Abstract

Aim

To test our hypothesis that initiating therapy with a combination of agents known to improve insulin secretion and insulin sensitivity in subjects with new-onset diabetes would produce greater, more durable reduction in glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) levels, while avoiding hypoglycaemia and weight gain, compared with sequential addition of agents that lower plasma glucose but do not correct established pathophysiological abnormalities.

Methods

Drug-naïve, recently diagnosed subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) were randomized in an open-fashion design in a single-centre study to metformin/pioglitazone/exenatide (triple therapy; n = 106) or an escalating dose of metformin followed by sequential addition of sulfonylurea and glargine insulin (conventional therapy; n = 115) to maintain HbA1c levels at <6.5% for 2 years.

Results

Participants receiving triple therapy experienced a significantly greater reduction in HbA1c level than those receiving conventional therapy (5.95 vs. 6.50%; p < 0.001). Despite lower HbA1c values, participants receiving triple therapy experienced a 7.5-fold lower rate of hypoglycaemia compared with participants receiving conventional therapy. Participants receiving triple therapy experienced a mean weight loss of 1.2 kg versus a mean weight gain of 4.1 kg (p < 0.01) in those receiving conventional therapy.

Conclusion

The results of this exploratory study show that combination therapy with metformin/pioglitazone/exenatide in patients with newly diagnosed T2DM is more effective and results in fewer hypoglycaemic events than sequential add-on therapy with metformin, sulfonylurea and then basal insulin.

Keywords: combination therapy, conventional therapy, durability, glycaemic control

Introduction

Progressive β-cell failure in an insulin-resistant individual is the principal factor responsible for the development and progression of hyperglycaemia in individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) [1]. Hyperglycaemia is the major factor responsible for microvascular complications and every 1% decrease in glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) level is associated with a ~35% decrease in the risk of microvascular complications [2–5]. Maintaining HbA1c at <6.0% prevents the development of retinopathy [4], emphasizing the importance of glycaemic control in T2DM. A major obstacle to maintaining HbA1c levels within the normal range is progressive β-cell failure and hypoglycaemia [2,6], and recent clinical trials have reported that hypoglycaemia is associated with increased mortality risk [6]. This presents a dilemma between lowering HbA1c level to prevent microvascular complications versus minimizing risk of hypoglycaemia. The American Diabetes Association (ADA) recommends ‘lowering HbA1c to <7.0% in most patients and more stringent targets (6.0–6.5%) in selected patients if achieved without hypoglycaemia’ [7].

Metformin is recommended as first-line therapy in patients with T2DM [7]. It lowers HbA1c by inhibiting hepatic glucose production [8,9], but does not prevent β-cell failure [10,11], and after an initial decrease, HbA1c levels rise progressively. Similarly, sulfonylureas, the most common second-line therapy, lack a protective effect on β-cell function [3,10,11].

Thiazolidinediones are potent insulin sensitizers [12] and improve β-cell function [13–17]. Clinical trials have also shown that they achieve durable HbA1c reduction compared with sulfonylureas and metformin [1,10,18,19].

Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists improve β-cell function [20], an effect which lasts for up to 3 years [21], and a single liraglutide injection acutely normalizes β-cell glucose sensitivity in patients with T2DM [22]. Because of the pivotal role of β-cell failure in the development/progression of hyperglycaemia, GLP-1 analogues would be expected to produce durable decreases in HbA1c levels. Consistent with this, a recent clinical trial showed that exenatide was superior to sulfonylureas in achieving durable HbA1c reductions in patients with T2DM over a 4-year period [23]. Importantly, both thiazolidinediones and GLP-1 analogues lower HbA1c levels without increasing hypoglycaemia risk.

β-cell failure is evident long before overt diabetes is diagnosed. We have shown previously that individuals in the upper tertile of normal glucose tolerance (2-h plasma glucose 6.7–7.7 mmol/l (120–139 mg/dl)] have lost over half of their β-cell function compared with those with 2-h plasma glucose <6.1 mmol/l (100 mg/dl). By the time diabetes is diagnosed, people with diabetes have lost >80% of their β-cell function [24]. Although the initial loss of β-cell function is primarily functional, anatomical loss of β-cell mass ensues with progressive duration of the disease; thus, intervention with agents that preserve β-cell function is likely to have a strong positive impact on glycaemic control in subjects with new-onset diabetes who maintain residual β-cell function. We hypothesized that initiation of combination therapy with metformin plus a thiazolidinedione and a GLP-1 receptor agonist, the latter two of which have been shown to improve β-cell function and insulin resistance in subjects with new-onset T2DM [1,13–17], would cause a durable HbA1c reduction without increasing hypoglycaemic risk or causing weight gain. Based on recent results in patients with T2DM with long-standing disease [25,26], aggressive HbA1c-lowering with combination therapy, as in the present study, should be used with caution. The aim of the present study was to compare efficacy and durability of this novel triple therapy approach with that of conventional therapy with metformin followed by sequential addition of sulfonylurea and then basal insulin to maintain HbA1c at ≤6.5% in subjects with new-onset diabetes [7].

Participants and Methods

The present study, the Efficacy and Durability of Initial Combination Therapy for Type 2 Diabetes (EDICT) study, was an open-label, single-centre, randomized controlled trial (clinicaltrials.gov registration no.: NCT01107717) to examine the efficacy, durability and safety of initial triple combination therapy with antidiabetic agents (metformin/pioglitazone/exenatide) that have previously been shown to correct core metabolic defects responsible for T2DM [1] versus those of a conventional therapy approach that focuses on lowering plasma glucose with metformin followed by sequential add-on therapy with sulfonylureas and basal insulin. The EDICT study is a 3-year study, carried out at Texas Diabetes Institute, San Antonio, TX, USA, and the present report is an interim analysis with a mean follow-up of 18.5 months. All baseline measurements will be repeated after 3 years or at the time of treatment failure. Study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio and informed written consent was obtained from all participants before enrolment.

Participants

The participants with T2DM included in this study [age 30–75 years, body mass index (BMI) 24–50 kg/m2] were drug-naïve and recently diagnosed (<2 years) according to ADA criteria; had negative, glutamic acid decarboxylase antibodies, normal liver function/serum chemistries, stable body weight [±3 pounds (1.4 kg) within preceding year] and negative pregnancy tests. Exclusion criteria were haematocrit levels <34%, medications known to affect glucose metabolism, previous treatment with any antidiabetic agent, evidence of diabetic proliferative retinopathy, albumin excretion >300 mg/day and major organ system disease as determined by physical examination, medical history and screening blood tests.

Study Design

Eligible participants were consecutively randomized based on age, sex, BMI, diabetes duration and HbA1c level to receive either initial triple combination therapy with metformin/pioglitazone/exenatide or metformin with sequential addition of glipizide and then basal insulin glargine (conventional therapy) to maintain HbA1c levels at <6.5%. Participants were randomized consecutively and were matched on age, sex, BMI, initial HbA1c level and diabetes duration. There was no limit on the upper value of HbA1c (the range of initial HbA1c was 6.5–14%). Participants with initial HbA1c <9.0% (36% of participants) and HbA1c ≥ 9.0% were evenly randomized to the two arms.

Participants randomized to triple therapy were started on metformin 1000 mg/day, pioglitazone 15 mg/day and exenatide 5 μg twice daily before breakfast and supper. At 1 month, metformin was increased to 2000 mg, pioglitazone to 30 mg and exenatide to 10 μg twice daily. If, at 3 months, HbA1c was >6.5%, pioglitazone was increased to 45 mg. Participants receiving conventional therapy were started on metformin 1000 mg/day. If, at 1 month, fasting plasma glucose (FPG) concentration was >6.1 mmol/l (110 mg/dl), metformin was increased to 2000 mg and glipizide started at 5 mg/day. If, at 2 months, FPG was >6.1 mmol/l (110 mg/dl) or HbA1c was >6.5%, glipizide was increased to 10 mg and then to 20 mg. If, at 3 months, FPG was >6.1 mmol/l (110 mg/dl) or HbA1c >6.5%, glargine insulin was started at 10 units before breakfast, and escalated weekly by 1–5 units (based on FPG and HbA1c levels) to 60 units/day to maintain FPG at <6.1 mmol/l (110 mg/dl).

After 3 months, participants were seen every 3 months. FPG, body weight and HbA1c were measured at each follow-up visit and medication dose was adjusted to maintain FPG at <6.1 mmol/l (110 mg/dl) and HbA1c at <6.5%, unless hypoglycaemia (blood glucose <3.3 mmol/l (60 mg/dl) or symptoms) was present. Hypoglycaemia was defined as blood glucose concentration <3.3 mmol/l (60 mg/dl), with or without symptoms, or hypoglycaemia symptoms that subsided after glucose ingestion. Blood glucose levels were measured by home blood glucose monitoring and verified by the study coordinator on follow-up visits. During each follow-up visit, FPG was measured, records of home-measured glucose values were reviewed, and patients were questioned about symptoms of hypoglycaemia. Severe hypoglycaemia was defined as hypoglycaemia requiring third party assistance.

Overall frequency of hypoglycaemia was calculated as the total number of hypoglycaemic events divided by the number of patient-years of follow-up in each arm; the percentage of participants experiencing hypoglycaemia was calculated as the number of participants experiencing at least a single event divided by number of patients in that arm.

If HbA1c increased to >6.5% on two consecutive visits (3 months apart, to ensure that the deterioration in glycaemic control was genuine and not attributable to transient factors) despite maximum antihyperglycaemic therapy, treatment was defined as having failed for that participant. All baseline studies were repeated in participants with treatment failure at the time of declaration of treatment failure and rescue therapy was started. Rescue therapy was short-acting insulin which was started 4–6 units before each meal and the dose was adjusted based on blood glucose measurements to maintain plasma glucose concentration <7.8 mmol/l (140 mg/dl) 2 h after meals. Rescue therapy in the triple therapy arm was glargine insulin which was started at 6–10 units/day and the dose was adjusted to maintain FPG <6.1 mmol/l (110 mg/dl).

Data Analysis

The primary endpoint was HbA1c difference between participants receiving triple therapy versus conventional therapy. Secondary endpoints included: percentage of participants achieving HbA1c <6.5 and <7.0%; decrease in fasting and postprandial plasma glucose; change in body weight; and rate of hypoglycaemic events.

Because treatment failure was determined by two consecutive HbA1c values measured at 3-month intervals, only randomized participants who received therapy and completed at least 6 months of follow-up were included in the analysis. This allowed participants to receive the maximum treatment dose and thereby provided sufficient time to assess the impact of therapy on two consecutive HbA1c measurements (months 3 and 6). Because rescue therapy was instituted in participants with treatment failure (n = 45 in conventional therapy and n = 15 in triple therapy, see results below), the HbA1c values after starting the rescue therapy could not be included in the analysis. The first HbA1c value to exceed 6.5% was censored and carried forward for analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Values are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (s.e.m.). Two-sided t-tests were used to compare mean differences between treatment arms and the chi-squared test was used to test the significance of discrete variables. Cox’s proportional hazards model was used to estimate the influence of therapy on failure to maintain treatment goals. The model was adjusted for other confounders (age, sex, BMI, disease duration and baseline HbA1c level). To identify predictors of therapy failure (HbA1c > 6.5%), we created a multilogistic regression model, with therapy failure as the dependent variable and age, sex, BMI, disease duration, baseline HbA1c, treatment arm and weight gain as independent variables.

The study was powered to detect a 0.5% (±0.95 standard deviation) HbA1c difference between treatment arms based on the HbA1c decrease in the PROactive study [27]. In the PROactive study, investigators were blinded to pioglitazone therapy and instructed to use any antidiabetic drug to maintain HbA1c at <6.5% in both arms. At study end, participants who received pioglitazone had a 0.5% lower HbA1c than participants who received placebo. Based on this, we assumed that participants who received triple therapy (who received pioglitazone) would achieve a ≥0.5% lower HbA1c than those receiving conventional therapy. We calculated that 76 participants per arm would provide 90% power to detect a 0.5% HbA1c difference between treatment arms at an α value <0.05.

Results

In all, 374 subjects with newly diagnosed T2DM were screened and 249 eligible participants were randomized. A total of 123 participants were randomized to triple therapy and 126 to conventional therapy (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Trial profile.

Of 126 participants randomized to conventional therapy, 11 never received any treatment as they did not return for the follow-up visit to dispense medication and 24 participants did not complete the 6-month follow-up visit (18 participants dropped out before the 6-month visit; 6 participants are active but have yet to complete the 6-month visit). As pre-specified, these 24 individuals were not included in the present analysis. The remaining 91 participants with T2DM were included in the analysis. Of 91, 11 dropped out before completing 24 months of follow-up. Thus, the dropout rate in the conventional therapy arm was 25% [29 (18 + 11)/115 participants].

Of 123 individuals randomized to triple therapy, 17 never received any treatment and 27 did not complete the 6-month follow-up visit (23 participants dropped out before the 6-month visit; 4 participants are active but have yet to complete the 6-month visit). Of the 79 remaining participants with T2DM included in the analysis, 12 dropped out before completing the 24-month visit. The dropout rate in this arm was therefore 33% [35 (23 + 12)/106 participants]. The baseline characteristics of participants included in this analysis did not differ from those who were randomized but did not complete 6-month follow up visit (Table S1 and Figure S1).

The mean ± (s.e.m.) follow-up was 18.1 ± 0.5 and 18.7 ± 0.5 months in the conventional and triple therapy arms, respectively (p = non-significant). Conclusions from the as-treated population were not different from intention-to-treat analysis (Figure S2). Participants in both treatment arms were well matched for age, BMI, diabetes duration and HbA1c (Table 1). Participants were generally obese, had a mean initial HbA1c of 8.6% and a mean diabetes duration of 5.1 months.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of participants randomized to receive conventional therapy and triple therapy.

| Conventional therapy | Triple therapy | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number, n | 91 | 79 | |

| Age, years | 47 ± 1 | 46 ± 1 | n.s. |

| Sex: male, % | 55 | 62 | n.s. |

| Weight, kg | 101.6 ± 2.3 | 101.0 ± 3.4 | n.s. |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 36.4 ± 1 | 36.6 ± 1 | n.s. |

| Diabetes duration, months | 5.1 ± 0.7 | 5.1 ± 0.6 | n.s. |

| HbA1c, % | 8.6 ± 0.2 | 8.6 ± 0.2 | n.s. |

| FPG, mmol/l | 10.5 ± 0.4 | 10.7 ± 0.4 | n.s. |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 129 ± 3 | 132 ± 4 | n.s. |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 79 ± 2 | 79 ± 2 | n.s. |

| Total cholesterol, mmol/l | 10.3 ± 0.3 | 10.3 ± 0.2 | n.s. |

| Triglycerides, mmol/l | 9.7 ± 0.7 | 10.3 ± 0.9 | n.s. |

| HDL cholesterol, mmol/l | 2.4 ± 0.1 | 2.4 ± 0.1 | n.s. |

Data are mean ± s.e.m. unless otherwise indicated.

BMI, body mass index; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; n.s., non-significant.

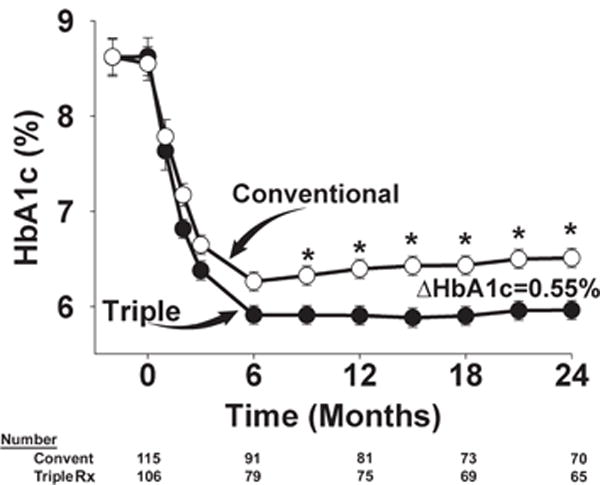

The primary outcome, difference in HbA1c between the two treatment groups, is shown in Figure 2. Baseline HbA1c was identical in both groups (8.6%) and during the first 6 months decreased in both treatment arms. At 6 months, there was a small but significant HbA1c difference (0.2%, p = 0.03) between groups (triple therapy 6.0% vs. conventional therapy 6.2%). After 6 months, HbA1c gradually increased with conventional therapy to 6.5% at 24 months and remained stable at 5.95% with triple therapy; thus, the difference in HbA1c between the two treatments progressively increased with time and was significantly different at 2 years (ΔHbA1c 0.55%; p < 0.0001). At 24 months, the HbA1c decrease in participants with HbA1c levels ≥8.5% (4.1 vs. 3.1%; p = 0.005) and <8.5% (1.5 vs. 0.9%; p = 0.0005) was greater in the triple therapy than in the conventional therapy group.

Figure 2.

Time-related change in glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) in participants receiving conventional (convent) therapy and initial triple combination (Rx) therapy during the 24-month follow-up period. *p < 0.01.

More participants receiving conventional therapy failed to maintain the treatment goal (HbA1c < 6.5%) than did those receiving triple therapy (44 vs. 17%; p = 0.003). Figure 3 shows a Kaplan–Meier plot of time to treatment failure (HbA1c > 6.5%). A total of 40 participants receiving conventional therapy failed to maintain HbA1c at <6.5% at/after 6 months compared with only 13 participants receiving triple therapy (p < 0.0001). Figure S2A shows the change in HbA1c over the 2-year follow-up in participants who received at least 1 month of therapy (i.e. the intention-to-treat analysis), including dropouts, treatment failures (before rescue therapy) and participants who had <6 months of therapy. Figure S2B shows the change in HbA1c in participants who completed 2 years of treatment (without dropouts and incomplete follow-ups). The difference in HbA1c between the triple therapy and conventional therapy groups was virtually identical with both analyses. More participants receiving triple therapy (61%) had HbA1c reduced to the normal range (<6.0%) than those receiving conventional therapy (27%; p < 0.0001). The median HbA1c of participants receiving triple therapy was 5.9% compared with 6.4% for those receiving conventional therapy. More than 90% of participants receiving triple therapy maintained HbA1c at <7.0% versus <75% of participants receiving conventional therapy.

Figure 3.

Kaplan–Meier plot of time to treatment failure, defined as glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) > 6.5%, in the conventional (convent) therapy and triple (Rx) therapy groups (p < 0.001). Cum, cumulative.

In multivariable logistic regression analysis, treatment group was the strongest predictor of risk of failure to maintain the glycaemic goal (HbA1c < 6.5%; Table 2). Participants receiving triple therapy had an 84% lower risk of failing to achieve the glycaemic goal at 2 years compared with participants receiving conventional therapy. Younger age, high initial HbA1c and weight gain were also significant predictors of treatment failure.

Table 2.

Predictors of failure to achieve glycated haemoglogin <6.5% during 24 months of treatment.

| Odds ratio | 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment (triple vs. conventional) | 0.16 | 0.06–0.45 | <0.0001 |

| 10-year increase in age (>40 years) | 0.36 | 0.21–0.62 | <0.0001 |

| Initial HbA1c (1%) | 1.44 | 1.10–1.90 | <0.01 |

| Weight gain during the study (1 kg) | 1.08 | 1.02–1.14 | <0.01 |

CI, confidence interval; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin.

Fasting and Postprandial Glucose

The mean ± s.e.m. baseline FPG levels were similar in the conventional and the triple therapy groups [10.6 ± 0.4 mmol/l (190 ± 7) and 10.7 ± 0.4 mmol/l (192 ± 7); p = non-significant] and decreased rapidly after starting therapy. At 6 months, the decrease in FPG was greater in the triple versus the conventional therapy group [6.6 ± 0.2 mmol/l (118 ± 4) vs. 7.2 ± 0.3 mmol/l (130 ± 5); p = 0.02]. FPG levels decreased further at 2 years in both groups but remained lower in the triple therapy group [5.4 ± 0.2 mmol/l (98 ± 4) vs. 6.4 ± 0.3 mmol/l (116 ± 5); p < 0.01]. After 2 years, participants receiving triple therapy had markedly lower postprandial plasma glucose concentration than participants receiving conventional therapy (Figure S3). The incremental area under the home-monitored blood glucose concentration curve was 1.7 ± 1.4 (31 ± 25) and 7.3 ± 3.6 (132 ± 65) mmol (mg)/dl/h in the triple and conventional therapy groups, respectively (p < 0.05).

Body Weight

Participants receiving triple therapy experienced a mean ± s.e.m. weight loss of 1.2 ± 1.1 kg at 6 months, which was maintained (1.2 ± 1.0 kg) at year 2. Participants receiving conventional therapy experienced weight gain which became evident at month 6 (+0.7 ± 0.6 kg) and increased progressively to 4.1 ± 0.9 kg after 2 years (p = 0.03). The difference in the change in body weight between the triple and conventional therapy groups at 2 years was 5.3 kg (p < 0.01).

Lipid Profile and Blood Pressure

Lipid profile at baseline was similar in both groups (Table 1). Participants in both treatment arms experienced a significant improvement in their lipid profiles. Neither therapy affected total cholesterol levels. The mean ± s.e.m. decrease in total cholesterol was 0.3 ± 0.3 (6.4 ± 5.0) and 0.6 ± 0.2 (11.3 ± 4.3) mmol/l (mg/dl) (p = non-significant) in participants receiving triple therapy and conventional therapy, respectively. Both therapies significantly lowered plasma triglyceride concentrations: by 1.8 ± 0.7 (32 ± 12) and 1.7 ± 0.6 (30 ± 11) mmol/l (mg/dl) in the triple and conventional therapy arms, respectively (both p < 0.01 vs. baseline). Triple therapy caused a significant increase in plasma HDL cholesterol [by 0.1 ± 0.1 mmol/l (2.1 ± 1 mg/dl); p < 0.05], while participants receiving conventional therapy experienced a 0.2 ± 0.1 mmol/l (3.6 ± 1.4 mg/dl) decrease (p < 0.001 vs. baseline and vs. triple therapy).

A small non-significant decrease in systolic blood pressure (−3.6 ± 3 mmHg, p = non-significant) was observed in participants receiving conventional therapy, while triple therapy caused a significant decrease in systolic blood pressure (−9.7 ± 4 mmHg, p < 0.05 vs. baseline and p = non-significant vs. conventional therapy).

Adverse Events

Two-thirds of participants receiving conventional therapy and one-half of participants receiving triple therapy experienced at least one adverse event (Table S2). The most common adverse event was hypoglycaemia, reported by 46 and 14% of participants receiving conventional and triple therapy, respectively. The overall frequency of hypoglycaemic events was greater in participants receiving conventional therapy (2.2 vs. 0.31 events/participant per year; p < 0.0001). All hypoglycaemic events were mild. Participants receiving triple therapy experienced more frequent gastrointestinal side effects and peripheral oedema. A total of 25% of participants in the triple therapy group experienced nausea secondary to exenatide, but it was mild and subsided after 2–3 months. The incidence of peripheral oedema was low at 1.3 vs. 5.3% in the conventional and triple therapy groups, respectively. Two deaths occurred in the conventional therapy group; both were unrelated to treatment (sleep apnoea; complication of surgical procedure for hernia). The number of participants who withdrew because of adverse events was small: 7 in the triple therapy and 3 in the conventional therapy group.

Discussion

The major finding of the present study was that starting drug-naïve subjects with recently diagnosed T2DM on a triple combination therapy of metformin, pioglitazone and exenatide, which have been shown to correct the pathophysiological defects (i.e. insulin resistance, β-cell dysfunction, hyperglucagonaemia) present in T2DM [13–15,21,22,28], reduces HbA1c levels and maintains them within the normal range for 2 years.

It should be noted that, in general, participants in both treatment arms experienced excellent glycaemic control. In participants receiving conventional therapy HbA1c decreased initially to 6.2% at 6 months, but subsequently increased to 6.5% at 2 years, despite continuous dose escalation of antidiabetic medications (sulfonylurea and insulin). This can be attributed to the rigorous uptitration of antidiabetic medications in participants in the conventional therapy arm. The magnitude of a progressive increase in HbA1c level in participants receiving conventional therapy is consistent with previous studies, which have reported 0.2–0.3% annual HbA1c increases in participants receiving metformin, sulfonylurea or insulin [3,10,11,18,29]. It remains to be seen whether the HbA1c will continue to rise above 6.5% despite rigorous dose escalation of sulfonylurea and insulin.

Conversely, participants receiving triple combination therapy were able to lower their HbA1c level to the normal range (<6.0%) and maintain levels in the normal range over a 2-year period. Longer follow-up is required to determine the duration of the benefits of triple therapy. It remains to be seen whether such a difference in HbA1c (6.5% in the conventional therapy vs. 5.9% in the triple therapy group) would be translated into greater prevention of diabetic microvascular complications. It should be noted that the progressive increase in HbA1c levels in patients in the UK Prospective Diabetes Study was paralleled by a progressive decline in β-cell function. It would therefore be of great interest to compare the impact of both therapies on β-cell function. Previous studies have consistently reported that both pioglitazone [13–15] and exenatide [21,22,28] improve β-cell function in T2DM, while pioglitazone is a potent insulin sensitizer [12]. Exenatide produced a significantly greater increase in β-cell function after 1 year compared with glargine insulin [28], and this beneficial effect persisted for 3 years [21]. Thiazolidinediones consistently improve β-cell function in T2DM and impaired glucose tolerance [13–17]. Not surprisingly, both GLP-1 analogues and thiazolidinediones have been shown in previous studies to produce a more durable HbA1c reduction compared with sulfonylureas and metformin [10,18,23,30], and patients who received pioglitazone in the PROactive study required less insulin than patients who received placebo [27]. In the present study, the mean HbA1c in participants receiving triple therapy at 2 years (5.95%) was similar to HbA1c at 6 months (6.0 ± 0.1%), while it increased by 0.3% (6.2% at 6 months to 6.5% at 2 years) in participants receiving conventional therapy.

More participants receiving triple than those receiving conventional therapy maintained the treatment goal (HbA1c < 6.5%). Failure to achieve the glycaemic goal in participants receiving triple therapy was evident at 6 months, while the majority (92%) of participants who achieved the treatment goal at 6 months maintained their HbA1c level at 2 years (Figure 3). This suggests that treatment failure in participants receiving triple therapy is primarily attributable to initial unresponsiveness to pioglitazone and exenatide; however, in participants who responded, these agents achieved durable (2-year) HbA1c reductions (Figure 3). Conversely, the proportion of participants receiving conventional therapy who failed to achieve the glycaemic treatment goal progressively increased with time, most likely because of progressive β-cell failure.

Despite greater decreases in fasting and postprandial plasma glucose and HbA1c levels in participants receiving triple versus those receiving conventional therapy, hypoglycaemia risk was ~7-fold greater in the latter; thus, initiation of combination therapy with metformin/pioglitazone/exenatide, not only produced greater, more durable HbA1c reductions, but is also safer with respect to hypoglycaemia compared with sulfonylureas and insulin. Notably, recent clinical trials have shown an association of hypoglycaemia with greater mortality risk [6], and the ADA and European Association for the Study of Diabetes [7] have recommended more conservative glycaemic targets in subjects at high risk of cardiovascular disease.

Both therapies significantly improved lipid profiles, but only the change in HDL cholesterol differed between therapies, increasing by 0.1 mmol/l (2.1 mg/dl) in participants receiving triple therapy, while it decreased in participants receiving conventional therapy [by 0.2 mmol/l (3 mg/dl)]. In addition to weight loss in participants receiving triple therapy, it is likely that pioglitazone exerted a direct effect to increase plasma HDL cholesterol levels. Previous studies have consistently shown that pioglitazone has a favourable action on HDL cholesterol [16]. Participants receiving triple therapy were also found to have a significant decrease in systolic blood pressure; however, the reduction in blood pressure did not significantly differ from the change in blood pressure in participants receiving conventional therapy.

Compared with the ~4-kg weight gain in participants receiving conventional therapy, participants receiving triple therapy experienced a 1.5–2-kg decrease in body weight, indicating that concomitant therapy with exenatide and/or metformin prevents the weight gain associated with pioglitazone. Weight gain in participants receiving conventional therapy became evident at 6 months and progressively increased with the escalation of sulfonylurea/insulin dose required to maintain HbA1c at <6.5%.

Both treatments were well tolerated and few participants (8.8% in the triple therapy and 3.2% in the conventional therapy group) withdrew because of adverse events. The rate of hypoglycaemia was relatively low (Table S2) compared with other studies that attempted to achieve similar glycaemic control (HbA1c < 6.5%) [31]. The low rate of peripheral oedema (Table S2) with triple therapy could be explained by the natriuretic effect of exenatide [32]. No cases of heart failure or fractures occurred in either group.

The present study has several limitations. First, this report is an interim analysis which was performed because the anticipated difference in HbA1c (0.5%) between the two treatment arms at 3 years was achieved at 2 years of follow-up (see sample size calculation in the Materials and Methods section). It remains to be seen whether this difference in HbA1c will be maintained at 3 years of follow-up or will continue to widen. Second, because the study was performed in a single centre, it included a relatively small number of participants, who were primarily of Mexican-American origin. A larger multi-ethnic study is warranted to examine the generalizability of this novel treatment approach in patients with newly diagnosed T2DM. Third, our results apply only to the specific regimen (metformin/pioglitazone/exenatide) used and not to other regimens. Fourth, there was a relatively high and similar dropout rate (25–33%) in each treatment arm. This dropout rate was similar, however to the ‘no-show’ rate (~30%) in the population with diabetes served at the Texas Diabetes Institute at which participants were recruited. Furthermore, the dropout rate was similar to or less than that observed in most published studies of similar duration with GLP-1 receptor agonists including exenatide [23,28], liraglutide [33,34] and Bydureon® [35], as well as in other widely quoted studies using other antidiabetic agents, for example, the ADOPT study with rosiglitazone [36] and the treat-to-target trial with insulin [34]. In these trials, the dropout rates (per 1-year follow-up were 29% [23], 34% [28], 52% [33], 35% [34], 26% [35], 42% [36] and 36% [37]). Furthermore, patient characteristics of those who dropped out were similar in both treatment arms and similar to those who continued in the study (Table S3). Fifth, the therapies used (exenatide and glargine) prohibited the study from being blinded. Sixth, because of the relatively small sample size and short duration, long-term outcome data about microvascular and macrovascular complications will not be available. Seventh, the HbA1c treatment goal of <6.5% was lower than the generally recommended ADA goal (<7.0%), although it is consistent with the HbA1c goal recommended by ADA in patients with new-onset diabetes without cardiovascular disease and that recommended by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. This required higher doses of insulin which may have contributed to the slightly higher rate of hypoglycaemia observed after initiation of insulin therapy; however, a slower titration rate would have led to a smaller HbA1c decrease and raised criticism that insulin dose escalation was not sufficiently aggressive to achieve the treatment goal. Furthermore, the major increase in hypoglycaemia incidence was observed with the initiation of glipizide therapy, before the start of glargine treatment. Importantly, despite significantly lower HbA1c (5.95%) at 2 years, the hypoglycaemic rate in the triple therapy group was very low. Treatment details at 6, 12 and 24 months are shown in Tables S4 and S5.

Because of the aforementioned limitations, the results of the present study should be viewed as a proof-of-concept for the exploration of the efficacy and tolerability of a novel therapeutic strategy, i.e. the initiation of combination therapy with metformin/pioglitazone/exenatide, compared with the currently recommended sequential add-on therapeutic strategy for the management of patients with newly diagnosed T2DM. We believe that the robust results observed in the present study will promote a larger multi-ethnic study with longer duration to validate the findings in the present study. Moreover, the results indicate that the cost-effectiveness evaluation of antidiabetic therapy should not be limited to the medication cost in relation to the short term reduction in HbA1c level, but should include other beneficial metabolic effects of each therapy that affect the risk of long-term diabetic complications; for example, the durability of reduction of HbA1c, risk of hypoglycaemia, weight loss and reduction of CVD risk factors. A larger multicentre study with longer duration and with clinical outcomes would allow such analysis.

In summary, the present results show that initiation of combination therapy with metformin/pioglitazone/exenatide at a mean of 5.1 months after clinical diagnosis of T2DM produces a greater HbA1c reduction with lower rate of hypoglycaemia compared with the currently recommended approach of sequential add-on therapy with conventional agents (sulfonylurea and insulin). Continued follow-up will be required to ascertain how long the beneficial effects of triple therapy are maintained.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Time-related change in glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) in participants (as-treated population) receiving conventional therapy and triple combination therapy during the 24-month follow-up period. *p < 0.01.

Figure S2. Decrease in glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) in participants who were lost to follow-up before 6 months (not included in the analysis; open circles) (A) and participants who were included in the analysis (closed circles)(B).

Figure S3. Seven-point home blood glucose measurements in subjects receiving triple therapy and conventional therapy. FPG, fasting plasma glucose; 2h-AB, 2 h after breakfast; BL, before lunch; 2h-AL, 2 h after lunch; BS, before supper; 2h-AS, 2 h after supper; BT, bedtime.

Table S1. Baseline characteristics of participants who dropped out before month 6 plus those who dropped out between months 6 and 24 versus those who were included in the analysis in the conventional and triple therapy groups.

Table S2. Adverse events reported by subjects in the conventional and triple therapy groups during the 24-month follow-up period.

Table S3. Reasons for dropout among participants who completed the 6-month follow-up visit.

Table S4. Percentage of participants taking antidiabetic agents at months 6, 12 and 24.

Table S5. Medication dose at months 6, 12 and 24.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by grants to R. A. D. from the ADA, Amylin Pharmaceuticals, BristolMyers Squibb, Astra Zeneca and Eli Lilly. Takeda Pharmaceutical provided pioglitazone for the study and the glucose meters and strips for daily glucose monitoring. The study protocol was drafted by R. A. D. and M. A. G. and the data analysis, conclusions and manuscript drafting were carried out by R. A. D. with no influence from the funding sources, who remained blinded to the results. C. P., C. T., J. A. and E. C. contributed to the data generation. All authors contributed to the discussion of the results. The South Texas Veterans Health Care Administration supports 5/8ths of R. A. D.’s salary.

The study protocol was drafted by R. A. D. and M. A. G. and the data analysis, conclusions and manuscript drafting were carried out by R. A. D., with no influence from the funding sources, who remained blinded to the results. C. P., C. T., J. A. and E. C. contributed to the data generation.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

M. A. A., C. P., C. T., D. M., J. A. and E. C. have nothing to disclose. R. A. D. has served on the Speakers Bureau for Bristol Myers Squibb/Astra Zeneca and Novo Nordisk, has received grants from Bristol Myers Squibb, Takeda Pharmaceuticals U.S.A. Inc, Amylin, VeroScience and Xeris, and served on the Advisory Boards for Bristol Myers Squibb/Astra Zeneca, Takeda, Novo-Nordisk, Janssen and Lexicon.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

References

- 1.DeFronzo RA. Banting Lecture. From the triumvirate to the ominous octet: a new paradigm for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes. 2009;58:773–795. doi: 10.2337/db09-9028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:977–986. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199309303291401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Intensive blood-glucose control with sulphonylureas or insulin compared with conventional treatment and risk of complications in patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 33) Lancet. 1998;352:837–853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nakagami T, Kawahara R, Hori S, Omori Y. Glycemic control and prevention of retinopathy in Japanese NIDDM patients. A 10-year follow-up study. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:621–622. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.4.621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klein R, Klein BE, Moss SE. Relation of glycemic control to diabetic microvascular complications in diabetes mellitus. Ann Intern Med. 1996;124:90–96. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-124-1_part_2-199601011-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seaquist ER, Anderson J, Childs B, et al. Hypoglycemia and diabetes: a report of a workgroup of the American Diabetes Association and the Endocrine Society. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:1384–1395. doi: 10.2337/dc12-2480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes: a patient-centered approach: position statement of the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) Diabetes Care. 2012;35:1364–1379. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DeFronzo RA, Goodman AM, The Multicenter Metformin Study Group Efficacy of metformin in patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:541–549. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199508313330902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rossetti L, DeFronzo RA, Gherzi R, et al. Effect of metformin treatment on insulin action in diabetic rats: in vivo and in vitro correlations. Metabolism. 1990;39:425–435. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(90)90259-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kahn SE, Haffner SM, Heise AM, et al. Glycemic durability of rosiglitazone, metformin, or glyburide monotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2427–2443. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) 13: Relative efficacy of randomly allocated diet, sulphonylurea, insulin, or metformin in patients with newly diagnosed non-insulin dependent diabetes followed for three years. BMJ. 1995;310:83–88. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bays H, Mandarino L, DeFronzo RA. Role of the adipocyte, free fatty acids, and ectopic fat in pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes mellitus: peroxisomal proliferator-activated receptor agonists provide a rational therapeutic approach. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:463–478. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-030723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rasouli N, Kern PA, Reece EA, Elbein SC. Effects of pioglitazone and metformin on beta-cellfunction in nondiabetic subjects at high risk for type 2 diabetes. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;292:E359–365. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00221.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xiang AH, Peters RK, Kjos SL, et al. Effect of pioglitazone on pancreatic beta-cellfunction and diabetes risk in Hispanic women with prior gestational diabetes. Diabetes. 2006;55:517–522. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.55.02.06.db05-1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jin J, Yu Y, Yu H, Wang C, Zhang X. Effects of pioglitazone on beta-cellfunction in metabolic syndrome patients with impaired glucose tolerance. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2006;74:233–241. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2006.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.DeFronzo RA, Tripathy D, Schwenke DC, et al. Pioglitazone for diabetes prevention in impaired glucose tolerance. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1104–1115. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1010949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gastaldelli A, Ferrannini E, Miyazaki Y, Matsuda M, Mari A, DeFronzo RA. Thiazolidinediones improve beta-cell function in type 2 diabetic patients. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;292:E871–883. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00551.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mazzone T, Meyer PM, Feinstein SB, et al. Effect of pioglitazone compared with glimepiride on carotid intima-media thickness in type 2 diabetes: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2006;296:2572–2581. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.21.joc60158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hanefeld M, Pfutzner A, Forst T, Lubben G. Glycemic control and treatment failure with pioglitazone versus glibenclamide in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a 42-month, open-label, observational, primary care study. Cur Med Res Opin. 2006;22:1211–1215. doi: 10.1185/030079906X112598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Drucker DJ. The biology of incretin hormones. Cell Metab. 2006;3:153–165. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bunck MC, Cornér A, Eliasson B, et al. Effects of exenatide on measures of β-cell function after 3 years in metformin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:2041–2047. doi: 10.2337/dc11-0291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chang AM, Jakobsen G, Sturis J, et al. The GLP-1 derivative NN2211 restores beta-cell sensitivity to glucose in type 2 diabetic patients after a single dose. Diabetes. 2003;52:1786–1791. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.52.7.1786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gallwitz B, Guzman J, Dotta F, et al. Exenatide twice daily versus glimepiride for prevention of glycaemic deterioration in patients with type 2 diabetes with metformin failure (EUREXA): an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;379:2270–2278. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60479-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abdul-Ghani M, Jenkinson C, Richardson D, Tripathy D, DeFronzo RA. Insulin secretion and insulin action in subjects with impaired fasting glucose and impaired glucose tolerance: results from the Veterans Administration Genetic Epidemiology Study (VAGES) Diabetes. 2006;55:1430–1435. doi: 10.2337/db05-1200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gerstein HC, Miller ME, Byington RP, ACCORD Study Group et al. Effects of intensive glucose lowering in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2545–2559. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patel A, MacMahon S, Chalmers J, ADVANCE Collaborative Group et al. Intensive blood glucose control and vascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2560–2572. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0802987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dormandy JA, Charbonnel B, Eckland DJ, et al. Secondary prevention of macrovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes in the PROactive Study (PROspectivepioglitAzone Clinical Trial in macroVascular Events): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;366:1279–1289. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67528-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bunck MC, Diamant M, Cornér A, et al. One-year treatment with exenatide improves beta-cell function, compared with insulin glargine, in metformin-treated type 2 diabetic patients: a randomized, controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:762–768. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brown JB, Conner C, Nichols GA. Secondary failure of metformin monotherapy in clinical practice. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:501–506. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nissen SE, Nicholls SJ, Wolski K, et al. Comparison of pioglitazone vs glimepiride on progression of coronary atherosclerosis in patients with type 2 diabetes: the PERISCOPE randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299:1561–1573. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.13.1561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lingvay I, Legendre JL, Kaloyanova PF, Zhang S, Adams-Huet B, Raskin P. Insulin-based versus triple oral therapy for newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes: which is better? Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1789–1795. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gutzwiller JP, Tschopp S, Bock A, et al. Glucagon-like peptide 1 induces natriuresis in healthy subjects and in insulin-resistant obese men. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:3055–3061. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nauck M, Frid A, Hermansen K, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety comparison of liraglutide, glimepiride and placebo, all in combination with metformin in type 2 diabetes: 2-year results from the LEAD-2 study. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2013;15:209–212. doi: 10.1111/dom.12012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pratley RE, Nauck MA, Bailey T, et al. Efficacy and safety of switching from the DPP-4 inhibitor sitagliptin to the human GLP-1 analog liraglutide after 52 weeks in metformin-treated patients with type 2 diabetes: a randomized, open-label trial. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:1986–1993. doi: 10.2337/dc11-2113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Diamant M, Van Gaal L, Stranks S, et al. Safety and efficacy of once-weekly exenatide compared with insulin glargine titrated to target in patients with type 2 diabetes over 84 weeks. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:683–689. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kahn SE, Haffner SM, Heise MA, et al. Glycemic durability of rosiglitazone, metformin, or glyburide monotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2427–2443. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rodbard HW, Cariou B, Zinman B, et al. Comparison of insulin degludec with insulin glargine in insulin-naïve participants with Type 2 diabetes: a 2-year randomized, treat-to-target trial. Diabet Med. 2013;30:1298–1304. doi: 10.1111/dme.12303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Time-related change in glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) in participants (as-treated population) receiving conventional therapy and triple combination therapy during the 24-month follow-up period. *p < 0.01.

Figure S2. Decrease in glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) in participants who were lost to follow-up before 6 months (not included in the analysis; open circles) (A) and participants who were included in the analysis (closed circles)(B).

Figure S3. Seven-point home blood glucose measurements in subjects receiving triple therapy and conventional therapy. FPG, fasting plasma glucose; 2h-AB, 2 h after breakfast; BL, before lunch; 2h-AL, 2 h after lunch; BS, before supper; 2h-AS, 2 h after supper; BT, bedtime.

Table S1. Baseline characteristics of participants who dropped out before month 6 plus those who dropped out between months 6 and 24 versus those who were included in the analysis in the conventional and triple therapy groups.

Table S2. Adverse events reported by subjects in the conventional and triple therapy groups during the 24-month follow-up period.

Table S3. Reasons for dropout among participants who completed the 6-month follow-up visit.

Table S4. Percentage of participants taking antidiabetic agents at months 6, 12 and 24.

Table S5. Medication dose at months 6, 12 and 24.