Abstract

Background and Purpose

Hypertension is the major risk factor for stroke. Recent work unveiled that hypertension is associated with chronic neuroinflammation; microglia are the major players in neuroinflammation and the activated microglia elevate sympathetic nerve activity and blood pressure (BP). This study is to understand how brain homeostasis is kept from hypertensive disturbance and microglial activation at the onset of hypertension.

Methods

Hypertension was induced by subcutaneous delivery of angiotensin II and BP was monitored in conscious animals. Microglial activity was analyzed by flow cytometry and immunohistochemistry. Antibody, pharmacological chemical and recombinant cytokine were administered to the brain through intracerebroventricular (ICV) infusion. Microglial depletion was performed by ICV delivering diphtheria toxin to CD11b-DTR mice. Gene expression profile in sympathetic controlling nucleus was analyzed by customized qRT-PCR array.

Results

TGFβ is constitutively expressed in the brains of normotensive mice. Removal of TGFβ or blocking its signaling before hypertension induction accelerated hypertension progression, while supplementation of TGFβ1 substantially suppressed neuroinflammation, kidney norepinephrine level, and BP. By means of microglial depletion and adoptive transfer, we showed that the effects of TGFβ on hypertension are mediated through microglia. In contrast to the activated microglia in established hypertension, the resting microglia are immunosuppressive and important in maintaining neural homeostasis at the onset of hypertension. Further, we profiled the signature molecules of neuroinflammation and neuroplasticity associated with hypertension and TGFβ by qRT-PCR array.

Conclusions

Our results identify that TGFβ-modulated microglia are critical to keeping brain homeostasis responding to hypertensive disturbance.

Keywords: TGFβ, Microglia, Hypertension, Neuroinflammation, Neural plasticity

Introduction

Substantial evidence accumulated in the past decade indicates that hypertension is associated with both systemic and neural inflammation1–3. Consistent with this notion, immunosuppression reduces blood pressure (BP) in various hypertensive models4, 5. Another feature of hypertension is that it is always accompanied with increased sympathetic nerve activity (SNA), especially elevated renal SNA3. Therefore, clinical trials of renal sympathetic nerves denervation via surgical sympathoectomy have been performed for the treatment of resistant hypertension6. Inhibition of central immune system can effectively attenuate BP and sympathetic outflow in hypertensive animal models7–9. These results suggest that central immune system is involved in the regulation of sympathetic outflow and BP. Our recent studies further show that in hypertension, microglia, the principal immune cells of the central nervous system (CNS), turn pro-inflammatory and participate in neuroinflammation and sympathetic nerve over-activation8, 10. Microglial activation in established hypertension is detrimental to neural homeostasis and exacerbates the disease, while depletion of activated microglia alleviates hypertension11.

Microglia are a distinct cell population in the brain parenchyma, derived from primitive myeloid progenitors on embryonic day 8.512. Adult microglia are self-maintained with the dependence of macrophage-colony-stimulating factor receptor CSF1R. Their phenotype is determined by transcription factors like PU.1, IRF8 and Sall113, 14. Recent studies unveiled that microglia participate in shaping neuronal behavior, such as modulating spine formation and synaptic transmission under both physiological and diseases conditions15, 16. These suggest that microglia are proactively involved in shaping neural function. A unique feature of microglia comparing to other brain cells is that their activity can be primed and altered according to the surrounding environment. In normal conditions, microglia function as surveilling cells to detect pathogens and maintain CNS homeostasis17, 18. With the progression of aging and neurodegeneration, microglia are induced to an active mode, and result in morphological, gene profile and polarity changes19. However, the mechanism of microglia activation in the progress of hypertension especially at the onset stage is currently unknown. A hint from recent study shows that inhibition of transforming growth factor (TGF) β signaling promote microglial activation13.

TGFβ family in mammals includes three highly homologous members, TGFβ1, 2 and 3, amongst which TGFβ1 is the most abundant isoform and is ubiquitously expressed in various cell types and tissues20. The actions of TGFβ family members are mainly mediated via binding to the transmembrane serine/threonine kinase receptors I and II, followed by phosphorylation of the transcription factor SMAD protein subunits 2 and 320. In the CNS, TGFβ is produced by most cell types including neurons, astrocytes and microglia, and plays a pivotal role in brain development and keeping its homeostasis18. Moreover, TGFβ is a major determinant of adult neurogenesis21. Loss of TGFβ results in increased neuronal death and microgliosis in acute or chronic brain injuries22. Intriguingly, recent studies reported that TGFβ is required for microglial survival and proliferation, and TGFβ receptor I is exclusively expressed on microglia under normal conditions18. Specific deletion of the TGFβ receptor (TGFβ-R) resulted in rapid conversion of microglia towards an inflammatory phenotype13, which implies that central TGFβ is a determinant in controlling microglial phenotype fate. Consistent with this notion, intracranial administration of TGFβ modulates microglial phenotype and promotes recovery from hemorrhagic stroke23. Collecting above findings that neuroinflammation is highly associated with hypertension1, 24, microglia is the cellular mediator of neuroinflammation and hypertension11 and central TGFβ play a vital role in keeping microglial homeostasis13, we hypothesize that central TGFβ signaling contributes to central BP regulation.

In this work, we investigated the role of central TGFβ in BP regulation and found that brain TGFβ has a suppression effect on AngII-induced hypertension. Then we verified the benefit of TGFβ1 in reducing neural overreaction and microglial inflammatory cytokine expression during hypertension both in vitro and in vivo. Using microglial depletion and adoptive transfer strategies, we demonstrated that the effect of TGFβ on BP modulation is via microglia. Finally, we identified a molecular signature profile associated with hypertension and TGFβ.

Methods

Animals

All animal procedures were approved by Cedars-Sinai Medical Center and Zhejiang University IACUC in accordance with the NIH Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Male adult (8–10 weeks-old) C57BL/6J (WT), Tg(ITGAm-DTR/EGFP)34Lan (CD11b-DTR) and B6.129P-Cx3cr1tm1Litt/J (CX3CR1-GFP) mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratories and bred in Cedars Sinai Medical Center and Zhejiang University.

Osmotic pump implantation

Mice were anesthetized by inhalation of 2–3% isoflurane/O2 mixture. For ICV cannulation, the mouse was positioned in a stereotaxic apparatus. An infusion cannula was implanted into the left cerebroventricle. A 2nd two-week osmotic minipump infusing 500ng/kg/min AngII was implanted in the same animal subcutaneously 3 or 7 days later.

Blood pressure recording

The BP data of the experiments of TGFβ ICV infusion and microglial depletion were collected by telemetry transducer; the BP data of TGFβ neutralizing and signaling blocking were collected by Tailcuff system; The BP data of microglial transfer were collected with acute BP recording.

Adoptive transferring of primed cells

After 24-hour incubation with saline or TGFβ (4 ng/ml), mouse C8-B4 microglial cells or astrocytes were harvested and adoptively transferred into the recipient WT mouse brain via ICV infusion. Each mouse received 5×105 cells via a pump-driven Hamilton micro-syringe accordingly to the following coordinates: 0.5 mm posterior to Bregma; 1 mm lateral to midline; and 2 mm below the dura.

Real-time RT-PCR

The brain tissues from hypothalamus were dissected for RNA purification. The expression profiles of targeting genes were analyzed by customized RT2 Profiler Array System (Qiagen, CAPM13540) following the supplier’s instructions. All the assays were performed on a StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems).

Flow Cytometry

Brain cells were isolated from the mouse brains by mechanical and enzymatic dissociation; and the microglia were purified and enriched by Percoll gradient centrifugation (37% and 70%). For the cellular staining, the following antibodies were used: MHC II-APC, TNFα-PerCP-Cy5.5, CD11b-APC-Cy7 and CD45-FITC. All the antibodies were purchased from either eBioscience, BioLegend or Pharmingen. Afterward, the samples were analyzed on a Beckman Coulter CyAn ADP and data were analyzed by FlowJo software.

Data analysis

Data are summarized as mean ± S.E.M. Statistical analysis was performed with GraphPad Prism version 6.

Details of all experimental protocols are presented in the Supplemental Methods section in the Online Supplement. Please see http://stroke.ahajournals.org.

Results

TGFβ regulates the development of hypertension

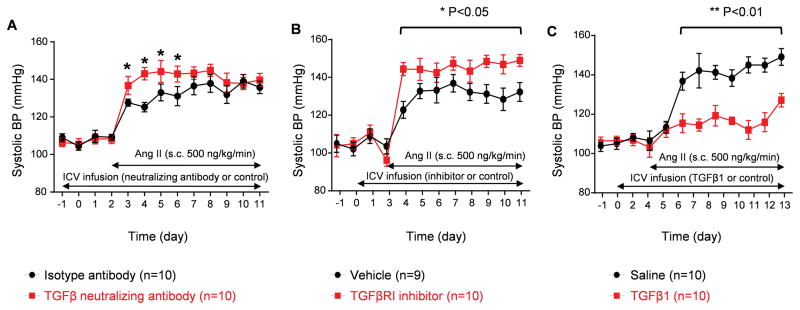

Previous studies reported that there is increased TGFβ1 in both plasma and monocytic cells of hypertensive patients compared to normal controls25, 26. To investigate the role of intracranial TGFβ in hypertension, we first measured the level of TGFβ1 in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus (PVN), which is central in SNA regulation. We observed that TGFβ1 is constitutively expressed in normotensive mice and slightly but significantly increased in angiotensin (Ang) II induced hypertensive mice (Supplemental Figure I). To understand whether TGFβ is involved in BP regulation in the CNS, we first adopted a depletion strategy by ICV infusion of an anti-(pan)TGFβ neutralizing antibody. Mice were treated with TGF neutralizing antibody via 2-week ICV minipumps to deplete brain TGFβ. Preliminary results showed that 50 μg/day by ICV minipump produced a maximal effect and could decrease brain TGFβ by 27% (Supplemental Figure II), and this dose did not change kidney TGFβ level or baseline BP. Three days later, mice were induced hypertension by subcutaneously infusion of Ang II (500 ng/kg/min) via minipumps; BP were monitored for the following 9 days (Figure 1A). The result showed that the mice receiving TGFβ neutralizing antibody had significantly elevated BP on the first 4 days after Ang II treatment compared to the mice receiving an isotype antibody (Figure 1A). Afterwards, there was no difference between these two groups, which was probably due to an incomplete depletion of TGFβ. To further investigate the role of central TGFβ in BP regulation, we ICV delivered a selective TGFβRI kinase inhibitor SB52533427 prior to hypertension induction. The specificity of SB525334 in abrogating the effect of TGFβ was validated in C8-B4 microglial cell line (Supplemental Figure III). Blocking TGFβ signaling caused a continuously greater BP response to Ang II than that of the ICV vehicle-treated group (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. Brain TGFβ signaling is important in regulating BP in hypertension.

Mice were treated with ICV infusion of TGFβ neutralizing antibody (A), TGFβRI inhibitor SB525334 (B) or TGFβ1 (C); hypertension was induced in each group by Ang II infusion. Systolic BP was measured by tailcuff in (A) and (B) and by telemetry transducer in (C). * P<0.05, ** P<0.01.

Above findings suggest that brain TGFβ could be an important regulator of BP. We next examined whether supplementing TGFβ could suppress BP increase at the onset of hypertension. Mice received ICV infusion of recombinant TGFβ1 (50 ng/day) or saline 3 days prior to Ang II treatment (Figure 1C). Intracranial treatment with TGFβ1 significantly retarded the BP response to Ang II infusion, evidenced by 20 mmHg lower than that of the mice receiving saline (Figure 1C).

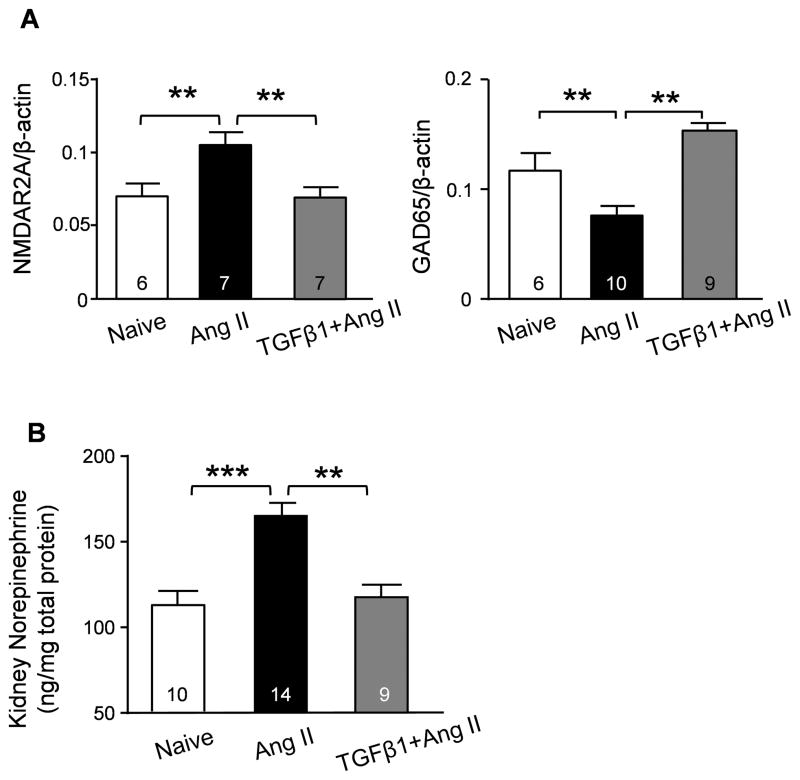

At the end of the TGFβ1 supplementation experiment, we examined the expression of N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) receptor and glutamate decarboxylase Gad65, both of which are important for neurogenic hypertension28, 29. Moreover, we examined the renal norepinephrine (NE) level, which is an indicator of SNA30. Ang II-induced hypertension caused a significant upregulation of the NMDA receptor subunit NMDAR2A, a down-regulation of Gad65 in the PVN and brain stem, and a significant increase in renal NE, the latter suggesting neuronal over-excitation (Figure 2A–B). Consistent with the BP measurements, ICV TGFβ1 treatment maintained NMDAR2A, Gad65 (Figure 2A) and NE (Figure 2B) at normal levels despite Ang II treatment. Taken together, these data suggest that TGFβ in the CNS can suppress central over activity in hypertension.

Figure 2. Effects of brain TGFβ1 treatment on neural activity and humoral expression.

(A) Summary semi-quantification of Western blots of NMDAR2A and GAD65 in hypothalamus and brain stem tissues derived from naïve, Ang II- and TGFβ1+Ang II-treated mice. (B) Norepinephrine level was examined by ELISA in kidney lysates from naïve, Ang II- and TGFβ1+Ang II-treated mice. ** P<0.01; *** P<0.001.

TGFβ regulates microglial activation in hypertension

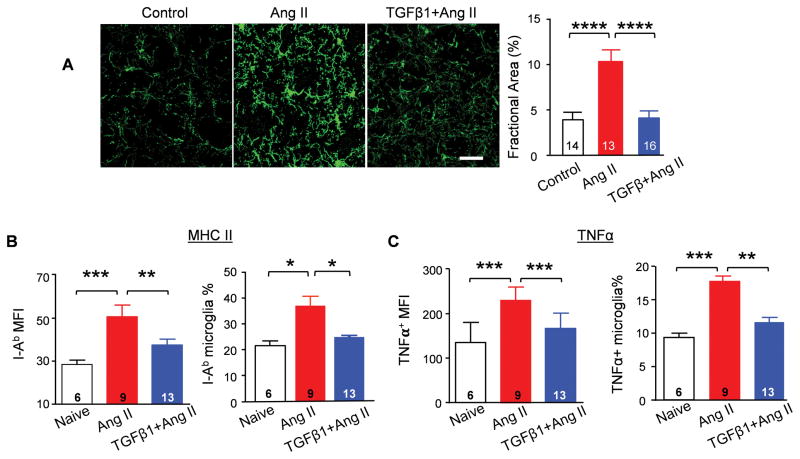

Our previous work showed that activated microglia play a key role in neuroinflammation, which aggravates hypertension11. Considering that TGFβ is critical in determining microglial phenotype13 and TGFβRI is exclusively expressed in microglia in the CNS18, we postulated that TGFβ exerts direct effects on microglia in hypertension. Thus, at the end of experiment described in Figure 1C, the brain tissues of each group were collected and performed immunohistochemistry staining. Microglia were detected by marker Iba1. In contrast to the ramified appearance of naïve microglia, microglia from hypertensive mice displayed soma enlargement and process retraction (Figure 3A). Moreover, there is a greater density of microglia in the PVN of the hypertensive mice, as quantified by fractional area analysis8. These changes indicate microgliosis, a characteristic of microglial activation8, 11. In contrast, we observed that TGFβ1 pre-treatment prevented microgliosis in the PVN after hypertension induction (Figure 3A).

Figure 3. TGFβ1 suppresses microglial activation.

(A) Representative immunostaining of microglia with anti-Iba1 antibody in the PVN. Calibration bar equals to 20 μm. Fractional area of Iba-1 staining was analyzed in each group. **** P<0.0001. Expression of MHC class II subtype I-Ab (B) and TNFα (C) in CD11b+CD45low-microglia was evaluated by flow cytometry analysis. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

Upregulation of MHC class II and of TNFα are hallmarks of activation of microglia11. We next examined both markers on microglia dissociated from naïve, hypertensive and hypertensive mice administered with TGFβ1 via the ICV route. Flow cytometry analysis revealed that MHC class II expression as well as TNFα production were significantly increased in microglia of mice infused with Ang II. However, in the TGFβ1 pretreatment group, the expression of MHC class II and TNFα are maintained at normal level (Figures 3B–C), which indicated that TGFβ suppresses the upregulation of MHC class II and TNFα induced by hypertension. Thus, we conclude that TGFβ negatively regulates activation of microglia during hypertension.

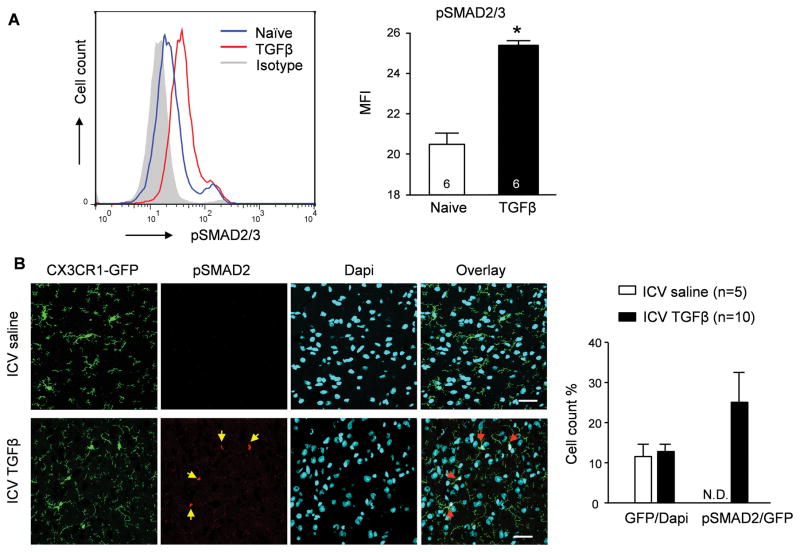

TGFβ regulates gene expression via the phosphorylation of SMAD2 and SMAD331. We thus examined SMAD2/3 phosphorylation (pSMAD2/3) in C8-B4 microglial cells and found that pSMAD2/3 was significantly elevated following TGFβ1 (20 ng/ml for 30 min) priming (Figure 4A). In support of this notion, there was 25% of microglia expressing pSMAD2 30 min after ICV injection of TGFβ1 (20 ng in 1 μl) into CX3CR1-GFP mice, examined by immunohistochemistry (Figure 4B). Of note, other non-microglia (GFP−) cells barely display phosphorylated SMAD2, confirming that microglia are the major cell type mediating the biological activity of TGFβ in the CNS.

Figure 4. TGFβ1 promotes SMAD2/3 phosphorylation in microglia.

(A) Flow cytometry analysis of SMAD2/3 phosphorylation in naïve and TGFβ1-treated C8-B4 microglial cell line. * P<0.05. A representative histogram as well as the mean fluorescent intensity (MFI) is shown. (B) Co-localization of pSMAD2, GFP+ and Dapi+ in the PVN obtained from a CX3CR1-GFP transgenic mouse 30 minutes after ICV injection of TGFβ1 or saline. N.D. non-detectable. Calibration bar indicates 20 μm.

Recent work revealed that TGFβ1 is essential in keeping microglia in a quiescent state; disruption of TGFβ signaling promotes microglia towards proinflammatory activation13. To investigate the suppressive effects of TGFβ, murine naïve C8-B4 microglia were pre-treated with or without TGFβ1 (4 ng/ml) for 18 hours followed by challenge with either prorenin (50 nM), a hypertensive factor, or lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (0.1 ng/ml) for another 6 hours. Consistently, pre-treatment with TGFβ1 significantly attenuated prorenin- or LPS-elicited TNFα expression in C8-B4 cells (Supplemental Figure IV).

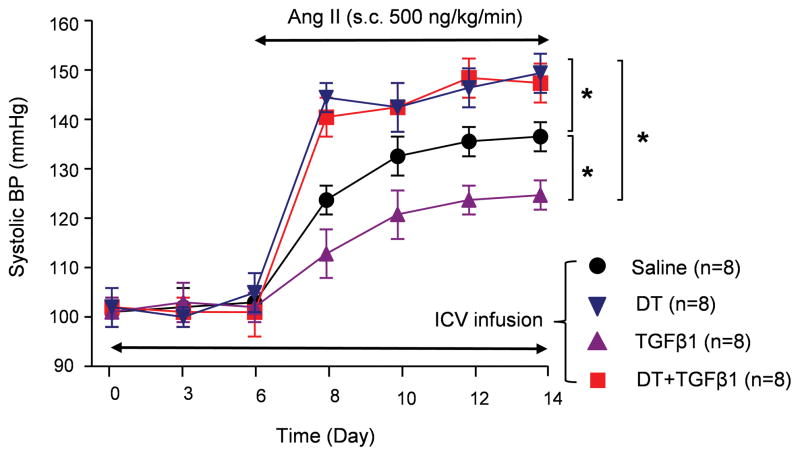

Central TGFβ modulates BP through microglia

Previously, we successfully devised a microglial depletion strategy by ICV infusion of diphtheria toxin (DT) to CD11b-DTR mice11. We thus investigated whether microglial depletion would remove the suppressive effect of TGFβ on BP in hypertension. CD11b-DTR mice were delivered via the ICV route with TGFβ1 (50 ng/day) mixed with or without DT (800 pg/g BW/day). Six days later, mice were induced hypertension by Ang II infusion. Compared to the saline control group, ICV TGFβ1 treatment retarded the BP increase in experimental hypertension. However, in TGFβ1+DT group, microglia depletion not only completely abrogated the suppressive effect of TGFβ1 on the BP increase, but further significantly elevated the BP compared to the saline controls (Figure 5). Of note, ICV infusion of TGFβ1 with or without DT did not change the baseline BP (Figure 5). These data are intriguing since they not only indicate that microglia mediate the effect of TGFβ in hypertension, but also imply that microglia themselves are important in maintaining brain homeostasis on the initiation stage of hypertension. To further understand the role of microglia in hypertension, we monitored BP in a 4th group, in which microglia were depleted by DT infusion prior to hypertension induction. Pre-depletion of microglia resulted in a more acute BP response than that of the ICV saline control group; and the BP curve was coincident with that of the DT+TGFβ1 co-treated group (Figure 5). Taken together, our study indicated that microglia under different status shows distinct even opposite function in hypertension; and TGFβ drives microglia towards an immunosuppressive phenotype, suppressing BP increase.

Figure 5. Microglia mediate the effects of TGFβ1 on BP control.

Systolic BP was measured by telemetry transducer in Ang II-infused CD11b-DTR mice which were treated ICV with either saline, DT, TGFβ1 or DT + TGFβ1. * P<0.05.

To further confirm that microglia could mediate the effects of TGFβ on BP regulation, we adoptively transferred C8B4 microglia with or without in vitro TGFβ1 priming into the cerebroventricle of naïve mice. Twenty-four hours after their ICV transfer, C8B4 cells tagged with CFSE were distributed in the recipient brains, mostly localized around the 3rd ventricles where PVN is in vicinity (Supplemental Figure V). There was no difference in baseline BP and heart rate between the groups (Supplemental Table). A single ICV injection of Ang II (50 ng), elicited an acute pressor response in both groups (Supplemental Figure VI). However, the magnitude and area under the response curve elicited by Ang II were significantly attenuated in mice transferred with TGFβ1-primed microglia compared to the ones received naïve microglia. This difference was not observed in mice receiving Medium- or TGFβ1-primed astrocytes.

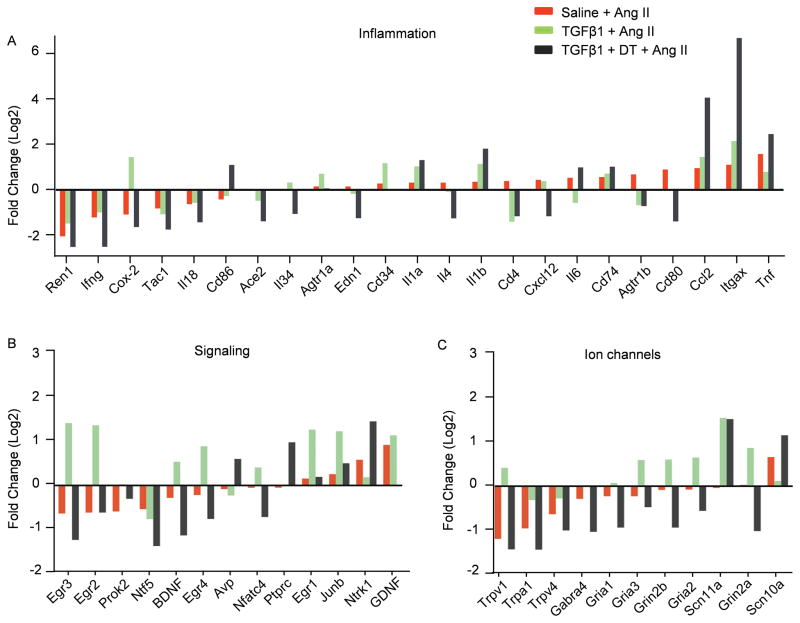

Identification of neuroplasticity and neuroinflammation signatures associated with hypertension and TGFβ

To identify the neural molecular signatures associated with hypertension and TGFβ, we performed qRT-PCR arrays (Qiagen # CAPM13540) of PVN and brain stem lysates isolated from naive mice and mice made hypertensive by Ang II for 10 days. Moreover, we also examined the samples from mice pretreated via the ICV route with TGFβ1 followed by 11-day Ang II treatment in the presence (TGFβ1+Ang II) or absence of microglia (TGFβ1+DT+Ang II). These gene targets were selected based on their widely reported roles in synaptic alteration, pain or neural injury. We compared the identified molecular signature of genes whose expression changed by more than twofold across all four groups, and pooled the genes into three categories: inflammatory factors (Figure 6A), signaling regulators (Figure 6B) and ion channels (Figure 6C).

Figure 6. Molecular signature of neuroplasticity and neuroinflammation associated with hypertension and TGFβ.

qRT-PCR array of PVN and brain stem lysates isolated from 4 groups of mice. Genes whose expression changed by more than twofold across all four populations are grouped into three categories: (A) inflammatory factors, (B) signaling regulators and (C) ion channels. The genes were arranged from low to high according to the fold changes in Ang II-treated mice compared with naïve controls (red column). Each column indicates the log2 value of the fold change when compared to the data from naive mice. The means of three independent experiments are shown.

Previous studies revealed that Egr1, Egr3, JunB, CD34 and Cox-2 are downstream genes induced by TGFβ132–36. Consistently, in our qRT-PCR array analysis, these genes were all upregulated in the TGFβ1-treated brains (Figure 6A–B), which verifies the robustness of this assay. This is consistent with reports that TGFβ is required for microglia proliferation as the stem cell antigen CD34 is expressed in proliferating resident microglia18, and our assay shows that upregulation of the CD34 by TGFβ1 is intrinsic to microglia since microglia depletion completely abrogated the increase (Figure 6A). Moreover, our results confirm that microglia are the major source of the neurohumoral BDNF (Figure 6B), consistent with the finding that microglia-derived BDNF promotes neuron synapse formation15.

Ion channel genes are mainly expressed by neurons in the CNS. The assay reveals three distinctive patterns of ion channel expression in the brains from mice made hypertensive by Ang II when compared to the normotensive brains (Figure 6C). Hypertension is associated with downregulation of the non-selective cation channels (Trpv1, Trpv4 and Trpa1), upregulation of the voltage-gated sodium channel Scn10a and no changes in the glutamate receptor (NMDA receptor subunit Grin2b and AMPA receptor subunits Gria1 and Gria2). However, ICV TGFβ1 treatment not only substantially offset the effects of Ang II on Trpv1, Trpv4, Trpa1 and Scn10a, but also upregulated glutamate receptor Grin2b and Gria2. Depletion of microglia completely abolished these effects of TGFβ1, again indicating that microglia mediate the effects of TGFβ in the brain.

Other changes in genes associated with neuroplasticity include the neurotrophic receptor Ntrk1, the signaling of which promotes sympathetic neuron activity37 (Figure 6B). Ntrk1 was upregulated by Ang II treatment as well as by depletion of resting microglia; in the presence of microglia, TGFβ1 suppressed its increase induced by Ang II. Amongst the transcription factors, Egr1-4, JunB and Nfatc4 were considerably upregulated by TGFβ1, and our data indicate that these processes occurred in microglia because deprivation of these cells normalized or even decreased expression of Egr1-4, JunB and Nfatc4 (Figure 6B).

It was recently reported that macrophage-derived Cox-2, in the periphery, is important for antagonizing salt-sensitive hypertension38. Our array data show that TGFβ1 treatment prior to Ang II raised Cox-2 expression by 5 fold, and microglia depletion completely abrogated the effects of TGFβ1 on Cox-2 (Figure 6A). To confirm these results, we examined Cox-2 expression in the PVN and brain stem of naïve, Ang II-hypertensive and Ang II+TGFβ1-treated mice. RT-PCR confirmed that TGFβ1 treatment significantly increased Cox2 mRNA levels (Supplemental Figure VII-A); further, we demonstrated that TGFβ1 can dramatically elevate Cox-2 expression in primary microglia (Supplemental Figure VII-B), suggesting that in the CNS, the microglia-derived Cox-2 may also play a critical role in antagonizing the BP induced changes and that TGFβ1 induces its expression.

Discussion

Mice lacking TGFβ die of multi-organ inflammation early in life, highlighting a crucial role for TGFβ in dampening self-harmful inflammatory responses and maintaining tissue homeostasis39. Hypertension is associated with neuroinflammation1, 2, 24. This study, as a continuum of our previous studies, sought to understand how central physiological regulation and neural immune response are balanced in the setting of hypertension.

Using multifaceted approaches, we demonstrated that TGFβ is a negative regulator of neuroinflammation and of hypertension. These data strongly support the hypothesis that “resting” microglia are neuroprotective from hypertensive disturbance at the onset of hypertension and maintain normal blood pressure. Depletion of homeostatic microglia result in CNS more susceptible to hypertensive stimulation and BP further elevated, which is different from our previous study showing that the microglia were depleted after hypertension was established. Therefore, removal of activated microglia alleviated neuroinflammation and BP. Moreover, we found that in the resting state, TGFβ is constitutively expressed in the CNS, and consistent with others’ reports, we show that microglia are the major responsive cells to TGFβ in the CNS. Intriguingly, a recent study revealed that TGFβ is crucial for microglia survival and proliferation18, which indicates that similar to macrophages in the periphery, immunosuppressive microglia are more populous than their pro-inflammatory counterparts in the CNS in normal basal condition. Thus, in contrast to the promoting role of microglia in established hypertension, resting microglia exhibit a down-regulated immune phenotype adapted to the immune-suppressive environment of the CNS. Consistent with our findings, very recent work by Taylor et al. showed that ICV TGFβ treatment induces microglial towards an anti-inflammatory phenotype, and TGFβ plasma levels positively correlate patient recovery after hemorrhagic stroke 23.

Our study suggests that TGFβ and its signaling could be potential targets in managing neurogenic hypertension. Thus, understanding the mechanisms of how TGFβ and resting microglia regulate neuronal activity appears crucial. For this purpose, we constructed an RT-PCR array to measure genes associated with neuroplasticity and neuroinflammation at the initiation stage of hypertension. Not surprisingly, hypertension is accompanied by upregulation of an array of pro-inflammatory cytokines, e.g. Ccl2, TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1α and IL-1β (Figure 6A). A striking finding of this assay is that resting microglia play a critical role in containing neuroinflammation since pre-depletion of microglia exacerbated inflammation, suggesting that it is not microglia but other (unknown) brain cells that initiate neuroinflammation in hypertension. It is conceivable that in such a pro-inflammatory environment, microglia are “educated” to become fully activated later on. Thus, identifying the inflammation initiator may provide pivotal insights into the development of neurogenic hypertension. In addition, the array results reveals for the first time three distinctive patterns of ion channel expression changes in the Ang II-induced hypertensive brain. Most importantly, ICV TGFβ1 treatment substantially offset the effects of Ang II on the expression of these ion channels, and depletion of microglia completely abolished these effects of TGFβ1. The up- or down-regulation of these ion channels correlates with the BP data and are bone fide neuron activation signatures associated with hypertension. Interestingly, our screen suggests that in the CNS, the microglia-derived Cox-2 may relay the effects of TGFβ in antagonizing BP changes in hypertension.

Taken together, this study unveils a novel immune-regulatory pathway in the development of neurogenic hypertension.

Summary

In this study, we identified that TGFβ tunes microglia towards an immune-suppressor phenotype under resting conditions, which resist the blood pressure increase during the initiation stage of hypertension. By comparing gene profiles related to neuroinflammation and neural plasticity in mouse brain tissue, we identified a plethora of molecules associated with hypertension, TGFβ and microglia. These findings suggest that surveillant microglia are tightly regulated by TGFβ, which are critical in maintaining the homeostasis of the CNS and blood pressure.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Source of Funding

This work was supported by Chinese Fundamental Research Fund for the Central Universities (2016XZZ002-03 to P.S.), American Heart Association grant 11SDG6770006 (to P.S.), National Natural Science Foundation of China 31270950 and 81670378 (to X.Z.S.), NIH grants P01 HL129941 (to K.E.B.), HL-14388 (to A.K.J) and R01 NS075930 (to P.L.) and China State Scholarship Fund 201306260029 (to Y.L.).

Footnotes

Disclosures

None

References

- 1.Shi P, Raizada MK, Sumners C. Brain cytokines as neuromodulators in cardiovascular control. Clinical and experimental pharmacology & physiology. 2010;37:e52–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2009.05234.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marvar PJ, Lob H, Vinh A, Zarreen F, Harrison DG. The central nervous system and inflammation in hypertension. Current opinion in pharmacology. 2011;11:156–161. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DiBona GF, Kopp UC. Neural control of renal function. Physiological reviews. 1997;77:75–197. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1997.77.1.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guzik TJ, Hoch NE, Brown KA, McCann LA, Rahman A, Dikalov S, et al. Role of the t cell in the genesis of angiotensin ii induced hypertension and vascular dysfunction. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2007;204:2449–2460. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rodriguez-Iturbe B, Pons H, Quiroz Y, Gordon K, Rincon J, Chavez M, et al. Mycophenolate mofetil prevents salt-sensitive hypertension resulting from angiotensin ii exposure. Kidney international. 2001;59:2222–2232. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00737.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Symplicity HTNI. Catheter-based renal sympathetic denervation for resistant hypertension: Durability of blood pressure reduction out to 24 months. Hypertension. 2011;57:911–917. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.163014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Masson GS, Nair AR, Silva Soares PP, Michelini LC, Francis J. Aerobic training normalizes autonomic dysfunction, hmgb1 content, microglia activation and inflammation in hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus of shr. American journal of physiology. Heart and circulatory physiology. 2015;309:H1115–1122. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00349.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shi P, Diez-Freire C, Jun JY, Qi Y, Katovich MJ, Li Q, et al. Brain microglial cytokines in neurogenic hypertension. Hypertension. 2010;56:297–303. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.150409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu Y, Zhang ZH, Wei SG, Serrats J, Weiss RM, Felder RB. Brain perivascular macrophages and the sympathetic response to inflammation in rats after myocardial infarction. Hypertension. 2010;55:652–659. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.142836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shi P, Grobe JL, Desland FA, Zhou G, Shen XZ, Shan Z, et al. Direct pro-inflammatory effects of prorenin on microglia. PloS one. 2014;9:e92937. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shen XZ, Li Y, Li L, Shah KH, Bernstein KE, Lyden P, et al. Microglia participate in neurogenic regulation of hypertension. Hypertension. 2015;66:309–316. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.05333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gomez Perdiguero E, Klapproth K, Schulz C, Busch K, Azzoni E, Crozet L, et al. Tissue-resident macrophages originate from yolk-sac-derived erythro-myeloid progenitors. Nature. 2015;518:547–551. doi: 10.1038/nature13989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buttgereit A, Lelios I, Yu X, Vrohlings M, Krakoski NR, Gautier EL, et al. Sall1 is a transcriptional regulator defining microglia identity and function. Nature immunology. 2016;17:1397–1406. doi: 10.1038/ni.3585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kierdorf K, Erny D, Goldmann T, Sander V, Schulz C, Perdiguero EG, et al. Microglia emerge from erythromyeloid precursors via pu.1- and irf8-dependent pathways. Nature neuroscience. 2013;16:273–280. doi: 10.1038/nn.3318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parkhurst CN, Yang G, Ninan I, Savas JN, Yates JR, 3rd, Lafaille JJ, et al. Microglia promote learning-dependent synapse formation through brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Cell. 2013;155:1596–1609. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.11.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schafer DP, Lehrman EK, Kautzman AG, Koyama R, Mardinly AR, Yamasaki R, et al. Microglia sculpt postnatal neural circuits in an activity and complement-dependent manner. Neuron. 2012;74:691–705. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.03.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wes PD, Holtman IR, Boddeke EW, Moller T, Eggen BJ. Next generation transcriptomics and genomics elucidate biological complexity of microglia in health and disease. Glia. 2016;64:197–213. doi: 10.1002/glia.22866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Butovsky O, Jedrychowski MP, Moore CS, Cialic R, Lanser AJ, Gabriely G, et al. Identification of a unique tgf-beta-dependent molecular and functional signature in microglia. Nature neuroscience. 2014;17:131–143. doi: 10.1038/nn.3599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Safaiyan S, Kannaiyan N, Snaidero N, Brioschi S, Biber K, Yona S, et al. Age-related myelin degradation burdens the clearance function of microglia during aging. Nature neuroscience. 2016;19:995–998. doi: 10.1038/nn.4325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Travis MA, Sheppard D. Tgf-beta activation and function in immunity. Annual review of immunology. 2014;32:51–82. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032713-120257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.He Y, Zhang H, Yung A, Villeda SA, Jaeger PA, Olayiwola O, et al. Alk5-dependent tgf-beta signaling is a major determinant of late-stage adult neurogenesis. Nature neuroscience. 2014;17:943–952. doi: 10.1038/nn.3732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brionne TC, Tesseur I, Masliah E, Wyss-Coray T. Loss of tgf-beta 1 leads to increased neuronal cell death and microgliosis in mouse brain. Neuron. 2003;40:1133–1145. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00766-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taylor RA, Chang CF, Goods BA, Hammond MD, Grory BM, Ai Y, et al. Tgf-beta1 modulates microglial phenotype and promotes recovery after intracerebral hemorrhage. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2017;127:280–292. doi: 10.1172/JCI88647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paton JF, Raizada MK. Neurogenic hypertension. Exp Physiol. 2010;95:569–571. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2009.047282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Porreca E, Di Febbo C, Mincione G, Reale M, Baccante G, Guglielmi MD, et al. Increased transforming growth factor-beta production and gene expression by peripheral blood monocytes of hypertensive patients. Hypertension. 1997;30:134–139. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.30.1.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhu S, Liu Y, Wang L, Meng QH. Transforming growth factor-beta1 is associated with kidney damage in patients with essential hypertension: Renoprotective effect of ace inhibitor and/or angiotensin ii receptor blocker. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2008;23:2841–2846. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walshe TE, dela Paz NG, D’Amore PA. The role of shear-induced transforming growth factor-beta signaling in the endothelium. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2013;33:2608–2617. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.302161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Glass MJ, Wang G, Coleman CG, Chan J, Ogorodnik E, Van Kempen TA, et al. Nmda receptor plasticity in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus contributes to the elevated blood pressure produced by angiotensin ii. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2015;35:9558–9567. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2301-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Buck BJ, Kerman IA, Burghardt PR, Koch LG, Britton SL, Akil H, et al. Upregulation of gad65 mrna in the medulla of the rat model of metabolic syndrome. Neuroscience letters. 2007;419:178–183. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.04.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Esler M, Jennings G, Korner P, Willett I, Dudley F, Hasking G, et al. Assessment of human sympathetic nervous system activity from measurements of norepinephrine turnover. Hypertension. 1988;11:3–20. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.11.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Derynck R, Zhang YE. Smad-dependent and smad-independent pathways in tgf-beta family signalling. Nature. 2003;425:577–584. doi: 10.1038/nature02006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen SJ, Ning H, Ishida W, Sodin-Semrl S, Takagawa S, Mori Y, et al. The early-immediate gene egr-1 is induced by transforming growth factor-beta and mediates stimulation of collagen gene expression. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2006;281:21183–21197. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603270200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fang F, Shangguan AJ, Kelly K, Wei J, Gruner K, Ye B, et al. Early growth response 3 (egr-3) is induced by transforming growth factor-beta and regulates fibrogenic responses. The American journal of pathology. 2013;183:1197–1208. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fang L, Chang HM, Cheng JC, Leung PC, Sun YP. Tgf-beta1 induces cox-2 expression and pge2 production in human granulosa cells through smad signaling pathways. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2014;99:E1217–1226. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-4100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gervasi M, Bianchi-Smiraglia A, Cummings M, Zheng Q, Wang D, Liu S, et al. Junb contributes to id2 repression and the epithelial-mesenchymal transition in response to transforming growth factor-beta. The Journal of cell biology. 2012;196:589–603. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201109045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marone M, Scambia G, Bonanno G, Rutella S, de Ritis D, Guidi F, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta1 transcriptionally activates cd34 and prevents induced differentiation of tf-1 cells in the absence of any cell-cycle effects. Leukemia. 2002;16:94–105. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suo D, Park J, Harrington AW, Zweifel LS, Mihalas S, Deppmann CD. Coronin-1 is a neurotrophin endosomal effector that is required for developmental competition for survival. Nature neuroscience. 2014;17:36–45. doi: 10.1038/nn.3593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang MZ, Yao B, Wang Y, Yang S, Wang S, Fan X, et al. Inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2 in hematopoietic cells results in salt-sensitive hypertension. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2015;125:4281–4294. doi: 10.1172/JCI81550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Doyle KP, Cekanaviciute E, Mamer LE, Buckwalter MS. Tgfbeta signaling in the brain increases with aging and signals to astrocytes and innate immune cells in the weeks after stroke. J Neuroinflammation. 2010;7:62. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-7-62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.