Abstract

Fanny Chereau and colleagues assess the risk of the emergence and spread of antibiotic resistance in South East Asia and suggest it is the highest of the World Health Organization regions

Key messages

South East Asia is at high risk of the emergence and spread of antibiotic resistance in humans

The risk assessment framework can help countries identify interventions for maximum impact, although isolated interventions will be inadequate

A comprehensive strategy using the One Health approach is needed to contain antibiotic resistance in South East Asia

The indiscriminate use of antibiotics in human and veterinary medicine and food production and the release of antibiotics into the environment have led to the emergence of antibiotic resistant bacteria and genes. The effectiveness of antibiotics is compromised by the growing resistance, and controlling antibiotic resistance is a priority for the World Health Organization.1 Knowledge is lacking about the biological determinants of the emergence and spread of antibiotic resistance. Evaluating these determinants is important to identify effective interventions to contain antibiotic resistance.

Weak surveillance systems and a lack of data make it difficult to estimate the extent of antibiotic resistance in the WHO South East Asia region. We carried out a qualitative risk assessment to evaluate the relative effects of the main determinants of antibiotic resistance and to estimate the risk of the emergence and spread of antibiotic resistance among humans in the WHO South East Asia region.

Methods

We used the risk assessment approach outlined in box 1 to characterise the level of risk—that is, the likelihood of the emergence and spread of antibiotic resistance among humans—in the WHO South East Asia region. The region includes 11 countries: Bangladesh, Bhutan, Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, India, Indonesia, Maldives, Myanmar, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Thailand, and Timor-Leste.

Box 1: Risk assessment approach and definitions

Risk: Likelihood of the occurrence of a health event

-

Risk assessment: A systematic process to gather, assess, and document information to assign a level of risk.2 It provides the basis for taking action to manage the negative consequences of public health risks. The level of risk assigned to an event depends on a specific hazard, exposure to this hazard, and the context in which the event is occurring. Risk assessment includes three components:

Hazard assessment: identification of the hazard(s) causing the event of interest

Exposure assessment: evaluation of how, and how much, a person, or a population is exposed to the hazard(s)

Context assessment: evaluation of the environment in which the event is taking place. Context factors include socioeconomic, ecological, or programmatic factors

Risk characterisation: It combines the findings from the hazard, exposure, and context assessments to assign a level of risk of the occurrence of the event of interest

Hazard assessment

We first assessed the specific hazards by identifying the important antibiotic resistant bacteria and associated antibiotic resistant genes, such as those with high attributable mortality and high potential for transmission.

WHO has identified seven bacteria with high levels of antibiotic resistance (box 2).3 Of these, extended spectrum β-lactamase and carbapenemase producing Enterobacteriaceae and meticillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) are of greatest concern, as infections have high mortality.4 These pathogens are also commensal bacteria in humans and animals (healthy carriage) and in the environment (water and soil). In the South East Asia region healthy carriage of and infections by extended spectrum β-lactamase producers and MRSA are common.3 5 6 7

Box 2: Bacteria with high levels of antibiotic resistance3

Gram negative bacteria—Neisseria gonorrhoeae with decreased susceptibility to third generation cephalosporins, and Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Shigella spp, and non-typhoidal salmonella with resistance to third generation cephalosporins (including resistance conferred by extended spectrum β-lactamases) and fluoroquinolones or carbapenems

Gram positive bacteria—meticillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus and penicillin resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae

Exposure assessment

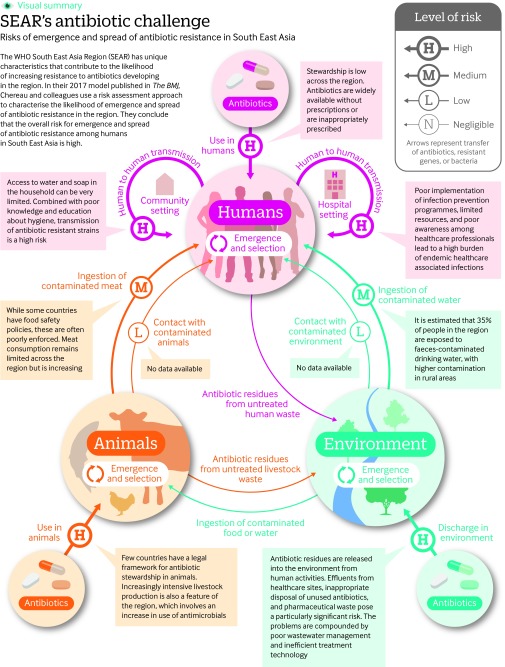

We then described the processes that lead to the acquisition, selection, and spread of the resistant bacteria and genes in humans. The exposure assessment identified the reservoirs (human, animal, and environment) from which antibiotic resistance can emerge, the transmission routes both within and between reservoirs, and the biological determinants of the emergence and transmission of antibiotic resistance. The transmission routes for human acquisition of the antibiotic resistant pathogens are shown in fig 1.

Fig 1 Risks of emergence and spread of antibiotic resistance in South East Asia

The widespread use of antibiotics in human and veterinary medicine for therapeutic or prophylactic purposes is the main driver of the acquisition and selection of antibiotic resistant bacteria.8 9 10 11 The resulting release of active or unmetabolised antibiotics from human and animal waste, from aquaculture, and from pharmaceutical companies into the environment further increases the risk of selection of antibiotic resistance.12 13

Transmission of resistant bacteria and genes to humans is caused by ingestion of contaminated food or water and by direct contact with contaminated animals, soil, or water.8 13 14 15 16 Spread within the human population depends on the capacity for sustained human-to-human transmission. This capacity is still poorly understood.17 In humans, spread of resistance can occur both in the community and in healthcare settings.18 19 High levels of antibiotic use, high density of at-risk individuals, and poor hand hygiene in healthcare settings lead to increased transmission of resistant strains from patients or healthcare workers to other patients by direct contact or through contaminated surfaces.11 20 21 The use of antibiotics in the community is thought to be even greater than in healthcare settings and further increases human-to-human transmission of antibiotic resistance.11

MRSA and extended spectrum β-lactamase strains from healthcare settings or community outbreaks often differ from livestock associated strains.22 This could suggest a limited transmission capacity of strains from animal or environmental origin in humans.17 23 These species barriers are not well understood, and this lack of knowledge impedes the risk assessment process, particularly about the acquisition of resistant bacterial strains from another reservoir.

Context assessment

We assessed the factors specific to the WHO South East Asia region that could affect the causes of the emergence and transmission of resistant strains. The factors were examined at the policy level (scope of policies and guidelines to contain antibiotic resistance in the region), system level (implementation of policies, healthcare system management, wastewater management, and agriculture and livestock management), and individual level (human behaviour and beliefs).

We gathered information from peer reviewed articles, press articles, published documents from WHO, the Food and Agriculture Organization, and Unicef and from unpublished WHO reports. Because of the lack of data available at the country level, the context assessment considered the region as a whole.

Several context factors in the region increase the risk of acquisition, selection, and spread of antibiotic resistance (table 1). Awareness of the drivers of antibiotic resistance, particularly inappropriate antibiotic use, is low among the public and health professionals in most countries of the region.42 Unregulated antibiotic distribution and poor implementation of antibiotic stewardship programmes in humans 27 lead to overuse and misuse of antibiotics. Wastewater management is inadequate. About 75% of wastewater is not treated in the countries of the region and is directly released into the environment, thus contaminating natural drinking water sources where access to piped or improved water supplies is limited.37 Even when water is treated, the effectiveness of removal of contaminants is limited.33

Table 1.

Risk assessment for events of antibiotic resistance emergence and transmission in the WHO South East Asia region

| Event | Main cause of the event | Risk of event arising from main cause | Factors in South East Asia region affecting main cause | Effect of factors on the likelihood of the event occurring | Risk of the event adjusted for context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emergence and selection in humans | Use of antibiotics in humans | High |

Level of antibiotic stewardship for human health

Policy: Few of the 11 countries have an antibiotic stewardship policy framework, or programmes, and nine countries have a national regulatory agency for medicines.24 25 System: Poor enforcement of existing policies for medicines regulation, and poor enforcement of quality standards for antibiotics. No monitoring of antibiotic use and sales.25 Several countries do not have specific training/education programmes on antibiotic stewardship for health professionals. Lack of campaigns to raise awareness.25 26 Individual level: Poor prescribing practices among health professionals. Low level of compliance with prescriptions and poor awareness among the general public.24 27 |

Increase Human consumption of antibiotics is growing in the region, with India being the largest consumer worldwide in 2010.28 Antibiotics are available without a prescription in seven countries,25 and substandard quality of antibiotics is common.29 Inappropriate prescription by doctors, inappropriate antibiotic courses, and self-medication occur.27 |

High |

| Emergence and selection in animals | Use of antibiotics in animals | High |

Level of antibiotic stewardship for animal health and production

Policy: Few countries have a legal framework for antibiotic stewardship in animals. Many countries have developed, or are developing, national strategies for containment of antimicrobial resistance targeting animal health. Only four countries ban antibiotics as growth promotors.30 31 System: Poor enforcement of existing policies.31 Individual level: Limited awareness of, and knowledge about, antibiotic resistance, and antibiotic use among veterinarians and farmers. Illegal use of antibiotics as growth promoters is common. |

Increase More intensive livestock production has started, leading to an increase in the use of antimicrobials. An increase in antibiotic use is projected by 2030 (particularly in India, Indonesia, and Myanmar).32 Excessive use of antibiotics for growth promotion, prophylaxis, or metaphylaxis (mass administration to prevent infection, or spread of disease). |

High |

| Emergence and selection in the environment | Release of antibiotic residues and antibiotic resistant bacteria or genes into the environment | Moderate |

Level of wastewater management

Policy: Limited regulation on antibiotic release from pharmaceutical industries, healthcare settings, or aquaculture. System: Poor wastewater management and inefficient treatment technology. |

Increase Antibiotics are released into the environment from healthcare settings, aquaculture activities, and pharmaceutical industries 33. India is among the main antibiotic producers worldwide; Bangladesh, Indonesia, and Thailand also produce antibiotics. Inadequate safe disposal of healthcare waste (<45% of healthcare facilities have adequate systems).34 Limited amounts (20-30%) of wastewater are treated in treatment plants (see regional workshop reports at www.ais.unwater.org/ais/course/view.php?id=6), and treatment methods are not effective in eliminating antibiotic residues, or antibiotic resistant bacteria and genes.33 |

High |

| Foodborne transmission to humans | Ingestion of contaminated food | Low |

Level of food safety

Policy: Several countries do not have a specific food safety policy, although action plans have been developed in all countries.35 Only India, Indonesia, Maldives, Nepal, and Thailand have a food safety agency. System: Poor enforcement of regulations.35 Difficulty in implementing policies in small farms or slaughterhouses. Only Indonesia and Thailand have premarketing inspection and standardised food surveillance (Bhutan to some extent), analytical capacities vary. Standards for domestic food differ from those for exported food. Individual level: Poor awareness of and compliance with existing regulations among food service providers and retailers. Poor awareness of food handling practices in the general population. |

Increase Meat consumption has increased in countries in the past few years (http://faostat3.fao.org/). In Thailand, extended spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae have been isolated in the pork food chain from farms (75% of pigs were colonised with extended spectrum β-lactamase producers), slaughterhouses (20% of pork meat samples tested positive for extended spectrum β-lactamase producers), and market retailers, but contamination of cooked meat in markets was uncommon.36 |

Moderate |

| Waterborne transmission to humans | Ingestion of contaminated water | Low |

Level of water safety

Policy: No available data. System: Insufficient treatment of distributed water for removal of antibiotic resistant bacteria and genes. Low coverage of piped water, especially in rural settings, and lack of infrastructure maintenance. No surveillance for detection of water contamination, and no response measures. Individual level: Low awareness of water treatment and household storage in the general population. |

Increase About 35% of the population of the countries in the region are exposed to drinking water contaminated with faeces, with higher contamination in rural areas and in unimproved water sources.37 38 Antibiotic resistant genes have been isolated in drinking water in several countries including India, Bangladesh, and Nepal. |

Moderate |

| Environment Soil, water, air-to-human direct transmission | Contact with contaminated environment | Negligible | No available data | Unknown | Negligible |

| Animal-to-human direct transmission | Contact with contaminated animal | Negligible | No available data | Unknown | Negligible |

| Human-to-human transmission | Transmission in healthcare settings | Moderate |

Level of infection prevention and control (IPC)

Policy: Nine countries have national IPC programmes.25 Low level of governmental health expenditure.39 System: Weak implementation of IPC programmes in healthcare settings. No systematic testing and isolation, few tools for diagnosis and identification of resistance patterns for appropriate treatment, no centralised registers of patients, no active healthcare associated infection surveillance, and poor hygiene and sanitation in healthcare settings.34 Limited resources, and poor healthcare infrastructure and equipment, particularly for IPC.40 Individual level: Poor awareness among healthcare workers of IPC practices. |

Increase Limited data available, but the burden of endemic healthcare associated infections is very high.41 |

High |

| Transmission in the community | Moderate |

Measures to control antibiotic resistance transmission through hygiene and sanitation in the community

Policy: Lack of national programmes or campaigns on hygiene, and sanitation. System: Low regional coverage of piped water on premises, particularly in rural settings, and lack of infrastructure maintenance and technical support from institutions to the community. Individual level: Poor education on hygiene. |

Increase Access to water and soap in the household can be limited, and correlated with poverty. Access to improved sanitation facilities is <50% in four countries, and 11% of toilet facilities are shared. Only five countries met the millennium development goal target for sanitation.37 The indiscriminate use of antibiotics in the community might increase the transmission rates of antibiotic resistant strains. |

High |

The lack of antibiotic stewardship programmes results in the inappropriate use of antibiotics in livestock and aquaculture. Furthermore, poor infection control practices in farms lead to the selection and spread of resistant strains.31 Antibiotic use in livestock is expected to rise because of increased production in response to a growing demand for food from animal sources.32 International food safety and quality standards have reduced antibiotic use in animal products intended for export; however, the same is not true for livestock products for domestic consumption. Other regional challenges include the limited ability to detect and measure resistance in the human population. Our recent analysis of national programmes to tackle antimicrobial resistance43 showed limited capacity for microbiology and antibiotic susceptibility testing in most public hospitals in the region; only Thailand has data on the national trends for extended spectrum β-lactamase and carbapenemase producing Enterobacteriaceae. Early diagnosis and active surveillance are lacking thus delaying implementation of infection control measures. Also, efforts to identify animal and environmental reservoirs and to detect antibiotic resistance in the food chain and water systems are limited across the region.31

Risk characterisation for the WHO South East Asia region

To characterise the level of risk of the emergence and spread of antibiotic resistance among humans in the WHO South East Asia region, we integrated the risk assessment findings described above in a two layer model (table 1). The first layer is based on the exposure assessment of reservoirs, transmission routes, and determinants. The second layer considers the context factors in the region.

The risk—that is, likelihood of occurrence of each event (acquisition, selection, transmission of antibiotic resistance)—was rated using a qualitative approach as:

Negligible—the event occurs under exceptional circumstances

Low—the event occurs some of the time

Moderate—the event occurs regularly

High—the event occurs in most circumstances.

Based on this approach, we first rated the level of risk for each event arising from the main causes of the emergence and spread of antibiotic resistance (independent of the context). We then estimated the effect of the context factors on the strength of the main causes.

Several studies argue that the emergence of antibiotic resistance in humans is primarily driven by inappropriate and overuse of antibiotics among humans and animals, compared with environmental antibiotic contamination. We therefore considered that antibiotic use leads to a high risk of emergence of antibiotic resistance in both human and animal reservoirs.14 44 Human-to-human transmission in the community, which has long been underestimated, could have the same effect on the spread of antibiotic resistance as transmission in healthcare settings,18 19 and we estimated these risks as moderate. Transmission of resistant bacteria to human populations through foodborne, or waterborne routes combines a high exposure rate to potentially contaminated food or water with a very low probability of transmission and acquisition of resistance in humans. We therefore considered the risk caused by foodborne and waterborne exposures to be low. Direct contact with contaminated animals or environmental elements is rarely reported, but it is possible that a limited number of people are exposed; we thus considered the risk of transmission to be negligible.

Based on our judgment, and on available documentation, a context factor was classified as decreasing or increasing the strength of a cause of the emergence and spread of antibiotic resistance, and thus decreasing or increasing the likelihood of the occurrence of an event or as having a negligible effect (table 1).

We determined the overall risk of each event occurring in the region by combining the effect of the context factors with the risk from the factors causing the emergence, and spread of antibiotic resistance (fig 1).

For example, we estimated that discharge of antibiotics and antibiotic resistant bacteria and genes into the environment was a moderate risk for selection of resistance and that the low level of wastewater management increased the risk, making it high (fig 1).

We chronologically integrated all the events in the chain leading to the transmission of antibiotic resistance in the human population. To calculate the risk from two consecutive and dependent events in the model, we applied a combination matrix (fig 1).45 When several independent events contributed to the estimation of the risk, the event with the highest risk was used. For example, the transmission of antibiotic resistance from the environment to humans is dependent on the emergence and selection of resistance in the environment. Using the combination matrix,45 we estimated that the emergence and selection of resistance in the environment, which we rated as a high risk in the region, followed by the environment-to-human transmission of resistance, which we rated as a negligible risk in the region, led to a low level risk of acquisition of resistance among humans (fig 1).

Discussion

Given the size of the population, the high burden of bacterial infections, the high rate of antibiotic resistance, and the contribution of context factors identified in this risk assessment, we believe that the overall risk of the emergence and spread of antibiotic resistance among humans in the WHO South East Asia region is among the highest of the WHO regions. The risk of transmission of antibiotic resistance from animal or environmental reservoirs to humans is high in the context of this region and is mediated by the high risks of foodborne and waterborne transmission. We estimated a high risk of transmission of resistance in healthcare settings and in the community, leading to an overall high risk of transmission of antibiotic resistance among humans in the region.

Although the conclusion could have been reached intuitively, our model considered the main biological causes of antibiotic resistance events and factors specific to the WHO South East Asia region and provides an overall picture of the factors affecting antibiotic resistance. Our assessment highlights the limited benefits of isolated interventions in a specific sector and the need for coordinated interventions to reduce the risk of the emergence and spread of antibiotic resistance. The One Health 46 approach recommends linking human health and animal and environmental health in planning interventions to tackle antibiotic resistance.

This study has some limitations. First, we focused on the pathogens of international concern. The risks of each event cannot be generalised to pathogens not included here. Second, we did not do a systematic review of the literature to quantify risk estimates. The effects of some determinants on the occurrence of specific events are not reported (contribution of antibiotic resistance in the environment to resistance among humans) or are controversial (contribution of antibiotic use in livestock to resistance among humans17). These knowledge gaps hindered our estimates of risk. In view of these gaps, listed in box 3, we considered a higher level of risk when uncertainty was high.

Box 3: Knowledge gaps hindering assessment of the risk of emergence or transmission of antibiotic resistance

Acquisition and selection in humans

Rates of horizontal gene transfer from non-pathogenic commensal bacteria

Effect of dose and duration of antibiotic course on antibiotic resistance

Reversibility of resistance after withdrawal of antimicrobial

Acquisition and selection in livestock

Reversibility of antimicrobial resistance after withdrawal of antimicrobial

Acquisition and selection in the environment

Persistence of antibiotics in soil, sediment, or water

Persistence of antibiotic resistant bacteria/antibiotic resistant genes in soil, sediment, or water

Risks from non-environmental bacteria released in environment

Rates of horizontal gene transfer from non-environmental to environmental bacteria

Minimum environmental concentration necessary to select resistance for different antibiotic classes

Animal-to-human transmission

Dose-response and risk factors for persistence of antibiotic resistant bacteria from animal origin in human flora following ingestion

Routes, risk factors, and rates of transmission of animal bacteria to human flora other than through ingestion

Risk factors and rates of horizontal gene transfer from animal bacteria to human bacteria in different human flora (intestinal, skin, nasopharyngeal)

Efficiency for sustained human-to-human transmission of bacteria or genes from animal origin

Environment-to-human transmission

Dose-response, and risk factors for persistence of antibiotic resistant bacteria from aquatic origin in human flora following ingestion

Routes, risk factors, and rates of transmission of environmental bacteria to human flora other than through ingestion

Rates of horizontal gene transfer from environmental to human bacteria in the different human flora (intestinal, skin, nasopharyngeal)

Efficiency of wastewater treatment on elimination of antibiotics, and antibiotic resistant genes

Transmission in healthcare settings

Routes, risk factors, and rates of human-to-human transmission of resistant bacteria in healthcare settings

Efficiency of community acquired strains to spread in healthcare settings

Transmission in the community

Routes, risk factors, and rates of human-to-human transmission of resistant bacteria in the community

Efficiency of hospital acquired strains to spread in the community

This qualitative risk assessment framework is in the early stages of development. Each step depends on more than one main biological determinant, and all steps and associated determinants need to be defined to develop a systematic risk model—semi-qualitative or quantitative—in the future. With such a model, it might be possible to get accurate estimates of risk and to measure the effectiveness of interventions on defined outcomes.

In conclusion, despite uncertainties, risk assessment models are needed to characterise the level of risk and to identify important interventions to reduce this risk and to reduce knowledge and system gaps while analysing processes and outcomes. We believe such a model with defined parameters will be of interest at the country level to identify system weaknesses, and assess the effect of measures to control antibiotic resistance.

Web Extra Extra material supplied by the author

Infographic depicting the challenge of antibiotic resistance in South East Asia

Contributors and sources: FC and SV wrote the article, LO and MT reviewed the article, SV designed the study, LO, FC, and SV designed the framework model, and FC, LO, and MT searched the literature. All authors reviewed, and approved the final manuscript. SV is the guarantor. The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors, and do not necessarily represent those of the institutions with which the authors are affiliated.

Competing interests: We have read and understood BMJ policy on declaration of interests, and declare funding from the UK Department of Health Fleming Fund.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

This article is one of a series commissioned by The BMJ based on an idea from WHO SEARO. The BMJ retained full editorial control over external peer review, editing, and publication.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Global action plan on antimicrobial resistance. 2015. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/193736/1/9789241509763_eng.pdf?ua=1 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.World Health Organization. Rapid risk assessment of acute public health events. 2012 http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/70810/1/WHO_HSE_GAR_ARO_2012.1_eng.pdf

- 3. World Health Organization. Antimicrobial resistance: global report on surveillance. 2014. . http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/112642/1/9789241564748_eng.pdf?ua=1 [Google Scholar]

- 4.ECDC. EMEA. The bacterial challenge: time to react. 2009. https://ecdc.europa.eu/sites/portal/files/media/en/publications/Publications/0909_TER_The_Bacterial_Challenge_Time_to_React.pdf

- 5.Woerther P-L, Burdet C, Chachaty E, Andremont A. Trends in human fecal carriage of extended-spectrum β-lactamases in the community: toward the globalization of CTX-M. Clin Microbiol Rev 2013;26:744-58. 10.1128/CMR.00023-13 pmid:24092853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen C-J, Huang Y-C. New epidemiology of Staphylococcus aureus infection in Asia. Clin Microbiol Infect 2014;20:605-23. 10.1111/1469-0691.12705 pmid:24888414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karanika S, Karantanos T, Arvanitis M, Grigoras C, Mylonakis E. Fecal colonization with extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae and risk factors among healthy individuals: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2016;63:310-8. 10.1093/cid/ciw283 pmid:27143671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Food and Agriculture Organization. Drivers, dynamics and epidemiology of antimicrobial resistance in animal production. 2016. https://www.mrc.ac.uk/documents/pdf/antimicrobial-resistance-timeline-report/

- 9.Bell BG, Schellevis F, Stobberingh E, Goossens H, Pringle M. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of antibiotic consumption on antibiotic resistance. BMC Infect Dis 2014;14:13 10.1186/1471-2334-14-13 pmid:24405683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Landers TF, Cohen B, Wittum TE, Larson EL. A review of antibiotic use in food animals: perspective, policy, and potential. Public Health Rep 2012;127:4-22. 10.1177/003335491212700103 pmid:22298919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lipsitch M, Samore MH. Antimicrobial use and antimicrobial resistance: a population perspective. Emerg Infect Dis 2002;8:347-54. 10.3201/eid0804.010312 pmid:11971765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wellington EMH, Boxall AB, Cross P, et al. The role of the natural environment in the emergence of antibiotic resistance in gram-negative bacteria. Lancet Infect Dis 2013;13:155-65. 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70317-1 pmid:23347633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Taylor NGH, Verner-Jeffreys DW, Baker-Austin C. Aquatic systems: maintaining, mixing and mobilising antimicrobial resistance?Trends Ecol Evol 2011;26:278-84. 10.1016/j.tree.2011.03.004 pmid:21458879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith DL, Dushoff J, Morris JG. Agricultural antibiotics and human health. PLoS Med 2005;2:e232 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020232 pmid:15984910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Founou LL, Founou RC, Essack SY. Antibiotic resistance in the food chain: a developing country-perspective. Front Microbiol 2016;7:1881 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01881 pmid:27933044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aarestrup FM. The livestock reservoir for antimicrobial resistance: a personal view on changing patterns of risks, effects of interventions and the way forward. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2015;370:20140085 10.1098/rstb.2014.0085 pmid:25918442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chang Q, Wang W, Regev-Yochay G, Lipsitch M, Hanage WP. Antibiotics in agriculture and the risk to human health: how worried should we be?Evol Appl 2015;8:240-7. 10.1111/eva.12185 pmid:25861382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knox J, Uhlemann A-C, Lowy FD. Staphylococcus aureus infections: transmission within households and the community. Trends Microbiol 2015;23:437-44. 10.1016/j.tim.2015.03.007 pmid:25864883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hilty M, Betsch BY, Bögli-Stuber K, et al. Transmission dynamics of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in the tertiary care hospital and the household setting. Clin Infect Dis 2012;55:967-75. 10.1093/cid/cis581 pmid:22718774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lawes T, Lopez-Lozano J-M, Nebot CA, et al. Effects of national antibiotic stewardship and infection control strategies on hospital-associated and community-associated meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infections across a region of Scotland: a non-linear time-series study. Lancet Infect Dis 2015;15:1438-49. 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00315-1 pmid:26411518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tacconelli E, Cataldo MA, Dancer SJ, et al. European Society of Clinical Microbiology. ESCMID guidelines for the management of the infection control measures to reduce transmission of multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria in hospitalized patients. Clin Microbiol Infect 2014;20(Suppl 1):1-55. 10.1111/1469-0691.12427 pmid:24329732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCarthy AJ, Loeffler A, Witney AA, Gould KA, Lloyd DH, Lindsay JA. Extensive horizontal gene transfer during Staphylococcus aureus co-colonization in vivo. Genome Biol Evol 2014;6:2697-708. 10.1093/gbe/evu214 pmid:25260585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hetem DJ, Bootsma MCJ, Troelstra A, Bonten MJM. Transmissibility of livestock-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Emerg Infect Dis 2013;19:1797-802. 10.3201/eid1911.121085 pmid:24207050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Health Organization Regional Office for South-East Asia. Antimicrobial resistance. Report of a regional meeting Jaipur, India, 10–13 November 2014. 2015 http://www.searo.who.int/entity/antimicrobial_resistance/sea_hlm_423.pdf?ua=1 (accessed March 20, 2017).

- 25. World Health Organization. Worldwide country situation analysis: response to antimicrobial resistance. 2015. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/163468/1/9789241564946_eng.pdf?ua=1&ua=1 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Godhino N, Bezbaruah S, Neyyar S, et al. Antimicrobial resistance communication activities in South East Asia. BMJ 2017;358:j2742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holloway KA, Kotwani A, Batmanabane G, Puri M, Tisocki K. Antibiotic use in South East Asia and policies to promote appropriate use: reports from country situational analyses. BMJ 2017;358:j2440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gelband H, Miller-Petrie M, Pant S, et al. The state of the world’s antibiotics, 2015. The Center for Disease Dynamics, Economics & Policy, 2015 http://www.cddep.org/publications/state_worlds_antibiotics_2015#sthash.40to7lRd.aUiQVDOc.dpbs.

- 29.Kelesidis T, Falagas ME. Substandard/counterfeit antimicrobial drugs. Clin Microbiol Rev 2015;28:443-64. 10.1128/CMR.00072-14 pmid:25788516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chuanchuen R, Pariyotorn N, Siriwattanachai K, et al. Review of the literature on antimicrobial resistance in zoonotic bacteria from livestock in East, South and Southeast Asia. Food and Agriculture Organization Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific. 2014 http://cdn.aphca.org/dmdocuments/REP_AMR_141022_c.pdf.. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goutard FL, Bourdier M, Calba C, et al. Antimicrobial policy interventions in food animal production in South East Asia. BMJ 2017;358:j3544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Boeckel TP, Brower C, Gilbert M, et al. Global trends in antimicrobial use in food animals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015;112:5649-54. 10.1073/pnas.1503141112 pmid:25792457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lundborg CS, Tamhankar AJ. Antibiotic residues in the environment of South East Asia. BMJ 2017;358:j2440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.World Health Organization, Unicef. Water, sanitation and hygiene in health care facilities. Status in low- and middle-income countries and way forward. 2015. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/154588/1/9789241508476_eng.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 35. World Health Organization Regional Office for South-East Asia. Regional food safety strategy. 2014. http://www.searo.who.int/entity/foodsafety/regional-food-strategy.pdf?ua=1. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boonyasiri A, Tangkoskul T, Seenama C, Saiyarin J, Tiengrim S, Thamlikitkul V. Prevalence of antibiotic resistant bacteria in healthy adults, foods, food animals, and the environment in selected areas in Thailand. Pathog Glob Health 2014;108:235-45. 10.1179/2047773214Y.0000000148 pmid:25146935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.World Health Organization. Unicef. A snapshot of drinking water and sanitation in WHO South-East Asia Region. 2014. http://www.searo.who.int/entity/water_sanitation/data/watsancoverage.pdf?ua=1.

- 38.Bain R, Cronk R, Hossain R, et al. Global assessment of exposure to faecal contamination through drinking water based on a systematic review. Trop Med Int Health 2014;19:917-27. 10.1111/tmi.12334 pmid:24811893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Majumder MAA. Economics of healthcare financing in WHO South East Asia Region. South East Asia J Public Health 2013;2:3-4 10.3329/seajph.v2i2.15936. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40. World Health Organization Regional Office for South-East Asia. Regional strategy for patient safety in the WHO South-East Asia Region. 2015. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/205839/1/B5215.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ling ML, Apisarnthanarak A, Madriaga G. The burden of healthcare-associated infections in southeast Asia: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2015;60:1690-9. 10.1093/cid/civ095 pmid:25676799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Holloway KA, Kotwani A, Batmanabane G, et al. Antibiotic use in South East Asia and policies to promote appropriate use: reports from country situational analyses. BMJ 2017;358:j2991 10.1136/bmj.j2291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kakkar M, Walia K, Vong S, et al. Antibiotic resistance and its containment in India. BMJ 2017;358:j2687 10.1136/bmj.j2687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Holmes AH, Moore LSP, Sundsfjord A, et al. Understanding the mechanisms and drivers of antimicrobial resistance. Lancet 2016;387:176-87. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00473-0 pmid:26603922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wieland B, Dhollander S, Salman M, Koenen F. Qualitative risk assessment in a data-scarce environment: a model to assess the impact of control measures on spread of African Swine Fever. Prev Vet Med 2011;99:4-14. 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2011.01.001. pmid:21292336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. One Health. https://www.cdc.gov/onehealth/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Infographic depicting the challenge of antibiotic resistance in South East Asia