Abstract

Life as we know it, simply would not exist without DNA replication. All living organisms utilize a complex machinery to duplicate their genomes and the central role in this machinery belongs to replicative DNA polymerases, enzymes that are specifically designed to copy DNA. “Hassle-free” DNA duplication exists only in an ideal world, while in real life, it is constantly threatened by a myriad of diverse challenges. Among the most pressing obstacles that replicative polymerases often cannot overcome by themselves, are lesions that distort the structure of DNA. Despite elaborate systems that cells utilize to cleanse their genomes of damaged DNA, repair is often incomplete. The persistence of DNA lesions obstructing the cellular replicases can have deleterious consequences. One of the mechanisms allowing cells to complete replication is “Translesion DNA Synthesis (TLS). TLS is intrinsically error-prone, but apparently, the potential downside of increased mutagenesis is a healthier outcome for the cell than incomplete replication. Although most of the currently identified eukaryotic DNA polymerases have been implicated in TLS, the best characterized are those belonging to the “Y-family” of DNA polymerases (pols η, ι, κ, and Rev1), which are thought to play major roles in the TLS of persisting DNA lesions in coordination with the B-family polymerase, pol ζ. In this review, we summarize the unique features of these DNA polymerases by mainly focusing on their biochemical and structural characteristics, as well as potential protein-protein interactions with other critical factors affecting TLS regulation.

Keywords: translesion synthesis, replicative bypass, DNA polymerase families, PCNA, ubiquitin, protein interaction network, mutagenesis

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

According to a very simplistic perception of life, the proper assembly of each living organism from a set of molecules relies on an instruction manual encoded in DNA, a double-stranded helix composed of a string of nucleotides. The information written in this manual must be accurately copied before being transferred from generation to generation. The mechanism that ensures the preservation of genetic information is based on the strict specificity of nucleotide base pairing (A with T and G with C) across the shared axis of the double helix. Watson and Crick, who are credited with discovering the molecular structure of DNA, mentioned that specific pairing itself “immediately suggests a possible copying mechanism for the genetic material” (Watson and Crick, 1953). Moreover, they even assumed that base complementarity is the driving force strong enough to guide incoming nucleotides for pairing with the parental DNA strand without the assistance of any enzyme. However, as with any other chemical reaction within a cell, DNA replication depends on the help from an extra set of hands. In fact, an elaborate machinery is required to accomplish the duplication of genomic DNA and the role of a “right-hand” in this process belongs to replicative DNA polymerases, the enzymes specifically designed to copy DNA with high efficiency and accuracy. This task is challenged by a large variety of external and internal damaging agents that constantly threaten DNA stability and obscure the ability of DNA polymerases to read the information written in DNA. In order to overcome such obstacles, cells rely on multiple repair mechanisms that have evolved to restore the integrity of damaged sequences. When repair is incomplete, i.e., when lesions are refractory to repair, or their number is simply overwhelming, cells utilize damage tolerance mechanisms in order to survive. Similar to DNA replication, both DNA repair and damage tolerance depends on DNA polymerases each playing a specific role in copying or replacing modified genomic sequences.

Virtually all of the eukaryotic DNA polymerases characterized in vitro appear able to traverse past damaged DNA sites in a process called translesion DNA synthesis (TLS), although with vastly different efficiencies, and fidelities, and often with the help of protein partners. High fidelity replicative polymerases are the least adept to perform this function. In contrast, reasonably efficient bypass synthesis in eukaryotes has been demonstrated for the A-family polymerases (pols θ and ν), X-family polymerases (pols β, λ, and μ) and the newest addition to the TLS polymerase family, PrimPol. However, within the TLS polymerase superfamily, there is a group of enzymes that appear to be specifically designed to accomplish the lesion bypass task most effectively. The majority of these enzymes comprise the Y-family of DNA polymerases (Ohmori et al., 2001). Mammalian and yeast representatives of the eukaryotic Y-family DNA polymerases, i.e., pols η, ι, κ and Rev1 are the main subject matter of the current review. In addition, when describing specialized TLS polymerases, one cannot avoid inclusion of the phylogenetically unrelated B-family DNA polymerase, pol ζ, which is an indispensable component of the DNA damage tolerance machinery in eukaryotic cells.

In the past two decades, we have witnessed a rapid expansion of TLS research and multiple comprehensive review papers focusing on the various aspects of the TLS mechanism and biological functions of the TLS polymerases have been published [relevant reviews published during the past five last years include: (Boiteux and Jinks-Robertson, 2013; Fuchs and Fujii, 2013; Goodman and Woodgate, 2013; Guengerich et al., 2015; Hedglin and Benkovic, 2015; Ishino and Ishino, 2014; Jansen et al., 2015; Lambert and Lambert, 2015; Malkova and Haber, 2012; Maxwell and Suo, 2014; McIntyre and Woodgate, 2015; Nicolay et al., 2012b; Sale, 2013; Salehan and Morse, 2013; Sharma and Canman, 2012; Sharma et al., 2013; Tomasso et al., 2014; Yang et al., 2013; Yang, 2014)]. In the current review, we intend to present the major recent findings by putting them in an historical context and by focusing on the development of the ideas leading to the current understanding of TLS. We will mainly discuss biochemical and structural studies of the TLS polymerases themselves, as well as their interactions with major regulatory proteins affecting their activation of TLS [for the reviews on a growing body of literature regarding other means of their regulation, such as transcription, inactivation, or proteasomal degradation see (McIntyre and Woodgate, 2015; Sale et al., 2012)].

Historic overview

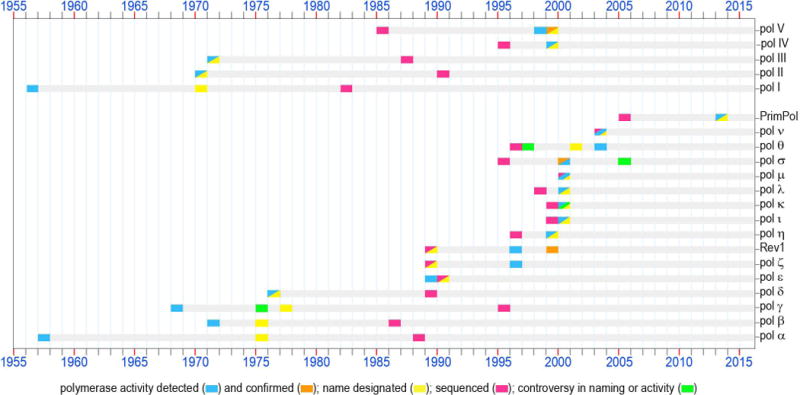

Before we begin our journey into the exciting world of translesion DNA polymerases, we wanted to take the liberty of presenting a very brief overview of the discoveries of all types of prokaryotic and eukaryotic DNA polymerases, which will illustrate why detection of the TLS polymerases was a paradigm-changing event for scientists working in the field.

The existence of a substance in a cell’s nucleus which we now call DNA, was first revealed in 1869 by Friedrich Miescher [for an excellent review see (Hübscher et al., 2010)]. It took about eight decades to unequivocally prove that this polynucleotide serves as the storage material for genetic information in all living organisms (Avery et al., 1944; Hershey and Chase, 1952). By the early 1950s, the chemical (Chargaff, 1951) and molecular (Watson and Crick, 1953) structure of DNA was uncovered and consequently a possible mechanism for copying the genetic material was proposed. Just three years after Watson and Crick reported the double-helical structure of DNA, the first enzyme able to catalyse replication of a DNA chain was identified (Kornberg et al., 1956) (Figure 1). This discovery was made by a group of scientists led by Arthur Kornberg, who believed that “a biochemist devoted to enzymes could reconstitute any metabolic event in the test tube as well as, or even better than, the cell does it”. Indeed, Kornberg and his colleagues succeeded in the reconstitution of the DNA synthesis reaction with purified components, which besides the DNA polymerase included a primed DNA template, Mg2+ and four deoxynucleotides. This approach is still widely used not only for the direct identification of the enzymes with the ability to synthesize DNA, but also to study the biochemical properties of DNA polymerases and to define the conditions that are required to ensure their optimal performance.

Figure 1. DNA polymerases: 60 years of discoveries.

1956 – The first enzyme capable of copying DNA was discovered in E.coli extracts and was assumed at that time to be the only bacterial DNA polymerase (Kornberg et al., 1956). Later, when a second E. coli DNA polymerase was purified, this enzyme which plays an important role in prokaryotic DNA replication and repair was named pol I. The polA gene was sequenced in 1982 (Joyce et al., 1982) (accession P00582a).

1957 – The first eukaryotic DNA polymerase was identified (Bollum and Potter, 1957). When the uniform nomenclature was adopted in 1975, this enzyme was appropriately designated as pol α. Originally assumed to bear the sole responsibility for DNA synthesis in mammalian cells, this polymerase instead plays a key role in the initiation of chromosomal replication. The POLA gene was sequenced in 1988 (Wong et al., 1988) (accession CAA29920).

1968 – An enzyme with DNA polymerase activity was isolated from the rat liver mitochondria (Kalf and Ch’ih, 1968; Meyer and Simpson, 1968). This enzyme, known since 1977 as pol γ (Bolden et al., 1977) is a major polymerase dealing with all transactions involving mitochondrial DNA in mammalian cells. The POLG gene was sequenced in 1995 (Ropp and Copeland, 1995) (accession CAA88012).

1970 – A second DNA polymerase was discovered in E.coli by several groups in the USA and Germany (Knippers, 1970; Kornberg and Gefter, 1970; Moses and Richardson, 1970). According to the chronological order of discovery, it was named pol II. The sequencing of the polB gene was accomplished in 1990 (Chen et al., 1990) (accession P21189).

1971 – During the course of purification of E.coli pol II, a third prokaryotic DNA polymerase was detected (Kornberg and Gefter, 1971). DNA polymerase III is now known to be the main prokaryotic replicative polymerase. The dnaE gene encoding the catalytic α-subunit of pol III was sequenced in 1987 (Tomasiewicz and McHenry, 1987) (accession P10443).

- A second eukaryotic nuclear DNA polymerase later named pol β, was identified in mammalian cells and tissues practically simultaneously by several laboratories in the USA and England (Baril et al., 1971; Berger et al., 1971; Chang and Bollum, 1971; Haines et al., 1971; Weissbach et al., 1971). Very soon, it became apparent that this polymerase does not play a direct role in DNA replication. Instead, extensive research conducted by various groups revealed a major role for DNA pol β in base-excision repair. The POLB gene was sequenced in 1986 (Zmudzka et al., 1986) (accession P06766).

1974 – A formal nomenclature designating each mammalian DNA polymerase with a Greek symbol was proposed in 1974 and accepted by attendees of the international conference on eukaryotic DNA polymerases in 1975 (Weissbach et al., 1975). According to the established nomenclature, the first two mammalian DNA polymerases were designated pols α and β. It is worth noting that the third DNA polymerase which was given the name pol γ was and a forth DNA polymerase found in mitochondria (designated DNA polymerase-mt) were later shown to be identical and the name pol γ has been retained for this mitochondrial polymerase (Bolden et al., 1977).

1976 – The first nuclear polymerase containing an associated 3′→5′ exonuclease activity was purified and called pol δ (Byrnes et al., 1976). Later, this polymerase was shown to be an essential component of the eukaryotic replication machinery. The sequencing of the POLD1 gene was accomplished in 1989 (Boulet et al., 1989) (accession P15436).

1987 – It was proposed that DNA polymerases should be classified into discrete families based on their evolutionary relatedness. The first two evolutionary groups of DNA polymerases were designated as polymerase families A- and B- according to the amino acid homology to E coli pols I and II, respectively (Jung et al., 1987). In 1991 two additional groups typified by the catalytic subunit of E coli pols III and eukaryotic pol β were designated as families C- and X-, respectively (Ito and Braithwaite, 1991). In 1999 family D- was proposed to group polymerases involved in the DNA replication machinery of the Euryarchaeota (Cann and Ishino, 1999). In 2001, proteins originally defined as belonging to the UmuC/DinB/Rev1/Rad30 superfamily and involved in mutagenesis and TLS DNA synthesis were designated as Y-family polymerases (Ohmori et al., 2001).

1989 – The fourth nuclear DNA polymerase in mammalian cells, pol ε, was first reported as a PCNA-independent form of pol δ (Focher et al., 1989). Subsequently, this enzyme was recognized as a distinct DNA polymerase and accordingly it was named pol ε. Similar to pol δ, pol ε is equipped with 3′→5′ exonuclease proofreading activity and is essential for replication of the eukaryotic genome. The POLE1 gene was sequenced in 1990 (Morrison et al., 1990) (accession P21951).

1996 – Saccharomyces cerevisiae DNA pol ζ was characterized as a complex of Rev3 and Rev7 proteins (Nelson et al., 1996b). These studies confirmed the hypothesis that the Rev3 gene long known to be involved in damage-induced and spontaneous mutagenesis, encodes the first DNA polymerase specializing in TLS (Morrison et al., 1989) (accession P14284). This prediction was made based on the homology of Rev3 to other genes encoding B-family DNA polymerases.

- In the same year, the same group discovered dCMP transferase activity for the S. cerevisiae REV1 protein (Nelson et al., 1996a) that was known at the time to be required for the damage-induced mutagenesis and having ~25% identity with the E.coli UmuC protein (Larimer et al., 1989) (accession P12689). It was proposed that the CMP transferase function was important for mutagenic TLS involving pol ζ. However, Rev1 was not recognized as belonging to the broad superfamily of DNA-dependent DNA polymerases until 1999, when deoxynucleotidyl transferase activity was detected in several enzymes homologous to REV1.

1998 – The first evidence suggesting that the E. coli UmuD’2C complex consisting of the umuDC gene products (Perry et al., 1985; Kitagawa et al., 1985) (accession P04152), is a DNA polymerase was demonstrated (Tang et al., 1998). At that time, it was shown that in vitro the UmuD’2C complex could copy an abasic site-containing DNA template without the assistance of any other polymerase, although the possibility of contamination with trace amounts of other DNA polymerase were not entirely ruled out. A year later, additional biochemical studies unequivocally confirmed that the UmuD’2C complex is a bona fide DNA polymerase designated as E.coli pol V (Tang et al., 1999).

1999 –The S.cerevisiae RAD30 gene which was previously identified by sequence homology to prokaryotic UmuC and DinB in 1996 (Kulaeva et al., 1996; McDonald et al., 1997) was shown to encode DNA polymerase η (Johnson et al., 1999b). Shortly thereafter, human polymerase η was characterized (Masutani et al., 1999b). Polη became one of the founding members of the new Y-family of DNA polymerases (Ohmori et al., 2001). Nonsense, or frameshift mutations in the gene (RAD30A, POLH, XPV) encoding pol η are responsible for the Xeroderm Pigmentosum Variant syndrome in humans (Johnson et al., 1999a; Masutani et al., 1999b).

- The same week that the DNA polymerase activity of the UmuD’2C encoded pol V was confirmed, a manuscript describing the TLS activity of E.coli DinB was published (Wagner et al., 1999). This polymerase became known as E.coli DNA pol IV. The dinB gene was originally identified as dinP in 1995 (Ohmori et al., 1995) (accession BAA07593) and despite being shown to be allelic with dinB in 1999 the name of dinP, rather than the correct name of dinB, is still often used in Genbank data files describing related proteins.

2000 –The TLS activity of two eukaryotic Y-family polymerases ι (Tissier et al., 2000b) and κ (Ohashi et al., 2000a) (products of the POLI (RAD30B) and POLK (DINB1) genes, respectively) was demonstrated a year after they were cloned (Gerlach et al., 1999; McDonald et al., 1999) [accession numbers AAD50381 (pol ι) and AAF02541 pol κ)].

- Three X-family polymerases implicated in participating in different types of DNA transactions (such as BER, non-homologous end joining repair, V(D)J recombination, TLS, and sister chromatid cohesion) were discovered. This includes pol λ (Garcia-Diaz et al., 2000) (the sequence was first submitted in 1998 (Blanco, 1998) [accession number CAB65241]), pol μ (Dominguez et al., 2000) (accession CAB65075), and pol σ (Wang et al., 2000) (first sequenced in 1995 (Sadoff et al., 1995) accession P53632). It should be noted that the DNA polymerase activity of pol σ has been contested by Haracska et al., (Haracska et al., 2005b), who suggest that the protein is actually a poly-A RNA polymerase, rather than a bona fide DNA polymerase.

2003 – Two mammalian A-family DNA polymerases that are homologous to the DNA cross-link sensitivity protein Mus308 and implicated in different defense pathways against DNA damage were identified and characterized; pol θ (Seki et al., 2003) and pol ν (Marini et al., 2003). It worth mentioning that pol θ, the only polymerase known to contain a helicase domain, was first identified in 1997 in the genomes of a variety of eukaryotic organisms based on sequence homology to E. coli DNA pol I (Harris et al., 1996; Sharief et al., 1999; Sonnhammer and Wootton, 1997) (accession numbers AAB67306 and AAC33565). The polymerase was originally named pol η (Burtis and Harris, 1997), but was later renamed pol θ (Burgers et al., 2001). Pol ν was sequenced in 2003 (Marini et al., 2003) (accession NP_861524).

2013 – An ability to replicate both damaged and undamaged DNA templates was detected in PrimPol, an enzyme belonging to the archaeal-eukaryotic primase superfamily (Bianchi et al., 2013; García-Gómez et al., 2013). The gene encoding PrimPol was first sequenced in 2005 (Iyer et al., 2005) (accession NP_689896). The ability to catalyze TLS is only one of the broad enzymatic activities of the PrimPol enzymes that have been implicated in a large variety of cellular functions.

a GeneBank Sequence identifiers are listed (Clark et al., 2016).

Soon after Kornberg’s group isolated what is now known as DNA polymerase I from Escherichia coli, a protein with corresponding functions was identified in eukaryotes (Bollum and Potter, 1957). During the following 40 years of painstaking work that was conducted by multiple laboratories around the world, many more enzymes responsible for copying DNA in different organisms were discovered (Figure 1). According to the proposed classification, based upon similarities of the amino acid sequences, all known DNA-dependent DNA polymerases were originally grouped into four families; A-, B-, C-, or X- [such classification was first proposed in 1987 (Jung et al., 1987) and then updated in 1991 (Ito and Braithwaite, 1991)]. In eukaryotes, these families were represented by five DNA polymerases designated by Greek letters given to these proteins in order of their historical discovery [the formal nomenclature was adopted in 1975 (Weissbach et al., 1975)]. These five polymerases, later to be known as “classical” DNA polymerases, that were identified within the 40 years of Kornberg’s initial discovery, included components of the chromosomal replisome; pols α, δ and ε (family B); mitochondrial pol γ (family A); and the DNA repair polymerase, pol β (family X). The latest addition to the eukaryotic DNA polymerase superfamily made at the end of 40-year time span was pol ζ (family B) (Nelson et al., 1996b), a polymerase which appeared to be specifically dedicated to copying damaged genomic and mitochondrial DNA. This discovery can be considered as marking the end of the first “slow” stage in the timeline of DNA polymerase discovery and the beginning of the polymerase “boom era” when enzymes functionally similar to pol ζ, i.e. specializing in translesion DNA synthesis, came to the forefront.

In 1956, Kornberg and his colleagues assumed that the enzyme they found was the only DNA polymerase required for replication of the Escherichia coli (E. coli) genome, just as pol α was for several years considered to be the only polymerase involved in DNA replication in eukaryotic cells. By the mid-1990s, it seemed reasonable that the six eukaryotic polymerases that had been identified by that time were sufficient to fulfil all the needs related to DNA synthesis. Indeed, many DNA polymerases were known to play roles in more than one pathway related to DNA metabolism. Thus, replicative pols δ and ε are also involved in all major DNA excision-repair pathways, where they act to maintain the integrity of the genome by restoring the DNA sequence after damaged bases, or nucleotides, are removed. Both, replicative pol δ (Choi et al., 2010; Daube et al., 2000; Hirota et al., 2016; Meng et al., 2009; Narita et al., 2010; O’Day et al., 1992; Schmitt et al., 2009) and the base excision repair polymerase, pol β (Jiang et al., 2015; Vaisman and Woodgate, 2004; Villani et al., 2011; Villani et al., 2014; Xu et al., 2014) have been implicated in TLS. Even though the discovery of pol ζ hinted that cells might contain more enzymes specializing in the replication of damaged DNA, a prevailing idea was that replicative polymerases could perform this function themselves with the assistance of accessory proteins. In agreement with this idea, it was demonstrated that pol δ-catalysed replication staled at UV-induced cyclobutane thymine dimers (CPDs) can be rescued by addition of the proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), a co-factor of pol δ (Daube et al., 2000). The working hypothesis was that an interaction with accessory proteins relaxes the normally stringent fidelity of replicative polymerases, thus enabling them to insert nucleotides opposite the damaged bases in an error-prone manner and to continue DNA replication past the lesion. Among the proteins under investigation for such conduct were the products of the E. coli umuD and umuC genes, which were known to be responsible for the majority of damage-induced mutagenesis in bacterial cells (Kato and Shinoura, 1977). By the late 1990s, proteins sharing sequence homology with UmuC had been identified in various organisms from all kingdoms of life. These include DinB (Kulaeva et al., 1996; Ohmori et al., 1995), Rad30 (McDonald et al., 1997) and Rev1 (Larimer et al., 1989), which together with UmuC were proposed to comprise a superfamily of enzymes involved in both error-prone and error-free DNA damage tolerance pathway. Extensive studies aimed at uncovering the mechanism by which these supposed accessory proteins facilitated TLS culminated in the unexpected discovery that the super family of enzymes homologous to UmuC, DinB, Rad30 and Rev1 although lacking sequence similarity to any of the previously identified polymerases, all possess DNA replication activity. The first clue to such activity came from the study of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Rev1 protein, which was shown to exhibit deoxycytidyl transferase activity in vitro (Nelson et al., 1996a). The idea that the phylogenetically related proteins might possess a similar activity, or even an expanded ability to incorporate all four deoxynucleotides, went largely unexplored until the late 1990s when the difficulties with the purification of these proteins were finally overcome.

In 1998, the first report describing DNA synthesizing activity of a heterotrimer consisting of the UmuC and two UmuD’ subunits was published (Tang et al., 1998). Although the possibility of contamination of the purified complex by trace amounts of other polymerase had not been entirely ruled out at the time the paper was published, subsequent studies unequivocally proved that the UmuD’2C complex which was subsequently named pol V, is able to copy undamaged and abasic site-containing DNA templates without the assistance of any other polymerase (Reuven et al., 1999; Tang et al., 1999). Practically simultaneously, TLS polymerase activity was reported for E.coli DinB (pol IV) (Wagner et al., 1999).

At the same time, watershed discoveries were also made in the field of eukaryotic polymerases. In 1999 the S.cerevisiae Rad30 protein was identified as a bona fide DNA polymerase, pol η which could bypass thymine-thymine cyclobutane dimers efficiently (Johnson et al., 1999b). Soon thereafter, TLS activity was shown for human DNA polymerases η (Johnson et al., 2000c; Masutani et al., 1999b; Zhang et al., 2000a), ι (Johnson et al., 2000b; Tissier et al., 2000b; Zhang et al., 2000c) and κ (Johnson et al., 2000a; Ohashi et al., 2000b; Zhang et al., 2000b)

Importantly, human pol η was shown to be defective in humans with the variant form of Xeroderma Pigmentosum (XPV) (Johnson et al., 1999a; Masutani et al., 1999b), a cancer-prone syndrome characterized by an increased incidence of skin malignancies and sensitivity to sunlight (Lehmann et al., 1975; Maher et al., 1976). This discovery led to the realization that pol η normally protects humans from the deleterious effects of excessive exposure to sunlight through its extraordinary ability to facilitate TLS past UV-induced CPDs very efficiently and accurately (Masutani et al., 1999a).

By the turn of the twenty first century, scientists were armed with new and powerful tools. Rapid progress in genomic sequencing and advanced search mechanisms opened the door for the identification of a whole class of protein related to the UmuC/DinB/Rad30/Rev1-like proteins, which were subsequently named the “Y-family” of DNA polymerases (Ohmori et al., 2001).

In the space of three years, additional members of the A- and X -families were also identified (Figure 1). Indeed, it was an extremely exciting time for scientists working in the DNA polymerase field. While it took four decades to identify the first six eukaryotic DNA polymerases, the same number of polymerases had been discovered in just two years, 1999–2000. In the field of prokaryotic polymerases, the situation was similar – within one year, the number of known polymerases grew from three to five.

During the early years of DNA polymerase research, new enzymes were often given their consensus names many years after their catalytic activity had been demonstrated. In modern times, naming a new polymerase sometimes preceded their biochemical characterization. Thus, yeast pol ζ was purified 7 years after the prediction that the Rev3 gene encodes a DNA polymerase based on the sequence homology to several known polymerases (Morrison et al., 1989; Nelson et al., 1996b). Such predictions occasionally even caused confusion regarding polymerase nomenclature. For example, a putative DNA polymerase homologous to E. coli DNA pol I was identified in 1996 in the genomes of several eukaryotic organisms through the analysis of sequence databases (Harris et al., 1996; Sonnhammer and Wootton, 1997). This enzyme, originally called pol η (Burtis and Harris, 1997) was later renamed pol θ (Burgers et al., 2001) and its intrinsic polymerase activity was not experimentally verified until 2003 (Seki et al., 2003). Interestingly, the same Greek letter designation (θ) was originally given to the product of the human DINB1 gene (Johnson et al., 2000a), which is now known as pol κ. In its turn, pol κ was originally assigned to the product of the TRF4 (Topoisomerase one-requiring function 4) gene (Wang et al., 2000), and later re-designated as pol σ. This enzyme related to the X-family DNA polymerases has been shown to be involved in sister chromatid cohesion (Wang et al., 2000), although another study suggested that instead of possessing DNA polymerase activity, TRF4 protein might only exhibit poly(A) RNA polymerase activity (Haracska et al., 2005b).

The rapid pace with which DNA polymerases were identified at the turn of the century slowed down after 2000 and only one new eukaryotic polymerase, pol ν was discovered in the next decade (Marini et al., 2003). However, there is a good chance that identification of enzymes belonging to the DNA polymerase superfamily is still incomplete. Thus, interest in this research field was recently refueled by the discovery of a whole new class of DNA polymerases possessing both primase and DNA polymerase activities and accordingly named PrimPol (Bianchi et al., 2013; García-Gómez et al., 2013). These enzymes belong to a large functionally diverse superfamily of ancient enzymes equipped with broad enzymatic capabilities related to DNA metabolism and are present in all domains of life. There is a great deal of evidence suggesting that among a large variety of cellular functions fulfilled by PrimPols a very prominent role is that of TLS past various replicase stalling lesions [recently reviewed in (Guilliam et al., 2015; Helleday, 2013)].

Today, we know that the human genome encodes at least 15 DNA template-dependent DNA polymerases (terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TdT), the unique template-independent DNA polymerase, is not included in this review). Only a handful of these enzymes are responsible for the bulk of nuclear and mitochondrial DNA replication and for the significant part of repair DNA synthesis (pols δ, ε, and γ), while all other polymerases are required for the fine-tuning of multiple diverse DNA transactions in cells. Most of these polymerases have been implicated in TLS one way or another. Why do cells need so many enzymes capable of copying damaged DNA? It has been estimated that between 1017–1019 DNA damaging events occur in a human body every day (Lindahl and Barnes, 2000). Even though the majority of modified bases are removed through multiple elaborate repair mechanisms, many lesions nevertheless persist during S-phase, when DNA is being replicated, and this represents a serious challenge for replication fork progression. In some cases, replicative polymerases can overcome such obstacles themselves, but much more often they are forced to give way to specialized enzymes that are better equipped to extend the replication fork past damaged sites. The large amount of overall damage does not, however, justify the necessity to possess such a wide variety of DNA polymerases until one considers the extraordinary variety of DNA lesions and differences in structural DNA distortions. Accordingly, it makes perfect sense that a wide assortment of polymerases with different affinities for various types of damaged DNA are required to perform highly specialized functions, especially since each enzyme is involved in more than one pathway (Lange et al., 2013; Sale et al., 2012; Sharma et al., 2013), including those which are not directly related to replication of damaged DNA (Pillaire et al., 2015). As previously mentioned, in this this review, we will focus on DNA polymerases whose primary functions are related to replication of damaged DNA.

Major tools in studies of eukaryotic TLS

The first insights into error-prone damage tolerance mechanisms were gained through genetic experiments using bacterial and yeast systems. By analyzing mutant strains, multiple genes involved in damage-induced mutagenesis have been identified. It is through these studies that UmuC and Rev1 were first implicated in DNA synthesis, even though they were originally hypothesized to function simply as “mutagenesis proteins”, or accessory factors of the cells DNA replicase (Bridges and Woodgate, 1985). An understanding of how these proteins and their orthologs in other organisms actually function came from biochemical studies in which DNA replication reactions were reconstituted in vitro. This approach is still widely used to study the biochemical properties of DNA polymerases such as fidelity, processivity, and ability to copy damaged DNA. In vitro studies not only provide a direct proof that the protein in question is indeed a TLS polymerase, but also specify the type of DNA lesion each polymerase is able to tolerate and allows for the identification of protein partners, along with the determination of optimal reaction conditions for most efficient and accurate replicative bypass. Biochemical characterization therefore plays an important role in predicting which polymerase is best suited to bypass a specific lesion, as well as in identifying candidates for a backup role. While these studies provide valuable information, they nevertheless have to be substantiated by in vivo evidence and represent only the first step in elucidating the mechanism of translesion replication.

Mechanistic insights into many aspects of TLS polymerases functions have been gained through structure-function studies. Thus, crystallographic studies provided the molecular basis for understanding the common biochemical properties of TLS polymerases in general and the unique features of each polymerase in particular. Such studies also allows one to analyze the structural determinants underlying the recruitment of TLS polymerases to the replication fork and mechanism by which there is a switch between high-fidelity and specialized DNA polymerases is achieved.

An important assay used to not only confirm the participation of a particular TLS polymerase in the cellular response to a specific type of DNA damage, but also to characterize translesion replication in a living cell, is fluorescent microscopy. This method is based on immunological detection of overexpressed proteins, or of a polymerase fused to a fluorescent protein. It provides direct evidence of the localization of TLS polymerases at replication factories and allows one to monitor their interaction with protein partners.

In recent years, the biological role of TLS polymerases has been extensively investigated using knockout mouse models. While homozygous inactivation of murine Rev3 (catalytic subunit of pol ζ) leads to embryonic lethality, mice defective one or more Y-family DNA polymerase have been generated (Esposito et al., 2000; Jansen et al., 2006; Jansen et al., 2014a; Lin et al., 2006; McDonald et al., 2003; Ohkumo et al., 2006; Schenten et al., 2002) [and reviewed in (Goodman and Woodgate, 2013; Guo et al., 2009; Jansen et al., 2015; Lange et al., 2011; Lehmann et al., 2007; Loeb and Monnat, 2008; Makarova and Burgers, 2015; Pillaire et al., 2014; Sale et al., 2012; Seki et al., 2005)]. These studies, together with analysis of epidemiological data in humans with altered expression of TLS polymerases provide invaluable information about the connection between TLS and human health, especially with regard to cancer risk.

Biochemical properties of TLS polymerases

Extensive investigations during the first decade following the discovery of TLS DNA polymerases mainly focused on their biochemical properties [reviewed in (Boiteux and Jinks-Robertson, 2013; Choi et al., 2010; Goodman and Woodgate, 2013; Guengerich et al., 2015; Guo et al., 2009; Katafuchi and Nohmi, 2010; Lehmann, 2005; Makarova and Burgers, 2015; Maxwell and Suo, 2014; Prakash and Prakash, 2002; Shcherbakova and Fijalkowska, 2006; Vaisman et al., 2002; Vaisman et al., 2004; Vaisman and Woodgate, 2004; Waters et al., 2009; Yang et al., 2013; Yang, 2005; Yang and Woodgate, 2007)]. Here, we will summarize the accumulated data and present them in the context of the in vivo observations emphasizing the biological functions of the enzymes. In general, translesion polymerases are characterized by low catalytic efficiency, fidelity and processivity. This set of properties is not surprising taking into account that the main task of TLS polymerases is to help the main replicase to overcome obstacles and keep replication going. The fact that the active site of TLS polymerases is flexible enough to accommodate damaged nucleotides suggests that it is not stringent enough to maintain a tight interaction with DNA so as to prevent the polymerase from dissociating, to ensure the high efficiency of the correct base incorporation, and to exclude binding of non-complementary bases. In fact, the right balance between these biochemical characteristics is very important in maintaining overall genomic integrity: low catalytic activity and a distributive mode of DNA synthesis prevents highly inaccurate polymerases from replicating long stretches of DNA and generating large number of mutations. In all TLS polymerases, low-fidelity results from not only the intrinsic reduced capacity to discriminate between right and wrong nucleotides, but also by the lack of 3′–5′ exonucleolytic proofreading that allows these enzymes to avoid an additional kinetic barrier to translesion synthesis (Khare and Eckert, 2002). It is important to mention that low fidelity, which at first blush seemed to be an inevitable side effect of the necessity to rescue arrested replication, in many cases is actually beneficial for the living organisms (see below). One example illustrating the usefulness of erroneous DNA synthesis is somatic hypermutation, a mechanism by which the immune system adapts to foreign antigens. In order to accomplish this task, targeted mutations in the variable regions of immunoglobulin genes must be generated. One of the pathways by which mutations can be created involves DNA synthesis by error-prone DNA polymerases. While one way or another, all TLS polymerases have been considered as potential suspects responsible for the mutagenesis of antibody genes, only Rev1 and pol η have been unequivocally proven to play a central role in somatic hypermutation (Jansen et al., 2006; Krijger et al., 2013; Seki et al., 2005; Yavuz et al., 2002; Zhao et al., 2013).

B-family pol ζ

Pol ζ has been extensively studied since its discovery as the first DNA polymerase specializing in TLS. But even today, it does not appear that we have a complete picture reflecting the involvement of the enzyme in various cellular processes. On one hand, characterization of a vertebrate homologue has been hindered by the difficulty of purifying the large multi-subunit complex, while investigation of the biological roles of mammalian pol ζ have been hampered by the embryonic lethality of mice with a disruption of the rev3L gene and inviability of murine rev3L−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts (Mefs). For more than 15 years following the first purification of the overexpressed yeast pol ζ as a heterodimeric complex (Nelson et al., 1996b), pol ζ was believed to consist of a large catalytic Rev3 subunit and much smaller regulatory subunit, Rev7, which stabilizes and increases the activity of the polymerase, as well as mediates the interaction of pol ζ with Rev1 (see below). However, in 2012, several groups independently demonstrated that the Rev3/Rev7 heterodimer is the minimal assembly sufficient for the in vitro activity of pol ζ, but this complex lacks essential components required for proper functioning of the polymerase in vivo. According to the current paradigm, pol ζ, similar to other B-family polymerases, is a tetrameric holoenzyme (ζ4), which shares two essential accessary subunits (POLD2/p50 and POLD3/p66 in humans and Pol31 and Pol32 in S.cerevisiae) with the replicative pol δ (Baranovskiy et al., 2012; Johnson et al., 2012; Makarova et al., 2012).

The catalytic activity of yeast Rev3 on undamaged DNA is stimulated 20–30 fold by the Rev7 subunit and increases another 5–10-fold with the addition of Pol31 and Pol32 subunits (Makarova et al., 2012). Similar results were obtained using damaged templates where primer extensions were 2–5 fold more efficient when pol ζ holoenzyme was used (Johnson et al., 2012). An increase in the efficiency of nucleotide incorporation by the purified human ζ4 compared to ζ2 was even higher (~30-fold) (Lee et al., 2014). The presence of pol δ accessory subunits also enhanced the processivity of both human and yeast pol ζ4 (Lee et al., 2014; Makarova et al., 2012). The increase in the catalytic activity and processivity are likely due to enhanced DNA binding by pol ζ holoenzyme. In contrast, it is not significantly modified by the presence of the accessory proteins RPA (replication protein A), RFC (replication factor C), or PCNA (Zhong et al., 2006).

It has been long known that even though pol ζ belongs to the B-family of DNA polymerases that are composed of accurate replicative polymerases, its 3′-5′ exonuclease domain is inactive and it is responsible for more than half of spontaneous and virtually all DNA damage-induced mutagenesis in yeast. In humans, the low fidelity of pol ζ is manifested by chromosome instability and carcinogenesis caused by alterations in its expression (Diaz et al., 2003; Gan et al., 2008; Lange et al., 2011; Wittschieben et al., 2006). It was originally believed that pol ζ-dependent mutagenesis resulted primarily from the exceptional ability of the enzyme to extend mispairs made by other polymerases. Indeed, steady-state kinetic studies of yeast pol ζ using primed single-stranded oligonucleotide templates revealed about 100-fold higher discrimination against nucleotide misincorporation (103–104 fold) compared to mismatched primer extension (10–100 fold) (Johnson et al., 2000b). However, subsequent studies using undamaged gapped plasmid DNA substrates have shown that yeast pol ζ is also able to directly generate its own mismatches. The mutational spectra determined in these studies correlate well with the in vivo findings. They indicate that pol ζ-dependent errors are confined to specific sequence contexts and are often clustered in short patches, at a rate that is unprecedented in comparison with other polymerases. The average base substitution fidelity of yeast pol ζ in gap-filling reactions was significantly lower than that of related pols α, δ and ε (Zhong et al., 2006). Thus, pol ζ2 was roughly 100-times more error-prone than pols δ and ε with intact 3′ – 5′ proofreading capacities and ~10-times more inaccurate than naturally proofreading-deficient pols α and exo-deficient δ and ε (Zhong et al., 2006). However, the overall error rate of pol ζ was still lower than that of Y-family polymerases. Thus in a gap-filling assay, yeast pol ζ made 1 mistake per 770 nucleotides copied, which makes it almost 5-times more accurate than the most faithful Y-family human pol κ (Zhong et al., 2006). Despite the fact that the base substitution fidelity of pol ζ is substantially lower than that of replicative polymerases, discrimination against incorporation of nucleotides with the wrong sugar by yeast pol ζ is only slightly lower than the sugar selectivity of high fidelity enzymes (Makarova et al., 2014).

In vitro studies using damaged DNA templates suggested that among the large variety of DNA lesions that pol ζ is able to bypass, some are replicated accurately (Johnson et al., 2003; Lin et al., 2014b), while TLS past others is highly error-prone (Lin et al., 2014a). In agreement with in vitro data, genetic studies have demonstrated that yeast pol ζ is not only necessary for damage-induced nuclear and mitochondrial genome mutagenesis, it also promotes accurate bypass of some DNA lesions (Baruffini et al., 2012; Baynton et al., 1999; Bresson and Fuchs, 2002; Kalifa and Sia, 2007; Zhang et al., 2006). On all damaged templates tested, pol ζ was a great deal less efficient at incorporating a nucleotide opposite the damaged bases than extending the resulting primer terminus, consistent with the idea that its primary role in lesion bypass is confined to the elongation step, while the incorporation step depends on other polymerases. However, pol ζ has the capacity to catalyze all steps of TLS by itself acting as both the inserter and an extender (Stone et al., 2011). It should be noted that studies related to the fidelity and TLS activity of yeast and human pol ζ4 are very limiting at the present time, but the available data do suggest that in the presence of all accessory subunits, pol ζ4 catalyzes TLS much more efficiently compared to the pol ζ2 complex (Lee et al., 2014; Makarova et al., 2012).

Y-family pols η, ι, κ and Rev1

In contrast to pol ζ, all eukaryotic Y-family polymerases are currently believed to be encoded by a single polypeptide enzyme consisting of a conserved N-terminal domain of 350–450 amino acids containing the catalytic active site, and a variable-length C-terminal region important for regulatory protein–protein interactions (Figure 2B). Despite being characterized by generally common features, each member of the Y-family of DNA polymerases has a unique personality. For example, pol η is exceptionally efficient and accurate while incorporating nucleotides opposite the CPDs; pol κ specializes in the extension step of lesion bypass; Rev1 abstains from incorporating nucleotides other than dCTP and functions in mitochondria, while pol ι in some cases favors the formation of non-Watson-Crick base pairs and, like X-family pols β and λ, has a dRP lyase activity important for Base Excision Repair (BER) and prefers to use Mn2+ as an activator for catalysis. The characteristics of each polymerase have been extensively studied using an in vitro approach. Although these studies have sometimes produced conflicting results and still require in vivo verification, they provide an important clue to understanding how these polymerases function in a living cell.

Figure 2. Structural organization of catalytic domains of TLS polymerases.

A. Comparison of yeast (S. cerevisiae) and human (H. sapiens) REV1 and REV3 gene structures. The domain arrangement in yeast and human Rev proteins are very similar (the percent identity for the related regions are indicated within the gray areas between the human and yeast proteins). The human enzymes are larger than the yeast enzymes due to long inserts in the respective genes (one in Rev3 and two in Rev1 [I1 and I2], see the text for details). The conserved sequence motifs in Rev3 characteristic for the B-family DNA polymerases are indicated by roman numerals (I-VI). B. Arrangement of the functional domains in human Y-family polymerases. All polymerases (panels A & B) are aligned relative to the N-terminus of the catalytic core and all diagrams are drawn to the scale. The name of each polymerase and its length (number of amino acids) are indicated on the right-hand side of the figure and the gene designation is indicated on the left side of each protein. The catalytic domains of the polymerases are color-coded as follows: red – palm; green – thumb; light blue – fingers; purple – little finger; aquamarine –catalytic core of pol ζ with polymerase (light pink) and inactive 3′-5′ exonuclease (dark pink) domains. C. Interaction map of the proteins important for TLS. In all panels (A-C) the domains involved in protein-protein interactions are color-coded: NTD – N-terminal domain; MLS – mitochondrial localization signal; BRCT – breast cancer-associated protein-1 carboxyl-terminal domain; N-Clasp – structural feature of pol κ; NLS – nuclear localization signal in pols ζ, η, ι, and κ (pol ι contains non-classical NLS motif; in pol ζ the signal is shown for the yeast protein, but is not shown for the human enzyme since it is located within the omitted ~1550 amino acid region); UBM – ubiquitin binding motif; UBZ – ubiquitin binding zinc-finger motif; CTD – C-terminal domain of Rev3 which in addition to the N-terminal zinc finger [ZF] motif contains C-terminal iron–sulfur [FS] cluster, a binding site for other polymerase subunits; dRP – dRP lyase domain (the ~40 kDa region in pol ι to which the dRP lyase activity has been mapped (Prasad et al., 2003) is indicated below the schematic representation of the primary protein structure); PIP – PCNA-interacting protein motif; RIR – Rev1-interacting region motif; PIR–protein interaction regions (two PIR sites [PIR1 & 2]) in human Rev3 and yeast Rev1, as well as one PIR site in yeast Rev3 and human Rev1 are involved in the interaction with Rev7; in addition the PIR site in the CTD of human Rev1 is required for the binding to pols η, κ, and ι, while in yeast the PIR site in the catalytic domain of Rev1 [PIR1] is involved in the interaction with pol η, Rev3 and Rev7. The PIR in the CTD of human Rev1 [PIR2] has two interfaces: the C-terminal part (C) is required for the interaction with Rev7, while the N-terminal part (N) is involved in an interaction with PolD3 and pols η, ι and κ. The PIP and RIR motifs have similar consensus sequences, but have traditionally been viewed as separate entities. In several recent studies, it has been proposed that these motifs be considered as parts of a single “PIP-like” motif capable of binding multiple target proteins (Boehm and Washington, 2016). The position of the star (*) above the pol η sequence corresponds to the F1 motif necessary for the interaction with the POLD2 subunit of pol δ (Baldeck et al., 2015).

Pols η and κ, similar to the high-fidelity replicative polymerases, form all four possible correct base pairs with comparable catalytic efficiencies, while the catalytic activity of pol ι and Rev1 are highly template base dependent: Rev1 specializes in the incorporation of dCTP opposite template G, whereas pol ι is most efficient while incorporating T opposite template A. In vitro replication reactions have clearly established that Y-family polymerases are significantly less processive than the high fidelity replicative polymerases. However, the absolute number of nucleotides incorporated per DNA binding event varies among individual members, from very low, such as 2–3 nucleotides per DNA binding event in the case of pol ι in the presence of physiological activator Mg+2 and Rev1 on a poly(dG) template, to moderate, ~ 20–30 nucleotides for pol κ. Y family polymerases are also characterized by significantly different abilities to discriminate against incorrect nucleotide substrates which include those that do not comply with Watson-Crick base complementarity, as well as those that have the wrong sugar moiety. Ribonucleotide incorporation by DNA polymerases has only recently attracted long overdue attention and very little information about the discrimination between dNTPs and rNTPs by the eukaryotic members of Y-family is currently available. But even the limited data that is available suggest that these enzymes tolerate nucleotides with an incorrect sugar differently. Thus, on undamaged templates, human pol κ hesitates to incorporate ribonucleotides at any detectible levels, while Rev1 discriminates between deoxy- and ribo-cytosine with moderate efficiency, incorporating rCTP 280 times less frequently than dCTP (Brown et al., 2010). The sugar selectivity of pol η and pol ι during TLS indicates that ribonucleotide incorporation is only observed only for pol ι (Donigan et al., 2014; Donigan et al., 2015). However, even then, the efficiency of pol ι-catalyzed rNTP insertion was more than 1000 times lower compared to incorporation of dNTPs and extension of ribonucleotide-terminated primers was efficient only in the presence of dNTPs.

In contrast to sugar selectivity, the base substitution fidelity of Y-family polymerases has been investigated extensively. These studies revealed that in the presence of Mg+2, base substitution error rates range from 6×10−3 for the most faithful pol κ, to 3.5×10−2 for pol η, and 3 ×100 for pol ι (Matsuda et al., 2001; Ohashi et al., 2000a; Tissier et al., 2000b; Vaisman et al., 2004). Furthermore, the nucleotide misincorporation specificity and the mode of introducing mutations are different for each polymerase. Thus, while pol η and pol ι readily misincorporate nucleotides, pol κ is most efficient in the extension of mismatched, or misaligned, primer termini and readily generates frameshift errors especially single-nucleotide deletions. Pol ι is exceptional in its nucleotide misincorporation specificity: it is most accurate opposite template A (with a misincorporation frequency of 1–2 × 10−4) and most unfaithful opposite template T/U, where it favors misincorporation of dG over the correct dA (by 3 to 10-fold), and it also misinserts dT opposite template T almost as frequently as the correct base, dA. Such unusual substrate specificity might play an incredibly important role in maintaining genome integrity by restoring the coding properties of cytosines that have undergone spontaneous or damage-induced deamination. Cytosine deamination occurs at a significant rate in cells, making pol ι uniquely equipped to single-handedly combat CG to TA transition mutations that would be generated if the modified base was copied accurately (Vaisman and Woodgate, 2001; Vaisman et al., 2006). Consistent with this idea are studies with mice lacking functional pol ι that indicate that despite its extreme replication infidelity, pol ι contributes to maintaining genomic stability and preventing mutagenesis and tumorigenesis (Iguchi et al., 2014; McDonald et al., 2003). However, on the “flip side of the coin”, the exceptional ability of pol ι to insert the “correct” dG opposite deaminated cytosines could hinder somatic hypermutation in immunoglobulin genes. By preventing generation of CG to TA transitions, pol ι would interfere with an adequate immune response to infection where enhanced mutagenesis induced by the targeted deamination of Cs and accurate copying of the resulting Us plays a pivotal role. This potentially helps explain why cells generally avoid recruiting highly error-prone pol ι for somatic hypermutation despite its potential usefulness for the alternative mechanisms of generating mutations (McDonald et al., 2003). As with all DNA polymerases, replacing Mg2+ with Mn2+ results in a general reduction of pol ι’s fidelity at template A, but interestingly, the preference for the formation of a wobble base pair between the incoming dG and template T disappears (Frank and Woodgate, 2007). The latter phenomena could be considered as a peculiar increase in fidelity or, alternatively, as a typical Mn2+−dependent decrease in fidelity, if incorporation opposite template T by pol ι represents a case of mistaken identity.

The Y-family polymerases also exhibit a remarkable diversity in their substrate specificity, efficiency and fidelity during replication of damaged DNA. A great body of literature with detailed characterization of the in vitro replication of DNA containing various lesions by different TLS polymerases has accumulated in recent years. We do not have the intention to list all these studies, but rather will devote our discussion to several which emphasize the notion that Y-family polymerases are specialized for the roles they play in lesion bypass. For example, pol η is best characterized for very efficient and quite accurate bypass of UV-induced CPDs, but also platinum interstrand crosslinks formed at adjacent guanines by anticancer drugs (Masutani et al., 1999a; Masutani et al., 2000; McCulloch et al., 2004; Vaisman et al., 2000; Washington et al., 2000). These properties on one hand put pol η in a unique position as a protector of mammals from UV-induced carcinogenesis that is manifested by the XPV syndrome in humans lacking POLH gene (Masutani et al., 1999b), but on the other hand, they paint pol η as a facilitator of tumor progression that reduces the efficacy of Platinum-based chemotherapy. While pol κ is unable to incorporate nucleotides opposite the 3′T of a CPD, pol ι replicates the CPD-containing DNA templates with moderate efficiency. Pol ι’s ability to bypass CPDs is dependent on the surrounding sequence context and even more on the identity of the divalent metal ions coordinated within the active site of the polymerase (Frank and Woodgate, 2007; Tissier et al., 2000a; Vaisman et al., 2003). Thus, although pol ι -catalyzed bypass of CPDs is still substantially less efficient than that of pol η, it is stimulated dramatically by Mn2+ and can reach up to 60% bypass, which is more than that observed for any other human polymerase (except pol η). In fact, the reduced efficiency in the presence of Mg2+ could be important in suppressing the translesion capacity of pol ι in normal cells. In the absence of pol η, pol ι can be activated by Mn2+ which although present at much lower concentration than Mg2+, can accumulate intracellularly through specific import pathways (Madejczyk and Ballatori, 2012; Bouron et al., 2015). The ability of pol ι to replicate past CPDs makes it a likely candidate to collaborate with other TLS polymerases in substituting for pol η in XPV cells (Frank and Woodgate, 2007; Tissier et al., 2000a; Vaisman et al., 2003; Vaisman et al., 2006). Several subsequent in vivo studies provided multiple lines of evidence supporting this hypothesis (Gueranger et al., 2008; Jansen et al., 2014a; Livneh et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2007; Ziv et al., 2009).

Both pol η and pol ι but not pol κ, are able to incorporate nucleotides opposite the 3′ base of a thymine-thymine 6–4 photoproduct (Yamamoto et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2000a; Zhang et al., 2000b). On the other hand, whereas human pol η and pol ι bypass benzo[a]pyrene diol epoxide deoxyguanosines adducts (a naturally occurring metabolite of carcinogens commonly found in cigarette smoke) inefficiently and inaccurately (Chiapperino et al., 2002; Frank et al., 2002; Rechkoblit et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2002a), pol κ bypasses the lesion with high efficiency and predominantly incorporates the correct base, dC, opposite the adducted G (Rechkoblit et al., 2002; Suzuki et al., 2002; Zhang et al., 2000b) (Zhang et al., 2002a) (Huang et al., 2003) (Zhang et al., 2002b). In fact, it has been proposed that pol κ may have evolved specifically to catalyze accurate bypass of various related lesions generated by polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, abundant and ubiquitous environmental pollutants, and studies with transgenic mice devoid of pol κ support such hypotheses (Ogi et al., 2002). All four Y family polymerases can incorporate nucleotides opposite an abasic site although with different efficiencies and base and sugar specificities and therefore could be involved in translesion replication past this common non-instructional lesion.

Finally, recent studies suggest that Y-family polymerases participate in metabolic pathways unrelated to TLS. For example, pol η appears to be involved in somatic hypermutation of immunoglobulin genes (Delbos et al., 2005; Martomo et al., 2005; Pavlov et al., 2002; Rogozin et al., 2001; Seki et al., 2005; Wilson et al., 2005), replication of common fragile sites (Bergoglio et al., 2013; Despras et al., 2016; Rey et al., 2009), telomeres (Betous et al., 2009; Pope-Varsalona et al., 2014) and homologous recombination repair (Kawamoto et al., 2005; McIlwraith et al., 2005; Nicolay et al., 2012a); pol κ has been implicated in nucleotide excision repair (Ogi and Lehmann, 2006); and pol ι may play a role in specialized forms of BER (Bebenek et al., 2001).

Structural features of TLS polymerases

Despite the lack of primary amino acid sequence homology between DNA polymerases from different families, they all share a common structural topology of a catalytic core often described as a right hand with finger, palm, and thumb subdomains holding DNA and positioning the incoming dNTP for incorporation (Figure 2). The active center of the polymerases resides in the palm domain where the essential metal ions required for the nucleotidyl transferase reaction are coordinated. The thumb subdomain plays an important role in binding to DNA and determining the enzyme’s processivity and translocation. The fingers domain is largely responsible for the positioning of DNA template required for optimal nucleotide pairing. Besides the conserved polymerase domains, DNA polymerases in general often have additional domains that have evolved to fulfill specific functions. Thus, most replicative polymerases contain a 3′ – 5′ exonuclease domain that proofreads newly synthesized DNA and corrects mismatched base pairs. In contrast, the majority of specialized polymerases lack a 3′ – 5′ exonuclease domain. The exception is pol ζ, the catalytic core of which is homologous to the B-family replicative polymerases, and thus contains sequences corresponding to the 3′–5′ exonuclease domain, even though it is non-functional (Figure 2A). All Rev proteins (Rev1, Rev3, and Rev7) have a mitochondrial localization domain located at their N-terminus (Figure 2A), which allows them to assist pol γ in the replication of a damaged mitochondrial genome (Zhang et al., 2006). The domain that separates Y-family enzymes from other polymerases is located in the C-terminus and is connected to the catalytic core by a flexible linker. This domain mediates the contact of the polymerase with DNA and has been referred to as the “little finger” (LF) (Ling et al., 2001), “wrist” (Silvian et al., 2001), or “polymerase-associated domain” (PAD) (Trincao et al., 2001) (Figure 2B). We think that the “LF” acronym is more appropriate, because it keeps in line with the general structural topology of a hand and we will use this term throughout the review. While the palm, thumb and finger domains of the Y-family polymerases are highly conserved, the LF domain is unique for each family member and plays an important role in determining the biochemical properties and biological function of each individual enzyme (Boudsocq et al., 2004; Wilson et al., 2013).

Primary structure and domain organization of pol ζ

Pol ζ is the only error-prone TLS polymerase which shares structural complexity and sequence homology with high-fidelity B-family replicative polymerases. Like other B-family polymerases, pol ζ is a multi-subunit complex. The catalytic domain of pol ζ (Rev3) is homologous to that of other family members (pols α, ε, and δ) in both amino-terminal and carboxyl-terminal regions. A cysteine-rich C-terminal domain (CTD) of Rev3 contains two conserved metal binding sites– a zinc finger [ZF] motif towards the N-terminal side of the CTD and an iron–sulfur [4Fe-4S] cluster in the C-terminal portion of the CTD (Figure 2A). The ZF motif has been proposed to mediate the DNA-dependent interactions of pol ζ with PCNA similar to that shown for pol δ (Netz et al., 2012). The [4Fe-4S] cluster serves as a docking site for additional polymerase subunits, such as POLD2 in mammalian cells and Pol31 in yeast, which pol ζ shares with pols δ (Baranovskiy et al., 2012; Netz et al., 2012). Rev3 differs from other B-family polymerases by the presence of a large insert containing short motifs required for binding to Rev7, a regulatory subunit specific for pol ζ (Figure 2). The size of the insert in Rev3 varies between species. For example, the human Rev3L protein is about twice the size of its S.cerevisiae counterpart (Figure 2). The amino acid sequence of the inserts in the human and S.cerevisiae Rev3 proteins show little similarity, except for the 55-residue region containing the Rev7 binding site (gray area between yeast and human enzymes on the Figure 2). The internal sequence of REV3L contains a second site required for the interaction with Rev7 and is located ~100 amino acids away from the first Rev7 binding site (Tomida et al., 2015). This site is conserved in vertebrates, but it has not been found in Rev3 homologs from fungi (Figure 2).

A 3D structural model of the four-subunit yeast pol ζ generated using electron microscopy suggests an overall elongated structure with separate catalytic and regulatory lobes that resembles the bilobal architecture of replicative polymerases (Gómez-Llorente et al., 2013). Based on sequence conservation, pol ζ is predicted to have the same overall topology and mechanism of nucleotide incorporation as replicative polymerases.

Structural insight into Y-family polymerases functions

Common structural features

In contrast to pol ζ, various structural studies involving the eukaryotic Y-family enzymes have been determined that have helped us to understand their unique biochemical activities. As expected, these studies revealed the general structural organization separating this group from polymerases belonging to other families, i.e. an unusually flexible and solvent accessible active site pocket that is able to tolerate a variety of damaged template bases. The finger and thumb domains which play an important role in choosing and positioning of the correctly paired nucleotide in the active site of the replicative polymerases are generally shorter and make fewer contacts with a DNA substrate and an incoming nucleotide and the unique LF domain helps to constrain the target nucleotide of the DNA backbone within the polymerase active site.

One might predict that the relaxed constraints of the active sites of Y-family polymerases should not only reduce their base-substitution fidelity, but also make them less discriminatory with regard to sugar selection. However, quite unexpectedly, no such correlation has been found. Instead, discrimination factors vary greatly and are not directly related to the base-fidelity of the polymerase [reviewed in (Vaisman and Woodgate, 2014)]. This apparent discrepancy is explained by the fact that most DNA polymerases, including those from the Y-family, utilize the same major mechanism of sugar discrimination. In order to prevent incorporation of nucleotides with the wrong sugar, DNA polymerases rely on a specific amino acid within the nucleotide-binding pocket in the polymerase active site. This highly conserved residue (in the Y-family it is Phe or Tyr) serves as a “steric gate” clashing with the 2′-OH of the incoming rNTP. Therefore, it is this region of the polymerase cleft, rather than general active site architecture, which controls sugar selection of a particular polymerase.

Conformational changes during catalytic cycle

While the general structural features of the active site of high fidelity DNA polymerases can be characterized (as above), it is not static, but rather goes through conformational changes during substrate binding and catalysis. Upon correct nucleotide binding, these polymerases undergo “an induced fit” structural change from the open conformation of the binary complex (polymerase-DNA template), to the closed conformation of the catalysis-ready ternary complex (polymerase-DNA template-dNTP), due to the large finger subdomain motions (Freudenthal et al., 2013; Johnson, 2008; Moscato et al., 2016). Subsequently, the correct nucleotide incorporation occurs from a closed conformation that ensures the tight fit of the nascent base pair within the binding pocket. This conserved mechanism safeguards the high-fidelity of replicative polymerases, but is not shared by the error-prone Y-family polymerases, because their spacious and solvent-accessible active sites are preformed with the fingers already in a closed position, even in the absence of DNA or dNTP. However, a significant conformational change does take place at least in some Y-family members, although it occurs during the transition from the apo state to DNA-bound binary state, by a rotation of the little finger domain relative to the polymerase catalytic core. In eukaryotes such movement has been shown for pol κ (Lone et al., 2007; Uljon et al., 2004). Although crystallographic studies did not detect a large finger subdomain motion upon the nucleotide substrate binding, several fluorescence studies have provided some insight into the conformational dynamics in the archaeal enzymes [reviewed in (Maxwell and Suo, 2014)]. These studies indicated conformational rearrangements in the active sites of Y-family polymerases taking place during nucleotide incorporation and provided the first evidence that TLS polymerases may adjust their conformational changes, so as to accommodate the proper positioning of lesion-containing DNA substrates.

Unique characteristics

All TLS polymerases are characterized by a similar general structural organization, they share multiple primary sequence motifs, and have the same ultimate goal – to ensure that replication of DNA is completed without leaving behind any unfilled gaps or discontinuances. However, even within one family, each individual member chooses its own strategy to tackle this task and each TLS polymerase is characterized by its own distinctive features, which define its specific catalytic activities.

DNA Polymerase η

The signature feature of the active site of pol η is its particularly large size, allowing it to accommodate the linked thymine bases of a cyclobutane pyrimidine dimer and to stabilize them for the correct pairing with an incoming dA (Biertümpfel et al., 2010; Yang, 2014). The fascinating feature of pol η is that it is not only able to efficiently and accurately interpret information encoded by the damaged Ts, but also ensures that the reading frame is properly maintained. This is possible because unlike pol κ, there is no gap between the catalytic core and the LF domain. As a result, extensive interactions between these domains stabilize the entire polymerase region and act as a “molecular splint” to keep the newly synthesized duplex in a stable B-form (Biertümpfel et al., 2010). Furthermore, Pol η processively inserts three more bases past the lesion, at which point it switches back to a distributive mode of DNA synthesis. Further extension is prevented by steric clashes displacing DNA from the enzyme and thus ensuring re-engagement of a high fidelity DNA polymerase. Interestingly, for the accurate bypass of CPDs pol η relies on two uniquely conserved residues (Arg61 and Gln38 in humans) located near the active site and synergistically contributing to the efficiency and fidelity of the enzyme (Biertümpfel et al., 2010; Su et al., 2015). However, these two residues also play a key role in the efficient misincorporation of dG opposite template T, especially when the template T is immediately preceded by an AT primer/template base pair, known as the WA motif (Zhao et al., 2013). Indeed, such a misincorporation pattern on undamaged DNA correlates with the well-known mutation signature of pol η generated during somatic hypermutation of immunoglobulin genes.

DNA Polymerase ι

The catalytic core of pol ι has two partially overlapping catalytic domains; one responsible for DNA polymerase activity and one that harbors dRP lyase activity (Figure 2B). Significant insight into the unusual base selectivity of pol ι that is characterized by a 105-fold difference in fidelity depending upon the template base has been gained from the crystal structure of its ternary complex with DNA substrates and an incoming nucleotide (Nair et al., 2004; Nair et al., 2006a; Nair et al., 2006b). Several large aliphatic residues in the active cleft of pol ι prevent the DNA template and dNTP from binding in its normal position and from forming a canonical Watson–Crick base pair. Instead, the unusually perturbed active site holds the template A fixed in the syn conformation limiting hydrogen-bonding opportunities with any incoming nucleotide other than dT in an anti conformation and thus promoting Hoogsteen base pairing that results in the accurate replication of template A (Nair et al., 2004). However, the same active site configuration is also responsible for the extreme infidelity of pol ι. The unique base selectivity opposite template T is explained by the fact that it is always held by pol ι in an anti conformation, irrespective of the identity of the incoming dNTP. Since an incoming dA adopts a syn conformation and exhibits reduced base stacking, pol ι gives preference to dG remaining in an anti conformation that is stabilized via hydrogen bonding with glutamine (Q59) in the finger subdomain (Nair et al., 2006a). At the same time, the enzyme’s narrow groove width imposition on the nascent base pair makes pol ι more accurate than most polymerases while copying DNA containing the oxidative lesion, 8-oxoG (Kirouac and Ling, 2011). In this case, pol ι firmly holds the damaged base in the syn conformation that would normally cause pairing with the incorrect dA. However, the restrictive active site prevents this from occurring and instead promotes stable pairing with the smaller and correct dC (Kirouac and Ling, 2011).

DNA Polymerase κ

Pol κ differs from other family members by an N-terminal extension (N-clasp) involved in DNA binding (Fig. 2B). A large structural gap divides the catalytic core and the LF in pol κ because of limited interactions between the domains, even in ternary complexes with DNA and dNTPs. The N-clasp stabilizes the polymerase by holding the catalytic core and LF together to encircle DNA (Lone et al., 2007; Uljon et al., 2004; Yang, 2014). It has been hypothesized that these features of pol κ make it specifically adept for the extension of a diverse range of primer termini distorted by base mismatches, or lesions in the template, even though in vivo findings suggest that the main “extender” in cells is pol ζ. Structural studies also suggested that pol κ has a more restrictive active-site cleft compared to other Y-family polymerases and is only able to accommodate only a single Watson–Crick base pair (Lone et al., 2007). Such a configuration explains the relatively higher fidelity of pol κ on undamaged DNA, its limited selection of lesions it can tolerate, and inability to bypass dinucleotide lesions (Bavoux et al., 2005). On the other hand, the structural gap between the catalytic core and LF appears to allow pol κ to accommodate bulky polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons during lesion bypass (Liu et al., 2014).

Rev 1

The unique features of Rev1 include an extended N-terminal region containing BRCT (breast cancer-associated protein-1 carboxy-terminal) and MTS (mitochondrial targeting signal) domains and a C-terminal protein-binding domain. Similar to pol κ, the three-dimensional structure of Rev1 has a large gap that divides the LF domain and the ring-shaped catalytic core encircling DNA (Yang, 2014). This gap is filled by the N-terminal extension from the catalytic core (Nair et al., 2005; Swan et al., 2009). Two large inserts in the finger and palm domains specific for the catalytic core of human Rev1 (Figure 2, I1 and I2) have been suggested to play an important role in supporting the peculiar properties and unique functions of the protein in TLS (Swan et al., 2009). One insert (I1), has been proposed to serve as an additional platform for the protein-protein interactions needed for a specific non-catalytic role of human Rev1 in TLS, while the second insert (I2), is apparently important for the extremely limiting selectivity of Rev1 in the choice of nucleotide and template substrates in human cells.

Unlike other polymerases that depend on DNA to identify the nucleotide best suited for incorporation, Rev1 itself dictates the identity of both the templating base it uses as a substrate (mostly dG and a limited number of N2-adducted dG) and the incoming nucleotide insertion of dC. In order to do so, Rev 1 utilizes an unusual strategy. Instead of the direct pairing of the DNA template with the incoming dC, it swings the template base (dG) out of the helix replacing it with an arginine residue (R324), which forms a hydrogen bond with the incoming dC. The displaced template dG is temporarily accommodated within the hydrophobic pocket in the little finger domain (Nair et al., 2005; Nair et al., 2008), which in the human enzyme is supported by the large insert (Fig 2A, I2) in the fingers domain (Swan et al., 2009).

TLS protein interaction network

Although the overall TLS pathway appears to be conserved throughout evolution (Woodgate, 1999), there is some level of variability in its components between species. This includes the distribution of DNA polymerases themselves. Pol η and Rev1 have been found in all eukaryotic organisms checked thus far, while pols ι and κ have not been detected in some species (Ohmori et al., 2001). It is likely that this variability reflects environmental specificity and variations in DNA damage to which the different organisms are exposed.

Soon after the general mechanism of TLS had been uncovered, the focus in the field began shifting from the biochemical characterization of polymerases in vitro towards finding and characterization of their protein partners in vivo. While substantial progress has been made in this field, there are still a lot of “gray areas” and the proposed mechanisms governing protein interactions are being constantly reexamined. What is evident is that the access of error-prone TLS polymerases to a replication fork is strictly regulated through multiple levels of an elaborate protein interaction network.

Dynamic network of protein-protein interactions involving Rev1 and Rev7

The hREV7 protein is an integral subunit of pol ζ and its interaction with REV1 plays an important role in the recruitment of pol ζ for the bypass of many DNA lesions. Multiple studies have demonstrated that Rev7 not only interacts with Rev3 and REV1 (Murakumo et al., 2001), but also with various proteins that function in different pol ζ-dependent pathways unrelated to TLS (Iwai et al., 2007; Nelson et al., 1999; Weterman et al., 2001; Zhang et al., 2007). While Rev7 has its own protein interaction network independent of TLS, the ability of Rev1 to interact with various proteins is instrumental to TLS regulation. In fact, Rev1 works as a binding platform targeting different TLS polymerases to the stalled replication fork and coordinating their rearrangement in order to ensure the best possible outcome (Boehm et al., 2016; Guo et al., 2003; Ohashi et al., 2004; Waters et al., 2009).

Several studies indicated that Rev1 and Rev7 utilize two modes of protein binding, where one is driven by the recognition of a short motif sequence, while the other involves recognition of the protein tertiary structure. For example, it has been reported that the large region of hREV7 (~130 amino acids) is required for the interaction with the C-terminal domain of hREV1 (Murakumo et al., 2001) and an approximately 100 amino acid region in C-terminal domain of human REV1 (Figure 2A, Protein Interaction Region, PIR) is required for the interaction with all other polymerases from the Y-family, as well as with Rev7 and PolD3 subunits of pol ζ (Figure 2C) (Guo et al., 2003; Masuda et al., 2003; Murakumo et al., 2001; Ohashi et al., 2004; Pustovalova et al., 2016). On the other hand, sequences as short as 16 amino acids in pols η, ι and κ (Figure 2B, one Rev1-interacting region (RIR) in pols ι and κ and two such motifs in pol η) are sufficient for recognition by hRev1 (Figure 2C) (Ohashi et al., 2009). Similarly, two short 9 amino acid-motifs mapped to a region in the N-terminus of human Rev3 (Figure 2A, PIR 1 & 2 also called MCS, Minimum Core Sequence) must be intact to ensure binding to hRev7 (Hanafusa et al., 2010; Tomida et al., 2015). It has been proposed that presence of two binding sites in Rev3 can stabilize a homodimer of REV7 thereby expanding the opportunities for simultaneous interactions with its other protein partners and facilitating multi-protein complex formation, at least in vertebrates.