Abstract

Background

Verbal augmented feedback (VAF) is commonly used in physiotherapy rehabilitation of individuals with lower extremity musculoskeletal dysfunction or to induce motor learning for injury prevention. Its effectiveness for acquisition, retention and transfer of learning of new skills in this population is unknown.

Objectives

First, to investigate the effect of VAF for rehabilitation and prevention of lower extremity musculoskeletal dysfunction. Second, to determine its effect on motor learning and the stages of acquisition, retention and transfer in this population.

Design

Systematic review designed in accordance with the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination and reported in line with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis.

Method

MEDLINE, Embase, PubMed and five additional databases were searched to identify primary studies with a focus on VAF for prevention and rehabilitation of lower extremity musculoskeletal dysfunction. One reviewer screened the titles and abstracts. Two reviewers retrieved full text articles for final inclusion. The first reviewer extracted data, whereas the second reviewer audited. Two reviewers independently assessed risk of bias and quality of evidence using Cochrane Collaboration’s tool and Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation, respectively.

Results

Six studies were included, with a total sample of 304 participants. Participants included patients with lateral ankle sprain (n=76), postoperative ACL reconstruction (n=16) and healthy individuals in injury prevention (n=212). All six studies included acquisition, whereas retention was found in five studies. Only one study examined transfer of the achieved motor learning (n=36). VAF was found to be effective for improving lower extremity biomechanics and postural control with moderate evidence from five studies.

Conclusion

VAF should be considered in the rehabilitation of lower extremity musculoskeletal dysfunctions. However, it cannot be unequivocally confirmed that VAF is effective in this population, owing to study heterogeneity and a lack of high-quality evidence. Nevertheless, positive effects on lower extremity biomechanics and postural control have been identified. This suggests that further research into this topic is warranted where an investigation of long-term effects of interventions is required. All stages (acquisition, retention and transfer) should be evaluated.

Keywords: verbal augmented feedback, motor learning, musculoskeletal dysfunction, lower extremity, injury prevention

What is already known?

Verbal augmented feedback is commonly used for exercise prescription; however, its effectiveness is unknown.

Exercise with an external focus is more effective for motor learning in musculoskeletal conditions, but it is unclear which modes are most beneficial for motor learning.

What are the new findings?

There is moderate evidence that verbal augmented feedback is effective in the rehabilitation of musculoskeletal lower limb injuries.

Future studies should evaluate outcomes relating to retention and transfer to evaluate achievement of motor learning.

Introduction

It is estimated that 22 million sports-related injuries occur annually in the UK alone, with the knee and ankle being common injury sites.1 According to Murphy, Connolly and Beynnon (2003), sports-related injuries are globally estimated to account for $1 billion per year in medical, sick leave and management costs. Rehabilitation and prevention of these musculoskeletal injuries constitute a significant part of physiotherapy workload, and societal and economic costs are considerable given many are of a working age.2

Exercise prescription is integral to physiotherapy rehabilitation and prevention of musculoskeletal injuries. As well as changes in skeletal muscle structure,3 exercise induces motor learning if done with sufficient repetition.4 5 Motor learning is defined as ‘a set of processes associated with practice or experience leading to relatively permanent changes in the capability for producing skilled action’ (p22). The process of motor learning is broken down into three key stages: (1) acquisition: the initial stage of learning a new skill, for example, performance of exercise, (2) retention: evidence of skill achievement after cessation of exercise and (3) transfer: the ability to perform the attained skill in a different motor task, including activities of daily life.5

An essential part of motor learning is neuroplasticity, which is the potential for the nervous system to change in response to sensory information.6 While much work has been done on motor learning in neurological conditions such as strokes,7–9 there has been less of a focus on the unimpaired brain, despite the healthy brain having a greater potential for change.9 10 Clinically, to achieve the desired outcomes such as motor learning, feedback on performance of exercises is required. To enhance motor learning, intrinsic and extrinsic approaches are advocated,11 where the former is mediated through an individual’s sensory system and the latter, also termed augmented feedback (AF), involves an external source, such as biofeedback instruments, a balance board or external verbal instructions or cues.11 12

Evidence suggests that AF is effective for motor learning achievement12 13; however, high-quality research is lacking. AF comprises a range of modes, in general content, timing and focus of attention. In terms of focus of attention, verbal augmented feedback (VAF) can either be delivered where the feedback is focused towards the body or the body part (internal) or where the movement’s effect on the environment is the focus (external).9 11 14 A recent systematic review concluded that exercise with an external focus is more effective for motor learning in musculoskeletal conditions9; however, it is unclear which modes of VAF may be most beneficial to induce motor learning and in turn enhance the effectiveness of injury rehabilitation and prevention.

VAF is already widely used in practice during retraining of individuals with lower limb injuries having the advantage of not requiring costly equipment. However, in the absence of robust evidence, an investigation of verbal feedback as a form of AF on motor learning is required to underpin clinical practice. Additionally, a closer look at retention and transfer tests of newly gained motor skills would be of high interest. Until now, no systematic reviews have investigated the effect of VAF on musculoskeletal dysfunctions. Therefore, the main objective of this study was to determine the effect of VAF in the rehabilitation and prevention of lower extremity musculoskeletal dysfunctions. A secondary objective was to evaluate the effect of VAF on motor learning with respect to the key stages of acquisition, retention and transfer.

Methods

Protocol and registration

A protocol was developed in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement and registered with International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (CRD42016035349). The actual review is reported in accordance with the PRISMA statement, and the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions was used to inform the conduct of the study.

Eligibility criteria

The search strategy was informed through consultation with individuals with subject and methodological expertise (NH, SS, PvV) and following a scoping search. It was devised to answer the question and framed in accordance with patient, intervention, comparison, outcome, study design (PICOS).

Participants

Studies containing participants with a musculoskeletal dysfunction/injury or healthy subjects at risk of developing a lower extremity musculoskeletal injury (injury prevention) were included.

Intervention

Studies with the aim of assessing the effect of VAF and investigating the effect of focus of attention (internal or external) as way of providing VAF were included.11 However, articles focusing on video feedback and general instructions were excluded. Instructions were considered as general if they were not focused on biomechanics of the lower limbs, for example, instructions that were not intended as the intervention. Results for VAF had to be presented separately to that of other interventions if present. Someone other than the participant, such as the therapist, had to provide the feedback (self-talk as feedback was excluded). Finally, the VAF had to be delivered verbally by the therapist prior to or during the performance of the task.

Comparison

Studies had to compare VAF with either different types of AF, no AF or a control condition.

Outcome

Studies needed to include an outcome measure related to motor learning such as improvement (or loss) of lower extremity biomechanics/postural control in different motor learning stages (acquisition, retention and transfer).

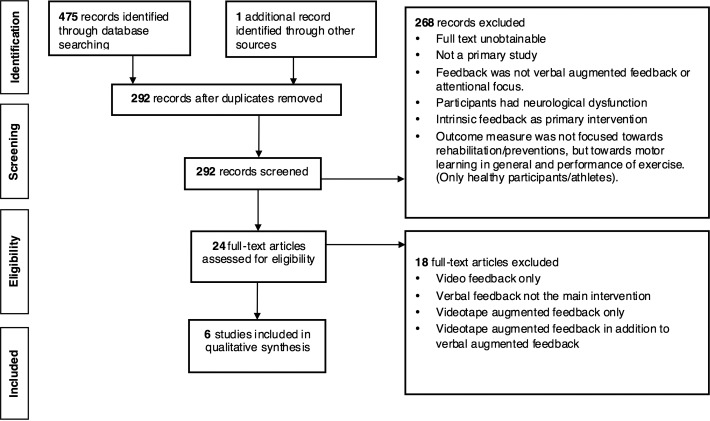

If the outcome measure was not focused towards rehabilitation/prevention of lower limb injuries, for example, lower extremity biomechanics, the articles were excluded (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart illustrating search process and identification of studies.

Study design

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs), quasi-randomised controlled studies, cross-over designs, single case experimental, pre–post studies using primary data were included. Case studies were excluded owing to their low ranking on the research pyramid. Studies where the full text could not be retrieved (ie, conference abstracts) and non-human studies were also excluded.

Information sources and search

Bibliographic databases were searched from 28 September 2015 to 26 December 2016. MEDLINE (1946– to January week 2 2016), Embase (1974 to January 2016), Physiotherapy Evidence Database, Cinahl Plus, ProQuest, Web of Science, PubMed and Cochrane Library were used to find eligible studies. Grey literature, relevant reviews or books about motor learning and reference lists of primary studies were searched to find supplementary papers and information. Search strategies were developed in MEDLINE using Medical Subject Headings (MESH) and free text (table 1). Search strategies for the other databases were based on the MEDLINE search and developed in consultation with a biomedical librarian.

Table 1.

MEDLINE search strategy: Ovid MEDLINE(R) 1946 to December week 4 2016

| Search term | |

| 1 | Feedback/ |

| 2 | Motor learning.mp |

| 3 | Augmented feedback |

| 4 | attentional focus.mp. |

| 5 | focus of attention.mp. |

| 6 | injury.mp. |

| 7 | jump.mp. |

| 8 | landing.mp. |

| 9 | biomechanics.mp. |

| 10 | Ankle/ or ankle.mp. |

| 11 | sprain.mp. |

| 12 | exp Anterior Cruciate Ligament/ |

| 13 | kinematics.mp. |

| 14 | Transfer.mp. |

| 15 | Acquisition.mp. |

| 16 | retention.mp. |

| 17 | exp Learning/ |

| 18 | extrinsic feedback.mp. |

| 19 | verbal feedback.mp. |

| 20 | Instruction.mp. |

| 21 | Ground reaction force.mp. |

| 22 | exp Kinetics/ |

| 23 | exp Lower Extremity/ |

| 24 | external focus of attention.mp. |

| 25 | exp Motor Skills/ |

| 26 | injury prevention.mp. |

| 27 | exp Rehabilitation/ |

| 28 | 3 and 26 |

| 29 | 21 and 24 |

| 30 | 2 and 3 and 6 |

| 31 | 3 and 8 and 9 |

| 32 | 2 and 3 |

| 33 | 2 and 4 |

| 34 | 3 and 26 |

Study selection

One reviewer screened the title and abstract of studies (MS), in line with the inclusion criteria. Full text articles were retrieved and screened by two reviewers (MS and LHJG). In any case of disagreements, consensus was reached by discussion, or a third reviewer (NH) was consulted if needed. The management of the included papers and removal of duplicates were supported by the Reference Manager Software RefWorks.

Data collection process

Study data were extracted by the first reviewer (MS) and audited for accuracy by the second reviewer (LHJG). A data extraction form was created prior to the collection and was piloted to avoid any discrepancies of interpretation. Details of the extracted information are reported in table 2 (study characteristic and outcome) and table 5 (results). Consensus between reviewers (MS and LHJG) was attained by dialogue, and an opinion from the third reviewer (NH) was sought if necessary.

Table 2.

Study characteristics and outcomes

| Study: name of authors, year | Setting/country | Injury/injury prevention and exercise | Study design | Population | Type of feedback | Outcome measures | |

| 1 | Benjaminse et al, 201529 | Controlled laboratory setting/The Netherlands | ACL injury prevention. Sidestep cutting. |

RCT | n=90 healthy recreational basketball players Female: 45 Male: 45 Mean age: Female: 22.3 Male: 24.9 |

EFA by a visual stimuli compared with IFA by a verbal stimulus Control: no feedback. General instructions prior to task. VAF: “Bend your trunk forward, bend your knee and keep your knee straight above your foot”. (p2) Enough time to warm up and familiarisation. Three trials |

Vertical ground reaction force, knee kinetics and knee kinematics (sagittal angles and moments of the trunk, hip, knee, ankle and range of motion. Frontal knee plane moment) for acquisition and retention. Two retention sessions without feedback: after 1 week and 4 weeks. |

| 2 | Gokeler et al, 201528 | Outpatient physical therapy facility/The Netherlands | MSK injury: postop ACL reconstruction. (>4 months post-ACLR). Single leg hop jump. |

Between-group experimental design (randomisation) | n=16 patients Female: 7 Male: 9 Mean age: Internal focus: 23.75 External focus: 22.63 |

EFA versus IFA. VAF: EFA: “… I want you to think about pushing yourself off as hard as possible from the floor”. IFA: “… I want you to think about extending your knees as rapidly as possible”. (p116) 5 min warm-up. Three times practice. Five trials. 30 s recovery time trial/jump. |

Jump distance, knee valgus angle at initial contact, peak knee valgus angle, knee flexion angle at initial contact, peak knee flexion ankle, total ROM and time to peak angles for acquisition. (Successful jump if patient could keep balance for at least 2 s postlanding). |

| 3 | Laufer et al, 200723 | Military outpatient physical therapy/Israel | MSK injury: <4 months postgrade 1 or 2 ankle sprain. Balance training on a dynamic stabiliometer. |

RCT | n=40 volunteers. Female: 4 Male: 36 Mean age: IFA: 21.1 EFA: 20.5 |

EFA versus IFA. VAF: EFA: “Keep your balance by stabilising the platform”. IFA: “Keep your balance by stabilising your body”. (p106) Two practice trials (30 s each) Two tests (20 s each) 30 s rest between trials |

Main outcome measure: overall stability for acquisition and retention (48 hours). APSI, OSI and MLSI. |

| 4 | Prapavessis and McNair, 199924 | University of Auckland/New Zealand | MSK injury risk: prevention of injury of lower limb. Vertical jump. |

RCT | n=91 volunteers Female: 35 Male: 56 Augmented: 41 (26 males and 15 females) Sensory: 50 (30 males and 20 females) Mean age: 16.07 |

VAF versus IF VAF: (focus on the control of specific joint movement during landing); “When you do your next jump, position yourself on the balls of your feet with bent knees just prior to landing. On landing, lower the heels slowly to the ground and bend the knees until well after the landing”.24 (p354) IF: use the experience of their first jump to land in a way that would minimise the stress of their next landing. No warm-up, break and practice reported. |

Reduced GRF from vertical jump for short-term effect for acquisition. |

| 5 | Rotem-Lehrer and Laufer, 200725 | Military outpatient physical therapy department/Israel | MSK injury: <4 months postgrade 1 or 2 ankle sprain. Balance training on stabiliometer. |

RCT | n=36 male volunteers Mean age: 20.9 |

EFA versus IFA. EFA: “Keep your balance by stabilising the platform”. IFA: “Keep your balance by stabilising your body”. (p566) 20 practice trials (20 s each). 30 s rest between trials. |

Acquisition and transfer of a learnt balance capability/postural control to a more advanced task (48 hours). APSI, OSI and MLSI |

| 6 | Weilbrenner, 201426 | Oregon State University/ USA |

MSK injury risk: prevention of ACL injury. Double leg jump task. |

Thesis project: blocked randomisation design (counterbalance). Unpublished. |

n=31 volunteers with no injury Female: 16 Male: 15 Feedback: 8 females and 7 males Mean age: 21.3 Control: 8 females and 8 males Mean age: 21.0 |

EFA versus control group. Both groups were told to ‘jump as high as possible’. Feedback group received additional instruction: VAF: (One-time dose of external feedback) “Focus on landing as light as a feather”. (p20) Warm-up, three practice trials, 30 s rest between the five training trials. |

Change of landing biomechanics for prevention of ACL injury (acquisition and retention, 48 hours). Successful trial if participants landed with both feet at the same time and in the right position. |

ACLR, anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction; APSI, Anterior/Posterior Stability Index; EFA, external focus of attention; GRF, ground reaction force; IF, intrinsic feedback; IFA, internal focus of attention; MSK, musculoskeletal; MLSI, Medial/Lateral Stability Index; OSI, Overall Stability Index; postop ACL, postoperative anterior cruciate ligament; RCT, randomised controlled trial; ROM, range of motion; VAF, verbal augmented feedback.

Table 5.

Results

| Study | Effect | Motor control stages and authors’ conclusion | Additional comments/overall risk of bias within the study | |

| 1 | Benjaminse et al, 201529 |

|

Acquisition & retention

Male participants benefit from visual feedback. Visual feedback reduces knee joint loading in males with high retention |

|

| 2 | Gokeler et al, 201528 |

|

Acquisition

EFA is more beneficial than IFA for motor skill performance |

|

| 3 | Laufer et al, 200723 | Stability level 6:

|

Acquisition & retention

VAF (EFA) is advantageous for learning postural control task (especially for acquisition phase) over three sessions |

|

| 4 | Prapavessis and McNair, 199924 |

|

Acquisition

Adolescents need more information than that provided by their prior experiences in jumping—to lower GRF in landing. It is evident that those receiving VAF can pick up instructions related to improvements of lower limb kinematics |

|

| 5 | Rotem-Lehrer and Laufer, 200725 |

|

Acquisition and transfer. VAF (EFA) is advantageous for transfer of postural control task over a 3-day period |

|

| 6 | Weilbrenner, 201426 | Kinematics:

|

Acquisition & retention

The VAF did not change landing biomechanics |

|

AF, augmented feedback; APSI, Anterior/Posterior Stability Index; CTRL, control; EFA, external focus of attention; GRF, ground reaction force; IC, initial contact; IFA, internal focus of attention; MLSI, Medial/Lateral Stability Index; OSI, Overall Stability Index; p, p-value; PATSF, peak anterior tibial shear force; VAF, verbal augmented feedback; VER, verbal; vGRF, vertical ground reactions force; VIS, visual.

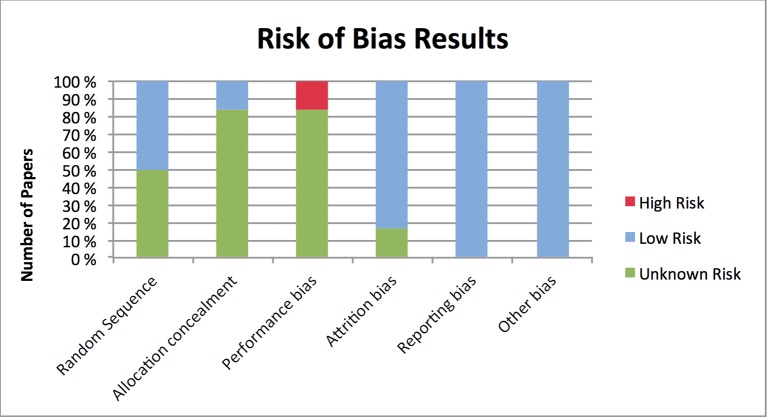

Risk of bias in individual studies

The two reviewers (MS and LHJG) independently assessed risk of bias by using the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool (see table 3). Each study was rated against the defined types of bias. One of the excluded studies was used as a pilot. The inter-rater agreement for study bias ratings between the reviewers was measured using the Cohen’s kappa statistics. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion. A third reviewer (NH) was consulted if needed.

Table 3.

Summary assessment of the overall risk of bias—Cochrane Collaboration’s tool

| Study | Different types of bias | Summary within study | Overall risk | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||||

| 1 | Benjaminse et al, 201529 | U | U | H | U | L | L | H=1 L=2 U=3 |

Enrolment, allocation and testing done by the same person. Lack of information in terms of selection and attrition |

| 2 | Gokeler et al, 201528 | L | L | U | L | L | L | H=0 L=5 U=1 |

Lack of information in terms of blinding |

| 3 | Laufer et al, 200723 | U | U | U | L | L | L | H=0 L=3 U=3 |

Lack of information in terms of selection bias and blinding |

| 4 | Prapavessis and McNair, 199924 | L | U | U | L | L | L | H=0 L=4 U=2 |

Allocation concealment not reported. Lack of information in terms of blinding |

| 5 | Rotem-Lehrer and Laufer, 200725 | U | U | U | L | L | H=0 L=3 U=3 |

Lack of information in terms of selection bias and blinding | |

| 6 | Weilbrenner, 201426 | L | U | U | L | L | L | H=0 L=4 U=2 |

Allocation concealment and blinding not reported |

Risk of bias criteria: 1, selection bias=random sequence generation; 2, selection bias=allocation concealment; 3, performance bias/detection bias=blinding of personnel and blinding of participants/blinding of outcome assessors; 4, attrition bias=incomplete outcome data; 5, reporting bias=short-term selective outcome reporting; 6, other bias=potential threats to validity, for example, consideration of a protocol. Levels of risk of bias: H, high risk of bias; L, low risk of bias and U, unclear risk of bias.

Quality of evidence

Two reviewers (MS and LHJG) assessed the studies’ quality of evidence for each main outcome using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE)15 16 system (table 4).

Table 4.

Quality of body of evidence based on the GRADE approach

| Outcome | Number of studies | Limitation | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Publication bias | Upgrade | Summary/quality of evidence |

| Jump distance | 1 RCT | No serious limitation | NA | No serious indirectness | −1 | None | +1 | High ⨁⨁⨁⨁ |

| Stability/postural control/balance | 2 RCTs23 25 | −1 | None | No serious indirectness | −1 | None | +1 | Moderate ⨁⨁⨁ |

| GRF | 2 RCTs1 24 | −1 | None | No serious indirectness | −1 | None | +1 | Moderate ⨁⨁⨁ |

| Knee kinematics | 2 RCTs1 22

1 blocked randomised design |

−1 | None | No serious indirectness | −1 | None | +1 | Moderate ⨁⨁⨁ |

All RCTs start as high quality. Assessment criteria: limitation: based on Cochrane risk of bias assessment. Downgraded by one level if more than one unclear. Inconsistency: unexplained heterogeneity across studies. indirectness: heterogeneity for participants, intervention or outcome measure in individual studies. imprecision: if no sample size justification and calculation: downgraded by one level. Publication bias. Upgrade: if statistically significant effect: upgraded by one level.16

GRADE, Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation; GRF, ground reaction force; RCT, randomised controlled trial.

Synthesis of results

Final results derived from the risk of bias analysis and quality assessment were included in the synthesis and analysis of data. Owing to the heterogeneity across the studies, a meta-analysis was not appropriate. Narrative reporting was therefore used to synthesise results.

Results

Study selection

The search yielded 292 studies after duplicates were removed. Screening of titles and abstracts resulted in 24 studies being retrieved. Eleven of these were included for further eligibility check. Five studies17–21 were excluded leaving six studies to be included in the analysis1 22–26 as agreed by the reviewers (MS, LHJG and NH).

Study characteristics

Table 2 summarises the characteristics of the included studies. There were five RCTs1 22–25 and one blocked randomised design.26 Three of the studies enrolled participants with a musculoskeletal injury, of which two studies had participants with lateral ankle sprain23 25, and the third investigated individuals with postoperative anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction.22 The remaining three studies enrolled healthy participants.1 24 26 The total sample size of all six studies was 304; 92 injured participants and 212 healthy. Three studies compared external focus of attention (EFA) verbal feedback to internal focus of attention (IFA) verbal feedback.22 23 25 One study compared EFA verbal feedback to a control group. One study compared VAF with no AF (they relied on their own intrinsic sensory systems), and one study compared VAF only to a control group.26 The outcome measures of the included studies were jump distance,22 stability/balance/postural control,22 23 25 ground reaction force1 22 24 and knee kinematics.1 26

Risk of bias within the studies

The percentage agreement between the two reviewers’ risk of bias was 90.5% with kappa=0.806 (CI 0.626 to 0.987). Five of the studies presented unclear risk of bias regarding allocation concealment.1 23–26 One study had low risk for allocation concealment.22 Three studies had an unclear risk of bias owing to poor reporting on randomisation sequence,23 25 the remaining were low risk or not applicable. Five studies showed poor reporting in terms of blinding, and one study had high risk. With regard to reporting and other biases, all studies had low risk of bias. One study had unknown risk for attrition bias, the rest were rated as low (figure 2 and table 3). All studies had an overall unclear risk of bias, in accordance with the descriptions of overall risk of bias within the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions.27

Figure 2.

Risk of bias (high, unknown and low) within studies in terms of different categories.

Quality of body of evidence

Using GRADE (table 4), all bodies of evidence were downgraded owing to imprecision. All outcomes were downgraded owing to the lack of sample size justification and calculation (imprecision). Out of the quality classification, three studies were of moderate and one high quality. In total, four outcomes (jump distance, stability/postural control/balance, ground reaction force and knee kinematics) were assessed.

Synthesis of results

The results are summarised in table 5 in a narrative form as the studies demonstrated heterogeneity with respect to participants, sample, sample size, protocol, interventions and outcome measures. The selection of VAF phrases used during the intervention in the studies can be found in table 2.

Effect of VAF (EFA vs IFA) for musculoskeletal injury

Three RCTs, with moderate to high strength of evidence, looked at EFA versus IFA in participants with a musculoskeletal injury.22 23 25 The study by Gokeler et al28 looked at the stage of acquisition and provided VAF prior to testing. The study found no statistical differences between the EFA and IFA groups in terms of jump distance. For knee kinematics, the IFA group had significantly lower knee flexion compared with the EFA group. Laufer et al23 assessed acquisition and retention (48 hours post-test) and reported an effect primarily for stance phase after three sessions of training balance. Compared with IFA, EFA was superior on the effect of balance in the simpler stance position, especially for the acquisition phase. Retention tests showed maintenance of newly gained skills. Rotem-Lehrer and Laufer25 tested transfer of a postural control task (48 hours post-test) and showed significant differences in all stability measures of pretraining and post-training for EFA rather than IFA. For both studies,23 25 no VAF was given during the assessment, only for training.

Effect of VAF versus intrinsic feedback for musculoskeletal injury prevention (healthy participants only)

Moderate evidence from one RCT demonstrated a significantly lower ground reaction force for VAF compared with intrinsic feedback in musculoskeletal injury prevention. VAF was provided during testing in the acquisition stage only.

Effect of VAF versus control for musculoskeletal injury prevention (healthy participants only)

Two studies,1 26 with moderate evidence, compared VAF with a control group in musculoskeletal injury prevention during the stages of acquisition and retention. The former study also included a visual feedback (video) group. In this study, no feedback was given in the retention test. In the VAF group, significant effects for all sessions were found for knee flexion angles in females only, compared with video and control group. Males in the video group had larger ground reactions (all sessions), greater knee flexion (regardless of sessions) and reduced knee valgus moment (over time) compared with the VAF group and the control group.1 Weilbrenner26 did not find any significant changes in landing biomechanics for VAF during the task versus the control group.

Discussion

The purpose of this review was to determine the effect of VAF in the rehabilitation and prevention of musculoskeletal dysfunctions in the lower limbs, as well as to determine its effect on the different motor learning stages; acquisition, retention and transfer. Five out of six studies reported statistically significant effects for VAF. With evidence of moderate quality from five out of six studies, VAF was found to be effective for improving ground reaction force and lower extremity biomechanics (acquisition and retention) and postural control (transfer), which are all crucial factors in rehabilitation and prevention of injuries. Four out of the six studies did not include a control group22–25 and cannot support VAF over any other intervention or no intervention.

Caution should be made in interpreting this evidence given all studies were classed as unclear risk of bias (figure 1 and table 3) and the evidence indicates a low statistical credibility (table 5). Notwithstanding this, the overall body of evidence was deemed of a moderate quality (table 4), which means that further research can alter the estimated effect and beliefs about the strength of the evidence.15

Effect of VAF (EFA vs IFA) for MSK injury

In the study by Gokeler et al,28 both landing strategy and jump distance were measured. In terms of the former, the IFA group’s landing strategy was assessed as stiffer compared with the EFA group. Theoretically, this can lead to the risk of developing an ACL injury.22 Therefore, in this case, VAF with an EFA may be beneficial for anterior cruciate ligament injury prevention and motor learning achievement. For jump distance, there were no statistical effects. Gokeler et al28 suggest that an extra stimulus could be necessary to achieve a significant effect for jump distance. Additionally, a different wording of VAF, for example, instructing the participant to reach as well as jump, can improve the effect of motor learning.22

Laufer et al23 and Rotem-Lehrer and Laufer25 looked at postural control. They both found optimistic results for EFA as way of providing VAF in the rehabilitation of musculoskeletal dysfunctions, as postural control enhancement is crucial for secondary prevention of lateral ankle sprains.23 25

Effect of VAF versus IF for MSK injury prevention (healthy participants only)

Healthy participants in the study by Prapavessis and McNair24 demonstrated motor learning achievement in terms of reduced ground reaction force after receiving VAF. A lower ground reaction force improves landing biomechanics and can in turn prevent injuries if kept doing the same way in practice. However, the investigators only looked at the stage of acquisition, and a relatively permanent change (ie, motor learning) was not confirmed. Additionally, an investigation of injured participants is required to be able to confirm the effect for (secondary) injury prevention.

Effect of VAF versus control for MSK injury prevention (healthy participants only)

Benjaminse et al29 did not find positive effects in the VAF group (with IFA) regarding lower extremity biomechanics, compared with the visual feedback group (with EFA) and control group. This may suggest that EFA is better than IFA and supports previous findings stated in the Introduction.9 Weilbrenner26 cannot support the use of VAF with external focus of attention for primary ACL injury prevention in individuals who have not sustained a previous anterior cruciate ligament injury. This study did however differ from all the other studies in that the VAF did not include suggestions as to how to use the body during the test (instead used a metaphor—‘as light as a feather’). This may suggest that a mental imagery could prove less effective as feedback during exercise compared with actual verbal feedback.

Motor learning: stages and achievement

Acquisition is key to motor learning; however, retention and transfer are even more important in order to prevent injuries. The ability to show satisfactory results in retention and transfer tests is important considering the new tasks and challenges concerned with returning to play.29 Retention is the patient’s ability to show skill achievement or improvement of the same task some time after the acquisition phase, without having practised it.30 Transfer, on the other hand, requires additional skills where the patient has to demonstrate motor learning in a different, yet similar task.5 30 A skill is therefore not considered as fully learnt before the patient can show successful results in retention and transfer tests. It is important to bear in mind though that these tests do not always give us straightforward conclusions owing to factors such as temporary fatigue or anxiety.30

Only one study tested transfer, the rest of the studies assessed solely acquisition and retention (three) or acquisition alone (two). In view of the two studies testing short-term effects (acquisition and retention),3 24 an answer to whether a motor learning achievement was present cannot truly be obtained without a transfer test, as learning only occurs if the participants can show relatively permanent changes.5 31 However, the question then becomes, how long does it take before a change can be reasonably considered as long-term? The longest follow-up was 4 weeks. Prapavessis and McNair24 suggest that a longer follow-up, such as a year, could provide more realistic results. It might however depend on the intensity and frequency of the exercise, as to how long an effect is expected to last.

Analysis in relation to existing evidence

Regarding the first objective, the present review supports previous findings stating that there is a lack of quantity and quality of current evidence for VAF and musculoskeletal dysfunctions,12 13 and it is therefore not possible to determine whether VAF is effective. In terms of focus of attention, the results from three of the included papers22 23 25 support previous evidence that VAF with EFA is more effective than VAF with IFA.9 12 32 They all confirmed statistically significant results regarding EFA and VAF, but conclusions should be taken with caution owing to an overall moderate quality of evidence.

Strengths and limitations

The review used a thorough literature search in eight databases, inclusion and exclusion criteria were developed a priori and the protocol was registered. The review is written in line with PRISMA, and GRADE was used to determine the overall quality of the synthesised results.

Only six studies were identified for inclusion and in order to involve a sufficient number of studies, studies of injury prevention were included. Owing to the heterogeneity of the studies, a meta-analysis was not appropriate.

Moreover, it should be noted that the protocols differed between the studies and showed a wide variation with respect to sample, intervention, outcome measure, gender, time for practice, warm-up and rest. Rest might influence performance in terms of preparing the body for exercise and to prevent fatigue.26 Time postmusculoskeletal injury differed among studies (table 2), and both novice and experienced sporting participants were included. This means that pain scores, balance and skills will vary between the subjects—factors that may influence the level of motor learning achievement. Another factor to consider is the participants’ age and gender. All six studies included relatively young subjects, usually adolescents and both males and/or females. It is said that females have a higher risk of developing injury in puberty, and testing females at this age is important for injury prevention. However, transferring these results to the management of males or adults/elderly may not be possible.

Clinical and research implications

Based on the above findings, it is still unclear whether physiotherapists can fully trust current evidence in terms of providing VAF in a clinical context with respect to musculoskeletal injuries in the lower limbs. The systematic review has detected inconsistencies with the use of VAF in published studies. Furthermore, examination of healthy participants is not sufficient to demonstrate whether VAF is effective in the rehabilitation of musculoskeletal dysfunctions. To provide more clinical relevance, future studies are recommended to test individuals suffering from a musculoskeletal injury. Further use of reporting guidelines for research publications may enhance the quality of the evidence base by ensuring a robust methodological process is used with transparent designs and methods.

To determine best practices, it would be relevant to look at other aspects of VAF delivery, such as timing and frequency of all three fundamental stages of motor learning: acquisition, retention and transfer. Looking at the current systematic review, transfer was assessed 48 hours after the acquisition phase, and retention was tested 4 weeks (no feedback provided) or 48 hours23 26 postacquisition stage. (Feedback was provided in the latter study). In studies looking at the stroke population and the group of healthy participants, i there is a wide variation in terms of timing of retention and transfer tests following acquisition phase: 1 day, 2 days, 3 days, 1 week, 4 weeks and 7 weeks.32–36 One study defined two types of retention tests: immediate retention (5 min) or delayed retention (next day).37

In light of the heterogeneity of evidence, recommendations cannot be made regarding timing of retention and transfer tests postacquisition stage. It does however seem like a minimum of 24 hours postacquisition stage should be a requirement for retention and transfer tests. In addition, several studies agree on the fact that no feedback in these tests should be provided. One thing is clear; there is a need for the development of a standard by which these tests must be conducted. In terms of the interventions chosen, they should be in line with the Medical Research Council Framework for Complex Interventions.38 Ultimately, we need the interventions to bring out meaningful long-term outcomes such as return to play or reduced prevalence of injury—to provide physiotherapists with confidence within the evidence based clinical practice.

Conclusion

The results from this systematic review suggest that there is moderate evidence that VAF is effective in the rehabilitation and prevention of lower extremity musculoskeletal dysfunctions. From this review and notwithstanding the lack of high-quality evidence, improvements in terms of lower extremity biomechanics in a jumping task or enhanced postural control while balancing were found following VAF. Future high-quality studies are required to specifically evaluate VAF, including different parameters associated with feedback and long-term effects of interventions, where acquisition, retention and transfer are evaluated.

Footnotes

Contributors: MS was the first reviewer. LHJG was the second reviewer. SS, PvV and NH were coauthors. All authors read, edited and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The funding of the publication will be covered by the University of Birmingham.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Benjaminse A, Otten B, Gokeler A, et al. . Motor learning strategies in basketball players and its implications for ACL injury prevention: a randomized controlled trial. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2017;25:2365–76. 10.1007/s00167-015-3727-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Woolf AD, Pfleger B. Burden of major musculoskeletal conditions. Bull World Health Organ 2003;81:646–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Flück M. Functional, structural and molecular plasticity of mammalian skeletal muscle in response to exercise stimuli. J Exp Biol 2006;209:2239–48. 10.1242/jeb.02149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Magill R. Motor learning and control. 1st ed New York: McGraw-Hill, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muratori LM, Lamberg EM, Quinn L, et al. . Applying principles of motor learning and control to upper extremity rehabilitation. J Hand Ther 2013;26:94–103. 10.1016/j.jht.2012.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Snodgrass SJ, Heneghan NR, Tsao H, et al. . Recognising neuroplasticity in musculoskeletal rehabilitation: a basis for greater collaboration between musculoskeletal and neurological physiotherapists. Man Ther 2014;19:614–7. 10.1016/j.math.2014.01.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buchbinder R, Maher C, Harris IA. Setting the research agenda for improving health care in musculoskeletal disorders. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2015;11:597–605. 10.1038/nrrheum.2015.81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Durham KF, Sackley CM, Wright CC, et al. . Attentional focus of feedback for improving performance of reach-to-grasp after stroke: a randomised crossover study. Physiotherapy 2014;100:108–15. 10.1016/j.physio.2013.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sturmberg C, Marquez J, Heneghan N, et al. . Attentional focus of feedback and instructions in the treatment of musculoskeletal dysfunction: a systematic review. Man Ther 2013;18:458–67. 10.1016/j.math.2013.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Vliet PM, Heneghan NR. Motor control and the management of musculoskeletal dysfunction. Man Ther 2006;11:208–13. 10.1016/j.math.2006.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ribeiro DC, Sole G, Abbott JH, et al. . A rationale for the provision of extrinsic feedback towards management of low back pain. Man Ther 2011;16:301–5. 10.1016/j.math.2011.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sigrist R, Rauter G, Riener R, et al. . Augmented visual, auditory, haptic, and multimodal feedback in motor learning: a review. Psychon Bull Rev 2013;20:21–53. 10.3758/s13423-012-0333-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hartveld A, Hegarty J. Augmented feedback and physiotherapy practice. Physiotherapy 1996;82:480–90. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wulf G, Schmidt RA. Feedback-induced variability and the learning of generalized motor programs. J Mot Behav 1994;26:348–61. 10.1080/00222895.1994.9941691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, et al. . GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2008;336:924–6. 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schünemann H, Brozek J, Guyatt G, et al. . GRADE Handbook, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Munro A, Herrington L. The effect of videotape augmented feedback on drop jump landing strategy: Implications for anterior cruciate ligament and patellofemoral joint injury prevention. Knee 2014;21:891–5. 10.1016/j.knee.2014.05.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Myer GD, Stroube BW, DiCesare CA, et al. . Augmented feedback supports skill transfer and reduces high-risk injury landing mechanics. Am J Sports Med 2013;41:669–77. 10.1177/0363546512472977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Onate JA, Guskiewicz KM, Sullivan RJ. Augmented feedback reduces jump landing forces. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2001;31:511–7. 10.2519/jospt.2001.31.9.511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parsons JL, Alexander MJ. Modifying spike jump landing biomechanics in female adolescent volleyball athletes using video and verbal feedback. J Strength Cond Res 2012;26:1076–84. 10.1519/JSC.0b013e31822e5876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stroube BW, Myer GD, Brent JL, et al. . Effects of task-specific augmented feedback on deficit modification during performance of the tuck-jump exercise. J Sport Rehabil 2013;22:7–18. 10.1123/jsr.22.1.7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gokeler A, Benjaminse A, Hewett TE, et al. . Feedback techniques to target functional deficits following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: implications for motor control and reduction of second injury risk. Sports Med 2013;43:1065–74. 10.1007/s40279-013-0095-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laufer Y, Rotem-Lehrer N, Ronen Z, et al. . Effect of attention focus on acquisition and retention of postural control following ankle sprain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2007;88:105–8. 10.1016/j.apmr.2006.10.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Prapavessis H, McNair PJ. Effects of instruction in jumping technique and experience jumping on ground reaction forces. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 1999;29:352–6. 10.2519/jospt.1999.29.6.352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rotem-Lehrer N, Laufer Y. Effect of focus of attention on transfer of a postural control task following an ankle sprain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2007;37:564–9. 10.2519/jospt.2007.2519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Weilbrenner J. The influence of external focus of attention feedback on ACL injury related landing biomechanics Honors baccaluareate of exercise and sports sciences. Oregon State University 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Higgins J, Green S, The Cochrane Collaboration. Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in included studies In: Higgins J, Green S, eds Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. 1st ed, Version 5.1.0 [Updated March 2011]; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gokeler A, Benjaminse A, Welling W, et al. . The effects of attentional focus on jump performance and knee joint kinematics in patients after ACL reconstruction. Phys Ther Sport 2015;16:114–20. 10.1016/j.ptsp.2014.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Benjaminse A, Gokeler A, Dowling AV, et al. . Optimization of the anterior cruciate ligament injury prevention paradigm: novel feedback techniques to enhance motor learning and reduce injury risk. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2015;45:170–82. 10.2519/jospt.2015.4986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmidt R, Lee T. Motor control and learning. 1st ed Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shumway-Cook A, Woollacott M. Motor control. 4th ed Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wulf G. Attentional focus and motor learning: a review of 15 years. Int Rev Sport Exerc Psychol 2013;6:77–104. 10.1080/1750984X.2012.723728 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Vliet PM, Wulf G. Extrinsic feedback for motor learning after stroke: what is the evidence? Disabil Rehabil 2006;28:831–40. 10.1080/09638280500534937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wulf G, McConnel N, Gärtner M, et al. . Enhancing the learning of sport skills through external-focus feedback. J Mot Behav 2002;34:171–82. 10.1080/00222890209601939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wulf G, Prinz W. Directing attention to movement effects enhances learning: a review. Psychon Bull Rev 2001;8:648–60. 10.3758/BF03196201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wulf G. Attention and motor skill learning. 1st ed Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wulf G, Chiviacowsky S, Schiller E, et al. . Frequent external-focus feedback enhances motor learning. Front Psychol 2010;1:1 10.3389/fpsyg.2010.00190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, et al. . Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ 2008;337:a1655 10.1136/bmj.a1655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]