A highly efficient kinetic resolution of racemic 2-substituted 1,2-dihydroquinolines via asymmetric Cu-catalyzed borylation has been realized for the first time to afford chiral 3-boryl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinolines and recover 2-substituted 1,2-dihydroquinolines with excellent enantioselectivities and selectivity factors of up to 569.

A highly efficient kinetic resolution of racemic 2-substituted 1,2-dihydroquinolines via asymmetric Cu-catalyzed borylation has been realized for the first time to afford chiral 3-boryl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinolines and recover 2-substituted 1,2-dihydroquinolines with excellent enantioselectivities and selectivity factors of up to 569.

Abstract

A highly efficient kinetic resolution of racemic 2-substituted 1,2-dihydroquinolines via asymmetric Cu-catalyzed borylation has been realized for the first time. Under mild conditions, a variety of chiral 3-boryl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinolines containing two vicinal stereogenic centers as well as the recovered 2-substituted 1,2-dihydroquinolines were afforded after 30 minutes in high yields with up to 99% ee (dr > 99 : 1) and over 98% ee values, respectively, corresponding to kinetic selectivity factors of up to 569. Moreover, this protocol was successfully applied to the asymmetric synthesis of a selective estrogen receptor modulator.

Introduction

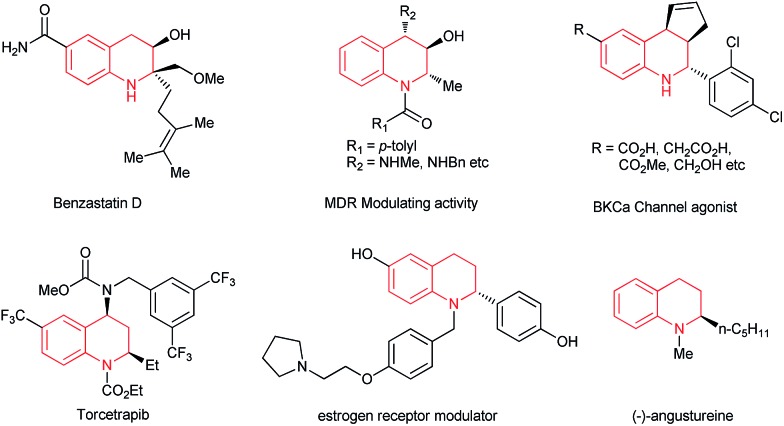

The optically active 1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline framework constitutes a key synthetic intermediate in organic synthesis and is a privileged structural motif in a broad range of natural products, biologically active compounds,1 and pharmaceuticals such as benzastatin D, angustureine and the antihypercholesterolemia drug torcetrapib (Fig. 1).2 Therefore, optically active tetrahydroquinolines have elicited much interest, and a great deal of effort has been devoted to the development of convenient and general synthetic approaches,1,3 including intramolecular cyclization by Friedel–Crafts reactions, hydroamination, allylic amination or aza-Michael addition,4 asymmetric hydrogenation of 2-substituted quinolines,5–8 and enantioselective transition metal-catalyzed nucleophilic addition of quinolinium salts.9–11

Fig. 1. Selected bioactive compounds containing tetrahydroquinolines.

On the other hand, chiral organoboron compounds, because of their utility in C–C and C–heteroatom bond formation, have greatly expanded the potential applications in organic chemistry, specifically as key intermediates in asymmetric synthesis. The direct catalytic enantioselective synthesis of organoboron compounds can be achieved by a number of reported methods,12 such as hydroboration,13 diboration,14 arylborylation,15 conjugate boron addition,16 and allylic substitution.17 Among these approaches, transition metal-catalyzed boration of prochiral C–C multiple bonds has recently attracted much interest in chemistry.12c,18 For instance, Ito and coworkers made an outstanding contribution to the Cu-catalyzed asymmetric hydroboration reaction and recently reported the stepwise dearomatization and enantioselective borylation of pyridines and quinolines with excellent enantioselectivities.18b,c

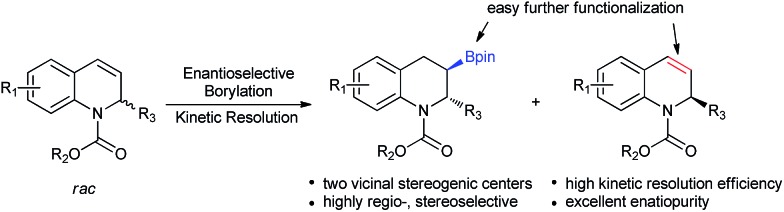

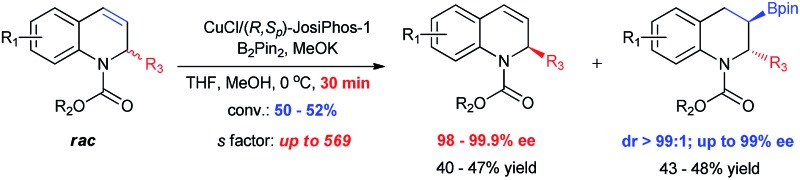

Kinetic resolution, which provides a simple and efficient way to access both the chiral products and recover the starting materials, has attracted considerable attention from academy and industry.19 Most recently, several exciting developments in kinetic resolution have been reported.20 Transition metal-catalyzed allylic substitution, C–H iodination, C–H olefination, C–H cross-coupling and C–P coupling reactions have been successfully applied to kinetic resolution.21 In addition, tremendous efforts have also been made for the development of organocatalysts, such as phase-transfer catalysts, N-heterocyclic carbenes and Brønsted acids, for kinetic resolution.22 Despite this significant progress, to date, the number of reactions, catalysts and substrates suitable for kinetic resolution is still limited and a higher resolution efficiency is highly required. To the best of our knowledge, thus far, kinetic resolution via asymmetric borylation has not been explored. Therefore, we hypothesized the kinetic resolution of 2-substituted 1,2-dihydroquinolines via Cu-catalyzed borylation (Scheme 1), which can simultaneously afford both chiral organoboron compounds bearing two vicinal stereogenic centers and the enantiomerically enriched recovered 2-substituted 1,2-dihydroquinolines,23 which can be transformed to the corresponding tetrahydroquinolines by simple methods. Herein, we present the kinetic resolution of 2-substituted 1,2-dihydroquinolines via Cu-catalyzed borylation for the first time. With kinetic resolution selectivity factors of up to 569, the chiral organoboron compounds were obtained with excellent diastereoselectivity and enantioselectivities (dr > 99 : 1 and up to 99% ee), while the unreacted 2-substituted 1,2-dihydroquinolines were recovered with extremely high enantiopurities (98–99.9% ee) and in high yields.

Scheme 1. Kinetic resolution of 1,2-dihydroquinolines via Cu-catalyzed borylation.

Results and discussion

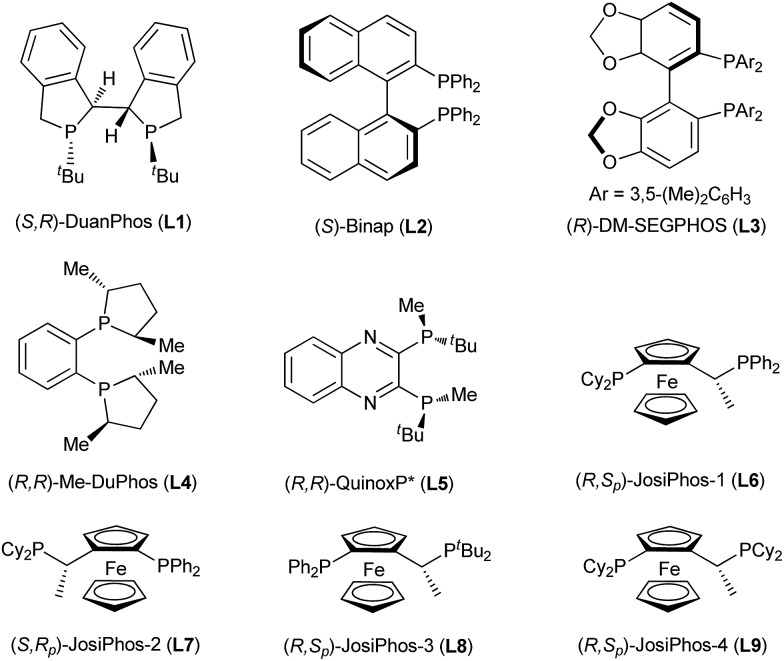

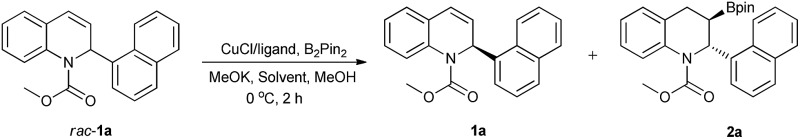

The asymmetric borylation/kinetic resolution of racemic methyl 2-(naphthalene-1-yl)quinoline-1(2H)-carboxylate (rac-1a) was initially evaluated with B2pin2 in THF at 0 °C, catalyzed by a complex formed from CuCl and (S,R)-DuanPhos in the presence of MeOK and MeOH as additives (Table 1, entry 1). We were pleased to find that the borylation product 2a as a single diastereomer (dr > 99 : 1) and the recovered 1a were obtained with 60% ee and 98% ee, respectively, corresponding to a selectivity factor (s) of 17.19a Although the determination of the conversion-independent selectivity factor (s = ln[(1 – C) (1 – ee1a)]/ln[(1 – C) (1 + ee1a)]) was not straightforward due to the product containing two stereogenic centers, the extraordinary diastereoselectivity (dr > 99 : 1) allowed for the calculation of the true selectivity factor.22h Then, we examined the effect of solvents including toluene, DME and DCE (entries 2–4). According to the enantioselectivity and efficiency of the kinetic resolution, THF was a better choice albeit slightly higher ee values of the recovered 1a and borylation product 2a were observed in toluene and DME, respectively. The screening of various chiral ligands, shown in Fig. 2, which are often used in Cu-catalyzed asymmetric boration reactions of C–C double bonds was subsequently carried out (entries 5–12). The use of (S)-Binap could provide good enantioselectivities for both the borylation product and the recovered starting material (entry 5), whereas (R)-DM-SEGPHOS, (R,R)-Me-Duphos and (R,R)-QuinoxP* afforded the recovered 1a with very poor ee values, albeit with moderate to high enantioselectivities for the borylation product 2a (entries 6–8). To our delight, in addition to a satisfactory conversion, (R,S p)-JosiPhos-1 dramatically increased the enantioselectivity of both product 2a and recovered 1a to 97% ee and 99.4% ee, respectively with an outstanding selectivity factor (s) of 251 (entry 9). Some other similar ligands proved to be inefficient for this kinetic resolution, with very poor enantioselectivity and selectivity factors (entries 10–12). In the end, the optimal reaction conditions were selected as CuCl/(R,S p)-JosiPhos-1/MeOK/THF.

Table 1. Optimization of reaction conditions a .

| ||||||

| Entry | Ligand | Solvent | Conv b (%) | 1a | 2a | S e |

| ee c (%) | ee c , d (%) | |||||

| 1 | L1 | THF | 64 | 98 | 60 | 17 |

| 2 | L1 | Toluene | 71 | 99 | 42 | 11 |

| 3 | L1 | DME | 43 | 63 | 74 | 12 |

| 4 | L1 | DCE | 44 | 45 | 57 | 5 |

| 5 | L2 | THF | 53 | 92 | 83 | 29 |

| 6 | L3 | THF | 20 | 7 | 50 | 1 |

| 7 | L4 | THF | 21 | 24 | 88 | 25 |

| 8 | L5 | THF | 29 | 38 | 95 | 40 |

| 9 | L6 | THF | 51 | 99.4 | 97 | 251 |

| 10 | L7 | THF | 37 | 37 | 64 | 6 |

| 11 | L8 | THF | 39 | 23 | 36 | 3 |

| 12 | L9 | THF | 31 | 5 | 31 | 2 |

aReaction conditions: CuCl (0.025 mmol), ligand (0.025 mmol), rac-1a (0.5 mmol), B2Pin2 (0.6 mmol), MeOK (0.1 mmol), solvent (1.5 mL) MeOH (1.0 mmol), 0 °C, 2 h.

bCalculated conversion, C = ee1a/(ee1a + ee2a).

cDetermined by chiral HPLC and SFC analysis.

dDiastereomeric ratio (dr) > 99 : 1 (determined by 1H NMR).

eSelectivity factor (s) = ln[(1 – C) (1 – ee1a)]/ln[(1 – C) (1 + ee1a)].

Fig. 2. Structures of the phosphine ligands screened.

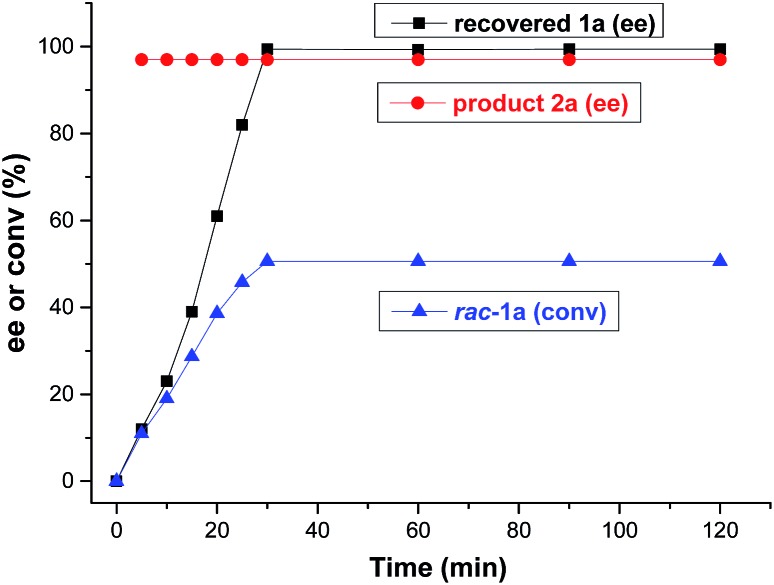

In the ideal kinetic resolution of a racemate, only one of the two enantiomers reacts, and the other one is recovered (i.e., C = 50%). To explore the kinetic resolution of rac-1a in more detail, the ee values of product 2a and recovered 1a, and the conversion of rac-1a were monitored from the start of the reaction (Fig. 3). Remarkably, the enantiomeric excess of recovered 1a increased from 0 to 99.4% after 30 minutes and remained constant thereafter. Moreover, the borylation product 2a was afforded with an almost unaltered excellent enantioselectivity of 97% ee, even if the kinetic resolution lasted for 2 hours. These results revealed that the kinetic resolution of rac-1a via Cu-catalyzed borylation was highly effective and almost perfect. In order to confirm that only one enantiomer reacts, we performed the borylation of recovered 1a (99.4% ee) under identical reaction conditions and, as expected, almost no borylated product was observed.

Fig. 3. Plot of the enantioselectivity of product 2a and recovered 1a, and the conversion of rac-1a against reaction time.

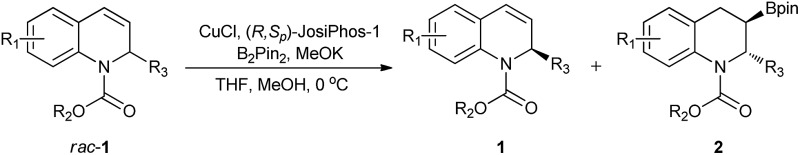

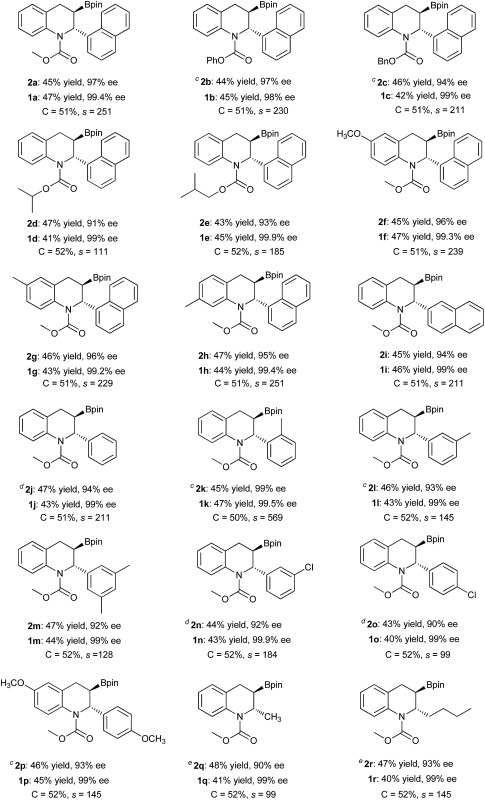

Under the optimized reaction conditions, the kinetic resolution of various racemic 2-substituted 1,2-dihydroquinolines (rac-1) via asymmetric Cu-catalyzed borylation was investigated (Table 2). All of the racemic 1,2-dihydroquinolines 1 were resolved smoothly with selectivity factors of up to 569 to afford the corresponding chiral borylated tetrahydroquinolines 2 as the single diastereomer with up to 99% ee and the recovered 2-substituted 1,2-dihydroquinolines 1 in high yields with excellent enantioselectivities (98–99.9% ee). It is notable that various carbamate moieties of 1,2-dihydroquinolines have no obvious effect on the kinetic resolution, affording the borylation products 2a–2e with 91–97% ee and the recovered products 1a–1e with 98–99.9% ee, corresponding to selectivity factors (s) of 111 to 251. The racemic 1,2-dihydroquinolines bearing a Me or MeO group at the 6- or 7-position were also tolerated, furnishing the chiral products 2f–2h in high yields, with excellent enantioselectivities (95–96% ee) and selectivity factors (s = 229–251). In addition, replacing 1-naphthyl with 2-naphthyl led to a similar result, producing the borylation product 2i with 94% ee and recovered product 1i with 98% ee, with a selectivity factor (s) of 211. Gratifyingly, substituted phenyl groups at the 2-position of 1,2-dihydroquinoline proved to have no effect on kinetic resolution. Thus, excellent ee values for both borylation products and recovered materials were achieved with high selectivity factors (s = 99–569) irrespective of the electronic properties or position of the substituents in the 2-phenyl group, affording 2j–2p with 90–99% ee and recovered product 1j–1p with over 99% ee. Remarkably, the o-tolyl substituted substrate rac-1k provided the product 2k with both the highest enantioselectivity (99% ee) and a selectivity factor of 569. It is noteworthy that the 2-alkyl substituted substrates 1q and 1r could also be resolved with high selectivity factors (99 and 145, respectively), giving the corresponding borylation products 2q and 2r with comparable enantioselectivities (90% ee and 93% ee), and recovered products 1q and 1r with an identical ee of 99%.

Table 2. Substrate scope a , b .

|

|

aUnless otherwise mentioned, all reactions were performed with CuCl (0.025 mmol), (R,S p)-JosiPhos-1 (0.025 mmol), rac-1 (0.5 mmol), B2Pin2 (0.6 mmol), MeOK (0.1 mmol), THF (1.5 mL), MeOH (1.0 mmol), 0 °C, 30 min.

bIsolated yield; calculated conversion, C = ee1/(ee1 + ee2); enantiomeric excess (ee) was determined by chiral HPLC or SFC analysis using a chiral stationary phase; diastereomeric ratio (dr) > 99 : 1 (determined by 1H NMR). Selectivity factor (s) = ln[(1 – C) (1 – ee1)]/ln[(1 – C) (1 + ee1)].

cTHF/toluene/DME = 2 : 1 : 1 (1.5 mL), 2 h.

d tBuOK (0.1 mmol), THF/toluene/DME = 1 : 1 : 1 (1.5 mL), 2 h.

eTHF/toluene/DME = 1 : 1 : 1 (1.5 mL), 2 h.

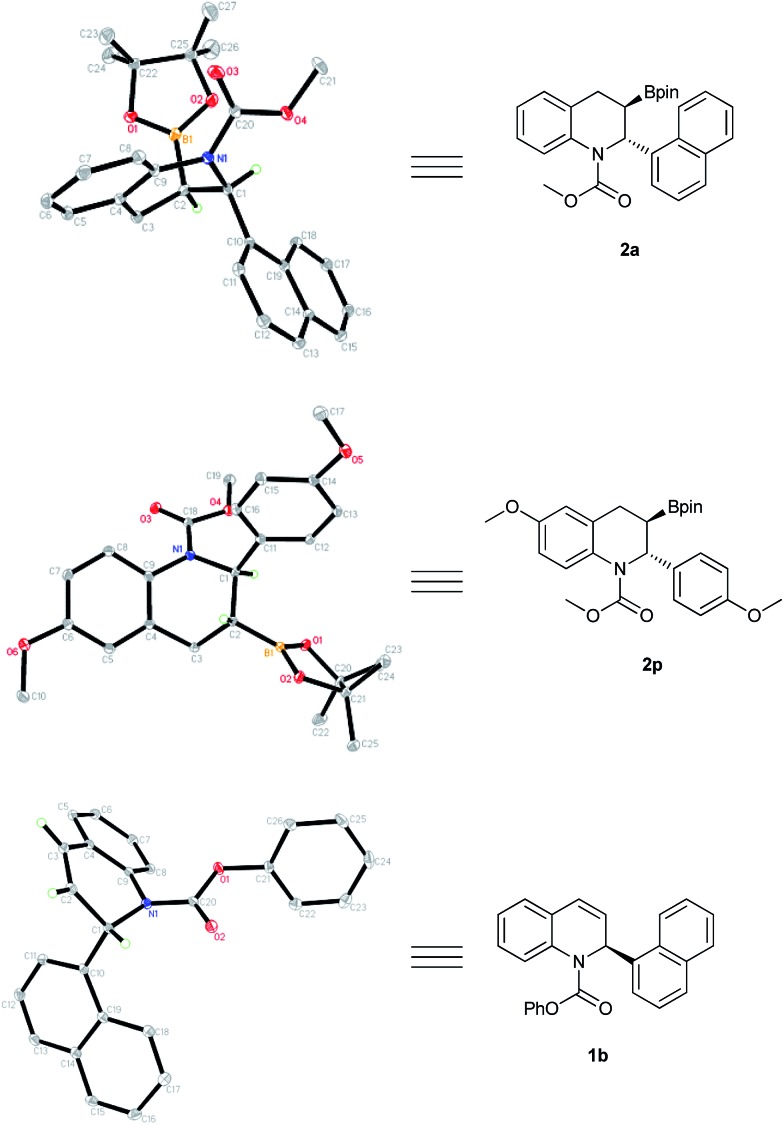

The generated borylation products 2a and 2p were the trans isomers, with an absolute configuration of (2R,3R), determined by X-ray crystallography. Likewise, recovered product 1b was assigned the (S) configuration according to the corresponding single-crystal structure (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. X-ray crystallographic analysis of products 2a, 2p and recovered 1b.

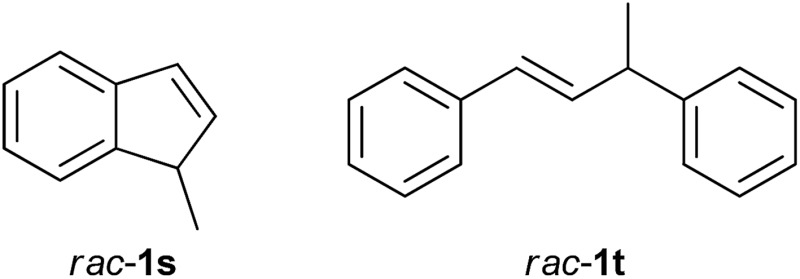

However, this strategy was not effective for the kinetic resolution of simple olefins. Thus, under the optimized reaction conditions, the borylation of substrates 1s and 1t did not proceed at all. The rac-1s and 1t were completely recovered.

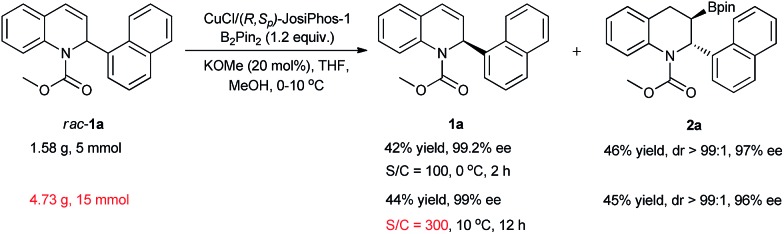

To demonstrate the potential of the kinetic resolution, turnover number (TON) experiments were conducted on a gram-scale. With a lower catalyst loading of 1.0 mol% (TON = 100), the kinetic resolution of rac-1a was completed, providing the desired product 2a in 46% yield with 97% ee and the recovered product 1a in 42% yield with 99.2% ee. With a much lower catalyst loading of 0.33 mol% (TON = 300), rac-1a (15 mmol, 4.73 g) was smoothly resolved at 10 °C to produce the corresponding product 2a in 45% yield with 96% ee and the recovered product 1a in 44% yield with 99% ee (Scheme 2), which represents the highest activity achieved in Cu-catalyzed borylation reactions to date.

Scheme 2. Kinetic resolution of rac-1a on a gram scale with a lower catalyst loading.

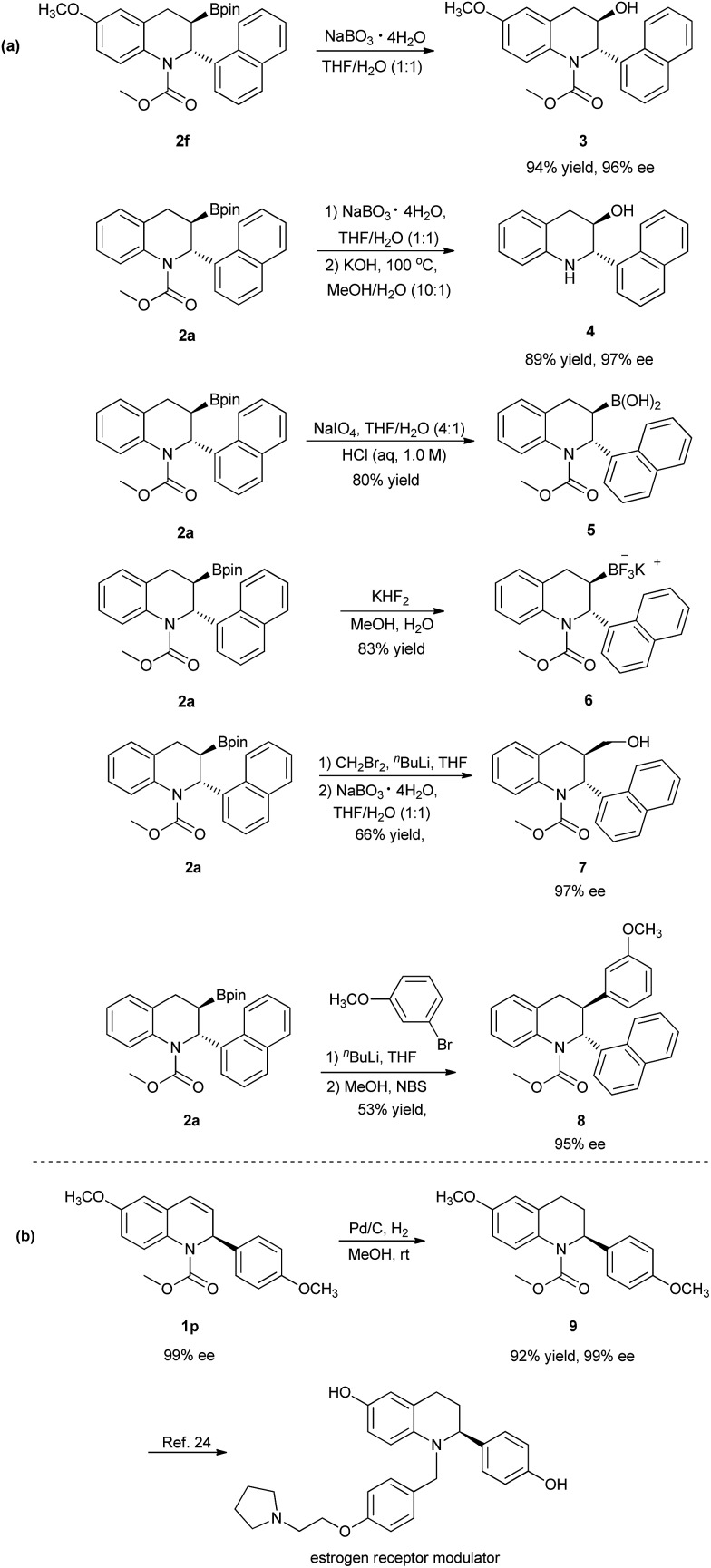

The chiral 3-boryl-tetrahydroquinolines 2 are versatile synthetic intermediates that can be easily converted to various derivatives (Scheme 3(a)).18e,24 For example, product 2f could be converted to the chiral 3-hydroxyl tetrahydroquinoline 3 bearing two vicinal stereogenic centers by oxidation with NaBO3, in high yields and without any loss of enantioselectivity. The oxidation of 2a, followed by the hydrolysis of the carbamate afforded the chiral 3-hydroxyl tetrahydroquinoline 4 with maintained enantioselectivity, 97% ee. Compound 2a could also be successfully transformed into both the corresponding boronic acid 5 and the trifluoroborate salt 6 in good yields. Moreover, 2a could also be converted to the primary alcohol 7 and compound 8 with high enantioselectivities by homologation and Suzuki–Miyaura coupling, respectively.12b,25 In addition, a simple Pd/C-catalyzed hydrogenation of the chiral recovered compound 1p with 99% ee afforded the tetrahydroquinoline 9 with retention of configuration, which was subsequently applied to the enantioselective synthesis of selective estrogen receptor modulators (Scheme 3(b)).26

Scheme 3. Representative transformations of products 2 and enantiomerically enriched recovered starting material 1.

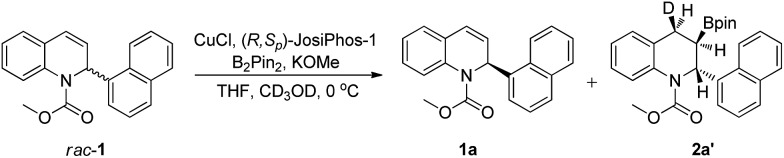

In order to elucidate the reaction mechanism, a labeling experiment with deuterium was performed (see the ESI†). The borylation of rac-1a under the optimized conditions using CD3OD instead of CH3OH gave the product 2a labelled with deuterium at the 4-position (>95% D), with excellent enantioselectivity, 97% ee (Scheme 4). The syn configuration between the deuterium atom at the 4-position and the boryl group at the 3-position indicated that the addition of the Cu–B complex to the C–C double bond of rac-1a occurred in a syn fashion.

Scheme 4. Deuterium labeling experiment.

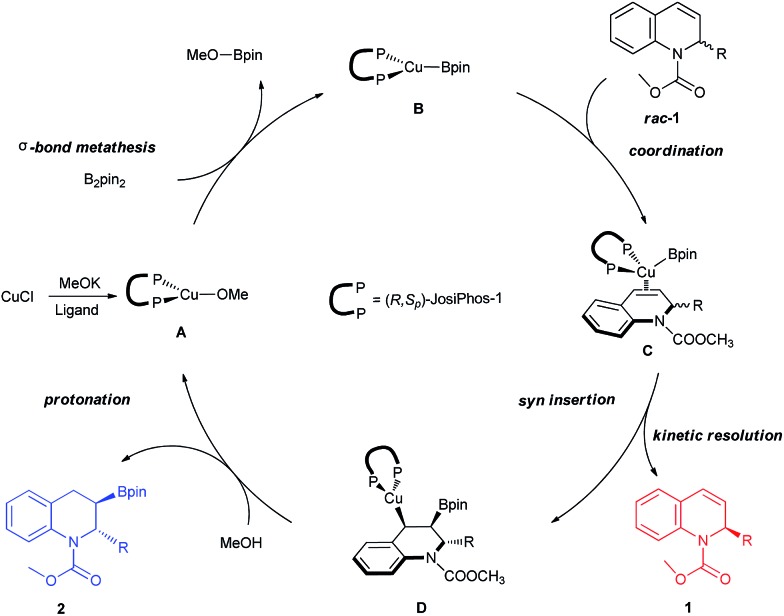

Based on previous reports and our experiment,18c,27 a feasible mechanism for the kinetic resolution of 2-substituted 1,2-dihydroquinolines via Cu-catalyzed borylation was proposed, as shown in Fig. 5. The initial exchange of CuCl with the ligand and MeOK resulted in the formation of the Cu–OMe complex A, followed by a σ-bond metathesis with B2pin2 to generate the borylcopper species B. Subsequently, the coordination of the racemic 2-substituted 1,2-dihydroquinoline 1 to copper gave complex C. The syn-addition furnished the borylated alkylcopper intermediate D along with the chiral recovered starting material 1. Finally, the protonation of D by MeOH formed the corresponding borylation product 2 and regenerated the Cu–OMe complex A.

Fig. 5. Proposed catalytic cycle for the kinetic resolution via Cu-catalyzed borylation.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we have presented the first kinetic resolution of 2-substituted 1,2-dihydroquinolines by asymmetric Cu-catalyzed borylation under mild reaction conditions, achieving excellent enantiodiscrimination and kinetic resolution. A wide range of chiral 3-boryl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinolines containing two vicinal stereogenic centers and recovered 2-substituted 1,2-dihydroquinolines were obtained after 30 minutes in high yields with 90–99% ee (dr > 99 : 1) and over 98% ee, respectively, corresponding to kinetic selectivity factors of up to 569. Finally, this protocol was successfully applied to the asymmetric synthesis of selective estrogen receptor modulators.

Acknowledgments

We thank for their generous financial support the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 21672024, 21272026, and 21472013), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, the Program for Changjiang Scholars and the Innovative Research Team in University, and the Beijing Municipal Commission of Education. Guohua Hou dedicates this work to Professor Qi-Lin Zhou on the occasion of his 60th birthday.

Footnotes

References

- Sridharan V., Suryavanshi P. A., Menéndez J. C. Chem. Rev. 2011;111:7157. doi: 10.1021/cr100307m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Kim W.-G., Kim J.-P., Kim C.-J., Lee K.-H., Yoo I.-D. J. Antibiot. 1996;49:20. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.49.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hiessböck R., Wolf C., Richter E., Hitzler M., Chiba P., Kratzel M., Ecker G. J. Med. Chem. 1999;42:1921. doi: 10.1021/jm980517+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Gore V. K., Ma V. V., Yin R., Ligutti J., Immke D., Doherty E. M., Norman M. H. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010;20:3573. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.04.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Sikorski J. A. J. Med. Chem. 2006;49:1. doi: 10.1021/jm058224l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mengozzi L., Gualandi A., Cozzi P. G. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2016;2016:3200. [Google Scholar]

- (a) Ma D., Xia C., Jiang J., Zhang J. Org. Lett. 2001;3:2189. doi: 10.1021/ol016043h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Hara O., Koshizawa T., Makino K., Kunimune I., Namiki A., Hamada Y. Tetrahedron. 2007;63:6170. [Google Scholar]; (c) Patil N. T., Wu H., Yamamoto Y. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:6577. doi: 10.1021/jo0708137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Wu J., Chan A. S. C. Acc. Chem. Res. 2006;39:711. doi: 10.1021/ar0680015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Zhou Y.-G. Acc. Chem. Res. 2007;40:1357. doi: 10.1021/ar700094b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Wang D.-S., Chen Q.-A., Lu S.-M., Zhou Y.-G. Chem. Rev. 2012;112:2557. doi: 10.1021/cr200328h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Lu S.-M., Wang Y.-Q., Han X.-W., Zhou Y.-G. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006;45:2260. doi: 10.1002/anie.200503073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wang D.-W., Wang X.-B., Wang D.-S., Lu S.-M., Zhou Y.-G., Li Y.-X. J. Org. Chem. 2009;74:2780. doi: 10.1021/jo900073z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Wang T., Zhuo L.-G., Li Z., Chen F., Ding Z., He Y., Fan Q.-H., Xiang J., Yu Z.-X., Chan A. S. C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:9878. doi: 10.1021/ja2023042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Chen Z.-P., Ye Z.-S., Chen M.-W., Zhou Y.-G. Synthesis. 2013;45:3239. [Google Scholar]; (e) Zhou J., Zhang Q.-F., Zhao W.-H., Jiang G.-F. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2016;14:6937. doi: 10.1039/c6ob01176d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Zhou H., Li Z., Wang Z., Wang T., Xu L., He Y., Fan Q.-H., Pan J., Gu L., Chan A. S. C. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:8464. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Guo Q.-S., Du D.-M., Xu J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:759. doi: 10.1002/anie.200703925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wang C., Li C., Wu X., Pettman A., Xiao J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009;48:6524. doi: 10.1002/anie.200902570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Rueping M., Antonchick A. P., Theissmann T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006;45:3683. doi: 10.1002/anie.200600191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Zhang Z., Du H. Org. Lett. 2015;17:6266. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b03307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Zhang Z., Du H. Org. Lett. 2015;17:2816. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b01240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Pappoppula M., Cardoso F. S. P., Garrett B. O., Aponick A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015;54:15202. doi: 10.1002/anie.201507848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Black D. A., Beveridge R. E., Arndtsen B. A. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:1906. doi: 10.1021/jo702293h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Sylvester K. T., Wu K., Doyle A. G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:16967. doi: 10.1021/ja3079362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Shields J. D., Ahneman D. T., Graham T. J. A., Doyle A. G. Org. Lett. 2014;16:142. doi: 10.1021/ol4031364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Liu Y., Zhang D., Wei H., Shi M., Wang F. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016;55:3776. doi: 10.1002/anie.201511663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Semba K., Fujihara T., Terao J., Tsuji Y. Tetrahedron. 2015;71:2183. [Google Scholar]; (b) Joannou M. V., Moyer B. S., Meek S. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:6176. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b03477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Xi Y., Hartwig J. F. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:6703. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b02478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Lee H., Han J. T., Yun J. ACS Catal. 2016;6:6487. [Google Scholar]

- For reviews on catalytic enantioselective hydroboration, see: ; (a) Crudden C. M., Edwards D. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2003;2003:4695. [Google Scholar]; (b) Carroll A.-M., O'Sullivan T. P., Guiry P. J. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2005;347:609. [Google Scholar]; (c) Noh D., Chea H., Ju J., Yun J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009;48:6062. doi: 10.1002/anie.200902015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Smith S. M., Takacs J. M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:1740. doi: 10.1021/ja908257x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Lee Y., Hoveyda A. H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:3160. doi: 10.1021/ja809382c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Feng X., Jeon H., Yun J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013;52:3989. doi: 10.1002/anie.201208610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Lee H., Lee B. Y., Yun J. Org. Lett. 2015;17:764. doi: 10.1021/ol503598w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Sasaki Y., Zhong C., Sawamura M., Ito H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:1226. doi: 10.1021/ja909640b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Corberan R., Mszar N. W., Hoveyda A. H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011;50:7079. doi: 10.1002/anie.201102398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For selected examples on catalytic enantioselective diboration, see: ; (a) Burks H. E., Morken J. P. Chem. Commun. 2007;2007:4717. doi: 10.1039/b707779c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Mlynarski S. N., Schuster C. H., Morken J. P. Nature. 2014;505:386. doi: 10.1038/nature12781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Lee Y., Jang H., Hoveyda A. H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:18234. doi: 10.1021/ja9089928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Burks H. E., Kliman L. T., Morken J. P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:9134. doi: 10.1021/ja809610h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Coombs J. R., Haeffner F., Kliman L. T., Morken J. P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:11222. doi: 10.1021/ja4041016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Toribatake K., Nishiyama H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013;52:11011. doi: 10.1002/anie.201305181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Coombs J. R., Zhang L., Morken J. P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:16140. doi: 10.1021/ja510081r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Kliman L. T., Mlynarski S. N., Morken J. P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:13210. doi: 10.1021/ja9047762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For selected examples on catalytic enantioselective arylborylation, see: ; (a) Nelson H. M., Williams B. D., Miró J., Toste F. D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:3213. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b00344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Su W., Gong T. J., Lu X., Xu M. Y., Yu C. G., Xu Z. Y., Yu H. Z., Xiao B., Fu Y. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015;54:12957. doi: 10.1002/anie.201506713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For selected examples of metal-catalyzed enantioselective conjugate boron additions, see: ; (a) Lee J.-E., Yun J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008;47:145. doi: 10.1002/anie.200703699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Chen I. H., Yin L., Itano W., Kanai M., Shibasaki M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:11664. doi: 10.1021/ja9045839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Chen I.-H., Kanai M., Shibasaki M. Org. Lett. 2010;12:4098. doi: 10.1021/ol101691p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Lee J. C. H., Hall R., McDonald D. G. Nat. Chem. 2011;3:894. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Lou Y., Cao P., Jia T., Zhang Y., Wang M., Liao J. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015;54:12134. doi: 10.1002/anie.201505926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) O'Brien J. M., Lee K.-S., Hoveyda A. H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:10630. doi: 10.1021/ja104777u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Wu H., Radomkit S., O'Brien J. M., Hoveyda A. H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:8277. doi: 10.1021/ja302929d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Radomkit S., Hoveyda A. H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014;53:3387. doi: 10.1002/anie.201309982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For selected examples on catalytic allylic boration, see: ; (a) Ito H., Ito S., Sasaki Y., Matsuura K., Sawamura M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:14856. doi: 10.1021/ja076634o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Guzman-Martinez A., Hoveyda A. H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:10634. doi: 10.1021/ja104254d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Ito H., Kunii S., Sawamura M. Nat. Chem. 2010;2:972. doi: 10.1038/nchem.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Park J. K., Lackey H. H., Ondrusek B. A., McQuade D. T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:2410. doi: 10.1021/ja1112518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Semba K., Fujihara T., Terao J., Tsuji Y. Tetrahedron. 2015;71:2183. [Google Scholar]

- For selected examples on boration of heterocyclic compounds, see: ; (a) Kubota K., Hayama K., Iwamoto H., Ito H. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015;54:8809. doi: 10.1002/anie.201502964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kubota K., Watanabe Y., Hayama K., Ito H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:4338. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b01375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Kubota K., Watanabe Y., Ito H. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2016;358:2379. [Google Scholar]; (d) Nishikawa D., Hirano K., Miura M. Org. Lett. 2016;18:4856. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b02338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Guisan-Ceinos M., Parra A., Martin-Heras V., Tortosa M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016;55:6969. doi: 10.1002/anie.201601976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) The selectivity factor (s) = (rate of fast-reacting enantiomer)/(rate of slow-reacting enantiomer) = ln[(1 – C)(1 – ee)]/ln[(1 – C)(1 + ee)] where C is the conversion and ee is the enantiomeric excess of the remaining starting material. C = ee/(ee + ee′), which ee is the enantiomeric excess of the remaining starting material and ee′ is the enantiomeric excess of the corresponding product. Kagan H. B., Fiaud J. C., Top. Stereochem., 1988, 18 , 249 . [Google Scholar]; (b) Vedejs E., Jure M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005;44:3974. doi: 10.1002/anie.200460842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Robinson D. E. J. E., Bull S. D. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2003;14:1407. [Google Scholar]; (d) Xie J.-H., Zhou Q.-L. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008;41:581. doi: 10.1021/ar700137z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For selected examples of kinetic resolution, see: ; (a) Hu H., Liu Y., Liu L., Zhang Y., Liu X., Feng X. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016;55:10098. doi: 10.1002/anie.201605251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Shinozawa T., Terasaki S., Mizuno S., Kawatsura M. J. Org. Chem. 2016;81:5766. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.6b00939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Huang T., Lin L., Hu X., Zheng J., Liu X., Feng X. Chem. Commun. 2015;51:11374. doi: 10.1039/c5cc02179k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Grassi D., Alexakis A. Chem. Sci. 2014;5:3803. [Google Scholar]

- For selected examples of kinetic resolution by cross-coupling, see: ; (a) Lei B.-L., Ding C.-H., Yang X.-F., Wan X.-L., Hou X.-L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:18250. doi: 10.1021/ja9082717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Xiao K.-J., Chu L., Chen G., Yu J.-Q. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:7796. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b04660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Choi Y. K., Suh J. H., Lee D., Lim I. T., Jung J. Y., Kim M.-J. J. Org. Chem. 1999;64:8423. doi: 10.1021/jo990956w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Lüssem B. J., Gais H.-J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:6066. doi: 10.1021/ja034109t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Fischer C., Defieber C., Suzuki T., Carreira E. M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:1628. doi: 10.1021/ja0390707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Hou X. L., Zheng B. H. Org. Lett. 2009;11:1789. doi: 10.1021/ol9002543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Chu L., Xiao K.-J., Yu J.-Q. Science. 2014;346:451. doi: 10.1126/science.1258538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Gao D.-W., Gu Q., You S.-L. ACS Catal. 2014;4:2741. [Google Scholar]; (i) Xiao K.-J., Chu L., Yu J.-Q. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016;55:2856. doi: 10.1002/anie.201510808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Bhat V., Wang S., Stoltz B. M., Virgil S. C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:16829. doi: 10.1021/ja409383f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For selected examples of kinetic resolution by organocatalysts, see: ; (a) Kuroda Y., Harada S., Oonishi A., Kiyama H., Yamaoka Y., Yamada K.-i., Takasu K. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016;55:13137. doi: 10.1002/anie.201607208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Saito K., Akiyama T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016;55:3148. doi: 10.1002/anie.201510692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) An D., Guan X., Guan R., Jin L., Zhang G., Zhang S. Chem. Commun. 2016;52:11211. doi: 10.1039/c6cc06388h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Dong S., Frings M., Cheng H., Wen J., Zhang D., Raabe G., Bolm C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:2166. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b00143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Wang J., Chen M.-W., Ji Y., Hu S.-B., Zhou Y.-G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:10413. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b06009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Wanner B., Kreituss I., Gutierrez O., Kozlowski M. C., Bode J. W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:11491. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b07201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Lin X., Ruan S., Yao Q., Yin C., Lin L., Feng X., Liu X. Org. Lett. 2016;18:3602. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b01614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Sorrentino E., Connon S. J. Org. Lett. 2016;18:5204. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b02398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (i) Shirakawa S., Wu X., Maruoka K. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013;52:14200. doi: 10.1002/anie.201308237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (j) Cheng D.-J., Yan L., Tian S.-K., Wu M.-Y., Wang L.-X., Fan Z.-L., Zheng S.-C., Liu X.-Y., Tan B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014;53:3684. doi: 10.1002/anie.201310562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amiot F., Cointeaux L., Silve E. J., Alexakis A. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:8221. [Google Scholar]

- Liskey C. W., Hartwig J. F. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:3375. doi: 10.1021/ja400103p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonet A., Odachowski M., Leonori D., Essafi S., Aggarwal V. K. Nat. Chem. 2014;6:584. doi: 10.1038/nchem.1971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Wallace O. B., Lauwers K. S., Jones S. A., Dodge J. A. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2003;13:1907. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(03)00306-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Tadaoka H., Cartigny D., Nagano T., Gosavi T., Ayad T., Genêt J.-P., Ohshima T., Ratovelomanana-Vidal V., Mashima K. Chem.–Eur. J. 2009;15:9990. doi: 10.1002/chem.200901477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (a) Matsuda N., Hirano K., Satoh T., Miura M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:4934. doi: 10.1021/ja4007645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Laitar D. S., Müller P., Sadighi J. P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:17196. doi: 10.1021/ja0566679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.