Abstract

Transcription factors from the NusG family bind to the elongating RNA polymerase to enable synthesis of long RNAs in all domains of life. In bacteria, NusG frequently co-exists with specialized paralogs that regulate expression of a small set of targets, many of which encode virulence factors. Escherichia coli RfaH is the exemplar of this regulatory mechanism. In contrast to NusG, which freely binds to RNA polymerase, RfaH exists in a structurally distinct autoinhibitory state in which the RNA polymerase-binding site is buried at the interface between two RfaH domains. Binding to an ops DNA sequence triggers structural transformation wherein the domains dissociate and RfaH refolds into a NusG-like structure. Formation of the autoinhibitory state, and thus sequence-specific recruitment, represents the decisive step in the evolutionary history of the RfaH subfamily. We used computational and experimental approaches to identify the residues that confer the unique regulatory properties of RfaH. Our analysis highlighted highly conserved Ile and Phe residues at the RfaH interdomain interface. Replacement of these residues with equally conserved Glu and Val counterpart residues in NusG destabilized interactions between the RfaH domains and allowed sequence-independent recruitment to RNA polymerase, suggesting a plausible pathway for diversification of NusG paralogs.

INTRODUCTION

Gene duplication and subsequent functional divergence of paralogs is one of the main sources of evolutionary diversity in all living systems (1). Two models of functional adaptation are commonly considered: subfunctionalization, wherein the duplicates partition the ancestral function, and neofunctionalization, wherein one duplicate acquires a novel function. The evolution of the NusG family of transcription elongation factors provides a particularly striking example of neofunctionalization accompanied by transformation (2), the ability of one duplicate to undergo an α-to-β fold conversion that bestows a new function.

Proteins from the NusG/Spt5 family are the only known examples of universally conserved transcriptional regulators (3). NusG-like proteins are composed of an α/β N-terminal domain (NTD) and a β-barrel C-terminal domain (CTD) that contains a Kyprides-Onzonis-Woese (KOW) motif commonly found in ribosomal proteins (4). The two domains are connected by a flexible linker and together enable uninterrupted synthesis of long RNA molecules in synchrony with ongoing cellular processes, such as translation in prokaryotes and splicing and polyadenylation in eukaryotes. The NTDs bind to the two pincers of elongating RNA polymerase (RNAP), forming processivity clamps around the nucleic-acid chains (3). The location of the RNAP-binding site and the mode of NTD action appear to be ubiquitous among all NusG proteins (5). In contrast, the CTDs interact with an astonishingly diverse set of cellular partners that include the bacterial ribosome (6) and yeast splicing and capping factors (7).

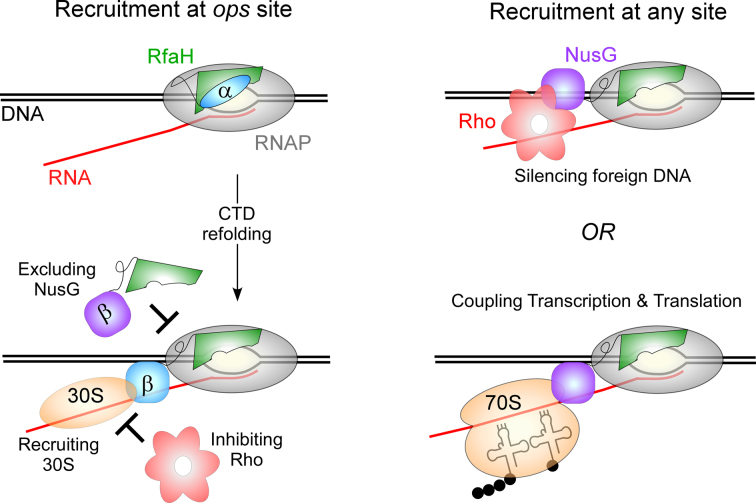

Escherichia coli NusG and its paralog RfaH are the best-characterized transcription elongation factors. RfaH and NusG share binding sites on the transcription elongation complex (TEC) and the ribosome, as well as the molecular mechanism of RNAP modification into a highly processive, pause-resistant state. Strikingly, however, the cellular functions of NusG and RfaH are not only different but opposite (Figure 1). NusG is an essential and abundant (∼5,000 copies/cell; (8)) protein that associates with RNAP transcribing almost all genes, displaying no apparent sequence specificity (9). The NusG CTD binds to the transcription termination factor Rho, stimulating Rho activity in vitro and in vivo (10). Together, NusG and Rho silence foreign DNA (11); NusG becomes largely dispensable in a genome-reduced E. coli strain from which the horizontally-acquired regions have been removed (11). By contrast, RfaH is scarce (50 copies/cell; (8)), does not bind to Rho (at least at physiological conditions/concentrations), and reduces Rho-dependent termination in vitro (12), likely by disfavoring the paused RNAP state which is a target for Rho. RfaH is recruited to only those few operons that contain a 12-nt-long ops DNA element in their leader regions (13) and strongly activates their expression by abolishing Rho-dependent termination (14) and increasing translation (15); RfaH excludes NusG through direct competition for the shared binding site on RNAP (13) and is thought to directly recruit the 30S subunit of the ribosome through protein-protein interactions between the CTD and the ribosomal protein S10 (15). Every gene that RfaH controls is horizontally transferred, and many of them are essential for virulence; loss of rfaH attenuates virulence in E. coli, Salmonella and Klebsiella pneumoniae (16–18).

Figure 1.

Regulatory mechanisms of RfaH and NusG.

Since RfaH directly opposes the action of the essential NusG, RfaH activity needs to be tightly controlled. This is accomplished by a combination of much reduced levels and exquisite specificity of RfaH, which depends absolutely on the ops signal for recruitment to the transcription elongation complex (TEC). A basic patch on the RfaH NTD recognizes the ops bases (19) on the non-template DNA strand in the transcription bubble exposed on the surface of RNAP paused at the ops site (12). These residues are not conserved in NusG, and this divergence could explain RfaH preference for a specific site. However, the ops plays another, more critical role in RfaH recruitment: contacts with ops transform a silent, autoinhibited RfaH into an activated state capable of binding to RNAP (20). In contrast to E. coli NusG, in which the freely rotating NTD and CTD are connected by a highly flexible linker (21), the CTD in free RfaH is folded as an α-helical hairpin that forms a large hydrophobic interdomain interface (IDI), masking the RNAP-binding site on the NTD (20). The domain dissociation is triggered by binding to the ops element and is a prerequisite for NTD recruitment to RNAP; similarly to NusG, the isolated RfaH NTD binds to the TEC indiscriminately, bypassing the need for activation (20).

The interconversion between the two different states of the CTD is a signature of RfaH action, with both states playing essential roles. The isolated CTDs of all NusG-like proteins, including RfaH, fold as nearly superimposable β-barrels. The β-CTD of RfaH binds to the ribosomal protein S10 to recruit the ribosome to the nascent mRNA, the most critical activity of RfaH; analogous NusG-S10 contacts are thought to couple transcription to translation. The α-CTD restricts RfaH action to a handful of genes, preserving the essential regulation by NusG. Thus, attainment of the transforming capability that is essential for autoinhibition was the key step in the evolution of dedicated RfaH-like regulators acting alongside NusG. The determinants of the dramatic refolding behavior of RfaH CTD are not yet known, although several molecular dynamics (MD) studies provided insights into this phenomenon. In this work, we carried out an analysis of bacterial NusG and RfaH subfamilies to identify specific residues that may define their different folds and respective properties. We show that substitutions of RfaH residues predicted to play key roles in maintenance of the interdomain contacts, Ile93 and Phe130, for their NusG counterparts relaxes the requirement for ops, ‘converting’ RfaH into a non-specific regulator in which the IDI is partially destabilized.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids and reagents

All general reagents were obtained from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) and ThermoFisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA, USA); NTPs—from GE Healthcare (Piscataway, NJ, USA); and [α32P]-CTP—from Perkin Elmer (Boston, MA, USA). PCR reagents, restriction and modification enzymes were from NEB and Roche (Indianapolis, IN, USA). Ni-sepharose resin, HiTrap Heparin HP and Resource Q columns were from GE Healthcare. Oligonucleotides were obtained from Sigma Aldrich. DNA purification kits were from Qiagen (Valencia, CA) and Promega (Madison, WI, USA).

Proteins

Escherichia coli RNAP core and σ70, WT RfaH and isolated domains were purified as in (20). RfaH variants I93E (pIA1253) and F130V (pIA1254) were constructed by site-directed mutagenesis in pIA751; these proteins carry a His6 tag followed by a TEV cleavage site and were purified from the XJb (λDE3) strain as described previously (19). To remove His tags, His6 tagged TEV protease (100 μg) was incubated with the protein sample (∼8 mg) at 4°C for 20 h. The cleaved-off His6 tag, the uncut His6-protein, and (His-tagged) TEV were removed by adsorption to Ni-sepharose. Proteins were dialyzed into storage buffer (50% glycerol, 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris–Cl pH 7.9, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM DTT) and stored at –20°C.

Template preparation

Templates for in vitro transcription were generated by PCR amplification from pIA1087 (WT ops) and pZL23 (G8C ops) reporter plasmids encoding the rfb leader region-lux operon fusion under control of E. coli PBAD promoter (15). To enable efficient transcription and the formation of halted radiolabeled TEC, the first PCR step was performed with a 73-nt long primer adding the T7A1 promoter and a 24-nt long U-less region to the rfb leader region (2536; AAAAAGAGTATTGACTTAAAGTCTAACCTATAGGATACTTA CAGCCATCGAGCAGGCAGCGGCAAAGCCATGG) and a reverse primer (2537; AAATAAGCGGCTCTCAGTTT). Following the removal of primers, the second step PCR was performed with primer 2537 and a forward primer 2499 (AAAAAGAGTATTGACTTAAAG). The amplified sequence spans –46 through +79 positions relative to the T7A1 transcription start site.

Single-round transcription elongation assays

Linear DNA template (30 nM), holo RNAP (40 nM), ApU (100 μM), and starting NTP substrates (1 μM CTP, 5 μM ATP and UTP, 10 μCi [α32P]-CTP, 3000 Ci/mmol) were mixed in 100 μl of TGA2 (20 mM Tris-acetate, 20 mM Na-acetate, 2 mM Mg-acetate, 5% glycerol, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mM EDTA, pH 7.9). Reactions were incubated for 15 min at 37°C; thus-halted TECs were stored on ice. RfaH variants (or an equal volume of storage buffer) were added to the TEC, followed by a 2-min incubation at 37°C. Transcription was restarted by addition of nucleotides (10 μM GTP, 150 μM ATP, CTP and UTP) and rifapentin to 25 μg/ml. Samples were removed at time points indicated in the figures and quenched by addition of an equal volume of STOP buffer (10 M urea, 60 mM EDTA, 45 mM Tris-borate; pH 8.3). Samples were heated for 2 min at 95°C and separated by electrophoresis in denaturing 8% acrylamide (19:1) gels (7 M urea, 0.5× TBE). The gels were dried and RNA products were visualized and quantified using the FLA9000 Phosphorimaging System, ImageQuant Software, and Microsoft Excel.

Chymotrypsin digestion

Chymotrypsin (Sigma Aldrich) was dissolved in 1 mM HCl (as recommended by the manufacturer) at 2 mg/ml and stored at –80°C in single-use aliquots. Prior to use, an aliquot was diluted into PBS, pH 7.4 (ThermoFisher Scientific) on ice. 9 μl of chymotrypsin in PBS (0.2 mg enzyme) were mixed with 6 μl of RfaH variants or domains (∼2 mg protein) in storage buffer (50% glycerol, 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris–Cl pH 7.9, 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM DTT). The volume used was dictated by the concentration of the least soluble RfaH variant, I93E; higher glycerol concentrations were found to inhibit chymotrypsin cleavage. To the control samples, only PBS was added. The reactions were incubated at 37°C for 10, 20, 40 and 80 min and stopped by the addition of 5 mM PMSF and LDS loading dye (ThermoFisher Scientific). Samples were heated at 75°C for 5 min and 8 μl were loaded onto 4–12% Bis–Tris gels, which were run in 1× SDS-MES buffer at 180 V. The gels were stained with GelCode Blue (ThermoFisher Scientific). With each RfaH variant, the assay was repeated at least three times; the WT protein was assayed in parallel every time.

Calculation of entropy and conservation score

RfaH sequences were aligned with implemented tools in ICM (22). Based on the alignment, we assessed two quantitative characteristics of diversity: Entropy and Conservation score. Entropy was calculated according to formula (1), where  is the normalized ratio of the observed frequency of amino acid a at position i divided by the expected frequency for the same amino acid.

is the normalized ratio of the observed frequency of amino acid a at position i divided by the expected frequency for the same amino acid.

|

(1) |

The conservation score is based on the mean pairwise score between residues j and k in alignment position i.  is number of sequences in the alignment,

is number of sequences in the alignment,  is the similarity between residues k and residues j at position i taken from a normalized compare matrix (23).

is the similarity between residues k and residues j at position i taken from a normalized compare matrix (23).

|

(2) |

|

Calculation of interdomain interface contact area

The IDI contact areas of residues of RfaH were calculated with implemented tools of ICM (24). First, the solvent-accessible areas of each residues were calculated using a water probe with a radius of 1.4 Å in the closed state, in which the CTD and the NTD interact. Then solvent-accessible areas were calculated upon separation of the two domains. The difference between the two represents the IDI contact areas of residues.

Calculation of domain binding energy contributions (ΔΔGbind) of residues

ΔΔGbind of each residue was calculated with implemented tools of ICM by evaluating the effect on the binding free energy upon its substitution with a glycine, using formulas (3) and (4), where

|

(3) |

|

(4) |

represents the binding free energy of the NTD and CTD in wildtype RfaH, while

represents the binding free energy of the NTD and CTD in wildtype RfaH, while  represents the binding free energy of the NTD and CTD in the altered RfaH.

represents the binding free energy of the NTD and CTD in the altered RfaH.  represents the internal energy (van der Waals, electrostatic, hydrogen bonds and torsion components) of NTD–CTD complex, while

represents the internal energy (van der Waals, electrostatic, hydrogen bonds and torsion components) of NTD–CTD complex, while  represents the sum of internal energy of NTD and CTD. Similarly,

represents the sum of internal energy of NTD and CTD. Similarly,  represents the solvation energy of the NTD–CTD complex, while

represents the solvation energy of the NTD–CTD complex, while  represents the sum of the solvation energies of the domains.

represents the sum of the solvation energies of the domains.

RESULTS

We first performed an in silico analysis of the RfaH and NusG subfamilies, in the following order: (i) to identify amino acid residues that are conserved in the RfaH subfamily; (ii) to assess their potential to disrupt the closed, α-helical state but not the open, β-barrel state; (iii) to simulate the structural and energetic effects of a substitution at the IDI in the closed state; and (iv) to identify the equivalent E. coli NusG residues that are conserved within the NusG subfamily yet distinct from those in RfaH.

Identifying residues that contribute to the closed-state stabilization in RfaH

1383 sequences of RfaH proteins in different organisms were obtained from InterPro (25), and duplicate identical sequences were removed. Alignment of the remaining 751 sequences built with ICM (26,27) identified ∼90% similarity-conservation for 36 positions (Figure 2). To quantitatively assess diversity, we calculated the entropy and the conservation score (Supplementary Table S1) of each RfaH residue (see Materials and Methods). Conserved residues have low entropies and high conservation scores; we set the conservation score >0.8 and entropy <0.9 as filters in this analysis.

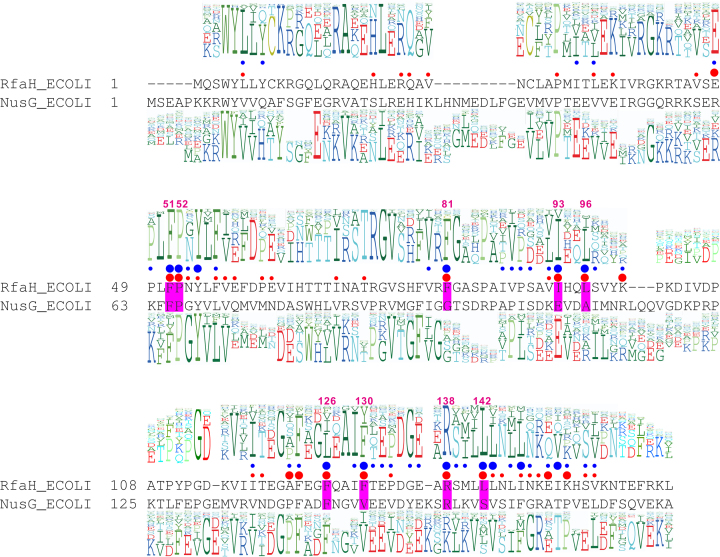

Figure 2.

The key features of the RfaH and NusG families. (A) Structural alignment of E. coli RfaH and NusG is shown in the middle. The NTD alignment was derived from the superposition of PDBs 2OUG (RfaH) and 2K06 (NusG), and the CTD alignment was derived from the superposition of PDBs 2LCL (RfaH) and 2KVQ (NusG). A profile above the alignment was generated from the sequence alignment of 751 RfaH sequences, while profile underneath was generated from the sequence alignment of 9204 NusG sequences. Red circles in the middle indicate the ΔΔGbind value; large, >1.5 kcal/mol, small, 1–1.5 kcal/mol. IDI contact areas are shown as blue circles; large, IDI contact areas >50 Å2, small, <50 Å2. The residues with large IDI contact areas and ΔΔGbind are shaded in magenta and labeled with the residue number in RfaH.

The unique closed state of RfaH is stabilized by interactions between the NTD and the α-helical CTD. To identify the residues that make key contributions to the closed-state stabilization, their IDI contact areas were calculated (see Materials and Methods). Residues with larger IDI contact areas are more likely to be directly involved in stabilizing the α-state of CTD and thus the closed state of RfaH. The IDI contact areas of each residue are shown as blue circles in Figure 2; large circles indicate IDI contact areas larger than 50 Å2; small circles, IDI contact areas between 0 and 50 Å2. A contact area of 50 Å2 was chosen as a filter.

To assess the energetic contribution of individual residues to the closed-state stabilization, we calculated the binding free energy change upon in silico substitution of each residue with glycine (28). Substitution of a residue important for domain interface stability is characterized by a positive ΔΔGbind value, indicated with a red circle in Figure 2. Large dots correspond to residues with ΔΔGbind larger than 1.5 kcal/mol (chosen as a filter), while small circles correspond to residues with ΔΔGbind between 1 and 1.5 kcal/mol. This analysis identified nine RfaH residues that display large IDI contact areas and ΔΔGbind: Phe51, Pro52, Phe81, Ile93, Leu96, Phe126, Phe130, Arg138, Leu142 (shown in magenta boxes in Figure 2). Leu96 and Phe126 residues were filtered out because their entropy scores (1 and 1.6, respectively) exceeded 0.9 (Supplementary Table S1).

In summary, seven RfaH residues passed through the selected filters (conservation score > 0.8; entropy < 0.9, IDI contact area > 50 Å2, ΔΔGbind > 1.5 kcal/mol). Among these residues, Ile93, Phe130, Arg138 and Leu142 have been proposed to play key roles in the stabilization of the IDI, based on computational and experimental evidence (15,29–34).

Identifying key residues that define RfaH and NusG subfamilies

Next, we sought to determine which of the seven selected residues are likely to be required for the formation of the RfaH-like closed state, and are thus different in NusG, in which the NTD and CTD do not interact (21). To identify NusG residues at the positions corresponding to Phe51, Pro52, Ile93, Phe130, Arg138 and Leu142 in RfaH, we performed structural alignment of E. coli RfaH and NusG (35). This analysis (Figure 2) revealed that Phe51, Pro52 and Arg138 residues are identical between RfaH and NusG, and are therefore unlikely to make specific contributions to the autoinhibitory state of RfaH. By contrast, the remaining four residues differ between the two proteins. We next performed sequence alignment of 9204 bacterial NusG proteins (Figure 2) to determine which of these residues should be selected for experimental validation. We found that NusG residues corresponding to RfaH Ile93 and Phe130 (Glu107 and Val148) are conserved in the alignment of NusG sequences (with Val or homologous Ile at position 148), whereas residues corresponding to Phe81 and Leu142 are not. Thus, we focused our functional analysis on Ile93 and Phe130, substituting these residues with Glu and Val, respectively, and testing the altered proteins in vitro. We expected that thus-altered RfaH proteins will have a weakened IDI and therefore sequence-independent, NusG-like recruitment to the TEC.

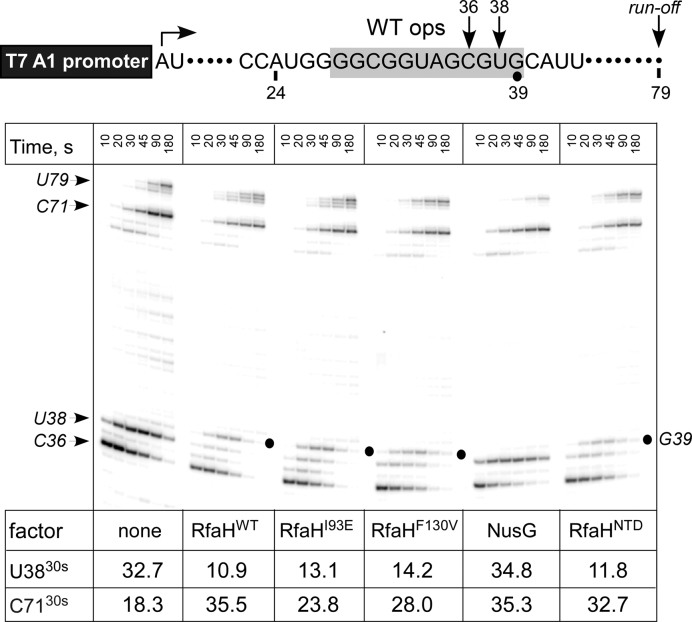

NusG-like RfaH variants are fully functional on an ops-containing template

We first tested the altered proteins during transcription in vitro. Because the affected residues are not involved in interactions with DNA or RNAP (Supplementary Figure S1), the mutant proteins should be recruited to RNAP paused at the ops site similarly to the wild-type (WT) RfaH, as long as their structure is not altered. To test this, we carried out single-round elongation assays on a template that contains the WT ops element (Figure 3). On this template, RNAP can be stalled at position A24 in the absence of UTP and restarted upon the addition of all NTPs. In the absence of transcription factors, RNAP pauses at C36 and U38 within the ops element, before making the full-length RNA of 79 nt; a strong arrest is observed at C71, likely because RNAP progression is hindered in the absence of the downstream duplex DNA (36); pausing at these sites is accentuated at low [GTP], the incoming substrate, as used in this assay. Addition of wild-type RfaH or the isolated NTD reduces pausing at U38 ∼3-fold, but delays RNAP 1 nt downstream, presumably via RfaH NTD-DNA interactions that must be broken to allow RNAP escape (19); this delay is not sensitive to NTP concentrations. I93E and F130V RfaH variants exhibit similar behavior at U38 and G39, whereas NusG does not. These results indicate that I93E and F130V substitutions do not interfere with RfaH recruitment to the TEC and antipausing modification of RNAP.

Figure 3.

Effects of RfaH variants on pausing at the ops site. (Top) Transcript generated from the T7A1 promoter on a linear DNA template; transcription start site (a bent arrow), ops element (gray box), and transcript end are indicated on top. (Bottom) Halted A24 TECs were formed as described in Materials and Methods. Elongation was restarted upon addition of NTPs and rifapentin in the presence of the indicated transcription factor. Aliquots were withdrawn at times indicated above each lane (in s) and analyzed on an 8% denaturing gel. Positions of the paused and run-off transcripts are indicated with arrows; the position of the RfaH-induced pause at G39, with a circle. Pausing at ops (U38; fraction of total RNA) and arrival at the C71 position (fraction of final at 180 sec) were quantified to assess the anti-pausing effects of elongation factors; 30-s values are shown below each panel. The experiment was repeated three times; errors were <15%.

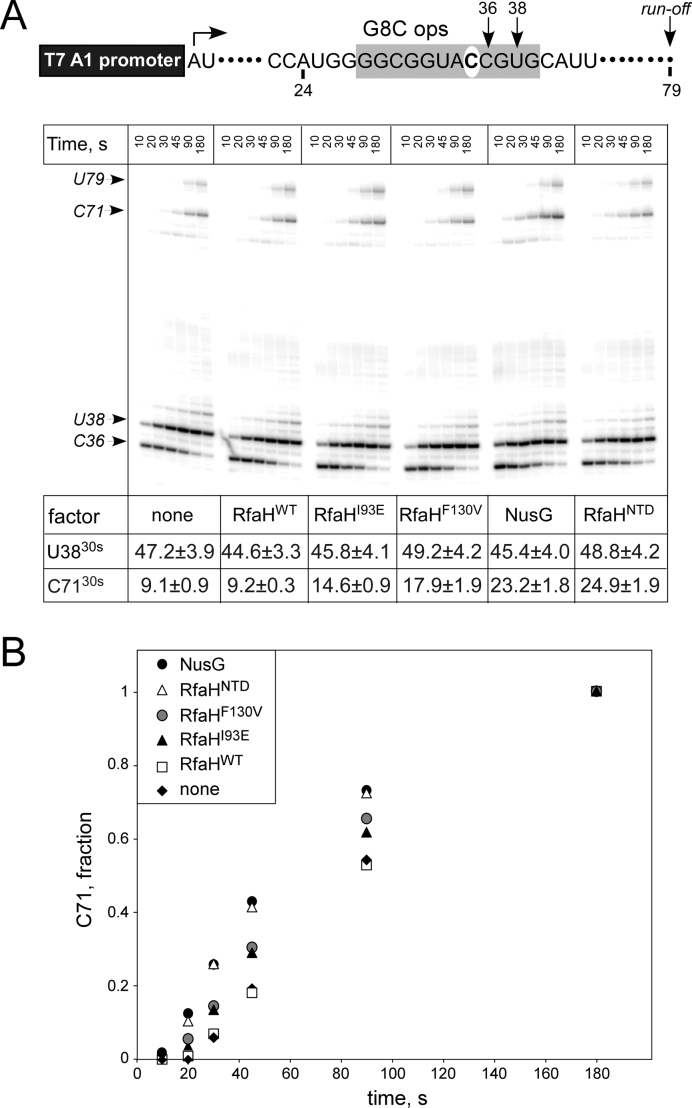

NusG-like RfaH variants can be recruited to TEC in the absence of ops

Our analysis suggested that Glu93 and Val130 could disfavor the autoinhibited state of RfaH, thereby facilitating sequence-independent (NusG-like) recruitment to RNAP. To test this hypothesis, we used a template in which an invariant ops residue G8 was substituted with C (Figure 4). This substitution preserves the pausing pattern but abolishes recruitment to ops, and thus anti-pausing activity, of WT RfaH. By contrast, the isolated NTD and NusG increase the rate of RNAP elongation, leading to faster arrival at C71, a ∼2.5-fold effect at the 30-s timepoint (Figure 4). In support of our prediction, I93E and F130V RfaH variants exhibit intermediate phenotypes, speeding arrival at C71 1.6- and 2-fold, respectively. These results indicate that a single substitution of a key RfaH residue for its NusG counterpart is sufficient to allow for ops-independent recruitment. Conversely, this suggests that a single mutation in the nascent NusG duplicate could enable the formation of the silenced, autoinhibited state.

Figure 4.

Effects of RfaH variants on pausing in the absence of ops. (A) The experiment was performed as in Figure 3, except that a mutant ops element, with G8 substituted for a C (white oval), was used. (B) Arrival at the C71 position was quantified; the error bars are omitted for clarity. A representative example (30-s) is shown below in panel A, along with the fraction of U38 RNA; errors are standard deviations calculated from three repeats.

Probing RNAP-binding site accessibility by proteolysis

Our observations that RfaH I93E and F130V variants facilitate RNA synthesis on the mutant ops template (Figure 4) are consistent with the hypothesis that these substitutions destabilize the domain interface, leading to spontaneous, ops-independent exposure of the RNAP-binding surface on the NTD. Similarly to the isolated NTD (20), these variants are prone to aggregation and precipitate at concentrations >10 μM. The limited solubility of altered RfaH variants does not interfere with in vitro transcription analysis but hinders their structural characterization. Furthermore, the conformational transitions that accompany RfaH domain dissociation are complex, involving CTD refolding that may proceed via at least one intermediate (32).

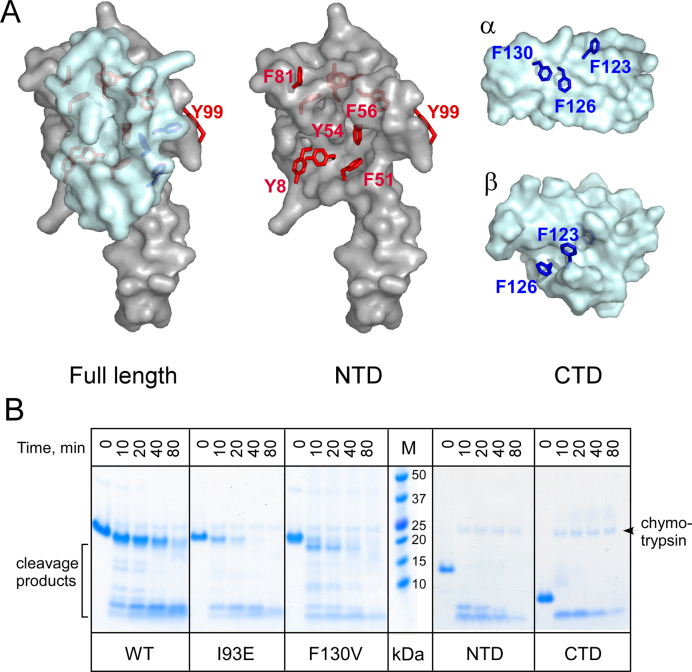

We therefore sought an approach to directly probe the accessibility of the RNAP-binding site on the NTD at low protein concentrations. The β’ clamp helices (CH) domain interacts with a cluster of aromatic residues in the NTD (20); substitutions of these residues abolish RfaH recruitment (19). To directly probe the solvent accessibility of this site, we used chymotrypsin, a serine protease that preferentially binds to and cleaves the C-termini of aromatic residues (37). In full-length RfaH, all aromatic residues except Tyr99 are buried, whereas upon domain separation, the residues that comprise the RNAP-binding site on the NTD and at least two Phe residues on the CTD should become exposed and thus accessible to chymotrypsin (Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

Probing the RfaH domain dissociation by chymotrypsin digestion. (A) Accessibility of aromatic residues in the full length RfaH and the isolated domains. The NTD is shown in gray and the CTD in cyan; both states of the CTD are shown. The aromatic residues are shown as sticks (red in the NTD; blue in the CTD), with their surfaces hidden. This figure was prepared with Pymol 1.8.2.3 (Schrödinger, LLC) using PDB IDs 2OUG and 2LCL. (B) Chymotrypsin cleavage of selected protein variants. The assays were performed as described in Materials and Methods; the samples were analyzed on 17-well 4–12% Bis–Tris gels. The WT, 193E and F130V samples were analyzed on one gel, and the isolated domains (along with the full-length protein, not shown) on another. Chymotrypsin is visible above the uncut proteins.

The full-length WT RfaH was highly resistant to chymotrypsin, requiring large concentrations of protease for cleavage (visible on the gel; Figure 5B). By contrast, the isolated domains were rapidly cleaved, confirming the utility of this approach. The I93E and F130V substitutions conferred increased susceptibility to chymotrypsin cleavage as compared to the WT RfaH (Figure 5B). These results indicate that these substitutions weaken the domain interface, promoting CTD dissociation and subsequent RNAP binding. We note that while we cannot identify which form of the CTD is being cleaved (since Phe123 and Phe126 could be accessible in either the α- or β-state; Figure 5A) by gel analysis, this approach could be adapted to monitor CTD folding by measuring the exposure of Phe130, which is part of the hydrophobic core of the β-barrel CTD (15).

We argue that proteolytic enzymes are better suited for probing the accessibility of protein-binding interfaces than small molecules, e.g. hydrophobic dyes used in differential scanning fluorimetry (38). Enzymatic probing can be carried out under conditions that mimic those used for functional assays (concentrations, temperature, etc.) and allows for a more realistic assessment of binding-site exposure to a large protein ligand.

DISCUSSION

Autoinhibition is a widespread phenomenon that links protein activity to the presence of a cognate signal. During autoinhibition, intramolecular interactions between separate regions of a polypeptide negatively regulate its function, ensuring that activation is achieved only in response to proper physiological signals. Inhibition of ligand binding is the most common class of autoinhibition (39), where nucleic acid or protein interaction sites on a functional domain (FD) are masked by an inhibitory module (IM). Autoinhibition frequently modulates binding to DNA in transcription factors, such as σ70 (40) and Ets factors (41,42). Evolution of an autoinhibited state was essential for the diversification of a nascent paralog of NusG, a housekeeping transcription elongation factor that regulates the synthesis of most cellular RNAs, into a dedicated regulator that controls just a handful of genes. In this study, we sought to identify the determinants of autoinhibition using E. coli RfaH, a highly specialized NusG paralog in which the relief of autoinhibition is achieved via interactions with a specific target DNA sequence presented on the surface of the elongating RNAP.

Structural determinants of RfaH autoinhibition

Escherichia coli RfaH is a transformer protein that exists in two alternative states (2). In the closed, autoinhibited state, the α-helical CTD masks the RNAP-binding site on the NTD. Interactions with the ops DNA induce opening of the RfaH IDI, releasing the CTD that subsequently refolds into a β-barrel. Our research has demonstrated that the stability of the RfaH IDI is responsible for the maintenance of the alternative α-helical CTD fold, autoinhibition, and resulting sequence specificity all lacked by its NusG-like ancestor (15,20,43). Here, we show that the primary determinants of this increased stability can be identified through a synergistic approach unifying phylogenetic, structural, and biochemical evidence. This suggests that such an approach might prove useful in studying other examples of protein autoinhibition thought to be involved in many fundamental cellular signaling mechanisms (44), virulence (45), and disease states (46–48).

Here, we have identified two RfaH residues, Ile93 and Phe130, predicted to be uniquely important for IDI stability. We show that substitution of either residue for its NusG counterpart (I93E and F130V) alters the stability of the RfaH IDI so drastically as to convert the protein into a NusG-like regulator, with the loss of the sequence-dependent recruitment to the TEC characteristic of the former. It should also be acknowledged that many researchers, including ourselves, have studied the two native-state conformations of RfaH and potential mechanisms of interconversion between them using a variety of MD simulations. These simulations, to our knowledge, have only probed the thermodynamics and kinetics of RfaH (re)folding in the absence of DNA, the ligand that triggers the relief of autoinhibition. Nonetheless, they have yielded several testable predictions that our study has been able to validate and place within a broader context.

Chapagain and colleagues devised targeted and steered MD simulations showing that the breaking of contacts in the IDI presents the major thermodynamic barrier to the conversion of the RfaH CTD from α-helix to β-barrel, and also that Phe130 plays an important role in weakening of these contacts (30). We reached the same conclusions independently using a dual-basin structure-based simulation (32). Chapagain and colleagues also found that a nascent interdomain contact between Ile93 and Phe126 exposes an otherwise buried hydrophobic core in the NTD that prevents its binding to the β’ CH domain (30). These findings are supported by our demonstration of the importance of the Phe130 and Ile93 residues for IDI stability (Figure 5) and autoinhibition (Figure 4).

Still other studies explain not only why the Phe130 residue is so vital for RfaH-style functionality, but also why its substitution for valine proves so destructive. Valine and isoleucine residues strongly favor a β secondary structure to an α one (49), and F130V possesses a new valine residue adjacent to an isoleucine (at 129), increasing the propensity of the RfaH CTD to fold as a β-structure (the only one that the NusG CTD forms). Moreover, while three MD simulations using different methodologies, dual-basin structure-based (32), Markov State Model and transition path theory (31), and coarse-grained off-lattice MD modeling (33), identified multiple candidate mechanisms for the α→β conversion of RfaH, all of these mechanisms had as their first step the formation of a β-sheet involving Phe130.

Our results also verify and build upon broader findings regarding the fundamental properties and regulation of autoinhibited proteins generally. A study by Gsponer and colleagues (44) found that when an interface exists between the FD and at least one IM, (i) residues in the IM-FD IDI are conserved regardless of their diversity across homologs in the IM and (ii) intrinsically disordered IMs are preferable to structured ones since greater variation in intrinsic disorder should allow for fine-tuning of the equilibrium between active and inactive states on which the regulation depends. If we define the RfaH IM to include both its transformable CTD and the flexible linker (the NTD is of course the FD, as it confers the desired sequence-specific recruitment to the TEC), then our validation of (i) is apparent from the phylogenetic analysis (Figure 2) and the relief of autoinhibition resulting from changes of the IDI residues (Figure 4). The recent μs-timescale MD simulation by Xun et al. demonstrated that two intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) are necessary to stabilize the α-form of the CTD (34), with Phe130 making a contact with IDR1. The status of the linker as an IDR is supported by its tolerance to deletions and insertions and its absence from X-ray and NMR structures (15,20), implying its flexibility. Thus, the available data validate (ii) as a key feature of IMs, exemplified by RfaH.

Autoinhibition in regulation of NusG-like proteins

While we have focused on converting RfaH into NusG, it is also interesting to ask the reverse question: could NusG be converted into RfaH, conferring autoinhibition in the process? Our results would indicate that if the IDI contacts can be made sufficiently strong, then the reverse conversion should be possible. Indeed, a recent report by Rösch and co-authors showed that Thermotoga maritima NusG is autoinhibited due to particularly strong IDI interactions absent from all other NusG variants yet found (50). Interactions between the NTD and the β-barrel CTD of T. maritima NusG mask the binding sites for Rho, S10, and RNAP and must be broken to attain the active state. This autoinhibited state is argued to thermally stabilize the protein, rather than tune its regulatory properties, a function that may be critically important in the hyperthermophilic niche of T. maritima (50).

By contrast, autoinhibition is critical for delineating RfaH targets and conferring the dramatic activation of gene expression by RfaH. The closed state of RfaH masks the binding sites for both its cellular protein targets, RNAP and the ribosome. While the contact site with RNAP is merely masked by the IM, and can be exposed upon proteolytic removal of the CTD and part of the linker (20), the ribosome binding site is simply missing in the α-helical CTD. A complete refolding of the RfaH CTD into a β-barrel creates the interaction surface for S10 (15), with the resulting CTD-S10 complex closely resembling that formed by NusG (6). This transformation is critical for RfaH function as it enables recruitment of the 30S ribosomal subunit to mRNAs that lack ribosome-binding sequences (15); in fact, expression of a reporter gene can be made dependent on RfaH by adding the ops sequence and removing the ribosome binding sequence in front of heterologous reporter genes (15). Dramatic activation of translation by RfaH is thought to insulate its target RNAs from premature termination by Rho (14), which silences these and other foreign genes (11). Curiously, Clostridium botulinum Rho has been recently reported to undergo a prion-like transformation that inhibits its function (51), highlighting the widespread role of dramatic conformational changes in the regulation of bacterial gene expression.

Specialized NusG paralogs present in diverse bacterial phyla regulate expression of genes encoding biosynthesis of capsules in K. pneumoniae (16) and Bacteroides fragilis (52), toxins in E. coli (53) and Serratia entomophila (54), and antibiotics in Myxococcus xanthus (55) and Bacillus amyloliquefaciens (56). Some RfaH homologs are encoded on large conjugative multidrug-resistance plasmids and have been proposed to activate the pilus biosynthesis operons (3), by analogy to RfaH-mediated activation of the tra operon on F plasmid (53). Thus, in addition to their well-established roles in virulence (16–18), RfaH-like regulators may also be essential for the spread of antibiotic-resistant genes. While these factors must function alongside ubiquitous NusG, it is not yet known if their recruitment to RNAP is regulated by autoinhibition and if they can undergo transformation similarly to RfaH.

Broader impacts

The presence of autoinhibited proteins in key cellular signaling and virulence pathways and their association with a plethora of pathological conditions underlies the importance of better understanding their evolution, diversification, and regulation. Here we have combined experimental and computational techniques into an approach that can quantitatively and directly assess IDI stability and the primary determinants thereof, allowing the unification and synthesis of disparate lines of evidence and showing a path towards the rational alteration or disruption of autoinhibited proteins for anti-virulent and other therapeutic ends.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Angela Fleig for technical assistance with protein purification. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health [R01 GM67153 to I.A.]. The open access publication charge for this paper has been waived by Oxford University Press—NAR Editorial Board members are entitled to one free paper per year in recognition of their work on behalf of the journal.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Espinosa-Cantu A., Ascencio D., Barona-Gomez F., DeLuna A.. Gene duplication and the evolution of moonlighting proteins. Front. Genet. 2015; 6:227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Knauer S.H., Rosch P., Artsimovitch I.. Transformation: the next level of regulation. RNA Biol. 2012; 9:1418–1423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tomar S.K., Artsimovitch I.. NusG-Spt5 proteins-Universal tools for transcription modification and communication. Chem. Rev. 2013; 113:8604–8619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Steiner T., Kaiser J.T., Marinkovic S., Huber R., Wahl M.C.. Crystal structures of transcription factor NusG in light of its nucleic acid- and protein-binding activities. EMBO J. 2002; 21:4641–4653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yakhnin A.V., Babitzke P.. NusG/Spt5: are there common functions of this ubiquitous transcription elongation factor?. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2014; 18:68–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Burmann B.M., Schweimer K., Luo X., Wahl M.C., Stitt B.L., Gottesman M.E., Rosch P.. A NusE:NusG complex links transcription and translation. Science. 2010; 328:501–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hartzog G.A., Fu J.. The Spt4-Spt5 complex: a multi-faceted regulator of transcription elongation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2013; 1829:105–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schmidt A., Kochanowski K., Vedelaar S., Ahrne E., Volkmer B., Callipo L., Knoops K., Bauer M., Aebersold R., Heinemann M.. The quantitative and condition-dependent Escherichia coli proteome. Nat. Biotechnol. 2016; 34:104–110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mooney R.A., Davis S.E., Peters J.M., Rowland J.L., Ansari A.Z., Landick R.. Regulator trafficking on bacterial transcription units in vivo. Mol. Cell. 2009; 33:97–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mooney R.A., Schweimer K., Rosch P., Gottesman M., Landick R.. Two structurally independent domains of E. coli NusG create regulatory plasticity via distinct interactions with RNA polymerase and regulators. J. Mol. Biol. 2009; 391:341–358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cardinale C.J., Washburn R.S., Tadigotla V.R., Brown L.M., Gottesman M.E., Nudler E.. Termination factor Rho and its cofactors NusA and NusG silence foreign DNA in E. coli. Science. 2008; 320:935–938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Artsimovitch I., Landick R.. The transcriptional regulator RfaH stimulates RNA chain synthesis after recruitment to elongation complexes by the exposed nontemplate DNA strand. Cell. 2002; 109:193–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Belogurov G.A., Mooney R.A., Svetlov V., Landick R., Artsimovitch I.. Functional specialization of transcription elongation factors. EMBO J. 2009; 28:112–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sevostyanova A., Belogurov G.A., Mooney R.A., Landick R., Artsimovitch I.. The beta subunit gate loop is required for RNA polymerase modification by RfaH and NusG. Mol. Cell. 2011; 43:253–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Burmann B.M., Knauer S.H., Sevostyanova A., Schweimer K., Mooney R.A., Landick R., Artsimovitch I., Rosch P.. An alpha helix to beta barrel domain switch transforms the transcription factor RfaH into a translation factor. Cell. 2012; 150:291–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bachman M.A., Breen P., Deornellas V., Mu Q., Zhao L., Wu W., Cavalcoli J.D., Mobley H.L.. Genome-wide identification of Klebsiella pneumoniae fitness genes during lung infection. MBio. 2015; 6:e00775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nagy G., Danino V., Dobrindt U., Pallen M., Chaudhuri R., Emody L., Hinton J.C., Hacker J.. Down-regulation of key virulence factors makes the Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium rfaH mutant a promising live-attenuated vaccine candidate. Infect. Immun. 2006; 74:5914–5925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nagy G., Dobrindt U., Schneider G., Khan A.S., Hacker J., Emody L.. Loss of regulatory protein RfaH attenuates virulence of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 2002; 70:4406–4413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Belogurov G.A., Sevostyanova A., Svetlov V., Artsimovitch I.. Functional regions of the N-terminal domain of the antiterminator RfaH. Mol. Microbiol. 2010; 76:286–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Belogurov G.A., Vassylyeva M.N., Svetlov V., Klyuyev S., Grishin N.V., Vassylyev D.G., Artsimovitch I.. Structural basis for converting a general transcription factor into an operon-specific virulence regulator. Mol. Cell. 2007; 26:117–129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Burmann B.M., Scheckenhofer U., Schweimer K., Rosch P.. Domain interactions of the transcription-translation coupling factor Escherichia coli NusG are intermolecular and transient. Biochem. J. 2011; 435:783–789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Abagyan R., Raush E., Totrov M., Orry A.. ICM Manual v3.8-6. 2017; San Diego: Molsoft LCC. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gonnet G.H., Cohen M.A., Benner S.A.. Exhaustive matching of the entire protein sequence database. Science. 1992; 256:1443–1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Abagyan R.A., Totrov M.M.. Contact area difference (CAD): a robust measure to evaluate accuracy of protein models. J. Mol. Biol. 1997; 268:678–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Finn R.D., Attwood T.K., Babbitt P.C., Bateman A., Bork P., Bridge A.J., Chang H.Y., Dosztanyi Z., El-Gebali S., Fraser M. et al. InterPro in 2017-beyond protein family and domain annotations. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017; 45:D190–D199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Abagyan R., Totrov M., Kuznetsov D.. ICM — a new method for protein modeling and design: applications to docking and structure prediction from the distorted native conformation. J. Comput. Chem. 1994; 15:488–506. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Abagyan R.A., Batalov S.. Do aligned sequences share the same fold. J. Mol. Biol. 1997; 273:355–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Bordner A.J., Abagyan R.A.. Large-scale prediction of protein geometry and stability changes for arbitrary single point mutations. Proteins. 2004; 57:400–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Balasco N., Barone D., Vitagliano L.. Structural conversion of the transformer protein RfaH: new insights derived from protein structure prediction and molecular dynamics simulations. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2015; 33:2173–2179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gc J.B., Gerstman B.S., Chapagain P.P.. The role of the interdomain interactions on RfaH dynamics and conformational transformation. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2015; 119:12750–12759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Li S., Xiong B., Xu Y., Lu T., Luo X., Luo C., Shen J., Chen K., Zheng M., Jiang H.. Mechanism of the all-alpha to all-beta conformational transition of RfaH-CTD: molecular dynamics simulation and Markov state model. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2014; 10:2255–2264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ramirez-Sarmiento C.A., Noel J.K., Valenzuela S.L., Artsimovitch I.. Interdomain contacts control native state switching of RfaH on a dual-funneled landscape. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2015; 11:e1004379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Xiong L., Liu Z.. Molecular dynamics study on folding and allostery in RfaH. Proteins. 2015; 83:1582–1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Xun S., Jiang F., Wu Y.D.. Intrinsically disordered regions stabilize the helical form of the C-terminal domain of RfaH: A molecular dynamics study. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Marsden B., Abagyan R.. SAD–a normalized structural alignment database: improving sequence-structure alignments. Bioinformatics. 2004; 20:2333–2344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Izban M.G., Samkurashvili I., Luse D.S.. RNA polymerase II ternary complexes may become arrested after transcribing to within 10 bases of the end of linear templates. J. Biol. Chem. 1995; 270:2290–2297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Appel W. Chymotrypsin: molecular and catalytic properties. Clin. Biochem. 1986; 19:317–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lavinder J.J., Hari S.B., Sullivan B.J., Magliery T.J.. High-throughput thermal scanning: a general, rapid dye-binding thermal shift screen for protein engineering. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009; 131:3794–3795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pufall M.A., Graves B.J.. Autoinhibitory domains: modular effectors of cellular regulation. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2002; 18:421–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dombroski A.J., Walter W.A., Record M.T. Jr, Siegele D.A., Gross C.A.. Polypeptides containing highly conserved regions of transcription initiation factor sigma 70 exhibit specificity of binding to promoter DNA. Cell. 1992; 70:501–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Samorodnitsky D., Szyjka C., Koudelka G.B.. A role for autoinhibition in preventing dimerization of the transcription factor ETS1. J. Biol. Chem. 2015; 290:22101–22110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Currie S.L., Lau D.K., Doane J.J., Whitby F.G., Okon M., McIntosh L.P., Graves B.J.. Structured and disordered regions cooperatively mediate DNA-binding autoinhibition of ETS factors ETV1, ETV4 and ETV5. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017; 45:2223–2241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Tomar S.K., Knauer S.H., Nandymazumdar M., Rosch P., Artsimovitch I.. Interdomain contacts control folding of transcription factor RfaH. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013; 41:10077–10085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Trudeau T., Nassar R., Cumberworth A., Wong E.T., Woollard G., Gsponer J.. Structure and intrinsic disorder in protein autoinhibition. Structure. 2013; 21:332–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Cai Z., Yuan Z.H., Zhang H., Pan Y., Wu Y., Tian X.Q., Wang F.F., Wang L., Qian W.. Fatty acid DSF binds and allosterically activates histidine kinase RpfC of phytopathogenic bacterium Xanthomonas campestris pv. campestris to regulate quorum-sensing and virulence. PLoS Pathog. 2017; 13:e1006304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Takemoto-Kimura S., Suzuki K., Horigane S.I., Kamijo S., Inoue M., Sakamoto M., Fujii H., Bito H.. Calmodulin kinases: essential regulators in health and disease. J. Neurochem. 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Emptage R.P., Lemmon M.A., Ferguson K.M.. Molecular determinants of KA1 domain-mediated autoinhibition and phospholipid activation of MARK1 kinase. Biochem. J. 2017; 474:385–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Bianchi S., van Riel W.E., Kraatz S.H., Olieric N., Frey D., Katrukha E.A., Jaussi R., Missimer J., Grigoriev I., Olieric V. et al. Structural basis for misregulation of kinesin KIF21A autoinhibition by CFEOM1 disease mutations. Sci. Rep. 2016; 6:30668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Myers J.K., Pace C.N., Scholtz J.M.. A direct comparison of helix propensity in proteins and peptides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997; 94:2833–2837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Drogemuller J., Schneider C., Schweimer K., Strauss M., Wohrl B.M., Rosch P., Knauer S.H.. Thermotoga maritima NusG: domain interaction mediates autoinhibition and thermostability. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017; 45:446–460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Yuan A.H., Hochschild A.. A bacterial global regulator forms a prion. Science. 2017; 355:198–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Chatzidaki-Livanis M., Coyne M.J., Comstock L.E.. A family of transcriptional antitermination factors necessary for synthesis of the capsular polysaccharides of Bacteroides fragilis. J Bacteriol. 2009; 191:7288–7295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Bailey M.J., Koronakis V., Schmoll T., Hughes C.. Escherichia coli HlyT protein, a transcriptional activator of haemolysin synthesis and secretion, is encoded by the rfaH (sfrB) locus required for expression of sex factor and lipopolysaccharide genes. Mol. Microbiol. 1992; 6:1003–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hurst M.R., Beard S.S., Jackson T.A., Jones S.M.. Isolation and characterization of the Serratia entomophila antifeeding prophage. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2007; 270:42–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Paitan Y., Orr E., Ron E.Z., Rosenberg E.. A NusG-like transcription anti-terminator is involved in the biosynthesis of the polyketide antibiotic TA of Myxococcus xanthus. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1999; 170:221–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Goodson J.R., Klupt S., Zhang C., Straight P., Winkler W.C.. LoaP is a broadly conserved antiterminator protein that regulates antibiotic gene clusters in Bacillus amyloliquefaciens. Nat. Microbiol. 2017; 2:17003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.