Abstract

Guidelines recommend steroid plus cyclical cyclophosphamide (St-Cp) therapy for patients with idiopathic membranous nephropathy at high risk of progression to ESRD. Rituximab (Rtx) may be a safer alternative. In this retrospective, observational cohort study, we compared time to any adverse event (primary outcome); serious or nonserious events; partial and complete remission of the nephrotic syndrome; and a composite of doubling of serum creatinine, ESRD, or death between 100 Rtx-treated patients and 103 patients who received daily St-Cp. We monitored patients with standardized protocols and adjusted for baseline characteristics by Cox regression. Over a median follow-up of 40 months, the Rtx group had significantly fewer adverse events than the St-Cp group (63 versus 173; P<0.001), both serious (11 versus 46; P<0.001) and nonserious (52 versus 127; P<0.001). Cumulative incidence of any first (35.5% versus 69.0%; P<0.001), serious (16.4% versus 30.2%; P=0.002), or nonserious (23.6% versus 60.8%; P<0.001) event was significantly lower with Rtx. Adjusted hazard ratios (95% confidence intervals) between Rtx and St-Cp groups were 0.27 (0.16 to 0.44) for any first adverse event, 0.32 (0.15 to 0.68) for serious adverse events, and 0.23 (0.13 to 0.41) for nonserious adverse events. Although the cumulative incidence of partial remission was lower in the Rtx group, rates of complete remission and the composite renal end point did not differ significantly between groups. Because of its superior safety profile, we suggest that Rtx might replace St-Cp as first-line immunosuppressive therapy in patients with idiopathic membranous nephropathy and nephrotic syndrome.

Keywords: membranous nephropathy, adverse events, drug safety, clinical epidemiology, rituximab, cyclophosphamide

Idiopathic membranous nephropathy (IMN) is a common cause of nephrotic syndrome in adults.1 Current guidelines recommend steroid and cyclophosphamide (St-Cp) combination treatment for patients with IMN at high risk of progressive kidney failure.2 This combined regimen reduces the risk of ESRD3,4 but is associated with severe side effects.5 Uncontrolled studies suggest that monotherapy with rituximab (Rtx), an mAb against CD20 on B lymphocytes, may be an effective and safe alternative to steroids combined with alkylating agents.6–8 However, no randomized clinical trials have been performed so far to compare the safety profiles or the effectiveness in preventing ESRD of the two treatment protocols.9 IMN is a relatively rare disease, and an adequately powered trial with a sufficiently large sample size could be achieved only with a multicenter, multicontinental effort. Such a trial is not easily feasible, and therefore, conclusive data may not be available in the foreseeable future.

Comparative analyses of patient cohorts with long-enough follow-up in everyday clinical practice and careful adjustment for possible confounding bias may offer a good alternative to randomized clinical trials to evaluate effectiveness of novel therapies.10,11 Thus, we used this approach to pool data from two well defined cohorts of patients with IMN and persistent nephrotic syndrome who had been treated with Rtx or a regimen of St-Cp and have been monitored longitudinally for up to 5 years according to a predefined standardized protocol at two different nephrology units in Europe.5,6 Our working hypothesis was that Rtx was safer than combined immunosuppression, while achieving similar rates of partial or complete remission of the nephrotic syndrome.

Results

Patient Inclusion and Baseline Characteristics

We included patients from two well described cohorts.5,6 All patients of the Bergamo cohort received Rtx as the only immunosuppressive treatment and were included in this study, whereas 21 patients in the Nijmegen cohort were excluded, because they had been treated with immunosuppressive drugs other than St-Cp.12,13 In the Bergamo cohort, all patients were treated with Rtx if their 24-hour proteinuria persistently exceeded 3.5 g, despite at least 6 months treatment with maximum tolerated doses of an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor and/or an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB).5,6 In the Nijmegen cohort, 46 patients started St-Cp due to a rise of serum creatinine to values >135 μmol/L (>1.5 mg/dl) after their biopsy, 26 patients started St-Cp because of a rise in serum creatinine >50%, and 31 patients started St-Cp because of severe nephrotic syndrome. Of these 31 patients, 13 had deep hypoalbuminemia (<20 g/L), and four had suffered a venous thromboembolism before inclusion. In conclusion, 100 patients treated with Rtx and 103 patients treated with an St-Cp regimen were available for comparative analyses. At baseline, patient characteristics were similar between the two cohorts (Table 1). Disease duration, serum creatinine levels, and eGFR were comparable between groups. Use of diuretics was more frequent in the St-Cp–treated patients, whereas diastolic BP, proteinuria, and the proportion of patients who had received previous immunosuppression were higher in the Rtx group.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with IMN and persistent nephrotic syndrome refractory to conservative therapy treated with Rtx or an St-Cp–based immunosuppressive regimen

| Characteristic | Rtx, n=100 | St-Cp, n=103 | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Men, % | 72 | 76 | 0.55 |

| Age, yr | 51.5 (15.9) | 55.3 (12.7) | 0.06 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26.6 (4.3) | 26.6 (3.5) | 0.94 |

| Disease duration, mo | 11.7 (4.7–33.0) | 11.0 (4.7–24.5) | 0.73 |

| Systolic BP, mmHg | 131 (123–144) | 130 (120–150) | 0.84 |

| Diastolic BP, mmHg | 82 (75–90) | 80 (70–86) | 0.02 |

| Urine protein-to-creatinine ratio, mg/g | 6400 (4400–8894) | 8840 (5651–11,660) | <0.001 |

| eGFR, ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 59.1 (26.6) | 58.4 (22.8) | 0.84 |

| Serum creatinine, μmol/L | 106 (86–151) | 111 (88–142) | 0.29 |

| Serum albumin, g/L | 22.3 (6.8) | 21.6 (6.6) | 0.42 |

| Serum cholesterol, mmol/L | 6.9 (1.8) | 7.7 (2.6) | 0.01 |

| ACE inhibitor/ARB use, % | 94 | 88 | 0.16 |

| Diuretic use, % | 67 | 82 | 0.02 |

| Statin use, % | 74 | 62 | 0.07 |

| Prior immunosuppressive therapy, % | 32 | 12 | <0.001 |

Data are presented as proportions (%), means (SD), or medians (interquartile range). eGFR is on the basis of the abbreviated Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation for mass spectrometry–calibrated serum creatinine values. BMI, body mass index.

Safety Outcomes

Time to First Adverse Event

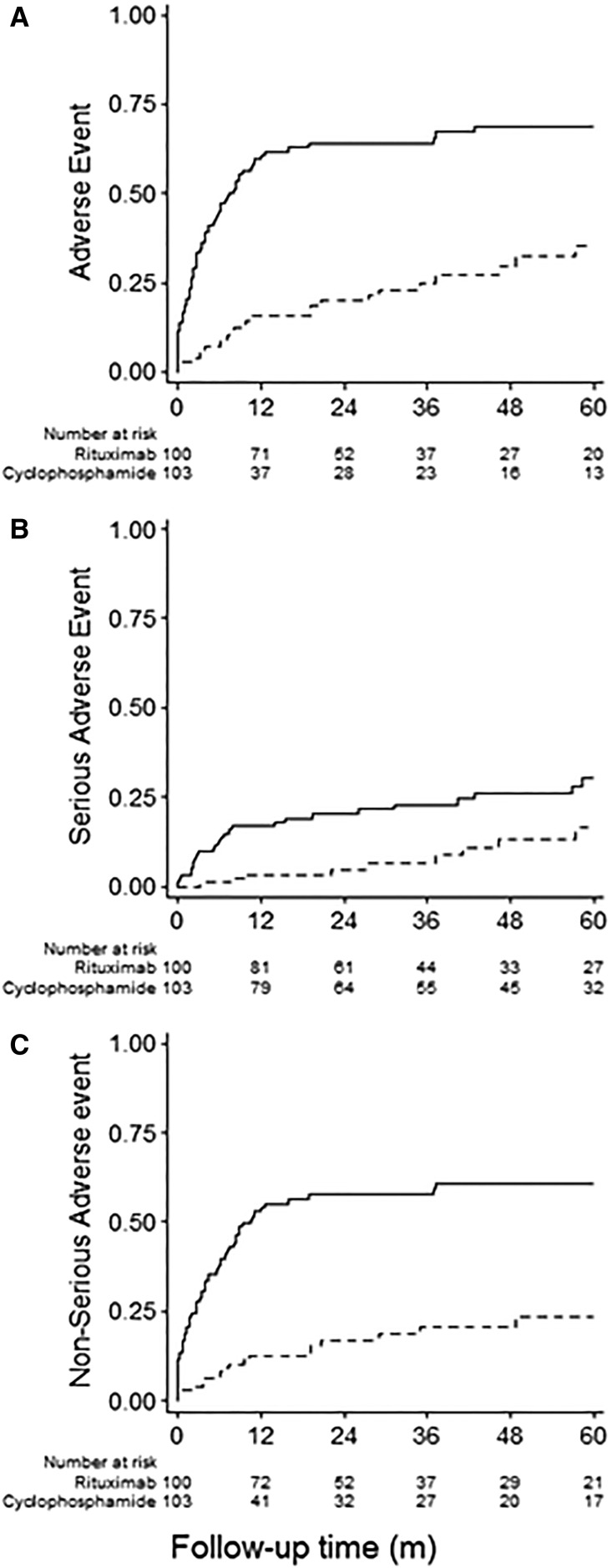

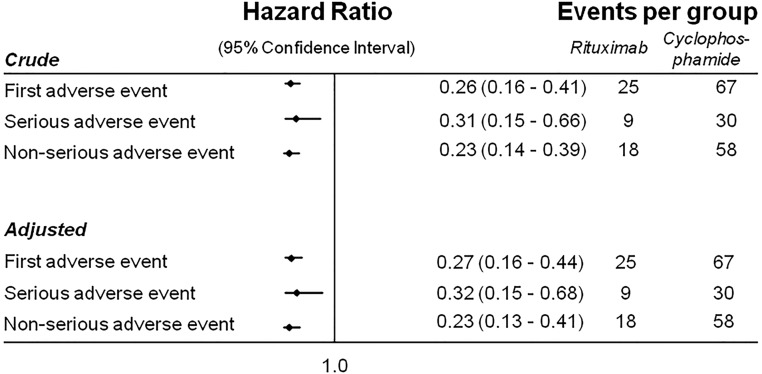

Over a median (interquartile range) follow-up of 40 (18–60) months, the cumulative incidence of any first adverse event was 35.5% (95% confidence interval [95% CI], 24.3% to 49.7%) in the Rtx group and 69.0% (95% CI, 59.1% to 78.3%) in the St-Cp group (P<0.001). The cumulative incidence of any first fatal or nonfatal serious adverse event was also significantly lower in the Rtx than the St-Cp group (16.4%; 95% CI, 8.4% to 30.4% versus 30.2%; 95% CI, 21.1% to 41.9%; P<0.01). As can be observed from Figure 1, differences in adverse event rate arose early during follow-up, with 34 and 46 of the 67 first adverse events in the St-Cp group occurring within 3 and 6 months, respectively. By comparison, four and seven of the 25 first adverse events occurred in the Rtx group after 3 and 6 months, respectively (P<0.001 for both comparisons). The number of nonserious adverse events was markedly lower in the Rtx group as well (23.6%; 95% CI, 14.9% to 36.1% versus 60.8%; 95% CI, 50.8% to 70.9%, respectively; P<0.001). Overall, the hazards of any first adverse event (Figures 1A and 2) and serious (Figures 1B and 2) and nonserious adverse events (Figures 1C and 2) considered separately were approximately three- to fourfold lower in the Rtx than the St-Cp group. The hazard ratios remained similar after adjustment for potential confounders (Figures 2 and 3) and additional sensitivity analyses considering high- versus low-dose cyclophosphamide, single versus four doses of Rtx, and restriction to patients without prior immunosuppressive therapy (Supplemental Tables 1–3).

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidence curves for safety outcomes in iMN patients treated with steroids and cyclophosphamde compared to rituximab. Cumulative incidence curves for (A) time until the first adverse event, either serious or nonserious; (B) time to the first serious adverse event; or (C) time to the first nonserious adverse event. The solid lines describe the events in St-Cp–treated patients; the dashed lines describe the events in Rtx-treated patients.

Figure 2.

Forest plot of the associations between Rtx therapy and St-Cp–based immunosuppression for the time to any first adverse event (primary outcome), nonserious adverse event, and first serious adverse event. Analyses were adjusted for the following covariates. First adverse event: sex, age, disease duration, urine protein-to-creatinine ratio (UPCR), eGFR (by Modification of Diet in Renal Disease four-variables equation), cholesterol, ACE inhibitor/ARB, diuretics, and prior immunosuppressive therapy. Serious adverse event: age, disease duration, and prior therapy. Nonserious adverse event: sex, age, disease duration, UPCR, eGFR, cholesterol, and prior immunosuppressive therapy.

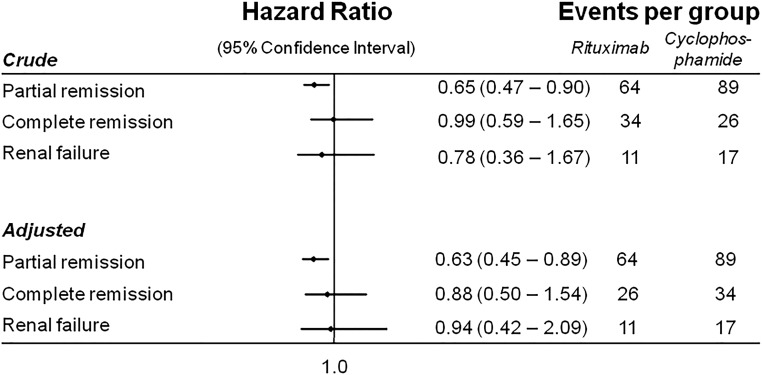

Figure 3.

Forest plot of the associations between Rtx therapy and St-Cp–based immunosuppression for the time to partial remission, complete remission, or renal failure. Analyses were adjusted for the following covariates. Partial remission: sex, age, disease duration, urine protein-to-creatinine ratio (UPCR), eGFR, and prior therapy. Complete remission: sex, age, disease duration, UPCR, eGFR, and prior therapy. Renal failure: sex, age, disease duration, UPCR, and eGFR.

Events Observed during the Whole Follow-Up Period

In total, we observed 63 adverse events (52 nonserious, including infusion reactions, and 11 serious [four fatal] in 47 Rtx-treated patients and 173 [127 nonserious and 46 serious; nine fatal] in 67 St-Cp–treated patients) (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 2.

Serious events

| Type of event | Total No. | Likely/Possibly Related | Unrelated | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rtx | St-Cp | Rtx | St-Cp | Rtx | St-Cp | |

| Fatal | 4a | 9 | 0 | 5 | 4 | 4 |

| Sepsis from the respiratory tract | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Cancera | 1a | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Cardiovascular | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 |

| Death from unknown cause | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Nonfatal | 7 | 37b | 0 | 33b | 7 | 4 |

| Myelotoxicity | 0 | 6c | 0 | 6c | 0 | 0 |

| Anemia | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Leukopenia | 0 | 6d | 0 | 6d | 0 | 0 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Malignancy | 2 | 6 | 0 | 6d | 2 | 0 |

| Blood cancers | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Solid cancers | 2 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 0 |

| Major cardiovascular events | 5 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 4 |

| Thromboembolic events | 0 | 7d | 0 | 7d | 0 | 0 |

| Pulmonary thromboembolism | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Deep venous thrombosis | 0 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Infections | 0 | 8c | 0 | 8c | 0 | 0 |

| Respiratory tract | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Urinary tract | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Sepsis from the urinary tract | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Cytomegalovirus | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Other events | 0 | 6a | 0 | 6a | 0 | 0 |

| Osteonecrosis | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Hemorrhagic cystitis | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Diarrhea | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Nausea | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Total no. of fatal and nonfatal events | 11 | 46b | 0 | 38b | 11 | 8 |

| Patients with fatal or nonfatal eventse | 9 | 30 | 0 | 22 | 9 | 8 |

Fatal and nonfatal serious events and patients with events throughout the whole observation period according to treatment group and the adjudicated causal relationships with the study treatment.

One case of lung cancer in a patient treated with St-Cp 61 months before Rtx.

P<0.05 according to a Fisher exact test.

P<0.01 according to a Fisher exact test.

P<0.001 according to a Fisher exact test.

One patient may have more than one event.

Table 3.

Nonserious events and patients with event throughout the whole observation period according to treatment group

| Type of event | Rtx, n=100 | St-Cp, n=103 |

|---|---|---|

| Myelotoxicity | ||

| Pancytopenia | 0 | 1 |

| Leukopenia and anemia | 0 | 5 |

| Anemia | 0 | 11a |

| Leukopenia | 0 | 35b |

| Thrombocytopenia | 0 | 7c |

| Total | 0 | 59b |

| Minor cardiovascular disease | 3 | 0 |

| Infections | ||

| Respiratory tract | 4 | 15b |

| Urinary tract | 0 | 1 |

| Herpes zoster | 0 | 7c |

| Other/unspecified | 3 | 14a |

| Total | 7 | 37b |

| Infusion reactionsd | 28 | 0b |

| Other events | 8 | 11 |

| Liver toxicity | 1 | 7 |

| Hyperglycemia | 2 | 10c |

| Total | 3 | 28b |

| Total no. of nonserious events | 52 | 127 |

| Patients with nonserious eventse | 41 | 58 |

P<0.001 according to the Fisher exact test, St-Cp versus Rtx.

P<0.01 according to the Fisher exact test, St-Cp versus Rtx.

P<0.05 according to the Fisher exact test, St-Cp versus Rtx.

Bronchial wheezing, dyspnea, rash, erythema, itching, rhinorrhea, and hypotension.

One patient may have more than one event.

Fatal Events.

In total, four patients in the Rtx group and nine in the St-Cp group died during the study (Table 2). One Rtx-treated patient died from stroke at 83 years of age, and two dies from myocardial infarction when both were age 79 years old. These events were considered to be unrelated to Rtx therapy. One additional Rtx-treated patient who had been treated with St-Cp 61 months before inclusion died of lung cancer. This event was considered to be related to previous immunosuppression rather than Rtx. In the St-Cp group, three patients died of sepsis from a respiratory tract infection. One patient died of lung cancer, and one died from a bladder cancer that was preceded by hemorrhagic cystitis. This patient had been treated with steroid and chlorambucil 10 years before the St-Cp exposure. The two fatal cardiovascular events were probably unrelated to St-Cp exposure, because they were observed in two patients with a previous history of cardiovascular disease. Two patients in the St-Cp group died at home from unknown causes. In both patients, death occurred >24 months after the last recorded adverse event, and neither had records of acute illness, cardiovascular disease, or malignancy. Thus, at least five treatment-related fatal events were observed in the St-Cp group compared with none in the Rtx group (Table 2).

Nonfatal Events.

Twenty-eight of the 52 nonserious events in the Rtx group were infusion reactions that were expected, were mild and transient, and never required treatment withdrawal or dose reduction (Table 3). Other events included incidental community-acquired infections that never required hospitalization, three minor cardiovascular events, and two cases of hyperglycemia observed in two patients with a long history of diabetes. However, blood glucose control improved in three patients with hyperglycemia, possibly related to steroid exposure during previous courses of immunosuppression. All of the 11 serious adverse events, including eight cardiovascular events and three cases of malignancy, were considered to be unrelated to treatment (Table 2).

Among the 127 nonserious adverse events reported in the St-Cp group, there were 59 cases of myelotoxicity, including a single case of pancytopenia, five cases of combined leukopenia and anemia, and 11, 35, and four cases of isolated anemia, leukopenia, and thrombocytopenia, respectively. In addition, 37 infectious episodes and ten cases of steroid-induced hyperglycemia were noted. Twenty-three of the 37 nonfatal serious events in the St-Cp group were likely related to treatment, ten were possibly related, and only four nonfatal events were considered as not related to treatment. Among nonfatal serious adverse events possibly related to treatment, there were three blood malignancies (non-Hodgkin lymphoma, chronic lymphatic leukemia, and acute myeloid leukemia), three solid cancers (bladder, larynx, and colon), and isolated cases of urosepsis, osteonecrosis, and hemorrhagic cystitis.

Effectiveness Outcomes

In total, 64 patients in the Rtx group and 89 patients in the St-Cp group went into partial remission; the resulting cumulative incidence of partial remission was lower in the Rtx group (70.6%; 95% CI, 60.1% to 80.4%) compared with the St-Cp group (94.8%; 95% CI, 88.4% to 98.3%; P=0.01). However, the rates of complete remission in the Rtx and St-Cp groups did not differ significantly (40.3%; 95% CI, 28.7% to 54.5% versus 41.5%; 95% CI, 31.4% to 53.3%; P=0.95). Consistently, the adjusted Cox regression revealed a statistically significant difference in partial remission rate but did not reveal a statistically significant difference in the incidence of complete remission between groups (Figure 2). In total, 11 patients in the Rtx group reached the combined end point (defined as a doubling of serum creatinine, ESRD, the need for chronic RRT, or death from any cause), of whom six patients showed a doubling of serum creatinine (one after a relapse), two patients developed ESRD, and three patients died. By comparison, 17 patients in the St-Cp group reached the combined end point: 12 patients because of a doubling of creatinine (ten after a relapse), one person developed ESRD after relapse, and four died (two after a relapse). The cumulative incidence rates of the combined end point in the Rtx (17.9%; 95% CI, 10.0% to 30.8%) and St-Cp (21.8%; 95% CI, 13.7% to 33.4%) groups were similar (P=0.52). Here too, Cox regression did not show substantial differences between both groups. Largely similar findings were observed in the sensitivity analyses (Supplemental Tables 1–3).

Discussion

In this study, we compared the safety profile of Rtx treatment with that of a combined St-Cp immunosuppressive regimen in two well defined cohorts of patients with IMN and persistent nephrotic syndrome who had been followed at two nephrology units in Europe. Data showed that, at 5 years, the incidence rates of serious and nonserious adverse events were three- to fourfold lower in Rtx-treated patients than patients treated with St-Cp. Because the incidence of complete remissions of the nephrotic syndrome was virtually identical between the two groups, these results indicate the Rtx is a promising alternative to St-Cp as first-line immunosuppressive therapy in IMN.

Baseline characteristics, notably concomitant treatments, previous disease duration, and kidney function, were similar in both cohorts. Moreover, results were similar in multivariable analyses adjusting for predefined baseline covariates known to be associated with disease outcome and response to treatment. The potential confounding role of previous immunosuppression was also reasonably excluded by sensitivity analyses restricted to patients who had never received immunosuppressive treatments for IMN before inclusion in this study.

Safety

The difference in the safety profile of the two treatments under evaluation was impressive, not only because of the large difference in the incidence of adverse events between the two groups considered as a whole but in particular, because of the remarkably higher rates of serious and even fatal adverse events that were observed in the St-Cp group. Moreover, 38 of the 46 serious events observed in this group were considered likely or possibly treatment related, whereas all of the 11 serious events observed in the Rtx group were considered as unrelated to treatment. Among treatment-related serious adverse events in the St-Cp group, there were six cases of myelotoxicity that were most likely due to a direct effect of the alkylating agent, whereas the seven thromboembolic events were possibly related to the prothrombotic effect of steroids. Also, the case of osteonecrosis was conceivably related to concomitant steroid therapy as well as the ten cases of hyperglycemia. The frequency and severity of infections were also remarkably different between treatment groups. The events observed in the Rtx group were similar to those that are commonly observed in the general population and were unlikely associated with Rtx exposure, whereas those observed in the St-Cp–treated patients were more likely to be severe and result in hospital admission. Of note, in these patients, there were 11 serious infections, which included three fatal cases of sepsis, in addition to 37 nonserious infections.

Moreover, three blood malignancies and five solid cancers (two fatal) were observed in the St-Cp group, and all of them were considered possibly related to treatment. One cancer was likely related to exposure several years before to chlorambucil. Taken together, these findings seem to be consistent with the well established carcinogenic effect of alkylating agents.14,15 Rtx, however, was not associated with an excess risk of cancer in a large cohort of patients with rheumatoid arthritis with up to 11 years of follow-up.16 However, the St-Cp–based treatment protocol in this study resulted in higher cumulative doses (up to 36 g) compared with those recommended by the Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guidelines.2 This might explain, at least in part, the large excess of adverse events observed in patients on dual immunosuppression with St-Cp compared with those on Rtx monotherapy. However, 34 of the total number of 67 (51%) adverse events in the St-Cp group occurred within 3 months and 46 (69%) occurred within 6 months compared with four (16%) and seven (28%) of the 25 events, respectively, in the Rtx group. During this period, overall patient exposure to St-Cp was similar to the exposure recommended by KDIGO guidelines.2 Thus, the large difference in adverse events observed in our study can only, in part, be explained by the high cumulative St-Cp doses and was clinically relevant, even at currently recommended doses. Arguably, the rate of adverse events observed after 3 and 6 months of observation in St-Cp–treated patients exceeded the adverse event rate reported in the trial by Ponticelli and coworkers.17–19 This might be explained by incomplete recording of events in studies of patients before 1996, when the International Conference on Harmonization (ICH) of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use established the Guideline for Good Clinical Practice (GCP) was published.20 The later trial by Jha et al.4 also reported a lower adverse event rate compared with this cohort. However, this study too was designed before GCP guidelines for reporting of adverse events were established, and patient inclusion was completed before 1996 as well. Moreover, GCP guidelines were only adopted by Indian regulatory bodies in 2013.21 Thus, it is conceivable that the risk of adverse events under-reporting might also apply to this more recent study. Moreover, patients in the trials by Ponticelli and coworkers17–19 and Jha et al.4 had a markedly better kidney function at the time of cyclophosphamide therapy compared with this cohort. Pharmacokinetic studies have shown that cyclophosphamide metabolites are predominantly excreted via the kidneys.22 This may explain why short-term toxic effects were less frequent in previous studies with cyclophosphamide. Our study had a follow-up of 5 years, and therefore, we cannot address long-term side effects. It is possible that the St-Cp regimen used in this study results in more long-term adverse effects compared with the regimen used by Ponticelli and coworkers.17–19

Effectiveness

This study provides the first head to head comparison of Rtx and St-Cp–based immunosuppression. At present, there are no trials underway to compare Rtx monotherapy with St-Cp. Such a trial would require close to 1000 patients assuming an α of 5%, 90% power, a partial remission rate of 90% in the St-Cp group, and a hazard ratio of 0.8 as the noninferiority margin. This is hard to achieve considering that IMN is a relatively rare disease and that such a trial should be restricted to just a subgroup of patients who are at high risk of progression or complications because of persistent nephrotic syndrome.2 The data presented here have been collected in two well defined and carefully followed cohorts and may thus offer the best available data to date. This study showed that the incidence of complete remissions was similar between groups. Complete remission is a strong predictor for decreased risk of progression to ESRD in IMN23 and may be acceptable surrogate marker for effectiveness until more long-term follow-up data become available. A recent trial by the Randomized Multicenter Study to Evaluate Rituximab for the Treatment of Idiopathic Membranous Nephropathy (GEMRITUX) Study group showed that, after a median follow-up of 17 months, Rtx-treated patients were more likely to be anti-phospholipase-A2-receptor antibody depleted during early follow-up. This was a clinically relevant finding, because depletion of circulating anti-phospholipase-A2-receptor antibodies is a strong predictor of complete and persistent remission of nephrotic syndrome.24 Importantly, there was no difference in serious adverse events between Rtx-treated patients and controls. In conclusion, our results combined with the findings by the GEMRITUX Study converge to indicate that Rtx is indeed safe and efficacious for the induction of remission of proteinuria in patients with IMN and persistent nephrotic syndrome, despite optimized conservative therapy.

Limitations and Strengths

The study compared two cohorts treated and monitored at two different centers in Europe. Geographical variation due to differences in health systems, diagnostic workup procedures, or genetic background may have caused some residual confounding. However, any confounding effect would have to be extreme to completely remove the association between adverse events and treatment protocol. This is unlikely, because patient characteristics—including ethnicity, age and sex distribution, kidney function, concomitant medications (including conservative therapy with drugs that may affect urinary protein excretion, such as ACE inhibitors and ARBs), and monitoring protocols—were quite similar between groups. The consistency of data across a series of different considered events, such as malignancies, infectious episodes, thromboembolic events, and others, provides additional evidence of the robustness of the findings. Moreover, the proportion of patients with prior immunosuppression was almost threefold higher in the Rtx than the St-Cp group, and the difference between groups was significant. Finding that, despite this excess risk, the incidence of serious and nonserious complications was remarkably lower in the Rtx group provided additional evidence of the superior safety profile of Rtx monotherapy compared with St-Cp.

Analyses were retrospective, but they were performed according to predefined study protocol and statistical plans. Outcome data were obtained from patient clinical records, which may have resulted in underestimation of adverse event rates. However, this potential limitation applied to all patients and therefore, is not expected to translate into a systematic bias in favor of one of the two treatment groups. Likewise, proteinuria and kidney function were monitored closely during treatment, because these are used as therapeutic effectiveness readouts in everyday practice. The definition of partial remission was on the basis of predefined changes in 24-hour urinary protein excretion or protein-to-creatinine ratio in spot urine samples in the Rtx and St-Cp cohorts, respectively. This approach unlikely introduced a systematic error, because we previously found that the two variables are strongly correlated and that their regression line is close to the line of identity.25 Moreover, in our experience, patients who show partial remission at 3500 mg/10 mmol creatinine also show partial remission according to more stringent criteria.26 We observed a lower rate of partial remissions in the Rtx group. Although partial remission predicts renal outcome to some degree, partial remissions are less informative than complete remissions. Indeed, there were no differences in renal failure rate between the groups. Still, we acknowledge that data on efficacy outcomes should be considered more cautiously than safety data, because they were secondary outcome variables of the study.

Closure of the observation period at 5 years was instrumental to obtain the same follow-up duration in both cohorts, which prevented a possible source of bias in the recording of time-dependent events. In addition, the St-Cp protocol used in this study resulted in a higher cumulative dose and longer treatment duration compared with current KDIGO guidelines. Therefore, we cannot rule out that the St-Cp regimen in this study resulted in more long-term adverse effects compared with the treatment recommended by KDIGO. However, more than one half of the adverse events occurred within 3 months of St-Cp therapy, at which point the event rate was eightfold higher than in the Rtx group. Furthermore, sensitivity analyses by different cumulative cyclophosphamide doses showed similarly large differences in adverse event rates between the two treatment groups.

A major strength of the study was that both cohorts of patients were treated and monitored according to standardized protocols in the context of an outpatient clinic. Thus, the results of our study can be generalized to the average population of patients with IMN and nephrotic syndrome that may refer to a nephrology unit in everyday clinical practice. Although no formal adjudication process was possible, all adverse events were predefined on the basis of standard definitions, and data from both cohorts were merged in a common database after they had been crosschecked for consistency with predefined definitions by investigators from the two involved centers.

Clinical Effect

KDIGO guidelines recommend St-Cp as a first-line immunosuppressive therapy in IMN.2 Calcineurin inhibitors are suggested for those patients who prefer not to be treated with alkylating agents or gave contraindications. Importantly, the guidelines state that trials are needed to compare alkylating agents or calcineurin inhibitors with Rtx. There are currently two trials underway to evaluate immunosuppressive treatment in membranous nephropathy; however, neither compare Rtx monotherapy with St-Cp. The Membranous Nephropathy Trial of Rituximab Study (clinicaltrials.govidentifier:NCT01180036) will address whether Rtx monotherapy may have a better risk/benefit profile compared with cyclosporin therapy,27 whereas the Sequential Therapy with Tacrolimus–Rituximab Versus Steroids Plus Cyclophosphamide in Patients with Primary Membranous Nephropathy Trial (clinicaltrials.cov identifier: NCT01955187) will compare Rtx after tacrolimus therapy with St-Cp.28 These trials in conjunction with our study will result in valuable information to improve treatment in patients with IMN.

Rtx monotherapy was safer than daily continuous St-Cp therapy. Compared with patients treated with the combined immunosuppressive regimen, patients treated with Rtx were far less likely to suffer serious adverse events. In addition, there were fewer nonserious events in the Rtx group. Thus, because of its superior safety profile, Rtx might be considered as an alternative to St-Cp–based immunosuppression as first-line therapy in patients with IMN and persistent nephrotic syndrome, despite conservative treatment.

Concise Methods

Patients and Treatments

Rtx Cohort

Since April of 2001, all consecutive and consenting patients presenting to the Nephrology Unit of the Azienda Socio Sanitaria Territoriale, Ospedale Papa Giovanni XXIII in Bergamo, Italy with 24-hour proteinuria persistently exceeding 3.5 g, despite at least 6 months treatment with maximum tolerated doses of an ACE inhibitor and/or an ARB, were treated with four weekly doses of 375 mg/m2 Rtx infused intravenously. From November of 2005 on, only a single dose was administered unless there were greater than five circulating B cells per cubic millimeter on the morning after the first dose, in which case, an additional dose was administered. The two approaches were previously found to have a virtually identical risk/benefit profile in this context, with the B cell–driven approach allowing substantial cost-savings for treatment.29

St-Cp Cohort

Patients referred to the Radboud University Medical Center in Nijmegen, The Netherlands between 1995 and 2012 received an St-Cp combination therapy if serum creatinine concentrations increased to >135 μmol/L (approximately 1.5 mg/dl) or by 50% or if patients suffered severe disabling symptoms of the nephrotic syndrome. Oral cyclophosphamide (1.5 mg/kg daily) was administered for 6–12 months, and methylprednisolone pulses (1 g) were infused on days 1–3, 61–63, and 121–123 in combination with 0.5 mg/kg oral prednisone every other day for 5 months before tapering.

Rtx- and St-Cp–treated patients were prospectively monitored for up to 5 years with predefined serial measurements of clinical and laboratory parameters that are normally evaluated in everyday clinical practice.5,6

Data were recorded and reported according to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines for reporting observational studies (Supplemental Table 4).

Outcomes and Definitions

The primary outcome was the time to any first adverse event defined as “any untoward medical occurrence in a patient administered a pharmaceutical product” according to the ICH/GCP criteria. Adverse events were regularly recorded at each visit and hospitalization. They were also obtained by revision of patient charts and in case of missed outpatient visits, directly contacting patients or their relatives. The severity of observed adverse events and their causal relationships with treatments were assessed by physicians directly in charge of the patients and chart review on the basis of ICH/GCP standardized criteria, and they were categorized by type (Supplemental Table 5).

Secondary outcomes were as follows. (1) Time to first serious adverse event defined as “any untoward medical occurrence that at any dose: results in death, is life-threatening, requires in-patient hospitalization or prolongation thereof, results in permanent or significant disability, or is a congenital abnormality or birth defect in offspring.” (2) Time to first nonserious adverse event defined as any adverse event not classified as serious. (3) Time to partial remission of the nephrotic syndrome defined as a ≥50% decrease in urinary protein-to-creatinine ratio or 24-hour proteinuria from the start of treatment to a level <3500 mg/10 mmol creatinine (approximately 3100 mg/g creatinine) or <3 g/24 h and with a stable serum creatinine.20 This includes patients who subsequently developed a complete remission at a later stage. (4) Time to complete remission of the nephrotic syndrome defined as a urine protein-to-creatinine ratio <300 mg/g. (5) Time to a combined end point of doubling of serum creatinine, ESRD, and need for chronic RRT or death from any cause

We predefined potential baseline confounders, such as sex, age, weight, disease duration, systolic and diastolic BP, urine protein-to-creatinine ratio, serum creatinine, GFR estimated by the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease four-variables equation (eGFR), serum albumin, serum cholesterol, ACE inhibitor/ARB use, diuretic use, statin use, and prior immunosuppression, all of which were considered in multivariable outcome analyses. Disease duration was defined as the time in months between the biopsy confirming the diagnosis of IMN and the start of either Rtx or St-Cp therapy.

Statistical Methods

We expressed baseline characteristics as frequencies and proportions for categorical variables, means and SDs for normally distributed variables, and medians and interquartile ranges for skewed variables. We compared baseline characteristics of Rtx- and St-Cp–treated patients using chi-squared tests, t tests, and median (Wilcoxon rank sum) tests. Next, to obtain similar observation periods in the two cohorts, we truncated the follow-up at 60 months. We compared cumulative incidences with a log rank test. Additionally, we estimated hazard ratios to compare survival until the first adverse event between the Rtx and St-Cp groups. Subsequently, we adjusted for baseline covariates. The proportional hazards assumption was checked using a plot of Schoenfeld residuals by follow-up time. Likewise, we estimated hazard ratios to compare survival until the first serious adverse event, renal failure, and complete remission of proteinuria between the Rtx and the St-Cp groups. All infusion reactions were recorded and reported. However, by definition, they were simultaneous to Rtx treatment and transient in nature, and therefore, they were not considered for survival analyses. Differences in the proportion of adverse events by type between the Rtx and the St-Cp groups were compared using Fisher exact tests. As a sensitivity analysis, first, we repeated the Cox regressions by different dosage of the respective immunosuppressive regimens, being high (≥20 g) and low (<20 g) cumulative St-Cp doses and one compared with four Rtx doses. Second, we repeated the Cox regressions after excluding patients who had received immunosuppression before inclusion in this study.

Analyses were performed using Stata 11.2 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). For all statistical tests, a two-sided P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The work leading to these results received funding from European Union Seventh Framework Programme FP7/2007–2013 grant 305608: European Consortium for High-Throughput Research in Rare Kidney Diseases. J.A.J.G.v.d.B. and J.M.H. are supported by Dutch Kidney Foundation grants DKF14OKG07 and KJPB11.021.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://jasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1681/ASN.2016091022/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Ponticelli C, Glassock RJ: Glomerular diseases: Membranous nephropathy--A modern view. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 609–616, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.KDIGO Glomerulonephritis Work Group: KDIGO clinical practice guideline for glomerulonephritis. Kidney Int Suppl 2: 186–197, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ponticelli C, Zucchelli P, Passerini P, Cesana B, Locatelli F, Pasquali S, Sasdelli M, Redaelli B, Grassi C, Pozzi C: A 10-year follow-up of a randomized study with methylprednisolone and chlorambucil in membranous nephropathy. Kidney Int 48: 1600–1604, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jha V, Ganguli A, Saha TK, Kohli HS, Sud K, Gupta KL, Joshi K, Sakhuja V: A randomized, controlled trial of steroids and cyclophosphamide in adults with nephrotic syndrome caused by idiopathic membranous nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 1899–1904, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van den Brand JAJG, van Dijk PR, Hofstra JM, Wetzels JFM: Long-term outcomes in idiopathic membranous nephropathy using a restrictive treatment strategy. J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 150–158, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ruggenenti P, Cravedi P, Chianca A, Perna A, Ruggiero B, Gaspari F, Rambaldi A, Marasà M, Remuzzi G: Rituximab in idiopathic membranous nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 23: 1416–1425, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beck LH Jr., Fervenza FC, Beck DM, Bonegio RG, Malik FA, Erickson SB, Cosio FG, Cattran DC, Salant DJ: Rituximab-induced depletion of anti-PLA2R autoantibodies predicts response in membranous nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 22: 1543–1550, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Remuzzi G, Chiurchiu C, Abbate M, Brusegan V, Bontempelli M, Ruggenenti P: Rituximab for idiopathic membranous nephropathy. Lancet 360: 923–924, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen Y, Schieppati A, Chen X, Cai G, Zamora J, Giuliano GA, Braun N, Perna A: Immunosuppressive treatment for idiopathic membranous nephropathy in adults with nephrotic syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 10: CD004293, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ray WA: Evaluating medication effects outside of clinical trials: New-user designs. Am J Epidemiol 158: 915–920, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vandenbroucke JP: Observational research, randomised trials, and two views of medical science. PLoS Med 5: e67, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Branten AJ, du Buf-Vereijken PW, Vervloet M, Wetzels JF: Mycophenolate mofetil in idiopathic membranous nephropathy: A clinical trial with comparison to a historic control group treated with cyclophosphamide. Am J Kidney Dis 50: 248–256, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van de Logt A-E, Hofstra JM, Wetzels JF: Synthetic ACTH in patients with idiopathic membranous nephropathy: Long term follow-up. J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 210A, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van den Brand JAJG, van Dijk PR, Hofstra JM, Wetzels JFM: Cancer risk after cyclophosphamide treatment in idiopathic membranous nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 1066–1073, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heijl C, Harper L, Flossmann O, Stücker I, Scott DG, Watts RA, Höglund P, Westman K, Mahr A; European Vasculitis Study Group (EUVAS) : Incidence of malignancy in patients treated for antineutrophil cytoplasm antibody-associated vasculitis: Follow-up data from European Vasculitis Study Group clinical trials. Ann Rheum Dis 70: 1415–1421, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Vollenhoven RF, Fleischmann RM, Furst DE, Lacey S, Lehane PB: Longterm safety of rituximab: Final report of the rheumatoid arthritis global clinical trial program over 11 years. J Rheumatol 42: 1761–1766, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ponticelli C, Zucchelli P, Imbasciati E, Cagnoli L, Pozzi C, Passerini P, Grassi C, Limido D, Pasquali S, Volpini T: Controlled trial of methylprednisolone and chlorambucil in idiopathic membranous nephropathy. N Engl J Med 310: 946–950, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ponticelli C, Zucchelli P, Passerini P, Cesana B; The Italian Idiopathic Membranous Nephropathy Treatment Study Group : Methylprednisolone plus chlorambucil as compared with methylprednisolone alone for the treatment of idiopathic membranous nephropathy. N Engl J Med 327: 599–603, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ponticelli C, Zucchelli P, Passerini P, Cagnoli L, Cesana B, Pozzi C, Pasquali S, Imbasciati E, Grassi C, Redaelli B: A randomized trial of methylprednisolone and chlorambucil in idiopathic membranous nephropathy. N Engl J Med 320: 8–13, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.ICH Expert Working Group : Guideline for Good Clinical Practice International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use, International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use, European Community, Brussels, Belgium, 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saxena P, Saxena R: Clinical trials: Changing regulations in India. Indian J Community Med 39: 197–202, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fleming RA: An overview of cyclophosphamide and ifosfamide pharmacology. Pharmacotherapy 17: 146S–154S, 1997 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cattran DC, Kim ED, Reich H, Hladunewich M, Kim SJ; Toronto Glomerulonephritis Registry group : Membranous nephropathy: Quantifying remission duration on outcome. J Am Soc Nephrol 28: 995–1003, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ruggenenti P, Debiec H, Ruggiero B, Chianca A, Pellé T, Gaspari F, Suardi F, Gagliardini E, Orisio S, Benigni A, Ronco P, Remuzzi G: Anti-phospholipase A2 receptor antibody titer predicts post-rituximab outcome of membranous nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol 26: 2545–2558, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ruggenenti P, Gaspari F, Perna A, Remuzzi G: Cross sectional longitudinal study of spot morning urine protein:creatinine ratio, 24 hour urine protein excretion rate, glomerular filtration rate, and end stage renal failure in chronic renal disease in patients without diabetes. BMJ 316: 504–509, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van den Brand JA, Hofstra JM, Wetzels JFM: Low-molecular-weight proteins as prognostic markers in idiopathic membranous nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 6: 2846–2853, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fervenza FC, Canetta PA, Barbour SJ, Lafayette RA, Rovin BH, Aslam N, Hladunewich MA, Irazabal MV, Sethi S, Gipson DS, Reich HN, Brenchley P, Kretzler M, Radhakrishnan J, Hebert LA, Gipson PE, Thomas LF, McCarthy ET, Appel GB, Jefferson JA, Eirin A, Lieske JC, Hogan MC, Greene EL, Dillon JJ, Leung N, Sedor JR, Rizk DV, Blumenthal SS, Lasic LB, Juncos LA, Green DF, Simon J, Sussman AN, Philibert D, Cattran DC; Mentor Consortium group : A Multicenter Randomized Controlled Trial of Rituximab versus Cyclosporine in the Treatment of Idiopathic Membranous Nephropathy (MENTOR). Nephron 130: 159–168, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rojas-Rivera J, Fernández-Juárez G, Ortiz A, Hofstra J, Gesualdo L, Tesar V, Wetzels J, Segarra A, Egido J, Praga M: A European multicentre and open-label controlled randomized trial to evaluate the efficacy of sequential treatment with TAcrolimus-rituximab versus steroids plus cyclophosphamide in patients with primary MEmbranous nephropathy: The STARMEN study. Clin Kidney J 8: 503–510, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cravedi P, Ruggenenti P, Sghirlanzoni MC, Remuzzi G: Titrating rituximab to circulating B cells to optimize lymphocytolytic therapy in idiopathic membranous nephropathy. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2: 932–937, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.