Abstract

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) suffer from low sensitivity and limited nuclear spin memory lifetimes. Although hyperpolarization techniques increase sensitivity, there is also a desire to increase relaxation times to expand the range of applications addressable by these methods. Here, we demonstrate a route to create hyperpolarized magnetization in 13C nuclear spin pairs that last much longer than normal lifetimes by storage in a singlet state. By combining molecular design and low‐field storage with para‐hydrogen derived hyperpolarization, we achieve more than three orders of signal amplification relative to equilibrium Zeeman polarization and an order of magnitude extension in state lifetime. These studies use a range of specifically synthesized pyridazine derivatives and dimethyl p‐tolyl phenyl pyridazine is the most successful, achieving a lifetime of about 190 s in low‐field, which leads to a 13C‐signal that is visible for 10 minutes.

Keywords: hyperpolarization, long-lived singlet states, NMR spectroscopy, para-hydrogen, structure elucidation

Although carbon is one of the most abundant elements in nature, its NMR‐active form carbon‐13 is present at only about a 1.1 % level which, when coupled with its low magnetogyric ratio, results in low detectability. Consequently, 13C magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) produces a negligible response when compared to proton measurement in the body, which is facile due to high water content and high sensitivity. 13C detection does, however, benefit from potentially long relaxation times when compared to those of the proton.

A number of methods, commonly known as hyperpolarization, exist that can increase NMR sensitivity in nuclei such as 13C and are being used to overcome these issues.1, 2 These approaches artificially increase the associated spin population differences between the energy levels that are probed. For example, Golman et al. reported a para‐hydrogen (p‐H2) induced nuclear polarization (PHIP) study,3, 4 which achieved the rapid in vivo detection of a 13C‐MRI response in 2001.5 Two years later, they described the results of a similar study using dissolution dynamic nuclear polarization (DNP),6 in which a normally inaccessible response was seen in vivo. Bhattacharya et al. have since incorporated p‐H2 into sodium 1–13C acetylene dicarboxylate to facilitate the collection of an arterial 13C‐MRI image of a rat brain.7 More recently, a DNP‐derived 13C‐MRI response with chemical shift resolution has been shown to distinguish different metabolic flux between normal and tumor cells in humans.8, 9, 10, 11 These studies illustrate the potential benefits to human health if such methods were to become widely accessible and hence establish the need for a rapid and low‐cost delivery method for long‐lived 13C hyperpolarization.

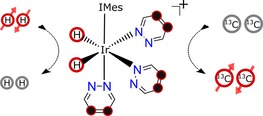

In this article, we demonstrate that the goal of rapidly producing a long‐lived 13C hyperpolarized response can be met by applying the signal amplification by reversible exchange (SABRE) effect.12, 13, 14 In SABRE, a catalyst reversibly binds p‐H2 and the substrate to transfer dormant spin order from p‐H2 into the substrate through the scalar‐coupling framework, as shown in Scheme 1. We use this approach here to hyperpolarize a series of coupled 13C spin‐pairs in a range of pyridazine derivatives, a motif that exhibits pharmacological activity.15, 16 Polarization is then stored in specially created singlet spin order to enable a response to be seen several minutes later. Although a range of nicotinamide‐ and pyridazine‐based substrates have been shown to deliver long‐lived 1H hyperpolarization,17, 18 and analogous 15N‐based singlets have been created by Warren and co‐workers,19 we believe the 13C responses reported here are significant due to the growing use of 13C‐MRI for in vivo study.

Scheme 1.

Schematic depiction of the SABRE hyperpolarization technique. IMes=1,3‐bis(2,4,6‐trimethylphenyl)imidazol‐2‐ylidene.

The term singlet (|S 0⟩=(|αβ⟩−|βα⟩)√2) that is used here represents the spin‐zero magnetic alignment of a coupled spin‐1/2 system, the conversion of which into the associated triplet states (|T 0⟩=(|αβ⟩+|βα⟩)√2; |T 1⟩=|αα⟩; |T −1⟩=|ββ⟩) is symmetry‐forbidden. Consequently, any population difference that can be created between these singlet and triplet forms is expected to relax more slowly than the usual time constant T 1.20 The symmetry properties that make such states long‐lived also make them challenging to generate and probe.20, 21 Levitt and co‐workers have demonstrated a number of strategies to do this in a range of chemically inequivalent spin systems22, 23, 24, 25, 26 and have achieved a lifetime of over one hour in an optimized chemical system at low field.27 However, when a substantial chemical shift difference exists between these spin‐pairs, the application of a spin‐lock, or sample‐shuttling to low field, is necessary to extend state lifetime.22, 28, 29 This effect has recently been illustrated by monitoring the effect of solvent‐dependent chemical‐shift changes.17, 18 Warren and co‐workers have reported a parallel approach that exploits magnetic inequivalence to create related singlet states.21, 30, 31, 32, 33 Thus, whereas SABRE has been shown to create hyperpolarized 1H‐ and 15N‐derived singlets, there is a need to expand these methods to 13C given the success of DNP.8, 9, 10, 11 However, 13C‐SABRE itself has currently seen limited application34 and reported efficiency gains are relatively low. We have now developed a molecular design strategy for use with SABRE and radio frequency (rf) excitation to achieve greater than 2 % net 13C polarization in a long‐lived form.

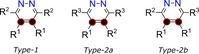

In this study, we employ magnetic and chemical inequivalence effects through the synthesis of specific substrates in which their carbon‐4 and carbon‐5 sites are 13C‐enriched, as detailed in Scheme 2 (full synthetic strategy and characterization data are available in the Supporting Information, Section S1–3). The Type‐1 form agents exhibit chemically equivalent but magnetically inequivalent 13C spin‐pairs (▵δ=0) and have local C 2 symmetry. The Type‐2a form is constructed such that R1 and R2 are chemically different and a small chemical‐shift difference results between the 13C spin‐pair (▵δ≠0). Chemical inequivalence is also derived by remote substitution at R2 and R3, in the Type‐2b agents of Scheme 2. Although these synthetic strategies allow access to two distinct classes of molecular system, our results illustrate that both are equally viable.

Scheme 2.

The molecular systems studied here are of Type‐1, which reflect a chemically equivalent but magnetically distinct 13C spin‐pair (black and red dots), or Type‐2a and Type‐2b, which reflect chemically inequivalent 13C spin‐pairs (R1≠R2≠R3).

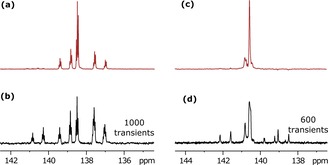

To explore the singlet states of these systems, their NMR properties must first be analyzed. The Type‐1 substrate, 1, of Table 1 reflects an AA′XX′‐type spin system (Figure 1 a) and produces the 13C NMR spectrum shown in Figure 1 b. This trace illustrates the effect of magnetic inequivalence, but does not immediately yield the individual carbon–proton couplings (2 J CH and 3 J CH) necessary to create a singlet state by the method of Warren,21 because the peak‐to‐peak separations reflect the mean value of the 13C‐1H J‐couplings (5.25 Hz=[2 J CH+3 J CH]/2). By employing a J‐synchronized experiment,23, 30, 32 it is possible to show that the difference in these J‐couplings is 3.1 Hz (see Section S5 in the Supporting Information). We harness this difference in coupling (ΔJ CH) to populate the singlet state through rf pulse‐sequencing, as detailed in Figure 1 c. Table 1 details the chemical structures of Type‐1 agents 1–3 that are examined here. A value of zero for ΔJ CH means that it is not possible to induce interconversion between the singlet and triplets forms through rf pulsing (e.g., agent 3, see Section S5).20

Table 1.

13C (red/white dots) SABRE signal enhancement (ϵ) over the corresponding thermal measurement at 9.4 T after transfer at the indicated field (G), net polarization (P) and T 1 and T S lifetimes (s) of substrate 1–8 in high field (HF: 9.4 T) and low field (LF: ≈10 mT). The J‐coupling between the 13C spin‐pair was found to be about 58.5±2.0 Hz in all cases. The ΔJ CH values for Type‐1 substrates, and the chemical shift difference (Δv) for Type‐2 substrates are noted.

| Agent | Substrate structure | Enhancement (ϵ), transfer field, net polarization level P [%] | Lifetime [s] | ΔJ CH* or Δv@9.4 T [Hz] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

ϵ: 2500±300 @30 G P≈2.0 | T 1: 9.7±0.3 T S(HF): 75±5.5 T S(LF): 115±12 | 3.1±0.2* |

| 2 |

|

ϵ: 1600±280 @150 G P≈1.3 | T 1: 12.4±0.9 T S(HF/LF): – | 2 J CD≈0.4* |

| 3 |

|

ϵ: 600±50 @20 mG P≈0.5 | T 1: 16.0±1.5 T S(HF/LF): No access | 0 |

| 4 |

|

ϵ: 1600±300 @150 G P≈1.3 | T 1: 10.2±0.6 T S(HF): 22±3.0 T S(LF): 28±6.5 | 11.0±0.1 |

| 5 |

|

ϵ: 550±50 @5 mG P≈0.45 | T 1: 15.5±1.2 T S(HF): 90±3.0 T S(LF): 165±18 | 10.4±0.1 |

| 6 |

|

ϵ: 350±40 @10 mG P≈0.35 | T 1: 10.4±0.3 T S(HF): 115±5.5 T S(LF): 148±20 | 14.5±0.4 |

| 7 |

|

ϵ: 600±50 @1 mG P≈0.50 | T 1: 15.2±0.3 T S(HF): 145±6.0 T S(LF): 186±18 | 4.4±0.3 |

| 8 |

|

ϵ: 800±150 @10 mG P≈0.65 | T 1: 7.5±0.5 T S(HF): <5 T S(LF): 45±6.0 | 78.8±0.5 |

Figure 1.

(a) Spin topology of the Type‐1 agent 1, showing the J‐couplings that exist between the 1H and 13C nuclei, in which R1=deuterated phenyl group; (b) corresponding 13C NMR spectrum of agent 1 in [D4]MeOH; (c) M2S‐S2M pulse sequence used here; (d) spin topology of Type‐2 substrate 5 and corresponding 13C NMR spectrum in [D4]MeOH (e).

We also prepared agents 4–8, which reflect a series of Type‐2 molecular systems. Their spin system is illustrated in Figure 1 d, whereas Figure 1 e shows the 13C NMR spectrum of agent 5 in [D4]MeOH. In this case, the partially resolved 1.05 Hz (▵δ 2 ν 2/2J CC) splitting signifies that a strongly coupled 13C spin‐pair results when R1 and R2 are deuterated phenyl and para‐tolyl groups, respectively.

The pulse sequence that is used to create and examine the lifetime of the singlet state in these Type‐1 and ‐2 molecules consists of three parts, as detailed in Figure 1 c. Part I converts longitudinal magnetization into singlet order (M2S), part II preserves this singlet order, and part III converts it back into a visible form. The first and last steps are realized experimentally by a train of n 180° pulses that are separated by delay (τ), which is a molecule‐specific parameter. For the Type‐1 system, 1 in which J CC≫J HH, Equations (1)–(3) provide τ and n.30, 32

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

In contrast, in the case of the Type‐2 spin systems (agents 4–8), these parameters come from Equations (3)–(5) shown above and below.

| (4) |

| (5) |

Section S7 in the Supporting Information details these values for 1–8. The resulting singlet states were then stored either in high field or in low field (after sample transfer). For 1, the singlet state lifetimes (T S) were measured to be 75±5.5 and 115±12 s at high and low field, respectively. We therefore see about a 10‐fold increase over the 9.4 T T 1 relaxation time of 9.7 s. The effect of a spin‐lock during high‐field storage proved to be minimal, increasing the T S by only about 10 %. In the case of agent 5, we achieved a T S of 90±3 s in high field, which increases to 165±18 s in low‐field. Table 1 summarizes these values for agents 1–8 and confirms that this strategy allows the creation of long‐lived singlet states in these molecules. 2H‐labeled 7 contained the optimal molecular environment of the series, delivering a low‐field T S of 186±18 s.

For 2, the 13C‐2H couplings are too small to exploit the M2S sequence to prepare the singlet. For 4, the singlet‐state lifetime proved low due to the 13C‐deuterium coupling, which provides a route to scalar relaxation.35 In 8, the chemical shift difference between the 13C pairs is similar to the J‐coupling constant in high field and a low lifetime results but in low field this extends to 45 s. In contrast, agents 5, 6 and 7 operate well in both low and high field, exhibiting lifetimes in excess of 150 s in low field.

A series of SABRE experiments were then undertaken to see if it was possible to create hyperpolarized longitudinal spin order within the 13C manifold of agents 1–8 (Table 1). This involved taking [D4]MeOH solutions that contained 20 mm of the substrate, and 5 mm of the IMes catalyst. p‐H2 gas was bubbled through the solution for 20 s in low field and the sample transferred into the NMR spectrometer for further analysis. Figure 2 highlights the results of this process, with the level of 13C polarization reaching about 2 % as compared to the corresponding thermal polarization of only 0.0008 % at 9.4 T in the case of agent 1 after relayed transfer from 1H–13C at 30 G (see Section S6 in the Supporting Information). No H/D‐exchange is observable on the timescale of the SABRE experiment. The relayed transfer process was then examined as a function of the magnetic field experienced by the sample, and three maxima were observed, at about 10 mG (using μ‐metal shield), 30 and 100 G. Simulation revealed the about 10 mG maxima is associated with direct hydride–carbon spin‐spin transfer by the 4 J and 5 J couplings in the catalyst. The remaining maxima appear to result from relayed transfer by the agents 1H response (see Section S4).

Figure 2.

13C NMR spectra of 1 after (a) SABRE at a mixing field 5 mG and corresponding thermally equilibrated signal of 1000 transients. (c) Similar SABRE studies of 7 at a mixing field of 1 mG and (d) its thermal equilibrium spectra acquired by 600 transients.

When agent 2 is examined, the 2H labels should prevent the relayed response that is operating and restrict its transfer to the approximate 10 mG field range. Under these conditions, a strong 13C signal is seen. However, upon moving from 10–150 G, 13C and 1H SABRE enhanced signals are observed in the 1H and 13C frequency ranges. These results reveal readily detectable contributions from the 2H‐1H isotopologue, which is present at 1 %, through the observation of a 13C response that contains a J splitting of 5.4 Hz. This reflects one of the challenges faced when working with hyperpolarization in so far as low‐concentration species can be readily detected. Agents 3 and 5–8 also require direct polarization transfer because there is no suitable relayed transfer pathway and they once again work well between 1 and 20 mG. These 13C hyperpolarization data are summarized in Table 1 (and Section S5). Polarization levels approaching 2 % are readily achieved, which would be expected to increase further through catalyst optimization.36 We then transferred the resulting 13C‐hyperpolarization into singlet order using the methods described earlier. The efficiency of singlet conversion in all successful cases was found to be in the range of 50–80 %.

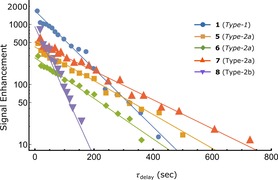

Figure 3 shows the decay of the resulting hyperpolarized 13C singlet derived signals for agents 1, 5–8 as a function of their storage time (T S) in low field. The 13C lifetimes proved to be directly comparable to those measured without hyperpolarization and signals can be readily observed for several minutes after creation when stored in a low‐field region. In the case of 7, hyperpolarized signals were detectable for well over 10 mins.

Figure 3.

Hyperpolarized 13C singlet state decay (log10 scale) as a function of low‐field storage time (τ delay) for agents 1, 5–8. Results are summarized in Table 1.

In summary, we have demonstrated that a series of novel agents can be prepared that contain two adjacent 13C labels in addition to two nitrogen‐based lone pairs, which make them suitable for SABRE. Despite the weak J‐coupling that exists between the hydride ligands and the targeted 13C sites, we achieve a hyperpolarized response at the 2 % level. This hyperpolarization has then been efficiently converted into singlet spin order within the two 13C labels by rf excitation with a low‐field relaxation time of about 190 s being the result for deuterated dimethyl p‐tolyl phenyl pyridazine. This process has been exemplified for both magnetic and chemical inequivalence. Our method provides a fast and low‐cost technique to create 13C hyperpolarization in a reversible fashion with very little waste. Because of the simplicity of this approach, we envisage that this strategy will be adopted more widely to hyperpolarize related tracers. We are currently seeking to improve on the purity of these states to test the in vivo detection of these agents.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary

Acknowledgements

We thank the Wellcome Trust (092506 and 098335) for funding. We are grateful to discussions with Prof. H. Perry. Supporting information via: DOI: 10.151244a012088‐7b46‐4dcb‐96eb‐a1a78e8ffa96.

S. S. Roy, P. Norcott, P. J. Rayner, G. G. R. Green, S. B. Duckett, Chem. Eur. J. 2017, 23, 10496.

References

- 1. Lee J. H., Okuno Y., Cavagnero S., J. Magn. Reson. 2014, 241, 18–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ardenkjaer-Larsen J.-H., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 9162–9185; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2015, 127, 9292–9317. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Natterer J., Bargon J., Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 1997, 31, 293–315. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bowers C. R., Weitekamp D. P., Phys. Rev. Lett. 1986, 57, 2645–2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Golman K., Axelsson O., Johannesson H., Mansson S., Olofsson C., Petersson J. S., Magn. Reson. Med. 2001, 46, 1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Golman K., Ardenaer-Larsen J. H., Petersson J. S., Mansson S., Leunbach I., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 10435–10439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bhattacharya P., Chekmenev E. Y., Perman W. H., Harris K. C., Lin A. P., Norton V. A., Tan C. T., Ross B. D., Weitekamp D. P., J. Magn. Reson. 2007, 186, 150–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nelson S. J., Science Translational Medicine 2013, 5. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Golman K., in't Zandt R., Lerche M., Pehrson R., Ardenkjaer-Larsen J. H., Cancer Res. 2006, 66, 10855–10860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Golman K., in’ Zandt R., Thaning M., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 11270–11275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Day S. E., Kettunen M. I., Gallagher F. A., Hu D.-E., Lerche M., Wolber J., Golman K., Ardenkjaer-Larsen J. H., Brindle K. M., Nat. Med. 2007, 13, 1382–1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Adams R. W., Aguilar J. A., Atkinson K. D., Cowley M. J., Elliott P. I. P., Duckett S. B., Green G. G. R., Khazal I. G., Lopez-Serrano J., Williamson D. C., Science 2009, 323, 1708–1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Eshuis N., van Weerdenburg B. J. A., Feiters M. C., Rutjes F. P. J. T., Wijmenga S. S., Tessari M., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 1481–1484; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2015, 127, 1501–1504. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pravdivtsev A. N., Yurkovskaya A. V., Vieth H.-M., Ivanov K. L., J. Phys. Chem. B 2015, 119, 13619–13629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Heinisch G., Frank H., Prog Med Chem. 1990, 27, 1–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Asif M., Curr. Med. Chem. 2012, 19, 2984–2991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Roy S. S., Rayner P. J., Norcott P., Green G. G. R., Duckett S. B., Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 24905–24911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Roy S. S., Norcott P., Rayner P. J., Green G. G., Duckett S. B., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 15642–15645; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2016, 128, 15871–15874. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Theis T., Sci. Adv. 2016, 2, e1501438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Levitt M. H., in Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem., Vol. 63 (Eds.: M. A. Johnson, T. J. Martinez), 2012, pp. 89–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Warren W. S., Jenista E., Branca R. T., Chen X., Science 2009, 323, 1711–1714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Carravetta M., Levitt M. H., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 6228–6229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Tayler M. C. D., Levitt M. H., Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011, 13, 5556–5560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tayler M. C. D., Marco-Rius I., Kettunen M. I., Brindle K. M., Levitt M. H., Pileio G., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 7668–7671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pileio G., Hill-Cousins J. T., Mitchell S., Kuprov I., Brown L. J., Brown R. C. D., Levitt M. H., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 17494–17497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Stevanato G., Roy S. S., Hill-Cousins J., Kuprov I., Brown L. J., Brown R. C. D., Pileio G., Levitt M. H., Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 5913–5922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Stevanato G., Hill-Cousins J. T., Hakansson P., Roy S. S., Brown L. J., Brown R. C. D., Pileio G., Levitt M. H., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 3740–3743; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2015, 127, 3811–3814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pileio G., Carravetta M., Levitt M. H., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 17135–17139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhang Y., Soon P. C., Jerschow A., Canary J. W., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 3396–3399; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2014, 126, 3464–3467. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Feng Y., Theis T., Wu T.-L., Claytor K., Warren W. S., J. Chem. Phys. 2014, 141, 134307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Claytor K., Theis T., Feng Y., Warren W., J. Magn. Reson. 2014, 239, 81–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Feng Y., Davis R. M., Warren W. S., Nat. Phys. 2012, 8, 831–837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Colell J. F. P., J. Phys. Chem. C 2017, 121, 6626–6634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hövener J.-B., Anal. Chem. 2014, 86, 1767–1774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Pileio G., Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 2010, 56, 217–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rayner P. J., Burns M. J., Olaru A. M., Norcott P., Fekete M., Green G. G. R., Highton L. A. R., Mewis R. E., Duckett S. B., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2017, 114, E3188–E3194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary