Abstract

pH has been recognized as one of the key environmental parameters with significant impacts on the nitrogen cycle in the environment. In this study, the effects of pH on NO3–/NO2– fate and N2O emission were examined with Shewanella loihica strain PV-4, an organism with complete denitrification and respiratory ammonification pathways. Strain PV-4 was incubated at varying pH with lactate as the electron donor and NO3–/NO2– and N2O as the electron acceptors. When incubated with NO3– and N2O at pH 6.0, transient accumulation of N2O was observed and no significant NH4+ production was observed. At pH 7.0 and 8.0, strain PV-4 served as a N2O sink, as N2O concentration decreased consistently without accumulation. Respiratory ammonification was upregulated in the experiments performed at these higher pH values. When NO2– was used in place of NO3–, neither growth nor NO2– reduction was observed at pH 6.0. NH4+ was the exclusive product from NO2– reduction at both pH 7.0 and 8.0 and neither production nor consumption of N2O was observed, suggesting that NO2– regulation superseded pH effects on the nitrogen-oxide dissimilation reactions. When NO3– was the electron acceptor, nirK transcription was significantly upregulated upon cultivation at pH 6.0, while nrfA transcription was significantly upregulated at pH 8.0. The highest level of nosZ transcription was observed at pH 6.0 and the lowest at pH 8.0. With NO2– as the electron acceptor, transcription profiles of nirK, nrfA, and nosZ were statistically indistinguishable between pH 7.0 and 8.0. The transcriptions of nirK and nosZ were severely downregulated regardless of pH. These observations suggested that the kinetic imbalance between N2O production and consumption, but neither decrease in expression nor activity of NosZ, was the major cause of N2O accumulation at pH 6.0. The findings also suggest that simultaneous enhancement of nitrogen retention and N2O emission reduction may be feasible through pH modulation, but only in environments where C:N or NO2–:NO3– ratio does not exhibit overarching control over the NO3–/NO2– reduction pathways.

Keywords: denitrification, respiratory ammonification, nitrous oxide (N2O), pH, RT-qPCR

Introduction

Nitrous oxide (N2O) is a potent greenhouse gas ∼300 times more effective than CO2 in causing radiative forcing if present at the same concentration (Lashof and Ahuja, 1990). N2O has also been the most powerful ozone depletion agent in the atmosphere since phasing out of chlorofluorocarbons (Portmann et al., 2012). By far, the largest source of N2O is biotransformation of reactive nitrogen (e.g., NH4+, NO3–, and urea) applied as nitrogen fertilizers to agricultural soils (Ravishankara et al., 2009; Reay et al., 2012). The increase in the atmospheric concentration of N2O is strongly correlated to the increase in the global input of nitrogen fertilizers to agricultural soils (Kroeze et al., 1999; Davidson, 2009). Therefore, understanding nitrogen cycling in the environment and developing strategies for sustainable management of soil nitrogen are crucial for efforts to reduce N2O emissions.

Limiting soil denitrification by stimulating the reaction that competes with denitrification for the same substrates, NO3– or NO2–, has been proposed as a way to enhance nitrogen retention in agricultural soils (Tiedje et al., 1983; Yoon et al., 2015a). While denitrification is reduction of NO3–/NO2– to N2O and N2 via NO, respiratory ammonification (also called dissimilatory nitrate/nitrite reduction to ammonium or DNRA) reduces NO3–/NO2– to NH4+, the form of nitrogen with higher tendency to be retained in pore water or adsorbed to negatively charged particle surfaces (Laima et al., 1999; Silver et al., 2001; Fitzhugh et al., 2003). Recent advances in microbial ecology have identified the environmental parameters that control the competition between denitrification and respiratory ammonification through experiments using axenic cultures or enrichment cultures (Kraft et al., 2014; van den Berg et al., 2015; Yoon et al., 2015a,b). In chemostat experiments with Shewanella loihica strain PV-4, electron acceptor limitation due to the high C:N ratio of the feed medium favored the dominance of respiratory ammonification over denitrification (Yoon et al., 2015a). Enrichment of microorganisms capable of DNRA upon electron acceptor limitation was observed in a similar experiment using wastewater as the inoculum (van den Berg et al., 2016). Although contrasting observations were reported, NO2–:NO3– ratios also factored into selection of the NO3–/NO2– reduction pathways in two independent experiments carried out by different research groups (Kraft et al., 2014; Yoon et al., 2015b).

pH is an important environmental parameter with significant impacts on many biogeochemical reactions, and nitrogen-oxide dissimilation is not an exception (Liu et al., 2010, 2014; Dörsch et al., 2012; Qu et al., 2014; Brenzinger et al., 2015; Yoon et al., 2015a). pH was, in fact, suggested as an environmental parameter with significant influence on the fate of NO3–, based on the experimental results with batch cultures of S. loihica strain PV-4 (Yoon et al., 2015a). The adverse effect of acidic pH on N2O reduction by nitrous oxide reductases (NosZ) was previously observed in axenic cultures of Paracoccus denitrificans and enrichments of soils with varying pH (Bergaust et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2014). In both sets of experiments, acidic pH resulted in transient or permanent accumulations of N2O, suggesting that NosZ was less active under acidic conditions. Transcription of nosZ genes in these experiments remained intact under acidic pH, suggesting that NosZ inactivation observed at low pH is likely due to post-transcriptional regulation.

In this study, S. loihica strain PV-4 was used as a model organism to examine whether upward pH adjustment allows for simultaneous stimulation of respiratory ammonification and N2O reduction, and to investigate the relative importance of pH as an effector of nitrogen-oxide dissimilation reactions. The concentrations of the inorganic nitrogen species were monitored in anaerobic batch reactions initially amended with NO3–/NO2– and N2O at pH 6.0, 7.0, and 8.0. Transcription profiles of the functional genes encoding dissimilatory NO2– reductases (nirK and nrfA) and N2O reductase (nosZ) were analyzed with reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) technique with samples extracted from S. loihica strain PV-4 cultures at the varying pH. Limitations do exist in extrapolating experimental results from axenic culture experiments to ecological contexts; nevertheless, these experiments demonstrated that stimulation of respiratory ammonification at high pH conditions shifted the N2O-generating NO3–-reducing organism to a sink of N2O. Unlike previous observations, lowering of pH to 6.0 did not lead to inhibition of N2O reduction activity in S. loihica strain PV-4, suggesting that the cause of N2O accumulation was due to the kinetic imbalance of the nitrogen oxide reduction reactions, rather than transcriptional or post-transcriptional regulation. Our observations also suggested that the pH effects on nitrogen-oxide dissimilation reactions were not as influential as the effects of C:N or NO2–:NO3– ratios.

Materials and Methods

Media and Culture Conditions

The medium for cultivation of S. loihica strain PV-4 was prepared as described previously (Yoon et al., 2013). Medium containing 20 g NaCl, 0.233 g KH2PO4, 0.46 g K2HPO4 and 2 mL trace metal solution (Myers and Nealson, 1990) per liter was boiled with N2 flushing. pH of the medium was adjusted to 6.0, 7.0, or 8.0 with 5.0 N HCl or 5.0 N NaOH before boiling. After 100-mL aliquots of the degassed medium were distributed to N2-flushed 160 mL serum bottles, the bottles were capped with black butyl stoppers (Geo-Microbial Technologies, Inc., Ochelata OK, United States) and aluminum crimp seals and autoclaved. Wolin vitamin solution was added from a filter-sterilized 200X stock solution after autoclaving (Wolin et al., 1964). The medium was amended with sodium lactate, KNO3 (or KNO2) and NH4Cl from sterilized anoxic stock solutions to final concentrations of 560.3 mg/L (5 mM), 101.1 mg/L (1 mM), and 10.7 mg/L (0.2 mM), respectively. The inoculated serum bottles were incubated in dark at 25°C without shaking. After each experiment, final pH was measured to confirm that pH was maintained constant (within ± 0.1 of the initial value).

Analytical Procedures

Concentrations of NO3–, NO2–, NH4+ and N2O were monitored using established analytical procedures. N2O concentration was measured using HP 6890 Series gas chromatograph equipped with a HP-PLOT Q column (30 m × 0.320 mm diameter, 20 μm film thickness) and an electron capture detector (Agilent, Palo Alto, CA, United States). Headspace N2O concentration was measured by manually injecting 100 μL headspace sample into the gas chromatograph. The detection limit was approximately 2 ppmv. The total amounts of N2O in the vessels were calculated from the headspace concentrations using Equation 1.

| (1) |

where Ch is the headspace concentration in moles/L, Va and Vh are the volumes of the aqueous phase and the headspace, respectively, in liters and H is the dimensionless Henry’s constant of N2O. The dimensionless Henry’s constant at 25°C was calculated as previously described (Yoon et al., 2015b). After correcting for the effect of high salt concentration in the medium, the dimensionless Henry’s constant was calculated to be 1.82.

Aqueous NO2– and NH4+ concentrations were determined colorimetrically using HS-NO2 (N)-L and HS-NH3 (N)-L kits (Humas, Daejeon, Korea), respectively, according to the protocols provided by the manufacturer. Aqueous NO3– concentration was determined with Metrohm 863 Basic IC plus ion chromatography system (Metrohm, Riverview, FL, United States) equipped with a Metrosep A Supp 4-250/4.0 anion exchange column. In presentations of the experimental data, the quantities of the nitrogen species were expressed in μmoles/bottle for convenience in mass balance calculations.

Observation of the pH Effects on Nitrogen-Oxide Dissimilation

Precultures of S. loihica strain PV-4 cells were prepared with 5.0 mM lactate and 1.0 mM NO3– as the electron donor and the electron acceptor, respectively. These precultures were incubated until NO3– and NO2– were depleted, and 0.5 mL of the precultures were inoculated to serum bottles with fresh media adjusted to the desired pH (6.0, 7.0, or 8.0) and amended with 5.0 mM lactate and 1 mM NO3– or NO2–. Immediately after inoculation, 0.5 mL of headspace N2 was aseptically replaced with >99.999% N2O (Samoh Corporation, Daejeon, Korea). With time intervals determined from preliminary experiments, headspace and aqueous phase samples were extracted for monitoring of NO3–, NO2–, NH4+ and N2O concentrations and cell densities. For determination of N2O concentration, 100 μL of headspace gas was extracted using a 1700-series gastight syringe (Hamilton Company, Reno, NV, United States) and manually injected into the gas chromatograph. Immediately after headspace sampling, 1.5 mL of the aqueous phase was extracted using a disposable 3-mL syringe (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, United States). In order to avoid pressure loss in the vessels, 1.6 mL of N2 gas was injected before extraction of the liquid samples. After OD600 nm of the extracted cell suspension was measured using Genesys 30 visible spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, United States), the suspension was centrifuged and the concentrations of NO3–, NO2–, NH4+ and N2O in the supernatant were measured. Incubation was carried out until no further change in the concentrations of the nitrogen species was observed.

RNA Extraction and Analyses of nrfA, nirK, and nosZ Transcription

The samples for transcription analyses of the genes involved in denitrification and respiratory ammonification were extracted at multiple time points during batch cultivation of S. loihica strain PV-4 prepared and carried out identically as described above. For each batch culture amended with NO3– and N2O, N2O concentration was monitored to determine three sampling time points (Supplementary Figure S1). The pH 6.0 cultures were sampled at t = 24, 48, and 60 h, the pH 7.0 cultures were sampled at t = 11, 24, and 27 h, and pH 8.0 cultures were sampled at t = 19, 45, and 52 h. As no growth was observed at pH 6.0 when incubated with NO2– and N2O, samples were extracted only from the cultures incubated at pH 7.0 and 8.0. These cultures were sampled twice, before the onset of the exponential phase (t = 17 and t = 20, respectively, for pH 7.0 and pH 8.0 cultures) and during the mid-exponential phase (t = 49 h and t = 45 h, respectively, for pH 7.0 and pH 8.0 cultures). One-half milliliter samples were collected from three biological replicates upon each sampling event. One milliliter of RNA Protect Bacteria Reagent (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) was immediately added to each of the aliquots and the mixture was immediately centrifuged for 10 min at 5,000 × g. The cell pellets were stored at -80°C until further processing.

An established protocol was used for extraction and purification of total RNA with a few modifications (Park et al., 2017). The cell pellets were thawed in ice and were subjected to disruption with Omni Bead Ruptor 12 Homogenizer (Omni International, Kennesaw, GA, United States) after addition of 350 μL buffer RLT solution and 30 mg of 0.1 mm glass beads (Omni International). Total RNA was extracted using RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) according to the protocol provided by the manufacturer and resulting RNA was eluted with 60 μL RNase-free water. Remaining DNA in the eluent was digested using RNase-free DNase Set Kit (Qiagen) as previously described (Park et al., 2017) and the reaction mix was purified using RNase-free DNase Kit (Qiagen). Reverse transcription was performed with 11 μL of 20 μL eluent using SuperscriptTM III Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, United States). The remaining eluent was used later in a quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) to confirm the absence of contaminating DNA. After reverse transcription, each sample was treated with RNase H (Invitrogen) to remove traces of RNA. The cDNA solution was diluted five-fold with nuclease-free water and stored at -20°C until analyzed using qPCR.

The quantities of nirK, nrfA, nosZ, and recA genes in the cDNA solutions were determined using the qPCR technique. nirK and nosZ genes were present in single copies in S. loihica strain PV-4 genome and only nrfA0844 of the two nrfA-like genes was targeted, as the expression of nrfA0505 did not correlate with respiratory ammonification activity (Yoon et al., 2015a). The primers used in this study are listed in Table 1. The primers specifically targeting nrfA, nirK, and recA genes of S. loihica strain PV-4 were designed de novo using Primer 3 software (Rozen and Skaletsky, 2000) and a previously designed primer was used for amplification of nosZ (Yoon et al., 2015a). The target specificities of the primer sets were tested with ordinary PCR and the PCR products were used to construct calibration curves for absolute quantification of target genes. The PCR products were inserted into PCR2.1 vectors and the resulting plasmids were extracted using QIAprep Spin Miniprep Kit (Qiagen). The copy numbers of the extracted plasmids were calculated from the nucleic acid concentration measured with Nanodrop 2000 UV-Vis spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and the expected molecular weights of the plasmids. Dilution series of the plasmids ranging from 1 to 108 copies/μL were prepared and used for calibration curve construction. qPCR was performed with QuantStudioTM 3 Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using SYBR Green detection chemistry. 2X Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix Solution (Applied Biosystems) was used to prepare the reaction mix and a two temperature-cycle procedure was used for qPCR, with 95°C denaturation step (15 s) followed by 60°C elongation step (60 s) in each of 40 cycles. The amplification efficiencies ranged between 94.0 and 99.8% and the R2 values of the calibration curves were no less than 0.998 (Table 1). No amplification was observed in the negative controls without target DNA or cDNA. The qPCR assays for all four target genes were reliable down to 101 copies/μL, and the preparations with 1 copy/μL did not yield consistent results. Consistent melting curves confirmed the specificity of the qPCR reactions.

Table 1.

Primers used for the RT-qPCR assays.

| Primer | Sequence (5′→3′) | Target gene | Amplicon length (bp) | Slope | y-intercept | Amplification efficiency | R2 | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SlonirK755f | TGAGTGAGGTGCTTGAGGTG | nirK | 237 | –3.474 | 35.552 | 94.0 | 0.998 | This study |

| SlonirK991r | TCCAGGTTTCCAGATTGGTC | |||||||

| SlonrfA724f | CGTCATCCTGAGTTTGAGCA | nrfA | 227 | –3.477 | 36.396 | 99.8 | 0.998 | Yoon et al., 2013 |

| SlonrfA950r | TTCTCGGCTATCTGCGACTT | |||||||

| SlorecA656f | ACGCTTCTGTTCGTCTGGAT | recA | 245 | –3.366 | 35.931 | 98.2 | 0.999 | This study |

| SlorecA900r | GCCAATCTTGTCACCCTT | |||||||

| SlonosZ599f | ATGGTAAGGAGACGCTGGAA | nosZ | 160 | –3.386 | 34.713 | 97.4 | 0.999 | This study |

| SlonosZ758r | TTGTAGCAGGTAGAGGCGAAG |

The copy numbers of nirK, nrfA, and nosZ in each cDNA sample were normalized with the copy number of recA, the housekeeping gene that encodes DNA recombination/repair protein RecA. Transcription levels of recA genes were previously observed to be relatively stable under different growth conditions and growth stages in diverse groups of bacteria including Streptococcous agalactiae and Lactobacillus plantarum (Marco and Kleerebezem, 2008; Florindo et al., 2012). Thus, recA was selected as the most suitable target gene for normalization of the RT-qPCR data to account for the differences in cell densities and overall metabolic activities, as well as mRNA loss during extraction, purification, and reverse transcription procedures. The copy numbers of the nirK, nrfA, and nosZ genes in the cDNA samples were divided by the copy number of the recA gene and the nirK/recA, nrfA/recA, and nosZ/recA values were compared across the samples collected from different incubation conditions.

Statistical analyses for the RT-qPCR results were performed using SPSS Statistics 24 software (IBM Corp. Armonk, NY, United States). The RT-qPCR reactions were performed with the samples collected from triplicate reaction vessels and independently processed through extraction, purification and reverse transcription procedures. Statistical analyses were performed with the data transformed to a logarithmic scale.

Results

Effects of pH on the NO3– Reduction Pathways and N2O Fate during NO3– Reduction

pH conditions determined whether S. loihica strain PV-4 reduced NO3– to NH4+ (respiratory ammonification) or to N2 via N2O (through denitrification) and also, whether the batch system functioned as a sink or a source of N2O during NO3– reduction (Figure 1). At all three pH conditions tested, all of NO3– added to a nominal concentration of 1.0 mM was consumed after 28 – 72 h after inoculation. The strain PV-4 culture incubated at pH 7.0 had the shortest lag period (∼8 h), while pH 6 and pH 8 cultures both had longer lag phases, as significant decreases in NO3– concentrations and increases in the cell densities were observed 35 and 22 h after inoculation, respectively. The maximum observed rates of NO3– reduction (pH 6.0: 14.1 μmoles h-1 mL-1 OD600 nm-1 at t = 54.5 h; pH 7.0: 19.1 μmoles h-1mL-1 OD600 nm-1 at t = 13.5 h; pH 8.0: 6.4 μmoles h-1 mL-1 OD600 nm-1 at t = 36 h) and exponential growth rates (0.18, 0.33, and 0.15 h-1 at pH 6, 7, and 8, respectively) indicated that neutral pH was optimal for S. loihica strain PV-4, but also that overall cellular function of S. loihica strain PV-4 was not substantially compromised by the shift of pH within the examined range.

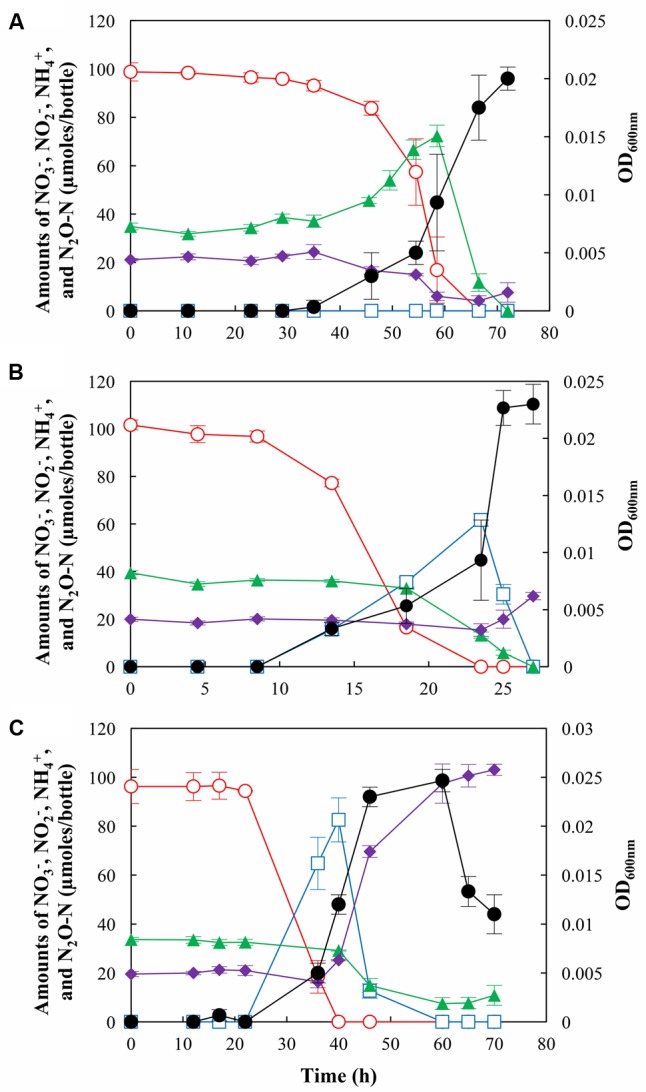

FIGURE 1.

N2O production and/or consumption by Shewanella loihica strain PV-4 during reduction of NO3– at (A) pH 6.0, (B) pH 7.0, and (C) pH 8.0. The amounts of NO3– ( ), NO2– (

), NO2– ( ), NH4+ (

), NH4+ ( ), and N2O-N (

), and N2O-N ( ) in the culture bottles were monitored until no more change was observed. The OD600

nm values (●) were measured to monitor the cell growth. The data points represent the averages of triplicate cultures and the error bars represent their standard deviations.

) in the culture bottles were monitored until no more change was observed. The OD600

nm values (●) were measured to monitor the cell growth. The data points represent the averages of triplicate cultures and the error bars represent their standard deviations.

The strain PV-4 cultures incubated at different pH conditions were distinguished by the magnitudes of transient NO2–accumulation. Accumulation of NO2– was not observed in the culture incubated at pH 6.0 and the concentration of NO2– remained below the detection limit throughout the experiment, indicating that potential NO2– reduction rate was at least as high as the rate of NO3– reduction. Contrastingly, at pH 7.0 and 8.0, NO2– accumulations up to 61.7 ± 2.6 μmoles/bottle and 82.6 ± 9.0 μmoles/bottle were observed, respectively, indicating that the rates of NO2– reduction were slower than the rates of NO3– reduction.

At pH 7.0 and 8.0, S. loihica strain PV-4 functioned as a net sink of N2O, as N2O concentrations decreased consistently throughout incubation periods (Figure 1). No transient N2O accumulation was observed in the cultures incubated at pH 7.0 and 8.0. A clearly distinct trend was observed in the strain PV-4 culture incubated at pH 6.0, as a transient accumulation of N2O up to 72.3 ± 4.5 μmoles N2O-N/bottle (37.4 μmoles N2O-N/bottle higher than initially added N2O-N) occurred before NO3– depletion. Although N2O accumulation was observed, N2O reduction was active throughout the experiment. The maximum N2O reduction rate of 12.2 μmoles N2O-N h-1 mL-1 OD600 nm-1 was calculated at t = 54.5 h. This rate was comparable to the calculated maximum N2O reduction rate of 14.2 μmoles N2O-N h-1 mL-1 OD600 nm-1 at pH 7.0 at t = 23.5 h. At pH 8.0, the maximum observed N2O reduction rate (279 nmoles N2O-N h-1mL-1 OD600 nm-1 at t = 40 h) was substantially lower than those observed at pH 6.0 and 7.0. N2O reduction stopped after 60 h, when the dissolved N2O concentration was lowered to 0.75 μM and no other electron acceptor was available in the medium. Energy gained from N2O reduction may not be sufficient per se to support growth at the alkaline pH. In fact, no significant growth or N2O consumption was observed for 200 h when strain PV-4 was incubated with N2O as the sole electron acceptor at pH 8.0 (data not shown).

pH was also a determinant of NO3– fate in the strain PV-4 cultures. Nitrogen mass balance was used to estimate the magnitude of denitrification activity, assuming that >90% of NO3–/NO2– was dissimilated to either NH4+ or denitrification products (Yoon et al., 2015a). At pH 6.0, consumption but not production of NH4+ was observed, as the amount of NH4+ decreased from 21.1 ± 0.5 μmoles/bottle to 4.2 ± 2.1 μmoles/bottle after cultivation, indicating that denitrification was the dominant NO3– reduction pathway. The respiratory ammonification pathway was mostly switched off, although a statistically insignificant increase (3.4 ± 1.9 μmoles/bottle) in the amount of NH4+ was observed after t = 66.5 h. At pH 7.0, an increase in the NH4+ concentration was observed between t = 25 h and t = 27 h and ∼9.6% (9.7 ± 2.3 μmoles) of initially added 101.6 ± 2.1 μmoles NO3– was reduced to NH4+; however, NH4+ was still a minor product. The distribution of products from NO3– reduction at pH 8.0 was distinctively different from the results observed at pH 6.0 and 7.0. NH4+ was the major product of NO3– reduction, as 83.5 ± 1.2 μmoles of NO3– was reduced to NH4+. Respiratory ammonification dominated NO3– reduction at the alkaline pH and shutdown of the NirK-mediated NO2– reduction activity could be inferred from the mass balance. With diminished denitrification activity, S. loihica strain PV-4 cultures functioned as an N2O sink at pH 8.0 despite of reduced N2O reduction activity.

Effects of pH on NO2– Reduction Pathways and N2O Fate during NO2– Reduction

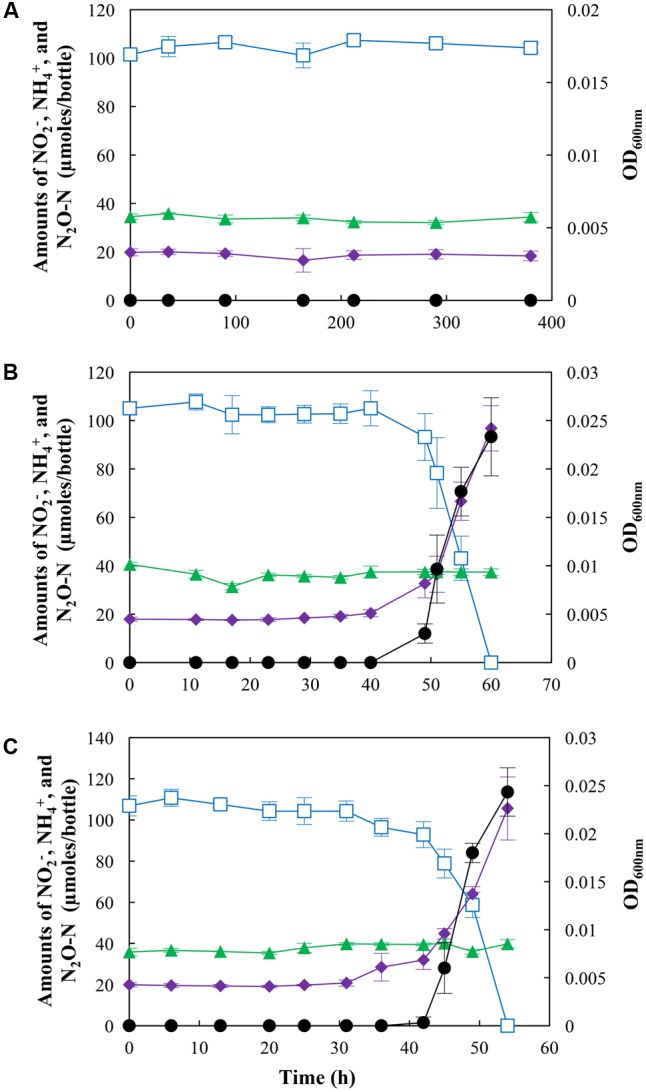

When S. loihica strain PV-4 cultures were amended with NO2– instead of NO3–, the effects of pH on NO2– reduction pathways were obscured by the effect of NO2– (Figure 2). At pH 6.0, neither cell growth or significant change in concentrations of NO2–, NH4+, or N2O was observed for >300 h. Lowering of the initial NO2– concentration to 0.1 mM did not result in cell growth or metabolic activity (data not shown), precluding the possibility that the toxicity of HNO2 at the acidic pH was the cause of growth inhibition. The experiments at pH 7.0 and pH 8.0 yielded statistically indistinguishable results (p > 0.05), as NH4+ was the predominant product (78.9 ± 8.5 μmoles and 85.7 ± 5.5 μmoles recovered as NH4+ at pH 7.0 and 8.0, respectively) regardless of pH. No significant change in the concentration of N2O was observed at either pH, indicating that the pathways leading to the production and consumption of N2O were inactive when S. loihica strain PV-4 was incubated with NO2–. These results suggested that the pH effect on nitrogen-oxide dissimilation was eclipsed by the NO2– effect.

FIGURE 2.

N2O production and/or consumption by Shewanella loihica strain PV-4 during reduction of NO2– at (A) pH 6.0, (B) pH 7.0, and (C) pH 8.0. The amounts of NO2– ( ), NH4+ (

), NH4+ ( ), and N2O-N (

), and N2O-N ( ) in the culture bottles were monitored until no more change was observed. The OD600nm values (●) were measured to monitor the cell growth. The data points represent the averages of triplicate cultures and the error bars represent their standard deviations.

) in the culture bottles were monitored until no more change was observed. The OD600nm values (●) were measured to monitor the cell growth. The data points represent the averages of triplicate cultures and the error bars represent their standard deviations.

Effect of pH on Transcription of nirK, nrfA, and nosZ Genes

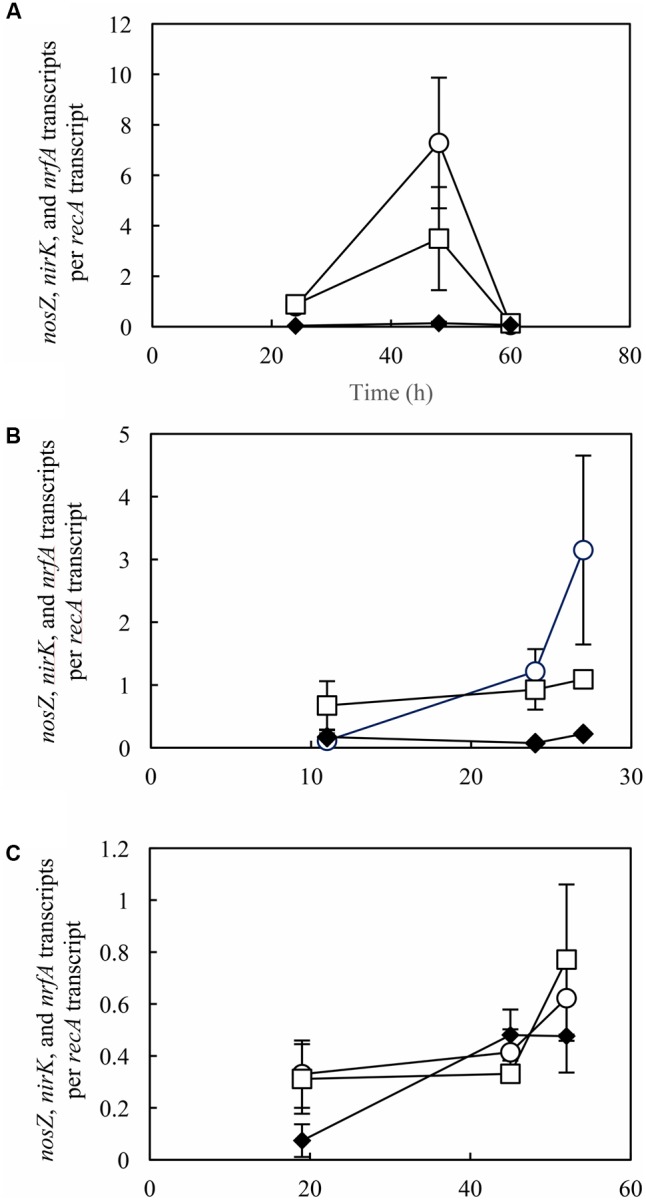

Transcription analyses were performed using RT-qPCR technique with samples extracted at different time points during incubation of S. loihica strain PV-4 (Figures 3, 4). To account for the differences in the cell densities and overall metabolic activities at different culturing conditions and growth stages, the nosZ transcription data were normalized with the recA transcription data. At pH 6.0 and pH 7.0, nirK transcription levels were at least five-fold higher than those of nrfA throughout the incubation periods except at t = 60 h at pH 6.0. The reduced transcription of nirK at this time point may be due to the depletion of NO3–. At pH 8.0, the differences in transcription of nrfA and nirK were insignificant (p > 0.05) throughout incubation (Figure 3). These transcription profiles explained the dominance of denitrification activity at pH 6.0 and 7.0 and the predominance of respiratory ammonification activity at pH 8.0. As expected from the sustained N2O reduction activity at pH 6.0, nosZ transcription was not adversely affected by the acidic pH (Figure 3). Transcription of nosZ was significantly more active at pH 6.0 and 7.0 than at pH 8.0, as the maximum nosZ transcripts / recA transcript values of 7.28 ± 2.59, 3.15 ± 1.50, and 0.62 ± 0.16 were recovered from samples extracted from the mid-exponential-phase cultures incubated at pH 6.0 (at t = 48 h), 7.0 (at t = 27 h), and 8.0 (at t = 52 h), respectively.

FIGURE 3.

Transcription analyses of nosZ (○), nirK (□), and nrfA (♦) in Shewanella loihica strain PV-4 cells grown with NO3– and N2O at pH (A) 6.0, (B) 7.0, and (C) 8.0. RT-qPCR was performed with samples extracted from batch cultures at the exponential phase. The error bars represent the standard deviations of three biological replicates processed independently through RNA extraction, purification, and reverse transcription procedures.

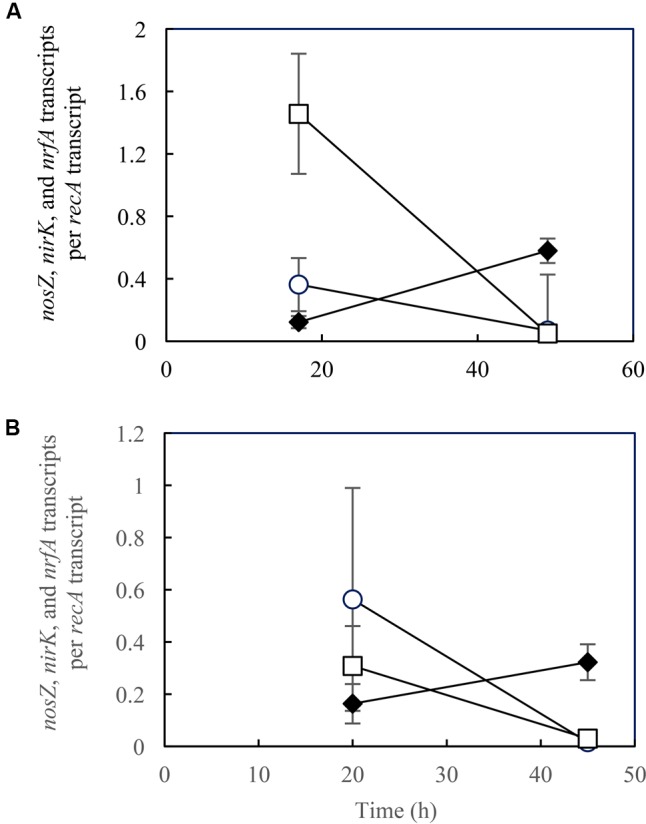

FIGURE 4.

Transcription analyses of nosZ (○), nirK (□), and nrfA (♦) in Shewanella loihica strain PV-4 cells grown with NO2– and N2O at pH (A) 7.0, and (B) 8.0. RT-qPCR was performed with samples extracted from batch cultures at the exponential phase. The error bars represent the standard deviations of three biological replicates processed independently through RNA extraction, purification, and reverse transcription procedures.

In the samples extracted from S. loihica strain PV-4 cultures grown with NO2– and N2O as the electron acceptors, distinguishable shifts in nirK, nrfA, and nosZ transcription levels from the lag phase (t = 17 h for pH 7.0 and t = 20 h for pH 8.0) to the mid-exponential phase (i.e., at t = 49 h for pH 7.0 and t = 45 h for pH 8.0) were observed (Figure 4). At the mid-exponential phase when active NO3–/NO2– reduction occurred, nrfA transcription levels were an order of magnitude higher than nirK transcription levels. The nirK transcription-to-nrfA transcription ratios were statistically indistinguishable between pH 7.0 and pH 8.0 (p > 0.05). These observations were in agreement with the predominance of respiratory ammonification. The diminished transcription of the genes responsible for N2O-producing reactions (nirK) and N2O-consuming reaction (nosZ) explained the absence of N2O production or consumption in the cultures amended with NO2– and N2O.

Discussion

The experiments performed with S. loihica strain PV-4 with NO3– and N2O as electron acceptors confirmed the previous finding that pH is a significant environmental parameter that regulate nitrogen-oxide dissimilation reactions. pH was previously suggested as one of the environmental parameters that determine the fate of NO3– in axenic cultures of S. loihica strain PV-4 and also, in complex mixed cultures (Stevens et al., 1998; Yoon et al., 2015a). The endpoint measurements of nitrogen species suggested enhancements of respiratory ammonification activity (or DNRA in ecological context) under alkaline conditions; however, no experiment has been performed to monitor the time-dependent progression of the reactions nor to investigate the molecular basis of this regulation. The findings from the RT-qPCR assays in this study confirmed that the transcription regulation of nirK and nrfA was the cause of bifurcation of NO3– fate at different pH. This finding was consistent with the previous observations that the response of S. loihica strain PV-4 to shifting C:N ratio and NO2–:NO3– ratio occurred at the transcription level (Yoon et al., 2015a,b), suggesting that the organism actively selects for the NO3–/NO2– reduction pathway that ensures the most efficient use of the electron acceptors in response to the shifting growth conditions. In the cases of C:N ratio and NO2–:NO3– ratio, the rationale for such pathway selection was explained as the selection for more favorable energetics and higher electron transfer efficiency (Yoon et al., 2015a,b). The rationale for pathway selection upon pH shift may be found from the activities of the nitrite reductases at different pH. The optimal activities of isolated CuNIR were observed at pH < 7.0 (Abraham et al., 1997; Jacobson et al., 2007), while isolated NrfA proteins had pH optima at pH > 7.5 without exception (Liu and Peck, 1981; Kajie and Anraku, 1986). S. loihica strain PV-4 may have evolved to increase the expression of the nitrite reductase that has higher activity at the pH of its environ.

The absence of growth with NO2– and N2O as the electron acceptors at pH 6.0 was an unanticipated result. NO2– and its protonated form HNO2 are widely known to be toxic to microorganisms. Shewanella loihica strain PV-4 was previously found to be vulnerable to the elevated NO2– concentrations (>2.0 mM NO2–); however, toxicity of NO2– at 1.0 mM concentration was not sufficient to have an adverse impact on cell growth (Yoon et al., 2015b). Nitrous acid (HNO2) is known to be more toxic than NO2– (Jiang et al., 2011). As HNO2/NO2– couple has a pKa value of 3.15, the concentration of HNO2 would be ∼10-fold higher at pH 6.0 than at pH 7.0, provided that the total HNO2/NO2– concentration remains unchanged. If increased HNO2 toxicity was the reason for the lack of growth, strain PV-4 would have grown with lowered NO2– concentration (0.1 mM). Thus, the absence of growth with 0.1 mM NO2– suggested that the HNO2 toxicity was not the cause for the growth inhibition at pH 6.0. Although largely speculative, the absence of growth may be explained with the differential transcription levels and activities of the enzymes involved with nitrogen-oxide dissimilation at the varying pH conditions. The elevated NO2–:NO3– ratio could have resulted in down-regulation of nirK and nosZ transcription and up-regulation of nrfA transcription. As NrfA has diminished activity at low pH, S. loihica strain PV-4 may lack active NO2–-reducing enzymes and thus, may not be able to generate sufficient energy for growth.

The transient N2O accumulation observed during NO3– reduction by S. loihica strain PV-4 was consistent with the observations made previously with P. denitrificans and soil microbial consortia (Liu et al., 2010, 2014; Bergaust et al., 2012; Brenzinger et al., 2015). N2O peak was observed only at the lowest pH tested, pH 6.0, while N2O was steadily reduced at higher pH. The accumulation of N2O in the S. loihica strain PV-4 cultures at pH 6.0 was not accompanied with the decrease in transcription of nosZ or diminished N2O reduction activity, precluding transcriptional or post-transcriptional regulation of NosZ as the cause of N2O accumulation (Liu et al., 2014). Instead, the findings in this study suggest another mechanism that may contribute to accumulation of N2O in acidic environments. The transcription of nirK, the gene that encodes for the copper-dependent nitrite reductase, was significantly up-regulated at pH 6.0 as compared to the other pH conditions. Rapid NO2– reduction accompanied the enhanced nirK transcription. The N2O reduction rates were, in fact, higher at pH 6.0 than at pH 8.0; however, the rate of N2O production from NO2– was higher than the N2O consumption rate at the acidic pH. Such kinetic imbalance in the chain of reactions constituting the denitrification pathway in strain PV-4 may be the major cause of N2O accumulation at pH 6.0. Upregulation of transcription of NO-forming nitrite reductase genes (i.e., nirK or nirS) under acidic pH was previously observed upon incubation of soil inoculum (Liu et al., 2014). Our observations suggest that the kinetic imbalance caused by enhancement of N2O-producing reaction (i.e., NO2– reduction) as relative to N2O-removal reaction (i.e., N2O reduction) may be one of the major cause of enhanced N2O emissions from moderately acidic environments.

The positive correlation of DNRA activity with pH has been observed in experiments with soils and sediments (Stevens et al., 1998; Zhang et al., 2015), although other experimental results showed dominance of denitrification as the NO3–/NO2– reduction pathway even under alkaline conditions (Liu et al., 2010, 2014). Regulation of denitrification and DNRA activity in S. loihica strain PV-4 was previously observed to be hierarchical, as the effect of C:N ratio overshadowed the effect of NO2–:NO3– ratio when either lactate or NO3– was limiting (Yoon et al., 2015b). Likewise, the effect of pH was eclipsed by the NO2–:NO3– effect in this study, as NO2– was reduced exclusively via respiratory ammonification pathway regardless of pH. This hierarchical regulation may be applicable to soils and sediments and pH may be a determinant of the fate of NO3– and NO2– only when their reduction pathway is not predetermined by overarching environmental factors. Agricultural soils simultaneously exhibiting both denitrification and DNRA activities are not rare (Burgin and Hamilton, 2007). pH control may be essential in management of these ‘ambivalent’ agricultural soils, as maintenance of alkaline conditions would reduce nitrogen loss while shifting the soils toward sink of N2O. Pure culture experiments may not be sufficient to portray the complex nature of environmental systems; however, the observations with S. loihica strain PV-4 certainly demonstrate the feasibility of manipulation of soil nitrogen cycling to simultaneously reduce N2O emission and promote N retention via pH control.

Author Contributions

HK performed the experiments and analyzed data. HK and DP developed the experimental methodology for RT-qPCR assays. SY planned the research and designed the experiments. HK and SY wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed results and commented on the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. This research was financially supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (Award 2015M3D3A1A01064881) and Korea Institute of Planning and Evaluation for Technology in Food, Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (Award 916007-02-1-HD030).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fmicb.2017.01820/full#supplementary-material

References

- Abraham Z. H., Smith B. E., Howes B. D., Lowe D. J., Eady R. R. (1997). pH-dependence for binding a single nitrite ion to each type-2 copper centre in the copper-containing nitrite reductase of Alcaligenes xylosoxidans. Biochem. J. 324 511–516. 10.1042/bj3240511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergaust L., Mao Y., Bakken L., Frostegård Å. (2010). Denitrification response patterns during the transition to anoxic respiration and posttranscriptional effects of suboptimal pH on nitrous oxide reductase in Paracoccus denitrificans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76 6387–6396. 10.1128/AEM.00608-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergaust L., van Spanning R. J. M., Frostegård Å., Bakken L. R. (2012). Expression of nitrous oxide reductase in Paracoccus denitrificans is regulated by oxygen and nitric oxide through FnrP and NNR. Microbiology 158 826–834. 10.1099/mic.0.054148-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenzinger K., Dörsch P., Braker G. (2015). pH-driven shifts in overall and transcriptionally active denitrifiers control gaseous product stoichiometry in growth experiments with extracted bacteria from soil. Front. Microbiol. 6:961 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgin A. J., Hamilton S. K. (2007). Have we overemphasized the role of denitrification in aquatic ecosystems? A review of nitrate removal pathways. Front. Ecol. Environ. 5 89–96. 10.1890/1540-9295(2007)5[89:HWOTRO]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson E. A. (2009). The contribution of manure and fertilizer nitrogen to atmospheric nitrous oxide since 1860. Nat. Geosci. 2 659–662. 10.1038/ngeo608 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dörsch P., Braker G., Bakken L. R. (2012). Community-specific pH response of denitrification: experiments with cells extracted from organic soils. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 79 530–541. 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2011.01233.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzhugh R. D., Lovett G. M., Venterea R. T. (2003). Biotic and abiotic immobilization of ammonium, nitrite, and nitrate in soils developed under different tree species in the Catskill Mountains, New York, United States. Glob. Change Biol. 9 1591–1601. 10.1046/j.1365-2486.2003.00694.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Florindo C., Ferreira R., Borges V., Spellerberg B., Gomes J. P., Borrego M. J. (2012). Selection of reference genes for real-time expression studies in Streptococcus agalactiae. J. Microbiol. Methods 90 220–227. 10.1016/j.mimet.2012.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson F., Pistorius A., Farkas D., De Grip W., Hansson Ö., Sjölin L., et al. (2007). pH dependence of copper geometry, reduction potential, and nitrite affinity in nitrite reductase. J. Biol. Chem. 282 6347–6355. 10.1074/jbc.M605746200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang G., Gutierrez O., Yuan Z. (2011). The strong biocidal effect of free nitrous acid on anaerobic sewer biofilms. Water Res. 45 3735–3743. 10.1016/j.watres.2011.04.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajie S., Anraku Y. (1986). Purification of a hexaheme cytochrome C552 from Escherichia coli K12 and its properties as a nitrite reductase. Eur. J. Biochem. 154 457–463. 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1986.tb09419.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraft B., Tegetmeyer H. E., Sharma R., Klotz M. G., Ferdelman T. G., Hettich R. L., et al. (2014). The environmental controls that govern the end product of bacterial nitrate respiration. Science 345 676–679. 10.1126/science.1254070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroeze C., Mosier A., Bouwman L. (1999). Closing the global N2O budget: a retrospective analysis 1500–1994. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 13 1–8. 10.1029/1998GB900020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Laima M. J. C., Girard M. F., Vouve F., Blanchard G. F., Gouleau D., Galois R., et al. (1999). Distribution of adsorbed ammonium pools in two intertidal sedimentary structures, Marennes-Oleron Bay, France. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 182 29–35. 10.3354/meps182029 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lashof D. A., Ahuja D. R. (1990). Relative contributions of greenhouse gas emissions to global warming. Nature 344 529–531. 10.1038/344529a0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B., Frostegård Å., Bakken L. R. (2014). Impaired reduction of N2O to N2 in acid soils is due to a posttranscriptional interference with the expression of nosZ. mBio 5:e01383-14 10.1128/mbio.01383-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B., Mørkved P. T., Frostegård Å., Bakken L. R. (2010). Denitrification gene pools, transcription and kinetics of NO, N2O and N2 production as affected by soil pH. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 72 407–417. 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2010.00856.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M. C., Peck H. D. (1981). The isolation of a hexaheme cytochrome from Desulfovibrio desulfuricans and its identification as a new type of nitrite reductase. J. Biol. Chem. 256 13159–13164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marco M. L., Kleerebezem M. (2008). Assessment of real-time RT-PCR for quantification of Lactobacillus plantarum gene expression during stationary phase and nutrient starvation. J. Appl. Microbiol. 104 587–594. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2007.03578.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers C. R., Nealson K. H. (1990). Respiration-linked proton translocation coupled to anaerobic reduction of manganese (IV) and iron (III) in Shewanella putrefaciens MR-1. J. Bacteriol. 172 6232–6238. 10.1128/jb.172.11.6232-6238.1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park D., Kim H., Yoon S. (2017). Nitrous oxide reduction by an obligate aerobic bacterium, Gemmatimonas aurantiaca strain T-27. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 83 e502–e517. 10.1128/aem.00502-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portmann R. W., Daniel J. S., Ravishankara A. R. (2012). Stratospheric ozone depletion due to nitrous oxide: influences of other gases. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 367 1256–1264. 10.1098/rstb.2011.0377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu Z., Wang J., Almøy T., Bakken L. R. (2014). Excessive use of nitrogen in Chinese agriculture results in high N2O/(N2O+N2) product ratio of denitrification, primarily due to acidification of the soils. Glob. Change Biol. 20 1685–1698. 10.1111/gcb.12461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravishankara A. R., Daniel J. S., Portmann R. W. (2009). Nitrous oxide (N2O): the dominant ozone-depleting substance emitted in the 21st century. Science 326 123–125. 10.1126/science.1176985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reay D. S., Davidson E. A., Smith K. A., Smith P., Melillo J. M., Dentener F., et al. (2012). Global agriculture and nitrous oxide emissions. Nat. Clim. Change 2 410–416. 10.1038/nclimate1458 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rozen S., Skaletsky H. (2000). Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers. Methods Mol. Biol. 132 365–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver W. L., Herman D. J., Firestone M. K. (2001). Dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium in upland tropical forest soils. Ecology 82 2410–2416. 10.1890/0012-9658(2001)082[2410:DNRTAI]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens R. J., Laughlin R. J., Malone J. P. (1998). Soil pH affects the processes reducing nitrate to nitrous oxide and di-nitrogen. Soil Biol. Biochem. 30 1119–1126. 10.1016/S0038-0717(97)00227-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tiedje J. M., Sexstone A. J., Myrold D. D., Robinson J. A. (1983). Denitrification: ecological niches, competition and survival. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 48 569–583. 10.1007/BF00399542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg E. M., Boleij M., Kuenen J. G., Kleerebezem R., van Loosdrecht M. C. M. (2016). DNRA and denitrification coexist over a broad range of acetate/N-NO3- ratios, in a chemostat enrichment culture. Front. Microbiol. 7:1842 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van den Berg E. M., van Dongen U., Abbas B., van Loosdrecht M. C. M. (2015). Enrichment of DNRA bacteria in a continuous culture. ISME J. 9 2153–2161. 10.1038/ismej.2015.26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolin E. A., Wolfe R. S., Wolin M. J. (1964). Viologen dye inhibition of methane formation by Methanobacillus omelianskii. J. Bacteriol. 87 993–998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon S., Cruz-Garcia C., Sanford R., Ritalahti K. M., Löffler F. E. (2015a). Denitrification versus respiratory ammonification: environmental controls of two competing dissimilatory NO3–/NO2– reduction pathways in Shewanella loihica strain PV-4. ISME J. 9 1093–1104. 10.1038/ismej.2014.201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon S., Sanford R. A., Löffler F. E. (2013). Shewanella spp. use acetate as an electron donor for denitrification but not ferric iron or fumarate reduction. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79 2818–2822. 10.1128/AEM.03872-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon S., Sanford R. A., Löffler F. E. (2015b). Nitrite control over dissimilatory nitrate/nitrite reduction pathways in Shewanella loihica strain PV-4. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 81 3510–3517. 10.1128/AEM.00688-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Lan T., Müller C., Cai Z. (2015). Dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium (DNRA) plays an important role in soil nitrogen conservation in neutral and alkaline but not acidic rice soil. J. Soils Sediments 15 523–531. 10.1007/s11368-014-1037-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.