Abstract

Female-factor infertility can be caused by poor oocyte quality and depleted ovarian reserves. Egg precursor cells (EPCs), isolated from the ovarian cortex, have the potential to be used to overcome female infertility. We aimed to define the origins of EPCs by analyzing their gene expression profiles and mtDNA content using a mini-pig model. We characterized FAC-sorted DDX4+-derived porcine EPCs by performing RNA-sequencing and determined that they utilize pathways important for cell cycle and proliferation, which supports the existence of adult mitotically active oogonial cells. Expression of the pluripotent markers Sox2 and Oct4, and the primitive germ cell markers Blimp1 and Stella were not detected. However, Nanog and Ddx4 were expressed, as were the primitive germ cell markers Fragilis, c-Kit and Tert. Moreover, porcine EPCs expressed self-renewal and proliferation markers including Myc, Esrrb, Id2, Klf4, Klf5, Stat3, Fgfr1, Fgfr2 and Il6st. The presence of Zp1, Zp2, Zp3 and Nobox were not detected, indicating that porcine EPCs are not indicative of mature primordial oocytes. We performed mitochondrial DNA Next Generation Sequencing and determined that one mtDNA variant harbored by EPCs was present in oocytes, preimplantation embryos and somatic tissues over three generations in our mini-pig model indicating the potential germline origin of EPCs.

Keywords: egg precursor cells, oogonial stem cells, mitochondrial DNA, mitochondrial supplementation, ageing oocyte

INTRODUCTION

An increasing number of women are delaying childbirth, and, since oocyte quality declines dramatically after 35 years of age [1, 2], more women are requiring assisted reproductive treatments. Male-factor infertility can be overcome by a technique called intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), which directly injects a sperm into an oocyte, and is one of the most widely used treatments in the fertility clinic [3]. On the other hand, treatment for female-factor infertility is often restricted to in vitro fertilization, since ICSI does not appear to be an effective treatment for poor quality oocytes [4].

The quality of mitochondria and the numbers of copies of its genome, mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), in oocytes are beginning to be considered, along with other factors, as indicators of oocyte quality, especially in the context of aging [5–11]. The mitochondrial genome is a highly conserved genome, which, at ∼16.6kb in size, encodes 37 of the genes that are important for functional electron transport chains that generate the vast majority of cellular ATP through oxidative phosphorylation [12, 13]. Whilst naïve, undifferentiated cells, such as pluripotent stem cells, possess a few hundred copies of mtDNA, terminally differentiated cells with high energy demands, such as neurons and cardiac muscles, possess several thousand copies [14, 15].

Low levels of mtDNA have been observed in cohorts of oocytes from couples with female-factor infertility where the oocytes fail to fertilize or arrest during pre-implantation development [7, 8, 16]. Moreover, there is evidence to suggest that this is an age-linked phenomenon as mtDNA copy number declines in oocytes with the advancement of age [17, 18]. In a pig model, we have observed mtDNA-deficiency where fertilizable oocytes have >150,000 copies of mtDNA [19, 20]. Conversely, metaphase II oocytes that are mtDNA-deficient have <100,000 copies of mtDNA, and are less likely to fertilize, or when they do they are more likely to arrest during preimplantation embryo development [19–21]. However, we have recently shown that mtDNA-deficient oocytes can be rescued by supplementation with genetically identical mitochondria, an approach known as mICSI (mitochondrial supplementation as ICSI is preformed) [22]. To this extent, blastocyst quality was significantly improved and global gene expression profiles of the resultant blastocysts closely matched those of mtDNA-normal blastocysts [22], demonstrating the beneficial effects of mitochondrial supplementation to mtDNA-deficient oocytes. Furthermore, mtDNA deficiency is not just restricted to oocytes. It has been reported in premature ovarian failure [23], ovarian insufficiency [8] and diminished ovarian reserve [24].

The number of oocytes that a female possesses, commonly known as her ovarian reserve, is generally considered to be determined at birth [25]. However, recent reports have shown the existence of mitotically active ovarian stem cells in the post-natal ovaries of mice, humans and pigs [26–28]. They are frequently referred to as egg precursor cells (EPCs) and oogonial stem cells, and have been proposed to be a source of cells to repopulate the ovary in the cases of ovarian failure. Furthermore, these cells have been used in a similar approach to mICSI, as a source of mitochondria, that has recently led to the birth of babies [29]. However, the isolation protocol for EPCs remains controversial [30–33]. Although these cells have been shown to generate fertilizable oocytes [27], and have been used to produce live offspring [34, 35], it is highly important to reproduce this protocol and characterize the resultant cells in different mammalian species in order to determine their suitability for use in assisted reproductive technologies.

The exact origins of EPCs still remains to be determined. Germ cell development is initiated from a small population of precursor cells known as primordial germ cells (PGCs), that initially express Fragilis (Ifitm3) followed by the expression of Blimp1 (or Prdm1) and Stella (or Dppa3) [36, 37], which proliferate and migrate to the genital ridge during early embryo development [38]. Specified and migratory PGCs express Ddx4 (or Vasa) and Dazl [38–40], as well as the core pluripotency genes Oct4, Sox2 and Nanog [37, 38].

At the beginning of oogenesis, PGC possess ∼200 copies of mtDNA, which then increase to ∼2000 copies, and these are clonally replicated to reach maximal copy number in the maturing oocyte [41–43]. Consequently, any mtDNA sequence variants could be amplified to varying levels in the mature oocyte and persist into adult tissues, which we have observed in our mini-pig model [21], as this is the source of all mtDNA that is inherited in a strictly maternal fashion [44]. Whilst, pathogenic mtDNA sequence variants may lead to poor oocyte quality, many non-pathogenic variants, along with wild-type mtDNA, are likely to be transmitted across generations [21].

In the present work, we have used our established mini-pig model [21] to characterize EPCs to determine the suitability of using these cells for mitochondrial supplementation to improve oocyte quality and for transplantation into the ovary to enhance the ovarian reserve of women with low ovarian reserve, or those having undergone chemotherapy, and require ovarian transplantation. We have used the mini-pig as a model, as its embryology, development, organ systems and physiological and pathophysiological responses are more similar to those of the human than the more commonly used murine models for biomedical and pre-clinical studies [45, 46]. We used an RNA-sequencing approach to characterize EPCs, and performed in-depth analysis of mtDNA sequence variants using next-generation sequencing to determine the origins of these cells. Our work provides further insight into mammalian ovarian biology, which is important for the understanding of female fertility and ovarian ageing.

RESULTS

Comparison of the gene expression profiles amongst porcine, human and mouse mitotically active germ cells

In order to determine whether porcine EPCs expressed germ cell markers, we isolated putative porcine EPCs from ovarian cortex tissue and sorted the cells using an antibody specific to the DDX4 protein. In all, five cohorts of EPCs derived from the same maternal lineage were cultured for one week without passage and then underwent RNA-sequencing. We then compared their gene expression profiles with porcine PGCs, and human and mouse mitotically active germ cells that we had identified from the literature. Here, we determined that Interferon induced transmembrane protein 3 (Ifitm3, also known as Fragilis) is expressed across EPCs, porcine PGCs [47], human mitotically active germ cells [27, 48], putative porcine ovarian stem cells [28], and mouse germ line stem cells [49, 50] (Table 1). We also report that EPCs, porcine PGCs and human mitotically active germ cells expressed Telomerase reverse transcriptase (Tert) [27, 47, 48], which is important for stem cell self-renewal. PR/SET domain 1 (Prdm1, also known as Blimp1) and Developmental pluripotency-associated 3 (Dppa3, also known as Stella) were not expressed by EPCs, although, Dppa3 was also not expressed by porcine PGCs [47] (Table 1).

Table 1. Comparison of marker gene expression between EPCs, porcine primordial germ cells, human mitotically active germ cells, porcine ovarian stem cells, and mouse germ line stem cells.

| Gene function | Gene code | Gene name | Porcine EPC | Porcine embryonic germ cell/primordial germ cell (Petkov 2011) [47] | Porcine ovarian putative stem cells (Bui 2014) [28] | Human mitotically active germ cells) (White 2012, Woods 2013) [27, 48] | Mouse female germ line stem cell (Xie 2014) [50] | Cultured mouse mitotically active germ cells (Imudia 2013) [49] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primitive germ cell marker | Prdm1/Blimp1 | PR/SET domain 1 | no | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Dppa3/Stella | Developmental pluripotency-associated 3 | no | no | not determined | yes | yes | yes | |

| Ifitm3/Fragilis | Interferon induced transmembrane protein 3 | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | |

| Tert | Telomerase reverse transcriptase | yes | yes | not determined | yes | not determined | not determined | |

| Commonly used germ line marker | Dazl | DAZ Homolog | no | not determined | yes | yes | yes | yes |

| Ddx4/Vasa | DEAD (Asp-Glu-Ala-Asp) box polypeptide 4 | yes* | not determined | yes | yes | not determined | yes | |

| Kit/c-kit | KIT proto-oncogene receptor tyrosine kinase | yes | yes | yes | not determined | no | not determined | |

| Adad1/Tenr | Adenosine deaminase domain containing 1 | yes | yes | not determined | not determined | not determined | not determined | |

| Sycp2 | Synaptonemal complex protein 2 | yes | yes | not determined | not determined | not determined | not determined | |

| Meiosis marker | Stra8 | Stimulated By Retinoic Acid 8 | no | not determined | not determined | not determined | not determined | yes |

| Meioc | Meiosis Specific With Coiled-Coil Domain | no | not determined | not determined | not determined | not determined | not determined | |

| Oocyte/follicle marker | Figα | Folliculogenesis Specific BHLH Transcription Factor | no | not determined | not determined | not determined | yes | not determined |

| Zp1 | Zona Pellucida glycoprotein 1 | no | not determined | no | yes | yes | not determined | |

| Zp2 | Zona Pellucida glycoprotein 2 | no | not determined | not determined | yes | No | not determined | |

| Zp3 | Zona pellucida glycoprotein 3 | no | not determined | not determined | yes | yes | not determined | |

| Nobox | NOBOX oogenesis homeobox | no | not determined | not determined | yes | no | not determined | |

| Gdf9 | Growth differentiation factor 9 | yes | not determined | no | yes | yes | not determined | |

| Core-pluripotency marker | Sox2 | SRY-Box 2 | no | no | yes | not determined | no | yes |

| Oct4 | POU Class 5 Homeobox 1 | no | no | yes | not determined | yes | yes | |

| Nanog | Homeobox Transcription Factor Nanog | yes* | no | yes | not determined | no | yes | |

| Cell proliferation/sef-renewal marker | Rex1/Zfp42 | ZFP42 Zinc Finger Protein | no | no | yes | not determined | no | not determined |

| Myc | Proto-Oncogene C-Myc | yes | yes | yes | not determined | no | not determined | |

| Esrrb | Estrogen Related Receptor Beta | yes | yes | no | not determined | no | not determined | |

| Zfx | X-Linked Zinc Finger Protein | yes | not determined | not determined | not determined | yes | not determined | |

| Id2 | Inhibitor Of Differentiation 2 | yes | yes | not determined | not determined | no | not determined | |

| Klf4 | Kruppel-Like Factor 4 | yes | yes | yes | not determined | no | not determined | |

| Klf5 | Kruppel-Like Factor 5 | yes | yes | not determined | not determined | no | not determined | |

| Tbx3 | T-Box Protein 3 | yes | no | not determined | not determined | not determined | not determined | |

| Stat3 | Signal Transducer And Activator Of Transcription 3 | yes | yes | not determined | not determined | no | not determined | |

| Fgfr1 | Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor 1 | yes | yes | not determined | not determined | no | not determined | |

| Fgfr2 | Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor 2 | yes | yes | not determined | not determined | no | not determined | |

| Lifr/Il6st | Leukemia Inhibitory Factor Receptor | yes | yes | not determined | not determined | no | not determined | |

| Pparg | Peroxisome Proliferator Activated Receptor Gamma | yes | not determined | not determined | not determined | no | not determined | |

| Cell cycle marker | Cdk1 | Cyclin-dependent kinase 1 | yes | not determined | not determined | not determined | yes | not determined |

| Cdk2 | Cyclin-dependent kinase 2 | yes | not determined | not determined | not determined | yes | not determined | |

| Rpa1 | Replication protein A1 | yes | not determined | not determined | not determined | yes | not determined | |

| Rabgap1 | RAB GTPase activating protein 1 | yes | not determined | not determined | not determined | yes | not determined | |

| App | Amyloid beta precursor protein | yes | not determined | not determined | not determined | yes | not determined |

Footnote: * indicates that gene expression was not detected by RNA-sequencing after data normalization, but was detected in RT-PCR.

We found that Ddx4 (Vasa; DEAD Asp-Glu-Ala-Asp box polypeptide 4) was expressed by EPCs, as determined by reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR) and Sanger sequencing (Supplementary Data 1A and 1B, respectively). Other commonly used germ line markers including KIT proto-oncogene receptor tyrosine kinase (Kit or c-kit), Adenosine deaminase domain containing 1 (Adad1 or Tenr) and Synaptonemal complex protein 2 (Sycp2), were expressed by both EPCs and porcine PGCs [47], which further demonstrates the similarity between these two populations (Table 1). To assess whether meiosis is initiated in EPCs, we found that Stimulated By Retinoic 8 (Stra8) is not expressed by EPCs, but is expressed in mouse mitotically active germ cells [49] (Table 1). Likewise, the meiotic marker, Meiosis Specific With Coiled-Coil Domain (Meioc) is not expressed by EPCs (Table 1). Both populations did not express oocyte markers NOBOX oogenesis homeobox (Nobox), Zona pellucida glycoproteins 1 to 3 (Zp1 to 3), or Folliculogenesis Specific BHLH Transcription Factor (Figα), and only EPCs expressed Growth differentiation factor 9 (Gdf9) [47] (Table 1). Both EPCs and porcine PGCs did not express pluripotency markers SRY-Box 2 (Sox2) or POU Class 5 Homeobox 1 (Oct4), which differs to putative pig ovarian stem cells and cultured mouse mitotically active germ cells (Table 1) [28, 49]. However, when we performed RT-PCR, we detected expression of the Homeobox Transcription Factor Nanog (Nanog) in EPCs (Table 1 and Supplementary Data 1A).

To determine the cell proliferation and self-renewal potential of EPCs, we assessed markers such as Proto-Oncogene C-Myc (Myc), Estrogen Related Receptor Beta (Esrrb), Inhibitor Of Differentiation 2 (Id2), Kruppel-Like Factor 4 (Klf4), Kruppel-Like Factor 5 (Klf5), Signal Transducer And Activator Of Transcription 3 (Stat3), Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor 1 (Fgfr1), Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor 2 (Fgfr2), and Leukemia Inhibitory Factor Receptor (Lifr), and found that they were commonly expressed by EPCs and porcine PGCs [47] (Table 1). Moreover, EPCs expressed cell cycle markers Cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (Cdk1), Cyclin-dependent kinase 2 (Cdk2), Replication protein A1 (Rpa1), RAB GTPase activating protein 1 (Rabgap1) and Amyloid beta precursor protein (App) (Table 1), which suggests that EPCs are mitotically active.

Gene ontology using the PANTHER classification system

The entire list of normalized RNA-sequencing data, which consisted of 13806 genes, was then analyzed using the “Gene List Analysis” tool, from the Gene Ontology Consortium database. Here, we report that the top five biological functions for EPCs were cellular process (GO:0009987; 3891/13175 genes), metabolic process (GO:0008152; 3640/13175 genes), localization (GO:0051179; 1066/13175 genes), cellular component organization or biogenesis (GO:0071840; 923/13175 genes), and response to stimulus (GO:0050896; 865/13175) (Supplementary Data 2A and 2B, respectively).

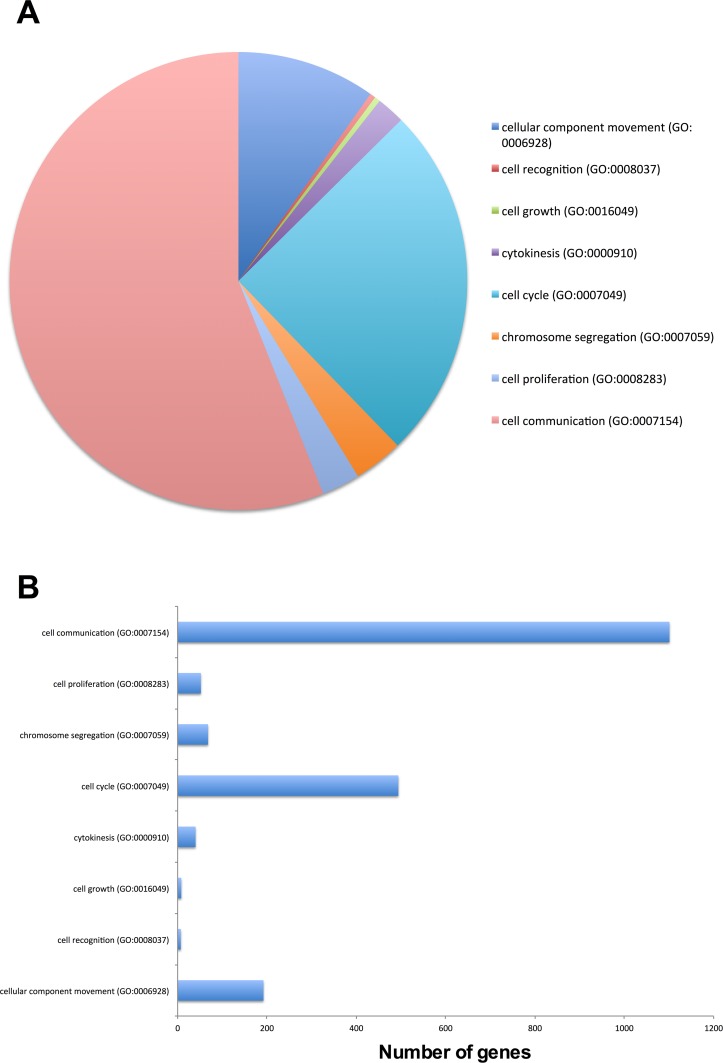

Within the cellular process category, the functions of those genes were further determined (Figure 1). The top five cellular functions (Figure 1A) and the number of genes involved (Figure 1B) were cell communication (GO:0007154; 1101/1962 genes), cell cycle (GO:0007049; 494/1962 genes), cellular component movement (GO:0006928; 192/1962 genes), chromosome segregation (GO:0007059; 68/1962 genes), and cell proliferation (GO:0008283; 52/1962 genes). Together, these data demonstrate that EPCs have the propensity to be mitotically active and proliferate.

Figure 1.

Top cellular functions of EPCs, as determined by the PANTHER classification system from the Gene Ontology Consortium database (A), and the number of genes involved (B).

Top canonical pathways and cellular functions utilized by EPCs

To further elucidate the gene expression profiles, we used another bioinformatics analytical software tool, Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA). We determined the major canonical pathways utilized by EPCs using the ‘Core analysis’ tool. The top five canonical pathways were EIF2 signaling, which plays a role in protein synthesis (P=7.30×10−45); regulation of eIF4 and p70S6K signaling, which is critical for translational regulation (P=1.43×10−34); mTOR signaling, which is involved in cell survival and proliferation (P=9.30×10−29); the protein ubiquitination pathway, which plays a role in the degradation of short lived regulatory proteins (P=6.79×10−27); and the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway, which plays a central role in signal transduction pathways of cytokines, growth factors and other extracellular matrix proteins (P=4.80×10−20) (Supplementary Data 3 and 4). These pathways are important since protein synthesis is essential for germline stem cells to continue proliferation, to differentiate or to enter apoptosis [51].

The IPA ‘Core Analysis’ tool also determined that the top molecular and cellular functions of EPCs are: cell death and survival (from 1651 genes; P=1.59×10−09 to 4.78×10−96), cellular growth and proliferation (from 1814 genes; P=5.50×10−10 to 3.42×10−84), gene expression (from 1136 genes; P=1.38×10−11 to 3.75×10−70), protein synthesis (from 526 genes; 2.03×10−13 to 1.68×10−64) and RNA post-transcriptional modification (from 222 genes; P=4.83×10−16 to 1.49×10−62). Moreover, the top predicted developmental functions are: organismal survival (from 1130 genes; P=1.49×10−14 to 1.42×10−74), embryonic development (from 837 genes; P=8.04×10−10 to 1.60×10−34), organismal development (from 1293 genes; P=1.29×10−9 to 1.60×10−34), tissue morphology (from 611 genes; P=6.84×10−10 to 1.60×10−34) and cardiovascular system development and function (from 650 genes; 1.73×10−9 to 2.09×10−28) (Supplementary Data 4). These predicted functions indicate that EPCs have the transcripts to support early embryo development.

Top gene regulation networks utilized by EPCs

The top four gene networks of that were identified by IPA to be significantly utilized (network score ≥30) were those involved in: connective tissue development, cancer, cell death and survival, and gene expression (Table 2). An important caveat for interpreting IPA network analysis is that its results mainly focus on diseases and functions. However, pathways involved in cell death and survival and cancer are also often utilized by, for example, stem cells [52]. Overall, the top eleven networks (network score ≥28), showed that EPCs utilized pathways that are important for cell morphology, cellular assembly and organization, cell to cell signaling, cell growth and proliferation, and cellular development (Table 2). These results are consistent with the top biological functions determined by PANTHER and the major canonical pathways determined by IPA.

Table 2. Top gene networks utilized by EPCs as determined by Ingenuity Pathway Analysis.

| Top diseases and functions | Molecules in network | IPA score | Focus molecules |

|---|---|---|---|

| Connective Tissue Development and Function, Developmental Disorder, Hereditary Disorder | ADRBK1, ARGLU1, C1D, CDKN2AIPNL, DCAF10, ENOPH1, ESCO1, ETFA, ETFDH, EXOSC7, EXOSC9, FAM133B, FOCAD, HEXA, HEXB, HPS5, KIAA2013, MAK16, MRPS35, NCS1, NNT, PAPD7, PAPSS1, PAPSS2, RMND5A, SLAIN2, SMC5, SMC6, SMYD5, SS18L2, TMEM132A, TSNAX, TUFT1, WAC, YPEL5 | 30 | 35 |

| Cancer, Hematological Disease, Immunological Disease | ABL1, ARL5A, ATIC, BOD1L1, CBX3, CHD4, CNBP, DDX47, DEGS1, DHX15, DPY19L1, EIF5B, FJX1, FUBP1, GART, HDGF, KDM3B, KDM5B, KPNA2, LMNB2, MTF2, NCBP1, PAICS, PLS3, PRPS1, PSIP1, RBBP4, RCOR1, RECQL, SETX, SLC16A1, STK38, SUB1, ZDHHC16, ZNF217 | 30 | 35 |

| Cell Death and Survival, Infectious Diseases, Gene Expression | AMBRA1, ANP32B, ATF7IP, BUB1, CPEB2, EEF2, ERCC3, GANAB, HSDL2, HSP90AA1, HUWE1, KCTD2, KDM4B, KIF1B, LRRC42, MACF1, MAST2, MXRA7, NANS, NUF2, PCBP1, PCMT1, PPIG, PSMA1, PSMA3, PSMC1, PSMC3, PSMC5, PSMD2, RAD23B, RALBP1, RNASEH2C, SNTB2, TFE3, TNIK | 30 | 35 |

| Gene Expression, Connective Tissue Disorders, Developmental Disorder | ACER3, ANO6, CCDC25, CDR2L, CHSY1, COQ10B, DCUN1D4, EFCAB14, ELAVL1, ERMP1, FAM105A, HECA, IER3IP1, ISOC1, MEX3D, MGAT2, PCNP, PDZD8, PEX19, PITHD1, RAP2C, S100PBP, SELT, SLC10A3, SLC18B1, SMIM7, SPPL3, TM7SF3, TMCO1, TMEM123, TMEM167B, TMEM41B, TMX1, ZNF521, ZNF664 | 30 | 35 |

| Cell Morphology, Cellular Assembly and Organization, Cellular Function and Maintenance | 60S ribosomal subunit, ABCF1, BMS1, CBY1, CEP164, DDX24, DNTTIP2, DZIP1, FRYL, GALK1, GNL2, GRK5, KIAA0930, MRTO4, MYBBP1A, NIFK, NLE1, NMD3, NSA2, OTUD4, PAK1IP1, PEF1, PTCD3, PUM3, RPF1, RPL8, RPL14, RPL26L1, RPL7L1, RRP8, RSL24D1, STAU2, USP36, UTP18, WDR3 | 28 | 34 |

| Cancer, Cell Death and Survival, Organismal Injury and Abnormalities | EBNA1BP2, GNRH, GRSF1, HAUS2, KRR1, MRPL3, MRPL24, MRPL38, MRPL40, MRPL46, MRPS6, MRPS7, MRPS9, MRPS10, MRPS22, MRPS26, MRPS27, MRPS34, NEMF, PREP, RANBP6, RPL6, RPL13, RPL15, RPL17, RPL26, RPL27, RPL34, RPL38, RPL27A, RPS8, SMIM20, SRSF9, SUCO, TRA2A | 28 | 34 |

| Cellular Assembly and Organization, Cell-To-Cell Signaling and Interaction, Reproductive System Development and Function | ACTR1B, AHI1, CCT2, CCT3, CCT4, CCT5, CCT7, CCT8, CCT6A, CIPC, DCAF7, DENND4C, DOCK5, DSP, ECD, HSF2, MAPK9, NMT1, PDCD10, Ppp2c, PPP2CB, PPP2R1A, PPP2R1B, PPP2R2A, PPP2R5C, RABGEF1, SIRT2, STK24, STK25, STRN, SUN2, TCP1, TRMT112, TXNDC9, UNC45A | 28 | 34 |

| Cardiovascular Disease, Connective Tissue Disorders, Developmental Disorder | ANKIB1, ATG2B, ATP8B2, CCDC50, CDIP1, CTTNBP2NL, DCHS1, DENR, DHRS7, FAR1, FARSA, GRAMD1A, HECTD1, ITM2B, Lamin, LRRC57, MFAP3, MRPL49, NUP155, NUTF2, OTUD7B, R3HDM4, RNF19B, RYK, SBF2, STRN4, TALDO1, TMEM59, TMEM30A, TMEM59L, TXNL1, UBC, ZDHHC20, ZFAND3, ZRANB1 | 28 | 34 |

| Cell Signaling, Gene Expression, Cellular Function and Maintenance | ACADVL, CAD, CBL, CDK9, CHD1, CNN1, DCTN3, DECR1, FLOT1, FOXP4, HMMR, KLHL12, LRPPRC, MED4, MED8, MED12, MED16, MED17, MED25, MED28, mediator, MMS19, NIPBL, OSTF1, POLR2A, QKI, RPLP2, RUVBL2, SART3, SKIV2L2, THRAP3, TRRAP, TXLNA, TXLNG, ZW10 | 28 | 34 |

| Small Molecule Biochemistry, Post-Translational Modification, Lipid Metabolism | APPBP2, BNIP3, CACFD1, Ces, COMT, CREB3, CYP51A1, DAD1, EBP, ENC1, FAM213A, FAM3A, FIS1, HSD3B1, IFRD1, IMPDH1, MFSD7, MFSD11, MSMO1, NFE2L2, NUCB2, OAF, OAT, ORMDL1, SLC39A13, SLC41A2, SPTSSA, ST3GAL4, TBC1D15, TMEM115, TMEM230, TPI1, UGGT2, UNC50, VKORC1 | 28 | 34 |

| Cell Death and Survival, Cellular Development, Cellular Growth and Proliferation | ABRACL, ANXA2, BTG3, CCPG1, CDC37, CEP290, CTNND1, CUL2, DCTN1, EWSR1, Fgf, FGF11, FUS, GLS, HLTF, MAOB, MET, NAP1L3, NRP1, PKM, PRPF19, RARA, RBPJ, RCC1, SDC1, SMARCA4, SNW1, SSB, SUZ12, TFIP11, TNC, UPF1, VCP, WRNIP1, YBX1 | 28 | 34 |

Top upstream regulators that determine EPC gene expression

Upstream regulators are master molecules that target and regulate gene expression in EPCs. We have identified these upstream molecules to provide further support to our biological function analysis. Here, we identified 477 upstream regulators that activate, and 246 that inhibit EPC gene expression (Supplementary Data 5). The activating upstream regulators, as determined by IPA, included 87 transcription regulators, 29 growth factors, 7 nuclear receptors and 24 cytokines. All regulators identified have a z-score of >2 or <2 and were ranked from the lowest to highest P-value (all <0.05) (Supplementary Data 5).

The top ten activating transcription regulators were v-myc avian myelocytomatosis viral oncogene homolog (Myc), tumor protein p53 (Tp53), hepatocyte nuclear factor 4 alpha (Hnf4a), v-myc avian myelocytomatosis viral oncogene neuroblastoma derived homolog (Mycn), X-box binding protein 1 (Xbp1), nuclear factor, erythroid 2 like 2 (Nfe2l2), hypoxia inducible factor 1 alpha subunit (Hif1a), huntingtin (Htt), E2F transcription factor 1 (E2f1), and Fos proto-oncogene, AP-1 transcription factor subunit (Fos) (Table 3). These genes are involved in the biological functions of cell proliferation, cell cycle regulation, cellular response to stress and nutrient, and maintenance of cell homeostasis (Table 3).

Table 3. Upstream regulators that positively regulate EPC gene expression as determined by Ingenuity Pathway Analysis.

| Molecule type | Upstream regulator | Biological function | No. of target genes | P-value | Z-score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transcription Regulator | MYC | Cell proliferation, cell cycle regulation | 457 | 2.32E-83 | 8.884 |

| TP53 | Cell cycle regulation | 563 | 2.23E-82 | 4.559 | |

| HNF4A | Glucose homeostasis, lipid homeostasis | 728 | 1.51E-81 | 2.167 | |

| MYCN | Cell proliferation | 165 | 2.67E-60 | 2.925 | |

| XBP1 | Cellular response to nutrient, cell growth | 124 | 5.36E-40 | 9.837 | |

| NFE2L2 | Cellular response to stress | 166 | 1.56E-26 | 11.009 | |

| HIF1A | Cellular response to hypoxia | 147 | 3.55E-20 | 8.085 | |

| HTT | Regulation of mitochondrial function | 232 | 6.71E-20 | 4.924 | |

| E2F1 | Cell cycle regulation | 168 | 9.48E-20 | 4.241 | |

| FOS | Cellular response to stimulus | 187 | 1.12E-18 | 2.507 | |

| Nuclear Receptor | ESR1 | Ovarian follicle growth | 438 | 9.49E-41 | 5.358 |

| PGR | Cellular response to gonadotropin | 110 | 1.53E-16 | 6.862 | |

| PPARG | Lipid metabolism, glucose homeostasis | 139 | 9.64E-10 | 3.756 | |

| PPARA | Glucose metabolism, fatty acid metabolism | 116 | 9.18E-06 | 4.608 | |

| AR | Cell growth and proliferation | 116 | 2.05E-05 | 6.679 | |

| ESRRA | Cell proliferation | 53 | 1.86E-04 | 5.735 | |

| ESRRG | Cell proliferation | 14 | 7.26E-03 | 3.121 | |

| Growth Factor | TGFB1 | Cell growth and proliferation, migration | 550 | 1.54E-49 | 10.924 |

| HGF | Cell proliferation migration | 180 | 8.4E-21 | 8.682 | |

| ANGPT2 | Cell differentiation, germ cell development | 85 | 2.84E-16 | 6.092 | |

| VEGFA | Cell migration, angiogenesis | 102 | 2.05E-14 | 7.275 | |

| EGF | Potent mitogenic factor | 159 | 7.61E-13 | 8.927 | |

| TGFB3 | Cell growth and proliferation | 48 | 9.23E-11 | 5.633 | |

| AGT | Extracellular matrix organization | 136 | 5.25E-10 | 7.643 | |

| IGF1 | Cellular response to insulin and glucose | 120 | 4.03E-08 | 6.814 | |

| FGF2 | Cell division and proliferation | 106 | 2.65E-07 | 6.851 | |

| KITLG | Germ cell development, ovarian follicle development | 71 | 4.97E-06 | 5.675 |

The top seven positive nuclear-receptor regulators were estrogen receptor 1 (Esr1), progesterone receptor (Pgr), peroxisome proliferator activated receptor gamma (Pparg), peroxisome proliferator activated receptor alpha (Ppara), androgen receptor (Ar), estrogen related receptor alpha (Esrra), and estrogen related receptor gamma (Esrrg). These ligand-regulated transcription factors play key roles in regulating cell growth and proliferation, lipid and glucose metabolism and follicular growth (Table 3).

The top ten growth factors were transforming growth factor beta 1 (Tgfb1), hepatocyte growth factor (Hgf), angiopoietin 2 (Angpt2), vascular endothelial growth factor A (Vegfa), epidermal growth factor (Egf), transforming growth factor beta 3 (Tgfb3), angiotensinogen (Agt), insulin like growth factor 1 (Igf1), fibroblast growth factor 2 (Fgf2), and KIT ligand (Kitlg). These growth factors are important for germ cell development, cell proliferation, cell metabolism and cell migration (Table 3).

Upstream regulatory molecules that inhibit EPC gene expression included 27 transcription regulators, 1 growth factor, 42 mature microRNAs and 27 microRNAs (Supplementary Data 5). The top ten inhibiting transcription regulators were nuclear protein 1 (Nupr1), promyelocytic leukemia (Pml), cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (Cdkn2a), Kruppel like factor 3 (Klf3), SMAD family member 7 (Smad7), lysine demethylase 5A (Kdm5a), lysine demethylase 5B (Kdm5b), SAM pointed domain containing ETS transcription factor (Spdef), interferon regulatory factor 4 (Irf4), and MAX interactor 1 (Mxi1) (Table 4). These transcription regulators are regulators of cell cycle, cell proliferation, chromatin organization and germ cell migration (Table 4). We also identified microRNAs that are likely important in the regulation of self-renewal in EPCs, specifically those that regulate Oct4, Klf4 and Myc (Table 4). Indeed, microRNAs have been reported to play regulatory roles in stem and germ cells [53].

Table 4. Upstream regulators that negatively regulate EPC gene expression as determined by Ingenuity Pathway Analysis.

| Molecule type | Upstream regulator | Biological function | No. of target genes | P-value | IPA Z-score | Reference (DOI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transcription Regulator | NUPR1 | Cell cycle | 166 | 3.09E-14 | −3.035 | IPA Knowledge database |

| PML | Regulation of the TGF-beta signaling pathway | 58 | 2.22E-12 | −3.195 | IPA Knowledge database | |

| CDKN2A | Cell cycle negative regulator | 100 | 3.37E-11 | −2.147 | IPA Knowledge database | |

| KLF3 | Multicellular organismal development | 112 | 1.48E-10 | −7.504 | IPA Knowledge database | |

| SMAD7 | Negative regulation of BMP signaling pathway, negative regulation of cell migration | 53 | 8.29E-10 | −4.682 | IPA Knowledge database | |

| KDM5A | Chromatin modification, chromatin organization | 54 | 2.02E-09 | −5.900 | IPA Knowledge database | |

| KDM5B | Chromatin modification | 55 | 3.34E-09 | −4.673 | IPA Knowledge database | |

| SPDEF | Germ cell migration | 33 | 3.00E-08 | −4.402 | IPA Knowledge database | |

| IRF4 | Interferon-gamma-mediated signaling pathway | 46 | 1.48E-04 | −4.662 | IPA Knowledge database | |

| MXI1 | Negatively regulate MYC function | 10 | 1.51E-04 | −2.919 | IPA Knowledge database | |

| Mature MicroRNA | miR-124-3p | Potential regulator of PIM1 | 118 | 1.36E-28 | −10.788 | Deng et al. 2016 (10.1111/cas.12946) |

| miR-16-5p | Potential regulator of SMAD3 | 102 | 1.23E-24 | −9.938 | Li et al. 2015 (10.2174/1381612821666150909094712) | |

| miR-1-3p | Unknown | 99 | 5.58E-24 | −9.767 | n/a | |

| let-7a-5p | Potential regulator of CCND1 and MYC | 78 | 7.77E-20 | −8.622 | Ghanbari et al. 2015 (10.4137/BIC.S25252) | |

| miR-30c-5p | Potential regulator of EIF2A | 63 | 2.14E-19 | −7.805 | Jiang et al. 2016 (10.1038/srep21565) | |

| miR-155-5p | Potential regulator of DNMT1 | 73 | 1.24E-15 | −8.437 | Zhang et al. 2015 (10.1093/nar/gkv518) | |

| miR-483-3p | Potential regulator of CDC25A | 25 | 2.50E-08 | −4.969 | Bertero et al. 2013 (10.1038/cdd.2013.5) | |

| miR-133a-3p | Potential regulator of RBPJ | 27 | 5.27E-08 | −5.065 | Huang et al. 2016 (ISSN:2156-6976/ajcr0040390/; PMID: 27904763) | |

| miR-145-5p | Potential regulator of OCT4 and KLF4 | 29 | 8.90E-08 | −5.312 | Xu et al. 2009 (10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.038) | |

| miR-29b-3p | Potential regulator of TGFB1 | 29 | 5.48E-07 | −5.260 | Lu et al. 2016 (10.1096/fj.201600722R) |

mtDNA copy number and expression of Polg

EPCs from the current work were harvested from ovaries of mini-pigs from a established colony originating from a single founder female [21], which ensures that each of the offspring inherits the same population of mtDNA. We firstly determined that the mtDNA copy number of EPCs (1131 ± 411, mean ± SEM) was significantly lower than immature oocytes (Supplementary Data 6) and is within the range for PGC mtDNA copy number [41–43, 54]. We then determined the expression levels of mitochondrial specific polymerase gamma (Polg) in mini-pig heart, muscle and EPCs, and found that EPCs express significantly fewer transcripts than heart tissues (Supplementary Data 7). These data show that EPCs maintain low mtDNA copy number, which is indicative of their naïve state.

mtDNA sequence variants harbored by the EPCs

To determine the number of positions within the mitochondrial genome that harbored a sequence variant, we performed in depth Next Generation Sequencing with >4000 times coverage. MtDNA sequence variants that were harbored between 3 to 50% were compared amongst EPCs, oocytes, 2-cell embryos, 4-cell embryos, 8-cell embryos and ovarian tissues (Table 5). Eighteen positions within the mitochondrial genome were affected, with the mean number of variants harbored by EPCs, oocytes, 2-cell embryos, 4-cell embryos, 8-cell embryos and ovarian tissues being 7.3, 2.9, 3.5, 3, 3 and 2.6, respectively (Table 5). EPCs harbored the most number of variants, whilst ovarian tissues had the least. The variant A376del was harbored by all samples and at a mean frequency of 4.6 ± 0.1% (mean ± S.E.M), as was A5188del at a mean frequency of 4.8 ± 0.08% (mean ± S.E.M). This indicates that some variants that are present at low levels can persist from oogenesis through embryo development to adulthood. Moreover, the variant T7317C was harbored only by EPCs and oocytes and this variant was harbored at relatively high frequencies. This demonstrates that EPCs and oocytes possessed a similar population of mtDNA. However, the T7317C variant is eliminated post-fertilization but persists in putative germline cells. The A1253del variant was also found across all groups, but found less frequently in EPCs (25%) compared with oocytes (65%), embryos (100%) and ovarian tissues (60%).

Table 5. Mitochondrial DNA sequence variants in EPCs, oocytes, 2-cell embryos, 4-cell embryos, 8-cell embryos and ovarian tissues.

| Position | WT | V | Gene | EPC | Immature oocytes | 2 cell | 4 cell | 8 cell | Ovarian tissue | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | A2 | A3 | A4 | L1 | L2 | L3 | L4 | L5 | L6 | L7 | L8 | L9 | L10 | L11 | L12 | L13 | L14 | L15 | L16 | L17 | E13 | E14 | E18 | E19 | E23 | E24 | O1 | O2 | O3 | O4 | O5 | ||||

| 376 | A | - | 12s RNA | 3.2 | 3.3 | 3.4 | 4.2 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 4.0 | 4.8 | 4.7 | 4.7 | 4.8 | 4.6 | 4.8 | 5.0 | 5.1 | 5.0 | 4.7 | 4.9 | 5.8 | 5.5 | 4.7 | 5.2 | 4.7 | 4.9 | 5.5 | 4.8 | 4.8 | 5.1 | 4.6 | 4.5 | 4.4 | 4.0 |

| 960 | T | C | 12s RNA | 7.0 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1253 | A | - | 16s RNA | 9.3 | 3.2 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 3.6 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 3.6 | 3.2 | 3.4 | 3.3 | 3.4 | 3.6 | 3.6 | 3.3 | 3.5 | 3.0 | 3.4 | |||||||||||

| 1497 | - | A | 16s RNA | 8.2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3256 | G | A | NADH1 | 3.8 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3495 | A | G | NADH1 | 8.8 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 4932 | C | T | NADH2 | 4.2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5188 | A | - | Origin of L-strand replication | 3.5 | 4.7 | 4.6 | 4.0 | 5.0 | 4.4 | 5.1 | 5.3 | 5.1 | 4.9 | 4.7 | 4.6 | 4.8 | 4.8 | 5.0 | 5.2 | 4.7 | 5.0 | 4.7 | 4.2 | 4.4 | 5.6 | 4.6 | 5.1 | 4.8 | 4.6 | 4.4 | 5.1 | 5.2 | 5.4 | 5.0 | 4.4 |

| 7317 | T | C | COII | 8.2 | 4.3 | 12.8 | 5.1 | 3.7 | 7.7 | 19.3 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12101 | C | T | NADH5 | 4.5 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12535 | T | A | NADH5 | 4.2 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 12860 | A | G | NADH5 | 3.4 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 15760 | T | C | Control region | 9.5 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 16022 | T | C | Control region | 3.7 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 16140 | A | G | Control region | 6.9 | 4.9 | 3.1 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 16142 | A | G | Control region | 6.7 | 4.6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 16352 | A | G | Control region | 5.0 | 7.5 | 4.6 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 16561 | A | G | Control region | 4.0 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Footnote: WT = wild type; V = variant.

We then compared the variants with those that we had previously identified in our mini-pig model [21]. The A376del was harbored by oocytes, preimplantation embryos and somatic tissues, and was maintained in our mini-pig colony over three generations, which was derived from one common maternal ancestor. Specifically, in the immature (∼10%) and mature (∼20%) oocytes and embryos (∼50%), the levels of A376del were very different. However, in somatic tissues the variant was present at low levels (<20%) across three generations in all tissues examined. This suggests that this variant is present in the germline and is regulated at different stages of development in the offspring [21].

DISCUSSION

Mitochondrial supplementation, otherwise known as mICSI, is a relatively new assisted reproductive technique that has the potential to have a significant impact on the treatment of female-factor infertility. This technique arose from the concept of ooplasmic transfer from younger to older women as a means to rescue poor quality oocytes [55]. To perform mICSI, purified mitochondria without accompanying mRNA and other cellular factors are injected into the cytoplasm of metaphase II oocytes along with the spermatozoa during the process of ICSI [22]. The technique of ICSI has been performed for nearly three decades and has led to the birth of over 2.5 million children [3]. Whilst ICSI has successfully treated male-factor infertility, especially those associated with poor or abnormal semen quality, it does not improve pregnancy outcomes for women over the age of 40 [4] or for mtDNA deficiency [22].

We have previously shown that by performing mICSI in our porcine model of mtDNA-deficient oocytes, supplementation of 800 copies of mtDNA resulted in a significant (4.4 fold) increase of mtDNA copy number at the 2-cell embryo stage [22]. This is important as it ensures sufficient copies are allocated to each blastomere as they divide [15]. Moreover, the global gene expression profiles of the resultant blastocysts from mtDNA-deficient oocytes were enhanced to resemble blastocysts derived from mtDNA-normal oocytes [22]. However, the mitochondria isolated from our previous work were derived from metaphase II oocytes. The present work assesses the suitability of utilizing EPCs for mitochondrial supplementation by determining their origins through their gene expression profiles and the mtDNA variants they harbor. As a consequence, this will also define their suitability for transplantation purposes to restore ovarian function for women with, for example, premature ovarian failure.

Here, we have cultured isolated EPCs for one week, without passage, and observed that they were not dormant and were able to proliferate under in vitro conditions. We then assessed the gene expression profiles of EPCs, and found that they shared some key markers with porcine PGCs [47]. They express primitive germ cell specific markers Fragilis [36] and Tert, which is the enzymatic component of telomerase and is highly expressed in germline stem cells [56]. The expression of Fragilis and Tert was also found in human mitotically active post-natal germ cells [27, 48]. Interestingly, Fragilis was the only primitive germ cell marker that was consistently detected in mouse and pig putative germline stem cells [28, 50]. However, we did not observe the expression of Blimp1 or Stella, which are other primitive germ cell markers [36, 57]. We argue that since Blimp1 and Stella are only expressed in a small proportion of Fragilis positive cells [36, 57], the gene expression levels in the isolated porcine EPCs may be very low. Nevertheless, the expression of Ddx4, which encodes for the evolutionarily conserved and germ cell specific VASA protein [39, 58], was detected in the EPCs, albeit at low levels.

The discovery of mitotically active ovarian stem cells has challenged the widely accepted view that the ovarian reserve is fixed at birth (approximately 1 million follicles) and cannot be renewed [25, 59, 60]. The existence of ovarian stem cells was initially reported in mice [26], and subsequently found in human ovarian cortical tissues [27]. Since then putative ovarian stem cells have been isolated by multiple groups and in several species [28, 49, 50]. Ovarian stem cells have the capacity to proliferate, differentiate to oocyte-like cells and can be fertilized to produce live offspring [27, 34, 35]. We chose to use cells that had been cultured in order to undertake our analysis on cells that had the propensity to proliferate and were not trapped in a dormant state, which is a key characteristic that we would expect from cells with the potential to give rise to more mature cell types. However, they may change their characteristics or selected for particular sub-groups.

In the present work, of the core pluripotency markers, EPCs only expressed Nanog but not Sox2 or Oct4. However, cell proliferation and self-renewal markers such as Myc, Esrrb, Zfx, Id2, Klf4, Klf5, Tbx3, Stat3, Fgfr1, Fgfr2, Lifr, and Pparg were expressed. It is important to note that expression of the pluripotency network genes varies between species, as demonstrated in human and mouse embryonic stem cells [61]. Therefore, extrapolation of results from pig, mouse and human should be taken with caution. Nevertheless, the cell cycle markers Cdk1, Cdk2, Rpa1, Rabgap1, and App were also expressed. From culturing the cells prior to RNA extraction and from PANTHER gene enrichment analysis and IPA pathway analysis, we have found that EPCs have the propensity to undergo cell proliferation and utilize canonical pathways that are important for germ cell development. This is an unexpected finding, since, after a proliferative phase, PGCs enter and arrest at the diplotene stage of prophase I of meiosis, thereby ending their proliferative capacity [38]. Moreover, we did not observe the expression of Zp1, Zp2, Zp3 or Figα, which are required for differentiation to primordial oocytes [62, 63]. Therefore, we suggest that these EPCs are undifferentiated multipotent lineage-specific oogonial cells, that could differentiate into oocytes or be dedifferentiated under the right conditions. Interestingly, one of the top canonical pathways that was utilized by the EPCs was the mTOR signaling pathway, which is important for the maintenance of embryonic stem cells and is embryonically lethal when knocked-out [64]. We have also detected the expression of c-kit, which is a protein kinase receptor responsible for the reawakening of the quiescent primordial follicle to enter follicular growth, via the PI3K-AKT pathway [65], which is one of the top canonical pathway used, demonstrating the potential of EPCs to enter follicular development.

mtDNA is clonally amplified from ∼200 copies in PGCs to >150,000 copies in metaphase II oocytes [19, 41–43, 66, 67], which represents the potential number of molecules of the mitochondrial genome available for transmission to offspring. Two or more populations of mtDNA genotypes (wild type and molecules harboring variants) can co-exit, but variants normally exist at low levels in healthy individuals [21, 68]. Indeed, numerous studies have shown that pathogenic and non-pathogenic mtDNA variants are more prevalent in humans than previously thought [68–70]. Individuals remain healthy until pathogenic mtDNA variants pass a certain threshold, whereby wild-type mtDNA can no longer compensate for defective mtDNA [44]. Therefore, to ensure that EPCs possess the same mtDNA genotypes as oocytes, for the faithful transmission of germline mtDNA to offspring during assisted reproduction, we compared mtDNA variants harbored by mini-pig EPCs, oocytes, embryos, and ovarian tissues. We found that mtDNA sequence variants A376del, A1253del and A5188del were present in all samples at low percentages. On the other hand, the T7317C variant is harbored by the EPCs and oocytes at high percentages, but was not detected in embryos or ovarian tissues. To this end, our data on A376del, A1253del and A5188del indicate that oocytes and EPCs originate from the same lineage during early development and are recycled from one generation to the next as indicated by their presence in gametes, embryos and tissues. However, it appears that the T7317C variant was diluted out during embryo development [41, 43, 71].

From human studies and our mini-pig model, it has been shown that certain mtDNA variants tend to accumulate at a higher percentage in specific tissues [21, 69, 70]. In the present work, we found that the variants 1497InsA and T960C may have resulted from replication errors made by POLG [72], or were preferentially amplified during early embryo development [71], but they were not observed in the adult ovarian tissues. Only the variant A376del is consistently detected across EPCs, oocytes, embryos, as well as somatic tissues such as ovarian tissues, heart and brain [21], which suggests that this variant arose from the germline and is maintained in both germ cells and somatic tissues. Nevertheless, we found that the de novo acquisition of mtDNA variants is not very common in our mini-pig model. Therefore, our results indicate that EPCs harbor variants that originated from the germline. In addition, we suggest that it is important to faithfully transmit those variants to offspring, since they may be advantageous during development, and/or for maintaining natural genetic variation in the population [21]. Whilst mouse models possessing two genetically divergent non-pathogenic mtDNA genotypes have perturbed physiological functions [73], the exact role of endogenous non-pathogenic mtDNA variants is still unclear. Furthermore, our mini-pig model is not known to carry any mitochondrial disease causing mutations.

Accumulation of mtDNA variant load is associated with aging and other age-related disorders [44, 74]. There is also evidence to suggest that mtDNA variant load increases in oocytes and cumulus cells of women over the age of 35 [9, 75, 76]. To this end, EPCs represent an ideal population of cells for mitochondrial isolation to be used in the clinic, as they are genetically identical to the patient and harbor a low percentage of mtDNA variants. Since the proportion of mtDNA variants has been shown to increase in culture after each passage [77], we cultured the EPCs for one week without passage. This is beneficial for clinical applications, as a proportion of the viable EPCs could be used to screen for pathogenic mtDNA variants prior to mICSI. In this respect, EPCs are also a source of “ovarian stem cells”, or for generating “oocyte-like cells” to be used for ovarian transplantation. We found that mtDNA copy number of EPCs is within the previously reported range for PGCs [41–43]. This suggests that the mitochondria they reside in have low mitochondrial metabolic activity, as is the case for stem-like cells that primarily rely on glycolysis for energy production [78]. Furthermore, in agreement with our copy number data, EPCs express significantly fewer Polg transcripts compared with heart tissues.

In conclusion, we have characterized the gene expression profiles of EPCs by RNA-sequencing and performed gene enrichment analysis and pathway analysis to determine that EPCs possess proliferative and self-renewal capacity. The main aim of the current study was to determine whether EPCs are a suitable source to harvest naïve mitochondria to be used in mitochondrial supplementation during mICSI. We have achieved this aim by showing that EPCs possess mtDNA variants that are distinctive to the germline lineage. This unique population of cells could be used for in vitro maturation or ovarian transplantation to allow women with low ovarian reserve and/or hormone sensitivity to conceive. Furthermore, characterization of ovarian stem cells is important for our fundamental understanding of ovarian biology and the process of ovarian ageing.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal ethics approval

Tissues obtained from mini-pigs were excess to requirement. Animals were euthanized in accordance with animal ethics guidelines. Approval for the use of animals was granted by Monash Medical Centre Animal Ethics Committee A, approval number MMCA/2012/84.

Preparation of ovarian cortical strips from porcine tissue

Porcine ovaries were transported to the laboratory in sterile phosphate buffered saline (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, U.S.A), and maintained at ∼38°C. Ovaries were cut in half lengthways and transferred to a sterile 10 cm dish containing phosphate buffered saline with penicillin and streptomycin. Avoiding the central cortex area, bisected ovaries were cut into thin slices using a carbon steel single edge razor blade. A size 10 or 11 scalpel blade was used to cut the ovary slices into strips, and then each strip was cut into small pieces. Approximately 30 pieces of ovarian tissue were washed and transferred to a cryovial containing 1ml of sterile, 90% FBS/10% DMSO freezing solution to be frozen overnight at −80°C, then transferred to LN2 tank for storage.

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting

Porcine ovarian cortex tissue was digested and processed into a single cell suspension, based on methods described previously [48]. In brief, cells were resuspended and blocked in 2% human serum albumin (HSA) in HBSS (without Mg2+ and Ca2+) for 20 min at room temperature with agitation followed by an incubation with Alexa Fluor® 647-conjugated anti-DDX4 antibody (HuMab DDX4) for 20 min at room temperature (in the dark) at a concentration of 10 μg per million cells per 100 μl. The cell suspension was washed by centrifugation in HBSS (without Mg2+ and Ca2+) followed by incubation with SYTOX® green dead cell stain (Cat # S34860, ThermoFisher) at 30 μM for 20 min at room temperature with agitation (in the dark). For each experiment, an aliquot of unstained cells was used as the negative threshold and gating control. Labeled cells were filtered (35 μm pore diameter) and subjected to analysis on an SH800 flow cytometer with the manufacturer's SH800 software (Sony Biotechnology Inc., San Jose, CA, USA). Freshly isolated DDX4 positive viable cells (EPCs) were collected and frozen in cryopreservation buffer.

Porcine EPC culture

The cells derived from porcine ovarian cortical strips were cultured in EPC media consisting of DMEM, supplemented with 10% FBS (heat inactivated), 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 1 mM nonessential amino acids, 1X penicillin-streptomycin-glutamine, 0.1 mM β-mercaptoethanol (all ThermoFisher Scientific), 103 units/ml ESGRO leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF), 10 ng/ml recombinant human epidermal growth factor (rhEGF), 1 ng/ml basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), 40 ng/ml glial cell-derived neurotropic factor (GDNF; all Merck Millipore) and 1X N-2 MAX supplement (R & D Systems). On thawing, cells were plated at a density of 2.5 × 104 /cm2 in EPC media at 39°C and 5% CO2 with media changes every 2 days. Once confluent, cells were lysed directly in the wells, lysates collected, snap frozen in LN2 and stored at −80°C until processed further for RNA extraction using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen), as per manufacturer's instructions.

RNA library preparation and sequencing

Library preparation was performed using the TruSeq RNA v2 (Illumina, CA, USA) protocol. Briefly, mRNA was purified using oligo(dT) beads, and then fragmented. The 1st strand cDNA synthesis was randomly primed followed by 2nd strand cDNA synthesis. Sequencing adaptors were ligated and the library was amplified by PCR. RNA sequencing was performed on a HiSeq 3000 (Illumina). Sequencing data were deposited in the sequence read archive (SRA) in NCBI under the project number PRJNA374593.

RNA sequencing bioinformatics analysis

46 ± 0.9 (mean ± S.E.M) million paired reads were obtained from RNA sequencing. Read quality was determined by the Illumina quality score, with >92% bases above Q30 across all five samples. Adaptor and overrepresented sequences were removed before the sequence reads were aligned to the pig reference genome (NCBI version: GCF_000003025.5_Sscrofa10.2). Using the Stringtie tool v 1.0.4, 79.7 ± 0.4 (mean ± S.E.M) % of the paired reads were mapped to the Sus scrofa exons. Data normalization was performed using edgeR. 13,808 normalized and annotated genes were identified. To determine the overall functions of EPCs, normalized RNA-Sequencing data were analyzed using the PANTHER classification system (http://www.pantherdb.org/) [79]. Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA) (QIAGEN Redwood City, www.giagen.com/ingenguity, fall 2016 release), which is a web-based application, was used to determine pathways utilized by the EPCs. “Commonly Expressed Genes” tool was applied to the dataset (n = 5) to identify common genes. A further cutoff of 5-log ratio was applied and 4391 genes were used for pathway analysis to identify highly expressed genes.

Real time PCR for estimation of mtDNA copy number

Each PCR reaction consisted of 2 μL of template DNA, 10μL of 2x SensiMix (Bioline), 1 μL of 5 μM of each forward (5′-CTCAACCCTAGCAGAAACCA-3′) and reverse primer (5′-TTAGTTGGTCGTATCGGAATCG-3′), and 6 μL of ultrapure ddH20, performed in a Rotergene-3000 real time PCR machine (Corbett Research, Cambridge, UK). A series of 10-fold dilutions (1 ng/μL to 1x 10-8 ng/μL) was used as the known standards. mtDNA quantification was determined from the standard curve, and mtDNA copy number was calculated based on the PCR product length.

Reverse transcriptase PCR

RNA from oocytes, blastocysts and EPCs was isolated using the ARCTURUS® PicoPure® RNA Isolation Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific), as per manufacturer's instructions. First strand cDNA synthesis was performed using the qScript Flex cDNA kit (Quantabio, MA, U.S.A), according to manufacturer's protocol. The resultant cDNA was used to amplify target genes by PCR (Primer sequences; Supplementary Table 1). The expression of Ddx4 was confirmed by Sanger sequencing using a previously described protocol [66].

mtDNA amplification and purification

The whole mitochondrial genome from EPC isolates (n=4), immature oocytes (n=17), 2-cell embryos (n=2), 4-cell embryos (n=2), 8-cell embryos (n=2) and ovarian tissues (n=5) were amplified by long PCR, as previously described [66]. Briefly, 40 ng DNA, with 1× High Fidelity PCR buffer, 100 mM MgSO4, 1 mM dNTPs (Bioline), 1U of Platinum Taq High Fidelity (Invitrogen, CA, USA) and 10 μM of each forward and reverse primer (Primer sequences; Supplementary Table 1). PCR products were separated on a 0.7% agarose gel and purified using the QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen, West Sussex, UK).

Whole mitochondrial genome sequencing

The DNA concentration of purified long PCR products was determined by Qubit® dsDNA HS Assay kit (Invitrogen). For each sample, equal amounts of DNA were pooled from PCR product A and B (∼5 ng combined). DNA shearing was performed by sonication using the S220 Focused-ultrasonicator (Covaris, MA, USA) to generate a mean library size of ∼400 bp. Libraries were prepared with Ovation Ultralow system V2 (protocol M01380v1) (Nugen, CA, USA). 14 cycles of amplification were performed. Sequencing was performed using the 250 bp paired-end chemistry on the Illumina MiSeq v2 platform with PhiX spike-in for technical control. The MiSeq run generated a total of 22.8 million reads that passed filter. Each of the four samples generated 785,599 ± 22390 (mean ± S.E.M) reads.

Identification of mtDNA sequence variants

Two FASTQ files for each sample were imported into CLC Genomics Workbench v9.5.1 for quality trimming. Duplicate reads were removed before the remaining reads were mapped to a reference pig mitochondrial genome AJ002189 [12] to generate a representative sequence. Read sequences were then mapped to the representative sequence without masking, with an insertion and deletion cost of 3 and minimum of 80% identity to the representative sequence. The low frequency variant detection tool was used to determine the level of sequence variants. Variant calling was made using the following parameters: 3% minimum threshold, presence of variant on forward and reverse reads. Each variant identified, had a minimum count of 140, within minimum sequence coverage of 4000.

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism v6.0f (GraphPad Software, Inc., CA, USA). mtDNA copy number between EPCs and immature oocytes was compared using Mann-Whitney test. Polg expression amongst EPCs, and heart and muscle tissues was compared using ordinary one-way ANOVA followed by Dunn's multiple comparisons test.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS TABLE

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Lori McPartlin (OvaScience, Inc.) for technical assistance with FACS sorting.

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

YW is an employee and stock holder of OvaScience Inc. Ovascience did not fund or influence the content of the manuscript. TT, JJ and JCSJ declare no conflicts of interest.

FUNDING

The work was funded by The Hudson Special Projects Fund and the Victorian Government's Operational Infrastructure Support Program.

Author contributions

TT performed Next Generation Sequencing analysis, participated in the design of the experiment, performed molecular analysis and wrote the manuscript. JJ performed cell culture and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. YW performed FAC sorting and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. JCSJ conceived the work, designed and coordinated the experiments, analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Navot D, Bergh PA, Williams MA, Garrisi GJ, Guzman I, Sandler B, Grunfeld L. Poor oocyte quality rather than implantation failure as a cause of age-related decline in female fertility. Lancet. 1991;337:1375–1377. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)93060-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balasch J. Ageing and infertility: an overview. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2010;26:855–860. doi: 10.3109/09513590.2010.501889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Steirteghem A. Celebrating ICSI's twentieth anniversary and the birth of more than 2.5 million children--the ‘how, why, when and where’. Hum Reprod. 2012;27:1–2. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tannus S, Son WY, Gilman A, Younes G, Shavit T, Dahan MH. The role of intracytoplasmic sperm injection in non-male factor infertility in advanced maternal age. Hum Reprod. 2017;32:119–124. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dew298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilding M. Potential long-term risks associated with maternal aging (the role of the mitochondria) Fertil Steril. 2015;103:1397–1401. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keefe DL, Niven-Fairchild T, Powell S, Buradagunta S. Mitochondrial deoxyribonucleic acid deletions in oocytes and reproductive aging in women. Fertil Steril. 1995;64:577–583. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Santos TA, El Shourbagy S, St John JC. Mitochondrial content reflects oocyte variability and fertilization outcome. Fertil Steril. 2006;85:584–591. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.May-Panloup P, Chrétien MF, Jacques C, Vasseur C, Malthièry Y, Reynier P. Low oocyte mitochondrial DNA content in ovarian insufficiency. Hum Reprod. 2005;20:593–597. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rebolledo-Jaramillo B, Su M, Stoler N, McElhoe JA, Dickins B, Blankenberg D, Korneliussen TS, Chiaromonte F, Nielsen R, Holland MM. Maternal age effect and severe germ-line bottleneck in the inheritance of human mitochondrial DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:15474–15479. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1409328111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Van Blerkom J. Mitochondria in early mammalian development. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2009;20:354–364. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Saben JL, Boudoures AL, Asghar Z, Thompson A, Drury A, Zhang W, Chi M, Cusumano A, Scheaffer S, Moley KH. Maternal metabolic syndrome programs mitochondrial dysfunction via germline changes across three generations. Cell Rep. 2016;16:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.05.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ursing BM, Arnason U. The complete mitochondrial DNA sequence of the pig (Sus scrofa) J Mol Evol. 1998;47:302–306. doi: 10.1007/pl00006388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anderson S, Bankier AT, Barrell BG, de Bruijn MH, Coulson AR, Drouin J, Eperon IC, Nierlich DP, Roe BA, Sanger F, Schreier PH, Smith AJ, Staden R, Young IG. Sequence and organization of the human mitochondrial genome. Nature. 1981;290:457–465. doi: 10.1038/290457a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kelly RD, Mahmud A, McKenzie M, Trounce IA, St John JC. Mitochondrial DNA copy number is regulated in a tissue specific manner by DNA methylation of the nuclear-encoded DNA polymerase gamma A. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:10124–10138. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.St John J. The control of mtDNA replication during differentiation and development. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2014;1840:1345–1354. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.10.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reynier P, May-Panloup P, Chrétien MF, Morgan CJ, Jean M, Savagner F, Barrière P, Malthièry Y. Mitochondrial DNA content affects the fertilizability of human oocytes. Mol Hum Reprod. 2001;7:425–429. doi: 10.1093/molehr/7.5.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murakoshi Y, Sueoka K, Takahashi K, Sato S, Sakurai T, Tajima H, Yoshimura Y. Embryo developmental capability and pregnancy outcome are related to the mitochondrial DNA copy number and ooplasmic volume. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2013;30:1367–1375. doi: 10.1007/s10815-013-0062-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chan CC, Liu VW, Lau EY, Yeung WS, Ng EH, Ho PC. Mitochondrial DNA content and 4977 bp deletion in unfertilized oocytes. Mol Hum Reprod. 2005;11:843–846. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gah243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spikings EC, Alderson J, St John JC. Regulated mitochondrial DNA replication during oocyte maturation is essential for successful porcine embryonic development. Biol Reprod. 2007;76:327–335. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.106.054536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.El Shourbagy SH, Spikings EC, Freitas M, St John JC. Mitochondria directly influence fertilisation outcome in the pig. Reproduction. 2006;131:233–245. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.00551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cagnone G, Tsai TS, Srirattana K, Rossello F, Powell DR, Rohrer G, Cree L, Trounce IA, St John JC. Segregation of naturally occurring mitochondrial DNA variants in a mini-pig model. Genetics. 2016;202:931–944. doi: 10.1534/genetics.115.181321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cagnone GL, Tsai TS, Makanji Y, Matthews P, Gould J, Bonkowski MS, Elgass KD, Wong AS, Wu LE, McKenzie M, Sinclair DA, St John JC. Restoration of normal embryogenesis by mitochondrial supplementation in pig oocytes exhibiting mitochondrial DNA deficiency. Sci Rep. 2016;6:23229. doi: 10.1038/srep23229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pagnamenta AT, Taanman JW, Wilson CJ, Anderson NE, Marotta R, Duncan AJ, Bitner-Glindzicz M, Taylor RW, Laskowski A, Thorburn DR, Rahman S. Dominant inheritance of premature ovarian failure associated with mutant mitochondrial DNA polymerase gamma. Hum Reprod. 2006;21:2467–2473. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boucret L, Chao de la Barca JM, Morinière C, Desquiret V, Ferré-L'Hôtellier V, Descamps P, Marcaillou C, Reynier P, Procaccio V, May-Panloup P. Relationship between diminished ovarian reserve and mitochondrial biogenesis in cumulus cells. Hum Reprod. 2015;30:1653–1664. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dev114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Faddy MJ, Gosden RG, Gougeon A, Richardson SJ, Nelson JF. Accelerated disappearance of ovarian follicles in mid-life: implications for forecasting menopause. Hum Reprod. 1992;7:1342–1346. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a137570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnson J, Canning J, Kaneko T, Pru JK, Tilly JL. Germline stem cells and follicular renewal in the postnatal mammalian ovary. Nature. 2004;428:145–150. doi: 10.1038/nature02316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.White YA, Woods DC, Takai Y, Ishihara O, Seki H, Tilly JL. Oocyte formation by mitotically active germ cells purified from ovaries of reproductive-age women. Nat Med. 2012;18:413–421. doi: 10.1038/nm.2669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bui HT, Van Thuan N, Kwon DN, Choi YJ, Kang MH, Han JW, Kim T, Kim JH. Identification and characterization of putative stem cells in the adult pig ovary. Development. 2014;141:2235–2244. doi: 10.1242/dev.104554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fakih MH, Shmoury M, Szeptycki J, Cruz DB, Lux C, Verjee S, Burgess CM, Cohn GM, Casper RF. The AUGMENT SM Treatment: physician reported outcomes of the initial global patient experience. JFIV Reprod Med Genet. 2015;3:154. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hernandez SF, Vahidi NA, Park S, Weitzel RP, Tisdale J, Rueda BR, Wolff EF. Characterization of extracellular DDX4- or Ddx4-positive ovarian cells. Nat Med. 2015;21:1114–1116. doi: 10.1038/nm.3966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang H, Panula S, Petropoulos S, Edsgard D, Busayavalasa K, Liu L, Li X, Risal S, Shen Y, Shao J, Liu M, Li S, Zhang D, et al. Adult human and mouse ovaries lack DDX4-expressing functional oogonial stem cells. Nat Med. 2015;21:1116–1118. doi: 10.1038/nm.3775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zarate-Garcia L, Lane SI, Merriman JA, Jones KT. FACS-sorted putative oogonial stem cells from the ovary are neither DDX4-positive nor germ cells. Sci Rep. 2016;6:27991. doi: 10.1038/srep27991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yuan J, Zhang D, Wang L, Liu M, Mao J, Yin Y, Ye X, Liu N, Han J, Gao Y, Cheng T, Keefe DL, Liu L. No evidence for neo-oogenesis may link to ovarian senescence in adult monkey. Stem Cells. 2013;31:2538–2550. doi: 10.1002/stem.1480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zou K, Yuan Z, Yang Z, Luo H, Sun K, Zhou L, Xiang J, Shi L, Yu Q, Zhang Y, Hou R, Wu J. Production of offspring from a germline stem cell line derived from neonatal ovaries. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:631–636. doi: 10.1038/ncb1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu C, Xu B, Li X, Ma W, Zhang P, Chen X, Wu J. Tracing and characterizing the development of transplanted female germline stem cells in vivo. Mol Ther. 2017;25:1408–1419. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2017.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saitou M, Barton SC, Surani MA. A molecular programme for the specification of germ cell fate in mice. Nature. 2002;418:293–300. doi: 10.1038/nature00927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hayashi K, de Sousa Lopes SM, Surani MA. Germ cell specification in mice. Science. 2007;316:394–396. doi: 10.1126/science.1137545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nikolic A, Volarevic V, Armstrong L, Lako M, Stojkovic M. Primordial germ cells: current knowledge and perspectives. Stem Cells Int. 2016;2016:1741072. doi: 10.1155/2016/1741072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Castrillon DH, Quade BJ, Wang TY, Quigley C, Crum CP. The human VASA gene is specifically expressed in the germ cell lineage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:9585–9590. doi: 10.1073/pnas.160274797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kee K, Angeles VT, Flores M, Nguyen HN, Reijo Pera RA. Human DAZL, DAZ and BOULE genes modulate primordial germ-cell and haploid gamete formation. Nature. 2009;462:222–225. doi: 10.1038/nature08562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cree LM, Samuels DC, de Sousa Lopes SC, Rajasimha HK, Wonnapinij P, Mann JR, Dahl HH, Chinnery PF. A reduction of mitochondrial DNA molecules during embryogenesis explains the rapid segregation of genotypes. Nat Genet. 2008;40:249–254. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wai T, Teoli D, Shoubridge EA. The mitochondrial DNA genetic bottleneck results from replication of a subpopulation of genomes. Nat Genet. 2008;40:1484–1488. doi: 10.1038/ng.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cao L, Shitara H, Horii T, Nagao Y, Imai H, Abe K, Hara T, Hayashi J, Yonekawa H. The mitochondrial bottleneck occurs without reduction of mtDNA content in female mouse germ cells. Nat Genet. 2007;39:386–390. doi: 10.1038/ng1970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wallace DC, Chalkia D. Mitochondrial DNA genetics and the heteroplasmy conundrum in evolution and disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013;5:a021220. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a021220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Humpherson PG, Leese HJ, Sturmey RG. Amino acid metabolism of the porcine blastocyst. Theriogenology. 2005;64:1852–1866. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2005.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bode G, Clausing P, Gervais F, Loegsted J, Luft J, Nogues V, Sims J, Steering Group of the RETHINK Project The utility of the minipig as an animal model in regulatory toxicology. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 2010;62:196–220. doi: 10.1016/j.vascn.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Petkov SG, Marks H, Klein T, Garcia RS, Gao Y, Stunnenberg H, Hyttel P. In vitro culture and characterization of putative porcine embryonic germ cells derived from domestic breeds and Yucatan mini pig embryos at Days 20-24 of gestation. Stem Cell Res. 2011;6:226–237. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Woods DC, Tilly JL. Isolation, characterization and propagation of mitotically active germ cells from adult mouse and human ovaries. Nat Protoc. 2013;8:966–988. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Imudia AN, Wang N, Tanaka Y, White YA, Woods DC, Tilly JL. Comparative gene expression profiling of adult mouse ovary-derived oogonial stem cells supports a distinct cellular identity. Fertil Steril. 2013;100:1451–1458. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.06.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xie W, Wang H, Wu J. Similar morphological and molecular signatures shared by female and male germline stem cells. Sci Rep. 2014;4:5580. doi: 10.1038/srep05580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Friday AJ, Keiper BD. Positive mRNA translational control in germ cells by initiation factor selectivity. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:327963. doi: 10.1155/2015/327963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Reya T, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF, Weissman IL. Stem cells, cancer, and cancer stem cells. Nature. 2001;414:105–111. doi: 10.1038/35102167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Virant-Klun I, Stahlberg A, Kubista M, Skutella T. MicroRNAs: from female fertility, germ cells, and stem cells to cancer in humans. Stem Cells Int. 2016;2016:3984937. doi: 10.1155/2016/3984937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cao L, Shitara H, Sugimoto M, Hayashi JI, Abe K, Yonekawa H. New evidence confirms that the mitochondrial bottleneck is generated without reduction of mitochondrial DNA content in early primordial germ cells of mice. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000756. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cohen J, Scott R, Schimmel T, Levron J, Willadsen S. Birth of infant after transfer of anucleate donor oocyte cytoplasm into recipient eggs. Lancet. 1997;350:186–187. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)62353-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ravindranath N, Dalal R, Solomon B, Djakiew D, Dym M. Loss of telomerase activity during male germ cell differentiation. Endocrinology. 1997;138:4026–4029. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.9.5488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ohinata Y, Payer B, O'Carroll D, Ancelin K, Ono Y, Sano M, Barton SC, Obukhanych T, Nussenzweig M, Tarakhovsky A. Blimp1 is a critical determinant of the germ cell lineage in mice. Nature. 2005;436:207–213. doi: 10.1038/nature03813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fujiwara Y, Komiya T, Kawabata H, Sato M, Fujimoto H, Furusawa M, Noce T. Isolation of a DEAD-family protein gene that encodes a murine homolog of Drosophila vasa and its specific expression in germ cell lineage. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:12258–12262. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.25.12258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Telfer EE, Albertini DF. The quest for human ovarian stem cells. Nat Med. 2012;18:353–354. doi: 10.1038/nm.2699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Byskov AG, Hoyer PE, Yding Andersen C, Kristensen SG, Jespersen A, Mollgard K. No evidence for the presence of oogonia in the human ovary after their final clearance during the first two years of life. Hum Reprod. 2011;26:2129–2139. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ginis I, Luo Y, Miura T, Thies S, Brandenberger R, Gerecht-Nir S, Amit M, Hoke A, Carpenter MK, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Rao MS. Differences between human and mouse embryonic stem cells. Dev Biol. 2004;269:360–380. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gook DA, Edgar DH, Borg J, Martic M. Detection of zona pellucida proteins during human folliculogenesis. Hum Reprod. 2008;23:394–402. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liang L, Soyal SM, Dean J. FIGalpha, a germ cell specific transcription factor involved in the coordinate expression of the zona pellucida genes. Development. 1997;124:4939–4947. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.24.4939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Murakami M, Ichisaka T, Maeda M, Oshiro N, Hara K, Edenhofer F, Kiyama H, Yonezawa K, Yamanaka S. mTOR is essential for growth and proliferation in early mouse embryos and embryonic stem cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:6710–6718. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.15.6710-6718.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Saatcioglu HD, Cuevas I, Castrillon DH. Control of oocyte reawakening by kit. PLoS Genet. 2016;12:e1006215. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tsai TS, Rajasekar S, St John JC. The relationship between mitochondrial DNA haplotype and the reproductive capacity of domestic pigs (Sus scrofa domesticus) BMC Genet. 2016;17:67. doi: 10.1186/s12863-016-0375-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jansen RP, de K. The bottleneck: mitochondrial imperatives in oogenesis and ovarian follicular fate. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 1998;145:81–88. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(98)00173-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ye K, Lu J, Ma F, Keinan A, Gu Z. Extensive pathogenicity of mitochondrial heteroplasmy in healthy human individuals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:10654–10659. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1403521111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Samuels DC, Li C, Li B, Song Z, Torstenson E, Boyd Clay H, Rokas A, Thornton-Wells TA, Moore JH, Hughes TM, Hoffman RD, Haines JL, Murdock DG, et al. Recurrent tissue-specific mtDNA mutations are common in humans. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003929. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Elliott HR, Samuels DC, Eden JA, Relton CL, Chinnery PF. Pathogenic mitochondrial DNA mutations are common in the general population. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;83:254–260. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Johnston IG, Burgstaller JP, Havlicek V, Kolbe T, Rulicke T, Brem G, Poulton J, Jones NS. Stochastic modelling, Bayesian inference, and new in vivo measurements elucidate the debated mtDNA bottleneck mechanism. Elife. 2015;4:e07464. doi: 10.7554/eLife.07464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Otten AB, Stassen AP, Adriaens M, Gerards M, Dohmen RG, Timmer AJ, Vanherle SJ, Kamps R, Boesten IB, Vanoevelen JM, Muller M, Smeets HJ. Replication errors made during oogenesis lead to detectable de novo mtDNA mutations in zebrafish oocytes with a low mtDNA copy number. Genetics. 2016;204:1423–1431. doi: 10.1534/genetics.116.194035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sharpley MS, Marciniak C, Eckel-Mahan K, McManus M, Crimi M, Waymire K, Lin CS, Masubuchi S, Friend N, Koike M, Chalkia D, MacGregor G, Sassone-Corsi P, Wallace DC. Heteroplasmy of mouse mtDNA is genetically unstable and results in altered behavior and cognition. Cell. 2012;151:333–343. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ross JM, Stewart JB, Hagström E, Brené S, Mourier A, Coppotelli G, Freyer C, Lagouge M, Hoffer BJ, Olson L, Larsson NG. Germline mitochondrial DNA mutations aggravate ageing and can impair brain development. Nature. 2013;501:412–415. doi: 10.1038/nature12474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Barritt JA, Cohen J, Brenner CA. Mitochondrial DNA point mutation in human oocytes is associated with maternal age. Reprod Biomed Online. 2000;1:96–100. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)61946-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]