Abstract

Retroelements, the prevalent class of plant transposons, have major impacts on host genome integrity and evolution. They produce multiple proteins from highly compact genomes and, similar to viruses, must have evolved original strategies to optimize gene expression, although this aspect has been seldom investigated thus far. Here, we have established a high-resolution transcriptome/translatome map for the near-entirety of Arabidopsis thaliana transposons, using two distinct DNA methylation mutants in which transposon expression is broadly de-repressed. The value of this map to study potentially intact and transcriptionally active transposons in A. thaliana is illustrated by our comprehensive analysis of the cotranscriptional and translational features of Ty1/Copia elements, a family of young and active retroelements in plant genomes, and how such features impact their biology. Genome-wide transcript profiling revealed a unique and widely conserved alternative splicing event coupled to premature termination that allows for the synthesis of a short subgenomic RNA solely dedicated to production of the GAG structural protein and that preferentially associates with polysomes for efficient translation. Mutations engineered in a transgenic version of the Arabidopsis EVD Ty1/Copia element further show how alternative splicing is crucial for the appropriate coordination of full-length and subgenomic RNA transcription. We propose that this hitherto undescribed genome expression strategy, conserved among plant Ty1/Copia elements, enables an excess of structural versus catalytic components, mandatory for mobilization.

Transposable elements (TEs) are genomic parasites with highly diverse life styles and proliferation strategies, both of which are strongly dependent upon their host organisms. DNA transposons, which self-propagate via transposition of their genomic sequence during host DNA replication, are abundant in invertebrate genomes; retrotransposons, in contrast, proliferate via an RNA intermediate and are highly represented in both mammalian and plant genomes (Huang et al. 2012). Long terminal repeat (LTR) retrotransposons are the main contributors to the invasion of most plant genomes. They include the young Ty1/Copia family that comprises the few active elements in the autogamous model plant species Arabidopsis thaliana (Tsukahara et al. 2009; Gilly et al. 2014; Quadrana et al. 2016). In contrast, Ty3/Gypsy elements, the other main class of LTR retrotransposons, are considerably older and more degenerated and, hence, have lost autonomy in the A. thaliana genome (Peterson-Burch et al. 2004).

In plants, the transcriptional activity of TEs is suppressed by DNA methylation, which is sustained by METHYLTRANSFERASE 1 (MET1) in the symmetric CG sequence context (Saze et al. 2003). At CHG sequences (H: any nucleotide but G), maintenance is facilitated by a positive feedback-loop involving the DNA methyltransferase CHROMOMETHYLASE 3 (CMT3) and histone 3 lysine 9 (H3K9) methyltransferase KRYPTONITE (KYP) (Jackson et al. 2002). Asymmetric CHH methylation is dynamically maintained by RNA-directed DNA methylation (RdDM), largely relying on 24-nt small interfering RNA (siRNA) species produced by the Dicer-like-3 (DCL3) RNase III enzyme (Mette et al. 2000; Xie et al. 2004). The nucleosome remodeler DECREASED DNA METHYLATION 1 (DDM1) facilitates DNA methylation in all sequence contexts by enabling access of condensed heterochromatin to DNA methyltransferases (Zemach et al. 2013).

The A. thaliana Ty1/Copia element Évadé (EVD) is among the few autonomous retroelements that is reactivated and can mobilize upon release of epigenetic silencing in met1 or ddm1 mutant backgrounds (Mirouze et al. 2009; Tsukahara et al. 2009). Its mode of genome invasion was recently reconstructed using a met1 epigenetic recombinant inbred line (epiRIL), unravelling separate phases of reactivation, expansion, and, finally, epigenetic resilencing (Marí-Ordóñez et al. 2013). While the plant responses to EVD were well described in this study, little insight was gained as to which transcriptional and/or translational features enabled EVD to adapt to, or evade, these responses. Successful transposition of LTR retrotransposons relies on host-dependent transcription of their genomic sequence, which encodes for the structural GAG and the catalytic polyprotein (POL) composed of an aspartic protease, an integrase, and a reverse transcriptase (RT). Upon encapsidation of the genomic RNA and the POL components by the GAG nucleocapsid, reverse transcription and integration of the newly synthesized cDNA into the host genome ensue (Schulman 2013). All these events must be tightly coordinated and balanced for retrotransposition. Of paramount importance in this regard, and similar to retroviruses, is the mandatory molar excess of the structural GAG protein over the catalytic POL components (Lawler et al. 2001; Shehu-Xhilaga et al. 2001), which is achieved via diverse translational strategies. Ty1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and HIV-1 in human use translational frameshifting owing to GAG and catalytic POL components being encoded in two distinct open reading frames (ORFs). GAG, encoded in the first frame, is optimally translated while ribosomal slipping allows for scarcer POL translation (Clare et al. 1988; Jacks et al. 1988). Alternatively, the genomes of the Candida albicans Ty1/Copia element, Tca2, and of Moloney murine leukaemia retrovirus (MLV) encode for a stop codon between GAG and POL (Yoshinaka et al. 1985; Matthews et al. 1997), and POL suboptimal translation is achieved by suppression of the stop codon via a pseudoknot RNA structure (Wills et al. 1991). However, many other retroelements, those of plants in particular, are encoded in a single, long ORF not enabling translational recoding (Gao et al. 2003). The single-ORF element Ty5 in Saccharomyces uses post-translational degradation of POL to achieve the necessary high GAG/POL ratio (Irwin and Voytas 2001), but other strategies exist that rely on transcriptional adaptations. Most notably, the copia element in Drosophila melanogaster generates a specific RNA, coding only for GAG, following splicing of an intron covering the entire POL region (Yoshioka et al. 1990). Similarly, the BARE1 Ty1/Copia element in barley features a short intron just downstream from the GAG domain. Splicing generates a frameshift that subsequently introduces a stop codon predicted to favor GAG translation and simultaneously abrogate the POL coding potential (Chang et al. 2013), although this prediction awaits experimental validation. Thus, various genome expression strategies have been described for individual retroelements and retroviruses of diverse organisms. Nonetheless, comprehensive parallel studies of the genome organization and RNA expression strategies of TEs found in whole-host genomes are rare (Faulkner et al. 2009; Sienski et al. 2012; Blevins et al. 2014) since they usually require the reactivation of TE expression in TE-permissive genetic backgrounds, as well as unbiased genome-wide transcriptome analysis and annotation.

Here, we have used the ddm1 and met1 mutants to reactivate expression of a large set of TEs in A. thaliana and establish a high-quality TE transcriptome and translatome map of the five host chromosomes. Exploiting this resource allowed us to uncover a specific genome expression strategy shared by the Ty1/Copia class of elements, which we studied in detail by focusing on epigenetically reactivated elements, as well as transgenically expressed EVD.

Results

Epigenetically reactivated EVD undergoes alternative splicing

To investigate how the molar excess of GAG-to-POL (Fig. 1A) is achieved by TEs in A. thaliana, we first focused on EVD expression in the met1 and ddm1 backgrounds, where it is transcriptionally reactivated among many other TEs. To find which transcripts are spawned from EVD, we extracted RNA from inflorescences to conduct RT-PCR using primers flanking the EVD protease domain. We identified two alternative RNA isoforms, revealing a splicing event (Fig. 1B). Sequencing showed that splicing of the intron removes the entire protease (PR) sequence and introduces a frame-shift in the coding sequence to generate a new stop codon for GAG, shortly after the splice junction (Fig. 1C,D). Similar to the conjecture made for the barley BARE1 element, this process potentially allows for the production of a subgenomic mRNA solely dedicated to GAG production from EVD. Since such a strategy appears to be shared among two TEs from different species, we asked how it applies to the various Ty1/Copia elements of A. thaliana in general, leading us to develop the large-scale approach detailed in the next section.

Figure 1.

A scheme for Ty1/Copia protein production and alternative splicing of the EVD RNA. (A) Scheme of the generic Ty1/Copia elements’ genome and a putative alternative splicing strategy to modulate protein abundances from the condensed genome, as required for successful TE life cycle. (B) Alternative isoforms of EVD detected by RT-PCR using primers flanking the protease domain. ACTIN 2 (ACT2) PCR uses primers flanking an intron to amplify a longer PCR product corresponding to the genomic DNA (gDNA) and a shorter cDNA form. It serves as a loading control and validates the absence of genomic DNA contamination. (C) Schematic representation of the region surrounding the EVD intron. Arrows indicate the flanking primers used in B. (D) Genomic (gDNA) and spliced sequences of the region flanking the EVD intron in met1 and ddm1 backgrounds. (LTR) long terminal repeat; (PR) protease; (IN) integrase; (RT-RNase) reverse-transcriptase-RNase; (VLP) viral-like particle; (SD) splice donor; (SA) splice acceptor.

A comprehensive high-resolution map of TE transcription in DNA methylation–deficient A. thaliana

A genome-wide map of the TE transcriptome was generated using high-coverage, paired-end, and stranded total RNA-sequencing of A. thaliana inflorescences in a wild-type (WT; Col-0) background or the TE de-repressed backgrounds ddm1 and met1. As expected, the TE contribution to the transcriptome of WT plants was low, with 0.4% of mapped read pairs, but, remarkably, it was up to 5%–7% in the mutant backgrounds (Supplemental Fig. S1A). To validate the suitability of these data for global TE transcript investigation, we analyzed all reactivated TEs with respect to their superfamily, chromosomal location, and length profile. We found that all TE families, including DNA transposons and retroelements, are up-regulated in both mutant backgrounds (Supplemental Fig. S1B; Supplemental Table S1). Most reactivated TEs are in pericentromeric regions, known to display the highest TE density (Cokus et al. 2008). Overall, TE reactivation is stronger in ddm1, accounting for 24% of uniquely de-repressed elements compared with 3% in met1. Thus, 73% of de-repressed TEs are transcriptionally reactivated in both backgrounds (Supplemental Fig. S1C). Remarkably and in agreement with previous genome-wide methylation studies (Zemach et al. 2013), these TEs are generally long elements (Supplemental Fig. S1D), even though only few full-length elements are found in the genome (Vitte and Bennetzen 2006). The same was observed in a focused analysis of Ty1/Copia elements: Despite the prevalence of short and degenerated fragments, a strong transcriptional reactivation of long, potentially full-length elements was observed (Supplemental Fig. S1E). We also found that expression of de-repressed TEs is independent of transcription from neighboring protein-coding genes and that, accordingly, de-repressed TEs are rarely located within or in close proximity to genes or introns (Supplemental Fig. S1F–H). The repetitive nature of TEs causes a potential caveat in the precise mapping of sequencing reads to single elements. Nonetheless, we found that Ty1/Copia elements show enough sequence variation to enable their individual identification given sufficient sequencing read length and coverage (Supplemental Fig. S1I), and we could ascertain that most reactivated Ty1/Copia elements analyzed in this study are flanked by their cognate LTRs (Supplemental Fig. S1J), known to harbor promoter and terminator sequences (Voytas and Boeke 2002). Thus, the ddm1 and met1 data sets constitute valuable resources to study potentially intact and transcriptionally active transposons in A. thaliana, as exemplified here with Ty1/Copia elements, the main focus of our analysis.

Alternative splicing uniquely centered around the protease domain is a highly conserved feature of Ty1/Copia elements

To investigate alternative RNA isoforms of A. thaliana Ty1/Copia elements, we developed an algorithm to confidently identify introns in potentially functional, full-length TEs by excluding sequences <3.5 kb or >6 kb. We identified more than 200 full-length copies of Ty1/Copia elements, more than half of which are transcriptionally active in at least one of the two mutants (ddm1, met1). By use of the STAR RNA-seq mapper (Dobin et al. 2012), splice junctions were investigated in the background where each element is the most expressed. The minimal junction overhang was reduced to 3 nucleotides (nt) to enhance the prospect of novel junction identification, and only elements with at least five reads covering the intron junctions were selected. This approach revealed that more than half of expressed Ty1/Copia elements are spliced in A. thaliana (Fig. 2A), a conservative estimate given that some elements classified as “nonsplicers” likely contain an intron but simply did not pass our stringency requirements. Respectively, 70% and 20% of spliced Ty1/Copia elements were identified in the ddm1 and met1 background, consistent with the former displaying the highest reactivated TE expression levels. Surprisingly, ∼10% of spliced TEs have higher expression in WT plants, and splice junctions were thus also annotated in this background (Supplemental Fig. S2A; Supplemental Table S2).

Figure 2.

Genome-wide analysis of splicing of Ty1/Copia elements in A. thaliana. (A) Selection of spliced Ty1/Copia elements from RNA-seq data of globally reactivated transposons. (B) Density profile of splice donor and splice acceptor sites on a multiple sequence alignment of spliced Ty1/Copia elements selected in A. (C,D) Intron length (C) and (D) nucleotide sequence composition (D) of detected Ty1/Copia introns and A. thaliana gene introns. (E) RNA-seq profiles of spliced Ty1/Copia elements in wild-type (Col-0), met1, and ddm1 backgrounds. A continuum of splicing intensities is depicted with specific examples, displayed by arcs and numbers below the sequence coverage indicating splice-junction reads. Green annotation bars represent the entire TE annotation, including LTRs, whereas yellow annotation bars indicate the TE gene annotation covering only the protein coding sequence. In all panels, (***) P < 0.001 (Wilcoxon rank-sum test); (n) number of individual elements or introns analyzed.

To explore if the predicted splicing events shared a common pattern, we generated a multiple alignment of all spliced Ty1/Copia sequences and mapped the positions of the most prominent splice donor and acceptor sites. These were remarkably conserved and, as in EVD, prevalently centered around the protease domain, suggesting strong positive selection (Fig. 2B). In contrast, an analysis of the older and thus more degenerated Ty3/Gypsy superfamily (Peterson-Burch et al. 2004) did not reveal such conserved splicing features (Supplemental Fig. S2B). Ty1/Copia introns are on average approximately three times longer than regular A. thaliana introns (Fig. 2C), reminiscent of the Drosophila copia element whose ∼3-kb-long intron is significantly longer than the median 103-nt of annotated Drosophila introns (Yoshioka et al. 1990). However, both remain within the upper limit of intron lengths in their respective hosts, in which >10% of annotated introns are longer still, suggesting an adaptation of both elements to their cognate host splicing machineries (Supplemental Fig. S2C). Accordingly, the base composition of Ty1/Copia introns resemble that of Arabidopsis gene introns, with an overrepresentation of A and U nucleotides, a well-conserved intronic feature (Fig. 2D; Goodall and Filipowicz 1989). Ty1/Copia introns also display highly conserved GU and AG dinucleotides found, respectively, in splice donor and acceptor sites of eukaryotic gene introns, as well as the canonical U1 binding site, suggesting that their splicing operates through the major spliceosome pathway (Fig. 2D; Turunen et al. 2012). We ranked the sequence composition of the 5′ and 3′ splice sites using a position-specific scoring matrix generated from the subset of annotated Arabidopsis introns, as previously described (Tian et al. 2007). This further confirmed that Ty1/Copia introns are at least as well defined as their host gene counterparts (Supplemental Fig. S2D).

Having established a well-defined set of Ty1/Copia introns, we decided to further elucidate the transcriptional behavior of single elements, starting with EVD. Confirming the RT-PCR/sequencing results (Fig. 1B–D), the EVD RNA-seq profile displays splice junction reads but also retains coverage inside the intron. This indicates the coexistence of spliced and unspliced RNA, a feature necessary to produce the transcript potentially enabling excess GAG production, on the one hand, but also the full-length mRNA required for translation of the POL components, on the other. Some elements, including COPIA38B, also display the two RNA isoforms, while others define an unexpectedly large spectrum of splicing potency, with the fully spliced COPIA89 and COPIA8A being at the lower end of this spectrum (Fig. 2E). The paucity or complete absence of reads downstream from the intron of highly spliced TEs suggested a positive correlation between the degree of splicing and the apparent premature termination of the GAG RNA. This observation prompted us to investigate if this potential link between splicing and premature termination also existed in elements that, like EVD, produce both spliced and unspliced RNAs.

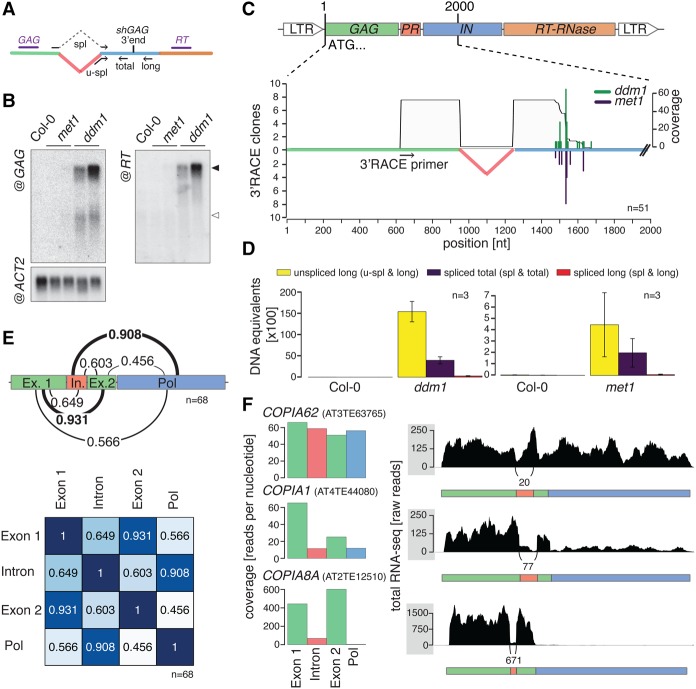

The splicing potency of Ty1/Copia elements correlates with premature termination of the GAG mRNA

Northern analysis of EVD-derived RNA species revealed a short, presumably spliced transcript, detected with the GAG but not the downstream RT probe (Fig. 3A,B). 3′ RACE (rapid amplification of cDNA ends) was then conducted via reverse transcription of poly(A)-RNA and forward priming within the GAG region, followed by PCR and sequencing. A uniform 3′ end pattern mapping to the beginning of the integrase domain was uncovered in both the ddm1 and met1 backgrounds. This strongly suggests that the spliced GAG short RNA is an mRNA (Fig. 3C), as already suggested by our primary observation that splicing-induced stop codon formation creates a GAG ORF (Fig. 1D). Strikingly, only one out of 51 sequenced clones encompassed the intronic region, further supporting our previously made observation that splicing seems to be linked to premature termination. We thus predicted that, conversely, transcription beyond the identified termination site would correlate with intron retention. By use of primers matching the spliced or unspliced mRNA in combination with primers located downstream from or upstream of the short mRNA termination site (Fig. 3A), a qPCR assay was developed to differentiate, by absolute quantification, spliced and unspliced transcripts, as well as full-length and total RNA (including both isoforms). The results identified the long EVD RNA as the prevalently accumulating form and showed that the bulk of this molecule retains the intron. They also confirmed that splicing of EVD is indeed tightly linked to premature termination closely downstream from the splice junction (Fig. 3D). We conclude that EVD generates two distinct mRNA isoforms. The first species, coined “shGAG RNA” is short and spliced and encodes solely for GAG, whereas the second species, coined “GAG-POL RNA,” is long and unspliced and encodes the entire GAG-POL polyprotein.

Figure 3.

The shGAG subgenomic mRNA of EVD is prematurely terminated. (A) Scheme representing RNA blot probes (purple) and spliced (spl) and unspliced (u-spl) specific primers (black arrows) used for qPCR analysis of transcripts from epigenetically reactivated EVD. (B) Northern blot analysis of EVD-derived transcripts in wild-type (Col-0), met1, and ddm1 plants. The full-length GAG-POL mRNA is indicated with a filled arrow; shGAG mRNA, with an empty arrow. (C) 3′ RACE analysis of the EVD shGAG mRNA. Green and blue bars represent 3′ ends cloned in ddm1 and met1 backgrounds, respectively. The gray area shows cumulative sequence coverage in both backgrounds. Positions are indicated in nucleotides (nt) from the EVD start codon. (n) number individual 3′ RACE clones sequenced. (D) Absolute qPCR quantification of spliced (spl) versus unspliced (u-spl) EVD transcripts from ddm1 and met1 plants versus Col-0. Error bars, SE of three biological replicates. (E) Pearson correlations of per-nucleotide coverage from total RNA-seq of the four bins (Exon 1, Intron, Exon 2, and POL) generated from novel intron annotations and extrapolation of the novel EVD termination site, as determined in C. (F) Examples of Ty1/Copia elements illustrating increasing splicing efficacies and corresponding intron versus POL expression ratios.

Does the link between splicing and termination also apply to other spliced Ty1/Copia elements? To address this question, we predicted termination sites for all spliced Ty1/Copia elements based on multiple sequence alignment and the EVD termination site identified by 3′ RACE. By using those predictions together with the newly annotated introns, Ty1/Copia sequences where divided into four bins: (1) Exon 1 encompassing sequences from GAG up to the annotated splice donor site, (2) Intron, (3) Exon 2 encompassing sequences from the splice acceptor site to the predicted termination site, and (4) POL defined by the remaining downstream sequences (Fig. 3E). By use of whole-transcriptome data, a comparison of RNA-seq coverage found in each bin showed a strong correlation of RNA expression levels between Exon 1 and Exon 2 (R2= 0.931), on one hand, and Intron and POL (R2= 0.908), on the other (Fig. 3E). These high correlations were not due to biases caused by individual TE expression levels, since they were not observed with other combinations (Fig. 3E). The results therefore establish a general link between splicing and premature termination of Ty1/Copia elements. They also strongly suggest that full-length transcription requires intron retention. The COPIA62, COPIA1, and COPIA8A elements illustrate well this phenomenon by showing how a progressive increase in splicing potency is inversely paralleled by a progressive loss of intron and POL read coverage (Fig. 3F).

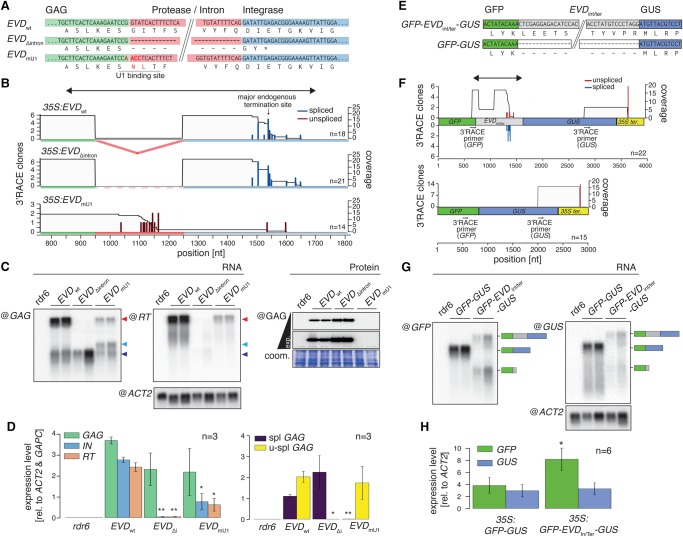

The U1 snRNP enables shGAG RNA production and concomitantly inhibits premature termination of the unspliced full-length EVD RNA

We explored which features modulate the splicing efficiency of Ty1/Copia elements, focusing first on the 5′ and 3′ splice sites known as key determinants in this process (Wu et al. 1999; Freund 2005). A significantly stronger and positive correlation was found between the splicing efficiency and the quality of the 5′ splice donor site as opposed to the 3′ splice acceptor site of the Ty1/Copia elements analyzed (Supplemental Fig. S2E). This agrees with our observation that the 5′ splice donor site, which resembles the canonical U1 binding site of Arabidopsis introns, is conserved among Ty1/Copia introns (Fig. 2D). While U1 snRNP base-pairing with the splice donor site is crucial for spliceosome assembly (Brown 1996), the U1 snRNP also has distinct splicing-independent functions, most notably to repress transcriptional termination and 3′ end formation at nearby cryptic polyadenylation signals, generally located within introns (Gunderson et al. 1998). In human cells, for instance, artificially depleting U1 snRNPs causes premature termination inside introns, a phenomenon observed prior to splicing defects (Berg et al. 2012). Assuming that, likewise, the 5′ splice site of Ty1/Copia elements defines splicing and that U1 snRNP binding concomitantly promotes inhibition of premature termination, we predicted that genetic modifications to the 5′ splice site would possibly alter the balance of Ty1/Copia mRNA isoforms.

We used a previously described transgenic construct in which the WT EVD coding sequence is under the control of the Cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter (35S:EVDwt) (Marí-Ordóñez et al. 2013) and generated two mutant versions thereof. In the first mutant, coined 35S:EVDΔintron, the entire EVD intron is deleted at the DNA level. In the second, coined 35S:EVDmU1, point-mutations engineered in the 5′ splice donor site are predicted to abolish U1 binding (Fig. 4A). To better study the impact of splicing on RNA isoform levels and protein production from EVD, we raised antibodies against EVD GAG and reverse transcriptase (RT) proteins. While we successfully detected GAG protein in inflorescences of EVD-expressing plants, we failed to detect a specific signal using RT antibodies (Supplemental Fig. S3). In order to study EVD transcription, transgenic lines expressing 35S:EVDwt, 35S:EVDΔintron, or 35S:EVDmU1 were generated in the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase 6 (rdr6) mutant background used to minimize the occurrence of spontaneous post-transcriptional gene silencing (PTGS) (Mourrain et al. 2000). RNA blot analysis conducted in inflorescences of independent lines established for each construct showed that, like endogenous EVD (Fig. 3B), 35S:EVDwt accumulates a short and a long RNA, the latter being more abundant (Fig. 4B–D). Moreover, termination of the shGAG RNA is well defined at the previously identified endogenous termination site and is also tightly linked to splicing, as determined by 3′ RACE (Fig. 4B). The transcriptional features of 35S:EVDwt therefore closely resemble those of endogenous EVD. In contrast, 35S:EVDΔintron only accumulates the spliced shGAG RNA (Fig. 4B–D) whose 3′ end coincides with the endogenous shGAG RNA termination site (Fig. 4B). This result therefore confirms that intron retention, or sequences located within the intron, is required to prevent 3′ end formation at the shGAG poly(A) and to thereby enable EVD full-length mRNA transcription/translation. In addition, increased shGAG mRNA levels in 35S:EVDΔintron (Fig. 4D) correlate with increased GAG protein levels (Fig. 4C), confirming the shGAG RNA as the major template for GAG translation. 35S:EVDmU1 also generates short and long RNAs (Fig. 4B–D); however, both species are fully unspliced in this case (Fig. 4D). In addition to terminating at the cognate shGAG poly(A) site, a significant fraction of short RNAs from 35S:EVDmU1 undergo termination at a cryptic poly(A) site located within the intron (Fig. 4B). These results support a role for U1 snRNPs in inhibiting premature termination in plants, as described in mammals (Wypijewski et al. 2009). Short unspliced RNAs do not bear any coding potential for GAG, since lack of splicing impedes formation of the mandatory stop codon (Fig. 1D). Nonetheless, substantial levels of GAG-POL full-length RNA with GAG coding potential remain produced from 35S:EVDmU1, yet GAG protein levels are below detection limit (Fig. 4C). Therefore, translation of the full-length EVD transcript accounts for minimal GAG protein production, if at all. Besides, the GAG-POL polyprotein expected to be produced from endogenous EVD is below the detection limit with the GAG antibody even in the overexpressing 35S:EVDwt lines (Supplemental Fig. S3), further supporting that the GAG-POL mRNA is generally poorly translated. Therefore, the shGAG RNA is not only sufficient but also necessary for effective GAG protein production. Together with the fact that 35S:EVDΔintron, in which essential parts of the U1 binding site are removed, mostly terminates at the cognate shGAG terminator, these results suggest an elegant system of cotranscriptional regulation of EVD, in which splicing and termination are tightly interconnected events. In this model, besides its primary function in spliceosome assembly required for shGAG RNA production and optimal GAG translation, the U1 snRNP would concurrently inhibit premature termination at the intronic cryptic poly(A) signal but also, and more importantly, at the cognate, downstream endogenous shGAG poly(A) site, thereby enabling full-length EVD transcription. The proposed repression of premature termination by the U1 snRNP must be efficient because, as shown with endogenous EVD (Fig. 3B), accumulation of the full-length, intron-containing EVD GAG-POL RNA largely dominates that of the shGAG RNA in 35S:EVDwt-expressing lines (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4.

Mutational analyses of ectopically expressed EVD and full reconstruction of its splicing behavior in a reporter system. (A) Nucleotide and corresponding amino acid sequence of 35S:EVDwt, 35S:EVDΔintron, and 35S:EVDmU1. (B) Individual 3′ RACE clones from distinct 35S:EVDwt, 35S:EVDΔintron, and 35S:EVDmU1 overexpression lines in the rdr6 background. Blue and red bars display spliced and unspliced 3′ ends and gray areas the cumulative sequence coverage, similar to Figure 3C. Positions are indicated in nucleotides (nt) from the EVD start codon. (C) RNA and protein blot analysis of 35S:EVDwt, 35S:EVDΔintron, and 35S:EVDmU1 overexpression lines in rdr6. Total RNA was consecutively hybridized with RT- and GAG-specific probes (see Fig. 3A) to identify the GAG-POL RNA (red arrow) and shGAG RNA (blue arrows), respectively. The spliced shGAG RNA and an unspliced RNA cryptically terminated inside the intron comigrate (dark blue arrow); a size shift is visible for the unspliced RNA terminating at the endogenous GAG terminator (light blue arrow). (Bottom panel) Western blot analysis conducted with the anti-GAG antibody. (ACT2) ACTIN2 mRNA loading control; (coom.) Coomassie staining of total protein as a loading control. (D) qRT-PCR measurements of the relative expression levels of 35S:EVDwt, 35S:EVDΔintron, and 35S:EVDmU1. (E) Nucleotide and corresponding amino-acid sequence of 35S:GFP-EVDIn/Ter-GUS and 35S:GFP-GUS. (F) 3′ RACE analysis of 35S:GFP-EVDIn/Ter-GUS and 35S:GFP-GUS in the rdr6 background showing spliced and unspliced 3′ ends as in B. The double-headed arrow indicates the EVDIn/Ter sequence also depicted in B. Positions are indicated in nucleotides (nt) from the GFP start codon. (G) Northern blot analysis of alternative RNA isoforms produced from both reporters. The blot was consecutively hybridized with GFP- and GUS-specific probes to detect GFP and full-length GFP-GUS RNA species, respectively. ACTIN 2 (ACT2) mRNA loading control. (H) Relative expression levels of GFP and GUS RNA indicate modulation of GFP-to-GUS ratios. In all graphs, (*) P < 0.05; (**) P < 0.01 (two-sided t-test against corresponding controls); (n) number of biological replicates or individual 3′ RACE clones sequenced; error bars, SE.

Sequences spanning the intron donor site and major premature termination site recapitulate the cotranscriptional regulatory behavior of EVD in an unrelated reporter RNA

The above model assumes that most of the regulatory elements necessary to control the production and balance between the GAG-POL and shGAG RNAs are contained within the ∼850-nt region spanning the EVD intron and the downstream major endogenous terminator site of the shGAG RNA, delineated with double-arrow heads in Figure 4B (35S:EVDwt). To address this question, we set up an artificial system in which the above-mentioned region, coined EVDint/ter, was mobilized between the GFP and GUS sequences of a GFP-GUS transcriptional fusion cloned between the 35S promoter and 35S terminator (Fig. 4E). Transgenic lines mimicking the genomic features of GAG and POL in EVD expressing the original or the modified GFP-GUS fusion were generated and analyzed in the rdr6 background, as before. We found that, compared with the single transcript detected from the unaltered GFP-GUS fusion, the construct modified with the EVDint/ter region produces a short, mostly spliced transcript containing only GFP, in addition to the longer GFP-EVDint/ter-GUS fusion transcript (Fig. 4F,G). This pattern therefore recapitulates entirely the cotranscriptional behavior of the endogenous EVD and 35S:EVDwt, emphasizing yet again the strong interconnection between splicing and termination. This result not only shows that the EVDint/ter region contains all the features required for cognate and concurrent GAG-POL and shGAG RNA production but also indicates that this process is regulated entirely at the RNA level. Furthermore, the process also modulates the balance between GFP- and GUS-containing RNA levels, since the latter is unaffected and the former strongly increases upon expression of 35S:GFP-EVDint/ter-GUS compared with 35S:GFP-GUS (Fig. 4H).

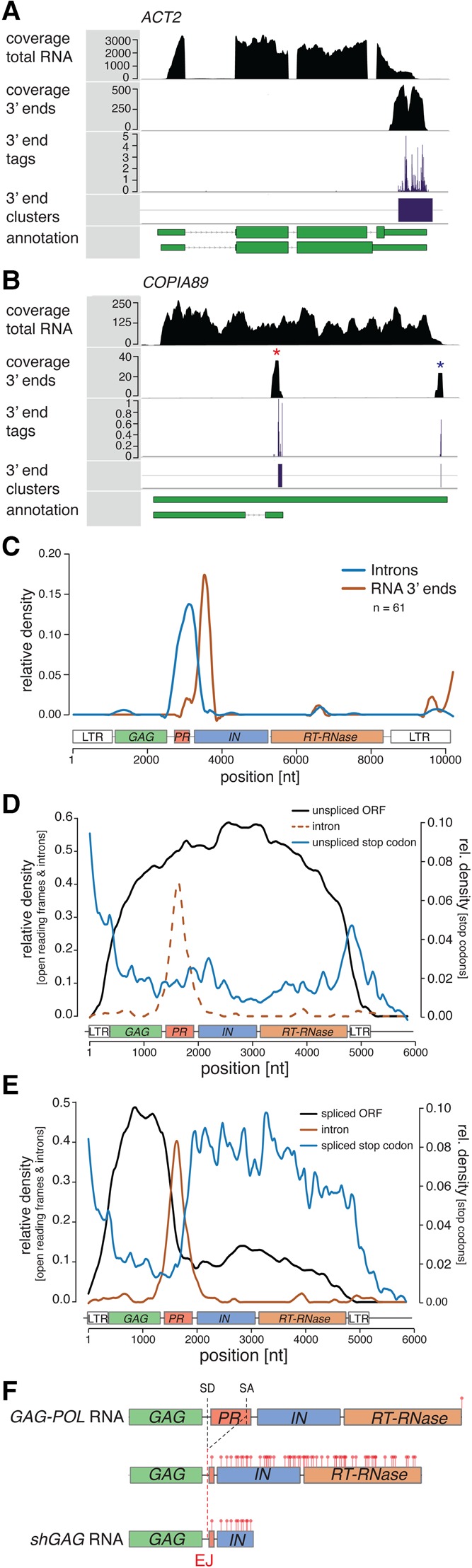

The core processes of EVD RNA splicing and termination are conserved among the Ty1/Copia elements of A. thaliana

Having deciphered the core features of EVD RNA splicing and termination, we decided to investigate if these features are conserved among the Ty1/Copia elements expressed in the WT, ddm1, and met1 backgrounds of A. thaliana. To that aim, a transcriptome-wide mRNA 3′ end landscape was generated using the QuantSeq 3′ end mRNA-seq method adapted for large insert sizes to generate paired-end libraries (http://www.nature.com/nmeth/journal/v11/n12/full/nmeth.f.376.html). In short, mRNAs are reverse transcribed with an oligo-dT primer and the RNA component of the cDNA removed. Random priming and second-strand synthesis then allows for the generation of dsDNA with a well-defined size profile. We found that 3′ end profiles retrieved by this method sharply localize to the very end of annotated Arabidopsis genes, validating the quality of the data (Supplemental Fig. S4B). RNA 3′ end tags were clustered on a distance basis, as exemplified with the major termination site of ACTIN2 (Fig. 5A). Individual clusters obtained with the method would signify distinct termination sites, and indeed, these are observed in Ty1/Copia elements, in which shGAG mRNA and GAG-POL mRNA termination sites are clearly distinguishable, as illustrated with COPIA89 (Fig. 5B). Distribution of the 3′ proximal termination sites of spliced elements’ introns revealed a sharply defined peak located at the beginning of the integrase domain, unravelling the high conservation of premature termination shortly after the intron, as mapped in EVD (Fig. 5C). 3′ RACE conducted on the shGAG mRNAs of seven distinct Ty1/Copia elements could confirm each of the termination sites identified by the transcriptome-wide approach, and showed that the sequenced clones were exclusively spliced, underlining once more the strong link between splicing and termination (Supplemental Fig. S4A). Although less distinctive than their metazoan counterparts, Arabidopsis cleavage and polyadenylation sites have clearly defined properties (Tian et al. 2005; Jan et al. 2011; Sherstnev et al. 2012). These include the putative FIP1 binding site defined by the UUGUUU-like motif, the actual poly(A) signal defined by a AAUAAA-like motif, and an AU-rich upstream sequence element. The 3′ ends of shGAG RNAs from Ty1/Copia elements retain those poly(A)-site properties and nucleotide composition, identifying them as bona fide termination sites. In fact, use of a position-specific scoring matrix further shows that Ty1/Copia element termination sites, as seen for their introns (Supplemental Fig. S2D), are at least as well-defined as the average Arabidopsis mRNA termination site (Supplemental Fig. S4C–F).

Figure 5.

Genome-wide identification of Ty1/Copia shGAG RNA 3′ ends and splicing-induced stop codon generation. (A,B) RNA 3′ end tags were clustered on a distance basis to generate distinct 3′ end clusters, shown here for ACTIN 2 (ACT2; A) and COPIA89 (B). Distinct coverage peaks resulting in two 3′ end clusters appear for shGAG (red asterisk) and GAG-POL (blue asterisk) mRNAs. (C) Density of introns and their most proximal RNA 3′ ends on a multiple sequence alignment of Ty1/Copia elements. (D,E) Relative densities of open reading frames (ORFs), introns, and stop codons found in the genomic sequence of full-length (D) and spliced (E) Ty1/Copia elements. (F) Scheme representing the three possible RNA isoforms produced by Ty1/Copia elements, illustrated here with EVD, as well as the resulting 3′ UTRs and stop codon distribution in red. (SD) splice donor; (SA) splice acceptor; (EJ) exon junction; (n) number of individual elements.

We pointed out that a shared feature of the splicing of EVD and BARE1, two Ty1/Copia elements from distant plant species, is the introduction of a stop codon shortly after the exon–exon junction, via frameshifting (Fig. 1D). As illustrated with EVDmu1, shGAG mRNAs lacking a stop codon owing to compromised splicing cannot be translated into Gag protein (Fig. 4C). We investigated if stop codon introduction via splicing-coupled frameshifting is also conserved among the spliced Ty1/Copia elements of Arabidopsis and is effectively required for functional shGAG mRNA production, as in EVD. We analyzed the density of ORFs and stop codons on the genomic sequence of Ty1/Copia elements generating spliced isoforms. We found that, on unspliced sequences, ORFs span the entire elements and stop codons aggregate in the LTRs, reflecting a GAG-POL mRNA encoding for a full-length polyprotein (Fig. 5D). On spliced sequences, in contrast, ORFs are confined to the GAG domain and a multitude of stop codons accumulate shortly after the intron, spanning the entire POL region (Fig. 5E). Without premature termination, which is intrinsically coupled to splicing in Ty1/Copia elements (Fig. 5C), this extended suite of stop codons would result in a highly unstable mRNA due to activation of RNA quality control (RQC) (Kalyna et al. 2012; Drechsel et al. 2013). Therefore, splicing seems to have two critical roles in generating GAG-only dedicated mRNAs from Ty1/Copia elements: (1) to introduce, via frameshifting, stop codons absent in the unspliced mRNA, thereby allowing GAG translation, and (2) to promote premature termination and polyadenylation as a means to shorten the newly generated 3′ UTR and most likely evade RQC (Fig. 5F).

The shGAG mRNAs of A. thaliana Ty1/Copia elements are overrepresented on polysomes compared with their full-length RNAs

Notwithstanding their unique mode of biogenesis, the above experiments indicate that Ty1/Copia shGAG RNAs are conventional mRNAs, consistent with their efficient translation into GAG, as inferred from the reverse genetic experiments conducted with EVD in Figure 4C. Those experiments also led us to suggest that, on the contrary, the GAG-POL full-length mRNA is barely translated. We thus set out to investigate the molecular basis for these apparent discrepancies in translation efficacy by sequencing polysome-bound mRNAs in two replicates in WT and ddm1 plants. We used a two-step ultracentrifugation protocol allowing separation of the monosomal and polysomal fractions (Supplemental Fig. S5A–C); RNAs associated with the later fractions are considered to undergo active translation. The pooled polysomal and total RNA were subjected to qRT-PCR, distinguishing spliced versus unspliced EVD RNAs. We observed a strong depletion of the EVD GAG-POL mRNA in polysomes compared with total RNA, with the shGAG mRNA remaining, in contrast, unaffected (Fig. 6A). We then used the pooled polysome fractions for QuantSeq library preparation to establish a genome-wide translatome map. As expected from polysome-associated RNA, we observed protein coding genes to be equally prevalent in the polysomal fraction compared with whole-cell extract, whereas noncoding (nc)RNAs and TE transcripts are globally depleted. (Fig. 6B). We specifically quantified the two Ty1/Copia mRNA isoforms and provide here representative examples of the three main situations uncovered by the analysis (Fig. 6C). In the very young EVD element, extensive sequence homology is retained between the two LTRs (Supplemental Fig. S1J). Consequently, the cognate RNA-seq signal corresponding to the shGAG mRNA 3′ end, in the integrase domain, is accompanied by two additional peaks mapping to the 5′ and 3′ LTR, of which only the latter represents the authentic termination site of the GAG-POL mRNA in the 3′ LTR (Fig. 6C). Strikingly, the 3′ LTR signal (GAG-POL mRNA termination) is vastly decreased in polysomes compared with total RNA 3′ ends, whereas the integrase signal (shGAG mRNA termination) remains nearly unchanged in EVD. In COPIA15, in which the two LTRs are sufficiently divergent to be distinguished by RNA-seq, the integrase signal is even higher in polysomes compared with total RNA 3′ ends, while the 3′ LTR signal remains low in both fractions. The third situation is that of exclusively spliced elements, typified by COPIA8A, in which the shGAG mRNA is nearly entirely associated with the polysomes, with otherwise no detectable GAG-POL mRNA in either fraction. A global analysis of Ty1/Copia elements further confirmed the differential loading of shGAG and GAG-POL mRNA onto polysomes (Fig. 6D). We conclude that splicing coupled to transcription termination is a general feature of Ty1/Copia elements in A. thaliana, which enables production of a subgenomic mRNA whose preferential association with polysomes allows for efficient GAG translation.

Figure 6.

The two Ty1/Copia mRNA isoforms differentially associate with polysomes. (A) Relative steady-state levels of EVD spliced and unspliced isoforms found in the total as opposed to polysome fractions. Dots indicate measurements made in the two individual replicates. (B) Log2 accumulation fold change between total RNA and polysome-associated RNA of various RNA classes. (C) RNA 3′ end sequence coverage of mRNAs from total cell extract and polysome-associated mRNAs, showing differential loading of shGAG (red asterisk) and GAG-POL (green triangle) mRNAs of EVD and COPIA15. Note that an additional peak is visible in the EVD 5′ LTR owing to high sequence homology between the two LTRs (purple triangle). (D) Differential association of Ty1/Copia shGAG mRNA and GAG-POL mRNA to polysomes. Read coverages 50 nt downstream from and 300 nt upstream of the respective termination sites were taken into account for quantification. (**) P < 0.01, (***) P < 0.001 (Wilcoxon rank-sum test); (n) number of individual elements analyzed.

Ninety-five percent of EVD-derived siRNAs map to the shGAG subgenomic mRNA in a met1 epiRIL

A study of EVD in an epigenetic recombinant inbred line (epiRIL epi15 F11) (Reinders et al. 2009; Marí-Ordóñez et al. 2013) suggested how de novo integrated and active transposon copies trigger a multistep host genome defense based on RNA silencing. A first antiviral-like PTGS response involving production of 21- to 22-nt siRNAs is largely ineffective against EVD accumulation due to RNA-protective features of the GAG nucleocapsid. Only upon saturation of the PTGS pathway due to EVD proliferation is a successful transcriptional gene silencing (TGS) response activated, hallmarked by the generation of 24-nt siRNAs and cytosine methylation (Marí-Ordóñez et al. 2013). A striking aspect of EVD-derived siRNAs is their discrete distribution along the EVD genome, where they map almost exclusively to the 3′ half of the GAG ORF. We could not escape noticing the striking overlap between this pattern and the shGAG mRNA mapped in the present study. A reanalysis of sequencing reads showed, indeed, that 95% of the 21- to 22-nt and, later, 24-nt siRNAs produced from EVD map almost exclusively to the shGAG subgenomic mRNA. Moreover, a multitude of previously unmapped siRNA spanning the splice junction were identified using a splice-aware RNA-seq mapping software (Fig. 7A). This observation is intriguing given that accumulation of the full-length GAG-POL RNA exceeds by far that of the shGAG mRNA. The expected disproportionate availability of the former to the host silencing machinery would therefore predict an siRNA pattern covering the entirety of the EVD locus. However, EVD siRNAs are amplified and accumulate both as sense and antisense species generated from a long double-stranded RNA produced by the activity of RDR6 (Marí-Ordóñez et al. 2013). It appears, therefore, that the shGAG mRNA, or an RNA derived from it, display one or several specific features not found or barely found in the full-length EVD RNA, which strongly stimulate RDR6 activity. We did not detect a genome-wide correlation between shGAG isoform accumulation and 20- to 21-nt siRNA levels in either the ddm1 or met1 backgrounds, in which the siRNA cohorts spawned from the bulk of reactivated spliced Ty1/Copia elements accumulated at very low levels (Supplemental Fig. S5E), suggesting that this phenomenon is unique to EVD. Collectively, the result therefore suggests that alternative splicing coupled to premature termination, which is at the very core of the Ty1/Copia elements’ genome expression strategy, may, under some circumstances, concurrently form a major stimulus of the host RNA-silencing defense response.

Figure 7.

Spliced subgenomic shGAG mRNAs display many termination codons in long 3′ UTRs, and are specifically targeted by the RNA silencing machinery. (A) We mapped 20- to 24-nt siRNA profile from the EVD locus in epi15 F11 plants mapped with a splice-aware mapping software. Arcs display previously unmapped splice junction siRNA reads. (B) A model showing two concurrent modes of action of the U1 snRNP either repressing premature termination to allow full-length mRNA/genomic RNA synthesis or promoting splicing and subsequent premature termination of the shGAG mRNA. The two generated isoforms, shGAG and GAG-POL, differentially associate with polysomes, allowing proper regulation of protein abundance required for successful VLP formation and transposition. The shGAG mRNA also specifically activates the host silencing response, depicted here in its primary PTGS phase involving 21- to 22-nt siRNAs produced by DLC4 and DCL2, respectively. Note that protection of EVD RNAs due to GAG particle formation allows them to resist PTGS at this stage, as shown by Marí-Ordóñez et al. (2013).

Discussion

Here, we have established the first high-resolution transcriptome and translatome map of the near-entire set of A. thaliana transposons and have implemented a user-friendly genome browser corresponding to the full RNA-seq data set (Supplemental Fig. S6; Supplemental Table S3) to facilitate its exploration (http://www.tetrans.ethz.ch/). The use of this resource enabled us to uncover an elaborate mechanism evolved by a broad spectrum of active Ty1/Copia elements to overcome a major constraint of their condensed genome, i.e., the differential regulation of protein abundance. Our data indicate that Ty1/Copia elements accumulate a spliced and prematurely terminated mRNA solely dedicated to, and necessary for, GAG protein production. Stronger association of this shGAG mRNA with polysomes compared with the full-length GAG-POL RNA facilitates efficient GAG protein production and thereby likely enables the molar excess of the structural GAG over the catalytic POL components required for successful transposition (Fig. 7B).

Despite their peculiarities, Ty1/Copia shGAG mRNAs show clear signs of adaptation to the transcription and splicing machineries of A. thaliana, as illustrated by their intronic base composition and conservation of the 5′ U1 binding site as well as overall intron size, with an average of 300 nt defining the upper limit of A. thaliana mRNA intron lengths. The ∼3-kb-long intron of D. copia elements is also at the upper limit of mRNA intron sizes in this organism, enabling termination to occur naturally in the 3′ LTR. In contrast, the obligatory much smaller size of A. thaliana Ty1/Copia’s intron has apparently driven the emergence of a sophisticated strategy that, in addition to alternative splicing, exploits a specific feature of the host transcriptional machinery, i.e., the recruitment of the U1 snRNP to inhibit premature termination of the unspliced, full-length RNA. This effectively enables production of two alternatively terminated transcripts from a single condensed locus. Alternative transcription termination, as opposed to alternative splicing, is an extremely rare process in A. thaliana (Sherstnev et al. 2012), and only few functional examples are known: prominently, the regulation of FLOWERING LOCUS C by alternative cleavage and polyadenylation of an adjacent gene (Liu et al. 2010). This alternative termination event is specifically regulated by an RNA binding protein (Zhang et al. 2016). If and how exactly such a specific interaction is also required for alternative termination of Ty1/Copias remain to be elucidated.

Tight regulations to accommodate the necessary balance between splicing and suppression of premature termination likely define a broad spectrum of outcomes of genome expression among various Ty1/Copia elements, delineated by two extremes. On one extreme, completely unspliced Ty1/Copia elements would produce vastly suboptimal GAG levels, if at all; on the other, fully spliced elements would always undergo premature termination and only produce shGAG RNA to the detriment of any full-length RNA, as is most likely illustrated with COPIA89 and COPIA8A (Fig. 2E). Both scenarios would lead to the generation of nonautonomous or barely autonomous elements, because both would result in an inability to reverse-transcribe and, hence, to transpose. We note, nonetheless, that the GAG ORFs of the shGAG RNAs of COPIA89 and COPIA8A are not degenerated, suggesting that at least some of these “super-splicers” might undergo positive selection. These could act, perhaps, as abundant sources of GAG possibly exploited in trans by sequence-related active elements, for instance, at early stages of their epigenetic reactivation when GAG levels are probably limiting. How exactly the balance between the two RNA isoforms is established needs to be further defined, but one could envision a system whereby, upon sufficient shGAG mRNA production, the ensuing high levels of GAG could trigger negative feedback regulation of shGAG synthesis; this could increase the levels of the GAG-POL mRNA as a template for the production of the catalytic POL components and as a genomic RNA for reverse transcription.

A key determinant of the necessary molar excess of GAG protein revealed by our study is the differential association to polysomes, and therefore differential translation, of the two RNA isoforms. RNA length could possibly underlie this disparity, but isoform sequencing of polysome fractions in human cells suggests that transcript length only marginally accounts for polysome association, whereas isoforms’ sequence composition and features of the 3′ untranslated region are key determinants (Floor and Doudna 2016). Our own global analysis of reactivated TEs in methylation-deficient A. thaliana has revealed that coding genes are equally represented in the polysome fraction as they are in total cell extracts, whereas, globally, ncRNAs and transposon transcripts are significantly depleted from polysomes (Fig. 6B; Supplemental Table S4). This low association of TE transcripts to polysomes might entail poor coding capabilities reflecting the dominance of certain TE superfamilies with highly degenerated sequences in A. thaliana (Peterson-Burch et al. 2004). A calculation of the longest ORFs for annotated retroelements in the A. thaliana genome indeed revealed that relative ORF length positively correlates with polysome association. Hence, highly degenerated Ty3/Gypsy elements are depleted from the polysomes, whereas LINE, SINE, and Ty1/Copia association is only mildly affected (Supplemental Fig. S5D).

While a case can be made that the splicing of Ty1/Copia elements enables efficient production of an mRNA isoform dedicated to GAG production, the mandatory coupling of this process to premature termination appears as an additional and a priori counterproductive constraint. A likely rationale to this intricate cotranscriptional strategy became apparent upon inspection of the coding potential of each Ty1/Copia mRNA isoform (Fig. 5D–F). On spliced sequences, ORFs are confined to the GAG domain and a myriad of stop codons are found shortly after the intron, spanning the entire POL region (Fig. 5E). Hence, without premature termination, spliced shGAG transcripts of Ty1/Copia elements would bear abnormally long 3′ UTRs replete with premature termination codons (Fig. 5F). These two features strongly predispose Arabidopsis transcripts to degradation via a major RQC mechanism based on nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD) (Kalyna et al. 2012; Drechsel et al. 2013), and it is likely that the same would apply to the EVD-derived RNA, a point deserving further examination. A second apparent drawback of the two-RNA isoforms system was revealed in our reinvestigation of the discrete siRNA pattern generated from epigenetically reactivated EVD in A. thaliana. There was indeed a near-perfect overlap between the spliced, prematurely terminated shGAG subgenomic RNA and the region of EVD-derived siRNA accumulation. This observation suggests how, at least in the case of EVD, an essential feature of the Ty1/Copia elements’ biology is concomitantly used by the host to activate a defense pathway preventing TE proliferation. Owing to the RNA-protective effect of GAG, EVD silencing becomes only effective when a PTGS-to-TGS switch occurs upon saturation of DCL4/DCL2 activity caused by excessive EVD transcription coinciding with a copy number of approximately 40. Saturation enables DLC3-mediated production of 24-nt siRNAs that direct DNA methylation of the corresponding GAG region in the EVD genome. Methylation is then translocated to the LTR via as-yet-undetermined mechanisms, ultimately resulting in TGS (Marí-Ordóñez et al. 2013). Thus, the triggering of RNA silencing by the shGAG subgenomic RNA or species derived thereof could also be interpreted, from an evolutionary perspective, as a TE-advantageous copy number control mechanism. Indeed, overproliferation of any individual element would likely be detrimental to the host, and thus, ultimately, to the element itself.

Our genome-wide survey showed that the accumulation of high levels of shGAG-derived siRNAs is unique to EVD among all the spliced Ty1/Copia elements epigenetically reactivated in Arabidopsis. Given that EVD siRNA production depends on RDR6 activity, this observation suggests that a shGAG mRNA feature(s) that specifically trigger(s) this activity in EVD either is not present or has been lost in the other Ty1/Copia paralogs. Taking into account the second possibility, it is noteworthy that EVD is among the youngest and most active Ty1/Copia elements in A. thaliana (Pereira 2004; Gilly et al. 2014). As such, it may not have resided sufficiently in the genome to dissipate specific foreign qualities displayed by exogenous nucleic acids, perhaps including transgenes, that are suspected to stimulate RDR6-dependent PTGS (Dehio and Schell 1994; Elmayan and Vaucheret 1996). What these non-self features might be, and why the shGAG RNA as opposed to the full-length RNA displays them prominently despite shared identical sequences, will be disclosed later in a separate study.

Methods

Plant material and growth conditions

A. thaliana plants were grown on soil in a growth chamber at 22°C for 2 wk in a 12-h/12-h light cycle and then transferred to a 16-h/8-h light cycle, and individual plants were sampled for inflorescences tissue. Mutant genotypes met1-3, ddm1-2 (seventh generation inbred), and rdr6-12 plants are all derived from the Col-0 ecotype (Jeddeloh et al. 1999; Saze et al. 2003; Peragine 2004).

Plasmid construction and transformation

Multisite gateway technology (Invitrogen) was used for expression vector construction of the EVD and GFP-EVD-GUS constructs using the pB7m34GW backbone (Karimi et al. 2005); see primer sequences used for subcloning (Supplemental Table S5). Clones were introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101, and A. thaliana was transformed using the floral dip method (Clough and Bent 1998). Individual T1 plants with independent transformation events were used for analysis.

RNA blot, qRT-PCR, and protein blot analysis

RNA was extracted from frozen and ground inflorescence tissue with TRIzol reagent (Ambion). High-molecular-weight RNA was blotted after separation of total RNA on a 1.2% agarose gel with 2.2 M formaldehyde, transferring the RNA by capillarity to a HyBond-NX membrane (GE Healthcare). RNA was UV-crosslinked, and radiolabeled probes of EVD, GFP, and GUS made from PCR products using the prime-a-gene kit (Promega) in the presence of [α-32P]-dCTP (Hartmann Analytic) were used for hybridization in PerfectHyb hybridization buffer (Sigma) and detection on a Typhoon FLA 9500 (GE Healthcare) laser scanner.

After DNase I treatment of total RNA, cDNA was synthesized with the Maxima first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo Scientific). qPCR was performed on a LightCycler480 II (Roche) with SYBR FAST qPCR kit (KAPA Biosystems). Ct values were determined by second derivative max of two technical replicates. Relative expression values were calculated by calculating ΔCt values between the target of interest and ACT2 and/or GAPC reference genes. Absolute expression values are determined using a linear model of a standard curve generated from expression values of serial dilutions of reference plasmids.

Protein was extracted by precipitating total protein from the phenolic fraction of TRIzol RNA extraction with the addition of 5 volumes 0.1 M ammonium acetate in methanol. The precipitate was washed with 5 volumes 0.1 M ammonium acetate in methanol twice and resuspended in resuspension buffer (3% SDS, 62.3 mM Tris-HCl atpH 8, 10% glycerol). Following separation on SDS-PAGE, total protein was electroblotted on Immobilon-P PVDF membranes (Milipore), and antibodies (1:2000) were incubated in PBS with 0.1% Tween-20 and 5% nonfat dried milk according to standard blotting procedures (Royer et al. 1986). Antibody detection after incubation with HRP-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (Sigma) was performed with the ECL Western blotting detection kit (GE Healthcare) on a ChemiDoc touch imaging system (Biorad).

Antibody generation

Antibodies for EVD GAG and reverse transcriptase (RT) were raised in rabbits according to the Eurogentec (Eurogentec SA) standard protocols against the following peptides: QETHEEQSQAGSSKG (GAG); AKPARTPLEDGYKVN (RT #1); TGDNKDGIDSTKTFL (RT #2). The efficiency of purified antibodies was tested by comparing transgenic 35S:EVD lines in both WT (Col-0) and rdr6-mutant plants to their nontransformed controls by Western blot (Supplemental Fig. S3).

3′ RACE

Nested 3′ RACE procedures followed manufacturer's recommendations using the FirstChoice RLM-RACE kit (Thermo Fisher). Gene-specific forward primers are found in Supplemental Table S5. Entire 3′ RACE PCR reactions were purified on GeneJET PCR clean-up columns (Thermo Fisher) and cloned into the pJet1.2 vector (Thermo Fisher). Randomly selected colonies were Sanger sequenced (GATC Biotech).

Polysome fractionation

Polysome fractionation on sucrose gradients followed the protocol previously described (Mustroph et al. 2009). Inflorescence tissue was homogenized in polysome extraction buffer (200 mM Tris-HCl at pH 9.0, 200 mM KCl, 25 mM EGTA, 36 mM MgCl2, 5 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 50 mg/mL cycloheximide, 50 mg/mL chloramphenicol, Triton X-100, 1% [v/v], Tween 20, 1% [w/v] Brij-35, 1% [v/v] Igepal CA-630, and 2% [v/v] polyoxyethylene). Lysed tissue was cleared by centrifugation (3200g, 10 min, 4°C). This extract was then centrifuged on a 1.6 M sucrose cushion (170,000g, 3 h, 4°C). Resulting pellets were resuspended in resuspension buffer (200 mM Tris-HCl at pH 9.0, 200 mM KCl, 25 mM EGTA, 36 mM MgCl2, 5 mM DTT, 50 mg/mL cycloheximide, and 50 mg/mL chloramphenicol), separated on a 20%–60% (v/v) sucrose density gradient (237,000g, 1.5 h, 4°C), and 10 fractions were collected. RNA was extracted from individual fractions using the TRIzol method described above.

RNA-seq library preparation

To generate total RNA-seq libraries, RNA was subjected to ribodepletion with Ribo Zero (Illumina), and libraries were prepared using the TruSeq stranded mRNA library prep kit (Illumina). RNA 3′ end libraries were prepared using the QuantSeq 3′ mRNA-Seq library prep kit (Lexogen) adjusted for longer insert lengths by diluting the second-strand synthesis buffer with water in a ratio 1:1. Both library types were paired-end sequenced on a HiSeq 2500 at the Functional Genomic Center Zürich (FGCZ), acquiring 2 × 125-nt reads. sRNA-seq libraries were generated and sequenced on a HiSeq 2500 with an adapted Illumina protocol by Fasteris using the TruSeq SBS kit v3 and acquiring 50-nt-long reads.

Bioinformatics analysis

Data analysis of mRNA-seq libraries comprised of the following workflow. Reads were mapped on the A. thaliana genome (TAIR10), and subsequent quantification and differential analysis was performed using the software Trimmomatic v0.36 (Bolger et al. 2014), STAR v2.5 (Dobin et al. 2012), Rsubread v1.24.2 (Liao et al. 2014), and DESeq2 v1.14.0 (Love et al. 2014). Quality and adequacy of quantification were assessed by reviewing mapping figures and clustering of log-transformed expression levels of individual libraries (Supplemental Fig. S5; Supplemental Table S3). More details about options and specifications used can be found in the Supplemental Methods.

Novel intron annotations were generated by a selection of TE sequences by length (3.5–6 kb), an expression cut-off (baseMean >50), followed by selecting introns entirely located in TE sequences with a minimal junction read coverage (≥5 individual reads). QuantSeq 3′ end mRNA libraries were filtered to exclude internal priming events removing tags carrying a stretch of eight A's or with an AT-content of >90% in the 20 nt downstream from the termination site. Power-law normalization (Balwierz et al. 2009) was employed prior to distance-based clustering with the CAGEr v1.16.0 package (Haberle et al. 2015), using a maximal distance of 50 nt, to obtain RNA 3′ end clusters. More exhaustive descriptions on novel intron annotations and mRNA termination site definitions are in the Supplemental Methods.

Mapping and quantification of sRNA-seq data were refined in a splice-aware manner using STAR v2.5 adapted for the use of short read alignments and Subreads v1.5.1 (Liao et al. 2014). Previously published sRNA-seq data were retrieved from GEO accessions GSE43412 and GSE57191 for epi15 F11 and ddm1, respectively. Options used for mapping and quantification are in the Supplemental Methods.

Multiple sequence alignments were performed using the DECIPHER v 2.2.0 package (Wright 2015). Visualization and statistical analysis of data were performed using R cran (R Core Team 2017). The R packages Gviz v1.18.0 (Hahne and Ivanek 2016), ggplot2 v2.2.0 (Wickham 2009), and beanplot v1.2 (Kampstra 2008) were used for graphical representations. Further specifications of the multiple sequence alignment are described in the Supplemental Methods.

Data access

A web platform based on the Jbrowse genome browser (Skinner et al. 2009) was implemented (http://www.tetrans.ethz.ch/) to facilitate data accessibility. It allows for a simple access to read coverage and actual read alignments of total RNA-seq and 3′ end mRNA-seq libraries originating from both total RNA as well as polysome-associated RNA. Furthermore, normalized 3′ end mRNA tags and clustering information thereof are included. Additionally, raw data of all RNA-seq experiments, including also met1 sRNA-seq, conducted in this work have been submitted to NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO; http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) under accession number GSE93584. Furthermore, Sanger sequencing trace data generated in this study are accessible at the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA; http://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena) under accession number PRJEB21608.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Matthias Hirsch-Hoffmann for his substantial help in establishing the browser implementation for simplified data access. We further thank the entire Voinnet laboratory for technical advice and scientific discussions. This work was supported by a core grant allocated to O.V. by the ETH and, in part, by an advanced fellowship from the European Research Council (Frontiers of RNAi-II, no. 323071).

Author contributions: S.O., O.V., and A.M.-O. conceived the project, designed the experiments, and wrote the manuscript. C.C. performed the polysomal fractionation. S.O. performed all other experiments and the bioinformatic analysis under the guidance of A.S.

Footnotes

[Supplemental material is available for this article.]

Article published online before print. Article, supplemental material, and publication date are at http://www.genome.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gr.220723.117.

References

- Balwierz PJ, Carninci P, Daub CO, Kawai J, Hayashizaki Y, Van Belle W, Beisel C, van Nimwegen E. 2009. Methods for analyzing deep sequencing expression data: constructing the human and mouse promoterome with deepCAGE data. Genome Biol 10: R79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg MG, Singh LN, Younis I, Liu Q, Pinto AM, Kaida D, Zhang Z, Cho S, Sherrill-Mix S, Wan L, et al. 2012. U1 snRNP determines mRNA length and regulates isoform expression. Cell 150: 53–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blevins T, Pontvianne F, Cocklin R, Podicheti R, Chandrasekhara C, Yerneni S, Braun C, Lee B, Rusch D, Mockaitis K, et al. 2014. A two-step process for epigenetic inheritance in Arabidopsis. Mol Cell 54: 30–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. 2014. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30: 2114–2120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JW. 1996. Arabidopsis intron mutations and pre-mRNA splicing. Plant J 10: 771–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang W, Jääskeläinen M, Li S, Schulman AH. 2013. BARE retrotransposons are translated and replicated via distinct RNA pools. PLoS One 8: e72270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clare JJ, Belcourt M, Farabaugh PJ. 1988. Efficient translational frameshifting occurs within a conserved sequence of the overlap between the two genes of a yeast Ty1 transposon. Proc Natl Acad Sci 85: 6816–6820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough SJ, Bent AF. 1998. Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 16: 735–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cokus SJ, Feng S, Zhang X, Chen Z, Merriman B, Haudenschild CD, Pradhan S, Nelson SF, Pellegrini M, Jacobsen SE. 2008. Shotgun bisulphite sequencing of the Arabidopsis genome reveals DNA methylation patterning. Nature 452: 215–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehio C, Schell J. 1994. Identification of plant genetic loci involved in a posttranscriptional mechanism for meiotically reversible transgene silencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci 91: 5538–5542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dobin A, Davis CA, Schlesinger F, Drenkow J, Zaleski C, Jha S, Batut P, Chaisson M, Gingeras TR. 2012. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics 29: 15–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drechsel G, Kahles A, Kesarwani AK, Stauffer E, Behr J, Drewe P, Ratsch G, Wachter A. 2013. Nonsense-mediated decay of alternative precursor mRNA splicing variants is a major determinant of the Arabidopsis steady state transcriptome. Plant Cell 25: 3726–3742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmayan T, Vaucheret H. 1996. Expression of single copies of a strongly expressed 35S transgene can be silenced post-transcriptionally. Plant J 9: 787–797. [Google Scholar]

- Faulkner GJ, Kimura Y, Daub CO, Wani S, Plessy C, Irvine KM, Schroder K, Cloonan N, Steptoe AL, Lassmann T, et al. 2009. The regulated retrotransposon transcriptome of mammalian cells. Nat Genet 41: 563–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Floor SN, Doudna JA. 2016. Tunable protein synthesis by transcript isoforms in human cells. eLife 5: 1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freund M. 2005. Extended base pair complementarity between U1 snRNA and the 5′ splice site does not inhibit splicing in higher eukaryotes, but rather increases 5′ splice site recognition. Nucleic Acids Res 33: 5112–5119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao X, Havecker ER, Baranov PV, Atkins JF, Voytas DF. 2003. Translational recoding signals between gag and pol in diverse LTR retrotransposons. RNA 9: 1422–1430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilly A, Etcheverry M, Madoui M-A, Guy J, Quadrana L, Alberti A, Martin A, Heitkam T, Engelen S, Labadie K, et al. 2014. TE-Tracker: systematic identification of transposition events through whole-genome resequencing. BMC Bioinformatics 15: 377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodall GJ, Filipowicz W. 1989. The AU-rich sequences present in the introns of plant nuclear pre-mRNAs are required for splicing. Cell 58: 473–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson SI, Polycarpou-Schwarz M, Mattaj IW. 1998. U1 snRNP inhibits pre-mRNA polyadenylation through a direct interaction between U1 70K and poly(A) polymerase. Mol Cell 1: 255–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haberle V, Forrest ARR, Hayashizaki Y, Carninci P, Lenhard B. 2015. CAGEr: precise TSS data retrieval and high-resolution promoterome mining for integrative analyses. Nucleic Acids Res 43: e51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahne F, Ivanek R. 2016. Visualizing genomic data using Gviz and bioconductor. In Statistical genomics. Methods in molecular biology (ed. Mathé E, Davis S), Vol. 1418, pp. 335–351. Humana Press, New York. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang CRL, Burns KH, Boeke JD. 2012. Active transposition in genomes. Annu Rev Genet 46: 651–675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin PA, Voytas DF. 2001. Expression and processing of proteins encoded by the Saccharomyces retrotransposon Ty5. J Virol 75: 1790–1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacks T, Power MD, Masiarz FR, Luciw PA, Barr PJ, Varmus HE. 1988. Characterization of ribosomal frameshifting in HIV-1 gag-pol expression. Nature 331: 280–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JP, Lindroth AM, Cao X, Jacobsen SE. 2002. Control of CpNpG DNA methylation by the KRYPTONITE histone H3 methyltransferase. Nature 416: 556–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jan CH, Friedman RC, Ruby JG, Bartel DP. 2011. Formation, regulation and evolution of Caenorhabditis elegans 3′ UTRs. Nature 469: 97–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeddeloh JA, Stokes TL, Richards EJ. 1999. Maintenance of genomic methylation requires a SWI2/SNF2-like protein. Nat Genet 22: 94–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalyna M, Simpson CG, Syed NH, Lewandowska D, Marquez Y, Kusenda B, Marshall J, Fuller J, Cardle L, McNicol J, et al. 2012. Alternative splicing and nonsense-mediated decay modulate expression of important regulatory genes in Arabidopsis. Nucleic Acids Res 40: 2454–2469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kampstra P. 2008. Beanplot: a boxplot alternative for visual comparison of distributions. J Stat Softw 10.18637/jss.v028.c01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karimi M, De Meyer B, Hilson P. 2005. Modular cloning in plant cells. Trends Plant Sci 10: 103–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawler JF, Merkulov GV, Boeke JD. 2001. Frameshift signal transplantation and the unambiguous analysis of mutations in the yeast retrotransposon Ty1 Gag-Pol overlap region. J Virol 75: 6769–6775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao Y, Smyth GK, Shi W. 2014. featureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 30: 923–930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F, Marquardt S, Lister C, Swiezewski S, Dean C. 2010. Targeted 3′ processing of antisense transcripts triggers Arabidopsis FLC chromatin silencing. Science 327: 94–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. 2014. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 15: 550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marí-Ordóñez A, Marchais A, Etcheverry M, Martin A, Colot V, Voinnet O. 2013. Reconstructing de novo silencing of an active plant retrotransposon. Nat Genet 45: 1029–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews GD, Goodwin TJ, Butler MI, Berryman TA, Poulter RT. 1997. pCal, a highly unusual Ty1/copia retrotransposon from the pathogenic yeast Candida albicans. J Bacteriol 179: 7118–7128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mette MF, Aufsatz W, van der Winden J, Matzke MA, Matzke AJM. 2000. Transcriptional silencing and promoter methylation triggered by double-stranded RNA. EMBO J 19: 5194–5201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirouze M, Reinders J, Bucher E, Nishimura T, Schneeberger K, Ossowski S, Cao J, Weigel D, Paszkowski J, Mathieu O. 2009. Selective epigenetic control of retrotransposition in Arabidopsis. Nature 461: 427–430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mourrain P, Béclin C, Elmayan T, Feuerbach F. 2000. Arabidopsis SGS2 and SGS3 genes are required for posttranscriptional gene silencing and natural virus resistance. Cell 101: 533–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustroph A, Juntawong P, Bailey-Serres J. 2009. Isolation of plant polysomal mRNA by differential centrifugation and ribosome immunopurification methods. In Plant systems biology. Methods in molecular biology (Methods and protocols) (ed. Belostotsky D), Vol. 553, pp. 109–126. Humana Press, New York. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peragine A. 2004. SGS3 and SGS2/SDE1/RDR6 are required for juvenile development and the production of trans-acting siRNAs in Arabidopsis. Genes Dev 18: 2368–2379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira V. 2004. Insertion bias and purifying selection of retrotransposons in the Arabidopsis thaliana genome. Genome Biol 5: R79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson-Burch BD, Nettleton D, Voytas DF. 2004. Genomic neighborhoods for Arabidopsis retrotransposons: a role for targeted integration in the distribution of the Metaviridae. Genome Biol 5: R78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quadrana L, Bortolini Silveira A, Mayhew GF, LeBlanc C, Martienssen RA, Jeddeloh JA, Colot V. 2016. The Arabidopsis thaliana mobilome and its impact at the species level. eLife 5: 6919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team . 2017. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria: https://www.R-project.org/. [Google Scholar]

- Reinders J, Wulff BBH, Mirouze M, Marí-Ordóñez A, Dapp M, Rozhon W, Bucher E, Theiler G, Paszkowski J. 2009. Compromised stability of DNA methylation and transposon immobilization in mosaic Arabidopsis epigenomes. Genes Dev 23: 939–950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Royer RE, Deck LM, Campos NM, Hunsaker LA, Vander Jagt DL. 1986. Biologically active derivatives of gossypol: synthesis and antimalarial activities of peri-acylated gossylic nitriles. J Med Chem 29: 1799–1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saze H, Scheid OM, Paszkowski J. 2003. Maintenance of CpG methylation is essential for epigenetic inheritance during plant gametogenesis. Nat Genet 34: 65–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulman AH. 2013. Retrotransposon replication in plants. Curr Opin Virol 3: 604–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shehu-Xhilaga M, Crowe SM, Mak J. 2001. Maintenance of the Gag/Gag-Pol ratio is important for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA dimerization and viral infectivity. J Virol 75: 1834–1841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherstnev A, Duc C, Cole C, Zacharaki V, Hornyik C, Ozsolak F, Milos PM, Barton GJ, Simpson GG. 2012. Direct sequencing of Arabidopsis thaliana RNA reveals patterns of cleavage and polyadenylation. Nat Struct Mol Biol 19: 845–852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sienski G, Dönertas D, Brennecke J. 2012. Transcriptional silencing of transposons by Piwi and maelstrom and its impact on chromatin state and gene expression. Cell 151: 964–980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skinner ME, Uzilov AV, Stein LD, Mungall CJ, Holmes IH. 2009. JBrowse: a next-generation genome browser. Genome Res 19: 1630–1638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian B, Hu J, Lutz CS. 2005. A large-scale analysis of mRNA polyadenylation of human and mouse genes. Nucleic Acids Res 33: 201–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian B, Pan Z, Lee JY. 2007. Widespread mRNA polyadenylation events in introns indicate dynamic interplay between polyadenylation and splicing. Genome Res 17: 156–165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukahara S, Kobayashi A, Kawabe A, Mathieu O, Miura A, Kakutani T. 2009. Bursts of retrotransposition reproduced in Arabidopsis. Nature 461: 423–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turunen JJ, Niemelä EH, Verma B, Frilander MJ. 2012. The significant other: splicing by the minor spliceosome. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA 4: 61–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitte C, Bennetzen JL. 2006. Analysis of retrotransposon structural diversity uncovers properties and propensities in angiosperm genome evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci 103: 17638–17643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voytas DF, Boeke JD. 2002. Ty1 and Ty5 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. In Mobile DNA II (ed. Craig N, et al. ), pp. 631–662. ASM Press, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham H. 2009. ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. Springer, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Wills NM, Gesteland RF, Atkins JF. 1991. Evidence that a downstream pseudoknot is required for translational read-through of the Moloney murine leukemia virus gag stop codon. Proc Natl Acad Sci 88: 6991–6995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright ES. 2015. DECIPHER: harnessing local sequence context to improve protein multiple sequence alignment. BMC Bioinformatics 16: 322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]