Abstract

Cardiovascular (CV) disease is the leading cause of death in chronic kidney disease (CKD) and end-stage renal disease (ESRD). A key driver in this pathology is increased aortic stiffness, which is a strong, independent predictor of CV mortality in this population. Aortic stiffening is a potentially modifiable biomarker of CV dysfunction and in risk stratification for patients with CKD and ESRD. Previous work has suggested that therapeutic modification of aortic stiffness may ameliorate CV mortality. Nevertheless, future clinical implementation relies on the ability to accurately and reliably quantify stiffness in renal disease. Pulse wave velocity (PWV) is an indirect measure of stiffness and is the accepted standard for non-invasive assessment of aortic stiffness. It has typically been measured using techniques such as applanation tonometry, which is easy to use but hindered by issues such as the inability to visualize the aorta. Advances in cardiac magnetic resonance imaging now allow direct measurement of stiffness, using aortic distensibility, in addition to PWV. These techniques allow measurement of aortic stiffness locally and are obtainable as part of a comprehensive, multiparametric CV assessment. The evidence cannot yet provide a definitive answer regarding which technique or parameter can be considered superior. This review discusses the advantages and limitations of non-invasive methods that have been used to assess aortic stiffness, the key studies that have assessed aortic stiffness in patients with renal disease and why these tools should be standardized for use in clinical trial work.

Keywords: aortic stiffness, cardiovascular disease, chronic renal failure, end-stage renal failure, pulse wave velocity

Introduction

Patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) are at significantly elevated cardiovascular (CV) risk [1]. Around 50% of deaths in end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients are attributed to CV disease (CVD) [2]. These excessive rates of CVD are not solely explained by traditional risk factors [3], and coronary artery revascularization does not improve outcomes in ESRD patients to the same extent as in the general population [4]. The pathophysiological processes that drive CVD in patients with CKD and ESRD are complex and include chronic inflammation, increased arterial stiffness, autonomic instability and the insults of dialysis itself [5, 6]. These factors lead to changes in cardiac structure and function, including left ventricle hypertrophy (LVH), left ventricle (LV) dilatation and myocardial fibrosis, which are typically termed uremic cardiomyopathy [7]. A fundamental factor behind LVH is the development of aortic stiffness, which offsets the finely tuned coupling of the heart and arterial system, or the ‘arterial-ventricular interaction’ [8]. This arterial-ventricular interaction refers to the ratio between the arterial load exerted on the LV and LV performance (Figure 1). It is physiologically matched, ensuring optimal cardiac efficiency for a given stroke volume; disruption of this ratio impairs CV performance. Typically in this interaction, the ascending aorta provides capacitance. Its stretch and recoil buffer blood pressure (BP), accommodating the stroke volume ejected during systole and maintaining smooth flow to the peripheries during diastole [9]. Disease states that lead to stiffening of the aorta (e.g. CKD) reduce this buffering ability, exposing organs to peaks and troughs in BP [10]. Stiffening also increases afterload; to maintain the coupling ratio, the LV must generate higher pressures to eject blood into a more rigid arterial system, with resultant LVH and dilatation [11].

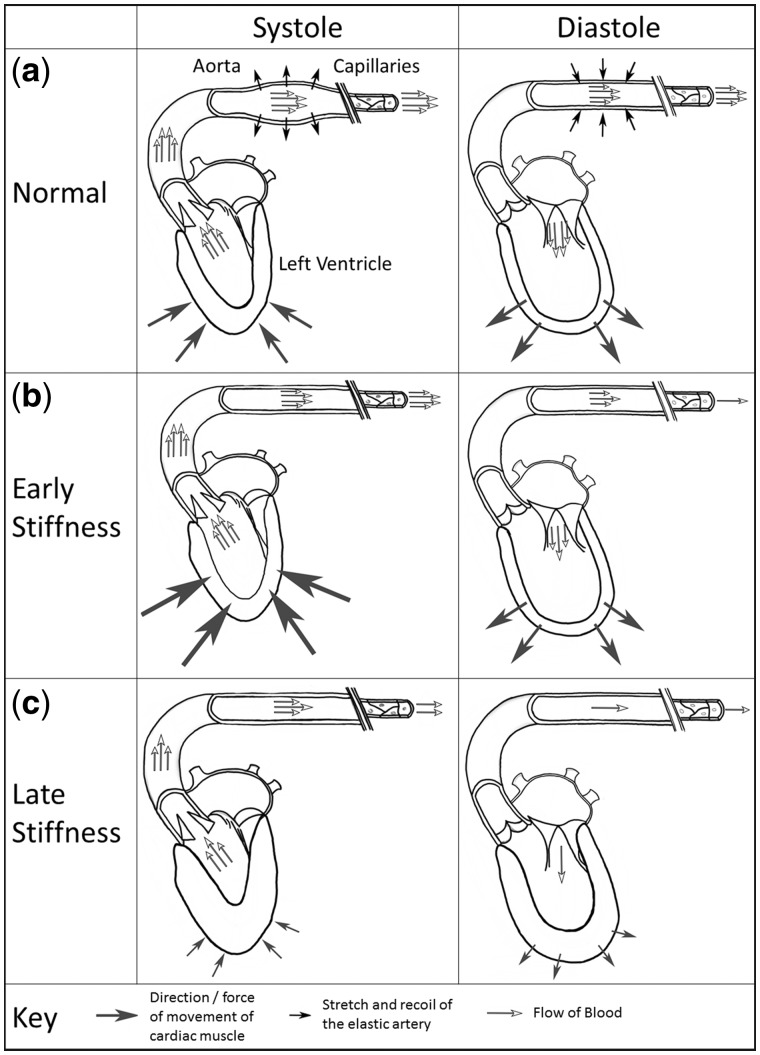

Fig. 1.

The arterial–ventricular interaction and the effect of aortic stiffening. (a) In systole, stretch of the aortic walls stores a proportion of the stroke volume while blood flows to the capillaries; this reduces the systolic pressure necessary for cardiac output to the peripheries. Aortic recoil maintains diastolic pressure (despite ventricular relaxation); this displaces stored blood, enabling continued blood flow. The LV workload is attenuated and capillary perfusion is sustained. (b) Stiffening of the aorta diminishes this storage capacity. The LV must work harder in systole to attempt to eject the entire stroke volume to the peripheries. Poor aortic recoil in diastole reduces flow to the capillaries. Systolic pressure is increased and diastolic pressure decreases. (c) Increased afterload on the LV and poor perfusion of the coronary arteries leads to concentric hypertrophy and fibrosis, impacting LV contraction and relaxation.

Factors that influence aortic stiffness

Arterial stiffness increases with age [12–14] and BP [15, 16]. In addition to CKD and haemodialysis (HD) [17, 18], associations with comorbidities such as diabetes [19, 20], CVD [21, 22] and obesity [23, 24] are established. Aortic stiffness may be higher in women [25, 26], although large population studies have shown no effect of gender [27, 28]. It is suggested that the greater aortic stiffness observed in Black and Hispanic populations compared with Whites may contribute to their increased burden of CVD [15, 29].

Aortic stiffening in renal disease

Arterial stiffening in patients with CKD and ESRD occurs at an accelerated rate compared with the normal ageing process and arteriosclerosis (typified by increased collagen, calcification and proliferation of smooth muscle cells in the tunica media), rather than atherosclerosis, is the predominant pathogenic process [8]. This may explain the limited success of interventions targeting hypertension, hyperlipidaemia and diabetes, despite a high burden of these atherosclerotic risk factors in this patient group [30]. The Study of Heart and Renal Protection (SHARP) showed that the benefit of statin therapy for early CKD was not present for dialysis patients [31, 32], implying the risk factors associated with CVD change with CKD progression. As bone mineral metabolism worsens with advancement to ESRD, associated hyperphosphataemia, secondary hyperparathyroidism and inhibited vitamin D synthesis result in vascular calcification that causes hardening of the arteries. Other factors linked to the uremic environment, such as anaemia, endothelial dysfunction, neuro-hormonal activation and inflammation, play important roles [8].

Arterial stiffening is one of the earliest signs of CV dysfunction in CKD, detectable before ejection fraction or diastolic filling are overtly impaired [11, 33, 34]. Earlier and enhanced quantification of aortic stiffness in patients may improve disease risk stratification and is an attractive imaging biomarker for use in clinical trials. The gold standard for measuring aortic stiffness involves invasive catheterization of the aorta; this is expensive, carries some risk and is not clinically practical. This review will discuss non-invasive methods of assessing aortic stiffness in patients with CKD and ESRD.

Assessment of aortic stiffness

The capacitance of large arteries is described by the parameters ‘compliance’ and ‘distensibility’, which are the absolute (ΔV) and relative (ΔV/V) volume change for a given pressure change (ΔP). Aortic distensibility (AD), as a measure of compliance relative to blood volume in the vessel, is better allied to stiffness of the wall itself and decreases in vessels injured by arteriosclerosis and atherosclerosis. AD is calculated as:

| (1) |

where AD is aortic distensibility and ΔP is the change in pressure.

As the axial length of arteries does not change significantly in expansion or recoil, cross-sectional area is a good estimation of volume in clinical research [35].

Ejection of the stroke volume into the aorta propagates an easily detectable pressure waveform. Pulse wave velocity (PWV) is the velocity at which this wave is transmitted through the arterial system. It is calculated as the distance travelled divided by the transit time, expressed in m/s. A rigid vessel will show less deformation in response to pressure and consequently PWV increases. This relationship is expressed by the Bramwell–Hill equation:

| (2) |

where A, ΔA refer to area, density of blood and change in area, respectively.

Simply, aortic PWV (aPWV) is inversely proportional to AD [36]. As the waveform progresses to the peripheries, branching vessels cause wave ‘reflection’ back to the central arteries, amplifying systolic pressure, although the relevance of this phenomenon is contentious [37].

Parameters for measuring aortic stiffness

Carotid–femoral PWV (cfPWV), assessed by calculating pulse wave transit from the carotid to femoral artery, is a widely accepted non-invasive estimate of central aPWV [38]. Many studies have used cfPWV as an indirect measure of aortic stiffness, utilizing a number of different modalities [39, 40]; Doppler, mechanotransducer and applanation tonometry techniques are commonly used. AD has recently emerged as a direct measure of aortic stiffness. While distensibility has been measured with ultrasound [41, 42], developments in cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging promise more precise measurement of AD. While the early evidence for directly measuring stiffness using CMR is promising, AD is a relatively new parameter and thus requires further validation.

Brachial–ankle PWV (baPWV) has been used as a simple measure of peripheral artery PWV. Indeed, baPWV was an objective indicator of CV risk in a recent meta-analysis [43]. Nevertheless, Pannier et al. [44] found that PWV calculated centrally, at the aorta, had greater prognostic power than peripheral measurements. Capacitance, and its loss, is most significant at the aorta and plays a larger role in the pathogenesis of CVD. Peripheral measurements are a gauge of smaller, muscular arteries; it is unknown whether changes in peripheral values directly represent the central arterial–ventricular interaction or simply correlate with general vascular improvement. Alternative parameters, such as the augmentation index, do not represent aortic stiffness or predict mortality [45, 46]. Table 1 lists the advantages and disadvantages of common techniques used to measure aortic stiffness in ESRD populations. Importantly, CMR-derived parameters (AD and aPWV) measure stiffness locally, at the aortic arch, whereas other modalities use cfPWV to make a regional assessment of the aorta.

Table 1.

Imaging modalities used for the assessment of aortic stiffness and the relative advantages and disadvantages of each

| Modality (device) | Parameter | Advantages | Disadvantages | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regional stiffness | Doppler | cfPWVa |

|

|

| Mechano- transducer (Complior) | cfPWV |

|

|

|

| Applanation tonometry (SpyghmoCor) | cfPWV |

|

|

|

| Local stiffness | CMR | aPWV and AD |

|

|

It is possible to undertake a local measurement of arterial distensibility using Doppler techniques but there is little evidence using it in ESRD populations and that is beyond the scope of this review.

Regional modalities for assessing aortic stiffness: Doppler, mechanotransducer and applanation tonometry

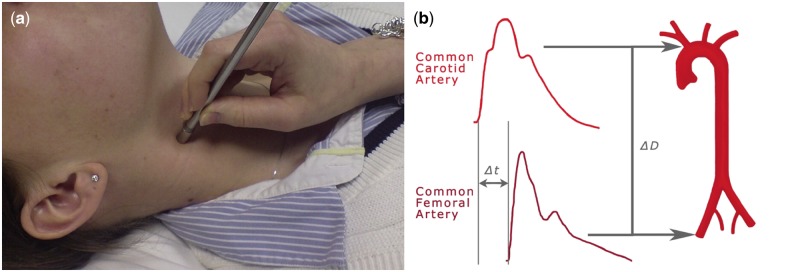

Commercial devices that measure aortic stiffness regionally are distinguished by the signal they detect (pressure, distension or flow), whether they identify waveforms at sites simultaneously and the use of electrocardiography (ECG) gating. The cfPWV is often measured using applanation tonometry, with the SpyghmoCor apparatus (AtCor Medical, Sydney, NSW, Australia) commonly used. The tonometer compresses the artery to record a waveform (Figure 2A); consecutive readings are taken at the carotid and femoral arteries using ECG gating to measure the time difference between arrival of the waveform upstroke at these points (Figure 2B) [38]. Doppler ultrasound is employed similarly using ultrasound transducers to take sequential or simultaneous readings at carotid and femoral sites. The Complior system (Colson, Les Lilas, France) uses mechanotransducers to detect waveforms. It is ECG independent, simultaneously recording the waveform at the two arterial points [48].

Fig. 2.

Applanation tonometry to calculate cfPWV. (a) Applanation tonometry at the carotid artery using a micromanometer. Reproduced from Wilkinson et al. [47]. (b) Calculation of cfPWV using the upstroke of the waveforms to define transit time. Δt, time difference in the arrival of the foot of the waveform; ΔD, distance.

As a regional measure, cfPWV includes parts of the femoral and iliac arteries, which have different elastic properties than the aorta. Furthermore, stiffening is not a homogeneous process; this is not accounted for in cfPWV measurement, which provides an average of compliance of the whole aorta [48]. Consequently, small patches of disease may be under-represented in the final calculation. Notably, it is not possible to obtain specific information about the ascending aorta, a prognostically important site [49].

CMR imaging to assess aortic stiffness

CV magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) proffers a comprehensive way to assess cardiac and arterial function in one investigation. It is the gold standard for quantification of LV dimensions and function [50]. CMR permits local measurement of aortic stiffness, allowing the effects of stiffening on different regions of the aorta to be discerned and inclusion of the ascending aorta in measurements [51]. Scanners apply varying magnetic fields and radiofrequency pulses to affect the magnetization properties of protons. Tissues are distinguished by the signals they emit in response and variations in pulses generate different images to highlight tissue characteristics [52]. Studies in ESRD have mostly used 1.5T platforms, but 3T platforms offer increased temporal and spatial resolution. Imaging at higher field strengths increases tissue distinction with less background noise, producing crisper images, but at the risk of amplifying artefacts [53]. Whether 3T platform imaging improves diagnostic accuracy has not been determined.

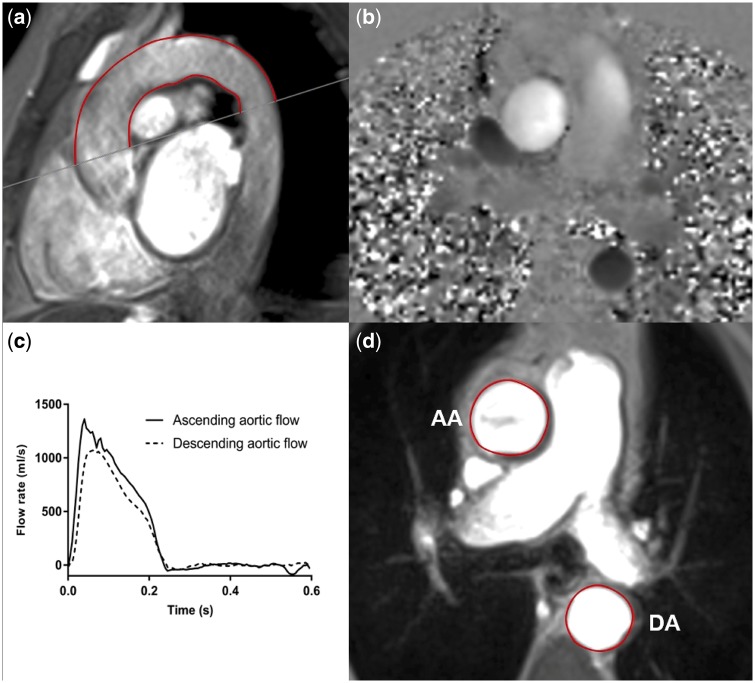

Figure 3 describes typical methods for calculating PWV and AD using images obtained by CMR [54]. Variations on these methods exist, dependent on the software utilized. For example, methods of calculating transit time can utilize velocity or flow curves; velocity is a measure of distance travelled over time, whereas flow rate refers to volume travelled over time. These vectors are generally proportional, and in fact, using either curve has been demonstrated not to influence aPWV values [55]. Different methods, however, can influence the reproducibility of results [55, 56]. These variations should be standardized before CMR-derived parameters can be considered viable biomarkers. Additionally, compared with regional methods, the time required for CMR image analysis is significant, although future software developments promise to improve this.

Fig. 3.

Assessment of aPWV and AD using two-dimensional phase contrast CMR. (a) For aPWV calculation, distance is measured using an oblique sagittal cine transecting the ascending and descending aorta. (b) Phase contrast sequences are contoured to derive (c) ascending and descending aortic flow curves, from which the temporal shift between the curves can be determined. This gives transit time (the time difference between waveform arrival at the ascending and descending aorta). AD is calculated from axial cine images, taken at the bifurcation of the pulmonary trunk, by contouring the change in (d) the aortic area and a PP measured simultaneously. AA, ascending aorta; DA, descending aorta.

Issues surrounding measurement techniques

Calculation of distance for PWV

Techniques that do not visualize the aorta may not accurately measure aortic length. Direct carotid–femoral measurement is known to overestimate distance, so adjusted calculations have been developed [38]. Unfortunately, the choice of calculation alone introduces up to 30% variation in cfPWV values [57] and studies that have employed different calculations of aortic length are not directly comparable, even if the same device was used. Additionally, the aorta becomes increasingly tortuous with age and variations in waist circumference may confound external measurements [38, 51]. In contrast, CMR enables visualization of the aorta (regardless of vessel angle or acoustic window) and direct measurement of length and accounts for anatomical variations [51]. A single sagittal oblique view of the aortic arch is used for the calculation of distance when measured with CMR. This is a limitation of the technique, as it does not facilitate visualization of aortic tortuosity in other planes. Nevertheless, this assumption aids simplicity in measurement and is unlikely to make a significant difference.

Measurement of BP for AD

Calculation of AD by CMR techniques requires external input of aortic pulse pressure (PP), usually substituted with values from non-invasive peripheral BP measurement; this is a potential limitation. Due to PP amplification, peripheral values are not representative of aortic PP and it is central pressure that is directly allied to cardiac workload [58]. Moreover, variability in amplification is marked with increasing aortic stiffness, which limits validity when comparing stiffness between groups if peripheral BP has been incorporated [59, 60]. It is difficult to isolate AD from PP as a causal factor behind clinical outcomes, since widened PP, due to arterial stiffening, has also been associated with mortality in ESRD [61]. Non-invasive oscillometric devices underestimate invasive brachial pressures by ∼10 mmHg [60]. Nevertheless, these devices are used in CMR studies to analyse the AD of CKD patients [34, 62].

Validation of methods

Neither regional nor CMR methods of measuring stiffness have been validated against invasive values in patients with renal disease.

Doppler, mechanotransducer and applanation tonometry measurements of aortic stiffness

Validation studies in cardiac patients have shown that Doppler correlates well with PWV derived from invasive catheterization (r = 0.93, mean difference = 0.13 ± 0.79 m/s) and with greater precision than results derived from Complior (r = 0.74) [63, 64]. Agreement between SpyghmoCor and invasive PWV varies by the method of distance measurement, with mean differences ranging from 3.3 (r = 0.77) to 0.2 m/s (r = 0.73) [65]. These validation studies are limited by using correlation coefficients, as strong correlations do not necessarily signify good agreement [66].

CMR measures of aortic stiffness

The aPWV derived from 1.5T CMR has been validated against invasive catheterization in patients with coronary heart disease, with good agreement between mean values [6.5 versus 6.1 m/s for MRI and invasive PWV coefficient of variation (CoV) 16%] [67]. AD is yet to be validated against invasive values.

Reproducibility of methods

Measurement of PWV and AD is operator dependent. An acceptable level of agreement within individual practices, between operators and between studies is needed for recognition as a reliable biomarker. Good reproducibility is especially important in patients with CKD and ESRD, where variations in BP, volume status and comorbidities may confound values.

Doppler, mechanotransducer and applanation tonometry measurements of aortic stiffness

The studies that have assessed the reproducibility of regional measures of aortic stiffness are of variable quality. Studies using Doppler in ESRD patients have reported intra-observer CoVs between 5.3 and 5.8% [68, 69]. Similarly, good interobserver variability has been reported for cfPWV, with an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.97 in a population of diabetic, hypertensive and CKD patients [70]. Mechanotransducer techniques have good intraobserver and inter-observer variability when used by experienced operators, with ICCs of 0.93 and 0.89 [71]. When applanation tonometry was applied to ESRD and healthy subjects, the ESRD cohort had an inter-observer variability of 0.87 and inter-study reproducibility of 0.83 [72]. Greater variation in mean operator differences existed for the controls than ESRD patients. Analysis of Bland–Altman plots revealed that one operator consistently overestimated cfPWV in the measurements of controls. The improved agreement between operators for ESRD results could be because this group was tested second. This reflects the experience needed by SpyghmoCor operators to obtain reproducible results.

CMR measures of aortic stiffness

No studies have assessed the interstudy repeatability of aPWV or AD in CKD patients. In patients with coronary heart disease, interstudy repeatability of aPWV measured by 1.5T CMR was good (ICC = 0.9) where examinations were repeated on the same day [67]. Similarly, interstudy repeatability at 3T using healthy volunteers was excellent (ICC = 0.96) [56]. However, when repeated examinations had a larger time difference (mean 13 days), interstudy repeatability decreased (ICC = 0.77) [73]. Inter- and intraobserver variability of aPWV measured at 1.5 and 3T has been excellent, with reported ICCs of 0.99 and 0.94, respectively [56, 73]. Regarding AD, a study involving CKD patients reported interobserver and intra-observer ICCs of 0.89 and 0.99, respectively [49]. The possibility to perform repeatable CMR analyses without extensive experience was supported by low interobserver variability (0.02 ± 0.38 m/s) despite a lack of operator experience [74].

Aortic stiffness in patients with CKD and ESRD

Doppler, mechanotransducer and applanation tonometry studies

Multiple studies using regional techniques have found increased cfPWV in CKD and ESRD patients compared with controls [68, 75–77], although the point where arterial stiffening becomes apparent is unclear. In a study of patients with CKD Stages 1–3, cfPWV was only significantly different from controls in patients with CKD Stage 3 [78]. Conversely, other study cohorts exhibit elevated cfPWV from early CKD [77, 79], although not all have shown an increasing trend of PWV with progression of disease [76]. There is also debate about whether higher cfPWV predicts incident CKD in the general population [80, 81].

Briet et al. [82] demonstrated that aortic stiffening in renal disease exceeds the effects of BP alone, as cfPWV in a CKD cohort was 7 and 19% higher than in hypertensive and normotensive subjects, respectively. The direct influence of HD on aortic stiffness, beyond the effects of advanced CKD and uremia, is not conclusive. One study suggested that aortic stiffness is greater in pre-dialysis patients than those on HD [83]. The assertion by investigators, however, that increased stiffness is related to uremia rather than HD itself may be misleading; PWV was measured in the HD group 2 h after dialysis. The reduction in cfPWV could reflect a transient improvement in volume and uremic status. Additionally, volume-overloaded pre-dialysis patients could have an increased cfPWV due to elevated stroke volume, though there are no good trial data to support this theory. The study’s cross-sectional design also introduces survivor bias, where patients with the highest PWV (and highest risk) may have died, leaving an HD cohort that is systematically healthier. This is an issue limiting most cross-sectional studies in these patients, as there is an escalation in mortality within the first 6 months of starting HD [84]. Other studies have noted increased cfPWV in HD compared with moderate CKD or over time [17, 18], although it is difficult to discriminate the effects of ageing and uremia from HD itself.

CMR studies

Studies have shown that AD is significantly decreased in CKD and dialysis patients compared with controls [49, 85–87]. PWV is increased in dialysis populations [86, 87] and one study revealed no significant difference in AD or aPWV between HD patients and patients with severe coronary artery disease [86]. An elegant study by Moody et al. [88] revealed that healthy donors developed increased aortic stiffness 1 year after donating a kidney, following the expected drop in glomerular filtration rate. This suggests that aortic stiffness is an early development and is related to CKD itself, as these patients were devoid of other CV risk factors. A randomized controlled trial on the effects of cooled dialysate suggests that aortic stiffness in ESRD might be modifiable [89]. AD significantly increased in control patients undergoing standard HD at 37 °C compared with patients who dialysed at 0.5 °C below body temperature. This was paralleled by a reduction in LV mass (LVM) and preservation of cardiac function in the intervention cohort, demonstrating the capacity of CMR to globally quantify the response of myocardium and vasculature to treatment [89].

Aortic stiffness and LVM in CKD and ESRD

LVH affects up to 75% of ESRD patients [90] and is an established marker for CV morbidity and mortality in the CKD population [91–93]. A reduction in LVM (with an associated reduction in aPWV) has been associated with improved survival in HD patients [94]. However, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis suggested there is no definitive relationship between intervention-related LVM reduction and improved mortality [95]. While LVM remains an important outcome measure, this highlights the value of assessing additional imaging biomarkers to strengthen existing risk stratification or endpoint measures. Table 2 summarizes the studies discussed.

Table 2.

Studies showing an association between LVM and aortic stiffness in patients with ESRD

| Author | Population | Age, mean ± SD (years); male sex (%) | Inclusion criteria | Study design | Modality (parameter) | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| London et al. [68] | 92 HD patients | 49.9 ± 15.9; 52 | •Not given | •Cross-sectional | •Doppler (cfPWV) Echo (LVM) | •LVM was increased in HD patients (246 ± 56 versus 198.4 ± 52 g, P = 0.0001) and correlated with aPWV (r = 0.576, P < 0.0001) |

| 90 controls | 50.8 ± 15.8 | |||||

| London et al. [96] | 138 HD patients | Responders: 48.2 ± 14.4; 60 Non-responders: 53.2 ± 17; 53 | •HD ≥ 3 months, pre-dialysis BP > 160/90, good quality echocardiography, follow-up ≥ 9 months | •Observational, 4.8-year mean follow-up | •Doppler (cfPWV) Echo (LVM) | •‘Responders’ were those whose cfPWV decreased in response to treatment. Decreased cfPWV correlated with reduced LVMI (r = 0.566, P < 0.001). Changes in cfPWV and LVM were independently correlated with serum CRP (P < 0.001) |

| Nitta et al. [11] | 49 HD patients | 60.4 ± 1.6, 55 | •HD ≥ 6 months | •Cross-sectional | •Mechano-transducer (brachial and tibial PWV) Echo (LVMI) | •LVMI correlated with PWV (r = 0.439, P = 0.001) |

| Kim et al. [97] | 391 incident HD patients | 54.7 ± 13.2; 59 | •HD patients: Age ≥18 years, enrolled within 6 months of HD initiation | •Cross-sectional | •Applanation tonometry (cfPWV) Echo (LVMI) | •Univariate regression (a) and multivariate regression (b) showed no significant relationship between PWV and LVMI: (a) β = −0.42 (−1.78, 0.94), P = 0.55; (b) β = 0.19 (−1.41, 1.79), P = 0.82. |

| Edwards et al. [34] | 117 patients with Stage 2–3 CKD | CKD 2: 55.9 ± 11.6; 50 CKD Stage 3: 53.8 ± 11.8; 68 | •18–80 years, Stage 2 or 3 CKD. No overt CVD, DM or PVD | •Cross-sectional | •1.5T CMR (AD and LVM) | •LVM was inversely correlated with AD (r = −0.284, P < 0.001) |

| 40 controls | 50.3 ± 9.2; 50 |

HD, haemodialysis; LVM, left ventricular mass; LVMI, left ventricular mass index; CRP, C-reactive protein; parametric data presented as mean ± SD.

The association between aortic stiffness and LVH in CKD and ESRD is not only described in clinical studies, but is also emphasized by biological plausibility. Chronic volume overload in CKD leads to eccentric cardiac hypertrophy, while pressure overload due to arterial stiffness and hypertension accounts for concentric hypertrophy. Concentric remodelling describes thickening of the LV wall and is defined by an elevated LVM:volume ratio. In patients with ESRD, it independently predicts CV risk beyond the ability of LVH [98]. The loss of the aorta’s buffering action on BP subjects the myocardium to higher systolic pressures, haemodynamic instability and increased LV workload. Subsequent compensatory hypertrophic responses result in increased oxygen demand, impaired relaxation and contraction and interstitial fibrosis [99]. Widening of PP due to aortic stiffening also impairs diastolic coronary filling, exacerbating ischaemia in a progressively fibrotic and hypertrophied myocardium [8]. This may also aggravate HD-associated cardiac ischaemia, suggested by the inverse relationship between AD and troponin-T [87].

LVM increases with worsening AD in patients with CKD [34] and reductions in AD have been correlated with concentric LV remodelling [87]. Edwards et al. [34] also demonstrated that while there was an increase in the absolute values of aortic stiffness and LV elastance in early CKD, the arterial–ventricular coupling ratio was preserved. This suggests that aortic stiffness drives an increase in LV contractility and this initial response maintains the coupling ratio. However, this compensation is short-lived and impaired diastolic relaxation and LVH followed. While some studies show a positive relationship between aPWV and LVM [68], others have found no relationship [97], although this latter study was of younger, incident HD patients rather than the prevalent populations comprising other studies [11, 68, 87, 100]. Furthermore, an interventional study in HD patients by London et al. [96] indicated that reductions in LVM in response to treatment for hypertension and anaemia correlated with reductions in cfPWV (r = 0.566, P < 0.001).

Aortic stiffness and CV mortality in CKD and ESRD

Increased PWV is a robust, independent predictor of CV mortality in patients with CKD and ESRD [45, 100, 101–106]. There are data regarding AD, but its predictive power has been assessed in CKD patients [62]. A meta-analysis of 27 studies in healthy and disease populations found a 1-SD increase in cfPWV conferred close to a 50% increased risk of CV death. Furthermore, cfPWV was a better predictor of outcome in higher-risk individuals (such as those with ESRD) than in the general population [107, 108]. Table 3 describes studies that have evaluated the relationship between arterial stiffness and mortality.

Table 3.

Studies demonstrating the association between aortic stiffness and CV mortality assessed by Doppler, mechanotransducer, applanation tonometry and CMR

| Author | Population | Age, mean ± SD (years); male sex (%) | Inclusion criteria | Study design | Modality (parameter) | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blacher et al. [100] | 241 ESRD patients | 51.5 ± 16.3; 61 | •On HD ≥ 3 months, no pre-existing clinical CVD | •Observational, 6-year mean follow-up | •Doppler ultrasound (cfPWV) |

|

| Guerin et al. [101] | 150 ESRD patients | 52 ± 16; 60 | •On HD ≥ 3 months, no clinical CVD preceding | •Prospective cohort, 4.3-year mean follow-up | •Doppler ultrasound (cfPWV) | •Adjusted RR for CV mortality in non-responders was 2.35 (95% CI 1.23–4.51, P < 0.01) compared with responders. For a 1 m/s decrease in PWV in response to BP, RR = 0.79 (95% CI 0.69–0.93) for CV mortality |

| Shoji et al. [102] | 265 ESRD patients (50 had type 2 DM) | 55.4 ± 10.5; 41 | •On HD ≥ 3 months | •Observational, 5-year mean follow-up | •Mechano-transducer (cfPWV) | •Increased cfPWV (per 1m/s) strongly predicted CV mortality: HR = 1.16 (95% CI 1.0–1.36, P < 0.05), independent of diabetic status |

| Zoungas et al. [45] | 315 Stages 4–5 CKD patientsa | 55 ± 13; 67 | •Age >18 years, defined CKD, dialysis therapy to start ≤6 months or already established | •Observational, 5.3-year mean follow-up | •Applanation tonometry (cfPWV) |

|

| Mark et al. [62] | 144 CKD patients (110 on dialysis)b | 51.5 ± 11.2; 62 | •CKD: eGFR <15 mL/min/ 1.73 m2 | •Prospective observational, 2-year median follow-up | •1.5T CMR (AD) | •AD was associated with CV mortality: HR = 0.135 (95% CI 0.019–0.948, P = 0.044), although diabetes had a stronger association (HR = 4.2) |

| Verbeke et al. [103] | 1084 dialysis patients | 68.1; 59 | •Age ≥18 years, on HD/PD ≥3 months | •Observational, 2-year follow-up | •Applanation tonometry (cfPWV) | •A PWV >12 m/s gave an HR = 1.94 (95% CI 1.38–2.73). Increased cfPWV (per 1 m/s) gave an HR = 1.15 (95% CI 1.09–1.23, P < 0.001) for CV mortality |

| Karras et al. [104] | 439 CKD patients | 59.8 ± 14.5; 74 | •Stages 3–5 CKD, not yet on dialysis | •Prospective observational, 4.7-year mean follow-up | •Mechano-transducer (cfPWV) | •Increased cfPWV (per 1 SD) gave an RR = 1.35 (95% CI 1.05–1.75, P = 0.021) for fatal and non-fatal CV events |

| Baumann et al. [105] | 135 CKD patients | 59.2 ± 15.1; 46 | •Stages 2–4 CKD | •Prospective observational, 3.7-year mean follow-up | •Oscillometric method (PWV) | •PWV >10 m/s gave an OR = 5.1 (95% CI 1.1–22.9, P < 0.05) |

| Sulemane et al. [106] | 106 CKD patients | 55.9 ± 2.8; 51 | •No overt CVD, normal LV ejection fraction, not on HD | •Prospective observational, 4-year median follow-up | •Applanation tonometry (cfPWV) | •Increased cfPWV (per 1 m/s) gave an HR = 1.31 (95% CI 1.05–1.41, P = 0.021) |

HD, haemodialysis; DM, diabetes mellitus; HR, hazard ratio; OR, odds ratio; RR, risk ratio; 95% confidence intervals presented in brackets.

207 had cfPWV assessment.

122 patients had AD analysed.

Doppler, mechanotransducer and applanation tonometry studies

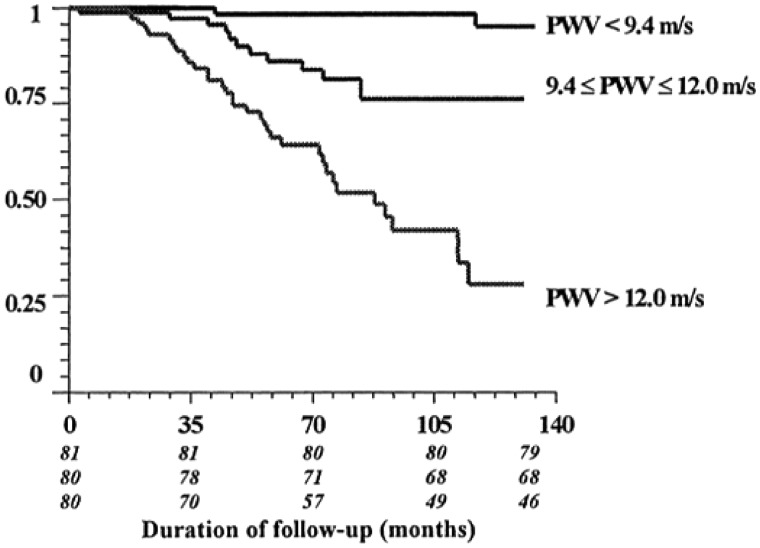

A seminal paper by Blacher et al. [100] demonstrated the ability of Doppler-calculated cfPWV to predict CV mortality, despite adjustment for common prognostic variables (Figure 4). The oft-quoted 39% increased risk of all-cause mortality for each 1-m/s increase in PWV [100] has been emulated in studies involving populations across the spectrum of CKD; they demonstrate that a 1-m/s or 1-SD increase in cfPWV is independently associated with increased risk of CV mortality [45, 102–106] (Table 3). The concept that accurate measurement of aortic stiffness may serve as an early biomarker of CV risk was underscored in a CKD cohort with no clinical or echocardiographic evidence of CVD [106]; a 1-m/s elevation in cfPWV still gave a 30% increased risk of major CV event over the 49-month follow-up. Akin to previous findings, cfPWV was a stronger indicator of risk in more advanced CKD stages, although the low event rate in the early CKD group influences this result.

Fig. 4.

Kaplan–Meier survival curve for CV deaths in an ESRD study population separated into tertiles based on cfPWV. Reproduced from Blacher et al. [100].

There is evidence that improving aortic stiffness improves mortality in patients with ESRD. HD patients whose cfPWV failed to improve following modification of BP had an increased relative risk ratio for all-cause mortality of 2.59 [95% confidence interval (CI) 1.51–4.43] and for CV mortality of 2.35 (95% CI 1.23–4.41) compared with HD patients whose cfPWV improved with BP modification [101]. While an interesting observation, there was no apparent correction for differences in baseline cfPWV, and the study cannot prove a direct and causal relationship between cfPWV modification and improved survival.

CMR studies

A CMR study in CKD and HD patients showed decreased AD predisposed to CV mortality [62]. In Cox regression analysis, diabetes, systolic BP and AD were independent predictors of survival. Results were similar between pre-dialysis and dialysis groups, and in keeping with accepted thinking about ageing and arterial elasticity, AD decreased with age. Despite this, neither age nor HD vintage was associated with CV outcome, implying that it is vascular ageing rather than temporal ageing that affects outcomes. There are no CMR studies that have reported aPWV and mortality in patients with renal disease.

Conclusions

CV risk assessment using conventional risk factor models is imprecise in CKD and ESRD. Applying the Framingham score in CKD patients underestimates CV events, predicting only 13.9% (in men) and 4.8% (in women) of events over 10 years [109]. Identifying and quantifying new biomarkers that translate into clinical practice may improve the prediction of CV risk in these patients. Measurement of aortic stiffness is one such biomarker. It encompasses the known and unknown elements of arteriopathy that contribute to increased CV burden. Practical understanding of its significance has been helped by establishing normal cfPWV and CMR-derived values in the general population [28, 110]. The amenability of aortic stiffness to interventions and its translation into outcomes needs further exploration.

An accurate, reliable measure of aortic stiffness is vital for its application to the real world. Choice of technique can lead to up to 40% variance in patient CV risk stratification [111]. An ideal method would (i) measure aortic stiffness directly and non-invasively, (ii) be validated in clinical studies across patient groups, (iii) provide useful information about an individual patient’s current health and future risk, (iv) assess secondary effects on the heart, and (v) be acceptable to clinicians and patients. Recent advances mean that CMR has the potential to follow these stipulations, but further studies in renal disease are needed to investigate the significance of CMR-derived values. The ease of measuring local aortic stiffness within routine imaging and the ability to concurrently track a variety of other cardiac parameters adds to the advantages of CMR. While imaging is relatively operator independent, analysis software and techniques require standardizing. Improvement of machine-learning capabilities could improve reproducibility and streamline the process.

The relationship between aortic stiffness and CV health in CKD and ESRD has been substantiated through application of regional cfPWV methods and, most recently, through local measurement of aPWV and AD by CMR. Although improvements are necessary, local assessment could represent a step towards more precise evaluation of the arterial–ventricular relationship. Whether CMR techniques can be established to the same standards as regional methods is to be seen. A logical step may be to directly compare regional and CMR-derived measurements in a CKD population to quantify agreement.

Authors’ contributions

S.F.A.: manuscript draft, figure preparation, final preparation.

M.P.M.G.B.: manuscript revision, final preparation.

F.M.T.L.: figure creation and preparation.

J.O.B.: manuscript revision.

G.P.M.: revision and final approval of manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Funding

S.F.A received a Wolfson Intercalated Award, administered by the Royal College of Physicians. M.P.M.G.B is a Doctoral Research Fellow at the National Centre for Sport and Exercise Medicine, Loughborough University. J.O.B is funded by a Clinician Scientist Award (CS-2013-13-014) supported by the NIHR. G.P.M is funded by an NIHR Career Development Fellowship (NIHR-CDF 2014-07-045).

References

- 1. Sarnak MJ, Levey AS, Schoolwerth AC. et al. Kidney disease as a risk factor for development of cardiovascular disease a statement from the American Heart Association Councils on kidney in cardiovascular disease, high blood pressure research, clinical cardiology, and epidemiology and prevention. Circulation 2003; 108: 2154–2169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases 2015 USRDS Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States. Bethesda, MD: United States Renal Data System, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Menon V, Gul A, Sarnak MJ.. Cardiovascular risk factors in chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 2005; 68: 1413–1418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Herzog CA, Strief JW, Collins AJ. et al. Cause-specific mortality of dialysis patients after coronary revascularization: why don’t dialysis patients have better survival after coronary intervention? Nephrol Dial Transplant 2008; 23: 2629–2633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schiffrin EL, Lipman ML, Mann JFE.. Chronic kidney disease: effects on the cardiovascular system. Circulation 2007; 116: 85–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Breidthardt T, McIntyre CW.. Dialysis-induced myocardial stunning: the other side of the cardiorenal syndrome. Rev Cardiovasc Med 2010; 12: 13–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gross M, Ritz E.. Hypertrophy and fibrosis in the cardiomyopathy of uremia-beyond coronary heart disease. Semin Dial 2008; 21: 308–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Moody WE, Edwards NC, Chue CD. et al. Arterial disease in chronic kidney disease. Heart 2013; 99: 365–372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lee RT, Kamm RD.. Vascular mechanics for the cardiologist. J Am Coll Cardiol 1994; 23: 1289–1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. O'Rourke MF, Safar ME.. Relationship between aortic stiffening and microvascular disease in brain and kidney: cause and logic of therapy. Hypertension 2005; 46: 200–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nitta K, Akiba T, Uchida K. et al. Left ventricular hypertrophy is associated with arterial stiffness and vascular calcification in hemodialysis patients. Hypertens Res 2004; 27: 47–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. McEniery CM, Hall IR. et al. Normal vascular aging: differential effects on wave reflection and aortic pulse wave velocity: the Anglo-Cardiff Collaborative Trial (ACCT). J Am Coll Cardiol 2005; 46: 1753–1760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mitchell GF, Parise H, Benjamin EJ. et al. Changes in arterial stiffness and wave reflection with advancing age in healthy men and women: the Framingham Heart Study. Hypertension 2004; 43: 1239–1245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Redheuil A, Yu W, Wu CO. et al. Reduced ascending aortic strain and distensibility earliest manifestations of vascular aging in humans. Hypertension 2010; 55: 319–326 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Malayeri AA. Relation of aortic wall thickness and distensibility to cardiovascular risk factors (from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis [MESA]). Am J Cardiol 2008; 102: 491–496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Niiranen TJ, Kalesan B, Hamburg NM. et al. Relative contributions of arterial stiffness and hypertension to cardiovascular disease: the Framingham Heart Study. J Am Heart Assoc 2016; 5: 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Utescu MS, Couture V, Mac-Way F. et al. Determinants of progression of aortic stiffness in hemodialysis patients a prospective longitudinal study. Hypertension 2013; 62: 154–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wang M, Tsai W, Chen J. et al. Stepwise increase in arterial stiffness corresponding with the stages of chronic kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis 2005; 45: 494–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Taniwaki H, Kawagishi T, Emoto M. et al. Correlation between the intima-media thickness of the carotid artery and aortic pulse-wave velocity in patients with type 2 diabetes. Vessel wall properties in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 1999; 22: 1851–1857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. van der Meer RW, Diamant M, Westenberg JJM. et al. Magnetic resonance assessment of aortic pulse wave velocity, aortic distensibility, and cardiac function in uncomplicated type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Cardiovasc Magnet Reson 2007; 9: 645–651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. van Popele NM, Grobbee DE, Bots ML. et al. Association between arterial stiffness and atherosclerosis: the Rotterdam Study. Stroke 2001; 32: 454–460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sutton-Tyrrell K, Najjar SS, Boudreau RM. et al. Elevated aortic pulse wave velocity, a marker of arterial stiffness, predicts cardiovascular events in well-functioning older adults. Circulation 2005; 111: 3384–3390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wildman RP, Mackey RH, Bostom A. et al. Measures of obesity are associated with vascular stiffness in young and older adults. Hypertension 2003; 42: 468–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ferreira I, Henry RMA, Twisk JWR. et al. The metabolic syndrome, cardiopulmonary fitness, and subcutaneous trunk fat as independent determinants of arterial stiffness: the Amsterdam Growth and Health Longitudinal Study. Arch Intern Med 2005; 165: 875–882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Waddell TK, Dart AM, Gatzka CD. et al. Women exhibit a greater age-related increase in proximal aortic stiffness than men. J Hypertens 2001; 19: 2205–2212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rose JL, Lalande A, Bouchot O. et al. Influence of age and sex on aortic distensibility assessed by MRI in healthy subjects. Magn Reson Imaging 2010; 28: 255–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Vermeersch SJ, Rietzschel ER, De Buyzere ML. et al. Age and gender related patterns in carotid-femoral PWV and carotid and femoral stiffness in a large healthy, middle-aged population. J Hypertens 2008; 26: 1411–1419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mattace-Raso FUS, Hofman A, Verwoert GC. et al. Determinants of pulse wave velocity in healthy people and in the presence of cardiovascular risk factors: establishing normal and reference values. Eur Heart J 2010; 31: 2338–2350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Goel A, Maroules CD, Mitchell GF. et al. Ethnic difference in proximal aortic stiffness: an observation from the Dallas Heart Study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2017; 10: 54–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Palmer SC, Craig JC, Navaneethan SD. et al. Benefits and harms of statin therapy for persons with chronic kidney disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2012; 157: 263–275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Baigent C, Landray MJ, Reith C. et al. The effects of lowering LDL cholesterol with simvastatin plus ezetimibe in patients with chronic kidney disease (Study of Heart and Renal Protection): a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2011; 377: 2181–2192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wetmore JB, Shireman TI.. The ABCs of cardioprotection in dialysis patients: a systematic review. Am J Kidney Dis 2009; 53: 457–466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Taal MW, Sigrist MK, Fakis A. et al. Markers of arterial stiffness are risk factors for progression to end-stage renal disease among patients with chronic kidney disease stages 4 and 5. Nephron Clin Pract 2007; 107: c177–c181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Edwards NC, Ferro CJ, Townend JN. et al. Aortic distensibility and arterial-ventricular coupling in early chronic kidney disease: a pattern resembling heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Heart 2008; 94: 1038–1043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Reneman RS, Meinders JM, Hoeks AP.. Non-invasive ultrasound in arterial wall dynamics in humans: what have we learned and what remains to be solved. Eur Heart J 2005; 26: 960–966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bramwell JC, Hill AV.. The velocity of the pulse wave in man. Proc R Soc B 1922; 93: 298–306 [Google Scholar]

- 37. Baksi AJ, Treibel TA, Davies JE. et al. A meta-analysis of the mechanism of blood pressure change with aging. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009; 54: 2087–2092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Laurent S, Cockcroft J, Van Bortel L. et al. Expert consensus document on arterial stiffness: methodological issues and clinical applications. Eur Heart J 2006; 27: 2588–2605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mattace-Raso FU, van der Cammen TJM, Hofman A. et al. Arterial stiffness and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke the rotterdam study. Circulation 2006; 113: 657–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mitchell GF, Hwang S, Vasan RS. et al. Arterial stiffness and cardiovascular events: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2010; 121: 505–511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Groothoff JW, Gruppen MP, Offringa M. et al. Increased arterial stiffness in young adults with end-stage renal disease since childhood. J Am Soc Nephrol 2002; 13: 2953–2961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lehmann ED, Parker JR, Hopkins KD. et al. Validation and reproducibility of pressure-corrected aortic distensibility measurements using pulse-wave-velocity Doppler ultrasound. J Biomed Eng 1993; 15: 221–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Vlachopoulos C, Aznaouridis K, Terentes-Printzios D. et al. Prediction of cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality with brachial-ankle elasticity index a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hypertension 2012; 60: 556–562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Pannier B, Guerin AP, Marchais SJ. et al. Stiffness of capacitive and conduit arteries: prognostic significance for end-stage renal disease patients. Hypertension 2005; 45: 592–596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Zoungas S, Cameron JD, Kerr PG. et al. Association of carotid intima-media thickness and indices of arterial stiffness with cardiovascular disease outcomes in CKD. Am J Kidney Dis 2007; 50: 622–630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Covic A, Mardare N, Gusbeth-Tatomir P. et al. Arterial wave reflections and mortality in haemodialysis patients—only relevant in elderly, cardiovascularly compromised? Nephrol Dial Transplant 2006; 21: 2859–2866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Wilkinson IB, McEniery CM, Schillaci G. et al. ARTERY Society guidelines for validation of non-invasive haemodynamic measurement devices: part 1, arterial pulse wave velocity. Artery Res 2010; 4: 34–40 [Google Scholar]

- 48. Pereira T, Correia C, Cardoso J.. Novel methods for pulse wave velocity measurement. J Med Biol Eng 2015; 35: 555–565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Chue CD, Edwards NC, Ferro CJ. et al. Effects of age and chronic kidney disease on regional aortic distensibility: a cardiovascular magnetic resonance study. Int J Cardiol 2013; 168: 4249–4254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Bellenger NG, Burgess MI, Ray SG. et al. Comparison of left ventricular ejection fraction and volumes in heart failure by echocardiography, radionuclide ventriculography and cardiovascular magnetic resonance. Are they interchangeable? Eur Heart J 2000; 21: 1387–1396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Cavalcante JL, Lima JA, Redheuil A. et al. Aortic stiffness: current understanding and future directions. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011; 57: 1511–1522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ridgway JP. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance physics for clinicians: part I. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2010; 12: 1–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Oshinski JN, Delfino JG, Sharma P. et al. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance at 3.0 T: current state of the art. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2010; 12: 55–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Wentland AL, Grist TM, Wieben O.. Review of MRI-based measurements of pulse wave velocity: a biomarker of arterial stiffness. Cardiovasc Diag Ther 2014; 4: 193–206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Dogui A, Redheuil A, Lefort M. et al. Measurement of aortic arch pulse wave velocity in cardiovascular MR: comparison of transit time estimators and description of a new approach. J Magn Reson Imaging 2011; 33: 1321–1329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Ibrahim EH, Johnson KR, Miller AB. et al. Measuring aortic pulse wave velocity using high-field cardiovascular magnetic resonance: comparison of techniques. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2010; 12: 26–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Rajzer MW, Wojciechowska W, Klocek M. et al. Comparison of aortic pulse wave velocity measured by three techniques: Complior, SphygmoCor and Arteriograph. J Hypertens 2008; 26: 2001–2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Mackenzie IS, Wilkinson IB, Cockcroft JR.. Assessment of arterial stiffness in clinical practice. QJM 2002; 95: 67–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Briet M, Boutouyrie P, Laurent S. et al. Arterial stiffness and pulse pressure in CKD and ESRD. Kidney Int 2012; 82: 388–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. McEniery CM, Cockcroft JR, Roman MJ. et al. Central blood pressure: current evidence and clinical importance. Eur Heart J 2014; 35: 1719–1725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Safar ME, Blacher J, Pannier B. et al. Central pulse pressure and mortality in end-stage renal disease. Hypertension 2002; 39: 735–738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Mark PB, Doyle A, Blyth KG. et al. Vascular function assessed with cardiovascular magnetic resonance predicts survival in patients with advanced chronic kidney disease. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2008; 10: 39–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Styczynski G, Rdzanek A, Pietrasik A. et al. Echocardiographic assessment of aortic pulse-wave velocity: validation against invasive pressure measurements . J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2016; 29: 1109–1116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Podolec P, Kopeć G, Podolec J. et al. Aortic pulse wave velocity and carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity: similarities and discrepancies. Hypertens Res 2007; 30: 1151–1158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Weber T, Ammer M, Rammer M. et al. Noninvasive determination of carotid–femoral pulse wave velocity depends critically on assessment of travel distance: a comparison with invasive measurement. J Hypertens 2009; 27: 1624–1630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Bland JM, Altman D.. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet 1986; 327: 307–310 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Grotenhuis HB, Westenberg JJ, Steendijk P. et al. Validation and reproducibility of aortic pulse wave velocity as assessed with velocity‐encoded MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging 2009; 30: 521–526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. London GM, Marchais SJ, Safar ME. et al. Aortic and large artery compliance in end-stage renal failure. Kidney Int 1990; 37: 137–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Blacher J, Guerin AP, Pannier B. et al. Arterial calcifications, arterial stiffness, and cardiovascular risk in end-stage renal disease. Hypertension 2001; 38: 938–942 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Calabia J, Torguet P, Garcia M. et al. Doppler ultrasound in the measurement of pulse wave velocity: agreement with the Complior method. Cardiovasc Ultrasound 2011; 9: 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Asmar R, Benetos A, Topouchian J. et al. Assessment of arterial distensibility by automatic pulse wave velocity measurement validation and clinical application studies. Hypertension 1995; 26: 485–490 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Rodriguez RA, Cronin V, Ramsay T. et al. Reproducibility of carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity in end-stage renal disease patients: methodological considerations. Can J Kidney Health Dis 2016; 3: 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Noda C, Venkatesh BA, Ohyama Y. et al. Reproducibility of functional aortic analysis using magnetic resonance imaging: the MESA. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2016; 17: 909–917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Dorniak K, Heiberg E, Hellmann M. et al. Required temporal resolution for accurate thoracic aortic pulse wave velocity measurements by phase-contrast magnetic resonance imaging and comparison with clinical standard applanation tonometry. BMC Cardiovasc Disorders 2016; 16: 110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. London GM, Guerin AP, Marchais SJ. et al. Cardiac and arterial interactions in end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int 1996; 50: 600–608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Temmar M, Liabeuf S, Renard C. et al. Pulse wave velocity and vascular calcification at different stages of chronic kidney disease. J Hypertens 2010; 28: 163–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Lilitkarntakul P, Dhaun N, Melville V. et al. Blood pressure and not uraemia is the major determinant of arterial stiffness and endothelial dysfunction in patients with chronic kidney disease and minimal co-morbidity. Atherosclerosis 2011; 216: 217–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Pluta A, Stróżecki P, Krintus M. et al. Left ventricular remodeling and arterial remodeling in patients with chronic kidney disease stage 1–3. Ren Fail 2015; 37: 1105–1110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Essig M, Escoubet B, de Zuttere D. et al. Cardiovascular remodelling and extracellular fluid excess in early stages of chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2008; 23: 239–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Madero M, Peralta C, Katz R. et al. Association of arterial rigidity with incident kidney disease and kidney function decline: the Health ABC Study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2013; 8: 424–433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Upadhyay A, Hwang S, Mitchell GF. et al. Arterial stiffness in mild-to-moderate CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 2009; 20: 2044–2053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Briet M, Bozec E, Laurent S. et al. Arterial stiffness and enlargement in mild-to-moderate chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 2006; 69: 350–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Shinohara K, Shoji T, Tsujimoto Y. et al. Arterial stiffness in predialysis patients with uremia. Kidney Int 2004; 65: 936–943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Lukowsky LR, Kheifets L, Arah OA. et al. Patterns and predictors of early mortality in incident hemodialysis patients: new insights. Am J Nephrol 2012; 35: 548–558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Doyle A, Mark PB, Johnston N. et al. Aortic stiffness and diastolic flow abnormalities in end-stage renal disease assessed by magnetic resonance imaging. Nephron Clin Pract 2008; 109: c1–c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Zimmerli LU, Mark PB, Steedman T. et al. Vascular function in patients with end-stage renal disease and/or coronary artery disease: a cardiac magnetic resonance imaging study. Kidney Int 2007; 71: 68–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Odudu A, Eldehni MT, McCann GP. et al. Characterisation of cardiomyopathy by cardiac and aortic magnetic resonance in patients new to hemodialysis. Eur Radiol 2016: 26: 2749–2761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Moody WE, Ferro CJ, Edwards NC. et al. Cardiovascular effects of unilateral nephrectomy in living kidney donors. Hypertension 2016; 67: 368–377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Odudu A, Eldehni MT, McCann GP. et al. Randomized controlled trial of individualized dialysate cooling for cardiac protection in hemodialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2015; 10: 1408–1417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Foley RN, Parfrey PS, Harnett JD. et al. Clinical and echocardiographic disease in patients starting end-stage renal disease therapy. Kidney Int 1995; 47: 186–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Weiner DE, Tighiouart H, Vlagopoulos PT. et al. Effects of anemia and left ventricular hypertrophy on cardiovascular disease in patients with chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2005; 16: 1803–1810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Silberberg JS, Barre PE, Prichard SS. et al. Impact of left ventricular hypertrophy on survival in end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int 1989; 36: 286–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Zoccali C, Benedetto FA, Mallamaci F. et al. Left ventricular mass monitoring in the follow-up of dialysis patients: prognostic value of left ventricular hypertrophy progression. Kidney Int 2004; 65: 1492–1498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. London GM, Pannier B, Guerin AP. et al. Alterations of left ventricular hypertrophy in and survival of patients receiving hemodialysis: follow-up of an interventional study. J Am Soc Nephrol 2001; 12: 2759–2767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Badve SV, Palmer SC, Strippoli GFM. et al. The validity of left ventricular mass as a surrogate end point for all-cause and cardiovascular mortality outcomes in people with CKD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Kidney Dis 2016; 68: 554–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. London GM, Marchais SJ, Guerin AP. et al. Inflammation, arteriosclerosis, and cardiovascular therapy in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int 2003; 63(Suppl 84): S88–S93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Kim ED, Sozio SM, Estrella MM. et al. Cross-sectional association of volume, blood pressures, and aortic stiffness with left ventricular mass in incident hemodialysis patients: the Predictors of Arrhythmic and Cardiovascular Risk in End-Stage Renal Disease (PACE) Study. BMC Nephrol 2015; 16: 131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Foley RN, Parfrey PS, Harnett JD. et al. The prognostic importance of left ventricular geometry in uremic cardiomyopathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 1995; 5: 2024–2031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. London GM. Left ventricular alterations and end‐stage renal disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2002; 17(Suppl 1): 29–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Blacher J, Guerin AP, Pannier B. et al. Impact of aortic stiffness on survival in end-stage renal disease. Circulation 1999; 99: 2434–2439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Guerin AP, Blacher J, Pannier B. et al. Impact of aortic stiffness attenuation on survival of patients in end-stage renal failure. Circulation 2001; 103: 987–992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Shoji T, Emoto M, Shinohara K. et al. Diabetes mellitus, aortic stiffness, and cardiovascular mortality in end-stage renal disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 2001; 12: 2117–2124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Verbeke F, Van Biesen W, Honkanen E. et al. Prognostic value of aortic stiffness and calcification for cardiovascular events and mortality in dialysis patients: outcome of the calcification outcome in renal disease (CORD) study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2011; 6: 153–159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Karras A, Haymann J, Bozec E. et al. Large artery stiffening and remodeling are independently associated with all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events in chronic kidney disease. Hypertension 2012; 60: 1451–1457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Baumann M, Wassertheurer S, Suttmann Y. et al. Aortic pulse wave velocity predicts mortality in chronic kidney disease stages 2–4. J Hypertens 2014; 32: 899–903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Sulemane S, Panoulas VF, Bratsas A. et al. Subclinical markers of cardiovascular disease predict adverse outcomes in chronic kidney disease patients with normal left ventricular ejection fraction. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2017; 33: 687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Vlachopoulos C, Aznaouridis K, Stefanadis C.. Prediction of cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality with arterial stiffness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010; 55: 1318–1327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Vlachopoulos C, Aznaouridis K, Stefanadis C.. Aortic stiffness for cardiovascular risk prediction: just measure it, just do it! J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 63: 647–649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Weiner DE, Tighiouart H, Elsayed EF. et al. The Framingham predictive instrument in chronic kidney disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007; 50: 217–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Kawel-Boehm N, Maceira A, Valsangiacomo-Buechel ER. et al. Normal values for cardiovascular magnetic resonance in adults and children. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2015; 17: 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Pichler G, Martinez F, Vicente A. et al. Carotid–femoral pulse wave velocity assessment by two different methods: implications for risk assessment. J Hypertens 2015; 33: 1868–1875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]