Abstract

The discovery of monolayer superconductors bears consequences for both fundamental physics and device applications. Currently, the growth of superconducting monolayers can only occur under ultrahigh vacuum and on specific lattice-matched or dangling bond-free substrates, to minimize environment- and substrate-induced disorders/defects. Such severe growth requirements limit the exploration of novel two-dimensional superconductivity and related nanodevices. Here we demonstrate the experimental realization of superconductivity in a chemical vapour deposition grown monolayer material—NbSe2. Atomic-resolution scanning transmission electron microscope imaging reveals the atomic structure of the intrinsic point defects and grain boundaries in monolayer NbSe2, and confirms the low defect concentration in our high-quality film, which is the key to two-dimensional superconductivity. By using monolayer chemical vapour deposited graphene as a protective capping layer, thickness-dependent superconducting properties are observed in as-grown NbSe2 with a transition temperature increasing from 1.0 K in monolayer to 4.56 K in 10-layer.

Two-dimensional superconductors will likely have applications not only in devices, but also in the study of fundamental physics. Here, Wang et al. demonstrate the CVD growth of superconducting NbSe2 on a variety of substrates, making these novel materials increasingly accessible.

Introduction

Monolayer superconductors provide ideal models for investigating superconductivity in the two-dimensional (2D) limit, as well as superconductor-substrate interplay1–5. Strong enhancement of the transition temperature (T c) has been reported in the monolayer FeSe/SrTiO3 system6, 7, which indicates that 2D ultra-thin films have the potential to be high-T c superconductors. However, the superconductivity in most monolayers (Pb8, 9, In8, 10, FeSe6) only survives on certain substrates, probably due to particular interface bonds6, 8. Monolayer NbSe2, has recently been recognized as an intrinsic monolayer superconductor, due to the occurrence of superconductivity without the need of a special substrate4. NbSe2 crystallizes in the same layered hexagonal structure as 2H-MoS2, where the niobium atoms sit at the center of trigonal selenium prisms. Compared with the bulk, 2D NbSe2 exhibits significantly different properties arising from reduced dimensionality, as exemplified by the observation of Ising superconductivity11, quantum metallic state12, and strong enhancement of charge density wave order4.

Defects in an ultrathin superconductor are known to be a critically detrimental factor to intrinsic 2D superconductivity13, 14. Monolayer ambient-sensitive15, 16 NbSe2 is predisposed to receive defects from the substrate and ambient environment. Therefore, the growth of superconducting NbSe2 monolayers is a great challenge. Though superconducting NbSe2 layers can be mechanically exfoliated from bulk NbSe2 crystals, it is not a scalable method. Also, the thickness and size of exfoliated NbSe2 flakes cannot be controlled. In the past few years, chemical vapour deposition (CVD) has been widely employed to synthesize ultrathin semiconducting transition metal dichalcogenides (TMDs) such as MoS2 and WSe2 17–24. Recently, NbSe2 multilayers were prepared by selenizing pre-deposited Nb2O5 films. However, none of the prepared NbSe2 was found to be superconducting25, 26, probably due to the large concentration of defects created during growth. Currently, superconducting NbSe2 monolayers can only be grown by molecular beam epitaxial (MBE) under ultrahigh vacuum (UHV) and on a dangling bond-free graphene or h-BN substrate3, 27, in order to minimize environment- and substrate-induced disorders/defects. However, MBE is expensive to perform because it requires a high-priced apparatus and a UHV environment. Furthermore, MBE growth of NbSe2 is only available on specific graphene and h-BN substrates3, 27, and the individual domain size is < 1 µm3, 27. Therefore, it is desirable to develop a facile growth method to produce high-quality superconducting NbSe2 layers.

In this work, we report the growth of the monolayer superconductor NbSe2 at ambient pressure on a variety of substrates. Atomic-resolution annual dark-field scanning transmission electron microscope (ADF-STEM) imaging reveals the atomic structure of the intrinsic defects in the as-grown monolayer NbSe2 crystal, such as point defects and grain boundaries, and confirms the low concentration of defects in both mono- and few-layer regions. Transport data indicate that even low concentration of defects exist in CVD-grown NbSe2, they will not significantly affect the superconducting properties.

Results

Growth of monolayer NbSe2 crystals

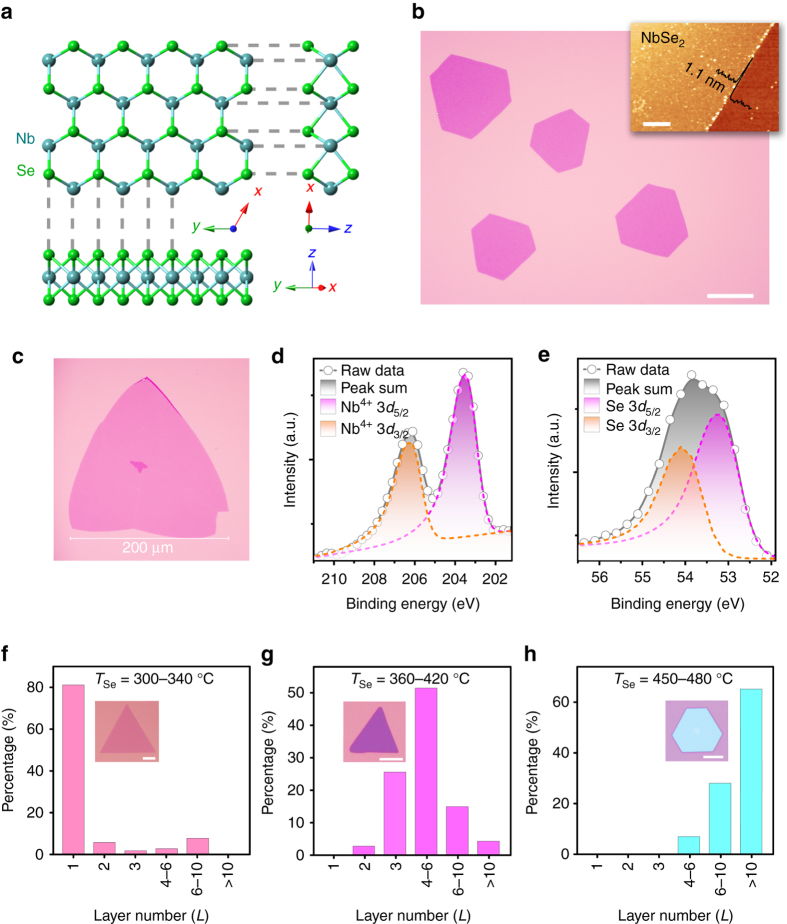

Atomically thin NbSe2 crystals were grown on diverse substrates by ambient pressure CVD in a tube furnace (Supplementary Fig. 1). Partially oxidized niobium powder NbOx (x ≤ 2.5) was chosen as the precursor (Supplementary Fig. 2). Briefly, the powder mixture of NbOx and NaCl was loaded in an alumina boat into the center of a fused quartz tube. Diverse substrates (SiO2/Si, Si(100), quartz, etc.) were placed 1-3 mm above the powder mixture with the polished side faced down. Selenium powder was located at the entrance of the tube furnace, where the temperature was 300–340 °C during growth. Further details of the experiments are provided in the “Methods” section. Figure 1a shows the crystal structure of monolayer NbSe2 viewed from different angles. The as-deposited NbSe2 crystals on SiO2/Si are typically triangular or hexagonal in shape. Figure 1b shows the optical image of uniform hexagonal NbSe2 crystals. A representative atomic force microscopy (AFM) measurement (inset of Fig. 1b) indicates the thickness of the NbSe2 crystal is around 1.1 nm, which corresponds to a monolayer TMD20, 28. As shown in Fig. 1c, the lateral domain size of monolayer CVD-grown NbSe2 can reach 0.2 mm, which is ~102 times as large as that of NbSe2 prepared by MBE (<1 µm)3, 27. In addition to SiO2/Si substrates, our CVD method can deposit NbSe2 layers on arbitrary selenium-resistant crystalline and amorphous substrates, such as silicon (100), quartz, and CVD graphene (Supplementary Fig. 3). Different substrates may result in NbSe2 flakes of varied morphologies (Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4), suggesting that the underlying substrate has an influence on the nucleation and growth of NbSe2. Direct growth on diverse substrates makes it feasible to study the NbSe2-substrate interaction and related properties.

Fig. 1.

Atomic structure, morphologies, and characterizations of NbSe2 crystals. a Ball-and-stick model of monolayer 2H-NbSe2 viewed from three different directions. b Optical image of uniform NbSe2 crystals deposited on a SiO2/Si substrate. Scale bar, 40 µm. A representative AFM image (inset; scale bar, 1 µm) shows the typical thickness is 1.1 nm. c A monolayer NbSe2 crystal with edge length of 0.2 mm. d, e X-ray photoemission spectroscopy (XPS) spectra of the d Nb 3d and e Se 3d peaks from NbSe2 crystals deposited on SiO2/Si substrate. f–h Statistic thickness distributions and representative morphologies (inset) of NbSe2 crystals synthesized with T Se setting at f 300-340, g 360-420 and h 450-480 °C, respectively. Scale bars from inset of f–h are 20, 5 and 5 µm. Thickness of inset crystals of f–h are 1.1, 5.1 and 16.2 nm

The chemical states of the as-grown NbSe2 samples were examined by X-ray photoemission spectroscopy (XPS) (Supplementary Fig. 5). Figure 1d is the Nb 3d core-level spectrum, and the two peaks at 203.4 and 206.1 eV can be assigned to Nb4+ 3d 5/2 and Nb4+ 3d 3/2 of NbSe2 29. The absence of Nb5+ 3d 5/2 and Nb5+ 3d 3/2 peaks at higher binding energy (from 207.3 to 211.0 eV) indicates that the sample was not oxidized30. The Se 3d core levels spectrum can be fitted with Se 3d 5/2 (53.2 eV) and Se 3d 3/2 (54.1 eV) peaks in agreement with the spectra of NbSe2 (Fig. 1e)29, 30. Furthermore, the absence of Na 1s and Cl 2p peaks suggests that as-grown NbSe2 was not contaminated by the NaCl precursor (Supplementary Fig. 6).

Tuning the thickness of NbSe2 layers

In addition to producing monolayer NbSe2, the proposed CVD method is also capable of acquiring NbSe2 crystals with different thicknesses from 1.1 to 16 nm, which will be useful for investigating the thickness-dependent properties such as superconductivity, charge–density-wave order and their interplay in the 2D system. The NbSe2 layer thickness was found to be sensitive to the heating temperature of selenium source (T Se). A portable thermocouple thermometer was used to measure the selenium temperature during sample growth. Figure 1f-h shows the thickness distribution statistics and representative morphologies (inset of Fig. 1f-h and Supplementary Fig. 7) of NbSe2 crystals grown with T Se of (f) 300–340, (g) 360–420, and (h) 450–480 °C, respectively, while keeping all other growth parameters identical. Notably, the average thickness of obtained NbSe2 increased with T Se. Monolayer NbSe2 crystals were obtained only when selenium was heated to 300–340 °C. In our experimental set-up, relatively higher T Se will induce a higher flow rate of the selenium vapour. Therefore, these results indicate that the thickness of NbSe2 films highly relies on the flow rate of the selenium vapour. Supplementary Fig. 8 shows AFM images of NbSe2 crystals with different thicknesses up to 16.2 nm. Raman spectra of the as-grown crystals show two characteristic peaks of NbSe2 (Supplementary Fig. 9), including the in-plane E2g mode at about 250 cm−1 and the out-of-plane A1g mode at about 225 cm−1. The broad feature at about 180 cm−1 is described as a soft mode because of its frequency behavior with temperature4, 31. Thickness dependence of the Raman spectra of NbSe2 is also shown in Supplementary Fig. 9. For monolayer NbSe2, the Raman intensity of both A1g and E2g are very weak at room temperature. With the sample thickness increases, the intensity of A1g and E2g increase significantly.

Structural characterization

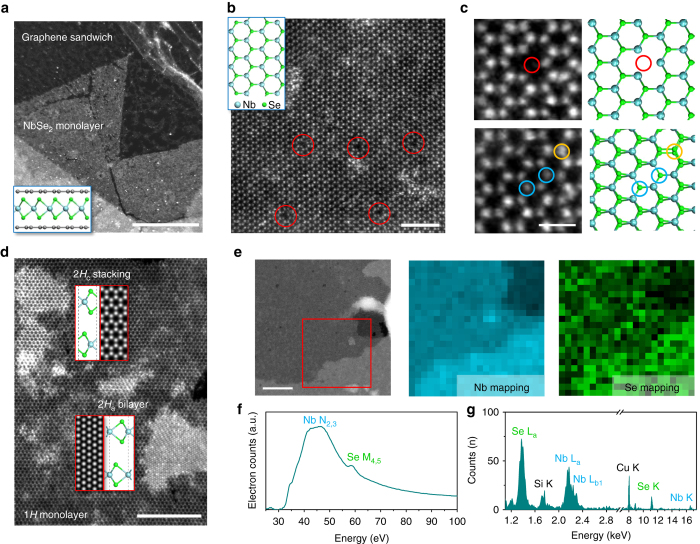

In order to examine the quality of the as-grown 2H-NbSe2 atomic layers, the atomic structure and the chemical composition of the NbSe2 layers were characterized by atomic resolution ADF-STEM imaging, electron energy-loss spectroscopy (EELS) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometry (EDX). Since a bare NbSe2 monolayer film is sensitive to the ambient environment, we transferred the NbSe2 flakes grown on SiO2 substrate with graphene encapsulation (see “Methods” section), constructing a graphene/NbSe2/graphene sandwich structure for STEM imaging. Such structures have been demonstrated to be effective in protecting sensitive monolayer materials from being oxidized32. Figure 2a shows a low magnification ADF-STEM image of a large area of monolayer NbSe2 sandwiched by graphene (schematic shown in the inset), where little oxidization is observed. Figure 2b shows a zoom-in image of the same area with atomic resolution, displaying the hexagonal atomic lattice of alternating bright and dark spots, which corresponds, respectively, to the Se2 and Nb atomic columns as indicated in the atomic model, confirming its hexagonal phase. Diselenium vacancy can be directly visualized by their distinguishable contrast within the image, as highlighted by the red circles. Since the STEM image contrast is directly related to the atomic number and the number of atoms of the imaged species, more types of intrinsic point defects can be identified by carefully examining the image contrast of each atomic column. Figure 2c shows the atomic resolution image of three major types of point defects found in the monolayer NbSe2 film, which are diselenium vacancy (, red), monoselenium vacancy (VSe, blue), and anti-site defect where a Se2 column replaces the Nb (yellow). These intrinsic point defects are similar to those found in MoS2 and MoSe2 with the same hexagonal phase33, 34 grown by CVD method. We can therefore calculate the defect concentration in certain area by counting the number of point defects. The defect concentration in Fig. 2b is estimated to be ~0.18 nm−2, which is similar to the case in mechanical exfoliated monolayer materials35, demonstrating the sufficiently low defect concentration in the film grown by our CVD method. The defect concentration is similar in multiple layer of NbSe2, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 10.

Fig. 2.

ADF-STEM images, EELS, and EDX characterizations of the as-synthesized NbSe2 atomic layers. a A low magnified annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscope (ADF-STEM) image showing a large region of monolayer NbSe2 encapsulated by the graphene sandwich. The schematic is shown in the inset. b Atomic resolution ADF-STEM image of the hexagonal NbSe2 lattice. Diselenium vacancies are highlighted by red circles. The inset of panel b shows the structural model of 2H-NbSe2, with cyan and green color indicating Nb and Se atoms, respectively. c Different point defects in monolayer NbSe2 and their atomic models. Diselenium vacancy, monoselenium vacancy, and anti-site defect SeNb are highlighted by red, blue, and yellow circles, respectively. d Atomic resolution ADF-STEM image of two bilayer islands in NbSe2, showing the coexistence of 2H a and 2H c stacking sequence. The insets are corresponding atomic models and simulated STEM images. e STEM image of a large region of NbSe2 used for the collection of electron energy-loss spectroscopy (EELS) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometry (EDX) spectra. The collected region is highlighted in red square. Nb and Se EELS mapping are provided next to it. f Typical EELS and g EDX spectra of the region shown in e. The Cu signal in the EDX spectra comes from the Cu grid. Scale bars, 500 nm (a), 2 nm (b), 0.5 nm (c), 5 nm (d), 50 nm (e)

We further study the stacking sequence in the CVD-grown NbSe2 sample. Figure 2d shows two stacking orders that coexist in the bilayer region. While the lower bilayer is confirmed to be in 2H a stacking, which is a stacking type commonly found in bulk NbSe2, where Nb atoms are aligned to each other between the layers (atomic model in the inset), the upper bilayer is revealed to be in 2H c stacking, similar to the 2H stacking in MoS2. This is further evidenced by the equal intensity of each atomic column in the hexagonal rings, suggesting all the Nb atoms are aligned with the Se2 columns between the layers. Nevertheless, we found the dominating stacking in bilayers is the 2H a stacking phase. This result implies that, though 2H c stacking is rarely seen in bulk, it can still form in the CVD process presumably due to the weak van der Waal interlayer interaction, which can be overcome by the rapid nucleation process. EDX and EELS were used to identify the chemical constituents of the as-grown layers. Figure 2e shows the region that is used to perform the EDX and EELS experiment. Both EDX and EELS unambiguously show the as-grown NbSe2 film only contains Nb and Se without the presence of any other impurities (Fig. 2f, g). Similar defect and stacking structures are also observed in the NbSe2 layers that are directly grown on graphene substrate, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 11.

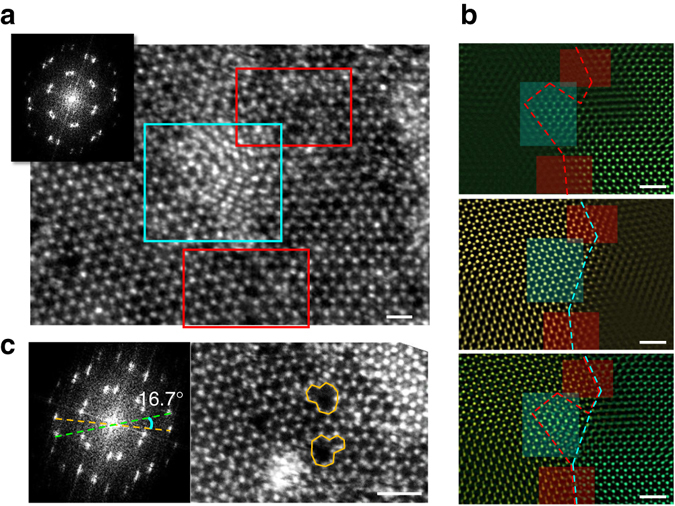

Due to the protection of the graphene sandwich structure, we were able to directly observe the grain boundary structure in the air-sensitive NbSe2 monolayer grown on SiO2/Si by CVD method. Figure 3a displays a tilted grain boundary with a small misorientation angle (about 11°, determined by fast Fourier transform (FFT) in the inset). Interestingly, we found that two types of grain boundary structures coexist, as highlighted by different colored rectangles. The red region indicates the boundary that is atomically sharp, where two domains connects by distorted polygons to accommodate the strain due to the misorientation. The blue region represents another type of boundary, where the two domains overlap with each other, forming a vertically stacked structure. This is further evidenced by the selected FFT-filtered image shown in Fig. 3b, in which the two domains are separated according to the misorientation angles. Although both types of boundaries have been reported previously36–38, it is commonly believed that only one of them can be formed depending on the dynamic energy between the growing frontiers of the misoriented domains during the growth process. The coexistence of both types in a single grain boundary structure suggests the formation energy between these two types of structures (atomically sharp and vertically stacked) is similar in NbSe2, where their co-growth can be induced by local fluctuation of the growing conditions. Figure 3c shows a similar tilted grain boundary without overlapping regions nearby. The ideal five-seven dislocation pairs are found periodically embedded along the grain boundary (highlighted by orange outline), which is similar to the case of other TMD materials34, 37 and consistent with the theoretical predictions39. In contrast, the polygons are found to be more distorted and did not have a periodic distribution when the overlapping boundary is nearby, as shown in the red rectangular regions in Fig. 3a. This may be due to the alternation of the local strain profile in the atomically sharp grain boundary region induced by the overlapping area, which leads to the random formation of distorted polygons to release the inhomogeneous strain. These results reveal the local atomic structure of the grain boundaries, for the first time, in air-sensitive monolayer NbSe2 which is hard to observe due to its easy oxidization without any protection.

Fig. 3.

ADF-STEM images of the grain boundary in monolayer NbSe2. a A tilted grain boundary with misorientation angle of 11°. Both atomically sharp lateral interconnected (red rectangle) and vertically stacked (blue rectangle) boundary regions are found to coexist. The inset shows the fast Fourier transformation (FFT) of the image. The distorted polygons are also highlighted in the red rectangle. Scale bar, 0.5 nm. b Selected FFT-filtered image of the two domains and their overlap images. The overlapped image confirms the coexistence of the two types of grain boundaries. Scale bar, 1 nm. c Similar tilted grain boundary without an overlapping region nearby. The orange lines indicate the five-seven dislocation pairs, which is consistent with the theoretical predictions of the grain boundary structure. Scale bar, 1 nm

Transport properties of mono- and few-layer NbSe2

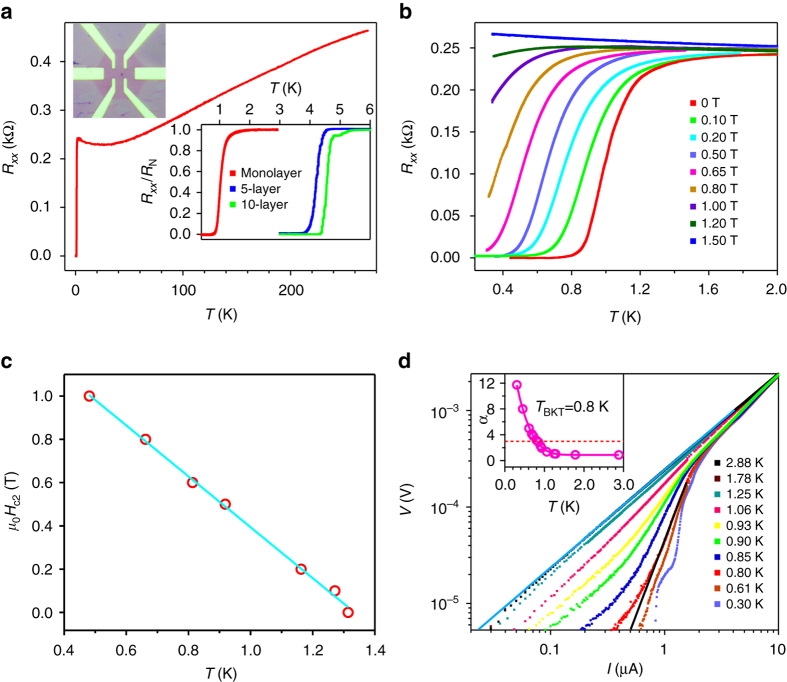

To further characterize the quality and dimensionality of as-grown NbSe2 crystals, a low-temperature transport experiment was carried out on Hall-bar devices. Because of its air sensitivity15, ultrathin NbSe2 was first covered with a continuous monolayer graphene film before device fabrication (see “Methods” section). Figure 4a shows the temperature T dependence of longitudinal resistance R xx for sample A—a representative monolayer NbSe2 device (see Supplementary Note 1 and Supplementary Fig. 12 for more devices and data) at zero magnetic field. Consistent with previous studies3, 11, 12, the sample shows a metallic behavior (dR/dT > 0) at high temperatures. At T onset = 1.5 K, R xx begins to decrease sharply and drops to zero at T zero = 0.8 K, indicating the occurrence of superconductivity. Additionally, we find the superconducting transition in our high-quality NbSe2 crystals can be tuned by changing the sample thickness. The lower right inset of Fig. 4a displays the normalized resistance R xx/R N as a function of temperature for NbSe2 with different thickness. It is evident that the superconducting transition critical temperature T c (0.5R N) can be tuned from 4.56 K for 10-layer, 4.2 K for 5-layer, to 1.0 K for monolayer. Due to its sensitivity to moisture and oxygen, even when protected by graphene, the superconductivity of NbSe2 sample degrades with increasing ambient exposure (Supplementary Fig. 13 and Supplementary Table 1), which is discussed in Supplementary Note 2.

Fig. 4.

Superconductivity in monolayer NbSe2 devices. a Temperature dependence of the longitudinal resistance R xx for sample A—a monolayer NbSe2 device. Upper left inset: Optical image of a typical graphene protected monolayer NbSe2 device. Lower right inset: Superconductivity in monolayer, 5-layer and 10-layer NbSe2 devices. b Superconductivity of sample A in different magnetic fields. c Temperature dependence of the upper critical field H c2. The solid line is the linear fit to H c2. d Voltage–current (V-I) characteristic at different temperatures on a logarithmic scale. The solid blue line indicates the Ohmic behavior at high temperature. The solid black line represents the expected V∝I 3 behavior at the Berezinskii-Kosterlitz-Thouless (BKT) transition. The inset shows the temperature-dependent exponent deduced from the power-law behavior, V∝I α. As indicated by the red dashed line, α approaches 3 at T = 0.8 K

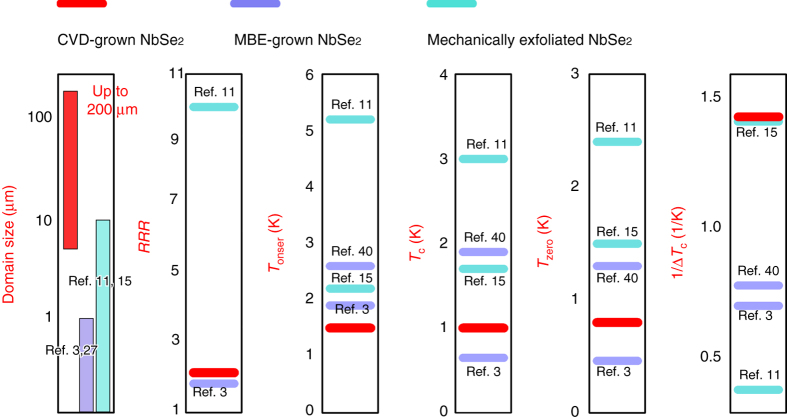

To compare the quality of the monolayer NbSe2 prepared with different methods, the residual resistance ratio (defined as the ratio of the room temperature resistance R 300 K to the normal-state resistance R N) RRR, the superconducting transition onset temperature T onset, the critical temperature T c (0.5RN), the zero-resistance temperature T zero, and the inverse of the superconducting transition width 1/ΔT c are summarized in Fig. 5. It is noted that our CVD-grown monolayer NbSe2 has a RRR = 2.0 very close to the reported value for MBE-grown NbSe2 3, but the CVD sample has a T zero (0.8 K) almost two times as high as that of MBE NbSe2 3. Though a much higher zero-resistance temperature T zero = 1.3 K was reported in Se-capped MBE-grown monolayer NbSe2, however, the resistance did not really drop to zero40. Besides, the ΔT c in the CVD-grown sample is only 0.7 K, which is superior to all reported MBE NbSe2 3, 40 and comparable to the best record in mechanically exfoliated samples15. The above data indicate that the CVD-grown NbSe2 samples are high quality.

Fig. 5.

Comparison of the superconducting performance of monolayer NbSe2 prepared by CVD and other methods. From left to right: domain size, residual resistance ratio RRR, T onset, T c (0.5 RN), T zero, and 1/ΔT c for monolayer NbSe2 samples prepared with different methods

Figure 4b shows the temperature and field dependence of R xx for sample A (see Supplementary Note 1 for more devices and data) with the field perpendicular to the sample plane. Under a magnetic field, the critical temperature T c is defined by where the resistance is 90% of the normal state value R N. With increasing the strength of magnetic field B, T c shifts to lower temperatures. Finally, the superconductivity is completely suppressed with a magnetic field of about 1.5 T at T = 0.3 K. We summarize the H c2-T c phase diagram, where H c2 is the upper critical field, in Fig. 4c and find a linear relationship between H c2 and T c, which is a characteristics of 2D superconductors11–13 and can be explained by the standard linearized Ginzburg-Landau (GL) theory41, , where (0) is the zero-temperature GL in-plane coherence length and is the magnetic flux quantum. As shown in Fig. 4c, a linear fit between H c2 and T c yields (0) = 18 nm (see Supplementary Note 3 and Supplementary Fig. 14 for more transport data of NbSe2 grown on graphene substrate), which is about twice of the bulk value16. Based on the normal state resistance R N and carrier density n s as determined by Hall measurement (Supplementary Note 4 and Supplementary Fig. 15), the mean free path l m = 1.3 nm can be obtained, smaller than that in exfoliated sample12. On the other hand, the normal state sheet resistance R s = 727 Ω (taken at T onset = 1.5 K) is much smaller than the quantum resistance R q = h/4e 2 ≈ 6.45 kΩ, where e is the electron charge and h is Planck’s constant, above which a disorder-induced superconductor-insulator transition emerges42. The above discussions indicate that our sample is in the low-disorder regime11, 13, 40.

For a 2D superconductor with the thickness d < (0), the superconducting phase transition is expected to be of the Berezinskii-Kosterlitz-Thouless (BKT) type43, 44. Figure 4d shows voltage–current (V-I) behavior as a function of temperature on a log-log scale. The V-I relations change from a linear to a power-law dependence, V∝I α at T c (0.5R N), which is consistent with expectations for a 2D superconductor based on the theoretical model of the BKT transition. In the inset of Fig. 4d, we plot the exponent α vs. T, which is extracted from the slope of V-I traces. The BKT transition temperature T BKT is estimated to be 0.8 K from where α = 3 interpolates. The above data confirm that monolayer NbSe2 exhibits the characteristics of a true 2D superconductor.

Discussion

The developed CVD growth technology has enabled the realization of superconductivity in non-UHV grown monolayer materials. Our results also provide a comprehensive understanding of the defect structure, superconducting performance as well as the influence of ambient-induced defects on superconductivity of NbSe2. It is evident that even though low concentrations of selenium vacancy-related defects remained in the CVD-grown NbSe2, they will not significantly affect the superconducting properties. Our facile CVD technology not only provides an excellent platform for the investigation of many fascinating properties of NbSe2, but also holds promise for large-scale synthesis of 2D superconducting NbSe2 films for potential device applications. Future developments may also include investigation and understanding of NbSe2-substrate interplay and related novel properties, inspired by the research on 2D high-T c Fe-chalcogenide superconductors6, 7, 45 (more discussion in Supplementary Note 5). More recently, monolayer NbSe2 was suggested as a candidate for realizing topological superconducting phase and engineering Majorana fermions46, 47. Therefore, the present work offers possibilities for the study of topological physics.

More importantly, our work indicates that a UHV environment is not necessarily required for the growth of monolayer superconductors. In our salt-assisted CVD synthesis of NbSe2, the role of salt is particularly important as no nucleation of NbSe2 can be observed without salt. It is noted that all niobium oxides have melting points above 1510 °C, which make them difficult to vaporize and react with selenium in the CVD process. The products of reactions between molten salts and metal (Mo48, W28, and Nb49) oxides have been investigated by several groups and found to be metal oxychlorides, which have much lower melting points compared with corresponding metal oxides28, 48, 49. Thus, it is suggested that in our CVD process, NaCl reacts with niobium oxides to give volatile niobium oxychloride28, therefore increasing the vapour pressure of precursor and facilitating the growth of NbSe2. With the proposed salt-assisted CVD method, a number of other 2D and even monolayer superconductors (2H-TaS2, 2H-TaSe2, 1T-TiSe2, and 1T-CuxTiSe2, etc.) could be synthesized by substituting niobium oxides with corresponding metal oxides precursors. Considering that most of the mentioned monolayers have never been synthesized (even by MBE) and investigated, the new growth technology will enrich the research field of 2D TMDs superconductivity greatly.

Methods

Atomically thin NbSe2 crystals synthesis

We used partially oxidized niobium powder NbOx (x ≤ 2.5) as precursor for growing NbSe2. In the first step, 5 g niobium powder (99.8%, 325 mesh, Alfa Aesar) was loaded into a both-ends-opened quartz tube equipped in a tube furnace. The niobium powder was ignited when furnace was heating to about 680 °C. After 1 min combustion, the niobium powder was rapid cooled to room temperature by moving it to cold zone. X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis (Supplementary Fig. 2) indicated the obtained power consisted mainly of Nb, Nb2O5, and NbO.

Ambient pressure CVD growth of NbSe2 was conducted in a 2-inch outer diameter fused quartz tube heated by a Lindberg/Blue M (HTF55322C) split-hinge furnace. Supplementary Fig. 1 shows the set-up of the CVD reaction chamber. The partially oxidized Nb powders NbOx (0.7 g) together with NaCl powders (0.1 g) were placed in an alumina boat located in the center of the furnace. 285 nm SiO2/Si or other substrates were placed 1-3 mm above the powder mixture with the polished side faced down. Selenium powder (2 g) (99.5%, Sigma-Aldrich) was placed at the upstream of the quartz tube, where the temperature ranges from 300 to 460 °C during the reaction. 120 sccm (cubic centimeters per minute) Ar and 24 sccm H2 are used as carrier gases. The furnace is heated to 795 °C in 16 min and maintained at that temperature for 13 min to allow the synthesis of NbSe2 layers. The furnace was naturally cooled to 680 °C without changing the carrier gases. Then the top cover of the furnace was opened to allow fast cooling of the sample, with carrier gases switched to 250 sccm Ar and 4 sccm H2.

Device fabrication and transport measurements

For fabricating ultrathin NbSe2 devices, large-area monolayer CVD graphene was used to cover and protect the thin NbSe2 deposited on SiO2/Si. First, a rectangular frame consisted by adhesive tape was attached to the poly (methyl methacrylate) (PMMA)-coated graphene grown on Cu foil50. Then PMMA/graphene was detached from the Cu substrate by a bubbling transfer method. The PMMA/graphene was rinsed in DI water for several times and then dried in air. Second, the PMMA/graphene film was directly attached to the NbSe2 on SiO2/Si substrate in an Ar-filled glove box, with the help of a drop of isopropanol added between. PMMA was then removed in acetone to form the graphene/NbSe2 stacks. Finally, a fresh film of PMMA was deposited on the prepared graphene/NbSe2 layers, by spin-coating at 3 K rpm for 1 min. The PMMA film was cured at 140 °C for 6 min in an Ar glove box. Hall bar device was made by electron-beam lithography and the contact metal (5 nm Cr/50 nm Au) was fabricated by electron-beam deposition.

The transport experiment is carried out in a top-loading helium-3 cryostat in a superconducting magnet. An AC probe current I ac = 10 nA at 30.9 Hz is applied from the source to the drain. Then a lock-in amplifier monitors the longitudinal R xx through two additional electrical contacts.

Fabrication of graphene/NbSe2/graphene sandwich cell for STEM imaging

First, mono- and few-layer NbSe2 crystals were grown on 285 nm SiO2/Si substrates. Second, with the same method described earlier in the device fabrication part, a continuous monolayer CVD graphene film was placed on top of the chip to form a graphene/NbSe2-stacked heterostructure. Third, a thin PMMA film was spin-coated and cured on the chip, and then the PMMA/graphene/NbSe2 film was detached from the SiO2/Si substrate in HF. After rinsed in DI water, it was scooped up by a SiO2/Si chip predeposited with monolayer graphene film to form a PMMA/graphene/NbSe2/graphene structure on SiO2/Si substrate. Fourth, the PMMA/graphene/NbSe2/graphene film was detached from the substrate by etching SiO2 layer in HF. After rinsed in DI water, it was scooped up by a TEM grid. Finally, the graphene/NbSe2/graphene sandwich cell was created by removing PMMA in acetone.

Sample characterizations

XPS spectra were collected on a PHI Quantera II spectrometer using monochromatic Al-Kα (hυ = 1486.6 eV) radiation, and the binding energies were calibrated with C 1s binding energy of 284.8 eV. AFM images were taken using the Asylum Research Cypher AFM in tapping mode. Raman spectra were recorded in vacuum by a Witec system with ×50 objective lens and a 2400 lines per mm grating under 532 nm laser excitation. The laser power was fixed at 1 mW. STEM experiments were performed by a low acceleration voltage JEOL 2100F equipped with Delta correctors and GIF quantum spectrometer.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the Singapore National Research Foundation under NRF RF Award No. NRF-RF2013-08, the start-up funding from Nanyang Technological University (M4081137.070), Tier 2 MOE2016-T2-2-153, MOE2016-T2-1-131 (S), MOE2015-T2-2-007, Tier 1 RG164/15, and CoE Industry Collaboration Grant WINTECH-NTU. The work at IOP was supported by the National Basic Research Program of China from the MOST under the Grant nos. 2014CB920904, 2015CB921101, and 2013CB921702, by the NSFC under the Grant nos. 11174340 and 91421303. J.L. and K.S. acknowledge JST-ACCEL and JSPS KAKENHI (JP16H06333 and P16823) for financial support. Y.C. and T.Y. thank the support of Ministry of Education AcRF Tier 1 RG100/15.

Author contributions

Z.L., G.L., and E.H.T.T. directed the research; H.W. and Z.L. proposed and designed the experiments; H.W. performed the NbSe2 and NbSe2/graphene heterostructure synthesis and did the SEM, AFM, and XPS measurements; X.H., J.C., and G.L. did the superconductivity measurements and data analysis; X.H., C.Z., Q.Z., and F.L. contributed to the device fabrication; J.L. did the STEM measurement and data analysis; Y.C. and H.W. did the Raman measurement; H.W. and J.Z. prepared the STEM sample; P.Y. and X.W. did the XRD measurement; H.H., S.H.T., W.G., K.S., F.M., C.Y., L.L., T.Y., and E.H.T.T. contributed to the results analysis and discussions. H.W., J.L., G.L., and Z.L. co-wrote the paper with input from all authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Hong Wang, Xiangwei Huang and Junhao Lin contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41467-017-00427-5.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Edwin Hang Tong Teo, Email: htteo@ntu.edu.sg.

Guangtong Liu, Email: gtliu@iphy.ac.cn.

Zheng Liu, Email: z.liu@ntu.edu.sg.

References

- 1.Saito Y, Nojima T, Iwasa Y. Highly crystalline 2D superconductors. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2016;2:16094. doi: 10.1038/natrevmats.2016.94. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Qin S, Kim J, Niu Q, Shih C-K. Superconductivity at the two-dimensional limit. Science. 2009;324:1314–1317. doi: 10.1126/science.1170775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ugeda MM, et al. Characterization of collective ground states in single-layer NbSe2. Nat. Phys. 2016;12:92–97. doi: 10.1038/nphys3527. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xi X, et al. Strongly enhanced charge-density-wave order in monolayer NbSe2. Nat. Nano. 2015;10:765–769. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2015.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saito Y, Kasahara Y, Ye J, Iwasa Y, Nojima T. Metallic ground state in an ion-gated two-dimensional superconductor. Science. 2015;350:409–413. doi: 10.1126/science.1259440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ge J-F, et al. Superconductivity above 100 K in single-layer FeSe films on doped SrTiO3. Nat. Mater. 2015;14:285–289. doi: 10.1038/nmat4153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tan S, et al. Interface-induced superconductivity and strain-dependent spin density waves in FeSe/SrTiO3 thin films. Nat. Mater. 2013;12:634–640. doi: 10.1038/nmat3654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang T, et al. Superconductivity in one-atomic-layer metal films grown on Si(111) Nat. Phys. 2010;6:104–108. doi: 10.1038/nphys1499. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sekihara T, Masutomi R, Okamoto T. Two-dimensional superconducting state of monolayer Pb films grown on GaAs (110) in a strong parallel magnetic field. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2013;111:057005. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.111.057005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Uchihashi T, Mishra P, Aono M, Nakayama T. Macroscopic superconducting current through a silicon surface reconstruction with indium adatoms: Si (111)−(7×3)−. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2011;107:207001. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.107.207001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xi X, et al. Ising pairing in superconducting NbSe2 atomic layers. Nat. Phys. 2016;12:139–143. doi: 10.1038/nphys3538. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsen AW, et al. Nature of the quantum metal in a two-dimensional crystalline superconductor. Nat. Phys. 2016;12:208–212. doi: 10.1038/nphys3579. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xu C, et al. Large-area high-quality 2D ultrathin Mo2C superconducting crystals. Nat. Mater. 2015;14:1135–1141. doi: 10.1038/nmat4374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Graybeal JM. Competition between superconductivity and localization in two-dimensional ultrathin a-MoGe films. Phys. B+C. 1985;135:113–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-4363(85)90448-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cao Y, et al. Quality heterostructures from two-dimensional crystals unstable in air by their assembly in inert atmosphere. Nano Lett. 2015;15:4914–4921. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b00648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.El-Bana MS, et al. Superconductivity in two-dimensional NbSe2 field effect transistors. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2013;26:125020. doi: 10.1088/0953-2048/26/12/125020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee Y-H, et al. Synthesis and transfer of single-layer transition metal disulfides on diverse surfaces. Nano Lett. 2013;13:1852–1857. doi: 10.1021/nl400687n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang Y, et al. Controlled growth of high-quality monolayer WS2 layers on sapphire and imaging its grain boundary. ACS Nano. 2013;7:8963–8971. doi: 10.1021/nn403454e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang J-K, et al. Large-area synthesis of highly crystalline WSe2 monolayers and device applications. ACS Nano. 2013;8:923–930. doi: 10.1021/nn405719x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang M, et al. Controlled synthesis of ZrS2 monolayer and few layers on hexagonal boron nitride. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:7051–7054. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b03807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li X, et al. Controlled vapor phase growth of single crystalline, two-dimensional GaSe crystals with high photoresponse. Sci. Rep. 2014;4:5497. doi: 10.1038/srep05497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhou X, et al. Ultrathin SnSe2 flakes grown by chemical vapor deposition for high-performance photodetectors. Adv. Mater. 2015;27:8035–8041. doi: 10.1002/adma.201503873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duan X, et al. Lateral epitaxial growth of two-dimensional layered semiconductor heterojunctions. Nat. Nano. 2014;9:1024–1030. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2014.222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu Y, et al. Controlled scalable synthesis of uniform, high-quality monolayer and few-layer MoS2 films. Sci. Rep. 2013;3:1866. doi: 10.1038/srep01866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim AR, et al. Alloyed 2D metal-semiconductor atomic layer junctions. Nano Lett. 2016;16:1890–1895. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.5b05036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim Y, et al. Alloyed 2D metal–semiconductor heterojunctions: origin of interface states reduction and schottky barrier lowering. Nano Lett. 2016;16:5928–5933. doi: 10.1021/acs.nanolett.6b02893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hotta T, et al. Molecular beam epitaxy growth of monolayer niobium diselenide flakes. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2016;109:133101. doi: 10.1063/1.4963178. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li S, et al. Halide-assisted atmospheric pressure growth of large WSe2 and WS2 monolayer crystals. Appl. Mater. Today. 2015;1:60–66. doi: 10.1016/j.apmt.2015.09.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wertheim G, DiSalvo F, Buchanan D. Site inequivalence in Fe 1+x Nb 3− x Se 10. Phys. Rev. B. 1983;28:3335. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.28.3335. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Boscher ND, Carmalt CJ, Parkin IP. Atmospheric pressure chemical vapour deposition of NbSe2 thin films on glass. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2006;2006:1255–1259. doi: 10.1002/ejic.200500857. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tsang J, Smith J, Jr, Shafer M. Raman spectroscopy of soft modes at the charge-density-wave phase transition in 2 H−Nb Se 2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1976;37:1407. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.37.1407. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nguyen L, et al. Atomic defects and doping of monolayer NbSe2. ACS Nano. 2017;11:2894–2904. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.6b08036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou W, et al. Intrinsic structural defects in monolayer molybdenum disulfide. Nano Lett. 2013;13:2615–2622. doi: 10.1021/nl4007479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lu X, et al. Large-area synthesis of monolayer and few-layer MoSe2 films on SiO2 substrates. Nano Lett. 2014;14:2419–2425. doi: 10.1021/nl5000906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hong J, et al. Exploring atomic defects in molybdenum disulphide monolayers. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:6293. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li X, et al. Two-dimensional GaSe/MoSe2 misfit bilayer heterojunctions by van der Waals epitaxy. Sci. Adv. 2016;2:e1501882. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1501882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Najmaei S, et al. Vapour phase growth and grain boundary structure of molybdenum disulphide atomic layers. Nat. Mater. 2013;12:754–759. doi: 10.1038/nmat3673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van der Zande AM, et al. Grains and grain boundaries in highly crystalline monolayer molybdenum disulphide. Nat. Mater. 2013;12:554–561. doi: 10.1038/nmat3633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zou X, Liu Y, Yakobson BI. Predicting dislocations and grain boundaries in two-dimensional metal-disulfides from the first principles. Nano Lett. 2012;13:253–258. doi: 10.1021/nl3040042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Onishi S, et al. Selenium capped monolayer NbSe2 for two-dimensional superconductivity studies. Phys. Status Solidi B. 2016;253:2396–2399. doi: 10.1002/pssb.201600235. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tinkham, M. Introduction to Superconductivity (Courier Corporation, 1996).

- 42.Fiory A, Hebard A. Electron mobility, conductivity, and superconductivity near the metal-insulator transition. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1984;52:2057–2060. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.52.2057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reyren N, et al. Superconducting interfaces between insulating oxides. Science. 2007;317:1196–1199. doi: 10.1126/science.1146006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Halperin B, Nelson DR. Resistive transition in superconducting films. J. Low Temp. Phys. 1979;36:599–616. doi: 10.1007/BF00116988. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miyata Y, Nakayama K, Sugawara K, Sato T, Takahashi T. High-temperature superconductivity in potassium-coated multilayer FeSe thin films. Nat Mater. 2015;14:775–779. doi: 10.1038/nmat4302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.He, W.-Y., Zhou, B. T., He, J. J., Zhang, T. & Law, K. Nodal topological superconductivity in monolayer NbSe2. Preprint at http://arxiv.org/abs/1604.02867 (2016).

- 47.Zhou BT, Yuan NF, Jiang H-L, Law KT. Ising superconductivity and Majorana fermions in transition-metal dichalcogenides. Phys. Rev. B. 2016;93:180501. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.93.180501. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Manukyan KV, et al. Mechanism of molten-salt-controlled thermite reactions. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2011;50:10982–10988. doi: 10.1021/ie2003544. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gaune-Escard, M. & Haarberg, G. M. Molten Salts Chemistry and Technology (John Wiley & Sons, 2014).

- 50.Li XS, et al. Large-area synthesis of high-quality and uniform graphene films on copper foils. Science. 2009;324:1312–1314. doi: 10.1126/science.1171245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.