Abstract

Objectives. To assess whether voting patterns in the 2016 US presidential election were correlated with long-run trends in county life expectancy.

Methods. I examined county-level voting data from the 2008 and 2016 presidential elections and assessed Donald Trump’s share of the 2016 vote, change in the Republican vote share between 2008 and 2016, and changes in absolute numbers of Democratic and Republican votes. County-level estimates of life expectancy at birth were obtained for 1980 and 2014 from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation.

Results. Changes in county life expectancy from 1980 to 2014 were strongly negatively associated with Trump’s vote share, with less support for Trump in counties experiencing greater survival gains. Counties in which life expectancy stagnated or declined saw a 10-percentage-point increase in the Republican vote share between 2008 and 2016.

Conclusions. Residents of counties left out from broader life expectancy gains abandoned the Democratic Party in the 2016 presidential election. Since coming to power, the Trump administration has proposed cuts to health insurance for the poor, social programs, health research, and environmental and worker protections, which are key determinants of population health. Health gaps likely will continue to widen without significant public investment in population health.

The election of Donald Trump was fueled in part by a sense of disenfranchisement and economic marginalization. However, economic indicators do not fully capture the divergence in well-being across the United States. To what extent did voting patterns map onto growing health divides? Life expectancy gaps across US counties have widened in the past 3 decades, with many counties increasingly left behind.1–4 I assessed the association between changes in county life expectancy from 1980 to 2014 and voting patterns in the 2008 and 2016 presidential elections.

METHODS

County-level voting data from the 2008 and 2016 presidential elections were obtained from the Atlas of US Presidential Elections,5 which aggregates data from state electoral commissions. I assessed Trump’s share of the 2016 vote, the change in the Republican vote share between 2008 and 2016, and changes in absolute numbers of Democratic and Republican votes. I chose 2008 as the comparison year because it was the most recent presidential election with no incumbent. Votes for third-party candidates were excluded. County-level estimates of life expectancy at birth were obtained for 1980 and 2014 from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, the longest time series of county life expectancy estimates publicly available.4,6 The change in life expectancy was calculated as the difference between 1980 and 2014 life expectancies, capturing the period described in recent studies of county health disparities.4,7

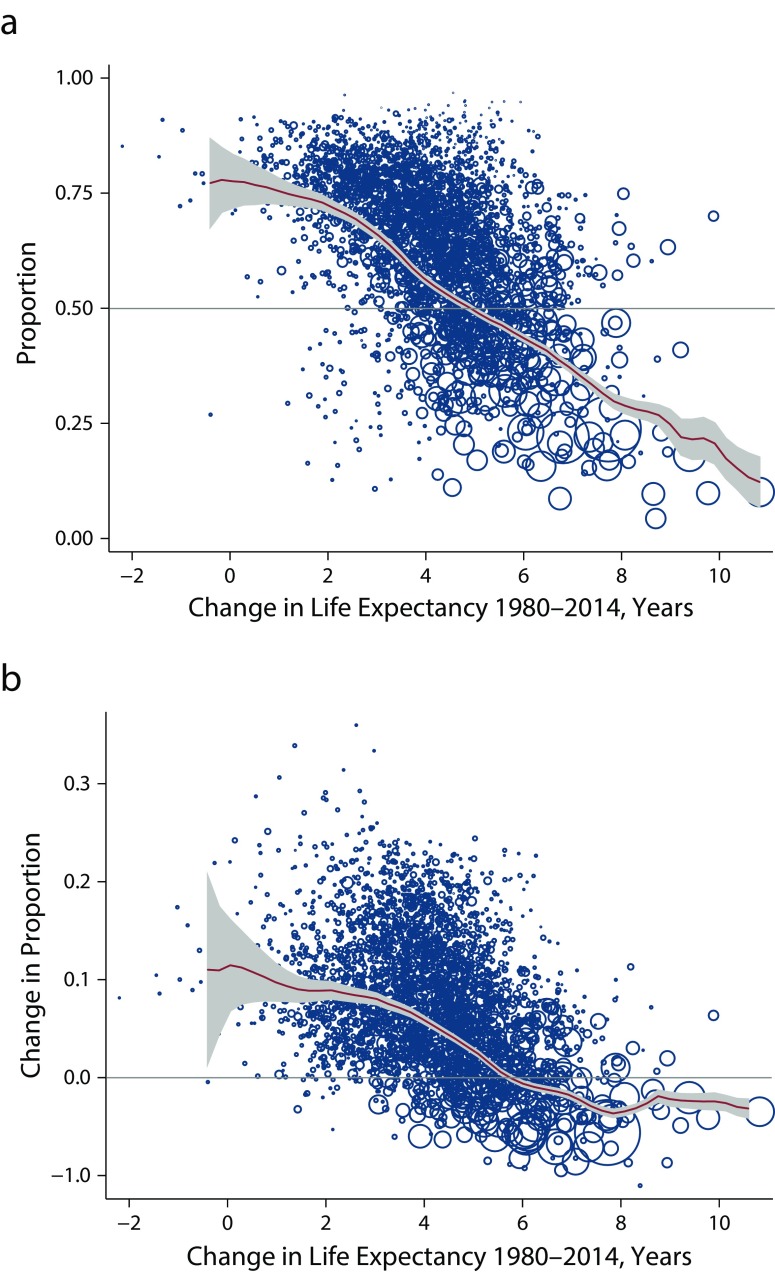

Associations between changes in life expectancy and voting patterns were assessed graphically and in multivariable regression, adjusting for county demographic and economic characteristics: state, rural/metropolitan, percentage with a college degree, income inequality, unemployment, median home value, share in poverty, economic mobility, percentage Black, and percentage Hispanic.2 Figure 1 displays scatterplots, with circles representing the size of the 2016 voting population in each county and moving averages with 95% confidence intervals.

FIGURE 1—

Change in County Life Expectancy at Birth From 1980 to 2014 and: (a) Proportion of County Votes Cast for Donald Trump in the 2016 US Presidential Election and (b) Change in Republican Vote Share From 2008 to 2016

Note. Data points are US counties, with the size of each circle proportional to the 2016 voting population. The fitted lines are moving averages with 95% confidence intervals, weighted to represent the voting population.

Source. Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation6 and Atlas of US Presidential Elections.5

RESULTS

Voters in counties in which life expectancy stagnated or declined between 1980 and 2014 were much more likely to vote for Trump (Figure 1a). Nationally, life expectancy increased by 5.3 years during this period. In counties with below-average gains in life expectancy, a majority of voters chose Trump; in counties with above-average gains in life expectancy, most voters chose Hillary Clinton. The weighted correlation between the change in life expectancy and the proportion voting for Trump was −0.67 (P < .001).

These patterns do not just represent long-run differences in party affiliation. Figure 1b displays the change in the county vote share for the Republican candidate between 2008 (John McCain vs Barack Obama) and 2016 (Trump vs Clinton). The 781 counties in which life expectancy increased by less than 3 years during 1980 through 2014 saw a 9.1-percentage-point increase in the Republican vote share. Democrats saw a 3.5-percentage-point increase in vote share in counties in which life expectancy gains exceeded 7 years. In a regression context, for each additional year of life expectancy gain, the change in Republican vote share was 2.3 percentage points lower (95% CI = −2.6, −2.0). Adjusting for state fixed effects, rural status, percentage college educated, county economic characteristics, and racial/ethnic composition reduced the estimate of the coefficient to zero (Table A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). These findings suggest that the change in life expectancy was not an independent causal factor in the shift in Republican vote share. Nevertheless, residents of many counties voting for Trump have been left out of the broader life expectancy gains of the past 3 decades.

The change in vote share reflects both changes in voter turnout and changes in preferences among those who cast votes. Overall, from 2008 to 2016, Republicans lost 67 000 votes in counties with above-average life expectancy trends but gained 3.1 million votes in counties with below-average life expectancy trends. During the same period, Democrats gained 1.4 million votes in counties with above-average life expectancy gains but also lost 5.0 million votes in counties with below-average life expectancy gains—a 14% relative decline in the number of Democratic votes in those counties. The total number of votes for the 2 major parties increased by 1.3 million in counties with above-average life expectancy gains and fell by 1.9 million in counties with below-average life expectancy gains. In counties with low survival gains, the number of votes lost by the Democrats exceeded the number of votes gained by the Republicans.

DISCUSSION

Residents of counties left out from broader life expectancy gains abandoned the Democratic Party in the 2016 presidential election, turning to Trump or not voting at all. Residents of these counties are hurting, experiencing not just economic insecurity, but also persistently high mortality rates, highlighting the need for real material investments in population health and its determinants. These findings are consistent with prior reports that voting behaviors were correlated with a broad index of poor health and the rising opioid epidemic.8 Factors implicated in diverging life expectancy across US counties include widening gaps in economic opportunity,9 changing burdens of chronic disease risk factors,4 the emergence of the opioid epidemic,10 and disparities in access to medical care.11 An important limitation of this analysis is that comparisons across counties ignore differences in life expectancy trends—and voting patterns—among population groups within counties (e.g., by race/ethnicity) that are rendered invisible by aggregation.

PUBLIC HEALTH IMPLICATIONS

Life expectancy has stagnated or declined in many US counties, even as other counties have experienced large gains in survival. Will the Trump administration and Republican Congress enact policies that improve population health in the counties where their voters reside? In its opening months, the new administration has proposed massive cuts to health insurance for the poor, to social programs such as food stamps, to public health and medical research, to occupational safety monitoring, and to environmental protection (https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/whitehouse.gov/files/omb/budget/fy2018/budget.pdf and https://www.nytimes.com/2017/05/22/us/politics/trump-budget-cuts.html). Health gaps are likely to continue to widen without public investment in the conditions that support population health.7

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Financial support was received from the Peter T. Paul Career Development Professorship.

HUMAN PARTICIPANT PROTECTION

This study did not require institutional review board approval because it did not involve human participants.

Footnotes

See also Erwin, p. 1533.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ezzati M, Friedman AB, Kulkarni SC, Murray CJL. The reversal of fortunes: trends in county mortality and cross-county mortality disparities in the United States [published correction appears in PLoS Med. 2008;5(5):e119] PLoS Med. 2008;5(4):e66. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chetty R, Stepner M, Abraham S et al. The association between income and life expectancy in the United States, 2001-2014. JAMA. 2016;315(16):1750–1766. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.4226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Currie J, Schwandt H. Inequality in mortality decreased among the young while increasing for older adults, 1990–2010. Science. 2016;352(6286):708–712. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dwyer-Lindgren L, Bertozzi-Villa A, Stubbs RW et al. Inequalities in life expectancy among US counties, 1980 to 2014. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;43(4):983–988. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.0918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leip D. Atlas of US presidential elections. 2016. Available at: http://uselectionatlas.org. Accessed May 30, 2016.

- 6.Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. US data for download. Available at: http://www.healthdata.org/us-health/data-download. Accessed May 30, 2016.

- 7.Bor J, Cohen G, Galea S. Population health in an era of rising income inequality, United States, 1980–2015. Lancet. 2017;389(10077):1475–1490. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30571-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Monnat SM. Deaths of Despair and Support for Trump in the 2016 Presidential Election. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University, Department of Agricultural Economics, Sociology, and Education; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Venkataramani AS, Chatterjee P, Kawachi I, Tsai AC. Economic opportunity, health behaviors, and mortality in the United States. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(3):478–484. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Case A, Deaton A. Rising morbidity and mortality in midlife among white non-Hispanic Americans in the 21st century. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(49):15078–15083. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1518393112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Griffith G, Evans L, Bor J. The Affordable Care Act reduced socioeconomic disparities in health care access. Health Aff (Millwood) 2017;36(8):10.1377. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]