Abstract

LC-UV/MS-based metabolomic analysis of the Hawaiian endophytic fungus Paraphaeosphaeria neglecta FT462 led to the identification of four unique mercaptolactated γ-pyranol–γ-lactams, paraphaeosphaerides E–H (1–4) together with one γ-lactone (5) and the methyl ester of compound 2 (11). The structures of the new compounds (1–5 and 11) were elucidated through the analysis of HRMS and NMR spectroscopic data. The absolute configuration was determined by chemical reactions with sodium borohydride, hydrogen peroxide, α-methoxy-α-(trifluoromethyl)phenylacetyl chlorides (Mosher reagents), and DP4 + NMR calculations. All the compounds were tested against STAT3, A2780 and A2780cisR cancer cell lines, E. coli JW2496, and NF-κB. Compounds 1 and 3 strongly inhibited NF-κB with IC50 values of 7.1 and 1.5 μM, respectively.

Introduction

Endophytic fungi are rich in biologically active secondary metabolites1–13. Our previous investigation of the Hawaiian endophytic fungus Paraphaeosphaeria neglecta FT462 had led to the identification of a few phaeosphaeride A analogs including paraphaeosphaeride A, a unique γ-pyranone–γ-lactam–1,4-thiazine derivative, and we had proposed a biosynthetic pathway for paraphaeosphaeride A2. We also proposed an intermediate structure that could be generated from mercaptolactate and phaeosphaeride A, which showed STAT3 inhibition2, 3. Motivated by the unusual structures of paraphaeosphaeride A and the assumed intermediates, we reinvestigated the Hawaiian endophytic fungus Paraphaeosphaeria neglecta FT462 for mercaptolactated γ-pyranol/pyranone–γ-lactam analogs as presented in the proposed biosynthetic pathways of paraphaeosphaeride A and phaeosphaeride A.

The fungus Paraphaeosphaeria neglecta FT462 was cultured under static conditions at room temperature for 30 days in a conical flask (1 L) containing 300 mL/flask liquid MDY medium. The fermented whole broth (6 L) of FT462 was filtered through filter paper, and the mycelia were extracted with 80% acetone/water followed by concentration under reduced pressure to afford an aqueous solution. The supernatant solution and the aqueous mycelia extraction was combined and passed through HP-20 eluted with MeOH-H2O (10, 30, 50, 70, 90% methanol in H2O) to afford five fractions (Fr. A–E). Fractions A–E were analyzed by LC/HRMS. Molecular ion extraction at 420.1–420.2 (positive mode, [C18H29NO8S + H]) identified two peaks (I and II) in fraction B. Besides I and II, one more peak (III) with similar UV to I and II was also detected, and it had the quasi-molecular ion peak at 436.1647 [C18H29NO9S + H], which was 16 units more than I and II. Fraction B was further separated by preparative HPLC and semi-preparative HPLC to yield compounds 1–3 together with compounds 4, 5 (Fig. 1) and the methyl ester of compound 2 (11), which might be an artifact produced during extraction and separation. Compounds 1–3 corresponded to I-III, respectively. In this report, the separation, structural elucidation, determination of absolute configuration with chemical reaction and NMR calculation, and biological activity are presented.

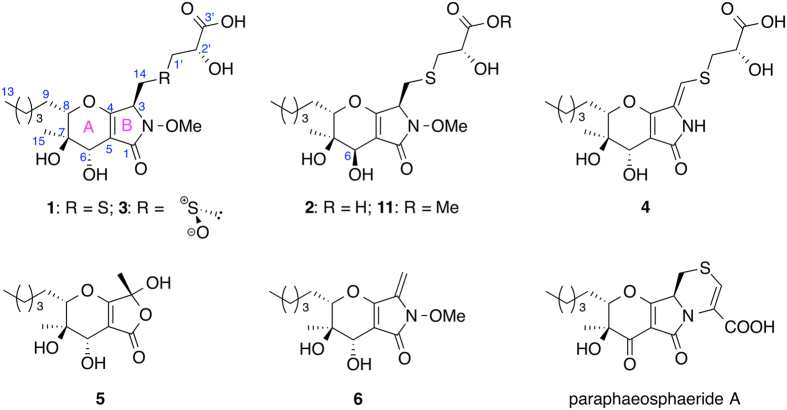

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of 1–6, 11 and paraphaeosphaeride A.

Results and Discussion

Compound 1 was isolated as a light yellowish solid. Its molecular formula was determined to be C18H29NO8S based on a high resolution ESI-MS [M + H]+ of 420.1678 (calcd for C18H30NO8S, 420.1687), with 5 degrees of unsaturation. A detailed analysis of 1H and 13C NMR spectra (Table 1) demonstrated the presence of one methoxyl, two methyl signals, six methylenes with two connected to sulfur (δ H 3.01/3.35 and 2.90/2.98, δ C 33.6 and 38.4), four methines including three oxygenated and one nitrogenated (δ H 4.42, δ C 62.3), and five other carbons with no hydrogen attached, four of which are sp 2 hybridized, including two carbonyl carbons. The NMR data of 1 were very similar to that of phaeosphaeride A (6) except that the olefinic methylene (H2-14) in the molecule of 6 was absent in that of 1. Meanwhile, two more methines with one oxygenated(CH–O) and another nitrogenated (CH–N) and two more methylenes connected to sulfur (2 × CH2–S) were present in 1. One α,β-unsaturated γ-lactam (δ C 175.7) and two rings (A and B) accounted for four degrees of unsaturation. The remaining degree of unsaturation was supported by the existence of one carbonyl group (δ C 175.9). Therefore we could argue that 1 was derived from 6 (phaeosphaeride A) and mercaptolactate (HS-CH2-CHOH-COOH) as proposed in our previous publication2. The HMBC spectrum of 1 demonstrated correlations from H2-14 to C-1′ and from H2-1′ to C-14, and the COSY-coupled H2-1′ and H-2′ showed HMBC correlations to C-3′ (Fig. 2), which justified our argument. Hence, the planar structure of compound 1 was elucidated as shown in Fig. 2, which has the same planar structure as CAS# 1214709-65-5, but no reference was provided for CAS# 1214709-65-5 and its stereogenic centers were not determined.

Table 1.

1H and13C NMR Spectroscopic Data for Compounds 1–5 in Methanol-d 4.

| # | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| δH, mult (J in Hz)a | δC b | δH, mult (J in Hz)a | δC b | δH, mult (J in Hz)a | δC b | δH, mult (J in Hz)a | δC b | δH, mult (J in Hz)a | δC b | |

| 1 | 175.7 | 174.4 | — | 175.0 | 174.7 | |||||

| 2-OMe | 3.86 s | 65.0 | 3.82 s | 64.9 | 3.90 s | 64.8 | ||||

| 3 | 4.42 t (6.0) | 62.3 | 4.48 t (6.0) | 61.8 | 4.61 t (5.5) | 58.6 | 130.2 | 102.5 | ||

| 4 | 168.6 | 168.4 | 169.3 | 159.5 | 174.7 | |||||

| 5 | 106.6 | 107.6 | 105.6 | 105.7 | 102.0 | |||||

| 6 | 4.02 brs | 66.6 | 4.17 brs | 68.2 | 4.00 brs | 66.3 | 4.13 brs | 67.5 | 4.05 brs | 66.5 |

| 7 | 72.8 | 72.4 | 72.4 | 73.0 | 72.4 | |||||

| 8 | 4.10 br d (12.0) | 88.7 | 4.04 br d (12.0) | 88.3 | 4.15 br d (11.2) | 89.1 | 4.03 br d (12.0) | 87.6 | 4.17 br d (12.0) | 88.6 |

| 9 | 1.60 m; 1.93 m | 29.5 | 1.73 m; 1.80 m | 29.0 | 1.64 m; 1.91 m | 29.2 | 1.66 m; 1.86 m | 29.1 | 1.66 m; 1.90 m | 28.9 |

| 10 | 1.37 m; 1.60 m | 28.1 | 1.37 m; 1.58 m | 27.6 | 1.40 m; 1.64 m | 27.7 | 1.39 m; 1.57 m | 27.7 | 1.39 m; 1.58 m | 27.2 |

| 11 | 1.35 m | 32.7 | 1.33 m | 32.7 | 1.34 m | 32.3 | 1.34 m | 32.5 | 1.34 m | 32.1 |

| 12 | 1.36 m | 23.7 | 1.34 m | 23.6 | 1.35 m | 23.4 | 1.34 m | 23.4 | 1.35 m | 23.1 |

| 13 | 0.91 t (6.0) | 14.4 | 0.91 t (6.0) | 14.4 | 0.92 t (6.0) | 14.2 | 0.91 t (6.0) | 13.9 | 0.91 t (6.0) | 13.9 |

| 14 | 3.01 dd (18.0, 6.0); 3.35 dd (18.0, 6.0) | 33.6 | 3.01 dd (18.0, 6.0); 3.29 dd (18.0, 6.0) | 33.1 | 3.54 m | 52.1 | 6.31 s | 110.5 | 1.64 s | 22.9 |

| 15 | 1.31 s | 20.0 | 1.23 s | 20.0 | 1.32 s | 19.8 | 1.28 s | 18.8 | 1.32 s | 19.4 |

| 1′ | 2.90 dd (14.0, 6.0); 2.98 dd (14.0, 4.0) | 38.4 | 2.81 dd (18.0, 8.7); 2.98 dd (18.0, 5.0) | 38.3 | 3.08 m; 3.51 m | 57.4 | 3.10 m; 3.27 m | 39.8 | ||

| 2′ | 4.34 dd (6.0, 4.0) | 72.5 | 4.29 dd (8.7, 5.0) | 72.2 | 4.40, brd (8.1) | 66.9 | 4.29 brs | 72.2 | ||

| 3′ | 175.9 | 175.9 | — | 177.5 | ||||||

aSpectra recorded at 500 MHz (but 400 MHz for 4 and 5). bSpectra recorded at 125 MHz (but 100 MHz for 4 and 5). Data based on 13C, HSQC, and HMBC experiments.

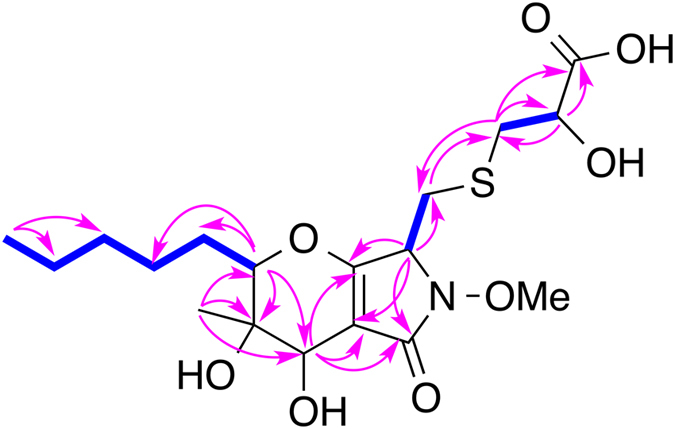

Figure 2.

Key 1H-1H COSY (bolds) and HMBC (arrows) correlations of 1.

Compound 2 was also isolated as a light yellowish solid. Its molecular formula was determined to be C18H29NO8S (calcd for C18H30NO8S, 420.1687) based on a high resolution ESI-MS [M + H]+ of 420.1677, which was the same as that of 1. The 1H and 13C NMR data of 2 were almost identical to those of 1 except position 6. The planar structure of compound 2 was determined to be the same as that of 1 based on its 1D and 2D NMR data. We proposed that compound 2 was derived from the 6-epimer of 6 and mercaptolactate (HS-CH2-CHOH-COOH), which meant that 1 and 2 differed in configuration only at C-6.

Compound 3 was isolated as light yellowish solids. Its molecular formula was determined to be C18H29NO9S (calcd for C18H28NO9S, 434.1490) based on a high resolution ESI-MS [M − H]− of 434.1503, which was 16 units more than the molecular formula (C18H29NO8S) of 1 and 2. The 1H and 13C NMR data of 3 were almost identical to those of 1 except the side chains at 3-position, which had the same 1H-1HCOSY and HMBC correlations as those of compounds 1 and 2. We assumed that the functional group between 14-position and 1′-position was a sulfoxide in 3 instead of a sulfide in 1 and 2. Hence, the planar structure 3 was determined as shown.

Compound 4 was isolated as a light yellowish solid. Its molecular formula was determined to be C17H25NO7S (calcd for C17H26NO7S, 388.1424) based on a high resolution ESI-MS [M + H]+ of 388.1418. The 1H NMR of 4 was similar to that of compound 1, except that the N-methoxyl group and the CH-CH2 spin system at 3- and 14-positions in the molecule of 1 were absent in that of 4. Meanwhile, one olefinic proton at δ H 6.31 presented in 4. This olefinic proton was assigned to H-14 readily since it showed HMBC correlations to C-3, C-4, and C-1′. Compound 4 was the N-demethoxyl and 3,14-dehydrogenated product of 1. Hence, the structure of compound 4 was determined as shown.

Compound 5 was isolated as a colorless solid. Its molecular formula was determined to be C14H22O6 (calcd for C14H23O6, 287.1489) based on a high resolution ESI-MS [M + H]+ of 287.1476. The 1H NMR signals in the 4-dihydropyranol (ring A) and the side chain at 8-position of 5 were almost the same as those of compound 6, while the N-methoxyl group and the olefinic protons at 14-position in ring B of 6 were absent in 5. Instead, a third methyl group at δH 1.64 ppm was observed in the 1H NMR spectrum of 5. The signal at δ H 1.64 ppm showed HMBC correlations to C-3 (δ C 102.5) and C-4 (δ C 174.7) indicating C-3 of 5 must be di-oxygenated, and 5 should be a lactone instead of a lactam. Hence, the structure of compound 5 was determined as shown.

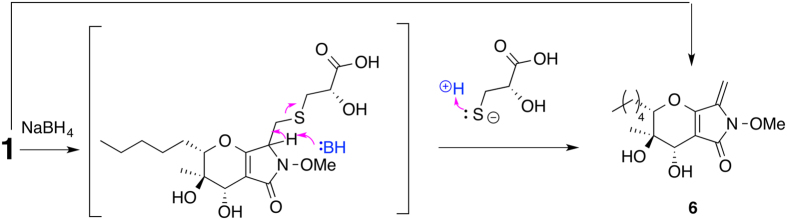

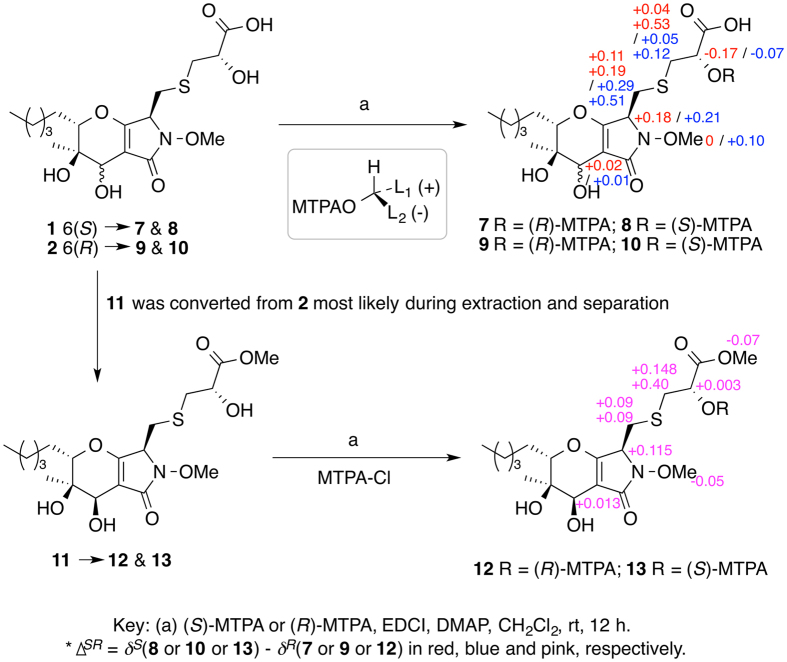

To determine the configuration of 3-position of 1, 1 was treated with sodium borohydride14. We expected the double bond between A- and B-rings would be reduced so that we could run a ROESY NMR experiment, but instead the reaction yielded phaeosphaeride A (6) (Fig. 3), indicating that the configuration of ring A of 1 was the same as that of 6. In order to determine the configuration of C-2′, 1 and 2 were reacted with R- and S-Mosher reagents15. Results showed that both 1 and 2 should have an S configuration at 2′-position (Fig. 4). To determine the absolute configuration unequivocally by the modified Mosher’s method, the ∆SR values on both left and right sides of a secondary alcohol should be calculated and the sign distributions should be consistent. Unfortunately, the ∆SR value at the carboxylic acid proton for either compounds 8 and 7, or 10 and 9 couldn’t be obtained. Fortunately, we isolated the methyl ester of compound 2 (11), which was reacted with both S- and R-Mosher reagents to yield two Mosher esters (12 and 13, Fig. 4). Result clearly showed negative ∆SR values for both H-2′ and the methoxy at 3′ position, and positive ∆SR values for the others (Fig. 4). Hence, the configuration of 1 at 2′-position was determined without any doubt.

Figure 3.

Conversion of 1 to 6 under basic condition.

Figure 4.

Reactions of 1, 2 and 11 with Mosher reagents.

In our previous study, we determined the configuration at C-3 of paraphaeosphaeride A as S from experimental and calculated Electronic Circular Dichroism (ECD) analysis2. Given the close structural similarity of the former natural product with 1 and 2, we hypothesized that the absolute configuration at C-3 should be also S in both newly isolated compounds. In order to confirm our deduction, we next carried out DFT calculations of the NMR shifts using the GIAO method16, 17. This approach has been extensively employed recently to settle the structure and stereochemistry of complex natural or synthetic products, and emerges as a suitable alternative to propose the most likely structure of an organic compound in a simple and affordable fashion16–21. Among the several strategies that have been developed to support (or reject) a given structural proposal17, 22–26, we decided to use the DP4 + probability, the method of choice for assessing the most likely candidate when only one set of experimental data is available (as in this case)23. This probability is an updated and improved version of the DP4 method (developed by the Goodman group)25 that includes the use of both scaled and unscaled chemical shifts computed at higher levels of theory. Thus, following the DP4 + methodology, we computed the NMR shifts at the PCM/mPW1PW91/6-31 + G**//PCM/B3LYP/6-31G* level of theory using methanol as solvent. Since the NMR data of compounds 1 and 2 were collected in CD3OD, here we also include the solvent effect during the geometry optimization stage. Confirming our hypothesis, the calculated values for the two isomers with the S configuration at C-3 (1–3 S and 2–3 S) (Tables 2 and SI) showed better agreement with the experimental data than those corresponding to the 3R counterparts (1–3 R and 2–3 R, respectively). For instance, the CMAE (corrected mean average error, defined as Σn|δscaled − δexp|/n) computed for 1–3 S and 2–3 S from 13C NMR data were 1.0 ppm and 1.1 ppm, respectively, lower than those calculated for 1–3 R (1.6 ppm) and 2–3 R (1.8 ppm). In a similar fashion, the CMAE values calculated from 1H NMR data were lower for 1–3 S (0.10 ppm) and 2–3 S (0.08 ppm) than those of 1–3 R (0.11 ppm) and 2–3 R (0.10 ppm), respectively. The isomers with a 3R configuration (1–3 R and 2–3 R) also displayed higher outliers (CMaxErr, corrected maximum error, defined as max|δscaled − δexp|) values (7.3 ppm and 4.4 ppm, respectively, for 13C data; 0.50 and 0.24 ppm, respectively, for 1H data) in comparison with the corresponding values of 1–3 S and 2–3 S (3.3 ppm and 4.0 ppm, respectively, for 13C data; 0.24 and 0.21 ppm, respectively, for 1H data). The better fit of 1–3 S and 2–3 S was further corroborated with DP4 + calculations, where each isomer was identified as the most likely candidates in high probability (>99.9% in both cases).

Table 2.

Scaled (δs) 1H and 13C NMR chemical shifts of the more likely structures of 1–5 computed at the PCM/mPW1PW91/6–31 + G**//PCM/B3LYP/6–31 G* level of theory (solvent = methanol).

| # | 1–3S | 2–3S | 3-SS | 4–3Z | 5–3R | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| δH | δC | δH | δC | δH | δC | δH | δC | δH | δC | |

| 1 | 175.8 | 174.2 | 169.4 | 169.6 | ||||||

| 2-OMe | 3.88 | 64.1 | 3.80 | 64.1 | 3.92 | 63.9 | ||||

| 3 | 4.18 | 64.0 | 4.27 | 62.9 | 4.32 | 60.7 | 129.3 | 104.3 | ||

| 4 | 169.2 | 170.1 | 167.7 | 159.2 | 175.5 | |||||

| 5 | 106.5 | 105.9 | 105.8 | 104.1 | 104.0 | |||||

| 6 | 4.18 | 67.4 | 4.37 | 65.6 | 4.44 | 70.7 | 4.48 | 73.1 | 4.27 | 70.9 |

| 7 | 74.9 | 72.8 | 72.8 | 73.6 | 73.4 | |||||

| 8 | 4.26 | 88.7 | 4.17 | 86.9 | 4.14 | 88.3 | 3.81 | 87.1 | 3.96 | 89.7 |

| 9 | 2.16; 1.51 | 28.7 | 1.70; 1.56 | 29.4 | 1.85; 1.80 | 28.4 | 1.87; 1.67 | 27.9 | 1.87; 1.74 | 28.2 |

| 10 | 1.66; 1.25 | 27.2 | 1.61; 1.36 | 27.9 | 1.69; 1.30 | 28.5 | 1.49 | 27.8 | 1.50 | 27.9 |

| 11 | 1.23 | 32.1 | 1.30 | 32.8 | 1.30 | 32.9 | 1.31 | 32.6 | 1.31 | 32.8 |

| 12 | 1.34 | 23.8 | 1.38 | 24.4 | 1.41 | 24.6 | 1.37 | 24.1 | 1.33 | 24.3 |

| 13 | 0.92 | 12.6 | 1.00 | 13.2 | 0.96 | 14.0 | 0.98 | 13.1 | 0.98 | 13.3 |

| 14 | 3.18 | 34.0 | 3.12 | 33.7 | 3.32 | 56.4 | 6.24 | 117.4 | 1.67 | 20.6 |

| 15 | 1.44 | 18.6 | 1.28 | 19.1 | 1.21 | 14.1 | 1.15 | 11.8 | 1.21 | 14.3 |

| 1′ | 2.78 | 41.7 | 2.95 | 42.3 | 3.30 | 51.8 | 3.10 | 42.9 | ||

| 2′ | 4.32 | 71.7 | 4.25 | 71.2 | 4.48 | 68.4 | 4.35 | 71.7 | ||

| 3′ | 174.0 | 176.4 | 176.9 | |||||||

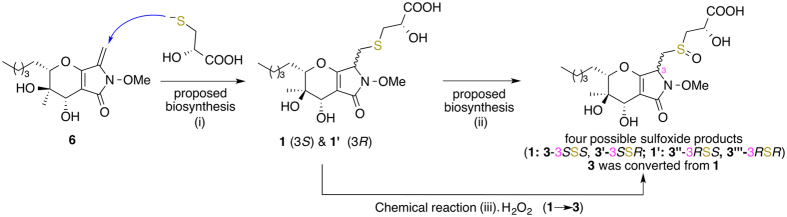

Reduction of compound 3 with sodium borohydride also yielded compound 6. As proposed in our previous publication2, nucleophilic addition of the mercaptolactate thiol to C-14 of compound 6 could generate 1 and its 3-epimer (1′, which was not isolated from Paraphaeosphaeria neglecta FT462 in this study). Further oxidation of 1 and 1′ could yields four sulfoxides including 3 (3, 3′, 3″, and 3′″, Fig. 5). From a biosynthetic point of view, 3 should have the same configuration at 2′-position as 1 and 2. To confirm the above assumption, 1 was treated with hydrogen peroxide and tert-butyldimethyl silyl chloride27, and compound 3 was detected (Fig. 5). However, the configuration at the sulfoxide in 3 was still not determined. Once again, the two possible isomers of 3 (3-S R and 3-S S) were submitted to NMR calculation at the PCM/mPW1PW91/6-31 + G**//PCM/B3LYP/6-31 G* level of theory (Tables 2 and SI). In this case, the 13C and 1H NMR data pointed toward different directions, which is a common situation in the field of quantum calculations of NMR shifts16–26. For instance, the CMAE and CMaxErr computed for 3-S R using 13C NMR data (1.8 ppm and 5.4 ppm, respectively) were slightly lower than those calculated for 3-S S (1.9 ppm and 5.7 ppm, respectively), whereas using the experimental 1H NMR shifts the trend was reversed (0.14 ppm and 0.56 ppm, respectively, for 3-S R; 0.11 and 0.44 ppm for 3-S S). In this case, proton data was the most conclusive one, and isomer 3-S S was identified as the correct structure of 3 in high probability (99.5%) after DP4 + calculations.

Figure 5.

Proposed biosynthesis of two sulfides (1 and 1′) and four sulfoxides (3, 3′, 3″, and 3′″) (steps i and ii). Chemical conversion of 1 to 3 (step iii) with hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). 1′, 3′, 3″, and 3′″ were not isolated.

Two more peaks, each of which has the same molecular weight as that of 3, were detected in the LC-MS of fraction B. Most likely, they are diastereoisomers of 3 with different configurations at the sulfoxide, 3-, and 6-positions since all the analogs that we isolated have the same configurations at 7- and 8-positions. We tried to isolate these compounds and determined their structures, but failed due to insufficient material and instability of these molecules. Nevertheless, it is worthy to investigate these compounds further.

In the case of compounds 4 and 5, we concluded that they should have the same configurations at C-6, C-7 and C-8 as those of 1 since minor differences in the 13C NMR shifts were noted at those centers. Also, from a biosynthetic point of view, 4 should have the same configuration at 2′-position as 1–3. However, as throughout this study, we were not able to unequivocally determine the configuration at C-3 from experimental NMR basis, and we had to rely on the computational chemistry assistance to settle this issue. Thus, the NMR calculations of the two possible isomers of 4 (4–3 E and 4–3 Z) and 5 (5–3 R and 5–3 S) were carried out at the PCM/mPW1PW91/6–31 + G**//PCM/B3LYP/6-31G* level of theory (Table 2, Tables S4 and S5). In the case of 4, the 3Z isomer displayed much better agreement with the experimental values than the 3E candidate, mainly in the 13C NMR region, in which lower CMAE (2.2 ppm vs 2.9 ppm) and CMaxErr (7.0 ppm vs 14.2 ppm) was noted. On the other hand, the computed 13C NMR shifts of 5-3 R and 5–3 S showed similar match with the experimental shifts (CMAE 2.0 ppm in both cases), though the prediction of the 1H NMR data was improved in the case of 5–3 R (CMAE = 0.08 ppm vs 0.09 ppm; CMaxErr 0.22 ppm vs 0.25 ppm). The DP4 + calculations were in line with these findings, suggesting that the most likely configuration at C-3 of 4 and 5 is Z (>99.9%) and R (92.2%), respectively. ROESY correlations between H-14 and H-6, and H-14 and H-8 further confirmed the configuration of 5.

All the compounds (1–5, 11) were tested against STAT3, A2780 and A2780S, but none was active at the concentration of 20 μg/mL. The compounds were also evaluated for their activity against pathogenic bacteria, S. aureus, C. difficile, P. aeruginosa PAO1, and E. coli JW2496 (∆bamB). Only compound 1 mildly inhibited E. coli JW2496 at 20 μg/mL.

Since phaeosphaeride A showed STAT3 inhibition2, 3, and NF-κB and STAT3 act as two major transcriptional factors linking inflammation with cancer progression, and they functionally interact with each other at many different levels, we tested all compounds for their ability to inhibit NF-κB and iNOS. When evaluated in a mammalian cell-based assay designed to monitor TNF-α-induced NF-κB activity, compounds 1 and 3 were found to mediate inhibitory responses with IC50 values of 7.1 and 1.5 μM (Table 3), respectively. When tested using the same conditions as the NF-κB assay, none showed toxicity (Table 3). In the absence of a cytotoxic response, inhibition of TNF-α-induced NF-κB activity suggests the potential of a cancer chemopreventative response. Compounds 1 and 3 also inhibited iNOS with IC50 values of 47.9 and 16.1 μM (Table 3), respectively. According to the structures and NF-κB activity, it could be concluded that the sulfoxide (3) was more active than the sulfide derivatives (1 and 2), and the configuration at 6-position (6S) was also important for the NF-κB inhibition.

Table 3.

Inhibitory effect of compounds 1 and 3 against TNF-α-induced NF-κB and lipopolysaccharide-stimulated iNOS activity.

| Compound | NF-κB inhibition IC50 (μM) | NF-κB cytotoxicity IC50 (μM) | iNOS inhibition IC50 (μM) | iNOS cytotoxicity IC50 (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 7.1 | >50 | 47.9 ± 0.03 | >50 |

| 2 | — | >50 | 43.2 ± 0.7 | >50 |

| 3 | 1.5 | >50 | 16.1 ± 6.6 | >50 |

| TPCKa | 4.09 ± 0.12 | |||

| l-NMMAb | 18.8 ± 3.4 |

aTPCK: N α-tosyl-l-phenylalanine chloromethyl ketone was used as a positive control in NF-κB assay.

bl-MNNA: Na-l- monomethyl arginine was used as a positive control in iNOS assay.

Paraphaeosphaeria species produce different types of secondary metabolites, including macrolides28, 29, xanthenes30, isocoumarins31, hexaketide32, polyketides33, 34, and phaeosphaerides2 and paraphaeosphaerides1, 2, 8, 35. Paraphaeosphaeride A2 is the first sulfur-containing molecule (a sulfide) isolated from Paraphaeosphaeria species. In this study, we isolated four more sulfides (1, 2, 4, and 11) and a sulfoxide (3) together with a γ-lactone (5). The configuration of these compounds was determined by NMR, DP4 + calculations and chemical reactions. Thio- or sulfide or even di-sulfide fungal metabolites are not rare, but sulfoxides isolated from fungi were uncommon, for examples, oryzamides D and E from the sponge-derived fungus Nigrospora oryzae PF1836, and cyclosulfoxicurvularin from the marine-derived Penicillium sp. DRF237. The identification of paraphaeosphaerides E-H (1–4) confirmed our proposed biosynthesis of paraphaeosphaeride A2. So far, only a few phaeosphaeride derivatives have been reported, and phaeosphaeride A showed STAT3 inhibitory activity2, 3. All compounds were evaluated for their anti-proliferative, antibacterial, NF-κB and iNOS inhibitory activities. Since compounds 1 and 3 inhibited NF-κB with some specificity, they remain of interest as cancer chemopreventative agents.

Methods

General Experimental Procedures

Optical rotations were measured with a Rudolph Research Analytical Autopal IV Automatic polarimeter. UV and IR spectra were obtained with Shimadzu UV-1800 spectrophotometer and Thermo scientific Nicolet iS50FT-IR spectrometer, respectively. NMR spectra were recorded in methanol-d 4 on Varian Unity Inova 500 MHz and Bruker 400 MHz. High resolution mass spectra were obtained an Agilent Q-TOF Ultima ESI-TOF mass spectrometer. HPLC was carried out on Agilent 1100 LC system using a Phenomenex Luna C18 column (100 mm × 21.2 mm, 5 μm particle size), a Phenomenex Luna phenyl-hexyl column (250 mm × 10 mm, 5 μm particle size) and a Phenomenex Luna C18 HPLC column (250 mm × 10 mm, 5 μm particle size). Column chromatography used Diaion HP-20 (Sigma).

Isolation and Identification of Fungal Strain

The fungal strain2 was isolated on PDA medium from a healthy leaf of Hawaiian indigenous plant, Lycopodiella cernua (L.) Pic. Serm, which was collected in the Mokuleia Forest Reserve in 2014. The strain was identified as Paraphaeosphaeria neglecta (similarity 99.8%) based on comparison result of the DNA sequence of the nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer (ITS) with Genbank. A voucher specimen was deposited at University of Hawaii Cancer Center, USA (accession no. UHCCFT-462).

Fermentation, Extraction and Isolation

The fungal strain FT462 was cultured under the same condition as that of our previous study1. The fermented whole broth (6 L) was filtered through filter paper to separate the supernatant from the mycelia. The later was extracted by 80% acetone/H2O 3 times, and the solution was concentrated under reduced pressure to afford an aqueous solution. The combination liquid of the supernatant solution and the mycelia extraction was passed through HP-20 eluted with MeOH-H2O (10, 30, 50, 70, 90%) to afford five fractions (Fr. A-E). Fr. B (1.78 g) was further fractionated by preparative HPLC (C18 column, 5 μm; 100.0 × 21.2 mm; 15 mL/min; with 0.1% formic acid in mobile phases) eluted with 20–100% MeOH-H2O in 30 min to get 30 sub-fractions (SF.1–30). SF.15 was pure enough for NMR analysis, which was compound 1 (22.12 mg). SF.16 (183.02 mg) was further subjected to semi-preparative HPLC (phenyl-hexyl column, 5 μm; 250.0 mm × 10.0 mm; 3 mL/min; with 0.1% formic acid in 25% CH3CN/H2O) to obtain compounds 2 (25.20 mg, t R 28.7 min) and 3 (2.72 mg, t R 31.3 min). SF.22 (37.08 mg) was separated by semi-preparative HPLC (C18 column, 5 μm; 250.0 mm × 10.0 mm; 3 mL/min), which was eluted from 40% to 55% of CH3OH/H2O for 15 min, followed by 55% CH3OH/H2O for 30 min, to obtain compounds 4 (1.25 mg, t R 26.9 min) and 5 (1.32 mg, t R 28.0 min). SF.26 (57.16 mg) was separated by semi-preparative HPLC (C18 column, 5 μm; 250.0 mm × 10.0 mm; 3 mL/min; with 0.1% formic acid in 65% CH3OH/H2O) to yield compound 11 (8.7 mg, t R 9.2 min).

Paraphaeosphaeride E (1)

yellowish solid; –32.6 (c = 1.4, MeOH). UV (MeOH) λmax 216 nm; IR (film) νmax 3390, 2956, 2927, 2859, 1698, 1655, 1439, 1378, 1266, 1259, 1229, 1091, 1019, 922 cm−1; 1H (methanol-d 4, 500 MHz) and 13C NMR (methanol-d 4, 125 MHz) data, see Table 1; HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z: [M + H]+ Calcd for C18H30NO8S 420.1687, Found 420.1678; m/z: [M + Na]+ Calcd for C18H29NO8SNa 442.1506, Found 442.1493.

Paraphaeosphaeride F (2)

yellowish solid; –66.7 (c = 2.2, MeOH). UV (MeOH) λmax 216 nm; IR (film) νmax 3397, 2955, 2930, 2860, 1699, 1655, 1436, 1378, 1288, 1260, 1224, 1093, 1046, 1019, 924 cm−1; 1H (methanol-d 4, 500 MHz) and 13C NMR (methanol-d 4, 125 MHz) data, see Table 1; HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z: [M + H]+ Calcd for C18H30NO8S 420.1687, Found 420.1677; m/z: [M + Na]+ Calcd for C18H29NO8SNa 442.1506, Found 442.1503.

Paraphaeosphaeride G (3)

yellowish solid; –27.8 (c = 0.36, MeOH). UV (MeOH) λmax 217 nm; IR (film) νmax 3362, 2956, 2930, 2859, 2819, 1708, 1632, 1579, 1440, 1379, 1367, 1130, 1087, 1023, 944 cm−1; 1H (methanol-d 4, 400 MHz) and 13C NMR (methanol-d 4, 100 MHz) data, see Table 1; HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z: [M − H]− Calcd for C18H28NO9S 434.1490, Found 434.1503.

Paraphaeosphaeride H (4)

yellowish solid; –31.6 (c = 0.22, MeOH). UV (MeOH) λmax 202, 327 nm; IR (film) νmax 3332, 2966, 2927, 2857, 2360, 2343, 1673, 1634, 1603, 1409, 1379, 1262, 1165, 1077, 907 cm−1; 1H (methanol-d 4, 400 MHz) and 13C NMR (methanol-d 4, 100 MHz) data, see Table 1; HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z: [M + H]+ Calcd for C17H26NO7S 388.1424, Found 388.1418.

Paraphaeosphaeride I (5)

colorless solid; –29.4 (c = 0.17, MeOH). UV (MeOH) λmax 232 nm; IR (film) νmax 3362, 2957, 2931, 2861, 1744, 1681, 1600, 1422, 1378, 1305, 1176, 1126, 1068, 1035 cm−1; 1H (methanol-d 4, 400 MHz) and 13C NMR (methanol-d 4, 100 MHz) data, see Table 1; HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z: [M + H]+ Calcd for C14H23O6 287.1489, Found 287.1476; m/z: [M + Na]+ Calcd for C14H22O6Na 309.1309, Found 309.1290.

Methyl ester of paraphaeosphaeride F (11)

yellowish solid; –54.3 (c = 0.28, MeOH). UV (MeOH) λmax 218 nm; IR (film) νmax 3392, 2956, 2931, 2860, 2359, 2342, 1738, 1702, 1658, 1438, 1378, 1287, 1260, 1221, 1179, 1091, 1049, 1019, 924 cm−1; 1H (methanol-d 4, 400 MHz) 4.52 (t, H-3), 4.37 (dd, H-2′), 4.20 (brs, H-6), 4.06 (d, H-8), 3.86 (s, 2-OMe), 3.77 (s, 3′-OMe), 3.29 (dd, H-14), 3.02 (dd, H-14), 2.98 (dd, H-1′), 2.85 (dd, H-1′), 1.84 (m, H-9), 1.78 (m, H-9), 1.63 (m, H-10), 1.43 (m, H-10), 1.40 (m, H-12), 1.39 (m, H-11), 1.27 (s, H-15), 0.91 (t, H-13); 13C NMR (methanol-d 4, 100 MHz) 175.5 (C-1), 169.2 (C-4), 108.4 (C-5), 89.2 (C-8), 73.3 (C-7), 69.9 (C-6), 65.7 (2-OMe), 62.6 (C-3), 53.5 (3′-OMe), 38.9 (C-1′), 33.9 (C-14), 33.5 (C-11), 29.9 (C-9), 28.4 (C-10), 24.5 (C-12), 18.9 (C-15), 15.2 (C-13); HRMS (ESI-TOF) m/z: [M + H]+ Calcd for C19H31NO8S 434.1765, Found 433.1773;

Reduction, Mosher reaction and oxidation

Reduction with Sodium Borohydride (NaBH4)

A stirred solution of 1 (5 mg, 11.93 µmol) in THF (850 µL) was added acetic acid (11.93 µmol, dissolved in THF), which was followed by NaBH4 (13.12 µmol) at 0 °C. The mixed solution was stirred for a further 1 h, and then for 8 h at room temperature. Then, the solvent was removed in vacuum, and the residue was partitioned between EtOAc and saturated NaHCO3 solution. The EtOAc part was purified by semi-preparative HPLC to yield compound 6.

Reaction with Mosher reagents

Acylation of compound 1 with S-(+) and R-(−)-α-methoxy-α-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl acetyl chloride (MTPA-Cl) yielded 2′-MTPA esters 7 and 8, respectively (Fig. 4). The same reaction was also performed with compounds 2 and 11 to obtain their 2′-MTPA esters 9 and 10 (Fig. 4), and 12 and 13, respectively. The 1H NMR signals of the MTPA esters were assigned on the basis of their COSY spectra, and the δH(S–R) values were then calculated (Fig. 4).

Oxidation with hydrogen peroxide (H2O2)

A solution of compound 1 (4.18 mg, 10 µmol) in acetonitrile (500 µL) was added 30% H2O2 (2 µL, 20 µmol) and tert-butyldimethylsilyl chloride (1.51 mg, 10 µmol) at room temperature. The mixture was stirred for 20 min before adding 500 µL H2O to quench the reaction. The mixed solution was extracted by EtOAc and solvent was removed in vacuum.

Anti-proliferative, antibacterial, NF-kB and iNOS assays

Anti-proliferative Assays

Viability of normal mouse fibroblasts (NIH3T3) and two Stat3-activated cancer cell lines, MDA-MB-231 (breast cancer) and U251 MG (glioblastoma) cells was determined using the CyQuant assay according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Life Technologies, CA, USA)38, 39. Briefly, cells were cultured in 96-well plates at 1000 cells per well for 24 h and subsequently treated with compounds (20 μg/mL) for 72 h and analyzed. Relative viability of the treated cells was normalized to the DMSO-treated control cells38, 39.

Antibacterial assay

MIC values were determined against E. coli JW2496 (∆bamB) and other bacteria using the standard microbroth dilution method exactly as previously described40, which is based on the methods by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute41, 42. The maximum test concentration used was 20 μg/mL.

NF-κB assay

We employed human embryonic kidney cells 293, Panomic for monitoring changes occurring along the NF-κB pathway43. Stable constructed cells were seeded into 96-well plates at 20 × 103 cells per well. Cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (Invitrogen Co.), supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 units/mL penicillin, 100 μg/mL streptomycin, and 2 mM L-glutamine. After 48 h incubation, the medium was replaced and the cells were treated with various concentrations of test substances. TNF-α (human, recombinant, E. coli, Calbiochem) was used as an activator at a concentration of 2 ng/mL (0.14 nM). The plate was incubated for 6 h. Spent medium was discarded, and the cells were washed once with PBS. Cells were lysed using 50 μL (for 96-well plate) of reporter lysis buffer from Promega by incubating for 5 min on a shaker, and stored at −80 °C. The luciferase assay was performed using the Luc assay system from Promega. The gene product, luciferase enzyme, reacts with luciferase substrate, emitting light, which was detected using a luminometer (LUMIstar Galaxy BMG). Data for NF-κB inhibition are expressed as IC50 values (i.e., concentration required to inhibit TNFinduced NF-kB activity by 50%). The known NF-κB inhibitor TPCK was used as a positive control.

Nitric Oxide Assay

RAW 264.7 cells (1 × 104 cells/well) were seeded and incubated in 96-well culture plates at 37 °C, 5% CO2 in humidified air for 24 h. Then, complete medium was replaced with phenol red-free medium containing various concentrations of the test compounds, followed by LPS stimulation (1 μg/mL) for 20 h. The nitrite released in the culture media was reacted with Griess reagent, and the absorbance was measured at 540 nm. The amount of nitrite was calculated using a standard curve of known nitrite concentration versus absorbance at 540 nm. TPCK was used as a positive control. IC50 values were calculated using Table Curve 2D Windows V4.07 by AISN Software Inc44.

Computational details

All the quantum mechanical calculations were performed using Gaussian 0945. The conformational search was done using the MMFFaq force field (implemented in Spartan 08)46. Given the high conformational flexibility of this system, we used a cutoff energy of 5 kcal/mol, yielding an average of ~500, ~40, and ~400 different conformations per isomer in the cases of 1–3, 4 and 5, respectively. Next, each conformation was fully optimized at the PCM/B3LYP/6–31 G* level of theory in methanol as solvent using Gaussian 09, followed by frequency calculations at the same level to determine the nature of the stationary points and to compute the thermochemical properties (at 1.0 atm and 298.15 K). The most stable conformers (up to 1.5 kcal/mol from the global minima) were next subjected to NMR calculations. The magnetic shielding constants (σ) were computed using the gauge including atomic orbitals (GIAO) method47–50, the method of choice to solve the gauge origin problem16, 17, at the PCM/mPW1PW91/6-31 + G** level of theory. The calculations in solution were carried out using the polarizable continuum model, PCM[51], with methanol as the solvent). The unscaled chemical shifts (δu) were computed using TMS as reference standard according to δu = σ0 − σx, where σx is the Boltzmann averaged shielding tensor (over all significantly populated conformations) and σ0 is the shielding tensor of TMS computed at the same level of theory employed for σx. The Boltzmann averaging was done according to the eq. 1:

| 1 |

where σ i x is the shielding constant for nucleus x in conformer i, R is the molar gas constant (8.3145 J K−1 mol−1), T is the temperature (298 K), and Ei is the Gibbs free energy of conformer i (relative to the lowest energy conformer), obtained from the PCM/B3LYP/6-31 G* frequency calculations. The scaled chemical shifts (δs) were computed as δ s = (δ u − b)/m, where m and b are the slope and intercept, respectively, resulting from a linear regression calculation on a plot of δ u against δ exp. The DP4 calculations were carried out using the Applet from the Goodman group (at www-jmg.ch.cam.ac.uk/tools/nmr/DP4/). The DP4 + calculations were carried out using the Excel spreadsheet available for free at sarotti-nmr.weebly.com, or as part of the Supporting Information of the original paper23.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported mainly by start-up funding from the University of Hawaii Cancer Center, and grants from the Victoria S. and Bradley L. Geist Foundation (15ADVC-74420 and 17CON-86295) (to SC) and the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Cancer Institute (NCI) Grant CA161931 (JT). JGH acknowledges the receipt of funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH)/National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) Grant 5R01AT006732. We are grateful to Mr. Wesley Yoshida and Dr. Walter Niemczura at the Chemistry Department, University of Hawaii at Manoa for collecting the NMR data.

Author Contributions

Chunshun Li performed most of the experiments; Peng Huang did part of the experiments; Ariel M. Sarotti did the NMR calculation; James Turkson, Tamara P. Kondratyuk, Uyen T. Dang, and Julian Hurdle carried out the bioassays; John M. Pezzuto provided many useful suggestions about the bioassays, edited and polished the manuscript. Chunshun Li and Shugeng Cao designed the experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41598-017-10537-1

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Li CS, Yang BJ, Fenstemacher R, Turkson J, Cao S. Lycopodiellactone, an unusual γ-lactone-isochromanone from a Hawaiian plant-associated fungus Paraphaeosphaeria neglecta FT462. Tetrahedron Lett. 2015;56:1724–1727. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2015.02.076. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li CS, et al. A New Metabolite with a Unique 4-Pyranone-γ-Lactam-1,4-Thiazine Moiety from a Hawaiian-Plant Associated Fungus. Org. Lett. 2015;17:3556–3559. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b01650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maloney KN, et al. Phaeosphaeride A, an inhibitor of STAT3-dependent signaling isolated from an endophytic fungus. Org. Lett. 2006;8:4067–4070. doi: 10.1021/ol061556f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li CS, et al. Eremophilane sesquiterpenes from Hawaiian endophytic fungus Chaetoconis sp. FT087. Phytochem. 2016;126:41–46. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2016.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li CS, et al. Meroterpenoids with Antiproliferative Activity from a Hawaiian-Plant Associated Fungus Peyronellaea coffeae-arabicae FT238. Org. Lett. 2016;18:2335–2338. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b00685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li CS, Yang B, Turkson J, Cao S. Anti-proliferative ambuic acid derivatives from Hawaiian endophytic fungus Pestalotiopsis sp. FT172. Phytochem. 2017;140:62–72. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2017.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li CS, Sarotti AM, Turkson J, Cao S. Verbenanone, an octahydro-5H-chromen-5-one from a Hawaiian-Plant Associated Fungus FT431. Tetrahedron Lett. 2017;58:2290–2293. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2017.04.096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang P, Li CS, Sarotti AM, Turkson J, Cao S. Sphaerialactonam, a γ-lactam–isochromanone from the Hawaiian endophytic fungus Paraphaeosphaeria sp. FT462. Tetrahedron Lett. 2017;58:1330–1333. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2017.02.052. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fei-Zhang DJ, Li CS, Cao S. Hawaii natural compounds are promising to reduce ovarian cancer deaths. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2016;17:709–712. doi: 10.1080/15384047.2016.1178428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cao S, Ross L, Tamayo G, Clardy J. Asterogynins: secondary metabolites from a Costa Rican endophytic fungus. Org. Lett. 2010;12:4661–4663. doi: 10.1021/ol101972g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cao S, Clardy J. New naphthoquinones and a new δ-lactone produced by endophytic fungi from Costa Rica. Tetrahedron Lett. 2011;52:2206–2208. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2010.11.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cao S, et al. Inhibition of tumor cells interacting with stromal cells by xanthones isolated from a Costa Rican Penicillium sp. J. Nat. Prod. 2012;75:793–797. doi: 10.1021/np2009863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cao S, et al. Phenolic compounds as antiangiogenic CMG2 inhibitors from Costa Rican endophytic fungi. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2012;12:5885–5888. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.07.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mohammat MF, Mansor NS, Shaameri Z, Hamzah AS. Diastereoselective reduction of 2,3-Dioxo-4-carboxy-5-substituted pyrrolidines using NaBH4/AcOH and heterogenous hydrogenation reactions. J. Korean Chem. Soc. 2015;59:31–35. doi: 10.5012/jkcs.2015.59.1.31. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cao S, et al. Ipomoeassins A-E, cytotoxic macrocyclic glycoresins from the leaves of Ipomoea squamosa from the Suriname rainforest. J. Nat. Prod. 2005;68:487–492. doi: 10.1021/np049629w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lodewyk MW, Siebert MR, Tantillo DJ. Computational prediction of 1H and 13C chemical shifts: a useful tool for natural product, mechanistic, and synthetic organic chemistry. Chem. Rev. 2012;112:1839–1862. doi: 10.1021/cr200106v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grimblat N, Sarotti AM. You have full text access to this content Computational Chemistry to the Rescue: Modern Toolboxes for the Assignment of Complex Molecules by GIAO NMR Calculations. Chem. Eur. J. 2016;22:12246–12261. doi: 10.1002/chem.201601150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Novaes LFT, Sarotti AM, Pilli RA. Total Synthesis and Tentative Structural Elucidation of Cryptomoscatone E3: Interplay of Experimental and Computational Studies. J. Org. Chem. 2015;80:12027–12037. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.5b01956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grimblat N, Kaufman TS, Sarotti AM. Computational chemistry driven solution to rubriflordilactone B. Org. Lett. 2016;18:6420–6423. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b03318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karak M, Barbosa LCA, Acosta JAM, Sarotti AM, Boukouvalas J. Thermodynamically driven, syn-selective vinylogous aldol reaction of tetronamides. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2016;14:4897–4907. doi: 10.1039/C6OB00895J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sarotti AM, Suárez AG, Spanevello RA. DFT calculations induced a regiochemical outcome revision of the Diels–Alder reaction between levoglucosenone and isoprene. Tetrahedron Lett. 2011;52:3116–3119. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2011.04.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zanardi MM, Suárez AG, Sarotti AM. Determination of the relative configuration of terminal and spiroepoxides by computational methods. Advantages of the inclusion of unscaled data. J. Org. Chem. 2017;82:1873–1879. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.6b02129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grimblat N, Zanardi MM, Sarotti AM. Beyond DP4: an improved probability for the stereochemical assignment of isomeric compounds using quantum chemical calculations of NMR Shifts. J. Org. Chem. 2015;80:12526–12534. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.5b02396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zanardi MM, Sarotti AM. GIAO C–H COSY simulations merged with artificial neural networks pattern recognition analysis. Pushing the structural validation a step forward. J. Org. Chem. 2015;80:9371–9378. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.5b01663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith SG, Goodman JM. Assigning stereochemistry to single diastereoisomers by GIAO NMR calculation: the DP4 probability. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:12946–12959. doi: 10.1021/ja105035r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith SG, Goodman JM. Assigning the stereochemistry of pairs of diastereoisomers using GIAO NMR shift calculation. J. Org. Chem. 2009;74:4597–4607. doi: 10.1021/jo900408d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bahrami K, Khodaei MM, Yousefi BH, Arabi MS. TMSCl-promoted selective oxidation of sulfides to sulfoxides with hydrogen peroxide. Tetrahedron Lett. 2010;51:6939–6941. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2010.10.171. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsuda M, et al. Modiolides A and B, two new 10-membered macrolides from a marine-derived fungus. J. Nat. Prod. 2003;66:412–415. doi: 10.1021/np0203943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wijeratne EMK, et al. Isolation, optimization of production and structure-activity relationship studies of monocillin I, the cytotoxic constituent of Paraphaeosphaeria quadriseptata. J. Antibiotics. 2004;57:541–546. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.57.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ge HM, et al. Paranolin: a new xanthene-based metabolite from Paraphaeosphaeria nolinae Hel. Chim. Acta. 2006;89:502–506. doi: 10.1002/hlca.200690051. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wijeratne EMK, Paranagama PA, Gunatilaka AAL. Five new isocoumarins from Sonoran desert plant-associated fungal strains Paraphaeosphaeria quadriseptata and Chaetomium chiversii. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:8439–8446. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2006.06.089. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seo C, et al. Hexaketides from phytopathogenic fungus Paraphaeosphaeria recurvifoliae. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2007;28:1803–1806. doi: 10.5012/bkcs.2007.28.10.1803. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee HB, Oh H. Two new fungal metabolites from an endophytic fungus Paraphaeosphaeria. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2006;27:779–782. doi: 10.1007/BF02705927. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shao MW, Kong LC, Jiang DH, Zhang YL. Phytotoxic and antimicrobial metabolites from Paraphaeosphaeria sp. QTYC11 isolated from the gut of Pantala flavescens larvae. Records Nat. Prod. 2016;10:326–331. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Suga T, et al. Paraphaeosphaeride D and berkleasmin F, new circumventors of arbekacin resistance in MRSA, produced by Paraphaeosphaeria sp. TR-022. J. Antibiotics. 2016;69:605–610. doi: 10.1038/ja.2016.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ding LJ, et al. Oryzamides A-E, cyclodepsipeptides from the sponge-derived fungus Nigrospora oryzae PF18. J. Nat. Prod. 2016;79:2045–2052. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.6b00349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.de Castro MV, et al. Condensation of macrocyclic polyketides produced by Penicillium sp. DRF2 with mercaptopyruvate represents a new fungal detoxification pathway. J. Nat. Prod. 2016;79:1668–1678. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.6b00295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Delazar A, et al. Iridoid glycosides from Eremostachys glabra. J. Nat. Prod. 2004;67:1584–1587. doi: 10.1021/np040044b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sridhar C, Subbaraju GV, Venkateswarlu Y, Venugopal RT. New acylated iridoid glucosides from Vitex altissima. J. Nat. Prod. 2004;67:2012–2016. doi: 10.1021/np040117r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee RE, et al. Spectinamides: a new class of semisynthetic antituberculosis agents that overcome native drug efflux. Nat. Med. Í. 2014;20:152–158. doi: 10.1038/nm.3458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Susceptibility testing of mycobacteria, Nocardiae, and other aerobic Actinomycetes: approved standard. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI), Wayne, PA, U.S., Vol. 23, M24-A (2003). [PubMed]

- 42.Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically: approved standard, 7th ed.; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI), Wayne, PA, U.S. Vol. 26, M7–A7 (2006).

- 43.Kondratyuk TP, et al. Mar. Drugs. 2012;10:451–464. doi: 10.3390/md10020451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Park, E.-J. et al. Induction of retinoid X receptor activity and consequent upregulation of p21WAF1/CIP1 by indenoisoquinolines in MCF7 cells. Cancer Prev. Res. (Phila.) 4, 592–607 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Frisch, M. J. et al. Gaussian 09, Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, 2009.

- 46.Ditchfield R. Molecular Orbital Theory of Magnetic Shielding and Magnetic Susceptibility. J. Chem. Phys. 1972;56:5688–5691. doi: 10.1063/1.1677088. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ditchfield R. Self-consistent perturbation theory of diamagnetism. Mol. Phys. 1974;27:789–807. doi: 10.1080/00268977400100711. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rohlfing CM, Allen LC, Ditchfield R. Proton and carbon-13 chemical shifts: Comparison between theory and experiment. Chem. Phys. 1984;87:9–15. doi: 10.1016/0301-0104(84)85133-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wolinski K, Hinton JF, Pulay P. Efficient implementation of the gauge-independent atomic orbital method for NMR chemical shift calculations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990;112:8251–8260. doi: 10.1021/ja00179a005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wolinski, K., Hinton, J. F. & Pulay, P. Efficient implementation of the gauge-independent atomic orbital method for NMR chemical shift calculations. J. Am. Chem. Soc.112, 8251–8260 (1990).

- 51.For a review on continuum solvation models, see: Tomasi, J., Mennucci, B., Cammi, R. Quantum mechanical continuum solvation models. Chem. Rev.105, 2999–3094 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.