Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Death by suicide during the perinatal period has been understudied in Canada. We examined the epidemiology of and health service use related to suicides during pregnancy and the first postpartum year.

METHODS:

In this retrospective, population-based cohort study, we linked health administrative databases with coroner death records (1994–2008) for Ontario, Canada. We compared sociodemographic characteristics, clinical features and health service use in the 30 days and 1 year before death between women who died by suicide perinatally, women who died by suicide outside of the perinatal period and living perinatal women.

RESULTS:

The perinatal suicide rate was 2.58 per 100 000 live births, with suicide accounting for 51 (5.3%) of 966 perinatal deaths. Most suicides occurred during the final quarter of the first postpartum year, with highest rates in rural and remote regions. Perinatal women were more likely to die from hanging (33.3% [17/51]) or jumping or falling (19.6% [10/51]) than women who died by suicide non-perinatally (p = 0.04). Only 39.2% (20/51) had mental health contact within the 30 days before death, similar to the rate among those who died by suicide non-perinatally (47.7% [762/1597]; odds ratio [OR] 0.71, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.40–1.25). Compared with living perinatal women matched by pregnancy or postpartum status at date of suicide, perinatal women who died by suicide had similar likelihood of non–mental health primary care and obstetric care before the index date but had a lower likelihood of pediatric contact (64.5% [20/31] v. 88.4% [137/155] at 30 days; OR 0.24, 95% CI 0.10–0.58).

INTERPRETATION:

The perinatal suicide rate for Ontario during the period 1994–2008 was comparable to international estimates and represents a substantial component of Canadian perinatal mortality. Given that deaths by suicide occur throughout the perinatal period, all health care providers must be collectively vigilant in assessing risk.

In developed countries, maternal suicide is a leading cause of death during pregnancy and the first postpartum year.1–5 Existing Canadian data suggest that suicide is the fourth leading cause of death in the perinatal period.6 However, rates may be underestimated, because they typically include only “maternal deaths” in pregnancy or up to 6 weeks (42 d) after the birth, despite the fact that the burden of suicide related to postpartum mental illness is likely to extend beyond 6 weeks postpartum.7–9 Furthermore, these rates are based on whether the death certificate records pregnancy or recent childbirth. Data from Europe suggest that underreporting of perinatal suicide on death certificates is in the range of 26% to 56%,10,11 given that the presence of a child, or perhaps a birth, does not always emerge during the investigation of a death.1,4,9,12,13 Despite high-profile media attention and calls to increase knowledge, with the goal of encouraging policy change, little is known about the true extent of the problem in Canada or the steps that can be taken to prevent it.14,15 Greater knowledge about the suicide rate during pregnancy and the postpartum period, as well as the characteristics and patterns of health service use of women who die by suicide, is critical to inform suicide prevention strategies for perinatal women, and ultimately to reduce maternal mortality.

In this study, we combined coroner death records with population-level health administrative data to study deaths by suicide during the perinatal period in Ontario, Canada, over a 15-year period. After determination of the perinatal suicide rate, we compared sociodemographic, clinical presentation and health service use characteristics of women who died by suicide perinatally with those of women who died by suicide during the same period but who were not perinatal (non-perinatal group) and with those of age-matched living perinatal women (controls).

Methods

Data sources and linkage

We extracted primary data, including death certificates and reports of postmortem examinations, from the Office of the Chief Coroner for Ontario for all women aged 18 to 45 years who died by suicide in Ontario, Canada, between 1994 and 2008. We linked coroner records with population-based health administrative data housed within the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES) through probabilistic linkage (names, dates of birth and death, postal codes) to Ontario’s Registered Persons Database, which contains information for all Ontario residents with a provincial health card. Once linked, the records were de-identified and linked at ICES to other health administrative databases (Appendix 1, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.170088/-/DC1). The data from these health administrative data sources are complete and reliable, with high diagnostic validity for hospital admissions; however, from outpatient mental health codes alone, it is difficult to ascertain specific diagnoses within the mood and anxiety disorder spectrum.16–21

Exposure groups

We classified women who died by suicide as “perinatal” using coroner records or health administrative data, where there was a pregnancy (at least 2 pregnancy-related ultrasound examinations or a prenatal visit with a family physician or obstetrician within the 40 weeks preceding death)22 or hospitalization for obstetric delivery within the 365 days before death.23 The timing of suicide relative to pregnancy was based on combined information from the coroner’s office (including autopsy records for pregnant women) and the date of hospital delivery. We dealt with discrepancies between coroner and health administrative data on a case-by-case basis, with autopsy records taking precedence for possibly pregnant women, and hospital delivery records taking precedence for correct classification of postpartum women. We classified all other suicides as non-perinatal, except for those within 1 year after an abortion or stillbirth (which we excluded from the analyses).

We created a living perinatal control group based on health administrative data by matching the perinatal women with death by suicide in a 1:5 ratio with living controls, matched within 2 years on maternal age and calendar year of birth (or expected birth). To facilitate comparisons between groups, we assigned each living perinatal control an index date that matched the number of weeks of gestation or weeks postpartum of the matched perinatal woman who died by suicide.

Variables of interest

We extracted data for demographic and clinical variables from coroner records and health administrative databases (Appendices 1 and 2, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.170088/-/DC1).19,24 We generated variables for health care use using health administrative data. For consistency with the literature, we defined outpatient mental health contact within 30 days and 1 year before suicide25 as either contact with a psychiatrist or a mental health visit with a primary care provider, using a validated algorithm.26 We recorded psychiatric emergency department visits (available for 2002 forward) and psychiatric hospital admissions in the 30 days and 1 year before death. We also recorded contact with primary care providers for non–mental health reasons, contact with an obstetrician and contact with a pediatrician within 30 days and 1 year of death (Appendix 3, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.170088/-/DC1).

Statistical analysis

We calculated the suicide rate during the perinatal period as the number of suicides per 100 000 live births over the course of the study period. We determined the proportion of maternal deaths attributable to suicide by dividing the number of perinatal suicides by the number of maternal perinatal deaths, as per health administrative data codes for pregnancy-related death (where there was no evidence of delivery or medical or spontaneous abortion), or, for postpartum women, the deaths that occurred where there was evidence of a delivery in the preceding 365 days.

We calculated population age-standardized rates for each health region. We present sample characteristics as means, medians or proportions, with comparisons between groups, as appropriate, on sociodemographic, medical and psychiatric history, and suicide characteristics using t tests for continuous variables and χ2 tests for categorical variables. We compared health care use before suicide between groups, generating odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and using logistic regression to compare women who died perinatally with those who died non-perinatally and conditional logistic regression to compare women who died perinatally with their matched living controls. A trained research assistant extracted data from coroner records; another member of the research team checked 15% of the records to ensure reliability. We performed statistical analyses using SAS software, version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc.) at ICES.

According to Ontario provincial privacy legislation, all data values below 6 are considered nonreportable, to avoid the possibility of identifying specific individuals.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the research ethics boards of the Women’s College Hospital and Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre.

Results

A total of 1914 women died by suicide during the study period, according to death records of the Office of the Chief Coroner for Ontario; of these, we linked 1695 (88.6%) by probabilistic matching with administrative health data. We excluded an additional 47 women who did not meet our criteria (Appendix 4, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.170088/-/DC1), which left 1648 suicides for analysis. Of these, 51 were classified as perinatal (20 during pregnancy, 31 during the postpartum period), a greater number than would have been classified as perinatal using either data source alone (Table 1). The perinatal suicide rate was 2.58 per 100 000 live births. Suicide accounted for 5.3% (51/966 or about 1/19) of deaths in perinatal women in Ontario: 4.4% (20/453) of pregnancy-related deaths, and 6.0% (31/513) of postpartum deaths.

Table 1:

Classification of 1648 suicides as perinatal or non-perinatal, according to data source

| Data source and group | Group; no. (%) of suicides n = 1648 | Perinatal suicide rate per 100 000 live births | Suicides during perinatal period as % of all perinatal deaths | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perinatal | Non-perinatal | |||

| Coroner data | ||||

| Overall | 35 (2.1) | 1613 (97.9) | ||

| Pregnancy only | 13 (0.8) | NA | ||

| Postpartum only | 22 (1.3) | NA | ||

| Administrative data | ||||

| Overall | 46 (2.8) | 1602 (97.2) | ||

| Pregnancy only | 17 (1.0) | NA | ||

| Postpartum only | 29 (1.8) | NA | ||

| Combined data | ||||

| Overall | 51 (3.1) | 1597 (96.9) | 2.58 | 5.3 |

| Pregnancy only | 20 (1.2) | NA | 1.01 | 4.4 (of all pregnancy-related deaths) |

| Postpartum only | 31 (1.9) | NA | 1.57 | 6.0 (of all postpartum-related deaths) |

Note: NA = not applicable.

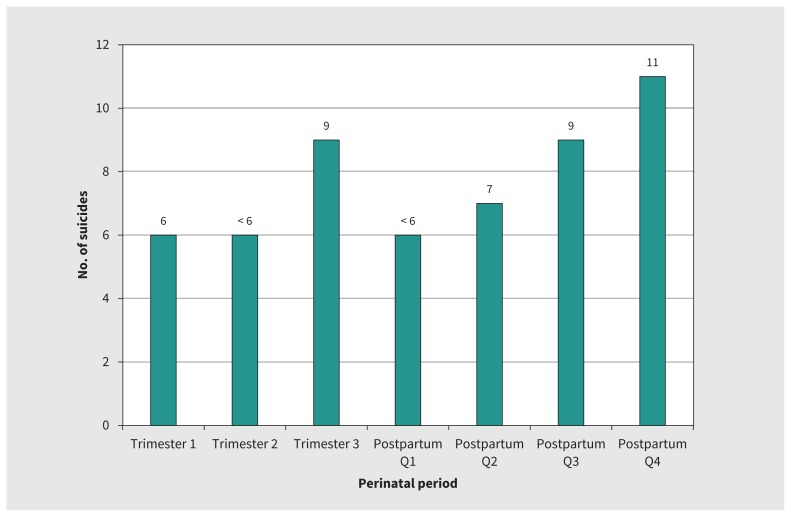

Death by suicide occurred throughout the perinatal period, but the largest numbers of suicides were in the last trimester of pregnancy and, especially, the final quarter of the first postpartum year (Figure 1). For pregnant women, suicide occurred on average at 5 months and for postpartum women, at 7.5 months (Figure 1). The majority of women who died by suicide lived in either urban centres (> 100 000 people)27 or small population centres (< 10 000 people),27 with the highest rates in the North West Local Health Integration Network (LHIN) of Ontario (Appendix 5, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.170088/-/DC1). This regional distribution was similar to that for death by suicide among non-perinatal women.

Figure 1:

Frequency distribution of deaths by suicide in Ontario among pregnant and postpartum women (1994–2008), by pregnancy trimester and postpartum quarter. For pregnant women, mean gestational age at the time of death by suicide was 21.0 (standard deviation [SD] 10.3) weeks, and median gestational age was 23.5 (interquartile range [IQR] 12–29) weeks. For postpartum women, the mean postpartum age at the time of death by suicide was 29.8 (SD 14.5) weeks, and median postpartum age was 29 (IQR 18–45) weeks. Data values below 6 are considered nonreportable, to avoid the possibility of identifying specific individuals; these are reported here as “< 6”.

The most common means of suicide for perinatal women was hanging (33.3% [17/51]), followed by jumping or falling (19.6% [10/51]); this differed from the distribution among women who died by suicide non-perinatally, among whom overdose was the leading cause of death (Appendix 6, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.170088/-/DC1). Women who died by suicide perinatally were slightly younger than those who died by suicide non-perinatally and were more likely to have a partner; neither neighbourhood income quintile nor community size differed between these 2 groups (Table 2).

Table 2:

Demographic and psychiatric history characteristics for women who died by suicide, by group (perinatal, non-perinatal and matched living perinatal controls)

| Characteristic | Group; no. (%) of women* | Comparison; p value† | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

||||

| Perinatal suicide (n = 51) | Non-perinatal suicide (n = 1597) | Perinatal control (n = 255) | Perinatal suicide v. non-perinatal suicide | Perinatal suicide v. perinatal control | |

| Age, yr, mean ± SD | 28.4 ± 6.9 | 34.2 ± 7.8 | 28.4 ± 6.9 | < 0.001 | NA |

|

| |||||

| Marital status | 0.02 | NA | |||

|

| |||||

| Married or cohabiting | 27 (52.9) | 351 (22.0) | 0 | ||

|

| |||||

| Single, divorced or widowed | 10 (19.6) | 755 (47.3) | 0 | ||

|

| |||||

| Unknown | 14 (27.5) | 491 (30.7) | 255 (100) | ||

|

| |||||

| Community size‡ | 0.2 | 0.2 | |||

|

| |||||

| > 1 500 000 | 17 (33.3) | 678 (42.5) | 129 (50.6) | ||

|

| |||||

| 500 000–1 499 999 | NR | 171 (10.7) | 13 (5.1) | ||

|

| |||||

| 100 000–499 999 | 16 (31.4) | 409 (25.6) | 63 (24.7) | ||

|

| |||||

| 10 000–99 999 | NR | 125 (7.8) | 14 (5.5) | ||

|

| |||||

| < 10 000 (rural) | 12 (23.5) | 202 (12.6) | 34 (13.3) | ||

|

| |||||

| Neighbourhood income quintile | 0.7 | 0.5 | |||

|

| |||||

| Q1 (lowest) | 17 (33.3) | 479 (30.0) | 66 (25.9) | ||

|

| |||||

| Q5 (highest) | 10 (19.6) | 266 (16.7) | 50 (19.6) | ||

|

| |||||

| Psychiatric admissions in past 3 yr, median (range) | 0 (0–8) | 0 (0–30) | 0 (0–1) | 0.6 | < 0.001 |

|

| |||||

| Psychiatric diagnoses in past 5 yr | |||||

|

| |||||

| Psychotic disorder | NR | 329 (20.6) | NR | 0.06 | < 0.001 |

|

| |||||

| Major mood disorder | 26 (51.0) | 978 (61.2) | 17 (6.7) | 0.1 | < 0.001 |

|

| |||||

| Anxiety or related disorder | 38 (74.5) | 1357 (85.0) | 120 (47.1) | 0.04 | < 0.001 |

|

| |||||

| Alcohol or substance use–related | 19 (37.3) | 545 (34.1) | 14 (5.5) | 0.6 | < 0.001 |

|

| |||||

| Eating disorder | 8 (15.7) | 358 (22.4) | 23 (9.0) | 0.3 | 0.2 |

|

| |||||

| Personality disorder | 12 (23.5) | 417 (26.1) | NR | 0.7 | < 0.001 |

|

| |||||

| Adjustment disorder | 14 (27.5) | 319 (20.0) | 8 (3.1) | 0.2 | < 0.001 |

|

| |||||

| No. of psychiatric comorbidities | 0.6 | < 0.001 | |||

|

| |||||

| 0 | 7 (13.7) | 174 (10.9) | 121 (47.5) | ||

|

| |||||

| 1 | 10 (19.6) | 276 (17.3) | 100 (39.2) | ||

|

| |||||

| 2 | 9 (17.6) | 298 (18.7) | 23 (9.0) | ||

|

| |||||

| 3 | 25 (49.0) | 849 (53.2) | 11 (4.3) | ||

|

| |||||

| Deliberate self-harm attempts§ | |||||

|

| |||||

| Past 1 yr | 6 (11.8) | 258 (16.2) | NR | 0.4 | < 0.001 |

|

| |||||

| Past 1–3 yr | 6 (11.8) | 171 (10.7) | NR | 0.8 | < 0.001 |

|

| |||||

| No. of aggregated diagnostic groups in past 3 yr, mean ± SD | 1.10 ± 0.9 | 1.34 ± 1.3 | 0.70 ± 0.9 | 0.2 | 0.003 |

Note: NA = not applicable (groups matched on maternal age) or not available, NR = not reportable because of small n value (< 6), SD = standard deviation.

Except where indicated otherwise.

Continuous variables were compared using independent and paired t tests for unmatched and matched comparisons, respectively; categorical variables were compared using χ2 tests of association.

For each group, the sum of data is less than the total number because of missing data or data that could not be reported because of small values.

Available after 2002.

Women who died by suicide in the perinatal period had prior medical morbidity (as indicated by mean aggregated diagnosis groups) similar to that of the non-perinatal suicide group, but greater than that of matched living perinatal controls (Table 2). The majority who died by suicide, regardless of group, had an affective or anxiety and related disorder, rather than a psychotic disorder. The distribution of psychiatric diagnoses in the 5 years preceding the suicide (or matched index date for perinatal controls) was similar for the 2 groups who died, whereas the living perinatal women had much lower rates of prior psychiatric morbidity. A similar pattern was observed for psychiatric hospitalizations and history of suicide attempts (Table 2).

About 70.6% (36/51) of perinatal women who died by suicide had mental health contact in the year before suicide, with only 39.2% (20/51) having mental health contact in the 30 days before. This level of contact was not significantly different from that for the women who died by suicide non-perinatally. However, there were differences when such contact was broken down by type of provider. Women who died by suicide perinatally were less likely to have seen a psychiatrist (OR 0.37, 95% CI 0.17–0.79), but more likely to have seen a primary care provider for a mental health reason (OR 1.80, 95% CI 1.03–3.16) within the year before suicide compared with women who died by suicide non-perinatally. Perinatal women who died by suicide were far more likely to have had contact with a mental health provider in the year before suicide than living perinatal controls at their matched index date (70.6% v. 21.6%, OR 8.73, 95% CI 4.34–17.6; Table 3). Compared with matched living perinatal women, perinatal women who died by suicide had similar likelihood of non–mental health primary care (32.5% v. 29.4%; OR 0.86, 95% CI 0.44–0.71) and obstetric care (67.0% v. 40.0%; OR 0.33, 95% CI 0.10–1.11) at 30 days before death, but lower likelihood of pediatric contact (64.5% v. 88.4%; OR 0.24, 95% CI 0.10–0.58) (Table 4).

Table 3:

Mental health contact with health care providers

| Mental health contact* | No. (%) of women | Comparison; OR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perinatal suicide v. non-perinatal suicide | Perinatal suicide v. perinatal controls | ||

| Any contact | |||

| Within previous yr | |||

| Perinatal suicide (n = 51) | 36 (70.6) | 0.73 (0.40–1.36) | 8.73 (4.34–17.6) |

| Non-perinatal suicide (n = 1597) | 1223 (76.6) | 1.00 (ref) | – |

| Perinatal controls (n = 255) | 55 (21.6) | – | 1.00 (ref) |

| Within past 30 d | |||

| Perinatal suicide (n = 51) | 20 (39.2) | 0.71 (0.40–1.25) | NR |

| Non-perinatal suicide (n = 1597) | 762 (47.7) | 1.00 (ref) | – |

| Perinatal controls (n = 255) | NR | – | 1.00 (ref) |

| With psychiatrist | |||

| Within previous yr | |||

| Perinatal suicide (n = 51) | 8 (15.7) | 0.37 (0.17–0.79) | NR |

| Non-perinatal suicide (n = 1597) | 535 (33.5) | 1.00 (ref) | – |

| Perinatal controls (n = 255) | NR | – | 1.00 (ref) |

| Within past 30 d | |||

| Perinatal suicide (n = 51) | NR | NR | NR |

| Non-perinatal suicide (n = 1597) | 371 (23.2) | 1.00 (ref) | – |

| Perinatal controls (n = 255) | NR | – | 1.00 (ref) |

| With primary care provider | |||

| Within previous yr | |||

| Perinatal suicide (n = 51) | 28 (54.9) | 1.80 (1.03–3.16) | 4.99 (2.52–9.89) |

| Non-perinatal suicide (n = 1597) | 644 (40.3) | 1.00 (ref) | – |

| Perinatal controls (n = 255) | 50 (19.6) | – | 1.00 (ref) |

| Within past 30 d | |||

| Perinatal suicide (n = 51) | 10 (19.6) | 1.06 (0.52–2.14) | NR |

| Non-perinatal suicide (n = 1597) | 299 (18.7) | 1.00 (ref) | – |

| Perinatal controls (n = 255) | NR | – | 1.00 (ref) |

Note: CI = confidence interval, NR = not reportable because of small n value (< 6), OR = odds ratio.

Mental health contact before suicide for perinatal and non-perinatal groups, and before matched index date for perinatal controls.

Table 4:

Non–mental health contact with health care providers among perinatal women

| Non–mental health contact* | No. (%) of women | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| With primary care provider | ||

| Within previous yr | ||

| Perinatal controls (n = 255) | 228 (89.4) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Perinatal suicide (n = 51) | 45 (88.2) | 0.89 (0.34–2.29) |

| Within past 30 d | ||

| Perinatal controls (n = 255) | 83 (32.5) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Perinatal suicide (n = 51) | 15 (29.4) | 0.86 (0.44–1.71) |

| With obstetrician | ||

| Within previous yr | ||

| Perinatal controls (n = 255) | 223 (87.5) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Perinatal suicide (n = 51) | 44 (86.3) | 0.90 (0.41–1.96) |

| Within past 30 d (pregnant only) | ||

| Pregnant controls (n = 100) | 67 (67.0) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Pregnant suicide (n = 20) | 8 (40.0) | 0.33 (0.10–1.11) |

| With pediatrician (for child, postpartum only) | ||

| Within previous yr | ||

| Postpartum controls (n = 155) | 147 (94.8) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Postpartum suicide (n = 31) | 24 (77.4) | 0.19 (0.06–0.56) |

| Within past 30 d | ||

| Postpartum controls (n = 155) | 137 (88.4) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Postpartum suicide (n = 31) | 20 (64.5) | 0.24 (0.10–0.58) |

Note: CI = confidence interval, OR = odds ratio.

Non–mental health contact among perinatal women only (those who died by suicide and living controls).

Interpretation

We observed a perinatal suicide rate of 2.58 per 100 000 live births, and found that 1 of every 19 maternal deaths in Ontario was attributable to suicide. One key finding was that deaths occurred across the perinatal period. Also, women who died by suicide perinatally tended to use more lethal means than women who died by suicide non-perinatally. Furthermore, fewer than half of the women who died by suicide during pregnancy or the postpartum period had mental health service use in the 30 days before death, although a substantial proportion had contact with other health care professionals, such as obstetricians and pediatricians.

The rate of suicide during pregnancy and the postpartum period as reported here lies between rates in the United Kingdom and the United States (2 and 3 per 100 000, respectively).2,5 A strength of our work was the combined model, whereby we collected data from multiple sources; this approach may more accurately reflect the numbers of deaths by suicide perinatally in Ontario than using data from just one source.

Our findings with regard to the timing of suicide in the perinatal period are consistent with those of a smaller study examining maternal deaths in the first year postpartum, which found that many suicides occur late in the postpartum period (9–12 mo after birth).28 In our study, postpartum deaths occurred most frequently after the first 12 weeks, particularly after the sixth month postpartum. This is an important finding, given that many definitions of postpartum depression are restricted to women who gave birth within the past month, and maternal mortality up to 6 weeks postpartum is usually considered to be related to childbirth.

The characteristics of women who died by suicide perinatally are important. The more lethal means of suicide in the perinatal group (i.e., hanging or jumping) relative to the non-perinatal group (i.e., overdose) is consistent with previous reports.2,28–31 These findings suggest that perinatal women who are suicidal may be at higher risk for suicide completion than women outside the perinatal period. Similar to research in other countries,32 most of the women who died perinatally had a mood or anxiety disorder, rather than a psychotic disorder. This serves as a reminder not to underestimate the possible serious consequences of nonpsychotic postpartum mental disorders. Consistent with the literature, most of the women who died by suicide had mental health issues (i.e., the perinatal group had significantly more psychiatric comorbidities than the living perinatal controls), which suggests that many of the women at risk could be identified from their psychiatric history.

One potential risk factor that emerged here and that requires further research is geographic region: women in the North West LHIN of Ontario more often died by suicide than was the case in other regions, although the difference was not statistically significant. The North West LHIN is the largest in Ontario in terms of land mass, yet it accounts for the lowest percentage of the population. Women in this region, regardless of perinatal status, may be more likely to die by suicide than women in any other region, which perhaps speaks to isolation or lack of access to care, hypotheses that would need to be tested directly. Given that about 21% of residents in this region are of Aboriginal ancestry (close to double that in other regions, according to 2006 data),33 further exploration is required.

These characteristics may serve to inform prevention programs geared to identifying perinatal women at risk.34 Unfortunately, the low rates of mental health contact in the time leading up to suicide that we observed are also consistent with those of research in other jurisdictions; for example, in a recent UK study, women were found not to be in treatment around the time of death.30 Few studies have examined non–mental health contact before suicide. The higher rates of contact with non–mental health providers that we observed suggest that tailored suicide interventions for the perinatal population should be geared to family practice and to obstetric and pediatric settings.

Limitations

The limitations of this study included small sample size, which limited our ability to comment on potential differences in suicide rates between pregnant women and those in the postpartum period. Our analysis was also limited by aspects of the data sources. For example, when there were discrepancies between data sources, we reviewed individual cases, but data from the coroner’s office and from ICES are complex and not always complete. We may have undercounted the number of pregnancies if pregnancy data for some women were not captured in the databases. Our diagnostic data may not have been completely accurate, because we used database sources, although our findings were consistent with the literature. We were unable to examine other forms of mental health service use, such as therapy with psychologists or other providers not covered by the provincial health insurance plan. However, contact with primary care providers indicates that these women were in the system and could potentially have been monitored continuously by primary care providers.

Conclusion

The World Health Organization, recognizing that suicide has not been a public health priority, has identified death from suicide as imperative for study worldwide.35 With 1 in 19 maternal deaths attributable to suicide in Ontario, the findings of our study suggest that there is room to improve engagement of pregnant and postpartum women in perinatal mental health services. Moreover, our suicide surveillance and mental health intervention efforts must focus on pregnancy and must continue well into the first postpartum year.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the office of the Chief Coroner of Ontario. The authors also thank Lana Mamisashvili, Jaclyn Cappell, Allison Eady and Miki Peer for their valuable contributions to this work.

Footnotes

CMAJ Podcasts: author interview at https://soundcloud.com/cmajpodcasts/170088-res

Visual abstract available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.170088/-/DC2

Competing interests: Sophie Grigoriadis has received personal fees from Sage, Eli Lilly Canada, Allergan/Actavis, Pfizer and Bristol Myers Squibb for activities unrelated to the current manuscript. No other competing interests were declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Sophie Grigoriadis and Simone Vigod conceived and designed the study, obtained funding, directed data acquisition and analysis, interpreted the data and wrote the draft manuscript. Andrew Wilton analyzed the data and assisted with its interpretation, reviewed the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and takes particular responsibility for the data analysis. Paul Kurdyak, Anne Rhodes, Anthony Levitt and Amy Cheung substantially contributed to study design and analysis and interpretation of the data and reviewed the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. Emily VonderPorten had a substantial role in data acquisition, drafting and revising the manuscript. All of the authors gave final approval of the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: This study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (FRN 115439).

Disclaimer: This study received support from the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES), which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC). The opinions, results and conclusions reported in this paper are those of the authors and are independent from the funding sources, ICES and MOHLTC. No endorsement by ICES or the MOHLTC is intended or should be inferred. Parts of this material are based on data and information compiled and provided by the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI). However, the analyses, conclusions, opinions and statements expressed herein are those of the authors, and not necessarily those of CIHI. The study funder did not have any role in study design; collection, analysis or interpretation of the data; writing of the report; or the decision to submit the article for publication. The researchers are independent from the funder.

References

- 1.Oates M. Perinatal psychiatric disorders: a leading cause of maternal morbidity and mortality. Br Med Bull 2003;67:219–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oates M. Suicide: the leading cause of maternal death. Br J Psychiatry 2003; 183:279–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lewis G, editor. Saving mothers’ lives: reviewing maternal deaths to make motherhood safer — 2003–2005. Seventh Report on Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom. London (UK): The Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Austin MP, Kildea S, Sullivan E. Maternal mortality and psychiatric morbidity in the perinatal period: challenges and opportunities for prevention in the Australian setting. Med J Aust 2007;186:364–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Palladino CL, Singh V, Campbell J, et al. Homicide and suicide during the perinatal period: findings from the National Violent Death Reporting System. Obstet Gynecol 2011;118:1056–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turner LA, Kramer MS, Liu S. Cause-specific mortality during and after pregnancy and the definition of maternal death. Chronic Dis Can 2002;23:31–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems. 10th revision. 4th ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meltzer-Brody S, Stuebe A. The long-term psychiatric and medical prognosis of perinatal mental illness. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2014;28:49–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cliffe S, Black D, Bryant J, et al. Maternal deaths in New South Wales, Australia: a data linkage project. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol 2008;48:255–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horon IL, Cheng D. Effectiveness of pregnancy check boxes on death certificates in identifying pregnancy-associated mortality. Public Health Rep 2011;126: 195–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schuitemaker N, Van Roosmalen J, Dekker G, et al. Underreporting of maternal mortality in The Netherlands. Obstet Gynecol 1997;90:78–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horon IL. Underreporting of maternal deaths on death certificates and the magnitude of the problem of maternal mortality. Am J Public Health 2005;95:478–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deneux-Tharaux C, Berg C, Bouvier-Colle MH, et al. Underreporting of pregnancy-related mortality in the United States and Europe. Obstet Gynecol 2005;106:684–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stewart DE. A broader context for maternal mortality. CMAJ 2006;174:302–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patrick K. It’s time to put maternal suicide under the microscope. CMAJ 2013; 185:1115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Juurlink DPC, Croxford R, Chong A, et al. Canadian Institute for Health Information Discharge Abstract Database: a validation study. Toronto: Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kurdyak P, Lin E, Green D, et al. Validation of a population-based algorithm to detect chronic psychotic illness. Can J Psychiatry 2015;60:362–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kisely S, Lin E, Gilbert C, et al. Use of administrative data for the surveillance of mood and anxiety disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2009;43:1118–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bethell J, Rhodes AE. Identifying deliberate self-harm in emergency department data. Health Rep 2009;20:35–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hirdes JP, Smith TF, Rabinowitz T, et al. The Resident Assessment Instrument–Mental Health (RAI-MH): inter-rater reliability and convergent validity. J Behav Health Serv Res 2002;29:419–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williams J, O’Brien BJ, Sellors C, et al. A summary of studies on the quality of health care administrative databases in Canada. In: Goel V, Williams JI, Anderson GM, et al., editors. Patterns of health care in Ontario: the ICES practice atlas. Ottawa: Canadian Medical Association; 1996:339–45. [Google Scholar]

- 22.You JJ, Alter DA, Stukel TA, et al. Proliferation of prenatal ultrasonography. CMAJ 2010;182:143–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maaten S, Guttmann A, Kopp A, et al. Care of women during pregnancy and childbirth. In: Jaakkimainen L, Upshur R, Klein-Geltink JE, et al., editors. Primary care in Ontario: ICES atlas. Toronto: Institute of Clinical Evaluative Sciences; 2006:15–34. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weiner J, editor. The Johns Hopkins ACG case-mix system documentation and application manual. Version 5.0. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University School of Public Health; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fontanella CA, Warner LA, Hiance-Steelesmith DL, et al. Service use in the month and year prior to suicide among adults enrolled in Ohio Medicaid. Psychiatr Serv 2017;68:674–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steele LS, Glazier RH, Lin E, et al. Using administrative data to measure ambulatory mental health service provision in primary care. Med Care 2004;42:960–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.GeoSuite, reference guide. Census year 2011. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2012. Cat. no. 92-150-G. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thornton C, Schmied V, Dennis CL, et al. Maternal deaths in NSW (2000–2006) from nonmedical causes (suicide and trauma) in the first year following birth. Biomed Res Int 2013:623743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lindahl V, Pearson JL, Colpe L. Prevalence of suicidality during pregnancy and the postpartum. Arch Womens Ment Health 2005;8:77–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khalifeh H, Hunt IM, Appleby L, et al. Suicide in perinatal and non-perinatal women in contact with psychiatric services: 15 year findings from a UK national inquiry. Lancet Psychiatry 2016;3:233–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Curtin SC, Warner M, Hedegaard H. Increase in suicide in the United States, 1999–2014. NCHS Data Brief No. 241 Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics; 2016. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db241.htm (accessed 2017 May 19). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gold KJ, Singh V, Marcus SM, et al. Mental health, substance use and intimate partner problems among pregnant and postpartum suicide victims in the National Violent Death Reporting System. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2012;34:139–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patychuk D, Smith K; Steps to Equity. Demographic analysis of Ontario’s sub-LHIN populations: supporting AOHC research to enhance access for people experiencing barriers to care. North York (ON): Association of Ontario Health Centers; 2010. Available: www.ruralontarioinstitute.ca/file.aspx%3Fid%3Dface11e6-30f9-4a8da59d-8a55dfdcc0ac (accessed 2017 Apr. 21). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fontanella CA, Hiance-Steelesmith DL, Phillips GS, et al. Widening rural–urban disparities in youth suicides, United States, 1996–2010. JAMA Pediatr 2015; 169:466–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Preventing suicide: a global imperative. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014. Available: www.who.int/mental_health/suicide-prevention/world_report_2014/en/ (accessed 2016 Mar. 11). [Google Scholar]