to enhance chemosensitivity of UBC cells to GEM in vivo. LY2157299, also known as galunisertib, is a selective ATP-mimetic inhibitor of TGF-βRI serine/threonine kinase. It displayed antitumor activity, as well as acceptable tolerability and safety profile in cancer patients with advanced tumors, such as glioma (49-51). In the in vivo study herein, combined treatment of LY2157299 with GEM significantly reduced CSC subpopulation and tumorigenecity compared with either drug alone. This intriguing data support the notion that overactivation of TGFβ signaling pathway during tumor relapse can serve as a promising therapeutic target for UBC patients under chemotherapy.

In conclusion, our data demonstrated that GEM, which is commonly used for the treatment fo UBC patients, can induce TGFβ1 in recurrent tumors. The elevated TGFβ1 induces a regulatory axis of lncRNA-LET/NF90/miR-145 in UBC cells to increase CSC populations and promote chemoresistance. The notion that TGFβ1high/lncRNA-LETlow/miR-145low signature in clinical samples were correlated with poor prognosis reinforces the importance of this regulatory axis for UBC patients. Interestingly, forced expression of lncRNA-LET maintained the sensitivity of UBC cells to GEM and delaying tumor relapse, suggesting that either targeting TGFβ signaling pathway, restoration of lncRNA-LET expression or reintroduction of its downstream target miRNA could be an attractive anti-tumor approach for integrated cancer therapy (49, 52, 53).

Statement of translational relevance

Gemcitabine is commonly used in combinatory chemotherapy for muscle invasive bladder cancer patients in the neoadjuvant, adjuvant and palliative setting. However, the duration of response in various combinations and survival results is limited in the advanced or metastatic bladder cancers. Hence, it is needed for biomarkers of prognosis and drug response, as well as potential drug targets. To address this question, we identified that lncRNA-LET is downregulated in gemcitabine resistant bladder cancers, which is directly and negatively regulated pro-inflammatory cytokine TGFβ1. Importantly, the forced expression of lncRNA-LET delays bladder cancer recurrence under gemcitabine treatment. We also identified that lncRNA-LET/NF90/miR-145 axis in recurrent bladder cancer samples will provide better understanding of maintenance of cancer cell stemness. Moreover, the combined changes in TGFβ1/lncRNA-LET/miR-145 provide novel molecular prognostic markers in bladder cancer outcome. Abrogation of TGFβ1 pathway by LY2157299 sensitized bladder cancer cells to gemcitabine in vivo.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Liwei Xiao and Yuxi Yang for technical supports, as well as other lab members for helpful discussion.

Author contributions

JZ and JY designed the study with input from RH and DZ. JZ, LS, LY, XH, QL, YC, XZ performed experiments and JZ, LS, LY, and XH analyzed data. XZ and HG provided clinical samples and clinical information. JZ, RH, DZ and JY wrote the manuscript. HG and JY supervised research.

Financial support

The study was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81372168, 81572519 and 81672873), Natural Science Foundation for Universities in Jiangsu Province (BK20151396 to J.Y.), Wu Jieping Medical Foundation (320.6750.16051), "Personalized Medicines- Molecular Signature-based Drug Discovery and Development", Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Grant No. XDA 12020108 to R.H.); Institutes for Drug Discovery and Development, Chinese Academy of Sciences (CASIMM0120163010 to R.H.), and One Hundred Talent Program of Chinese Academy of Sciences (to R.H.).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary figures and tables.

References

- 1.Kim JJ, Tannock IF. Repopulation of cancer cells during therapy: an important cause of treatment failure. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:516–25. doi: 10.1038/nrc1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Al-Hajj M, Wicha MS, Benito-Hernandez A. et al. Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:3983–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0530291100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dalerba P, Cho RW, Clarke MF. Cancer stem cells: models and concepts. Annu Rev Med. 2007;58:267–84. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.58.062105.204854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li X, Lewis MT, Huang J, Gutierrez C. et al. Intrinsic resistance of tumorigenic breast cancer cells to chemotherapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:672–9. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McDermott SP, Wicha MS. Targeting breast cancer stem cells. Mol Oncol. 2010;4:404–19. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clevers H. The cancer stem cell: premises, promises and challenges. Nat Med. 2011;17:313–9. doi: 10.1038/nm.2304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kreso A, Dick JE. Evolution of the cancer stem cell model. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;14:275–91. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Visvader JE, Lindeman GJ. Cancer stem cells in solid tumours: accumulating evidence and unresolved questions. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:755–68. doi: 10.1038/nrc2499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adorno-Cruz V, Kibria G, Liu X. et al. Cancer stem cells: targeting the roots of cancer, seeds of metastasis, and sources of therapy resistance. Cancer Res. 2015;75:924–9. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-3225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen MC, Chen YL, Lee CF. et al. Supplementation of Magnolol Attenuates Skeletal Muscle Atrophy in Bladder Cancer-Bearing Mice Undergoing Chemotherapy via Suppression of FoxO3 Activation and Induction of IGF-1. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0143594. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Funamizu N, Hu C, Lacy C. et al. Macrophage migration inhibitory factor induces epithelial to mesenchymal transition, enhances tumor aggressiveness and predicts clinical outcome in resected pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2013;132:785–94. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu C, Fernandez SA, Criswell T. et al. Disrupting cytokine signaling in pancreatic cancer: a phase I/II study of etanercept in combination with gemcitabine in patients with advanced disease. Pancreas. 2013;42:813–8. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e318279b87f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roussos ET, Keckesova Z, Haley JD. et al. AACR special conference on epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cancer progression and treatment. Cancer Res. 2010;70:7360–4. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Evans JR, Feng FY, Chinnaiyan AM. The bright side of dark matter: lncRNAs in cancer. J Clin Invest. 2016;126:2775–82. doi: 10.1172/JCI84421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Majidinia M, Yousefi B. Long non-coding RNAs in cancer drug resistance development. DNA Repair (Amst) 2016;45:25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2016.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu J, Wan L, Lu K. et al. The Long Noncoding RNA MEG3 Contributes to Cisplatin Resistance of Human Lung Adenocarcinoma. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0114586. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0114586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao W, Chang C, Cui Y. et al. Steroid receptor coactivator-3 regulates glucose metabolism in bladder cancer cells through coactivation of hypoxia inducible factor 1alpha. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:11219–29. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.535989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ho PL, Lay EJ, Jian W. et al. Stat3 Activation in Urothelial Stem Cells Leads to Direct Progression to Invasive Bladder Cancer. Cancer Res. 2012;72:3135–42. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chien CS, Wang ML, Chu PY. et al. Lin28B/Let-7 Regulates Expression of Oct4 and Sox2 and Reprograms Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma Cells to a Stem-like State. Cancer Res. 2015;75:2553–65. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kong D, Su G, Zha L. et al. Coexpression of HMGA2 and Oct4 predicts an unfavorable prognosis in human gastric cancer. Med Oncol. 2014;31:130. doi: 10.1007/s12032-014-0130-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of Pluripotent Stem Cells from Mouse Embryonic and Adult Fibroblast Cultures by Defined Factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–76. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chan KS, Espinosa I, Chao M. et al. Identification, molecular characterization, clinical prognosis, and therapeutic targeting of human bladder tumor-initiating cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:14016–21. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906549106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chan KS, Volkmer J-P, Weissman I. Cancer stem cells in bladder cancer: a revisited and evolving concept. Curr Opin Urol. 2010;20:393–97. doi: 10.1097/MOU.0b013e32833cc9df. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Su Y, Qiu Q, Zhang X. et al. Aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 A1-positive cell population is enriched in tumor-initiating cells and associated with progression of bladder cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:327–37. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang F, Huo XS, Yuan SX. et al. Repression of the Long Noncoding RNA-LET by Histone Deacetylase 3 Contributes to Hypoxia-Mediated Metastasis. Mol Cell. 2013;49:1083–96. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Masuda K, Kuwano Y, Nishida K. et al. NF90 in posttranscriptional gene regulation and microRNA biogenesis. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:17111–21. doi: 10.3390/ijms140817111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hu Q, Lu YY, Noh H. et al. Interleukin enhancer-binding factor 3 promotes breast tumor progression by regulating sustained urokinase-type plasminogen activator expression. Oncogene. 2013;32:3933–43. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Creighton CJ, Li X, Landis M. et al. Residual breast cancers after conventional therapy display mesenchymal as well as tumor-initiating features. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:13820–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905718106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kurtova AV, Xiao J, Mo Q. et al. Blocking PGE2-induced tumour repopulation abrogates bladder cancer chemoresistance. Nature. 2015;517:209–13. doi: 10.1038/nature14034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Luo M, Jeong M, Sun D. et al. Long non-coding RNAs control hematopoietic stem cell function. Cell Stem Cell. 2015;16:426–38. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2015.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ma Y, Yang Y, Wang F. et al. Long non-coding RNA CCAL regulates colorectal cancer progression by activating Wnt/beta-catenin signalling pathway via suppression of activator protein 2alpha. Gut. 2016;65:1494–504. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-308392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang PL, Liu B, Xia Y. et al. Long non-coding RNA-Low Expression in Tumor inhibits the invasion and metastasis of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma by regulating p53 expression. Mol Med Rep. 2016;13:3074–82. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2016.4913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou B, Jing XY, Wu JQ. et al. Down-regulation of long non-coding RNA LET is associated with poor prognosis in gastric cancer. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2014;7:8893–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bhola NE, Balko JM, Dugger TC. et al. TGF-beta inhibition enhances chemotherapy action against triple-negative breast cancer. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:1348–58. doi: 10.1172/JCI65416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhuang J, Lu Q, Shen B. et al. TGFbeta1 secreted by cancer-associated fibroblasts induces epithelial-mesenchymal transition of bladder cancer cells through lncRNA-ZEB2NAT. Sci Rep. 2015;5:11924. doi: 10.1038/srep11924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fan QM, Jing YY, Yu GF. et al. Tumor-associated macrophages promote cancer stem cell-like properties via transforming growth factor-beta1-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2014;352:160–8. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xian G, Zhao J, Qin C. et al. Simvastatin attenuates macrophage-mediated gemcitabine resistance of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma by regulating the TGF-β1/Gfi-1 axis. Cancer Lett. 2017;385:65–74. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kuwano Y, Pullmann R Jr, Marasa BS. et al. NF90 selectively represses the translation of target mRNAs bearing an AU-rich signature motif. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:225–38. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shim J, Lim H, J RY. et al. Nuclear export of NF90 is required for interleukin-2 mRNA stabilization. Mol Cell. 2002;10:1331–44. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00730-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vumbaca F, Phoenix KN, Rodriguez-Pinto D. et al. Double-stranded RNA-binding protein regulates vascular endothelial growth factor mRNA stability, translation, and breast cancer angiogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:772–83. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02078-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sakamoto S, Aoki K, Higuchi T. et al. The NF90-NF45 complex functions as a negative regulator in the microRNA processing pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:3754–69. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01836-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Volk N, Shomron N. Versatility of MicroRNA biogenesis. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19391. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Iio A, Nakagawa Y, Hirata I. et al. Identification of non-coding RNAs embracing microRNA-143/145 cluster. Mol Cancer. 2010;9:136. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sachdeva M, Zhu S, Wu F. et al. p53 represses c-Myc through induction of the tumor suppressor miR-145. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:3207–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808042106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Xu N, Papagiannakopoulos T, Pan G. et al. MicroRNA-145 regulates OCT4, SOX2, and KLF4 and represses pluripotency in human embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2009;137:647–58. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Davis-Dusenbery BN, Chan MC, Reno KE. et al. down-regulation of Kruppel-like factor-4 (KLF4) by microRNA-143/145 is critical for modulation of vascular smooth muscle cell phenotype by transforming growth factor-beta and bone morphogenetic protein 4. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:28097–110. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.236950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim TH, Song JY, Park H. et al. miR-145, targeting high-mobility group A2, is a powerful predictor of patient outcome in ovarian carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2015;356:937–45. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2014.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yu CC, Tsai LL, Wang ML. et al. miR145 targets the SOX9/ADAM17 axis to inhibit tumor-initiating cells and IL-6-mediated paracrine effects in head and neck cancer. Cancer Res. 2013;73:3425–40. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rodon J, Carducci MA, Sepulveda-Sánchez JM. et al. First-in-human dose study of the novel transforming growth factor-β receptor I kinase inhibitor LY2157299 monohydrate in patients with advanced cancer and glioma. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:553–60. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fujiwara Y, Nokihara H, Yamada Y. et al. Phase 1 study of galunisertib, a TGF-beta receptor I kinase inhibitor, in Japanese patients with advanced solid tumors. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2015;76:1143–52. doi: 10.1007/s00280-015-2895-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rodon J, Carducci M Sepulveda-Sanchez JM. et al. Pharmacokinetic, pharmacodynamic and biomarker evaluation of transforming growth factor-beta receptor I kinase inhibitor, galunisertib, in phase 1 study in patients with advanced cancer. Invest New Drugs. 2015;33:357–70. doi: 10.1007/s10637-014-0192-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dai X, Tan C. Combination of microRNA therapeutics with small-molecule anticancer drugs: mechanism of action and co-delivery nanocarriers. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2015;81:184–97. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2014.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhong Z, Carroll KD, Policarpio D. et al. Anti-transforming growth factor beta receptor II antibody has therapeutic efficacy against primary tumor growth and metastasis through multieffects on cancer, stroma, and immune cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:1191–205. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary figures and tables.