Abstract

Patients with connective tissue disease-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH-CTD) have a poor prognosis compared with other aetiologies. The underlying CTD can influence treatment response and outcomes. We characterised the GRIPHON study PAH-CTD subgroup and evaluated response to selexipag.

Of 334 patients with PAH-CTD, PAH was associated with systemic sclerosis (PAH-SSc) in 170, systemic lupus erythematosus (PAH-SLE) in 82 and mixed CTD/CTD-other in 82. For the primary composite endpoint of morbidity/mortality, hazard ratios (HR) and 95% CI were calculated using Cox proportional hazard models.

Compared with the overall GRIPHON population, the CTD subgroup was slightly older with a greater proportion of females and shorter time since diagnosis. Patients with PAH-SSc appeared to be more impaired at baseline, with a more progressive disease course. The converse was observed for PAH-SLE. Selexipag reduced the risk of composite morbidity/mortality events in patients with PAH-CTD by 41% (HR 0.59; 95% CI 0.41–0.85). Treatment effect was consistent irrespective of baseline PAH therapy or CTD subtype (interaction p=0.87 and 0.89, respectively). Adverse events were predominately prostacyclin-related and known for selexipag treatment.

GRIPHON has allowed the comprehensive characterisation of patients with PAH-CTD. Selexipag delayed progression of PAH and was well-tolerated among PAH-CTD patients, including those with PAH-SSc and PAH-SLE.

Short abstract

Selexipag delays disease progression and is well tolerated in PAH-CTD, irrespective of subtype or other PAH therapy http://ow.ly/SvIV30cqo9J

Introduction

Connective tissue disease (CTD) encompasses a heterogeneous group of diseases including systemic sclerosis (SSc) and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) [1–3]. Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a serious complication of CTD [2, 4] and, historically, patients with PAH associated with CTD (PAH-CTD) have had worse outcomes compared with those with idiopathic PAH (IPAH) [5]. Depending on the underlying CTD, patients may have different prognoses and response to PAH therapy [6, 7]. Recent data suggest that PAH-CTD patients may respond well to treatment regimens that combine PAH therapies; however, these reports are few [8, 9]. Dedicated evaluation of PAH therapies in CTD subtypes is even more limited and such reports tend to be observational or based on small patient numbers.

The long-term, phase III GRIPHON trial evaluated the selective IP prostacyclin receptor agonist selexipag in 1156 PAH patients, the majority of whom had IPAH (649 patients) or PAH-CTD (334 patients). In the overall study population, selexipag reduced the risk of the primary composite outcome of morbidity/mortality by 40% (p<0.001) compared with placebo. At baseline, 80% of patients were receiving PAH therapy, including 32.5% who were receiving both an endothelin receptor antagonist (ERA) and a phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor (PDE-5i). In the PAH-CTD subgroup, selexipag reduced the risk of a primary endpoint event by 41% compared with placebo [10].

The objectives of the current analyses were to describe in detail the PAH-CTD patients enrolled in GRIPHON, including those with PAH-SSc and PAH-SLE, and to characterise their response to selexipag in terms of dosing, efficacy and tolerability.

Methods

Study population

GRIPHON was a global, double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, event-driven phase III trial (www.clinicaltrials.gov identifier number NCT01106014) and has been described in detail previously [10]. Eligible patients were 18–75 years of age with a PAH diagnosis confirmed by right heart catheterisation. PAH aetiology was specified by the investigator as idiopathic, heritable, associated with CTD, assocatied with repaired congenital shunts, associated with HIV, or associated with drug/toxin exposure. For patients with PAH-CTD, the underlying CTD could be specified as SSc, SLE or mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD). At baseline, patients were required to have a 6-min walk distance of 50–450 m. Patients naïve to treatment, and those receiving a PDE-5i, an ERA, or both, at doses that were stable for at least 3 months prior to randomisation, were eligible. Patients receiving prostacyclin or its analogues were not eligible.

Study design

After a 28-day screening period, patients were randomised 1:1 to receive selexipag or placebo. During the 12-week titration period, the study drug was initiated at 200 µg twice daily and titrated weekly in increments of 200 µg twice daily to the highest tolerated dose. The maximum dose allowed was 1600 µg twice daily. From Week 26, dose increases were allowed at scheduled visits; dose reductions were allowed at any time. The individualised maintenance dose (IMD) of selexipag was defined as the dose the patient received for the longest duration in the study. Three dose groups: low (200 and 400 µg twice daily), medium (600, 800 and 1000 µg twice daily) and high (1200, 1400 and 1600 µg twice daily), were pre-specified and patients were included within these groups based on their IMD. Patients received double-blind treatment until they experienced a primary endpoint event, prematurely discontinued the study drug, or the study ended. The end of the study was declared when the pre-specified number of 331 primary endpoint events was reached. The trial adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and the protocol was approved by local institutional review boards or independent ethics committees. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Outcome measures

The primary composite endpoint was the time from randomisation to first morbidity/mortality event (i.e. disease progression or worsening of PAH that resulted in hospitalisation, initiation of parenteral prostanoid therapy or long-term oxygen therapy, the need for lung transplantation or balloon atrial septostomy, or death from any cause), up to the end of double-blind treatment. Disease progression was defined as a ≥15% decrease in 6-min walk distance from baseline, confirmed by a second test on a different day, and worsening in World Health Organization (WHO) functional class (for patients in functional class II/III at baseline) or need for additional PAH therapy (for patients in functional class III/IV at baseline). A blinded independent committee adjudicated all primary endpoint events. Secondary endpoints included change in 6-min walk distance from baseline to Week 26 and all-cause death up to the end of the study. Exploratory endpoints included change in N-terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) level from baseline to Week 26. Adverse events and serious adverse events were collected up to 7 days and 30 days after the end of the study, respectively.

Statistical analyses

We performed post hoc analyses on the PAH-CTD subgroup. For all time-to-event endpoints, Kaplan–Meier estimates by treatment arm were calculated. Hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated using Cox proportional-hazard models. Subgroup analyses were performed using interaction tests. The changes from baseline in 6-min walk distance and NT-proBNP were analysed using a non-parametric analysis of covariance, adjusted for the respective baseline value. Missing 6-min walk distance values were imputed as described previously [10]. Analysis of NT-proBNP levels was performed on observed data.

Results

Patients and treatment exposure

Of the 1156 patients enrolled in GRIPHON, 334 were diagnosed with PAH-CTD. This comprised 170 with PAH-SSc, 82 with PAH-SLE, 37 with PAH-MCTD and 45 in whom the underlying CTD was not further defined (PAH-CTD-other). Due to smaller patient numbers, and corresponding number of primary endpoint events, we present the patients in the PAH-MCTD and PAH-CTD-other groups as a single group (PAH-MCTD/CTD-other).

Of the 334 patients with PAH-CTD, 167 received placebo and 167 received selexipag. The median treatment durations for placebo and selexipag were 62.0 and 67.1 weeks, respectively, similar to the treatment duration in the overall study population [10]. Baseline characteristics of the PAH-CTD subgroup and the three CTD subtypes are presented in table 1. In the PAH-CTD subgroup, the majority of the patients were female: 87.4% (placebo) and 92.8% (selexipag). The mean±sd age was 52.8±15.0 years for placebo and 51.8±14.1 years for selexipag. Patients with PAH-SSc were older than those with PAH-SLE. There were also regional differences: PAH-SSc was most frequent in Western countries, whereas PAH-SLE was most common in Asia. In the PAH-CTD subgroup, the proportion of patients receiving PAH therapy at baseline (74.9% and 78.4% for placebo and selexipag, respectively) was similar to that of the overall study population [10]. Compared with the other CTD subtypes, a slightly higher proportion of PAH-SLE patients were not receiving any PAH therapy at baseline and a greater proportion of PAH-SSc patients were receiving both an ERA and PDE-5i.

TABLE 1.

Patient characteristics at baseline

| Characteristic | PAH-CTD | PAH-SSc | PAH-SLE | PAH-MCTD/CTD-other | ||||

| Placebo | Selexipag | Placebo | Selexipag | Placebo | Selexipag | Placebo | Selexipag | |

| Patients n | 167 | 167 | 93 | 77 | 37 | 45 | 37 | 45 |

| Females | 146 (87.4) | 155 (92.8) | 76 (81.7) | 67 (87.0) | 36 (97.3) | 45 (100.0) | 34 (91.9) | 43 (95.6) |

| Age years | 52.8±15.0 | 51.8±14.1 | 61.2±9.9 | 58.6±11.2 | 38.6±11.3 | 39.3±11.4 | 46.1±15.0 | 52.5±12.6 |

| Geographic region | ||||||||

| Asia | 39 (23.4) | 48 (28.7) | 3 (3.2) | 7 (9.1) | 22 (59.5) | 26 (57.8) | 14 (37.8) | 15 (33.3) |

| Eastern Europe | 30 (18.0) | 28 (16.8) | 25 (26.9) | 16 (20.8) | 2 (5.4) | 4 (8.9) | 3 (8.1) | 8 (17.8) |

| Latin America | 12 (7.2) | 13 (7.8) | 6 (6.5) | 3 (3.9) | 3 (8.1) | 3 (6.7) | 3 (8.1) | 7 (15.6) |

| North America | 28 (16.8) | 33 (19.8) | 14 (15.1) | 21 (27.3) | 6 (16.2) | 6 (13.3) | 8 (21.6) | 6 (13.3) |

| Western Europe/Australia | 58 (34.7) | 45 (26.9) | 45 (48.4) | 30 (39.0) | 4 (10.8) | 6 (13.3) | 9 (24.3) | 9 (20.0) |

| Time since diagnosis of PAH years# | 1.7±2.3 | 1.6±2.3 | 1.6±2.1 | 1.5±2.2 | 1.7±2.2 | 1.4±1.9 | 2.1±2.8 | 2.0±2.8 |

| WHO functional class | ||||||||

| I | 3 (1.8) | 2 (2.6) | 1 (2.2) | |||||

| II | 74 (44.3) | 80 (47.9) | 35 (37.6) | 22 (28.6) | 24 (64.9) | 30 (66.7) | 15 (40.5) | 28 (62.2) |

| III | 92 (55.1) | 84 (50.3) | 57 (61.3) | 53 (68.8) | 13 (35.1) | 14 (31.1) | 22 (59.5) | 17 (37.8) |

| IV | 1 (0.6) | 1 (1.1) | ||||||

| 6-min walk distance m | 334.0±84.9 | 354.5±72.7 | 319.7±84.0 | 339.1±81.9 | 365.2±79.7 | 378.6±53.3 | 339.1±85.5 | 356.6±67.1 |

| Use of medication for PAH | ||||||||

| None | 42 (25.1) | 36 (21.6) | 25 (26.9) | 13 (16.9) | 10 (27.0) | 15 (33.3) | 7 (18.9) | 8 (17.8) |

| ERA | 26 (15.6) | 40 (24.0) | 12 (12.9) | 19 (24.7) | 8 (21.6) | 12 (26.7) | 6 (16.2) | 9 (20.0) |

| PDE-5i | 43 (25.7) | 51 (30.5) | 19 (20.4) | 20 (26.0) | 13 (35.1) | 9 (20.0) | 11 (29.7) | 22 (48.9) |

| ERA and PDE-5i | 56 (33.5) | 40 (24.0) | 37 (39.8) | 25 (32.5) | 6 (16.2) | 9 (20.0) | 13 (35.1) | 6 (13.3) |

| Other medications | ||||||||

| Immunosuppressants | 35 (21.0) | 28 (16.8) | 15 (16.1) | 10 (13.0) | 10 (27.0) | 9 (20.0) | 10 (27.0) | 9 (20.0) |

| Corticosteroids¶ | 81 (48.5) | 81 (48.5) | 30 (32.3) | 24 (31.2) | 26 (70.3) | 31 (68.9) | 25 (67.6) | 26 (57.8) |

| Calcium channel blockers | 45 (26.9) | 45 (26.9) | 30 (32.3) | 32 (41.6) | 7 (18.9) | 4 (8.9) | 8 (21.6) | 9 (20.0) |

| Cardiac therapy | 94 (56.3) | 95 (56.9) | 49 (52.7) | 39 (50.6) | 21 (56.8) | 26 (57.8) | 24 (64.9) | 30 (66.7) |

| Anti-hypertensives | 88 (52.7) | 89 (53.3) | 54 (58.1) | 51 (66.2) | 15 (40.5) | 22 (48.9) | 19 (51.4) | 16 (35.6) |

| Beta-blockers | 17 (10.2) | 12 (7.2) | 9 (9.7) | 7 (9.1) | 3 (8.1) | 1 (2.2) | 5 (13.5) | 4 (8.9) |

Data are presented as n (%) or mean±sd, unless otherwise stated. PAH-CTD: pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with connective tissue disease; PAH-SSc: PAH associated with systemic sclerosis; PAH-SLE: PAH associated with systemic lupus erythematosus; PAH-MCTD: PAH associated with mixed connective tissue disease; CTD: connective tissue disease; WHO: World Health Organization; ERA: endothelin receptor antagonist; PDE-5i: phosphodiesterase type-5 inhibitor. #: confirmed by right heart catheterisation; ¶: for systemic use.

Selexipag dose

In the PAH-CTD subgroup, 40 patients (24.0%) had their IMD in the low-dose group, 45 (26.9%) in the medium-dose group and 75 (44.9%) in the high-dose group (supplementary table S1). These proportions were similar to those observed in the overall GRIPHON population [10] and there were no notable differences between CTD subtypes and the overall PAH-CTD subgroup (supplementary table S1).

Response to selexipag treatment

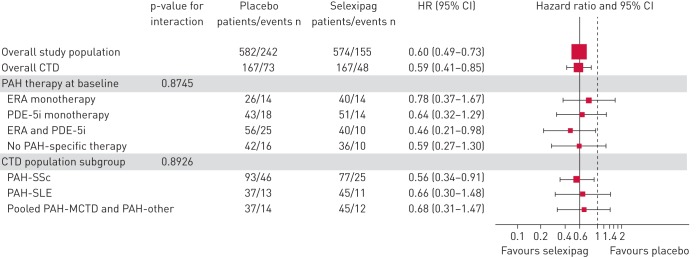

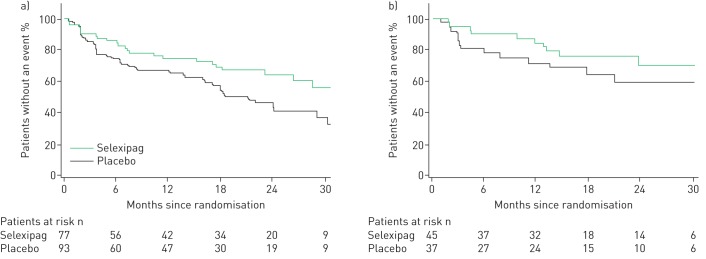

Among patients with PAH-CTD, selexipag reduced the risk of the primary composite endpoint of morbidity/mortality by 41% versus placebo (HR 0.59; 95% CI 0.41–0.85) [10] (figure 1; supplementary figure S1a). This response was consistent with that observed in the overall GRIPHON population, and with that in patients with IPAH/heritable PAH (HR 0.61; 95% CI 0.47–0.79; supplementary figure S1b). The treatment effect was consistent in patients with PAH-CTD irrespective of PAH therapy at baseline (interaction p=0.87; figure 1) and across the CTD subtypes (interaction p=0.89; figure 1). The risk reduction of selexipag versus placebo was 44% (HR 0.56; 95% CI 0.34–0.91) in patients with PAH-SSc and 34% (HR 0.66; 95% CI 0.30–1.48) in patients with PAH-SLE (figure 2). As observed in the overall GRIPHON population [10], disease progression and hospitalisation accounted for the majority of primary endpoint events among patients with PAH-CTD (80.2%), irrespective of the underlying CTD (supplementary table S2). By the end of the study, 34 of the PAH-CTD patients in the placebo group and 33 in the selexipag group had died, indicating no difference between the treatment groups (supplementary table S2; HR 0.98; 95% CI 0.61–1.59). Assessment of all-cause death at fixed time points and up to the end of the study yielded consistent results (supplementary table S3). The most frequently reported causes of death were PAH, disease progression and right heart failure (supplementary table S4).

FIGURE 1.

Effect of selexipag on the primary composite endpoint of morbidity/mortality by pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) therapy at baseline and connective tissue disease (CTD) subtype. ERA: endothelin receptor antagonist; PDE-5i: phosphodiesterase type-5 inhibitor; SSc: systemic sclerosis; SLE: systemic lupus erythematosus; MCTD: mixed CTD.

FIGURE 2.

Effect of selexipag on the primary composite endpoint of morbidity/mortality in patients with a) pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with systemic sclerosis and b) pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with systemic lupus erythematosus.

In the PAH-CTD subgroup, the 6-min walk distance decreased by a median of 10.0 m from baseline in the placebo group and 2.0 m from baseline in the selexipag group (treatment effect: 12 m [95% CI –4–27]; supplementary table S5). With respect to NT-proBNP, a median (Q1, Q3) decrease of −55.5 ng/L (−282.5, 48.0) from baseline to Week 26 was observed with selexipag compared with a median increase of 13 ng/L (−99.0, 404.0) with placebo (treatment effect: −140.0 [95% CI −265 to −51]; supplementary table S6). The results for the CTD subtypes for 6-min walk distance and NT-proBNP are presented in supplementary tables S5 and S6.

Overall in the PAH-CTD subgroup, 15 (9.1%) placebo-treated patients and 32 (19.2%) selexipag-treated patients discontinued their study regimen prematurely because of an adverse event (table 2). The frequencies of adverse events and serious adverse events reported in the treatment groups were similar for the PAH-CTD subgroup and for the CTD subtypes. The most frequent adverse events are listed in table 2 and supplementary table 7. The most frequent adverse events associated with therapies that target the prostacyclin pathway, which occurred during the titration and maintenance periods, are provided in table 3 and supplementary table S8. Irrespective of the underlying CTD, these adverse events were generally reported more frequently during the 12-week titration period (supplementary table S8), when they were used to define the highest tolerated dose.

TABLE 2.

Most frequent adverse events among patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) associated with connective tissue disease

| Placebo | Selexipag | |

| Subjects n | 165# | 167 |

| Adverse events n | 1301 | 1499 |

| Patients with at least one adverse event | 160 (97.0) | 164 (98.2) |

| Patients with at least one serious adverse event | 85 (51.5) | 80 (47.9) |

| Patients with adverse event leading to discontinuation of study drug | 15 (9.1) | 32 (19.2) |

| Adverse event¶ | ||

| Headache | 60 (36.4) | 104 (62.3) |

| Diarrhoea | 42 (25.5) | 67 (40.1) |

| Nausea | 41 (24.8) | 62 (37.1) |

| Worsening of PAH | 62 (37.6) | 39 (23.4) |

| Dizziness | 30 (18.2) | 35 (21.0) |

| Vomiting | 10 (6.1) | 34 (20.4) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 31 (18.8) | 33 (19.8) |

| Peripheral oedema | 31 (18.8) | 32 (19.2) |

| Pain in extremity | 8 (4.8) | 31 (18.6) |

| Dyspnoea | 37 (22.4) | 30 (18.0) |

| Pain in jaw | 11 (6.7) | 24 (14.4) |

| Myalgia | 10 (6.1) | 21 (12.6) |

| Arthralgia | 12 (7.3) | 19 (11.4) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 12 (7.3) | 19 (11.4) |

| Flushing | 8 (4.8) | 19 (11.4) |

| Cough | 23 (13.9) | 17 (10.2) |

| Chest pain | 15 (9.1) | 17 (10.2) |

| Decreased appetite | 9 (5.5) | 17 (10.2) |

| Anaemia | 17 (10.3) | 16 (9.6) |

Data are presented as n (%), unless otherwise stated. #: among the patients randomly assigned to the placebo group, two did not receive study treatment and were not included in the safety analysis set; ¶: adverse events are listed for those that occurred in more than 10% of the patients in any study group during the double-blind period and up to 7 days after placebo or selexipag was discontinued.

TABLE 3.

Prostacyclin (PGI2)-associated adverse events reported in the study titration and maintenance periods among patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with connective tissue disease

| Titration period | Maintenance period | |||

| Placebo | Selexipag | Placebo | Selexipag | |

| Subjects n | 165# | 167 | 142 | 142 |

| Patients with at least one PGI2-associated adverse event | 107 (64.8) | 143 (85.6) | 73 (51.4) | 103 (72.5) |

| Adverse event | ||||

| Headache | 56 (33.9) | 100 (59.9) | 26 (18.3) | 55 (38.7) |

| Diarrhoea | 29 (17.6) | 54 (32.3) | 23 (16.2) | 38 (26.8) |

| Nausea | 33 (20.0) | 53 (31.7) | 18 (12.7) | 31 (21.8) |

| Vomiting | 7 (4.2) | 28 (16.8) | 4 (2.8) | 15 (10.6) |

| Pain in extremity | 6 (3.6) | 27 (16.2) | 4 (2.8) | 18 (12.7) |

| Pain in jaw | 7 (4.2) | 22 (13.2) | 6 (4.2) | 19 (13.4) |

| Dizziness | 18 (10.9) | 20 (12.0) | 22 (15.5) | 21 (14.8) |

| Myalgia | 7 (4.2) | 20 (12.0) | 5 (3.5) | 10 (7.0) |

| Flushing | 7 (4.2) | 15 (9.0) | 3 (2.1) | 12 (8.5) |

| Arthralgia | 10 (6.1) | 11 (6.6) | 4 (2.8) | 15 (10.6) |

| Musculoskeletal pain | 3 (1.8) | 7 (4.2) | 5 (3.5) | 5 (3.5) |

Data are presented as n (%), unless otherwise stated. A patient with multiple occurrences of an adverse event during one treatment period is counted only once in the adverse event category for that treatment and period. #: among the patients randomly assigned to the placebo group, two did not receive study treatment and were not included in the safety analysis set.

Discussion

The GRIPHON trial included the largest number of PAH-CTD patients evaluated to date in a double-blind, randomised controlled trial. For patients with PAH-CTD, the treatment effect of selexipag on the primary composite endpoint of morbidity/mortality was consistent with the overall GRIPHON population [10]. The consistency in the treatment effect was apparent irrespective of baseline PAH treatment and irrespective of CTD subtype. Selexipag was generally well-tolerated in the PAH-CTD subgroup and in each CTD subtype. These results support a clinical benefit of selexipag treatment among different PAH-CTD patients and in the setting of combination therapy with an ERA, a PDE-5i, or both.

Some differences in demographics and baseline characteristics were noted between patients with PAH-CTD and the overall GRIPHON population [10], and between CTD subtypes. The baseline characteristics of the patients with PAH-SSc showed poorer 6-min walk distance and WHO functional class compared with the overall GRIPHON population [10]. Conversely, the characteristics of patients with PAH-SLE suggested less impairment. These findings are consistent with the previously reported natural history of PAH-SSc and PAH-SLE [6, 11–13], and are reflected in the descriptive analyses of the primary endpoint Kaplan–Meier curves, which illustrate this disease course. Compared with the overall PAH-CTD subgroup, patients with PAH-SSc had a more rapid disease progression, and patients with PAH-SLE a less rapid progression. This confirms, for the first time in a randomised controlled trial, previous observational data that indicate PAH-SSc patients have a worse prognosis than patients with other PAH-CTD subtypes [11, 14, 15].

Historically, compared with IPAH patients, those with PAH-CTD have been considered to display a more muted response to PAH therapies [5, 16–20]. With growing evidence from outcome-driven studies, and the adoption of combination therapy regimens in PAH, this view is changing. In the SERAPHIN trial, among the 155 PAH-CTD patients randomised to placebo or macitentan 10 mg, macitentan reduced the risk of the primary composite endpoint of morbidity/mortality by 42% compared with placebo [8]. The AMBITION trial enrolled newly diagnosed, treatment-naïve patients, including 187 with PAH-CTD. In this subgroup, combination therapy with ambrisentan and tadalafil reduced the risk of clinical failure events by 57% compared with monotherapy [9]. In GRIPHON, the large number of PAH-SSc and PAH-SLE patients has, for the first time, allowed meaningful exploration of patients according to CTD subtype. Despite the innate differences between these subtypes, the observed treatment effect with selexipag on the composite endpoint of morbidity/mortality was consistent among patients with PAH-SSc and PAH-SLE, and was driven by a reduction in disease progression and hospitalisation. Although patient numbers did not allow for formal analysis of the primary endpoint by baseline PAH therapy for each CTD subtype, most of the patients with PAH-SSc were already receiving an ERA, a PDE-5i, or both at baseline. These data suggest that selexipag can offer an incremental benefit to existing PAH treatment in patients with PAH-SSc.

In patients with PAH-CTD there was no difference in all-cause death between the treatment groups at the end of the study or at fixed time points during the study. There were few deaths that contributed to the primary endpoint, although a greater number were observed in the selexipag group than in the placebo group. It is highly likely that this difference occurred because of the composite nature of the primary endpoint, which is concerned with each patient's first event of morbidity or mortality up to end of treatment. Patients who experienced a non-fatal primary endpoint event subsequently discontinued double-blind treatment and did not contribute further events, including death, to the primary endpoint; this is referred to as informative censoring. In the intent-to-treat analysis of all-cause death up to the end of the study, deaths that contributed to the primary endpoint and all other deaths are captured. The latter occurred primarily in patients who had already experienced a non-fatal primary endpoint event. These patients were no longer on double-blind treatment and could have been receiving further PAH therapy, including open-label selexipag or intravenous prostacyclin analogues, at the discretion of the investigator. The effect of this crossover can be estimated using modelling techniques, and results from the overall GRIPHON population favour selexipag [21]. These considerations highlight some of the challenges associated with interpreting the number of deaths in a study that was not designed to evaluate mortality alone, and emphasise that mortality assessments in such studies should be interpreted with caution.

In the PAH-CTD subgroup, and in the PAH-SSc and PAH-SLE subtypes, the effect of treatment on 6-min walk distance was similar to that observed in the overall GRIPHON population. In the PAH-CTD subgroup, the response was driven by a greater deterioration among placebo-treated patients compared with selexipag-treated patients. This deterioration was even more pronounced among PAH-SSc patients. This is not surprising given the extent of musculoskeletal involvement in SSc, and is consistent with another PAH-CTD study [19]. In contrast, the treatment effect on 6-min walk distance in PAH-SLE patients was driven by an improvement in the selexipag group compared with almost no change in the placebo group. This observation is particularly important given the paucity of published data in PAH-SLE patients. The patients evaluated in our study were prevalent and the majority were already receiving PAH treatment. In this context, improving exercise capacity with additional therapy is challenging. The relatively modest improvement in 6-min walk distance contrasts with the more pronounced treatment response for the primary endpoint. This further emphasises the lack of association between improvements in 6-min walk distance and delay in PAH progression [22], and supports a recent report showing that, in prevalent PAH patients, preventing deterioration in 6-min walk distance may be of greater prognostic relevance than ensuring improvements [23].

For the GRIPHON PAH-CTD subgroup, the NT-proBNP results are of particular interest as they are not affected by comorbidities associated with the underlying disease, such as musculoskeletal impairment. In addition, the samples were analysed at a central laboratory, thereby minimising variability between centres. In the PAH-CTD subgroup, as well as in the three CTD subtypes, the treatment effect with respect to NT-proBNP was comparable with the overall GRIPHON population [10]. The results in PAH-SSc patients are particularly encouraging given their relatively high baseline NT-proBNP levels. Although promising, these results should be interpreted with caution given the low patient numbers and wide confidence intervals.

Patients with PAH-CTD often have a high symptom burden due to comorbid musculoskeletal and gastrointestinal involvement and may be receiving numerous concomitant therapies [24]. We may therefore expect poorer tolerability among PAH-CTD patients compared with other PAH patients. However, selexipag tolerability in patients with PAH-CTD was generally consistent with that in the overall GRIPHON population; selexipag treatment discontinuation rates due to adverse events were only slightly higher in the PAH-CTD subgroup (19.2%) than in the overall GRIPHON population (14.3%) [10]. These data are encouraging in the context of data for other drugs that target the prostacyclin pathway, which show discontinuation rates of 10–14% over much shorter treatment periods [25–27]. In our study, most adverse events that occurred reflect the mode of action of selexipag on the IP receptor (e.g. headache, diarrhoea and nausea) and the distribution of patients in the high-, medium- and low-dose groups was similar between PAH-CTD patients and the overall GRIPHON population. Coupled with the consistency in the treatment effect for the primary endpoint, these data support the approach of individualised dosing based on tolerability in patients with PAH-CTD.

These analyses are subject to a number of limitations. Although the PAH-CTD population was a pre-specified subgroup for evaluating the primary endpoint, the more detailed analyses described here are exploratory in nature. In addition, the classification of CTD subtype was recorded by the investigator without adjudication, and no descriptions of serology or other disease-specific parameters can be provided.

Conclusions

The GRIPHON study comprises the largest population of PAH-CTD patients studied to date in a prospective randomised controlled trial. Evaluation of these patients has highlighted differences in patient characteristics and disease course depending on the underlying CTD. In our study, selexipag treatment was well tolerated and delayed the progression of PAH irrespective of CTD subtype and baseline PAH therapy. These data support the use of multiple PAH therapies when treating patients with PAH-CTD and emphasise that this treatment strategy can yield benefits in a population who had previously been considered difficult to treat.

Supplementary material

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Figure S1. Effect of selexipag on the primary composite endpoint of morbidity/mortality in patients with PAH-CTD or IPAH/HPAH ERJ-02493-2016_Figure_S1 (369.1KB, pdf)

Table S1. Individualised maintenance dose ERJ-02493-2016_Table_S1 (17.8KB, pdf)

Table S2. Events related to pulmonary arterial hypertension and death ERJ-02493-2016_Table_S2 (16.7KB, pdf)

Table S3. Number of deaths from any cause up to end of study in the placebo and selexipag arms among patients with PAH-CTD ERJ-02493-2016_Table_S3 (9.3KB, pdf)

Table S4. Cause of death for all deaths up to end of study in patients with PAH-CTD ERJ-02493-2016_Table_S4 (19KB, pdf)

Table S5. Change from baseline in 6-minute walk distance at week 26 ERJ-02493-2016_Table_S5 (13.8KB, pdf)

Table S6. Change in N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide from baseline to week 26 ERJ-02493-2016_Table_S6 (18.7KB, pdf)

Table S7. Most frequent adverse events in patients with PAH-SSc, PAH-SLE or PAH-MCTD/-CTD-other ERJ-02493-2016_Table_S7 (46.3KB, pdf)

Table S8. Prostacyclin-associated adverse events reported in the study titration and maintenance periods for PAH-CTD subtypes ERJ-02493-2016_Table_S8 (40.9KB, pdf)

Disclosures

S. Gaine ERJ-02493-2016_Gaine (1.2MB, pdf)

K. Chin ERJ-02493-2016_Chin (1.2MB, pdf)

G. Coghlan ERJ-02493-2016_Coghlan (1.2MB, pdf)

R. Channick ERJ-02493-2016_Channick (1.2MB, pdf)

L. Di Scala ERJ-02493-2016_Di_Scala (1.2MB, pdf)

N. Galie ERJ-02493-2016_Galie (1.2MB, pdf)

H-A. Ghofrani ERJ-02493-2016_Ghofrani (1.2MB, pdf)

I.M. Lang ERJ-02493-2016_Lang (1.2MB, pdf)

V. McLaughlin ERJ-02493-2016_McLaughlin (1.2MB, pdf)

R. Preiss ERJ-02493-2016_Preiss (1.2MB, pdf)

L.J. Rubin ERJ-02493-2016_Rubin (1.2MB, pdf)

G. Simonneau ERJ-02493-2016_Simmoneau (1.2MB, pdf)

O. Sitbon ERJ-02493-2016_Sitbon (1.2MB, pdf)

V.F. Tapson ERJ-02493-2016_Tapson (1.2MB, pdf)

M.M. Hoeper ERJ-02493-2016_Hoeper (1.2MB, pdf)

Acknowledgements

Medical writing assistance was provided by Anoushka Thomas (nspm ltd, Meggen, Switzerland) and funded by Actelion Pharmaceuticals Ltd (Allschwil, Switzerland).

Footnotes

This article has supplementary material available from erj.ersjournals.com

This study is registered with www.clinicaltrials.gov identifier number NCT01106014.

Support statement: This study was supported by Actelion Pharmaceuticals. Funding information for this article has been deposited with the Crossref Funder Registry.

Conflict of interest: Disclosures can be found alongside this article at erj.ersjournals.com

References

- 1.Mathai SC, Hassoun PM. Pulmonary arterial hypertension in connective tissue diseases. Heart Fail Clin 2012; 8: 413–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McLaughlin V, Humbert M, Coghlan G, et al. Pulmonary arterial hypertension: the most devastating vascular complication of systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009; 48: Suppl. 3, iii25–iii31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Humbert M, Sitbon O, Chaouat A, et al. Pulmonary arterial hypertension in France: results from a national registry. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006; 173: 1023–1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kähler CM, Colleselli D. Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) in connective tissue diseases. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2006; 45: Suppl. 3, iii11–iii13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rhee RL, Gabler NB, Sangani S, et al. Comparison of treatment response in idiopathic and connective tissue disease-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015; 192: 1111–1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson SR, Granton JT. Pulmonary hypertension in systemic sclerosis and systemic lupus erythematosus. Eur Respir Rev 2011; 20: 277–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Distler O, Pignone A. Pulmonary arterial hypertension and rheumatic diseases – from diagnosis to treatment. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2006; 45: Suppl. 4, iv22–iv25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pulido T, Adzerikho I, Channick R, et al. Macitentan and morbidity and mortality in pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med 2013; 369: 809–818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coghlan JG, Galie N, Barbera JA, et al. Initial combination therapy with ambrisentan and tadalafil in connective tissue disease-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension (CTD-PAH): subgroup analysis from the AMBITION trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2017; 76: 1219–1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sitbon O, Channick R, Chin KM, et al. Selexipag for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 2522–2533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Condliffe R, Howard LS. Connective tissue disease-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension. F1000Prime Rep 2015; 7: 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Condliffe R, Kiely DG, Peacock AJ, et al. Connective tissue disease-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension in the modern treatment era. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009; 179: 151–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schreiber BE, Connolly MJ, Coghlan JG. Pulmonary hypertension in systemic lupus erythematosus. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2013; 27: 425–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Farber HW, Miller DP, Poms AD, et al. Five-year outcomes of patients enrolled in the REVEAL Registry. Chest 2015; 148: 1043–1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chung L, Liu J, Parsons L, et al. Characterization of connective tissue disease-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension from REVEAL: identifying systemic sclerosis as a unique phenotype. Chest 2010; 138: 1383–1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Avouac J, Wipff J, Kahan A, et al. Effects of oral treatments on exercise capacity in systemic sclerosis related pulmonary arterial hypertension: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Ann Rheum Dis 2008; 67: 808–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rubin LJ, Badesch DB, Barst RJ, et al. Bosentan therapy for pulmonary arterial hypertension. N Engl J Med 2002; 346: 896–903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramjug S, Hussain N, Hurdman J, et al. Long-term outcomes of domiciliary intravenous iloprost in idiopathic and connective tissue disease-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension. Respirology 2017; 22: 372–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Humbert M, Coghlan JG, Ghofrani HA, et al. Riociguat for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension associated with connective tissue disease: results from PATENT-1 and PATENT-2. Ann Rheum Dis 2017; 76: 422–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mathai SC, Girgis RE, Fisher MR, et al. Addition of sildenafil to bosentan monotherapy in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J 2007; 29: 469–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.European Medicines Agency. European Public Assessment Report: Uptravi (selexipag) 2016. www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Public_assessment_report/human/003774/WC500207175.pdf Date last accessed: March 15, 2017. Date last updated: April 1, 2016.

- 22.Savarese G, Paolillo S, Costanzo P, et al. Do changes of 6-minute walk distance predict clinical events in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension? A meta-analysis of 22 randomized trials. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012; 60: 1192–1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Farber HW, Miller DP, McGoon MD, et al. Predicting outcomes in pulmonary arterial hypertension based on the 6-minute walk distance. J Heart Lung Transplant 2015; 34: 362–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rhee RL, Gabler NB, Praestgaard A, et al. Adverse events in connective tissue disease-associated pulmonary arterial hypertension. Arthritis Rheumatol 2015; 67: 2457–2465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tapson VF, Jing ZC, Xu KF, et al. Oral treprostinil for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension in patients receiving background endothelin receptor antagonist and phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor therapy (the FREEDOM-C2 study): a randomized controlled trial. Chest 2013; 144: 952–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jing ZC, Parikh K, Pulido T, et al. Efficacy and safety of oral treprostinil monotherapy for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension: a randomized controlled trial. Circulation 2013; 127: 624–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tapson VF, Torres F, Kermeen F, et al. Oral treprostinil for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension in patients on background endothelin receptor antagonist and/or phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor therapy (The FREEDOM-C Study): a randomized controlled trial. Chest 2012; 142: 1383–1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Please note: supplementary material is not edited by the Editorial Office, and is uploaded as it has been supplied by the author.

Figure S1. Effect of selexipag on the primary composite endpoint of morbidity/mortality in patients with PAH-CTD or IPAH/HPAH ERJ-02493-2016_Figure_S1 (369.1KB, pdf)

Table S1. Individualised maintenance dose ERJ-02493-2016_Table_S1 (17.8KB, pdf)

Table S2. Events related to pulmonary arterial hypertension and death ERJ-02493-2016_Table_S2 (16.7KB, pdf)

Table S3. Number of deaths from any cause up to end of study in the placebo and selexipag arms among patients with PAH-CTD ERJ-02493-2016_Table_S3 (9.3KB, pdf)

Table S4. Cause of death for all deaths up to end of study in patients with PAH-CTD ERJ-02493-2016_Table_S4 (19KB, pdf)

Table S5. Change from baseline in 6-minute walk distance at week 26 ERJ-02493-2016_Table_S5 (13.8KB, pdf)

Table S6. Change in N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide from baseline to week 26 ERJ-02493-2016_Table_S6 (18.7KB, pdf)

Table S7. Most frequent adverse events in patients with PAH-SSc, PAH-SLE or PAH-MCTD/-CTD-other ERJ-02493-2016_Table_S7 (46.3KB, pdf)

Table S8. Prostacyclin-associated adverse events reported in the study titration and maintenance periods for PAH-CTD subtypes ERJ-02493-2016_Table_S8 (40.9KB, pdf)

S. Gaine ERJ-02493-2016_Gaine (1.2MB, pdf)

K. Chin ERJ-02493-2016_Chin (1.2MB, pdf)

G. Coghlan ERJ-02493-2016_Coghlan (1.2MB, pdf)

R. Channick ERJ-02493-2016_Channick (1.2MB, pdf)

L. Di Scala ERJ-02493-2016_Di_Scala (1.2MB, pdf)

N. Galie ERJ-02493-2016_Galie (1.2MB, pdf)

H-A. Ghofrani ERJ-02493-2016_Ghofrani (1.2MB, pdf)

I.M. Lang ERJ-02493-2016_Lang (1.2MB, pdf)

V. McLaughlin ERJ-02493-2016_McLaughlin (1.2MB, pdf)

R. Preiss ERJ-02493-2016_Preiss (1.2MB, pdf)

L.J. Rubin ERJ-02493-2016_Rubin (1.2MB, pdf)

G. Simonneau ERJ-02493-2016_Simmoneau (1.2MB, pdf)

O. Sitbon ERJ-02493-2016_Sitbon (1.2MB, pdf)

V.F. Tapson ERJ-02493-2016_Tapson (1.2MB, pdf)

M.M. Hoeper ERJ-02493-2016_Hoeper (1.2MB, pdf)