Through an ED visit registry created from 7 pediatric EDs, we demonstrate racial and ethnic differences in unnecessary antibiotic use for treatment of viral infections.

Abstract

BACKGROUND AND OBJECTIVES:

In the primary care setting, there are racial and ethnic differences in antibiotic prescribing for acute respiratory tract infections (ARTIs). Viral ARTIs are commonly diagnosed in the pediatric emergency department (PED), in which racial and ethnic differences in antibiotic prescribing have not been previously reported. We sought to investigate whether patient race and ethnicity was associated with differences in antibiotic prescribing for viral ARTIs in the PED.

METHODS:

This is a retrospective cohort study of encounters at 7 PEDs in 2013, in which we used electronic health data from the Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network Registry. Multivariable logistic regression was used to examine the association between patient race and ethnicity and antibiotics administered or prescribed among children discharged from the hospital with viral ARTI. Children with bacterial codiagnoses, chronic disease, or who were immunocompromised were excluded. Covariates included age, sex, insurance, triage level, provider type, emergency department type, and emergency department site.

RESULTS:

Of 39 445 PED encounters for viral ARTIs that met inclusion criteria, 2.6% (95% confidence interval [CI] 2.4%–2.8%) received antibiotics, including 4.3% of non-Hispanic (NH) white, 1.9% of NH black, 2.6% of Hispanic, and 2.9% of other NH children. In multivariable analyses, NH black (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] 0.44; CI 0.36–0.53), Hispanic (aOR 0.65; CI 0.53–0.81), and other NH (aOR 0.68; CI 0.52–0.87) children remained less likely to receive antibiotics for viral ARTIs.

CONCLUSIONS:

Compared with NH white children, NH black and Hispanic children were less likely to receive antibiotics for viral ARTIs in the PED. Future research should seek to understand why racial and ethnic differences in overprescribing exist, including parental expectations, provider perceptions of parental expectations, and implicit provider bias.

What’s Known on This Subject:

Viral acute respiratory tract infections (ARTIs) are commonly diagnosed in children. Racial and ethnic differences in the use of antibiotics for treatment of viral ARTIs have been observed in the primary care setting but have not been reported in the emergency department.

What This Study Adds:

Although overall use of antibiotics for the treatment of viral ARTIs was low, racial and ethnic differences in antibiotic prescribing were demonstrated. Compared with non-Hispanic white children, non-Hispanic black and Hispanic children were less likely to receive antibiotics for viral ARTIs.

Acute respiratory tract infections (ARTIs) are among the most common reasons for children receiving emergency department (ED) care.1,2 The majority of respiratory tract infections in children are viral and do not warrant treatment with antibiotics. Nevertheless, antibiotic misuse for viral upper respiratory tract infections has been well documented, with rates of overuse as high as 13% to 75%.3–6 Inappropriate use of antibiotics leads to an increased risk of unnecessary adverse drug effects and contributes to the development of antibiotic-resistant bacteria.7–11

A recent study revealed racial and ethnic differences in antibiotic prescribing for pediatric ARTIs in non-ED settings across a pediatric primary care network, with black children receiving fewer antibiotics than non-black children.12 Racial and ethnic differences in pediatric emergency care have been described in computed tomography (CT) utilization for minor head trauma,13 performance of laboratory and radiologic testing,14 hospital admission rates,15 and pain management in children diagnosed with appendicitis16 but have not previously been explored for antibiotic prescribing. Therefore, our goal in this study was to investigate whether patient race and ethnicity was associated with antibiotic prescribing for viral infections in the pediatric emergency department (PED). We hypothesized that non-Hispanic (NH) white children with viral ARTIs receive antibiotics at higher rates than Hispanic or NH black patients.

Methods

Study Design

We performed a retrospective cohort study by using the Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN) Registry17,18 from January 1, 2013, through December 31, 2013. This study was approved by the institutional review boards of all study sites and the data coordinating center.

Data Source and Study Population

The PECARN Registry is a deidentified electronic health registry of all encounters at 7 PEDs.17 Through automated processes, the Registry captures visit data from the sites directly from the electronic health record. The sites included are geographically diverse and are composed of 4 large tertiary care children’s hospital health systems with 4 PEDs and 3 affiliated satellite PEDs. The patient populations of the ED sites contributing to the PECARN Registry are racially and ethnically diverse, with among-site variation in the racial and ethnic composition of the patient populations (Supplemental Table 4). Sites are labeled as A through G in the results and tables sections and scrambled as 1 to 7 in the Supplemental Information to preserve confidentiality and prevent unblinding of sites.

The eligible study population included all patients ≤18 years of age who were discharged from the ED with an International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) diagnosis code for viral ARTIs (Supplemental Table 5). We excluded patient encounters with additional ICD-9 diagnosis codes for bacterial infections (Supplemental Table 5) or chronic care conditions.19 Because ICD-9 diagnosis codes for pharyngitis are nonspecific, visits with a pharyngitis code (Supplemental Table 5) were excluded if a rapid strep test result was positive for group A β-hemolytic Streptococcus.

Outcome

The primary outcome measure was oral, intravenous, or intramuscular antibiotic administration in the ED or prescription on ED discharge. Visits were categorized as “antibiotic provision” if at least 1 antibiotic administration or prescription was associated with the ED visit.

Exposure

The primary exposure was patient race and ethnicity. Consistent with other racial disparities studies,20 the race and ethnicity variable was created by collapsing race and ethnicity (which were 2 discrete variables in the PECARN Registry) into 1 race and ethnicity variable. Race and ethnicity were categorized as NH black, NH white, Hispanic, and other.

Potential confounding variables included patient demographics (eg, age, sex, insurance status, and triage acuity level) and ED visit demographics (ED site, ED type, ED provider, and provider type). Patient age was analyzed as a categorical variable (0–1, 2–4, 5–9, and 10–18 years). Insurance status was categorized as private, government (eg, Medicaid, Medicare), self-pay, or other. Triage level was categorized by using the 5-level Emergency Severity Index.21 ED type was categorized as main PED or satellite ED. Provider type of record (ie, the most senior clinician) was categorized as pediatric emergency medicine (PEM) physician (eg, board certified or board eligible in PEM), general pediatrician, general emergency medicine physician (board certified or board eligible in general emergency medicine), PEM fellow, physician assistant or nurse practitioner, or other. If ED visits had multiple provider types due to transfer of care, those visits were excluded from multivariable logistic regression modeling because provider type could not be assigned but were included in all other analyses.

Statistical Analysis

We used standard measures to describe our study population and calculate rates of antibiotic provision by race and ethnicity. We used bivariable and multivariable logistic regression to develop unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios (aORs), respectively, to measure the strength of association of race and ethnicity with antibiotic use. To provide a conservative consideration of all potentially related variables, confounding and covariables with a P value < .2 in bivariable analysis were included in our multivariable model. We adjusted for clustering by clinician by using a random effects model with a random intercept for clinician. We also explored the interaction of race and ethnicity with sites that served a higher proportion of NH white children in the multivariable model to assess whether distribution of race and ethnicity modifies the estimated differences in antibiotic use. For this analysis, sites were dichotomized as to whether >30% of the pediatric population seeking care was of NH white race and ethnicity. To evaluate the effect of clustering by patient, we also performed a sensitivity analysis including only the first eligible visit for each patient. All analyses were conducted by using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

Results

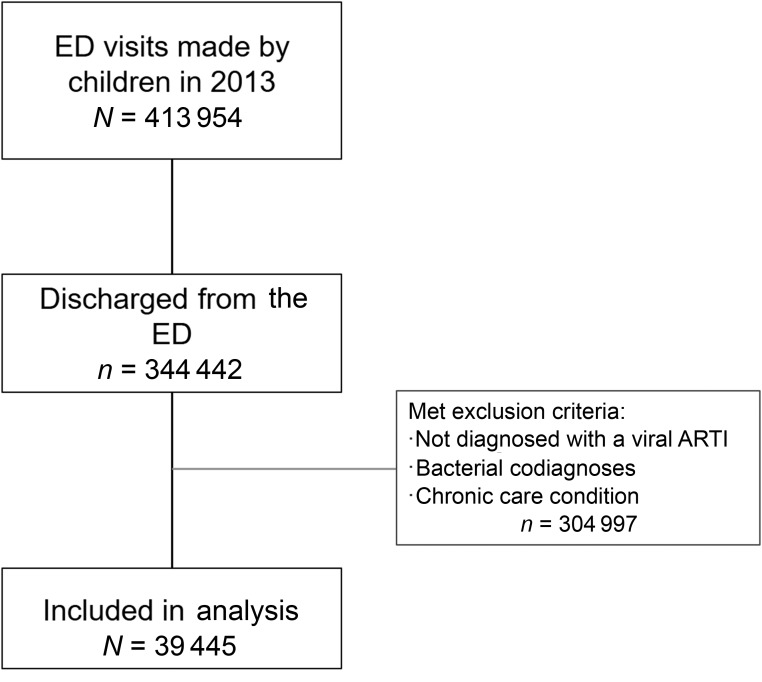

During the study period, there were 413 954 ED visits, of which there were 39 445 (9.5%) ED visits by children diagnosed with a viral ARTI who met the inclusion criteria (Fig 1). The mean age was 3.3 years, and half of the study population was NH black (Table 1). The racial and ethnic composition across sites ranged from an NH black proportion of 0.7% to 97.0% and a Hispanic proportion of 2.0% to 45.5% (Supplemental Table 5).

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of study population.

TABLE 1.

Demographics of Study Population

| Demographic | N = 39 445 |

|---|---|

| Race and ethnicity, N (%) | |

| NH white | 7526 (19.1%) |

| NH black | 19 906 (50.5%) |

| Hispanic | 8000 (20.3%) |

| Other | 3063 (7.8%) |

| Missing | 950 (2.4%) |

| Sex, N (%) | |

| Male | 21 350 (54.1%) |

| Female | 18 095 (45.9%) |

| Age group | |

| 0–1 | 20 857 (52.9%) |

| 2–4 | 10 142 (25.7%) |

| 5–9 | 5461 (13.8%) |

| 10–18 | 2985 (7.6%) |

| Insurance status, N (%) | |

| Private | 6732 (17.1%) |

| Medicaid | 30 572 (77.5%) |

| Self-pay | 1619 (4.1%) |

| Other | 343 (0.9%) |

| Missing | 179 (0.5%) |

| Triage acuity level, N (%) | |

| 5 (lowest acuity) | 9404 (23.8%) |

| 4 | 19 891 (50.4%) |

| 3 | 7708 (19.5%) |

| 2 | 1576 (4.0%) |

| 1 (highest acuity) | 10 (0.0%) |

| Missing | 856 (2.2%) |

| ED site, N (%) | |

| A | 6011 (15.2%) |

| B | 4583 (11.6%) |

| C | 6786 (17.2%) |

| D | 7650 (19.4%) |

| E | 3062 (7.8%) |

| F | 7335 (18.6%) |

| G | 4018 (10.2%) |

| ED type, N (%) | |

| Main PED | 27 782 (70.4%) |

| Satellite ED | 11 663 (29.6%) |

| Provider type, N (%) | |

| PEM attending | 13 219 (33.5%) |

| Pediatrician | 12 940 (32.8%) |

| General emergency medicine attending | 50 (0.13%) |

| Fellow | 2111 (5.4%) |

| PA/NP | 9374 (23.8%) |

| Other | 923 (2.3%) |

| Multiple attending physicians | 828 (2.1%) |

PA, physician assistant; NP, nurse practitioner.

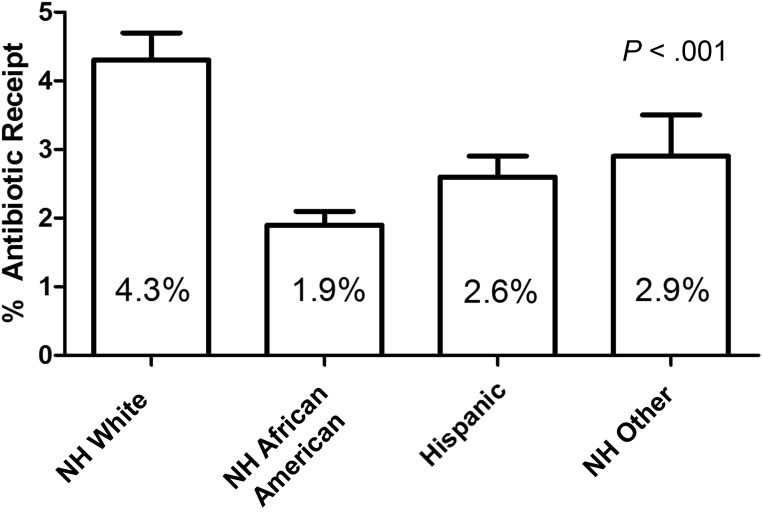

Overall, 2.6% (95% confidence interval [CI] 2.4–2.8) of children received antibiotics for viral ARTIs. This differed by race and ethnicity, with 4.3% of NH white patients receiving antibiotics compared with 1.9% of NH black, 2.6% of Hispanic, and 2.9% of other NH patients (Fig 2). Compared with NH white children, NH black (odds ratio [OR] 0.41; CI 0.35–0.49), Hispanic (OR 0.57; CI 0.47–0.69), and other NH children (OR 0.64; CI 0.50–0.82) were less likely to receive antibiotics (Table 2).

FIGURE 2.

Proportion of visits by children diagnosed with viral ARTIs and receiving antibiotics by race and ethnicity.

TABLE 2.

Bivariable and Multivariable Analysis of the Association of Race and Ethnicity with Antibiotic Provision for Viral ARTIs

| Demographic | OR (95% CI) | aORa (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Race and ethnicity | ||

| NH white | Reference | Reference |

| NH black | 0.41 (0.35–0.49)b | 0.44 (0.36–0.53)b |

| Hispanic | 0.57 (0.47–0.69)b | 0.65 (0.53–0.81)b |

| Other | 0.64 (0.50–0.82)b | 0.68 (0.52–0.87)b |

| Sex | ||

| Male | Reference | Reference |

| Female | 1.02 (0.90–1.16) | 1.03 (0.90–1.17) |

| Age group | ||

| 0–1 | Reference | Reference |

| 2–4 | 1.01 (0.86–1.18) | 1.09 (0.93–1.28) |

| 5–9 | 1.13 (0.94–1.37) | 1.19 (0.98–1.44) |

| 10–18 | 1.34 (1.07–1.67)b | 1.40 (1.11–1.77)b |

| Insurance status | ||

| Private | Reference | Reference |

| Medicaid | 0.61 (0.52–0.71)b | 0.78 (0.66–0.93)b |

| Self-pay | 0.59 (0.41–0.85)b | 0.73 (0.50–1.05) |

| Other | 0.87 (0.47–1.62) | 0.95 (0.51–1.78) |

| Triage acuity level | ||

| 5 (least acute) | Reference | Reference |

| 4 | 1.10 (0.93–1.31) | 1.09 (0.92–1.30) |

| 3 | 1.55 (1.27–1.89)b | 1.44 (1.16–1.78)b |

| 2 | 2.02 (1.49–2.72)b | 1.72 (1.25–2.37)b |

| 1 (most acute) | — | — |

| ED site | ||

| A | Reference | Reference |

| B | 0.57 (0.40–0.82)b | 0.90 (0.62–1.31) |

| C | 0.81 (0.60–1.10) | 0.86 (0.62–1.19) |

| D | 0.85 (0.63–1.14) | 1.02 (0.75–1.39) |

| E | 1.61 (1.17–2.21)b | 1.21 (0.87–1.69) |

| F | 1.21 (0.92–1.60) | 1.49 (1.11–1.98)b |

| G | 0.85 (0.61–1.20) | 0.66 (0.46–0.95)b |

| Provider type | ||

| PEM attending | Reference | Reference |

| Pediatrician | 1.04 (0.85–1.27) | 1.19 (0.95–1.48) |

| General emergency medicine attending | 0.72 (0.09–5.85) | 0.84 (0.10–6.90) |

| Fellow | 0.97 (0.68–1.37) | 1.06 (0.75–1.50) |

| PA/NP | 0.67 (0.52–0.86)b | 0.89 (0.68–1.18) |

| Other | 0.38 (0.19–0.76)b | 0.38 (0.18–0.81)b |

PA, physician assistant; NP, nurse practitioner; —, insufficient outcome.

Adjusted for sex, age, insurance status, triage acuity level, ED site, and provider type.

Signifies statistical significance with P value < .05.

In a multivariable analysis adjusting for age, insurance status, triage acuity level, ED provider type, and ED site, NH black (aOR 0.44; CI 0.36–0.53), Hispanic (aOR 0.65; CI 0.53–0.81), and other NH (aOR 0.68; CI 0.52–0.87) patients remained less likely to receive antibiotics when diagnosed with viral ARTIs in the ED (Table 2). Within-site analyses to check for consistency of the relationship between race and ethnicity and antibiotic provision across sites demonstrated generally consistent results (Table 3). When an interaction term of race and ethnicity with sites that serve a large proportion of care to NH white children was added to the multivariable model, racial and ethnic differences in antibiotic use attenuated at sites that serve a large proportion of care to NH white children (interaction P value < .01) but still persisted. A sensitivity analysis excluding 5005 (12.7%) repeat visits for patients with >1 qualifying visit yielded similar results with respect to racial and ethnic differences in antibiotic administration.

TABLE 3.

Within-Site Multivariable Models of the Effect of Race and Ethnicity on Antibiotic Provision for Viral ARTIs

| Site | aOR NH Blacka (95% CI) | aOR Hispanica (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| A | 0.65 (0.43–1.00)b | 0.94 (0.46–1.92) |

| Bc | — | — |

| C | 0.69 (0.40–1.17) | 0.79 (0.50–1.27) |

| D | 0.38 (0.20–0.72)b | 0.57 (0.28–1.13) |

| E | 0.55 (0.31–0.97)b | 0.44 (0.21–0.89)b |

| F | 0.25 (0.17–0.36)b | 0.33 (0.19–0.60)b |

| G | 1.42 (0.18–10.84) | 0.87 (0.50–1.51) |

—, insufficient outcome.

NH white = referent group; adjusted for sex, age, insurance status, triage acuity level, ED site, and provider type.

Signifies statistical significance with P value < .05.

Less than 1% of NH white patients available for statistical comparison.

Discussion

These results confirm our hypothesis that NH white children are more likely to receive unnecessary antibiotics for viral respiratory infections than their minority counterparts. Of the 2.6% of children diagnosed exclusively with viral infections and treated with antibiotics, NH white children with viral diagnoses had 1.5 to 2 times higher odds of being treated with antibiotics than Hispanic and NH black children, respectively. These differences persisted within and across sites and also among sites that treated relatively higher proportions of NH white children. These data extend previously reported racial differences in the management of ARTIs12 to the PED.

Antibiotic overuse is a public health concern.22 ARTIs are among the most common reasons that parents seek medical care for their children,23,24 and ARTIs account for ∼75% of antibiotic prescribing to children despite the majority of these infections being caused by viruses.25 Because both the frequency and duration of previous antibiotic exposure have been implicated in the spread of drug-resistant community pathogens,7 and because children receive a significant proportion of total antibiotic consumption,26 decreasing unnecessary antibiotic use in pediatric populations is a particularly important target from a public health perspective.27–29

We found lower rates of antibiotic prescribing for viral ARTIs in children than cited in previous studies, in which rates were as high as 13% to 75%.3,5 One explanation for this could be that the majority of the clinicians caring for children in our study work in pediatric settings. Pediatricians have lower rates of antibiotic use for the treatment of viral ARTIs compared with other specialties.3,30,31 Furthermore, the EDs represented in our study are all affiliated with large academic centers, and there are lower rates of antibiotic prescription for viral ARTIs in teaching hospitals.5 Additionally, it is possible that PEDs have more precise diagnosis coding than studies of claims data or other large national data sets that may be subject to incomplete data abstraction. The relatively low rates of antibiotic use for viral ARTIs observed in our study, however, do not diminish the importance of the marked racial and ethnic differences in antibiotic prescribing. At a national level, there are more than 70 000 prescriptions for antibiotics for those diagnosed with viral ARTIs in EDs annually.32

Our results are consistent with a growing body of evidence from researchers demonstrating that NH white children are more likely to receive unnecessary medical assessments and interventions in PEDs. We found that minority children received more evidence-based care with respect to management of their viral ARTIs, because antibiotics are not warranted for treatment. This phenomenon of deviations from evidence-based care for NH white children has been observed in other studies as well.13,30,33,34 On finding racial and ethnic differences in severity-adjusted hospital admission rates for children seeking emergency care, Chamberlain et al15 commented that their findings are more consistent with a practice of overadmitting white patients who were less severely ill than underadmitting black and Hispanic patients who were more severely ill. Similarly, Natale et al13 found higher rates of head CT for whites in less severely injured groups, in which CT scan use is discretionary or not recommended. There were no differences in the severely injured group. They noted that physicians more frequently cited parental anxiety or request as the most important indication influencing their decision to obtain head CTs when caring for white children than when caring for minority children.13

Although it was beyond the scope of this study to examine reasons for racial and ethnic differences in antibiotic prescribing, potential reasons may include race- and ethnicity-specific differences in parental expectations, differential parental pressures perceived by clinicians for treatment of viral infections with antibiotics, and implicit bias of clinicians. Researchers for a previous study indicated that when compared with white parents, Hispanic and black parents were more likely to believe antibiotics had a role in the treatment of colds and flu-like illnesses.35 However, Mangione-Smith et al36 demonstrated that physicians may underestimate the expectations for antibiotics among minority parents. Furthermore, in yet another study, Mangione-Smith et al37 revealed that although physicians’ perceptions of parental expectations for antimicrobial agents was the only significant predictor of prescribing antimicrobial agents for conditions of presumed viral etiology, physicians’ perceptions were not associated with actual parental expectations for antibiotics. Implicit bias of clinicians may also affect quality of delivered care. For instance, researchers for 1 study noted that in comparison with white patients, parents of minority children rated lower levels of satisfaction with respect to clinician communication.38 Researchers for another study demonstrated that as clinicians showed higher implicit preferences for white patients,black patients rated clinicians lower with respect to interpersonal treatment, communication, trust, and contextual knowledge.39 Therefore, as has been suggested in other studies that have found similar results with respect to racial and ethnic differences that generally favor white children over minority children,12,13,15 our findings may be due to a caregiver’s or a provider’s perception that “more is better,” whether the “more” is clinically indicated.15

There are some potential limitations to this study. First, these study results may not be generalizable to all PEDs or general EDs. However, this Registry included all visit data from 7 different PEDs, including academic and satellite sites with over 400 000 pediatric visits, of which over 38 000 were included in our analysis. Furthermore, racial and ethnic composition of patients included in these analyses varied by site. To address this, in addition to conducting analyses across sites, we also conducted within-site analyses that revealed consistent results. Second, visit diagnoses may have been inaccurately coded and antibiotic use may have been justified if secondary, noncoded bacterial diagnoses were targeted. Such misclassification, however, would generally bias the observed results toward the null unless coding errors were systematically different on the basis of patient race and ethnicity. Third, our study design did not allow us to explore the impact of health literacy and income level on differences in antibiotic provision.

Conclusions

We observed differential antibiotic prescribing for children presenting to the ED with viral ARTIs by patient race and ethnicity. Further investigation into the drivers of these racial and ethnic differences is critical to help inform interventions to reduce racial and ethnic differences in health care provision and achieve health equity.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Jamie Bell, Diego Campos, Jackie Cao, Sara Deakyne, Mike Dean, Rene Enriquez, Marc Gorelick, Katie Hayes, Marlena Kittick, Kendra Kocher, Venita Robinson, Beth Scheid, and Sally Jo Zuspan for their work establishing the PECARN Registry. We also wish to acknowledge the support of the PECARN Steering Committee and Subcommittees as well as Dr Elizabeth Edgerton, Director of the Division of Child, Adolescent and Family Health at the Health Resources and Services Administration, for support of this work.

Glossary

- aOR

adjusted odds ratio

- ARTI

acute respiratory tract infection

- CI

confidence interval

- CT

computed tomography

- ED

emergency department

- ICD-9

International Classification of Disease, Ninth Revision

- NH

non-Hispanic

- OR

odds ratio

- PECARN

Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network

- PED

pediatric emergency department

- PEM

pediatric emergency medicine

Footnotes

Dr Goyal conceptualized and designed the study and drafted the initial manuscript; Drs Johnson, Gerber, and Lorch helped conceptualize and design the study and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Drs Chamberlain and Alpern helped conceptualize and design the study, coordinated and supervised data collection, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Dr Casper helped conceptualize and design the study, performed and supervised data analysis, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Mr Simmons performed data analysis and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Drs Alessandrini, Bajaj, and Grundmeier coordinated and supervised data collection and reviewed and revised the manuscript; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: This work has been supported by an Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality R01 award HS020270 (Alpern); Health Resources and Services Administration, Maternal and Child Health Bureau, Emergency Medical Services for Children Network Development Demonstration Program under cooperative agreements U03MC00008, U03MC00001, U03MC00003, U03MC00006, U03MC00007, U03MC22684, and U03MC22685 (Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network); Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development K23 award HD070910 (Goyal). The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

COMPANION PAPER: A companion to this article can be found online at www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2017-2185.

References

- 1.Alpern ER, Stanley RM, Gorelick MH, et al. ; Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network . Epidemiology of a pediatric emergency medicine research network: the PECARN Core Data Project. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2006;22(10):689–699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wier LM, Yu H, Owens PL, Washington R. Overview of children in the emergency department, 2010: statistical brief #157 In: Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nyquist AC, Gonzales R, Steiner JF, Sande MA. Antibiotic prescribing for children with colds, upper respiratory tract infections, and bronchitis. JAMA. 1998;279(11):875–877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stone S, Gonzales R, Maselli J, Lowenstein SR. Antibiotic prescribing for patients with colds, upper respiratory tract infections, and bronchitis: a national study of hospital-based emergency departments. Ann Emerg Med. 2000;36(4):320–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gaur AH, Hare ME, Shorr RI. Provider and practice characteristics associated with antibiotic use in children with presumed viral respiratory tract infections. Pediatrics. 2005;115(3):635–641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hersh AL, Shapiro DJ, Pavia AT, Shah SS. Antibiotic prescribing in ambulatory pediatrics in the United States. Pediatrics. 2011;128(6):1053–1061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Costelloe C, Metcalfe C, Lovering A, Mant D, Hay AD. Effect of antibiotic prescribing in primary care on antimicrobial resistance in individual patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2010;340:c2096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dowell SF, Schwartz B, Phillips WR; The Pediatric URI Consensus Team . Appropriate use of antibiotics for URIs in children: part II. Cough, pharyngitis and the common cold. Am Fam Physician. 1998;58(6):1335–1342, 1345 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dowell SF. Principles of Judicious Use of Antimicrobial Agents: A Compendium for the Health Care Professional. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hersh AL, Jackson MA, Hicks LA; American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Infectious Diseases . Principles of judicious antibiotic prescribing for upper respiratory tract infections in pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2013;132(6):1146–1154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shehab N, Patel PR, Srinivasan A, Budnitz DS. Emergency department visits for antibiotic-associated adverse events. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47(6):735–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gerber JS, Prasad PA, Localio AR, et al. Racial differences in antibiotic prescribing by primary care pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2013;131(4):677–684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Natale JE, Joseph JG, Rogers AJ, et al. ; PECARN (Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network) . Cranial computed tomography use among children with minor blunt head trauma: association with race/ethnicity. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(8):732–737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Payne NR, Puumala SE. Racial disparities in ordering laboratory and radiology tests for pediatric patients in the emergency department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2013;29(5):598–606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chamberlain JM, Joseph JG, Patel KM, Pollack MM. Differences in severity-adjusted pediatric hospitalization rates are associated with race/ethnicity. Pediatrics. 2007;119(6). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/119/6/e1319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goyal MK, Kuppermann N, Cleary SD, Teach SJ, Chamberlain JM. Racial disparities in pain management of children with appendicitis in emergency departments. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169(11):996–1002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deakyne SLGR, Campos DA, Hayes KL, et al. Building a pediatric emergency care electronic medical registry. In: Pediatric Academic Societies Annual Meeting; April 25–28, 2015; San Diego, CA [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alpern ERAE, Casper TC, Bajaj L, et al. Benchmarks in pediatric emergency medicine performance measures derived from an multicenter electronic health record registry. In: Pediatric Academic Societies Annual Meeting; April 25–28, 2015; San Diego, CA [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feudtner C, Christakis DA, Connell FA. Pediatric deaths attributable to complex chronic conditions: a population-based study of Washington State, 1980-1997. Pediatrics. 2000;106(1 pt 2):205–209 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ulmer C, McFadden B, Nerenz DR, eds. Race, Ethnicity, and Language Data: Standardization for Health Care Quality Improvement. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gilboy N, Tanabe P, Travers D, Rosenau AM. Emergency Severity Index (ESI): A Triage Tool for Emergency Department Care, Version 4. Implementation Handbook 2012 Edition. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fleming-Dutra KE, Hersh AL, Shapiro DJ, et al. Prevalence of inappropriate antibiotic prescriptions among US ambulatory care visits, 2010-2011. JAMA. 2016;315(17):1864–1873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Benson V, Marano MA. Current estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, 1992. Vital Health Stat 10. 1994;(189):1–269 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rasooly IR, Mullins PM, Alpern ER, Pines JM. US emergency department use by children, 2001-2010. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2014;30(9):602–607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McCaig LF, Besser RE, Hughes JM. Trends in antimicrobial prescribing rates for children and adolescents. JAMA. 2002;287(23):3096–3102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hicks LA, Bartoces MG, Roberts RM, et al. US outpatient antibiotic prescribing variation according to geography, patient population, and provider specialty in 2011. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60(9):1308–1316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arnold KE, Leggiadro RJ, Breiman RF, et al. Risk factors for carriage of drug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae among children in Memphis, Tennessee. J Pediatr. 1996;128(6):757–764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reichler MR, Allphin AA, Breiman RF, et al. The spread of multiply resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae at a day care center in Ohio. J Infect Dis. 1992;166(6):1346–1353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCaig LF, Hughes JM. Trends in antimicrobial drug prescribing among office-based physicians in the United States. JAMA. 1995;273(3):214–219 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yaeger JP, Temte JL, Hanrahan LP, Martinez-Donate P. Roles of clinician, patient, and community characteristics in the management of pediatric upper respiratory tract infections. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13(6):529–536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nadeem Ahmed M, Muyot MM, Begum S, Smith P, Little C, Windemuller FJ. Antibiotic prescription pattern for viral respiratory illness in emergency room and ambulatory care settings. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2010;49(6):542–547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Donnelly JP, Baddley JW, Wang HE. Antibiotic utilization for acute respiratory tract infections in U.S. emergency departments. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58(3):1451–1457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goyal MK, Hayes KL, Mollen CJ. Racial disparities in testing for sexually transmitted infections in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2012;19(5):604–607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vanderweil SG, Tsai CL, Pelletier AJ, et al. Inappropriate use of antibiotics for acute asthma in United States emergency departments. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15(8):736–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vaz LE, Kleinman KP, Lakoma MD, et al. Prevalence of parental misconceptions about antibiotic use. Pediatrics. 2015;136(2):221–231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mangione-Smith R, Elliott MN, Stivers T, McDonald L, Heritage J, McGlynn EA. Racial/ethnic variation in parent expectations for antibiotics: implications for public health campaigns. Pediatrics. 2004;113(5). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/113/5/e385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mangione-Smith R, McGlynn EA, Elliott MN, Krogstad P, Brook RH. The relationship between perceived parental expectations and pediatrician antimicrobial prescribing behavior. Pediatrics. 1999;103(4 pt 1):711–718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Raphael JL, Guadagnolo BA, Beal AC, Giardino AP. Racial and ethnic disparities in indicators of a primary care medical home for children. Acad Pediatr. 2009;9(4):221–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Blair IV, Steiner JF, Fairclough DL, et al. Clinicians’ implicit ethnic/racial bias and perceptions of care among black and Latino patients. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11(1):43–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.