Abstract

Anisakiasis is a parasitic infection caused by larval stages of nematodes of the genus Anisakis, Pseudoterranova and Contracaecum, of the Anisakidae family. The lifecycle of these nematodes develops in aquatic organisms and their final hosts are marine mammals. However, humans can act as accidental hosts and become infected with infective stage larvae (L3) by consuming raw or undercooked fish or shellfish carrying the parasite. Of this group of parasites, the genus Anisakis is the most studied: its presence in humans is associated with non-specific gastrointestinal symptoms or allergic responses that can trigger anaphylactic shock. The lack of studies in anisakiasis and Anisakis in Colombia has resulted in this infection being little-known by medical practitioners and therefore potentially underreported. The objective of this study was to identify anisakid nematodes in the flathead grey mullet fish (Mugil cephalus), caught by artisanal fishing methods and commercialized in Buenaventura. Morphological identification was carried out by classical taxonomy complemented by microscopy study using the histochemical technique Hematoxylin-Eosin. Nematodes of the genus Anisakis were found in the host M. cephalus. The Prevalence of Anisakis larvae in flathead grey mullet fish was 33%. The findings confirm the presence of Anisakis sp. in fish for human consumption in the Colombian Pacific region, a justification for further investigation into a possible emerging disease in this country.

Keywords: Anisakis, Allergy, Anisakiasis, Mullet fish, Emerging diseases

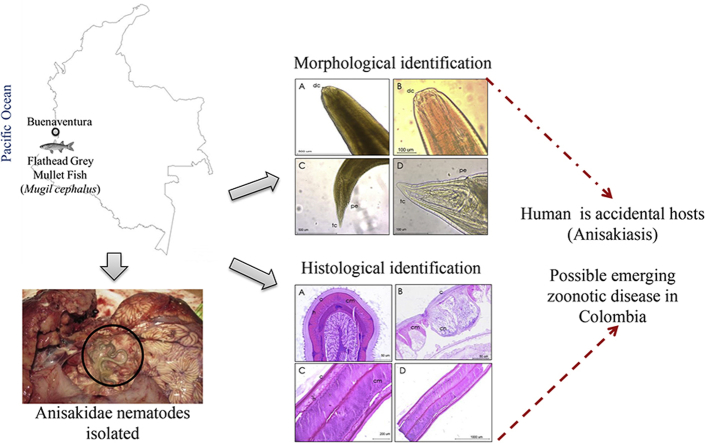

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

The research confirmed the presence of anisakids in the fish M. cephalus in Colombia.

-

•

First report such anisakids in fish from Colombia's Pacific coast.

-

•

Is confirmed the presence of the genus Anisakis in the country.

-

•

Anisakis spp. is associated with allergic reactions and gastro-allergies in humans.

-

•

The presence the anisakids suggests a possible emerging zoonotic disease in Colombia.

1. Introduction

Anisakiasis is a parasitic disease caused by the larval stages of nematodes of the genus Anisakis, Pseudoterranova and Contracaecum, belonging to the Anisakidae family (Phylum: Nematoda, Class: Chromadorea, Order: Ascaridida, Family: Anisakidae) (Acha and Szyfres, 2003). Although differentiation between species can only be carried out using molecular biology techniques, it is possible to distinguish between genera by classical taxonomy. For the genus Anisakis, the morphological classification of larvae into Type I or Type II is of particular use, following the criteria developed by Shiraki in 1974 (D'Amelio et al., 2000).

The adult form of these nematodes is found in the intestinal lumen of marine mammals, where they lay eggs that are expelled via the faeces of the host. While the eggs are floating in the water, the larval stages L1 and L2 develop in their interior. The L2 larvae are then ingested by small crustaceans, inside of which the L3 stage is reached. The infected crustaceans are then ingested by fish, where L3 larvae are trapped in their gastrointestinal tract. The life cycle of the nematode is completed when the infected fish are ingested by marine mammals, inside of which the next stage, L4, and subsequently their adult form, are reached. The human being becomes an accidental host by swallowing larvae in their third stage when consuming raw or undercooked cephalopod fish or molluscs (Acha and Szyfres, 2003, Chai et al., 2005, Mehlhorn and Aspock, 2008). It is usually a single larva, which, once ingested, enters the body and can be located in the mucosa of the esophagus, stomach, duodenum, jejunum, ileum or colon (Peláez et al., 2008).

Gastric anisakiasis produces epigastralgia, nausea and vomiting of onset between 1 and 8 h after consuming the contaminated food. Intestinal anisakiasis presents with distension and intense abdominal pain 5–7 days after the parasite is ingested (Bouree et al., 1995, Chai et al., 2005, Chopra et al., 2016). Other atypical forms of presentation described in the literature include cases of eosinophilic esophagitis, upper gastrointestinal bleeding and gastroesophageal reflux disease (Ghimire et al., 2016, Rezapour and Agarwal, 2017, Uehara and Okumura, 2017).

Anisakids have also been linked to moderate and severe allergic reactions; the gastro-allergic form involves symptoms such as bronchospasm, angioedema, epigastric pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. It has been related to antigens produced only by live larvae (Alonso et al., 1999).

Although most cases of anisakiasis are concentrated in Japan (Chai et al., 2005), the number of cases reported in other parts of the world have risen in recent years. This is due in part to the growing popularity of Japanese cuisine in which raw fish is often consumed (Takabayashi et al., 2014). In Latin America, Mercado et al. reported seven cases of the disease in Chile caused by L4 forms of Pseudoterranova decipiens (Ruben Mercado et al., 1997; Rubén Mercado et al., 2001, Mercado et al., 2006, Weitzel et al., 2015), while in 1999, one of the first cases of gastric anisakiasis caused by an Anisakis spp. larva was reported in Peru (Salazar and Barriga, 1999). It is likely that anisakiasis is underdiagnosed in South America because it has a broad clinical spectrum and shares similarities with the clinical manifestations of other diseases, such as acute appendicitis, gastric ulcer, intestinal obstruction, Crohn's disease, submucosal tumors, other intestinal parasites, food allergies, and pseudo-allergies. The result of the overlapping clinical features is that the etiology of symptoms is not always known (Chopra et al., 2016, Hashimoto et al., 2017).

In Latin America, several species of fish have been described as parasitized by anisakids, including: mackerel (Trachurus murphyi) and hake (Merluccius hubbsi) in Argentina; hake (Merluccius gayi) and lorna drum (Sciaena deliciosa) in Chile and Peru; mackerel (Scomber scombrus), bluefish (Pomatomus saltatrix), hairtail (Trichiurus lepturus), red porgy (Pagrus pagrus) in Brazil; and the species of the Mugilidae family including Mugil liza, Mugil incilis, Mugil curema and of the Gerreidae family, the Eugerres plumieri in Venezuela (Espinoza, 2014, Maniscalchi Badaoui et al., 2015, Bracho-Espinoza, 2016).

The present study was carried out using samples of the flathead grey mullet fish (M. cephalus) from the city of Buenaventura, the main fishing port of Colombia on the Pacific coast. This port has an extensive coastal area with wide-ranging opportunities for commercial and artisanal fishing (Garcés Olave, 2015), the latter being one of the main sources of employment and food for the populations along the Pacific coast (AUNAP-UNIMAGDALENA, 2014, González et al., 2015).

The flathead grey mullet fish (M. cephalus) has high capture rates recorded for the last few years by artisanal fishing. It constitutes one of the main sources of protein (Díaz Castaño, 2012) as a species of significant economic importance along the Colombian coast (Jesús Olivero et al., 2013). It is characterized by a wide geographical distribution that extends along the Pacific Ocean from the coast of California in the United States to the south of Chile. The flathead grey mullet fish inhabits coastal and estuarine waters and, as a Mugilids, it is considered to be detritivore, iliophage, vegetarian, omnivore, phytophagous and zooplanctophagous (Ruiz and Vallejo, 2013). Such feeding behaviors increase the likelihood of parasite presence in the fish as a generalized phenomenon; parasites are difficult to eliminate in unprocessed fishery products, where the ecological factors that determine parasitic infections are beyond human control (Maniscalchi Badaoui et al., 2015). In this context, anisakid nematodes are the parasites of greatest interest given their implications for human health.

Therefore, the objective of this study was to determine the presence of anisakid nematode larvae in the flathead grey mullet fish (Mugil cephalus) caught in Buenaventura.

2. Materials and methods

A total of 15 flathead grey mullet fish (M. cephalus) from Buenaventura were donated by the E.A.T. Fishery Advisors company of the Colombian Fisheries Observer Programme, which has the support of the National Aquaculture and Fisheries Authority of Colombia (AUNAP).

The fish were placed in individual bags, labelled and stored in an icebox for transfer to the histology laboratory at the Universidad del Valle's Faculty of Health (in Cali, Colombia). The fish were examined externally to identify the presence of nematode parasites. They were then sectioned using scissors and tweezers and an internal organ revision was carried out under a stereoscopic microscope (Olympus SZM-45). The nematodes found were then extracted and stored in eppendorf tubes with 70% alcohol until identification.

2.1. Taxonomic identification

To observe the internal structures of the nematodes they were diaphanized in graded solutions of glycerin following the previously described protocol (Moravec et al., 1991). They were then mounted on slides for observation under a light microscope (Leica DM 750) with built-in camera (Leica DFC 295). They were photographed with magnifications of 4x, 10x and 40x using the Leica Application Suite program (LAS v 3.8).

For the classical taxonomy identification, the characteristics described by Shiraki en 1974 were observed (Table 1). To differentiate between the genera of the Anisakidae family, the following morphological characteristics were noted: excretory pore position, and presence, extent and position of the intestinal cecum and the ventricular appendix (Fukuda et al., 1988).

Table 1.

Morphological characteristics of anisakids (modified by Shiraki, 1974).

| Characteristics | Larvae Type I | Larvae Type II |

|---|---|---|

| Ventricle | Long | Short |

| Ventricle-bowel connection | Oblique | Horizontal |

| End section | Rounded | Long and conical |

| Mucron | Yes | No |

| Tooth | Short | Longer |

| Cuticle grooves | Yes | No |

The anisakids morphologically identified were counted and the prevalence was calculated following the methodology of Bush et al. (Bush et al., 1997).

2.2. Histological processing

Six anisakid nematodes were selected for the histochemical procedure. They were cut into cross sections and embedded in paraffin wax following an established protocol (Rodrigues, 2010), with modifications in the paraffin times. Paraffin blocks were sectioned (Leica RM 2245 microtome) at a thickness of 5 μm. Slides were stained with Hematoxylin-Eosin and mounted using Consult Mount (Shandon) medium for characterization.

Ethical considerations: This study was carried out in full compliance with the framework for the collection of wild species of biological diversity for purposes of non-commercial scientific research, authorized by the Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development's National Environmental Licensing Authority (Resolution 1070 of August 28, 2015). The study received approval from the Institutional Committee for the Review of Animal Ethics of the Faculty of Health, Universidad del Valle (code 004–015).

3. Results

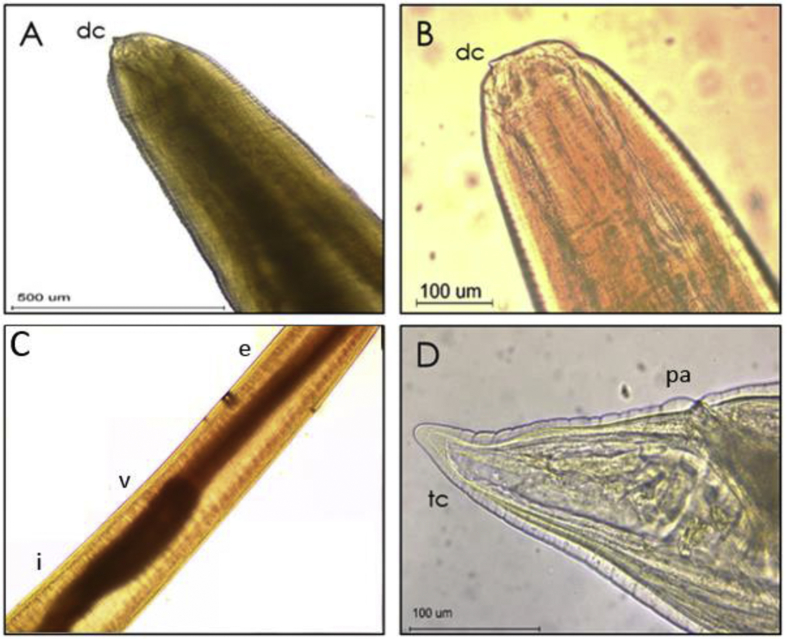

Larvae of anisakid nematodes were identified parasitizing M. cephalus. They were identified as larvae of infective stage L3 of Anisakis. The 75% the larvae were isolated of intestine and 25% in the mesentery. The larvae presented characteristics of the genus Anisakis: a whitish color with transverse cuticular grooves along the length of the body, being more pronounced at their extreme end (Fig. 1), and a well-defined mouth composed of three lips surrounding the cuticular tooth. The larvae showed a posterior end with a conical termination with absence of mucron, characteristic of Anisakis Type II larvae (Fig. 1). The Prevalence of Anisakis larvae in flathead grey mullet fish was 33%.

Fig. 1.

Larva (L3) Type II de Anisakis sp. isolated from M. cephalus. A. Front end, 10x, B. Front end 40x C. Medium portion 4x, D. Back end 40x dc. cuticular tooth e. esophagus v. ventricle i. intestine tc. conical termination, pa. anal pore.

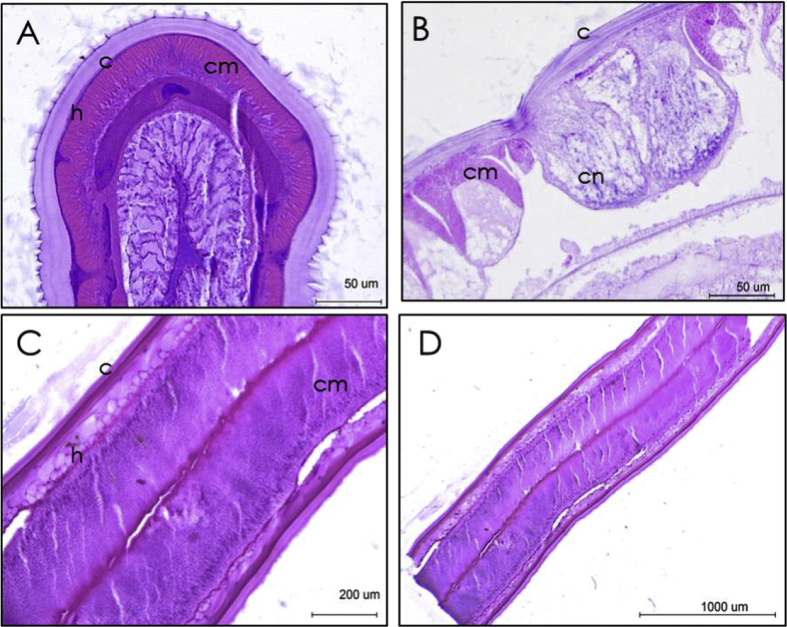

3.1. Histochemical identification for the differentiation of anatomical structures

The cuts performed at the intestinal level showed bilateral symmetry, intestinal lumen in the form of grooves (Fig. 2a), and the structural organization of the cuticle, hypodermis and muscular layer. The principal characteristic of nematodes, the cuticle, was observed in the longitudinal section, as well as the intestine (Fig. 2c and d).

Fig. 2.

Sectioned larvae (L3) of anisakid nematodes. H.E. A. and B. Cross-sections 40x, C. 40x, D. Longitudinal sections 10x c. cuticle, h. hypodermis, cm. muscular layer, cn. nerve cord.

4. Discussion

In this study, we report the presence of anisakid nematodes in the flathead grey mullet fish (Mugil cephalus) caught in the Colombian Pacific. We identified Type II larvae of the genus Anisakis, based on the structural features of the posterior extremity in conical form and with absence of mucron, as described by Shiraki (1974) (D'Amelio et al., 2000).

The genus Anisakis contains nine species and traditionally as type II larvae have been grouped three species that are A. physeteris, A. brevispiculata and A. paggiae. The precise differentiation between these three species requires the use of molecular biology techniques such as polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism (PCR-RFLP) and sequencing of the internal transcribed spacer of ribosomal DNA, however, some authors have suggested that it is possible to distinguish among these species based only on morphological criteria and that the description of Shiraki type II larvae is more accurately fitted to A. physeteris, whereas A. brevispiculata and A. paggiae could be considered as type III and type IV larvae respectively (Murata et al., 2011). According to the above, it is possible that the larvae isolated in our sample correspond to larvae of A. physeteris. However, the identification by techniques of molecular biology is very important and will be performed as a second step of our research.

In the three studies conducted in Colombia on the presence of anisakids in M. cephalus (J Olivero-Verbel et al., 2005), and (Bustos-Montes et al., 2012) reported anisakids of the genus Contracaecum in the Bay of Cartagena in the Atlantic ocean, while (Ruiz and Vallejo, 2013) identified anisakids of the genus Pseudoterranova in this same host. Additionally (J Olivero-Verbel et al., 2005), recorded rates of infection by Contracaecum sp. in seabass (Centropomus undecimalis), catfish (Sciades herzbergii) and in the fish known as the common Jurel (Caranx hipopotamos).

All the studies conducted in Colombia on the presence of anisakid nemotodes are connected geographically to the Caribbean sea, both in the sea and in continental waters (Jesús Olivero-Verbel et al., 2006); found Contracaecum sp. in Moncholo species (Hoplias malabaricus), caught in the Amazon River and in various river basins in the north of Colombia, in the Magdalena, Sinú, Dique, Cauca, Atrato and San Jorge rivers, all of which flow into the Caribbean Sea. Pardo et al. (Pardo et al., 2007, Sandra Pardo et al., 2008) recorded this genus in the Rubio fish (Salminus affinis), in the Sinú and San Jorge river basins, and in the Moncholo fish, (Hoplias malabaricus), from the marshlands of the Cienaga Grande de Lorica in Córdoba. In 2013, Lina Maria Wadnipar, established the presence of genus Contracaecum sp. in larval stage L3 in the Blanquillo fish (Sorubimcus picaudus) commercialized in San Marcos, in the department of Sucre (Wadnipar Cano, 2013). Therefore, our research constitutes the first report of the genus Anisakis in Colombia and the first study and report of anisakid nematodes in fish from the Colombian Pacific.

Diaphanization is a safe and cost-effective procedure for the identification of third stage larvae (L3) of the Anisakidae family as it enables the visualization of the form and disposition of internal organs, such as the esophagus, ventricle and intestine down the length of the nematode: these structures are determinant for the identification of the parasite within the genus Anisakis. These results are similar to those reported by Rodrigues (2010) from light microscopy, and confirmed by scanning electron microscopy (Borges et al., 2012).

The use of basic histochemical techniques with Hematoxylin-Eosin staining complemented the identification of the parasites by means of analyzing internal structures such as nerve cords, the muscular layer with its contractile and non-contractile portion, and the intestine. Authors such as Mercado, Zuloaga, Zullo et al. reported the identification of the intestine in a similar way to our study (Ruben Mercado et al., 1997, Zuloaga et al., 2004, Zullo et al., 2010). As in our study, Olivero et al. were able to describe from this same technique, anisakid nematodes causing histopathological lesions and inflammatory reactions in the hepatic tissue of the M. cephalus caught in the Cienága del Totumo, marshlands in Colombia's Caribbean coast (Jesús Olivero et al., 2013).

Although the diagnosis of anisakiasis is usually made by endoscopy, sometimes the morphological identification of the parasite is required by histochemistry, since it may be cystic in the intestine. A. simplex can penetrate the intestinal wall and enter the abdominal cavity because it is lodged in organs such as the liver, pancreas, ovary, and even pleural cavity. In a study by Couture et al. (2003) (Couture et al., 2003) of intestinal anisakiasis associated with the consumption of raw salmon from the Pacific Ocean, the evaluation of a jejunum segment revealed mucosal oedema and a submucosal abscess with marked eosinophilic response around a parasite in the third larval stage of Anisakis sp. The diagnostic morphological characteristics corresponded to an excretory gland (renette cell), lateral epidermal strings in the form of a “Y”, the absence of an apparent reproductive system and a ventricle (glandular oesophagus), characteristics that coincide with the description of the present work. Considering the previous histological description plus the absence of the lateral wing of the parasite can help differentiate the Anisakis infection from other nematodes such as Ascaris. Therefore, histochemistry aids in the workup of the differential diagnoses. Our study confirms the presence of Anisakis sp., a genus not previously reported in Colombia. Given the increasing numbers of cases of anisakiasis in the world, its recognition as a public health issue in countries such as Japan and Spain (Hocheberg and Hamen, 2010), where it is fully identified and principally associated with allergic conditions (hypersensitivity type I) and gastrointestinal food allergies, this finding may be considered vital for Colombia's public health. This is especially so if we consider that the fish is commonly consumed by the population of Buenaventura, the main fishing port of Colombia, and that the product is further distributed within the interior of the country (ASEPES, 2010, Rodríguez Salcedo et al., 2011, Díaz Castaño, 2012). During the period of 1998–2013, 1.099.568 tons of fish were caught in the Colombian Pacific region, by both industrial and artisanal fishing (AUNAP-UNIMAGDALENA, 2014). The flathead grey mullet represents one of the most important fish species in terms of biomass and its wide spatial and temporal distribution of catch (Díaz Castaño, 2012). No cases of anisakiasis in Colombia have been reported in the literature. Nonetheless, there are multiple reasons for researching anisakids and anisakiasis in this country. Among them is the global distribution of this disease, the increasing incidence of it in neighboring countries, (Salazar and Barriga, 1999, Cabrera and Trillo-Altamirano, 2004; Mercado et al., 2006), the high prevalence of infection by the Contracaecum sp. in fish from the Bay of Cartagena and the rivers Sinú and San Jorge, (Jesús Olivero-Verbel et al., 2006, Olivero et al., 2011), the annual migration of whales to the Colombian Pacific, the increased consumption of exotic dishes such as sushi, as well as the use of quick cook systems such as the microwave. This research will provide a clearer picture of the extent of this emergent parasitosis in the Colombian context (Sakanari and Mckerrow, 1989).

Also, the inadequate handling of fishery products in the stages of extraction, processing and sale, with a minimal level of processing occurring in closed, hygienic facilities, is one of the main problems facing the subsector's development, principally the lack of dock services, processing and chilling. This results in an inadequate handling of fresh and frozen fish (Rodríguez Salcedo et al., 2011), which favors the survival of pathogenic organisms, such as the anisakid nematodes.

Epidemiological studies are needed to establish whether there is a relationship between the high incidence of these diseases and the consumption of infected fish.

This research has produced important results that can be used to guide public policies in the fisheries and food health and hygiene sectors, against a possible zoonotic disease emerging in our country. It is of vital importance to establish protocols that guide health personnel and social sectors involved with anisakiasis, its consequences and its forms of diagnosis and prevention.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Declaration of submission and verification

The authors declare that this work here has not been published previously, nor is it under consideration for publication elsewhere. All authors have approved the final version of this manuscript.

Acknowledgements

Our thanks to the Administrative Department of Science, Technology and Innovation of Colombia (COLCIENCIAS), to E.A.T. Fisheries Advisors company (E.A.T. Asesorías pesqueras) of the Colombian Fisheries Observers program and to the biologists Emiliano Zambrano and Carlos Segura for donating the samples for our research. Our thanks also to the research group in Tejidos Blandos & Mineralizados (TEBLAMI) and to the histology lab of the Department of Morphology in the Faculty of Health in the Universidad del Valle, where the histochemical processing was carried out.

References

- Acha P.N., Szyfres B. PAHO. Scientific and Technical Publication; 2003. Zoonoses and Communicable Diseases Common to Man and Animals: Volume II: Chlamydioses, Rickettsioses, and Viroses.https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-5877(89)90014-7 v.2(580), 408. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso a, Moreno-Ancillo a, Daschner a, López-Serrano M.C. Dietary assessment in five cases of allergic reactions due to gastroallergic anisakiasis. Allergy. 1999;54(5):517–520. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.1999.00046.x. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1398-9995.1999.00046.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ASEPES . 2010. Caracterización del Sector Pesquero Artesanal Zona Norte del Distrito de Buenaventura. Buenaventura. [Google Scholar]

- AUNAP-UNIMAGDALENA . 2014. Caracterización de los principales artes de pesca de Colombia y reporte del consolidado del tipo y número de artes, embarcaciones y UEP's empleadas por los pescadores vinculados a la actividad pesquera. Santa Marta y Bogotá. [Google Scholar]

- Borges J.N., Cunha L.F.G., Santos H.L.C., Monteiro-Neto C., Santos C.P. Morphological and molecular diagnosis of anisakid nematode larvae from cutlassfish (trichiurus lepturus) off the coast of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e40447. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouree P., Paugam A., Petithory J.C. Anisakidosis: report of 25 cases and review of the literature. Comp. Immun. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 1995;18(2):75–84. doi: 10.1016/0147-9571(95)98848-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bracho-Espinoza H. Effects of high prevalence Anisakis in fish caught in the white coast médano, falcon state, Venezuela on the consuming population. Sci. J. Public Health. 2016;4(4):279–283. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.sjph.20160404.12 [Google Scholar]

- Bush A.O., Lafferty K.D., Lotz J.M., Shostak A.W. Parasitology meets ecology on its own terms. J. Parasitol. 1997;83(4):575–583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bustos-Montes D., Santafé-Muñoz A., Grijalba-Bendeck M., Jáuregui A., Franco-Herrera A., Sanjuan-Muñoz A. Bioecología de la lisa (Mugil incilis Hancock) en la bahía de Cispatá, Caribe colombiano. Bol. Invest. Mar. Cost. 2012;41(2):447–461. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera R., Trillo-Altamirano M.P. Anisakidosis: ¿Una zoonosis parasitaria marina desconocida o emergente en el Perú? Rev. Gastroenterol. Del Perú. 2004;24:335–342. http://www.scielo.org.pe/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1022-51292004000400006 Retrieved from. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai J.-Y., Darwin Murrell K., Lymbery A.J. Fish-borne parasitic zoonoses: status and issues. Int. J. Parasitol. 2005;35(11–12):1233–1254. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2005.07.013. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpara.2005.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chopra N., Chen C.K., Carlson I., Jackson C.C., Mavrogiorgos N. An 11-year-old boy with sudden-onset abdominal pain. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2016;63(6) doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw414. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciw414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couture C., Measures L., Gagnon J., Desbiens C. Human intestinal anisakiosis due to consumption of raw salmon. Am. J. Surg. Pathology. 2003;27(8):1167–1172. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200308000-00017. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000478-200308000-00017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Amelio S., Mathiopoulos K.D., Santos C.P., Pugachev O.N., Webb S.C., Picanço M., Paggi L. Genetic markers in ribosomal DNA for the identification of members of the genus Anisakis (Nematoda: ascaridoidea) defined by polymerase-chain-reaction-based restriction fragment length polymorphism. Int. J. Parasitol. 2000 Feb;30(2):223–226. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(99)00178-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz Castaño F. 2012. Caracterización de la pesca artesanal en el Consejo comunitario de La Plata, Bahía Málaga, Buenaventura. Pacífico Colombiano, 126. [Google Scholar]

- Espinoza H.B. Prevalence of parasitism by Anisakis in a sample of fish caught in coastline of the Golfete of Coro, Venezuela. Sci. J. Public Health. 2014;2(6):513–515. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.sjph.20140206.12 [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda T., Aji T., Tonga Y. Surface ultrastructure of larval Anisakidae (Nematoda: ascaridoidea) and its identification by mensuration. Acta Medica Okayama. 1988;42:105–116. doi: 10.18926/AMO/31010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcés Olave L. Universidad Icesi; 2015. Buenaventura Como Ciudad Puerto.http://hdl.handle.net/10906/78173 Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Ghimire R., Urban C., Gervacio B., Tong J., Kim S., Segal-Maurer S. Gastrointestinal: upper gastrointestinal bleeding due to an unusual parasite. J. Gastroenterology Hepatology. 2016;31(8) doi: 10.1111/jgh.13411. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgh.13411 1383–1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González J., Rivera R., Manjarrés-Martínez L. 2015. Aspectos socio-económicos de la pesca artesanal marina y continental en Colombia. Bogotá. [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto R., Matsuda T., Nakahori M. Small bowel anisakiasis detected by capsule endoscopy. Dig. Endosc. 2017;29:122–130. doi: 10.1111/den.12738. https://doi.org/10.1111/den.12738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hocheberg N., Hamen D. Anisakidosis: perils of the deep. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2010;51:806–812. doi: 10.1086/656238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jesús Olivero V., Bárbara Arroyo S., Ganivet Manjarrez P. Parasites and hepatic histopathological lesions in lisa (mugil incilis) from totumo mash, north of Colombia. Rev. MVZ Cordoba. 2013;18(1):3288–3294. [Google Scholar]

- Maniscalchi Badaoui M.T., Lemus-Espinoza D., Marcano Y., Nounou E., Zacarías M., Narváez N. 2015. Larvas Anisakidae en peces del género Mugil comercializados en mercados de la región costera nor-oriental e insular de Venezuela; pp. 30–38. Saber, Universidad de Oriente, Venezuela, 27(1) [Google Scholar]

- Mehlhorn H., Aspöck H. Springer; Berlin: 2008. Encyclopedia of Parasitology. [Google Scholar]

- Mercado R., Torres P., Maira J. Human case of gastric infection by a fourth larval stage of Pseudoterranova decipiens (Nematoda, Anisakidae) Rev. Saúde Pública. 1997;31(2):178–181. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89101997000200012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercado R., Torres P., Muñoz V., Apt W. Human infection by pseudoterranova decipiens (Nematoda, Anisakidae) in Chile report of seven cases. Memorias Do Inst. Oswaldo Cruz. 2001;96(5):653–655. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762001000500010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercado P.R., Torres H.P., Gil L.L.C., Goldin G.L. Anisakiasis en un paciente portadora de una pequeña hernia hiatal. Caso clínico. Rev. Medica Chile. 2006;134(12):1562–1564. doi: 10.4067/s0034-98872006001200011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moravec F., Nasincova V., Scholz T. Institute of Parasitology, Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences; Ceske Budejovice: 1991. Methods of Investigating Metazoan Parasites. Endoparasitic Helminthes. Manual for Training Course on Fish Parasites; p. 22. [Google Scholar]

- Murata R., Suzuki J., Sadamasu K., Kai A. Morphological and molecular characterization of Anisakis larvae (Nematoda: Anisakidae) in Beryx splendens from Japanese waters. Parasitol. Int. 2011;60(2):193–198. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2011.02.008. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.parint.2011.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivero-Verbel J., Baldiris-Avila R., Arroyo-Salgado B. Nematode infection in Mugil incilis (lisa) from Cartagena Bay and totumo marsh, north of Colombia. J. Parasitol. 2005;91(5):1109–1112. doi: 10.1645/GE-392R1.1. https://doi.org/10.1645/GE-392R1.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivero-Verbel J., Baldiris-Ávila R., Güette-Fernández J., Benavides-Alvarez A., Mercado-Camargo J., Arroyo-Salgado B. Contracaecum sp. infection in Hoplias malabaricus (moncholo) from rivers and marshes of Colombia. Veterinary Parasitol. 2006;140(1–2):90–97. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.03.014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.03.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olivero V.J., Caballero-Gallardo K., Arroyo-Salgado B. Nematode infection in fishfrom Cartagena Bay, north of Colombia. Veterinary Parasitol. 2011;177(1–2):119–126. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2010.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardo C.S., Mejía P.K., Navarro V.Y., Atencio G.V. Prevalencia y abundancia de Contracaecum sp. en rubio (Salminus affinis) en el río Sinú y San Jorge: descripción morfológica. Rev. MVZ Córdoba. 2007;12(1):887–896. [Google Scholar]

- Peláez M.A., Codoceo C.M., Montiel P.M., Gómez F.S., Castellano G., Herruzo J.A.S. Anisakiasis múltiple. Rev. Espanola Enfermedades Dig. 2008;100(9):581–582. doi: 10.4321/s1130-01082008000900009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezapour M., Agarwal N. You are what you eat: a case of nematode-induced eosinophilic esophagitis. ACG Case Rep. J. 2017;4:e13. doi: 10.14309/crj.2017.13. https://doi.org/10.14309/crj.2017.13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues M.V. Instituto Biologico Sao Paulo; 2010. Presenca do parasita anisaquideo em pescada (Cynoscion spp.) como ponto critico de controle na cadeia productiva do pescado comercializado na Baixada Santista. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Salcedo J., Hleap Zapata J.I., Estrada F., Clavijo Salinas J.C., Perea Velasco N. 2011. Agroindustria Pesquera en el Pacífico Colombiano: Gestión de Residuos Pecuarios en Sistema de Producción más Limpia. Palmira. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz L., Vallejo A. Parámetros de infección por nematodos de la familia Anisakidae que parasitan la lisa (Mugil incilis) en la Bahía de Cartagena (Caribe colombiano) Intropica. 2013;8(53):53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Sakanari J.A., Mckerrow J.H. Anisakiasis. 1989;2(3):278–284. doi: 10.1128/cmr.2.3.278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salazar F., Barriga E. 1999. Rev. Gastroenterol. Perú. Vol. 19 • No 4 • 1999 Anisakiasis: Presentación de un caso y revisión de la literatura; p. 19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandra Pardo C., Alan Zumaque M., Hernando Noble C., Héctor Suárez M. Contracaecum sp (Anisakidae) en el pez Hoplias malabaricus, capturado en la Ciénaga Grande de Lorica, Córdoba. Rev. MVZ Cordoba. 2008;13(2):1304–1314. [Google Scholar]

- Takabayashi T., Mochizuki T., Otani N., Nishiyama K., Ishimatsu S. Anisakiasis presenting to the ED: clinical manifestations, time course, hematologic tests, computed tomographic findings, and treatment. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2014;32(12):1485–1489. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2014.09.010. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2014.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uehara A., Okumura T. Esophageal anisakiasis mimicking gastroesophageal reflux disease. Am. J. Gastroenterology. 2017;112(4) doi: 10.1038/ajg.2016.516. https://doi.org/10.1038/ajg.2016.516 532–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadnipar Cano L.M. 2013. Evaluación de la infección parasitaria por nemátodos anisákidos en peces de interés comercial en el municipio de San Marcos (Sucre) [Google Scholar]

- Weitzel T., Sugiyama H., Yamasaki H., Ramirez C., Rosas R., Mercado R. Human infections with pseudoterranova cattani nematodes, Chile. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2015;21(10):1874–1875. doi: 10.3201/eid2110.141848. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid2110.141848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zullo A., Hassan C., Scaccianoce G., Lorenzetti R., Campo S. M. a, Morini S. Gastric anisakiasis: do not forget the clinical history! J. Gastrointest. Liver Dis. 2010;19(4):359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuloaga J., Arias J., Balibrea J.L. Anisakiasis digestiva. Aspectos de interés para el cirujano. Cirugia Española. 2004;75(1):9–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0009-739X(04)72265-4 [Google Scholar]