Abstract

Objective

We explored the burden of respiratory tract infections (RTIs) in young children with regard to day-care initiation.

Design

Longitudinal prospective birth cohort study.

Setting and methods

We recruited 1827 children for follow-up until the age of 24 months collecting diary data on RTIs and daycare. Children with continuous daycare type and complete data were divided into groups of centre-based daycare (n=299), family day care (FDC) (n=245) and home care (n=350). Using repeated measures variance analyses, we analysed days per month with symptoms of respiratory tract infection, antibiotic treatments and parental absence from work for a period of 6 months prior to and 9 months after the start of daycare.

Results

We documented a significant effect of time and type of daycare, as well as a significant interaction between them for all outcome measures. There was a rise in mean days with symptoms from 3.79 (95% CI 3.04 to 4.53) during the month preceding centre-based daycare to 10.57 (95% CI 9.35 to 11.79) at 2 months after the start of centre-based daycare, with a subsequent decrease within the following 9 months. Similar patterns with a rise and decline were observed in the use of antibiotics and parental absences. The start of FDC had weaker effects. Our findings were not changed when taking into account confounding factors.

Conclusions

Our study shows the rapid increase in respiratory infections after start of daycare and a relatively fast decline in the course of time with continued daycare. It is important to support families around the beginning of daycare.

Keywords: respiratory infections, community child health

Strength and limitations of this study.

We prospectively collected detailed day-to-day diary data on respiratory tract infections (RTIs) and related outcomes from 0 to 2 years of age in a birth cohort population, and documented daycare type and starting date.

The study design allowed us to analyse the time-dependent effects of centre-based daycare and family daycare on the days per month with symptoms of a respiratory infection in comparison with children of same age in home care.

Different confounders were taken into account, but they did not change our findings of a peak in the rate of RTIs shortly after daycare initiation, and a clear decline thereafter.

A limitation is that, due to strict requirements regarding detail in follow-up, we lost a substantial proportion of cases.

Introduction

Daycare has been known to be a major risk factor for respiratory tract infections (RTIs) in children for over 30 years.1–4 A considerable proportion of children in modern society attend daycare from the age of less than 2 years. RTIs in this age group constitute an important health problem. In addition to causing stress to children and families, they also affect transmission of pathogens to other age groups, parental absences from work with ensuing economic consequences, and rates of antimicrobial medication use with subsequent impact on resistance patterns.5–7

Within the daycare setting, factors reflecting contact rates with other children have consistently been identified as important determinants of infection risk. These factors include group sizes or size and type of the daycare facility,8–12 as well as weekly exposure time.13 A number of studies have shown children of young age to be particularly vulnerable to daycare-related effects regarding transmission of respiratory virus infections,8 13–17 and early daycare has also been linked to more severe or long-term health problems, such as recurrent acute otitis media (AOM), high numbers of antibiotic medications during early childhood, an increased lifetime risk of asthma and an increased risk of invasive pneumococcal infections.18–20 In their cross-sectional study, Hurwitz et al were the first to specifically demonstrate a lower daycare-attributable risk of RTIs with increased time after daycare initiation and thus provided data to suggest that daycare-related infection risks were not exclusively linked to the absolute age of a child.17 A large register-based study assessing RTI-related hospitalisations in under school-aged children confirmed a decrease of hospitalisations with an increased time in daycare of over 6 months.14 Only a few larger-size longitudinal studies have assessed the effects of overall exposure time to daycare in relation to RTIs,15 16 21 and loose frequency of follow-up has limited the conclusions of chronological variations. Some studies have found a protective effect of starting daycare early with regard to RTIs later in life.16 21

Given the discrepancy between potential risks and benefits of early daycare in children under the age of 2 years, detailed longitudinal studies assessing the burden of disease as a function of time before and after the start of daycare are needed. Families, child healthcare professionals and daycare providers would benefit from more detailed knowledge about the daycare-related impact of RTIs on this vulnerable age group overtime. We examined our hypothesis of a time-limited effect of daycare on RTIs in a prospectively followed birth cohort.

Methods

Study population and conduct

We used the cohort of the observational ‘Steps to the Healthy Development and Well-being of Children’ Study (The STEPS Study), which consists of 1827 children from 1797 families.22 Recruitment occurred in two stages from women with a live birth between 1 January 2008 and 31 March 2010 in the Southwest Finland Hospital District (n=9936). During the first stage, 1387 families were recruited through community midwifery services during pregnancy, and a further 410 families joined the study soon after the birth of their child. In this study, follow-up included an age frame of 0–2 years, until March 2012. We collected questionnaire-based data on family-related factors and daycare arrangements at gestational week 20 and at ages 13 months, 18 months, and 24 months, as applicable. Families kept study diaries that recorded health-related factors, the precise starting date of daycare and data from physician visits. Parents documented the child’s symptoms, antibiotic treatments and parental absence from work on a day-to-day basis in these diaries. Parents were instructed to also mark symptom-free days in the diary. We differentiated missing from negative data by excluding follow-up with no diary markings.

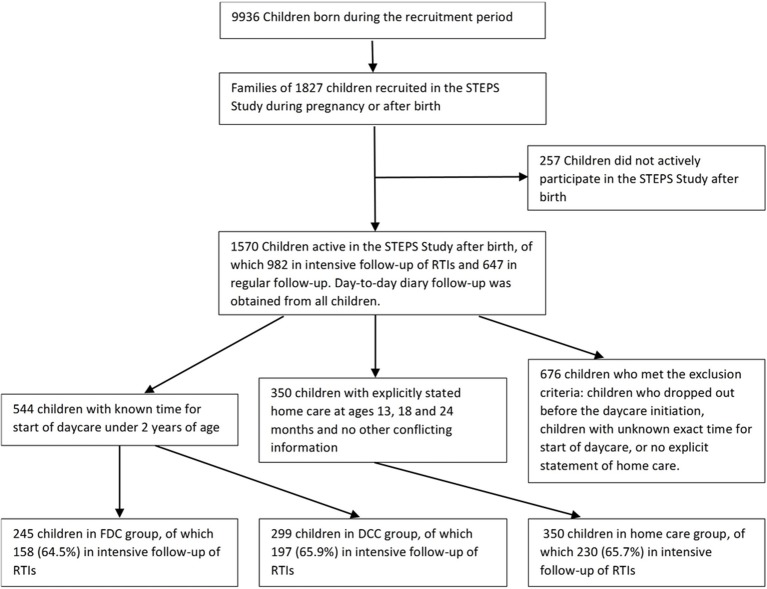

Families attended our nurse-led study clinic when the child was 2 and 13 months of age. During RTIs part of the cohort (n=982) were also followed up by our physician-led study clinic.23 Recruitment of children to our study is shown in figure 1. Exclusion criteria for this study constituted discontinued follow-up before daycare initiation, insufficient information on daycare arrangements or a lack of information on home care. The Ethics Committee of the Hospital District of Southwest Finland approved the study protocol. The parents of the participating children gave their written, informed consent.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the recruitment and follow-up of study children.

Daycare attendance

Children were categorised into three different groups according to daycare arrangements: children cared for by parents or relatives (home care group), children attending family daycare (FDC) and children attending daycare centres (DCC). In this study, FDC was defined as daycare provided by a trained carer in her or his home, or in the children’s homes using a rotational system. According to local regulations, FDC group sizes included not more than five children. In rare cases, carers worked together forming a common nursery. Since group sizes tended to be relatively small in those nurseries, these children were included in the FDC group. DCCs were defined by larger-group, centre-based care provided by several professional carers. FDC and care in DCCs were provided either by the municipality or on a private basis.

Outcomes

The outcomes of the study were symptoms of RTIs (cough, rhinorrhoea, fever or wheeze), consumption of antibiotic medication and parental absence from work as recorded on a day-to-day basis in the study diaries. Antibiotic medications prescribed for any reason were included, but the main indication was AOM. Any parental absence from work due to the child’s illness was recorded, and reasons were not limited to RTIs. Final outcome measures constituted days per month with RTI symptoms (sick days), antibiotic medication and parental absence from work.

Confounding factors

The following potential confounders were taken into consideration: sex, siblings, season of year at start of daycare, asthma in the parents, pets (cats or dogs at home), maternal postsecondary education and family monthly net income.24–26 There was only a small proportion of families with known smoking in either one of the parents (127 within the home care, FDC and DCC groups), and since our results indicated reporting bias, this variable was excluded from the analyses.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were carried out using SAS V.9.4. In all our analyses p values less than 0.05 were regarded as statistically significant. In the first step, outcome variables were calculated as days per month for each child and aligned in a time sequence relating to the beginning of daycare. Follow-up included a time of 6 months previous to and 9 months after the beginning of daycare. Since children commenced daycare at different ages, this meant that not all data of individual follow-up related to the fixed age frame of 0–2 years. Data from outside this age range were excluded from the analysis using the SAS MIXED procedure. For the home care group, the equivalent age range of follow-up was calculated using the mean age of starting daycare in the FDC and DCC groups (mean starting age at 15 months), and resulted in a follow-up period from 9 to 24 months (6 months prior to and 9 months after the mean start of daycare at 15 months).

If a child finished daycare during follow-up for any reason, data after discontinuation of daycare were selectively excluded by the SAS MIXED procedure.

After comparisons using independent sample t-tests and variance analyses, data were analysed by repeated measures variance analysis comparing all three groups for type of daycare and time, as well as their interaction. In a second step, we compared the difference of least square means between all pairs of analysed months and determined the shortest time intervals during which statistically significant differences in our outcome measures could be observed. The shortest time for a rise of outcome measures was determined from the last month prior to starting daycare and for a decline from the peak of each outcome variable. Although the distributions of monthly outcome variables (sick days, days with antibiotic treatment and parental absence from work) were skewed in our analyses (coefficient of skewness up to 2.4 and kurtosis 7.6), the pairwise difference variables followed approximately a normal distribution.

In a third step, repeated measures variance analysis was repeated according to the previous model, but stratifying according to individual confounding factors.

Sensitivity testing was performed by additional variance analyses excluding all data from children who finished daycare during follow-up.

Results

Figure 1 shows numbers of children within follow-up. Within our cohort of 1570 children in active follow-up, 276 (21.8%) of 1264 children with data on daycare arrangements at age 13 months attended daycare (11.7% in DCC, 10.1% in FDC) and 593 (55.0%) of 1079 children attended daycare at the age of 24 months (29.5% in DCC and 25.0% in FDC). At all ages the vast majority of children in daycare spent over 5 hours per day at daycare (88.5% at age 13 months and 91.6% at age 24 months). Group sizes were clearly smaller for children attending FDC as compared with DCC, with 88.3% (at 13 months) to 82.7% (at 24 months) of families reporting a group size of less than five children per group. In DCC group sizes were variable with the following results for the ages of 13 months (and 24 months): less than five children for 2.0%, 5–15 children for 86.8%, over 15 children for 11.1% (less than five children for 1.4%, 5–15 children for 87.8%, over 15 children for 10.9%).

Missing knowledge regarding the exact time of start of daycare, or earlier discontinuation of the study, led to a drop-out of a large part of cases, but these drop-outs occurred mostly before the start of daycare (figure 1). Baseline characteristics and mean (SD) values of outcome measures of children included in the analysis are shown in table 1. Mean age at the beginning of daycare was 15 months (SD 4.1). Start of daycare (FDC or DCC) occurred in 38.2% of cases during fall–winter (October to March) and in 61.8% during spring-summer (April to September). Over the whole follow-up period during daycare, children in DCC had only slightly more sick days per month (mean 5.54, SD 4.07) compared with children in FDC (mean 4.85, SD 3.49) or home care (mean 4.80, SD 3.39). There was no significant difference in days with antibiotic treatment. Parental absences from work could not be compared with the home care group, since the stay-at-home parent was not employed, and could therefore not be absent from work. Discontinuous daycare was observed in only a minority of children (11 children in FDC and 13 children in DCC). The results remained consistent in analyses performed without data from children who finished daycare during follow-up.

Table 1.

Comparisons of baseline variables and outcome measures according to daycare type

| Type of daycare | ||||

| Home care (n=350) | Family daycare (n=245) | Daycare centre (n=299) | p | |

| Age at the beginning of daycare, mean (SD) | NA | 1.24 (0.37) | 1.28 (0.35) | 0.25* |

| Sex | ||||

| Males, n (%) | 172 (49.1%) | 124 (50.6%) | 162 (54.1%) | 0.4† |

| Born preterm (<37 gestational weeks), n (%) | 18 (5.0%) | 7 (2.9%) | 14 (4.7%) | 0.38† |

| Sick days per month, mean (SD) | 4.80 (3.39) | 4.85 (3.49) | 5.54 (4.07) | 0.03‡ |

| Days with antibiotic treatment per month, mean (SD) | 0.74 (1.41) | 0.82 (1.36) | 0.93 (1.14) | 0.21‡ |

| Days with parental absences from work per month, mean (SD) | NA | 0.31 (0.38) | 0.36 (0.45) | 0.17* |

*Independent sample t-test.

†χ2 test.

‡Unadjusted variance analysis.

DCC, daycare centres; FDC, family daycare; NA, not applicable.

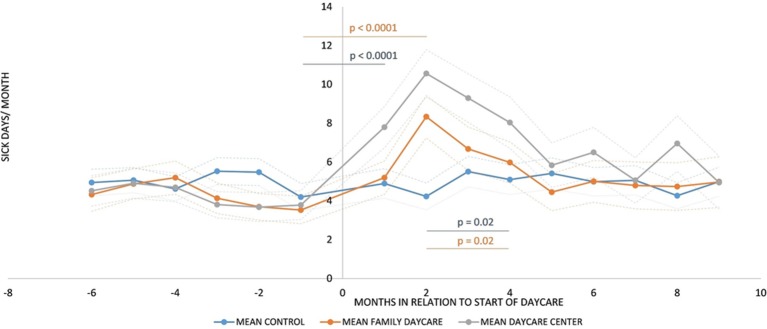

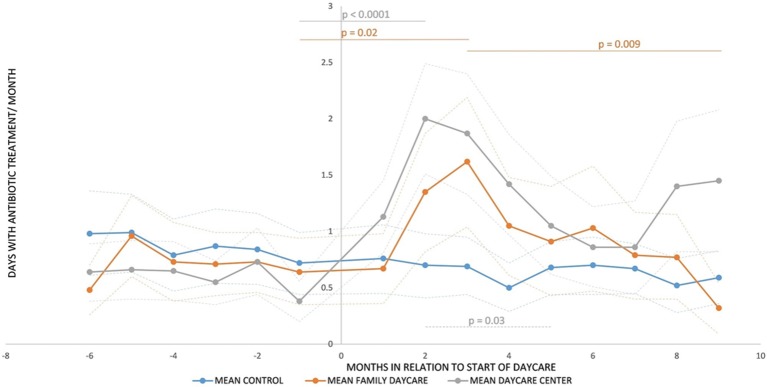

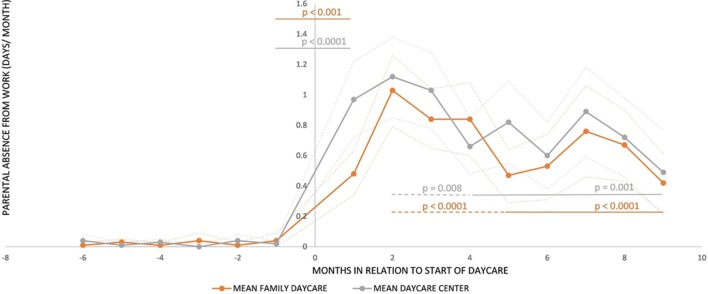

There was a peak of mean sick days per month at 2 months after the start of daycare for both FDC and DCC (figure 2). The rise in sick days was stronger for the DCC group than for the FDC group. We observed increases from 3.53 mean sick days (95% CI 2.83 to 4.24) during the month prior to the start of daycare to 8.34 mean sick days per month (95% CI 7.25 to 9.43) for the FDC group and from 3.79 (95% CI 3.04 to 4.53) mean sick days prior to the start of daycare to 10.57 (95% CI 9.35 to 11.79) mean sick days per month for the DCC group. For both of these groups, the rise of outcome measures was a transient phenomenon; sick days were comparable to the home care group at 5 months after the start of daycare. Antibiotic use (figure 3) and parental absences from work because of children’s illnesses (figure 4) rose and declined according to a pattern similar to that observed in sick days in relation to the start of daycare, although this decline was less pronounced compared with sick days.

Figure 2.

Means and 95% CIs (dashed lines) of sick days per month according to daycare groups in relation to start of daycare. Negative months denote the period prior to start of daycare. Horizontal lines indicate the shortest time for a significant rise (decline) from the last month prior to starting daycare (from the peak month).

Figure 3.

Means and 95% CIs (dashed lines) of days with antibiotic treatment per month according to daycare groups in relation to start of daycare. Negative months denote the period prior to start of daycare. Horizontal lines indicate the shortest time for a significant rise (decline) from the last month prior to starting daycare (from the peak month). Dashed lines: transiently below the significance level.

Figure 4.

Means and 95% CIs (dashed lines) of days with parental absence from work per month according to daycare groups in relation to start of daycare. Negative months denote the period prior to start of daycare. Horizontal lines indicate the shortest time for a significant rise (decline) from the last month prior to starting daycare (from the peak month). Dashed lines: transiently below the significance level.

The rise in sick days (figure 2) and antibiotic use (figure 3) was more rapid among children starting DCC than in those starting FDC. Within the home care group, there were no significant findings in pairwise comparisons between months.

In repeated measures variance analyses, there was a significant overall effect for time and type of daycare and their interaction for all outcome measures. This interaction showed the above described pattern of rise and decline, which was strongest for the DCC group and weaker for the FDC group. Within the home care group there was no such pattern, but variation was observed in the frequency of sick days per month overtime. When analysing sick days and antibiotic use between different types of daycare without the aspect of time, levels of these outcome measures were higher in the DCC group in comparison to the home care group (p<0.001 for both measures) and FDC group (p<0.001 and p=0.04, respectively). There were no significant differences between the FDC and home care group.

The presence of older siblings in the family, higher postsecondary education in mothers and higher family income were all associated with a higher burden of disease (table 2).

Table 2.

Effects of confounding factors on the rates of respiratory tract infection (RTI) symptoms (sick days) according to daycare type

| Type of day care | ||||||||

| Home care | Family day care | Day-care centre | ||||||

| n/N (%) | Sick days per month, mean (SD) | n/N (%) | Sick days per month, mean (SD) | n/N (%) | Sick days per month, mean (SD) | p* | p for interaction with mode of day care | |

| Older siblings | 0.02 | <0.001 | ||||||

| Yes | 162/350 (46.3) | 5.55 (3.72) | 99/245 (40.4) | 5.26 (3.33) | 132/299 (44.1) | 5.10 (3.72) | ||

| No | 188/350 (53.7) | 4.16 (2.95) | 146/245 (59.6) | 4.58 (3.59) | 167/299 (55.9) | 5.88 (4.31) | ||

| Higher postsecondary education in mother | 0.009 | 0.27 | ||||||

| Yes | 211/341 (61.9) | 5.12 (3.53) | 161/239 (67.4) | 5.12 (3.72) | 203/293 (69.3) | 5.66 (3.75) | ||

| No | 130/341 (38.1) | 4.40 (3.17) | 78/239 (32.6) | 4.23 (2.97) | 90/293 (30.7) | 5.45 (4.79) | ||

| Family net income under €2000 per month | 0.005 | 0.37 | ||||||

| Yes | 83/343 (24.2) | 4.15 (3.28) | 33/239 (13.8) | 3.43 (2.75) | 56/294 (19.0) | 5.29 (3.39) | ||

| No | 260/343 (75.8) | 5.03 (3.43) | 206/239 (86.1) | 5.04 (3.57) | 238/294 (81.0) | 5.64 (4.23) | ||

| Start of daycare during fall–winter (October–March) | 0.39 | 0.61 | ||||||

| Yes | NA | NA | 100/245 (40.8) | 4.90 (3.15) | 108/299 (36.1) | 5.69 (4.21) | ||

| No | NA | NA | 145/245 (59.2) | 4.82 (3.73) | 191/299 (63.9) | 5.45 (4.0) | ||

| Asthma in parents | 0.95 | 0.72 | ||||||

| Yes | 35/340 (10.3) | 4.65 (3.26) | 26/234 (11.1) | 5.54 (4.0) | 30/287 (10.5) | 5.83 (4.25) | ||

| No | 305/340 (89.7) | 4.86 (3.43) | 208/234 (88.9) | 4.76 (3.45) | 257/287 (89.5) | 5.56 (4.08) | ||

| Cat or dog at home | 0.31 | 0.23 | ||||||

| Yes | 94/295 (31.9) | 4.43 (3.07) | 80/196 (40.8) | 4.83 (3.07) | 57/219 (26.0) | 5.80 (4.28) | ||

| No | 201/295 (68.1) | 5.14 (3.48) | 116/196 (59.2) | 4.92 (3.14) | 162/219 (74.0) | 5.68 (3.66) | ||

*By univariate analysis, regardless of day care type.

n/N, number of children per number of those with data available; NA, not applicable; RTI, respiratory tract infection.

In repeated measures variance analyses stratified according to confounding factors, associations remained (p<0.001 for the effect of time and p<0.001 for daycare type for all analyses regarding sick days, except for those with parental asthma, where p=0.004 for daycare type). Online supplementary figures S1 and S2 illustrate the association of start of daycare with RTIs in children stratified according to the presence of siblings and maternal postsecondary education. For children without older siblings, the rise of sick days per month after start of daycare was more pronounced than for those with older siblings.

bmjopen-2016-014635supp001.pdf (297.2KB, pdf)

Discussion

In this study, there was a strong, but temporally limited effect of daycare initiation on the rate of RTIs. This was strongest for the DCC group and weaker for the FDC group. An effect of overall time in daycare,14 15 17 as well as daycare type, on infections has been documented in previous studies.8 10 11 13 Our study specifically focused on RTI dynamics around the start of daycare.

We analysed three main outcome measures. After showing a peak, the rate of sick days returned near to baseline within our 9-month follow-up period from the start of daycare; for antibiotic use there was more scatter with a less pronounced decline, and parental absence from work did not return to baseline, which was to be expected due to the fact that both parents tend to be at work after the start of daycare. Consideration of confounders did not change our findings. The effect of older siblings on infections in relation to daycare has been previously described,17 and our findings are in line with previous results. The effects of virus epidemics and season of year were minimised in our study setting, but they cannot be completely excluded.

We consider the main strength of our study the detailed follow-up on a day-to-day basis for a relatively large number of cases and in chronological relation to the start of daycare. Previous cohort studies mostly assessed data from follow-up with intervals of months or longer periods and without information on the exact starting point of daycare, such that detailed chronological analyses for the time around daycare initiation could not be carried out.13 15 16 26 Retrospective collection of data relating to symptoms poses problems in some other studies, since it strongly relies on parents’ memories.

There are some limitations to our study. Exposure to daycare was documented as hours per day only. However, irregular daycare was rare and high daily exposure can be extrapolated to high weekly or monthly exposure. Follow-up time was relatively short although sufficient to demonstrate the above described effects. Outcome measures were based on self-reported data and are thus subject to bias. Daily diary-keeping demanded regular participation of families, although diaries were concise and easily completed. There were several indicators that for the small number of families with known smoking, diaries were not completed as comprehensively as in the rest of the cohort, so that we had to exclude parental smoking as a confounder from our study. The group with more detailed follow-up during infections had access to our medical services free of charge and thus may have been more motivated to accurately document all experienced events. Inclusion into this group was offered to all families without any selection criteria.

Due to strict requirements for comprehensive follow-up, we lost a considerable proportion of cases. For all cases lost, missing data were collected before or at the time of daycare initiation, which means that the majority of drop-outs occurred before the critical follow-up after daycare initiation. This decreases the potential effect of exclusion-related bias on our results. In order to screen for bias, a comparison of background variables was performed for non-responders and responders at 13 months of age, and there were only minor differences between groups.22

Our cohort children had less often older siblings than all eligible children, and their mothers had higher education and occupational status.22 Otherwise our cohort represents the Southwest Finnish population well. Although lower socioeconomic class has traditionally been linked to an increased rate of infectious diseases,27 a Swedish study found an association between low social status, smaller likelihood to be cared for in out-of-home care, and lesser consumption of medical services.28 Within our cohort, social status, as indicated by maternal education and family income, was also reflected by a higher rate of RTIs, but this did not affect our findings relating to daycare.

Conclusion

In this longitudinal cohort study, the respiratory infectious disease burden was clearly related to out-of-home care, but it decreased already within a short follow-up time of 9 months after the start of daycare. Our findings demonstrate a clearly limited temporal impact of daycare-related RTIs in early childhood, which has implications on a correctly focused approach when supporting families with small children. Families, daycare providers and paediatricians may be reassured of the transient nature of increased RTIs after the start of daycare.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

AS listed in the manuscript

Acknowledgments

We are extremely grateful to all the families who took part in this study, the midwives for their help in recruiting them and the whole STEPS Study team, which includes our research physicians and study nurses.

Footnotes

Contributors: LS-H contributed to the conception and design, the clinical follow-up and data collection, carried out data analyses, drafted the initial manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. LT and SK contributed to the conception and design, the clinical follow-up and data collection, reviewed and revised the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. AK contributed to the conception and design, coordinated data collection, carried out data analyses, reviewed and revised the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. VP conceptualised and designed the study, coordinated and supervised data collection and analyses, reviewed and revised the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted.

Funding: All phases of this study were supported by the University of Turku; the Åbo Akademi University; the Turku University Hospital; the Academy of Finland (grant nos 123571, 140251 and 277535); the Foundation for Paediatric Research, Finland, and Research Funds from Specified Government Transfers, Hospital District of Southwest Finland. LS-H was also supported by the Turku University Foundation.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Ethics Committee of the Hospital District of Southwest Finland.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Requests for unpublished data are handled by the directory board of the STEPS Study.

References

- 1. Doyle AB. Incidence of illness in early group and family day-care. Pediatrics 1976;58:607–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Strangert K. Respiratory illness in preschool children with different forms of day care. Pediatrics 1976;57:191–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wald ER, Dashefsky B, Byers C, et al. . Frequency and severity of infections in day care. J Pediatr 1988;112:540–6. 10.1016/S0022-3476(88)80164-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fleming DW, Cochi SL, Hightower AW, et al. . Childhood upper respiratory tract infections: to what degree is incidence affected by day-care attendance? Pediatrics 1987;79:55–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Nurmi T, Salminen E, Pönkä A. Infections and other illnesses of children in day-care centers in Helsinki. II: the economic losses. Infection 1991;19:331–5. 10.1007/BF01645358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Holmes SJ, Morrow AL, Pickering LK. Child-care practices: effects of social change on the epidemiology of infectious diseases and antibiotic resistance. Epidemiol Rev 1996;18:10–28. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a017913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Thrane N, Olesen C, Md JT, et al. . Influence of day care attendance on the use of systemic antibiotics in 0- to 2-year-old children. Pediatrics 2001;107:e76 10.1542/peds.107.5.e76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Louhiala PJ, Jaakkola N, Ruotsalainen R, et al. . Form of day care and respiratory infections among Finnish children. Am J Public Health 1995;85:1109–12. 10.2105/AJPH.85.8_Pt_1.1109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rovers MM, Zielhuis GA, Ingels K, et al. . Day-care and otitis media in young children: a critical overview. Eur J Pediatr 1999;158:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Marx J, Osguthorpe JD, Parsons G. Day care and the incidence of otitis media in young children. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1995;112:695–9. 10.1016/S0194-5998(95)70178-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hardy AM, Fowler MG. Child care arrangements and repeated ear infections in young children. Am J Public Health 1993;83:1321–5. 10.2105/AJPH.83.9.1321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Collet JP, Burtin P, Gillet J, et al. . Risk of infectious diseases in children attending different types of day-care setting. Epicrèche Research Group. Respiration 1994;61(Suppl 1):16–19. 10.1159/000196375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Early Child Care Research Network. Child care and common communicable illnesses: results from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Study of Early Child Care. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2001;155:481–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kamper-Jørgensen M, Wohlfahrt J, Simonsen J, et al. . Population-based study of the impact of childcare attendance on hospitalizations for acute respiratory infections. Pediatrics 2006;118:1439–46. 10.1542/peds.2006-0373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zutavern A, Rzehak P, Brockow I, et al. . Day care in relation to respiratory-tract and gastrointestinal infections in a German birth cohort study. Acta Paediatr 2007;96:1494–9. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00412.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cote SM, Petitclerc A, Raynault M-F, et al. . Short- and Long-term risk of infections as a function of group child care attendance. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2010;164:1132–7. 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hurwitz ES, Gunn WJ, Pinsky PF, et al. . Risk of respiratory illness associated with day-care attendance: a nationwide study. Pediatrics 1991;87:62–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nafstad P, Hagen JA, Oie L, et al. . Day care centers and respiratory health. Pediatrics 1999;103:753–8. 10.1542/peds.103.4.753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. de Hoog ML, Venekamp RP, van der Ent CK, et al. . Impact of early daycare on healthcare resource use related to upper respiratory tract infections during childhood: prospective WHISTLER cohort study. BMC Med 2014;12:107. 10.1186/1741-7015-12-107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Takala AK, Jero J, Kela E, et al. . Risk factors for primary invasive pneumococcal disease among children in Finland. JAMA 1995;273:859–64. 10.1001/jama.1995.03520350041026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ball TM, Holberg CJ, Aldous MB, et al. . Influence of attendance at day care on the common cold from birth through 13 years of age. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2002;156:121–6. 10.1001/archpedi.156.2.121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lagström H, Rautava P, Kaljonen A, et al. . Cohort profile: steps to the healthy development and well-being of children (the STEPS Study). Int J Epidemiol 2013;42:1273–84. 10.1093/ije/dys150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Toivonen L, Schuez-Havupalo L, Karppinen S, et al. . Rhinovirus infections in the first 2 years of life. Pediatrics 2016;138:1309. 10.1542/peds.2016-1309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hatakka K, Piirainen L, Pohjavuori S, et al. . Factors associated with acute respiratory illness in day care children. Scand J Infect Dis 2010;42:704–11. 10.3109/00365548.2010.483476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Koopman LP, Smit HA, Heijnen ML, et al. . Respiratory infections in infants: interaction of parental allergy, child care, and siblings-- the PIAMA study. Pediatrics 2001;108:943–8. 10.1542/peds.108.4.943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Celedon JC, Litonjua AA, Weiss ST, et al. . Day care attendance in the first year of life and illnesses of the upper and lower respiratory tract in children with a familial history of atopy. Pediatrics 1999;104:495–500. 10.1542/peds.104.3.495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cohen S. Social status and susceptibility to respiratory infections. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1999;896:246–53. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08119.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hjern A, Haglund B, Rasmussen F, et al. . Socio-economic differences in daycare arrangements and use of medical care and antibiotics in Swedish preschool children. Acta Paediatr 2000;89:1250–6. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2000.tb00744.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-014635supp001.pdf (297.2KB, pdf)