ABSTRACT

Aging of the patient population has led to increased occurrence of accidental falls in acute care settings. The aim of this study is to survey the annual occurrence of falls in a university hospital, and to examine procedures to prevent fall. A total of 49,059 inpatients were admitted to our hospital from April 2015 to March 2016. A fall assessment scale was developed to estimate the risk of fall at admission. Data on falls were obtained from the hospital incident reporting system. There were fall-related incidents in 826 patients (1.7%). Most falls occurred in hospital rooms (67%). Adverse events occurred in 101 patients who fell (12%) and were significantly more frequent in patients aged ≥80 years old and in those wearing slippers. The incidence of falls was also significantly higher in patients in the highest risk group. These results support the validity of the risk assessment scale for predicting accidental falls in an acute treatment setting. The findings also clarify the demographic and environmental factors and consequences associated with fall. These results of the study could provide important information for designing effective interventions to prevent fall in elderly patients.

Key Words: fall assessment sheet, fall, elderly patients, hospitalization, risk management

INTRODUCTION

Japan has become a super-aging society in which an increasing number of older patients are occupying acute hospital beds. With accelerating aging of the patient population, fall has increasingly been recognized as a challenge to patient safety in terms of its negative consequences on mobility and even mortality. One year mortality rate due to hip fractures in elderly patients of 10.1% has been reported by the Japanese Orthopaedic Association Committee on Osteoporosis.1) Fall-related injuries are steadily increasing in acute care,2) and they not only require additional examination or treatment but also affect the length and cost of hospital stay. Some related incidences may even lead to a medical lawsuit. Therefore, prevention of falls has become one of the most important issues in medical safety. Older patients are likely to fall due to a decrease in balance, loss of skeletal muscles, as well as many other physical dysfunctions associated with aging. Chronic medical conditions such as diabetes and hypertension are also risk factors of falls and subsequent fractures.3-5)

In our hospital, we have founded a fall-prevention working group composed of 10 members, including doctors, nurses, and physiotherapists. The mission of the working group is to improve medical quality and safety management through the prevention of falls, which includes the accurate identifications and analyses of fall cases, and the development of education and training programs for hospital staffs. The purpose of this study is to investigate the occurrence of falls in all wards of our hospital in the past year, and to examine procedures to prevent falls.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A total of 49,059 inpatients admitted to our hospital from April 2015 to March 2016 were subjected to analysis. Data were obtained prospectively from the hospital incident / accident reporting system. A fall was defined as an involuntary change of posture whereby a patient ended up lying on the floor. All patients who had a fall were subsequently followed up until discharge.

For the assessment of fall risk, we used a fall risk score that was originally developed by the working group. This score was evaluated routinely on admission, in each week of hospitalization, at the time of a fall, and as the medical condition changed. The degree of fall risk was determined using a fall assessment score sheet comprising 33 risk items including age, history of falls, activities of daily living, and cognition (Table 1). The sum of the risk items served as the risk score. Patients were classified into three groups: Grade 1 (low risk), Grade 2 (moderate risk), and Grade 3 (high risk), based on risk scores of 0–5, 6–15, and ≥16 and including at least one item in each category, respectively. Demographic data (incidence of fall, sex, and age), fall risk score, time of occurrence, location of occurrence, number of falls, footwear, and adverse events (an injury due to fall that required treatment) were collected.

Table 1.

Assessment score sheet

| Assessment | Yes | No |

|---|---|---|

| Past history | ||

| History of fall | 1 | 0 |

| History of syncope | 1 | 0 |

| History of convulsions | 1 | 0 |

| Impairment | ||

| Visual impairment | 1 | 0 |

| Hearing impairment | 1 | 0 |

| Vertigo | 1 | 0 |

| Mobility | ||

| Wheelchair | 1 | 0 |

| Cane | 1 | 0 |

| Walker | 1 | 0 |

| Need assistance | 1 | 0 |

| Cognition | ||

| Disturbance of consciousness | 1 | 0 |

| Restlessness | 1 | 0 |

| Memory disturbance | 1 | 0 |

| Decreased judgment | 1 | 0 |

| Dysuria | ||

| Incontinence | 1 | 0 |

| Frequent urination | 1 | 0 |

| Need helper | 1 | 0 |

| Go to bathroom often at night | 1 | 0 |

| Difficult to reach the toilet | 1 | 0 |

| Drug use | ||

| Sleeping pills | 1 | 0 |

| Psychotropic drugs | 1 | 0 |

| Morphine | 1 | 0 |

| Painkiller | 1 | 0 |

| Antiparkinson drug | 1 | 0 |

| Antihypertensive medication | 1 | 0 |

| Anti-cancer agents | 1 | 0 |

| Laxatives | 1 | 0 |

| Dysfunction | ||

| Muscle weakness | 1 | 0 |

| Paralysis, numbness | 1 | 0 |

| Dizziness | 1 | 0 |

| Bone malformation | 1 | 0 |

| Rigidity | 1 | 0 |

| Brachybasia | 1 | 0 |

Patients were classified into three groups: Grade 1 (low risk), Grade 2 (moderate risk), and Grade 3 (high risk) based on total scores of 0–5, 6–15, and ≥16 and including at least one item in each category, respectively.

The protocol of this study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Nagoya University Graduate School of Medicine.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

The differences between two groups were analyzed by Mann-Whitney U test or Student t-test, and those among three groups were analyzed by Kruskal-Wallis test. A multivariate logistic regression model was constructed using variables with P<0.05. Multivariate odds ratios (ORs) are reported with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS ver. 23 for Windows (IBM Inc., Chicago, IL). A p value < 0.05 was considered to show statistical significance in all analyses.

RESULT

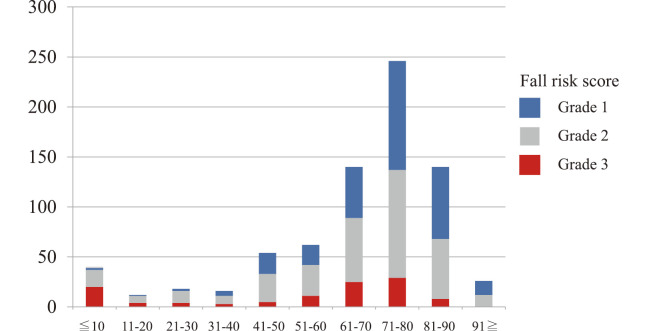

Patient demographics are shown in Table 2. Falls were reported in 826 patients (454 males, 372 females) among 49,059 admissions, giving a fall rate of 1.7%. Many of falls involved patients in their 70s, followed by 60s and 80s (Figure 1). Falls were most commonly observed between 4:00 AM and 7:00 AM. Among those who fell, most patients (45%) were classified in Grade 3 based on the fall risk score using the assessment score sheet (Table 2) In terms of medical conditions, falls occurred most frequently in patients with neurological disease, followed by gastroenterological disease and pediatric disease. Regarding the location, the majority of falls occurred in patients’ rooms (67%). A total of 184 patients had two falls, and 60 had three or more falls (Table 2). Multiple fallers (at least twice) had a significantly higher rate of adverse events (Table 3). Adverse events occurred in 101 patients, including falls requiring wound suture in 92 patients, fracture in seven patients, and brain hemorrhage in two patients respectively (Table 3). Adverse events due to falls, relative to non-adverse events, occurred significantly more frequently in patients over 80 years of age, and in patients wearing slippers among all footwears (p<0.01) (Table 3). The incidence of falls was significantly higher in patients in Grade 3 based on the fall risk score (p<0.05) (Table 4). In multivariate logistic regression using risk factors, age over 80 (OR 1.65, 95%CI 1.03–2.64; p=0.039) and wearing slippers (OR 1.72, 95%CI 1.05–2.83; p=0.033) were significantly associated with adverse events (Table 5).

Table 2.

Demographic and characteristics of cases of fall

| Variable | n=826 |

|---|---|

| Age (SD) | 58.1 (23.5) |

| Sex (M/F) | 454 /372 |

| Primary disease | |

| Neurological | 214 (26%) |

| Gastroenterological | 145 (18%) |

| Pediatrics | 57 (7%) |

| Respiratory | 51 (6%) |

| Cardiac | 41 (5%) |

| Otolaryngology | 40 (5%) |

| Orthopaedics | 33 (4%) |

| Others | 245 (30%) |

| Fall risk score | |

| Grade 1 | 105 (13%) |

| Grade 2 | 348 (42%) |

| Grade 3 | 373 (45%) |

| Location | |

| Hospital room | 553 (67%) |

| Corridor | 107 (13%) |

| Restroom | 58 (7%) |

| Bathroom | 25 (3%) |

| Rehabilitation ward | 16 (2%) |

| Others | 67 (8%) |

| Number of falls | |

| Once | 582 (83%) |

| Twice | 184 (22%) |

| three or more times | 60 (7%) |

| Details | |

| Non-adverse event | 725 (88%) |

| Adverse event | 101 (12%) |

| Suture wound | 92 |

| Fractures | 7 |

| Brain hemorrhage | 2 |

Fig. 1.

Distribution of fall risk score by age category

Table 3.

Comparison of adverse events and non-adverse events

| Variable | Adverse event (n=101) |

Non-adverse event (n=725) |

p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | |||

| Over 80 years of age | 32 (19%) | 136 (81%) | <0.01 |

| Female | 42 (11%) | 330 (89%) | n.s. |

| Psychotropic agent | 3 (9%) | 32 (91%) | n.s. |

| Fall risk score | |||

| Grade 1 | 13 (12%) | 92 (88%) | n.s. |

| Grade 2 | 46 (13%) | 302 (87%) | n.s. |

| Grade 3 | 42 (11%) | 331 (89%) | n.s. |

| Location | |||

| Hospital room | 67 (12%) | 486 (88%) | n.s. |

| Corridor | 13 (12%) | 94 (88%) | n.s. |

| Restroom | 7 (12%) | 51 (88%) | n.s. |

| Bathroom | 5 (20%) | 20 (80%) | n.s. |

| Rehabilitation ward | 3 (19%) | 13 (81%) | n.s. |

| Others | 9 (13%) | 58 (87%) | n.s. |

| Number of falls | |||

| Once | 55 (9%) | 527 (92%) | n.s. |

| Twice | 32 (17%) | 152 (83%) | 0.02 |

| Three or more times | 14 (23%) | 46 (77%) | <0.01 |

| Footwear | |||

| Shoes | 47 (11%) | 374 (89%) | n.s. |

| Slippers | 25 (19%) | 108 (81%) | <0.01 |

| Others | 29 (11%) | 243 (89%) | n.s. |

Table 4.

Relationship between fall risk score and incidence of fall.

| Fall risk score | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | |

| Number of falls (n) | 105 | 348 | 373 |

| Number of inpatients (n) | 23,332 | 20,833 | 4,894 |

| Incidence of fall | 0.5% | 1.7% | 7.6% * |

*p<0.05 by Kruskal-Wallis test

Table 5.

Risk factors for adverse events in a multivariate logistic model

| Characteristic | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age over 80 years | 1.65 | 1.03–2.64 | 0.039 |

| Number of falls | |||

| 2≧times | 1.18 | 0.68–1.82 | 0.654 |

| 3≧times | 1.78 | 1.04–3.08 | 0.036 |

| Wearing slippers | 1.72 | 1.05–2.83 | 0.033 |

95% CI: 95% confidence intervals

DISCUSSION

In our hospital, a clinical error or adverse event is submitted as an incident or accident report, regardless of whether it results in harm to a patient or not. A web-based reporting system is used to maintain anonymity and produce a blame-free system. Although there may be unreported incidents and the actual number of falls might be more than the number of reports, this approach facilitates easy access for reporting, a shorter data entry time, better legibility of reports, and immediate information sharing among hospital staff. All reports are submitted to the patient safety management office for analysis, and these reports lead to measures for future improvements.

Accidental fall is a common health problem in older adults,2,6) and the incidence of falls increases with age.4,7) Injuries occur in approximately half of falls and 10% lead to serious injuries such as fracture, head injuries or injuries to the joint.8) In hospital, falls are mostly reported as common adverse events accounting for 20–30% of all incident reports.9) The subsequent need for longer hospitalization is a cost burden to society.4,5,10) In our series, age over 80 was significantly associated with adverse events. All of these reasons indicate the need to prevent older people from falling.

At the time of admission of the patients in this study, our hospital working group had already introduced several measures for fall prevention, such as frequent evaluation using the fall assessment score sheet and raising awareness of fall risk for the patient and their family. Using a mattress laid on the floor to reduce the chance of injury when a fall occurs in patients at high risk, and careful review of medications such as hypnotics and psychotropic drugs were also performed. Patients considered to be at high risk of falls were usually placed in a room near the nurses’ station with a sensor at the bedside. Regarding the time of occurrence of falls, our results are consistent with a previous report showing that falls occur most commonly during night hours in patients more than 70 years of age.3) Various factors may be involved in the higher incidence of falls observed in older patients. The reduced number of ward staff at night may lower vigilance over high risk patients. Lights in patients’ rooms are normally switched off at night and this may restrict the vision of patients when they get up to use the toilet. In particular, older patients have generally higher rates of use of hypnotic agents, which can further elevate the risk of falls.

In our prospective observation based on incident reports, we confirmed a higher incidence of falls in those classified in the highest risk category (Grade 3). We believe that the results demonstrated the utility of the fall assessment sheet used in our acute settings. However, some “false negative” patients, who were categorized as having lower risk (Grade 1) but eventually fell, were included in the current assessment. Therefore, further optimization of the current assessment may be desired. The rate of adverse events caused by falls was 12%, which is similar to that in previous reports.11) Education of patients and ward staffs as a part of routine clinical practice may reduce the incidence of falls and related injuries, thus should be incorporated into conventional fall prevention programs.9)

The present results confirm the utility of the assessment scale in screening patients at potential risk of falls. We are now introducing a system to identify patients at higher risk of falls using a wristband with a color identification that can easily be recognized by all medical staffs at the time of contact with patients. In addition, in our series, wearing slippers was significantly associated with adverse events. Slippers are not recommended as footwear due to their loose fit while walking, and shoes with an appropriate fit to the feet, such as athletic shoes and rehabilitation shoes, are recommended on admission. We plan to evaluate the preventive effects of these interventions in a future study.

In summary, the results of this study indicated that incident falls occurred in 1.7% of all hospitalized patients during a one-year period, and adverse events occurred in 12% of the fall cases. Development of a program for fall prevention based on optimal screening of high risk patients and examination of its validity for reducing the incidence of falls and related negative consequences are subjects for future research.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the staffs of Department of Quality and Patient Safety at Nagoya University Hospital

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

REFERENCES

- 1).Sakamoto K, Nakamura T, Hagino H, Endo N, Mori S, Muto Y, et al. Report on the Japanese Orthopaedic Association’s 3-year project observing hip fractures at fixed-point hospitals. J Orthop Sci, 2006; 11: 127–134. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2).Fine W. An analysis of 277 falls in hospital. Gerontol Clin, 1959; 1: 292–300.

- 3).Alexander BH, Rivara FP, Wolf ME. The cost and frequency of hospitalization for fall-related injuries in older adults. Am J Public Health, 1992; 82: 1020–1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4).Grisso JA, Schwarz DF, Wishner AR, Weene B, Holmes JH, Sutton RL. Injuries in an elderly inner-city population. J Am Geriatr Soc, 1990; 38: 1326–1331. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5).Nordell E, Jarnlo GB, Jetsén C, Nordström L, Thorngren KG. Accidental falls and related fractures in 65–74 year olds: a retrospective study of 332 patients. Acta Orthop Scand, 2000; 71: 175–179. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6).Mathers LJ, Weiss HB. Incidence and characteristics of fall-related emergency department visits. Acad Emerg Med, 1998; 5: 1064–1070. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7).van Weel C, Vermeulen H, van den Bosch W. Falls, a community care perspective. Lancet, 1995; 345: 1549–1551. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8).Hill AM, McPhail SM, Waldron N, Etherton-Beer C, Ingram K, Flicker L, et al. Fall rates in hospital rehabilitation units after individualised patient and staff education programmes: a pragmatic, stepped-wedge, cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet, 2015; 385: 2592–2599. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9).Rizzo JA, Friedkin R, Williams CS, Nabors J, Acampora D, Tinetti ME. Health care utilization and costs in a Medicare population by fall status. Med Care, 1998; 36: 1174–1188. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10).Imagama S, Ito Z, Wakao N, Seki T, Hirano K, Muramoto A, et al. Influence of spinal sagittal alignment, body balance, muscle strength, and physical ability on falling of middle-aged and elderly males. Eur Spine J, 2013; 22: 1346–1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11).Banba Y, Nagai S, Yamamoto K. A clinical study on falls in university hospital. Higashi Nihon Seisaikaishi, 2009: 21; 525–530. (in Japanese)