Abstract

Objective:

Evaluate the incidence and predictors of HIV acquisition from outside partners in serodiscordant couples.

Methods:

Demographic, behavioral, and clinical exposures were measured quarterly in a cohort of serodiscordant cohabiting couples in Zambia from 1995 to 2012 (n = 3049). Genetic analysis classified incident infections as those acquired from the study partner (linked) or acquired from an outside partner (unlinked). Factors associated with time to unlinked HIV infection were evaluated using multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression stratified by sex.

Results:

There were 100 unlinked infections in couples followed for a median of 806 days. Forty-five infections occurred in women [1.85/100 couple-years; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.35 to 2.47]. Risk of female unlinked infection (vs. nonseroconverting females) was associated with reporting being drunk weekly/daily vs. moderate/nondrinkers at baseline [adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) = 5.44; 95% CI: 1.03 to 28.73], genital ulcers (aHR = 6.09; 95% CI: 2.72 to 13.64), or genital inflammation (aHR = 11.92; 95% CI: 5.60 to 25.37) during follow-up adjusting for age, years cohabiting, income, contraceptive use, previous pregnancies, history of sexually transmitted infections, and condomless sex with study partner. Fifty-five infections occurred in men (1.82/100 couple-years; 95% CI: 1.37 to 2.37). Risk of male unlinked infection was associated with genital inflammation (aHR = 8.52; 95% CI: 3.82 to 19.03) or genital ulceration (aHR = 2.31; 95% CI: 2.05 to 8.89), reporting ≥1 outside sexual partner (aHR = 3.86; 95% CI: 0.98 to 15.17) during follow-up, and reporting being drunk weekly/daily vs. moderate/nondrinkers at baseline (aHR = 3.84; 95% CI: 1.28 to 11.55), controlling for age, income, circumcision status, and history of sexually transmitted infection.

Conclusions:

Predictors of unlinked infection in serodiscordant relationships were alcohol use, genital inflammation, and ulceration. Causes of genital inflammation and ulceration should be screened for and treated in HIV-negative individuals. Counseling on risk of alcohol use and sex with outside partners should be discussed with couples where 1 or both are HIV-negative, including in counseling on use of pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent HIV acquisition in the HIV-negative partner (when feasible and affordable).

Key Words: serodiscordant, unlinked infection, couples, Zambia, HIV transmission, HIV acquisition

BACKGROUND

HIV incidence in studies of HIV-serodiscordant couples ranges from 2.0 to 11.8 per 100 person-years depending on whether they know their joint serostatus, the type of study, the study location, and the accompanying services made available to the couples.1–3 Among couples with HIV infections acquired from a partner outside the primary serodiscordant partnership, as indicated by viral sequencing, incidence rates range from 0.51 per 100 person-years among women reporting no outside sex partners to 3.46 per 100 person-years among women reporting outside sex partners.4 Although uptake of antiretroviral treatment (ART) among HIV-serodiscordant couples has been recommended where feasible, it does not remove the need for behavioral interventions to reduce HIV acquisition from outside partners.4–6 Several African countries are adopting couples-based HIV counseling and testing as an HIV prevention and care intervention, thus more couples are becoming aware of each other's HIV status, and many find out that they are HIV-serodiscordant.7 Despite this increased knowledge of HIV-serodiscordance among couples, there has been less focus on effective messages and interventions to prevent HIV acquisition from outside partners. Appropriate and effective interventions for HIV prevention in serodiscordant couples depend on accurate assessments of the sexual risk behaviors among the HIV-positive and HIV-negative partners and understanding their own sexual behaviors with other men and women.

Improved evidence around factors that increase the risk of HIV infection in cohabiting relationships is needed to develop and improve evidence-based interventions. Specifically, more research is needed on factors with a disputed and unclear influence on HIV acquisition and transmission at the individual and couple level, including hormonal contraception,8–10,30 concurrent sexual partnerships,11–16 alcohol,16–19,43 and age discordancy.20–22 Studies among African serodiscordant couples have demonstrated that HIV acquisition is associated with younger age, alcohol use, genital inflammation and discharge, and non-ART use by HIV-positive partner.19,22,23 However, there is limited research on factors associated with acquiring HIV from an outside partner or an “unlinked infection.” Learning that one is in an HIV-serodiscordant relationship may cause the HIV-negative partner to have sex with outside partners, often of unknown HIV serostatus, who might be perceived to pose lower risk of HIV infection than the primary HIV-positive partner.1,3,4 Greater understanding of HIV-negative partners' behaviors with outside or concurrent sex partners, and these behaviors' associations with HIV acquisition, will inform HIV risk-reduction messages for uninfected partners.

A recent study of serodiscordant couples found that the proportion of subjects reporting sex with an outside partner increased from 3.1% to 13.9% (P < 0.001) after learning of their serodiscordant results.3 Condomless sex was more common with outside partners than with the primary HIV-positive partners, and a small portion (<5%) reported concurrent sexual partnership with their infected partner and an outside partner within the same month.3 Another study showed that sex with infected partners decreases during follow-up and increases with outside partners over time, possibly reflecting relationship dissolution.24 A recent Kenyan study found 24% of serodiscordant couples separated during 2 years of follow-up.24 However, in our Zambian cohort, only 3.7% separated shortly after CVCT25 and the annual rate of separation thereafter was <5%. This study examined the incidence of unlinked infections, and risk factors associated with unlinked seroconversion among men and women in cohabiting heterosexual couples in a long-running cohort in urban Zambia.

METHODS

The Heterosexual Transmission of HIV Study, conducted by the Rwanda Zambia HIV Research Group, was an open prospective cohort which enrolled 3049 adult heterosexual serodiscordant couples recruited from couples' counseling and testing sites in Lusaka, Zambia. Data collection began in January 1995 and ended in December 2012. Couples were enrolled after couples' HIV counseling and testing services and their HIV-serodiscordant diagnosis.

Ethics

Couples provided joint written informed consent to participate in this study. This study was approved by the Office for Human Research Protections-registered Institutional Review Boards at Emory and the University of Zambia.

Study Participants

Married or cohabiting couples in Lusaka, Zambia, attended voluntary couples' HIV counseling and testing (CVCT) services either spontaneously or after receiving an invitation from a community promoter.26,27,28 CVCT services include group counseling, rapid HIV testing, and post-test couples' counseling.27,29 HIV-serodiscordant couples were invited to enroll in a longitudinal open cohort follow-up study between 1995 and 2012. Routine outpatient care and family planning were provided at the research clinic. Beginning in 2007 when ART became available in government health clinics, HIV-positive individuals were referred to the facility nearest to their residence for ART initiation, which was prescribed based on national guidelines in force at the time.

Study Eligibility

The cohort's inclusion criteria were (1) confirmed HIV-1 serodiscordance after attending CVCT services, (2) the participants had been married or cohabitating for at least 3 months, and (3) the participants planned on staying in the Lusaka region for the next year. Couples were ineligible if either partner was on ART. Couples were censored if either partner died, the couple separated, the HIV-positive partner initiated ART, or either partner was lost to follow-up. Couples were considered lost to follow-up if they did not return for 2 consecutive quarterly study visits.

Data Collection

Study questionnaires were administered by study nurses or counselors at baseline and every subsequent visit (monthly or quarterly). Study participants completed behavioral and medical history questionnaires in the local language and underwent a full physical examination, including pelvic/genital exams, HIV counseling and testing, and screening for sexually transmitted infections (STIs) at baseline. Follow-up visits included physical exam, vaginal swab wet preparation, repeat rapid plasma reagin (RPR) screening, repeat HIV testing of the HIV-negative partner, and completion of study questionnaires that collected demographic, psychosocial, behavioral, medical history, and health-services data. The data were collected by interviewer-administered questionnaires in face-to-face interviews. Couples were given coital diaries to keep and record sexual exposures with and without condoms. Coital diaries were used to validate responses about sex frequency and condom use and nonuse.

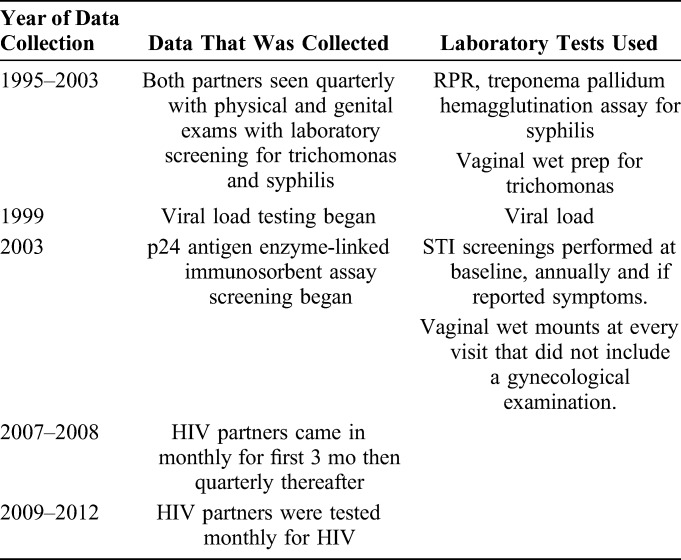

Data collection varied over the 18 years of follow-up. In 1999, the study began plasma banking for viral load testing, and in 2003 p24 antigen enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay screening began. From 1995 to 2003, both partners were seen quarterly, had routine physical and genital exams, and received laboratory screening for HIV (rapid antibody test) trichomonas (vaginal wet prep) and syphilis (RPR: positive RPR was batched for later treponema pallidum hemagglutination assay, confirming a low rate of false positive RPR).23,30 In 2003, the study procedures were streamlined and physical exams and STI screenings were performed at baseline, annually, and when participants reported symptoms. Vaginal wet mounts were prepared using self-administered swabs at every visit that did not include a gynecologic examination (validated at the time of use in the study). From 2002 to 2011, fertility intentions were recorded. From 2007 to 2008, HIV partners came in monthly for the first 3 months, and quarterly thereafter at which time a sexual exposure risk assessment including self-reported unprotected sex or incident STI (in men and women); or sperm (a biomarker of condomless sex in women) or trichomonas on a wet mount and incident pregnancy (for women) was completed. HIV-negative partners in couples with at least 1 exposure received monthly HIV testing until the next quarterly visit, when the risk assessment was repeated. From 2009 to 2012, HIV-negative partners were tested monthly for HIV. We did not collect data on HIV status or sex of outside partner and assumed that outside partners were heterosexual (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Data Collection and Laboratory Test by Year of Collection

Genital Ulceration and Inflammation

Measures of chronic/recurrent or acute genital or perianal ulcers were assessed through self-report, physical examination (including erosion or friability of the cervix or vagina in women), chart review of outpatient treatment visits, and laboratory testing. A time-varying composite genital ulcer variable was developed and considered positive if the patient reported ulcers, had ulcers noted on physical exam, had been treated for ulcers, or had a newly positive RPR.23

Genital inflammation measures included in the time-varying composite included physical examination findings including cervical, vaginal or external genital inflammation (redness, swelling, exudate, irritation, or tenderness), or inguinal adenopathy (80% of which was bilateral adenopathy); candida or bacterial vaginosis on vaginal wet mount including KOH prep, sniff test; reported vaginal discharge, odor, or discomfort; and self-report or treatment for gonorrhea/chlamydia (diagnosed syndromically based on endocervical pus in women or urethral discharge in men) or trichomonas (vaginal wet mount) in the past 3 months.23,31,32

HIV Testing

To define the time of incident infection, when available, plasma from the last antibody-negative sample was tested with RNA polymerase chain reaction (Roche). The date of HIV infection was defined based on available laboratory results as the minimum of the midpoint between the last negative and first positive antibody date; 3 weeks before the first p24 antigen positive test date; or 2 weeks before the first positive HIV viral RNA/rapid test negative test date.

The molecular epidemiology of the HIV incident transmission events that occurred during study follow-up was reported by examining the genetic characterization of HIV viral strains. Comparison of polymerase chain reaction–amplified HIV nucleotide sequences in peripheral blood mononuclear cell DNA samples collected from both partners at the time of seroconversion classified incident infections as linked or unlinked to the study partner.

To establish linkage for HIV-1 viral strains in transmission pairs, amplified viral sequences encoding the extracellular domain of gp41 were first aligned and then subjected to pairwise sequence comparisons. Uncorrected nucleotide sequence distances were then calculated for each transmission pair and compared with the mean sequence distance calculated for a reference set of gp41 sequences from 81 unrelated Zambian HIV-1–infected individuals from the same Zambian cohort of serodiscordant couples.33 The latter value (9.3%) minus 2 standard deviations (5.5%) was arbitrarily assigned as the maximum diversity cutoff value for epidemiologically linked sequence pairs. Transmission pairs were tentatively classified as having epidemiologically linked viruses when their pairwise sequence distances fell below this limit and unlinked viruses when their pairwise distances exceeded this limit. Transmission linkage was confirmed by phylogenetic analysis using a neighbor-joining tree of the same gp41 sequences.

Analyses

HIV incidence rates were calculated as the number of unlinked incident infections per 100 couple-years (CYs) of follow-up, excluding those couples with a linked infection in the numerator but not the denominator, as they were at the risk of HIV acquisition from a study partner throughout the exposure period. We used all follow-up intervals rather than follow-up intervals with reported outside exposure to report a cumulative measure of exposure to outside partners. CYs of follow-up were calculated from enrollment until either an outcome of interest occurred or the couple was censored. Rates were also calculated by calendar time, duration of follow-up time and by sex of seroconverted. Baseline exposures were stratified by sex of the HIV-negative partner. Baseline and time-varying exposures were described using counts and percentages (for categorical variables) or means and standard deviations (for continuous variables). For descriptive analyses, we tested all differences using χ2 tests for bivariate variables and t tests for continuous variables. We included other variables with P < 0.10 because they were a priori exposures of interest (eg, alcohol). We conducted sensitivity analyses around heavy alcohol use and grouped weekly and daily drinkers in the final model and moderate and nondrinkers in the reference group to provide enough power to evaluate the effect of heavy alcohol use. We then included variables with P < 0.10. Bivariate hazard ratios (HRs), P values, and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) between covariates and unlinked infections are based on bivariate Cox proportional hazards regression.44

Four multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression models were constructed to evaluate predictors of time to acquisition of genetically unlinked HIV infection among (1) female and (2) male partners, compared with no acquisition of infection. We included all variables that were significant in bivariate analyses (P < 0.05) and were also a priori risk factors for HIV acquisition.2,3,10,11,18,20,22 We included the following interaction terms in our analyses: age and literacy, HIV status and condom use, none of which were significant (P < 0.05) in the models. The proportional hazards assumption was confirmed for time-independent covariates. Because we identified effect-measure modification for sex of seroconvertor, stratified analysis was used for all subsequent models. Multicollinearity was assessed by analyzing the variance inflation factor and tolerance to check the degree of collinearity between variables. For collinear variables such as number of children and number of previous pregnancies, we selected 1 variable (eg, number of previous pregnancies in this example), which was more strongly associated with the outcome of the model. All analyses were conducted with SAS v9.4 (Cary, NC).

RESULTS

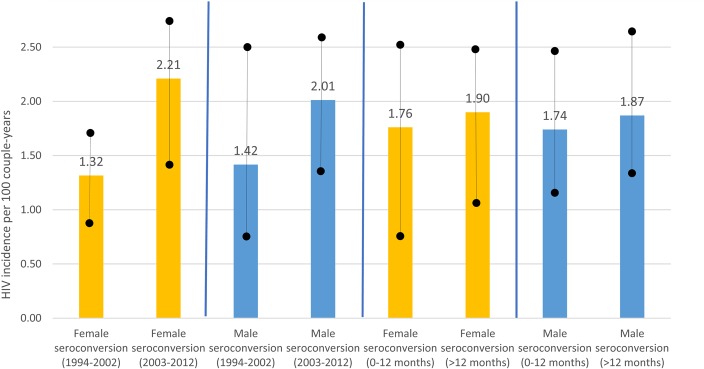

The primary analyses comprised a total of 3049 couples. In these couples, there were 478 seroconversions, 100 of which were determined to be acquired from an outside partner (ie, their virus was not genetically linked to the partner's virus: 45 women, 55 men). The remaining 354 individuals had a linked seroconversion (ie, their virus was genetically linked to the study partner's virus), or were unknown linkage (n = 24) and were excluded from the analyses here. There were no seroconversions among the remaining 2571 couples. Couples with an unlinked infection were followed for a median of 806 days. The unlinked HIV incidence rate among women was 1.32 per 100 CY from 1995 to 2002, and it rose to 2.21 per 100 CY from 2003 to 2012 though this difference was not significant. Similarly, the male unlinked incidence was 1.42 per 100 CY from 1995 to 2002 with a nonsignificant increase to 2.01 per 100 CY from 2003 to 2012 (Fig. 1). The incidence rate was similar for patients followed for the first 12 months was similar to the rate for participants followed for more than 12 months and beyond for men and women (P > 0.05), confirming no cohort effect.

FIGURE 1.

Genetically unlinked HIV incidence rates (and 95% CIs) among serodiscordant couples in Zambia stratified by year of enrollment, follow-up time, and sex (1995–2012).

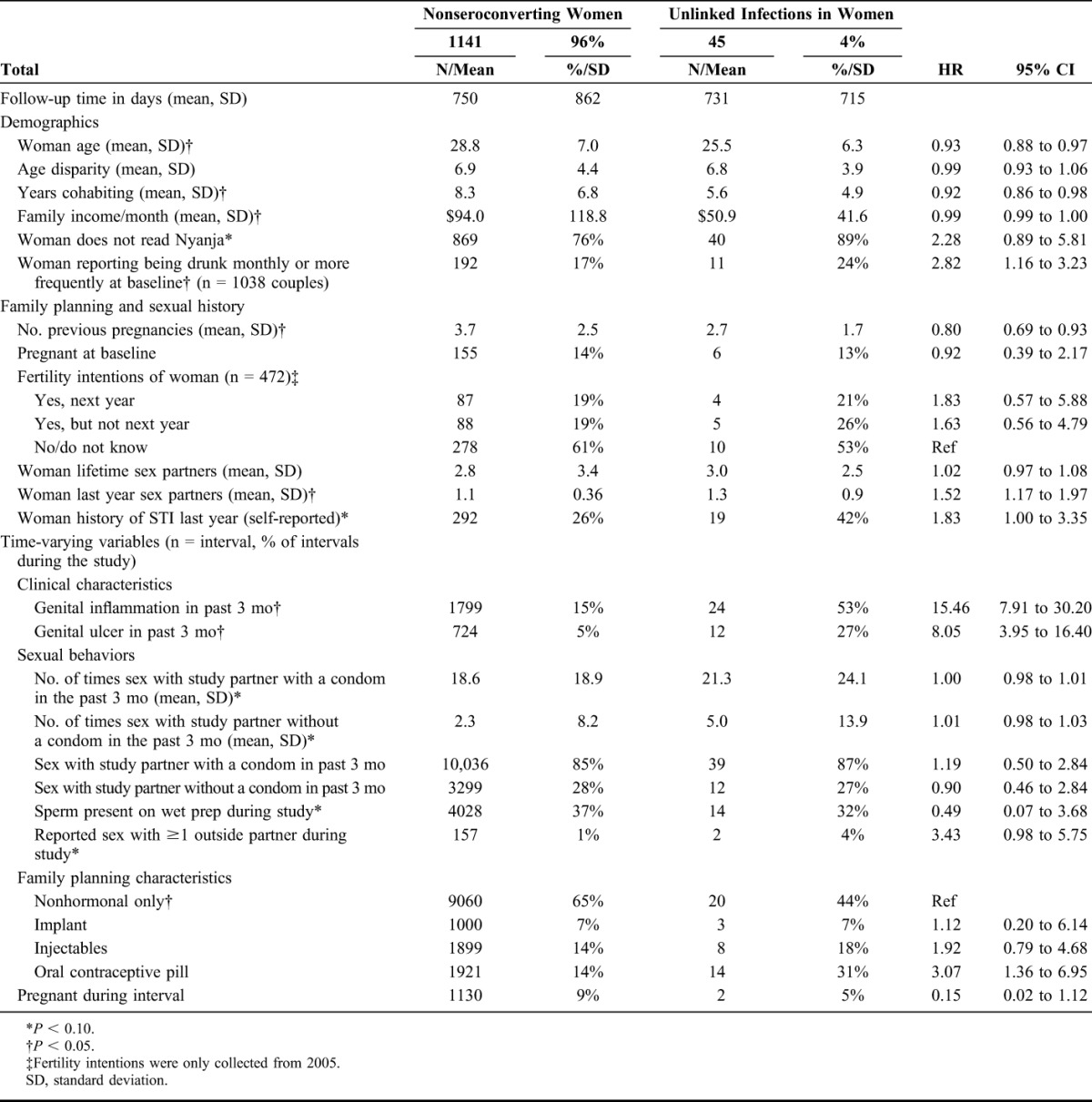

Unlinked Infections in Women

Forty-five genetically unlinked seroconversions were observed in women over 2432.79 CY of M+F− couple follow-up, for a seroconversion rate of 1.85 seroconversions/100 CY (95% CI: 1.35 to 2.47). Unless specified, the following differences are statistically significant at P < 0.05. HIV-negative women who did not seroconvert were older (28.8 vs. 25.5 compared with women who acquired HIV from an outside partner) had lived with partners more years (mean of 8.3 vs. 5.6 years, respectively) and had more children (mean of 3.7 previous pregnancies vs. 2.7, respectively) than those who acquired an unlinked HIV infection. Monthly mean family income was lower in couples in which the woman had an unlinked seroconversion ($50.9 vs. $94.0/month, respectively). The proportion of women who read Nyanja (a measure of education) was lower among those with an unlinked infection compared with those who did not seroconvert (11% vs. 24%, P = 0.06). Women with an unlinked infection reported more heavy alcohol drinking (drunk weekly or daily/almost daily) at baseline (24% vs. 17%, P = 0.052). In 1% (n = 157) of intervals nonseroconvertors reported having an outside sex partner during the study compared with 4% (n = 2) of women who reported having an outside partner the interval before they acquired HIV from an outside partner (P = 0.054). Women with an unlinked infection were more likely to report a history of STI in the year before enrollment (42% vs. 26%). In addition, women with genital inflammation in the interval before seroconversion had increased risk of having an unlinked infection compared with nonseroconverting women (HR = 15.46, 95% CI: 7.91 to 30.20). Similarly, women with genital ulceration in the interval before seroconversion had increased risk of unlinked infection compared with nonseroconverting women (HR = 8.05, 95% CI: 3.95 to 16.40). Women who used oral contraceptive pills had an increased risk compared with nonseroconverting women (HR = 3.07, 95% CI: 1.36 to 6.95) (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Demographic and Behavioral Characteristics of HIV-Negative Women in Serodiscordant Couples by Seroconversion Outcome (N = 1186 Male HIV-Positive/Female HIV-Negative Couples)

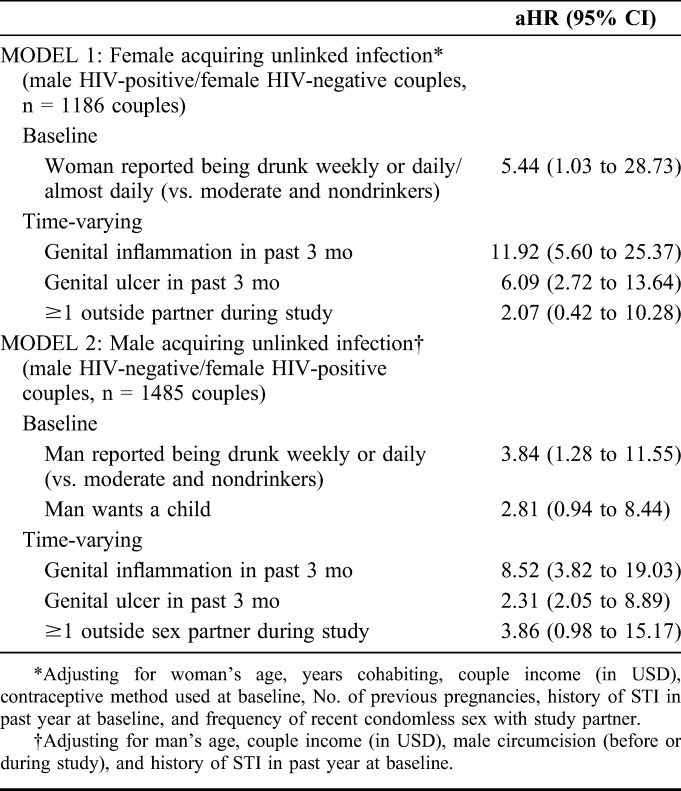

Controlling for woman's age, years cohabiting, couple income, contraceptive method use at baseline, number of previous pregnancies, self-reported STI in the year before baseline, and condomless sex with study partner, women's risk of acquiring HIV from an outside partner, when compared with nonseroconvertors, was associated with the woman reporting being drunk weekly or daily/almost daily in the past year at baseline (vs. moderate/nondrinkers) [adjusted HR (aHR) = 5.44; 95% CI: 1.03 to 28.73), time-varying genital ulcers (aHR = 6.09; 95% CI: 2.72 to 13.64), and genital inflammation (aHR = 11.92; 95% CI: 5.60 to 25.37). However, self-reporting ≥1 outside partner and hormonal contraceptive use were not independently associated with incident unlinked infection among women (Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Multivariable Cox Proportional Hazards Regression of Predictors of Time to Female Acquiring Unlinked Infection (Model 1) and Men Acquiring Unlinked Infection (Model 2) Compared With Nonseroconverting Couples

Unlinked Infections in Men

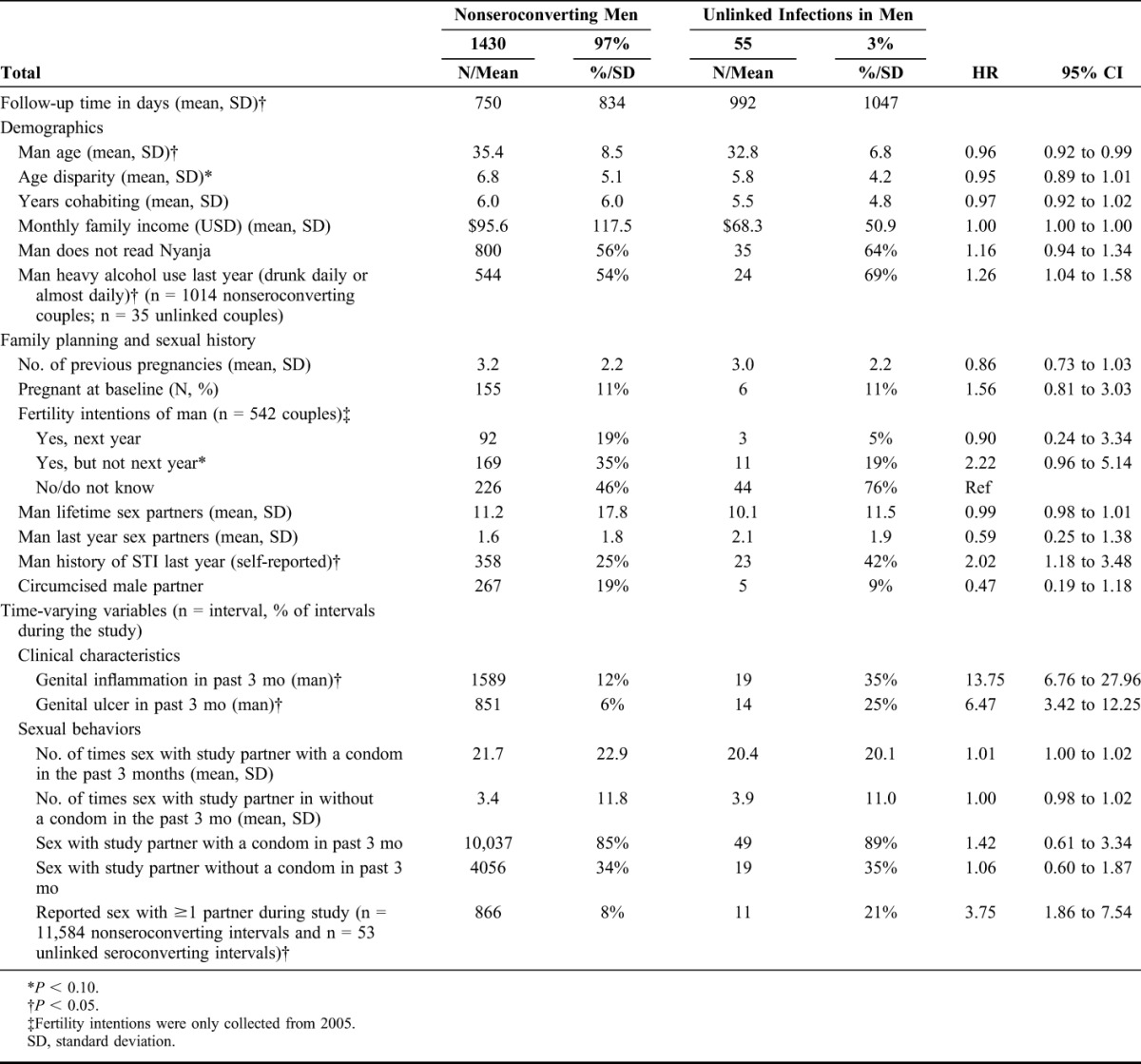

Fifty-five genetically unlinked incident seroconversions were observed in men over 3025.40 CY of follow-up, for a seroconversion rate of 1.82 seroconversions/100 CY (95% CI: 1.37 to 2.37). Unless specified, the following differences are statistically significant at P < 0.05. In descriptive analyses, men who had an unlinked seroconversion tended to be younger than men who did not seroconvert (mean age of 32.8 vs. 35.4) and had a lower monthly mean income ($68.3 vs. $95.6). Men with an unlinked infection were more likely to report heavy alcohol use in the past year at baseline (drunk daily or almost daily) (73% vs. 54%) and to self-report having a STI in the year before enrollment (42% vs. 25% of men who did not seroconvert). In addition, men who had genital inflammation in the interval before seroconversion had increased risk of an unlinked infection compared with nonseroconverting men (HR = 13.75, 95% CI: 6.76 to 27.96). Similarly, men with genital ulceration in the interval before seroconversion had increased risk of an unlinked infection compared with nonseroconverting men (HR = 6.47, 95% CI: 3.42 to 12.25). Approximately 21% of men with an unlinked infection reported having outside partner in the interval before they seroconverted, compared with 8% of intervals among nonseroconverting men (HR = 3.75, 95% CI: 1.86 to 7.54) (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Demographic and Behavioral Characteristics of HIV-Negative Men in Serodiscordant Couples by Seroconversion Outcome (N = 1485 Male HIV-Negative/Female HIV-Positive Couples)

Controlling for man's age, couple income, male circumcision (before or during the study), and history of STI in past year at baseline, the risk of unlinked incident HIV infection among men was associated with male alcohol use (reporting being drunk weekly or daily vs. moderate and nondrinkers in the year before enrollment) (aHR = 3.84, 95% CI: 1.28 to 11.55); and with genital ulcers (aHR = 2.31, 95% CI: 2.05 to 8.89), genital inflammation (aHR = 8.52, 95% CI: 3.82 to 19.03), and reporting ≥1 outside sex partner in the past 3 months (aHR = 3.86, 95% CI: 0.98 to 15.17) (Table 4).

DISCUSSION

This study contributes to the understanding of acquisition of HIV from concurrent sex partners among uninfected partners in cohabiting discordant couples in Southern Africa.3,34 We observed a genetically unlinked HIV incidence rate of 1.85/100 CY among women, and of 1.82/100 CY among men in this large 18-year prospective study. Overall, 21% of seroconversions were genetically unlinked during the 18-year study follow-up, with a higher proportion among men (24%) compared with women (18%). Our unlinked infection incidence rate is similar to other studies in the region,3 demonstrating the importance of outside partners as a risk for HIV acquisition in generalized HIV epidemics. Our study also demonstrated that factors associated with unlinked infection are similar to those reported for HIV acquisition more broadly: heavy alcohol use among both men and women,18,43 and genital discharge, ulceration and inflammation1,19,23 were important predictors of unlinked seroconversion. Studies of the newly infected partner in this cohort also confirm that genital inflammation is associated with transmission of multiple variants from outside partners.35,36 Similar to linked infections in this cohort,31,37 after controlling for potential confounders, we did not find that pregnancy (prevalent or incident) or contraceptive use were risk factors for unlinked seroconversion.

A greater proportion of new infections were acquired outside the marriage in men compared with women (24% vs. 18%, respectively). This may reflect an increased social or cultural acceptance of men having outside sexual partnerships, particularly once they know their main partner is HIV-positive. This may also reflect travel for work, which was not measured but is more likely among men compared with women.12–16 Self-reporting of outside partnerships was low and not associated with unlinked seroconversion among female partners, likely the result of underreporting. This highlights the challenges of self-reports collected by face-to-face interviews, especially among women, when aiming to identify individuals at risk from outside partnerships.

Approximately, 55%–60% of Zambian adults requiring treatment were on ART in 2013.38 Zambia has adopted the WHO-recommended approach to couples in whom 1 person is HIV-positive by offering treatment regardless of their CD4 cell count.39 However, the impact of ART as prevention in real world settings is mitigated by delays in initiation, poor retention, and adherence.40 Therefore, primary prevention strategies must begin with widespread implementation of CVCT and be followed by ART adherence counseling for the HIV-positive partner. Prevention of HIV exposure through concurrent partnerships in the HIV-negative partner should include emphasis on the fact that partners with an unknown serostatus still present a risk of acquiring HIV.

Recent research on how to deliver pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) to HIV-negative partners in discordant couples has focused on time-limited PrEP acting as a “bridge” for approximately 6 months until the HIV-positive partner is on ART and virally suppressed.45 However, in the context of a large proportion of HIV-negative partners having outside sex partners, PrEP use should continue because of continued high-risk exposure. When feasible and affordable, PrEP counseling should be adapted in this case for HIV-negative partners who may have other sex partners of unknown serostatus. In addition, health care providers should focus on counseling and services for alcohol abuse for HIV-positive and -negative individuals, as our study confirmed what other studies have shown about the risk of HIV acquisition among men and women who reported heavy alcohol use.41,43

The unlinked HIV incidence rate was higher from 2003 to 2012 compared with 1995–2002 among both men and women though this difference was not significant. By contrast, during this time frame linked seroincidence rates decreased.23 It is not clear what may have contributed to these findings, which reinforce the need to emphasize protective behaviors with concurrent and primary partner during counseling.29,32

Limitations

Although couples were demographically similar to the general population using DHS data,42 they were different from the general population and other serodiscordant couples in that they self-selected into both couples' counseling/testing and the cohort study which may reflect higher health motivation and a greater commitment to safer sexual practices.25 Use of self-reported information on sensitive exposure variables such as heavy alcohol use or outside sex partners may have low sensitivity, and this information bias may be differential by the outcome of interest, biasing our results in an unknown direction. The use of audio computer–assisted self-interviews or other types of self-data collection could have improved the collection of sensitive questions such as alcohol and condom use and outside sex partners. Couples were censored if the HIV+ participant started ART, which may have overestimated the proportion of participants who acquire HIV from their study partner (as they are not on ART, and most likely will not be virally suppressed) and underestimate the proportion of participants who acquire HIV from an outside partner. Couples were followed-up every 3 months; however, that amount of time could lead to recall bias on certain measures that may not be salient to the participants. In addition, we did not collect data on condom use with outside partners. As a result, there may be residual confounding in our analysis. Since sex with outside partners was underreported, we used all follow-up intervals rather than follow-up intervals with reported outside exposure in our cumulative measure of exposure to outside partners. As a result, our analysis misclassified the exposures, as we included person-time among couples who had not reported any partners outside the serodiscordant relationship, likely underestimating the incidence rates for those exposed to outside partners.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study found that HIV acquisition from outside partners of serodiscordant couples is high enough to warrant further attention in research and prevention efforts. Factors associated with unlinked infection among men and women included heavy alcohol use, genital inflammation and ulceration, and reporting having outside sex partners among men. Greater understanding of associations between HIV-negative partners' behaviors with outside partners and HIV acquisition will be important for the design of HIV prevention strategies for uninfected partners. Considering the continued HIV exposure from concurrent and outside sex partners, counseling on time-limited PrEP as a “bridge” until the HIV-positive partner is virally suppressed may need to be adapted to allow for longer PrEP use for uninfected partners who may have outside sex partners. In addition, our findings provide further evidence that HIV-negative partners in serodiscordant couples should be regularly screened for symptomatic and, when possible, asymptomatic STIs and other nonsexually transmitted causes of genital inflammation in women. Screening and prophylactic treatment will help reduce genital inflammation and ulceration, which will reduce the risk of HIV acquisition. We also bring attention to the role of heavy alcohol use by men and women in acquisition of HIV from outside partners.

Footnotes

Supported by the National Institutes of Child Health and Development (NICHD R01 HD40125); the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH R01 66767); the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID R01 AI51231; NIAID R01 AI040951; NIAID R01 AI023980; NIAID R01 AI64060; and NIAID R37 AI51231); the AIDS International Training and Research Program Fogarty International Center (D43 TW001042); the Emory Center for AIDS Research (P30 AI050409); the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (5U2GPS000758); and the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative. D.J.D. received post-doctoral support from NIH-NIAID-T32DA023356 and NIH/FIC R25TW009340. This study was made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the responsibility of the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chemaitelly H, Awad SF, Shelton JD, et al. Sources of HIV incidence among stable couples in sub-Saharan Africa. J Int AIDS Soc. 2014;17:18765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chemaitelly H, Awad SF, Abu-Raddad LJ. The risk of HIV transmission within HIV sero-discordant couples appears to vary across sub-Saharan Africa. Epidemics. 2014;6:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kamali A, Price MA, Lakhi S, et al. Creating an African HIV clinical research and prevention trials network: HIV prevalence, incidence and transmission. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0116100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ndase P, Celum C, Thomas K, et al. ; Partners in Prevention HSV/HIV Transmission Study Team. Outside sexual partnerships and risk of HIV acquisition for HIV uninfected partners in African HIV serodiscordant partnerships. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;59:65–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jia Z, Mao Y, Zhang F, et al. Antiretroviral therapy to prevent HIV transmission in serodiscordant couples in China (2003-11): a national observational cohort study. Lancet. 2013;382:1195– 1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ondoa P, Gautam R, Rusine J, et al. Twelve-month antiretroviral therapy suppresses plasma and genital viral loads but fails to alter genital levels of cytokines, in a cohort of HIV-infected Rwandan women. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0127201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karita E, Nsanzimana S, Ndagije F, et al. Implementation and operational research: evolution of couples' voluntary counseling and testing for HIV in Rwanda: from research to public health practice. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;73:e51–e58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Polis CB, Curtis KM. Use of hormonal contraceptives and HIV acquisition in women: a systematic review of the epidemiological evidence. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:797–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Polis CB, Phillips SJ, Curtis KM. Hormonal contraceptive use and female-to-male HIV transmission: a systematic review of the epidemiologic evidence. AIDS. 2013;27:493–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haddad LB, Polis CB, Sheth AN, et al. Contraceptive methods and risk of HIV acquisition or female-to-male transmission. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2014;11:447–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tanser F, Bärnighausen T, Hund L, et al. Effect of concurrent sexual partnerships on rate of new HIV infections in a high-prevalence, rural South African population: a cohort study. Lancet. 2011;378:247–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shelton JD. A tale of two-component generalised HIV epidemics. Lancet. 2010;375:964–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mah TL, Shelton JD. Concurrency revisited: increasing and compelling epidemiological evidence. J Int AIDS Soc. 2011;14:33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mah TL, Halperi DT. Concurrent sexual partnerships and the HIV epidemics in Africa: evidence to move forward. AIDS Behav. 2010;14:11–16. dicussion 34–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Halperin DT, Epstein H. Concurrent sexual partnerships help to explain Africa's high HIV prevalence: implications for prevention. Lancet. 2004;364:4–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seeley J, Nakiyingi-Miiro J, Kamali A, et al. ; CHIVTUM Study Team. High HIV incidence and socio-behavioral risk patterns in fishing communities on the shores of Lake Victoria, Uganda. Sex Transm Dis. 2012;39:433–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hahn JA, Woolf-King SE, Muyindike W. Adding fuel to the fire: alcohol's effect on the HIV epidemic in Sub-Saharan Africa. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2011;8:172–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Coldiron ME, Stephenson R, Chomba E, et al. The relationship between alcohol consumption and unprotected sex among known HIV-discordant couples in Rwanda and Zambia. AIDS Behav. 2008;12:594–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ruzagira E, Wandiembe S, Abaasa A, et al. HIV incidence and risk factors for acquisition in HIV discordant couples in Masaka, Uganda: an HIV vaccine preparedness study. PLoS One. 2011;6–e24037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harling G, Newell ML, Tanser F, et al. Do age-disparate relationships drive HIV incidence in young women? Evidence from a population cohort in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;66:443–451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.WHO. National AIDS Programmes: A Guide to Indicators for Monitoring and Evaluating National HIV/AIDS Prevention Programmes for Young People. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Biraro S, Ruzagira E, Kamali A, et al. HIV transmission within marriage in rural Uganda: a longitudinal study. PLoS One. 2013;8:5506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wall KM, Kilembe W, Vwalika B, et al. Risk of heterosexual HIV transmission attributable to sexually transmitted infections and non-specific genital inflammation in Zambian discordant couples, 1994-2012. Int J Epidemiol. 2017. 10.1093/ije/dyx045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mackelprang RD, Bosire R, Guthrie BL, et al. High rates of relationship dissolution among heterosexual HIV-serodiscordant couples in Kenya. AIDS Behav. 2014;18:189–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kempf MC, Allen S, Zulu I, et al. Enrollment and retention of HIV discordant couples in Lusaka, Zambia. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;47:116–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wall KM, Kilembe W, Nizam A, et al. Promotion of couples' voluntary HIV counselling and testing in Lusaka, Zambia by influence network leaders and agents. BMJ Open. 2012;2:e001171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chomba E, Allen S, Kanweka W, et al. Evolution of couples' voluntary counseling and testing for HIV in Lusaka, Zambia. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2008;47:108–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kelley AL, Karita E, Sullivan PS, et al. Knowledge and perceptions of couples' voluntary counseling and testing in urban Rwanda and Zambia: a cross-sectional household survey. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McKenna SL, Muyinda GK, Roth D, et al. Rapid HIV testing and counseling for voluntary testing centers in Africa. AIDS. 1997;11(suppl 1):S103–S110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dionne-Odom J, Karita E, Kilembe W, et al. Syphilis treatment response among HIV-discordant couples in Zambia and Rwanda. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56:1829–1837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wall KM, Kilembe W, Vwalika B, et al. Hormonal contraception does not increase women's HIV acquisition risk in Zambian discordant couples, 1994–2012. Contraception. 2015;91:480–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Allen S, Meinzen-Derr J, Kautzman M, et al. Sexual behavior of HIV discordant couples after HIV counseling and testing. AIDS. 2003;17:733–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Trask SA, Derdeyn CA, Fideli U, et al. Molecular epidemiology of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 transmission in a heterosexual cohort of discordant couples in Zambia. J Virol. 2002;76:397–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Campbell MS, Mullins JI, Hughes JP, et al. Viral linkage in HIV-1 seroconvertors and their partners in an HIV-1 prevention clinical trial. PLoS One. 2011;6:e16986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Haaland RE, Hawkins PA, Salazar-Gonzalez J, et al. Inflammatory genital infections mitigate a severe genetic bottleneck in heterosexual transmission of subtype A and C HIV-1. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boeras DI, Hraber PT, Hurlston M, et al. Role of donor genital tract HIV-1 diversity in the transmission bottleneck. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:E1156–E1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stephenson R, Vwalika B, Greenberg L, et al. A randomized-control trial to promote long-term contraceptive use among HIV sero-discordant and concordant positive couples in Zambia. J Womens Health. 2011;20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Available at: http://www.aidsinfoonline.org/devinfo/libraries/aspx/Home.aspx. Accessed June 2, 2016.

- 39.Zambian Guidelines on Antiretroviral Therapy, Ministry of Health, Zambia. 2013. Available at: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/en/d/Js19276en/. Accessed June 2, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mujugira A, Celum C, Thomas KK, et al. Delay of antiretroviral therapy initiation is common in East African HIV-infected individuals in serodiscordant partnerships. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;66:436–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Kaufman M, et al. Alcohol use and sexual risks for HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa: systematic review of empirical findings. Prev Sci. 2007;8:141–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dunkle KL, Stephenson R, Karita E, et al. New heterosexually transmitted HIV infections in married or cohabiting couples in urban Zambia and Rwanda: an analysis of survey and clinical data. Lancet. 2008;371:2183–2191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Joseph Davey D, Kilembe W, Wall KM, et al. Risky sex and HIV acquisition among HIV serodiscordant couples in Zambia, 2002–2012: what does alcohol have to do with it? AIDS Behav. 2017. 10.1007/s10461-017-1733-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Young JG, Hernan MA, Picciotto S, et al. Relation between three classes of structural models for the effect of a time-varying exposure on survival. Lifetime Data Anal. 2010;16:71–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morton JF, Celum C, Njoroge J, et al. Counseling framework for HIV-serodiscordant couples on the integrated use of antiretroviral therapy and pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;74(suppl 1):S15–S22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]