Abstract

Background

Assessing future risk of exacerbations is an important component of asthma management. Existing studies have investigated short‐ but not long‐term risk. Problematic asthma patients with unfavorable long‐term disease trajectory and persistently frequent severe exacerbations need to be identified early to guide treatment.

Aim

To identify distinct trajectories of severe exacerbation rates among “problematic asthma” patients and develop a risk score to predict the most unfavorable trajectory.

Methods

Severe exacerbation rates over five years for 177 “problematic asthma” patients presenting to a specialist asthma clinic were tracked. Distinct trajectories of severe exacerbation rates were identified using group‐based trajectory modeling. Baseline predictors of trajectory were identified and used to develop a clinical risk score for predicting the most unfavorable trajectory.

Results

Three distinct trajectories were found: 58.5% had rare intermittent severe exacerbations (“infrequent”), 32.0% had frequent severe exacerbations at baseline but improved subsequently (“nonpersistently frequent”), and 9.5% exhibited persistently frequent severe exacerbations, with the highest incidence of near‐fatal asthma (“persistently frequent”). A clinical risk score composed of ≥2 severe exacerbations in the past year (+2 points), history of near‐fatal asthma (+1 point), body mass index ≥25kg/m2 (+1 point), obstructive sleep apnea (+1 point), gastroesophageal reflux (+1 point), and depression (+1 point) was predictive of the “persistently frequent” trajectory (area under the receiver operating characteristic curve: 0.84, sensitivity 72.2%, specificity 81.1% using cutoff ≥3 points). The trajectories and clinical risk score had excellent performance in an independent validation cohort.

Conclusions

Patients with problematic asthma follow distinct illness trajectories over a period of five years. We have derived and validated a clinical risk score that accurately identifies patients who will have persistently frequent severe exacerbations in the future.

Keywords: asthma, asthma exacerbations, frequent exacerbations, recurrent exacerbations, exacerbation risk

Short abstract

Abbreviations

- ANOVA

analysis of variance

- ATS/ERS

American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society

- AUC

area under the receiver operating characteristics curve

- BIC

Bayesian information criterion

- BMI

body mass index

- CI

confidence interval

- ED

emergency department

- FEV1

forced expiratory volume in one‐second

- FVC

forced vital capacity

- GINA

Global Initiative for Asthma treatment

- ICS+LABA

inhaled corticosteroids in combination with long‐acting beta‐2 agonists

- NFA

near‐fatal asthma

- OSA

obstructive sleep apnea

1. Introduction

Exacerbations are a major source of morbidity and economic burden in asthma1 and can lead to poorer quality of life,2 accelerated lung function decline,2, 3 and premature mortality.4 According to the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA),5 assessment of future risk of exacerbations is an important component of overall asthma management.

Existing clinical risk scores have been developed to predict short‐term (6‐12 months) exacerbation risk,6, 7 but given that asthma is a disease that can vary over time, these risk assessment scores may not be adequate for predicting long‐term exacerbation risk. Knowledge of the long‐term clinical trajectories of asthma, that is, patterns of occurrences of exacerbations over several years' duration, allows physicians to predict the future course of disease, stratify risk, and tailor treatment accordingly.

The aims of this study were to identify distinct clinical trajectories of severe exacerbation rates over five years among patients with problematic asthma, to identify baseline factors associated with different trajectories, and to develop and validate a clinical risk score to predict whether a patient will follow an unfavorable trajectory.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

This was a prospective, longitudinal, observational study conducted at the specialist asthma clinic at Singapore General Hospital, which receives referrals from primary care, inpatient discharges, and other respiratory physicians for difficult or severe asthma. We screened and recruited patients presenting in 2011 (derivation cohort) or 2012/2013 (validation cohort). All patients who were on step 4 of the GINA treatment ladder were identified and further screened to select subjects who fulfilled criteria for both “problematic asthma” and “uncontrolled asthma”. “Problematic asthma” was defined according to the Innovative Medicines Initiative8 which encompasses both difficult and severe asthma, the former referring to asthma that is uncontrolled despite high‐intensity treatment due to poor compliance, psychosocial factors, environmental exposures, or comorbidities and the latter referring to patients with truly refractory disease requiring high‐intensity treatment after exclusion of factors that may aggravate or complicate asthma. High‐intensity treatment was defined as GINA treatment ladder ≥ step 4 (medium‐ or high‐dose combination inhaled corticosteroids/long‐acting beta agonists, ICS+LABA).5 “Uncontrolled disease” was defined according to American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society (ATS/ERS) criteria9: Asthma Control Test (ACT) score<20, ≥1 emergency department (ED) visit or hospitalization in the past year, ≥2 steroid bursts in the past year, or airflow limitation (prebronchodilator forced expiratory volume in one‐second, FEV1<80% predicted). Patients were managed according to GINA guidelines and assessed using a standardized protocol which included the following: criteria for asthma diagnosis, precipitants, comorbidities, smoking, treatment history, assessment of compliance by clinical interview, chest radiograph, inhaler technique assessment, IgE, peak flow, skin prick tests, physical examination and measurements, and ACT.

This study was approved by the Singhealth Centralised Institutional Review Board with waiver of informed consent because it did not interfere with any routine assessments or treatments (CIRB 2010/810/C).

2.2. Severe exacerbations

Severe exacerbations were defined according to ATS/ERS guidelines10 as events requiring hospitalization or ED visit for asthma and systemic corticosteroids ≥3 days. Data on severe exacerbations fulfilling these criteria were obtained from nationwide electronic records, including inpatient discharges, ED consults, and prescriptions. Near‐fatal asthma (NFA) exacerbations were defined as events requiring mechanical ventilation (invasive and noninvasive). For the derivation cohort presenting in 2011, annual severe exacerbation rates for five years was collected, retrospectively in 2010 and prospectively for 2011‐2014. For the validation cohort presenting in 2012 and 2013, severe exacerbation rates over three years (one‐year retrospective and two‐year prospective) were obtained.

2.3. Measurements

Spirometry was performed according to ATS/ERS guidelines11 using a Medgraphics, USA spirometer. Predicted values were obtained from Morris et al.12 and an adjustment factor of 0.94 was applied for FEV1 and forced vital capacity (FVC) as recommended for Asian patients.13 Comorbidities were evaluated by obtaining history and reviewing medical records. The diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) was made on the basis of suggestive symptoms and response to empirical treatment with proton pump inhibitors and/or prokinetic agents, or confirmed via esophageal pH monitoring. The diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea was confirmed with polysomnography, and diagnoses of anxiety and depression were made by formal psychiatric assessment with history and mental state examination.

Geometric means of serum eosinophil counts were obtained retrospectively from repeated measures done in 2011. Adherence was quantified using the medication possession ratio, defined as the ratio between the sum of days' supply to the sum of days' prescribed, and calculated from hospital electronic pharmacy records for ICS+LABA in 2011 and 2014.

2.4. Identification of clinically distinct trajectories and comparisons between trajectories

A trajectory describes the change of a measured variable over time. To identify clinically distinct trajectories of severe exacerbation rates, we used the statistical method group‐based trajectory modeling,14 which assumes that the population is composed of distinct groups, each with a different underlying trajectory of a variable measured repeatedly over time. It identifies trajectory shapes over time as well as subgroups of individuals with similar trajectories.

The Stata procedure Proc Traj was employed for this analysis.15 The number of severe exacerbations was modeled as a zero‐inflated Poisson distribution or alternatively as a negative binomial distribution. Different models with varying number of groups and polynomial orders were compared to find the best‐fit model. The number of trajectories specified in the model was increased stepwise from 2 to 5, and the best‐fitting number of trajectories was selected using Bayesian information criterion (BIC). After identifying the number of trajectories, different shapes for trajectories (intercept‐only, linear, quadratic, cubic) were tested. Patients were classified according to a specific trajectory on the basis of the maximum estimated probability of assignment. A probability of 0.9 or higher was considered an excellent fit, whereas a value of less than 0.7 was considered a poor fit.15

2.5. Derivation of the clinical risk score

To derive the clinical risk score, we used a univariate‐based method.16 Baseline variables found to be significantly different in the most unfavorable trajectory compared to the other trajectories were selected for inclusion in the clinical risk score. Each variable was converted into a categorical variable, using cutoffs that were determined based on mean or median values of the different trajectory groups.

Each component of the risk score was then allocated a weight by first entering all the components into a multivariate logistic regression model predicting the probability of following the most unfavorable trajectory and then rounding up the regression coefficients to the nearest integers. The predictive accuracy of the final clinical risk score was expressed as area under the receiver operating characteristic curve.

2.6. Validation of the trajectories and clinical risk score

External validation of the derived trajectories and clinical risk score was performed on an independent cohort presenting in 2012 and 2013, using severe exacerbation data spanning three years.

2.7. Statistical analyses

The Student's t‐test, Chi‐square test, or Mann‐Whitney test were used for parametric, categorical, or nonparametric data, respectively. To test for monotonic trends, we used one‐way ANOVA, linear‐by‐linear analysis, or the Jonckheere‐Terpstra test for parametric, categorical, or nonparametric variables, respectively.

3. Results

Of the 205 patients presenting in 2011 who were on GINA step 4 treatment, 177 met eligibility criteria and formed the derivation cohort. Baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. At the end of 2014, 147 of the 177 patients were still on active follow‐up at the clinic.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics for derivation and validation cohorts

| Patient characteristics | Derivation cohort n=177 | Validation cohort n=84 | P‐value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 56 ± 18 | 50 ± 19 | .02 |

| Sex (% female) | 95 (53.7%) | 52.0 (61.9%) | .21 |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Chinese | 115 (65.0%) | 52 (61.9%) | .58 |

| Malay | 23 (13.0%) | 8 (9.5%) | |

| Indian | 30 (16.9%) | 17 (20.2%) | |

| Others | 9 (5.1%) | 7 (8.3%) | |

| Age of onset (y) | 33 (10‐49) | 21 (5‐40) | .004 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 25.6 ± 5.6 | 25.1 ± 6.0 | .53 |

| Current smoker | 17 (9.6%) | 13 (15.5%) | <.01 |

| Asthma Control Test score < 20 | 89 (50.3%) | 44 (52.4%) | .20 |

| ≥ 1 ED visit of hospitalization in the past year | 87 (49.2%) | 53 (63.1%) | .02 |

| ≥ 2 steroid bursts in the past year | 121 (68.4%) | 25 (29.8%) | .19 |

| Airflow limitation at baseline (prebronchodilator FEV1<80% pred) | 121 (68.4%) | 58 (69.0%) | .41 |

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation or percentages.

FEV1, forced expiratory volume in one‐second; ED, emergency department.

The best‐fit group‐based trajectory model was a three‐trajectory solution using the zero‐inflated Poisson distribution (BIC=−944) and is presented here. The average probability of assignment for each trajectory ranged from 0.94 to 0.96, indicating that patients matched well with their assigned trajectories. The negative binomial model (Fig.S1) had similar trajectory groups and shapes but poorer fit on the same data as indicated by a BIC of −373.

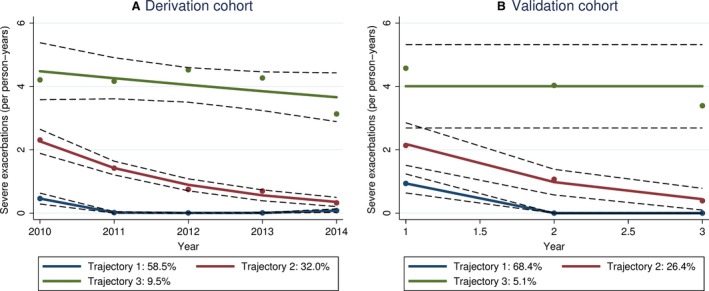

Figure 1A shows the three distinct trajectories of severe exacerbation rates identified by group‐based trajectory modeling. First, the majority of patients (58.5%) had stable disease with few intermittent severe exacerbations (Trajectory 1, “infrequent severe exacerbations”). A second group of patients (32.0%) had frequent severe exacerbations at baseline, but exacerbation rates gradually declined in the following years (Trajectory 2, “nonpersistently frequent severe exacerbations”). Third, a small subgroup (9.5%) exhibited, on average, frequent severe exacerbations in every year (Trajectory 3, “persistently frequent severe exacerbations”). Of note, this trajectory also included two patients who had no severe exacerbations at all in 2010 and/or 2011 but had ≥ 2 severe exacerbations in every subsequent year. These overall trajectories did not change after adjustment for age, sex, ethnic group, and severe exacerbation rate in 2010, or after excluding current smokers.

Figure 1.

Distinct trajectories of severe exacerbation rates identified by group‐based trajectory modeling for (A) derivation cohort recruited in 2011 and (B) validation cohort recruited in 2012 and 2013. Solid lines: predicted values, dashed lines: 95% confidence intervals, dots: observed values

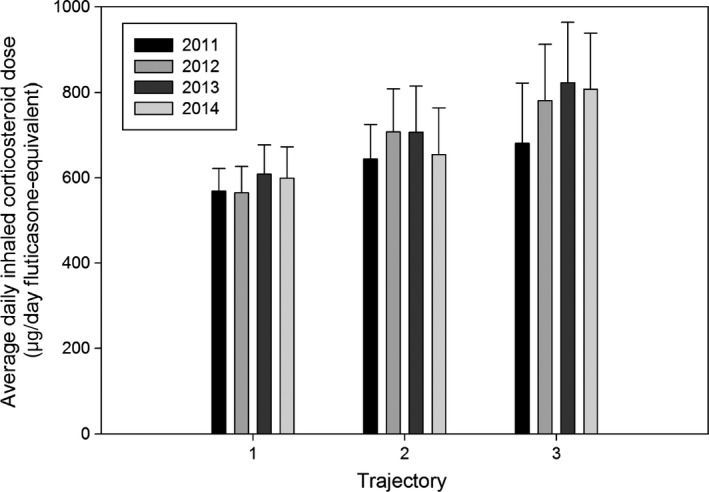

Incidence of NFA in the follow‐up period was highest in Trajectory 3 (0.28 events/5‐person‐years) compared to the other two trajectories (0.06 and 0.01 events/5‐person‐years for Trajectory 1 and Trajectory 2, respectively; incidence rate ratio: 11.0, 95% confidence interval, CI: 1.1‐104.3, P=.036 for Trajectory 3 vs. trajectories 1 and 2). ICS doses showed a significant increasing trend from Trajectory 1 to 3 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Daily inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) dose by year, expressed as ug/day fluticasone equivalent. Error bars: 95% confidence interval. Data were available for 171 patients in 2011, 143 patients in 2012, 128 patients in 2013, and 121 patients in 2014. There was a statistically significant increasing trend of the daily ICS dose in ascending order from Trajectory 1 to 3 (Jonckheere‐Terpstra test, P=.04 in 2011, P=.003 in 2012, P=.01 in 2013, P=.024 in 2014)

Table 2 shows univariate analyses comparing Trajectory 3 against the other two trajectories. Six variables were significantly higher in Trajectory 3: body mass index (BMI), history of NFA, number of severe exacerbations in the previous year, and the prevalence of GERD, OSA, and depression. Serum eosinophils and medication possession ratio were not significantly different when comparing Trajectory 3 to the other trajectories.

Table 2.

Characteristics of different trajectory groups

| Variable | Trajectory 1: Infrequent exacerbators | Trajectory 2: Nonpersistently frequent exacerbators | Trajectory 3: Persistently frequent exacerbators | Significance (P‐value for Trajectory 3 vs. trajectories 1 and 2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients (n) | 106 | 53 | 18 | |

| Age (y) | 56 ± 19 | 55 ± 18 | 63 ± 16 | .131 |

| Age of asthma onset (y), | 33 (10‐52) | 36 (10‐46) | 36 (15‐66) | .374 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 24.9 ± 5.5 | 25.8 ± 5.6 | 28.8 ± 5.7 | a.009 |

| Female gender, n (%) | 54 (50.9%) | 29 (54.7%) | 12 (66.7%) | .243 |

| Family history of asthma, n (%) | 22 (20.8%) | 10 (18.9%) | 6 (33.3%) | .196 |

| History of near‐fatal asthma, n (%) | 4 (3.8%) | 3 (5.7%) | 3 (16.7%) | a.033 |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 12 (11.3%) | 3 (5.6%) | 2 (11.1%) | .082 |

| Asthma Control Test score | 20 (17‐22)Mode: 20 | 18 (15‐21)Mode: 18 | 19 (15‐21)Mode: 15 | .517 |

| On omalizumab/systemic steroids/long‐acting anticholinergic | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (11.1%) | a<.001 |

| Severe exacerbations in 2010 | 0 (0‐1) | 2 (1‐4) | 4 (2‐5) | a<.001 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||||

| Allergic rhinitis | 54 (50.9%) | 30 (56.6%) | 10 (55.6%) | .826 |

| Eczema | 2 (1.9%) | 4 (7.5%) | 2 (11.1%) | .156 |

| Aspirin sensitivity | 7 (6.6%) | 2 (3.8%) | 3 (16.7%) | .078 |

| Reflux disease | 15 (14.2%) | 7 (13.2%) | 7 (38.9%) | a.006 |

| Obstructive sleep apnea | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (5.7%) | 2 (11.1%) | a.025 |

| Anxiety | 2 (1.9%) | 2 (3.8%) | 1 (5.6%) | .461 |

| Depression | 3 (2.8%) | 1 (1.9%) | 3 (16.7%) | a.004 |

| Lung function | ||||

| FEV1% predicted | 68 ± 22 | 73 ± 22 | 74 ± 23 | .508 |

| FVC % predicted | 74 ± 18 | 75 ± 18 | 80 ± 20 | .171 |

| FEV1/FVC ratio (%) | 69 ± 14 | 73 ± 12 | 67 ± 14 | .388 |

| Serum eosinophils | 0.246 ± 0.288 | 0.254 ± 0.515 | 0.194 ± 0.402 | .367 |

| No. of patients | 37 | 37 | 18 | |

| Medication possession ratio | ||||

| 2011 | 0.58 ± 0.33 | 0.57 ± 0.31 | 0.51 ± 0.26 | .420 |

| No. of patients | 93 | 46 | 14 | |

| 2014 | 0.51 ± 0.33 | 0.43 ± 0.32 | 0.60 ± 0.52 | .337 |

| No. of patients | 44 | 24 | 10 | |

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation, median (interquartile range) or percentages. Serum eosinophils are reported as geometric mean ± standard deviation.

FEV1, forced expiratory volume in one‐second; FVC, forced vital capacity; ICS, inhaled corticosteroids.

P‐values are reported for Student's t‐test, Mann‐Whitney, or Chi‐squared tests.

Statistically significant differences (P<.05).

The full multivariate logistic regression model to predict persistently frequent exacerbations is shown in Table 3. Hosmer‐Lemeshow goodness‐of‐fit test indicated that this model was well calibrated (Chi‐square=4.769, df=5, P=.445). Although “≥2 ED visits or hospitalizations in the past year” was the only variable independently associated with persistently frequent exacerbations, the discrimination coefficient, R2 , of the full model (0.339) was higher than a simplified model incorporating only this variable (0.222). The other variables such as BMI, NFA, GERD, OSA, and depression are recognized and clinically relevant risk factors for frequent exacerbations,17 justifying their inclusion to improve performance of the model. “≥2 ED visits or hospitalizations in the past year” was assigned a weight of +2 reflecting both its independent association with persistently frequent severe exacerbations and the magnitude of its regression coefficient, whereas other components of the score were assigned a weight of +1 by rounding up the regression coefficients to the nearest integer.

Table 3.

Clinical risk score for persistently frequent severe exacerbations

| Variable | Odds ratio, 95% confidence interval | P‐value | β | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ED visits or hospitalizations for asthma ≥ 2 in the past year | 9.8 (2.6‐37.4) | .001 | 2.3 | +2 |

| Body mass index ≥ 25 | 3.3 (0.9‐11.8) | .064 | 1.2 | +1 |

| History of near‐fatal asthma | 1.9 (0.3‐14.0) | .534 | 0.6 | +1 |

| Depression | 3.0 (0.4‐24.9) | .304 | 1.1 | +1 |

| Obstructive sleep apnea | 1.7 (0.2‐17.2) | .638 | 0.6 | +1 |

| Gastroesophageal reflux | 2.6 (0.8‐9.2) | .131 | 1.0 | +1 |

Each variable was allocated a score based on the regression coefficient (β) in a multivariate logistic regression, by rounding up β to the nearest integer.

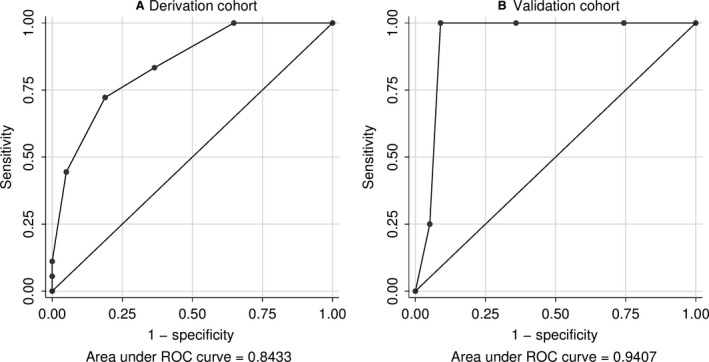

Sensitivity and specificity of the risk score at different cut‐points are shown in Table 4. A cut‐point of ≥3 had a sensitivity of 72.2% and specificity of 81.1% for identifying persistently frequent severe exacerbators in the derivation cohort. The area under the receiver operating characteristics curve (AUC) (Figure 3A) was 0.84 (95% CI: 0.75‐0.93, P<.001) indicating good accuracy at discriminating persistently frequent severe exacerbators.

Table 4.

Sensitivity and specificity of different cut‐points for the clinical prediction rule to identify persistently frequent exacerbators

| Cut‐point | Derivation cohort | Validation cohort | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity, % | Specificity, % | Sensitivity, % | Specificity, % | |

| ≥ 0 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 | 0.0 |

| ≥ 1 | 100.0 | 35.2 | 100.0 | 27.5 |

| ≥ 2 | 83.3 | 63.5 | 100.0 | 51.3 |

| ≥ 3 | 72.2 | 81.1 | 100.0 | 71.3 |

| ≥ 4 | 44.4 | 95.0 | 100.0 | 91.3 |

| ≥ 5 | NAa | NAa | 25.0 | 95.0 |

| ≥ 6 | 11.1 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

| 7 | 5.6 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 100.0 |

NA, not applicable: sensitivity and specificity not available because no individual in the derivation cohort had a score of 5.

Figure 3.

Receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve for the clinical risk score to identify persistently frequent severe exacerbators in (A) the derivation cohort (n=177) and (B) the validation cohort (n=84)

In the validation cohort (Table 1 for baseline characteristics), group‐based trajectory modeling replicated the three trajectories (Figure 1B). Similar to the derivation cohort, there was an increasing trend from Trajectory 1 to 3 in terms of severe exacerbation rate in the first year (median 1 vs. 2 vs. 4, Jonckheere‐Terpstra test, P<.001), depression (1.6% vs 5.9% vs 25.0%, linear‐by‐linear P=.026), history of near‐fatal asthma (9.5% vs. 41.2% vs. 50.0%, linear‐by‐linear P=.001), and GERD (14.3% vs. 17.6% vs. 75.0%, linear‐by‐linear P=.020). BMI showed an increasing trend that did not reach significance (24.7 vs. 25.3 vs. 29.6, linear contrast analysis, P=.120). Prevalence of OSA did not differ between trajectory groups in the validation cohort. The clinical risk score had excellent performance in the validation cohort (Figure 3B) with an AUC of 0.94 (95% CI: 0.86‐0.97) and good sensitivity/specificity at cut‐points of ≥3 or ≥4 (Table 4).

4. Discussion

In this five‐year observational study, we have identified distinct clinical trajectories of problematic asthma: 1) stable disease with few, infrequent severe exacerbations, 2) frequent severe exacerbations initially, with resolution of recurrent exacerbations over time, or 3) persistently frequent severe exacerbations with increased incidence of near‐fatal asthma. We have also developed and prospectively validated a simple clinical risk prediction score capable of identifying, at baseline, patients who will subsequently follow the most unfavorable trajectory of persistently frequent severe exacerbations. The components of the clinical risk score are easy to use in clinical practice and had excellent performance in an independent validation cohort. The components are: ≥2 severe exacerbations in the past year (+2), history of NFA, BMI≥25kg/m2, GERD, depression, and OSA (+1 each). A score of ≥3 represents high risk of an unfavorable trajectory.

By analyzing long‐term trajectories, we have addressed a major unmet need in severe/difficult asthma of discerning prognosis and future risk of severe exacerbation occurrences over the long term. Previous studies aimed at identifying distinct asthma phenotypes, for example, by cluster analysis,18, 19 did not take into account long‐term disease trajectory as a potential source of heterogeneity in asthma and used cross‐sectional or short‐term prospective data, thus limiting the usefulness of the derived phenotypes at discriminating future prognosis. Cluster analysis of the British Thoracic Society Severe Asthma Registry20 found that cluster membership was not stable over a median follow‐up of three years, indicating loss of validity over time, which in retrospect is not unexpected given our current data. Another study found that asthma clusters21 could not predict future risk of exacerbations, the primary focus of our work. Existing scoring systems are only able to predict healthcare utilization in severe or difficult asthma over the short term (6‐12 months),6, 7 whereas the clinical risk score presented here identifies persistently frequent severe exacerbators over a prolonged period of up to 4 years. The components of the score are based on information readily available in the clinical setting and already have established associations with severe and difficult asthma.22, 23, 24, 25

We propose that assessing future risk of severe exacerbations using long‐term trajectories can complement existing state‐of‐the‐art clinical phenotyping and molecular endotyping approaches in tailoring asthma treatment. Cross‐sectional phenotyping does not reliably inform prognosis but has shown benefit for informing likely effective therapies. Conversely, a trajectory‐based approach may help identify patients who are at high risk of an unfavorable disease trajectory and for whom specialist care and advanced treatments are the most indicated, but will not inform the type of advanced treatment that will be effective. To illustrate the point, consider patients in trajectories 2 and 3 who both had mean eosinophil counts in excess of 0.15 × 109/L and frequent severe exacerbations (≥2) in the baseline year, two clinical features which in combination have been found to predict response to the anti‐IL5 agent mepolizumab.26 Using trajectories to assess future risk, Trajectory 2 patients are projected to experience improvement in severe exacerbation rates in subsequent years while receiving systematic care in a specialist asthma clinic (Trajectory 2), thereby potentially mitigating a need for mepolizumab. Indeed, the majority of problematic asthma patients presenting to specialist centers are uncontrolled due to reversible factors such as nonadherence,27, 28 and can improve with conventional treatments and systematic care to confirm the diagnosis, identify and treat comorbidities, and optimize adherence—in such patients, expensive biologics may be unnecessary, even inappropriate. In contrast, patients in Trajectory 3 remain at persistently high risk for recurrent exacerbations, strengthening the rationale for considering biologics such as mepolizumab (or alternative treatments specifically directed at patients with the highest future exacerbation risks). The clinical risk scores thus allow us to identify, stratify, and differentiate persistently frequent severe exacerbators who are at the highest risk, from the broader population of all initially frequent severe exacerbators. Despite this, it is important to note that the actual clinical impact of assessing trajectories over the longer term requires further study.

Our study does have limitations. First, we did not include exacerbations that were less severe, such as those that could be managed at home with rescue bronchodilator use or standby systemic steroids not warranting hospitalization or an ED visit.10 We focused exclusively on severe exacerbations (requiring hospitalization or ED visit) because these are associated with high healthcare burden,1 are the most important objective and recognized markers of asthma control in both clinical and research settings,10 and can be reliably assessed by our methodology. Second, the trajectories and clinical risk score were derived from an Asian cohort and degree of generalizability to other global populations requires future assessment. Additional validation in other populations and healthcare settings is warranted and a promising avenue for future work. Third, adherence in our cohort was suboptimal, potentially influencing recorded severe exacerbation rates. However, no significant differences in adherence rates could explain the distinct trajectories in our data. Furthermore, poor adherence is a well‐recognized, real‐world phenomenon occurring even in specialist asthma services.27, 29 Despite our inclusion of current smokers in the initial analysis, trajectories were similar following repeat analysis excluding this group. While we assessed some limited data on serum eosinophils, our study did not assess other potential asthma biomarkers; however, future research should focus on investigating biomarkers with the potential to predict future trajectories. Last but not least, this was a real‐life study which is subject to a number of potential confounders, but nevertheless provides useful information on real‐world patterns of disease.

In summary, patients with problematic asthma follow distinct illness trajectories over a period of five years based on severe exacerbation frequency. We have derived and validated a clinical risk score that can accurately identify patients who will have persistently frequent severe exacerbations over the long term. Knowing the illness trajectory of a patient early in their clinical course allows clinicians to intervene at the earliest timepoint with the intent of altering the future trajectory. Discerning asthma trajectories complements and extends the exciting phenotyping and endotyping methodologies in current use.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Author contributions

All authors made contributions to the study design, data acquisition, data analysis, data interpretation, and/or revising of the manuscript for critical intellectual content. MSK had full access to the study data and takes full responsibility for the content of the manuscript, including the data and analysis.

Supporting information

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ms. Karen Tan, Ms. Florence Yeo, Ms. Zeng Bao Yi, and Ms. Celeste Curioso Suarez, the Singapore General Hospital EMR SCM Team and Pharmacy Department, for help with data collection, and Dr. Fan Qiao, Ms. Xin Xiaohui, and Ms. Kanchanadevi Balasubramaniam for help with statistical analysis.

Yii ACA, Tan JHY, Lapperre TS, et al. Long‐term future risk of severe exacerbations: Distinct 5‐year trajectories of problematic asthma. Allergy. 2017;72:1398–1405. https://doi.org/10.1111/all.13159

Edited by: Michael Wechsler

References

- 1. Masoli M, Fabian D, Holt S, Beasley R. The global burden of asthma: executive summary of the GINA Dissemination Committee report. Allergy. 2004;59:469‐478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kupczyk M, ten Brinke A, Sterk PJ, et al. Frequent exacerbators–a distinct phenotype of severe asthma. Clin Exp Allergy. 2014;44:212‐221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Calhoun WJ, Haselkorn T, Miller DP, Omachi TA. Asthma exacerbations and lung function in patients with severe or difficult‐to‐treat asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;136:1125‐1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dougherty RH, Fahy JV. Acute exacerbations of asthma: epidemiology, biology and the exacerbation‐prone phenotype. Clin Exp Allergy. 2009;39:193‐202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Global Initative for Asthma . Global strategy for asthma management and prevention. 2015. Available at: http://www.ginaasthma.org. Accessed: 2 March 2016

- 6. Miller MK, Lee JH, Blanc PD, et al. TENOR risk score predicts healthcare in adults with severe or difficult‐to‐treat asthma. Eur Respir J. 2006;28:1145‐1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Eisner MD, Yegin A, Trzaskoma B. SEverity of asthma score predicts clinical outcomes in patients with moderate to severe persistent asthma. Chest. 2012;141:58‐65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bel EH, Sousa A, Fleming L, Bush A, Chung KF, Versnel J, et al. Diagnosis and definition of severe refractory asthma: an international consensus statement from the Innovative Medicine Initiative (IMI). Thorax 2011;66:910‐917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chung KF, Wenzel SE, Brozek JL, et al. International ERS/ATS guidelines on definition, evaluation and treatment of severe asthma. Eur Respir J. 2014;43:343‐373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Reddel HK, Taylor DR, Bateman ED, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: asthma control and exacerbations: standardizing endpoints for clinical asthma trials and clinical practice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:59‐99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, et al. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J. 2005;26:319‐338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Morris JF, Koski A, Johnson LC. Spirometric standards for healthy nonsmoking adults. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1971;103:57‐67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pellegrino R, Viegi G, Brusasco V, et al. Interpretative strategies for lung function tests. Eur Respir J. 2005;26:948‐968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nagin DS, Odgers CL. Group‐based trajectory modeling in clinical research. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2010;6:109‐138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jones BL, Nagin DS, Roeder K. A SAS procedure based on mixture models for estimating developmental trajectories. Sociol Methods Res. 2001;29:374‐393. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Adams ST, Leveson SH. Clinical prediction rules. BMJ. 2012;344:d8312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Boulet L‐P, Boulay M‐È. Asthma‐related comorbidities. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2011;5:377‐393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Moore WC, Meyers DA, Wenzel SE, et al. Identification of asthma phenotypes using cluster analysis in the severe asthma research program. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181:315‐323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Haldar P, Pavord ID, Shaw DE, et al. Cluster analysis and clinical asthma phenotypes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:218‐224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Newby C, Heaney LG, Menzies‐Gow A, et al. Statistical cluster analysis of the British Thoracic Society Severe refractory Asthma Registry: clinical outcomes and phenotype stability. PLoS One. 2014;9:e102987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bourdin A, Molinari N, Vachier I, et al. Prognostic value of cluster analysis of severe asthma phenotypes. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134:1043‐1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Boulet L‐P. Influence of comorbid conditions on asthma. Eur Respir J. 2009;33:897‐906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. ten Brinke A, Sterk PJ, Masclee AAM, et al. Risk factors of frequent exacerbations in difficult‐to‐treat asthma. Eur Respir J. 2005;26:812‐818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Aubas C, Bourdin A, Aubas P, et al. Role of comorbid conditions in asthma hospitalizations in the south of France. Allergy. 2013;68:637‐643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Haselkorn T, Zeiger RS, Chipps BE, et al. Recent asthma exacerbations predict future exacerbations in children with severe or difficult‐to‐treat asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124:921‐927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Pavord ID, Korn S, Howarth P, et al. Mepolizumab for severe eosinophilic asthma (DREAM): a multicentre, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;380:651‐659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Gamble J, Stevenson M, McClean E, Heaney LG. The prevalence of nonadherence in difficult asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:817‐822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hekking P‐PW, Wener RR, Amelink M, Zwinderman AH, Bouvy ML, Bel EH. The prevalence of severe refractory asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135:896‐902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Robinson DS, Campbell DA, Durham SR, Pfeffer J, Barnes PJ, Chung KF. Systematic assessment of difficult‐to‐treat asthma. Eur Respir J. 2003;22:478‐483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials