Abstract

Vertebrate red blood cells (RBCs) arise from erythroblasts in the human bone marrow through a process known as erythropoiesis. Iron uptake is a crucial hallmark, essential for heme biosynthesis in the differentiating erythroblasts, which are dedicated to producing hemoglobin. Erythropoiesis is facilitated by a network of intracellular transport proteins, chaperones, and circulating hormones. Intracellular iron is targeted to the mitochondria for incorporation into a porphyrin ring to form heme and cytosolic iron-sulfur proteins, including Iron Regulatory Protein 1 (IRP1). These processes are tightly regulated to prevent both excess and insufficient levels of iron and heme precursors. Crosstalk between the heme and iron-sulfur synthesizing pathways has been demonstrated to serve as a regulatory feedback mechanism. The activity of δ-aminolevulinic acid synthase (ALAS), the first and rate-limiting enzyme of heme biosynthesis, is a fundamental node of this regulation. Recently, the mitochondrial unfoldase, ClpX, has received attention as a novel key player that modulates this step in heme biogenesis, implicating a role in the pathophysiology of anemic diseases. This chapter reviews the canonical pathways in intracellular iron and heme trafficking and recent findings of iron and heme metabolism in vertebrate red cells. A discussion of the molecular approaches to studying iron and heme transport is provided to highlight opportunities for revealing therapeutic targets.

Keywords: Transferrin Cycle, Mitochondria, Iron-Sulfur Clusters, Red Cells, Mitochondrial Clpx, Hinokitiol, δ-ALAS, Anemia, Erythropoietic Protoporphyria

IRON IN BIOLOGY

Iron is an essential metal found in living systems as ferric Fe3+ or ferrous Fe2+ ions. Iron is essential for several cellular processes including DNA synthesis, enzyme and redox catalysis, electron transport, mitochondrial respiration, O2 and NO gas sensing, and cell survival.1,2 Although these are essential roles for iron, most of the iron in vertebrates is incorporated into a porphyrin ring to form heme, which is required for oxygen transport by RBCs. The daily production of 200 billion new erythrocytes within the human bone marrow requires an efficient iron trafficking system to ensure optimal heme biosynthesis.3 The high demand for iron in developing erythrocytes is primarily fulfilled by splenic and hepatic macrophages that recycle senescent erythrocytes.4,5 Dietary iron can also enter the circulation via the gastrointestinal tract,6,7 and iron can be mobilized from ferritin storage within the liver.5,8,9 Dietary heme iron, primarily derived from meats, is more efficiently acquired by enterocytes than dietary non-heme iron, but the molecular process remains poorly understood.3,6,10

Iron metabolism must be tightly regulated and facilitated by transport molecules because free iron forms reactive oxygen species through Fenton chemistry.11 Once iron is taken up by the cell, iron can be targeted to the mitochondria for heme and iron-sulfur cluster biosynthesis.12–15 Within the mitochondrion, the metabolic processes associated with iron uptake and hematopoiesis are interdependent and facilitated by a network of enzymes, including δ-aminolevulinic acid-synthase (ALAS, EC 2.3.1.37) and ferrochelatase (FECH, EC 4.99.1.1). Recently, novel mechanisms associated with iron uptake and heme metabolism have been identified, which can further our understanding of the biochemical properties of erythroid development. These mechanistic insights may also reveal the pathological nature of red cell disorders that are a potentially key area for therapeutic discovery.

CELLULAR IRON UPTAKE FROM THE CIRCULATION

The hepatic hormone hepcidin, which is produced in the liver, regulates iron entry into the circulation by tuning the functional activity of ferroportin (Slc40a1). Regulation of systemic iron homeostasis via hepcidin was recently reviewed in detail elsewhere.16–18 Ferroportin is a conserved vertebrate iron exporter located on the cell surface of macrophages, duodenal enterocytes, placental cells, and hepatocytes.19 These cells release iron into the plasma after oxidation to Fe3+, which becomes rapidly bound by transferrin (Tf), a glycoprotein that has two high affinity sites for ferric iron. Iron loaded Tf (diferric transferrin, Tf-Fe23+) binds to its cognate transferrin receptor-1 (TFR1), which is located on the cell surface of all cells, especially erythroid precursors in the bone marrow. The Tf-Fe23+-TFR1 complex is internalized by the cell within an endosome through clathrin-mediated endocytosis (Fig. 1).20 The endosomal pH is acidified by proton pumps, which initiate the release of Tf and diferric iron from the TFR1. Ferric iron is reduced to ferrous iron within the endosome by metalloreductase proteins of the STEAP (six-transmembrane epithelial antigen of prostate) family.21 Iron at this stage of cellular uptake is exported from the endosome to the cytosol by divalent metal transporter-1 (DMT1) or routed to the mitochondria.9, 11 The gene DMT1 was identified in a functional screen of rat cDNA that induced iron transport activity in Xenopus laevis oocytes22 and positional cloning in the mk mouse exhibiting microcytic anemia.23

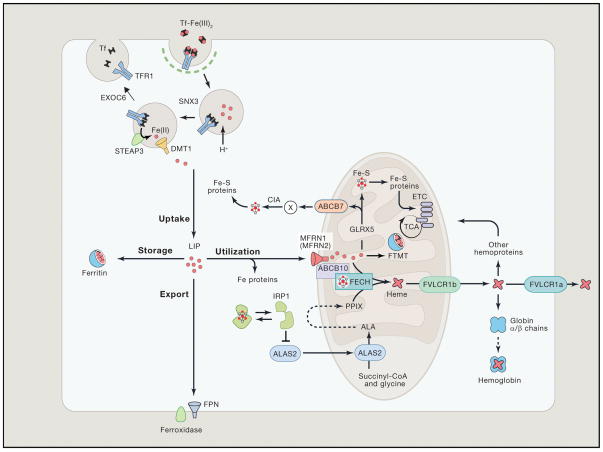

Figure 1. Iron Metabolism in Erythroid Cells.

Most of the daily amount of iron needed for erythropoiesis is recycled by specialized macrophages in the spleen and liver. Iron acquisition in erythroid cells is dependent on endocytosis of diferric transferrin (Tf-Fe2) via the transferrin receptor (TFR1). In acidified endosomes, iron is freed from Tf and exported into the cytoplasm by DMT1 after reduction of the metal by STEAP3 (six-transmembrane epithelial antigen of prostate 3). The recycling of Tf and TFR1 is crucial for optimal iron uptake and requires SNX3 (sortin nexin 3) and EXOC6 (exocyst complex component 6 also known as Sec15L1). The metabolically active labile iron pool is used directly for incorporation into iron proteins or transported into mitochondria via mitoferrin 1 (MFRN1, MFRN2 in non-erythroid cells), which forms a complex with ABCB10 and FECH. In mitochondria, iron is inserted into protoporphyrin IX (PPIX) by ferrochelatase (FECH) to produce heme. Heme is transported out of the mitochondria via the 1b isoform of FLVCR (feline leukemia virus subgroup C cellular receptor) for incorporation into hemoproteins, mostly hemoglobin; the FLVCR1a isoform exports heme from the cytosol. Mitochondrial iron is also used for Fe-S cluster synthesis, which among other factors involves GLRX5 (Glutaredoxin-related protein 5). Fe-S clusters are incorporated into client proteins throughout the cell. Maturation of cytosolic Fe-S proteins by the CIA (cytosolic Fe-S cluster assembly) system depends on an unknown compound (designated X) generated during mitochondrial Fe-S cluster biosynthesis. Its export into the cytosol requires the ATP-binding cassette protein ABCB7. Fe-S proteins play key roles in the regulation of iron metabolism. For instance, under conditions of iron or GLRX5 deficiency, iron regulatory protein 1 (IRP1) is devoid of a Fe-S cluster and inhibits translation of ALAS2, the first and rate-limiting enzyme of heme biogenesis, thereby preventing the accumulation of toxic heme intermediates. In the mitochondria, excess iron can be stored in the organelle-specific form of mitoferritin (FTMT). In the cytosol, excess iron is sequestered within heteropolymers of ferritin H and L chains. Cellular iron efflux is mediated by ferroportin (FPN) and requires iron oxidation on the extracellular side. Reprinted with permission from Muckenthaler et al.20 and Cell (Elsevier, Inc).

Once the Tf-Fe23+-TFR1 complex is internalized, the endosome undergoes recycling, a mechanism that is dependent on various accessory proteins, such as sorting nexin 3 (snx3)24 and exoc6 (exocyst complex component 6 also known as Sec15L1).25, 26 Snx3 is a phosphoinositide-binding protein that is highly expressed in developing red cells and hematopoietic tissues for sorting of Tf-TFR1 complexes from early endsomes to recycling endosomes. Exoc6 (sec15L1), a protein in the mammalian exocyst complex that functions through interactions with GTPase binding proteins, is required for trafficking of the endosome to the cell surface. The loss-of-function of these accessory proteins in cells of high heme production and iron turnover, such as erythroblasts, results in anemias and heme defects, which would otherwise not be impaired in other cells. 24, 25

INTRACELLULAR IRON TRAFFICKING

Ferrous iron is either stored in cytosolic ferritin or directly targeted to the mitochondria for heme and iron-sulfur cluster biosynthesis. The storage of iron within cytosolic ferritin may be facilitated by human poly (rC)–binding protein (PCBP).27,28 By using a cDNA library derived from human liver, PCBP was discovered to deliver cytosolic iron to human ferritin in yeast cells containing an iron-responsive reporter.28 PCBP depletion leads to microcytic anemia suggesting its requirement for erythroid heme and globin production. 29

The function of PCBP is not limited to ferritin iron delivery and rather has a broad role as an intracellular iron chaperone. PCBP functions as a metallo-chaperone by delivering iron to enzymes that require iron as a cofactor. For example, delivery of iron to prolyl hydroxylase (PHD2) by PCBP facilitates the degradation of hypoxia inducible factor (HIF2a),30 a transcription factor involved in the induction of erythropoietin (EPO). PCBP was also discovered to deliver iron to deoxyhypusine hydroxylase (DOHH),31 a dinuclear iron enzyme that post-translationally modifies eukaryotic initiation factor 5a (eIF5a) for eukaryotic mRNA translation. Furthermore, PCBP interacts with cellular iron importers and exporters such as divalent metal transporter (DMT1) and ferroportin (FPN) respectively.32

Although the storage and mineralization of iron within ferritin is an essential step in its intracellular trafficking, ferritin iron must be released to be utilized by the cell, especially for heme and iron-sulfur cluster biosynthesis in the mitochondria. During iron-deprived conditions, expression of the autophagic cargo receptor, nuclear receptor coactivator 4 (NCOA4), is increased. NCOA4 specifically binds to ferritin and directs it to autophagosomes. Fusion of ferritin-containing autophagosomes with lysosomes results in ferritin degradation and release of its iron core. Although cellular ferritin depletion produces an unremarkable phenotype, NCOA4 null cells display impaired hemoglobinization, a finding that implicates NCOA4 in erythroid maturation and hemoglobinization. 29

The intracellular trafficking of iron to ferritin by PCBP and autophagic release from ferritin by NCOA4 is a mechanism that the cell may utilize for mitochondrial iron import in early proerythroblasts (reviewed in 29, 33, and 34). Alternatively, the Tf-Fe23+-TFR1 containing endosome may make direct mitochondrial contact in rapidly proliferating late erythroblasts (reticulocytes) with high iron demands for heme synthesis via a process termed “Kiss-and-Run”.14,35 Endosome-mitochondria interactions have been reported in live reticulocytes using three-dimensional confocal microscopy.36 This process may be beneficial to the cell when there is a high demand for iron, such as in the developing erythroblast.14, 29 The precise biochemical mechanism for the “Kiss-and-Run” model and the most direct route of TFR1-delivered Fe to the mitochondria remains under active investigation.

MITOCHONDRIAL IRON METABOLISM

Mitochondrial iron import occurs via mitoferrin-solute carriers mitoferrin-1 (MFRN1, Slc25a37), and mitoferrin-2 (MFRN2, Slc25a28) at the inner mitochondrial membrane.37 MFRN1, the paralog highly expressed in developing erythroid cells, was originally discovered in the zebrafish mutant frascati, that exhibits a deficiency in mitochondrial iron uptake and consequently has profound hypochromic anemia. Conventional and conditional gene targeting of MFRN1 in the mouse have validated its crucial role in erythroid mitochondrial heme and Fe-S metabolism in higher vertebrates.38–39 The function of MFRN solute carriers for transporting iron is highly conserved across eukaryotes, as shown by the functional complementation of deficiencies in the fungal orthologs, MRS3 and MRS4, by their vertebrate gene.37 Although this chapter discusses the canonical pathways of iron transport in vertebrate erythroid cells, excellent reviews on iron transport in yeast and fungal organisms can be found elsewhere.40–42 MFRN2, which is more ubiquitously expressed, is proposed to deliver iron in erythroid progenitors and non-erythroid tissues.37–39 These two MFRN solute carriers were thought to provide the main source of mitochondrial iron based on combinatorial silencing of these carriers.43

MFRN1 tissue-restricted expression in erythroid tissues is regulated at the transcriptional44, 45 and post-transcriptional levels.43 MFRN1 is stabilized post-translationally in an oligomeric complex with ferrochelatase46 and the ATP-binding cassette ABCB1047, and as a consequence, more iron is assimilated into the mitochondria as the demand for iron accelerates during terminal erythroid differentiation. The interaction of MFRN1 with ferrochelatase efficiently integrates two functional demands: heme synthesis with its iron importation into the mitochondria.46 ABCB10 is a translocase that was identified in mouse erythroid cells under the control of GATA-148, the master erythropoietic transcription factor. GATA-1 is a DNA binding protein that is responsible for recognition of a sequence motif within promoters and enhancers of numerous erythroid-expressed genes.49–51 GATA-1 mediates the temporal regulation and coordination of gene expression in erythroid and megakaryocytic lineages.

Iron is metabolized within the mitochondrial matrix for heme and iron-sulfur cluster assembly.12–15 Iron that is not utilized for heme or iron-sulfur cluster assembly is stored within mitochondrial ferritin (mitoferritin).52 Both cytosolic ferritin53 and mitoferritin54 mediated mineralization of iron minimize the production of potentially harmful hydrogen peroxide.

Heme is exported from the cytosol and mitochondria by feline leukemia virus subgroup C cellular receptor isoforms, 1a (FLVCR1a)55,56 and FLVCR1b,57,58 respectively. Although the reason for heme export by erythrocytes is unclear, FLVCR may play a role in protecting developing erythroid cells from heme toxicity and initiating hemoglobinization in differentiating erythroid progenitors.59 The conditions in which heme is exported from erythroid cells by FLVCR are nicely reviewed elsewhere.60

ABCB7 is involved in the export of an unidentified component required for cytosolic iron-sulfur protein assembly.61 Clinical mutations in ABCB7 are associated with a rare type of X-linked sideroblastic anemia (XLSA) associated with cerebellar ataxia.62, 63 The described processes of iron metabolism illustrate the essential nature of the mitochondria for transforming iron into the bioactive forms of heme and iron-sulfur containing proteins.64

PORPHYRIN AND HEME BIOSYNTHESIS

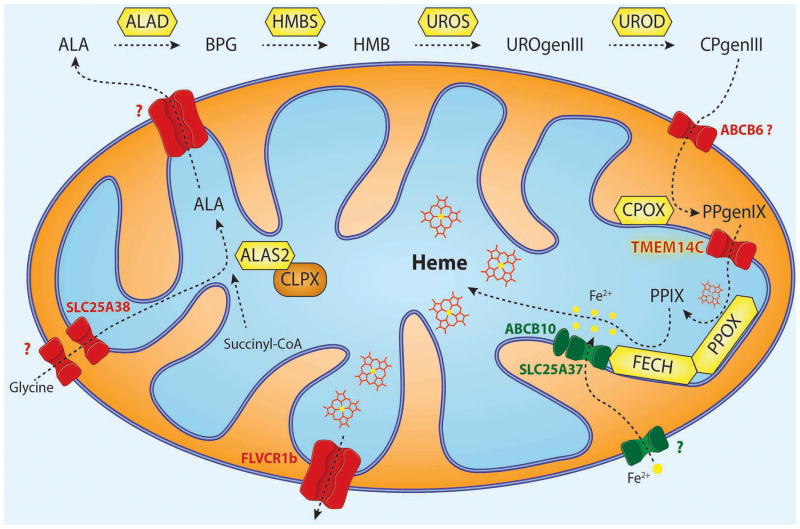

The biosynthesis of porphyrin and heme occurs through eight enzyme-catalyzed reactions within the mitochondria and cytosol (Fig. 2).65 The substrates required for the production of heme are glycine, succinyl-CoA, and ferrous iron. Glycine is transported to the mitochondrial matrix by SLC25A38, an amino acid carrier that is highly expressed in TFR1-positive erythroid cells.66–68 Succinyl-CoA, an intermediate of the citric acid cycle, undergoes a condensation reaction with glycine to form δ-aminolevulinic acid (ALA). This reaction is the first committed step in heme biosynthesis and is catalyzed by ALA-synthase (ALAS).69 There are two different paralogous genes for ALAS. ALAS1 is expressed ubiquitously, and ALAS2 is specific to erythroid cells.70 ALAS requires pyridoxal phosphate (PLP), the vitamin B6 metabolite, as a cofactor to function.71 Recent studies discovered a novel function for the mitochondrial chaperone, ClpX, in converting apo-ALAS to holo-ALAS through incorporation of the PLP-cofactor.72 The reaction yields ALA, which is transported to the cytosol, via an unidentified carrier, and undergoes four subsequent enzyme catalyzed reactions that lead to the production of the tetrapyrrole coporphyrinogen III (CPgenIII). It has been proposed that ABCB6, a protein located in the outer mitochondrial membrane that is up regulated in response to increased porphyrin levels, transports CPgenIII from the cytosol to the intermembrane space;73 this remains controversial in that ABCB6 has been reported as the Lan red group antigen, whose function is dispensable for erythropoiesis.74 CPOX, the antepenultimate enzyme that catalyzes an oxidative decarboxylation reaction, converts CPgenIII to form protoporphyrinogen IX (PPgenIX).75 PPgenIX is transported into the mitochondrial matrix by TMEM14C, a transmembrane protein discovered using independent bioinformatics searches of co-expressed heme genes76 and an RNAseq analysis of murine fetal liver derived erythroid cells.77 PPgenIX is converted into protoporphyrin IX (PPIX) by protoporphyrinogen oxidase (PPOX), which catalyzes a dehydrogenation reaction. In the eighth and final step of heme biosynthesis, the terminal enzyme ferrochelatase (FECH) converts PPIX into heme by catalyzing the transfer of iron to the porphyrin moiety. The described processes of heme biosynthesis are tightly orchestrated and must be coordinated with iron acquisition and globin gene expression during erythroid differentiation.78,79

Figure 2. Intracellular trafficking of heme intermediates in erythroid cells.

Glycine is imported via SLC25A38 and condenses with succinyl-CoA to form δ-aminolevulinic acid (ALA) in a reaction catalyzed by ALA synthase (ALAS2 in red cells).75 ALAS is activated by mitochondrial chaperone ClpX through promoting the incorporation of pyridoxal phosphate, an essential cofactor for ALAS function.72 After several catalytic conversions of heme precursors, coproporphyrinogen III (CPgenIII) is transported into the mitochondrial intermembrane space. It is then converted to protoporphyrinogen IX (PPgenIX) that is transported into the matrix by a mechanism requiring TMEM14C.77 Ferrochelatase (FECH) metallates protoporphyrin IX (PPIX) with iron to form heme. Studies have shown that iron enters the mitochondrial matrix via mitoferrin-1 (SLC25A37) in the inner mitochondrial matrix.37 SLC25A37 is stabilized by ABCB10 and exists in a large oligomeric complex with FECH.46,47 Heme is thought to be exported by FLVCR1b from the mitochondria into the cytosol, where it is incorporated into hemoproteins.57,58 Figure illustration courtesy of Johannes G. Wittig (Technische-Universität-Dresden, Germany). Reprinted with permission from Yien et al.65 and Oncotarget (Impact Journals, LLC).

REGULATION OF HEME METABOLISM BY IRE & IRP

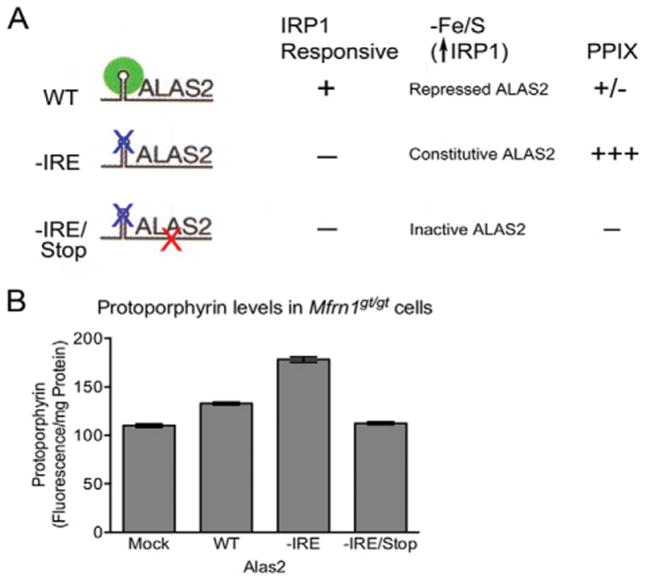

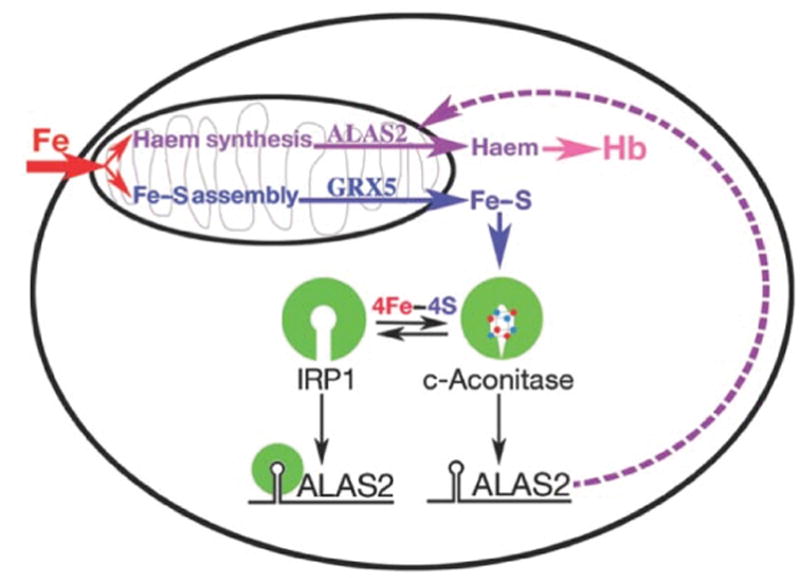

Owing to the essential nature of heme in erythropoiesis as well as the potential of heme to become toxic in excess, organisms have developed sophisticated ways to regulate heme biosynthesis. For example, the production of heme can be regulated at the translational and post-translational level by modulating the activity of ALAS. Translational control of erythroid specific ALAS2 is modulated by the iron-sulfur cluster ligated protein, Iron Regulatory Protein-1 (IRP1)80, 81 (Fig. 3).82 IRP1 has a bifunctional role, switching between two different states depending on the amount of cellular iron present. In the absence of iron, apo-IRP1 binds to the Iron Regulatory Element (IRE) located at the 5′ untranslated region (UTR) of the ALAS2 mRNA sequence. 5′ IRP1-IRE binding activity prevents ALAS translation, which results in the abrogation of heme production. However, when iron is sufficient, apo-IRP1 is converted to holo-IRP1, which leads to a loss of IRE binding activity in the 5′ UTR mRNA of ALAS and allows more synthesis of this enzyme. Holo-IRP1 functions as a cytoplasmic aconitase, an iron-sulphur protein that catalyzes the interconversion of citrate and isocitrate in the cytoplasm and NADPH generation.83,84

Figure 3. Loss of Fe–S cluster production interferes with IRP1-mediated intracellular iron homeostasis.

Model for the role of Fe–S cluster production in erythroid heme synthesis. Iron imported into mitochondria is used in the independent pathways of heme and Fe–S cluster biogenesis. Normal production of Fe–S clusters, which requires Glrx5, switches the bifunctional protein IRP1 to a cytoplasmic aconitase (c-aconitase); this permits ALAS2 protein synthesis needed for heme production. In the absence of Fe–S clusters, IRP1 has IRE-binding activity, and binds the 5′-IRE on ALAS2 mRNAs, blocking translation and thereby preventing heme production. Reprinted with permission from Wingert et al.82 and Nature (Macmillan Publishers, Ltd).

The cross talk between Fe-S cluster and heme synthesis was further genetically validated by examining the roles of glutaredoxin5 (glrx5), a mitochondrial monothiol involved in mitochondrial Fe-S cluster synthesis. A deficiency of glrx5 in the zebrafish mutant, shiraz, was shown to impair heme synthesis by affecting the synthesis of mitochondrial Fe-S and its export to the cytosol for assembly into IRP1 to form aconitase.82 With less iron-sulfur loaded in cytosolic aconitase, more apo-IRP1 inhibits the translation of Alas2 mRNA, resulting in a heme deficiency. A series of elegant functional studies including knockdown of IRP1 and mutations in the 5′ IRE-stem loop in shiraz zebrafish embryos, genetically validated the aconitase-IPR1 axis in regulating heme synthesis in vivo. Subsequently, defects in human GLRX5 was shown to cause sideroblastic anemia by impairing heme biosynthesis and depleting cytosolic iron.85,86

Inhibition of ALAS translation by IRP1 becomes critical when mitochondrial iron is limited, to prevent the accumulation of toxic PPIX intermediates, which can lead to the disease porphyria.87 This regulation demonstrates cross-talk between the protoporphyrin synthesis and iron-sulfur cluster assembly pathways, which work in synchrony to protect the cell when mitochondrial iron assimilation is insufficient. Profound anemia will develop when cellular iron import becomes compromised as in the absence of MFRN1 (Slc25a37). However, MFRN1-null zebrafish and mice do not exhibit porphyria, suggesting that a feedback mechanism is induced to protect against deleterious over-accumulation of protoporphyrin IX synthesis. A study in MFRN1-null embryonic stem cells found evidence for elevated IRP1-IRE binding activity as a protective measure to specifically attenuate ALAS translation and downstream porphyrin formation.39 The researchers measured the level of protoporphyrin in MFRN1-null cells expressing various ALAS2 constructs, including wildtype, -IRE, and –IRE/stop. The experiment revealed a dramatic increase in protoporphyrins within cells expressing –IRE compared to wildtype cells (Fig. 4).39 These findings suggest that constitutively active ALAS enzyme synthesis (not regulated by IRP-IRE interactions) was generating an over-accumulation of protoporphyrin. Furthermore, these findings illuminate the protective role of IRP1 in lowering ALAS expression and downstream protoporphyrin synthesis during iron insufficiency.

Figure 4. Mitochondrial heme and Fe/S cluster biogenesis are co-regulated.

Mfrn1gt/gt ES cells expressing various alas2 constructs. The schematic in (A) highlights the features of the ALAS2 constructs as well as the anticipated results. (B) PPIX levels were analyzed per milligram of total protein in Mfrn1 gt/gt cells transduced with various lentiviruses, shown in (A). Reprinted with permission from Chung et al 39 and The Journal of Biological Chemistry (The American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Inc).

The porphyria effect was recapitulated in MFRN1-null murine hepatocytes, by bypassing the block in ALAS2 translation with exogenous chemical supplementation of ALA.38 The increase in erythrocyte PPIX within the MFRN-null hepatocytes, following ALA supplementation, confirms the attenuation of ALAS2 translation during insufficient mitochondrial iron assimilation.38 Importantly, these studies reveal a critical link between the heme and iron-sulfur cluster biosynthetic pathways that provides cells with the ability to respond to limited mitochondrial iron stores as originally hypothesized for the glrx5 shiraz mutant.82

Although the regulation of ALAS activity by IRP/IRE is essential for coordinating heme synthesis and iron availability, there are other critical protein sensors that the cell utilizes for homeostatic control. A well established sensor of systemic iron homeostasis is hypoxia-inducible factor 2 alpha (HIF2α), which regulates iron absorption and erythropoiesis in absorptive enterocytes and kidney interstitial cells respectively.20 HIF2α expression is regulated by cellular O288,89, IRP190,91, and prolyl hydroxylase 2 (PHD2) 92 for stimulation of erythropoietin, a hormone responsible for erythroid precursor proliferation. Ferroportin (FPN1) is a direct HIF2α target gene in macrophages and subjected to multilayered transcriptional regulation by Btb and Cnc Homology 1 (BACH1).93 Heme derived from erythrophagocytosis liberates BACH1, a transcriptional repressor, from the FPN1 promoter to induce FPN transcription and downstream iron efflux.20 The IRP/IRE, HIF2α, and BACH1 iron signaling pathways play pivotal roles in red cell physiology, responding to nutrient availability, and may have implications for red cell disorders including hemochromatosis94 and erythrocytosis.95,96

MITOCHONDRIAL UNFOLDASE CLPX AND HEME METABOLISM

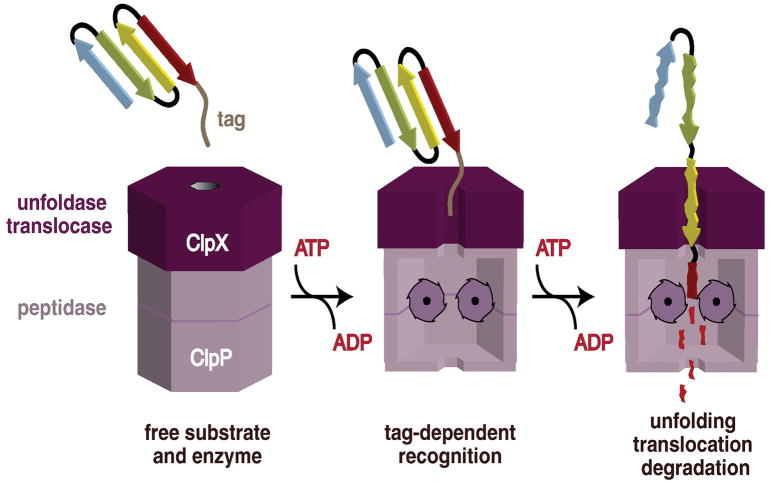

At the post-translational level, ALAS has been shown to be regulated by ClpXP,97 an enzyme that utilizes the energy of ATP hydrolysis to perform protein degradation. In bacteria, ClpXP is crucial for maintaining protein homeostasis and responding to environmental stress.98 However, in eukaryotes ClpX is found in the mitochondria and was recently discovered to be implicated in the regulation of heme synthesis by mediating the activation and turnover of ALAS.72,97 ClpXP is composed of both ClpX and ClpP, which function as a hexameric unfoldase and tetradecameric peptidase, respectively (Fig. 6).99 ClpX is an AAA+ (ATPase associated with diverse cellular activities) enzyme that utilizes energy generated from ATP hydrolysis to translocate target substrates through an axial pore into the ClpP proteolytic chamber for degradation. When heme is abundant in the mitochondrion, it binds to a heme regulatory motif located on ALAS1, which recruits ClpXP to degrade ALAS1.97 The heme regulatory motif contains cysteine-proline (CP) dipeptides, including CP1 and CP2 located in the presequence, and CP3 in the N-terminal region of mature ALAS protein. CP1 and CP2 regulate the translocation of ALAS into the mitochondria, and CP3 recruits ClpXP in a heme dependent manner for proteolytic degradation.97 The CP3 motif underscores a mechanism whereby heme can control ALAS turnover by negative feedback inhibition. However, ClpX was also demonstrated to function independently of ClpP, by activating ALAS (Fig. 2). Instead of degradation, ClpX catalyzes the insertion of PLP, a cofactor required for ALAS activity for the production of ALA and downstream heme biosynthesis.72 In this context ClpX employs limited unfolding without complete translocation into the ClpP protease.

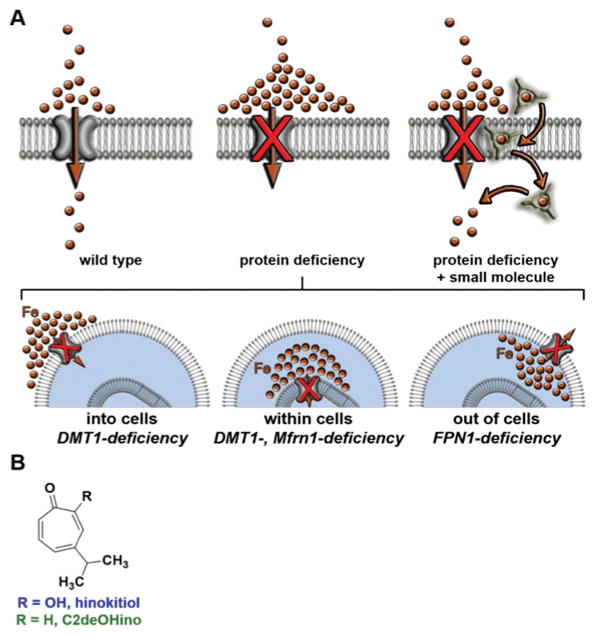

Figure 6. Restoring physiology to iron transporter-deficient organisms.

(A) A small molecule that autonomously performs transmembrane iron transport is hypothesized to harness local ion gradients of the labile iron pool that selectively accumulate in the setting of missing protein iron transporters. Brown spheres represent labile iron, which includes both ionic iron and iron weakly bound to small molecules such as citrate. (B) Structures of hinokitiol (Hino) and the transport-inactive derivative, C2-deoxy hinokitiol (C2deOHino). Reprinted with permission from Grillo et al 107 and American Association for the Advancement of Science.

Clinical mutations in ClpX were recently identified in patients exhibiting symptoms of erythropoietic protoporphyria (EPP).100 In these instances, the mutation was inherited in a pattern consistent with Mendelian dominant-segregation, and the affected individuals had normal DNA sequencing of FECH and ALAS2, which are genes previously implicated in the development of EPP.87 Lymphoblastoid cells obtained from the affected patients exhibited elevated ALAS activity and an increased cellular ALA metabolite level compared to unaffected relatives. DNA sequencing revealed a missense mutation in a highly conserved glycine residue in the ATP-binding Walker-A site of ClpX. Analysis of the mutation in vitro revealed diminished ATP hydrolysis activity within the ClpX hexamer. Expression of the mutant ClpX protein in cell culture recapitulated biochemical markers of EPP, including elevated cellular and blood PPIX as a result of increased ALAS enzymatic activity. Complementary experiments utilizing 35S-methione pulse-chase and cycloheximide101 (an inhibitor of de novo protein synthesis) treatments revealed a greater half life of ALAS protein in ClpX mutant expressing cells. This experiment suggested a greater abundance of ALAS in cells expressing the mutant ClpX allele, which corroborated a mechanism of inhibited protein turnover. Greater ALAS activity was also noted in zebrafish embryos by microinjection of cRNA encoding mutant ClpX, validating the in vitro findings.

The researchers concluded that the ClpX mutation diminished the degradation of ALAS by the ClpP protease, which resulted in a greater amount of ALAS and increased PPIX formation. These findings reveal a novel pathological interaction between ClpXP and ALAS, enzymes of mitochondrial homeostasis and heme biosynthesis respectively.

MOLECULAR APPROACHES TO ELUCIDATE IRON & HEME TRANSPORT

It is essential to study the pathways of iron and heme transport to develop therapies for human diseases associated with iron deficiency, metabolic disorders, mitochondriopathies, and hematologic diseases. However, since iron is mostly incorporated into proteins in the form of heme, studying non-heme iron metabolism and heme transport in eukaryotes is difficult without the proper tools and model organisms.

Elucidating the fundamental mechanisms of heme transport independently of iron trafficking can be accomplished using unique animal models including bloodless nematodes that lack orthologs to genes encoding enzymes for heme biosynthesis.75,102 For example, the bloodless nematode Caenorhabditis elegans (C. elegans) is unable to synthesize heme de novo, and instead, acquires heme from a host to survive and reproduce. C. elegans is unable to grow when deprived of iron unless rescued by increased heme levels in the growth medium.102 This observation indicates that C. elegans can use heme as an iron source when iron is limiting.

Bloodless nematodes can be specifically utilized to examine the conserved pathways of eukaryotic heme transport and to identify genes involved in iron trafficking. Bloodless nematodes were utilized to discover the HRG family, which are transmembrane proteins that bind and transport heme. The conserved genes Hrg-1 and Hrg-4 were identified as facilitators of intracellular heme availability and uptake.103 Human HRG is highly expressed in the brain, kidney, heart, and skeletal muscle and abundantly expressed in human cell lines derived from duodenum, kidney, bone marrow, and brain. Knockdown of HRG1 in the zebrafish gave profound anemia and hydrocephalus.103 Additional studies of heme-transporters initially identified in C. elegans have lead to the identification of essential heme transporters of vertebrate macrophages during erythrophagocytosis104 and intestinal heme exporter in vertebrates.105 Hence, the bloodless nematode is an important model organism that can be utilized to examine the conserved pathways of eukaryotic heme transport.

Distinguishing between heme biosynthesis and iron transport in higher eukaryotic organisms is also possible by using small molecules that autonomously perform protein-like functions106. Recently, Grillo et al. identified hinokitiol (CAS #499-44-5, PubChem CID 3611), a small hydrophobic beta-hydroxyketone originally isolated from the Taiwanese hinoki tree, that can bind and deliver iron into cells (Fig. 7).107 Hinokitiol is a potent iron chelator with lipophilic properties that can be utilized to elucidate endogenous iron-dependent physiological processes. This naturally occurring small molecule induced growth in yeast missing Fet3, an essential iron transport protein required for high affinity Fe2+ uptake from the cell surface.108 Hinokitiol has been adapted for treatment in mammalian cells and zebrafish to rescue defects associated with a variety of iron transporters. Using various model systems including yeast, zebrafish embryos, cultured mammalian cells, and rats, the authors demonstrated that hinokitiol can bypass critical iron uptake mechanisms including DMT1, Fpn1, and MFRN1 to restore hemoglobinization without affecting other metals, such as Mn, Co, Ni, Cu, Zn.107 Hinokitiol had no affect on cells or animals with defects in heme intermediate trafficking, indicating its specificity for primary defects in iron-transport. Biophysical experiments were designed to better understand the metallophore characteristics of hinokitiol including high affinity binding of iron from iron-citrate complexes as well as intracellular delivery of iron. X-ray crystallography revealed the iron-hinokitiol complex, which is composed of a lipophilic outer shell encasing a hydrophilic and iron-binding central core. This structure may contribute to the ability of hinokitiol to traverse the fatty plasma membrane that surrounds cells. The specific removal of iron from iron-binding proteins, including transferrin and ferritin was elucidated by measuring the uptake of 55Fe2+, a radioactive isotope of ferrous iron.107

These findings suggest an approach to examine the networks of transmembrane iron transport machinery that could also have implications for therapeutic treatment of human hematologic diseases including protoporphyria, a clinical disease characterized by the accumulation of PPIX. This rare disorder is caused by excessive elevation at toxic levels of free erythrocyte PPIX, which leads to photosensitivity of sun exposed skin and liver damage.87 Treatment for protoporphyria includes hematopoietic stem cell therapy and or orthotopic liver transplantation. However, a less invasive treatment option for specific genetic variants of protoporphyria includes iron supplementation, which was recently shown to alleviate protoporphyrin IX overload.109

Genetic variants of protoporphyria are defined by the affected enzyme. Erythropoietic protoporphyria (EPP) manifests from a deficiency of ferrochelatase, the terminal enzyme in heme synthesis that is required for ferrous iron metallation. In ferrochelatase-deficient EPP, iron cannot be incorporated into PPIX, leading to increased concentrations of protoporphyrin in erythrocytes, plasma, skin, and liver. Thus, iron supplementation would be an ineffective treatment option for ferrochelatase-deficient EPP.

Another genetic variant of protoporphyria is X-linked protoporphyria (XLPP), where the accumulation of free protoporphyrin is the result of increased activity of ALAS2.87,110,111 In this case, a gain-of-function ALAS2 mutation results in an increase in ALA production and downstream protoporphyrin IX. 111 Since ferrochelatase has normal activity in patients with XLPP, exogenous iron supplementation can convert toxic PPIX into heme by the still functional FECH and reverse the symptoms associated with XLPP. We could potentially extrapolate the treatment with hinokitiol mediated iron supplementation to the recently reported porphyria pedigree that exhibits a dominant defect in mitochondrial ClpX.100

Figure 5. Model of Substrate Recognition and Degradation by a AAA+ Protease, ClpX.

Cartoon model of substrate recognition and degradation by the ClpXP protease. ClpXP is composed of both ClpX and ClpP, which function as a hexameric unfoldase and tetradecameric peptidase, respectively. In an initial recognition step, a peptide tag in a protein substrate binds in the axial pore of the ClpX hexamer. In subsequent ATP-dependent steps, ClpX unfolds the substrate and translocates the unfolded polypeptide into the degradation chamber of ClpP for proteolysis, where it is cleaved into small peptide fragments. Reprinted with permission from Baker et al 99 and Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (Elsevier, Inc).

Acknowledgments

We thank the following for critical reading and evaluation of the chapter: Eva Buys, Jessalyn Ubellacker, Esther Obeng, Jacky Chung, David Palmieri, and Lisa van der Vorm. This chapter was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (R01 DK070838 and P01 HL032262 to B.H.P.) and the Diamond-Blackfan Anemia Foundation (to B.H.P.).

References

- 1.Ponka P. Tissue-Specific Regulation of Iron Metabolism and Heme Synthesis: Distinct Control Mechanisms in Erythroid Cells. Blood. 1997;89:1–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schultz IJ, et al. Iron and Porphyrin Trafficking in Heme Biogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:26753–26759. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R110.119503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Knutson MD. Iron Transport Proteins: Gateways of Cellular and Systemic Iron Homeostasis. J Biol Chem. 2017 doi: 10.1074/jbc.R117.786632. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Soares MP, Hamza I. Macrophages and Iron Metabolism. Immunity. 2016;44:492–504. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.02.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Korolnek T, Hamza I. Macrophages and iron trafficking at the birth and death of red cells. Blood. 2017;125:2893–2897. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-12-567776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andrews NC. Forging a field: the golden age of iron biology. Blood. 2008;112:219–230. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-077388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Camaschella C. Iron-deficiency anemia. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:1832–1843. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1401038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang AS, Enns CA. Iron Homeostasis: Recently Identified Proteins Provide Insight into Novel Control Mechanisms. J Biol Chem. 2008;284:711–715. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R800017200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gottlieb Y, et al. Physiologically aged red blood cells undergo erythrophagocytosis in vivo but not in vitro. Haematologica. 2012;97:994–1002. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2011.057620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andrews NC. When is a heme transporter not a heme transporter? When it’s a folate transporter. Cell Metab. 2007;5:5–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MacKenzie EL, et al. Intracellular iron transport and storage: from molecular mechanisms to health implications. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2008;10:997–1030. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Braymer JJ, Lill R. Iron-Sulfur Cluster Biogenesis and Trafficking in Mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 2017 doi: 10.1074/jbc.R117.787101. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rouault TA, Maio N. Biogenesis and Functions of Mammalian Iron-Sulfur Proteins in the Regulation of Iron Homeostasis and Pivotal Metabolic Pathways. J Biol Chem. 2017 doi: 10.1074/jbc.R117.789537. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richardson DR, et al. Mitochondrial iron trafficking and the integration of iron metabolism between the mitochondrion and cytosol. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:10775–10782. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912925107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen C, Paw BH. Cellular and mitochondrial iron homeostasis in vertebrates. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1823:1459–1467. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coffey R, Ganz T. Iron homeostasis an anthropocentric perspective. J Biol Chem. 2017 doi: 10.1074/jbc.R117.781823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kautz L, Nemeth E. Molecular liaisons between erythropoiesis and iron metabolism. Blood. 2014;124:479–482. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-05-516252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Girelli D, et al. Hepcidin in the diagnosis of iron disorders. Blood. 2016;127:2809–2813. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-12-639112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Donovan A, et al. Positional cloning of zebrafish ferroportin1 identifies a conserved vertebrate iron exporter. Nature. 2000;403:776–781. doi: 10.1038/35001596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muckenthaler MU, et al. A Red Carpet for Iron Metabolism. Cell. 2017;168:344–361. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.12.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ohgami RS, et al. Identification of a ferrireductase required for efficient transferrin-dependent iron uptake in erythroid cells. Nat Genet. 2005;37:1264–1269. doi: 10.1038/ng1658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gunshin H, et al. Cloning and characterization of a mammalian proton-coupled metal-ion transporter. Nature. 1997;388:482–488. doi: 10.1038/41343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fleming MD, et al. Microcytic anaemia mice have a mutation in Nramp2, a candidate iron transporter gene. Nat Genet. 1997;16:383–386. doi: 10.1038/ng0897-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen C, et al. Snx3 regulates recycling of the transferrin receptor and iron assimilation. Cell Metab. 2013;17:343–352. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lim JE, et al. A mutation in Sec15l1 causes anemia in hemoglobin deficit (hbd) mice. Nat Genet. 2005;37:1270–1273. doi: 10.1038/ng1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lim JE, et al. A Mutation in Sec15l1 Disrupts the Transferrin Cycle and Causes Anemia in Hemoglobin Deficit (hbd) Mice. Blood. 2005;106:513. doi: 10.1038/ng1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leidgens S, et al. Each member of the poly-r(C)-binding protein 1 (PCBP) family exhibits iron chaperone activity toward ferritin. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:17791–17802. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.460253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shi H, et al. A cytosolic iron chaperone that delivers iron to ferritin. Science. 2008;320:1207–1210. doi: 10.1126/science.1157643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ryu MS, et al. PCBP1 and NCOA4 regulate erythroid iron storage and heme biosynthesis. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:1786–1797. doi: 10.1172/JCI90519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nandal A, et al. Activation of the HIF Prolyl Hydroxylase by the Iron Chaperones PCBP1 and PCBP2. Cell Metab. 2011;14:647–657. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frey AG, et al. Iron Chaperones PCBP1 and PCBP2 Mediate the Metallation of the Dinuclear Iron Enzyme Deoxyhypusine Hydroxylase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:8031–8036. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1402732111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Philpott CC, Ryu MS. Special delivery: distributing iron in the cytosol of mammalian cells. Front Pharmacol. 2014;5:173. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2014.00173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Philpott CC, et al. Cytosolic Iron Chaperones: Proteins delivering iron cofactors in the cytosol of mammalian cells. J Biol Chem. 2017 doi: 10.1074/jbc.R117.791962. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Philpott CC. Coming into view: eukaryotic iron chaperones and intracellular iron delivery. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:13518–13523. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R111.326876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sheftel AD, et al. Direct interorganellar transfer of iron from endosome to mitochondrion. Blood. 110:125–132. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-01-068148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hamdi A, et al. Erythroid cell mitochondria receive endosomal iron by a “kiss-and-run” mechanism. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1863:2859–2867. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2016.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shaw GC, et al. Mitoferrin is essential for erythroid iron assimilation. Nature. 2006;440:96–100. doi: 10.1038/nature04512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Troadec MB, et al. Targeted deletion of the mouse Mitoferrin1 gene: from anemia to protoporphyria. Blood. 2011;117:5494–5502. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-11-319483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chung J, et al. Iron regulatory protein-1 protects against mitoferrin-1-deficient porphyria. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:7835–7843. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.547778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kosman DJ. Molecular mechanisms of iron uptake in fungi. Mol Microbiol. 2003;47:1185–1197. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Philpott CC. Iron Uptake in Fungi: A System for Every Source. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1763:636–645. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Philpott CC, et al. Fungal Physiology: Robbing the Bank of Haem Iron. Nat Microbiol. 2016;1:16179. doi: 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Paradkar PN, et al. Regulation of mitochondrial iron import through differential turnover of mitoferrin 1 and mitoferrin 2. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:1007–1016. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01685-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Amigo JD, et al. Identification of distal cis-regulatory elements at mouse mitoferrin loci using zebrafish transgenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:1344–1356. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01010-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Huang J, et al. Dynamic Control of Enhancer Repertoires Drives Lineage and Stage-Specific Transcription during Hematopoiesis. Dev Cell. 2016;36:9–23. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen W, et al. Ferrochelatase forms an oligomeric complex with mitoferrin-1 and Abcb10 for erythroid heme biosynthesis. Blood. 2010;116:628–630. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-12-259614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chen W, et al. Abcb10 physically interacts with mitoferrin-1 (Slc25a37) to enhance its stability and function in the erythroid mitochondria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:1623–1628. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904519106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shirihai OS, et al. ABC-me: a novel mitochondrial transporter induced by GATA-1 during erythroid differentiation. EMBO J. 2000;19:2492–2502. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.11.2492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Katsumura KR, et al. The GATA Factor Revolution in Hematology. Blood. 2017;15:2092–2102. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-09-687871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Crispino JD, Horwitz MS. GATA factor mutations in hematologic disease. Blood. 2017;129:2103–2110. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-09-687889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bresnick EH, et al. Master regulatory GATA transcription factors: mechanistic principles and emerging links to hematologic malignancies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:5819–5831. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Arosio P, Levi S. Cytosolic and mitochondrial ferritins in the regulation of cellular iron homeostasis and oxidative damage. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1800:783–792. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2010.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tosha T, et al. The ferritin Fe2 site at the diiron catalytic center controls the reaction with O2 in the rapid mineralization pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:18182–18187. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805083105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Levi S, et al. A human mitochondrial ferritin encoded by an intronless gene. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:24437–40. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100141200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Quigley JG, et al. Identification of a human heme exporter that is essential for erythropoiesis. Cell. 2004;118:757–766. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Keel SB, et al. A heme export protein is required for red blood cell differentiation and iron homeostasis. Science. 2008;319:825–828. doi: 10.1126/science.1151133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chiabrando D, et al. The mitochondrial heme exporter FLVCR1b mediates erythroid differentiation. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:4569–4579. doi: 10.1172/JCI62422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mercurio S, et al. The heme exporter Flvcr1 regulates expansion and differentiation of committed erythroid progenitors by controlling intracellular heme accumulation. Haematologica. 2015;100:720–729. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2014.114488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang Z, et al. Kinetics and specificity of feline leukemia virus subgroup C receptor (FLVCR) export function and its dependence on hemopexin. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:28874–28882. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.119131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ponka P, et al. Do Mammalian Cells Really Need to Export and Import Heme? Trends Biochem Sci. 2017;42:395–406. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2017.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rouault TA. Biogenesis of iron-sulfur clusters in mammalian cells: new insights and relevance to human disease. Dis Model Mech. 2012;5:155–164. doi: 10.1242/dmm.009019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bekri S, et al. Human ABC7 transporter: gene structure and mutation causing X-linked sideroblastic anemia with ataxia with disruption of cytosolic iron-sulfur protein maturation. Blood. 2000;96:3256–3264. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shimada Y, et al. Cloning and chromosomal mapping of a novel ABC transporter gene (hABC7), a candidate for X-linked sideroblastic anemia with spinocerebellar ataxia. J Hum Genet. 1998;43:115–122. doi: 10.1007/s100380050051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Levi S, Rovida E. The role of iron in mitochondrial function. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1790:629–636. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2008.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yien YY, et al. Mitochondrial transport of protoporphyrin IX in erythroid cells. Oncotarget. 2015;6:20742–20743. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.5124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Guernsey DL, et al. Mutations in mitochondrial carrier family gene SLC25A38 cause nonsyndromic autosomal recessive congenital sideroblastic anemia. Nature Genetics. 2009;41:651–653. doi: 10.1038/ng.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fernández-Murray JP, et al. Glycine and Folate Ameliorate Models of Congenital Sideroblastic Anemia. PLOS Genetics. 2016;12:1005783. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1005783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lunetti P, et al. Characterization of Human and Yeast Mitochondrial Glycine Carriers with Implications for Heme Biosynthesis and Anemia. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:19746–19759. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.736876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hunter GA, Ferreira GC. 5-aminolevulinate synthase: catalysis of the first step of heme biosynthesis. Cell Mol Biol. 2009;55:102–110. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bishop DF, et al. Human delta-aminolevulinate synthase: assignment of the housekeeping gene to 3p21 and the erythroid-specific gene to the X chromosome. Genomics. 1990;7:207–214. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(90)90542-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Layer G, et al. Structure and function of enzymes in heme biosynthesis. Protein Science. 2010;19:1137–1161. doi: 10.1002/pro.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kardon JR, et al. Mitochondrial ClpX Activates a Key Enzyme for Heme Biosynthesis and Erythropoiesis. Cell. 2015;161:858–867. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Krishnamurthy PC, et al. Identification of a mammalian mitochondrial porphyrin transporter. Nature. 2006;443:586–589. doi: 10.1038/nature05125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Helias V, et al. ABCB6 is dispensable for erythropoiesis and specifies the new blood group system Langereis. Nat Genet. 2012;44:170–173. doi: 10.1038/ng.1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hamza I, Dailey HA. One ring to rule them all: trafficking of heme and heme synthesis intermediates in the metazoans. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1823:1617–1632. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nilsson R, et al. Discovery of genes essential for heme biosynthesis through large-scale gene expression analysis. Cell Metab. 2009;10:119–130. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yien YY, et al. TMEM14C is required for erythroid mitochondrial heme metabolism. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:4294–4304. doi: 10.1172/JCI76979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chiabrando D, et al. Heme and erythropoiesis: more than a structural role. Haematologica. 2014;99:973–983. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2013.091991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Doty RT, et al. Coordinate expression of heme and globin is essential for effective erythropoiesis. J Clin Invest. 2015;125:681–4691. doi: 10.1172/JCI83054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Anderson CP, et al. Mammalian iron metabolism and its control by iron regulatory proteins. Biochem Biophys Acta. 2012;1823:1468–1483. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rouault TA. The role of iron regulatory proteins in mammalian iron homeostasis and disease. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:406–414. doi: 10.1038/nchembio807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wingert RA, et al. Deficiency of glutaredoxin 5 reveals Fe-S clusters are required for vertebrate haem synthesis. Nature. 2005;436:1035–1039. doi: 10.1038/nature03887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Oexle H, et al. Iron-dependent changes in cellular energy metabolism: influence on citric acid cycle and oxidative phosphorylation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1413:99–107. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(99)00088-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Narahari J, et al. The Aconitase Function of Iron Regulatory Protein 1. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:16227–16234. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M910450199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ye H, et al. Glutaredoxin 5 deficiency causes sideroblastic anemia by specifically impairing heme biosynthesis and depleting cytosolic iron in human erythroblasts. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:1749–1761. doi: 10.1172/JCI40372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Camaschella C. The human counterpart of zebrafish shiraz shows sideroblastic-like microcytic anemia and iron overload. Blood. 2007;110:1353–1358. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-072520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Puy H, et al. Porphyrias. Lancet. 2010;375:924–937. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61925-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rankin EB, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor-2 (HIF-2) regulates heaptic erythropoietin in vivo. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1068–1077. doi: 10.1172/JCI30117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bigham AW, Lee FS. Human high-altitude adaptation: forward genetics meets the HIF pathway. Genes Dev. 2014;28:2189–2204. doi: 10.1101/gad.250167.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Anderson SA, et al. The IRP1-HIF-2α axis coordinates iron and oxygen sensing with erythropoiesis and iron absorption. Cell Metab. 2013;17:282–290. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ghosh MC, et al. Deletion of Iron Regulatory Protein 1 Causes Polycythemia and Pulmonary Hypertension in Mice through Translational De-repression of HIF2α. Cell Metab. 17:271–281. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Appelhoff RJ, et al. Differential function of the prolyl hydroxylases PHD1, PHD2, and PHD3 in the regulation of hypoxia-inducible factor. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:38458–38465. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406026200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Marro S, et al. Heme controls ferroportin1 (FPN1) transcription involving Bach1, Nrf2 and a MARE/ARE sequence motif at position −7007 of the FPN1 promoter. Haematologica. 2010;95:1261–1268. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2009.020123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Anderson ER, et al. Intestinal HIF2α promotes tissue-iron accumulation in disorders of iron overload with anemia. PNAS. 2013;110:4922–4930. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1314197110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Mastrogiannaki M, et al. The gut in iron homeostasis: role of HIF-2 under normal and pathological conditions. Blood. 2013;122:885–892. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-11-427765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Shah YM, et al. Hypoxia-Inducible Factors Link Iron Homeostasis and Erythropoiesis. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:630–642. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.12.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kubota Y, et al. Novel Mechanisms for Heme-dependent Degradation of ALAS1 Protein as a Component of Negative Feedback Regulation of Heme Biosynthesis. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:20516–20529. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.719161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hanson PI, Whiteheart SW. AAA+ proteins: have engine, will work. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:519–529. doi: 10.1038/nrm1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Baker TA, Sauer RT. ClpXP, an ATP-powered unfolding and protein-degradation machine. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1823:15–28. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Yien YY, et al. A dominant mutation in mitochondrial unfoldase CLPX results in elevated protoporphyrin IX and causes erythropoietic protoporphyria. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017 in press. [Google Scholar]

- 101.Schneider-Poetsch T, et al. Inhibition of Eukaryotic Translation Elongation by Cycloheximide and Lactimidomycin. Nat Chem Biol. 2010;6:209–217. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Rao AU, et al. Lack of heme synthesis in a free-living eukaryote. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:4270–4275. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500877102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Rajagopal A, et al. Haem homeostasis is regulated by the conserved and concerted functions of HRG-1 proteins. Nature. 2008;453:1127–1131. doi: 10.1038/nature06934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.White C, et al. HRG1 Is Essential for Heme Transport From the Phagolysosome of Macrophages During Erythrophagocytosis. Cell Metab. 2013;17:261–270. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Korolnek T, et al. Control of metazoan heme homeostasis by a conserved multidrug resistance protein. Cell Metab. 2014;19:1008–1019. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Cioffi AG, et al. Restored Physiology in Protein-Deficient Yeast by a Small Molecule Channel. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:10096–10099. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b05765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Grillo AS, et al. Restored iron transport by a small molecule promotes absorption and hemoglobinization in animals. Science. 2017;356:608–616. doi: 10.1126/science.aah3862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.De Silva DM, et al. The FET3 Gene Product Required for High Affinity Iron Transport in Yeast Is a Cell Surface Ferroxidase. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:1098–1101. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.3.1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Landefeld C, et al. X-linked protoporphyria: Iron supplementation improves protoporphyrin overload, liver damage and anaemia. Br J Haematol. 2015;173:482–484. doi: 10.1111/bjh.13612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Whatley SD, et al. C-terminal deletions in the ALAS2 gene lead to gain of function and cause X-linked dominant protoporphyria without anemia or iron overload. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;83:408–414. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Dailey HA, Meissner PN. Erythroid heme biosynthesis and its disorders. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2013;3:011676. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a011676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]