Abstract

As an increasingly common cause of skin infections worldwide, the prevalence of antibiotic-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) across China has not been well documented. This literature aims to study the resistance profile to commonly used antibiotics, including macrolides, fusidic acid (FA) and mupirocin, and its relationship to the genetic typing in 34 S. aureus strains, including 6 methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA), isolated from a Chinese hospital. The MIC results showed 27 (79.4%), 1 (2.9%) and 6 (17.6%) isolates were resistant to macrolides, FA and mupirocin, respectively. Among 27 macrolide-resistant S. aureus isolates, 5 (18.5%) were also resistant to mupirocin and 1 (3.7%) to FA. A total of 13 available resistant genes were analyzed in 28 antibiotic-resistant strains using polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The positive rates of macrolide-resistant ermA, ermB, ermC, erm33 and low level mupirocin-resistant ileS mutations were 11.1%, 25.9%, 51.9%, 7.4% and 100%, respectively. Other determinants for FA- and high level mupirocin-resistance were not found. The results of multilocus sequence typing (MLST) and pulsed field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) revealed 13 sequence types (STs) and 18 clusters in 23 resistant gene positive S. aureus isolates. Among these STs, ST5 was most prevalent, accounting for 18.2%. Notably, various clusters were found with similar resistance phenotype and genotype, exhibiting a weak genetic relatedness and high genetic heterogeneities. In conclusion, macrolides, especially erythromycin, are not appropriate to treat skin infections caused by S. aureus, and more effective measures are required to reduce the dissemination of macrolides, FA and mupirocin resistance of the pathogen.

Keywords: Staphylococcus aureus, macrolides, fusidic acid (FA), mupirocin, resistance

INTRODUCTION

As one of the most common pathogens, S. aureus usually caused systemic and pyogenic local infections in both community settings and hospitals. Moreover, due to the existence of virulence factors of S. aureus, it tends to cause more widespread infections, such as meningitis, endocarditis and blood stream infections [1]. The topical antimicrobial agents, especially macrolide antibiotic erythromycin, fusidic acid (FA), mupirocin, are commonly used to treat skin infections caused by S. aureus.

Macrolides are widely used to treat acute upper and lower respiratory tract infections, sexually transmitted diseases and chronic pulmonary infections. In addition, they also applied to skin and soft tissue infections [2]. As the first macrolide antibiotic discovered in 1952, erythromycin played an important role in treating infectious diseases. Since then, more active semi-synthetic derivatives, such as azithromycin and clarithromycin, have been developed [3]. Resistance to macrolides gradually emerged along with their extensive use for treating S. aureus. So far, three kinds of mechanisms are responsible for resistance to macrolides in S. aureus, including an active efflux pump encoded by msrA gene, enzymatic inactivation of antibiotics, and ribosomal target modification in ermA, ermB, ermC and erm33 genes. Among these three mechanisms, the last one is the primary mechanism involved [2, 4].

As an effective antibiotic, FA is often used to treat diseases, including skin and soft tissue infections, acute osteomyelitis, septic arthritis and other device related infections, which are caused by S. aureus [5]. Being extracted from cultures of fusidium coccineum, FA inhibits bacterial protein synthesis by preventing the turnover of fusA encoded elongation factor G (EF-G) from the ribosome [6, 7]. Point mutations in this chromosomal gene usually lead to the high level resistance of FA [8]. Low level resistance arises via the FusB-family proteins (encoded by fusB, fusC or fusD) which can protect drug target site from binding with FA molecules [9]. In addition, mutations in rplF encoded ribosomal protein L6 (collectively called fusE mutants) can also lead to low level FA resistance [10].

Mupirocin, also called pseudomonic acid A, is mainly used to treat skin, soft tissue and postoperative wound infections and can also eliminate nasal MRSA carriage from healthcare workers [11, 12]. As an isoleucine analogue produced by Pseudomonas fluorescens, mupirocin kills bacteria by competitively binding to isoleucine-tRNA synthetase (IRS), and consequently interfering with protein synthesis [13]. There are two categories of mupirocin resistances: low level resistance and high level resistance. Low level resistance is usually caused by point mutations, including A637G, G1762T, G1891T, T1984A and A2412T in the chromosomal staphylococcal isoleucine-tRNA synthetase (ileS) gene [14, 15]. High level resistance is commonly mediated by mupA (also referred to as ileS2) encoding an additional modified IRS [16, 17]. In addition, high level mupirocin resistance can also be caused by the mobile resistance gene mupB [18].

Antibiotic resistance to erythromycin, FA and mupirocin is an increasingly serious problem worldwide [19]. To provide an update to the antibiotic resistance of S. aureus in China, here, we systematically investigated the epidemiology and molecular characteristics of S. aureus from a university hospital in East China, and performed a comprehensive evaluation and comparison of their genetic diversity.

RESULTS

Antimicrobial susceptibility of S. aureus clinical isolates

To understand the resistance to macrolides, FA and mupirocin of 34 S. aureus isolates collected from a hospital, antimicrobial susceptibility testing was performed. The results showed that the resistance rates to erythromycin, clarithromycin, azithromycin, dirithromycin, FA and mupirocin accounted for 73.5% (25/34), 70.6% (24/34), 64.7% (22/34), 73.5% (25/34), 2.9% (1/34) and 17.6% (6/34), respectively (Table 1). The high resistance to macrolides in the present study indicated these macrolides were not applicable to treat S. aureus infections induced by resistant strains. Meanwhile, low resistance to FA and mupirocin indicated these two antibiotics remained effective for the therapy of infections caused by S. aureus. In total, we identified 28 antibiotic resistant isolates including 27 macrolide-resistant, 1 FA-resistant and 6 mupirocin-resistant isolates (Table 2).

Table 1. The antimicrobial resistance rates of S.aureus isolates including MSSA and MRSA.

| Antimicrobial agent | SA, % (n/34) | MSSA, % (n/28) | MRSA, % (n/6) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ERY | 73.5% (25/34) | 67.9% (19/28) | 100.0% (6/6) |

| CLR | 70.6% (24/34) | 67.9% (19/28) | 83.3% (5/6) |

| AZM | 64.7% (22/34) | 60.7% (17/28) | 83.3% (5/6) |

| DTM | 73.5% (25/34) | 71.4% (20/28) | 83.3% (5/6) |

| FA | 2.9% (1/34) | 3.6% (1/28) | 0% (0/6) |

| MUP | 17.6% (6/34) | 21.4% (6/28) | 0% (0/6) |

ERY, erythromycin; CLR, clarithromycin; AZM, azithromycin; DTM, dirithromycin; FA, fusidic acid; MUP, mupirocin; SA, Staphylococcus aureus, MSSA, methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus; MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus.

Table 2. Molecular resistance characteristics of 28 antibiotic-resistant S. aureus isolates.

| Resistance phenotype (MIC in μg/ml) | Genotype | MRSA | MSSA | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isolate no. | Macrolides | FA | MUP | Macrolide-resistant gene | MUP-resistant gene mutaion | ||||||||

| ERY | AZM | CLR | DTM | ermA | ermB | ermC | erm33 | ileS A637G mutation | |||||

| 016 | 256R | 4S | 256R | 256R | 0.125S | 4S | - | - | - | - | - | - | + |

| 017 | 256R | 256R | 256R | 256R | 0.125S | 512H | - | - | + | - | + | - | + |

| 022 | 256R | 256R | 32R | 128R | 0.125S | 2S | - | + | - | - | - | - | + |

| 023 | 4S | 0.125S | 0.25S | 256R | 0.125S | 2S | - | - | - | - | - | - | + |

| 026 | 256R | 256R | 256R | 256R | 0.125S | 4S | - | - | + | - | - | - | + |

| 029 | 256R | 4S | 256R | 256R | 0.125S | 512H | - | + | - | - | + | - | + |

| 034 | 256R | 0.125S | 0.25S | 0.5S | 0.125S | 4S | - | + | - | - | - | - | + |

| 038 | 256R | 256R | 256R | 256R | 0.125S | 256L | - | + | + | - | + | - | + |

| 041 | 256R | 256R | 256R | 256R | 2L | 2S | - | + | - | - | - | - | + |

| 049 | 2S | 2S | 0.25S | 0.5S | 0.125S | 1024H | - | - | - | - | + | - | + |

| 052 | 256R | 128R | 256R | 256R | 0.125S | 4S | - | - | + | - | - | - | + |

| 053 | 256R | 128R | 256R | >256R | 0.125S | 4S | - | + | - | - | - | - | + |

| 055 | 64R | 128R | 256R | 256R | 0.125S | 2S | - | - | + | - | - | - | + |

| 060 | 256R | 64R | 256R | 256R | 0.125S | 2S | - | - | + | - | - | - | + |

| 083 | 256R | 64R | 256R | 128R | 0.125S | 2S | - | - | - | - | - | - | + |

| 085 | 256R | 64R | 256R | 128R | 0.125S | 1024H | - | + | - | - | + | - | + |

| 092 | 256R | 64R | 256R | 128R | 0.125S | 2S | - | - | - | - | - | - | + |

| 097 | 1S | 64R | 256R | 128R | 0.125S | 1024H | + | - | - | - | + | - | + |

| 107 | 256R | 128R | 256R | 128R | 0.125S | 2S | - | - | + | - | - | - | + |

| 108 | 256R | 128R | 256R | 256R | 0.125S | 2S | + | - | + | - | - | - | + |

| 114 | 256R | 128R | 256R | 128R | 0.125S | 2S | - | - | + | - | - | - | + |

| 116 | 256R | 128R | 256R | 256R | 0.125S | 2S | - | - | + | - | - | - | + |

| 117 | 64R | 128R | 256R | 256R | 0.125S | 2S | - | - | + | - | - | + | - |

| 118 | 64R | 128R | 256R | 256R | 0.125S | 2S | + | - | - | + | - | + | - |

| 119 | 64R | 128R | 256R | 256R | 0.125S | 2S | - | - | + | - | - | + | - |

| 120 | 64R | 0.5S | 0.25S | 0.25S | 0.125S | 2S | - | - | + | - | - | + | - |

| 133 | 64R | 128R | 256R | 256R | 0.125S | 2S | - | - | + | + | - | + | - |

| 134 | 64R | 128R | 256R | 256R | 0.125S | 2S | - | - | - | - | - | + | - |

| Total no. | 3 | 7 | 14 | 2 | 6 | 6 | 22 | ||||||

The antibiotic-resistant S. aureus indicated macrolide-, FA- or mupirocin-resistant isolates. Abbreviations for ERY, AZM, CLR, DTM, FA and MUP are the same as in Table 1. The macrolides, Fusidic acid and mupirocin resistance level were indicated in the MATERIALS AND METHODS R, resistance; S, susceptibility; H, high level resistance; L, low level resistance; +, positive; -, negative.

For cross-resistance profile in these isolates, we found the only FA-resistant (isolate no. 041) and 5 of 6 mupirocin-resistant isolates (except isolate no. 049) also belong to the 27 macrolide-resistant S. aureus isolates (Table 2). We further determined the resistance level of FA- and mupirocin-resistant isolates. The only FA-resistant isolate was identified to be low level resistance with a MIC of 2 μg/ml (Table 2). Among the 6 mupirocin-resistant S. aureus isolates, 1 (isolate no. 038, 16.7%) was low level resistance with a MIC of 256 μg/ml, and the other 5 (83.3%) were high level resistance with MICs of 512-1024 μg/ml (Table 2). These data demonstrated that macrolide-resistant S. aureus could be generally eradicated by FA and mupirocin, and there is an inclination for FA- and mupirocin-resistant isolates to develop multi-drug resistance.

6 MRSA were included in our collection and their resistance to macrolides, FA and mupirocin was also tested. For four macrolide antibiotics, our result showed all 6 MRSA isolates were resistant to erythromycin and 5 (83.3%) to other three macrolide antibiotics (Table 1 and 2). We found all 6 MRSA isolates were also susceptible to FA and mupirocin (Table 1 and 2), which suggested FA and mupirocin were still applicable to treat MRSA infections.

Prevalence of antimicrobials resistance determinants

To determine the resistance genes or gene mutations in 28 antibiotic-resistant S. aureus, PCR was conducted (Supplementary Figure 1). We first detected macrolide-resistant genes in 27 macrolide-resistant isolates. The results showed that macrolide-resistant S. aureus isolates harbored ermA (11.1%), ermB (25.9%), ermC (51.9%), erm33 (7.4%) as listed in Table 3. Additionally, of the 27 isolates, 1 (3.7%), 6 (22.2%) and 11 (40.7%) contained only ermA, ermB and ermC, respectively (Table 4). Finally, for resistant gene combinations including ermA+ermC, ermA+erm33, ermB+ermC and ermC+erm33, the ratios for the isolates each accounted for 3.7% (Table 4). These data manifested ermC was the major macrolide resistance determinant and multiple erm genes can be existed in one isolate. Meanwhile, there were 5 macrolide-resistant isolates which were found negative for erm and msrA genes (Table 2), revealing new unknown resistance determinants are responsible for the resistance of these isolates.

Table 3. Positive rates of resistant genes among 27 macrolide-resistant S. aureus isolates.

| Gene | S. aureus, % (n/27) | MSSA, % (n/21) | MRSA, % (n/6) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ermA | 11.1% (3/27) | 9.5 % (2/21) | 16.7 % (1/6) |

| ermB | 25.9% (7/27) | 33.3 % (7/21) | 0 % (0/6) |

| ermC | 51.9% (14/27) | 47.6 % (10/21) | 66.7 % (4/6) |

| erm33 | 7.4% (2/27) | 0 % (0/21) | 33.3 % (2/6) |

| msrA | 0 % (0/27) | 0 % (0/21) | 0 % (0/6) |

Table 4. Distribution of macrolide resistance genes among 27 macrolide-resistant S. aureus isolates.

| Macrolide-resistant genes | No. of isolates (%) |

|---|---|

| ermA alone | 1 (3.7%) |

| ermB alone | 6 (22.2%) |

| ermC alone | 11 (40.7%) |

| ermA+ermC | 1 (3.7%) |

| ermA+erm33 | 1 (3.7%) |

| ermB+ermC | 1 (3.7%) |

| ermC+erm33 | 1 (3.7%) |

Among 21 macrolide-resistant MSSA isolates, 2 (9.5%), 7 (33.3%) and 10 (47.6%) contained ermA, ermB and ermC, respectively; while in 6 MRSA isolates, 1 (16.7%), 4 (66.7%) and 2 (33.3%) contained ermA, ermC and erm33 (Table 2 and 3), respectively. Therefore, ermC was the predominant determinants in both MSSA and MRSA, and both ermA and ermC were more common among MRSA than MSSA. In addition, no erm33 or msrA was found in MSSA; no ermB or msrA existed in MRSA.

The only FA-resistant isolate we identified belongs to low level resistance. Therefore, we detected related genes responsible for low level resistance [9, 10], but found no resistance determinants fusB/C/D genes or fusE gene mutations in this isolate. In addition, we also examined fusA mutations which are responsible for high level resistance [8]. Our result demonstrated that these mutations did not exist in our resistant isolate either. This suggests there may exist other unknown resistant mechanisms responsible for FA resistance in S. aureus.

For mupirocin-resistant determinants, the genes mupA and mupB were traditionally associated with high level mupirocin resistance. Therefore, we first examined the existence of these two genes. However, our PCR result showed that these genes were not found in the 5 high level resistant isolates, which suggested that other determinants, rather than mupA and mupB, contributed to the resistance. In addition, we also examined the low level resistance gene ileS in these high level resistance isolates, and found all were positive to ileS mutation A637G (Table 2), which manifested the ileS gene mutations might be associated with the high level mupirocin resistance. Next, for low level mupirocin resistance, we first detected in the only low level resistant isolate (No. 038, Table 2) the ileS mutations G1762T and G1891T, which are essential for the low level mupirocin resistance [15]. However, these two mutations were not found in the isolate. We further detected mutations including A637G and A2412T, which are not significantly involved in low level mupirocin resistance [15]. We found only A637G in the isolate (Table 2). These results suggested that A637G may play a role in low level mupirocin resistance as well as in high level mupirocin resistance.

In summary, we have detected the existence of macrolide- and mupirocin-resistant genes and gene mutations in 23 of 28 antibiotic resistant isolates. These 23 isolates were defined as resistant gene-positive S. aureus. No FA-resistant genes were found in the only resistant isolate. Within the other 5 antibiotic resistant isolates, we identified no known resistant genes or gene mutations.

Molecular characteristics of resistant gene positive strains

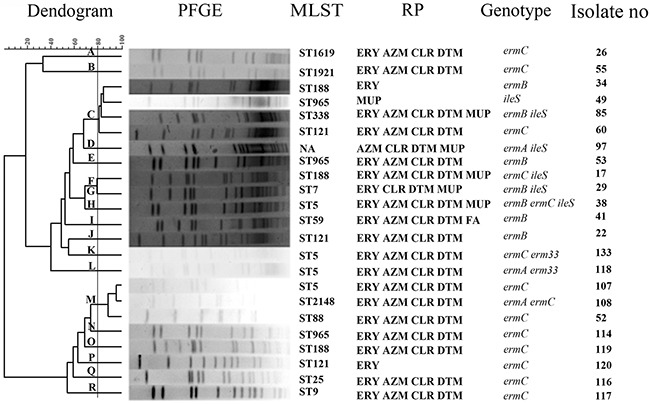

To study the homology of resistant gene positive S. aureus, the 23 isolates were molecularly typed by multilocus sequence typing (MLST). Except 1 isolate (no. 97) whose sequence type (ST) is novel and being prepared for submission and identification, the MLST results of the remaining 22 isolates can be divided into 13 different STs as listed in Figure 1. Among these STs, ST5 which was the most common ST existed in four isolates. ST188, ST965 and ST121 together appeared in each of 3 isolates. The remaining 9 STs were belonged to 9 different strains. The 21 macrolide-resistant gene positive isolates had all 13 STs (Figure 1). 4 of these isolates which mostly harbored ermC (3/4) belonged to ST5, followed by 3 contained ST188 and ST121, and 2 contained ST965. The remaining isolates had only single and diverse ST of other types. In addition, the only FA-resistant isolate belonged to ST59. Mupirocin-resistant isolates had 6 STs, with ST5 in the only low level resistant isolate and the rest 5 in high level resistant isolates. Next, pulsed field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) was utilized to further identify the 23 resistant gene positive isolates. Our result showed that PFGE patterns of the genomic DNA of these isolates were classified into 18 clusters (Figure 1). The isolates no. 34, 49, 85, 60 belonged to one cluster, and no. 107, 108, 52 to another cluster. Other isolates revealed the other 16 distinct clusters. In brief, the present study showed the STs and PFGE patterns of 23 resistant gene positive isolates were sporadic and heterogeneous, thus the phenomenon demonstrated antibiotic-resistant isolates existed diverse genetic backgrounds.

Figure 1. A dendrogram of MLST and PFGE.

The 23 genes-positive strains belonged to different 18 clusters from A to R. MLST, multilocus sequence typing; PFGE, pulsed field gel electrophoresis; RP, resistant phenotype; ERY, erythromycin; CLR, clarithromycin; AZM, azithromycin; DTM, dirithromycin; FA, fusidic acid; MUP, mupirocin; ST, sequence type; NA, not available.

DISCUSSION

Erythromycin was discovered several decades ago, it was often used due to the excellent tissue penetration and good oral absorption. With the use of new available macrolide derivatives in the 1980s, this group of antibiotics remains an important class of drugs for the treatment of a variety of community and hospital infectious diseases caused by Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria [2, 4]. As the other commonly used effective antimicrobials, FA and mupirocin are often used in the treatment of S. aureus infections, too. However, the resistance to macrolides, FA and mupirocin are rapidly increasing around the world.

In this study, the resistance rate of erythromycin (73.5%, Table 1) was higher than that in Belgium (37.4%) [20], Iran (42%) [21] and India (51.7%) [22], but lower than that in Korean (77.5%) [23] and Brazil (95.2%) [24]. Interestingly, compared with two previous reports (97.3% in MSSA, 98% in MRSA and 59.1% in S. aureus) [25, 26] surveyed in China, our study indicated different geographical regions and bacteria sources harbored diverse but increasing erythromycin resistant ratio. Of note, the overuse of erythromycin, which is often prescribed for impetigo therapy in China [27], may be the primary reason why the high level of resistance happened. Moreover, besides erythromycin, resistance to all the other tested macrolide antibiotics among MSSA isolates was significantly lower than that of MRSA isolates (Table 1), which was similar with early report [28]. These results also demonstrated that S. aureus co-holding macrolide resistance and virulence determinants in the hospitals would be prevalence.

Several high level resistant genes, such as erm genes, have been reported in S. aureus. It is notable that the predominance of these genes (i.g. ermA and ermC) was variable in several countries [4, 24, 29–31]. Here in China we found that, among the 27 macrolide-resistant S. aureus isolates, ermC was the most prevalent resistance determinant and ermA was less prevalent (51.9% vs 11.1%, Table 3).

Of note, the co-existence of ermA and ermC was found in 3.7% (1/27) isolates (Table 4), which was similar with the result from the literature in European countries (3%) [29], but different from that in Turkey (37.5%) [32]. Furthermore, we examined MIC values against macrolides in this S. aureus isolate co-harboring ermA and ermC, but found they were all relatively low. For this unexpected result, we speculate that the expression of erm genes would be in the control through ribosome stalling or riboswitch, which are general ways for antibiotic induction resistance [33, 34].

As FA has been licensed for decades in many countries [5], FA-resistant S. aureus emerged gradually and the recent resistance rates ranged from 1.4% to 52.5% in European countries [35], 7% in Canada and Australia [36] and <10% in most Asia countries and the United States [5, 36]. Here, among 34 S. aureus isolates investigated, we found only 1 FA-resistant isolate (2.9%, Table 1) with low level resistance. The low resistance rate is consistent with others [37, 38], except a study from Wenzhou with the extraordinarily high resistance rate of 14.3% [39]. The low FA-resistance rate and MIC value may be due to the clinical practice available in China since 1999, and as a topical cream since 2003 [27].

The only FA-resistant isolate revealed resistance to four macrolides with MIC each of 256 μg/ml (Table 2). Comparing to the high resistance ratio (79.4%, 27/34) of macrolides, this result showed FA was more effective than macrolides, and suggested macrolides may be inapplicable to deal with FA-resistant S. aureus. The other S. aureus isolates including 6 MRSA were all susceptible to FA (Table 1), which was in accordance with previous report that MRSA were sensitive to FA [25].

Similarly, since mupirocin was first introduced into clinic in 1985, there has appeared mupirocin-resistant S. aureus isolates in 1987 [40]. Afterwards, it has been increasingly reported the mupirocin-resistant S. aureus in many countries, such as UK 0.3% [41], Spain 11.3% [42], USA 13.2% [43], Belgium 3.6% [44], India 6% [45], Greece 4.4% [46], Korea 5% [47], Turkey 45% [48]. Additionally, previous studies indicated that the mupirocin resistance in China was ranging from 0 to 6.6% [27, 49–51]. However, the mupirocin-resistant S. aureus in our study was 17.6% (6/34, Table 1). The reason for rapidly increased resistance to mupirocin and its high MIC value may be its extensive use in China in recent years [25].

For mupirocin-resistant determinants, we checked both high level resistance genes mupA and mupB and low level resistance ileS gene mutations in all 6 resistant isolates. However, No mupA or mupB was found in high level resistant isolates. We could only identified ileS mutation A637G in both low level and high level resistant isolates (Table 2), suggesting there might exist the possibility that high level resistant strains evolve from low level resistant ones bearing A637G mutation. We also found other ileS mutations other than A637G in the only low level resistant isolate, but the connection between these mutants and the resistant phenotype awaits more investigation.

For cross-resistance profile in the mupirocin resistant isolates, we found that 4 high and 1 low level mupirocin-resistant isolates were resistant to multiple macrolides (Table 2), which indicated high and low level mupirocin-resistant S. aureus had no much difference in macrolides resistance. Interesting, all MRSA isolates were susceptible to mupirocin (Table 1), which were similar to the result of a previous report [52].

The antibiogram of S. aureus in our study demonstrated high resistance rate of macrolides and low resistance rate of FA and mupirocin, indicating macrolides are not appropriate agents any longer to treat infections caused by S.aureus, and the other two antibiotics remain an effective treatment. In addition, there was a trend of the occurrence of multiple resistance among S. aureus, thus further restrictions on the use of these antimicrobials are demanded to curtail the spread of antibiotics resistant S. aureus. For resistant mechanisms of these three antibiotics in our study, ermC was the major resistant determinant for macrolides resistance, and A637G of ileS for both high and low level mupirocin resistances. Other unknown resistant determinants are responsible for FA resistance. At present, we are sequencing the genome of this intriguing isolate, hoping to find novel FA-resistant determinants.

Among the 13 STs from 22 resistant gene positive strains ST5 was the most prevalent ST (18.2%, Figure 1), which is similar to the result of a previous study [39]. It has been reported ST59 of community-associated MRSA is mostly observed in Asia and the United States [53], but only one MSSA isolate in our specimens harbored ST59. We also found 2 MSSA and 1 MRSA isolates with ST121, which also indicated ST121 are mostly reported in MSSA than MRSA [25]. Additionally, ST121 isolates (13.6%, 3/22) were more prevalent than ST59 (4.5%, 1/22, Figure 1), which was in accordance with another investigation [25]. As reported in some Asia countries, ST239 or ST5 were the major STs among MRSA isolates [54–57]. In our study, ST5, but not ST239, was found in our MRSA isolates, suggesting MRSA distribution has considerable heterogeneity from different geographic areas.

It is worth noting that the 23 resistant gene positive isolates belonged to 18 clusters (Figure 1) and isolates with the same ST were attributed to different clusters. The highest similarity of 2 isolates in one cluster was no higher than 95.58% and the dissimilarity of two clusters was no lower than 33.31%. Traditionally, the isolates with the same phenotype and genotype show the same PFGE groups. While in our study, the same phenotype and genotype in antibiotics-resistant strains displayed diverse PFGE types. This phenomenon has also been reported previously [11]. In addition, ST5 (1-4-1-4-12-1-10) differs from ST965 (1-4-1-4-119-1-10) only in locus pta with one nucleotide difference due to a single recombination event, but these two STs were assigned to different clusters. Meanwhile, ST965 was found to be different in seven loci from ST338 (19-23-15-48-19-20-15), but they were assigned to one cluster. These findings suggest adaptation to varying environmental conditions occurs through microevolutionary changes within a single isolate [58, 59]. Notably, the 23 isolates with the similar resistance phenotype and genotype belonged to various STs and clusters, revealing the genetic relatedness among these isolates was weak and there was a high genetic heterogeneity. This heterogeneity further confirmed that monitoring of these antibiotics resistance among S. aureus should be strengthened.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial isolates

A total of 34 nonduplicate S. aureus isolates including 6 (MRSA) were collected from clinical specimens of Lishui Central Hospital in Zhejiang province, China, between February 2010 and November 2011. These specimens came from tissues including blood, urine, sputum, wound exudates and abscess. All the isolates were identified by detecting the existence of the housekeeping gene arcc [60].

MRSA identification

To identify MRSA isolates, a simplex PCR was used for the detection of mecA (Table 5) [61]. PCR products were sequenced by TSINGKE (Chengdu, China) and then confirmed by aligning to sequence of mecA gene of MRSA with NCBI Nucleotide Blast.

Table 5. Primers used in this study.

| Gene | Primer | Primer sequence(5’ to 3’) | Amplicon size(bp) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mecA |

mecA-F mecA-R |

5’-TCCAGATTACAACTTCACCAGG-3’ 5’-CCACTTCATATCTTGTAACG-3’ |

162 | [61] |

| IleS1 |

IleS1-F Iles1-R |

5’-ATTTCCCAATGCGAGGTGGT-3’ 5’-CGTGACCTGGTGCTGTATGT-3’ |

954 | This study |

|

IleS2-F IleS2-R |

5’-TCTGGTTCATCACACCGTGG-3’ 5’-GCACGGTTCACATCATCACG-3’ |

842 | This study | |

|

IleS3-F IleS3-R |

5’-ACGTGATGATGTGAACCGTG-3’ 5’-TTGTTGGCATCGTGGGCATA-3’ |

322 | This study | |

| mupA |

mupA-F mupA-R |

5’-CATTGGAAGATGAAATGCATACC-3’ 5’-CGCAGTCATTATCTTCACTGAG-3’ |

443 | [18, 71] |

|

mupA-up mupA-dn |

5’-TATATTATGCGATGGAAGGTTGG-3’ 5’-AATAAAATCAGCTGGAAAGTGTTG-3’ |

457 | ||

| mupB |

mupB-F mupB-R |

5’-CTAGAAGTCGATTTTGGAGTAG-3’ 5’-AGTGTCTAAAATGATAAGACGATC-3’ |

674 | [18] |

| fusA |

fusA1-F fusA1-R |

5’-ACGATGGAAGATCGTTTAGC-3’ 5’-TGGTCAGCTTTAGATTTTGGC-3’ |

1510 | This study |

|

fusA2-F fusA2-R |

5’-AGGTACAATGACATCTGGTTC-3’ 5’-TCTCTCATGATAGTTTCTCACC-3’ |

1259 | This study | |

| fusB |

fusB-F fusB-R |

5’-ATTCAATCGGAAACCTATAATGATA-3’ 5’-TTATATATTTCCGATTTGATGCAAG-3’ |

292 | [67] |

| fusC |

fusC-F fusC-R |

5’-TCTCGGACTTTATTACATCG-3’ 5’-TGAGAAAGAGTGATGTATCAG-3’ |

348 | This study |

| fusD |

fusD-F fusD-R |

5’-AATTCGGTCAACGATCCC-3’ 5’-GCCATCATTGCCAGTACG-3’ |

465 | [39] |

| fusE |

fusE-F fusE-R |

5’- TGTTGGTGGAGAAATTATCGC-3’ 5’- CCTGATAAGTTAGTACGAACACG-3’ |

696 | This study |

| ermA |

ermA-F ermA-R |

5’-TCTAAAAAGCATGTAAAAGAA-3’ 5’-CTTCGATAGTTTATTAATATTAGT-3’ |

645 | [66] |

| ermB |

ermB-F ermB-R |

5’-GAAAAGGATCTCAACCAAATA-3’ 5’-AGTAACGGTACTTAAATTGTTTAC-3’ |

639 | [66] |

| ermC |

ermC-F ermC-R |

5’-TCAAAACATAATATAGATAAA-3’ 5’-GCTAATATTGTTTAAATCGTCAAT-3’ |

642 | [66] |

| erm33 |

erm33-F erm33-R |

5’-TCTGCAACGAGCTTTGGGTT-3’ 5’-TCAAAGCCTGTCGGAATTGGT-3’ |

239 | This study |

| msrA |

msrA-F msrA-R |

5’-TCCAATCATTGCACAAAATC-3’ 5’-AATTCCCTCTATTTGGTGGT-3’ |

163 | [4] |

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

The MICs of 34 S. aureus to erythromycin, clarithromycin, azithromycin, dirithromycin, mupirocin (all from Sangon, Shanghai, China) and FA (Adamas-beta, China) were determined by agar dilution method, according to the 2010 guidelines provided by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institutes (CLSI), and S. aureus strains ATCC29213 for macrolides & fusidic acid and ATCC25923 for mupirocin were taken as control [25, 62]. The MICs value used to indicate erythromycin, clarithromycin, azithromycin and dirithromycin resistance are ≥ 8 μg/ml in accordance with CLSI. For FA resistance, MIC thresholds of 2 to 64 μg/ml indicate low level resistance, and ≥ 128 μg/ml high level resistance [63, 64]. For mupirocin resistance, low level resistance is from 8 to 256 μg/ml and high level mupirocin resistance ≥ 512 μg/ml [65].

DNA extraction

For 28 antibiotic-resistant S. aureus strains, each was cultured overnight on a Mueller-Hinton agar plate at 37°C. Then, a single bacterial colony was suspended in 1 ml sterile LB medium, and subsequently incubated at 37°C with vigorous shaking for 6 hours, followed by centrifugation at 13000 × g for 2 minutes. Next, the culture media was discarded, and the pellet was mixed with 100 μl of Tris-HCl (200 mM, pH 8.0) and 2μl of lysostaphin (1 mg/100 μl, Sangon, Shanghai, China). Finally, each sample was heated at 37°C for 1 hour, followed by 95°C for 15 minutes, and centrifuged at 13000 × g for 2 minutes. Supernatant containing genomic DNA was collected and used as template for the PCR assays.

PCR amplification and DNA sequencing

Antibiotic-resistant S. aureus strains were used by PCR to detect resistance determinants as listed in Table 5 [2, 4, 18, 36, 39, 47, 66, 67]. PCR was carried out according to previous studies [47, 66, 68]. Early reports on fusA and ileS gene mutations were also included in our study for PCR detection [14, 15, 64, 67–70]. In order to clearly ascertain the position of putative mutations in these two genes, we divided the entire fusA gene into fusA1 and fusA2 fragments, and ileS gene into ileS1, ileS2 and ileS3 fragments according to a previous report [11]. For mupA detection, two pairs of mupA primers were used in the PCR reaction (Table 5) [18, 71]. PCR products were sequenced by TSINGKE and then confirmed by sequence comparison to corresponding genes in the Nucleotide sequence database of NCBI.

Molecular typing of resistant gene-positive strains

The genetic relatedness among 23 resistant gene-positive S. aureus strains was typed by MLST and PFGE. According to the MLST database (http://saureus.mlst.net), seven housekeeping genes (arcc, aroe, glpf, gmk, pta, tpi and yqil) were amplified and sequenced for the determination of ST. Novel ST of DNA sequence was verified and deposited in Staphylococcus aureus MLST Databases (https://pubmlst.org/saureus/). PFGE typing was conducted by a modification of the protocol previously described [72, 73]. The homology of these strains was analyzed with BioNumerics software (Applied Maths). Strains with >80% similarity were assigned to the same PFGE clusters [74].

CONCLUSION

This study indicates macrolides, especially erythromycin, are not appropriate agents any longer to treat skin infections caused by S. aureus; the gene ermC was the predominant determinant for macrolides resistance among S. aureus; mupirocin and FA remain effective drug candidates for the eradication of S. aureus; A637G mutation in ileS gene may result in low and high level mupirocin resistance. Additionally, the heterogeneity among 23 resistant gene positive strains supports the tendency for the continued dissemination of macrolides, FA and mupirocin resistance in S. aureus, and thus suggests the resistance of S. aureus to these antimicrobials should be continuously supervised and adequate infection control measures against these antibiotics-resistant isolates should be established.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS FIGURE

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare that there are no competing interests regarding the publication of this paper.

FUNDING

This work was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grants 31470246, 3160016 and 31300659), Scientific Research and Innovation Team of Sichuan Province (grant 15TD0025), Preeminent Youth Fund of Sichuan Province (grant 2015JQO019) and Huiming Project of Chengdu Science and Technology Bureau (grant 2015-HM01-00543-SF).

REFERENCES

- 1.Whitby M, McLaws ML, Berry G. Risk of death from methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia: a meta-analysis. Med J Aust. 2001;175:264–267. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2001.tb143562.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roberts MC. Update on macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin, ketolide, and oxazolidinone resistance genes. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2008;282:147–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01145.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kirst HA. Introduction to the macrolide antibiotics. In: Schönfeld W, Kirst HA, editors. Macrolide Antibiotics. Basel: Birkhäuser Basel; 2002. pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moosavian M, Shoja S, Rostami S, Torabipour M, Farshadzadeh Z. Inducible clindamycin resistance in clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus due to erm genes, Iran. Iran J Microbiol. 2014;6:421–427. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang JL, Tang HJ, Hsieh PH, Chiu FY, Chen YH, Chang MC, Huang CT, Liu CP, Lau YJ, Hwang KP, Ko WC, Wang CT, Liu CY, et al. Fusidic acid for the treatment of bone and joint infections caused by meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2012;40:103–107. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2012.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Girolomoni G, Mattina R, Manfredini S, Vertuani S, Fabrizi G. Fusidic acid betamethasone lipid cream. Int J Clin Pract. 2016;70:4–13. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ellington MJ, Reuter S, Harris SR, Holden MT, Cartwright EJ, Greaves D, Gerver SM, Hope R, Brown NM, Torok ME, Parkhill J, Koser CU, Peacock SJ. Emergent and evolving antimicrobial resistance cassettes in community-associated fusidic acid and meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2015;45:477–484. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2015.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farrell DJ, Castanheira M, Chopra I. Characterization of global patterns and the genetics of fusidic acid resistance. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:S487–492. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hung WC, Chen HJ, Lin YT, Tsai JC, Chen CW, Lu HH, Tseng SP, Jheng YY, Leong KH, Teng LJ. Skin commensal staphylococci may act as reservoir for fusidic acid resistance genes. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0143106. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Norstrom T, Lannergard J, Hughes D. Genetic and phenotypic identification of fusidic acid-resistant mutants with the small-colony-variant phenotype in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51:4438–4446. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00328-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang JA, Park DW, Sohn JW, Yang IS, Kim KH, Kim MJ. Molecular analysis of isoleucyl-tRNA synthetase mutations in clinical isolates of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus with low-level mupirocin resistance. J Korean Med Sci. 2006;21:827–832. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2006.21.5.827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shittu AO, Udo EE, Lin J. Phenotypic and molecular characterization of Staphylococcus aureus isolates expressing low- and high-level mupirocin resistance in Nigeria and South Africa. BMC Infect Dis. 2009;9:10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-9-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sanju AJ, Kopula SS, Palraj KK. Screening for mupirocin resistance in staphylococcus. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9:DC09–10. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2015/15230.6678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Antonio M, McFerran N, Pallen MJ. Mutations affecting the rossman fold of isoleucyl-tRNA synthetase are correlated with low-level mupirocin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46:438–442. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.2.438-442.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fujimura S, Tokue Y, Watanabe A. Isoleucyl-tRNA synthetase mutations in Staphylococcus aureus clinical isolates and in vitro selection of low-level mupirocin-resistant strains. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:3373–3374. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.10.3373-3374.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Patel JB, Gorwitz RJ, Jernigan JA. Mupirocin resistance. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:935–941. doi: 10.1086/605495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Udo EE, Jacob LE, Mathew B. Genetic analysis of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus expressing high- and low-level mupirocin resistance. J Med Microbiol. 2001;50:909–915. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-50-10-909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seah C, Alexander DC, Louie L, Simor A, Low DE, Longtin J, Melano RG. MupB, a new high-level mupirocin resistance mechanism in Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2012;56:1916–1920. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05325-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jung MY, Chung JY, Lee HY, Park J, Lee DY, Yang JM. Antibiotic susceptibility of Staphylococcus aureus in atopic dermatitis: current prevalence of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Korea and treatment strategies. Ann Dermatol. 2015;27:398–403. doi: 10.5021/ad.2015.27.4.398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vandendriessche S, Kadlec K, Schwarz S, Denis O. Methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus ST398-t571 harbouring the macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B resistance gene erm(T) in Belgian hospitals. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:2455–2459. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Farhadian A, Nejad QB, Peerayeh SN, Rahbar M, Vaziri F. Determination of vancomycin and methicillin resistance in clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus in Iranian hospitals. Brit Microbiol Res J. 2014;4:454–461. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lyall KD, Gupta V, Chhina D. Inducible clindamycin resistance among clinical isolates of Staphylococcus aureus. J Mahatma Gandhi Inst Med Sci. 2013;18:112–115. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jung YH, Kim KW, Lee KM, Yoo JI, Chung GT, Kim BS, Kwak HS, Lee YS. Prevalence and characterization of macrolide-lincomycin-streptogramin B-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Korean hospitals. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;61:458–460. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkm483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gushiken CY, Medeiros LB, Correia BP, Souza JM, Moris DV, Pereira VC, Giuffrida R, Rodrigues MV. Nasal carriage of resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a medical student community. An Acad Bras Cienc. 2016;88:1501–1509. doi: 10.1590/0001-3765201620160123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu Y, Xu Z, Yang Z, Sun J, Ma L. Characterization of community-associated Staphylococcus aureus from skin and soft-tissue infections: a multicenter study in China. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2016;5:e127. doi: 10.1038/emi.2016.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun H, Chen L, Chen X, Jia X, Li N, Liu W, Tong H, Xiang R, Zhang F, Zhao H, Zhang J, Xu Y. [Antimicrobial susceptibility of community-acquired respiratory tract pathogens isolated from class B hospitals in China during 2013 and 2014]. [Article in Chinese] Zhonghua Jie He He Hu Xi Za Zhi. 2016;39:30–37. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1001-0939.2016.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu Y, Kong F, Zhang X, Brown M, Ma L, Yang Y. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from children with impetigo in China from 2003 to 2007 shows community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus to be uncommon and heterogeneous. Brit J Dermatol. 2009;161:1347–1350. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09376.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Baek YS, Jeon J, Ahn JW, Song HJ. Antimicrobial resistance of Staphylococcus aureus isolated from skin infections and its implications in various clinical conditions in Korea. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:e191–197. doi: 10.1111/ijd.13046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schmitz FJ, Sadurski R, Kray A, Boos M, Geisel R, Kohrer K, Verhoef J, Fluit AC. Prevalence of macrolide-resistance genes in Staphylococcus aureus and Enterococcus faecium isolates from 24 European university hospitals. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2000;45:891–894. doi: 10.1093/jac/45.6.891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spiliopoulou I, Petinaki E, Papandreou P, Dimitracopoulos G. erm(C) is the predominant genetic determinant for the expression of resistance to macrolides among methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clinical isolates in Greece. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2004;53:814–817. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkh197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martineau F, Picard FJ, Lansac N, Menard C, Roy PH, Ouellette M, Bergeron MG. Correlation between the resistance genotype determined by multiplex PCR assays and the antibiotic susceptibility patterns of Staphylococcus aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:231–238. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.2.231-238.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aktas Z, Aridogan A, Kayacan CB, Aydin D. Resistance to macrolide, lincosamide and streptogramin antibiotics in staphylococci isolated in Istanbul, Turkey. J Microbiol. 2007;45:286–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jia X, Zhang J, Sun W, He W, Jiang H, Chen D, Murchie AI. Riboswitch control of aminoglycoside antibiotic resistance. Cell. 2013;152:68–81. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jia X, Zhang J, Sun W, He W, Jiang H, Chen D, Murchie AI. Riboswitch regulation of aminoglycoside resistance acetyl and adenyl transferases. Cell. 2013;153:1419–1420. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Castanheira M, Watters AA, Mendes RE, Farrell DJ, Jones RN. Occurrence and molecular characterization of fusidic acid resistance mechanisms among Staphylococcus spp. from European countries (2008) J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65:1353–1358. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Castanheira M, Watters AA, Bell JM, Turnidge JD, Jones RN. Fusidic acid resistance rates and prevalence of resistance mechanisms among Staphylococcus spp. isolated in North America and Australia, 2007-2008. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:3614–3617. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01390-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang J, Ye M, Ding H, Guo Q, Ding B, Wang M. Prevalence of fusB in Staphylococcus aureus clinical isolates. J Med Microbiol. 2013;62:1199–1203. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.058305-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liu Y, Geng W, Yang Y, Wang C, Zheng Y, Shang Y, Wu D, Li X, Wang L, Yu S, Yao K, Shen X. Susceptibility to and resistance determinants of fusidic acid in Staphylococcus aureus isolated from Chinese children with skin and soft tissue infections. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2012;64:212–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2011.00887.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yu F, Liu Y, Lu C, Lv J, Qi X, Ding Y, Li D, Huang X, Hu L, Wang L. Dissemination of fusidic acid resistance among Staphylococcus aureus clinical isolates. BMC microbiology. 2015;15:210. doi: 10.1186/s12866-015-0552-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rahman M, Nobel W, Cookson B, Baird D, Coia J. Mupirocin-resistant staphylococcus aureus. Lancet. 1987;330:2. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cookson BD, Lacey RW, Noble WC, Reeves DS, Wise R, Redhead RJ. Mupirocin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet. 1990;335:1095–1096. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)92667-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Daskalaki M, Otero JR, Chaves F. Molecular characterization of resistance to mupirocin in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates in a tertiary hospital in Spain. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;63:826–828. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jones JC, Rogers TJ, Brookmeyer P, Dunne WM, Jr, Storch GA, Coopersmith CM, Fraser VJ, Warren DK. Mupirocin resistance in patients colonized with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a surgical intensive care unit. Clinical Infect Dis. 2007;45:541–547. doi: 10.1086/520663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nagant C, Deplano A, Nonhoff C, De Mendonca R, Roisin S, Dodemont M, Denis O. Low prevalence of mupirocin resistance in Belgian Staphylococcus aureus isolates collected during a 10 year nationwide surveillance. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016;71:266–267. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkv286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gadepalli R, Dhawan B, Mohanty S, Kapil A, Das BK, Chaudhry R, Samantaray JC. Mupirocin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus in an Indian hospital. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2007;58:125–127. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2006.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Legakis NJ, Tzouvelekis LS, Maniatis N, Agel A. Mupirocin resistance in Staphylococcus aureus from Greek hospitals. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2001;18:407–408. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(01)00429-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yun HJ, Lee SW, Yoon GM, Kim SY, Choi S, Lee YS, Choi EC, Kim S. Prevalence and mechanisms of low- and high-level mupirocin resistance in staphylococci isolated from a Korean hospital. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003;51:619–623. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkg140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sareyyupoglu B, Ozyurt M, Haznedaroglu T, Ardic N. Detection of methicillin and mupirocin resistance in staphylococcal hospital isolates with a touchdown multiplex polymerase chain reaction. Folia Microbiol (Praha) 2008;53:363–367. doi: 10.1007/s12223-008-0056-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang L, Liu Y, Yang Y, Huang G, Wang C, Deng L, Zheng Y, Fu Z, Li C, Shang Y, Zhao C, Sun M, Li X, et al. Multidrug-resistant clones of community-associated meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolated from Chinese children and the resistance genes to clindamycin and mupirocin. J Med Microbiol. 2012;61:1240–1247. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.042663-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gu FF, Han LZ, Chen X, Wang YC, Shen H, Wang JQ, Tang J, Zhang J, Ni YX. Molecular characterization of Staphylococcus aureus from surgical site infections in orthopedic patients in an orthopedic trauma clinical medical center in Shanghai. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2015;16:97–104. doi: 10.1089/sur.2014.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu QZ, Wu Q, Zhang YB, Liu MN, Hu FP, Xu XG, Zhu DM, Ni YX. Prevalence of clinical meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) with high-level mupirocin resistance in Shanghai and Wenzhou, China. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2010;35:114–118. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2009.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kali A, Stephen S, Umadevi S, Kumar S, Joseph NM, Srirangaraj S. Changing trends in resistance pattern of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7:1979–1982. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2013/6142.3377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Deurenberg RH, Stobberingh EE. The evolution of Staphylococcus aureus. Infect Genet Evol. 2008;8:747–763. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yu F, Chen Z, Liu C, Zhang X, Lin X, Chi S, Zhou T, Chen Z, Chen X. Prevalence of Staphylococcus aureus carrying Panton-Valentine leukocidin genes among isolates from hospitalised patients in China. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2008;14:381–384. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yao D, Yu FY, Qin ZQ, Chen C, He SS, Chen ZQ, Zhang XQ, Wang LX. Molecular characterization of Staphylococcus aureus isolates causing skin and soft tissue infections. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:133. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-10-133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Liu Y, Wang H, Du N, Shen E, Chen H, Niu J, Ye H, Chen M. Molecular evidence for spread of two major methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clones with a unique geographic distribution in Chinese hospitals. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:512–518. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00804-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Liu Q, Han L, Li B, Sun J, Ni Y. Virulence characteristic and MLST-agr genetic background of high-level mupirocin-resistant, MRSA isolates from Shanghai and Wenzhou, China. PLoS One. 2012;7:e37005. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0037005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Paluchowska P, Tokarczyk M, Bogusz B, Skiba I, Budak A. Molecular epidemiology of Candida albicans and Candida glabrata strains isolated from intensive care unit patients in Poland. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2014;109:436–441. doi: 10.1590/0074-0276140099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bonfim-Mendonca Pde S, Fiorini A, Shinobu-Mesquita CS, Baeza LC, Fernandez MA, Svidzinski TI. Molecular typing of Candida albicans isolates from hospitalized patients. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2013;55:385–391. doi: 10.1590/S0036-46652013000600003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lim KT, Teh CS, Thong KL. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification assay for the rapid detection of Staphylococcus aureus. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:895816. doi: 10.1155/2013/895816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wu MT, Burnham CA. Evaluation of oxacillin and cefoxitin disk and MIC breakpoints for prediction of methicillin resistance in human and isolates of Staphylococcus intermedius group. 2016;54:535–542. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02864-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Oommen SK, Appalaraju B, Jinsha K. Mupirocin resistance in clinical isolates of staphylococci in a tertiary care centre in south India. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2010;28:372–375. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.71825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Park SH, Kim JK, Park K. In vitro antimicrobial activities of fusidic acid and retapamulin against mupirocin- and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Ann Dermatol. 2015;27:551–556. doi: 10.5021/ad.2015.27.5.551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chen CM, Huang M, Chen HF, Ke SC, Li CR, Wang JH, Wu LT. Fusidic acid resistance among clinical isolates of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a Taiwanese hospital. BMC Microbiol. 2011;11:98. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-11-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Eltringham I. Mupirocin resistance and methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) J Hosp Infect. 1997;35:1–8. doi: 10.1016/s0195-6701(97)90162-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sun DD, Ma XX, Hu J, Tian Y, Pang L, Shang H, Cui LZ. Epidemiological and molecular characterization of community and hospital acquired Staphylococcus aureus strains prevailing in Shenyang, Northeastern China. Braz J Infect Dis. 2013;17:682–690. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2013.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.O’Neill AJ, Larsen AR, Henriksen AS, Chopra I. A fusidic acid-resistant epidemic strain of Staphylococcus aureus carries the fusB determinant, whereas fusA mutations are prevalent in other resistant isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:3594–3597. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.9.3594-3597.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chen HJ, Hung WC, Tseng SP, Tsai JC, Hsueh PR, Teng LJ. Fusidic acid resistance determinants in Staphylococcus aureus clinical isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54:4985–4991. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00523-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.den Heijer CD, van Bijnen EM, Paget WJ, Stobberingh EE. Fusidic acid resistance in Staphylococcus aureus nasal carriage strains in nine European countries. Future Microbiol. 2014;9:737–745. doi: 10.2217/fmb.14.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lim KT, Teh CS, Yusof MY, Thong KL. Mutations in rpoB and fusA cause resistance to rifampicin and fusidic acid in methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus strains from a tertiary hospital in Malaysia. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2014;108:112–118. doi: 10.1093/trstmh/trt111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Li T, Song Y, Zhu Y, Du X, Li M. Current status of Staphylococcus aureus infection in a central teaching hospital in Shanghai, China. BMC Microbiol. 2013;13:153. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-13-153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.McDougal LK, Steward CD, Killgore GE, Chaitram JM, McAllister SK, Tenover FC. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis typing of oxacillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates from the United States: establishing a national database. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:5113–5120. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.11.5113-5120.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bannerman TL, Hancock GA, Tenover FC, Miller JM. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis as a replacement for bacteriophage typing of Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:551–555. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.3.551-555.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Carrico JA, Pinto FR, Simas C, Nunes S, Sousa NG, Frazao N, de Lencastre H, Almeida JS. Assessment of band-based similarity coefficients for automatic type and subtype classification of microbial isolates analyzed by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:5483–5490. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.11.5483-5490.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.