SUMMARY

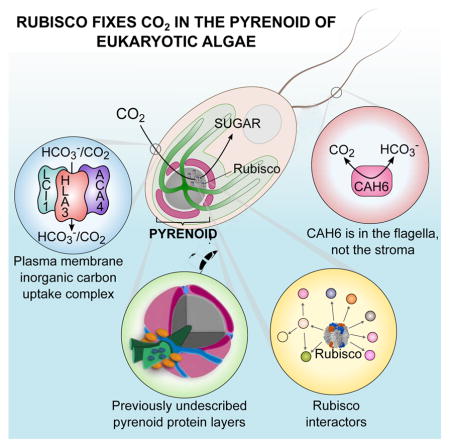

Approximately one-third of global CO2 fixation is performed by eukaryotic algae. Nearly all algae enhance their carbon assimilation by operating a CO2-concentrating mechanism (CCM) built around an organelle called the pyrenoid, whose protein composition is largely unknown. Here, we developed tools in the model alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii to determine the localizations of 135 candidate CCM proteins, and physical interactors of 38 of these proteins. Our data reveal the identity of 89 pyrenoid proteins, including Rubisco-interacting proteins, photosystem I assembly factor candidates and inorganic carbon flux components. We identify three previously un-described protein layers of the pyrenoid: a plate-like layer, a mesh layer and a punctate layer. We find that the carbonic anhydrase CAH6 is in the flagella, not in the stroma that surrounds the pyrenoid as in current models. These results provide an overview of proteins operating in the eukaryotic algal CCM, a key process that drives global carbon fixation.

Keywords: CO2-concentrating mechanism, CCM, carbon fixation, Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, photosynthesis, pyrenoid, Rubisco, high-throughput fluorescence protein tagging, affinity purification mass spectrometry

ETOC

Proteomics analyses reveal three previously unknown layers of the pyrenoid, the cellular organelle in algae responsible for one third of global CO2 fixation

INTRODUCTION

Over the past three billion years, the carbon-fixing enzyme Rubisco drew down atmospheric concentrations of CO2 to trace levels (Dismukes et al., 2001), in effect starving itself of its substrate. In parallel, the oxygenic reactions of photosynthesis have caused the appearance of abundant O2, which competes with CO2 for the active site of Rubisco and results in a loss of fixed CO2 via photorespiration (Bauwe et al., 2010). To overcome these challenges of CO2 assimilation in today’s atmosphere, many photosynthetic organisms increase CO2 levels in the vicinity of Rubisco by operating CO2 concentrating mechanisms (CCMs). Such mechanisms increase the CO2:O2 ratio at the active site of Rubisco, enhancing CO2 fixation and decreasing photorespiration. CCMs are found in nearly all marine photoautotrophs, including cyanobacteria and eukaryotic algae (Reinfelder, 2011), which together account for approximately 50% of global carbon fixation (Field et al., 1998).

In cyanobacterial CCMs, inorganic carbon in the form of bicarbonate (HCO3−) is pumped into the cytosol to a high concentration. This HCO3− is then converted into CO2 in specialized icosahedral compartments called carboxysomes, which are packed with Rubisco (Price and Badger, 1989). The components of the cyanobacterial CCMs have largely been identified, facilitated in part by the organization of the genes encoding them into operons (Price et al., 2008). Knowledge of these components has enabled the detailed characterization of the structure and assembly pathway of the beta carboxysome (Cameron et al., 2013).

Analogous to the cyanobacterial CCM, the eukaryotic green algal CCM concentrates HCO3− in a microcompartment containing tightly-packed Rubisco, called the pyrenoid. The pyrenoid is located in the chloroplast, surrounded by a starch sheath and traversed by membrane tubules that are continuous with the surrounding photosynthetic thylakoid membranes (Engel et al., 2015). Associated with the pyrenoid tubules is a carbonic anhydrase that converts HCO3− to CO2 for fixation by Rubisco (Karlsson et al., 1998). The mechanism of delivery of HCO3− to the pyrenoid thylakoids remains unknown. In contrast to the prokaryotic CCM, the protein composition of the eukaryotic algal CCM and the structural organization of the pyrenoid remain largely uncharacterized.

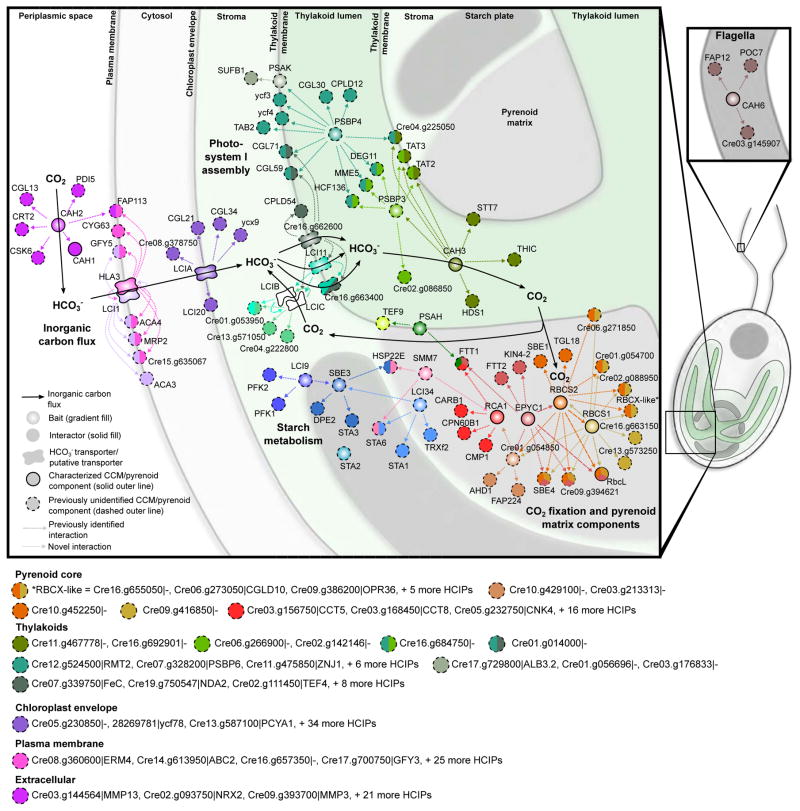

In this study, we developed a high-throughput fluorescence protein tagging and affinity purification mass spectrometry (AP-MS) pipeline for the model green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii (Figure 1A). With this pipeline, we determined the localizations of 135 candidate CCM proteins and the physical interactions of 38 core CCM components. Our microscopy data reveals an unexpected localization for the carbonic anhydrase CAH6, identifies three previously undescribed pyrenoid protein layers, and suggests that the pyrenoid shows size selectivity for stromal proteins. The AP-MS data produce a spatially resolved protein-protein interaction map of the CCM and pyrenoid, identifying novel protein complexes including a complex between inorganic carbon transporters LCI1 and HLA3, and suggesting CCM functions for multiple proteins. These results transform our basic knowledge of the eukaryotic CCM and advance the prospects of transferring this system into higher plants to improve crop production (Atkinson et al., 2016; Long et al., 2015).

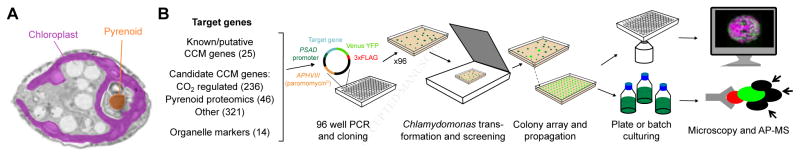

Figure 1. We Developed a High-Throughput Pipeline to Determine the Localization and Physical Interactions of Algal Proteins.

(A) A false-color transmission electron micrograph of a Chlamydomonas reinhardtii cell. The chloroplast is highlighted in magenta and the pyrenoid matrix in orange.

(B) Tagging and mass spectrometry pipeline. Target genes were amplified by PCR and Gibson assembled in frame with Venus-3xFLAG, under the constitutive PSAD promoter. Transformants were screened for fluorescence using a scanner, and arrayed to allow robotic propagation. Lines were either imaged using confocal microscopy to determine their spatial distribution or batch cultured for affinity purification-mass spectrometry (AP-MS).

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

We Developed a High-Throughput Pipeline for Systematic Localization of Proteins in Chlamydomonas

To allow the parallel cloning of hundreds of genes, we designed an expression cassette that enabled high-throughput seamless cloning via Gibson assembly (Gibson et al., 2009). Open reading frames (ORFs) were amplified by PCR from genomic DNA and cloned in frame with a C-terminal Venus YFP and a 3xFLAG epitope, driven by the strong PsaD promoter. These constructs were transformed into wild-type Chlamydomonas, where they inserted into random locations in the genome (Figure 1B). To allow dual tagging of different proteins in the same cell, we developed a second expression vector with an mCherry fluorophore and a hygromycin selection marker (Figure S1A). Potential caveats of our system include loss of the endogenous transcriptional regulation of the protein, including information encoded in the promoter, terminator and genomic locus. Additionally, the C-terminal protein tag could obscure subcellular targeting signals or disrupt functional domains.

Our Data Reveal Guidelines for Protein Localization in Chlamydomonas

Given the notorious difficulties with expressing tagged genes in Chlamydomonas (Fuhrmann et al., 1999; Neupert et al., 2009), we started with the understanding that we would only succeed in a fraction of cases, and sought to maximize the total number of proteins localized. We selected target genes from three sources: 1) genes currently thought to be involved in the CCM (See review: Wang et al., 2015); 2) candidate CCM genes, including those identified from both transcriptomic (Brueggeman et al., 2012; Fang et al., 2012) and proteomic (Mackinder et al., 2016) studies; and 3) organelle markers (Figure 1B and Table S1). We were able to determine the localizations of 146 out of the 624 target genes (23%).

We sought to leverage the large scale of this study to uncover factors that may contribute to cloning and tagging success in Chlamydomonas. We successfully cloned 298 of the 624 target genes (48%). Our cloning success rate decreased with gene size (Figure S1B). Intriguingly, cloning success was higher for genes with high expression levels (Figures S1C and D; P = 4 × 10−13, Mann Whitney U test), suggesting that intrinsic properties of a gene that influence endogenous expression may also affect PCR efficiency.

We successfully transformed and acquired protein localization data for 146 of the 298 cloned genes (49%). The two main factors correlated with our ability to obtain localization data were: 1) high endogenous gene expression level (Figures S1E and F; P = 6 × 10−14, Mann Whitney U test) and 2) absence of upstream in-frame ATGs (Figure S1G; Cross, 2016). The failure to obtain localization data for genes with in-frame uATGs is likely due to the absence of the correct translational start site in the cloned construct, resulting in a truncated protein that can be functionally impaired, structurally unstable or lacking essential organelle targeting sequence(s). These data suggest that transcript abundance is predictive for localization success and that future protein expression studies will benefit substantially from improved annotation of Chlamydomonas translation start sites.

146 Tagged Proteins Show 29 Distinct Localization Patterns

To aid in the classification of unknown proteins to subcellular regions, we tagged a series of conserved, well-characterized organelle and cellular structure proteins (Table S1). We then employed a decision tree (Figure 2A) to classify visually the localization of 135 additional proteins into 29 distinct subcellular regions, representing nearly all of the known organelles and cellular structures of Chlamydomonas (Figure 2B). The protein localizations from our study are available at https://sites.google.com/site/chlamyspatialinteractome/.

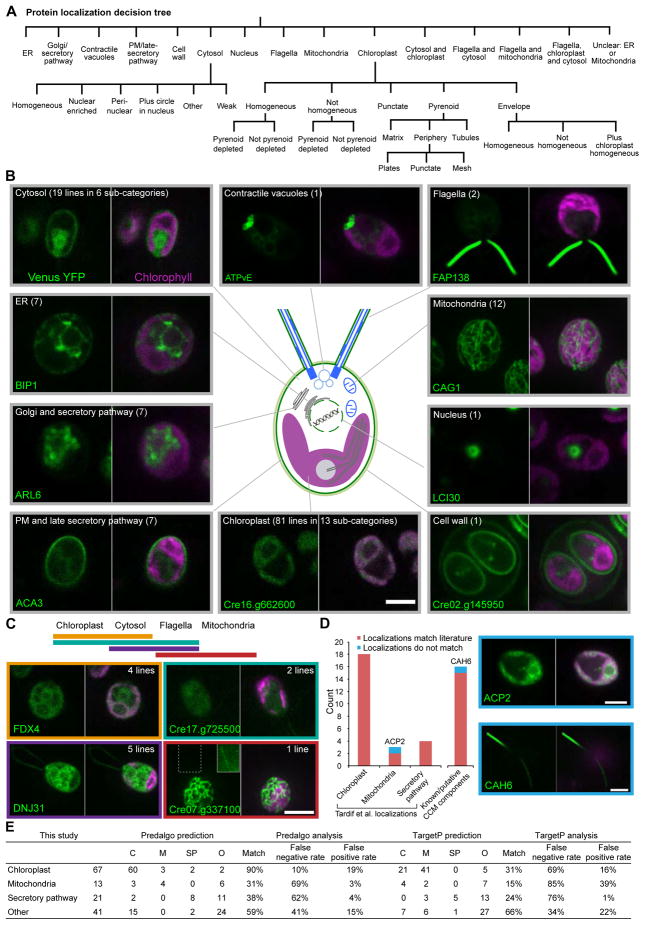

Figure 2. Tagged Proteins Localized to a Diverse Range of Cellular Locations, and Revealed That CAH6 Localizes to Flagella.

(A) A decision tree was used to assign proteins to specific subcellular locations.

(B) Representative images of proteins localized to different cellular locations. The number of different lines showing each localization pattern is in parentheses.

(C) Representative images of proteins that localized to more than one compartment. The solid outer line inset in the Cre07.g337100 image is an overexposure of the region surrounded by a dashed line, to highlight flagellar fluorescence.

(D) Comparison of our observations with published localizations. Images show the two proteins that did not match their published locations. All scale bars: 5 μm.

(E) Comparison of our observations with localizations predicted by PredAlgo and TargetP.

Interestingly, 12 proteins were not confined to one organelle but were seen in multiple compartments (Figure 2C and Table S2). If these multiple localizations are not artefacts of our expression system, they may represent proteins that function in multiple compartments or are involved in inter-organelle signalling. Additionally, we observed diverse cytosolic localizations, with subtle differences between localization patterns (Figure S2A).

Localization Assignments Agree with Previous Studies for 39/41 Proteins

To evaluate the accuracy of our method, we compared our results with published localizations of individual proteins. Our data shared 25 proteins with the validated “training” set of chloroplast, mitochondria and secretory pathway proteins from Tardif et al. (2012). Nearly all (24/25) matched our localization data, with the only exception being ACP2 (Cre13.g577100). Whereas we saw ACP2 in the chloroplast (Figure 2D), Tardif et al. (2012) saw ACP2 in isolated mitochondria. However, previous studies have either failed to detect ACP2 in mitochondria (Atteia et al., 2009), or saw it in approximately equal abundances in isolated chloroplasts and mitochondria (Terashima et al., 2010). Overall, the ambiguity in the published data leave open the possibility that our ACP2 localization data may in fact be correct. We further compared our data with previously published localizations of CCM components, and found that 15 of 16 localizations matched. The strong overlap with previously known localizations indicates that our dataset is of high quality (>95% accurate) and that C-terminal tagging of Chlamydomonas proteins results in minimal localization artefacts.

CAH6 Localizes to the Flagella

Carbonic anhydrases, which catalyse the reversible reaction of HCO3− to CO2, play a critical role in CCMs (Badger, 2003). Our successful localization of nine Chlamydomonas carbonic anhydrases shows that they are found in a diverse range of cellular locations (Figure S2B). In all current models of the CCM (Moroney et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2015), the carbonic anhydrase CAH6 is in the chloroplast stroma, where it has been proposed to convert CO2 to HCO3−.

Surprisingly, in our study, CAH6 localized to the flagella in two independent transformation lines (Figure 2D and S2B), and produced no detectable signal in the chloroplast. To exclude the possibility that our observation is due to an artefact (e.g. due to the C-terminal Venus tag), we analysed the localization of CAH6 in existing proteomic datasets. CAH6 is present in the flagellar proteome (Pazour et al., 2005) and has been shown to be an abundant intraflagellar transport (IFT) cargo (Engel et al., 2012), providing independent validation of CAH6 localization to the flagella. Additionally, CAH6 is absent from both the chloroplast proteome (Terashima et al., 2010) and the mitochondrial proteome (Atteia et al., 2009), further suggesting that levels in the chloroplast are low or non-existent.

Previous evidence for CAH6 in the stroma came from immunogold labeling experiments, in which Mitra et al. (2004) found a 4.7 fold enrichment of gold particles associated with chloroplast starch relative to control pre-immune serum. This could be an artefact due to cross-reactivity of the immunized serum with another epitope. Alternatively, CAH6 may be an abundant flagellar protein, but present at very low levels in the chloroplast.

The apparent absence of carbonic anhydrase in the stroma may be a requirement of the Chlamydomonas CCM. A stromal carbonic anhydrase could risk short-circuiting the CCM by promoting the release of CO2 from HCO3− in areas that are not in close proximity to Rubisco. In fact, it has been shown that the expression of carbonic anhydrase in the cyanobacterial cytosol, the likely functional equivalent of the chloroplast stroma, results in the disruption of the cyanobacterial CCM (Price and Badger, 1989).

Instead of directly participating in the CCM, CAH6 could be involved in inorganic carbon sensing. Chlamydomonas was recently shown to chemotax towards HCO3− (Choi et al., 2016), and carbonic anhydrases have been previously implicated in inorganic carbon sensing (Hu et al., 2010). Localization of sensing machinery to the flagella, which are found at the leading edge of swimming cells, could facilitate chemotaxis.

PredAlgo is the Best Protein Localization Predictor for Chlamydomonas

The excellent agreement of our localization data with previous studies provided an opportunity to test the accuracy of the two main localization prediction algorithms used for Chlamydomonas proteins, PredAlgo (Tardif et al., 2012) and TargetP (Emanuelsson et al., 2000). For proteins that we observed in the chloroplast, PredAlgo predicted a chloroplast localization for 90% of them, whereas TargetP only predicted a chloroplast localization for 31% (Figure 2E). For mitochondrial proteins, the accuracy dropped to 31% for PredAlgo and 15% for TargetP. For secretory pathway proteins, the accuracy was 38% for PredAlgo and 24% for TargetP. These results highlight that PredAlgo is the best localization predictor for Chlamydomonas proteins, but its accuracy drops off significantly when proteins localize to compartments other than the chloroplast.

We Assigned 82 Proteins to 13 Sub-Chloroplast Locations

Approximately 56% (82/146) of our proteins localized to the chloroplast. We assigned these 82 proteins to 13 sub-chloroplast locations (Table S1; Figures 2A and 3A). Chloroplast envelope proteins showed three subcategories of localization: 1) envelope homogeneous (signal observed evenly throughout the chloroplast envelope); 2) envelope non-homogenous and; 3) envelope plus chloroplast homogenous (signal observed throughout the chloroplast in addition to the envelope). LCIA (Low CO2 Inducible A) and LCI20 both showed some homogeneous chloroplast signal in addition to a clear envelope signal, suggesting the possibility that these proteins are functional in both the chloroplast envelope and thylakoid membranes.

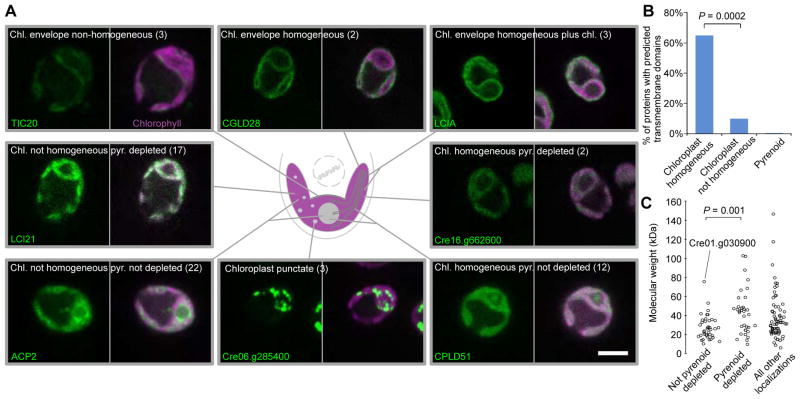

Figure 3. Chloroplast Proteins Show 13 different Localization Patterns.

(A) Representative images of proteins localized to different chloroplast regions. The number of proteins showing each pattern is in parentheses. Scale bar: 5 μm.

(B) The percentage of proteins with predicted transmembrane domains is shown for different localization patterns. Bracket shows a significant difference using Fisher’s exact test.

(C) Predicted molecular weight of proteins is shown as a function of pyrenoid signal intensity. Cre01.g030900 that has a pyrenoid signal and is above the 50 kDa cut-off is labeled. Bracket shows significant difference using a Mann-Whitney U test.

Three proteins produced similar patterns of punctate dots throughout the chloroplast (Figure S3A): a protein with predicted 50S ribosome-binding GTPase activity (Cre12.g524950), histone-like protein 1 (HLP1; Cre06.g285400) (Karcher et al., 2009), and the fatty acid biosynthesis enzyme acetyl-CoA biotin carboxyl carrier (BCC2; Cre01.g037850). The similarity of the localization patterns of these proteins suggests that chloroplast translation, chloroplast DNA and fatty acid synthesis may be co-localized in the chloroplast.

We found that proteins with specific patterns of localization were often enriched in certain physical properties. As expected, all eight chloroplast envelope proteins contained one or more transmembrane domains (Table S1). Interestingly, proteins showing homogeneous chloroplast localization (Figure 3B) were enriched in transmembrane domains, found in 9/14 homogeneous proteins vs 4/39 for chloroplast non-homogenous proteins (P = 0.0002, Fisher’s exact test). This observation suggests that proteins with homogeneous localization are most likely thylakoid membrane-associated.

The Pyrenoid Appears to Show Selectivity to Stromal Contents

Because the pyrenoid is a non-membrane-bound organelle, its protein composition cannot be regulated by a membrane translocation step. We therefore sought to understand whether pyrenoid proteins are enriched for any specific physicochemical properties. We classified chloroplast localized proteins into two groups: 1) pyrenoid depleted, where the signal from the pyrenoid was weaker than the surrounding chloroplast and 2) not pyrenoid depleted, where the signal from the pyrenoid was comparable to or brighter than the surrounding chloroplast. Interestingly, the two groups showed different protein molecular weight distributions (P = 0.001, Mann-Whitney U test). The 39 proteins that are not pyrenoid depleted are almost all smaller than ~50 kDa (Figure 3C; the value of ~50 kDa excludes the Venus YFP region, therefore the effective molecular weight is ~78 kDa), suggesting that the pyrenoid may exclude larger proteins.

We Identified Multiple New Pyrenoid Components

Electron microscopy-based techniques have shown that the Chlamydomonas pyrenoid contains a dense matrix of Rubisco surrounded by a starch sheath and traversed by membrane tubules formed from merged thylakoids (Figure 4A; Engel et al., 2015). Currently, seven proteins have been unambiguously localized to three different regions of the pyrenoid: the pyrenoid matrix, periphery, and tubules. The pyrenoid matrix contains the Rubisco holoenzyme (RBCS/RbcL); its chaperone Rubisco activase (RCA1); essential pyrenoid component 1 (EPYC1), a Rubisco linker protein important for Rubisco packaging in the pyrenoid (Mackinder et al., 2016); and a protein of unknown function (Cre06.g259100; Kobayashi et al., 2016). Under very low CO2 conditions, the LCIB/LCIC complex, whose role is still uncertain (Jin et al., 2016), is known to form puncta around the pyrenoid periphery (Yamano et al., 2010). Recently, a Ca2+-binding protein, CAS, has been shown to specifically localize to the pyrenoid tubules at low CO2 (Wang et al., 2016). Here, we identify seven additional pyrenoid-localized components and three previously un-described sub-pyrenoid localization patterns (Figure 4B–D).

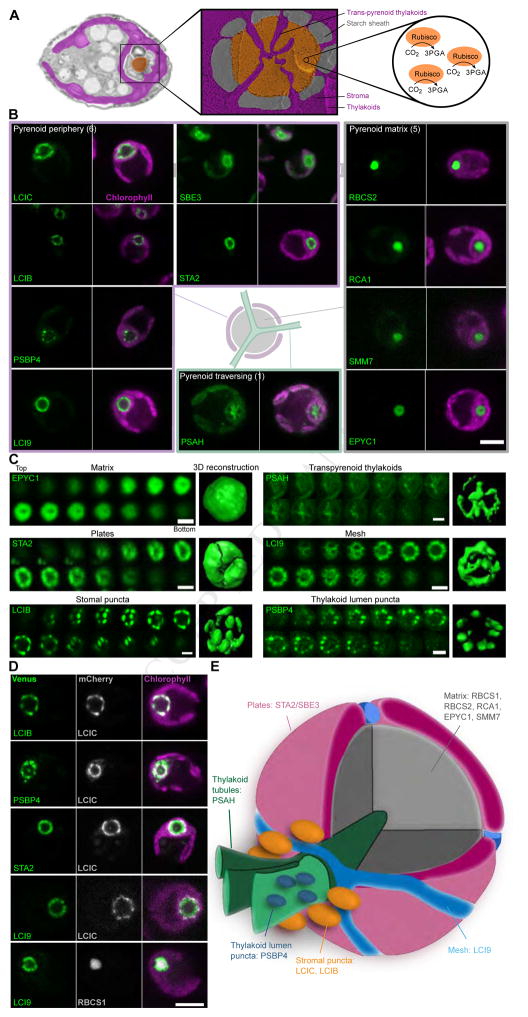

Figure 4. Pyrenoid Proteins Show at Least Six Distinct Localization Patterns and Reveal Three New Protein Layers.

(A) A false-color transmission electron micrograph and deep-etched freeze-fractured image of the pyrenoid highlight the pyrenoid tubules, starch sheath and pyrenoid matrix where the principal carbon fixing enzyme, Rubisco, is located. Images courtesy of Moritz Meyer, Ursula Goodenough and Robyn Roth.

(B) Proteins showing various localization patterns within the pyrenoid are illustrated. Scale bar: 5 μm.

(C) Confocal sections distinguish different localization patterns within the pyrenoid. Each end panel is a space-filling reconstruction. Scale bars: 2 μm.

(D) Dual tagging refined the spatial distribution of proteins in the pyrenoid. Scale bar: 5 μm.

(E) A proposed pyrenoid model highlighting the distinct spatial protein-containing regions.

The Pyrenoid Has at Least Four Distinct Outer Protein Layers

Our data suggest that the pyrenoid is surrounded by at least four distinct outer protein layers: 1) LCIB and LCIC localize to puncta around the periphery; 2) PSBP4 (photosystem II subunit P4) localizes to a different set of puncta; 3) STA2 (starch synthase 2) and SBE3 (starch branching enzyme 3) localize to plate-like structures; and 4) LCI9 localizes to a mesh-like structure (Figure 4C–E).

LCIB, LCIC and PSBP4 showed punctate outer pyrenoid patterns, whereas SBE3, STA2 and LCI9 showed a more homogeneous distribution around the pyrenoid periphery (Figure 4B). LCIB and LCIC were co-localized (Figure 4D), supporting the previous finding that they are part of the same complex in the stroma (Yamano et al., 2010).

PSBP4-Venus did not co-localize with LCIC-mCherry (Figure 4D), indicating that PSBP4 is in a different structure or complex. PPD1, the Arabidopsis homolog of PSBP4, has been shown to be in the thylakoid lumen (Liu et al., 2012). Therefore, the PSBP4 puncta likely represent proteins located in the thylakoid lumen. Consistent with this possibility, we also see a small amount of PSBP4-Venus signal within the pyrenoid, and this signal forms a network-like pattern reminiscent of pyrenoid tubules.

Our data suggest that both STA2 and SBE3 localize to the starch sheath. Co-localization indicated that STA2 was localized within the perimeter described by LCIC (Figure 4D). STA2 formed a clearly defined plate-like pattern around the pyrenoid core (Figure 4C). SBE3 also displayed this plate pattern, but was generally more diffuse than STA2 (Figure 4B).

LCI9 was tightly apposed to the pyrenoid matrix and, like STA2, also localized within the perimeter described by LCIC (Figure 4D). However, analysis of Z-sections showed that unlike STA2 and SBE3, LCI9 formed a mesh structure around the pyrenoid (Figure 4C). Intriguingly, the complementary localizations of STA2 and LCI9 suggest that LCI9 may be part of a protein layer that fills the gaps between the starch plates.

A Putative Methyltransferase Localizes to the Pyrenoid Matrix

We discovered that SMM7 (Cre03.g151650), a putative methyltransferase, localized to the pyrenoid matrix. This is intriguing because another putative methyltransferase, CIA6 (Cre10.g437829), was found to be required for pyrenoid assembly (Ma et al., 2011), although its localization was not determined. Unlike CIA6, SMM7 is strongly transcriptionally upregulated under low CO2 conditions (Brueggeman et al., 2012; Fang et al., 2012). Identification of the protein targets of CIA6 and SMM7 will likely provide critical insights into pyrenoid biogenesis and regulation.

Pyrenoid Tubules are Enriched in PSAH, a Component of Photosystem I

Traversing the pyrenoid are pyrenoid tubules, which are thought to deliver CO2 at a high concentration to the matrix (Wang et al., 2015). Previous work using immunogold labeling and photosystem (PS) I and PSII activity assays suggested that the pyrenoid tubules from several different algal lineages contain active PSI components and are depleted in PSII components (McKay and Gibbs, 1991). In contrast to these findings, we found that PSII components (PSBP3, PSBQ, PSBR) showed similar pyrenoid localization patterns to those of PSI (PSAG, PSAK and FDX1), cytochrome b6f (CYC6) and ATP synthase (ATPC) components (Figure S3B).

Strikingly, we found that unlike other PSI components, the PSI protein PSAH was enriched within the pyrenoid tubules (Figure 4B). PSAH is a 130 amino-acid protein with a single transmembrane helix that in land plants binds to the core PSI at the site where light harvesting complex II (LHCII) docks in state transitions (Ben-Shem et al., 2003; Lunde et al., 2000). The enrichment of PSAH in the pyrenoid tubules could indicate an additional, pyrenoid-related, role for this protein in algae. Together, our localization data for pyrenoid components allow us to propose a model for the spatial organization of the pyrenoid (Figure 4E).

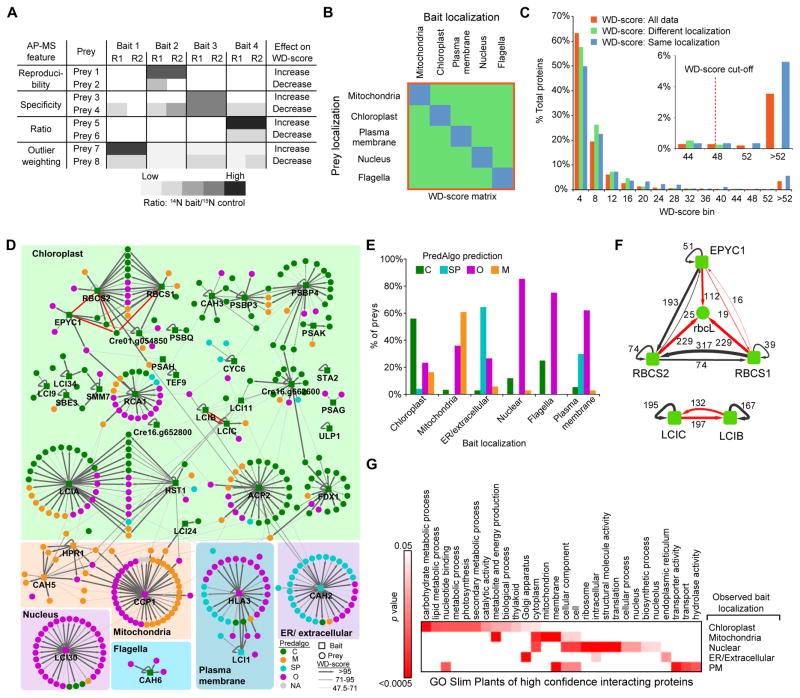

We Generated a Spatially Defined Protein-Protein Interaction Network of the CCM

To understand the interconnectivity of the protein components of the CCM, we developed a large-scale affinity purification mass spectrometry (AP-MS) approach. We chose 38 candidates for AP-MS, focusing on proteins previously implicated in the CCM and on those we found in the pyrenoid (Table S3). We affinity purified fusion proteins using their 3xFLAG tag.

To aid in filtering out nonspecific bait-prey interactions from true interactions, we used 15N labeling. We affinity purified baits and associated proteins from lines grown in 14N media, and, before mass spectrometry, we mixed each sample with affinity-purified Venus-3xFLAG and associated proteins from lines grown in 15N media. We quantified our confidence in each protein-prey interaction with a modified WD-score (Behrends et al., 2010), which incorporates the reproducibility, specificity and abundance of each interaction (Figure 5A; see STAR Methods).

Figure 5. The AP-MS Data are of High Quality.

(A) Illustration of the influence of different AP-MS features (reproducibility, specificity, ratio and outlier weighting) on the WD-score. R1 and R2 represent replica 1 and 2.

(B) To determine a WD-score cut-off value, a bait-prey matrix of WD-scores was formed containing only baits and preys whose localizations were determined in this study. The WD-scores from this matrix were then used to generate (C).

(C) A histogram of WD-scores for “All data,” “Different localization,” “Same localization.” A conservative WD-score cut-off was chosen as the point where all data fell above the highest “Different localization” WD-score. Proteins with a WD-score greater than the cut-off are classified as high confidence interacting proteins (HCIPs).

(D) Protein-protein interaction network of baits and HCIPs. Bait proteins are grouped according to their localization pattern as determined by confocal microscopy. Baits and preys are colored based on their predicted localization by PredAlgo. Previously known interactions are indicated by red arrows.

(E) Comparison of prey PredAlgo predictions with bait localization. C, chloroplast; SP, secretory pathway; O, Other; M, mitochondria.

(F) Confirmation of known interactions from the literature (red arrows). Values are WD-scores.

(G) Significantly enriched gene ontology (GO) terms for interactors of baits localized to different cellular structures.

To identify high confidence interactions, we assumed that interactions between baits and preys localized to different organelles in our study are nonspecific, and thus the distribution of their WD-scores approximates the distribution of WD-scores for false positive interactions. We took the highest WD-score value of 47.5 in this subset and used it as a cut-off. Approximately 3.8% of the interactions had WD-scores above this value, giving 513 interactions involving 398 proteins (Figure 5B and C). These proteins were considered high-confidence interacting proteins (HCIPs). This method is more stringent than previous methods in which a simulated dataset was used to determine a cut-off, resulting in approximately 5% of data being determined as HCIPs (Behrends et al., 2010; Sowa et al., 2009). One inherent limitation of AP-MS is that it cannot distinguish between direct and indirect interactions, for example this can result in large protein complexes being affinity purified even though a bait protein only directly interacts with one member of the complex.

We Used Multiple Approaches to Validate the Network

HCIPs of baits were enriched for proteins with the same PredAlgo predicted localizations (Figure 5D and E). HCIPs recapitulated previously known physical interactions of Rubisco subunits, EPYC1, LCIB and LCIC (Figure 5F). HCIPs of baits from a specific compartment (i.e. chloroplast) are significantly enriched in Gene Ontology function and localization terms related to that compartment (Figure 5G). Finally, as expected from tight transcriptional control of subunit stoichiometry in most complexes (Jansen et al., 2002), most HCIPs were transcriptionally co-regulated with their baits in response to high CO2 (Figure S4).

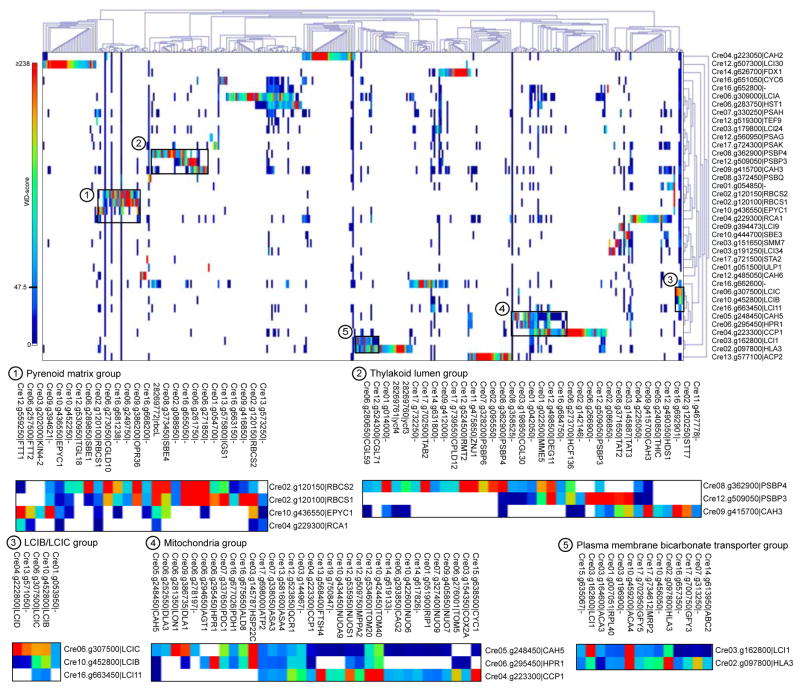

We Identified Many Novel Rubisco Interacting Proteins

To identify novel protein complexes and new members of known complexes, we performed hierarchical clustering on HCIPs (Figure 6; see Figure S5 for all bait-prey interactions with a WD-score ≥1). The baits RBCS1 and RBCS2 clustered together and shared 15 HCIPs, four of which were also HCIPs of EPYC1. RBCS1- and RBCS2-associated proteins were enriched in uncharacterized proteins. Several of these interactors have homologs in other green algae but lack any conserved domains (Cre01.g054700, Cre01.g054850, Cre02.g088950, Cre16.g655050). We found that Cre16.g655050 contains a predicted N-terminal RbcX fold, which is found in a class of Rubisco chaperones, and the rest of the protein is predicted to be disordered (Figure S6). A BLAST analysis using Cre16.g655050 as the query showed that its full sequence is conserved in the closely related species Volvox carteri and Gonium pectorale. The N-terminal RbcX-like region is conserved in several more evolutionarily distant Chlorophytes such as Micromonas pusilla (Table S4). Whether Cre16.g655050 is a chaperone for Rubisco or performs an alternative function is unknown.

Figure 6. The AP-MS Data Reveals Previously Undescribed Physical Interactions, Including That Inorganic Carbon Transporters LCI1 and HLA3 Form a Physical Complex.

Hierarchical clustering of all 38 baits with 398 HCIP preys. Specific groups of interest are boxed and highlighted below. Clustering of all baits and preys with interaction WD-scores ≥ 1 is provided in Figure S5.

Carbohydrate binding domains were found in three Rubisco interactors, including the two starch branching enzymes, SBE1 and SBE4, the latter of which also interacts with EPYC1. Given the concave shape of the pyrenoid-surrounding starch sheaths, there may be variation in starch synthesis and/or breakdown occurring between the two faces. One way to target a subset of starch metabolic enzymes to the inner concave face would be through a binding interaction with pyrenoid matrix proteins. The functional roles of the different SBE isoforms in Chlamydomonas have yet to be determined.

Interestingly, RBCS1 and RBCS2 interact with an ATP binding cassette (ABC) family transporter (Cre06.g271850). The specific role of this protein may help us elucidate transmembrane transport processes occurring across pyrenoid tubules.

EPYC1 Interacts with a Kinase and Two 14-3-3 Proteins

The putative Rubisco linker protein EPYC1 is phosphorylated at low CO2 (Turkina et al., 2006). Interestingly, we see that EPYC1 associates with a predicted serine/threonine protein kinase (KIN4-2; Cre03.g202000). Understanding the role of this kinase may shed light on post-translational modifications associated with pyrenoid biogenesis and/or function.

EPYC1 interacts with two 14-3-3 proteins FTT1 and FTT2. 14-3-3 proteins are known to bind phosphorylated proteins; hence the interaction of 14-3-3 proteins with EPYC1 could potentially be regulated by the phosphorylation state of EPYC1. 14-3-3 proteins can influence the stability, function, interactions and localization of their targets (Chevalier et al., 2009). It is therefore possible that these 14-3-3 proteins are regulating an interaction between EPYC1 and Rubisco, possibly by changing the availability of protein-binding domains.

CAH3 Interacts with TAT proteins and STT7

The carbonic anhydrase CAH3 is essential for the CCM (Karlsson et al., 1998) and is thought to convert HCO3− to CO2 in the thylakoid membranes that traverse the pyrenoid, supplying the pyrenoid with a high concentration of CO2. In our study, CAH3 associated with the TAT2 and TAT3 proteins of the twin-arginine translocation (Tat) pathway (Figure 6 and 7; Table S5), which delivers substrate proteins to the thylakoid lumen. This observation is consistent with work showing that CAH3 contains a predicted Tat signal peptide (Benlloch et al., 2015) and with previous biochemical studies suggesting that CAH3 localizes to the thylakoid lumen (Karlsson et al., 1998).

Figure 7. Combining Localization, Protein-Protein Interaction and Protein Function Data Reveals a Spatially Defined Interactome of the Chlamydomonas CCM.

A spatially defined protein-protein interaction model of the CCM. Baits have a gradient fill, prey have a solid fill. Each bait has a unique color. Prey are colored according to their bait, with proteins that interact with multiple baits depicted as pies with each slice colored according to one of their interacting baits. Interactors are connected to their bait by a dashed line representing the direction of interaction. Baits are arranged based on their localization observed in this study. Interactors with predicted transmembrane domains are placed on membranes. Prey of membrane localized baits lacking transmembrane domains are arranged according to their PredAlgo localization prediction. Solid black arrows indicate inorganic flux through the cell. For clarity, a selection of interactors are not included in the map but are highlighted below. All interaction data with corresponding WD-scores can be found in Table S5.

At low CO2, CAH3 is phosphorylated, and this phosphorylation correlates with increased CA activity and localization to the pyrenoid (Blanco-Rivero et al., 2012). Here, we find that CAH3 has a strong interaction (WD-score = 209) with the kinase STT7 (Figure 6). The role of STT7 in LHCII phosphorylation and state transitions is well documented (Depège et al., 2003). However, it is unlikely that STT7 is directly phosphorylating CAH3, because the kinase domain of STT7 has been shown to be on the stromal side (Lemeille et al., 2009) and CAH3 is thought to be localized in the lumen (Karlsson et al., 1998). A direct interaction between STT7 and CAH3 may be occurring via the N-terminus of STT7, which is thought to be luminal via a single membrane traversing domain (Lemeille et al., 2009).

PSBP4 is in a Complex with PSI Assembly Factors

PSBP4 is a PsbP domain (PPD)-containing protein whose Arabidopsis homolog is essential for photosystem I assembly and function (Liu et al., 2012). In our data, PSBP4 interacted with four proteins associated with PSI assembly: ycf3, ycf4, CGL71 and TAB2 (Heinnickel et al., 2016; Rochaix et al., 2004), suggesting that PSBP4 and these factors form a PSI assembly complex. PSBP4 also interacts with three uncharacterized conserved green lineage proteins (CGL30, CGL59 and CPLD12) and nine other proteins of unknown function (Figure 7), indicating that these proteins may have roles in PSI assembly and function. Notably, PSBP4’s localization suggests that PSI assembly occurs at the pyrenoid periphery.

The LCIB/LCIC Complex Interacts with Two Bestrophin-Like Proteins

Our data confirm that LCIB and LCIC, known stromal soluble proteins, are in a tight complex (Yamano et al., 2010). The lcib mutant has an “air-dier” phenotype: it exhibits WT growth in either very low CO2 (0.01% CO2 v/v) or high CO2 (3% v/v), but dies in air levels of CO2 (0.04%) (Wang and Spalding, 2006). The functional role of the LCIB/C complex is still unknown. This complex is hypothesized to either form a CO2 leakage barrier at the pyrenoid periphery or to act as a vectorial CO2 to HCO3− conversion module to recapture CO2 that escapes from the pyrenoid (Wang et al., 2015). A role in the conversion of CO2 to HCO3− is likely, as several homologs of LCIB were recently shown to be functional β-carbonic anhydrases. However, recombinant LCIB/C had no carbonic anhydrase function (Jin et al., 2016), suggesting that the complex may be tightly regulated or may require additional factors for proper function.

Both LCIB and LCIC interact with LCI11 (Cre16.g663450), and LCIC also interacts with Cre16.g662600 (Figure 6 and 7). Both LCI11 and Cre16.g662600 are putative bestrophins, which typically transport chloride but have been shown to be permeable to HCO3− (Qu and Hartzell, 2008). Furthermore, both proteins are upregulated at low CO2 levels (Table S1 and Figure S4). LCI11 and Cre16.g662600 directly interact, and both also interact with another bestrophin-like protein, Cre16.g663400.

LCI9 Interacts with PFK1, PFK2 and SBE3 to Form a Carbohydrate Metabolism Module

As described above, LCI9 forms a mesh structure, likely in the gaps between starch plates. LCI9 contains two CBM20 (carbohydrate binding module 20) domains and is predicted to function as a glucan 1,4-α-glucosidase. Glucan 1,4-α-glucosidases hydrolyze glucosidic bonds, releasing glucose monomers from glucan chains. Therefore, LCI9 most likely plays a role in starch breakdown at the pyrenoidal starch plate junctions. AP-MS analysis shows that the strongest HCIPs of LCI9 are PFK1 and PFK2 (phosphofructokinases 1 and 2). PFK is a key regulator of glycolysis and is important for maintaining cellular ATP levels (Johnson and Alric, 2013). The exact metabolic role of an LCI9, PFK1 and PFK2 assemblage is still unclear. LCI9 also associates with SBE3, which in turn associates with STA3 and DPE2 (disproportionating enzyme 2), a putative α-1,4-glucanotransferase. Because SBE3 and its HCIPs are involved in starch synthesis and modification, enzymes catalysing starch breakdown and starch synthesis are potentially in close proximity, allowing tight regulation of starch structure. It should be noted that a caveat of performing AP-MS on proteins containing CBMs is that proteins could co-precipitate due to binding a common carbohydrate substrate, not due to direct protein-protein interactions.

Bicarbonate Transporters LCI1 and HLA3 Form a Complex with a P-type ATPase

HLA3 (high light activated 3) and LCI1 have both been implicated in HCO3− uptake at the plasma membrane (Ohnishi et al., 2010; Yamano et al., 2015). HLA3 is an ABC transporter, and its absence under low CO2 conditions results in a reduced uptake of inorganic carbon by Chlamydomonas cells (Yamano et al., 2015). HLA3 expressed in Xenopus oocytes showed moderate uptake of HCO3− (Atkinson et al., 2016). LCI1 lacks any conserved functional or structural domains and contains four predicted transmembrane regions. Knock-down of LCI1 protein resulted in a small reduction in inorganic carbon uptake (Ohnishi et al., 2010); however, the function of LCI1 has not been demonstrated in a heterologous system.

Unexpectedly, we found that HLA3 and LCI1 are found together in a complex. The two proteins showed a reciprocal, strong interaction, each having WD scores >125. In addition, they appear to be in a complex with ACA4 (Autoinhibited Ca2+-ATPase 4; Cre10.g459200), a P-type ATPase/cation transporter. Alignment of ACA4 with functionally characterized P-type ATPases shows that it is a member of the group IIIA family of P-type ATPases (Figure S7). Group IIIA members are known H+-exporting ATPases (Thever and Saier, 2009). ACA4 may be aiding HCO3− uptake either by maintaining a H+ gradient that HLA3 and/or LCI1 is using to drive HCO3− uptake, or by generating localized cytosolic alkaline regions similar to those that form near anion exchanger I during HCO3− uptake (Johnson and Casey, 2011). A localized alkaline region could decrease HCO3− to CO2 conversion and hence diffusion out of the cell.

The regulation of inorganic carbon transport is critical for the efficiency of the CCM. Recent work has shown that Ca2+ signalling is key for proper regulation of the CCM, with the Ca2+-binding protein CAS1 transcriptionally regulating HLA3 and other components (Wang et al., 2016). One HCIP of HLA3 is an EF-hand-containing Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase (Cre13.g571700), which could potentially regulate HLA3 post-translationally. Additionally, HLA3 physically interacts with an adenylate/guanylate cyclase (CYG63: Cre05.g236650). Adenylate and guanylate cyclases are known to play a role in sensing inorganic carbon across a broad range of taxa (Tresguerres et al., 2010). Thus, Cre13.g571700 and Cre05.g236650 may represent another mode of CCM regulation, possibly by sensing inorganic carbon availability at the plasma membrane.

Perspective

By developing an efficient fluorescent protein-tagging and AP-MS pipeline in Chlamydomonas, we have generated a spatially defined network of the Chlamydomonas CCM. This large-scale approach gives a comprehensive view of the CCM by revealing missing components, by redefining the localization of others, and by identifying specific protein-protein interactions. Our work also provides insight into the function and regulation of these known and newly discovered CCM proteins, and represents a valuable resource for their further characterization.

Our observation that the pyrenoid matrix appears to exclude proteins larger than ~78 kDa may be related to the liquid-like nature of the matrix (Freeman Rosenzweig et al., 2017). Interestingly, another liquid-like non-membrane organelle, the C. elegans P granule, shows size exclusion of fluorescently labelled dextrans 70 kDa and larger (Updike et al., 2011). This behavior may result from surface tension generated by the proteins that produce the liquid phase (Bergeron-Sandoval et al., 2016).

Our results suggest changes to the existing model of inorganic carbon flux to the pyrenoid (Figure 7). The apparent absence of carbonic anhydrase in the chloroplast stroma aligns the Chlamydomonas CCM model more with the cyanobacterial model, in which the absence of carbonic anhydrase in the cytosol is critical for inorganic carbon accumulation in the form of HCO3− (Price and Badger, 1989; Price et al., 2008). The localization of the carbonic anhydrase CAH6 in flagella suggests potential roles in inorganic carbon sensing. Furthermore, the discovery that HLA3 and LCI1 form a complex and the identification of potential regulatory factors of this complex will aid in the characterization and ultimately the reconstitution of this key plasma membrane bicarbonate transport pathway.

Due to a rapidly rising global population and a finite agricultural land area, novel approaches are essential to maintain food security. One potential approach for improving yields is the transfer of a CCM into higher plants to increase CO2 fixation rates (Long et al., 2015). Recent work has found that nearly all algal CCM proteins localize correctly in higher plants with no changes to their protein sequence, suggesting that the transfer of algal components could be relatively straightforward (Atkinson et al., 2016). However, engineering efforts were constrained by our limited knowledge of the components of the algal CCM. The work we present here provides a detailed blueprint of the algal CCM, revealing dozens of new targets for transfer into crop plants to improve carbon fixation, and enhancing our basic molecular understanding of a fundamental cellular process that drives global biogeochemical cycles.

STAR Methods

CONTACT FOR REAGENT AND RESOURCE SHARING

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Martin C. Jonikas (mjonikas@princeton.edu).

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Strains and Culturing

The background Chlamydomonas reinhardtii strain for all experiments was wild-type (WT) cMJ030 (CC-4533). WT cells were maintained on 1.5% Tris-acetate-phosphate (TAP) agar with revised Hutner’s trace elements (Kropat et al., 2011) at 22°C in low light (~10 μmol photons m−2 s−1). Lines harboring Venus-3xFLAG-tagged genes in the pLM005 plasmid were maintained in the same conditions with solid media supplemented with 20 μg mL−1 paromomycin. For lines also harbouring the pLM006 plasmid, the media was further supplemented with 25 μg mL−1 hygromycin. During liquid growth for imaging and affinity purification mass spectrometry, antibiotic concentrations were used at 1/10th these concentrations.

METHOD DETAILS

Plasmid Construct and Cloning

For the tagging and AP-MS pipeline, we used the pLM005 plasmid, and for dual-tagging experiments, we used the pLM006 plasmid (Mackinder et al., 2016). Open reading frames were PCR amplified (Phusion Hotstart II polymerase, ThermoFisher Scientific) from genomic DNA, gel purified (MinElute Gel Extraction Kit, Qiagen) and cloned in-frame with either a C-terminal Venus-3xFLAG (pLM005) or an mCherry-6xHIS (pLM006) tag by Gibson assembly. Primers were designed to amplify target genes from their predicted start codon up to, but not including, the stop codon. To allow efficient assembly into HpaI-cut pLM005 or pLM006, primers contained the following adapters: Forward primers (5′-3′), GCTACTCACAACAAGCCCAGTT and reverse primers (5′-3′), GAGCCACCCAGATCTCCGTT. To increase our success with larger genes, we split some of these into multiple fragments that were reassembled following PCR amplification. However, due to a multiplicative effect, the cloning efficiency dropped off rapidly: only a 20% efficiency for two fragments (14/69) and 8% for three fragments (6/74). All junctions were sequence verified by Sanger sequencing and constructs were linearized by either EcoRV or DraI prior to transformation into WT Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. For each transformation, 14.5 ng kbp−1 of cut plasmid was mixed with 250 μL of 2 × 108 cells mL−1 at 16 °C in a 0.4 cm gap electroporation cuvette and transformed immediately into WT strains by electroporation using a Gene Pulser II (Bio-Rad) set to 800V and 25uF. Cells transformed with plasmids containing the pLM005 backbone were selected on TAP paromomycin (20 μg mL−1) plates and kept in low light (5–10 μmol photons m−2 s−1) until screening for fluorescence. To generate dual-tag lines, lines expressing Venus tagged proteins were sequentially transformed with target genes inserted in the pLM006-mCherry-6xHIS plasmid and selected on TAP paromomycin (20 μg mL−1) and hygromycin (25 μg mL−1) plates. Transformation plates were directly screened for fluorescence using a Typhoon Trio fluorescence scanner (GE Healthcare) with the following excitation and emission settings: Venus, 532 excitation with 555/20 emission; mCherry, 532 excitation with 610/30 emission; and chlorophyll autofluorescence, 633 excitation with 670/30 emission. For each construct, three fluorescent colonies were isolated and maintained in 96 arrays using a Singer Rotor propagation robot. A detailed, step by step protocol for cloning and AP-MS is available at: https://sites.google.com/site/chlamyspatialinteractome/.

Microscopy

For microscopy of Venus-tagged lines, colonies were transferred from agar to Tris-phosphate (TP) liquid medium (Kropat et al., 2011) in a 96-well microtiter plate and grown with gentle agitation in air at 150 μmol photons m−2 s−1 light intensity (LumiBar LED lights, LumiGrow). After ~2 days of growth, 15 μL of cells were pipetted onto a 96-well optical bottom plate (Brooks Automation Inc.) and a 120 μL of 1% TP low-melting-point agarose at ~34°C was overlaid to minimize cell movement. Lines grown for detailed Z-stack analysis and dual-tagged lines containing proteins with both Venus and mCherry tags were grown in 80 mL of TP, bubbled with 0.01% CO2 (with 21% O2, balanced with N2) for ~12 hours at 150 μmol photons m−2 s−1 light intensity. 10–15 μL of cells were pipetted on poly-L-lysine coated plates (Ibidi) and overlaid with 1% TP agarose as above. All imaging was performed using a spinning-disk confocal microscope (custom modified Leica DMI6000) with Slidebook software (3i). The following excitation and emission settings were used: Venus, 514 excitation with 543/22 emission; mCherry, 561 excitation with 590/20 emission; and chlorophyll, 561 excitation with 685/40 emission. All confocal microscopy images were analyzed using Fiji (Schindelin et al., 2012). 3D pyrenoid reconstructions were generated from Z-sections using Imaris software (Bitplane).

Affinity Purification

Cell lines expressing Venus-3xFLAG-tagged proteins were grown in 50 mL of TAP media at 100 μmol photons m−2 s−1 light intensity until they reached a cell density of ~2–4 × 106 cells mL−1. Cells were then pelleted at 1000 g for 4 minutes, resuspended in TP medium and transferred to 800 mL of TP medium. They were then bubbled with air with constant stirring and 150 μmol photons m−2 s−1 light intensity to a density of ~2–4 × 106 cells mL−1. All liquid media contained 2 μg mL−1 paromomycin. In parallel, control strains expressing only the Venus-3xFLAG tag were grown under identical conditions except that, during liquid growth, 14NH4Cl, the sole nitrogen source, was replaced with 15NH4Cl. This ensured 15N growth for at least eight generations.

Cells from Venus-3xFLAG-tagged protein lines and control lines were separately harvested and affinity purified as follows: Cells were spun out (2,000 g, 4 minutes, 4°C), washed in 40 mL of ice cold 1xIP buffer (200 mM sorbitol, 50 mM HEPES, 50 mM KOAc, 2 mM Mg(OAc)2.4H2O, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM NaF, 0.3 mM Na3VO4 and 1 cOmplete EDTA-free protease inhibitor (Sigma-Aldrich)/50 mL), centrifuged then resuspended in a 1:1 (v/w) ratio of ice-cold 2xIP buffer to cell pellet. This cell slurry was then added drop wise to liquid nitrogen to form small Chlamydomonas pellets approximately 5 mm in diameter. These were stored at -70°C until needed.

Cells were lysed by grinding 1g of Chlamydomonas pellets by mortar and pestle at liquid nitrogen temperatures. The ground cells were defrosted and dounced 20 times on ice with a Kontes Duall #21 homogeniser (Kimble). Membranes were solubilised by incrementally adding an equal volume of ice-cold 1xIP buffer plus 2% digitonin (final concentration is 1%; Sigma-Aldrich), followed by a 40 minute incubation with nutation at 4°C. The lysate was then clarified by spinning for 30 minutes at ~13,000 g in a table-top centrifuge at 4°C. The supernatant was then transferred to 225 μL of protein G Dynabeads (ThermoFisher Scientific) that had been incubated with anti-FLAG M2 antibody (Sigma-Aldrich) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, except 1xIP buffer was used for the wash steps. The Dynabead-cell lysate was incubated for 1.5 hours on a rotating platform at 4°C, then the supernatant removed. The Dynabeads were washed 4 times with 1xIP buffer plus 0.1% digitonin followed by a 30 minute competitive elution with 50 μL of 1xIP buffer plus 0.25% digitonin and 2 μg/μL 3xFLAG peptide (Sigma-Aldrich). After elution samples were diluted 1:1 with 2X SDS-PAGE buffer (BioRad) containing 50 mM β-mercaptoethanol and heat denatured for 10 minutes at 70°C. Tagged protein and control denatured elutions were then mixed 1:1 (16μL:16μL), and 28 μL of sample was partially purified by electrophoresing on a 10% Tris-glycine gel (Criterion TGX gel; BioRad) until the protein moved 1.8 to 2 cm (~40 minutes at 50V). Gel slices were then fixed in 1 mL of 10% acetic acid, 50% methanol, 40% deionised water for 1 hour, with a change of the fixing solution after 15 minutes, 30 minutes and 1 hour. Gel slices were soaked twice in 1mL of deionized water for 2 minutes, then stored in 1% acetic acid at 4°C until processing for mass spectrometry.

Mass Spectrometry

Limited gel slices representing 3xFLAG AP eluates were diced into 1×1mM squares and then incubated in 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate for ~15 minutes. After pH neutralization, the diced gel slices were reduced with 5 mM DTT for 30 minutes at 55°C. The reducing buffer was removed and samples were alkylated with 10 mM propionamide at 10 mM for 30 minutes at room temperature. Gel samples were washed with multiple rounds of 1:1 acetonitrile:50mM ammonium bicarbonate until the gels were free of all dye. 10 uL of 125 nanogram trypsin/lysC (Promega) was added to each gel band and gels were allowed to swell for 10 minutes, followed by the addition of 25 to 35uL 50 mM ammonium bicarbonate. The gels were digested overnight at 37°C. Peptide extraction was performed in duplic ate, and the peptide pools dried in a speed vac until readied for LCMS/MS. Each peptide pool was reconstituted in 12.5 uL 0.1% formic acid, 2% acetonitrile, 97.9% water and loaded onto a NanoAcquity UPLC (Waters). The mobile phases were A: 0.585% acetic acid, 99.415% water and B: 0.585% acetic acid, 10% water, 89.415% acetonitrile. The analytical column was a picochip (New Objective) packed with 3 μM C18 reversed phase material approximately 10.5cm in length. The flow rate was 600 nL/min during the injection phase and 450 nL/min during the analytical phase. The mass spectrometer was a orbitrap Elite, operated in a data-dependant acquisition (DDA) schema in which the fifteen most intense multiply charged precursor ions were selected for fragmentation in the ion trap. The precursor mass settings were a resolution of 120,000 and an ion target value of 750,000, max fill time 120 usec. The MS/MS settings were 50,000 ions and a maximum fill time of 25 μsec.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Mass Spectrometry Data Analysis

Peptide identification

MS/MS data were analyzed using an initial screening by Preview for validation of data quality, followed by Byonic v2.6.49 (Protein Metrics Inc.) for peptide identification and protein inference against version 5.5 of the Chlamydomonas reinhardtii translated genome. In a typical analysis, each data file was searched in two parallel Byonic analyses: one for the unlabeled peptides, and one treating the incorporation of 15N isotopic labels as a fixed modification. In both cases, these data were restricted to 12 ppm mass tolerances for precursors, with 0.4 Da fragment mass tolerances assuming up to two missed cleavages and allowing for only fully tryptic peptides. These data were validated at a 1% false discovery rate using typical reverse-decoy techniques as described previously (Elias and Gygi, 2007). The combined identified peptide spectral matches and assigned proteins were then exported for further analysis using custom tools developed in MatLab (MathWorks) to provide visualization and statistical characterization.

Background to CompPASS analysis

To identify bona fide interactions, we used an 14N/15N labeling strategy. Bait-Venus-3xFLAG fusion proteins were grown in 14N media in parallel to 15N grown controls expressing only Venus-3xFLAG. 3xFLAG affinity purification was performed for target and control lines in parallel, proteins were eluted by 3xFLAG competition, and then target and control elutions were mixed prior to SDS-PAGE purification and MS. In theory, this approach should control for non-specific proteins interacting with the resin, 3xFLAG peptide, Venus and tubes and it should also control for MS variation between runs, resulting in only large ratios for specific interactors. However, analysis of the complete data set showed that using only 14N/15N ratios was insufficient to identify real interactors from false positives. This is generally due to the spurious nature of some preys, and in several cases the ratios diverged from 1 across all baits for some preys. Therefore, to analyze our 14N/15N labeled dataset, we decided to adapt the CompPASS method (Sowa et al., 2009), an approach previously developed to analyze AP-MS studies of this size using unlabeled proteins.

Identification of protein carry-over between MS runs

Carry-over of proteins from previous MS runs is a common source of contamination, and increases with protein abundance and hydrophobicity (Morris et al., 2014). To reduce carry-over contamination, column wash steps and MS blanks were frequently included, and placed between samples that were previously identified to be prone to carry-over. In addition, an in silico filtering step was included to remove carry-over contamination prior to CompPASS analysis. Data was sorted by MS run order and half-life-like patterns of decreasing raw values were scanned for. To confirm contamination was due to carry-over and not true interactions, half-life-like patterns between MS replicas ran in a different order were compared. Raw values for carry-over contamination that showed the same patterns between replicas were set to zero.

Generating WD-scores

The CompPASS method uses spectral counts and devises a score (WD-score) based on the specificity of the prey, spectral count number and reproducibility. Instead of using spectral counts, we used 14N/15N ratios. Using 14N/15N ratios helps clean out abundant common contaminants. Based on the CompPASS method, we generated WD-scores for each bait-prey interaction. First, we determined the 14N/15N ratios for the bait-prey interaction for each replica. If a protein had no spectral counts in one of the 14N or 15N, the spectral count was set to 1 to generate a ratio. If it was not detected in both the 14N and 15N, its 14N/15N ratio value was therefore 1. The ratios for each replica were then averaged to populate a stats table of 38 baits and 3251 preys.

| Stats table | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Bait 1 | Bait 2 | Bait 3 | Bait k | ||

| Prey 1 | X1,1 | X2,1 | X3,1 | Xk,1 | X̄1 |

| Prey 2 | X1,2 | X2,2 | X3,2 | Xk,2 | X̄2 |

| Prey 3 | X1,3 | X2,3 | X3,3 | Xk,3 | X̄3 |

| Prey m | X1,m | X2,m | X3,m | Xk,m | X̄m |

Xi,j is the average 14N/15N ratio from two replicas (q and r) for prey j from bait i (Eq. S1).

| (Eq. S1) |

m is the total number of unique prey proteins identified (3251).

k is the total number of unique baits (38).

We plugged the above values into the WD-score equation (Behrends et al., 2010), which is defined as follows (Eqs. S2–S4):

| (Eq. S2) |

| (Eq. S3) |

| (Eq. S4) |

| (Eq. S5) |

| (Eq. S6) |

| (Eq. S7) |

The WD-score has 3 main components taking into account the uniqueness, the reproducibility and the 14N/15N ratio. is a “uniqueness” measure that up-weights unique interactors and down-weights promiscuous interactors. It counts the number of baits that a given prey was detected in. Therefore, the less often the prey is seen across the baits, the larger the value. k is constant for all preys, in our case it is 38. Therefore, if a prey is unique to one bait, this term will equal 38 (38/1), whereas if is a prey is seen interacting with all baits this value would be 1 (38/38). In addition to the uniqueness measurement is a weighting term, ωj (Eq. S3). This term is only applied if the standard deviation is greater than the mean for a prey across all baits. It was introduced in Behrends et al. (2010) to offset the low uniqueness value for true interactors that are seen in many baits.

p is a reproducibility measure that upweights preys that are seen in both replicas. We modified the p weighting (Eqs. S5–S7) to only come into effect if the ratio averages were ≤10.2 fold of each other. We decided to add a “closeness” value of replica ratios, because spurious and general contaminant preys would be frequently detected in both replicas but would have a large 14N/15N ratio difference between replicas, whereas in true interactors 14N/15N ratios between replicas are generally very similar. To determine a cut-off, we looked at all preys that were only detected in one bait and which were also replicated in both MS runs (this gave 173 high-confidence true interactions). We then took the largest fold change between the replica 14N/15N ratios where more than 1 spectral count was used to determine the ratio.

Xi,j is the 14N/15N ratio. In Sowa et al. (2009), this is the average of total spectral counts for the replicas. In our case the Xi,j is the average of the 14N/15N of both replicas. By using the 14N/15N ratio we in effect have performed an initial clean up of the data, with background contaminants (seen in both the 14N bait and 15N control) down-weighted.

If the protein was not detected in either replica it was assigned a WD-score of 0.

Determining the WD-score threshold

Due to the empirical nature of the WD-score, a cut-off must be determined. Sowa et al. (2009) generated a random dataset and used a cut-off value above which 5% of the random dataset fell. Interestingly, this also corresponded to ~5% of the real dataset, which they recommend as a suitable approximation for the threshold. Due to potential pitfalls in the generation of a random dataset, we decided to use an alternate approach to determine the WD-score cut-off. We made a new stats table that included all baits (38) and just preys (83) that we had obtained localization data for. We then made the assumption that interactions between baits and preys in spatially different regions (at the organelle level) were non-specific. We took the highest WD-score value in this new stats table and used it as the WD-score cut-off, which, in our case was 47.516. Approximately 3.78% of the data lies above this value, giving 513 interactions involving 398 proteins. A WD-score >47.516 was thus considered a high confidence interacting protein (HCIP).

Data visualization

WD-score analysis and bait-prey matrix assembly were performed in Microsoft Excel. Hierarchical clustering was done using Multi Experiment Viewer (http://mev.tm4.org/). Network visualization was done in Cytoscape (http://www.cytoscape.org/).

Comparison of Localization Data with PredAlgo and TargetP

To allow the direct comparison of PredAlgo and TargetP predictions to our localization data, we classified our data as follows: Chloroplast (C) includes “Chloroplast,” “Cytosol and chloroplast,” and “Flagella, chloroplast and cytosol.” Mitochondria (M) includes “Mitochondria,” “Flagella and mitochondria,” and “Unclear ER or mitochondria.” Secretory pathway (SP) includes “Plasma membrane and late-secretory pathway,” “ER,” “Unclear ER or mitochondria,” “Golgi and secretory pathway,” “Cell wall,” and “Contractile vacuoles.” Other (O) includes “Cytosol,” “Flagella,” “Flagella and cytosol,” “Flagella and mitochondria,” “Flagella, chloroplast and cytosol,” and “Nucleus.” The data used for analysis excluded proteins used in the PredAlgo training set (Tardif et al., 2012).

Gene Expression Values and Presence of Upstream ATGs

Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million mapped reads (FPKM) values were downloaded from Phytozome (https://phytozome.jgi.doe.gov/phytomine/begin.do). For analysis of cloning and localization success relative to transcript abundance, FPKM values for “photo.HighLight MidLog” from the GeneAtlas experiment group were used. These experiments were performed at ambient CO2 levels (~400 ppm), a CO2 concentration reflective of our experimental conditions. For an approximation of CCM induction, log2 FPKM changes were calculated by dividing FPKM values from photo.HighLight MidLog and hetero.Ammonia MidLog experiments of the GeneAtlas experiment group.

An analysis of genes for upstream ATGs (uATGs) was recently performed on version 5.5 of the Chlamydomonas genome (Cross, 2016). Comparison of our localization data to the presence of uATGs showed that localization success was 63% (89/141) in the absence of upstream ATGs (uATGs), relative to only 30% (17/57; Figure S1G) when uATGs were found in-frame to the annotated start site in the mRNA (Cross, 2016).

Interestingly, localization success only rose to 40% for both cloned genes that contained an out-of-frame uATG (12/30) and cloned genes that contained an uATG followed by an in-frame stop codon (26/65). This suggests that in some cases out-of-frame uATGs may be the correct translation initiation sites due to unannotated splicing events. Our data is in general agreement with the analysis by Cross (2016), which proposed that ~10% of current transcript models would result in incorrect translation initiation and incorrect encoded peptides.

P-Type ATPase Tree Assembly

Protein sequences of diverse P-type ATPases (Thever and Saier, 2009) were downloaded from the National Centre for Biotechnology Information (NCBI; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). NCBI sequences were combined with six P-type ATPases found in Chlamydomonas for a total of 259 sequences. Sequence alignment was performed using ClustalW and a phylogenetic tree created using FastTree2 (http://www.microbesonline.org/fasttree/).

GO Term Analysis

HCIPs of baits that localized to either the chloroplast, mitochondria, nucleus, ER/extracellular or PM were analyzed for GO-term enrichment using the Cytoscape plugin, BINGO (https://www.psb.ugent.be/cbd/papers/BiNGO/Home.html). Preys also included some baits that were detected as HCIPs of other baits. The GO-term, “Generation of precursor metabolites and energy” was shortened to “metabolite and energy production” in Figure 5.

Transmembrane and Protein Disorder Prediction

Protein transmembrane regions were predicted using TMHMM 2.0 (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM/). The percentage of protein disorder was predicted using ESpritz v1.3 (http://protein.bio.unipd.it/espritz/) with the prediction type set to Disprot and decision threshold set to Best Sw.

Pyrenoid Enrichment Analysis

To determine whether the pyrenoid showed selectivity regarding protein size we categorized chloroplast localized proteins into pyrenoid depleted or not pyrenoid depleted. The “all other localizations” included all non-chloroplast proteins.

Statistical tests

All statistical tests were performed in SPSS or Microsoft Excel.

DATA AND SOFTWARE AVAILABILITY

The computer code used for primer design is available at https://github.com/Jonikas-Lab/tagging_primer_design. The raw mass spectrometry data is available from PRIDE XXXX. Plasmid sequences in GenBank or Fasta format for the constructs generated in this study can be downloaded from: https://sites.google.com/site/chlamyspatialinteractome/ or Mendeley Data: http://dx.doi.org/10.17632/k5m9fd8nzw.1.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES

Protein localization images, z-stacks and an interactive protein-protein interaction network are available at: https://sites.google.com/site/chlamyspatialinteractome/.

Supplementary Material

Table S1. Summary of Target Gene Features, Cloning and Localization, Related to Figure 1

Table S5. Protein-Protein Interaction Data, Related to Figures 6 and 7

All interactions with a WD-score ≥1 are shown. Rows highlighted in blue were classified as HCIPs.

(A) The pLM006 vector used for dual tagging of proteins with mCherry.

(B) Dependence of cloning success on open reading frame (ORF) size.

(C) Relationship of cloning success to the number of fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (FPKM) from phototrophic air-grown cells.

(D) Distribution of FPKM values of cloned genes and genes where cloning failed.

(E) Relationship of localization success to the FPKM from phototrophic air-grown cells.

(F) Distribution of FPKM values of cloned and localized genes vs. cloned and not localized genes. (D) and (F) Brackets show significant difference using a Mann-Whitney U test.

(G) The relationship of localization success to presence of uATGs in transcripts. Asterisks denote significant differences using Fisher’s exact test: *** P <0.0001, ** P = 0.0025, * P = 0.025

(A) Representative confocal images demonstrating a diverse range of cytosolic localization patterns.

(B) Confocal images of successfully tagged and localized carbonic anhydrases. *The cloned construct was based on the CAH9 Augustus v5.0 gene model. Images for CAH5 and CAG1-3 are projected Z-stacks. (A) and (B) Scale bars: 5 μm.

(A) Confocal images of proteins with signals in defined puncta within the chloroplast.

(B) Localization of Proteins Associated with Photosynthetic Electron Transport. The images for PSBP4 and PSAH are the same as used in Figure 4B. (A) and (B) Scale bars: 5 μm.

Log2 fold changes of proteins upregulated (red) or downregulated (blue) in response to low CO2 are overlaid onto the HCIP protein-protein interaction network.

Hierarchical clustering of all 38 baits and preys having an interaction WD-score ≥1. Large regions of blue across most/all baits correspond to clusters of non-specific interactors.

Cre16.g655050 has a RbcX N-Terminal Domain and a Disordered C Terminus. Top: A predicted Phyre2 structural model of Cre16.g655050. The table shows the ten best template matches for Cre16.g655050 by Phyre2. The confidence score is the probability that the match between Cre16.g655050 and the template is a true homology. The % ID shows the percentage identity between Cre16.g655050 and the template.

Phylogenetic tree analysis of 259 eukaryotic P-type ATPases, including functionally characterized members representing the different P-type ATPase families. Chlamydomonas ACA4 groups with family IIIA P-type ATPases, which are involved in H+ pumping.

HIGHLIGHTS.

Localizations and physical interactions of candidate CCM proteins were determined

The data reveal three previously un-described pyrenoid layers and 89 pyrenoid proteins

Plasma membrane inorganic carbon transporters LCI1 and HLA3 form a complex

Carbonic anhydrase 6 localizes to the flagella, changing the model of the CCM

Acknowledgments

We thank Jonikas laboratory members for helpful discussions, Z. Friedberg and R. Vasquez for help with gene cloning, A. Okumu for mass spectrometry sample preparation, H. Cartwright for microscopy support, and U. Goodenough, R. Milo, A. Smith, N. Wingreen, T. Silhavy, M. Meyer and A. McCormick for comments on the manuscript. Stanford University Mass Spectrometry is thankful to the NIH, Award Number S10RR027425 from the NCRR for assistance in purchasing the mass spectrometer. The project was funded by NSF Grants EF-1105617 and IOS-1359682, NIH Grant 7DP2GM119137-02, the Simons Foundation and HHMI grant #55108535, Princeton University (M.C.J.); the University of York (L.C.M.M), and the Carnegie Institution for Science (L.C.M.M. and M.C.J.). Conflict of interest statement: The authors wish to note that the Carnegie Institution for Science has submitted a provisional patent application on aspects of the findings.

Footnotes

Supplemental Information includes 7 figures and 5 tables.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

L.C.M.M. and M.C.J. designed and supervised the study. L.C.M.M., C.C. and M.R. performed the cloning, L.C.M.M. did the microscopy and L.C.M.M. and C.C. carried out the AP-MS. S.R. and L.C.M.M. developed the affinity purification protocol. W.P. and S.R.B. provided bioinformatics support. R.L. and C.M.A. oversaw the mass spectrometry and peptide mapping. L.C.M.M., C.C. and M.C.J. analysed and interpreted the data. L.C.M.M created the figures. C.C. created the online viewing platform. L.C.M.M. and M.C.J. wrote the manuscript with input from all authors.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Atkinson N, Feike D, Mackinder L, Meyer MT, Griffiths H, Jonikas MC, Smith AM, McCormick AJ. Introducing an algal carbon-concentrating mechanism into higher plants: location and incorporation of key components. Plant Biotechnol J. 2016;14:1302–1315. doi: 10.1111/pbi.12497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atteia A, Adrait A, Brugière S, Tardif M, Van Lis R, Deusch O, Dagan T, Kuhn L, Gontero B, Martin W. A proteomic survey of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii mitochondria sheds new light on the metabolic plasticity of the organelle and on the nature of the α-proteobacterial mitochondrial ancestor. Mol Biol Evol. 2009;26:1533–1548. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msp068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badger M. The roles of carbonic anhydrases in photosynthetic CO2 concentrating mechanisms. Photosynthesis Res. 2003;77:83–94. doi: 10.1023/A:1025821717773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauwe H, Hagemann M, Fernie AR. Photorespiration: players, partners and origin. Trends Plant Sci. 2010;15:330–336. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrends C, Sowa ME, Gygi SP, Harper JW. Network organization of the human autophagy system. Nature. 2010;466:68–76. doi: 10.1038/nature09204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Shem A, Frolow F, Nelson N. Crystal structure of plant photosystem I. Nature. 2003;426:630–635. doi: 10.1038/nature02200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benlloch R, Shevela D, Hainzl T, Grundstrom C, Shutova T, Messinger J, Samuelsson G, Sauer-Eriksson AE. Crystal structure and functional characterization of photosystem II-associated carbonic anhydrase CAH3 in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Physiol. 2015;167:950–962. [Google Scholar]

- Bergeron-Sandoval LP, Safaee N, Michnick SW. Mechanisms and consequences of macromolecular phase separation. Cell. 2016;165:1067–1079. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco-Rivero A, Shutova T, Roman MJ, Villarejo A, Martinez F. Phosphorylation controls the localization and activation of the lumenal carbonic anhydrase in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. PloS one. 2012;7:e49063. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brueggeman AJ, Gangadharaiah DS, Cserhati MF, Casero D, Weeks DP, Ladunga I. Activation of the carbon concentrating mechanism by CO2 deprivation coincides with massive transcriptional restructuring in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant Cell. 2012;24:1860–1875. doi: 10.1105/tpc.111.093435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron JC, Wilson SC, Bernstein SL, Kerfeld CA. Biogenesis of a bacterial organelle: the carboxysome assembly pathway. Cell. 2013;155:1131–1140. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.10.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chevalier D, Morris ER, Walker JC. 14-3-3 and FHA domains mediate phosphoprotein interactions. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2009;60:67–91. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.59.032607.092844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi HI, Kim JYH, Kwak HS, Sung YJ, Sim SJ. Quantitative analysis of the chemotaxis of a green alga, Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, to bicarbonate using diffusion-based microfluidic device. Biomicrofluidics. 2016;10:014121. doi: 10.1063/1.4942756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross FR. Tying down loose ends in the Chlamydomonas genome: functional significance of abundant upstream open reading frames. G3: Genes|Genomes|Genetics. 2016;6:435–446. doi: 10.1534/g3.115.023119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depège N, Bellafiore S, Rochaix JD. Role of chloroplast protein kinase Stt7 in LHCII phosphorylation and state transition in Chlamydomonas. Science. 2003;299:1572–1575. doi: 10.1126/science.1081397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dismukes G, Klimov V, Baranov S, Kozlov YN, DasGupta J, Tyryshkin A. The origin of atmospheric oxygen on Earth: the innovation of oxygenic photosynthesis. PNAS. 2001;98:2170–2175. doi: 10.1073/pnas.061514798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias JE, Gygi SP. Target-decoy search strategy for increased confidence in large-scale protein identifications by mass spectrometry. Nat Methods. 2007;4:207–214. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emanuelsson O, Nielsen H, Brunak S, Von Heijne G. Predicting subcellular localization of proteins based on their N-terminal amino acid sequence. J Mol Biol. 2000;300:1005–1016. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel BD, Ishikawa H, Wemmer KA, Geimer S, Wakabayashi K-i, Hirono M, Craige B, Pazour GJ, Witman GB, Kamiya R. The role of retrograde intraflagellar transport in flagellar assembly, maintenance, and function. J Cell Biol. 2012;199:151–167. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201206068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel BD, Schaffer M, Kuhn Cuellar L, Villa E, Plitzko JM, Baumeister W. Native architecture of the Chlamydomonas chloroplast revealed by in situ cryo-electron tomography. eLife. 2015;4:e04889. doi: 10.7554/eLife.04889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang W, Si Y, Douglass S, Casero D, Merchant SS, Pellegrini M, Ladunga I, Liu P, Spalding MH. Transcriptome-wide changes in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii gene expression regulated by carbon dioxide and the CO2-concentrating mechanism regulator CIA5/CCM1. Plant Cell. 2012;24:1876–1893. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.097949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field CB, Behrenfeld MJ, Randerson JT, Falkowski P. Primary production of the biosphere: integrating terrestrial and oceanic components. Science. 1998;281:237–240. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5374.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuhrmann M, Oertel W, Hegemann P. A synthetic gene coding for the green fluorescent protein (GFP) is a versatile reporter in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Plant J. 1999;19:353–361. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1999.00526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson DG, Young L, Chuang RY, Venter JC, Hutchison CA, 3rd, Smith HO. Enzymatic assembly of DNA molecules up to several hundred kilobases. Nat Methods. 2009;6:343–345. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinnickel M, Kim RG, Wittkopp TM, Yang W, Walters KA, Herbert SK, Grossman AR. Tetratricopeptide repeat protein protects photosystem I from oxidative disruption during assembly. PNAS. 2016;113:2774–2779. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1524040113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]