Abstract

Objectives

Ultrasonography (US) is sensitive for detecting echostructural abnormalities of the major salivary glands (SGs) in primary Sjögren’s syndrome (pSS). Our objectives were to define selected US-SG echostructural abnormalities in pSS, set up a preliminary atlas of these definitions and evaluate the consensual definitions reliability in both static and acquisition US-SG images.

Methods

International experts in SG US in pSS participated in consensus meetings to select and define echostructural abnormalities in pSS. The US reliability of detecting these abnormalities was assessed using a two-step method. First 12 experts used a web-based standardised form to evaluate 60 static US-SG images. Intra observer and interobserver reliabilities were expressed in κ values. Second, five experts, who participated all throughout the study, evaluated US-SG acquisition interobserver reliability in pSS patients.

Results

Parotid glands (PGs) and submandibular glands (SMGs) intra observer US reliability on static images was substantial (κ > 0.60) for the two main reliable items (echogenicity and homogeneity) and for the advised pSS diagnosis. PG inter observer reliability was substantial for homogeneity. SMGs interobserver reliability was moderate for homogeneity (κ = 0.46) and fair for echogenicity (κ = 0.38). On acquisition images, PGs interobserver reliability was substantial (κ = 0.62) for echogenicity and moderate (κ = 0.52) for homogeneity. The advised pSS diagnosis reliability was substantial (κ = 0.66). SMGs interobserver reliability was fair (0.20< κ ≤ 0.40) for echogenicity and homogeneity and either slight or poor for all other US core items.

Conclusion

This work identified two most reliable US-SG items (echogenicity and homogeneity) to be used by US-SG trained experts. US-PG interobserver reliability result for echogenicity is in line with diagnosis of pSS.

Keywords: Ultrasound, Salivary glands, Primary Sjögren’s syndrome, Atlas, Classification criteria

Key messages.

What is already known about this subject?

Diagnosis of primary Sjögren’s syndrome (pSS) is a challenge.

Ultrasound of salivary glands (US-SG) is a valuable diagnostic tool.

Yet there is no gold standard of US diagnosis for echostructural abnormalities in pSS.

What does this study add?

This work put forward a preliminary atlas of echostructural abnormalities in pSS.

This work identified two most reliable US-SG items: echogenicity and homogeneity.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

Trained US-SG experts can use our preliminary atlas of US-SG abnormalities.

This can be done concomitantly with other classification criteria in diagnosis of pSS.

Introduction

Lymphocytic infiltration of the salivary glands (SGs) is a key pathological feature of primary Sjögren’s syndrome (pSS).1 2 Currently available tools for assessing the SGs include salivary flow measurement, minor SG biopsy, sialography, scintigraphy, CT and MRI. Ultrasonography (US) was introduced more recently.3–7 US holds considerable appeal, as it is non-invasive, does not involve ionising radiation, can be repeated many times and is available as an outpatient investigation. Both researchers and clinicians have identified US as a valuable tool for diagnosing pSS8–15 and as a potential source of classification criteria for this disease. Moreover, the advent of new treatments for pSS16 has created a need for valid and easy-to-use imaging tools capable of detecting changes in disease activity over time.17 Using the Outcome Measures in Rheumatology (OMERACT) filter,18 we recently reported the need for a consensual scoring system, SG US expert training as well as evaluation of US criterion validity, that is, comparing minor SG biopsy to minor SG US.19 The review results were consistent with those of the literature20–25 and our review is the first step in setting up an OMERACT standard that will open further avenues for the use of such promising diagnostic tool.26 Today, US cannot yet be used as the sole diagnostic bedside tool in pSS but as an early diagnostic tool when used carefully by experienced US experts.

Here, our objectives were to define selected US-SG echostructural abnormalities in pSS, set up a preliminary atlas of these definitions and evaluate the consensual definitions reliability in both static and acquisition US-SG images.

Method

Definition of the core items of ultrasound SGs

During the 2012 American Congress of Rheumatology meeting, international pSS experts (from France, Norway, Italy, England, Serbia, Slovenia, Sweden, The Netherlands and USA) who had at least 5 years of experience with US in pSS were invited to work on the study. Among 10 experts, only 6 contributed to the first meeting towards achieving a consensus definition of US-SG abnormalities in pSS. They selected a preliminary core set of US-SG items worthy of routine evaluation. These experts then completed an email questionnaire, indicating whether they agreed with each definition (yes/no answers). The same six experts followed up to the 2013 and 2014 European League of Rheumatism (EULAR) meetings where preliminary 2012 meeting results were presented.

Set-up of a SG ultrasound atlas

Finally, in 2014 consensus was reached in regard with the US-SG core items and a preliminary atlas was set forth.

This initial atlas included only consensual B-mode images in pSS and will be used by the experts.

Reliability of US-SG core items on static US images

Twelve experts performed a web-based standardised form (table 1) to evaluate 60 static images (30 parotid glands (PGs) and 30 submandibular glands (SMGs)) (Philips iU22, 12.5 MHz linear array transducer; Philips Healthcare, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). The set of B-mode images (with the same setting) of the major SGs, from Brest centre data bank, of patients with pSS and normal individuals was chosen in order to have both images of normal (healthy individuals) and abnormal SG parenchymal echostructure (pSS patients) and were sent to other centres. Each expert evaluated the items selected by consensus (ie, the preliminary atlas) in two rounds, at an interval of 3 months. Then an advice for pSS diagnosis (rule out, rule in, indeterminate) was given by the experts. The results were used to assess interobserver and intraobserver reliabilities. All images were read anonymously and in random order.

Table 1.

Standardised form used to assess the reliability of ultrasound of salivary gland core items of the images

| Parotid glands | Submandibular glands | |||

| Right | Left | Right | Left | |

| Echogenicity | ||||

| Normal, (0); Abnormal (fibrosis), 1 | ||||

| Homogeneity | ||||

| Normal, 0; Abnormal, 1 | ||||

| Hyperechoic bands | ||||

| None (0), <50% of the parenchyma (1), ≥50% (2) | ||||

| Number of hypoechoic/anechoic areas* | ||||

| Size of the largest hypoechoic/anechoic area (mm)* | ||||

| Location of the hypoechoic/anechoic areas in the gland | ||||

| None (0), isolated (<25% of the surface area) (1), localised (25%–50%) (2), scattered (>50%) (3), diffused (4) | ||||

| Number of abnormal lymph nodes in the glands* | ||||

| Presence of normal lymph nodes at the upper and/or lower poles of the parotid glands: no (0), yes (1) | ||||

| Calcifications | ||||

| No (0), yes (1) | ||||

| Posterior border visible | ||||

| No (0), yes (1) | ||||

| Diagnosis advice of pSS based on the seven items | ||||

| ruled out (0), indeterminate (1), ruled in (2) | ||||

*Quantitative variables were then categorised as follows: number of hypoechoic/anechoic areas: None (0), 1–4 (1), ≥5 (2); size of the largest area: None (0), ≤2 (1), >2 (2); abnormal lymph nodes: No (0), Yes (1).

pSS, primary Sjögren’s syndrome.

Reliability of US-SG core items on acquisition imaging in patients with pSS

Five experts, of the initial six who participated in development of the definitions and the atlas, participated in assessment of the reliability of the consensual items in acquisition imaging. Over a 2-day period, each expert performed US of both PGs and both SMGs of 19 patients with pSS (with or without known SG abnormalities). Various US machines were used (Mylab ALPHA, Mylab60 and Mylab 6; all from Esaote, Genoa, Italy). Given the difference in each patient’s SG echogenicity US B-mode settings were adjusted according to each patient. The time needed for each expert to examine the 19 patients was recorded. Approval was obtained from Brest ethics committee and the study was referred in clinical trial (NCT 02358213).

Statistical analysis

Cohen’s κ was used to measure interobserver agreement for binary items. Weighted κ (Fleiss-Cohen weights) was used for items with more than two ordinal categories.27 κ coefficients were calculated for each pair of observers, leading to mean value, minimum and maximum for each item. The same coefficients were calculated for each observer to measure intraobserver agreement between the first and the second interpretation, leading to mean value, minimum and maximum for each US-SG core item.28

Number of hypoechoic or anechoic areas was recorded as: none, 1–4 or ≥5 and location was reported as follows: none, isolated, localised, scattered or diffuse. Number of abnormal lymph nodes was recorded as present or absent. Diagnosis advice was reported as follows: ruled out, indeterminate or ruled-in.

According to Landis and Koch,29 κ values were interpreted as follows: <0.00 poor, 0.00–0.20 slight, 0.21–0.40 fair, 0.41–0.60 moderate, 0.61–0.80 substantial and 0.81–1.00 almost perfect.

Results

Definition of US-SG echostructural abnormalities (US-SG core items)

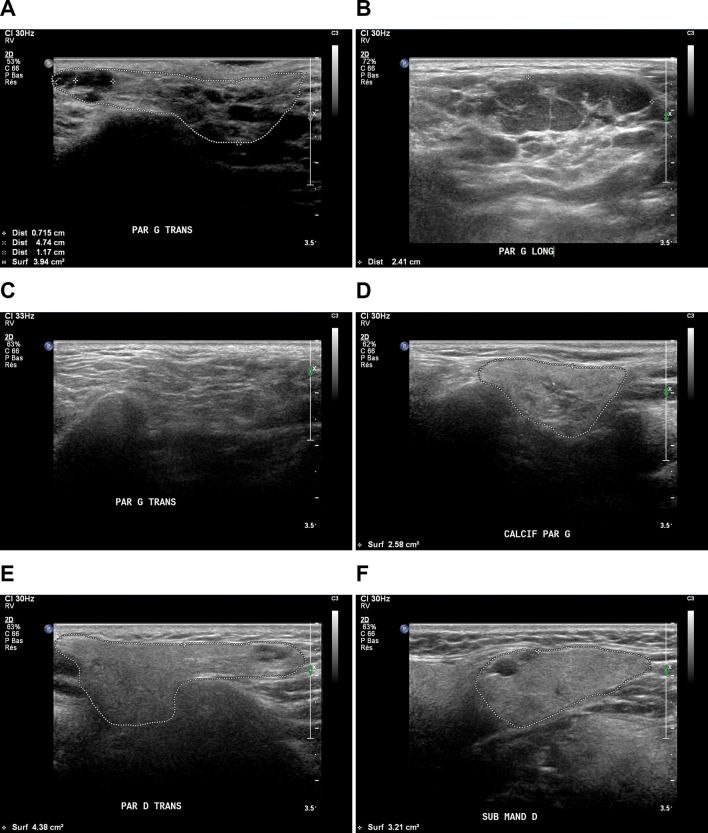

The experts selected the US-SG echostructural abnormalities related to: echogenicity, homogeneity, lymph nodes, posterior border, in B-mode (see online supplementary table 1). The definitions developed during the first meeting were modified during the second meeting (see online supplementary table 1). Complete agreement was reached about the following items definitions: echogenicity, homogeneity, lymph nodes, posterior border, calcification, hyperechoic bands, hypoechoic/anechoic areas, location of hypoechoic/anechoic areas and abnormal lymph nodes. We called these items US-SG core items. An initial consensual reference atlas (33 consensual images) was developed based on these definitions (figure 1 and see online supplementary atlas).

rmdopen-2016-000364supp001.docx (21.8KB, docx)

rmdopen-2016-000364supp002.pdf (1.9MB, pdf)

Figure 1.

The core items were (A) hypoechogenicity, (B) heterogeneity (numerous anechoic areas), (C) hyperechoic bands, (D) calcifications (star), (E) lymph nodes (white arrow), (F) anechoic area, (A, D,E,F) posterior border (dotted line).

Reliability of SG ultrasound core items using static images

Intraobserver reliability

PG intraobserver US reliability was substantial for: echogenicity, homogeneity, number and location of hypoechoic/anechoic areas, and normal lymph nodes. The advised pSS diagnosis reliability was substantial (κ=0.86) (table 2). In contrast, intraobserver reliability was moderate for hyperechoic bands, number of abnormal lymph nodes, and fair for calcifications, posterior border visibility.

Table 2.

Intraobserver and interobserver reliability of static ultrasound core items of PG and SMG: κ values

| Echogenicity | Homogeneity | Hyperechoic bands | Number of hypoechoic/anechoic areas* | Location of hypoechoic/anechoic areas | Number of abnormal nodes* | Normal nodes | Calcifications | Posterior border visibility | Diagnosis advice† | |

| PG intraobserver | ||||||||||

| Mean | 0.75 | 0.75 | 0.58 | 0.80 | 0.78 | 0.47 | 0.66 | 0.38 | 0.37 | 0.86 |

| Min | 0.43 | 0.29 | 0.00 | 0.57 | 0.59 | 0.00 | 0.44 | −0.03 | −0.11 | 0.52 |

| Max | 0.93 | 1 | 1 | 0.92 | 0.94 | 1 | 0.90 | 1 | 0.80 | 1 |

| SMG intraobserver | ||||||||||

| Mean | 0.61 | 0.63 | 0.61 | 0.76 | 0.69 | 0.17 | 0.45 | 0.42 | 0.41 | 0.70 |

| Min | 0.23 | 0.25 | 0.36 | 0.54 | 0.45 | 0.00 | 0.00 | −0.05 | 0.00 | 0.33 |

| Max | 1 | 0.93 | 1 | 1 | 0.92 | 0.84 | 1 | 0.89 | 0.91 | 0.92 |

| PG interobserver | ||||||||||

| Mean | 0.60 | 0.66 | 038 | 0.74 | 0.77 | 0.19 | 0.54 | 0.10 | 0.15 | 0.78 |

| Min | 0.16 | 0.12 | 0.00 | 0.39 | 0.44 | −0.06 | 0.25 | −0.05 | −0.38 | 0.31 |

| Max | 0.93 | 1 | 0.88 | 0.96 | 0.94 | 1 | 0.90 | 0.65 | 0.59 | 0.98 |

| SMG interobserver | ||||||||||

| Mean | 0.38 | 0.46 | 0.32 | 0.53 | 0.52 | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.26 | 0.15 | 0.54 |

| Min | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.22 | 0.07 | −0.06 | −0.11 | 0.00 | −0.09 | 0.16 |

| Max | 0.92 | 0.93 | 0.79 | 0.90 | 0.92 | 0.27 | 0.67 | 1 | 0.65 | 0.91 |

*Quantitative variables were then categorised as follows: number of hypoechoic/anechoic areas: None (0), 1–4 (1), ≥5 (2); abnormal lymph nodes: No (0), Yes (1).

†Diagnosis advice was given in regard with the typical pattern of pSS on images and not in patients with pSS.

PG, parotid gland; pSS, primary Sjögren’s syndrome; SMG, submandibular gland.

SMG intraobserver US reliability was substantial for echogenicity, homogeneity, hyperechoic band, hypoechoic/anechoic areas and location. The results were moderate for normal lymph nodes, calcification and posterior border. The advised diagnosis reliability was substantial (κ=0.70).

Interobserver reliability

PG interobserver reliability was substantial for homogeneity, number and location of hypoechoic/anechoic areas and moderate for echogenicity and normal lymph nodes. The results were fair for hyperechoic bands and slight for calcification and posterior border. The advised diagnosis reliability was substantial (κ=0.78). SMG interobserver reliability was fair for echogenicity and calcification. The results were: moderate for homogeneity, hypoechoic/anechoic areas and location; slight for posterior border and normal lymph nodes. Advised diagnosis reliability was moderate (κ=0.54).

Distribution of ultrasound core items for static images

Item distributions were similar between the two readings. Echogenicity was regarded as normal in >50% of both PGs and SMGs. Homogeneity was regarded as abnormal in >50% of the SMGs and 48.6%–52.1% of the PGs. Hyperechoic bands occupying <50% of the gland surface area of both PGs and SMGs were seen in >50% of the cases (table 3). In all four SGs, hypoechoic/anechoic areas were not found in 44.9%–53.1% of cases, and ≥5 hypoechoic areas were found in 23.9%–33.0% of the cases. Normal-appearing lymph nodes were seen in >20% of PGs and <10% of SMGs. Abnormal lymph nodes and calcifications were rare in both PGs and SMGs. The posterior border was usually not visible, particularly for the SMGs.

Table 3.

Distribution of ultrasound items for static images

| Parotid glands | Submandibular glands | |||

| First reading | Second reading | First reading | Second reading | |

| Echogenicity | ||||

| Normal | 58.9% | 57.4% | 59.6% | 58.1% |

| Abnormal | 41.1% | 42.6% | 40.4% | 41.9% |

| Homogeneity | ||||

| Normal | 51.4% | 47.9% | 47.5% | 45.1% |

| Abnormal | 48.6% | 52.1% | 52.5% | 54.9% |

| Hyperechoic bands | ||||

| None | 36.1% | 36.5% | 42.8% | 41.5% |

| <50% | 51.9% | 52.1% | 54.2% | 52.7% |

| ≥50% | 11.9% | 11.4% | 3.1% | 5.9% |

| Number of hypoechoic/anechoic areas | ||||

| None | 53.1% | 48.2% | 49.7% | 44.9% |

| 1–4 | 14.2% | 18.8% | 26.4% | 28.5% |

| ≥5 | 32.7% | 33% | 23.9% | 26.6% |

| Location of hypoechoic/anechoic areas | ||||

| None | 51.4% | 47.3% | 49.0% | 44.7% |

| Isolated | 11.9% | 14.8% | 21.2% | 20.8% |

| Localised | 10.0% | 16.4% | 12.5% | 14.9% |

| Scattered | 6.4% | 3.9% | 5.0% | 4.8% |

| Diffuse | 20.3% | 17.5% | 12.3% | 14.9% |

| Normal nodes | ||||

| No | 73.6% | 73.3% | 92.5% | 93.6% |

| Yes | 26.4% | 26.7% | 7.5% | 6.4% |

| Abnormal nodes | ||||

| No | 93.3% | 94.7% | 98.0% | 98.6% |

| Yes | 6.7% | 5.3% | 2.0% | 1.4% |

| Calcifications | ||||

| No | 86.1% | 86.6% | 83.8% | 86.0% |

| Yes | 13.9% | 13.4% | 16.2% | 14.0% |

| Posterior border visible | ||||

| No | 41.9% | 45.0% | 17.0% | 22.0% |

| Yes | 58.1% | 55.0% | 83.0% | 78.0% |

| pSS diagnosis advice* | ||||

| Ruled out | 55.8% | 51.4% | 55.8% | 50.4% |

| Indeterminate | 9.7% | 12.8% | 11.9% | 16.8% |

| Ruled in | 34.4% | 35.7% | 32.2% | 32.8% |

*Diagnosis advice was given in regard with the typical pattern of pSS on images and not in patients with pSS.

pSS, primary Sjögren’s syndrome.

Reliability of SG ultrasound core items on acquisition imaging

PGs interobserver reliability was substantial for echogenicity and moderate for homogeneity, number and location and the size of the largest hypoechoic/anechoic area but fair for hyperechoic bands and slight for normal lymph nodes, number of abnormal lymph nodes, calcification and posterior border visibility (table 4). The advised diagnosis reliability of pSS was substantial (κ=0.66). SMGs interobserver reliability was fair for echogenicity, homogeneity and number and location of hypoechoic/anechoic areas. The results were slight for normal lymph nodes, calcifications and posterior border visibility. Advised diagnosis reliability was fair (κ=0.38).

Table 4.

Interobserver reliability of image acquisition: κ values for ultrasound items in the parotid and submandibular glands

| Item | PG | SMG |

| Echogenicity | ||

| Mean | 0.62 | 0.28 |

| Min–Max | 0.42–1.00 | 0.00–0.58 |

| Homogeneity | ||

| Mean | 0.52 | 0.26 |

| Min–Max | 0.16–0.87 | −0.05 to 0.87 |

| Hyperechoic bands | ||

| Mean | 0.38 | 0.19 |

| Min–Max | 0.11–0.64 | −0.09 to 0.39 |

| Number of hypoechoic/anechoic areas* | ||

| Mean | 0.54 | 0.27 |

| Min–Max | 0.34–0.88 | 0.09–0.51 |

| Size of the largest hypoechoic/anechoic area* | ||

| Mean | 0.41 | 0.17 |

| Min–Max | 0.29–0.79 | 0.04–0.41 |

| Location of hypoechoic/anechoic areas | ||

| Mean | 0.58 | 0.30 |

| Min–Max | 0.26–0.85 | 0.08–0.65 |

| Number of abnormal lymph nodes * | ||

| Mean | – | – |

| Min–Max | – | – |

| Normal lymph nodes | ||

| Mean | 0.13 | 0.01 |

| Min–Max | −0.07 to 0.28 | −0.09 to 0.26 |

| Calcifications | ||

| Mean | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Min–Max | −0.05 to 0.37 | −0.10 to 0.19 |

| Posterior border visibility | ||

| Mean | 0.02 | 0.15 |

| Min–Max | −0.16 to 0.18 | 0.00–0.48 |

| Diagnosis advice* | ||

| Mean | 0.66 | 0.38 |

| Min–Max | 0.30–0.97 | 0.12–0.65 |

Quantitative variables were then categorised as follows: number of hypoechoic/anechoic areas: None (0), 1–4 (1),≥5 (2); size of the largest area: None (0), ≤2 (1), >2 (2); abnormal lymph nodes: No (0), Yes (1).

*Diagnosis advice was given in regard with the typical pattern of pSS on images and not in patients with pSS.

PG, parotid gland; pSS, primary Sjögren’s syndrome; SMG, submandibular gland.

As shown in table 5, mean time duration of US ranged across observers from 11 to 27 min.

Table 5.

Time in minutes needed by each observer to perform salivary gland ultrasonography

| Observer | Min | Mean | Median | Max |

| A | 8 | 11.4 | 11 | 16 |

| B | 16 | 27 | 26 | 36 |

| C | 15 | 23 | 23 | 40 |

| D | 7 | 12 | 12 | 15 |

| E | 13 | 18.8 | 18 | 27 |

Discussion

Given the multitude of US-SG abnormalities in pSS, it has become a challenge to reach consensus on the definition and scoring of the most reliable US-SG abnormalities.19 We conducted this study to develop an international consensus about the definitions of echostructural abnormalities of SG in pSS and to evaluate the reliability of US in detecting them.

Homogeneity and echogenicity items showed substantial intraobserver reliability for both PGs and SMGs on static images. Whereas interobserver reliability of homogeneity was only substantial in PGs and moderate in SMGs and that of echogenicity was moderate in PGs and fair again in SMGs. Heterogeneity was defined as the presence of hypoechoic/anechoic areas with or without hyperechoic bands. For both glands, there is an abundance of hypoechoic/anechoic areas in pSS and their absence in normal individuals. However, the presence of highly vascularised fatty infiltration (ie, SMG echotexture vs PG echotexture) in SMGs may contribute to the difference observed in interobserver reliabilities of homogeneity item. These findings are consistent with those reported by Yoshiura et al.7

In line with previous studies,7 30 several core items showed low reliability in our study, namely, hyperechoic bands, calcifications and posterior border visibility for PGs and SMGs. Even though hyperechoic bands were defined by consensus, their reliable assessment in pSS remains challenging. Hyperechoic bands may develop in normal individuals due to advanced age or fibrosis of the SGs.

The static image inter-reliability of lymph nodes was moderate for the PGs but only slight for the SMGs, a finding that may reflect the usual absence of visible lymph nodes in the SMGs7 31 and their usual presence at specific locations in the PGs. Despite the definition established by consensus, calcifications were also difficult to assess. This finding may be ascribable to technical factors: when using static images, image quality cannot be optimised (for instance by changing the scanned area) and calcifications may be mistaken for hyperechoic bands. None of the nine published studies on the interobserver reliability of SG US in pSS7 10 15 20 25 30 32–35 evaluated calcifications. The posterior border was also difficult to assess, particularly for PGs, due to their anatomy and location in the retromandibular fossa.32 In our study, both PGs and SMGs inter-reliability and intrareliability were moderate to substantial for echogenicity and homogeneity (echostructure) due to the presence and distribution of hypoechoic/anechoic areas.

In the acquisition imaging study in 19 patients with pSS, homogeneity item showed moderate interobserver reliability for PGs and fair for SMGs. Whereas the results for echogenicity item of PG and SMG were substantial and fair, respectively. Our results contradict a single-centre study by Carotti et al,10 who reported better reliability for SMGs than for PGs. Nevertheless, moderate interobserver reliability for PG homogeneity and fair one for SMG were consistent with those of the literature.36–38

In our study, the experts’ advised diagnosis of pSS on static US images showed substantial interobserver and intraobserver reliability for PGs and intraobserver reliability for SMGs. Experts’ advised diagnosis of pSS on acquisition US showed substantial interobserver reliability for PGs and fair for SMGs. These results may be explained by the better echogenicity of PGs compared with SMGs. These findings can be ascribed to the development of a novel US atlas as a prerequisite to performing careful ultrasound evaluations by trained US experts of the SGs in patients with pSS.39

Our study had several limitations. First limitation was the small number of US experts and US acquisitions performed, which precluded a large-scale Delphi.36 40

However, pSS is not a so common disease41 42 and, consequently, few experts were trained in SG US at the time of the study. Second, different US machines were used for acquisition in pSS patients, that is, not all experts had prior training with the proposed machines. In addition, intraobserver reliability of US-SG core items was not evaluated due to the lack of time during our study. Another limitation was that the interobserver reliability of abnormal lymph nodes could not be evaluated yet can be explained by the rare nature of this US-SG item in pSS. Our study drawback is the fact that the images (both in static and in acquisition mode) were not characteristic of patients seen in consultation for a suspicion of pSS. The assessment of the abnormal echostructure (ie, typical pattern of an inhomogeneous gland with hypoechoic/anechoic areas in its parenchyma) of the images led to the ‘advised diagnosis’ by experts. We did not perform a diagnosis of pSS patients. The typical pattern is a conclusive characteristic of pSS but not present in all pSS patients.

In conclusion, this study is the first attempt to set forth a preliminary atlas of consensual US images and US-SG core items definitions. We assessed the reliability of US-SG core items of the images in regard with the typical pattern of an inhomogeneous gland with hypoechoic/anechoic areas in its parenchyma, (ie, not present in all pSS patients) to identify those most reliable. The reliability results of the pSS typical pattern on these images can be used carefully by US-SG trained experts and concomitantly with other classification criteria in diagnosis of pSS. US-PG interobserver reliability result (substantial) for echogenicity seems to be in line with that of advised diagnosis of pSS.

Larger sample US-SG acquisition studies using the same US machine by US-SG trained experts are warranted to validate our results and to further evaluate intraobserver reliability of US-SG items. Our US-SMG reliability results open the avenue to further search for other reliable and relevant abnormality definitions and scorings of SMG echotexture—to better distinguish them from neighbouring tissues.

Acknowledgments

We thank the French Society of Rheumatology (SFR) for funding this study. We also thank the French Sjögren’s patients who participated in the study. We are grateful to Florence Morvan, Céline Dolou and Floriane Masson (DRCI). We also thank the staff for their time and commitment to this work.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors have equally contributed to all steps of this study.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Brest University Hospital Ethics Committee approval: NCT 02358213.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All data are available in this original article and upon a request from corresponding author.

References

- 1.Fox RI. Sjögren's syndrome. Lancet 2005;366:321–31. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66990-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tzioufas AG, Vlachoyiannopoulos PG. Sjogren's syndrome: an update on clinical, basic and diagnostic therapeutic aspects. J Autoimmun 2012;39:1–3. 10.1016/j.jaut.2012.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haldorsen K, Moen K, Jacobsen H, et al. . Exocrine function in primary Sjögren syndrome: natural course and prognostic factors. Ann Rheum Dis 2008;67:949–54. 10.1136/ard.2007.074203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rubin P, Holt JF. Secretory sialography in diseases of the major salivary glands. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med 1957;77:575–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Späth M, Krüger K, Dresel S, et al. . Magnetic resonance imaging of the parotid gland in patients with Sjögren's syndrome. J Rheumatol 1991;18:1372–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vitali C, Monti P, Giuggioli C, et al. . Parotid sialography and lip biopsy in the evaluation of oral component in Sjögren's syndrome. Clin Exp Rheumatol 1989;7:131–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoshiura K, Yuasa K, Tabata O, et al. . Reliability of ultrasonography and sialography in the diagnosis of Sjögren's syndrome. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 1997;83:400–7. 10.1016/S1079-2104(97)90249-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ahuja AT, Metreweli C. Ultrasound features of Sjögren's syndrome. Australas Radiol 1996;40:10–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baldini C, Luciano N, Tarantini G, et al. . Salivary gland ultrasonography: a highly specific tool for the early diagnosis of primary Sjögren's syndrome. Arthritis Res Ther 2015;17:146. 10.1186/s13075-015-0657-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carotti M, Salaffi F, Manganelli P, et al. . Ultrasonography and colour doppler sonography of salivary glands in primary Sjögren's syndrome. Clin Rheumatol 2001;20:213–9. 10.1007/s100670170068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cornec D, Jousse-Joulin S, Pers JO, et al. . Contribution of salivary gland ultrasonography to the diagnosis of Sjögren's syndrome: toward new diagnostic criteria? Arthritis Rheum 2013;65:216–25. 10.1002/art.37698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hammenfors DS, Brun JG, Jonsson R, et al. . Diagnostic utility of major salivary gland ultrasonography in primary Sjögren's syndrome. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2015;33:56–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Milic V, Petrovic R, Boricic I, et al. . Ultrasonography of major salivary glands could be an alternative tool to sialoscintigraphy in the American-European classification criteria for primary Sjogren's syndrome. Rheumatology 2012;51:1081–5. 10.1093/rheumatology/ker431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Theander E, Mandl T. Primary Sjögren's syndrome: diagnostic and prognostic value of salivary gland ultrasonography using a simplified scoring system. Arthritis Care Res 2014;66:1102–7. 10.1002/acr.22264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wernicke D, Hess H, Gromnica-Ihle E, et al. . Ultrasonography of salivary glands -- a highly specific imaging procedure for diagnosis of Sjögren's syndrome. J Rheumatol 2008;35:285–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Devauchelle-Pensec V, Cagnard N, Pers JO, et al. . Gene expression profile in the salivary glands of primary Sjögren's syndrome patients before and after treatment with rituximab. Arthritis Rheum 2010;62:2262–71. 10.1002/art.27509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jousse-Joulin S, Devauchelle-Pensec V, Cornec D, et al. . Brief Report: Ultrasonographic Assessment of Salivary Gland Response to Rituximab in Primary Sjögren's Syndrome. Arthritis Rheumatol 2015;67:1623–8. 10.1002/art.39088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tugwell P, Boers M, D'Agostino MA, et al. . Updating the OMERACT filter: implications of filter 2.0 to select outcome instruments through assessment of "truth": content, face, and construct validity. J Rheumatol 2014;41:1000–4. 10.3899/jrheum.131310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jousse-Joulin S, Milic V, Jonsson MV, et al. . US-pSS Study Group. Is salivary gland ultrasonography a useful tool in Sjögren's syndrome? A systematic review. Rheumatology 2016;55:789–800. 10.1093/rheumatology/kev385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ariji Y, Ohki M, Eguchi K, et al. . Texture analysis of sonographic features of the parotid gland in Sjögren's syndrome. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1996;166:935–41. 10.2214/ajr.166.4.8610577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.De Vita S, Lorenzon G, Rossi G, et al. . Salivary gland echography in primary and secondary Sjögren's syndrome. Clin Exp Rheumatol 1992;10:351–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hocevar A, Ambrozic A, Rozman B, et al. . Ultrasonographic changes of major salivary glands in primary Sjogren's syndrome. Diagnostic value of a novel scoring system. Rheumatology 2005;44:768–72. 10.1093/rheumatology/keh588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kawamura H, Taniguchi N, Itoh K, et al. . Salivary gland echography in patients with Sjögren's syndrome. Arthritis Rheum 1990;33:505–10. 10.1002/art.1780330407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Milic VD, Petrovic RR, Boricic IV, et al. . Major salivary gland sonography in Sjögren's syndrome: diagnostic value of a novel ultrasonography score (0-12) for parenchymal inhomogeneity. Scand J Rheumatol 2010;39:160–6. 10.3109/03009740903270623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Salaffi F, Carotti M, Iagnocco A, et al. . Ultrasonography of salivary glands in primary Sjögren's syndrome: a comparison with contrast sialography and scintigraphy. Rheumatology 2008;47:1244–9. 10.1093/rheumatology/ken222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vitali C, Carotti M, Salaffi F. Is it the time to adopt salivary gland ultrasonography as an alternative diagnostic tool for the classification of patients with Sjögren's syndrome? Comment on the article by Cornec et al. Arthritis Rheum 2013;65:1950. 10.1002/art.37945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cohen J. Weighted kappa: nominal scale agreement with provision for scaled disagreement or partial credit. Psychol Bull 1968;70:213–20. 10.1037/h0026256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hallgren KA. Computing Inter-Rater Reliability for Observational Data: An Overview and Tutorial. Tutor Quant Methods Psychol 2012;8:23–34. 10.20982/tqmp.08.1.p023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977;33:159–74. 10.2307/2529310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hocevar A, Rainer S, Rozman B, et al. . Ultrasonographic changes of major salivary glands in primary Sjögren's syndrome. Evaluation of a novel scoring system. Eur J Radiol 2007;63:379–83. 10.1016/j.ejrad.2007.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bialek EJ, Jakubowski W, Zajkowski P, et al. . US of the major salivary glands: anatomy and spatial relationships, pathologic conditions, and pitfalls. Radiographics 2006;26:745–63. 10.1148/rg.263055024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Klem C. Head and neck anatomy and ultrasound correlation. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 2010;43:1161–9. 10.1016/j.otc.2010.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Niemelä RK, Takalo R, Pääkkö E, et al. . Ultrasonography of salivary glands in primary Sjogren's syndrome. A comparison with magnetic resonance imaging and magnetic resonance sialography of parotid glands. Rheumatology 2004;43:875–9. 10.1093/rheumatology/keh187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Salaffi F, Argalia G, Carotti M, et al. . Salivary gland ultrasonography in the evaluation of primary Sjögren's syndrome. Comparison with minor salivary gland biopsy. J Rheumatol 2000;27:1229–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takagi Y, Kimura Y, Nakamura H, et al. . Salivary gland ultrasonography: can it be an alternative to sialography as an imaging modality for Sjogren's syndrome? Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:1321–4. 10.1136/ard.2009.123836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.D'agostino MA, Aegerter P, Jousse-Joulin S, et al. . How to evaluate and improve the reliability of power Doppler ultrasonography for assessing enthesitis in spondylarthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2009;61:61–9. 10.1002/art.24369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jousse-Joulin S, d'Agostino MA, Marhadour T, et al. . Reproducibility of joint swelling assessment by sonography in patients with long-lasting rheumatoid arthritis (SEA-Repro study part II). J Rheumatol 2010;37:938–45. 10.3899/jrheum.090881 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Micu MC, Serra S, Fodor D, et al. . Inter-observer reliability of ultrasound detection of tendon abnormalities at the wrist and ankle in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology 2011;50:1120–4. 10.1093/rheumatology/keq441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hammer HB, Bolton-King P, Bakkeheim V, et al. . Examination of intra and interrater reliability with a new ultrasonographic reference atlas for scoring of synovitis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:1995–8. 10.1136/ard.2011.152926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gutierrez M, Filippucci E, Ruta S, et al. . Inter-observer reliability of high-resolution ultrasonography in the assessment of bone erosions in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: experience of an intensive dedicated training programme. Rheumatology 2011;50:373–80. 10.1093/rheumatology/keq320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cornec D, Chiche L. Is primary Sjögren's syndrome an orphan disease? A critical appraisal of prevalence studies in Europe. Ann Rheum Dis 2015;74:e25. 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-206860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maldini C, Seror R, Fain O, et al. . Epidemiology of Primary Sjögren's Syndrome in a French Multiracial/Multiethnic Area. Arthritis Care Res 2014;66:454–63. 10.1002/acr.22115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

rmdopen-2016-000364supp001.docx (21.8KB, docx)

rmdopen-2016-000364supp002.pdf (1.9MB, pdf)