Abstract

Background

Primary care guidelines for managing adult overweight/obesity recommend routine measurement of body mass index (BMI) and the offer of weight management interventions. Many studies state that this is rarely done, but the extent to which overweight/obesity is recognised, considered, and documented in routine care has not been determined.

Aim

To identify the epidemiology of adult overweight documentation and management by UK GPs.

Design and setting

A systematic review of studies since 2006 from eight electronic databases and grey literature.

Method

Included studies measured the proportion of adult patients with documented BMI or weight loss intervention offers in routine primary care in the UK. A narrative synthesis reports the prevalence and pattern of the outcomes.

Results

In total, 2845 articles were identified, and seven were included; four with UK-wide data and three with regional-level data. The proportion of patients with a documented BMI was 58–79% (28–37% within a year). For overweight/obese patients alone, 43–52% had a recent BMI record, and 15–42% had a documented intervention offer. BMI documentation was positively associated with older age, female sex, higher BMI, coexistent chronic disease, and higher deprivation.

Conclusion

BMI is under-recorded and weight loss interventions are under-referred for primary care adult patients in the UK despite the obesity register in the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF). The review identified likely underserved groups such as younger males and otherwise healthy overweight/obese individuals to whom attention should now be directed. The proposed amendment to the obesity register QOF could prompt improvements but has not been adopted for 2017.

Keywords: body mass index, general practice, obesity, primary health care, weight recording

INTRODUCTION

Most obese and overweight people in the UK state that they actively want to lose weight and would welcome advice from their doctor, but only 42% of obese adults report ever having received weight management advice from a healthcare professional.1,2 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines recommend routine identification of obesity in primary care including the use of body mass index (BMI) as a practical estimate of adiposity in adults.3,4 Around three-quarters of patients see their GP at least once a year and obese individuals are proportionately higher users of care.5

There is evidence that doctors are inaccurate when asked to estimate the weight of patients6–10 or even when taking anthropometric measurements that should be objective.11 In a UK study requiring GPs to estimate patients’ BMI from photos, all underestimated and estimations worsened as patient BMI increased.12 Although lack of recognition may play a role in under-documentation of BMI, some studies report lower rates of documentation than rates of self-report of weight discussion or diagnosis in a given consultation.13,14 Lack of documentation does not necessarily mean lack of recognition, but may reflect lack of weight prioritisation or intent to offer management. The documentation of a diagnosis of overweight or obesity itself in the patient’s record is important as it is associated with the patient’s receipt of interventions and weight management.15,16 GP intervention for weight management has been shown to be effective and acceptable to patients even when it is extremely brief.17

The QOF (Quality and Outcomes Framework) is a voluntary incentive programme that financially rewards GP practices in England for provision of ‘quality care’ with points assigned for performance against various indicators. In the 2015–2016 QOF, all practices in England received the points available for the stated QOF of ‘establishing and maintaining a register of patients aged ≥18 years who have a recorded BMI of ≥30 within the previous 12 months’.18 The registers indicated an adult obesity prevalence of 9.5%. In contrast, the most recent (2014) Health Survey for England survey showed a considerable discrepancy, with 24% of males and 27% of females aged >16 years being obese. Some of this difference can be accounted for by any patient not having been seen in the previous 12 months being omitted from the register, but as obese patients require more health services — 74% have a comorbidity and at least three-quarters of the whole population see their GP each year5,19 — it is likely that the difference cannot be accounted for by this alone. As it has not been determined how complete and accurate each obesity register is, the register data are limited in gauging GPs’ success in identifying and recording their patients’ BMI. NICE proposed an additional obesity QOF indicator: ‘The percentage of patients aged 18 or over … who have had a record of a BMI being calculated in the preceding 5 years (and after their 18th birthday)’, but this has not been adopted in 2017.20 QOF has an uncertain future; already abandoned by Scotland, there are suggestions that England may follow suit.21

How this fits in

Adult overweight/obesity documentation or management by UK GPs has not been objectively quantified. This systematic review shows that around half of overweight/obese patients had a recent body mass index (BMI) record. The proportion of patients with a documented offer of weight loss intervention varied widely from 15% to 42%. The proposed Quality and Outcomes Framework indicator of ‘patients aged 18 or over … who have had a record of a BMI being calculated in the preceding 5 years’ could prompt improvements.

Many qualitative studies have been published highlighting the numerous barriers and difficulties that GPs feel they face in tackling obesity in primary care, including raising the issue with patients.22,23 There is, however, no clear source of quantitative data on the decisions taken by GPs faced with an overweight/obese patient in routine appointments, nor for the proportion and type of overweight/obese patients who are identified and documented as such.

In recognition of this gap in knowledge, this systematic review aimed to identify, collate, report, and interpret the available quantitative data on documentation of adult overweight and obesity by GPs in the UK.

METHOD

Search strategy

A systematic search using a predefined search protocol (available from authors on request) was carried out in June 2016. The following databases were searched: MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL Plus, ASSIA, HMIC, BNI, Cochrane Library, and the Index to Theses. Limits were placed on all searches to English-language articles and to exclude articles published before 2006, in recognition of the introduction of the obesity register QOF.

All retrieved studies were saved to RefWorks reference manager software. Duplicates were removed. One author screened the titles, abstracts, and full text of articles to determine inclusion. A second author screened a random subset of 10% of the articles at each stage with discussion over any discrepancies. An inter-rater reliability score was calculated using Cohen’s κ.

The secondary sources comprised hand searching of the reference lists and citations of key papers found in databases, and e-mail communication with key authors to request details of any further studies meeting the inclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria

To be eligible for inclusion, the studies had to report quantitative data on an objective measure of GPs’ documentation of routine recording/discussion/diagnosis of BMI/weight/lifestyle advice/offering of weight loss intervention as a main outcome. Studies had to be set in primary care in the UK and the subjects were adults (aged ≥16 years). Studies reporting on only a narrow group of patients (for example, patients with diabetes) or on a specialised setting (for example, a weight management clinic) were not eligible for inclusion.

Critical appraisal and data extraction

A bespoke critical appraisal tool (Table 1) that incorporated all important aspects of study quality, irrespective of the mix of study designs to allow improved comparability between studies, was piloted and then applied to each paper by two authors individually. The quality assessment tool developed here is based on methodology used in other reviews,24–26 and the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) recommended checklists for each different study type where available, in particular the Newcastle–Ottawa scale for cohort and case control studies.27 For cross-sectional studies the Joanna Briggs Institute tool for appraisal of analytical cross-sectional studies28 and questions adapted from Guyatt et al’s publications on descriptive and cross-sectional studies were used for guidance.29,30

Table 1.

Summary of quality assessment tool results

| Lead author | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Artac34 | Bhaskaran35 | Booth32 | Booth31 | Dalton36 | Goodfellow37 | Osborn33 | |

|

| |||||||

| Year of publication | 2013 | 2013 | 2015 | 2013 | 2011 | 2016 | 2011 |

|

| |||||||

| Rationale and aim clear? | × | × | × | × | × | × | × |

|

| |||||||

| Appropriate study design? | × | × | × | × | × | × | × |

|

| |||||||

| Baseline demographics of subjects given? | × | × | × | × | × | × | |

|

| |||||||

| Population choice, representative of: | |||||||

| UK primary care patients nationally | × | ||||||

| UK primary care patients in a local area | |||||||

| A specific group | × | × | × | × | × | × | |

| Not specified | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Predefined sampling frame? | × | × | × | × | × | × | × |

|

| |||||||

| Sampling type: | |||||||

| Census/100% sample | × | × | |||||

| Random | × | × | × | × | |||

| Systematic | × | ||||||

| Convenience | |||||||

| Not specified | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Setting and location of recruitment identified? | × | × | × | × | × | × | × |

|

| |||||||

| Applied equally to all subjects? | × | × | × | × | × | × | |

|

| |||||||

| Validated/standardised extraction technique? | × | × | × | ||||

|

| |||||||

| Data from quality-controlled database of secure records? | × | × | × | × | × | × | × |

|

| |||||||

| Time period included clear (post-QOF data identified)? | × | × | × | × | × | × | × |

|

| |||||||

| Clearly defined outcome measures, for example, BMI-defined obesity | × | × | × | × | × | × | |

|

| |||||||

| Primary outcome was BMI or calculable BMI record | × | × | × | × | × | ||

|

| |||||||

| Medical codes/other documentation included | × | × | × | × | |||

|

| |||||||

| Predictive factors, for example, age, sex, practice detailed | × | × | × | × | × | × | × |

|

| |||||||

| Statistical methods used appropriately | × | × | × | × | × | × | × |

|

| |||||||

| Results presented clearly (sufficient data presented) | × | × | × | × | × | ||

|

| |||||||

| Interpretation takes into account sources of bias/imprecision (exclusions, missing data) | × | × | × | × | × | × | × |

|

| |||||||

| Interpretation is made in the context of current evidence | × | × | × | × | × | × | × |

|

| |||||||

| Generalisability of results: | |||||||

| All UK adults | |||||||

| All UK primary care adult patients | × | × | |||||

| All overweight/obese UK primary care patients | × | × | × | ||||

| Patients in a local region | × | × | |||||

| Not clear to whom generalisable | |||||||

BMI = body mass index. QOF = Quality and Outcomes Framwork. × = yes.

A narrative synthesis was prepared for the papers that met the exclusion and inclusion criteria. Emphasis was placed on interpreting and presenting the heterogeneity between studies and the individual risk of bias present for each outcome measure.

RESULTS

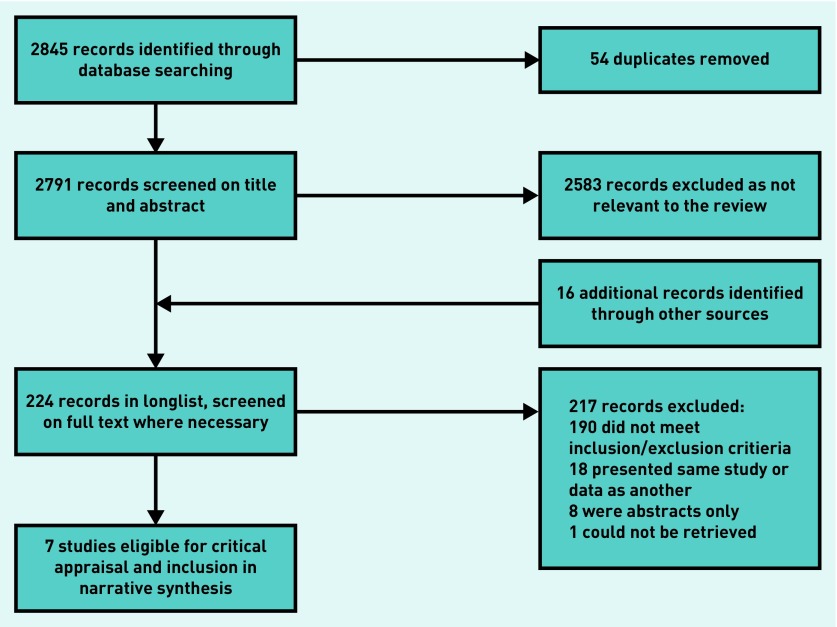

The search strategy returned 2845 results through searches of the electronic databases, 208 of which were retained after screening the titles and abstracts for relevance to the review and removal of duplicate results (Figure 1). A further 16 results from additional sources, from hand searches of reference lists and citations of key papers, were identified and subjected to further screening for suitability. Responses were received from four of the key authors, whose guidance had been requested by e-mail on any further studies suitable for inclusion in the review. No further studies were identified. Full-text versions of the papers were retrieved at this stage. Seven studies met the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of selection process.

The Cohen’s κ was 1.00 for agreement between the two authors at both the title screening and full-text stages.

Of the seven studies that were included in the review (Table 2): three31–33 were retrospective cohort studies based on large primary care databases, three34–36 were cross-sectional/descriptive in design using data from a primary care database or regional GP practice patient records, and the final study37 was a cluster randomised controlled trial within a further region of GP practices. The quality assessment tool allows visual comparison of the areas of difference and similarity in quality across the papers (Table 2). Table 3 presents the results of the outcome measures for each study.

Table 2.

Studies meeting inclusion and exclusion criteriaa

| Study | Primary care subjectsb | Study’s design and relevance |

|---|---|---|

|

Artac, 201334 Evaluation of a National Cardiovascular Risk Assessment Programme (NHS Health Check) PhD thesis |

Hammersmith and Fulham (London, UK) GP practices N= 42 306 |

Cross-sectional study of electronic medical records of patients eligible for NHS Health Checks, describes BMI recording completeness |

|

Bhaskaran et al, 201335 Representativeness and optimal use of body mass index (BMI) in the UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) |

UK-wide database; Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) N= 325 948 |

Descriptive study of completeness of BMI recording for a sample of >16-year-olds within this primary care database |

|

Booth et al, 201532 Access to weight reduction interventions for overweight and obese patients in UK primary care: population-based cohort study |

UK-wide database; Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) N= 91 413 |

Retrospective cohort study of recorded weight management intervention offers for a sample of overweight/obese patients within this primary care database |

|

Booth et al, 201331 Epidemiology of clinical body mass index recording in an obese population in primary care: a cohort study |

UK-wide database; General Practice Research Database (GPRD) N= 40 000–46 000 per year |

Retrospective cohort study of the epidemiology of recording of BMI for a sample of obese patients within this primary care database |

|

Dalton et al, 201136 Implementation of the NHS Health Checks programme: baseline assessment of risk factor recording in an urban culturally diverse setting |

North West London (UK) GP practices participating in pilot NHS Health Checks Programme N= 21 510 |

Cross-sectional study of electronic medical records of patients eligible for NHS Health Checks, describes BMI recording completeness |

|

Goodfellow et al, 201637 Cluster randomised trial of a tailored intervention to improve the management of overweight and obesity in primary care in England |

East Midlands (UK) GP practices N= 32 079 | Cluster randomised controlled trial of an intervention to improve obesity management in primary care. Data from the control arm describe BMI recording and interventions offered to overweight/obese patients aged >16 years in normal practice |

|

Osborn et al, 201133 Inequalities in the provision of cardiovascular screening to people with severe mental illnesses in primary care. Cohort study in the United Kingdom THIN Primary Care Database 2000–2007 |

UK-wide database; The Health Improvement Network (THIN) N= 95 512 |

Retrospective cohort study describing BMI recording in patients aged >18 years within the database with serious mental illness and for controls (the group of interest here) |

Where subjects are described as overweight or obese this refers to a BMI of ≥25 and ≥30 kg/m2, respectively.

N refers to the number of subjects in the study relevant to the review research question. BMI = body mass index.

Table 3.

Summary of patient characteristics by study

| Study | Cohort | Source | Included patients, na | GP practices, n | Mean age, years | Male, % | Ethnic group | Socioeconomic status | Mean BMI | Proportion with BMI record (within specified timeframe)b | Proportion with record of weight loss intervention |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Artac 201334 | 40–74 years without known CVD or diabetes | Hammersmith and Fulham GP practices | 42 306 | 28 | 52.2 | 46.2 | 35.9% white British, | ‘Diverse’ 2.5% South Asian, and 8.6% black (data missing 22.3%) | 26.6 | Males: 57.9% Females: 60.7% (within 5 years) in 2008/2009 | Not measured |

| Bhaskaran 201335 | >16 years with any historical BMI record | CPRD database | 325 948 | – | -– | – | – | – | ∼26 | 79% (any record) 52% (within 3 years) in 2011 | Not measured |

| Dalton 201136 | 35–74 years without known CVD or diabetes | North West London GP practices | 21 510 | 14 | 50.2 | 52.9 | 38.5% white, 39.6% South Asian, 10.4% black (data missing for 55%) | More deprived than the UK | – Females: 67.6% (within 5 years) in 2008/2009 |

Males: 79.3% | Not measured |

| Osborn 201133 | >18 years without SMI or CVD | THIN database | 95 512 | 420 | 53.2 | 47.4 | – | Similar to the UK | – | Males: 27.6% Females: 37.3% (within 1 year) in 2007 | Not measured |

| Booth 201532 | >18 years, BMI ≥25 record within the study period | CPRD database | 91 413 | 491 | 56 | 53 | – | Low levels of deprivation | – | All, by definition | Morbidly obese: males 40%, females 41.9% Non-morbidly obese: males 15.8%, females 19.8% within 2005–2012 |

| Booth 201331 | >18 years, BMI ≥30 or medical code for obesity 1997–2007 | GPRD database | 40 728 | 127 | – | 41 | – | Higher numbers in most deprived quintiles | 37 female 35.5 male | Males: 45.6% Females: 52.1%, within 2009 | Not measured |

| Goodfellow 201637 | >16 years, BMI ≥25 before the study period | East Midlands GP practices | 32 079 | 16 | 50 | 47.5 | 65.6% white, 16.7% South Asian, 6.3% black | More deprived than the UK | 30.2 (SD 5.4) average | 42.7% (SD 10.3%)c within 11-month study period 2013/2014 | 15.1% (SD 10.8%) offered within 11-month study period 2013/2014 |

Only from the group and time period of meeting inclusion criteria. The study may have reported on a larger group overall.

Data shown are from most recent time period if the study reported on multiple periods.

BMI or waist circumference recorded. – = not stated. Morbidly obese refers to a BMI ≥40 kg/m2. BMI = body mass index. CVD = cardiovascular disease. CPRD = Clinical Practice Research Datalink. GPRD = General Practice Research Database. SD = standard deviation. SMI = serious mental illness. THIN = The Health Improvement Network.

Proportion of patients with a documented BMI

The proportion of adult patients with any record of BMI was 79%; however, when the recording period was recent, this decreased to between 57.9% and 79.3% for males and 60.7% and 67.6% for females when considering the previous 5 years,34,36 and to 52% for the previous 3 years.35 Further, when BMI documentation was considered within 11–12 months, which is closer to the QOF register, this ranged from 27.6% to 45.6% for males and 37.3% to 52.1% for females.31,33,37

Proportion of patients with a documented offer of a weight management intervention

The offer of a weight management intervention was measured in two studies: 15.1% of overweight or obese adults were offered an intervention in one 11-month period studied;37 in another study the proportions varied greatly by level of overweight and obesity, with approximately 40% and 41.9%, respectively, of morbidly obese males and females being offered an intervention, while this reduced to 15.8% and 19.8% of non-morbidly obese males and females, and 10% of overweight patients.32

Patient factors associated with the outcomes

All the studies described a pattern of association between BMI recording and increasing patient age, and also with female sex. Several studies showed higher rates of BMI recording for older patients, higher BMI, or comorbidities, and suggested that this was because these groups tend to consult primary care practitioners more often. Five studies31–34,36 reported that BMI recording or weight loss intervention offer rates were associated with increasing deprivation at the patient level (generally based on postcode).

DISCUSSION

Summary

This systematic review included seven studies in total: four large UK-wide studies and three regional studies with either a BMI record or an offer of weight loss intervention documented for adult patients in routine primary care consultations in the UK. The general proportion of adult patients with a documented BMI was reported at 58–79% over the longer term, and 28–37% where the record was within 12 months. The proportion of overweight/obese patients with a recent documented BMI record was 43–52%. The proportion of overweight/obese adult patients with a documented offer of weight loss intervention was reported in a less consistent manner and ranged from 15% to 42%. Regional settings of the data collection and different timeframes for the intervention offer may account for the wide variation.

Higher rates of documentation were associated with patients’ older age, female sex, higher BMI, coexistent chronic disease, and higher deprivation. This was attributed to primary care consultation rates being higher for these groups,38,39 leading to increased opportunity for recognition and recording.

Strengths and limitations

The comprehensive nature of the search strategy, with the inclusion of all study designs, is a strength of the study. Further, the collection of data from patient records allowed comparability among studies. Patient electronic health records, particularly within quality-controlled research databases, are a strong source of data for primary care research but they do not cover verbal exchanges or elements such as patient refusal.

Although the review included studies with adult patients served by the UK primary care system in the last 10 years, the external validity for some studies is limited by those that were regional databases or where studies only included overweight/obese patients and differing lengths of time for which documentation in the patient record was measured. A limitation of the review is that the classification of an ‘up-to-date’ BMI record varied among studies. Although the 2006 QOF indicator implies that the period of interest is 12 months, there is no consensus in the literature over how recent a BMI record needs to be to be representative. To deal with this variability, this review has reported on categories of BMI record recency. A further limitation is that it is possible that participants in longitudinal studies were not representative of the general primary care adult population, and awareness of being studied could have altered the behaviour of the primary care team or patients involved in the control arms.

The systematic review aimed to draw inferences for the whole UK adult primary care patient population, but it is challenging to account for adults who either are not registered with a GP or who choose not to consult their GP. Estimating the number of unregistered adults in the UK is not straightforward.40

Comparison with existing literature

The results from the synthesis of the included papers in this review show coherence with the results of publications that have presented data before introduction of the QOF in 2006. In 2003, 42% of obese adults had a BMI recorded and 40% had been given weight management advice in a primary care study.41 A cross-sectional study from 2004 on the electronic GP records of 435 102 patients in England showed that 56.8% of males and 69.3% of females had a BMI record, supporting the finding of this review that females have higher rates of recording.42

This review did not include data from more subjective outcome measures such as patient self-report of weight loss discussion, but a study of this nature found that less than one-third of overweight or obese patients reported that they had received lifestyle advice for weight management from their GP,43 a figure within the range of the proportion of patients with a documented weight loss intervention offer in this review. A small study of 42 videotaped routine consultations by GPs in Scotland showed that weight management was rarely mentioned, even when the patient was overweight or obese.44

Implications for research and practice

The growing burden of obesity on primary care and the discrepancies between data sourced in primary care and accepted measures of ‘true prevalence’ of overweight/obesity in the UK support the case for changes to policy and practice in this area.

A large, UK-wide observational study to gather contemporary data from routine consultations between adult patients and all members of the primary care team would be invaluable in considering the uncertainties surrounding undocumented recognition, discussion, and intervention for overweight/obesity, including an exploration of the role of patient refusal to be weighed or engage in weight management.

Future studies would benefit from closer integration with the policy context, for example, consistent use of outcome measures that reflect the values and recommendations of the NICE guidelines and QOF indicators.

Structured recording of patient BMI and interventions offered could improve the overall prevalence of recognition of overweight/obesity and decrease the inequalities that likely result from the differences in practice between patient groups. The proposed QOF indicator addition — ‘The percentage of patients aged 18 or over … who have had a record of a BMI being calculated in the preceding 5 years (and after their 18th birthday)’ — may prompt improvements, although the obesity register QOF has remained unchanged for 2017 and the future of QOF in England is uncertain generally. Complementary interventions may include electronic prompts to record patients’ weight at registration or yearly intervals and facilities for patients to submit their own weight record remotely. Attention should be paid to the patient groups revealed by this review to be most underserved, such as younger males and overweight/obese individuals with no comorbidities.

Qualitative research suggests that some GPs believe patients carry the responsibility for their obesity and that primary care is not the appropriate source of intervention,45,46 and GP motivation to consider weight is damaged by a real and perceived lack of available and effective interventions.5,32,47 This presents a challenge to the improvement of weight management’s integration into a primary care system already struggling with capacity. In contrast, public health and obesity experts view obesity as a chronic disease, and maintain that primary care healthcare professionals are vital in dealing with the problem.48

Funding

This work was supported by the South West Public Health Training Programme through funding Joanna C McLaughlin and Kathryn Hamilton, who are Public Health Specialty Registrars. Ruth Kipping works in the Centre for the Development and Evaluation of Complex Interventions for Public Health Improvement (DECIPHer), a UKCRC Public Health Research Centre of Excellence. Joint funding (MR/KO232331/1) from the British Heart Foundation, Cancer Research UK, Economic and Social Research Council, Medical Research Council, the Welsh Government, and the Wellcome Trust, under the auspices of the UK Clinical Research Collaboration, is gratefully acknowledged. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and not necessarily any of the funding bodies listed here.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required for this systematic review methodology.

Provenance

Freely submitted; externally peer reviewed.

Competing interests

The authors have declared no competing interests

Discuss this article

Contribute and read comments about this article: bjgp.org/letter

REFERENCES

- 1.Jackson SE, Wardle J, Johnson F, et al. The impact of a health professional recommendation on weight loss attempts in overweight and obese British adults: a cross-sectional analysis. BMJ Open. 2013;3(11):e003693. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duaso MJ, Cheung P. Health promotion and lifestyle advice in a general practice: what do patients think? J Adv Nurs. 2002;39(5):472–479. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . Obesity: identification, assessment and management. CG189. London: NICE; 2014. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg189/chapter/1-recommendations#surgical-interventions (accessed 14 Jul 2017) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . Weight management: lifestyle services for overweight or obese adults. PH53. London: NICE; 2014. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ph53 (accessed 4 Jul 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mercer S. How useful are clinical guidelines for the management of obesity in general practice? Br J Gen Pract. 2009. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp09X472917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Fernandes CMB, Clark S, Price A, Innes G. How accurately do we estimate patients’ weight in emergency departments? Can Fam Physician. 1999;45:2373–2376. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anglemyer BL, Hernandez C, Brice JH, Zou B. The accuracy of visual estimation of body weight in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2004;22(7):526–529. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hall WL, Larkin GL, Trujillo MJ, et al. Errors in weight estimation in the emergency department: comparing performance by providers and patients. J Emerg Med. 2004;27(3):219–224. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2004.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Corbo J, Canter M, Grinberg D, Bijur P. Who should be estimating a patient’s weight in the emergency department? Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12(3):262–266. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2004.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bloomfield R, Steel E, MacLennan G, Noble DW. Accuracy of weight and height estimation in an intensive care unit: implications for clinical practice and research. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(8):2153–2157. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000229145.04482.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sebo P, Haller DM, Pechère-Bertschi A, et al. Accuracy of doctors’ anthropometric measurements in general practice. Swiss Med Wkly. 2015;145:w14115. doi: 10.4414/smw.2015.14115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Robinson E, Parretti H, Aveyard P. Visual identification of obesity by healthcare professionals: an experimental study of trainee and qualified GPs. Br J Gen Pract. 2014. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp14X682285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Post RE, Mainous AG, Gregorie SH, et al. The influence of physician acknowledgement of patients’ weight status on patient perceptions of overweight and obesity in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(4):316–321. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rose SA, Gokun Y, Talbert J, Conigliaro J. Screening and management of obesity and perception of weight status in Medicaid recipients. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2013;24(2 Suppl):34–46. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2013.0098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Noel PH, Copeland LA, Pugh MJ, et al. Obesity diagnosis and care practices in the Veterans Health Administration. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(6):510–516. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1279-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bardia A, Holtan SG, Slezak JM, Thompson WG. Diagnosis of obesity by primary care physicians and impact on obesity management. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82(8):927932. doi: 10.4065/82.8.927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aveyard P, Lewis A, Tearne S, et al. Screening and brief intervention for obesity in primary care: a parallel, two-arm, randomised trial. Lancet. 2016;388(10059):2492–2500. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31893-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Health and Social Care Information Centre Quality and Outcomes Framework — prevalence, achievements and exceptions report: England, 2015–16. 2016. http://www.content.digital.nhs.uk/catalogue/PUB22266/qof-1516-rep-v2.pdf (accessed 14 Jul 2017)

- 19.British Medical Association General practice in the UK background briefing April 2017. 2017. https://www.bma.org.uk/-/media/files/pdfs/news%20views%20analysis/press%20briefings/general-practice.pdf?la=en (accessed 28 Jul 2017)

- 20.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . New indicators to be added to the NICE QOF menu and amendments to existing QOF indicators. London: NICE; 2016. https://www.nice.org.uk/Media/Default/Standards-and-indicators/indicators-general-practice-aug-16.pdf (accessed 18 Jul 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ashworth M, Gulliford MC. Funding for general practice in the next decade: life after QOF. Br J Gen Pract. 2017. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp17X688477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 22.Blackburn M, Stathi A, Keogh E, Eccleston C. Raising the topic of weight in general practice: perspectives of GPs and primary care nurses. BMJ Open. 2015;5(8):e008546. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Blane DN, Macdonald S, Morrison D, O’Donnell CA. Interventions targeted at primary care practitioners to improve the identification and referral of patients with co-morbid obesity: a realist review protocol. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1):61. doi: 10.1186/s13643-015-0046-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parry LL, Netuveli G, Parry J, Saxena S. A systematic review of parental perception of overweight status in children. J Ambul Care Manage. 2008;31(3):253–268. doi: 10.1097/01.JAC.0000324671.29272.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thomson H, Thomas S, Sellstrom E, Petticrew M. The health impacts of housing improvement: a systematic review of intervention studies from 1887 to 2007. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(Suppl 3):s681–s692. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.143909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Taylor BJ, Dempster M, Donnelly M. Grading gems: appraising the quality of research for social work and social care. Br J Soc Work. 2007;37(2):335–354. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wells G, Shea B, O’Connell D, et al. The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. Ottawa: Department of Epidemiology and Community Medicine, University of Ottawa; 2014. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.htm (accessed 18 Jul 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 28.Joanna Briggs Institute . The Joanna Briggs Institute reviewers’ manual 2014: the systematic review of prevalence and incidence data. Adelaide: Joanna Briggs Institute, University of Adelaide; 2014. https://joannabriggs.org/assets/docs/sumari/ReviewersManual_2014-The-Systematic-Review-of-Prevalence-and-Incidence-Data_v2.pdf (accessed 13 Jul 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guyatt G, Sackett D, Cook D. Users’ guides to the medical literature. II. How to use an article about therapy or prevention. JAMA. 1993;270(21):2598–2601. doi: 10.1001/jama.270.21.2598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336(7650):924–926. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Booth HP, Prevost AT, Gulliford MC. Epidemiology of clinical body mass index recording in an obese population in primary care: a cohort study. J Public Health (Oxf) 2013;35(1):67–74. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fds063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Booth HP, Prevost AT, Gulliford MC. Access to weight reduction interventions for overweight and obese patients in UK primary care: population-based cohort study. BMJ Open. 2015;5(1):e006642. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Osborn DP, Baio G, Walters K, et al. Inequalities in the provision of cardiovascular screening to people with severe mental illnesses in primary care. Cohort study in the United Kingdom THIN Primary Care Database 2000–2007. Schizophr Res. 2011;129(23):104–110. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Artac M. Evaluation of a national cardiovascular risk assessment programme (NHS Health Check) London: Imperial College London; 2013. https://spiral.imperial.ac.uk/handle/10044/1/24725 (accessed 18 Jul 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bhaskaran K, Forbes HJ, Douglas I, et al. Representativeness and optimal use of body mass index (BMI) in the UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) BMJ Open. 2013;3:e003389. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dalton AR, Bottle A, Okoro C, et al. Implementation of the NHS Health Checks programme: baseline assessment of risk factor recording in an urban culturally diverse setting. Fam Pract. 2011;28(1):34–40. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmq068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goodfellow J, Agarwal S, Harrad F, et al. Cluster randomised trial of a tailored intervention to improve the management of overweight and obesity in primary care in England. Implement Sci. 2016;11(1):77. doi: 10.1186/s13012-016-0441-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang Y, Hunt K, Nazareth I, et al. Do men consult less than women? An analysis of routinely collected UK general practice data. BMJ Open. 2013;3(8):e003320. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hippisley-Cox J, Vinogradova Y. Trends in consultation rates in general practice 1995/1996 to 2008/2009: analysis of the QResearch® database. London: QResearch, Information Centre for Health and Social Care; 2009. http://www.content.digital.nhs.uk/catalogue/PUB01077/tren-cons-rate-gene-prac-95-09-95-09-rep.pdf (accessed 10 Aug 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 40.Baker C. Population estimates & GP registers: why the difference? 2016 https://secondreading.uk/social-policy/population-estimates-gp-registers-why-the-difference/ (accessed 10 Aug 2017) [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moore H, Summerbell CD, Greenwood DC, et al. Improving management of obesity in primary care: cluster randomised trial. BMJ. 2003;327(7423):1085. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7423.1085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.de Lusignan S, Hague N, van Vlymen J, et al. A study of cardiovascular risk in overweight and obese people in England. Eur J Gen Pract. 2006;12(1):19–29. doi: 10.1080/13814780600757260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Booth AO, Nowson CA. Patient recall of receiving lifestyle advice for overweight and hypertension from their General Practitioner. BMC Fam Pract. 2010;11:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-11-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Laidlaw A, McHale C, Locke H, Cecil J. Talk weight: an observational study of communication about patient weight in primary care consultations. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2015;16(3):309–315. doi: 10.1017/S1463423614000279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Epstein L, Ogden J. A qualitative study of GPs’ views of treating obesity. Br J Gen Pract. 2005;55(519):750–754. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Henderson E. Obesity in primary care: a qualitative synthesis of patient and practitioner perspectives on roles and responsibilities. Br J Gen Pract. 2015. DOI: https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp15X684397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Royal College of Surgeons Commissioning guide: weight managment and assessment clinics (Tier 3) 2014. http://www.bomss.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/Commissioning-guide-weight-assessment-and-management-clinics-published.pdf (accessed 23 Jun 2017)

- 48.Boyce T, Peckham S, Hann A, Trenholm S. A pro-active approach. Health promotion and ill-health prevention. An inquiry into the quality of general practice in England. London: King’s Fund; 2010. http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/files/kf/field/field_document/health-promotion-ill-health-prevention-gp-inquiry-research-paper-mar11.pdf (accessed 13 Jul 2017) [Google Scholar]