Abstract

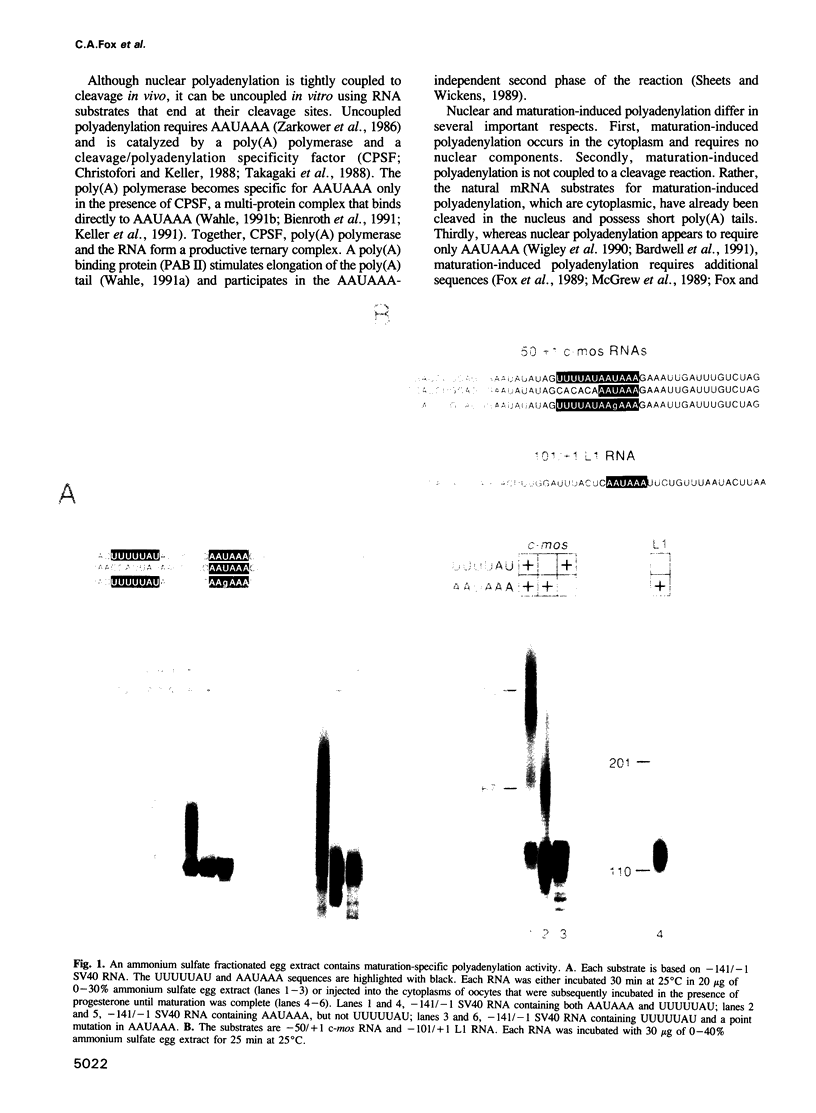

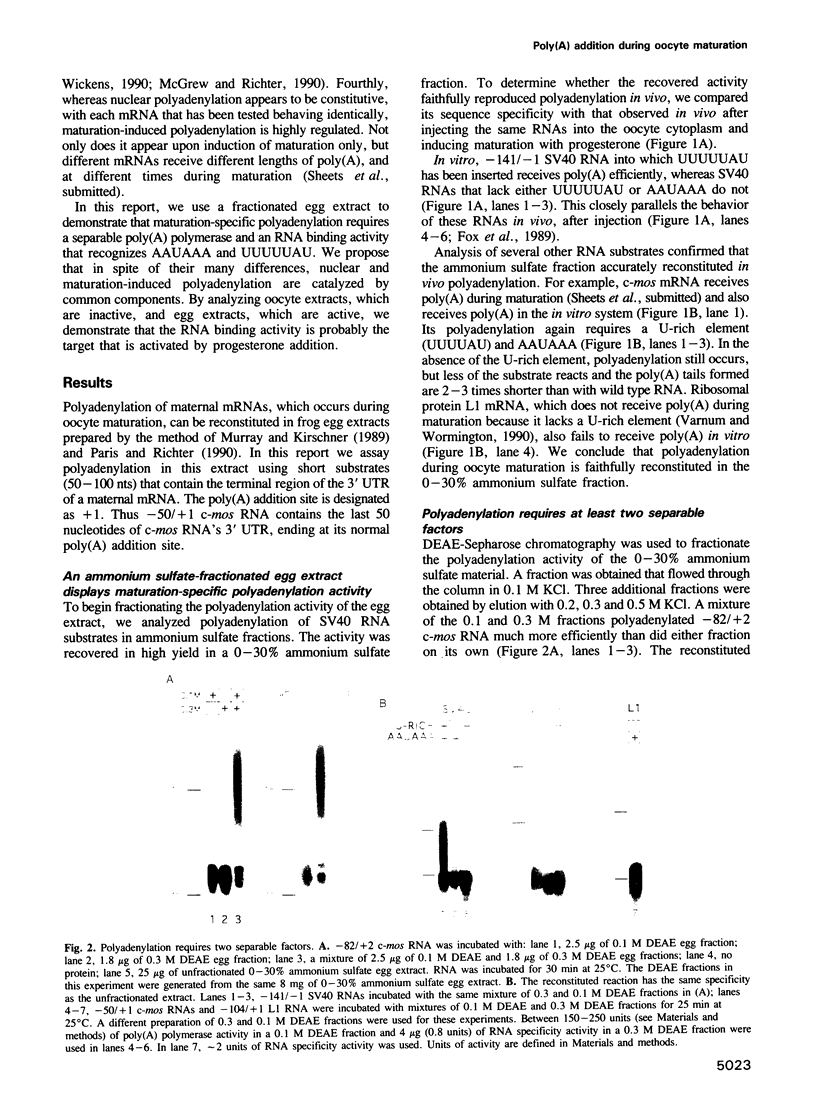

Specific maternal mRNAs receive poly(A) during early development as a means of translational regulation. In this report, we investigated the mechanism and control of poly(A) addition during frog oocyte maturation, in which oocytes advance from first to second meiosis becoming eggs. We analyzed polyadenylation in vitro in oocyte and egg extracts. In vivo, polyadenylation during maturation requires AAUAAA and a U-rich element. The same sequences are required for polyadenylation in egg extracts in vitro. The in vitro reaction requires at least two separable components: a poly(A) polymerase and an RNA binding activity with specificity for AAUAAA and the U-rich element. The poly(A) polymerase is similar to nuclear poly(A) polymerases in mammalian cells. Through a 2000-fold partial purification, the frog egg and mammalian enzymes were found to be very similar. More importantly, a purified calf thymus poly(A) polymerase acquired the sequence specificity seen during frog oocyte maturation when mixed with the frog egg RNA binding fraction, demonstrating the interchangeability of the two enzymes. To determine how polyadenylation is activated during maturation, we compared polymerase and RNA binding activities in oocyte and egg extracts. Although oocyte extracts were much less active in maturation-specific polyadenylation, they contained nearly as much poly(A) polymerase activity. In contrast, the RNA binding activity differed dramatically in oocyte and egg extracts: oocyte extracts contained less binding activity and the activity that was present exhibited an altered mobility in gel retardation assays. Finally, we demonstrate that components present in the RNA binding fraction are rate-limiting in the oocyte extract, suggesting that fraction contains the target that is activated by progesterone treatment. This target may be the RNA binding activity itself. We propose that in spite of the many biological differences between them, nuclear polyadenylation and cytoplasmic polyadenylation during early development may be catalyzed by similar, or even identical, components.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bardwell V. J., Wickens M., Bienroth S., Keller W., Sproat B. S., Lamond A. I. Site-directed ribose methylation identifies 2'-OH groups in polyadenylation substrates critical for AAUAAA recognition and poly(A) addition. Cell. 1991 Apr 5;65(1):125–133. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90414-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford M. M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976 May 7;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christofori G., Keller W. 3' cleavage and polyadenylation of mRNA precursors in vitro requires a poly(A) polymerase, a cleavage factor, and a snRNP. Cell. 1988 Sep 9;54(6):875–889. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(88)91263-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driever W., Nüsslein-Volhard C. The bicoid protein is a positive regulator of hunchback transcription in the early Drosophila embryo. Nature. 1989 Jan 12;337(6203):138–143. doi: 10.1038/337138a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin M. B., Dworkin-Rastl E. Functions of maternal mRNA in early development. Mol Reprod Dev. 1990 Jul;26(3):261–297. doi: 10.1002/mrd.1080260310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmonds M. Polyadenylate polymerases. Methods Enzymol. 1990;181:161–170. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)81118-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egrie J. C., Wilt F. H. Changes in poly(adenylic acid) polymerase activity during sea urchin embryogenesis. Biochemistry. 1979 Jan 23;18(2):269–274. doi: 10.1021/bi00569a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox C. A., Sheets M. D., Wickens M. P. Poly(A) addition during maturation of frog oocytes: distinct nuclear and cytoplasmic activities and regulation by the sequence UUUUUAU. Genes Dev. 1989 Dec;3(12B):2151–2162. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.12b.2151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox C. A., Wickens M. Poly(A) removal during oocyte maturation: a default reaction selectively prevented by specific sequences in the 3' UTR of certain maternal mRNAs. Genes Dev. 1990 Dec;4(12B):2287–2298. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.12b.2287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhart J., Wu M., Kirschner M. Cell cycle dynamics of an M-phase-specific cytoplasmic factor in Xenopus laevis oocytes and eggs. J Cell Biol. 1984 Apr;98(4):1247–1255. doi: 10.1083/jcb.98.4.1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmartin G. M., Nevins J. R. An ordered pathway of assembly of components required for polyadenylation site recognition and processing. Genes Dev. 1989 Dec;3(12B):2180–2190. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.12b.2180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurdon J. B., Wickens M. P. The use of Xenopus oocytes for the expression of cloned genes. Methods Enzymol. 1983;101:370–386. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(83)01028-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman L. E., Wormington W. M. Translational inactivation of ribosomal protein mRNAs during Xenopus oocyte maturation. Genes Dev. 1988 May;2(5):598–605. doi: 10.1101/gad.2.5.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson R. J., Standart N. Do the poly(A) tail and 3' untranslated region control mRNA translation? Cell. 1990 Jul 13;62(1):15–24. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90235-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller W., Bienroth S., Lang K. M., Christofori G. Cleavage and polyadenylation factor CPF specifically interacts with the pre-mRNA 3' processing signal AAUAAA. EMBO J. 1991 Dec;10(13):4241–4249. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb05002.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunkel T. A. Rapid and efficient site-specific mutagenesis without phenotypic selection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985 Jan;82(2):488–492. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.2.488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manley J. L. Polyadenylation of mRNA precursors. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1988 May 6;950(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/0167-4781(88)90067-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrew L. L., Dworkin-Rastl E., Dworkin M. B., Richter J. D. Poly(A) elongation during Xenopus oocyte maturation is required for translational recruitment and is mediated by a short sequence element. Genes Dev. 1989 Jun;3(6):803–815. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.6.803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrew L. L., Richter J. D. Translational control by cytoplasmic polyadenylation during Xenopus oocyte maturation: characterization of cis and trans elements and regulation by cyclin/MPF. EMBO J. 1990 Nov;9(11):3743–3751. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07587.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore C. L., Skolnik-David H., Sharp P. A. Analysis of RNA cleavage at the adenovirus-2 L3 polyadenylation site. EMBO J. 1986 Aug;5(8):1929–1938. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04446.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray A. W., Kirschner M. W. Cyclin synthesis drives the early embryonic cell cycle. Nature. 1989 May 25;339(6222):275–280. doi: 10.1038/339275a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paris J., Richter J. D. Maturation-specific polyadenylation and translational control: diversity of cytoplasmic polyadenylation elements, influence of poly(A) tail size, and formation of stable polyadenylation complexes. Mol Cell Biol. 1990 Nov;10(11):5634–5645. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.11.5634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paris J., Swenson K., Piwnica-Worms H., Richter J. D. Maturation-specific polyadenylation: in vitro activation by p34cdc2 and phosphorylation of a 58-kD CPE-binding protein. Genes Dev. 1991 Sep;5(9):1697–1708. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.9.1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryner L. C., Takagaki Y., Manley J. L. Multiple forms of poly(A) polymerases purified from HeLa cells function in specific mRNA 3'-end formation. Mol Cell Biol. 1989 Oct;9(10):4229–4238. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.10.4229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagata N., Oskarsson M., Copeland T., Brumbaugh J., Vande Woude G. F. Function of c-mos proto-oncogene product in meiotic maturation in Xenopus oocytes. Nature. 1988 Oct 6;335(6190):519–525. doi: 10.1038/335519a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheets M. D., Stephenson P., Wickens M. P. Products of in vitro cleavage and polyadenylation of simian virus 40 late pre-mRNAs. Mol Cell Biol. 1987 Apr;7(4):1518–1529. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.4.1518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheets M. D., Wickens M. Two phases in the addition of a poly(A) tail. Genes Dev. 1989 Sep;3(9):1401–1412. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.9.1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Struhl G., Struhl K., Macdonald P. M. The gradient morphogen bicoid is a concentration-dependent transcriptional activator. Cell. 1989 Jun 30;57(7):1259–1273. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90062-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takagaki Y., MacDonald C. C., Shenk T., Manley J. L. The human 64-kDa polyadenylylation factor contains a ribonucleoprotein-type RNA binding domain and unusual auxiliary motifs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992 Feb 15;89(4):1403–1407. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.4.1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takagaki Y., Ryner L. C., Manley J. L. Separation and characterization of a poly(A) polymerase and a cleavage/specificity factor required for pre-mRNA polyadenylation. Cell. 1988 Mar 11;52(5):731–742. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90411-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valsamakis A., Zeichner S., Carswell S., Alwine J. C. The human immunodeficiency virus type 1 polyadenylylation signal: a 3' long terminal repeat element upstream of the AAUAAA necessary for efficient polyadenylylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991 Mar 15;88(6):2108–2112. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.6.2108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varnum S. M., Wormington W. M. Deadenylation of maternal mRNAs during Xenopus oocyte maturation does not require specific cis-sequences: a default mechanism for translational control. Genes Dev. 1990 Dec;4(12B):2278–2286. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.12b.2278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassalli J. D., Huarte J., Belin D., Gubler P., Vassalli A., O'Connell M. L., Parton L. A., Rickles R. J., Strickland S. Regulated polyadenylation controls mRNA translation during meiotic maturation of mouse oocytes. Genes Dev. 1989 Dec;3(12B):2163–2171. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.12b.2163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahle E. A novel poly(A)-binding protein acts as a specificity factor in the second phase of messenger RNA polyadenylation. Cell. 1991 Aug 23;66(4):759–768. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90119-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahle E. Purification and characterization of a mammalian polyadenylate polymerase involved in the 3' end processing of messenger RNA precursors. J Biol Chem. 1991 Feb 15;266(5):3131–3139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahle E. Purification and characterization of a mammalian polyadenylate polymerase involved in the 3' end processing of messenger RNA precursors. J Biol Chem. 1991 Feb 15;266(5):3131–3139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahle E. The end of the message: 3'-end processing leading to polyadenylated messenger RNA. Bioessays. 1992 Feb;14(2):113–118. doi: 10.1002/bies.950140208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wharton R. P., Struhl G. RNA regulatory elements mediate control of Drosophila body pattern by the posterior morphogen nanos. Cell. 1991 Nov 29;67(5):955–967. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90368-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickens M. How the messenger got its tail: addition of poly(A) in the nucleus. Trends Biochem Sci. 1990 Jul;15(7):277–281. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(90)90054-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickens M. In the beginning is the end: regulation of poly(A) addition and removal during early development. Trends Biochem Sci. 1990 Aug;15(8):320–324. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(90)90022-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigley P. L., Sheets M. D., Zarkower D. A., Whitmer M. E., Wickens M. Polyadenylation of mRNA: minimal substrates and a requirement for the 2' hydroxyl of the U in AAUAAA. Mol Cell Biol. 1990 Apr;10(4):1705–1713. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.4.1705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodland H. The translational control phase of early development. Biosci Rep. 1982 Jul;2(7):471–491. doi: 10.1007/BF01115246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarkower D., Stephenson P., Sheets M., Wickens M. The AAUAAA sequence is required both for cleavage and for polyadenylation of simian virus 40 pre-mRNA in vitro. Mol Cell Biol. 1986 Jul;6(7):2317–2323. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.7.2317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]