Glandular trichomes: from developmental aspects to metabolic engineering approaches.

Abstract

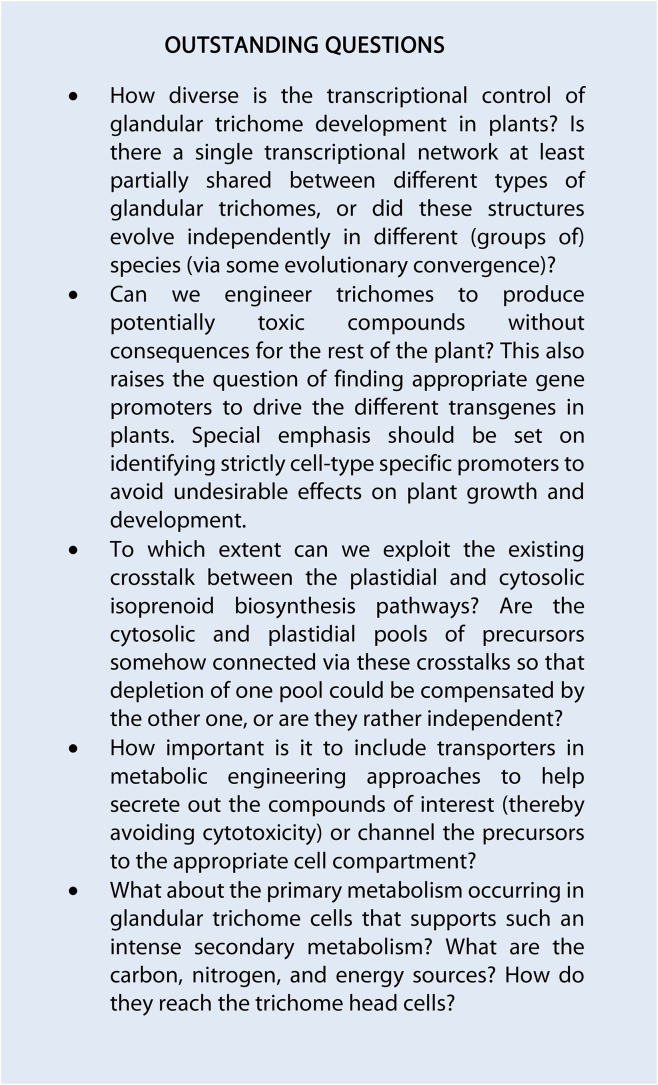

Multicellular glandular trichomes are epidermal outgrowths characterized by the presence of a head made of cells that have the ability to secrete or store large quantities of specialized metabolites. Our understanding of the transcriptional control of glandular trichome initiation and development is still in its infancy. This review points to some central questions that need to be addressed to better understand how such specialized cell structures arise from the plant protodermis. A key and unique feature of glandular trichomes is their ability to synthesize and secrete large amounts, relative to their size, of a limited number of metabolites. As such, they qualify as true cell factories, making them interesting targets for metabolic engineering. In this review, recent advances regarding terpene metabolic engineering are highlighted, with a special focus on tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum). In particular, the choice of transcriptional promoters to drive transgene expression and the best ways to sink existing pools of terpene precursors are discussed. The bioavailability of existing pools of natural precursor molecules is a key parameter and is controlled by so-called cross talk between different biosynthetic pathways. As highlighted in this review, the exact nature and extent of such cross talk are only partially understood at present. In the future, awareness of, and detailed knowledge on, the biology of plant glandular trichome development and metabolism will generate new leads to tap the largely unexploited potential of glandular trichomes in plant resistance to pests and lead to the improved production of specialized metabolites with high industrial or pharmacological value.

Trichomes, the epidermal outgrowths covering most aerial plant tissues, are found in a very large number of plant species and are composed of single-cell or multicellular structures. These structures are divided into two general categories: they can be glandular or nonglandular, depending on their morphology and secretion ability. Glandular trichomes can be found on approximately 30% of all vascular plant species (Fahn, 2000), and in a single plant species, several types of trichomes (both glandular and nonglandular) can be observed. Glandular trichomes are characterized by the presence of cells that have the ability to secrete or store large quantities of secondary (also called specialized) metabolites, which contribute to increasing the plant fitness to the environment (for details, see Box 1).

Two main types of glandular trichomes stand out: peltate or capitate, which differ according to their head size and stalk length. Capitate trichomes typically possess a stalk whose length is more than half the head height, whereas peltate trichomes are defined as short-stalked (unicellular or bicellular stalk) trichomes with a large secretory head made of four to 18 cells arranged in one or two concentric circles. Capitate trichomes are quite variable in their stalk cell number and length, glandular head morphology, as well as secretion pattern and can be classified into various types (Glas et al., 2012).

A key and unique feature of glandular trichomes is their ability to synthesize and secrete large amounts, relative to their size, of a limited number of specialized metabolites: mainly terpenoids (Gershenzon et al., 1992; Gershenzon and Dudareva, 2007) but also phenylpropanoids (Gang et al., 2001; Deschamps et al., 2006; Xie et al., 2008), flavonoids (Voirin et al., 1993; Tattini et al., 2000), methylketones (Fridman et al., 2005), and acyl sugars (Kroumova and Wagner, 2003; Schilmiller et al., 2010; Weinhold and Baldwin, 2011).

Over the long term, the ability to modulate the density and productivity of such secreting structures in plants would be of great biotechnological interest. This requires the identification and characterization of the genes initiating, regulating, and driving the development of such glandular structures. Awareness of, and detailed knowledge on, the biology of plant glandular trichome development and metabolism will generate new leads to turn trichomes into biochemical factories using metabolic engineering approaches (Tissier, 2012a), tap their largely unexploited potential in plant resistance to pests, and lead to the improved production of important specialized metabolites (Lange and Turner, 2013; Lange et al., 2011).

PLANT GLANDULAR TRICHOMES: AN INTERESTING PARADIGM TO STUDY PLANT CELL DIFFERENTIATION

To modulate the density of glandular trichomes in the epidermis or their productivity for biotechnological purposes, a detailed understanding of the molecular genetic framework governing their development and patterning in the plant epidermis would be beneficial. Glandular trichomes have been studied mostly to decipher the biochemical pathways of the compounds they produce and secrete (Champagne and Boutry, 2013; Lange and Turner, 2013) and, thereby, have contributed to advancing our understanding of the secondary metabolism in plants.

A Detailed Understanding of Glandular Trichome Initiation and Development Is Currently Missing

All multicellular organisms face the challenge of coordinating cell proliferation with cell differentiation and patterning. Defects in this coordination can lead to incorrect tissue formation, malformed organs, and cancerous growth. Glandular trichomes exemplify this coordination challenge: they are elaborate, highly organized, and polarized cell structures whose morphogenesis is modulated by an intricate array of molecular processes controlling the different steps of their patterning on the leaf epidermis and subsequent differentiation. Therefore, glandular trichomes can be used as a paradigm to tackle basic questions about the development and differentiation of specialized multicellular secretory structures in plants.

A complete circuit for glandular trichome formation and patterning in the leaf epidermis will require a sound understanding of their initiation process in the plant protodermis and of the subsequent developmental steps leading to the formation of a polarized and specialized multicellular structure, of the genes that regulate cell division, participate in cell signaling, and promote specialized cell fate (Fig. 1). It also requires an understanding of how this developmental regulatory network affects cellular biological targets such as the core cell cycle machinery. A particularly large gap in our current knowledge is the identification of regulators of entry into the glandular trichome cell fate and of progression through the pathway.

Figure 1.

Glandular trichome initiation and development, a process with many unknowns. A differentiating protodermal cell integrates both environmental and endogenous signals. Such signal integration results in the selection of a pool of trichome cell precursors that will initiate a specific developmental program. In these trichome initials, cell-specific transcriptional control of gene expression and cell cycle regulation results in the onset of a controlled cell division and trichome morphogenesis program, most of which is still not so well understood in the case of glandular trichomes. It probably also involves some cell-cell signaling promoting the one cell-spacing rule, which allows a specific patterning of trichomes in the epidermis. Morphogenesis of the trichome glandular head also necessitates extensive remodeling of the cell wall. The extent of endoreduplication in glandular trichomes is still mostly uncharacterized. The illustration shows a modified confocal image of a long glandular trichome initial from N. tabacum. Chloroplasts are shown in green, propidium iodide-stained cell walls in magenta, and nuclei in cyan.

Research on nonglandular trichomes has been very fruitful in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana). It has generated a developmental framework for unicellular trichome formation and identified over 30 genes involved in the initiation and development of nonglandular trichomes. We chose not to review the development of trichomes in Arabidopsis, as this has been thoroughly reviewed (Balkunde et al., 2010; An et al., 2011; Tominaga-Wada et al., 2011; Pattanaik et al., 2014; Matías-Hernández et al., 2016). Unlike the situation of Arabidopsis, which contains a single type of unicellular, nonglandular trichome, our understanding of the molecular genetic aspects of glandular trichome development is still in its infancy but currently improving due to recent progress in omics and genome-editing technologies as well as to a growing focus from several research teams to characterize this process in different plant species (Li et al., 2004; Dai et al., 2010; Bosch et al., 2014; Bergau et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2016). The (draft) genome sequences of a number of plant species with glandular trichomes are now available. A nonexhaustive list includes different tomato species (Solanum lycopersicum and Solanum pimpinellifolium [Tomato Genome Consortium, 2012] and Solanum pennellii [Bolger et al., 2014]), potato (Solanum tuberosum [Xu et al., 2011]), cucumber (Cucumis sativus [Huang et al., 2009]), tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum [Sierro et al., 2014; Edwards et al., 2017]) and its related species (Nicotiana sylvestris and Nicotiana tomentosiformis [Sierro et al., 2013]), hot pepper (Capsicum annuum [Kim et al., 2014]), mint (Mentha longifolia [Vining et al., 2017]), cannabis (Cannabis sativa [van Bakel et al., 2011]), and hop (Humulus lupulus [Natsume et al., 2015]).

Since most of them can be genetically transformed, studying the molecular genetics of trichome development in these species has become much easier (among others by using genome-editing or RNA interference technologies). Particularly for species where genetics is poorly developed (e.g. mint), the combination of transcriptomics at different stages of trichome development (see below) and of genome-editing or RNA interference technology should be a powerful approach to address the function of candidate genes.

Trichome-Specific Data Exist, But Cell Stage-Specific Data Are Crucially Needed to Advance Our Understanding of Glandular Trichome Development

Extensive glandular trichome-specific EST resources were generated for a variety of (nonmodel) plant species (Dai et al., 2010; Tissier, 2012b; Soetaert et al., 2013; Chen et al., 2014; Jin et al., 2014; Trikka et al., 2015; Akhtar et al., 2017). Dedicated trichome-related open-access resources exist that help researchers mine this vast and increasing amount of trichome-related data. One such resource is the TrichOME database (Dai et al., 2010), which hosts functional omics data, including transcriptomics (ESTs/unigene sequences), metabolomics (mass spectrometry-based trichome metabolite profiles), as well as trichome-related genes curated from the published literature from various species. These include members of Lamiaceae (Mentha piperita, Salvia fruticosa, Cistus creticus, and Ocimum basilicum), Solanaceae (Nicotiana benthamiana, N. tabacum, Solanum habrochaites, S. lycopersicum, and S. pennellii), Asteraceae (Artemisia annua), Fabaceae (Medicago sativa and Medicago truncatula), and Cannabaceae (C. sativa and H. lupulus).

These trichome-specific expression data are particularly useful to identify trichome-specific genes involved in particular biosynthetic pathways as well as in other trichome-related processes. A key question is how to extract the most significant data out of this massive and growing amount of bulk information to advance our understanding of specific aspects of glandular trichome biology (Tissier, 2012a). From a developmental perspective, one of the main limitations of such resources is that most of these trichome-specific expression data were derived from mature glandular trichomes (which are usually easier to isolate than developing structures) or from a population of trichomes at mixed developmental stages. Indeed, glandular trichome initiation and differentiation occur at different times in different locations within a single leaf. Therefore, even very young leaves contain a trichome population of mixed developmental stages (Bergau et al., 2015). Given the way most EST resources were generated up to now, the expression of genes playing a role in early developmental steps may be, in the best case, underestimated or, in the worst case, even not detected. This is particularly the case of genes active in the initiation phase (selection of trichome initials) or early in development.

In addition to trichome-specific EST resources, numerous glandular trichome-specific gene promoters have been reported in the literature for a variety of plants, including (but not restricted to) Antirrhinum majus, A. annua, C. sativus, H. lupulus, Mentha spp., N. tabacum, S. lycopersicum, and S. habrochaites (Okada and Ito, 2001; Wang et al., 2002, 2011, 2013; Gutiérrez-Alcalá et al., 2005; Liu et al., 2006; Jaffé et al., 2007; Kim et al., 2008; Shangguan et al., 2008; Ennajdaoui et al., 2010; Choi et al., 2012; Sallaud et al., 2012; Spyropoulou et al., 2014; Kortbeek et al., 2016; Laterre et al., 2017; Vining et al., 2017; for review, see Tissier, 2012b). It is worth noting that most of these trichome-specific promoters are active in mature glandular trichomes (mostly in glandular cells at the tip of the trichome). Their activity during early trichome development has been barely analyzed.

Molecular data pointing to genes playing a specific role in glandular trichome development already exist, especially concerning some transcription factors, cell cycle regulators, as well as receptors involved in phytohormone-induced signaling cascades. Several transcription factors belonging to different protein families and playing a role in glandular trichome development have indeed been identified: AmMIXTA, a MYB transcription factor from A. majus whose ectopic expression in tobacco induces the development of additional long glandular trichomes (Glover et al., 1998); GoPGF, a basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) transcription factor from Gossypium spp., acting as a positive regulator of glandular trichome formation, its silencing leading to a completely glandless phenotype (Ma et al., 2016); AaHD1, a homeodomain-Leu zipper transcription factor required for jasmonate-mediated glandular trichome initiation in A. annua (Yan et al., 2017); AtGIS, a C2H2 zinc-finger transcription factor from Arabidopsis whose ectopic expression in tobacco regulates glandular trichome development through GA3 signaling (Liu et al., 2017); AaMYB1, a MYB transcription factor from A. annua whose overexpression induces the formation of a greater number of trichomes (Matías-Hernández et al., 2017); and CsGL3, an HD-Zip transcription factor whose mutation leads to a glabrous phenotype in cucumber (Cui et al., 2016).

In tomato, several genes required for the proper development and function of different types of glandular trichomes have been reported. The woolly (Wo) gene, encoding a class IV homeodomain-Leu zipper protein homolog to the Arabidopsis GL2, and a B-type cyclin gene, SlCycB2 (possibly regulated by Wo), control the initiation and development of type I trichomes. Mutant alleles of Wo triggered a hairy phenotype due to the overproduction of type I trichomes, while suppression of Wo or SlCycB2 expression by RNA interference decreased their density in tomato (Yang et al., 2011a, 2011b). Another mutation (hairless) affects the SRA1 (Specifically Rac1-Associated protein) subunit of the WAVE regulatory complex. SRA1 controls the branching of actin filaments and is required for the normal development of all trichome types of tomato, which suggests that proper actin-cytoskeleton dynamics is a basal requirement for normal trichome morphogenesis (Kang et al., 2016). Mutations of some enzymes involved in secondary metabolism also impact trichome density and/or the metabolic activity of glandular trichomes. For example, in the anthocyanin-free mutant, loss of function of the chalcone isomerase (SlCHI1) triggers a reduction of type VI trichome density and metabolic output (Kang et al., 2014), while down-regulation of DXS2, a methylerythritol 4-phosphate (MEP) enzyme, increases their density (Paetzold et al., 2010). The molecular mechanisms through which these genes affect trichome density are currently unknown.

The tomato Wov allele was shown to promote abnormal multicellular trichome differentiation when ectopically overexpressed in N. tabacum (Yang et al., 2015). This hints at conserved transcriptional networks among Solanaceae species. However, the trichomes in this Wov overexpressor line failed to develop glandular heads and appeared as rather aggregated and undifferentiated structures. Whether a WD40-bHLH-MYB regulatory mechanism similar to the one in Arabidopsis also controls glandular trichome development in Solanaceae is still unclear (Serna and Martin, 2006; Yang et al., 2015). A recent RNA-sequencing analysis of N. tabacum trichomes showed that orthologs of Arabidopsis genes involved in trichome formation via the WD40-bHLH-MYB regulatory mechanism (such as TTG1, GL2, GL3, and several MYB transcription factors) are expressed in these structures (Yang et al., 2015). However, their transcriptional levels were not altered significantly in response to the overexpression of a Wov transgene, which induced a clear trichome proliferation phenotype. On the contrary, homologs of genes (Wo and SlCycB2) involved in trichome formation in asterids (Yang et al., 2011a, 2011b) were significantly up-regulated in Wov transgenic N. tabacum plants (Yang et al., 2015).

The differentiation of long-stalked glandular trichomes may be initiated and controlled in N. tabacum by the activity of another MYB transcription factor. Indeed, ectopic expression of MIXTA from A. majus (Glover et al., 1998) or of its Gossypium hirsutum ortholog CotMYBA (Payne et al., 1999) resulted in the development of excess long-stalked trichomes. Therefore, it is likely that another unidentified N. tabacum MYB gene, an ortholog to AmMIXTA and CotMYBA, plays a role in the development of long-stalked glandular trichomes in this species. Whether this MYB gene needs to be part of a regulatory complex to initiate and promote glandular trichome development is not yet known.

Five trichome-related mutants of the genes CsGL3, TRIL, MICT, TBH, and CsGL1, all of them encoding homeodomain-Leu zipper transcription factors from different subfamilies, have been reported in C. sativus (Chen et al., 2014; Li et al., 2015; Pan et al., 2015; Zhao et al., 2015; Cui et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2016b). Based on the observed phenotypes, a molecular mechanism underlying the development of multicellular trichomes in this species has been proposed in a recent review (Liu et al., 2016) and seems to confirm that the transcriptional control of multicellular trichomes in C. sativus differs from the one observed in Arabidopsis.

The development of glandular trichomes is tightly regulated by the integration of diverse environmental and endogenous signals. In this respect, some phytohormones, especially jasmonate (JA) and possibly GAs, elicit glandular trichome development via signaling cascades and the activation of trichome-specific transcriptional regulators (Li et al., 2004; Koo and Howe, 2009; Bose et al., 2013; Bosch et al., 2014; Tian et al., 2014; Liu et al., 2017; Yan et al., 2017). In Mentha arvensis, exogenous application of GA resulted in a moderate increase in trichome density and diameter of the gland, suggesting a positive, although moderate, effect of GA on trichome initiation and development in mint (Bose et al., 2013). For example, reduced JA levels (through silencing of OPR3, a key enzyme in the biosynthesis of the precursor of JA) led to impaired glandular trichome development in tomato: the density of type VI trichomes was reduced drastically, and their metabolite content was different from that of the wild type (Bosch et al., 2014). The JA receptor JASMONIC ACID INSENSITIVE1, the tomato ortholog of the ubiquitin ligase CORONATINE INSENSITIVE1 in Arabidopsis, is involved in this JA-mediated signaling cascade (Li et al., 2004; Katsir et al., 2008; Kang et al., 2010; Bosch et al., 2014). It remains to be investigated whether a synergistic effect between GA and JA signaling, similar to that observed in Arabidopsis (Qi et al., 2014), also promotes glandular trichome development.

Time-Course Analysis of Glandular Trichome Development Coupled to Cell Type- and Stage-Specific Expression Data as a Way to Advance Our Understanding of Glandular Trichome Development

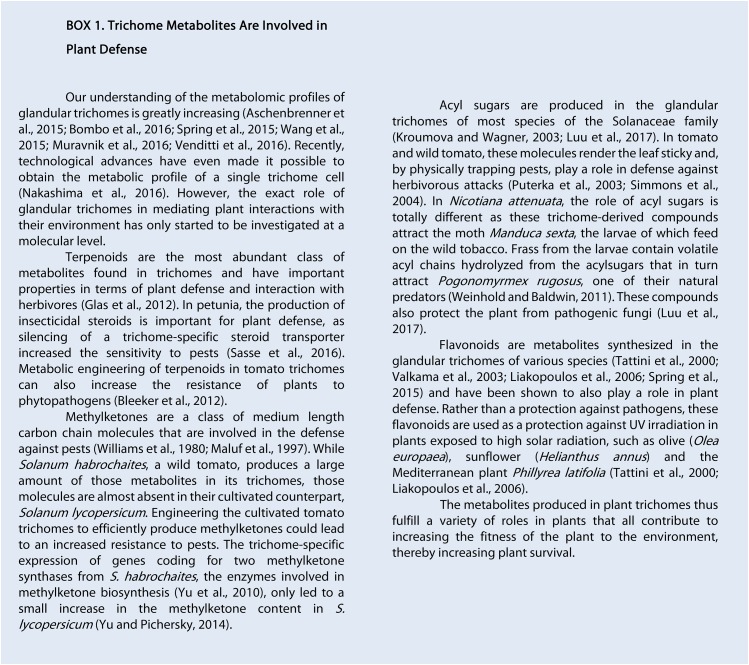

The development of multicellular glandular trichomes proceeds through the enlargement of single epidermal cells, followed by several cell divisions to generate a structure perpendicular to the epidermal surface (Fig. 2), and specific types of glandular trichomes seem to have a well-defined developmental plan (Tissier, 2012a; Bergau et al., 2015). This highly regulated differentiation program also includes a polarized and localized cell wall lysis and remodeling (Bergau et al., 2015).

Figure 2.

Glandular trichome initiation and development in N. tabacum. A to F, Confocal microscopy images showing the early steps of glandular trichome development. The number of cells forming the developing glandular trichome is shown at the bottom of each frame. A differentiating protodermal cell enlarges and forms a protuberance (A), the cell nucleus migrates to the tip of the protuberance (B), and cell division takes place (C), forming a structure made of two cells (D). The upper cell protruding from the epidermis then undergoes an asymmetric division, forming one large cell (which will form the multicellular stalk after several rounds of controlled cell division) and one small cell (which will give rise to the multicellular glandular head; E). A developing trichome made of five cells is shown in F. Scale bars, 20 μm. Magenta represents cell wall (propidium iodide staining), cyan represents nuclei (4',6-Diamidine-2'-phenylindole staining), and green represents chloroplasts (chlorophyll a autofluorescence). G, Scanning electron micrograph showing the typical cell architecture of a mature long glandular trichome.

Within a given plant species, it would be interesting to dissect the developmental sequence of glandular trichome formation (including a time-course analysis) and to sort the cells at specific stages using marker-assisted cell sorting. The difficulty resides in the specific isolation of cells at early developmental stages. Recently, flow cytometry was used to specifically separate young and mature type VI trichomes from the wild tomato species S. habrochaites based on their distinct autofluorescence signals. This allowed the analysis of their transcriptomic and metabolomic profiles in a cell stage-specific way (Bergau et al., 2016).

Such systematic dissection of the development of glandular trichomes seems very promising but could be refined. Ideally, instead of autofluorescence (which may span various developmental stages), a series of trichome-specific transcriptional promoters driving the expression of a fluorescent marker (used as a cell stage marker) and closely associated with well-defined developmental stages should be used. Such genetic resources are not yet available in the field of glandular trichome development. Focus should be set on identifying markers of entry into the glandular trichome pathway as well as those labeling subsequent early differentiation steps. Some published gene promoters, like the one of AmMYBML3 (Jaffé et al., 2007), are already known to specifically label developing trichomes and could be used to drive the expression of a fluorescent reporter protein. Flow cytometry-assisted cell (or nucleus) sorting would then permit us to characterize the transcriptomic changes in a stage-specific way, in a manner similar to what was done to characterize stomatal development (Adrian et al., 2015). In an iterative fashion, the data could be mined to identify additional marker genes, so that only a few markers are necessary to initiate such transcriptomic studies. As an alternative approach, ectopic overexpression of some transcription factors is known to induce glandular trichome development (Payne et al., 1999; Yang et al., 2015). Inducible overexpression of such transcription factors could be used in RNA-sequencing assays as a molecular switch to identify genes acting during early developmental stages (Yang et al., 2015) that, in turn, could be used as cell stage markers. Further research is definitely needed to identify key genes driving the postembryonic development of glandular trichomes and to generate a molecular toolbox facilitating more applied genetic engineering approaches.

Glandular Trichome Development: A Diversity of Model Species

The field of glandular trichome development lacks a unique and robust model system. This is partly due to the difficulty of finding an appropriate model system. Glandular trichomes are extremely diverse in terms of shape, cell number, and type of secreted compounds and may not be the result of a single evolutionary event (Serna and Martin, 2006). This implies that their development may not be under similar transcriptional control in different plant families or even within a single plant species between different trichome types (Serna and Martin, 2006). The current view is that no single species can serve as a unique model to study the biology of glandular trichomes but that certain species or families of species progressively emerge as references for certain types of trichomes, such as Lamiaceae for peltate trichomes or Solanaceae for capitate trichomes, as suggested by Tissier (2012a). So far, published data suggest that multicellular trichome formation probably occurs through different transcriptional regulatory networks from those regulating trichome formation in Arabidopsis, so mere orthologous relationships may not be inferred (Payne et al., 1999; Serna and Martin, 2006; Yang et al., 2015; Liu et al., 2016).

TURNING GLANDULAR TRICHOMES INTO CHEMICAL FACTORIES

Plant specialized metabolites have been used for centuries as a source for fragrances and medicine. Since the discovery of their molecular structures and the elucidation of their biosynthesis pathways, breeders and chemists have been trying to select the best compounds by crossing species and varieties. For small molecules, chemical synthesis is another option once the structure of the molecule has been determined. However, the size and complexity of the stereochemistry of some plant metabolites make their chemical synthesis extremely complicated and expensive.

The rise of molecular genetics and a better understanding of the genomes has changed the way breeders work: they now use molecular genetic screening approaches to help them select the best breeding candidates and descendants. This speeds up the selection process and optimizes the breeding program.

Among plant specialized metabolites, terpenoids are the most abundant in term of quantity and diversity (for review, see Croteau et al., 2000; Bouvier et al., 2005; Gershenzon and Dudareva, 2007). Some of them are renowned not only for their economic value but also for their molecular complexity.

Metabolic engineering of terpenoids emerged as a new method to produce naturally occurring products. Microorganisms have been heavily used for the heterologous expression of plant metabolites (for review, see Kirby and Keasling, 2009; Keasling, 2010; Marienhagen and Bott, 2013), and at present, plants also have become a host of interest for the heterologous or homologous production of some plant specialized metabolites (for review, see Aharoni et al., 2005; Dixon, 2005; Wu and Chappell, 2008).

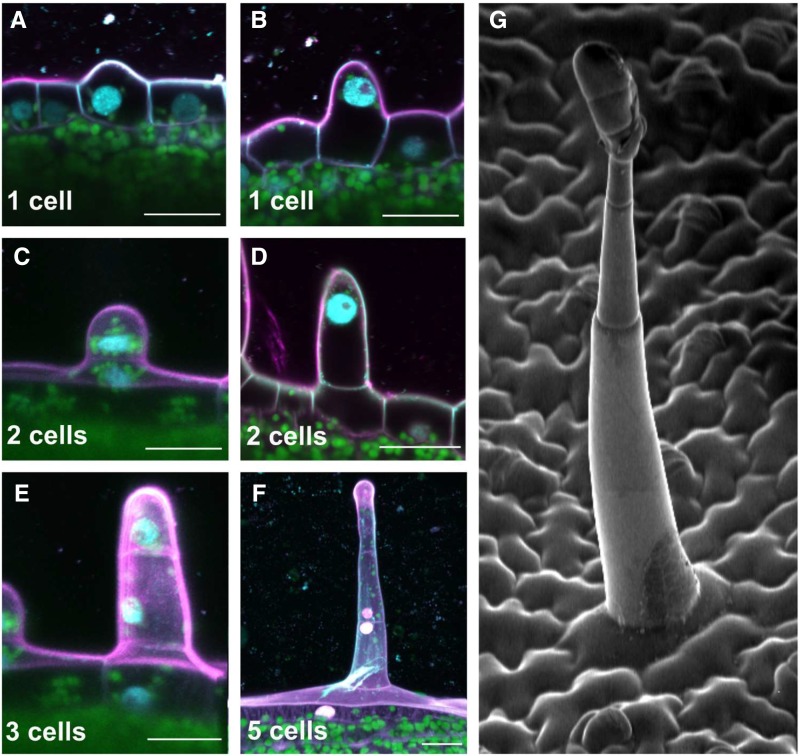

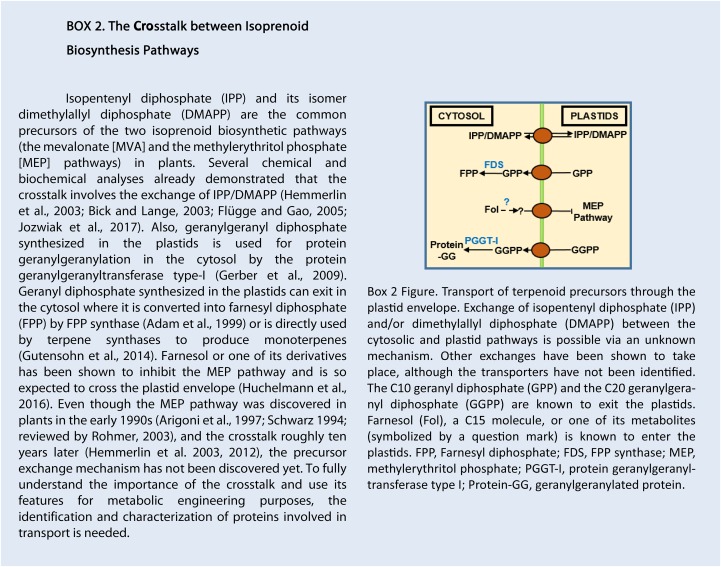

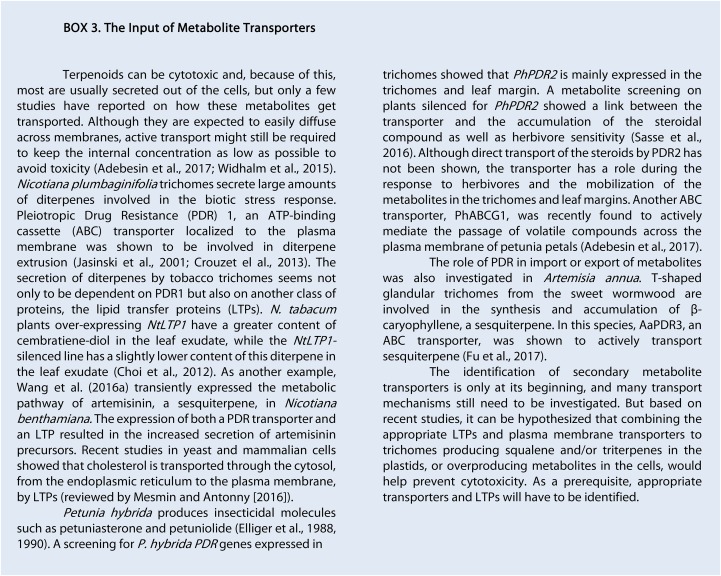

The biosynthesis of isoprenoids in plants is unique, and many reviews have already covered the different aspects of their production and regulation (Bouvier et al., 2005; Hemmerlin et al., 2012; Lipko and Swiezewska, 2016). Plants synthesize the common precursor for isoprenoids, isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP), and its allylic isoform dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP) by two distinct and compartmentalized pathways, the cytosolic mevalonate (MVA) pathway and the plastidial MEP pathway (Fig. 3). Specialized terpenoids are generally synthesized by either the MEP or the MVA pathway depending on their length: sesquiterpenes (C15) and triterpenes (C30) mainly derive from the MVA pathway, while monoterpenes (C10) and diterpenes (C20) derive from the MEP pathway.

Figure 3.

Isoprenoid metabolism in N. tabacum cells. The red square represents the major MEP isoprenoid metabolism in plastids of developed trichomes. Phytohormones are indicated in blue and specialized metabolites in violet. ABA, Abscisic acid; FPP, farnesyl diphosphate; GGPP, geranylgeranyl diphosphate; GPP, geranyl diphosphate.

Metabolic Engineering in N. tabacum

N. tabacum is an interesting model system for metabolic engineering of terpenoid compounds because it synthesizes an important pool of natural precursors (IPP/DMAPP) and, besides the essential metabolites derived from the isoprenoid biosynthesis pathways, it produces a very high amount of a limited range of specialized metabolites. These consist of two types of terpenoids, namely sesquiterpenes (Back and Chappell, 1996; Starks et al., 1997; Ralston et al., 2001), as phytoalexins specifically produced in response to a pathogen attack (Stoessl et al., 1976), and diterpenes, constitutively synthesized and secreted by the head of glandular trichomes (Keene and Wagner, 1985; Kandra and Wagner, 1988; Guo and Wagner, 1995; Wang and Wagner, 2003; Fig. 3). Capsidiol, one of the main phytoalexin sesquiterpenes produced in response to a fungal attack, and cembratriendiol, one of the main diterpenes found in the cuticle, derive from the MVA and the MEP pathway, respectively (Huchelmann et al., 2014). Both types of metabolites are not required for the growth and development of the plants and do not involve a complex metabolic pathway. Changing the fate of the metabolic fluxes normally used for sesquiterpene and diterpene production looks, in theory, quite simple. As the phytoalexin sesquiterpenes are only synthesized in response to a pathogen attack, the main pool of terpenoid precursors available under normal conditions is that involved in diterpene synthesis.

Terpenoid Engineering with Constitutive and Ubiquist Promoters

The metabolic engineering of tobacco plants to produce various terpenoids is widely described, and reviews already covered the methods and the final metabolic profiles (for review, see Verpoorte and Memelink, 2002; Lange and Ahkami, 2013; Moses et al., 2013). Most of the engineered metabolites were synthesized using the original precursor pools, derived from the MEP pathway for monoterpenes and diterpenes and from the MVA pathway for sesquiterpenes and triterpenes. Promoters used to drive expression of the transgenes were ubiquist and constitutive. Although successful, the amount of metabolites produced in transgenic tobacco lines is usually relatively low (in the range of a few ng g−1 fresh weight; Lücker et al., 2004; Wei et al., 2004; Farhi et al., 2011) compared with the endogenous production of capsidiol (up to 100 µg g−1 fresh weight; Dokládal et al., 2012) or of diterpenes (up to 75 µg cm−2 depending on the variety; Severson et al., 1984). To be economically viable, the engineering of terpenoids in plants should reach yields comparable to those occurring naturally.

As mentioned previously, sesquiterpenes (C15) and triterpenes (C30) are considered to derive from the (cytosolic) MVA pathway, while monoterpenes (C10) and diterpenes (C20) are derived from the (plastidial) MEP pathway. However, such a distinction is actually not so strict, given the existence of cross talk between the MVA and MEP pathways, which consists of an exchange of prenyl diphosphates between the cytosol and the plastids (for review, see Hemmerlin et al., 2012). More and more metabolites have been shown not to derive from a strictly cytosolic or plastidial pool of precursors, but the exact way the cross talk works is still unclear (Box 2). As an example, sesquiterpenes can be synthesized using a plastidial pool of IPP (Dudareva et al., 2005; Bartram et al., 2006). Monoterpenes and diterpenes also can have mixed origins (Itoh et al., 2003; Wungsintaweekul and De-Eknamkul, 2005; Hampel et al., 2007).

New strategies emerged for the engineering of terpenoids in plants, which consisted of targeting the overexpressed enzymes to different subcellular localizations to take advantage of either the MVA- or the MEP-derived pool of precursors (Wu et al., 2006). Using such a strategy, the engineering of sesquiterpenes and monoterpenes was monitored in tobacco (Wu et al., 2006). To produce sesquiterpenes (patchoulol or amorpha-4,11-diene), those authors expressed in tobacco the corresponding terpene synthase and a farnesyl diphosphate synthase fused (or not) to a chloroplast-targeting sequence to exploit either the MEP- or the MVA-derived pool of precursors, respectively. In this pioneering study, expression of the transgenes was driven by ubiquist promoters (a different one for each transgene). Addressing the enzymes to the cytosol only led to a low yield of sesquiterpenes (a few ng g−1 fresh weight, as in previous studies), while addressing the enzyme to the plastids (to take advantage of the MEP-derived pool of IPP/DMAPP) led to a much higher yield (up to 25 µg g−1 fresh weight). Those impressive results are also quite surprising, as sesquiterpenes are synthesized naturally in the cytosol, while the engineered production is higher when the enzymes are localized in plastids. Monoterpene production in the cytosol was achieved using the same strategy to express the monoterpene synthase and the geranyl diphosphate synthase. However, in this case, the localization of the enzymes seemed to be less important, as both engineering strategies (using the MVA- and the MEP-derived precursors) led to roughly the same amount of R-(+)-limonene (400–500 ng g−1 fresh weight; Wu et al., 2006).

Modifying the fate of isoprenoid precursors can lead to severe phenotypes, which might be expected given the importance of isoprenoids in plant growth and development and the fact that expression was ubiquist. Tobacco lines producing the highest quantity of sesquiterpenes were indeed severely affected: they exhibited chlorosis and dwarfism. This phenotype also was observed in metabolic engineering of the ginsenoside saponin in tobacco (Gwak et al., 2017). In this case, production of the saponin led to a severe phenotype, including dwarfism, change in flower and pollen morphology, and impaired seed production (Gwak et al., 2017). Similarly, dwarfism was observed upon metabolic engineering of tobacco chloroplast to produce artemisinic acid (Saxena et al., 2014). All these approaches used ubiquist promoters to drive expression of the transgenes. Because of the similarity of the phenotypes observed (dwarfism, chlorosis, and decreased seed production) between the different reports, cytotoxicity of the new metabolites is probably not the only cause. The problem could lay in the constitutive expression of transgenes, which might result in plant depletion of its essential terpenoid precursors (IPP/DMAPP). For plant metabolic engineering to be efficient, there is a necessity to better control the spatiotemporal expression of the transgenes. One strategy to limit the effect of sinking essential IPP pools consists of specifically targeting the expression of the genes in a cell type-specific way. In this respect, glandular trichomes are an ideal expression system.

Terpenoid Engineering Specifically in Trichomes

From a metabolic point of view, glandular trichomes are of particular interest, as they are involved in the synthesis, storage, and/or excretion of specialized metabolites, making these compounds easily available. The carbon metabolism of glandular trichomes in Solanaceae has evolved to support high metabolite production (Balcke et al., 2017). Some genera, such as Nicotiana, produce up to 15% of their leaf biomass in the trichomes (Wagner et al., 2004). The C20 terpenoids are exported to diffuse within the cuticle and mediate resistance to insects and fungi (Chang and Grunwald, 1976; Severson et al., 1984; Wang and Wagner, 2003; Sallaud et al., 2012). Rerouting the diterpene production from cembrane and labdane types (naturally produced in tobacco) to other diterpenes has been performed by addressing the terpene synthase directly to the plastids with a trichome-specific promoter.

Diterpene Engineering

One of the best examples is the heterologous production of taxadiene in trichomes of the wild tobacco N. sylvestris (Rontein et al., 2008; Tissier et al., 2012). Taxadiene, particularly taxa-4(5),11(12)-diene, is the precursor of paclitaxel, a potent anticancer diterpene usually extracted from the bark of Taxus spp. (Hezari et al., 1995; Koepp et al., 1995). Several groups have already tried to synthesize this precursor ubiquitously in plants (for review, see Soliman and Tang, 2015), but the production of the diterpene triggered growth defects in tomato (Kovacs et al., 2007) and a lethal phenotype in Arabidopsis, most probably because of an overused geranylgeranyl diphosphate pool for diterpene synthesis (Besumbes et al., 2004). As a result, the MEP-derived primary metabolites were not synthesized in sufficient amounts to sustain normal growth. Only a few attempts led to the production of taxadiene in plants without any defect, as in ginseng (Panax ginseng; Cha et al., 2012) and N. benthamiana (Hasan et al., 2014) by the ubiquitous overexpression of the taxadiene synthase, but the amount produced was quite low.

Expression of taxadiene synthase specifically in N. tabacum trichomes, using the transcriptional promoter of cembratrienol synthase (CBTS), led to the production in the exudate of 5 to 10 µg g−1 fresh weight taxadiene, representing only 10% of the total taxadiene production, suggesting a problem of excretion (Tissier et al., 2012; discussed further in Box 3). However, the amount produced is impressive compared with the 27 µg g−1 dry weight obtained in the best stable transgenic N. benthamiana line (Hasan et al., 2014). Hasan et al. (2014) could increase the production in N. benthamiana up to 48 µg g−1 dry weight by, in addition to constitutively overexpressing the taxadiene synthase, silencing the expression of the gene coding for the phytoene synthase and thereby increasing the geranylgeranyl diphosphate availability. In N. tabacum, silencing the genes coding for CBTS did not increase the production of taxadiene (Tissier et al., 2012). Compared with the cultivated tobacco (N. tabacum), the wild tobacco (N. sylvestris) naturally synthesizes, as diterpenes, cembranoids but no labdanoids. Using the CBTS promoter to drive the expression of the 8-hydroxy-copalyl diphosphate synthase and the Z-abienol synthase specifically in N. sylvestris trichomes, synthesis of the labdanoid, Z-abienol, reached a yield of 30 µg g−1 fresh weight without any major impact on the production of cembranoids or on plant development (Sallaud et al., 2012). Similarly, casbene, another diterpene from Ricinus communis, also was produced in N. tabacum trichomes (Tissier et al., 2012), demonstrating that these structures can really be used as a biofactory for the production of a diverse set of diterpenes. While most of the cembrane and labdane diterpenes are normally found in the cuticle or in the exudate, only a small fraction (10%) of casbene or taxadiene was found in the exudate, suggesting the necessity of associating a transporter when engineering a metabolic pathway (Box 3).

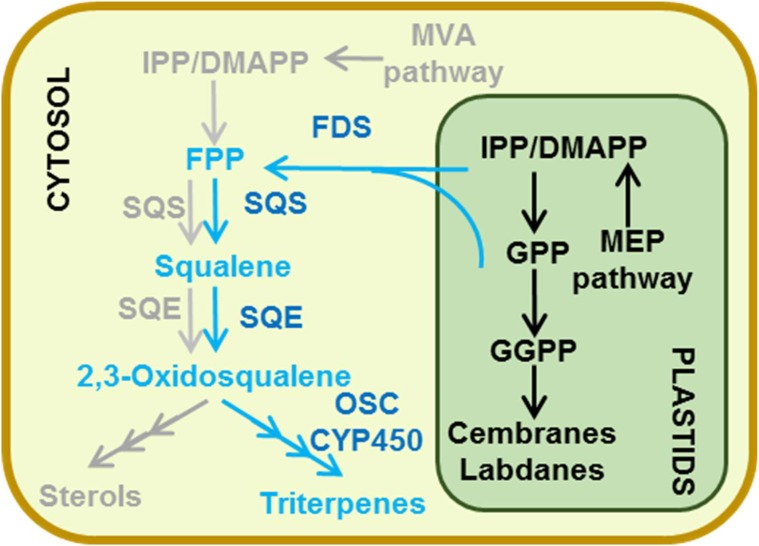

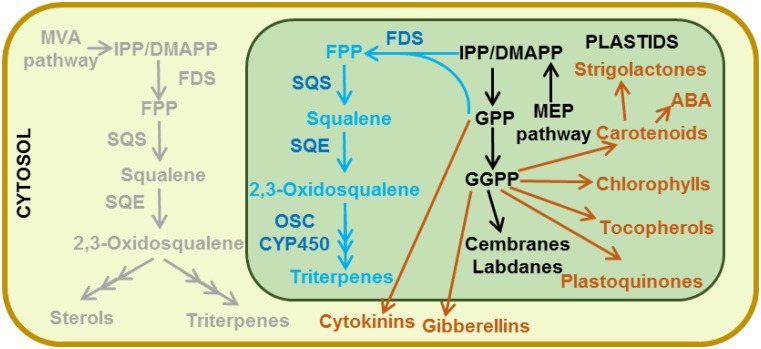

Triterpene Engineering

Could N. tabacum trichomes be used as a production platform for terpenoids other than diterpenes? In N. tabacum trichomes, the main isoprenoid-derived metabolites are diterpenes from the MEP pathway. Metabolic engineering in trichomes might take advantage of this cross talk to produce, for example, triterpenes instead of the naturally occurring diterpenes by diverting the plastidic pool of IPP toward the cytosol to produce the compounds of interest (Fig. 4). Some plants, such as S. habrochaites, produce some sesquiterpenes directly in the plastids. The corresponding enzymes, involved in the biosynthesis of those C15 terpenes, a sesquiterpene synthase and a farnesyl diphosphate synthase, evolved to be localized to the plastids (Sallaud et al., 2009). Engineering the production of MVA-derived metabolites such as sesquiterpenes (C15) or tritepernes (C30) in the plastids using specifically MEP-derived IPP and DMAPP precursors may require the corresponding enzymes (normally localized to the cytosol or to the endoplasmic reticulum) to be engineered to get targeted to the plastids (Fig. 5).

Figure 4.

Terpenoid metabolism in engineered tobacco trichomes for triterpene production in the cytosol. The gray pathway represents the normal biosynthetic route for triterpenes and sterols. The enzymes are targeted to the cytosol to enhance the cross talk and sink the plastids from its precursors. Overexpressed enzymes are denoted in dark blue. New products deriving from the engineering metabolism are denoted in light blue. CYP450, Cytochrome P450; FDS, farnesyl diphosphate synthase; FPP, farnesyl diphosphate; GGPP, geranylgeranyl diphosphate; GPP, geranyl diphosphate; OSC, 2,3-oxidosqualene cyclase; SQE, squalene epoxidase; SQS, squalene synthase.

Figure 5.

Terpenoid metabolism in engineered tobacco trichomes for triterpene production in plastids. The gray pathway represents the normal biosynthetic route for triterpenes and sterols. The enzymes are targeted to directly produce the triterpenes in the plastids. Overexpressed enzymes are denoted in dark blue. New products deriving from the engineering metabolism are denoted in light blue. The sinking plastidial isoprenoid pool might provoke undesirable consequences. Potentially affected metabolites are denoted in orange. ABA, Abscisic acid; CYP450, cytochrome P450; FDS, farnesyl diphosphate synthase; FPP, farnesyl diphosphate; GGPP, geranylgeranyl diphosphate; GPP, geranyl diphosphate; OSC, 2,3-oxidosqualene cyclase; SQE, squalene epoxidase; SQS, squalene synthase.

Triterpenes, the C30 family, are of particular interest for their substantial carbon content, making them good targets for biofuel production (Gübitz et al., 1999; Khan et al., 2014) as well as for pharmacological purposes. The biosynthesis of triterpenes requires several enzymatic steps (for review, see Phillips et al., 2006; Thimmappa et al., 2014). The production of squalene is the limiting regulatory step to produce triterpenes. Modifying the production and fate of squalene, a key precursor of phytosterols, is risky if this modification affects the whole plant, as it can lead to dwarfism and loss of fertility (for review, see Clouse, 2002; Schaller, 2003, 2004). Using the CBTS promoter, the production of squalene was achieved in N. tabacum trichomes (Wu et al., 2012). The production was greater when the two enzymes for squalene production, squalene synthase and farnesyl diphosphate synthase, were targeted to the chloroplast. Even though the expression of the transgenes was expected to be restricted to trichomes, those transgenic plants that expressed squalene at the highest level displayed strong phenotypes such as dwarfism and chlorosis, which are similar to the phenotypes observed upon ubiquist expression of transgenes impacting the pool of IPP precursors (Wu et al., 2006; Saxena et al., 2014; Gwak et al., 2017).

Using the same approach, the production of linear triterpenes typical of the green alga Botryococcus braunii was achieved in N. tabacum trichomes (Jiang et al., 2016). Once again, the best production rate was when the enzymes were targeted to the plastid, which suggests that the best strategy for triterpene production is to exploit the plastidial pool of IPP/DMAPP. However, as for squalene production (Wu et al., 2012), the synthesis of triterpenes led to chlorosis and dwarfism. Plastidial membranes are quite fragile, and the balance of sterols is important for the stability of the plastids (Babiychuk et al., 2008). Thus, the production of squalene or other triterpenes in the plastids might disrupt the chloroplast integrity and lead to chlorosis. Since trichomes are thought to be dispensable, the breakdown of chloroplasts is not expected to have major consequences on the whole plant. A possible explanation for this phenotype is that the promoter was not completely trichome specific, probably due to the presence of 35S enhancers upstream of the promoter (Wu et al., 2012; Jiang et al., 2016) or to some positional effects of the transgene affecting the specificity of the promoter. The cell type specificity of transgene(s) expression, therefore, should be strictly ascertained in transgenic lines and not based solely on the assessment of the cell type specificity of the promoter via the analysis of transcriptional reporter lines. Another plausible explanation for such a phenotype could be that, although trichomes are not essential, they may transmit a stress signal to other leaf tissues, leading to the observed phenotypes in the transgenic lines (Wu et al., 2012).

Metabolic engineering in tobacco has great potential. The amount of terpenoids that the plant can naturally produce is impressive. Using the plastidial pool for the production of terpenoids seems much more efficient than using the cytosolic one (Wu et al., 2006). However, ubiquist expression alters plant development and directly impairs the yield. To be economically viable, the yield of terpenoids should be increased with no or only a slight impact on the plant phenotype. Lack of excretion of the potentially cytotoxic metabolites is another issue (discussed in Box 3). In addition, comprehension of the exchange of prenyl diphosphates between the plastids and the cytosol (Box 2) also should be investigated so as to reroute the plastidic flux toward the cytosol and avoid disrupting the stability of the chloroplast with a change in sterol profile (Babiychuk et al., 2008).

CONCLUSION

At present, plant biologists are trying to go beyond the Arabidopsis model and to move to nonmodel plant species. In this respect, the study of glandular trichome biology is benefiting greatly from such a change of model system. Recent advances in DNA sequencing, omics technology, and reverse genetics, including plant genome editing, now offer new technical resources to investigate such biological aspects in a wide variety of species.

Our current understanding of both the development of glandular trichomes and of the biosynthetic pathways going on in these structures is improving, but at this point it is still quite fragmentary. However, an increasing number of research groups are now focusing on various aspects of glandular trichome biology, including developmental aspects and bioengineering.

Understanding the way glandular trichomes develop to finally turn into highly efficient biochemical factories in the epidermis of nonmodel plant species is of key importance and could lead to more applied outcomes. This calls for basic research to address these fascinating aspects. It is now time to consider the real biotechnological potential of glandular trichomes as biochemical factories and use up-to-date technology to fully exploit the cellular machinery. Increased knowledge of these fundamental aspects will, in the mid term, allow researchers to tap the up-to-now largely unexploited biotechnological potential of glandular trichomes to engineer plants that would exhibit increased resistance to pests or that would produce compounds of immense industrial/pharmaceutical interest (molecular pharming).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Antoine Champagne (Université Catholique de Louvain) for the scanning electron micrographs of N. tabacum glandular trichomes.

Glossary

- MEP

methylerythritol 4-phosphate

- JA

jasmonate

- MVA

mevalonate

Footnotes

This work was partly supported by the ERA-CAP HIP project, the Belgian National Fund for Scientific Research (MIS F.4522.17), and the Interuniversity Poles of Attraction Program (Belgian State, Scientific, Technical, and Cultural Services).

Articles can be viewed without a subscription.

References

- Adam KP, Thiel R, Zapp J (1999) Incorporation of 1-[1-13C]deoxy-D-xylulose in chamomile sesquiterpenes. Arch Biochem Biophys 369: 127–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adebesin F, Widhalm JR, Boachon B, Lefèvre F, Pierman B, Lynch JH, Alam I, Junqueira B, Benke R, Ray S, et al. (2017) Emission of volatile organic compounds from petunia flowers is facilitated by an ABC transporter. Science 356: 1386–1388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adrian J, Chang J, Ballenger CE, Bargmann BO, Alassimone J, Davies KA, Lau OS, Matos JL, Hachez C, Lanctot A, et al. (2015) Transcriptome dynamics of the stomatal lineage: birth, amplification, and termination of a self-renewing population. Dev Cell 33: 107–118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aharoni A, Jongsma MA, Bouwmeester HJ (2005) Volatile science? Metabolic engineering of terpenoids in plants. Trends Plant Sci 10: 594–602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar MQ, Qamar N, Yadav P, Kulkarni P, Kumar A, Shasany AK (2017) Comparative glandular trichome transcriptome-based gene characterization reveals reasons for differential (−)-menthol biosynthesis in Mentha species. Physiol Plant 160: 128–141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An L, Zhou Z, Yan A, Gan Y (2011) Progress on trichome development regulated by phytohormone signaling. Plant Signal Behav 6: 1959–1962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arigoni D, Sagner S, Latzel C, Eisenreich W, Bacher A, Zenk MH (1997) Terpenoid biosynthesis from 1-deoxy-D-xylulose in higher plants by intramolecular skeletal rearrangement. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 10600–10605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aschenbrenner AK, Amrehn E, Bechtel L, Spring O (2015) Trichome differentiation on leaf primordia of Helianthus annuus (Asteraceae): morphology, gene expression and metabolite profile. Planta 241: 837–846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babiychuk E, Bouvier-Navé P, Compagnon V, Suzuki M, Muranaka T, Van Montagu M, Kushnir S, Schaller H (2008) Allelic mutant series reveal distinct functions for Arabidopsis cycloartenol synthase 1 in cell viability and plastid biogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 3163–3168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Back K, Chappell J (1996) Identifying functional domains within terpene cyclases using a domain-swapping strategy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 6841–6845 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balcke GU, Bennewitz S, Bergau N, Athmer B, Henning A, Majovsky P, Jiménez-Gómez JM, Hoehenwarter W, Tissier A (2017) Multi-omics of tomato glandular trichomes reveals distinct features of central carbon metabolism supporting high productivity of specialized metabolites. Plant Cell 29: 960–983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balkunde R, Pesch M, Hülskamp M (2010) Trichome patterning in Arabidopsis thaliana from genetic to molecular models. Curr Top Dev Biol 91: 299–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartram S, Jux A, Gleixner G, Boland W (2006) Dynamic pathway allocation in early terpenoid biosynthesis of stress-induced lima bean leaves. Phytochemistry 67: 1661–1672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergau N, Bennewitz S, Syrowatka F, Hause G, Tissier A (2015) The development of type VI glandular trichomes in the cultivated tomato Solanum lycopersicum and a related wild species S. habrochaites. BMC Plant Biol 15: 289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergau N, Navarette Santos A, Henning A, Balcke GU, Tissier A (2016) Autofluorescence as a signal to sort developing glandular trichomes by flow cytometry. Front Plant Sci 7: 949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besumbes O, Sauret-Güeto S, Phillips MA, Imperial S, Rodríguez-Concepción M, Boronat A (2004) Metabolic engineering of isoprenoid biosynthesis in Arabidopsis for the production of taxadiene, the first committed precursor of taxol. Biotechnol Bioeng 88: 168–175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bick JA, Lange BM (2003) Metabolic cross talk between cytosolic and plastidial pathways of isoprenoid biosynthesis: unidirectional transport of intermediates across the chloroplast envelope membrane. Arch Biochem Biophys 415: 146–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleeker PM, Mirabella R, Diergaarde PJ, VanDoorn A, Tissier A, Kant MR, Prins M, de Vos M, Haring MA, Schuurink RC (2012) Improved herbivore resistance in cultivated tomato with the sesquiterpene biosynthetic pathway from a wild relative. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109: 20124–20129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger A, Scossa F, Bolger ME, Lanz C, Maumus F, Tohge T, Quesneville H, Alseekh S, Sørensen I, Lichtenstein G, et al. (2014) The genome of the stress-tolerant wild tomato species Solanum pennellii. Nat Genet 46: 1034–1038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bombo AB, Appezzato-da-Glória B, Aschenbrenner AK, Spring O (2016) Capitate glandular trichomes in Aldama discolor (Heliantheae-Asteraceae): morphology, metabolite profile and sesquiterpene biosynthesis. Plant Biol (Stuttg) 18: 455–462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosch M, Wright LP, Gershenzon J, Wasternack C, Hause B, Schaller A, Stintzi A (2014) Jasmonic acid and its precursor 12-oxophytodienoic acid control different aspects of constitutive and induced herbivore defenses in tomato. Plant Physiol 166: 396–410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bose SK, Yadav RK, Mishra S, Sangwan RS, Singh AK, Mishra B, Srivastava AK, Sangwan NS (2013) Effect of gibberellic acid and calliterpenone on plant growth attributes, trichomes, essential oil biosynthesis and pathway gene expression in differential manner in Mentha arvensis L. Plant Physiol Biochem 66: 150–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouvier F, Rahier A, Camara B (2005) Biogenesis, molecular regulation and function of plant isoprenoids. Prog Lipid Res 44: 357–429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cha M, Shim SH, Kim SH, Kim OT, Lee SW, Kwon SY, Baek KH (2012) Production of taxadiene from cultured ginseng roots transformed with taxadiene synthase gene. BMB Rep 45: 589–594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champagne A, Boutry M (2013) Proteomics of nonmodel plant species. Proteomics 13: 663–673 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang SY, Grunwald C (1976) Duvatrienediols in cuticular wax of Burley tobacco leaves. J Lipid Res 17: 7–11 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Liu M, Jiang L, Liu X, Zhao J, Yan S, Yang S, Ren H, Liu R, Zhang X (2014) Transcriptome profiling reveals roles of meristem regulators and polarity genes during fruit trichome development in cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.). J Exp Bot 65: 4943–4958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi YE, Lim S, Kim HJ, Han JY, Lee MH, Yang Y, Kim JA, Kim YS (2012) Tobacco NtLTP1, a glandular-specific lipid transfer protein, is required for lipid secretion from glandular trichomes. Plant J 70: 480–491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clouse SD. (2002) Arabidopsis mutants reveal multiple roles for sterols in plant development. Plant Cell 14: 1995–2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croteau R, Kutchan TM, Lewis NG (2000) Natural products (secondary metabolites). Biochem Mol Biol Plants 24: 1250–1319 [Google Scholar]

- Cui JY, Miao H, Ding LH, Wehner TC, Liu PN, Wang Y, Zhang SP, Gu XF (2016) A new glabrous gene (csgl3) identified in trichome development in cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.). PLoS ONE 11: e0148422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai X, Wang G, Yang DS, Tang Y, Broun P, Marks MD, Sumner LW, Dixon RA, Zhao PX (2010) TrichOME: a comparative omics database for plant trichomes. Plant Physiol 152: 44–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deschamps C, Gang D, Dudareva N, Simon JE (2006) Developmental regulation of phenylpropanoid biosynthesis in leaves and glandular trichomes of basil (Ocimum basilicum L.). Int J Plant Sci 167: 447–454 [Google Scholar]

- Dixon RA. (2005) Engineering of plant natural product pathways. Curr Opin Plant Biol 8: 329–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dokládal L, Obořil M, Stejskal K, Zdráhal Z, Ptácková N, Chaloupková R, Damborský J, Kašparovský T, Jeandroz S, Zd’árská M, et al. (2012) Physiological and proteomic approaches to evaluate the role of sterol binding in elicitin-induced resistance. J Exp Bot 63: 2203–2215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudareva N, Andersson S, Orlova I, Gatto N, Reichelt M, Rhodes D, Boland W, Gershenzon J (2005) The nonmevalonate pathway supports both monoterpene and sesquiterpene formation in snapdragon flowers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 933–938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards KD, Fernandez-Pozo N, Drake-Stowe K, Humphry M, Evans AD, Bombarely A, Allen F, Hurst R, White B, Kernodle SP, et al. (2017) A reference genome for Nicotiana tabacum enables map-based cloning of homeologous loci implicated in nitrogen utilization efficiency. BMC Genomics 18: 448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliger CA, Benson ME, Haddon WF, Lundin RE, Waiss AC, Wong RY (1988) Petuniasterones, novel ergostane-type steroids of Petunia hybridia Vilm. (Solanaceae) having insect-inhibitory activity: x-ray molecular structure of the 22,24,25-[(methoxycarbonyl)orthoacetate] of 7[α],22,24,25-tetrahydroxy ergosta-1,4-dien-3-one and of 1[α]-acetoxy-24,25-epoxy-7[α]-hydroxy-22-(methylthiocarbonyl)acetoxyergost-4-en-3-one. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans 1 711–717 [Google Scholar]

- Elliger CA, Wong RY, Waiss AC, Benson M (1990) Petuniolides: unusual ergostanoid lactones from Petunia species that inhibit insect development. J Chem Soc Perkin Trans 1 525–531 [Google Scholar]

- Ennajdaoui H, Vachon G, Giacalone C, Besse I, Sallaud C, Herzog M, Tissier A (2010) Trichome specific expression of the tobacco (Nicotiana sylvestris) cembratrien-ol synthase genes is controlled by both activating and repressing cis-regions. Plant Mol Biol 73: 673–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahn A. (2000) Structure and function of secretory cells. In Hallahan DL, Gray JC, Callow JA, eds, Plant Trichomes. Advances in Botanical Research Incorporating Advances in Plant Pathology, Vol 31 Academic Press, London [Google Scholar]

- Farhi M, Marhevka E, Ben-Ari J, Algamas-Dimantov A, Liang Z, Zeevi V, Edelbaum O, Spitzer-Rimon B, Abeliovich H, Schwartz B, et al. (2011) Generation of the potent anti-malarial drug artemisinin in tobacco. Nat Biotechnol 29: 1072–1074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flügge UI, Gao W (2005) Transport of isoprenoid intermediates across chloroplast envelope membranes. Plant Biol (Stuttg) 7: 91–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fridman E, Wang J, Iijima Y, Froehlich JE, Gang DR, Ohlrogge J, Pichersky E (2005) Metabolic, genomic, and biochemical analyses of glandular trichomes from the wild tomato species Lycopersicon hirsutum identify a key enzyme in the biosynthesis of methylketones. Plant Cell 17: 1252–1267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu X, Shi P, He Q, Shen Q, Tang Y, Pan Q, Ma Y, Yan T, Chen M, Hao X, et al. (2017) AaPDR3, a PDR transporter 3, is involved in sesquiterpene β-caryophyllene transport in Artemisia annua. Front Plant Sci 8: 723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gang DR, Wang J, Dudareva N, Nam KH, Simon JE, Lewinsohn E, Pichersky E (2001) An investigation of the storage and biosynthesis of phenylpropenes in sweet basil. Plant Physiol 125: 539–555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber E, Hemmerlin A, Hartmann M, Heintz D, Hartmann MA, Mutterer J, Rodríguez-Concepción M, Boronat A, Van Dorsselaer A, Rohmer M, et al. (2009) The plastidial 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol 4-phosphate pathway provides the isoprenyl moiety for protein geranylgeranylation in tobacco BY-2 cells. Plant Cell 21: 285–300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershenzon J, Dudareva N (2007) The function of terpene natural products in the natural world. Nat Chem Biol 3: 408–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gershenzon J, McCaskill D, Rajaonarivony JI, Mihaliak C, Karp F, Croteau R (1992) Isolation of secretory cells from plant glandular trichomes and their use in biosynthetic studies of monoterpenes and other gland products. Anal Biochem 200: 130–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glas JJ, Schimmel BC, Alba JM, Escobar-Bravo R, Schuurink RC, Kant MR (2012) Plant glandular trichomes as targets for breeding or engineering of resistance to herbivores. Int J Mol Sci 13: 17077–17103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glover BJ, Perez-Rodriguez M, Martin C (1998) Development of several epidermal cell types can be specified by the same MYB-related plant transcription factor. Development 125: 3497–3508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gübitz GM, Mittelbach M, Trabi M (1999) Exploitation of the tropical oil seed plant Jatropha curcas L. Bioresour Technol 67: 73–82 [Google Scholar]

- Guo Z, Wagner GJ (1995) Biosynthesis of labdenediol and sclareol in cell-free extracts from trichomes of Nicotiana glutinosa. Planta 197: 627–632 [Google Scholar]

- Gutensohn M, Nguyen TT, McMahon RD III, Kaplan I, Pichersky E, Dudareva N (2014) Metabolic engineering of monoterpene biosynthesis in tomato fruits via introduction of the non-canonical substrate neryl diphosphate. Metab Eng 24: 107–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez-Alcalá G, Calo L, Gros F, Caissard JC, Gotor C, Romero LC (2005) A versatile promoter for the expression of proteins in glandular and non-glandular trichomes from a variety of plants. J Exp Bot 56: 2487–2494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gwak YS, Han JY, Adhikari PB, Ahn CH, Choi YE (2017) Heterologous production of a ginsenoside saponin (compound K) and its precursors in transgenic tobacco impairs the vegetative and reproductive growth. Planta (in press) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hampel D, Swatski A, Mosandl A, Wüst M (2007) Biosynthesis of monoterpenes and norisoprenoids in raspberry fruits (Rubus idaeus L.): the role of cytosolic mevalonate and plastidial methylerythritol phosphate pathway. J Agric Food Chem 55: 9296–9304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasan MM, Kim HS, Jeon JH, Kim SH, Moon B, Song JY, Shim SH, Baek KH (2014) Metabolic engineering of Nicotiana benthamiana for the increased production of taxadiene. Plant Cell Rep 33: 895–904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmerlin A, Harwood JL, Bach TJ (2012) A raison d’être for two distinct pathways in the early steps of plant isoprenoid biosynthesis? Prog Lipid Res 51: 95–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmerlin A, Hoeffler JF, Meyer O, Tritsch D, Kagan IA, Grosdemange-Billiard C, Rohmer M, Bach TJ (2003) Cross-talk between the cytosolic mevalonate and the plastidial methylerythritol phosphate pathways in tobacco Bright Yellow-2 cells. J Biol Chem 278: 26666–26676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hezari M, Lewis NG, Croteau R (1995) Purification and characterization of taxa-4(5),11(12)-diene synthase from Pacific yew (Taxus brevifolia) that catalyzes the first committed step of taxol biosynthesis. Arch Biochem Biophys 322: 437–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S, Li R, Zhang Z, Li L, Gu X, Fan W, Lucas WJ, Wang X, Xie B, Ni P, et al. (2009) The genome of the cucumber, Cucumis sativus L. Nat Genet 41: 1275–1281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huchelmann A, Brahim MS, Gerber E, Tritsch D, Bach TJ, Hemmerlin A (2016) Farnesol-mediated shift in the metabolic origin of prenyl groups used for protein prenylation in plants. Biochimie 127: 95–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huchelmann A, Gastaldo C, Veinante M, Zeng Y, Heintz D, Tritsch D, Schaller H, Rohmer M, Bach TJ, Hemmerlin A (2014) S-Carvone suppresses cellulase-induced capsidiol production in Nicotiana tabacum by interfering with protein isoprenylation. Plant Physiol 164: 935–950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh D, Kawano K, Nabeta K (2003) Biosynthesis of chloroplastidic and extrachloroplastidic terpenoids in liverwort cultured cells: 13C serine as a probe of terpene biosynthesis via mevalonate and non-mevalonate pathways. J Nat Prod 66: 332–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffé FW, Tattersall A, Glover BJ (2007) A truncated MYB transcription factor from Antirrhinum majus regulates epidermal cell outgrowth. J Exp Bot 58: 1515–1524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Z, Kempinski C, Bush CJ, Nybo SE, Chappell J (2016) Engineering triterpene and methylated triterpene production in plants provides biochemical and physiological insights into terpene metabolism. Plant Physiol 170: 702–716 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin J, Panicker D, Wang Q, Kim MJ, Liu J, Yin JL, Wong L, Jang IC, Chua NH, Sarojam R (2014) Next generation sequencing unravels the biosynthetic ability of spearmint (Mentha spicata) peltate glandular trichomes through comparative transcriptomics. BMC Plant Biol 14: 292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jozwiak A, Lipko A, Kania M, Danikiewicz W, Surmacz L, Witek A, Wojcik J, Zdanowski K, Pączkowski C, Chojnacki T, et al. (2017) Modeling of dolichol mass spectra isotopic envelopes as a tool to monitor isoprenoid biosynthesis. Plant Physiol 174: 857–874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandra L, Wagner GJ (1988) Studies of the site and mode of biosynthesis of tobacco trichome exudate components. Arch Biochem Biophys 265: 425–432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang JH, Campos ML, Zemelis-Durfee S, Al-Haddad JM, Jones AD, Telewski FW, Brandizzi F, Howe GA (2016) Molecular cloning of the tomato Hairless gene implicates actin dynamics in trichome-mediated defense and mechanical properties of stem tissue. J Exp Bot 67: 5313–5324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang JH, Liu G, Shi F, Jones AD, Beaudry RM, Howe GA (2010) The tomato odorless-2 mutant is defective in trichome-based production of diverse specialized metabolites and broad-spectrum resistance to insect herbivores. Plant Physiol 154: 262–272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang JH, McRoberts J, Shi F, Moreno JE, Jones AD, Howe GA (2014) The flavonoid biosynthetic enzyme chalcone isomerase modulates terpenoid production in glandular trichomes of tomato. Plant Physiol 164: 1161–1174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsir L, Schilmiller AL, Staswick PE, He SY, Howe GA (2008) COI1 is a critical component of a receptor for jasmonate and the bacterial virulence factor coronatine. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 7100–7105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keasling JD. (2010) Manufacturing molecules through metabolic engineering. Science 330: 1355–1358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keene CK, Wagner GJ (1985) Direct demonstration of duvatrienediol biosynthesis in glandular heads of tobacco trichomes. Plant Physiol 79: 1026–1032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan NE, Myers JA, Tuerk AL, Curtis WR (2014) A process economic assessment of hydrocarbon biofuels production using chemoautotrophic organisms. Bioresour Technol 172: 201–211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Park M, Yeom SI, Kim YM, Lee JM, Lee HA, Seo E, Choi J, Cheong K, Kim KT, et al. (2014) Genome sequence of the hot pepper provides insights into the evolution of pungency in Capsicum species. Nat Genet 46: 270–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SH, Chang YJ, Kim SU (2008) Tissue specificity and developmental pattern of amorpha-4,11-diene synthase (ADS) proved by ADS promoter-driven GUS expression in the heterologous plant, Arabidopsis thaliana. Planta Med 74: 188–193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby J, Keasling JD (2009) Biosynthesis of plant isoprenoids: perspectives for microbial engineering. Annu Rev Plant Biol 60: 335–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koepp AE, Hezari M, Zajicek J, Vogel BS, LaFever RE, Lewis NG, Croteau R (1995) Cyclization of geranylgeranyl diphosphate to taxa-4(5),11(12)-diene is the committed step of taxol biosynthesis in Pacific yew. J Biol Chem 270: 8686–8690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koo AJK, Howe GA (2009) The wound hormone jasmonate. Phytochemistry 70: 1571–1580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kortbeek RW, Xu J, Ramirez A, Spyropoulou E, Diergaarde P, Otten-Bruggeman I, de Both M, Nagel R, Schmidt A, Schuurink RC, et al. (2016) Engineering of tomato glandular trichomes for the production of specialized metabolites. Methods Enzymol 576: 305–331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs K, Zhang L, Linforth RS, Whittaker B, Hayes CJ, Fray RG (2007) Redirection of carotenoid metabolism for the efficient production of taxadiene [taxa-4(5),11(12)-diene] in transgenic tomato fruit. Transgenic Res 16: 121–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroumova AB, Wagner GJ (2003) Different elongation pathways in the biosynthesis of acyl groups of trichome exudate sugar esters from various solanaceous plants. Planta 216: 1013–1021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange BM, Ahkami A (2013) Metabolic engineering of plant monoterpenes, sesquiterpenes and diterpenes: current status and future opportunities. Plant Biotechnol J 11: 169–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange BM, Mahmoud SS, Wildung MR, Turner GW, Davis EM, Lange I, Baker RC, Boydston RA, Croteau RB (2011) Improving peppermint essential oil yield and composition by metabolic engineering. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 16944–16949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange BM, Turner GW (2013) Terpenoid biosynthesis in trichomes: current status and future opportunities. Plant Biotechnol J 11: 2–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laterre R, Pottier M, Remacle C, Boutry M (2017) Photosynthetic trichomes contain a specific Rubisco with a modified pH-dependent activity. Plant Physiol 173: 2110–2120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Zhao Y, McCaig BC, Wingerd BA, Wang J, Whalon ME, Pichersky E, Howe GA (2004) The tomato homolog of CORONATINE-INSENSITIVE1 is required for the maternal control of seed maturation, jasmonate-signaled defense responses, and glandular trichome development. Plant Cell 16: 126–143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Cao C, Zhang C, Zheng S, Wang Z, Wang L, Ren Z (2015) The identification of Cucumis sativus Glabrous 1 (CsGL1) required for the formation of trichomes uncovers a novel function for the homeodomain-leucine zipper I gene. J Exp Bot 66: 2515–2526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liakopoulos G, Stavrianakou S, Karabourniotis G (2006) Trichome layers versus dehaired lamina of Olea europaea leaves: differences in flavonoid distribution, UV-absorbing capacity, and wax yield. Environ Exp Bot 55: 294–304 [Google Scholar]

- Lipko A, Swiezewska E (2016) Isoprenoid generating systems in plants—A handy toolbox how to assess contribution of the mevalonate and methylerythritol phosphate pathways to the biosynthetic process. Progress in lipid research 63: 70–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Xia KF, Zhu JC, Deng YG, Huang XL, Hu BL, Xu X, Xu ZF (2006) The nightshade proteinase inhibitor IIb gene is constitutively expressed in glandular trichomes. Plant Cell Physiol 47: 1274–1284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Bartholomew E, Cai Y, Ren H (2016) Trichome-related mutants provide a new perspective on multicellular trichome initiation and development in cucumber (Cucumis sativus L). Front Plant Sci 7: 1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Liu D, Hu R, Hua C, Ali I, Zhang A, Liu B, Wu M, Huang L, Gan Y (2017) AtGIS, a C2H2 zinc-finger transcription factor from Arabidopsis regulates glandular trichome development through GA signaling in tobacco. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 483: 209–215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lücker J, Schwab W, Franssen MCR, Van Der Plas LHW, Bouwmeester HJ, Verhoeven HA (2004) Metabolic engineering of monoterpene biosynthesis: two-step production of (+)-trans-isopiperitenol by tobacco. Plant J 39: 135–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luu VT, Weinhold A, Ullah C, Dressel S, Schoettner M, Gase K, Gaquerel E, Xu S, Baldwin IT (2017) O-Acyl sugars protect a wild tobacco from both native fungal pathogens and a specialist herbivore. Plant Physiol 174: 370–386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma D, Hu Y, Yang C, Liu B, Fang L, Wan Q, Liang W, Mei G, Wang L, Wang H, et al. (2016) Genetic basis for glandular trichome formation in cotton. Nat Commun 7: 10456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maluf WR, Barbosa LV, Costa Santa-Cecília LV (1997) 2-Tridecanone-mediated mechanisms of resistance to the South American tomato pinworm Scrobipalpuloides absoluta (Meyrick, 1917) (Lepidoptera-Gelechiidae) in Lycopersicon spp. Euphytica 93: 189–194 [Google Scholar]

- Marienhagen J, Bott M (2013) Metabolic engineering of microorganisms for the synthesis of plant natural products. J Biotechnol 163: 166–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matías-Hernández L, Aguilar-Jaramillo AE, Cigliano RA, Sanseverino W, Pelaz S (2016) Flowering and trichome development share hormonal and transcription factor regulation. J Exp Bot 67: 1209–1219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matías-Hernández L, Jiang W, Yang K, Tang K, Brodelius PE, Pelaz S (2017) AaMYB1 and its orthologue AtMYB61 affect terpene metabolism and trichome development in Artemisia annua and Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 90: 520–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesmin B, Antonny B (2016) The counterflow transport of sterols and PI4P. Biochim Biophys Acta 1861: 940–951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moses T, Pollier J, Thevelein JM, Goossens A (2013) Bioengineering of plant (tri)terpenoids: from metabolic engineering of plants to synthetic biology in vivo and in vitro. New Phytol 200: 27–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muravnik LE, Kostina OV, Shavarda AL (2016) Glandular trichomes of Tussilago farfara (Senecioneae, Asteraceae). Planta 244: 737–752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakashima T, Wada H, Morita S, Erra-Balsells R, Hiraoka K, Nonami H (2016) Single-cell metabolite profiling of stalk and glandular cells of intact trichomes with internal electrode capillary pressure probe electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Anal Chem 88: 3049–3057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natsume S, Takagi H, Shiraishi A, Murata J, Toyonaga H, Patzak J, Takagi M, Yaegashi H, Uemura A, Mitsuoka C, et al. (2015) The draft genome of hop (Humulus lupulus), an essence for brewing. Plant Cell Physiol 56: 428–441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada Y, Ito K (2001) Cloning and analysis of valerophenone synthase gene expressed specifically in lupulin gland of hop (Humulus lupulus L.). Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 65: 150–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paetzold H, Garms S, Bartram S, Wieczorek J, Urós-Gracia EM, Rodríguez-Concepción M, Boland W, Strack D, Hause B, Walter MH (2010) The isogene 1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate synthase 2 controls isoprenoid profiles, precursor pathway allocation, and density of tomato trichomes. Mol Plant 3: 904–916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Y, Bo K, Cheng Z, Weng Y (2015) The loss-of-function GLABROUS 3 mutation in cucumber is due to LTR-retrotransposon insertion in a class IV HD-ZIP transcription factor gene CsGL3 that is epistatic over CsGL1. BMC Plant Biol 15: 302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattanaik S, Patra B, Singh SK, Yuan L (2014) An overview of the gene regulatory network controlling trichome development in the model plant, Arabidopsis. Front Plant Sci 5: 259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Payne T, Clement J, Arnold D, Lloyd A (1999) Heterologous myb genes distinct from GL1 enhance trichome production when overexpressed in Nicotiana tabacum. Development 126: 671–682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips DR, Rasbery JM, Bartel B, Matsuda SP (2006) Biosynthetic diversity in plant triterpene cyclization. Curr Opin Plant Biol 9: 305–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puterka GJ, Farone W, Palmer T, Barrington A (2003) Structure-function relationships affecting the insecticidal and miticidal activity of sugar esters. J Econ Entomol 96: 636–644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi T, Huang H, Wu D, Yan J, Qi Y, Song S, Xie D (2014) Arabidopsis DELLA and JAZ proteins bind the WD-repeat/bHLH/MYB complex to modulate gibberellin and jasmonate signaling synergy. Plant Cell 26: 1118–1133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ralston L, Kwon ST, Schoenbeck M, Ralston J, Schenk DJ, Coates RM, Chappell J (2001) Cloning, heterologous expression, and functional characterization of 5-epi-aristolochene-1,3-dihydroxylase from tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum). Arch Biochem Biophys 393: 222–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohmer M. (2003) Mevalonate-independent methylerythritol phosphate pathway for isoprenoid biosynthesis: elucidation and distribution. Pure Appl Chem 75: 375–388 [Google Scholar]

- Rontein D, Onillon S, Herbette G, Lesot A, Werck-Reichhart D, Sallaud C, Tissier A (2008) CYP725A4 from yew catalyzes complex structural rearrangement of taxa-4(5),11(12)-diene into the cyclic ether 5(12)-oxa-3(11)-cyclotaxane. J Biol Chem 283: 6067–6075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallaud C, Giacalone C, Töpfer R, Goepfert S, Bakaher N, Rösti S, Tissier A (2012) Characterization of two genes for the biosynthesis of the labdane diterpene Z-abienol in tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) glandular trichomes. Plant J 72: 1–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallaud C, Rontein D, Onillon S, Jabès F, Duffé P, Giacalone C, Thoraval S, Escoffier C, Herbette G, Leonhardt N, et al. (2009) A novel pathway for sesquiterpene biosynthesis from Z,Z-farnesyl pyrophosphate in the wild tomato Solanum habrochaites. Plant Cell 21: 301–317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasse J, Schlegel M, Borghi L, Ullrich F, Lee M, Liu GW, Giner JL, Kayser O, Bigler L, Martinoia E, et al. (2016) Petunia hybrida PDR2 is involved in herbivore defense by controlling steroidal contents in trichomes. Plant Cell Environ 39: 2725–2739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]