Abstract

Objectives To examine the risk of relapse and time to relapse after discontinuation of antidepressants in patients with anxiety disorder who responded to antidepressants, and to explore whether relapse risk is related to type of anxiety disorder, type of antidepressant, mode of discontinuation, duration of treatment and follow-up, comorbidity, and allowance of psychotherapy.

Design Systematic review and meta-analyses of relapse prevention trials.

Data sources PubMed, Cochrane, Embase, and clinical trial registers (from inception to July 2016).

Study selection Eligible studies included patients with anxiety disorder who responded to antidepressants, randomised patients double blind to either continuing antidepressants or switching to placebo, and compared relapse rates or time to relapse.

Data extraction Two independent raters selected studies and extracted data. Random effect models were used to estimate odds ratios for relapse, hazard ratios for time to relapse, and relapse prevalence per group. The effect of various categorical and continuous variables was explored with subgroup analyses and meta-regression analyses respectively. Bias was assessed using the Cochrane tool.

Results The meta-analysis included 28 studies (n=5233) examining relapse with a maximum follow-up of one year. Across studies, risk of bias was considered low. Discontinuation increased the odds of relapse compared with continuing antidepressants (summary odds ratio 3.11, 95% confidence interval 2.48 to 3.89). Subgroup analyses and meta-regression analyses showed no statistical significance. Time to relapse (n=3002) was shorter when antidepressants were discontinued (summary hazard ratio 3.63, 2.58 to 5.10; n=11 studies). Summary relapse prevalences were 36.4% (30.8% to 42.1%; n=28 studies) for the placebo group and 16.4% (12.6% to 20.1%; n=28 studies) for the antidepressant group, but prevalence varied considerably across studies, most likely owing to differences in the length of follow-up. Dropout was higher in the placebo group (summary odds ratio 1.31, 1.06 to 1.63; n=27 studies).

Conclusions Up to one year of follow-up, discontinuation of antidepressant treatment results in higher relapse rates among responders compared with treatment continuation. The lack of evidence after a one year period should not be interpreted as explicit advice to discontinue antidepressants after one year. Given the chronicity of anxiety disorders, treatment should be directed by long term considerations, including relapse prevalence, side effects, and patients’ preferences.

Introduction

In anxiety disorders, chronic course trajectories and relapses after remission are common.1 2 3 4 5 6 Consequently, when combined with high prevalence rates and functional limitations,7 8 anxiety disorders score highly on burden of disease rankings.9 10 11 12 Optimising the long term prognosis, including prevention of relapse,13 is an important strategy to decrease the burden of disease related to anxiety.

In addition to cognitive behavioural therapy, antidepressants are a first line option for the treatment of anxiety disorders,14 15 as they are effective and generally well tolerated.16 17 Most (57%) patients with anxiety disorders who are being treated use drugs.18 As long term studies are scarce, whether antidepressants should also be regarded a first line treatment option for optimising long term prognosis remains largely unknown. International guidelines are therefore consensus based and advise continuation of treatment for variable durations (six to 24 months) and subsequent tapering of the antidepressant.18 In contrast to the guidelines’ advice, long term use is increasing, with nearly half of patients in the UK and approximately two thirds of those in the US continuing antidepressants for at least two years.19 20 21 Whether clinicians are unnecessarily medicalising their patients or whether guidelines are too optimistic by advising discontinuation of antidepressants after sustained remission remains unclear. This discrepancy calls for clarity regarding long term use of antidepressants: is discontinuation of antidepressants wise?

A previous meta-analysis, including studies up to 2008, reported that relapse occurred in 26-45% of patients with anxiety disorder who discontinued antidepressants.22 Continuing antidepressants seemed to be effective in preventing relapse, with protective summary odds ratios ranging from 0.20 to 0.38 in various anxiety disorders.22 Superiority of antidepressants to placebo was also shown for quality of life.23

Information on whether specific treatment or discontinuation strategies influence risk of relapse is scant and inconclusive. For example, whereas some studies reported fewer relapses when antidepressants were discontinued after sustained use,24 25 others reported that relapses occurred frequently when antidepressants were stopped after a prolonged period of use.26 27 28 Likewise, we do not know whether risk of relapse depends on the type of antidepressant, the mode of discontinuation (abrupt versus tapered), the duration of follow-up, and whether concomitant psychotherapy is allowed or whether comorbidity affects relapse risk after discontinuation of antidepressants.

With this meta-analysis, we aimed to verify, update, and extend current knowledge. We meta-analysed relapse prevention trials that included patients with anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) who responded to antidepressants, randomised these patients in a double blind fashion to either continuing the antidepressant or switching to placebo, assessed the prevalence of relapse per treatment group, and compared the risk of relapse or time to relapse between these groups. Additionally, we explored whether this relapse risk is related to the type of anxiety disorder, type of antidepressant, mode of discontinuation, duration of previous treatment, duration of follow-up, whether studies allowed concurrent psychotherapy, whether studies excluded comorbidity, and involvement of drug companies. Finally, we briefly report on tolerability, given the importance for daily clinical practice.

Methods

Literature search

We searched PubMed, Cochrane, and Embase (from inception to July 2016) for studies including patients with anxiety disorder who responded to antidepressants, which subsequently randomised patients to either continuing the antidepressant or switching to placebo and compared (time to) relapse between these groups. A librarian and NMB did the search by using (combinations of) free text and keywords indicating anxiety disorders, antidepressants, discontinuation, and randomised controlled trials (appendix 1 gives the search terms used). Language was unrestricted. This search was extended by scanning reference lists of relevant papers and searching trial registers including Clinicaltrials.gov, World Health Organization, Cochrane trials, GlaxoSmithKline, Roche, Novartis, and AstraZeneca.

Study selection criteria consisted of the following. (1) Studies focused on patients with panic disorder, agoraphobia, social phobia, generalised anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, PTSD, or specific phobia; comorbidity was allowed. (2) Patients were classified as responders after treatment with antidepressants; studies focusing on drug treatment while allowing concomitant psychotherapy were included. (3) A double blind, placebo controlled design was used, randomising patients to long term use of antidepressants (antidepressant group) or switching to placebo (placebo group). (4) Relapse and/or time to relapse were assessed after a follow-up period. (5) Articles not presenting original data or consisting of only abstracts were excluded. We used the definitions of response and relapse as used in the original studies.

Two independent raters (NMB and WDS) assessed titles and abstracts for eligibility. Two independent raters (NMB and RCB) then assessed the method sections of the selected articles and resolved disagreements through discussion. This method section was reported in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines.29

Data extraction

From each study, NMB and RCB independently extracted the following aspects for the active treatment phase: the anxiety disorder, inclusion and exclusion criteria, type and dosage of antidepressant, sample size, duration of treatment, definition of response, and proportion of responders. For the follow-up phase, we extracted sample size, age, duration of follow-up, definition of relapse, proportion of and time to relapse per treatment arm, corresponding statistics, mode of discontinuation (tapering versus abrupt), dropouts, tolerability, and withdrawal symptoms. Discrepancies were resolved by referral to the data of the original article. For each study, the odds ratio, indicating the odds of relapse in the placebo group relative to the odds of relapse in the antidepressant group, was based on the number of relapses per group and the total number of patients per group. We also used this information to calculate the corresponding confidence intervals and the prevalence of relapse per treatment group. For time to relapse, we used the hazard ratio and its corresponding confidence interval as reported by the individual studies. If not reported, estimations of the 95% confidence interval were based on methods described by Parmar and colleagues and Tierney and colleagues.30 31

Quality assessment and publication bias

To assess the quality of the studies, KMH and RCB scored studies independently by using the Cochrane tool for assessing risk of bias.32 Studies were scored “low risk,” “high risk,” or “unclear” on the domains random sequence generation and allocation concealment (selection bias), blinding of patients and providers (performance bias), blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias), incomplete outcome data (attrition bias), and selective reporting (reporting bias) (appendix 2). Because the blinding of patients may be breached by the experience of withdrawal symptoms, we considered the risk of bias to be high when antidepressants were discontinued abruptly, unless it was reported that adverse events after randomisation did not differ between groups. We considered attrition bias to be high when 15% or more of the total number of patients dropped out during follow-up. Consensus on the ratings was reached through discussion. We summed the number of items scoring “high” to obtain a summary score, which could range from 0 to 7, with low scores indicating a low risk of bias. The summary score was included in a meta-regression analysis as the variable “quality.”

To assess publication bias, we created funnel plots and used Duval and Tweedie’s trim and fill procedure provide an adjusted estimate of the odds ratios and hazard ratios.33 Importantly, funnel plot asymmetry can result from (a combination of) publication or other selection biases and poor methodological quality in small studies, but it may also be due to true heterogeneity, artefacts, and chance.34 35 Additionally, as the Duval and Tweedie trim and fill method relies on the assumption that publication bias is the only reason for funnel plot asymmetry,34 results should be interpreted with caution.

Meta-analysis

We did a random effects meta-analysis (DerSimonian-Laird method36) to summarise the difference in “proportion of relapse” between antidepressants and placebo. We used odds ratios and corresponding 95% confidence intervals to summarise data. Additionally, as the event under study (relapse) may be fairly common, the odds ratio may overestimate the risk ratio. To avoid overestimating results, we also used the risk ratio and its corresponding 95% confidence interval to summarise data. Although the DerSimonian-Laird method is widely used, this method tends to provide confidence intervals that are too narrow, resulting in inappropriate numbers of type I errors. To overcome this, reported confidence intervals are adjusted by means of the Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman method.37 38 39 P values for the random effects subgroup analyses are based on the Q test for heterogeneity using the Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman adjusted variance per subgroup.37 38 39 40 Meta-analysis was based on intention to treat samples or, if they were not available,41 42 on responder samples.

We defined subgroup analyses a priori and did them for the following categorical variables: type of anxiety disorder according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition (DSM-IV—generalised anxiety disorder, social phobia, panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, PTSD), with a separate analysis for anxiety disorders according to DSM-5 (which excludes obsessive-compulsive disorder and PTSD); type of antidepressant (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, other); mode of discontinuation (abrupt, taper or fluoxetine (which tapers by itself)); concurrent psychotherapy allowed (no/yes); whether (most) comorbidity was excluded (no/yes); and involvement of drug companies. We used meta-regression analysis to estimate the influence of the year of publication, the quality of individual studies, the duration of treatment, and the duration of follow-up on the outcomes of studies.

In a separate random effects meta-analysis, we examined the “time to relapse.” We used hazard ratios and corresponding 95% confidence intervals to summarise these data, with hazard ratios reflecting the hazard rate of time to relapse in the placebo group divided by the hazard rate of time to relapse in the antidepressant group.

In addition to the meta-analyses for the relative treatment effects (odds ratio of relapse, hazard ratio of time to relapse), we calculated summary prevalence of relapse per treatment group (antidepressant group, placebo group) and summary prevalence of dropout per treatment group (antidepressant group, placebo group) and the corresponding 95% confidence intervals by using random effects meta-analyses. The summary relapse prevalence per treatment group is of more direct relevance to clinicians and patients for making informed treatment decisions, although its generalisability may be more limited than that of relative effect measures.43 The summary relapse summarises the number of participants relapsing per treatment group relative to the total number of participants in that group. Prevalences per treatment group were weighted for group sample size of the individual studies. The summary dropout prevalences per treatment group were created in analogue to the summary relapse prevalences per treatment group.

We used random effect models for the meta-analyses because we expected heterogeneity across studies. The Q statistic and I2 were reported as measures for heterogeneity between studies. I2 reflects observed heterogeneity in percentages, with 0% indicating no heterogeneity and 25%, 50%, and 75% considered to be low, medium, and high levels of heterogeneity.44 We used RevMan to produce forest plots to visualise summary odds ratios, summary hazard ratios, and their corresponding confidence intervals.45 We used the software package Comprehensive Meta Analysis, version 3.3.070, for analyses.46

Patient involvement

The Dutch patient association for anxiety disorders (angst, dwang en fobiestichting: www.adfstichting.nl) often receives questions about medication policies after the acute phase, and therefore welcomes this meta-analysis. The association will inform patients about the results. Because this study is a meta-analysis, no patients were involved in the design. No patient involvement was reported in the original studies.

Results

Flowchart

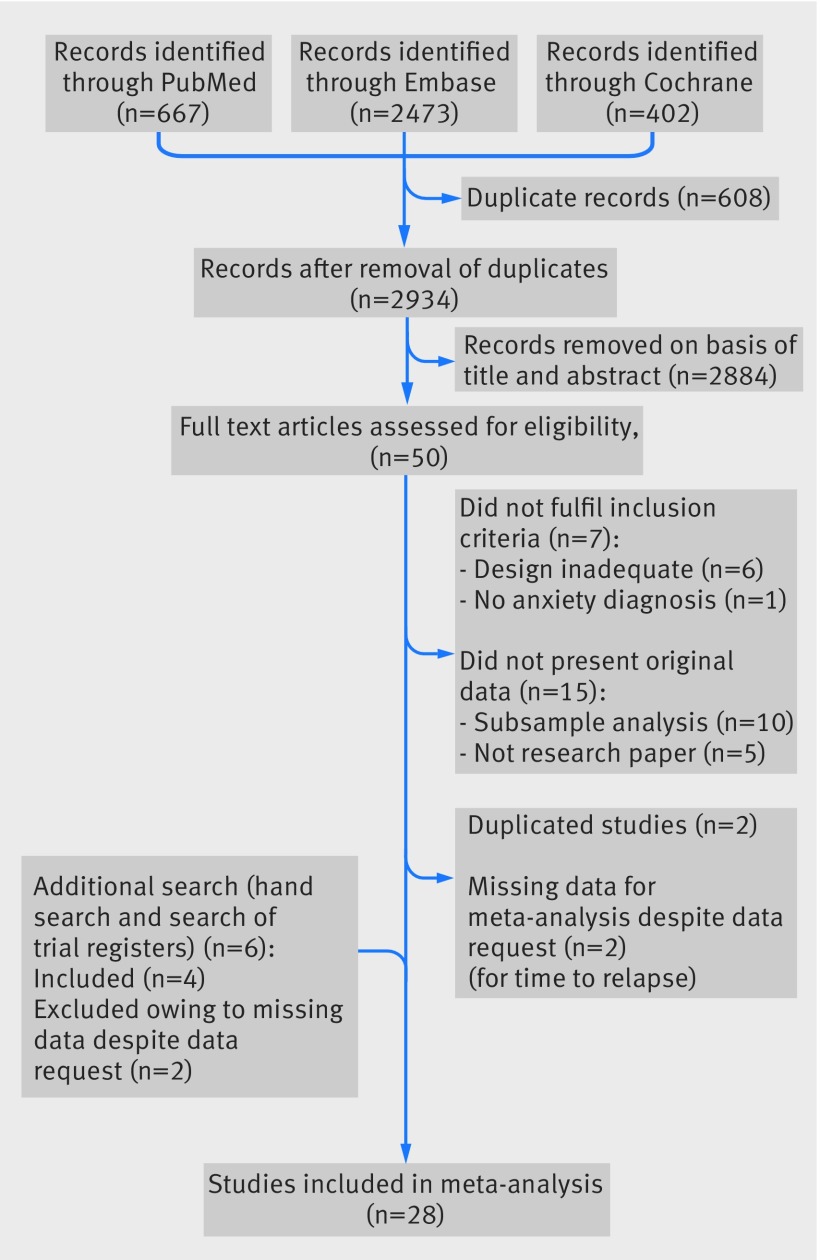

The literature search resulted in 2934 records. Of these, we assessed 50 full text articles for eligibility and included 24 (fig 1). Six unpublished studies were identified by hand searching and by searching clinical trials registers. Of these, two could not be included owing to missing data, as data were not provided on request. One of the articles with missing data concerned a study with a non-significant trend favouring continuation treatment47 48; the other is registered on clinicaltrials.gov,49 but the results are not described. We included the remaining four unpublished studies,50 51 52 53 all conducted by GlaxoSmithKline. This resulted in a total of 28 studies meeting inclusion criteria for proportion of relapse.24 41 42 48 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 Eleven of these also reported on time to relapse.24 54 55 56 57 58 60 68 70 72 73 Data about the corresponding 95% confidence interval of the hazard ratios was unavailable for two studies and not provided by the authors on request,24 54 so we based estimations of the 95% confidence intervals on methods described elsewhere.30 31

Fig 1 Flowchart of literature search

Characteristics of studies

The 28 included studies examining relapse were published between 1995 and 2012 (appendix 3). Sample sizes of the relapse prevention phase ranged from 15 to 561, resulting in 2625 patients in the antidepressant group and 2608 in the placebo group (total n=5233). Six studies focused on panic disorder, five on social phobia, six on generalised anxiety disorder, seven on obsessive-compulsive disorder, and four on PTSD. The duration of treatment ranged from eight to 52 weeks, as did the duration of follow-up. Two studies had a variable duration of follow-up of 24-76 week and 24-56 weeks.55 56 Because all patients in these two studies had an assessment at 24 weeks, we used data at 24 weeks as the outcome for these studies. The second meta-analysis examining time to relapse was based on 11 studies with 1511 patients in the antidepressant group and 1491 patients in the placebo group (total n=3002). The duration of follow-up ranged from 24 to 28 weeks. One study had a variable duration of follow-up of 24-56 weeks.56 We assessed bias in all studies by using the Cochrane tool.32 Performance bias related to blinding of providers and detection bias was rated low in all studies. By contrast, attrition bias was present in most studies. Across studies, the summary score ranged from 0 to 3, with two studies scoring 0, 14 studies scoring 1, 10 studies scoring 2, and two studies scoring 3 (see appendix 2). Thus, the risk of bias was generally low.

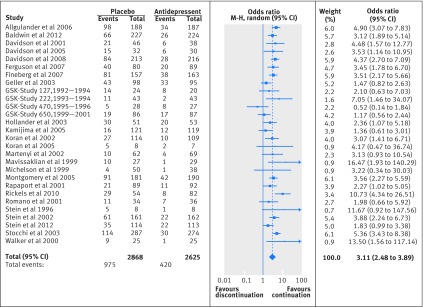

Proportion of relapse

The summary odds ratio of relapse was 3.11 (95% confidence interval 2.48 to 3.89; n=28 studies) for patients in the placebo group relative to patients in the antidepressant group (table 1; fig 2), indicating that more patients relapsed after discontinuation of antidepressants than when antidepressants were continued for studies with a duration of follow-up ranging between eight and 52 weeks. The Q statistics provided no indications of significant dispersion across studies (Q=29.37, df=27, P=0.34). Based on I2, 8.07% of the total variance was related to true heterogeneity between studies. Inspection of the funnel plot (appendix 4) seems to show some asymmetry, which could indicate small study effects. The Duval and Tweedie trim and fill procedure suggested little change in the odds ratio after adjustment (summary adjusted odds ratio 2.98, 2.39 to 3.72; n=28 studies). The summary risk ratio was 2.21 (1.85 to 2.64; n=28 studies), indicating that the odds ratio overestimates the risk ratio for relapse.

Table 1.

Results of mixed effect meta-analysis and mixed effect subgroup analyses of studies on relapse after discontinuation of antidepressants in anxiety disorders

| Meta-analysis/subgroup analysis | References | No of studies | Odds ratio (95% CI)* | Q | I2 | DF (Q) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relapse | 28 | 3.11 (2.48 to 3.89) | 29.37 | 8.07 | 27 | ||

| Anxiety DSM-IV: | 28 | 3.03 (2.44 to 3.78) | 30.24 | 10.73 | 4 | 0.29 | |

| Generalised anxiety disorder | 24, 48, 54-57 | 6 | 4.20 (2.42 to 7.28) | 6.26 | 20.11 | 5 | |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | 50, 58-63 | 7 | 2.43 (1.74 to 3.38) | 2.32 | 0 | 6 | |

| Panic disorder | 42, 51, 64-67 | 6 | 2.88 (1.37 to 6.03) | 5.47 | 8.59 | 5 | |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 41, 53, 68, 69 | 4 | 2.45 (0.86 to 6.97) | 3.21 | 6.50 | 3 | |

| Social phobia | 52, 70-73 | 5 | 3.19 (1.02 to 9.95) | 8.61 | 53.56 | 4 | |

| Anxiety DSM-5: | 17 | 3.55 (2.53 to 4.98) | 19.92 | 19.67 | 2 | 0.58 | |

| Generalised anxiety disorder | 24, 48, 54-57 | 6 | 4.21 (2.40 to 7.37) | 5.45 | 8.19 | 5 | |

| Panic disorder | 42, 51, 64-67 | 6 | 2.92 (1.37 to 6.22) | 5.10 | 1.96 | 5 | |

| Social phobia | 52, 70-73 | 5 | 3.17 (0.97 to 10.40) | 8.12 | 50.74 | 4 | |

| Antidepressant: | 28 | 3.33 (2.65 to 4.17) | 29.14 | 7.34 | 2 | 0.25 | |

| SSRI | 41, 42, 50-55, 58-61, 63, 66-73 | 21 | 2.86 (2.17 to 3.78) | 20.73 | 3.54 | 20 | |

| SNRI | 24, 48, 65 | 3 | 5.03 (1.31 to 19.40) | 2.19 | 8.62 | 2 | |

| Other | 56, 57, 62, 64 | 4 | 2.92 (1.03 to 8.23) | 3.20 | 6.14 | 3 | |

| Discontinuation: | 28 | 3.05 (2.44 to 3.81) | 32.16 | 16.03 | 1 | 0.10 | |

| Abrupt | 50, 51, 56, 57, 59, 60, 66-68, 70, 73 | 11 | 2.52 (1.80 to 3.52) | 8.60 | 0 | 10 | |

| Taper | 24, 41, 42, 48, 52-55, 58, 61-65, 69, 71, 72 | 17 | 3.61 (2.60 to 5.02) | 20.69 | 22.66 | 16 | |

| Concurrent psychotherapy allowed: | 28 | 3.17 (2.54 to 3.95) | 32.44 | 16.78 | 1 | 0.10 | |

| No | 50, 53, 56-63, 65, 68-70, 73 | 15 | 2.64 (2.06 to 3.37) | 9.69 | 0 | 14 | |

| Yes | 24, 41, 42, 48, 51, 52, 54, 55, 64, 66, 67, 71, 72 | 13 | 3.86 (2.49 to 5.98) | 19.45 | 38.30 | 12 | |

| Comorbidity mostly excluded: | 28 | 3.11 (2.45 to 3.93) | 29.87 | 9.62 | 1 | 0.62 | |

| No | 41, 42, 59, 60, 63, 64, 66, 68, 71, 73 | 10 | 2.82 (1.74 to 4.57) | 8.21 | 0 | 9 | |

| Yes | 24, 48, 50-58, 61, 62, 65, 67, 69, 70, 72 | 18 | 3.20 (2.37 to 4.32) | 21.42 | 20.63 | 17 |

DSM=Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; SNRI=serotonin-noradrenalin reuptake inhibitor; SSRI=selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

*All confidence intervals are Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman adjusted.

Fig 2 Forest plot representing odds ratios of relapse per study

Subgroup analyses and meta-regression analyses

We did several exploratory subgroup analyses (table 1). In line with the indications of limited heterogeneity across studies by Q and I2, type of anxiety disorder, type of antidepressant, mode of discontinuation, allowing concurrent psychotherapy, and exclusion of comorbidity did not statistically affect the odds ratio of relapse. Likewise, outcomes seemed statistically unrelated to year of publication (P=0.25), quality of the studies based on Cochrane tool for assessing risk of bias (P=0.44),32 duration of treatment (P=0.95), or duration of follow-up (P=0.24). Although planned, we did not do a subgroup analysis on the involvement of drug companies, as these were involved in all but two small studies.64 71

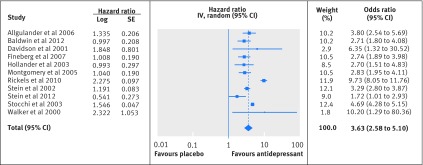

Time to relapse

Analysis showed that discontinuation of antidepressant resulted in a shorter time to relapse in the placebo group than in the antidepressant group (summary hazard ratio 3.63, 2.58 to 5.10; n=11 studies) (fig 3). The hazard ratio reflects the total follow-up period, ranging from 24 to 28 weeks with one study having a variable duration of 24-56 weeks.56 The Q statistic provided no indications of significant dispersion across studies (Q=9.85, df=10, P=0.45). Furthermore, I2 is 0% as the number of degrees of freedom is higher than the value of Q. Owing to the limited number of studies, we did no subgroup analyses or meta-regression analyses. On the basis of the funnel plot, few small study effects were present, although the limited number of studies precludes a firm conclusion (appendix 5).

Fig 3 Forest plot representing hazard ratios of time to relapse per study

Relapse prevalence per treatment group

In addition to the meta-analyses for the relative treatment effects (odds ratio of relapse, hazard ratio of time to relapse), we calculated summary relapse prevalences per treatment group. The summary relapse prevalences per treatment group are based on studies (n=28) with follow-up duration ranging from eight to 52 weeks. The summary relapse prevalence in the antidepressant group indicated that 16.4% (95% confidence interval 12.6% to 20.1%) of the patients relapsed. The Q statistic provided no indications of significant dispersion across studies (Q=32.9, df=27, P=0.20), and on the basis of I2 18.0% of the total variance was related to true heterogeneity between studies. The summary relapse prevalence in the placebo group was 36.4% (30.8% to 42.1%). There were no indications of significant dispersion across studies (Q=37.3, df=27, P=0.09). Moreover, an I2 of 27.6% indicated that the heterogeneity between studies was low.

Tolerability, dropouts, and withdrawal symptoms

Data on tolerability and withdrawal symptoms were limited and non-systematic in the studies included, not allowing a meta-analysis. Most studies reported to some extent on adverse events during follow-up and concluded that antidepressants were well tolerated over time. Side effects of antidepressants that were mentioned most often included headache, infections of the upper respiratory tract, influenza-like symptoms, nausea, and insomnia. Dropouts (excluding those for lack of efficacy) were relatively higher in the placebo group than the antidepressant group (summary odds ratio 1.31, 1.06 to 1.63; n=27 studies) across studies with a follow-up duration ranging from eight to 52 weeks. No significant dispersion was detected (Q=27.1, df=26, P=0.40), and I2 was 4.1% indicating low heterogeneity across studies. Moreover, the summary prevalence of dropout was 21.9% (15.3% to 28.5%) in the placebo group and 17.2% (13.5% to 20.9%) in the antidepressant group, both across studies with a follow-up duration ranging from eight to 52 weeks. For the summary prevalence of dropout, the Q statistics provided no indications of significant dispersion across studies in either group (antidepressant group Q=32.4, df=26, P=0.18; placebo group Q=34.4, df=26, P=0.13). Furthermore, I2 in the placebo group (24.3%) and in the antidepressant group (19.8%) indicated that heterogeneity was low. Higher dropout rates in the placebo group could possibly be due to withdrawal symptoms in the placebo group. However, four studies that specifically reported on withdrawal symptoms stated that there were generally no differences between groups,48 60 70 73 suggesting that adverse effects of antidepressants in the antidepressant group and withdrawal symptoms in the placebo group were balanced. Alternatively, the higher dropout rates in the placebo group might be a masked effect of lack of efficacy. Lack of efficacy can be interpreted as a (partial or beginning) relapse, because all patients were classified as responders before randomisation. If patients who discontinue antidepressants drop out of treatment more often because of lack of efficacy, this would only strengthen our conclusion that those who discontinue antidepressants run a higher risk of relapse.

Discussion

Optimising the long term prognosis should be an over-riding priority when treating patients with anxiety disorders, because relapse and chronicity are common. This meta-analysis examined the risk of relapse when discontinuing antidepressants in patients with anxiety disorder who responded to antidepressant treatment. On the basis of many randomised controlled trials of high quality, we have shown a clear benefit of continuing treatment compared with discontinuation for both relapse (summary odds ratio 3.11, 2.48 to 3.89; n=28 studies) and time to relapse (summary hazard ratio 3.63, 2.58 to 5.10; n=11 studies). None of the subgroup analyses or meta-regression analyses reached statistical significance.

Certain aspects of the study population and design may have affected either or both outcomes. Firstly, most studies in this meta-analysis excluded comorbidity to some extent. Given that comorbidity in anxiety disorders is common and associated with chronicity,1 relapse rates in clinical practice are presumably higher. In our subgroup analysis, we found no statistical effect of comorbidity on relapse rates. However, in their randomised controlled trial,59 Geller and colleagues found that comorbidity primarily increased relapse rates in the placebo group; for example, in the placebo group, the relapse rate was 33% in patients without comorbid disorders and 55% and 77% for those with one or more and two or more disorders, respectively. Geller’s findings suggest that the benefits of continuing treatment are greater for patients with comorbidity than for those without comorbidity.

Secondly, summary relapse prevalence was 36.4% (30.8% to 42.1%; n=28 studies) in the placebo group compared with 16.4% (12.6% to 20.1%, n=28 studies) in the antidepressant group. Duration of follow-up in the individual studies ranged between eight and 52 weeks. Falsely interpreting withdrawal symptoms in the placebo group as relapse would overestimate the protective effect of continuing antidepressants. However, the higher relapse rate in the placebo group is probably attributable to withdrawal symptoms—that is, most of the studies tapered antidepressants thereby diminishing withdrawal symptoms. In addition, 10 studies required symptoms to be present on successive visits,24 42 52 59 61 64 65 66 67 71 whereas withdrawal symptoms are transient.74 Also, five studies did post hoc analyses excluding relapses occurring when withdrawal symptoms are most likely (that is, the first seven, 14, or even 28 days after discontinuation) and reported that superiority of antidepressants over placebo remained similar.55 56 58 65 70

Thirdly, various criteria for response and relapse were used in the individual studies. Using a low threshold to define responders will include patients with residual symptoms in the discontinuation phase, who may run a higher risk for relapse,75 and hence relapse rates may increase. Fourthly, only relapses of the disorder under study have been included. Given the low stability of anxiety disorders over time,6 the rate of development of “any disorder” is likely to be substantially higher.

Strengths and weaknesses of study

This meta-analysis summarised the findings of 28 studies, including a total of 5233 patients. This produces more robust estimates than individual studies. By conducting this meta-analysis, we verified, updated, and extended a previous meta-analysis on this subject.22 We included six additional studies, increasing the total number of patients from 4121 to 5233; summarised studies of all anxiety disorders combined; assessed time to relapse as an additional outcome parameter; used a more conservative random effects model; assessed publication bias; did exploratory subgroup analyses and meta-regression analyses; assessed the quality of the included studies; considered dropout rates; and presented adverse events in the follow-up phase. Another strength of our study is that we included only trials with a fixed treatment period. By contrast, observational studies, allowing a flexible duration of the open label phase, are prone to bias favouring continuation of treatment.76

Drug companies were involved in all except two small studies.64 71 Hence, we should be aware of the probability of both publication bias and sponsorship bias.77 To limit potential bias, we thoroughly searched for non-published studies and included these if sufficient information was available. We found six unpublished studies, four with negative results, one with positive results, and one with unknown results, thereby suggesting publication bias. Two of these could not be included due to a lack of information. One showed a non-significant trend favouring continuation treatment47; inclusion of this study in the meta-analysis might have slightly attenuated the summary odds ratio. The potential effect on the summary odds ratio of the second study is unknown, as the necessary data are unavailable.49 Four of the unpublished studies provided sufficient information and could be included in the meta-analysis.50 51 52 53 Three of these unpublished studies found no significant effect of continuation treatment, and one found a positive effect of continuation treatment. Including these unpublished studies has resulted in a lower odds ratio compared with excluding (the four) unpublished studies (for example, excluding unpublished studies, odds ratio=3.38, 2.76 to 4.12; including unpublished studies, odds ratio=3.11, 2.50 to 3.86).

To further assess potential biases, we examined whether selective reporting was present in individual studies. We found several indications of selective reporting. In four articles, the abstract was incomplete.42 62 69 71 In addition, one study had planned to analyse time to relapse with a Cochran-Mantel-Haenzel test but did not report test results,48 and three studies reported the hazard ratio for time to relapse but gave incomplete information about the 95% confidence interval.24 54 58 Irrespective of whether these shortcomings are related to the involvement of drug companies, it seems unlikely that they change our conclusion for the following reasons: we most likely included most unpublished studies in the meta-analysis; adjusting odds ratios attenuated the strength of the association, but the protective effect of continuing antidepressants remained substantial; missing confidence intervals were estimated and included in meta-analysis; and a meta-regression on the quality of studies (including the aspect of selective reporting) was not statistically significant.

We did subgroup analyses, which showed no statistical significant differences. Findings of subgroup analyses should, however, be interpreted cautiously, because statistical power to detect genuine differences is limited. Moreover, these are observational comparisons; studies included in the subgroup analysis may differ in other aspects too. Only direct comparisons can verify whether risk of relapse might be related to type of anxiety disorder, type of antidepressant, mode of discontinuation, duration of treatment and follow-up, comorbidity, and allowance of concurrent psychotherapy. In addition, a network meta-analysis is worth considering to extend the meta-regression analyses.

Moreover, the reported summary relapse prevalences per treatment group should be interpreted with caution because individual studies differ with regard to their follow-up duration, ranging from eight to 52 weeks. A final limitation is that the maximum duration of treatment was limited to 52 weeks. Randomised studies with a longer duration do not exist. Up until one year, we found a clear advantage of continuing antidepressants. However, on the basis of our meta-analysis, we cannot determine whether a relatively “safe” period exists after 52 weeks of treatment when antidepressants can be discontinued without the associated risk of relapse.

Clinical implications and guideline recommendations

Altogether our results imply that, for a treatment duration of up to one year, antidepressants outperform placebo in preventing relapse and are well tolerated over time. Additionally, antidepressants seem to be superior to placebo in terms of quality of life,23 and direct medical costs associated with relapse might offset the costs of antidepressants.78 Although most guidelines recommend one year of follow-up, some advise shorter periods for specific anxiety disorders (for example, panic disorder14 79); these recommendations may need reconsideration.

We have no definite answer as to whether discontinuing antidepressants earlier—that is, within a year—is unwise. Our exploratory meta-regression analysis assessing the effect of duration of treatment was statistically non-significant. In line with this, time to restarting an antidepressant was found to be similar in patients who discontinued antidepressants within six months and those who continued antidepressants for six to 12 months.80

Likewise, as studies included in this meta-analysis had a treatment duration up to one year, we have no answer as to whether patients should continue or may safely discontinue their antidepressants after this period. On the one hand, we can hypothesise that with longer durations of treatment, improvement continues and functioning improves, thereby drifting further away from a relapse. On the other hand, in a study with a naturalistic design, relapse rates after discontinuation were high, even after three years of sustained remission on treatment.26 Given the importance of this for daily clinical care, randomised controlled trials with long treatment durations are needed in patients who responded to antidepressants. These studies should directly compare various durations of treatment. To date, such studies have been done by Rickels and colleagues and by Mavissakalian and Perel.24 28 Both studies had small sample sizes, and, additionally, in part of the sample of Mavissakalian and Perel, discontinuation was not blinded. Results were contradictory. Rickels and colleagues found significantly higher relapse rates following discontinuation in patients treated for six months (53.7%) than in those patients treated for 12 months (32.4%).24 In contrast, Mavissakalian and Perel found similar relapse rates in patients who were treated for six months and in those who were treated for 12-30 months before discontinuation.28 Until more data become available, no rational advice can be provided to patients to optimise their long term prognosis after this period of one year. We emphasise that the guidelines’ advice to continue treatment for a year should not be interpreted as advice to taper drugs after this period. Thus, by suggesting tapering of drugs following sustained remission, current guidelines are too optimistic. Unfortunately, the discussion as to whether discontinuing antidepressants is wise often does not take place between doctors and their patients.81

As described above, continuing antidepressants decreases the risk of relapse and thereby improves the long term prognosis. However, when 36.4% of the patients relapse, 63.6% do not. In other words, most patients do well when discontinuing treatment. Furthermore, relapse may also occur during continuation of antidepressants (16.4%). In addition to relapse, patients’ preferences and adverse effects should be taken into account when deciding whether to continue or discontinue antidepressants. Some patients have an aversion to antidepressants or view long term use as problematic.82 83 According to clinical experience, patients find side effects more difficult to accept in a remitted state than in the acute phase of their disorder. Moreover, research conducted among patients in primary care who use antidepressants predominantly because of anxiety or depressive disorders has shown the importance of side effects for patients; for a substantial minority, the efficacy of antidepressants does not outweigh the side effects.82 Doctors should inform patients about the risk of relapse and decide collaboratively with the patient whether the benefits of discontinuation are worth the risk of relapse in their specific case.

To improve knowledge about the advantages and disadvantages of antidepressant discontinuation, some important research questions need to be answered. Firstly, there are indications that for some patients, drug treatment is less effective when reinstated after relapse. This is important because relapse could then turn into chronicity. Secondly, whether specific psychological interventions may decrease relapse after discontinuation is unknown. Lastly, insight into predictors of relapse may enable a personal risk estimate.

Conclusions

Anxiety disorders often run a chronic course, so long term considerations should direct treatment. In the acute phase, both cognitive behavioural therapy and antidepressants can be considered. When considering antidepressants in acute phase treatment, the relapse risk in the case of later discontinuation needs to be discussed and evaluated from the start of the treatment. On the basis of the evidence presented here, the advice is to continue antidepressants for at least a year. After this period, no evidence based advice can be provided. The lack of evidence after this period should not be interpreted as explicit advice to discontinue antidepressants after one year. Guidelines that suggest tapering antidepressants following sustained remission should be reworded. When deciding to continue or discontinue antidepressants in individual patients, the relapse risk should be considered in relation to side effects and the patient’s preferences. Patients and their doctors need to exchange views on what seems best for the individual patient in the long term.

What is already known on this topic

Antidepressants are a first line treatment option for the acute treatment of anxiety disorders, but their benefits in optimising long term prognosis are less well known

International guidelines are therefore consensus based and advise continuing treatment for a variable time (six to 24 months) and subsequent tapering of the antidepressant

Previous studies have shown a high risk of relapse after discontinuation of antidepressants, but information on whether specific strategies influence relapse risk is scant and inconclusive

What this study adds

This meta-analysis of 28 relapse prevention trials in patients with remitted anxiety disorders found a clear benefit of continuing treatment up to one year for both relapse rate and time to relapse

Relapse risk was not significantly influenced by type of anxiety disorder, duration of previous treatment, duration of follow-up, mode of discontinuation, or concurrent psychotherapy

Web Extra.

Extra material supplied by the author

Appendix 1-5

We thank Caroline Planting of the VU University Medical Center library for her help with conducting the literature search and Adriaan Hoogendoorn for his statistical advice.

Contributors: NMB, AM, WDS, KMH, and AJLMvB devised the concept and design of the study. NMB, WDS, and RCB assessed studies for eligibility and extracted the information from all articles. RCB and AM did the analyses, and all authors interpreted the data. NMB and RCB drafted the article, and all authors revised it critically for important intellectual content and approved the version to be published. NMB and AJLMvB are the guarantors.

Funding: No funding/support was received for this work.

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf (available on request from the corresponding author) and declare: no support from any organisation for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous three years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethical approval: Not needed.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Transparency: The lead authors (the manuscript’s guarantors) affirm that this manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

References

- 1.Batelaan NM, Rhebergen D, Spinhoven P, van Balkom AJ, Penninx BW. Two-year course trajectories of anxiety disorders: do DSM classifications matter?J Clin Psychiatry 2014;75:985-93. 10.4088/JCP.13m08837 pmid:24912140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Spinhoven P, Batelaan N, Rhebergen D, van Balkom A, Schoevers R, Penninx BW. Prediction of 6-yr symptom course trajectories of anxiety disorders by diagnostic, clinical and psychological variables. J Anxiety Disord 2016;44:92-101. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2016.10.011 pmid:27842240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rhebergen D, Batelaan NM, de Graaf R, et al. The 7-year course of depression and anxiety in the general population. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2011;123:297-306. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01677.x pmid:21294714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruce SE, Yonkers KA, Otto MW, et al. Influence of psychiatric comorbidity on recovery and recurrence in generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, and panic disorder: a 12-year prospective study. Am J Psychiatry 2005;162:1179-87. 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.6.1179 pmid:15930067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scholten WD, Batelaan NM, van Balkom AJLM, Wjh Penninx B, Smit JH, van Oppen P. Recurrence of anxiety disorders and its predictors. J Affect Disord 2013;147:180-5. 10.1016/j.jad.2012.10.031 pmid:23218248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scholten WD, Batelaan NM, Penninx BWJH, et al. Diagnostic instability of recurrence and the impact on recurrence rates in depressive and anxiety disorders. J Affect Disord 2016;195:185-90. 10.1016/j.jad.2016.02.025 pmid:26896812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kessler RC, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Wittchen H-U. Twelve-month and lifetime prevalence and lifetime morbid risk of anxiety and mood disorders in the United States. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 2012;21:169-84. 10.1002/mpr.1359 pmid:22865617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hendriks SM, Spijker J, Licht CMM, et al. Disability in anxiety disorders. J Affect Disord 2014;166:227-33. 10.1016/j.jad.2014.05.006 pmid:25012435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Melse JM, Essink-Bot M-L, Kramers PG, Hoeymans N. Dutch Burden of Disease Group. A national burden of disease calculation: Dutch disability-adjusted life-years. Am J Public Health 2000;90:1241-7. 10.2105/AJPH.90.8.1241 pmid:10937004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jorm AF, Griffiths KM, Christensen H, Medway J. Research priorities in mental health, part 1: an evaluation of the current research effort against the criteria of disease burden and health system costs. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2002;36:322-6. 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2002.01023.x pmid:12060180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saarni SI, Härkänen T, Sintonen H, et al. The impact of 29 chronic conditions on health-related quality of life: a general population survey in Finland using 15D and EQ-5D. Qual Life Res 2006;15:1403-14. 10.1007/s11136-006-0020-1 pmid:16960751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saarni SI, Suvisaari J, Sintonen H, et al. Impact of psychiatric disorders on health-related quality of life: general population survey. Br J Psychiatry 2007;190:326-32. 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.025106 pmid:17401039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Batelaan NM, Smit F, de Graaf R, van Balkom AJ, Vollebergh WA, Beekman AT. Identifying target groups for the prevention of anxiety disorders in the general population. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2010;122:56-65. 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01488.x pmid:19824988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baldwin DS, Anderson IM, Nutt DJ, et al. Evidence-based pharmacological treatment of anxiety disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder: a revision of the 2005 guidelines from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol 2014;28:403-39. 10.1177/0269881114525674 pmid:24713617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alonso J, Angermeyer MC, Bernert S, et al. ESEMeD/MHEDEA 2000 Investigators, European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD) Project. Use of mental health services in Europe: results from the European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD) project. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl 2004;109:47-54. 10.1111/j.1600-0047.2004.00325.x pmid:15128387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Roest AM, de Jonge P, Williams CD, de Vries YA, Schoevers RA, Turner EH. Reporting bias in clinical trials investigating the efficacy of second-generation antidepressants in the treatment of anxiety disorders: a report of 2 meta-analyses. JAMA Psychiatry 2015;72:500-10. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.15 pmid:25806940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taylor S, Abramowitz JS, McKay D. Non-adherence and non-response in the treatment of anxiety disorders. J Anxiety Disord 2012;26:583-9. 10.1016/j.janxdis.2012.02.010 pmid:22440391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bandelow B, Zohar J, Hollander E, et al. WFSBP Task Force on Treatment Guidelines for Anxiety, Obsessive-Compulsive and Post-Traumatic Stress Disoders. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of anxiety, obsessive-compulsive and post-traumatic stress disorders - first revision. World J Biol Psychiatry 2008;9:248-312. 10.1080/15622970802465807 pmid:18949648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mojtabai R, Olfson M. National trends in long-term use of antidepressant medications: results from the U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Clin Psychiatry 2014;75:169-77. 10.4088/JCP.13m08443 pmid:24345349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johnson CF, Macdonald HJ, Atkinson P, Buchanan AI, Downes N, Dougall N. Reviewing long-term antidepressants can reduce drug burden: a prospective observational cohort study. Br J Gen Pract 2012;62:e773-9. 10.3399/bjgp12X658304 pmid:23211181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Petty DR, House A, Knapp P, Raynor T, Zermansky A. Prevalence, duration and indications for prescribing of antidepressants in primary care. Age Ageing 2006;35:523-6. 10.1093/ageing/afl023 pmid:16690637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Donovan MR, Glue P, Kolluri S, Emir B. Comparative efficacy of antidepressants in preventing relapse in anxiety disorders - a meta-analysis. J Affect Disord 2010;123:9-16. 10.1016/j.jad.2009.06.021 pmid:19616306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Allgulander C, Jørgensen T, Wade A, et al. Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) among patients with Generalised Anxiety Disorder: evaluation conducted alongside an escitalopram relapse prevention trial. Curr Med Res Opin 2007;23:2543-9. 10.1185/030079907X226087 pmid:17825130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rickels K, Etemad B, Khalid-Khan S, Lohoff FW, Rynn MA, Gallop RJ. Time to relapse after 6 and 12 months’ treatment of generalized anxiety disorder with venlafaxine extended release. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2010;67:1274-81. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.170 pmid:21135327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mavissakalian M, Perel JM. Clinical experiments in maintenance and discontinuation of imipramine therapy in panic disorder with agoraphobia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1992;49:318-23. 10.1001/archpsyc.49.4.318 pmid:1558466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Choy Y, Peselow ED, Case BG, et al. Three-year medication prophylaxis in panic disorder: to continue or discontinue? A naturalistic study. Compr Psychiatry 2007;48:419-25. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2007.04.003 pmid:17707249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mavissakalian MR, Perel JM. 2nd year maintenance and discontinuation of imipramine in panic disorder with agoraphobia. Ann Clin Psychiatry 2001;13:63-7. 10.3109/10401230109148949 pmid:11534926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mavissakalian MR, Perel JM. Duration of imipramine therapy and relapse in panic disorder with agoraphobia. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2002;22:294-9. 10.1097/00004714-200206000-00010 pmid:12006900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol 2009;62:1006-12. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005 pmid:19631508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parmar MK, Torri V, Stewart L. Extracting summary statistics to perform meta-analyses of the published literature for survival endpoints. Stat Med 1998;17:2815-34. pmid:9921604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tierney JF, Stewart LA, Ghersi D, Burdett S, Sydes MR. Practical methods for incorporating summary time-to-event data into meta-analysis. Trials 2007;8:16 10.1186/1745-6215-8-16 pmid:17555582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Higgins J, Altman DG, Sterne JA. Assessing risk of bias in included studies. In: Green S, ed. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions Version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011).Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: A simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics 2000;56:455-63. 10.1111/j.0006-341X.2000.00455.x pmid:10877304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sterne JA, Egger M, Moher D. Addressing reporting biases. In: Green S, ed. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions Version 5.1.0 (updated March 2011).Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sterne JA, Sutton AJ, Ioannidis JP, et al. Recommendations for examining and interpreting funnel plot asymmetry in meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2011;343:d4002 10.1136/bmj.d4002 pmid:21784880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 1986;7:177-88. 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2 pmid:3802833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.IntHout J, Ioannidis JP, Borm GF. The Hartung-Knapp-Sidik-Jonkman method for random effects meta-analysis is straightforward and considerably outperforms the standard DerSimonian-Laird method. BMC Med Res Methodol 2014;14:25 10.1186/1471-2288-14-25 pmid:24548571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cornell JE, Mulrow CD, Localio R, et al. Random-effects meta-analysis of inconsistent effects: a time for change. Ann Intern Med 2014;160:267-70. 10.7326/M13-2886 pmid:24727843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hartung J, Knapp G. A refined method for the meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials with binary outcome. Stat Med 2001;20:3875-89. 10.1002/sim.1009 pmid:11782040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JP, et al, eds. Introduction to meta-analysis.Wiley, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Davidson JR, Connor KM, Hertzberg MA, Weisler RH, Wilson WH, Payne VM. Maintenance therapy with fluoxetine in posttraumatic stress disorder: a placebo-controlled discontinuation study. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2005;25:166-9. 10.1097/01.jcp.0000155817.21467.6c pmid:15738748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Michelson D, Pollack M, Lydiard RB, Tamura R, Tepner R, Tollefson G. The Fluoxetine Panic Disorder Study Group. Continuing treatment of panic disorder after acute response: randomised, placebo-controlled trial with fluoxetine. Br J Psychiatry 1999;174:213-8. 10.1192/bjp.174.3.213 pmid:10448445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Furukawa TA, Guyatt GH, Griffith LE. Can we individualize the ‘number needed to treat’? An empirical study of summary effect measures in meta-analyses. Int J Epidemiol 2002;31:72-6. 10.1093/ije/31.1.72 pmid:11914297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003;327:557-60. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557 pmid:12958120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Review Manager (RevMan). Nordic Cochrane Centre, 2014.

- 46.Borenstein M, Hedges L, Higgins J, et al. Comprehensive Meta Analysis.Biostat, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hackett D, White C, Salinas E. Relapse prevention in patients with generalised anxiety disorder (GAD) by treatment with venlafaxine ER [abstract]. 1st International Forum on Mood and Anxiety Disorders, Monte Carlo, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Davidson JRT, Wittchen H-U, Llorca P-M, et al. Duloxetine treatment for relapse prevention in adults with generalized anxiety disorder: a double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2008;18:673-81. 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2008.05.002. pmid:18559291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang CJ, Davidson JRT, Connor KM, et al. Pilot study to evaluate excitalopram in obsessive-compulsive disorder. 2013. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/results/NCT00215137.

- 50.GlaxoSmithKline. Long-term treatment with paroxetine of outpatients with obsessive-compulsive disorder: an extension of the companion study. 2008. http://www.gsk-clinicalstudyregister.com/study/29060/127#rs.

- 51.GlaxoSmithKline. A double-blind, placebo-controlled, continuation of study 29060/120 to assess the long term safety and efficacy of paroxetine in the treatment of panic disorder and its role in the prevention of relapse/recurrence. 2008. http://www.gsk-clinicalstudyregister.com/study/29060/222#rs.

- 52.GlaxoSmithKline. An extension trial comparing paroxetine and placebo in the long term treatment of generalized social phobia. 2008. http://www.gsk-clinicalstudyregister.com/study/29060/470#rs.

- 53.GlaxoSmithKline. A study of the maintained efficacy and safety of paroxetine versus placebo in the long-term treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. 2008. http://www.gsk-clinicalstudyregister.com/study/29060/650#rs.

- 54.Stocchi F, Nordera G, Jokinen RH, et al. Paroxetine Generalized Anxiety Disorder Study Team. Efficacy and tolerability of paroxetine for the long-term treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2003;64:250-8. 10.4088/JCP.v64n0305 pmid:12716265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Allgulander C, Florea I, Huusom AKT. Prevention of relapse in generalized anxiety disorder by escitalopram treatment. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2006;9:495-505. 10.1017/S1461145705005973 pmid:16316482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Baldwin DS, Loft H, Florea I. Lu AA21004, a multimodal psychotropic agent, in the prevention of relapse in adult patients with generalized anxiety disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2012;27:197-207. 10.1097/YIC.0b013e3283530ad7 pmid:22475889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stein DJ, Ahokas A, Albarran C, Olivier V, Allgulander C. Agomelatine prevents relapse in generalized anxiety disorder: a 6-month randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled discontinuation study. J Clin Psychiatry 2012;73:1002-8. 10.4088/JCP.11m07493 pmid:22901350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fineberg NA, Tonnoir B, Lemming O, Stein DJ. Escitalopram prevents relapse of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2007;17:430-9. 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2006.11.005 pmid:17240120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Geller DA, Biederman J, Stewart SE, et al. Impact of comorbidity on treatment response to paroxetine in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder: is the use of exclusion criteria empirically supported in randomized clinical trials?J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 2003;13(Suppl 1):S19-29. 10.1089/104454603322126313 pmid:12880497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hollander E, Allen A, Steiner M, Wheadon DE, Oakes R, Burnham DB. Paroxetine OCD Study Group. Acute and long-term treatment and prevention of relapse of obsessive-compulsive disorder with paroxetine. J Clin Psychiatry 2003;64:1113-21. 10.4088/JCP.v64n0919 pmid:14628989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Koran LM, Hackett E, Rubin A, Wolkow R, Robinson D. Efficacy of sertraline in the long-term treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2002;159:88-95. 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.1.88 pmid:11772695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Koran LM, Gamel NN, Choung HW, Smith EH, Aboujaoude EN. Mirtazapine for obsessive-compulsive disorder: an open trial followed by double-blind discontinuation. J Clin Psychiatry 2005;66:515-20. 10.4088/JCP.v66n0415 pmid:15816795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Romano S, Goodman W, Tamura R, Gonzales J. Long-term treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder after an acute response: a comparison of fluoxetine versus placebo. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2001;21:46-52. 10.1097/00004714-200102000-00009 pmid:11199947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mavissakalian MR, Perel JM. Long-term maintenance and discontinuation of imipramine therapy in panic disorder with agoraphobia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1999;56:821-7. 10.1001/archpsyc.56.9.821 pmid:12884888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ferguson JM, Khan A, Mangano R, Entsuah R, Tzanis E. Relapse prevention of panic disorder in adult outpatient responders to treatment with venlafaxine extended release. J Clin Psychiatry 2007;68:58-68. 10.4088/JCP.v68n0108 pmid:17284131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rapaport MH, Wolkow R, Rubin A, Hackett E, Pollack M, Ota KY. Sertraline treatment of panic disorder: results of a long-term study. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2001;104:289-98. 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2001.00263.x pmid:11722304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kamijima K, Kuboki T, Kumano H, et al. A placebo-controlled, randomized withdrawal study of sertraline for panic disorder in Japan. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2005;20:265-73. 10.1097/01.yic.0000171518.25963.63 pmid:16096517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Davidson J, Pearlstein T, Londborg P, et al. Efficacy of sertraline in preventing relapse of posttraumatic stress disorder: results of a 28-week double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158:1974-81. 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.12.1974 pmid:11729012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Martenyi F, Brown EB, Zhang H, Koke SC, Prakash A. Fluoxetine v. placebo in prevention of relapse in post-traumatic stress disorder. Br J Psychiatry 2002;181:315-20. 10.1192/bjp.181.4.315 pmid:12356658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Montgomery SA, Nil R, Dürr-Pal N, Loft H, Boulenger JP. A 24-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of escitalopram for the prevention of generalized social anxiety disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2005;66:1270-8. 10.4088/JCP.v66n1009 pmid:16259540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Stein MB, Chartier MJ, Hazen AL, et al. Paroxetine in the treatment of generalized social phobia: open-label treatment and double-blind placebo-controlled discontinuation. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1996;16:218-22. 10.1097/00004714-199606000-00005 pmid:8784653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Stein DJ, Versiani M, Hair T, Kumar R. Efficacy of paroxetine for relapse prevention in social anxiety disorder: a 24-week study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2002;59:1111-8. 10.1001/archpsyc.59.12.1111 pmid:12470127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Walker JR, Van Ameringen MA, Swinson R, et al. Prevention of relapse in generalized social phobia: results of a 24-week study in responders to 20 weeks of sertraline treatment. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2000;20:636-44. 10.1097/00004714-200012000-00009 pmid:11106135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fava M. Prospective studies of adverse events related to antidepressant discontinuation. J Clin Psychiatry 2006;67(Suppl 4):14-21.pmid:16683858. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Karsten J, Hartman CA, Smit JH, et al. Psychiatric history and subthreshold symptoms as predictors of the occurrence of depressive or anxiety disorder within 2 years. Br J Psychiatry 2011;198:206-12. 10.1192/bjp.bp.110.080572 pmid:21357879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gardarsdottir H, Egberts TC, Stolker JJ, Heerdink ER. Duration of antidepressant drug treatment and its influence on risk of relapse/recurrence: immortal and neglected time bias. Am J Epidemiol 2009;170:280-5. 10.1093/aje/kwp142 pmid:19498074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lundh A, Sismondo S, Lexchin J, Busuioc OA, Bero L. Industry sponsorship and research outcome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;12:MR000033.pmid:23235689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.François C, Montgomery SA, Despiegel N, Aballéa S, Roïz J, Auquier P. Analysis of health-related quality of life and costs based on a randomised clinical trial of escitalopram for relapse prevention in patients with generalised social anxiety disorder. Int J Clin Pract 2008;62:1693-702. 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2008.01879.x pmid:18759783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Generalised anxiety disorder and panic disorder (with or without agoraphobia) in adults: management in primary, secondary and community care.NICE, 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gardarsdottir H, van Geffen ECG, Stolker JJ, Egberts TC, Heerdink ER. Does the length of the first antidepressant treatment episode influence risk and time to a second episode?J Clin Psychopharmacol 2009;29:69-72. 10.1097/JCP.0b013e31819302b1 pmid:19142111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bosman RC, Huijbregts KM, Verhaak PF, et al. Long-term antidepressant use: a qualitative study on perspectives of patients and GPs in primary care. Br J Gen Pract 2016;66:e708-19. 10.3399/bjgp16X686641 pmid:27528709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wouters H, Van Dijk L, Van Geffen ECG, Gardarsdottir H, Stiggelbout AM, Bouvy ML. Primary-care patients’ trade-off preferences with regard to antidepressants. Psychol Med 2014;44:2301-8. 10.1017/S0033291713003103 pmid:24398071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Verbeek-Heida PM, Mathot EF. Better safe than sorry--why patients prefer to stop using selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressants but are afraid to do so: results of a qualitative study. Chronic Illn 2006;2:133-42.pmid:17175656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 1-5