Abstract

Glucuronidation is the most important phase II metabolic pathway which is responsible for the clearance of many endogenous and exogenous compounds. To better understand the elimination process for compounds undergoing glucuronidation and identify compounds with desirable in vivo pharmacokinetic properties, many efforts have been made to predict in vivo glucuronidation using in vitro data. In this article, we reviewed typical approaches used in previous predictions. The problems and challenges in prediction of glucuronidation were discussed. Besides that different incubation conditions can affect the prediction accuracy, other factors including efflux / uptake transporters, enterohepatic recycling, and deglucuronidation reactions also contribute to the disposition of glucuronides and make the prediction more difficult. PBPK modeling, which can describe more complicated process in vivo, is a promising prediction strategy which may greatly improve the prediction of glucuronidation and potential DDIs involving glucuronidation. Based on previous studies, we proposed a transport-glucuronidation classification system, which was built based on the kinetics of both glucuronidation and transport of the glucuronide. This system could be a very useful tool to achieve better in vivo predictions.

Keywords: Glucuronidation, Prediction, Transporter, PBPK, Transport-Glucuronidation Classification System

1. Introduction

In drug discovery and early development, predicting ADME properties (absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion) of new drug candidates is always very important before moving forward into clinical trials. Accurate prediction can eliminate compounds with undesirable properties in early-stage of drug discovery. The prediction of human pharmacokinetics from preclinical data can greatly facilitate the first-in-human studies and be used as the guidance for designing dosing regimens in mid- to late-stage drug development. Adverse pharmacokinetic and bioavailability, which was the most significant cause of attrition in the clinic in 1991 (accounted for ~40% of all attrition), contributed much less by 2000 (less than 10%) due to a better application of in vitro ADME prediction tools as well as modeling approaches (e.g. PK/PD modeling) (1).

Glucuronidation, which is catalyzed by UDP-glucuronosyltransferases (UGTs), is a major metabolism and detoxification pathway of drugs in humans and in mammals. It was reported in 2002 that glucuronidation is an important clearance mechanism for approximately 1 in 10 of the top 200 prescribed drugs. As an example, raloxifene, a drug widely used in treating osteoporosis, has 2% bioavailability due mainly to extensive in vivo glucuronidation (2).

UGTs are a superfamily of membrane bound proteins located in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) of the cells of various tissues. In humans, UGTs are classified into four subfamilies, UGT1,UGT2,UGT3, and UGT8 (3). Although there have been relatively fewer studies predicting in vivo glucuronidation compared to predictions for phase I metabolism via cytochrome P450 (or CYPs), some attempts have been made to predict hepatic and intestinal glucuronidation catalyzed by UGT using in vitro-in vivo extrapolation (IVIVE) (4-7).

In this review article, we reviewed the challenges and potential opportunities for the prediction of in vivo glucuronidation from in vitro data. Specifically, we reviewed the role of transporters in the disposition of glucuronide conjugates, which can explain why relying on microsomes alone can often lead inaccurate predictions. Modeling approaches have been applied for the prediction of transporter-mediated disposition of glucuronide metabolites in some recent studies, which are also reviewed in this article. We believe that for the future studies, more attention should be paid to the application of physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling, which is able to incorporate impacts from both enzymes and transporters, therefore improving the prediction of in vivo phase II metabolism via glucuronidation.

2. Glucuronidation Reaction

Glucuronidation is the most important phase II metabolism pathway. In human, glucuronidation constitutes 40%-75% or more of xenobiotics elimination including most of the clinically used drugs (8). Furthermore, the regulation of several important endogenous compounds such as bilirubin, bile acid and hydroxysteroids also depends on glucuronidation (8, 9). The broad spectrum of both endobiotics and xenobiotics provides a high potential of glucuronidation-related DDIs. There are also clinical evidence showing the potential DDIs for drugs undergoing glucuronidation in humans. For example, it was shown that cisapride decreased the Cmax of acetaminophen glucuronide and increased the systemic exposure of acetaminophen (10). In addition, it was reported that the co-administration of probenecid decreased the urinary excretion of acetaminophen glucuronide in humans (11). So the understanding and prediction of glucuronidation in vivo is crucial for human health. Since 2012, FDA has put UGTs into their guidance for industry about drug interaction study. Drugs with over 25% of glucuronidation metabolism in total metabolism may be required to determine drug-drug interaction (DD) potential due to UGT-based mechanisms.

Human UGTs exhibit a broad tissue distribution. Liver is the major organ with many expressed UGTs. Total UGT mRNA expression in the small intestine is one-seventh of the liver (8). Most of the UGTs 1 and 2 are expressed in human liver, including UGT 1A1, 1A3, 1A4, 1A6, 1A9, 2B7, and 2B15, whereas UGT 1A5, 1A7, 1A8, 1A10 and 2A1 are extrahepatic UGT forms. Besides hepatic distribution, many UGTs 1A and UGTs 2B are also expressed in kidney, small intestine, colon, stomach, lung, epithelium, ovary, testis, mammary glands and prostate (2, 8, 12). For example, UGT 1A10 and 1A8 are specifically expressed in the intestine. High levels of UGT 2B15, 2B17 and 1A6 are also detected in stomach. UGT 2B7, 1A9 and 1A6 are found in the kidneys (8, 13). Among all the UGTs, UGT 1A and 2B subfamilies are responsible for nearly all of the drug metabolism (13).

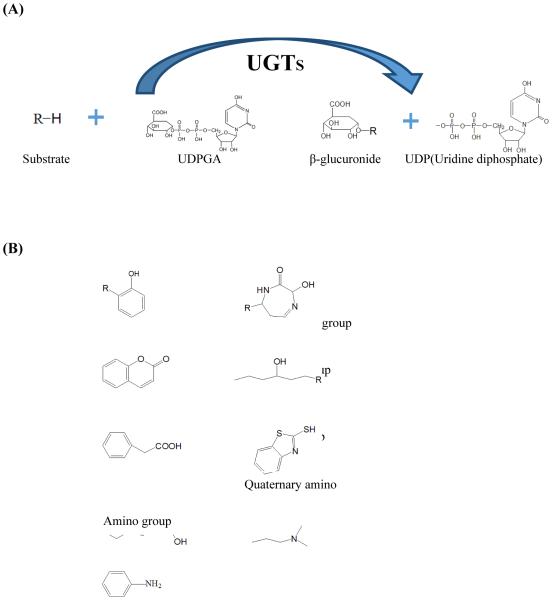

The glucuronidation reaction is catalyzed by UDP-glucuronosyltransferases (UGTs). Urindine-5’-diphospho-α-D-glucuronic acid (UDPGA) is the most important co-substrate in glucuronidation reaction. During the reaction, UDPGA acts as a glucuronic acid donor and the glucuronic acid is transferred to another nucleophilic atom (S, O, N, C etc.) in acceptor molecular (8, 13). O-linked moieties (hydroxyl, acyl and phenolic groups etc.) are the most preferred functional groups in the reaction. After the glucuronidation, the glucuronide has highly increased hydrophilicity. Figure 1 (A & B) shows the glucuronidation reactions and preferred chemical structures for glucuronidation.

Figure 1.

Glucuronidation reaction (A) and preferred chemical structures for glucuronidation (B).

3. Prediction of Glucuronidation Using Classical Extrapolation: Problems and Solutions

Several approaches have been developed to predict in vivo glucuronidation from in vitro metabolism data using microsomes, hepatocytes, or recombinant enzymes. Liver microsomes and hepatocytes are commonly used in vitro tools for metabolic studies. The intrinsic clearance (expressed as per milligram of microsomal protein or per million cells) generated from in vitro metabolism experiments can be converted using physiological parameters (microsome yield, hepatocellularity per gram of liver, and liver weight) to derive the scaled whole liver intrinsic clearance (CLint). The whole liver CLint is then substituted in the equation for a physiological model of hepatic clearance, most via the widely-used well-stirred model (14-16):

Other models were also used for the prediction of hepatic clearance, including the parallel-tube model and the dispersion model (eq. 2-3) (17, 18), which were reviewed elsewhere (5, 7). In some studies, data from microsomes and hepatocyte studies can be extrapolated reasonably well to in vivo pharmacokinetics by using appropriate models. For example, in a recent study, in vitro data generated using rat liver microsomes were used to predict in vivo intrinsic clearance by rat haptic UGTs for a series of drugs. It has been shown that out of 10 drugs, a good in vitro-in vivo correlation was observed for 7 drugs (19).

| eq. 1 |

| eq. 2 |

| eq. 3 |

Where CLh is hepatic clearance, Qh is hepatic blood flow, and fu represents the fraction of the drug unbound in blood. Dn (axial dispersion number) could be taken as 0.17.

However, in many studies, the hepatic microsomal values for glucuronidation of tested compounds were usually reported to be lower than their in vivo intrinsic clearance values. For instance, the in vitro glucuronidation parameters obtained from rat intestinal and hepatic microsomes were found to be 10- to 30-fold lower than the in vivo parameters, although the rank order was the same (20). In another study, extrapolation of human liver microsomal data underestimated (6.5- to 23-fold) in vivo hepatic clearance of zidovudine by glucuronidation, irrespective of different incubation conditions and mathematical models (21). Soars et al. evaluated the prediction accuracy of using human microsomes and hepatocytes to derive glucuronidation clearance for 11 drugs. It was observed that the liver microsomal data resulted in about 10 fold underprediction of in vivo glucuronidation, whereas data from hepatocytes yielded a more accurate prediction (22). In regards to using animal models to predict human UGT metabolism, studies were performed for 12 drugs that were directly metabolized by UGTs in mice, rats, monkeys, or dogs. It was shown that for more than 50% of tested drugs, the glucuronidation clearance in humans were predicted within 3-fold of actual values using allometric scaling approaches (23). A summary of previous studies in prediction of glucuronidation using in vitro tools is shown in Table 1 (19-22, 24-43).

Table 1.

Prediction of in vivo glucuronidation from in vitro data using different models

| Model | In vitro tools |

Compounds | Remark | Reference s |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Well stirred |

Human liver bmicrosom es |

Dihydroartemisinin | 8-fold underprediction |

22 |

| Buprenorphine, Mycophenolic acid, Naloxone, Quercetin, Gemfibrozil |

5-fold underprediction |

23 | ||

| Raloxifene, Troglitazone | 30-fold underprediction |

23 | ||

| Zidovudine | 6-fold underprediction |

19 | ||

| Codeine, Ethinylestradiol, Furosemide, Gemfibrozil, Imipramine, Ketoprofen, Morphine, Naloxone, Naproxen, Propofol, Valproic acid |

10-fold underprediction |

20 | ||

|

| ||||

| Human hepatocyt es |

Codeine, Ethinylestradiol, Furosemide, Gemfibrozil, Imipramine, Ketoprofen, Morphine, Naloxone, Naproxen, Propofol, Valproic acid |

Good prediction | 20 | |

|

| ||||

| Rat liver/intes tine microsom es |

Morphine, Naloxone, Buprenorphine |

10- to 30-fold underprediction |

18 | |

|

| ||||

| Dispersi on |

Human liver microsom es |

Zidovudine | 6-fold underprediction |

19 |

| Naloxone | 63-fold underprediction |

19, 40, 41 | ||

| Propofol | 350-fold underprediction |

19, 24, 25, 41 | ||

| Morphine | 8-fold underprediction |

19, 26, 27, 41 | ||

| Paracetamol | 4-fold underprediction |

19, 28-30 | ||

| Amitriptyline | 3.5-fold underprediction |

19, 31, 32 | ||

| Lamotrigine | 3.5-fold underprediction |

19, 33-35 | ||

| Clofibric acid | Good prediction | 19, 36-38 | ||

| Valproic acid | 1-fold underprediction |

19, 39, 41 | ||

|

|

||||

| Rat liver microsom es |

Zidovudine | 1.5-fold underprediction |

17 | |

| Telmisartan | 75-fold underprediction |

|||

| Ezetimibe, Naloxone, Raloxifene, Gemfibrozil, Diclofenac, Naproxen |

Good prodiction (<1 fold difference) |

|||

|

| ||||

| Parallel tube |

Human liver microsom es |

Zidovudine | 6-fold underprediction |

19 |

Several attempts have been made to improve the predictions. For example, recent studies showed that the predicted and known in vivo clearances by glucuronidation of 14 drugs were significantly correlated when the in vivo clearances were scaled from the intrinsic clearance in liver microsomes using dispersion model, suggesting that applying a scaling factor might be useful to make a more reasonable prediction (44). However, further validation is required to apply this approach for a wider range of drugs or compounds. Another proposed explanation for the general trend of under-prediction was that the unsaturated fatty acid released from microsomal membranes was demonstrated to act as an inhibitor of UGTs, and the addition of BSA (bovine serum albumin) had been shown to eliminate the inhibitory effects by sequestering the fatty acids (45). However, even in the presence of BSA, a large discrepancy (~20-fold under-prediction) between the predicted and actual glucuronidation clearance was still observed (19). These findings suggest that additional factors are involved in the inaccurate predictions.

Because of the hydrophilicity of glucuronide conjugates, they cannot across the cell membrane by passive diffusion. Therefore, the involvement of transporters was suggested as effective clearance pathway for glucuronide conjugates. Furthermore, the transport of glucuronides is a critical process for enterohepatic circulation, which is very common for compounds undergo phase II metabolism via glucuronidation and sulfonation. There was much evidence suggesting that the altered systemic exposure to glucuronide conjugates may not be the result of changed enzyme activities, but the result of the polar distribution of glucuronides by their efflux transporters (46-51). We believe that the consideration of transport in addition to metabolism would greatly improve the prediction of glucuronide exposures in vivo.

4. Transporters for Glucuronide Metabolites

4.1 Efflux Transporters for Glucuronide Metabolites

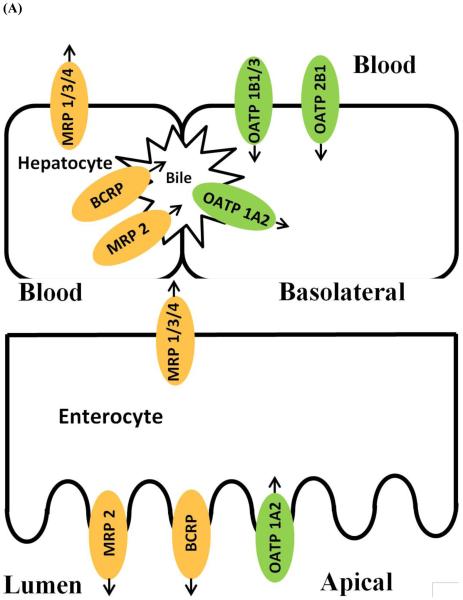

Breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP) and multidrug resistance proteins (MRPs) belong to the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) family. MRP1, MRP3 and MRP4 are expressed on the basolateral membrane of enterocytes and sinusoidal membrane in hepatocytes, whereas BCRP and MRP2 is localized to the apical membrane of enterocytes, canalicular membrane of hepatocytes, and the apical membrane of the proximal tubules of the kidney (52-55).

In published reports, many glucuronide conjugates were demonstrated to be substrates of efflux transporters including BCRP and MRP 1/2/3/4 (48, 56-59). These efflux transporters function as efflux pumps to extrude intracellular conjugates and facilitate their excretion into the lumen and bile or uptake into the blood. In membrane vesicles prepared from HEK293 cells transfected with BCRP, 17β-estradiol 17-(β-D-glucuronide) (E217βG) was found to be substrate of BCRP with Km and Vmax values of 44.2 μM and 103 pmol/mg/min respectively (60). 7-Ethyl-10-hydroxycamptothecin glucuronide (SN- 38-glucuronide) was shown as a substrate of BCRP with Km and Vmax values of 26 mM and 833 pmol/mg/min, respectively (61). Besides glucuronide metabolites of drugs, many flavonoid glucuronides were shown to be substrates of BCRP (62-64) . In UGT1A9-overexpressing HeLa cells, the efflux kinetics by BCRP of 13 flavonoid glucuronides were studied (63).

In the vesicular transport studies, mycophenolic acid glucuronide (MPAG) and gemfibrozil glucuronide were demonstrated to be substrate for MRP2, MRP3, and MRP4 (65-67). And as shown in hepatocytes, the canalicular efflux of MPAG was mainly mediated by MRP2 (68). Furthermore, it had been found that MRP2 is the major transporter involved in the urinary excretion of MPAG (69). More evidences in vesicular transport and ATPase activity studies have shown that E217βG , bisphenol A glucuronide, and ethinylestradiol glucuronide (EEG) are substrates of MRP3 (57, 70, 71). A number of flavonoid glucuronides were also identified as MRP substrates in different in vitro systems. For example, experiments in membrane vesicles overexpressing transporters suggested that 7-hydroxycoumarin glucuronide was substrate of both MRP3 and MRP4 (72). In Caco-2 cells, selective MRP inhibitors LTC4 and MK-571 were used to identify efflux transporters for emodin glucuronide, and the results suggested that MRP2 and possibly MRP3/4 transporters are involved in transporting emodin glucuronide (73). Baicalin, which is the glucuronide metabolite of baicalein, was suggested to be transported to the apical side by MRP2 in Caco-2 cells (74).

Some glucuronides are substrates of both BCRP and MRP transporters. In studies using inside-out membrane vesicles, BCRP and MRP1-3 were all capable of transporting baicalin (75). BCRP, MRP2, and MRP3 were also found to mediate the efflux of diclofenac glucuronide in a membrane vesicle experiment (76). In transfected HeLa cells, it was suggested that BCRP, MRP1, MRP3, and MRP4 are all involved in the excretion of chrysin glucuronide (77).

4.2 Uptake Transporters for Glucuronide Metabolites

Solute carrier (SLC) transporters are known to be responsible for mediating the uptake of a broad range of substrates into cells (78). Organic anion transporting polypeptides (OATPs), organic cation transporters (OCTs), and organic anion transporters (OATs) belong to SLC superfamily.

Among these transporters, OATP1B1/3, Oatp1b2 (rodent protein), OATP1A2, and OATP2B1 as well as OAT1-4 are known to transport glucuronide conjugates. In enterocytes, OATP1A2 is expressed on the brush border membrane, while it is mainly found in the epithelial cells of the bile duct in liver and involved in the reabsorption process. OATP1B1 and OATP1B3 were found to be expressed selectively in the basolateral membrane of hepatocytes. OATP2B1 is also widely distributed throughout the body with the highest expression levels in the basolateral membrane of hepatocytes. OAT1-4 are mainly distributed in kidney and localized to the basolateral membrane of proximal tubules (78-80). Figure 2 summarizes efflux / uptake transporters for glucuronide conjugates in hepatocytes and enterocytes.

Figure 2.

Transporters involved in the transport of glucuronide in hepatocytes (A) and enterocytes (B).

Many glucuronides were identified as substrates of SLC transporters. In transfected human embryonic kidney (HEK) cells, the uptake of E217βG and MPAG was demonstrated to be mediated by OATP1B1 and OATP1B3 (81, 82). Uptake studies in cDNA-injected oocytes suggested that E217βG is a substrate for OATP1A2 as well (83). In OATPs transfected HEK cells, gemfibrozil glucuronide was confirmed to be transported by OATP1B1, 1B3, and 2B1 (67). A recent study showed that daidzein-7-glucuronide was also transported by OATP2B1 (84). In OAT1/3 or OCT2 transfected HEK cells, OAT3 was identified as the only transporter mediating the uptake of morinidazole glucuronide (85). The glucuronide metabolite of sorafenib was also identified as a substrate of OATP1B1, Oatp1b2, and OATP1B3 in transfected HEK cells (86). Similarly, ezetimibe glucuronide was proven to be a substrate for OATP1B1 and OATP2B1 (87), and diclofenac acyl glucuronide was identified as a substrate for a series of uptake transporters including OAT1-4, OATP1B1, and OATP2B1 (76).

5. The Impact of Transporters on Pharmacokinetics of the Glucuronide Conjugates In Vivo

5.1 Transporters-Mediated Excretion of Glucuronides

In small intestine, efflux transporters play important role in extruding glucuronide conjugates into the lumen. In enterocytes, MRP2 and BCRP are responsible for the efflux of 4-methylumbelliferone glucuronide (4MU-G) into the lumen, which was demonstrated by in situ intestinal perfusion experiments in rats and mice (88). In Bcrp1 knockout mice, the excretion rates of genistein glucuronide in small intestine decreased significantly, suggesting BCRP is the major efflux transporter mediating the excretion of genistein glucuronide in the mouse intestine (89).

In the livers from Mrp3 knockout mice, the basolateral excretion of acetaminophen glucuronide (APAP-G), 4MU-G, and harmol glucuronide was reduced by 96%, 85%, and 40%, respectively (48). In rodent model of fatty liver disease, a reduction in the biliary excretion of APAP-G and an increase in its plasma and urine concentrations were observed. And the altered distribution of APAP-G was attributed to the increased protein level of Mrp3 in liver (90). For diclofenac acyl glucuronide, MRP2, BCRP, and MRP3 were suggested to be involved in the biliary excretion or efflux to blood from hepatocytes. In Mrp2 or Bcrp1 deficient mice, the biliary excretion of diclofenac acyl glucuronide decreased, while its levels in plasma and liver increased (49). In rat, the biliary excretion of baicalin decreased remarkably in the presence of MK571, which is a potent MRP inhibitor (75). Studies in rats showed that the biliary excretion of the glucuronide metabolites of flavopiridol is mainly mediated by MRP2 (91). The role of MRP2 in disposition of EEG was demonstrated in Mrp2-deficient rats and mice. The blood exposure of EEG increased >100-fold and 46-fold in Mrp2-knockout rats and mice respectively, while the excretion of EEG in intestine and bile decreased substantially (46).

Enteric and enterohepatic circulation can be influenced not only by the formation of metabolites, but also by the membrane transporters. As it was observed for many flavonoids, genistein undergoes highly efficient enterohepatic circulation. The cumulative recovery of radiolabeled genistein over a 4-hour period in bile was about 70% of the dose (92). And as it was mentioned previously, transporters such as BCRP located at the apical membrane of enterocytes as well as the canalicular side of hepatocytes facilitate the process of enteric and enterohepatic circulation. Our previous studies suggested that the in vitro glucuronidation rates derived from microsomes fails to predict the amount of glucuronide conjugates excreted into the intestine or bile. Therefore, it was concluded that a better understanding of the transporters involved in the efflux of glucuronides in intestine and liver is required to predict the disposition of flavonoids via enteric recycling more accurately (93, 94). One of our recent studies showed direct evidence that the hepatic uptake and biliary excretion serve as very efficient clearance mechanisms for flavonoid glucuronides. And this transporter-mediated (both uptake and efflux) process enables efficient enterohepatic recycling and prolongs flavonoid’s half-life in vivo (95). In clinical studies, it was shown that in patients with impaired OATP1B1 activity, there was less hepatic uptake of MAPG and reduced enterohepatic recycling of MPA, and therefore, less MPA-related toxicity (96).

Transporters also mediate the excretion of glucuronide in kidney. For example, in kidney perfusion studies in Mrp2 deficient rats, a 50% reduction in MAPG excretion indicated that MRP2 is the major transporter involved in renal MAPG excretion (69).

5.2 Interplay of Efflux Transporters, Uptake Transporters, and UGT Enzymes

There is a strong interplay between glucuronidation enzymes and transporter involved in moving the glucuronides across the cell membrane. In our previous studies of the interplay between enzyme and efflux transporters, we noticed a discrepancy between the intestinal excretion of glucuronide conjugates and the activities of UGT enzymes for several compounds. Based on this observation, we proposed the “revolving door” theory. In this theory, we believe that phase II metabolites depend on efflux transporters to exit the cells, and inefficient “revolving door” could result in poor excretion of the phase II metabolites (97). Furthermore, engineered HeLa cell stably overexpressing UGT1A9 was developed as a simple cell model to study the kinetic interplay between UGT1A9 and BCRP in the disposition of glucuronide conjugates (98). It was found that glucuronides with lower efflux rates via BCRP than UGT1A9-mediated metabolism rates tend to accumulate inside the cells (63). In the same cell model, recent studies revealed that the knock-down of BCRP or MRP transporters not only led to substantial reduction in excretion of glucuronides, but also decreased cellular glucuronidation of genistein and apigenin. This suggests that the glucuronidation activities can be influenced by the expression levels of efflux transporters (99). Fahrmayr, C., et al. developed triple-transfected MDCK-OATP1B1-UGT1A1-MRP2 cell line and delineated the interplay between transporter-mediated uptake, glucuronidation and efflux involved in phase II disposition of ezetimibe (100).

There is also an interplay among different transporters, which makes the prediction of glucuronide metabolites more complicated. “Hepatocyte hopping”, a novel concept proposed by Schinkel’s group, describes a phenomenon that hepatic uptake transporters (OATP1A/1B) work in concert with the basolaterally located efflux transporter (MRP3) to mediate the liver-to-blood shuttling loop. Their studies suggested that “hepatocyte hopping” serves as a detoxification mechanism for drugs (e.g, sorafenib) that undergo hepatic glucuronidation (50, 101).

5.3 Transporters-Mediated Drug-Drug Interactions for Glucuronides

Previously, studies have shown that glucuronidation can be inhibited or induced by some drugs, which may cause UGT-mediated drug interactions. In recent studies, there is more evidence demonstrating that some drugs are also transporter modulators and the interactions are the results of the impacts on both enzymes and transporters. Probenecid, for instance, is commonly involved in drug interactions. It is not only an inhibitor of glucuronidation, but also it has impacts on transport of glucuronides (102).

In rat, when probenecid was coadministered with CPT-11, the biliary excretion of SN-38 glucuronide decreased about 50%, whereas a slight increase in plasma concentration of SN-38 glucuronide was observed (103). Bilirubin-glucuronides are known as endogenous substrates for MRP2 and MRP3. In sandwich cultured rat hepatocytes, rifampicin and probenecid were demonstrated to reduce the excretion of bilirubin-glucuronides to the canalicular side and stimulate the sinusoidal efflux through modulating the activity of MRP2 and MRP3 at the same time. On the other hand, indomethacin and benzbromarone inhibited both canalicular and sinusoidal efflux of bilirubin glucuronide, resulting decreased excretion of bilirubin glucuronide in rat hepatocytes (104). In humans, studies have shown that there is an interaction between MPA and rifampin, which results in a significant decrease in AUC of MPA and an increase in MPAG exposure. The interaction was explained by the induction of MPA glucuronidation and inhibition of MRP2-mediated transport by rifampin (105). The coadministration of MPA and cyclosporine A (CsA) resulted decreased exposure of MPA in humans, and inhibition of canalicular and sinusoidal efflux as well as the basolateral uptake of MPAG was demonstrated to be the mechanism of interaction (106). E217βG, which is a substrate of both MRP2 and MRP3, is often used in drug interaction studies. Because of the fact that MRP2 has two binding sites for E217βG, heterotropic cooperativity has been observed for some modulators at certain concentrations, which potentiates the transport of E217βG by MRP2. It was reported that in the presence of MRP2 modulators (indomethacin, probenecid, and benzbromarone), the biliary efflux of E217βG increased significantly in rats (107).

6. Mechanistic Modeling of Glucuronide Disposition

6.1 In Vitro Models

As stated above, a glucuronide is usually a substrate for several transporters, which makes the disposition of glucuronide a more complicated process. A few simple cell models with expression of a specific transporter were developed and applied as the first step to study the role played by a single efflux transporter in the disposition of glucuronides. The engineered HeLa cells overexpressing UGT1A9 was developed and demonstrated to be an appropriate model to evaluate the kinetics of glucuronides efflux by BCRP (56, 98). In this cell model, the kinetic parameters of BCRP-mediated glucuronide efflux were determined by the measurement of intracellular glucuronide concentrations and the corresponding excretion rates of glucuronides (56). It was suggested that both a compound’s susceptibility to glucuronidation by the UGT enzyme and the resulting glucuronide’s affinity to efflux transporter determined a compound’s susceptibility to glucuronidation in cells (63). Rat SCH lacking Bcrp (using adenoviral vectors expressing shRNA targeting Bcrp) and/or Mrp2 (from Mrp2-knockout rat) was also used previously to study the interplay between the formation of a glucuronide and its excretion by specific transporter (s) (108).

A few cellular pharmacokinetic models have been developed and applied for more complicated situations. For example, a cellular model delineating the in vitro hepatic disposition of MPAG had been built based on experiments in sandwich-cultured human hepatocytes (SCHH). This model provided useful information for determining the role of basolateral uptake, basolateral efflux, intracellular glucuronidation and biliary excretion process in the distribution of MPAG (66). Furthermore, this cellular pharmacokinetic model was applied to explore and predict transporter-mediated DDIs between MPA and CsA (106). Similarly, a mechanistic model involving basolateral efflux, canalicular efflux and glucuronidation was developed to determine the disposition kinetics of gemfibrozil and gemfibrozil glucuronide in SCHH (67).

6.2 PBPK Modeling Approach: New Opportunities for the Prediction of In Vivo Glucuronidation

PBPK modeling approaches have increasingly been used to predict pharmacokinetics and DDIs in vivo. PBPK modeling can be an extremely useful tool to investigate and predict the disposition of aglycones and its glucuronide metabolites. Instead of simple scaling from in vitro data, transporters, deglucuronidation, and enterohepatic circulation can be incorporated in PBPK models. Pang et al. suggested that PBPK models in liver, intestine and kidney incorporating membrane barriers and transporters could be useful to explain the fate of metabolites in vivo (109). Recently, the biliary and urinary excretion of morphine glucuronide in rats was well described in an intestinal segregated-flow (SFM) model nested within a PBPK model, which consists of transport and metabolic pathways of morphine and morphine glucuronide (110).

In PBPK models, components other than transporters and metabolism can also be included to delineate more complex process. For sorafenib, a more complicated PBPK model, which included phase I & II metabolism, influx and efflux transporters (Oatp and Mrp 2/3), and intestinal β-glucuronidase was developed to evaluate the disposition pathways of sorafenib, sorafenib glucuronide, and sorafenib N-oxide in mice (111). It was reported that when deconjugation of telmisartan glucuronide metabolite and enterohepatic recirculation of telmisartan was incorporated in the PBPK model structure, the pharmacokinetic profile of telmisartan in humans could be predicted more accurately (112). There was a mechanistic study performed using PBPK models to evaluate the impact of intestinal glucuronide hydrolysis on the pharmacokinetic of parent compound (113).

In most situations, inhibitors for a specific enzyme, transporter, or hydrolysis are lacking. Therefore, an important advantage of PBPK modeling is that it is an extremely useful tool to separately investigate the impact of alteration in a specific process, especially in cases of complex disposition, as that of glucuronide conjugates. These studies could be of great value to predict in vivo fate of glucuronides and potential DDIs. The major limitation of using PBPK models involving glucuronidation is that it requires the evaluation of different contributions in the disposition of glucuronides, which usually are limited in early stages of drug development.

7. Transport-Glucuronidation Classification System

The impact of transporters on disposition of glucuronides varies among compounds with different properties. Transporter knockout animal models are used frequently to study the impact of transporter deficiency on the systemic exposure of glucuronide and understand transporter-mediated glucuronide disposition. Using MRP2 as an example, after oral administration of the parent compound, the increase in AUC value of EEG in Mrp2 knockout mice compared with WT mice was reported as high as 46-fold (46), whereas the AUC value of morphine glucuronide increased slightly (~1.5-fold) in the absence of Mrp2 (114). As for BCRP, it was observed that the systemic exposure of genistein glucuronide increased by ~14-fold in Bcrp1 (-/-) mice, whereas the AUC values of the glucuronide metabolites of chrysin, resveratrol, and ethinylestradiol were similar in Bcrp1 (-/-) and WT mice (46, 51, 115).

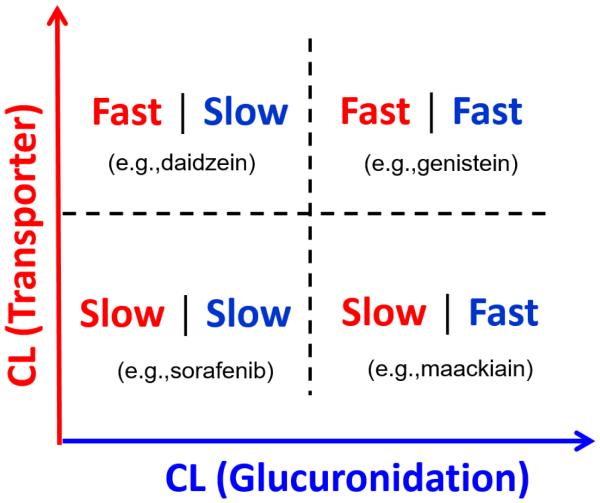

Both the formation of glucuronides by UGT enzymes and the excretion of glucuronides by transporters determine the disposition rates of glucuronides. The clearance rate by UGT enzymes can be obtained from in vitro experiments in microsomes or S9 fractions. As mentioned previously (6.1), cell lines transfected with transporters and primary hepatocytes can be used to determine the kinetics of efflux or uptake of glucuronide conjugates. Theoretically, if the kinetics of both glucuronidation and transport of a glucuronide can be assessed by in vitro tools, it would be possible to predict the impact of a single transporter on glucuronide disposition in vivo and the transporter-mediated DDIs. Based on previous studies from our lab as well as other groups, we proposed a transport-glucuronidation classification system. This system is based on in vitro data from glucuronidation and transport studies. Initially, the system will be built from simple cellular model involving only one dominant transporter. As shown in Fig.3, the horizontal axis corresponds to intrinsic glucuronidation clearance (CLint,UGT) determined in microsomes or S9 fractions while the Y axis represents the clearance of glucuronide by a transporter determined in in vitro model. In this system, compounds are divided into four classes according to their rate of being metabolized by UGT and transported by a single transporter: fast glucuronidation/fast (efflux) transport, fast glucuronidation/slow (efflux) transport, slow glucuronidation/fast (efflux) transport, and slow glucuronidation/slow (efflux) transport. Preliminary studies in mouse S9 fractions and UGT1A9-overexpressing HeLa Cells (mainly used BCRP as its efflux transporter) were performed for 10 compounds which were metabolized directly by UGTs. According to our data, the glucuronidation clearance varied considerably among compounds (from 0.009 to 124 ml/hr/mg protein), while the efflux clearance of glucuronide by BCRP varied within a smaller range (from 0.8 to 25.7 μl/min/mg protein) (unpublished data). Based on our preliminary studies, genistein can be classified as fast glucuronidation (CLint,UGT = 3.4 ml/hr/mg protein)/fast efflux transport (CLint,BCRP = 15 μl/min/mg protein), whereas sorafenib can be classified as slow glucuronidation (CLint,UGT = 0.009 ml/hr/mg protein)/slow efflux transport (CLint,BCRP = 0.8 μl/min/mg protein). Previous studies have shown that the blood levels of genistein and genistein glucuronide increased significantly in Bcrp1 (-/-) mice (47). We hypothesize that if a compound is glucuronidated fast and the resulting glucuronide is transported rapidly by a dominant transporter, the systemic exposure of this glucuronide will be very sensitive to the alteration of transporter activities. In this case, predictions based on traditional scaling from in vitro data would not be accurate, and better prediction could be achieved in a PBPK model incorporating transport process. The novel transport-glucuronidation classification system and PBPK modeling will be useful to predict the impact of BCRP on glucuronide disposition for different compounds and the potential transporter-mediated DDIs for drugs undergoing glucuronidation. Further, the simple cellular models for different transporters can be combined and a multi-dimensional classification system involving more than one transporter can be constructed to describe the disposition of glucuronide in more complex systems. If achieved, we believe the proposed classification system will be very valuable for PBPK model development and predictions of glucuronidation in vivo.

Figure 3.

Transport-Glucuronidation Classification System and the representative compounds taking BCRP as an example. Compounds are classified based on the clearance by a transporter (Y-axis) and the clearance by glucuronidation (X-axis).

8. Conclusion

The prediction of in vivo glucuronidation is very important for early stage characterization of clearance properties of drugs in humans. In this article, we discussed the problems and challenges in glucuronidation prediction based on in vitro studies. Previous efforts have been focusing on optimizing the experimental conditions of in vitro glucuronidation studies, whereas the importance of efflux / uptake transporters-mediated disposition of glucuronide was highlighted in this article.

Considering the fact that the systemic exposure of glucuronide metabolites is determined by many other factors in addition to enzyme activities, we believe that PBPK modeling incorporating transporters, enterohepatic recycling, and the hydrolysis of glucuronide conjugates provides new opportunities for improving the prediction of glucuronidation. A transport-glucuronidation classification system based on the kinetics of both glucuronidation and transport of a glucuronide was proposed as a new strategy to predict the impact of a transporter on glucuronide disposition in vivo and the transporter-mediated DDIs.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kolaand I, Landis J. Can the pharmaceutical industry reduce attrition rates? Nature reviews Drug discovery. 2004;3:711–715. doi: 10.1038/nrd1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams JA, Hyland R, Jones BC, Smith DA, Hurst S, Goosen TC, Peterkin V, Koup JR, Ball SE. Drug-drug interactions for UDP-glucuronosyltransferase substrates: a pharmacokinetic explanation for typically observed low exposure (AUCi/AUC) ratios. Drug metabolism and disposition: the biological fate of chemicals. 2004;32:1201–1208. doi: 10.1124/dmd.104.000794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mackenzie PI, Bock KW, Burchell B, Guillemette C, Ikushiro S, Iyanagi T, Miners JO, Owens IS, Nebert DW. Nomenclature update for the mammalian UDP glycosyltransferase (UGT) gene superfamily. Pharmacogenetics and genomics. 2005;15:677–685. doi: 10.1097/01.fpc.0000173483.13689.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miners JO, Mackenzie PI, Knights KM. The prediction of drug-glucuronidation parameters in humans: UDP-glucuronosyltransferase enzyme-selective substrate and inhibitor probes for reaction phenotyping and in vitro-in vivo extrapolation of drug clearance and drug-drug interaction potential. Drug metabolism reviews. 2010;42:196–208. doi: 10.3109/03602530903210716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Naritomi Y, Nakamori F, Furukawa T, Tabata K. Prediction of hepatic and intestinal glucuronidation using in vitro-in vivo extrapolation. Drug metabolism and pharmacokinetics. 2015;30:21–29. doi: 10.1016/j.dmpk.2014.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Furukawa T, Nakamori F, Tetsuka K, Naritomi Y, Moriguchi H, Yamano K, Terashita S, Teramura T. Quantitative prediction of intestinal glucuronidation of drugs in rats using in vitro metabolic clearance data. Drug metabolism and pharmacokinetics. 2012;27:171–180. doi: 10.2133/dmpk.dmpk-11-rg-088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu B, Dong D, Hu M, Zhang S. Quantitative prediction of glucuronidation in humans using the in vitro- in vivo extrapolation approach. Current topics in medicinal chemistry. 2013;13:1343–1352. doi: 10.2174/15680266113139990038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wells PG, Mackenzie PI, Chowdhury JR, Guillemette C, Gregory PA, Ishii Y, Hansen AJ, Kessler FK, Kim PM, Chowdhury NR, Ritter JK. Glucuronidation and the UDP-glucuronosyltransferases in health and disease. Drug metabolism and disposition: the biological fate of chemicals. 2004;32:281–290. doi: 10.1124/dmd.32.3.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jančová P. Phase II Drug Metabolism. Topics on Drug Metabolism. 2012 M.Š. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Itoh H, Nagano T, Takeyama M. Cisapride raises the bioavailability of paracetamol by inhibiting its glucuronidation in man. The Journal of pharmacy and pharmacology. 2001;53:1041–1045. doi: 10.1211/0022357011776298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abernethy DR, Greenblatt DJ, Ameer B, Shader RI. Probenecid impairment of acetaminophen and lorazepam clearance: direct inhibition of ether glucuronide formation. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics. 1985;234:345–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mazerska Z, Mroz A, Pawlowska M, Augustin E. The role of glucuronidation in drug resistance. Pharmacology & therapeutics. 2016;159:35–55. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2016.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iyanagi T. Molecular mechanism of phase I and phase II drug-metabolizing enzymes: implications for detoxification. International review of cytology. 2007;260:35–112. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(06)60002-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rane A, Wilkinson GR, Shand DG. Prediction of hepatic extraction ratio from in vitro measurement of intrinsic clearance. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics. 1977;200:420–424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iwatsubo T, Hirota N, Ooie T, Suzuki H, Shimada N, Chiba K, Ishizaki T, Green CE, Tyson CA, Sugiyama Y. Prediction of in vivo drug metabolism in the human liver from in vitro metabolism data. Pharmacology & therapeutics. 1997;73:147–171. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(96)00184-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ridgway D, Tuszynski JA, Tam YK. Reassessing models of hepatic extraction. Journal of biological physics. 2003;29:1–21. doi: 10.1023/A:1022531403741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pangand KS, Rowland M. Hepatic clearance of drugs. I. Theoretical considerations of a "well-stirred" model and a "parallel tube" model. Influence of hepatic blood flow, plasma and blood cell binding, and the hepatocellular enzymatic activity on hepatic drug clearance. Journal of pharmacokinetics and biopharmaceutics. 1977;5:625–653. doi: 10.1007/BF01059688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robertsand MS, Rowland M. A dispersion model of hepatic elimination: 3. Application to metabolite formation and elimination kinetics. Journal of pharmacokinetics and biopharmaceutics. 1986;14:289–308. doi: 10.1007/BF01106708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakamori F, Naritomi Y, Furutani M, Takamura F, Miura H, Murai H, Terashita S, Teramura T. Correlation of intrinsic in vitro and in vivo clearance for drugs metabolized by hepatic UDP-glucuronosyltransferases in rats. Drug metabolism and pharmacokinetics. 2011;26:465–473. doi: 10.2133/dmpk.dmpk-11-rg-018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mistryand M, Houston JB. Glucuronidation in vitro and in vivo. Comparison of intestinal and hepatic conjugation of morphine, naloxone, and buprenorphine. Drug metabolism and disposition: the biological fate of chemicals. 1987;15:710–717. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boaseand S, Miners JO. In vitro-in vivo correlations for drugs eliminated by glucuronidation: investigations with the model substrate zidovudine. British journal of clinical pharmacology. 2002;54:493–503. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2125.2002.01669.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Soars MG, Burchell B, Riley RJ. In vitro analysis of human drug glucuronidation and prediction of in vivo metabolic clearance. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics. 2002;301:382–390. doi: 10.1124/jpet.301.1.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deguchi T, Watanabe N, Kurihara A, Igeta K, Ikenaga H, Fusegawa K, Suzuki N, Murata S, Hirouchi M, Furuta Y, Iwasaki M, Okazaki O, Izumi T. Human pharmacokinetic prediction of UDP-glucuronosyltransferase substrates with an animal scale-up approach. Drug metabolism and disposition: the biological fate of chemicals. 2011;39:820–829. doi: 10.1124/dmd.110.037457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ilett KF, Ethell BT, Maggs JL, Davis TM, Batty KT, Burchell B, Binh TQ, Thu le TA, Hung NC, Pirmohamed M, Park BK, Edwards G. Glucuronidation of dihydroartemisinin in vivo and by human liver microsomes and expressed UDP-glucuronosyltransferases. Drug metabolism and disposition: the biological fate of chemicals. 2002;30:1005–1012. doi: 10.1124/dmd.30.9.1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cubitt HE, Houston JB, Galetin A. Relative importance of intestinal and hepatic glucuronidation-impact on the prediction of drug clearance. Pharmaceutical research. 2009;26:1073–1083. doi: 10.1007/s11095-008-9823-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gepts E, Camu F, Cockshott ID, Douglas EJ. Disposition of propofol administered as constant rate intravenous infusions in humans. Anesthesia and analgesia. 1987;66:1256–1263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Servin F, Desmonts JM, Haberer JP, Cockshott ID, Plummer GF, Farinotti R. Pharmacokinetics and protein binding of propofol in patients with cirrhosis. Anesthesiology. 1988;69:887–891. doi: 10.1097/00000542-198812000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hasselstromand J, Sawe J. Morphine pharmacokinetics and metabolism in humans. Enterohepatic cycling and relative contribution of metabolites to active opioid concentrations. Clinical pharmacokinetics. 1993;24:344–354. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199324040-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Milne RW, Nation RL, Somogyi AA. The disposition of morphine and its 3- and 6-glucuronide metabolites in humans and animals, and the importance of the metabolites to the pharmacological effects of morphine. Drug metabolism reviews. 1996;28:345–472. doi: 10.3109/03602539608994011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rawlins MD, Henderson DB, Hijab AR. Pharmacokinetics of paracetamol (acetaminophen) after intravenous and oral administration. European journal of clinical pharmacology. 1977;11:283–286. doi: 10.1007/BF00607678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gwilt JR, Robertson A, Mc CE. Determination of blood and other tissue concentrations of paracetamol in dog and man. The Journal of pharmacy and pharmacology. 1963;15:440–444. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1963.tb12811.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miners JO, Lillywhite KJ, Yoovathaworn K, Pongmarutai M, Birkett DJ. Characterization of paracetamol UDP-glucuronosyltransferase activity in human liver microsomes. Biochemical pharmacology. 1990;40:595–600. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(90)90561-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schulz P, Dick P, Blaschke TF, Hollister L. Discrepancies between pharmacokinetic studies of amitriptyline. Clinical pharmacokinetics. 1985;10:257–268. doi: 10.2165/00003088-198510030-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Breyer-Pfaff U, Fischer D, Winne D. Biphasic kinetics of quaternary ammonium glucuronide formation from amitriptyline and diphenhydramine in human liver microsomes. Drug metabolism and disposition: the biological fate of chemicals. 1997;25:340–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Garnett WR. Lamotrigine: pharmacokinetics. Journal of child neurology. 1997;12(Suppl 1):S10–15. doi: 10.1177/0883073897012001041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rambeckand B, Wolf P. Lamotrigine clinical pharmacokinetics. Clinical pharmacokinetics. 1993;25:433–443. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199325060-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Magdalou J, Herber R, Bidault R, Siest G. In vitro N-glucuronidation of a novel antiepileptic drug, lamotrigine, by human liver microsomes. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics. 1992;260:1166–1173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miners JO, Robson RA, Birkett DJ. Gender and oral contraceptive steroids as determinants of drug glucuronidation: effects on clofibric acid elimination. British journal of clinical pharmacology. 1984;18:240–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1984.tb02461.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Emudianughe TS, Caldwell J, Sinclair KA, Smith RL. Species differences in the metabolic conjugation of clofibric acid and clofibrate in laboratory animals and man. Drug metabolism and disposition: the biological fate of chemicals. 1983;11:97–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dragacci S, Hamar-Hansen C, Fournel-Gigleux S, Lafaurie C, Magdalou J, Siest G. Comparative study of clofibric acid and bilirubin glucuronidation in human liver microsomes. Biochemical pharmacology. 1987;36:3923–3927. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(87)90459-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Addison RS, Parker-Scott SL, Hooper WD, Eadie MJ, Dickinson RG. Effect of naproxen co-administration on valproate disposition. Biopharmaceutics & drug disposition. 2000;21:235–242. doi: 10.1002/bdd.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Soars MG, Riley RJ, Findlay KA, Coffey MJ, Burchell B. Evidence for significant differences in microsomal drug glucuronidation by canine and human liver and kidney. Drug metabolism and disposition: the biological fate of chemicals. 2001;29:121–126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dowling J, Isbister GK, Kirkpatrick CM, Naidoo D, Graudins A. Population pharmacokinetics of intravenous, intramuscular, and intranasal naloxone in human volunteers. Therapeutic drug monitoring. 2008;30:490–496. doi: 10.1097/FTD.0b013e3181816214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miners JO, Smith PA, Sorich MJ, McKinnon RA, Mackenzie PI. Predicting human drug glucuronidation parameters: application of in vitro and in silico modeling approaches. Annual review of pharmacology and toxicology. 2004;44:1–25. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.44.101802.121546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rowland A, Gaganis P, Elliot DJ, Mackenzie PI, Knights KM, Miners JO. Binding of inhibitory fatty acids is responsible for the enhancement of UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 2B7 activity by albumin: implications for in vitro-in vivo extrapolation. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics. 2007;321:137–147. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.118216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zamek-Gliszczynski MJ, Day JS, Hillgren KM, Phillips DL. Efflux transport is an important determinant of ethinylestradiol glucuronide and ethinylestradiol sulfate pharmacokinetics. Drug metabolism and disposition: the biological fate of chemicals. 2011;39:1794–1800. doi: 10.1124/dmd.111.040162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yang Z, Zhu W, Gao S, Yin T, Jiang W, Hu M. Breast cancer resistance protein (ABCG2) determines distribution of genistein phase II metabolites: reevaluation of the roles of ABCG2 in the disposition of genistein. Drug metabolism and disposition: the biological fate of chemicals. 2012;40:1883–1893. doi: 10.1124/dmd.111.043901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zamek-Gliszczynski MJ, Nezasa K, Tian X, Bridges AS, Lee K, Belinsky MG, Kruh GD, Brouwer KL. Evaluation of the role of multidrug resistance-associated protein (Mrp) 3 and Mrp4 in hepatic basolateral excretion of sulfate and glucuronide metabolites of acetaminophen, 4-methylumbelliferone, and harmol in Abcc3−/− and Abcc4−/− mice. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics. 2006;319:1485–1491. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.110106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lagas JS, Sparidans RW, Wagenaar E, Beijnen JH, Schinkel AH. Hepatic clearance of reactive glucuronide metabolites of diclofenac in the mouse is dependent on multiple ATP-binding cassette efflux transporters. Molecular pharmacology. 2010;77:687–694. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.062364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vasilyeva A, Durmus S, Li L, Wagenaar E, Hu S, Gibson AA, Panetta JC, Mani S, Sparreboom A, Baker SD, Schinkel AH. Hepatocellular Shuttling and Recirculation of Sorafenib-Glucuronide Is Dependent on Abcc2, Abcc3, and Oatp1a/1b. Cancer research. 2015;75:2729–2736. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-0280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ge S, Yin T, Xu B, Gao S, Hu M. Curcumin Affects Phase II Disposition of Resveratrol Through Inhibiting Efflux Transporters MRP2 and BCRP. Pharmaceutical research. 2016;33:590–602. doi: 10.1007/s11095-015-1812-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Coleand SP, Deeley RG. Multidrug resistance mediated by the ATP-binding cassette transporter protein MRP. BioEssays : news and reviews in molecular, cellular and developmental biology. 1998;20:931–940. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(199811)20:11<931::AID-BIES8>3.0.CO;2-J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Paulusmaand CC, Oude Elferink RP. The canalicular multispecific organic anion transporter and conjugated hyperbilirubinemia in rat and man. Journal of molecular medicine. 1997;75:420–428. doi: 10.1007/s001090050127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schaub TP, Kartenbeck J, Konig J, Vogel O, Witzgall R, Kriz W, Keppler D. Expression of the conjugate export pump encoded by the mrp2 gene in the apical membrane of kidney proximal tubules. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 1997;8:1213–1221. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V881213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Maoand Q, Unadkat JD. Role of the breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP/ABCG2) in drug transport--an update. The AAPS journal. 2015;17:65–82. doi: 10.1208/s12248-014-9668-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wu B, Jiang W, Yin T, Gao S, Hu M. A new strategy to rapidly evaluate kinetics of glucuronide efflux by breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP/ABCG2) Pharmaceutical research. 2012;29:3199–3208. doi: 10.1007/s11095-012-0817-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chu XY, Huskey SE, Braun MP, Sarkadi B, Evans DC, Evers R. Transport of ethinylestradiol glucuronide and ethinylestradiol sulfate by the multidrug resistance proteins MRP1, MRP2, and MRP3. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics. 2004;309:156–164. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.062091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jedlitschky G, Leier I, Buchholz U, Hummel-Eisenbeiss J, Burchell B, Keppler D. ATP-dependent transport of bilirubin glucuronides by the multidrug resistance protein MRP1 and its hepatocyte canalicular isoform MRP2. The Biochemical journal. 1997;327:305–310. doi: 10.1042/bj3270305. Pt 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sun H, Zhou X, Zhang X, Wu B. Decreased Expression of Multidrug Resistance-Associated Protein 4 (MRP4/ABCC4) Leads to Reduced Glucuronidation of Flavonoids in UGT1A1-Overexpressing HeLa Cells: The Role of Futile Recycling. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry. 2015;63:6001–6008. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.5b00983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chen ZS, Robey RW, Belinsky MG, Shchaveleva I, Ren XQ, Sugimoto Y, Ross DD, Bates SE, Kruh GD. Transport of methotrexate, methotrexate polyglutamates, and 17beta-estradiol 17-(beta-D-glucuronide) by ABCG2: effects of acquired mutations at R482 on methotrexate transport. Cancer research. 2003;63:4048–4054. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nakatomi K, Yoshikawa M, Oka M, Ikegami Y, Hayasaka S, Sano K, Shiozawa K, Kawabata S, Soda H, Ishikawa T, Tanabe S, Kohno S. Transport of 7-ethyl-10-hydroxycamptothecin (SN-38) by breast cancer resistance protein ABCG2 in human lung cancer cells. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2001;288:827–832. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tang L, Li Y, Chen WY, Zeng S, Dong LN, Peng XJ, Jiang W, Hu M, Liu ZQ. Breast cancer resistance protein-mediated efflux of luteolin glucuronides in HeLa cells overexpressing UDP-glucuronosyltransferase 1A9. Pharmaceutical research. 2014;31:847–860. doi: 10.1007/s11095-013-1207-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wei Y, Wu B, Jiang W, Yin T, Jia X, Basu S, Yang G, Hu M. Revolving door action of breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP) facilitates or controls the efflux of flavone glucuronides from UGT1A9-overexpressing HeLa cells. Molecular pharmaceutics. 2013;10:1736–1750. doi: 10.1021/mp300562q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Brand W, van der Wel PA, Rein MJ, Barron D, Williamson G, van Bladeren PJ, Rietjens IM. Metabolism and transport of the citrus flavonoid hesperetin in Caco-2 cell monolayers. Drug metabolism and disposition: the biological fate of chemicals. 2008;36:1794–1802. doi: 10.1124/dmd.107.019943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Patel CG, Ogasawara K, Akhlaghi F. Mycophenolic acid glucuronide is transported by multidrug resistance-associated protein 2 and this transport is not inhibited by cyclosporine, tacrolimus or sirolimus. Xenobiotica; the fate of foreign compounds in biological systems. 2013;43:229–235. doi: 10.3109/00498254.2012.713531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Matsunaga N, Wada S, Nakanishi T, Ikenaga M, Ogawa M, Tamai I. Mathematical modeling of the in vitro hepatic disposition of mycophenolic acid and its glucuronide in sandwich-cultured human hepatocytes. Molecular pharmaceutics. 2014;11:568–579. doi: 10.1021/mp400513k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kimoto E, Li R, Scialis RJ, Lai Y, Varma MV. Hepatic Disposition of Gemfibrozil and Its Major Metabolite Gemfibrozil 1-O-beta-Glucuronide. Molecular pharmaceutics. 2015;12:3943–3952. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.5b00411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tetsuka K, Gerst N, Tamura K, Masters JN. Species differences in sinusoidal and canalicular efflux transport of mycophenolic acid 7-O-glucuronide in sandwich-cultured hepatocytes. Pharmacology research & perspectives. 2014;2:e00035. doi: 10.1002/prp2.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.El-Sheikh AA, Koenderink JB, Wouterse AC, van den Broek PH, Verweij VG, Masereeuw R, Russel FG. Renal glucuronidation and multidrug resistance protein 2-/ multidrug resistance protein 4-mediated efflux of mycophenolic acid: interaction with cyclosporine and tacrolimus. Translational research : the journal of laboratory and clinical medicine. 2014;164:46–56. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2014.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zelcer N, Saeki T, Reid G, Beijnen JH, Borst P. Characterization of drug transport by the human multidrug resistance protein 3 (ABCC3) The Journal of biological chemistry. 2001;276:46400–46407. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107041200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mazur CS, Marchitti SA, Dimova M, Kenneke JF, Lumen A, Fisher J. Human and rat ABC transporter efflux of bisphenol a and bisphenol a glucuronide: interspecies comparison and implications for pharmacokinetic assessment. Toxicological sciences : an official journal of the Society of Toxicology. 2012;128:317–325. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfs167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wittgen HG, van den Heuvel JJ, van den Broek PH, Siissalo S, Groothuis GM, de Graaf IA, Koenderink JB, Russel FG. Transport of the coumarin metabolite 7-hydroxycoumarin glucuronide is mediated via multidrug resistance-associated proteins 3 and 4. Drug metabolism and disposition: the biological fate of chemicals. 2012;40:1076–1079. doi: 10.1124/dmd.111.044438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Liu W, Feng Q, Li Y, Ye L, Hu M, Liu Z. Coupling of UDP-glucuronosyltransferases and multidrug resistance-associated proteins is responsible for the intestinal disposition and poor bioavailability of emodin. Toxicology and applied pharmacology. 2012;265:316–324. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2012.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Akao T, Hanada M, Sakashita Y, Sato K, Morita M, Imanaka T. Efflux of baicalin, a flavone glucuronide of Scutellariae Radix, on Caco-2 cells through multidrug resistance-associated protein 2. The Journal of pharmacy and pharmacology. 2007;59:87–93. doi: 10.1211/jpp.59.1.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhang L, Li C, Lin G, Krajcsi P, Zuo Z. Hepatic metabolism and disposition of baicalein via the coupling of conjugation enzymes and transporters-in vitro and in vivo evidences. The AAPS journal. 2011;13:378–389. doi: 10.1208/s12248-011-9277-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhang Y, Han YH, Putluru SP, Matta MK, Kole P, Mandlekar S, Furlong MT, Liu T, Iyer RA, Marathe P, Yang Z, Lai Y, Rodrigues AD. Diclofenac and Its Acyl Glucuronide: Determination of In Vivo Exposure in Human Subjects and Characterization as Human Drug Transporter Substrates In Vitro. Drug metabolism and disposition: the biological fate of chemicals. 2016;44:320–328. doi: 10.1124/dmd.115.066944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Quan E, Wang H, Dong D, Zhang X, Wu B. Characterization of chrysin glucuronidation in UGT1A1-overexpressing HeLa cells: elucidating the transporters responsible for efflux of glucuronide. Drug metabolism and disposition: the biological fate of chemicals. 2015;43:433–443. doi: 10.1124/dmd.114.061598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Roth M, Obaidat A, Hagenbuch B. OATPs, OATs and OCTs: the organic anion and cation transporters of the SLCO and SLC22A gene superfamilies. British journal of pharmacology. 2012;165:1260–1287. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01724.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Glaeser H, Bailey DG, Dresser GK, Gregor JC, Schwarz UI, McGrath JS, Jolicoeur E, Lee W, Leake BF, Tirona RG, Kim RB. Intestinal drug transporter expression and the impact of grapefruit juice in humans. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics. 2007;81:362–370. doi: 10.1038/sj.clpt.6100056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kullak-Ublick GA, Ismair MG, Stieger B, Landmann L, Huber R, Pizzagalli F, Fattinger K, Meier PJ, Hagenbuch B. Organic anion-transporting polypeptide B (OATP-B) and its functional comparison with three other OATPs of human liver. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:525–533. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.21176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gozalpour E, Greupink R, Wortelboer HM, Bilos A, Schreurs M, Russel FG, Koenderink JB. Interaction of digitalis-like compounds with liver uptake transporters NTCP, OATP1B1, and OATP1B3. Molecular pharmaceutics. 2014;11:1844–1855. doi: 10.1021/mp400699p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Picard N, Yee SW, Woillard JB, Lebranchu Y, Le Meur Y, Giacomini KM, Marquet P. The role of organic anion-transporting polypeptides and their common genetic variants in mycophenolic acid pharmacokinetics. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics. 2010;87:100–108. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2009.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Geyer J, Doring B, Failing K, Petzinger E. Molecular cloning and functional characterization of the bovine (Bos taurus) organic anion transporting polypeptide Oatp1a2 (Slco1a2) Comparative biochemistry and physiology Part B, Biochemistry & molecular biology. 2004;137:317–329. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpc.2003.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Grosser G, Doring B, Ugele B, Geyer J, Kulling SE, Soukup ST. Transport of the soy isoflavone daidzein and its conjugative metabolites by the carriers SOAT, NTCP, OAT4, and OATP2B1. Archives of toxicology. 2015;89:2253–2263. doi: 10.1007/s00204-014-1379-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zhong K, Li X, Xie C, Zhang Y, Zhong D, Chen X. Effects of renal impairment on the pharmacokinetics of morinidazole: uptake transporter-mediated renal clearance of the conjugated metabolites. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2014;58:4153–4161. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02414-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zimmerman EI, Hu S, Roberts JL, Gibson AA, Orwick SJ, Li L, Sparreboom A, Baker SD. Contribution of OATP1B1 and OATP1B3 to the disposition of sorafenib and sorafenib-glucuronide. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research. 2013;19:1458–1466. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-3306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Oswald S, Konig J, Lutjohann D, Giessmann T, Kroemer HK, Rimmbach C, Rosskopf D, Fromm MF, Siegmund W. Disposition of ezetimibe is influenced by polymorphisms of the hepatic uptake carrier OATP1B1. Pharmacogenetics and genomics. 2008;18:559–568. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e3282fe9a2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Adachi Y, Suzuki H, Schinkel AH, Sugiyama Y. Role of breast cancer resistance protein (Bcrp1/Abcg2) in the extrusion of glucuronide and sulfate conjugates from enterocytes to intestinal lumen. Molecular pharmacology. 2005;67:923–928. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.007393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zhu W, Xu H, Wang SW, Hu M. Breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP) and sulfotransferases contribute significantly to the disposition of genistein in mouse intestine. The AAPS journal. 2010;12:525–536. doi: 10.1208/s12248-010-9209-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lickteig AJ, Fisher CD, Augustine LM, Aleksunes LM, Besselsen DG, Slitt AL, Manautou JE, Cherrington NJ. Efflux transporter expression and acetaminophen metabolite excretion are altered in rodent models of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Drug metabolism and disposition: the biological fate of chemicals. 2007;35:1970–1978. doi: 10.1124/dmd.107.015107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Jager W, Gehring E, Hagenauer B, Aust S, Senderowicz A, Thalhammer T. Biliary excretion of flavopiridol and its glucuronides in the isolated perfused rat liver: role of multidrug resistance protein 2 (Mrp2) Life sciences. 2003;73:2841–2854. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(03)00699-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sfakianos J, Coward L, Kirk M, Barnes S. Intestinal uptake and biliary excretion of the isoflavone genistein in rats. The Journal of nutrition. 1997;127:1260–1268. doi: 10.1093/jn/127.7.1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Wang SW, Chen J, Jia X, Tam VH, Hu M. Disposition of flavonoids via enteric recycling: structural effects and lack of correlations between in vitro and in situ metabolic properties. Drug metabolism and disposition: the biological fate of chemicals. 2006;34:1837–1848. doi: 10.1124/dmd.106.009910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Liuand Z, Hu M. Natural polyphenol disposition via coupled metabolic pathways. Expert opinion on drug metabolism & toxicology. 2007;3:389–406. doi: 10.1517/17425255.3.3.389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Zeng M, Sun R, Basu S, Ma Y, Ge S, Yin T, Gao S, Zhang J, Hu M. Disposition of Flavonoids via Recycling: Direct Biliary Excretion of Enterically or Extrahepatically Derived Flavonoid Glucuronides. Molecular nutrition & food research. 2016 doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201500692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Michelon H, Konig J, Durrbach A, Quteineh L, Verstuyft C, Furlan V, Ferlicot S, Letierce A, Charpentier B, Fromm MF, Becquemont L. SLCO1B1 genetic polymorphism influences mycophenolic acid tolerance in renal transplant recipients. Pharmacogenomics. 2010;11:1703–1713. doi: 10.2217/pgs.10.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Jeong EJ, Liu X, Jia X, Chen J, Hu M. Coupling of conjugating enzymes and efflux transporters: impact on bioavailability and drug interactions. Current drug metabolism. 2005;6:455–468. doi: 10.2174/138920005774330657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Jiang W, Xu B, Wu B, Yu R, Hu M. UDP-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) 1A9-overexpressing HeLa cells is an appropriate tool to delineate the kinetic interplay between breast cancer resistance protein (BRCP) and UGT and to rapidly identify the glucuronide substrates of BCRP. Drug metabolism and disposition: the biological fate of chemicals. 2012;40:336–345. doi: 10.1124/dmd.111.041467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Zhang X, Dong D, Wang H, Ma Z, Wang Y, Wu B. Stable knock-down of efflux transporters leads to reduced glucuronidation in UGT1A1-overexpressing HeLa cells: the evidence for glucuronidation-transport interplay. Molecular pharmaceutics. 2015;12:1268–1278. doi: 10.1021/mp5008019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Fahrmayr C, Konig J, Auge D, Mieth M, Fromm MF. Identification of drugs and drug metabolites as substrates of multidrug resistance protein 2 (MRP2) using triple-transfected MDCK-OATP1B1-UGT1A1-MRP2 cells. British journal of pharmacology. 2012;165:1836–1847. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01672.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Iusuf D, van de Steeg E, Schinkel AH. Hepatocyte hopping of OATP1B substrates contributes to efficient hepatic detoxification. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics. 2012;92:559–562. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2012.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Minersand JO, Mackenzie PI. Drug glucuronidation in humans. Pharmacology & therapeutics. 1991;51:347–369. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(91)90065-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Horikawa M, Kato Y, Sugiyama Y. Reduced gastrointestinal toxicity following inhibition of the biliary excretion of irinotecan and its metabolites by probenecid in rats. Pharmaceutical research. 2002;19:1345–1353. doi: 10.1023/a:1020358910490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Lengyel G, Veres Z, Tugyi R, Vereczkey L, Molnar T, Glavinas H, Krajcsi P, Jemnitz K. Modulation of sinusoidal and canalicular elimination of bilirubin-glucuronides by rifampicin and other cholestatic drugs in a sandwich culture of rat hepatocytes. Hepatology research : the official journal of the Japan Society of Hepatology. 2008;38:300–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2007.00255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Naesens M, Kuypers DR, Streit F, Armstrong VW, Oellerich M, Verbeke K, Vanrenterghem Y. Rifampin induces alterations in mycophenolic acid glucuronidation and elimination: implications for drug exposure in renal allograft recipients. Clinical pharmacology and therapeutics. 2006;80:509–521. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Matsunaga N, Suzuki K, Nakanishi T, Ogawa M, Imawaka H, Tamai I. Modeling approach for multiple transporters-mediated drug-drug interactions in sandwich-cultured human hepatocytes: effect of cyclosporin A on hepatic disposition of mycophenolic acid phenyl-glucuronide. Drug metabolism and pharmacokinetics. 2015;30:142–148. doi: 10.1016/j.dmpk.2014.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Heredi-Szabo K, Glavinas H, Kis E, Mehn D, Bathori G, Veres Z, Kobori L, von Richter O, Jemnitz K, Krajcsi P. Multidrug resistance protein 2-mediated estradiol-17beta-D-glucuronide transport potentiation: in vitro-in vivo correlation and species specificity. Drug metabolism and disposition: the biological fate of chemicals. 2009;37:794–801. doi: 10.1124/dmd.108.023895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Yangand K, Brouwer KL. Hepatocellular exposure of troglitazone metabolites in rat sandwich-cultured hepatocytes lacking Bcrp and Mrp2: interplay between formation and excretion. Drug metabolism and disposition: the biological fate of chemicals. 2014;42:1219–1226. doi: 10.1124/dmd.114.057190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Pang KS, Morris ME, Sun H. Formed and preformed metabolites: facts and comparisons. The Journal of pharmacy and pharmacology. 2008;60:1247–1275. doi: 10.1211/jpp.60.10.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Yang QJ, Fan J, Chen S, Liu L, Sun H, Pang KS. Metabolite Kinetics: The Segregated-Flow Model (SFM) for Intestinal and Whole Body PBPK Modeling To Describe Intestinal and Hepatic Glucuronidation of Morphine in Rats In Vivo. Drug metabolism and disposition: the biological fate of chemicals. 2016 doi: 10.1124/dmd.116.069542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Edginton AN, Zimmerman EI, Vasilyeva A, Baker SD, Panetta JC. Sorafenib metabolism, transport, and enterohepatic recycling: physiologically based modeling and simulation in mice. Cancer chemotherapy and pharmacology. 2016;77:1039–1052. doi: 10.1007/s00280-016-3018-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Li R, Ghosh A, Maurer TS, Kimoto E, Barton HA. Physiologically based pharmacokinetic prediction of telmisartan in human. Drug metabolism and disposition: the biological fate of chemicals. 2014;42:1646–1655. doi: 10.1124/dmd.114.058461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Wu B. Use of physiologically based pharmacokinetic models to evaluate the impact of intestinal glucuronide hydrolysis on the pharmacokinetics of aglycone. Journal of pharmaceutical sciences. 2012;101:1281–1301. doi: 10.1002/jps.22827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.van de Wetering K, Zelcer N, Kuil A, Feddema W, Hillebrand M, Vlaming ML, Schinkel AH, Beijnen JH, Borst P. Multidrug resistance proteins 2 and 3 provide alternative routes for hepatic excretion of morphine-glucuronides. Molecular pharmacology. 2007;72:387–394. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.035592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Ge S, Gao S, Yin T, Hu M. Determination of pharmacokinetics of chrysin and its conjugates in wild-type FVB and Bcrp1 knockout mice using a validated LC-MS/MS method. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry. 2015;63:2902–2910. doi: 10.1021/jf5056979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]