Abstract

The aim of the study was to evaluate the effectiveness of delivering a contemporary peer-led falls prevention education presentation on community-dwelling older adults’ beliefs, knowledge, motivation and intention to engage in falls prevention strategies. A two-group quasi-experimental pre-test–post-test study using a convenience sample was conducted. A new falls prevention training package for peer educators was developed, drawing on contemporary adult learning and behaviour change principles. A 1-h presentation was delivered to community-dwelling older adults by peer educators trained with the new package (intervention group). Control group participants received an existing, 1-h falls prevention presentation by trained peer educators who had not received the adult learning and behaviour change training. Participants in both groups completed a purpose-developed questionnaire at pre-presentation, immediately post-presentation and at one-month follow-up. Participants’ levels of beliefs, knowledge, motivation and intention were compared across these three points of time. Generalised estimating equations models examined associations in the quantitative data, while deductive content analysis was used for qualitative data. Participants (control n = 99; intervention n = 133) in both groups showed significantly increased levels of beliefs and knowledge about falls prevention, and intention to engage in falls prevention strategies over time compared to baseline. The intervention group was significantly more likely to report a clear action plan to undertake falls prevention strategies compared to the control group. Peer-led falls prevention education is an effective approach for raising older adults’ beliefs, knowledge and intention to engage in falls prevention strategies.

Keywords: Accidental falls, Peer group, Health education, Health promotion

Introduction

Falls amongst older adults are a serious health and socio-economic problem (Peel 2011). The direct cost of falls-related hospitalisations in Australia was estimated to be over $648 million in 2007–2008 (AIHW: Bradley 2012). There is strong evidence that interventions including strength and balance exercise, cataract surgery, medication review and multifactorial strategies can reduce falls (Deandrea et al. 2010; Gillespie et al. 2012). However, older adults have been found to have low levels of uptake and engagement in falls prevention strategies, suggesting that there is a gap in translating these research findings into practice (Nyman and Victor 2012; Yardley et al. 2006, 2007).

Qualitative research findings demonstrate that many older adults possess low levels of knowledge, and believe that falls prevention is not personally relevant to them or have low motivation to engage in falls prevention strategies (Dickinson et al. 2011; Haines et al. 2014; Hill et al. 2011). Concepts of health behaviour change suggest that providing people with knowledge and motivation is critical for achieving health behaviour change. Studies that have provided older adults in hospitals with individualised level falls prevention education interventions have demonstrated positive changes in behaviour (Haines et al. 2011; Hill et al. 2013, 2015; Michie et al. 2011). However, there has been limited translation of this educational approach into the community setting.

One review has proposed peer education as a potentially valuable approach that could influence health-related behaviour amongst peer participants (Peel and Warburton 2009). Peer education encompasses a range of learning approaches where information, skills and values are conveyed amongst people who share common characteristics such as age or shared experience (Simoni et al. 2011). A peer educator deemed as a credible source and positive role model can play a pivotal role in promoting self-confidence and influencing health-related behaviour amongst their peer participants (Peel and Warburton 2009). Evidence from a systematic review of 17 studies (7442 people) using peer education found that providing peer education resulted in positive health behaviour outcomes for the recipients (Foster et al. 2007).

There is limited empirical research investigating the impact of peer education in the area of falls prevention, especially where an older individual peer delivers a presentation to a group of other older adults. A large systematic review of falls prevention studies in the community setting (159 trials) included only four studies that evaluated education interventions and only one of these was a peer intervention study. The review found that evidence for education interventions was inconclusive (Gillespie et al. 2012). Previous findings suggest that there is uncertainty about the efficacy of peer-led falls prevention education as facilitated by presentation, lecture or discussion (Allen 2004; Deery et al. 2000; Kempton et al. 2000). The limitations of these studies included not describing the content of the intervention clearly and not describing pedagogical and underlying theory that had guided the design and implementation of the interventions. Researchers recommended that studies that evaluate behavioural interventions should define the framework chosen to design the intervention and include description of the content and mode of delivery, but importantly also describe the active components of the intervention that are intended to facilitate behaviour change and the behaviour change techniques used (Abraham and Michie 2008; Michie and Johnston 2012). Use of theories to inform health behavioural change interventions has been advocated because it provides a matrix of enablers, barriers and mechanisms to explain and predict health behaviour (Improved Clinical Effectiveness through Behavioural Research Group (ICEBeRG) 2006). Therefore, provision of a peer-led presentation should ideally be underpinned by adult learning principles (Merriam and Bierema 2014) and behavioural change framework such as the behaviour change wheel theory (Michie et al. 2011). This may improve beliefs, knowledge, motivation and intention which could facilitate behaviour change, namely the uptake of falls prevention strategies by older adults.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of delivering a peer-led falls prevention presentation on community-dwelling older adults’ beliefs and knowledge about falls prevention, and their motivation and intention to engage in falls prevention strategies. The study compared the effect of delivering a contemporary presentation by an individual older adult to a group incorporating adult learning principles and behaviour change strategies against delivering an existing peer-led falls prevention presentation that did not incorporate these principles or behaviour change strategies.

Method

Study design

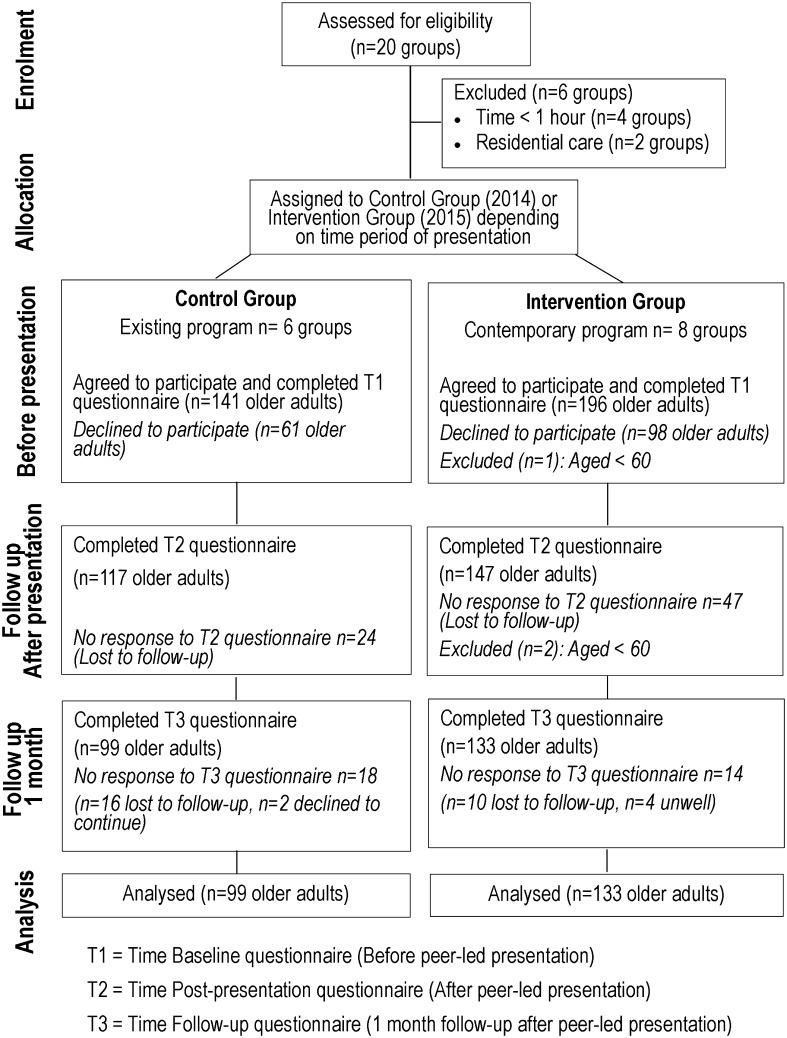

A two-group quasi-experimental pre-test–post-test study design using a convenience sample was conducted. At the initial control group stage (Phase 1), participants received the existing peer-led presentation. In the subsequent intervention group stage (Phase 2), participants received the new contemporary peer-led presentation (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the recruitment of participants and data collection process for the study

Ethics

The study was approved by the University of Notre Dame Australia’s Human Research Ethics Committee (Reference 014134F and 015013F). All participants provided written informed consent.

Participants and setting

Participants were community-dwelling older adults who were attending a peer-led falls prevention presentation. Inclusion criteria for both control and intervention groups consisted of being aged 60 years or older, attending a peer-led falls prevention presentation during the study phases and being able to complete a questionnaire. Older adults who resided in residential care facilities or were hospitalised were excluded.

The presentations were organised by a large not-for-profit community organisation that promoted injury prevention and community safety in Western Australia. The community engagement officer from the community organisation was a qualified health promotion professional, who managed their peer-led education programmes. The community engagement officer was the key person who recruited and trained new volunteer older adult peer educators to present and deliver the peer-led falls prevention education programme, which aimed to raise awareness of falls prevention amongst community-dwelling older adults. These peer educators’ ages ranged from 65 to 85 years and most were retired and possessed diverse working experience before retirement.

Recruitment

A convenience sample was recruited for both the control and intervention phases of the trial.

Peer-led presentations were organised by the community engagement officer who advertised the falls prevention presentation to existing older adult social groups in Western Australia, retirement village associations and other seniors’ networks through mailed flyers or newsletters five months prior to conducting each phase of the study. The community engagement officer was the organisation’s contact person for these groups and played an active role in the scheduling of the falls prevention presentations to each group, as well as providing support for the programme.

Control conditions

The control conditions consisted of participants receiving the existing peer-led presentation during Phase 1 (2014). This was a 1-h presentation delivered by five volunteer peer educators that has been delivered regularly for approximately 10 years. The existing peer-led falls prevention presentation consisted of the peer educators sharing falls-related content knowledge such as risk factors for falls and strategies for reducing risk of falls, including managing one’s medications, improving balance by undertaking exercises, checking feet and footwear and completing environmental modifications (Deandrea et al. 2010; Gillespie et al. 2012). The training for these volunteer peer educators, conducted by the community engagement officer, consisted of a 5-h session which provided them with this information (Table 1). The content was regularly reviewed by the organisation and focused on providing the best available strategies that could be used by older adults to reduce their falls risk. However, the training did not include information about the principles of adult learning and health behaviour change. Peer educators were also provided falls prevention support materials such as a videotape, booklet and flyers to use during presentations, to aid in conveying the falls prevention message to the community groups of older adults. These existing peer educators were experienced presenters all aged over 60 years who had delivered the presentations for between two and ten years. The training for both existing and new peer educators delivering the presentations to the control and intervention groups is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Training sessions undertaken to prepare peer educators of existing and contemporary programmes to deliver peer-led falls prevention education presentations

| Training sessions for peer educators | Existing programmea | Contemporary programmeb |

|---|---|---|

| Training session (5 h): conducted by community engagement officer | ✓ | ✓ |

| Learning objectives: introduction to epidemiology of falls-related content knowledge, e.g. falls information including incidence of falls in the community, risk factors for falling, evidence-based falls prevention strategiesc | ✓ | ✓ |

| Training activity provided: demonstration and lecture | ✓ | ✓ |

| Activity supporting material: lecture notes | ✓ | ✓ |

| Peer-led falls prevention presentation support material: video, booklet and flyers | ✓ | ✓ |

| Additional training session (4 h): conducted by research team | ✗ | ✓ |

| Learning objectives: develop an awareness of learning styles; describe basic principles of adult learning and apply them in delivering falls prevention presentations; identify and integrate relevant behaviour change techniques into falls prevention presentationsd | ✗ | ✓ |

| Training activity provided: learning style questionnaire, online video links, discussion, group work and interaction, and mock presentation practice | ✗ | ✓ |

| Activity supporting material: peer educator guidebook and online training video; programme fidelitye checklist; self-reflection guide | ✗ | ✓ |

aPeer educators were trained and already had two to ten years of experience delivering the existing peer-led falls prevention education preceding the research period

bNewly recruited volunteer peer educators who were trained to deliver the contemporary peer-led falls prevention education

cDeandrea et al. (2010) and Gillespie et al. (2012)

dAbraham and Michie (2008), Anderson et al. (2001), Fleming (2008) and Merriam and Bierema (2014)

eBellg et al. (2004)

Intervention

A contemporary falls prevention peer-led education programme was designed by the research team to be used in Phase 2 (2015). The programme consisted of providing training and resources for new volunteer peer educators to also deliver a 1-h peer-led falls prevention presentation to groups of community-dwelling older adults. The aim of the presentation was to improve the older community-dwelling adults (1) self-belief that taking measures to reduce their risk of falls would be useful, (2) knowledge about falls and falls prevention strategies and (3) motivation and intention to engage in falls prevention strategies.

The development and implementation of the presentation was informed by previous studies conducted by the present authors, whereby key stakeholders were consulted, including community-dwelling older adults (Khong et al. 2016) and experts in the area of education and falls prevention. Feedback was also sought from the peer educators who were delivering the existing presentations (Khong et al. 2015). The design and implementation of the contemporary presentation was based on the framework of the behaviour change wheel theory (Michie et al. 2011) and was also informed by educational and adult learning principles (Anderson et al. 2001; Merriam and Bierema 2014).

Six new volunteer peer educators were recruited via daily advertisements run on a community radio whose target audience was older adults. These six volunteers completed their training but only two were available to deliver the presentation during the intervention phase of the trial. The first day (5 h) of the peer educator training was conducted by the community engagement officer who imparted falls-related content knowledge such as the definition of a fall, statistics about the nature and incidence of falls in the community, and the risk factors contributing to falls (Table 1). This training session was identical to the one provided to those peer educators who were delivering the existing presentations to the control groups. The new peer educators were also provided with the same falls prevention support materials (a videotape, booklet and flyers) to deliver their presentations to the intervention groups. Subsequently, an additional 4-h training session was conducted by the researchers for the new peer educators using purpose-developed education resources. These resources consisted of a facilitator–trainer guide and instructional aids, a training video and a peer educator guidebook, including a programme fidelity checklist (Bellg et al. 2004). Principles of adult learning, behaviour change techniques (such as goal setting) and pedagogical skills, including suggestions on how to conduct an interactive presentation, were shared with the new peer educators (Table 1) (Abraham and Michie 2008; Anderson et al. 2001; Fleming 2008; Merriam and Bierema 2014). Peer educators were trained to establish themselves as a credible source of information when they delivered a presentation and were encouraged to share personal insights regarding falls prevention to engage and foster their peers’ learning and self-confidence. Each new peer educator was provided with a guidebook consisting of information imparted during the training session. A training video with prompts involving an experienced university educator was created. This video modelled the contemporary falls prevention presentation to a live audience. Subsequently, the video was developed as an online resource for training new peer educators.

Following the training, each new peer educator conducted an initial falls prevention presentation with support from the organisation and a fellow peer educator. After delivering a presentation, the peer educator completed the programme fidelity checklist (Bellg et al. 2004), which was used as a guide for self-reflection and feedback and to promote adherence to the intervention delivery.

Data collection and procedure

Data collection followed the same procedure during both phases of the trial. The peer educator arrived at the local community group when a presentation was organised. Prior to the delivery of the presentation, the older adults who attended were invited to participate in the trial and those who provided written consent were recruited. Each participant completed a purpose-developed questionnaire prior to the peer educator delivering the falls prevention presentation and following the presentation. The follow-up questionnaire was mailed out to each participant 1 month after the presentation.

The design of the questionnaire items was based on other studies that designed questionnaires specifically to evaluate behaviour change or evaluated behaviour change regarding falls prevention (Cane et al. 2012; Hill et al. 2009; Huijg et al. 2014). The overall design of the questionnaire was based on the framework of behaviour change wheel theory (Michie et al. 2011), namely capability (awareness and knowledge), opportunity and motivation (Michie et al. 2011). There were seven closed items (see Table 3) which were rated on a five-point Likert scale (Strongly Agree, Agree, Neutral, Disagree, Strongly Disagree). The final open-ended item (item 8) asked each participant to list up to three measures that they could take in the next month which would help them avoid falling or reduce their risk of falling (Table 5). The post-presentation and one-month follow-up questionnaires were modified slightly in terms of wording of the questionnaire items, so that the wording was in the context of having attended the peer educators’ presentation. At the one-month follow-up, telephone calls were made to each participant to advise them to expect a questionnaire, which was subsequently mailed out with a prepaid envelope. A single mail or telephone call was made to remind those who did not respond within two weeks of the deadline to return the questionnaire.

Table 3.

Participants’ responses at baseline, post-presentation and at one-month follow-up

| Item | Control group (n = 99) | Intervention group (n = 133) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time 1 | Time 2 | Time 3 | Time 1 | Time 2 | Time 3 | |

| Mdn a (IQR) | Mdn a (IQR) | Mdn a (IQR) | Mdn a (IQR) | Mdn a (IQR) | Mdn a (IQR) | |

| 1. For me, taking measures to reduce my risk of falling would be useful | 4.5 (0.66) | 4.6 (0.62) | 4.8 (0.41) | 4.4 (0.62) | 4.6 (0.56) | 4.7 (0.48) |

| 2. Most people whose opinion I value approve of me taking measures to reduce my risk of falling | 4.4 (0.71) | 4.6 (0.6) | 4.6 (0.62) | 4.4 (0.66) | 4.5 (0.61) | 4.5 (0.56) |

| 3. I am aware of the measures needed to reduce my risk of falling | 4.2 (0.77) | 4.6 (0.53) | 4.6 (0.53) | 4.1 (0.79) | 4.5 (0.53) | 4.6 (0.53) |

| 4. I feel positive about reducing my overall risk of falling | 4.3 (0.74) | 4.5 (0.58) | 4.5 (0.56) | 4.3 (0.67) | 4.5 (0.61) | 4.5 (0.55) |

| 5. I am confident that if I wanted to, I could reduce my risk of falling | 4.1 (0.74) | 4.4 (0.66) | 4.4 (0.55) | 4.2 (0.74) | 4.4 (0.68) | 4.4 (0.6) |

| 6. In the next month, I intend to take measures to reduce falls or my risk of falling | 4.2 (0.86) | 4.4 (0.69) | 4.3 (0.69) | 4.1 (0.8) | 4.5 (0.68) | 4.3 (0.72) |

| 7. I have a clear plan of how I will take measures to reduce falls or my risk of falling | 3.8 (0.9) | 4.3 (0.77) | 4.2 (0.86) | 3.9 (0.9) | 4.3 (0.79) | 4.3 (0.71) |

Note: Responses to the final open-ended item (item 8) “List up to 3 ways (measures) that you could take in the next month, which will help you avoid falling or the risk of falling” are reflected in Table 5

Mdn median, IQR inter quartile range

aScore 5—Strongly Agree; 4—Agree; 3—Undecided; 2— Disagree; 1—Strongly Disagree

Time 1: baseline (before peer-led presentation); Time 2: post-presentation (after peer-led presentation); Time 3: one-month follow-up (1-month follow-up)

Table 5.

Participants’ knowledge of falls prevention strategies as evidenced by the measures identified in their plan

| Generic category | Sub-category | Control | Intervention | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline n = 197a (100%) |

Follow-up n = 217a (100%) |

Baseline n = 266a (100%) |

Follow-up n = 291a (100%) |

||

| Non-evidenced strategies | 23 (12) | 25 (12) | 48 (18) | 19 (7) | |

| No strategies | 19 (10) | 9 (4) | 32 (12) | 14 (5) | |

| Evidence-based strategies | Balance and mobilityb | 48 (23) | 46 (21) | 18 (7) | 47 (16) |

| Environmental aids | 25 (13) | 25 (11) | 21 (8) | 39 (13) | |

| Environmental modification | 39 (20) | 67 (30) | 88 (33) | 90 (31) | |

| Exercises | 28 (14) | 17 (8) | 25 (9) | 34 (12) | |

| Feet and footwear | 9 (5) | 23(11) | 25 (9) | 31 (11) | |

| Medication | 4 (2) | 4 (2) | 7 (3) | 10 (3) | |

| Vision | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | 7 (2) | |

aParticipants had the opportunity to provide more than one measure in their comments

bBalance and mobility included participants’ knowledge about posture, balance and gait but excluded exercises

The first seven questionnaire items are shown in Table 3. The four outcomes measured using the questionnaire were: (i) beliefs about falling and falls prevention (measured using items 1 and 2), (ii) levels of knowledge about falls prevention (measured using items 3 and 5), (iii) motivation to reduce risk of falling by engaging in falls prevention strategies (measured using item 4) and (iv) intention and a plan to undertake falls prevention strategies (measured using items 6 and 7). The final item (8) is a question that aimed to understand the participants’ knowledge, intention and plan to undertake falls prevention strategies, as shown in Table 5.

Other information collected at baseline was participants’ sociodemographic characteristics, including age, gender, socio-economic index (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2013), self-rated health, number of prescribed medications taken per day, history of falls in the past 12 months and level of mobility.

Prior to the commencement of the main trial, a convenience sample of community-dwelling older adults who attended social walking groups was enrolled to evaluate the test–retest reliability of the questionnaire. Subsequently, the questionnaire was pilot-tested with older adults from two other social groups completing the questionnaires across three points of time, after which slight changes were made to the format of the questionnaire and to the instructions given for completing it in order to clarify the procedure for participants.

Data analysis

Baseline characteristics of the two groups’ participants were compared using t test for continuous data, and Pearson’s Chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests were used for comparison of categorical data. The test–retest reliability of the questionnaire was established using intraclass correlation (ICC) and Cohen’s kappa coefficient (kappa). A p-value <.05 was considered significant for all analyses.

Participants’ responses to the seven closed items (dependent variables) measuring beliefs, knowledge, motivation and intention outcomes were compared within and between the intervention and control groups using generalised estimating equation (GEE) modelling (Liang and Zeger 1986). The GEE approach was considered appropriate because it was able to account for correlations amongst the participants’ outcomes and was able to include more than one covariate (either continuous or categorical) (Liang and Zeger 1986; Williamson et al. 1996). The independent variables were participants’ sociodemographic information. Final GEE models included only significant independent variables (p < .05). Results were reported using odds ratios (OR) with accompanying 95% confidence intervals and p-values. Quantitative data were analysed using statistical package SPSS® (Statistical Package for Social Sciences, version 22 for Windows).

Qualitative data obtained from both groups’ open-ended responses (item 8 in the questionnaire) were transcribed verbatim and exported to NVivo 10 for Windows (QSR International Pty Ltd 2012). These data were analysed using deductive content analysis, which is based on using previous knowledge around the research topic (Elo and Kyngas 2008). A categorisation matrix was constructed using Australian recommendations for falls prevention for community-dwelling older people (Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare 2009) and systematic reviews which summarised the evidence for falls prevention strategies for community-dwelling older people (Deandrea et al. 2010; Gillespie et al. 2012). The main category was participants’ knowledge about falls prevention as evidenced by the measures identified in their plan (see Table 5). The primary researcher read through transcripts to gain a sense of the content. Participants’ responses about their falls prevention measures were coded by theme and assigned according to the predetermined categories within the matrix. New categories were generated for responses that could not be categorised within the matrix. Two researchers discussed the data but identified their corresponding generic and sub-categories independently. Frequency counts were also undertaken of each category or sub-category. Final findings of the two independent researchers were compared and triangulated to enhance trustworthiness of the findings.

Sample size

For conducting the test–retest reliability, for an estimated reliability index of 80%, with an alpha level of 5% and power of 80%, a minimum sample of 46 participants were required (Walter et al. 1998). Regarding sample size for the main trial, as previous trials in this area had not been conducted, a minimum number of 100 participants were chosen for the control group to gain sufficient data to calculate the sample size for the subsequent Phase 2. The control phase of the study used data from participants (pre- and post-presentation measurements for each participant) and measured differences over time. These data from the control group indicated that when examining the mean differences of each of the seven items, the minimum difference in the responses from the participants from pre- to post-presentation was normally distributed with a standard deviation of 0.44. If the true difference in the mean response was 0.155, then 65 participants (with paired pre- and post-presentation data) needed to be enrolled in the intervention group to be able to reject the null hypothesis that this response difference was zero with probability (power) 0.8. The type I error probability associated with this test of this null hypothesis was 0.05. Since in the control group trial there was a dropout rate of 17% between baseline and one-month follow-up, the aim was to enrol at least 80 participants for Phase 2 of the study.

Results

The content and face validity of the questionnaire was evaluated by health professionals and community-dwelling older adults and the questionnaire was revised based on their feedback. The final questionnaire was pre-tested with 16 older adults. Forty-nine older adults (aged 60 and over) subsequently participated in the test–retest reliability trial of the questionnaire. There was moderate to substantial agreement across items (Kappa = .585–.765) (Landis and Koch 1977). On further analysis, compared to the rest of the items, the kappa for questionnaire item 5 assessing “I am confident that if I wanted to, I could reduce my risk of falling” was the lowest at 0.585 (moderate agreement). Percentage agreement ranged from 73.5 to 87.8% and the ICC for the participants’ mean score of outcome measures between retest occasions was 0.88, which was considered a good level of agreement (Portney and Watkins 2009).

There were n = 141 participants who enrolled and of those n = 99 participants (70%) completed Phase 1 (control) of the trial. For the intervention trial, n = 196 enrolled and n = 133 participants (67%) completed Phase 2 (intervention). The flow of participants through the study is shown in Fig. 1. The main reasons for not providing any response to the post-presentation or follow-up questionnaire included participants needing to leave the presentation venue prior to the post-presentation questionnaire being administered, being unwell, away on holiday or unable to be contacted at the one-month follow-up. Participants were excluded from the analysis if they did not complete the questionnaire after the presentation or at the one-month follow-up. There were no significant differences in the demographic characteristics between participants who dropped out compared to participants who completed the follow-up questionnaire.

Participant characteristics from both groups are presented in Table 2. Intervention group participants were significantly more likely to be male (p = 0.006) and come from higher socio-economic areas (p = 0.002).

Table 2.

Participants’ baseline characteristics

| Characteristic | Control n = 99 |

Intervention n = 133 |

Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), M (SD) | 77.9 (6.9) | 79.2 (7.0) | .142b |

| Number of prescribed medication taken per day, Mdn (IQR) | 4.0 (5.0) | 4.0 (5.5) | .606b |

| Number of people who had fallen in the past 12 months, n (%) | 40 (40.4) | 45 (33.8) | .304a |

| Gender, n (%) | .006a* | ||

| Female | 71 (71.7) | 72 (54.1) | |

| Socio-economic area, n (%) | .002a* | ||

| Higher | 59 (59.6) | 104 (78.2) | |

| Self-rated health, n (%) | .261a | ||

| Poor/fair | 25 (25.3) | 22 (16.5) | |

| Good | 52 (52.5) | 79 (59.4) | |

| Very good | 22 (22.2) | 32 (24.1) | |

| Self-rated difficulty with walking, n (%) | .115a | ||

| No | 61 (61.6) | 95 (71.4) | |

| Use of walking aid inside of house, n (%) | .182c | ||

| Nil aids | 83 (83.8) | 122 (91.7) | |

| Walking stick | 11 (11.1) | 8 (6.0) | |

| Walking frame | 5 (5.1) | 3 (2.3) | |

| Use of walking aid outside of house, n (%) | .612a | ||

| Nil aids | 72 (72.7) | 104 (78.2) | |

| Walking stick | 15 (15.2) | 17 (12.8) | |

| Walking frame | 12 (12.1) | 12 (9.0) | |

| Ambulatory distance without rest on level ground, n (%) | .182a | ||

| <400 m | 21 (21.2) | 17 (12.8) | |

| 400–800 m | 23 (23.2) | 35 (26.3) | |

| 801 m–1.6 km | 13 (13.1) | 29 (21.8) | |

| 1.7–3.2 km | 15 (15.2) | 24 (18.0) | |

| 3.3 km or more | 27 (27.3) | 28 (21.1) | |

| Previously discussed issue of falls with health professional/doctor or received falls prevention information from them? n (%) | .232a | ||

| Yes | 34 (34.3) | 36 (27.1) |

M mean, SD standard deviation, Mdn median, IQR inter quartile range

aDetermined by using Chi-square test

bDetermined by using t test

cDetermined by using Fisher’s exact test

* Significant at p < .05

Participants’ levels of beliefs, knowledge about falls and falls prevention, motivation and intention to reduce their risk of falling at baseline and after the presentations are presented in Table 3. Participants in both control and intervention groups showed increased levels of self-perceived knowledge, increased self-belief that falls prevention would be useful and increased levels of motivation to prevent falls at post-presentation and at one-month follow-up. Participants in both groups also reported higher levels of intention (control median 4.4, intervention median 4.5) and clear plans (control median 4.3, intervention median 4.3) in falls prevention strategies following the presentations.

For the GEE modelling (Table 4), the Likert scores of the seven items were found to be bimodal and therefore were recoded into a dichotomised variable. Rating of “Strongly Agree” and “Agree” were recoded to “Agree” or 1 and “Neutral”, “Disagree” and “Strongly Disagree” were recoded to “Disagree” or 0. Participants within both the control and intervention groups demonstrated significantly increased levels of beliefs that falls prevention measures would be useful and that knowledge about falls prevention strategies increased intention to take measures to prevent falls. Both groups also reported a clear action plan to engage in falls prevention strategies at post-presentation or at one-month follow-up (Table 4) compared to baseline. Despite participants’ improved levels of motivation to reduce their risk of falling across the three points of time within both the control and intervention group, there was no significant between-group difference when investigated in the GEE modelling. Multivariate analysis demonstrated that the intervention group was significantly more likely to report that they had developed a clear action plan which they intended to implement to reduce their risk of falling compared to the control group [OR = 1.69, 95% CI (1.03–2.78)], but there were no significant differences between groups regarding beliefs and knowledge about falls prevention, and levels of intention to engage in falls prevention strategies.

Table 4.

Final GEE models and parameter estimates for each behaviour change outcome

| Model | Variable | Reference group | Exp(B) OR | Robust 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Belief that taking measures to reduce risk of falling would be useful | Time 3 | Time 1 | 12.06 | 1.86, 78.06 | .009* |

| Time 2 | Time 1 | 2.33 | 1.05, 5.16 | .038* | |

| Intervention | Control | 1.07 | 0.28, 4.02 | .922 | |

| Female | Male | 3.99 | 1.08, 14.68 | .038* | |

| 2. Belief that people whose opinion they value would approve of them taking measures to reduce their risk of falling | Time 3 | Time 1 | 2.17 | 1.15, 4.08 | .017* |

| Time 2 | Time 1 | 2.17 | 1.22, 3.85 | .009* | |

| Intervention | Control | 1.50 | 0.62, 3.61 | .365 | |

| 3. Knowledge of the measures needed to reduce their risk of falling | Time 3 | Time 1 | 9.60 | 3.68, 25.03 | .001* |

| Time 2 | Time 1 | 9.60 | 3.65, 25.24 | .001* | |

| Intervention | Control | 0.98 | 0.41, 2.33 | .962 | |

| Female | Male | 2.34 | 1.09, 5.13 | .030* | |

| Discussed: yesa | No | 3.07 | 1.09, 8.66 | .034* | |

| 4. Motivation: positive attitude about reducing their overall risk of falling | Time 3 | Time 1 | 1.70 | 0.69, 4.23 | .252 |

| Time 2 | Time 1 | 1.70 | 0.68, 4.24 | .252 | |

| Intervention | Control | 1.29 | 0.38, 4.38 | .688 | |

| 5. Knowledge in their confidence to reduce their risk of falling | Time 3 | Time 1 | 3.48 | 1.74, 6.97 | .001* |

| Time 2 | Time 1 | 1.85 | 1.17, 2.94 | .009* | |

| Intervention | Control | 1.01 | 0.53, 1.93 | .984 | |

| Aids inside house: nil | Walking frame | 4.15 | 1.33, 12.89 | .014* | |

| 6. Intention to take measures to reduce their risk of falling | Time 3 | Time 1 | 1.46 | 0.90, 2.35 | .122 |

| Time 2 | Time 1 | 2.18 | 1.33, 3.56 | .002* | |

| Intervention | Control | 1.13 | 0.62, 2.04 | .697 | |

| Female | Male | 1.82 | 1.02, 3.27 | .043* | |

| Walking stick | Nil aids | 5.20 | 1.56, 17.3 | .007* | |

| 7. A clear plan of the measures to reduce falls or risk of falling | Time 3 | Time 1 | 3.17 | 2.08, 4.84 | .001* |

| Time 2 | Time 1 | 3.43 | 2.27, 5.18 | .001* | |

| Intervention | Control | 1.69 | 1.03, 2.78 | .037* | |

| Female | Male | 2.47 | 1.51, 4.02 | .001* | |

| Discussed: Yesa | No | 2.12 | 1.19, 3.78 | .011* |

OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval, Exp exponential, GEE generalised estimating equation

Time 1: baseline questionnaire (before peer-led presentation)

Time 2: time post-presentation questionnaire (after peer-led presentation)

Time 3: time follow-up questionnaire (1-month follow-up)

OR and 95% CI rounded to two decimal places

* Statistically significant difference between groups

a Previously discussed falls prevention with health professional/doctor or received information

Female participants in both groups were significantly more likely to believe that taking measures to prevent falls was useful [OR = 3.99, 95% CI (1.08–14.68)]; to report increased levels of knowledge about falls prevention after the presentation [OR = 2.34, 95% CI (1.09–5.13)]; to report increased intention to take measures to prevent falls [OR = 1.82, 95%CI (1.02–3.270]; and to report a clear action plan to reduce their risk of falling [OR = 2.47, 95% CI (1.51–4.02)] (Table 4). Participants who reported that they had previously discussed falls prevention with their doctor or health professional or received falls prevention information were significantly more likely to report an increased knowledge of falls risk [OR = 3.07, 95% CI (1.09–8.66)] and to develop a falls prevention action plan [OR = 2.12, 95% CI (1.19–3.78)].

Deductive content analysis of the written responses of both control and intervention groups’ participants to the open-ended item (item 8) is displayed in Table 5. Participants identified measures that they considered they could take that would help reduce their risk of falling, which were coded into three generic categories: (1) evidence-based strategies of which there were seven sub-categories, (2) non-evidenced strategies and (3) no strategies. The latter two categories were new categories generated from data that did not fit into the predetermined categories. Table 5 shows the measures that participants identified as being helpful for reducing their risk of falling. Summative responses from both control and intervention groups’ participants within each generic and sub-category are summarised in Table 5.

Knowledge about environmental modification measures was the largest sub-category represented, which included comments about adaptation of the internal and external home environment. One participant described “shortened electric blanket cords beside bed … so I would not fall over it”.

The environmental aids sub-category represented responses that described using mobility aids such as a walking stick. The balance and mobility sub-category included measures relating to posture, balance and gait but excluded exercises. Examples included “Walking rather than shuffling; Make a conscious effort to lift my feet when walking”. The other sub-categories described and coded were:

Exercise: Continued with tai-chi; Balance exercises; Did quad [quadriceps] strengthening exercises; Seeing a physiotherapist to help me with my strength. Feet and Footwear: Podiatrist; Got rid of loose fitting shoes. Medication: Health check with doctor and using correct medications

Participants in both groups also provided responses, in addition to the falls prevention measures they listed, that appeared to reflect their increased beliefs about the need to reduce their risk of falling. This was evidenced by comments that demonstrated recognition of the need to change or modify their behaviour, with one participant stating “[I] truly believe I need to change”. Other responses indicated that participants accepted that the topic was personally relevant to them, with statements such as:

Awareness of the likelihood of falling at my age; Your presentation reinforced my current behaviour to prevent falls; I made a deliberate attempt to analyse my [falls] risks in my small unit.

Some responses were categorised as being not evidence based and some participants stated “none” or “nil” when asked to list measures they planned to take to reduce their risk of falls. Measures that were categorised as not being evidence based included “Slow down and take [your] time; Being careful always; Slower walking; Watching more”.

Discussion

This study showed that providing falls prevention education for groups of community-dwelling older adults using peers was an effective means of raising their beliefs, knowledge, motivation and intention to engage in falls prevention strategies. Previous studies showed that older adults may not be interested in or motivated to receive falls prevention information as they often underestimated their risk of falling, or tended to seek information only after experiencing falls (Haines et al. 2014; Khong et al. 2016). Other studies have also shown that older adults have low levels of knowledge about falls and falls prevention (Haines et al. 2014; Hill et al. 2011). Accordingly, providing education that raises knowledge and motivation is an important means of preparation for subsequent engagement in falls prevention strategies. Though both groups demonstrated significant increases in beliefs, knowledge and intention, only the intervention group reported a significant difference in having a clear action plan that they intended to follow to reduce their personal risk of falling. This finding suggests that the delivery of a theory-based contemporary presentation centred on behaviour change concepts can significantly raise the level of engagement in the audience. The peer educators who presented to the intervention groups were specific about encouraging each individual peer to attempt their personal goal setting and action plan during their presentation and it is possible that this specificity may be one of the factors in explaining the outcome.

Our findings identified that those participants who have discussed falls with a health professional previously or had some previous falls prevention information had greater knowledge and greater intention to engage in falls prevention. These results concur with another study (Lee et al. 2013) in highlighting that healthcare providers play an important role in facilitating older adults’ knowledge and motivation to manage their risk of falling. However, it has been found that relatively few people discuss falls and falls prevention with their health professionals (Lee et al. 2016). It has also been found in previous research that older adults who have not had a fall do not find falls prevention information personally relevant (Khong et al. 2016). As such, peer educators could play a role in encouraging their peers to discuss falls prevention with their health professionals and potentially improve older adults’ uptake of falls prevention strategies. However, the present presentations may need some continued tailoring to address this subgroup of older community-dwelling adults who have not fallen.

There was a significant gender bias in most of the responses to the peer education presentations, with women reporting significantly more intention to positively change their behaviour than men. This is consistent with previous research that found men are significantly less likely to perceive they are at risk of falls (Hughes et al. 2008), or to report falls or discuss falls with health providers (Stevens et al. 2012). There may be value in incorporating elements in future peer-led falls prevention education presentations that specifically note these gender differences, and consider strategies to meaningfully engage men in falls prevention. Another consideration may be the provision of a gender-based peer-led falls prevention presentation. Aligned with this, further research may be required to determine whether gender-congruent presenters might be likely to increase efficacy.

Limitations

The older adults who chose to participate in this study belonged to social groups and social participation has been shown to engender positive health-promoting benefits (Cohen 2004). In addition, these older adults would likely be required to travel either by car or public transport to attend group meetings. Hence, participants may have been more likely to be mobile, motivated and actively involved members of the older adult population. This could explain why the participants of both groups reported relatively high levels of knowledge and motivation even prior to the presentation. Accordingly, it would be beneficial to trial providing presentations to those relatively more isolated, older adults recruited through avenues that do not involve existing social groups such as were used for the peer education sessions in this study.

The challenges to the recruitment, training and retention of new peer educators have previously been identified as obstacles to the successful delivery of falls prevention programmes (Peel and Warburton 2009). The new peer educators delivered the contemporary presentations for the first time during the trial, meaning that they had limited experience. This was in contrast with the experienced peer educators who had delivered the existing presentations for between two and ten years. Hence, this could pose a bias against the contemporary programme in the outcomes. However, rigorous programme fidelity was monitored at various points of the research including the new peer educators’ delivery, to ensure the programme was implemented as intended (Bellg et al. 2004).

This educational research was conducted within the context of an ongoing falls prevention public health programme in the community and as such was a pragmatic non-randomised trial that was conducted under real-world conditions. The presentations were required to be delivered within certain timeframes and training was conducted within the community organisation’s regular training programme. The presentations were required to be delivered to those eligible groups who contacted the organisation during the research time frame. However, this approach had benefits in that it meant that the contemporary programme was embedded in the community partner organisation’s activities, supporting the programme’s subsequent sustainability. Additionally, the contemporary peer-led falls prevention education programme was also developed in a manner conducive to translation for real-world conditions without losing its intended effectiveness.

Finally, this study provided an important step in evaluating the potential of providing peer education as an approach to prevent falls. This study’s intervention, underpinned by evidence and behaviour change theory demonstrated outcomes that reflected older participants’ level of engagement with the falls prevention messages. Understanding the effectiveness of a programme’s outreach in bridging the gap in older adults’ knowledge and intention to engage in falls prevention messages can be deemed a critical step prior to delivering any falls prevention programmes especially those that measure falls outcomes as a primary end point. Future research should investigate how a peer-led education delivered in a group setting can be used to encourage older adults to take an interest, commence and sustain participation in other falls prevention programmes for older adults.

Conclusion

Providing peer education raises older adults’ levels of beliefs, knowledge and intention to engage in falls prevention. The contemporary presentation that incorporated adult learning principles and behaviour change concepts also resulted in older adults developing a clear action plan to undertake specific measures to reduce their risk of falls. Peer-led presentations are an effective means of providing community-dwelling older adults with falls prevention education.

Acknowledgement

The authors are grateful and thank the older adults who willingly gave their time to participate in the pre-tests, pilot trial, control group and intervention group trials. We would also like to thank Council on the Ageing Australia’s Mall Walkers at Karrinyup and Belmont, and particularly B. Joss and N. Gillman (Hollywood Functional Rehabilitation Clinic) for their help with the trials. We would especially like to thank Injury Control Council of Western Australia’s Falls Prevention Program’s staff especially Alexandra White and Juliana Summers and their volunteer peer educators for facilitating the conduct of this study. Finally, we are grateful to P. Chivers and M. Bulsara for their statistical expertise, advice and support.

Funding

This work was supported by the Australian Government’s Collaborative Research Networks (CRN) programme. The peer education programme is run as part of the Stay On Your Feet WA® programme. This falls prevention health promotion programme is coordinated by the Injury Control Council of Western Australia and supported by the Government of Western Australia.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- Abraham C, Michie S. A taxonomy of behavior change techniques used in interventions. Health Psychol. 2008;27(3):379–387. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.3.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AIHW: Bradley C (2012). Hospitalisations due to falls by older people, Australia 2007–08. AIHW, Canberra. Vol. Injury research and statistics series no. 61. Cat. no. INJCAT 137. Retrieved from http://www.nisu.flinders.edu.au/pubs/reports/2007/injcat96.pdf

- Allen T. Preventing falls in older people: evaluating a peer education approach. Br J Community Nurs. 2004;9(5):195–200. doi: 10.12968/bjcn.2004.9.5.12887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson LW, Krathwohl DR, Bloom BS. A taxonomy for learning, teaching, and assessing: a revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives. New York: Longman; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (2013) Socio-economic indexes for areas-postal areas (ABS catalogue 2033.0.55.001). ACT, Belconnen. Retrieved from http://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/DetailsPage/2033.0.55.0012011?OpenDocument

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare . Guidebook for preventing falls and harm from falls in older people: Australian community care. NSW: ACSQHC; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bellg AJ, Borrelli B, Resnick B, Hecht J, Minicucci DS, Ory M, Ogedegbe G, Orwig D, Ernst D, Czajkowski S, Workgroup Treatment Fidelity. Enhancing treatment fidelity in health behavior change studies: best practices and recommendations from the NIH behavior change consortium. Health Psychol. 2004;23(5):443–451. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.5.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cane J, O’Connor D, Michie S. Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implement Sci. 2012;7(1):1–17. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S. Social relationships and health. Am Psychol. 2004;59(8):676–684. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.8.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deandrea S, Lucenteforte E, Bravi F, Foschi R, La Vecchia C, Negri E. Risk factors for falls in community-dwelling older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiology. 2010;21(5):658–668. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181e89905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deery H, Day L, Fildes B. An impact evaluation of a falls prevention program among older people. Accid Anal Prev. 2000;32(3):427–433. doi: 10.1016/S0001-4575(99)00043-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickinson A, Machen I, Horton K, Jain D, Maddex T, Cove J. Fall prevention in the community: what older people say they need. Br J Community Nurs. 2011;16(4):174–180. doi: 10.12968/bjcn.2011.16.4.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elo S, Kyngas H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62(1):107–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming ND (2008) The VARK questionnaire (Version 7.8). Retrieved from http://vark-learn.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/The-VARK-Questionnaire.pdf

- Foster G, Taylor SJ, Eldridge SE, Ramsay J, Griffiths CJ. Self-management education programmes by lay leaders for people with chronic conditions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;4(4):CD005108. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005108.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie LD, Robertson MC, Gillespie WJ, Sherrington C, Gates S, Clemson LM, Lamb SE. Interventions for preventing falls in older people living in the community. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;9(11):CD007146. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007146.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haines TP, Hill A-M, Hill KD, McPhail S, Oliver D, Brauer S, Hoffman T, Beer C. Patient education to prevent falls among older hospital inpatients: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(6):516–524. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haines TP, Day L, Hill KD, Clemson L, Finch C. “Better for others than for me”: a belief that should shape our efforts to promote participation in falls prevention strategies. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2014;59(1):136–144. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill A-M, McPhail S, Hoffmann T, Hill K, Oliver D, Beer C, Brauer S, Haines TP. A randomized trial comparing digital video disc with written delivery of falls prevention education for older patients in hospital. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(8):1458–1463. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill A-M, Hoffmann T, Beer C, McPhail S, Hill KD, Oliver D, Brauer S, Haines TP. Falls after discharge from hospital: is there a gap between older peoples’ knowledge about falls prevention strategies and the research evidence? Gerontologist. 2011;51(5):653–662. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnr052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill A-M, Etherton-Beer C, Haines TP. Tailored education for older patients to facilitate engagement in falls prevention strategies after hospital discharge—a pilot randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(5):e63450. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill A-M, McPhail SM, Waldron N, Etherton-Beer C, Ingram K, Flicker L, Bulsara M, Haines TP. Fall rates in hospital rehabilitation units after individualised patient and staff education programmes: a pragmatic, stepped-wedge, cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;385(9987):2592–2599. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61945-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes K, van Beurden E, Eakin E, Barnett L, Patterson E, Backhouse J, Jones S, Hauser D, Beard J, Newman B. Older persons’ perception of risk of falling: implications for fall-prevention campaigns. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(2):351–357. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.115055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huijg JM, Gebhardt WA, Crone MR, Dusseldorp E, Presseau J. Discriminant content validity of a theoretical domains framework questionnaire for use in implementation research. Implement Sci. 2014;9(1):1–16. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-9-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Improved Clinical Effectiveness through Behavioural Research Group (ICEBeRG) Designing theoretically-informed implementation interventions. Implement Sci. 2006;1:4. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempton A, Van Beurden E, Sladden T, Garner E, Beard J. Older people can stay on their feet: final results of a community-based falls prevention programme. Health Promot Int. 2000;15(1):27–33. doi: 10.1093/heapro/15.1.27. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khong L, Farringdon F, Hill KD, Hill A-M. “We are all one together”: peer educators’ views about falls prevention education for community-dwelling older adults—a qualitative study. BMC Geriatr. 2015;15(28):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12877-015-0030-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khong L, Bulsara C, Hill KD, Hill A-M. How older adults would like falls prevention information delivered: fresh insights from a World Café forum. Ageing Soc. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):159–174. doi: 10.2307/2529310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DC, Day L, Hill K, Clemson L, McDermott F, Haines TP. What factors influence older adults to discuss falls with their health-care providers? Health Expect. 2013;18(5):1593–1609. doi: 10.1111/hex.12149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee DC, Brown T, Stolwyk R, O’Connor DW, Haines TP. Are older adults receiving evidence-based advice to prevent falls post-discharge from hospital? Health Educ J. 2016;75(4):448–463. doi: 10.1177/0017896915599562. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liang K-Y, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73(1):13–22. doi: 10.1093/biomet/73.1.13. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Merriam SB, Bierema LL. Adult learning: linking theory and practice. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Inc (Wiley); 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Michie S, Johnston M. Theories and techniques of behaviour change: developing a cumulative science of behaviour change. Health Psychol Rev. 2012;6(1):1–6. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2012.654964. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci. 2011;6(1):42. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-6-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyman SR, Victor CR. Older people’s participation in and engagement with falls prevention interventions in community settings: an augment to the Cochrane Systematic Review. Age Ageing. 2012;41(1):16–23. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afr103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peel NM. Epidemiology of falls in older age. Can J Aging. 2011;30(1):7–19. doi: 10.1017/S071498081000070X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peel NM, Warburton J. Using senior volunteers as peer educators: what is the evidence of effectiveness in falls prevention? Aust J Ageing. 2009;28(1):7–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-6612.2008.00320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portney LG, Watkins MP. Foundations of clinical research: applications to practice. 3. Upper Saddle River: Pearson/Prentice Hall; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- QSR International Pty Ltd (2012) NVivo 10 qualitative data analysis software

- Simoni JM, Franks JC, Lehavot K, Yard SS. Peer interventions to promote health: conceptual considerations. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2011;81(3):351–359. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.2011.01103.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens JA, Ballesteros MF, Mack KA, Rudd RA, DeCaro E, Adler G. Gender differences in seeking care for falls in the aged medicare population. Am J Prev Med. 2012;43(1):59–62. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walter SD, Eliasziw M, Donner A. Sample size and optimal designs for reliability studies. Stat Med. 1998;17(1):101–110. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0258(19980115)17:1<101::AID-SIM727>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson DS, Bangdiwala SI, Marshall SW, Waller AE. Repeated measures analysis of binary outcomes: applications to injury research. Accid Anal Prev. 1996;28(5):571–579. doi: 10.1016/0001-4575(96)00023-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yardley L, Bishop F, Beyer N, Hauer K, Kempen G, Piot-Ziegler C, Todd C, Cuttelod T, Horne M, Lanta K, Holt AR. Older people’s views of falls-prevention. Interventions in six European countries. Gerontologist. 2006;46(5):650–660. doi: 10.1093/geront/46.5.650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yardley L, Donovan-Hall M, Francis K, Todd C. Attitudes and beliefs that predict older people’s intention to undertake strength and balance training. J Gerontol Ser B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2007;62(2):P119–P125. doi: 10.1093/geronb/62.2.P119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]