Abstract

Previous researchers have found that 10-form Tai chi yields symptomatic benefit in patients with fibromyalgia (FM). The purpose of this study was to further investigate earlier findings and add a focus on functional mobility. We conducted a parallel-group randomized controlled trial FM-modified 8-form Yang-style Tai chi program compared to an education control. Participants met in small groups twice weekly for 90 min over 12 weeks. The primary endpoint was symptom reduction and improvement in self-report physical function, as measured by the Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ), from baseline to 12 weeks. Secondary endpoints included pain severity and interference (Brief Pain Inventory (BPI), sleep (Pittsburg sleep Inventory), self-efficacy, and functional mobility. Of the 101 randomly assigned subjects (mean age 54 years, 93 % female), those in the Tai chi condition compared with the education condition demonstrated clinically and statistically significant improvements in FIQ scores (16.5 vs. 3.1, p=0.0002), BPI pain severity (1.2 vs. 0.4, p=0.0008), BPI pain interference (2.1 vs. 0.6, p=0.0000), sleep (2.0 vs. −0.03, p=0.0003), and self-efficacy for pain control (9.2 vs. −1.5, p=0.0001). Functional mobility variables including timed get up and go (−.9 vs. −.3, p=0.0001), static balance (7.5 vs. −0.3, p= 0.0001), and dynamic balance (1.6 vs. 0.3, p=0.0001) were significantly improved with Tai chi compared with education control. No adverse events were noted. Twelve weeks of Tai chi, practice twice weekly, provided worthwhile improvement in common FM symptoms including pain and physical function including mobility. Tai chi appears to be a safe and an acceptable exercise modality that may be useful as adjunctive therapy in the management of FM patients. (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier, NCT01311427)

Keywords: Fibromyalgia, Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire, Functional mobility, Symptom management, Tai chi

Fibromyalgia (FM) is a common, multisymptomatic chronic pain illness with significant functional mobility limitations. People with FM suffer from widespread musculoskeletal pain, fatigue, stiffness, disturbed sleep, and declining physical function. The societal burden is substantial, with medical expenditures two to three times higher than in other chronic illness comparison groups; annual costs exceeding $20 billion and an 8:1 female to male predisposition [1, 2]. The prevailing treatment approach is a combination of pharmacological treatments for specific symptoms, coupled with recommendations involving education, lifestyle change, self-help, and exercise [3–5].

Existent FM literature indicates that higher intensity exercise programs, regardless of mode, result in improved physical fitness, but often worsen pain, induce a symptom flare, reduce self-efficacy, and have little or no effect on sleep [6, 7]. Clinicians, therefore, may not wish to encourage FM patients to initiate a conventional exercise program. Recently, exercise that employs a mind/body component has been found to be effective for reducing FM symptoms [8]. Tai chi is a mind/body exercise that differs from conventional exercise programs that focus exclusively on physical fitness (e.g., aerobics training) in that the mind (psychological) and body (physical) are an integrated, unified whole. Tai chi combines slow, graceful, purposeful movements with controlled breathing and relaxation. As a form of ancient Chinese martial arts, Tai chi’s mechanism of action is purported to appropriately distribute the body’s vital energy, termed “qi.” Tai chi can be easily modified to account for the central and peripheral dysfunctions associated with FM. The practice is progressive in intensity, timing, and type of physical and mental challenge [9]. Tai chi has gained popularity in the USA and has been demonstrated to be effective in elders or persons with painful musculoskeletal disorders including rheumatoid and osteoarthritis [10–12].

Three Tai chi studies in FM have resulted in symptom or fitness improvement. The first was a positive “proof of concept” study, but it was limited by lack of a control group [13]. Another was limited by a sample size of six [14]. However, in an NIH funded trial, Wang (2010) reported a parallel group Tai chi RCT with significant improvements in FM symptoms but reported little objective data on functional mobility [15].

The current study extends the previous studies in two important ways. First, we used an 8-form, rather than 10-form, Tai chi program specifically designed for people with FM. Second, we incorporated several objectively assessed functional mobility measures, which are conceptually relevant to Tai chi intervention. Functional mobility is important in FM, as emerging evidence documents poor balance compared to matched controls. Poor balance is associated with falls and disability [16–18]. We hypothesized that Tai chi would be more effective in improving primary outcome of FM symptoms and self-reported physical function, and secondary outcome measures of sleep quality and functional mobility than an attention/time matched, parallel educational control condition.

Methods

Design overview

We conducted a randomized controlled trial with two parallel arms: Tai chi and educational control. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Oregon Research Institute, and written informed consent was obtained from all subjects. All measures were collected by research staff who were unaware of condition assignment.

Screening and randomization

Potential participants were recruited from the Eugene-Springfield, Oregon area. Inclusion criteria included adults 40 years of age or older, meeting the classification of FM per the 1990 ACR criteria [1], and approval by a healthcare provider for participation. Individuals were excluded if they had practiced Tai chi within the past 6 months, had exercised >30 min three times weekly for past 3 months, could not independently ambulate without assistive devices, had BPI pain severity or interference scores less than 5, had planned elective surgery during study period, were actively involved in health-related litigation, or were unwilling to keep all treatments/medications steady throughout the study period. Potential participants were recruited through promotion flyers at local medical clinics and public places, newspaper advertisements, a FM support group, and referrals from the Oregon Pain Society, located in the catchment area. Interested individuals completed a multi-step recruitment process demonstrated to decrease attrition [19]. Participants were assigned to a Tai chi or education condition, using a computer-generated table of random numbers with block stratification using age in 5-year intervals.

Interventions

Tai chi intervention

The Tai chi intervention took place twice weekly for 12 weeks, with each session lasting 90 min. The intervention was based on simplification of an 8-form Yang style program [10]. Suggestions for modification by KJ and RB for FM specific issues were given to the Tai chi master in a single paragraph. These included minimization of (1) prolonged motionless standing, (2) lower squats, (3) overhead work (eccentric muscle contraction), (4) prolonged muscle contraction, (5) fast or repetitive movement, and (6) positions vulnerable to joint hypermobility. It further allowed adequate time for muscle to return to baseline resting state between movements, eliminated bright lights, loud noise, strong odors, and cold temperatures and provided close proximity to restrooms. These modifications were employed to accommodate central sensitization, muscle microtrauma, peripheral pain generation, tendonitis/bursitis/plantar fasciitis, fall risk, multiple chemical sensitivities, irritable bowel syndrome, and painful bladder symptoms [6]. A Tai chi master with over 30 years of practice and instruction experience taught all classes. She was easily able to modify the 8-form practice to accommodate for FM-specific issues. Earlier sessions focused on the general principle of Tai chi, training protocol of movements and exercise of slow, gentle, controlled/rhythmic movements, natural breathing, self-massage, and relaxation. By the 4th week, participants practiced the exercises/relaxation for a full 90 min (15-min warm-up, 45 min of Tai chi training, 15-min break and 15-min cool-down). The overall exercise integrated both static and dynamic postures with a progression of increasing time spent in most postures.

Education intervention

Parallel to the Tai chi condition in amount of attention and time, participants in this condition met in groups of 8–12 persons, 90 min twice weekly for 12 weeks. The group leaders and curriculum content were consistent throughout the intervention. Week 1 was for orientation; week 2 was a presentation by a physician on basic FM facts; weeks 3–7 included presentations by a registered dietician on healthy eating; weeks 8–11 were presentations by a counselor on psychoeducation about FM (education-based cognitive behavioral strategies including time management and prioritizing, coping strategies, dealing with family and friends, and dealing with employers or volunteer co-workers, sleep hygiene, and general lifestyle management).

The interventionists tracked the number of sessions attended and number of minutes participated in both groups. Participants in both conditions completed twice monthly questionnaires to determine if treatments had changed.

Outcomes

The primary endpoint was change on the Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ) total score from baseline to post-intervention. The FIQ, a validated clinical measure, is a 21-item self-assessment of pain, fatigue, morning tiredness, stiffness, depression, anxiety, work ability, and physical function [20]. Scores range from 0 to 100 with higher scores indicating greater symptom burden and poorer physical function. A clinically significant change in the FIQ is 14 % [21]. The first ten FIQ items can be calculated to determine perceived physical function (FIQ-PF). The FIQ and FIQ-PF have been changed significantly in FM exercise studies [22]. Cronbach’s alpha for the FIQ total score in this study was 0.92.

Pain was measured in FIQ numeric rating scale (NRS) for pain severity and has changed significantly in FM studies [8, 23, 24]. Minimally clinically significant improvement in pain severity on a NRS is 10–20 % [25]. Brief Pain Inventory (BPI) short form was also used to measure pain severity (sensory dimension) and interference (reactive dimension) [26] and has changed significantly in FM exercise RCTs [27]. Minimally clinically significant change severity is 2 points [28] and 1 point for intensity [25]. Cronbach’s alpha for the BPI severity and interference score in this study were 0.26 and 0.92, respectively.

Sleep was evaluated with the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (Global PSQI). Previous FM Tai chi RCTs have demonstrated improvement in PSQI [15]. Cronbach’s alpha for the global PSQI in this study was 0.76. Self-efficacy was measured with the Arthritis Self-Efficacy Questionnaire which has improved significantly in FM exercise RCTs [29, 30]. Cronbach’s alpha for the ASES pain/physical function and other symptoms in this study was 0.84, 0.91, and 0.71, respectively. Treatment expectations were assessed prior to randomization as participants were asked “How much do you expect your FM-related symptoms to improve as a result of participating in this program?”

Functional mobility was conceptualized to include static and dynamic balance, gait, strength (power and agility), flexibility, and aerobic capacity. Functional mobility was estimated with the 8-Foot Timed Get Up and Go (TUG) test [31] which has changed significantly in other FM exercise studies [29] and in Tai chi in the elderly [32]. Dynamic balance (limits of stability) was estimated with a maximum reach test. Subjects were asked to stand with feet together; arms extended forward and reach as far in front of them as possible while maintaining heels on the floor [33]. Static balance was estimated with a timed single leg stance (stork test) [34]. Static balance has been significantly improved with yoga and water exercise RCTs but not Tai chi in FM [8, 35]. Upper extremity flexibility was estimated by external and internal rotation of the shoulders by a hand to scapula movement as originally described by Mannerkorpi in FM subjects [36] and later by our team [29, 37].

A self-report demographic and clinical questionnaire was used as was investigator measured body mass index which was derived from measures of height (in inches) and weight (in pounds; Detetco). Prescription medications were recorded and coded by class, but not dose.

Statistical analyses

The primary outcome was analyzed using a conditional change model that regressed the group indicator and the FIQ total change score, which had been centered on the pre FIQ summary score. These analyses employed an intent to treat approach. The advantage of the conditional change model over the more commonly used t test is that it produces less artifact of regression to the mean, controls for baseline differences and has more precise standard deviation of the estimate. It however has the same issues with baseline outliers [38]. Additional analyses were conducted similarly with a Bonferroni–Holm adjustment to address multiple comparisons [39].

Results

Patient characteristics and study adherence

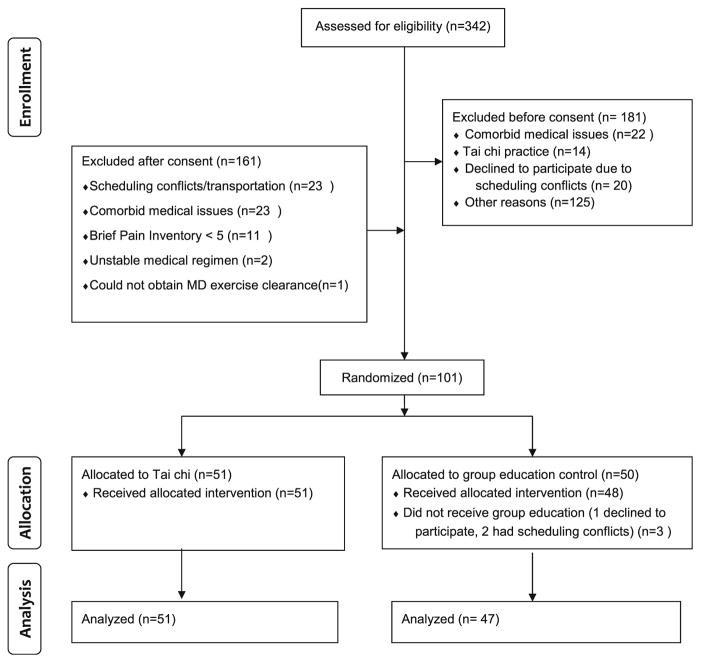

Between January 2006 and July 2008, we screened 537 patients. Figure 1 maps subject flow through the trial. Table 1 displays baseline characteristics of the study population. There were no statistically or clinically significant differences between conditions, including treatment expectations at baseline. Subjects were on average 54 (range 40.7–74.1)years of age. The majority of subjects were on two or more prescription medications for FM, most commonly an analgesic and an anti-depressant. The average time of reported FM symptoms was 18.4 years. Scores on symptom scales and fitness tests were similar between conditions with the FIQ total of 63.9 indicating moderate to severe FM symptoms and functional disability. The average pain NRS was 7 on a 0–10-scale. At least 20 of 24 classes were completed by 72 % of subjects of each intervention condition. There were no significant differences in attendance between control or intervention conditions (19.4 h versus 19.2, p=<0.59). Homework or home practice guided by Tai chi or education handouts was tracked by weekly log. Both groups recorded <40 min/week in home work or home practice (p=<0.72). All subjects completed post intervention assessments regardless of attendance rate. No adverse events were observed during the entire period of the intervention.

Fig. 1.

Subject flow diagram

Table 1.

Baseline characteristicsa

| Mean or % values | Tai chi group (n=51) | Control group (n=47) |

|---|---|---|

| Female sex | 92.1 % | 93.6 % |

| Age in years | 53.3 | 54.8 |

| White race | 98.0 | 95.3 |

| Some college or higher | 88.2 % | 80.9 % |

| BMI | 30.9 | 30.1 |

| Years with FM symptoms | 17.0 | 19.8 |

| Medications | ||

| • Non-narcotic | 70.6 % | 66.0 % |

| • Narcotic | 35.3 % | 36.1 % |

| • Anti-depressants | 49.0 % | 36.2 % |

| • Anti-convulsants | 17.6 % | 14.9 % |

| • Benzodiazepines/sleep | 39.2 % | 38.9 % |

| Employment | ||

| • Full time | 23.5 % | 27.7 % |

| • Part time | 19.6 % | 17.0 % |

| • Not employed outside home | 56.9 % | 53.2 % |

| FIQ total | 64.1 | 63.6 |

| Global PSQI (sleep) | 13.7 | 13.6 |

| BPI severity | 5.4 | 5.7 |

| BPI interference | 6.3 | 6.1 |

| Dynamic balance (cm) | 9.4 | 9.4 |

| Static balance (seconds) | 37.2 | 32.3 |

| 8 Foot-timed get up and go (seconds) | 7.5 | 6.7 |

| Upper body flexibility (cm) | −4.5 | −4.8 |

| FIQ pain | 6.9 | 7.1 |

| Self-efficacy pain | 52.3 | 51.4 |

| Self-efficacy function | 70.5 | 74.8 |

| Self-efficacy other symptoms | 51.3 | 55.2 |

| Treatment expectation | 80.5 | 76.0 |

BMI body mass index, FM fibromyalgia, FIQ fibromyalgia impact questionnaire, PSQI Pittsburg sleep quality index, BPI brief pain inventory

No significant differences between groups at baseline

Between group changes post intervention

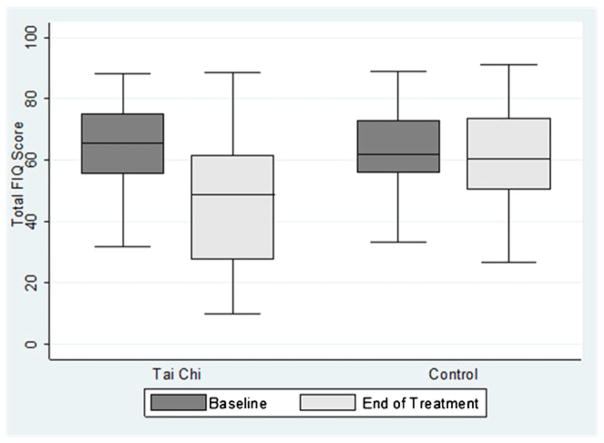

Table 2 shows changes from baseline to 12 weeks for all outcomes in subjects in both conditions. At 12 weeks the Tai chi group had a clinically and significantly greater decrease in FIQ total score compared to the education group; −16.5 vs. −3.1 points (95 % confidence interval [95%CI] −21.4 to −11.7 vs. −15.0 to 8.9]. Figure 2 displays FIQ scores pre and post intervention by group. Similarly pain NRS declined significantly in the Tai chi condition compared to the education condition (−1.6 points vs. −0.5 points [95 % CI −2.0 to −0.03) vs −1.1 to 0.2). Pain as measured by BPI severity decreased significantly in the Tai chi group compared to the education group (−1.2 vs −0.4, [95 % CI −1.7 to −0.1 vs −0.9 to 0.1]) as did BPI interference (−2.1 vs. −0.6 points [95 % CI −3.6 to −0.5 vs −1.2 to 0.1]). Sleep quality improved significantly in the Tai chi group compared to the education group (−2.0 points vs. 0.03 points [95 % CI −3.6 to −0.3 vs. −1.1 to 1.2]). All seven FIQ non-pain symptoms improved significantly (p=0.0001) in the Tai chi condition compared to the education condition (overall well-being, work ability, sleep, fatigue, stiffness, anxiety, and depression). Self-assessment of physical function as measured by FIQ-PF improved significantly in the Tai chi group compared to the education group (−1.2 points vs. −0.5 points [95 % CI −3.3 to 1.2 vs. −0.6 to −0.3].

Table 2.

Change between conditions on primary and secondary outcome measures

| Outcome | Tai chi

|

Education

|

Significance | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean change | 95 % CI | Mean change | 95 % CI | p= | |||

| FIQ total | −16.5 | −21.4 | −11.7 | −3.1 | −15.0 | 8.9 | 0.0002 |

| FIQ physical | −1.2 | −3.3 | −1.2 | −0.5 | −0.6 | −0.3 | 0.0000 |

| FIQ pain | −1.6 | −2.0 | −.03 | −0.5 | −1.1 | 0.2 | 0.0000 |

| BPI severity | −1.2 | −1.7 | −0.1 | −0.4 | −0.9 | 0.1 | 0.0008 |

| BPI interference | −2.1 | −3.6 | −0.5 | −0.6 | −1.2 | 0.1 | 0.0000 |

| Sleep | −2.0 | −3.6 | −0.3 | .03 | −1.1 | 1.2 | 0.0000 |

| SE pain | 9.2 | 2.1 | 18.3 | −1.5 | −0.7 | −0.2 | 0.0000 |

| SE function | 7.9 | 0.9 | 14.1 | −0.3 | −0.5 | −0.1 | 0.0007 |

| SE other | 12.5 | 3.8 | 21.1 | −0.8 | −0.9 | −0.6 | 0.0000 |

| Dynamic balance | 1.6 | 0.2 | 2.4 | 0.3 | −0.5 | 1.1 | 0.0000 |

| Static balance | 7.5 | 1.7 | 13.2 | −0.3 | −0.5 | −0.2 | 0.0000 |

| Timed get up and go | −0.9 | −1.5 | −0.3 | −0.3 | −0.3 | −0.2 | 0.0000 |

| Flexibility | 0.6 | −0.4 | 1.6 | −0.0 | −0.7 | 0.7 | NS |

CI confidence interval, FIQ fibromyalgia impact questionnaire, BPI brief pain inventory, SE self-efficacy, NS not significant

Fig. 2.

Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ) total scores

Three functional mobility measures improved. Static balance improved significantly in the Tai chi group compared with the education group (7.5 points vs. −0.3 points [95 % CI 1.7 to 13.2 versus −0.5 to −0.2]). Dynamic balance improved significantly in the Tai chi group compared with the education group 1.6 cms vs 0.5 [95 % CI 0.2 to 2.4 vs. −0.5 to 1.1]) as did timed Get-Up-and-Go (−0.9 s vs. −0.3 s [95 % CI −1.5 to −0.3 vs. −0.3 to −0.2]). Upper body flexibility did not change significantly in either group (0.6 vs. 0 cms [95 % CI −0.4 to 1.6 versus −0.7 to 0.7] p=0.41, nor did BMI (0.3 vs. −0.3 points [95 % CI −1.1 to 1.6 versus −0.9 to 0.3], p=0.10).

Self-efficacy improved significantly in the Tai chi group compared to the education group: pain (9.2 vs. −1.5 [95 % CI 2.1 to 18.3 vs. −0.7 to −0.2]); function (7.9 vs. −0.3 [95 % CI 0.9 to 14.1 vs. −0.5 to −0.1]; other symptoms (12.5 vs. −0.8 points [95 % CI 3.8 to 21.2 vs. −0.9 to −0.6]). Medication was not significantly different among either group at baseline or end of treatment.

Discussion

The primary finding from this trial is that Tai chi compared to the education condition improves symptoms, physical function, quality of sleep, self-efficacy, and functional mobility for people with FM. Importantly, there were no adverse events during the study, suggesting that 12 weeks of progressive Tai chi appears to be an exercise modality that does not produce major exercise-related symptom flares.

We also report negative findings from this trial. Specifically, upper body flexibility was not significantly improved in either group, perhaps because exercise movements were mostly kept below shoulder level to minimize eccentric muscle work-an FM modification. Similarly, neither weight nor BMI was significantly reduced in either group despite baseline obesity. Further investigation is needed to determine the safety and efficacy of Tai chi for overweight persons with FM.

Our symptom findings agree with those reported by Wang (2010) who randomized 66 FM subjects to 12 weeks of twice weekly, 60 min, group 10-form Yang-style Tai chi or group education with gentle stretching [15]. Wang et al.’s data revealed similar between-groups changes in FIQ total (−18.4 [−26.9 to −9.8]) and PSQI (−2.9 [−4.6 to −1.2]). Wang (2010) also reported significant improvement in pain as measured by Patient Global Assessment of Pain, whereas we demonstrated pain improvements based on FIQ Pain NRS, and BPI severity and interference.

Our interventions differed primarily in that we enrolled one-third more subjects, measured objective functional mobility outcomes and tested an 8-form rather than 10-form Tai chi program. Compared to the 10-form, the 8-form has fewer and simpler sequences intended for clinical populations that are functionally or cognitively challenged [40]. In terms of physical findings, Wang (2010) measured 6-min walk which was significantly improved immediately post intervention (p<0.007). Our study extends this finding by demonstrating significant improvements in static balance, dynamic balance, and timed get-up-and-go. These consistent findings of improvements in objective measures of functional mobility carry important clinical implications, suggesting that FM patients trained in Tai chi may help decrease risk for falls and minimize difficulties in performing essential daily physical activity tasks [41].

Over 100 conventional exercise interventions for FM have been published; ~80 % of them is aerobic or mixed-type (aerobic, strength, flexibility) [7, 42–48]. A recent meta-analysis concluded that immediately post intervention, high quality aerobic or mixed modality studies with lower attrition reliably restore physical function or fitness (d=.65) and health related quality of life (d=−0.40) , while exerting no significant effects on sleep (d=0.01). Effect sizes for pain were small (d=−0.31) and not sustained at follow-up (d= 0.13) [7]. Similarly, 14 strength or stretching studies consistently demonstrated improvements in physical function but inconsistently improved FM symptoms [42, 45]. Studies included in the meta-analysis had a median attrition of 67 % (range 27–90 %), suggesting that some of the interventions themselves were not acceptable. Some early programs dosed the interventions too high (exercise frequency, intensity, and timing), or required medication wash-out with attrition averaging ~40 %. Others selected inappropriate modalities such as running, fast dancing, or high intensity aerobics resulting in 62–67 % attrition [49, 50]. Lower intensity or water-based programs fared better with an average attrition of ~20 %, and strength training interventions showed attrition at 13 % [42]. Only two rigorous trials [51, 52] examined effects of a 6-month intervention with continued 6-month follow-up, and these had negative findings. FM patients face exercise induced pain or fear of pain in adopting aerobic and other forms of conventional exercise [53–55]. Substantive mindfulness training is not a usual feature of exercise. Conventional exercise focuses on teaching modified physical movements. However, the findings of this study and our recently published yoga + mindfulness trial [8] suggest that when movement is intensively combined with mindfulness, FM patients can learn to move mindfully and better accept disagreeable sensations arising during movement, thereby maximizing self-efficacy and long-term adherence to and benefits from exercise. Similarly, the central hypothesis of this study was that because Tai chi is practiced with concurrent substantive moving meditation and mindfulness, it reduced FM severity and pain. Interventions which are paired with significant mindfulness/meditation/cognitive behavioral training may reduce pain-related fear, increase pain acceptance, and result in greater self-efficacy and long-term adherence.

Because pain is a subjective experience influenced by sensory, emotional and cognitive components, more data are needed on the mechanisms by which Tai chi may reduce the sensory component of pain. Quantitative sensory testing (QST), which has the ability to quantify ascending and descending pain processes, has been widely used to characterize pain processing abnormalities in FM [56], and has the potential to elucidate mechanisms by which Tai chi produces sensory modulation. Previous research has in fact demonstrated Tai chi’s ability to alter sensory perception and produce perceptual changes in experienced Tai chi practitioners [57], though thus far no researcher has investigated the effects of Tai chi on QST variables in FM. QST has been used in an attempt to elucidate mechanisms of pain relief in patients with FM using yoga [58] and deep breathing [59], demonstrating the potential utility of using QST to better understand the pain relieving effects of Tai chi.

Like pain, the mechanism of action of functional mobility improvement is not fully elucidated in the study. Balance or postural stability is a complex task that involves the rapid and dynamic integration of multiple sensory, motor, and cognitive inputs to execute appropriate neuromuscular activity needed to maintain balance [60]. Two groups have recently reported a significant difference between FM patients and matched controls in multiple balance components with computerized dynamic posturography [33, 61]. Although it is not yet known how Tai chi may improve balance deficits in FM patients, a study in healthy elders that compared Tai chi to standard education demonstrated significant improvement in multiple measures of dynamic posturography, including vestibular ratio in the sensory organization test and directional control in limits of stability testing [62]. Elders are a logical comparison group for FM as three fitness studies have reported balance scores in 40-year-old FM subjects to be comparable to 80-year-old healthy elders [16, 33, 63].

The current study has limitations. In contrast to Wang’s (2010) sample, ours was characterized by significantly higher education and less ethnic diversity. Neither study enrolled children or an adequate number of men to meaningfully analyze their data to detect gender differences. One very small, uncontrolled study of Tai chi for men with FM reported improvements in strength and flexibility, but not FM symptoms, suggesting extra caution in interpreting our results relative to men [14]. The interpretation of this and many studies may not fully account for a Hawthone effect of “wishing to please” or other non-specific effects of observation, but this a major reason for carefully matched parallel control groups [64].

Researchers of complementary and alternative medicine studies, including Tai chi, are struggling to determine the ideal comparison control [65, 66]. On one hand, a double blind study would be possible if one developed and tested “sham” Tai chi. The utility of such a comparison has been questioned by those who advocate instead a single-blind study with adequate attention to expectancy and use of a active comparison condition. Notably, in both our study and Wang’s, outcome expectations were similar in both conditions and did not predict symptom change. Placebo effect in single-blinded studies can be further reduced by (1) employing parallel designs rather than wait list controls, (2) stating in the consent form that the researchers are studying two interventions rather than comparing an experimental treatment to usual care plus attention, (3) measuring the effect of treatment expectation after group assignment and use those data as a co-variant in analyses, (4) minimizing effect of contextual variables—use the same environment of exercise studio and testing laboratory, and (5) employing the same interventionist for multiple groups when possible and measuring relationship with interventionist to minimize the effect of the interventionist rather than the intervention, as relationship to provider is a critical contextual variable. Along those lines, we employed a single elderly Tai chi master who delivered 100 % of the intervention. It is possible that her personality or age enhanced outcomes by giving subjects hope and confidence for their own futures. In support of this idea, So reviewed 62 acupuncture studies and concluded that outcomes appeared not to be related to placebo effects or patient expectations, but rather to client–practitioner relationships [67]. Lastly, the instructor stated her belief that any Tai chi master could easily modify the intervention for FM based on the modification paragraph supplied by KJ and RB. To verify this assertion further study would be needed, examining multiple Tai chi instructors with a wide range of experience carrying out a specific Tai chi protocol modified for FM.

A final limitation in our study was lack of follow-up. Wang et al. [15], however, completed follow-up 12 weeks after the 12 week intervention. They found continued significance at 24 weeks on total FIQ, pain, PSQI, patient and physician global assessment, SF-36 physical and mental components, and depression. Six-minute walk and self-efficacy trended in the expected direction in the Tai chi condition, but were no longer significantly different between conditions at 24 weeks [15]. Wang et al.’s findings contrast with follow up studies of aerobic exercise for FM, which have shown minimal or no maintenance of most benefits, with a conclusion that continuing exercise is needed to maintain positive effects on pain. Based on our study and Wang et al.’s, the long-term effects of Tai chi in FM remain to be determined.

In summary, two randomized controlled single blind trials indicate that Tai chi holds potential as a useful modality in the multidimensional treatment of FM. Longer studies, with laboratory based evaluation of symptom and fitness change, could deepen our understanding of the mechanisms by which Tai chi improves FM outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Primary Funding Source: National Institutes of Health/NIAMS 5R21 AR053506 NIH/NCCAM1K23AT006392-01. We extend our heartfelt acknowledgment to Dr. John Fisher who was unable to see his study through to fruition. Thanks also to Cheryl Weimer, Lisa Marion, Debbie Blanchard, Damini Branen, Lindsay Kindler, and Cheryl Wright for their assistance with intervention implementation and/or data collection.

Footnotes

Disclosures: None.

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s10067-012-1996-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Contributor Information

Kim D. Jones, Fibromyalgia Research Unit, Oregon Health & Science University, 3181 SW Sam Jackson Park Rd., Mail Code: SN-ORD, Portland, OR 97239-3011, USA

Christy A. Sherman, Oregon Research Institute, 1715 Franklin Blvd, Eugene, OR 97403, USA

Scott D. Mist, Fibromyalgia Research Unit, Oregon Health & Science University, 3181 SW Sam Jackson Park Rd., Mail Code: SN-ORD, Portland, OR 97239-3011, USA

James W. Carson, Fibromyalgia Research Unit, Oregon Health & Science University, 3181 SW Sam Jackson Park Rd., Mail Code: SN-ORD, Portland, OR 97239-3011, USA

Robert M. Bennett, Fibromyalgia Research Unit, Oregon Health & Science University, 3181 SW Sam Jackson Park Rd., Mail Code: SN-ORD, Portland, OR 97239-3011, USA

Fuzhong Li, Oregon Research Institute, 1715 Franklin Blvd, Eugene, OR 97403, USA.

References

- 1.Wolfe F, Smythe HA, Yunus MB, Bennett RM, Bombardier C, Goldenberg DL, Tugwell P, Campbell SM, Abeles M, Clark P. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 Criteria for the Classification of Fibromyalgia. Report of the Multicenter Criteria Committee. Arthritis Rheum. 1990;33:160–172. doi: 10.1002/art.1780330203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wolfe F, Anderson J, Harkness D, Bennett RM, Caro XJ, Goldenberg DL, Russell IJ, Yunus MB. A prospective, longitudinal, multicenter study of service utilization and costs in fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:1560–1570. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carville SF, Arendt-Nielsen S, Bliddal H, Blotman F, Branco JC, Buskila D, Da Silva JA, Danneskiold-Samsoe B, Dincer F, Henriksson C, Henriksson KG, Kosek E, Longley K, McCarthy GM, Perrot S, Puszczewicz M, Sarzi-Puttini P, Silman A, Spath M, Choy EH. EULAR evidence-based recommendations for the management of fibromyalgia syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:536–541. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.071522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Goldenberg DL, Burckhardt C, Crofford L. Management of fibromyalgia syndrome. JAMA. 2004;292:2388–2395. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.19.2388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Paiva ES, Jones KD. Rational treatment of fibromyalgia for a solo practitioner. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2010;24:341–352. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2009.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones KD, Liptan GL. Exercise interventions in fibromyalgia: clinical applications from the evidence. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2009;35:373–391. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hauser W, Klose P, Langhorst J, Moradi B, Steinbach M, Schiltenwolf M, Busch A. Efficacy of different types of aerobic exercise in fibromyalgia syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12:R79. doi: 10.1186/ar3002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carson JW, Carson KM, Jones KD, Bennett RM, Wright CL, Mist SD. A pilot randomized controlled trial of the Yoga of Awareness program in the management of fibromyalgia. Pain. 2010;151:530–539. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang C, Schmid CH, Hibberd PL, Kalish R, Roubenoff R, Rones R, Okparavero A, McAlindon T. Tai Chi for treating knee osteoarthritis: designing a long-term follow up randomized controlled trial. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2008;9:108. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-9-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li F, Harmer P, Fisher KJ, McAuley E, Chaumeton N, Eckstrom E, Wilson NL. Tai Chi and fall reductions in older adults: a randomized controlled trial. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60:187–194. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.2.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang C, Roubenoff R, Lau J, Kalish R, Schmid CH, Tighiouart H, Rones R, Hibberd PL. Effect of Tai Chi in adults with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2005;44:685–687. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang C, Schmid CH, Hibberd PL, Kalish R, Roubenoff R, Rones R, McAlindon T. Tai Chi is effective in treating knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:1545–1553. doi: 10.1002/art.24832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taggart HM, Arslanian CL, Bae S, Singh K. Effects of T'ai Chi exercise on fibromyalgia symptoms and health-related quality of life. Orthop Nurs. 2003;22:353–360. doi: 10.1097/00006416-200309000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carbonell-Baeza A, Romero A, Aparicio VA, Ortega FB, Tercedor P, Delgado-Fernandez M, Ruiz JR. Preliminary findings of a 4-month Tai Chi intervention on tenderness, functional capacity, symptomatology, and quality of life in men with fibromyalgia. Am J Mens Health. 2011;5:421–429. doi: 10.1177/1557988311400063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang C, Schmid CH, Rones R, Kalish R, Yinh J, Goldenberg DL, Lee Y, McAlindon T. A randomized trial of tai chi for fibromyalgia. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:743–754. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0912611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones CJ, Rutledge DN, Aquino J. Predictors of physical performance and functional ability in people 50+ with and without fibromyalgia. J Aging Phys Act. 2010;18:353–368. doi: 10.1123/japa.18.3.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jones KD, Horak FB, Winters-Stone K, Irvine JM, Bennett RM. Fibromyalgia is associated with impaired balance and falls. J Clin Rheumatol. 2009;15:16–21. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0b013e318190f991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rutledge DN, Cherry BJ, Rose DJ, Rakovski C, Jones CJ. Do fall predictors in middle aged and older adults predict fall status in persons 50+ with fibromyalgia? An exploratory study. Res Nurs Health. 2010;33:192–206. doi: 10.1002/nur.20376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jones KD, Reiner AC. A multistep recruitment strategy to a participant-intensive clinical trial. Appl Nurs Res. 2010;23:227–232. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2008.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bennett R. The Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQ): a review of its development, current version, operating characteristics and uses. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2005;23:S154–S162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bennett RM, Bushmakin AG, Cappelleri JC, Zlateva G, Sadosky AB. Minimal clinically important difference in the fibromyalgia impact questionnaire. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:1304–1311. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.081090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mannerkorpi K, Nordeman L, Cider A, Jonsson G. Does moderate-to-high intensity Nordic walking improve functional capacity and pain in fibromyalgia? A prospective randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12:R189. doi: 10.1186/ar3159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bennett RM, Kamin M, Karim R, Rosenthal N. Tramadol and acetaminophen combination tablets in the treatment of fibromyalgia pain: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Am J Med. 2003;114:537–545. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(03)00116-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones KD, Adams D, Winters-Stone K, Burckhardt CS. A comprehensive review of 46 exercise treatment studies in fibromyalgia (1988–2005) Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:67. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Wyrwich KW, Beaton D, Cleeland CS, Farrar JT, Haythornthwaite JA, Jensen MP, Kerns RD, Ader DN, Brandenburg N, Burke LB, Cella D, Chandler J, Cowan P, Dimitrova R, Dionne R, Hertz S, Jadad AR, Katz NP, Kehlet H, Kramer LD, Manning DC, McCormick C, McDermott MP, McQuay HJ, Patel S, Porter L, Quessy S, Rappaport BA, Rauschkolb C, Revicki DA, Rothman M, Schmader KE, Stacey BR, Stauffer JW, von Stein T, White RE, Witter J, Zavisic S. Interpreting the clinical importance of treatment outcomes in chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. J Pain. 2008;9:105–121. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cleeland CS, Ryan KM. Pain assessment: global use of the Brief Pain Inventory. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 1994;23:129–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ang D, Kesavalu R, Lydon JR, Lane KA, Bigatti S. Exercise-based motivational interviewing for female patients with fibromyalgia: a case series. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26:1843–1849. doi: 10.1007/s10067-007-0587-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mease PJ, Spaeth M, Clauw DJ, Arnold LM, Bradley LA, Jon RI, Kajdasz DK, Walker DJ, Chappell AS. Estimation of minimum clinically important difference for pain in fibromyalgia. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011;63:821–826. doi: 10.1002/acr.20449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jones KD, Burckhardt CS, Clark SR, Bennett RM, Potempa KM. A randomized controlled trial of muscle strengthening versus flexibility training in fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol. 2002;29:1041–1048. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lorig K, Chastain RL, Ung E. Development and evaluation of a scale to measure perceived self-efficacy in people with arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1989;32:37–44. doi: 10.1002/anr.1780320107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Podsiadlo D, Richardson S. The timed “Up & Go”: a test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39:142–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb01616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu G, Keyes L, Callas P, Ren X, Bookchin B. Comparison of telecommunication, community, and home-based Tai Chi exercise programs on compliance and effectiveness in elders at risk for falls. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;91:849–856. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jones KD, King LA, Mist SD, Bennett RM, Horak FB. Postural control deficits in people with fibromyalgia: a pilot study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2011;13:R127. doi: 10.1186/ar3432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.ACSM’s guidelines for exercise testing and prescription. 8. Media, PA: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tomas-Carus P, Gusi N, Hakkinen A, Hakkinen K, Raimundo A, Ortega-Alonso A. Improvements of muscle strength predicted benefits in HRQOL and postural balance in women with fibromyalgia: an 8-month randomized controlled trial. Rheumatol (Oxford) 2009;48:1147–1151. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mannerkorpi K, Burckhardt CS, Bjelle A. Physical performance characteristics of women with fibromyalgia. Arthritis Care Res. 1994;7:123–129. doi: 10.1002/art.1790070305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jones KD, Burckhardt CS, Deodhar AA, Perrin NA, Hanson GC, Bennett RM. A six-month randomized controlled trial of exercise and pyridostigmine in the treatment of fibromyalgia. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:612–622. doi: 10.1002/art.23203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aickin M. Dealing with change: using the conditional change model for clinical research. Perm J. 2009;13:80–84. doi: 10.7812/tpp/08-070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Holm S. A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scand J Stat. 1979;6:65–70. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fisher KJ, Li F, Shirai ME. Ezy Tai Chi: a simpler practice for seniors. J Active Aging. 2004;3:18–26. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li F, Harmer P, Fitzgerald K, Eckstrom E, Stock R, Galver J, Maddalozzo G, Batya SS. Tai chi and postural stability in patients with Parkinson's disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:511–519. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1107911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brosseau L, Wells GA, Tugwell P, Egan M, Wilson KG, Dubouloz CJ, Casimiro L, Robinson VA, McGowan J, Busch A, Poitras S, Moldofsky H, Harth M, Finestone HM, Nielson W, Haines-Wangda A, Russell-Doreleyers M, Lambert K, Marshall AD, Veilleux L. Ottawa Panel evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for strengthening exercises in the management of fibromyalgia: part 2. Phys Ther. 2008;88:873–886. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20070115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brosseau L, Wells GA, Tugwell P, Egan M, Wilson KG, Dubouloz CJ, Casimiro L, Robinson VA, McGowan J, Busch A, Poitras S, Moldofsky H, Harth M, Finestone HM, Nielson W, Haines-Wangda A, Russell-Doreleyers M, Lambert K, Marshall AD, Veilleux L. Ottawa Panel evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for aerobic fitness exercises in the management of fibromyalgia: part 1. Phys Ther. 2008;88:857–871. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20070200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Busch AJ, Barber KA, Overend TJ, Peloso PM, Schachter CL. Exercise for treating fibromyalgia syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007:CD003786. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003786.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jones KD, Liptan GL. Exercise interventions in fibromyalgia: clinical applications from the evidence. Rheum Dis Clin N Am. 2009;35:373–391. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2009.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Busch AJ, Webber SC, Brachaniec M, Bidonde J, Bello-Haas VD, Danyliw AD, Overend TJ, Richards RS, Sawant A, Schachter CL. Exercise therapy for fibromyalgia. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2011;15:358–367. doi: 10.1007/s11916-011-0214-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kelley GA, Kelley KS, Hootman JM, Jones DL. Exercise and global well-being in community-dwelling adults with fibromyalgia: a systematic review with meta-analysis. BMC Publ Health. 2010;10:198. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cazzola M, Atzeni F, Salaffi F, Stisi S, Cassisi G, Sarzi-Puttini P. Which kind of exercise is best in fibromyalgia therapeutic programmes? A practical review. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2010;28:S117–S124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Meyer BB, Lemley KJ. Utilizing exercise to affect the symptomology of fibromyalgia: a pilot study. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32:1691–1697. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200010000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Norregaard J, Lykkegaard JJ, Mehlsen J, Danneskiold-Samsoe B. Exercise training in treatment of fibromyalgia. Journal of Musculoskelet Pain. 2011;5:71–79. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ang DC, Kaleth AS, Bigatti S, Mazzuca S, Saha C, Hilligoss J, Lengerich M, Bandy R. Research to Encourage Exercise for Fibromyalgia (REEF): use of motivational interviewing design and method. Contemp Clin Trials. 2011;32:59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2010.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fontaine KR, Conn L, Clauw DJ. Effects of lifestyle physical activity in adults with fibromyalgia: results at follow-up. J Clin Rheumatol. 2011;17:64–68. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0b013e31820e7ea7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Clark SR. Prescribing exercise for fibromyalgia patients. Arthritis Care Res. 1994;7:221–225. doi: 10.1002/art.1790070410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jones KD, Clark SR, Bennett RM. Prescribing exercise for people with fibromyalgia. AACN Clin Issues. 2002;13:277–293. doi: 10.1097/00044067-200205000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jones KD, Hoffman JH. Exercise and chronic pain: opening the therapueutic window. Functional Fitness: An ICCA Publication. 2006;4:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Williams DA, Clauw DJ. Understanding fibromyalgia: lessons from the broader pain research community. J Pain. 2009;10:777–791. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kerr CE, Shaw JR, Wasserman RH, Chen VW, Kanojia A, Bayer T, Kelley JM. Tactile acuity in experienced Tai Chi practitioners: evidence for use dependent plasticity as an effect of sensory-attentional training. Exp Brain Res. 2008;188:317–322. doi: 10.1007/s00221-008-1409-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.da Silva GD, Lorenzi-Filho G, Lage LV. Effects of yoga and the addition of Tui Na in patients with fibromyalgia. J Altern Complement Med. 2007;13:1107–1113. doi: 10.1089/acm.2007.0615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zautra AJ, Fasman R, Davis MC, Craig AD. The effects of slow breathing on affective responses to pain stimuli: an experimental study. Pain. 2010;149:12–18. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Horak FB. Postural orientation and equilibrium: what do we need to know about neural control of balance to prevent falls? Age Ageing. 2006;35(Suppl 2):ii7–ii11. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afl077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Russek LN, Fulk GD. Pilot study assessing balance in women with fibromyalgia syndrome. Physiother Theory Pract. 2009;25:555–565. doi: 10.3109/09593980802668050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tsang WW, Hui-Chan CW. Effect of 4- and 8-wk intensive Tai Chi Training on balance control in the elderly. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36:648–657. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000121941.57669.bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cherry BJ, Weiss J, Barakat BK, Rutledge DN, Jones CJ. Physical performance as a predictor of attention and processing speed in fibromyalgia. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90:2066–2073. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2009.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Peirce-Sandner S, Baron R, Bellamy N, Burke LB, Chappell A, Chartier K, Cleeland CS, Costello A, Cowan P, Dimitrova R, Ellenberg S, Farrar JT, French JA, Gilron I, Hertz S, Jadad AR, Jay GW, Kalliomaki J, Katz NP, Kerns RD, Manning DC, McDermott MP, McGrath PJ, Narayana A, Porter L, Quessy S, Rappaport BA, Rauschkolb C, Reeve BB, Rhodes T, Sampaio C, Simpson DM, Stauffer JW, Stucki G, Tobias J, White RE, Witter J. Research design considerations for confirmatory chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. Pain. 2010;149:177–193. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fregni F, Imamura M, Chien HF, Lew HL, Boggio P, Kaptchuk TJ, Riberto M, Hsing WT, Battistella LR, Furlan A. Challenges and recommendations for placebo controls in randomized trials in physical and rehabilitation medicine: a report of the international placebo symposium working group. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2010;89:160–172. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e3181bc0bbd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yeh GY, Kaptchuk TJ, Shmerling RH. Prescribing tai chi for fibromyalgia–are we there yet? N Engl J Med. 2010;363:783–784. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1006315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.So DW. Acupuncture outcomes, expectations, patient-provider relationship, and the placebo effect: implications for health promotion. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:1662–1667. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.10.1662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.