Summary

Haematology and blood transfusion, as a clinical and laboratory discipline, has a far-reaching impact on healthcare both through direct patient care as well as provision of laboratory and transfusion services. Improvement of haematology and blood transfusion may therefore be significant in achieving advances in health in Africa. In 2005, Tanzania had one of the lowest distributions of doctors in the world, estimated at 2·3 doctors per 100 000 of population, with only one haematologist, a medical doctor with postgraduate medical education in haematology and blood transfusion. Here, we describe the establishment and impact of a postgraduate programme centred on Master of Medicine and Master of Science programmes to build the capacity of postgraduate training in haematology and blood transfusion. The programme was delivered through Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences (MUHAS) with partnership from visiting medical and laboratory staff from the UK and complemented by short-term visits of trainees from Tanzania to Haematology Departments in the UK. The programme had a significant impact on the development of human resources in haematology and blood transfusion, successfully training 17 specialists with a significant influence on delivery of health services and research. This experience shows how a self-sustaining, specialist medical education programme can be developed at low cost within Lower and Middle Income Countries (LMICs) to rapidly enhance delivery of capacity to provide specialist services.

Keywords: blood transfusion, haematology, Tanzania, medical education

Healthcare in East Africa, as elsewhere, has been transformed over the last decades by economic growth, widespread public health interventions and the development of health services. These developments have yielded dramatic reductions in neonatal and childhood mortality and the prevalence of many communicable diseases (Global Burden of Disease [GBD] 2015 Child Mortality Collaborators, 2016). With these changes, the role of non-communicable disease and the delivery of healthcare at secondary and tertiary level health facilities assume greater importance, not only for individual patient care, but also to develop and implement services and polices that reach wider populations locally, regionally and nationally (Wang et al, 2014; GBD 2015 Maternal Mortality Collaborators, 2016).

Haematology and blood transfusion, as a clinical and laboratory discipline, has a far-reaching impact on healthcare, both through direct patient care and provision of laboratory and transfusion services. For example, the determination of haemoglobin is the most commonly requested laboratory test in sub-Saharan Africa (Njelesani et al, 2014). More widely, there is a need for specialist services in haematology to improve maternal and child mortality, and the causes of illness and death due to infectious diseases, such as malaria, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and tuberculosis, can be directly linked to shortfalls in haematology and blood transfusion knowledge and services, for example, by failure to provide a timely and/or safe supply of blood [for review see (Roberts et al, 2016)]. Indeed, it is broadly recognised that human resources for health is a key component to improving healthcare. Improvement of haematology and blood transfusion may therefore be significant in achieving advances in heath in Africa.

We found that there was a significant limitation in haematology expertise and training in Tanzania that was hindering the development of haematology services, including sickle cell disease (SCD), haematological oncology and blood transfusion. We describe how, over a decade, we developed training programmes in Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences (MUHAS) in Dar-es-Salaam, Tanzania (http://www.muhas.ac.tz/, last accessed 10 February 2017). This has had a significant impact on the Department of Haematology and Blood Transfusion at Muhimbili National Hospital (MNH) as well as other health facilities in Tanzania. This experience shows how a short- and long-term strategy for building the capacity of haematology and blood transfusion services can be achieved and could be replicated in other locations and specialties.

Development of doctors and medical training in East Africa

Health services in a tertiary hospital in Dar-es-Salaam, Tanzania

The early medical services in what is now Tanzania were provided by the German Government and include the seminal research work of Professor Robert Koch on plague, malaria and sleeping sickness. The Government Chemist, Gustav Giemsa, developed the eponymous stain for malaria parasites in blood films which is still in daily use in laboratories around the world (Clyde, 1962). Healthcare in Tanzania later developed from a network of mission and government hospitals in the last half of the 20th century (Clyde, 1962).

Over time, healthcare in public hospitals was divided into primary, secondary and tertiary level care. Muhimbili National Hospital (MNH) is a tertiary level health facility that is the National Referral Hospital in Tanzania. The origins of MNH can be traced back to 1910–1920, when it was known as Sewa Haji Hospital. In 1956, the name changed to Princess Margaret Hospital. Soon after independence in 1961, it was named Muhimbili Hospital until 1976 when it was incorporated into the Muhimbili Medical Centre (MMC; Clyde, 1962; http://www.muhas.ac.tz/, last accessed 10 February 2017).

In 2000, MMC was separated into Muhimbili National Hospital and the Muhimbili University College of Health Sciences (MUCHS). The essence of separating MMC and MUCHS was to make MNH more efficient and for MNH and MUHAS to become accredited centres of excellence for hospital care in Africa as well as a centre for clinical training of medical and allied health personnel, and an acknowledged centre of medical research in Africa. MNH is the National Referral Hospital and affiliated MUHAS Teaching Hospital, which has 1500 beds, admitting 1000 to 1200 in-patients per day, and a weekly outpatient attendance of 1000 to 1200 (http://www.muhas.ac.tz).

Medical School

The first medical school in East Africa was Makerere University Medical School in 1924, which was based within the Mulago National Referral and Teaching Hospital complex, Kampala, Uganda. In 2007 it became the Makerere University College of Health Sciences. Several doctors from Tanzania were trained in Uganda, but local expertise began to be developed at Dar es Salaam School of Medicine, which was established in 1963 by the Ministry of Health with the primary aim of training clinical health staff. In 1968, the Dar es Salaam School of Medicine was upgraded to a Faculty of Medicine of the Dar es Salaam University College of the University of East Africa. In 1976, the Faculty of Medicine was incorporated into Muhimbili Hospital to form the MMC (http://www.muhas.ac.tz).

In 1991, the Faculty of Medicine was upgraded to a constituent College of the University of Dar es Salaam, with the aim of nurturing it to a fully-fledged university. In 2000, the Government disestablished MMC and, as described above, created two closely-linked, but autonomous public institutions; namely Muhimbili University College of Health Sciences (MUCHS) and the Muhimbili National Hospital (MNH). MUCHS was a constituent College of the University of Dar es Salaam and in 2007 became an independent university, known as Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences (MUHAS).

Over the years MUHAS has made significant achievements in terms of increased student enrolment and development of several new academic programmes. The Department of Haematology and Blood Transfusion was developed to be responsible for providing diagnosis, care, consultancy and treatment for haematological disorders.

The human resource issue in haematology and blood transfusion

MUHAS is the main public institution in Tanzania responsible for training all cadres of healthcare professionals in Tanzania. It has provided pre-service training in haematology and blood transfusion for doctors, nurses, pharmacists and dentists as well as laboratory technologists at undergraduate and postgraduate level. Despite this, by 2000, Tanzania had one of the lowest doctor/patient ratios in the world, estimated at 2·3 doctors per 100 000 of population. The strategy of the Ministry of Health and Social Welfare of Tanzania was to provide adequate and competent health workers at all levels in management and health service, and MUHAS responded to the human resource crises by increasing the number of trainees at all levels.

However, by 2005, there was a crisis in the Department of Haematology and Blood Transfusion, which had one qualified haematologist, retired but working on contract, three specialists in internal medicine and three medical doctors requiring training in haematology. This was the highest concentration of healthcare professionals specialising and working in haematology and blood transfusion in Tanzania and overall the stark fact was that there was only one trained haematologist in a country of 40 000 000 people. Quite apart from the delivery and development of haematology services, there was a problem of delivery regarding haematology teaching and training to all health staff.

The factors that caused failure to maintain a core of sustainable specialist staff included the regional and international 'brain drain' of medical and nursing staff and depletion of staff through illness, including HIV and failure to invest in medical undergraduate and postgraduate training (Eastwood et al, 2005; Naicker et al, 2009). There was considerable internal migration with few doctors remaining in public teaching and clinical institutions. In addition, the focus on provision of public health and high-profile, special, vertical programmes, such as HIV, with substantial funding that enabled good remuneration and good working conditions, meant that Muhimbili had not been able to attract and retain staff. Monthly wages for a medical doctor with postgraduate specialisation in a public institution were less than $1000 dollars, while in a not-for-profit, non-governmental organisation, the range would be $2000 - $3500 per month. These problems of internal migration that preclude maintaining an adequate core health service cannot be underestimated.

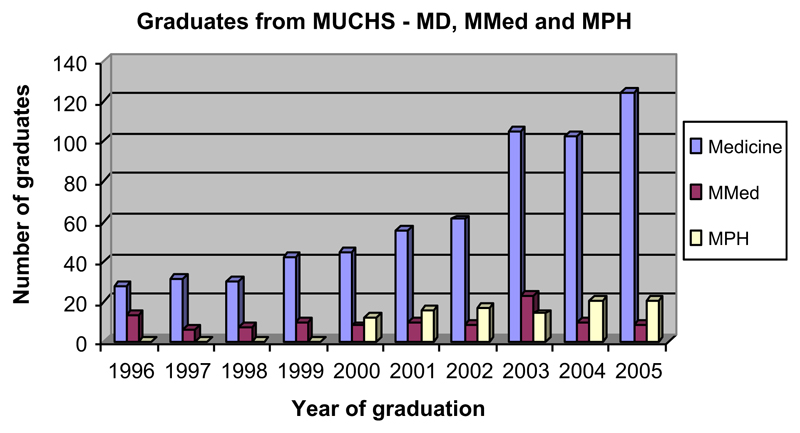

As a consequence of all these factors, both MNH and MUHAS were not able to employ or retain their staff; in 2004, MUHAS had only been able to employ 40% of the lecturers it required to train. The failure of clinical specialities to attract trainees was also reflected in postgraduate training, where between 1975 and 2005, 121 doctors received training in adult and childhood diseases (Internal Medicine and Paediatrics and Child Health) while only two had trained in haematology. In comparison, a postgraduate programme in public health, which started in 2000, has trained 101 public health specialists (Fig 1).

Fig 1.

Graduates from Muhimbili College of Health Sciences for MD, MMed and MPH programmes 1996–2005. MD, Doctor of Medicine; MMed, Master of Medicine; MPH, Master in Public Health; MUCHS, Muhimbili University College of Health Sciences.

Addressing the crises in haematology and blood transfusion

There was therefore an urgent need to develop and strengthen capacity in haematology and blood transfusion, particularly as evidence emerged of the importance of human resources in achieving the Millennium Development Goals (Chen et al, 2004). Capacity-strengthening needed to address three main areas; training, service and research, and simultaneous actions were required for this to be effective and to show significant impact. This need for training requires considerable financial investment and long-term approaches to investment. Unfortunately, this is not attractive to many funding agencies and programmes, which require quick, short-term success. Indeed, most programmes opt to focus on one aspect with realistic, achievable goals at the expense of the other two. For example, vertical programmes in HIV and blood transfusion would involve the establishment of centres and clinics, with training consisting of a series of short workshops and seminars. This approach, whilst achieving certain goals in the short term, e.g. number of workshops conducted or the number of clinics may not result in long-term, sustainable healthcare outcomes. This is illustrated by maternal mortality rates where, despite relatively good indicators and conditions of maternal healthcare (high antenatal clinic attendance rates, comparatively well-developed primary healthcare infrastructure etc.) this has not been accompanied by a reduction of maternal mortality, still estimated at 529–1500 maternal deaths per 100 000 live births. It is probable that better haematology and blood transfusion services are some of the many factors required to improve the quality of complex clinical care needed to reduce maternal mortality.

At Muhimbili we looked to develop active programmes of undergraduate and postgraduate training and professional development for clinical and laboratory staff. We used the training of doctors in haematology and blood transfusion as an example to illustrate the issues that need to be addressed. With the absence of qualified haematologists to provide the training, one option was to send Tanzanians to train outside the country. Table I shows that this approach would be expensive and further deplete services because it involves long periods outside the country. In addition, it may not cover training in clinical issues that are relevant in Tanzania. The alternative solution was based on developing strong clinical and academic links with well-established departments outside Tanzania and would involve trainers coming to Tanzania, complemented by Tanzanians spending short periods in well-established departments. We therefore developed a plan built around these aims.

Table I.

Estimated costs for training in haematology and blood transfusion for doctors.

| Place | Qualification and Duration | Duration | Annual cost (estimated) |

|---|---|---|---|

| UK | MRCP + MRCPath | 3 years + 5 years | $75 000 |

| USA | Internal medicine + haematology haematology/laboratory |

3 years + 4 years 3 years |

$75 000 |

| South Africa | Fellowship (pathology or medicine); certificate | 4 years + 2 years | $25 000 |

| Tanzania | MMed (haematology) | 3 years | $12 000 |

| MMed and MSc | 3 years + 2 years | ||

| West Africa | Fellowship in Haematology | 5 years | $25 000 |

MMed, Master of Medicine; MRCP, Membership of the Royal Colleges of Physicians; MRCPath, Member of the Royal College of Pathologists; MSc, Master of Science.

A new post-graduate training course in haematology and blood transfusion

MUHAS had an established three-year postgraduate training course that lead to a Master in Medicine (MMed). Unfortunately, due to the lack of trainers, this programme could not be offered for over 10 years. In addition, MUHAS was encouraging the development of a two-year programme of super-specialisation for doctors with postgraduate degrees in internal medicine, paediatrics or pathology. Therefore, there was an opportunity to develop a two-year postgraduate training programme leading to a Master of Science (MSc) in Haematology and Blood Transfusion. These two postgraduate programmes, MMed and MSc, were revised and developed with links established with Oxford University (Prof David Roberts and Dr Julie Glanville) and other haematologists from UK institutions, i.e., Whittington Hospital (Dr Bernard Davies and Teresa Marlow), Great Ormond Street Hospital (Dr Amrana Qureshi), Northwick Park Hospital (Dr Cecil Reid) and London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (Dr Sharon Cox, seconded to MUHAS).

A syllabus was developed based on the previous MMed in Haematology and incorporating relevant areas covered in the syllabus for specialist training for the membership of the Royal College of Pathologists for Haematology in the UK. An important part of the training programme was to incorporate a rotation through laboratory and clinical specialties in Tanzania as well as in the UK. There were modules on basic sciences related to haematology and introduction to core clinical and laboratory haematology and specific modules on red cell disorders and bone marrow failure syndromes; blood banking and transfusion medicine; bleeding and thrombotic disorders, haematological malignancies and advanced concepts in haematology and blood transfusion. Lectures were supplemented by seminars and case-based discussion in all these areas. This was an active learning model and students gave case presentations, journal club presentations and seminars, and were supervised and assessed by senior staff.

The formal lectures and seminars were but an introduction to haematology and the core of the course was rotation in laboratory haematology and blood transfusion, clinical haematology, medicine and paediatrics. Students were actively involved in delivering services and clinical care and had specific duties. In the laboratory, they learnt laboratory methods with interpretation of results in routine analysis, morphology, including performing and interpreting bone marrow analysis, coagulation and haemoglobinopathies. During clinical rotations, they were responsible for all haematology patients in the medical and paediatric ward, attended service and teaching ward rounds and presented patients to the weekly Departmental case review and ward rounds. They attended general haematology and sickle cell clinics, coagulation clinics and specialist paediatric sickle cell clinics. This clinical component of the course was innovative for Tanzania and also in comparison with many other courses for haematology in Africa where the focus has largely been on laboratory work. The extensive clinical training mirrors the training of clinical haematologists in the UK and has already allowed expansion of clinical services in haematology, particularly in SCD and paediatric oncology.

Assessments

Students were assessed by completing log-books, continuous assessment tests, end-of-semester examinations, including clinical and laboratory assessments and final written, clinical and laboratory examinations. Internal moderators were recruited from other departments in MUHAS, including paediatrics, internal medicine and pathology; external reviewers for the final examinations are usually from universities in neighbouring countries, for example, the University of Nairobi, Kenya

Development of laboratory services

As training required functioning clinical and laboratory facilities for diagnostic and therapeutic services in haematology and blood transfusion, there were active efforts to improve these areas. This included continuing professional development and in-service training, training visits and short courses and workshops for specific skills, establishment of standard operating procedures for laboratory services and management protocols for clinical care. For example, specific workshops and visits were held for training in high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) testing for haemoglobinopathies and for detection and identification of anti-red cell alloantibodies through visits of expert staff from the UK (Teresa Marlow). This improved standards of healthcare, clinical guidelines and laboratory operating procedures ensuring quality management through audit, evaluation and implementation.

Research projects

One important objective of the post-graduate training was to develop and support active programmes of high quality scientific research in the field of haematology and blood transfusion. Areas of research that could be addressed included anaemia, SCD, haemato-oncological conditions, coagulation and blood transfusion. In addition, it was envisaged that insight into haematological aspects of other research programmes and health fields, e.g. malaria, HIV/AIDS, maternal and child health, would be strengthened. The sickle cell clinical and research project was already underway and has developed further since 2005. The cumulative number of individuals enrolled has increased from 400 in 2005 to 4000 in 2015 (described in more detail in this issue (Tluway & Makani, 2017).

A key part of the overall MMed training was a short research project. Time was allocated for preparation of proposals, submission of ethics, collection and analysis of data and report-writing. Some funding was provided for sample collection and analysis. Topics covered included antenatal screening for SCD, detection and analysis of alloantibodies in sickle cell patients, the incidence and causes of anaemia in HIV and the incidence of anaemia in heart failure. This work was valuable in its own right for learning and preparation for a role as a specialist, which will inevitably involve assessment, commissioning and evaluation of new services and therapies and writing local and national guidelines and policies. Some of these projects have been published (Magesa and Magesa, 2012, 2015; Meda et al, 2014; Rwezaula et al, 2015). Work on SCD and the treatment of iron deficiency in heart disease has led to external funding for newborn screening for SCD and also for advanced post-graduate work for a PhD in the field of iron deficiency and heart disease (Makubi et al, 2014, 2015, 2016).

Further developments of teaching

An initial series of lectures was delivered by visiting specialists in clinical and laboratory haematology from the UK. At all times, it has been essential that MMed students were actively involved in teaching undergraduates, biomedical scientists and nursing staff. Following the graduation of the initial cohort of four MMed and MSc students, the staff of MNH and MUHAS have given an increasing proportion of the lectures and seminars. So now 95% of teaching is done by faculty members from Tanzania. The nucleus of clinical and research work has also attracted other funding and links, and 5% of the faculty is now supported through the American Society of Hematology health volunteers programme.

There have also been long-term haematologists joining the Department from Europe. Initially, a specialist registrar in Haematology (Dr Julie Glanville) was able to spend six months at MUHAS and this was an invaluable start to establishing a clinical rotation. More recently, Professor Lucio Luzzatto (previously Head of Department at Istituto Toscano Tumori, Florence, Italy, The Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Institute, New York, USA and the Hammersmith Hospital, London, UK) has joined the Department and is now teaching and conducting clinical and basic science research. Furthermore, Professor Luzzatto is working with MUHAS to develop a short one week course on Advances in Haematology in Africa which will be provided from 2018 (see editorial in this issue (Roberts et al, 2017).

Exchanges and secondments have not been one-way. At the start of the programme, funding was obtained from the Association of Physicians of Great Britain, Tropical Heath Education Trust (THET) and the Nuffield Department of Medicine, University of Oxford to fund short-term exchanges for MMed, MSc students and senior medical, nursing and laboratory staff with twinned Departments of Haematology at Northwick Park Hospital, the Whittington Hospital, the John Radcliffe Hospital and National Health Service Blood and Transplant, Oxford. These attachments for a month were necessarily limited to observing clinical and laboratory work. However, they offered students an insight into the structure and working of busy clinical departments in the UK. The treatments observed were naturally quite different to those seen and available in Tanzania. However, it was clear that for visitors from Tanzania, it was the teamwork and attention to patient care, more than any technical feature or therapeutic modality that made a lasting impression.

The outcome of the programmes

Overall, 17 medical doctors have enrolled in the MMed and MSc training programmes in Haematology and Blood Transfusion. Ten haematologists have graduated from the course and have been joined by one haematologist trained in South Africa. A further seven students will graduate by 2018 and so will have increased the number of trained haematologists in Tanzania from 1 to 18 in just over a decade.

The haematologists have been able to provide comprehensive clinical care in adult and paediatric haematology and provide consultation and laboratory haematology services for the main teaching hospital in Dar es Salaam (MNH) and graduates from the course are Directors of Laboratory Services and the Clinical Haematology Service at MNH. One haematologist now works for the National Blood Transfusion Service (NBTS) where he is the first member of the NBTS medical staff to be a trained haematologist.

The effects of the programme cascaded onto training courses for other people who work in healthcare. MUHAS and MNH are one of the few centres in East and Central Africa to provide formal postgraduate training in haematology and blood transfusion. The improvement in capacity in training at Muhimbili has improved the quality of the training in haematology and blood transfusion for other healthcare workers at undergraduate and postgraduate level. Given that Muhimbili is responsible for training the largest proportion of healthcare workers in the country, it is anticipated that there has been an overall improvement in the calibre of people who go out and work at all levels of healthcare.

Since the course started, the population of Tanzania has increased from 40 million to 55 million, so in spite of this there still remains, in broad terms, a single haematologist for several million people. There is clearly an enormous unmet need for haematological services outside Dar es Salaam. Through the Ministry of Health of Tanzania and its partners, sickle cell services have been strengthened in Dodoma, Mwanza, Kilimanjaro and Zanzibar. One of the MMed graduates is developing the Haematology Service at Sinza Hospital, Dar es Salaam in the Dar Region and another at the Bugando Hospital and University in Mwanza, Tanzania (Table II).

Table II.

Specialists trained in haematology and blood transfusion in Tanzania.

| Name | Degree | Year of graduation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MSc Super-specialisation. 2-year programme for specialists with postgraduate degree (internal medicine, paediatrics, pathology) | |||

| 1. Abel Makubi | MD, MMed, MSc | 2010 | Haematologist, Department of Haematology, MUHAS |

| 2. Iragi Ngerageza | MD, MMed, MSc | 2017 | |

| 3. Mwajuma Ahmada | MD, MMed, MSc | 2018 | |

| MMed Super-specialisation. 3-year programme for medical doctors | |||

| 4. Alex Magesa | MD, MMed | 2011 | Head, Department of Laboratory Services, MNH |

| 5. Stella Rwezaula | MD, MMed | 2011 | Head, Clinical Haematology Unit, Department of Internal Medicine, MNH |

| 6. Elineema Meda | MD, MMed | 2011 | Haematologist, MNH |

| 7. Abdu Juma | MD, MMed | 2013 | Haematologist, National Blood Transfusion Service |

| 8. Mbonea Yonazi | MD, MMed | 2015 | Haematologist, MNH |

| 9. Samira Mahfudh | MD, MMed | 2016 | Haematologist, Sinza Hospital, Dar es Salaam |

| 10. Neema Budodi | MD, MMed | 2016 | Haematologist, MNH |

| 11. Clara Chamba | MD, MMed | 2016 | Haematologist, Department of Haematology, MUHAS |

| 12. Erius Tebuka | MD, MMed | 2016 | Haematologist, Catholic University of Health and Allied Sciences, Mwanza |

| 13. Flora N. Ndobho | MD, MMed | 2017 | |

| 14. Mwashungi Ally | MD, MMed | 2017 | |

| 15. Oliver Isengwa | MD, MMed | 2017 | |

| 16. Stella Malangahe | MD, MMed | 2017 | |

| 17. Helen Tom | MD, MMed | 2018 | |

MD, Doctor of Medicine; MMed, Master of Medicine; MNH, Muhimbili National Hospital; MSc, Master of Science; MUHAS, Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences.

The MMed and MSc programmes have provided the critical mass of expertise to allow development of services and training in Tanzania. The programme was developed at relatively little cost with approximately £35,000 of external funding (Association of Physicians, THET, Royal Society Conference Grant and Oxford Tropical Network, Nuffield Department of Medicine, University of Oxford) and £90,000 from a UK Department for International Development grant to develop services and facilities to achieve the Millennium Development Goals. The rotation of staff through hospital departments and their clinical work has offset their stipends and salaries while they were training. There was also the considerable advantage that the postgraduate training is directly relevant to the local clinical conditions and the course work, through laboratory and ward work, discussions and research projects, directly contributed to immediate and future care of patients.

The total cost and effort of setting up the programme has been rewarded by a self-sustaining cadre of haematologists who can now train future postgraduate medical staff, undergraduates, nursing staff and laboratory staff. This critical mass will now allow the Department to chart its own course as new opportunities and priorities arise. As Tanzania has long promoted sustainable development, it is fitting that MUHAS and MNH have built a sustainable programme for postgraduate training.

Limitations of the programme

There were administrative and organisational hurdles to set up a clinical rotation, as this was a new concept for a discipline that was previously seen as a laboratory specialty. However, these were soon addressed and adding the clinical component has allowed clinical services to expand, with the establishment of a clinical haematology unit in the Department of Internal Medicine at MNH.

The initial concept of the programme, gaining external funding and maintaining the programme, would perhaps have been difficult for a department that was not so actively engaged in research work that draws on very significant external funding. However, a substantial, but less ambitious programme, could be replicated in other specialties. There is a pressing need in many areas among medical specialties, such as nephology and neurology, and in other areas that are crucial for clinical care, such as anaesthesia, where there are just a handful of specialists in the country. This situation is similar throughout sub-Saharan Africa. For example, there are few nephrologists in sub-Saharan Africa, with many countries having <1 nephrologist per million population; some have no nephrologists at all (Naicker et al, 2010).

Developing a large number of medical specialists is not the sole objective of a programme of medical education. There must always be a concern about the concentration of medical specialist in large centres and a uneven distribution of healthcare. This has been a perennial problem, highlighted by the polemic and persuasive book 'Health Care for the Developing World' by Maurice King (King, 1967) and these concerns were at the heart of the movement for Primary Health Care and Health for All by the Year 2000, envisioned by Halfdan Mahler and Ken Newell nearly half a century ago (Brown et al, 2016). The central element of the Primary Health Care movement was that healthcare should be appropriate, affordable and accountable. Development of specialist services is now relevant, achievable and has significant impact on clinical care. It seems now that developing specialist services locally to address the increasingly complex care of a progressively more urban population is in the spirit of these principles (Makani & Roberts, 2016).

The programme of medical education in Haematology has benefited healthcare in Tanzania across a broad range of areas and may be a helpful example for other locations and other specialties.

Acknowledgements

This work would not have been possible without the enormous contribution in teaching from Dr Bernard Davis and Teresa Marlow, Dr Cecil Reid, Dr Amrana Qureshi, Dr Julie Glanville, Dr Claire Hutchinson, Dr Trish Scanlan, Dr Sharon Cox and Professor Lucio Luzzatto. We would also like to thank the medical, nursing and laboratory staff and MUHAS and MNH who have helped to develop and support this programme, including senior university and hospital staff, particularly Dr James Rwehabura. This work was funded by the Association of Physicians, the Royal Society, the Royal College of Physicians, THET, Tropical Health Network at Oxford University, Department for International Development (UK) and American Society of Hematology. The work was supported by the British Society of Haematology, National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Oxford Biomedical Research Centre Haematology Theme at Oxford University Hospitals and NHS Trust and the University of Oxford. Finally, we would like to thank Wendy Slack for her administrative support during the programme and her careful editing.

References

- Brown TM, Fee E, Stepanova V. Halfdan Mahler: Architect and Defender of the World Health Organization “Health for All by 2000” Declaration of 1978. American Journal of Public Health. 2016;106:38–39. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Evans T, Anand S, Boufford JI, Brown H, Chowdhury M, Cueto M, Dare L, Dussault G, Elzinga G, Fee E, et al. Human resources for health: overcoming the crisis. Lancet. 2004;364:1984–1990. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17482-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clyde DF. A History of Medical Services in Tanganyika. Government Publishing House; Dar-es-Salaam, Tanzania: 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Eastwood JB, Conroy RE, Naicker S, West PA, Tutt RC, Plange-Rhule J. Loss of health professionals from sub-Saharan Africa: the pivotal role of the UK. Lancet. 2005;365:1893–1900. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66623-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GBD 2015 Child Mortality Collaborators. Global, regional, national, and selected subnational levels of stillbirths, neonatal, infant, and under-5 mortality, 1980–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 2016;388:1725–1774. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31575-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King M. Medical Care in Developing Countries. Oxford University Press; Tanzania: 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Magesa AS, Magesa PM. Association between anaemia and infections (HIV, malaria and hookworm) among children admitted at Muhimbili National Hospital. East African Journal of Public Health. 2012;9:96–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magesa AS, Magesa PM. Association of anaemia with micronutrient (iron, folate and vitamin B12) deficiencies among children admitted at Muhimbili National Hospital in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. East African Journal of Public Health. 2015;11:889–895. [Google Scholar]

- Makani J, Roberts DJ. Hematology in Africa. Hematology/Oncology Clinics of North America. 2016;30:457–475. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2015.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makubi A, Hage C, Lwakatare J, Kisenge P, Makani J, Rydén L, Lund LH. Contemporary aetiology, clinical characteristics and prognosis of adults with heart failure observed in a tertiary hospital in Tanzania: the prospective Tanzania Heart Failure (TaHeF) study. Heart. 2014;100:1235–1241. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2014-305599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makubi A, Hage C, Lwakatare J, Mmbando B, Kisenge P, Lund LH, Rydén L, Makani J. Prevalence and prognostic implications of anaemia and iron deficiency in Tanzanian patients with heart failure. Heart. 2015;101:592–599. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2014-306890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makubi A, Hage C, Sartipy U, Lwakatare J, Janabi M, Kisenge P, Dahlström U, Rydén L, Makani J, Lund LH. Heart failure in Tanzania and Sweden: Comparative characterization and prognosis in the Tanzania Heart Failure (TaHeF) study and the Swedish Heart Failure Registry (SwedeHF) International Journal of Cardiology. 2016;220:750–758. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.06.239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meda E, Magesa PM, Marlow T, Reid C, Roberts D, Makani J. Red blood cell alloimmunization in sickle cell disease patients in Tanzania. East African Journal of Public Health. 2014;11:775–780. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naicker S, Plange-Rhule J, Tutt RC, Eastwood JB. Shortage of healthcare workers in developing countries – Africa. Ethnicity & Disease. 2009;19(Suppl. 1):S1-60–S1-64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naicker S, Eastwood JB, Plange-Rhule J, Tutt RC. Shortage of healthcare workers in sub-Saharan Africa: a nephrological perspective. Clinical Nephrology. 2010;74(Suppl. 1):S129–S133. doi: 10.5414/cnp74s129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Njelesani J, Dacombe R, Palmer T, Smith H, Koudou B, Bockarie M, Bates I. A systematic approach to capacity strengthening of laboratory systems for control of neglected tropical diseases in Ghana, Kenya, Malawi and Sri Lanka. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2014;8:e2736. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts DJ, Field S, Delaney M, Bates I. Problems and approaches for blood transfusion in the developing countries. Hematology/Oncology Clinics ofNorth America. 2016;30:477–495. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2015.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts DJ, Cooper N, Bates I. Haematology in lower and middle income countries. British Journal of Haematology. 2017 doi: 10.1111/bjh.14639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rwezaula SS, Magesa PM, Mgaya J, Massawe A, Newton CR, Marlow T, Cox SE, Gallivan M, Davis B, Lowe B, Roberts D, Makani J. Newborn screening for hemoglobinopathies at Muhimbili National Hospital, Dar es Salaam –Tanzania. East African Journal of Public Health. 2015;12:948–955. [Google Scholar]

- Tluway A, Makani J. Sickle cell disease in Africa: An overview of the integrated approach to health, research, education and advocacy in Tanzania, 2004-2016. British Journal of Haematology. 2017 doi: 10.1111/bjh.14594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Liddell CA, Coates MM, Mooney MD, Levitz CE, Schumacher AE, Apfel H, Iannarone M, Phillips B, Lofgren KT, Sandar L, et al. Global, regional, and national levels of neonatal, infant, and under-5 mortality during 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet. 2014;384:957–979. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60497-9. Erratum in: Lancet. (2014) 384,956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]