Abstract

Background

Social inequality trends in life expectancy are not informative as to changes in social disparity in the age-at-death distribution. The purpose of the study was to investigate social differentials in trends and patterns of adult mortality in Denmark.

Methods

Register data on income and mortality from 1986 to 2014 were used to investigate trends in life expectancy, life disparity and the threshold age that separates ‘premature’ and ‘late’ deaths. Mortality compression was quantified and compared between income quartiles.

Results

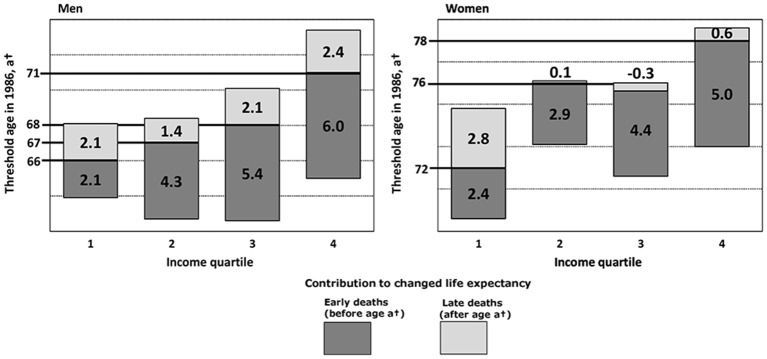

Since 1986, male life expectancy increased by 4.2 years for the lowest income quartile and by 8.4 years for the highest income quartile. The clear compression of mortality apparent in the highest income quartile did not occur for the lowest income quartile. Premature and late deaths accounted both by 2.1 years of the increase in life expectancy in the lowest income quartile and by 6.0 and 2.4 years, respectively, in the highest income quartile. Life expectancy increased by 5.2 years among women in the lowest income quartile, 2.4 years due to premature deaths and 2.8 years due to late deaths. The gain in life expectancy among women in the highest income quartile of 5.6 years was distributed by 5.0 and 0.6 years due to premature and late deaths, respectively.

Conclusion

The study demonstrates that the increasing social gap in mortality appears differently in the change of the age-at-death distribution. Thus, no compression of mortality was seen in the lowest income quartile. The results do not provide support for a uniformly extension of pension age for all.

Keywords: Compression of mortality, income, life disparity, life expectancy, life table, lifespan, social inequality

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The strength of the study is that it was based on register data for the entire Danish population with high quality data on mortality and income.

Because information on education was not available for the elderly during the entire period equivalised disposal income was used as an indicator for socioeconomic position.

Individual income was defined as equivalised disposable income adjusting for different consumption possibilities depending on household size and constitution.

Results were validated by use of lagged income to adjust for a possible risk of income decline close to death.

Introduction

For decades the populations in high-income countries have experienced decreasing mortality in young ages and a compression of old-age mortality. The reduction in infant mortality, the low young age mortality, the shift to the right of the age-at-death distribution and a concentration into a shorter age interval around the modal age of adult deaths becomes visible in the age-at-death distribution and an increasingly flatter course of the survival curve with a steeper drop at advanced ages. This is what characterises the compression of mortality or the rectangularisation of the survival curve.1–5 Several methods and measures of the phenomenon have been explored by demographers, in particular with focus on ageing and old-age mortality.5–15

Keyfitz introduced the entropy measure which is related to life disparity that measures the ‘average years of life lost to death’ or ‘the average remaining life expectancy at death’.16 17 Other indices of lifespan variation have been defined but all measures are highly correlated with each other.18 19 It has been shown that high life expectancy is associated with low lifespan dispersion3 14 and that this correlation is due to progress in reducing premature mortality.18

Some studies have investigated the relation between life expectancy and lifespan variation by socioeconomic position,10 14 20–22 but only a few studies have examined whether lifespan variation follow different trends. In Finland, life expectancy increased among manual workers and persons in lower and upper non-manual occupations, but lifespan variation developed differently between the occupational classes. Thus, manual workers had stagnating lifespan variation during almost 40 years while the higher occupational groups experienced mortality compression.20 In the USA, educational disparities in life expectancy at age 25 years increased among both genders in all ethnic groups from 1990 to 2010.21 Among non-Hispanic whites with <12 years of schooling life expectancy even declined. Lifespan variation changed differently between educational levels and increased among non-Hispanic white men and women with <13 years of education.21

The social gap in life expectancy in Denmark has widened since the mid-1980s. In particular, death rates in the age group 50–70 years developed unfavourably for the lowest income and educational quartiles of the Danish population.23 The overall conclusion from other recent studies is that social inequality in life expectancy has either increased or flattened out over the past several decades in high-income countries.24–34 The mechanisms behind social inequality in health and mortality are complex. Material and non-material resources are unevenly distributed between subpopulations. People with more resources have ready access to attractive living and working conditions and healthier lifestyle. Growing imbalance of resources between social classes increases health disparity.

For many years, the Danish labour market has been characterised by three elements that together comprise the triangle of flexicurity, that is, flexible rules for employers to hiring and firing, guarantee of a relative high level of unemployment benefits and an active labour market policy. The aim is to ensure employers a flexible labour force while ensuring employees a safety net including unemployment and other social benefit systems (unemployment benefit, social cash-benefit, sickness absence benefit and disability pension). However, due to public sector cutbacks, the Danish universal welfare system is under pressure. Recent labour market reforms implemented a shorter duration for receiving unemployment benefits, lower means-tested benefits and phasing out early retirement pensions, which were originally introduced in 1979 for the benefit of worn-out workers. Furthermore, eligibility for receiving state (old age) pension has since 2011 been adjusted so that it follows the projected increase in life expectancy.

More insight into social differentials in the distribution of age at death may assist policy making if the society is concerned about social inequality in mortality. Thus, the knowledge of lifespan disparity by socioeconomic position might give rise to new thinking on social and health promotion policies. Furthermore, a reason for studying social inequality of adult mortality and lifespan variation is to question the justification of a uniform pension age for all despite socioeconomic position. The aim of the study was to investigate and quantify how changes in mortality patterns differ between subpopulations grouped into quartiles of equivalised disposable income. Thus, life expectancy growth since 1986, life disparity and threshold age, that separates ‘early’ and ‘late’ deaths were estimated and compared between income quartiles.

Materials and methods

The study was based on register data for the entire Danish population. Income data from the Danish Tax and Customs Administration for all citizens and information on education from the Ministry of Education is stored at Statistics Denmark and updated annually. Population data and data on deaths are systematically collected at Statistics Denmark and were linked at the individual level by unique personal identification number assigned to all citizens. Individual income was based on equivalised disposable income that takes into account that consumption possibilities depend on household size and constitution. Thus, equivalised disposable income was defined using the Eurostat definition and calculated as the total household income after tax and other deductions that is available for spending and saving and divided by the number of ‘equivalent adults’ reflecting the size and the age composition of the family/household (http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Glossary:Equivalised_disposable_income). For every calendar year (combination of two consecutive years), social grouping was established by dividing each individual at any age in income quartiles and life tables were constructed for each quartile.

Because results shown for current income do not reflect a possible income reduction close to death, rates were also calculated on the basis of income 5 years previously. Furthermore, death rates in 2014 for ages 30–90 years by educational quartiles (based on prescribed length of education in months) were calculated as a supplement to compare the mortality patterns when based on income and education, respectively. However, because of lack of information on education among the elderly in previous calendar years only results for 2014 are presented.

Life disparity, e†, is a measure of how much lifespan differs between individuals. Life disparity at age a is defined as the average number of life years lost due to death among survivors to age a:

where d, l and e are the usual life table functions. Alternatively, e†(a) can be interpreted as the average remaining life expectancy at death conditional on survival to age a. Zhang and Vaupel introduced the threshold age, a†, defined as the (unique) solution to the equation

where H is the cumulative hazard function, and have shown that a† separates ‘early’ or ‘premature deaths’ and ‘late deaths’ in the sense that saving lives at ‘early’ ages, that is postponing deaths before age a† (premature deaths), reduces life disparity, that is, compresses lifespan variation, while deaths after that age expand the disparity.35 Furthermore, the increasing life expectancy can be decomposed by age to capture contributions of premature and late life mortality components by the formula:

where , and μ(a,t) denotes the age-specific hazard of death at time t.35 The results from the decomposition of life expectancy change are presented for each income quartile.

Results

A cross-tabulation of educational level (according to the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) groups: 1+2 (low), 3+4 (medium) and 5+6 (high)) and income quartile for the Danish population aged 30 years and older in 2014 is presented in table 1. Data for citizens younger than 30 years are omitted to ensure that educational attainment has been completed. Furthermore, no information on education is available for people over 90 years of age. Figure 1 demonstrates the strong correlation between education and income among Danes between 30 and 90 years in 2014.

Table 1.

Number of citizens aged 30 years and over by educational level and equivalised disposable income quartile in 2014∗

| Educational level (ISCED) | Equivalised disposable income quartile | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | ||

| Men | High (5–6) | 52 687 | 69 932 | 124 025 | 225 237 |

| Medium (3–4) | 180 538 | 225 971 | 221 617 | 161 901 | |

| Low (1–2) | 168 029 | 128 555 | 84 078 | 42 676 | |

| Unknown | 37 042 | 13 857 | 8603 | 8492 | |

| All | 438 295 | 438 314 | 438 323 | 438 305 | |

| Women | High (5–6) | 70 420 | 109 596 | 161 549 | 240 323 |

| Medium (3–4) | 156 495 | 184 970 | 185 172 | 152 616 | |

| Low (1–2) | 199 798 | 152 287 | 104 032 | 56 830 | |

| Unknown | 33 485 | 13 365 | 9474 | 10 435 | |

| All | 460 197 | 460 217 | 460 226 | 460 204 | |

*Average numbers of the 2013 and 2014 population.

ISCED, International Standard Classification of Education.

Figure 1.

The Danish population aged 30–90 years by education and income quartile in 2014. ISCED, International Standard Classification of Education.

In 1986, life expectancy among men in the lowest income quartile was 69.1 years and increased to 73.3 years in 2014. For the highest income quartile, life expectancy increased from 74.6 to 83.0 years. The income differentials in life expectancy increase were less distinct for women as it increased from 74.8 to 80.0 years among women in the lowest income quartile and from 80.1 to 85.7 years in the highest income quartile.

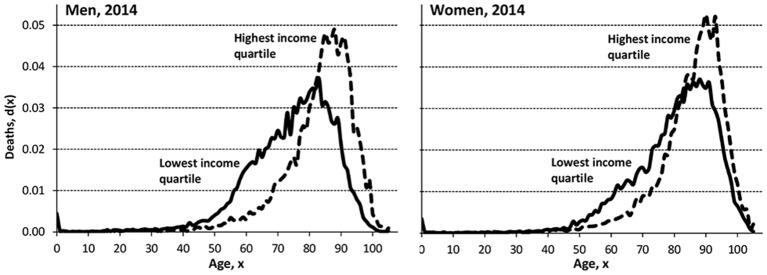

The online supplementary data 1 depicts the changes in the shapes of the distribution of age at death from 1986 to 2014 by gender and income quartile and the different change in the lowest and the highest income quartiles is shown in figure 2. It is evident that people in the highest income quartile experienced a clear compression of mortality while this was not the case for the lowest income quartile. Although the 5-year difference in the modal age at death increased by 5 years for men both in the lowest and the highest income quartiles, life disparity decreased from 11.4 to 8.5 years in the highest income quartile but remained unchanged at 12.0 years for the lowest income quartile (figure 3). For women, the modal age at death differed by 7 years between the lowest and highest income quartiles in 1986, but this difference narrowed and in 2014 the modal age at death was 91 years for both quartiles (figure 2). Life disparity decreased from 10.9 to 8.2 years among women in the highest income quartile, while it increased slightly from 10.3 to 11.0 years in the lowest income quartile. Life disparity decreased for all except the lowest income quartile (figure 3).

Figure 2.

Life table age-at-death distributions in 1986 and 2014 in the lowest and the highest income quartiles.

Figure 3.

Life disparities by gender and income quartile, Denmark 1986–2014.

bmjopen-2016-014489supp001.jpg (528.7KB, jpg)

During the period 1986–2014, the threshold age increased by 3 years for men in the lowest income quartile and by 8–10 years for the higher income quartiles. Among women the increase varied between 2 and 5 years. Decomposing the increase in male life expectancy by the contribution of premature and late mortality components separated by the threshold age in 1986 reveals that premature and late deaths accounted for 2.1 and 2.1 years in the lowest income quartile and by 6.0 and 2.4 years, respectively, in the highest income quartile (figure 4). The gain in life expectancy for women was distributed by 2.4 years due to premature deaths and 2.8 years due to late deaths in the lowest income quartile and by 5.0 and 0.6 years, respectively, in the highest income quartile. From figure 4 it appears that the compression of mortality increased by income, as the contribution of early or premature deaths to the growing life expectancy increased by income.

Figure 4.

Contributions of early and late life mortality to life expectancy increase from 1986 to 2014 by gender and income quartile.

In 2014, the most social vulnerable group defined as people in the lowest income quartile and with the lowest level of education (ISCED 1+2) comprised approximately 11% of the population aged 30 years and older (10.4% of the men and 11.6% of the women, figure 1). The most advantaged people in the highest income quartile and with the highest level of education (ISCED 5+6) comprised a little more than 13%. Life expectancy at age 30 years differed between these two groups by 12.0 years for men and 7.3 years for women. From figure 5 it appears that low educational attainment for men with low income was strongly associated with high risk of premature death.

Figure 5.

Life expectancy at age 30 years in 2014 by educational level and income quartile. ISCED, International Standard Classification of Education.

Due to the eligibility for receiving state (old age) pension and other welfare services in Denmark, the risk of appreciable reduction of income owing to ill-health or disability is low. This is reflected in figure 6, which presents the distribution of age at death in 2014 in the lowest and highest income quartiles using information on income from 2009. Almost identical patterns of mortality for men and women in 2014 recurred as shown in figure 2. Finally, online supplementary data 2 in the appendix shows similar social disparity in mortality patterns in 2014 when socioeconomic position divided into income quartiles was compared with educational quartiles, although the results call special attention to men with low income.

Figure 6.

Life table age-at-death distributions in 2014 in the lowest and the highest income quartiles lagged by 5 years.

bmjopen-2016-014489supp002.jpg (378.5KB, jpg)

Discussion

The study showed marked differences in the changes of life expectancy and disparity between income quartiles. For men in the lowest income quartile life expectancy increased by 4.2 years, whereas it increased twice as much in the highest income quartile, 8.4 years. The analogous increases for women were 5.2 and 5.6 years, respectively. No decrease in life disparity during the last 28 years was seen among men and women in the lowest income quartile while life disparity decreased by approximately 3 years in the two highest income quartiles and somewhat less in the next lowest quartile. The equal increase by 5 years in modal age at death for men in the lowest and highest income quartiles indicates that modal age at death is insufficient for catching different patterns of mortality change. In addition, to estimate the shifting to the right of the age-at-death distribution we need to determine whether mortality is compressed around the modal age at death. Changes in life disparity and threshold age along with life expectancy trends are informative in this respect. The results demonstrate a clear compression of mortality among the richest 25% of the Danish population while a similar shift to the right of the age-at-death distribution did not characterise the change in the shape of the survival curve for the poorest 25% of the population. The middle income quartiles experienced compression of mortality but less than in the highest income quartile.

The results were based on current income and did not take into account that potentially lethal disease may cause income reduction. However, the robustness of results with regard to whether income was chosen to be current or lagged was validated and no noticeable change was seen when using data on income 5 years before. This is due to very modest changes in disposal income in the case of illness because of the high degree of economic security provided by the welfare system. Educational level is obviously an alternative measure of socioeconomic position. But no information among the elderly was available for the entire period and as most deaths occur in older ages it would not be possible to investigate trends in the age-at-death distribution by educational level. It was, however, possible to make calculations by educational quartiles in 2014 for the age interval 30–90 years and similar mortality patterns were found for educational and income quartiles (see online supplementary data 2).

Although the classification of socioeconomic position differs, the overall results of this study are in agreement with results from a Finish study on trends in life disparity by occupational class.20 Both studies demonstrate stagnation in lifespan variation among socially disadvantaged people and mortality compression among people in more favourable social positions. Recent studies of trends in mortality in the USA found widening disparities in life expectancy from 1990 to 2010.21 31 Most dramatic was a decline in life expectancy at age 25 years among the non-Hispanic white, least-educated, in particular women.21 Furthermore, lifespan variation declined for those with higher levels of educational level but increased for non-Hispanic white women with low education.21 While among the 25% most socially disadvantaged Danish women life expectancy increased (almost as much as the 25% most advantaged women), the lifespan variation among women in the most disadvantaged positions in both countries increased.

In general, trend studies on social inequality in life expectancy indicate widening social gaps. In Finland, the difference in life expectancy at age 35 years between the lowest and highest income quintile increased by 5.1 and 2.9 years for men and women, respectively, from 1988 to 2007.25 Life expectancy difference at age 35 years between Norwegians with tertiary and primary education categories widened 5.3 and 3.2 years for men and women, respectively, during the period 1961–2009.26 These results are similar to the findings in Denmark, except when comparing Finnish and Danish women, as the difference in Denmark between the lowest and highest income quartile in life expectancy at age 35 years increased by 5.0 years for men but only by 0.6 years for women during the period 1986–2014 (data not shown). The widening gap between Danes aged 30 years with primary and tertiary education was 1.6 and 1.0 years for men and women during a period half as long as in the Norwegian study.23 26 In Belgium, the estimated increase from 1991 to 2004 in life expectancy between those aged 25 years with primary and tertiary education was 0.9 and 1.2 years for men and women, respectively.24 In England and Wales, the largest gains in life expectancy at age 65 years over the last 30 years were to the higher managerial and professional class for men and to the intermediate class for women.27 A comparative study of lifespan variation between three educational groups found a clear social gradient in the average lifespan and lifespan variation in 10 European countries estimated in calendar periods before and close to 2000.30 But trends in social disparities were not investigated and the results cannot be compared with the results from the present study. A study from the USA found that life expectancy between 2001 and 2014 increased by 2.3 and 2.9 years for the richest 5% men and women, respectively, but less than half a year among the poorest 5% of the population.29 The growing gap in life expectancy by income in the USA also emerges from a comprehensive report from the National Academies of Sciences.28 Other studies from the USA investigated trends in educational differences in mortality and life expectancy and documented a widening gap between educational groups and an alarming development for non-Hispanic white women.21 31–34 In spite of increasing social inequality in life expectancy for Danish women, the trends were less significant than for the US women-still life expectancy did not decrease for Danish women in the lowest educational or income quartile.

Early retirement pension, a welfare arrangement allowing Danes to leave the labour market before pension age, was launched in 1979 for the benefit of the worn-out workers. Since then, early retirement pension was expanded to all age eligible wage-earners, but was abolished in 2011 for future, younger labour market generations. In Denmark, the act on state (old age) pension has been adjusted to take the projected increasing average life expectancy into account regardless of social differentials in worn-out and expected remaining lifetime after leaving the labour market. Increasing socioeconomic gap in expected lifetime in good health36 37 and the marked increasing social inequality in life expectancy and disparity documented in this study may contribute to qualify the political debate on whether it would be fair for the pension age to differ between socioeconomic positions, for instance, by reflecting how long people have been engaged in active employment. Recently, Germany decided to determine pension age following this principle. What is most important, however, is to prevent diseases and early mortality in the low-income groups, which would also contribute to reducing social inequality in life expectancy.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: HB-H initiated the study, undertook the analysis and wrote the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency and no further ethical approval is required regarding register-based research in Denmark. The data set was stored at Statistics Denmark and was available by remote online access in an anonymous form.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data sources are register information established using the unique personal identification number assigned to all citizens in Denmark. Thus, data on income and death were linked at the individual level. Due to data security and Danish legislation no data are available.

References

- 1.Manton KG, Tolley HD. Rectangularization of the survival curve: implications of an ill-posed question. J Aging Health 1991;3:172–93. 10.1177/089826439100300204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nusselder WJ, Mackenbach JP. Rectangularization of the survival curve in the Netherlands, 1950-1992. Gerontologist 1996;36:773–82. 10.1093/geront/36.6.773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wilmoth JR, Horiuchi S. Rectangularization revisited: variability of age at death within human populations. Demography 1999;36:475–95. 10.2307/2648085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kannisto V. Measuring the compression of mortality. Demogr Res 2000;3:[29]p 10.4054/DemRes.2000.3.6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Canudas-Romo V. The modal age at death and the shifting mortality hypothesis. Demogr Res 2008;19:1179–204. 10.4054/DemRes.2008.19.30 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vaupel JW. How change in age-specific mortality affects life expectancy. Popul Stud 1986;40:147–57. 10.1080/0032472031000141896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Manton KG. Dynamic paradigms for human mortality and aging. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 1999;54:B247–54. 10.1093/gerona/54.6.B247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kannisto V. Mode and dispersion of the length of life. Population 2001;13:159–72. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robine JM. Redefining the stages of the epidemiological transition by a study of the dispersion of life spans: the case of France. Population 2001;13:173–94. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edwards RD, Tuljapurkar S. Inequality in life spans and a new perspective on mortality convergence across industrialized countries. Popul Dev Rev 2005;31:645–74. 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2005.00092.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bongaarts J. Trends in senescent life expectancy. Popul Stud 2009;63:203–13. 10.1080/00324720903165456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thatcher AR, Cheung SL, Horiuchi S, et al. . The compression of deaths above the mode. Demogr Res 2010;22:505–38. 10.4054/DemRes.2010.22.17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ouellette N, Bourbeau R. Changes in the age-at-death distribution in four low mortality countries: a nonparametric approach. Demogr Res 2011;25:595–628. 10.4054/DemRes.2011.25.19 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shkolnikov VM, Andreev EM, Zhang Z, et al. . Losses of expected lifetime in the United States and other developed countries: methods and empirical analyses. Demography 2011;48:211–39. 10.1007/s13524-011-0015-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Horiuchi S, Ouellette N, Cheung SLK, et al. . Modal age at death: lifespan indicator in the era of longevity extension. Vienna Yearb Popul Res 2013;11:37–69. 10.1553/populationyearbook2013s37 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keyfitz N. Applied Mathematical Demography. New York: John Wiley, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vaupel JW, Romo VC. Decomposing change in life expectancy: a bouquet of formulas in honor of Nathan Keyfitz’s 90th birthday. Demography 2003;40:201–16. 10.1353/dem.2003.0018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vaupel JW, Zhang Z, van Raalte AA. Life expectancy and disparity: an international comparison of life table data. BMJ Open 2011;1:e000128 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van Raalte AA, Caswell H. Perturbation analysis of indices of lifespan variability. Demography 2013;50:1615–40. 10.1007/s13524-013-0223-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van Raalte AA, Martikainen P, Myrskylä M. Lifespan variation by occupational class: compression or stagnation over time? Demography 2014;51:73–95. 10.1007/s13524-013-0253-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sasson I. Trends in Life expectancy and lifespan variation by educational attainment: United States, 1990-2010. Demography 2016;53:269–93. 10.1007/s13524-015-0453-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brown DC, Hayward MD, Montez JK, et al. . The significance of education for mortality compression in the United States. Demography 2012;49:819–40. 10.1007/s13524-012-0104-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brønnum-Hansen H, Baadsgaard M. Widening social inequality in life expectancy in Denmark. A register-based study on social composition and mortality trends for the Danish population. BMC Public Health 2012;12:994 10.1186/1471-2458-12-994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deboosere P, Gadeyne S, Van Oyen H. The 1991–2004 evolution in life expectancy by educational level in Belgium based on linked census and population register data. Eur J popul 2009;25:175–96. 10.1007/s10680-008-9167-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tarkiainen L, Martikainen P, Laaksonen M, et al. . Trends in life expectancy by income from 1988 to 2007: decomposition by age and cause of death. J Epidemiol Community Health 2012;66:573–8. 10.1136/jech.2010.123182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steingrímsdóttir OA, Næss Ø, Moe JO, et al. . Trends in life expectancy by education in Norway 1961-2009. Eur J Epidemiol 2012;27:163–71. 10.1007/s10654-012-9663-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Office for National Statistics. Statistical bulletin. Trend in life expectancy at birth and at age 65 by socio-economic position based on the National Statistics Socio-economic classification, England and Wales: 1982—1986 to 2007—2011. Estimates of life expectancy by personal socioeconomic position using the national statistics socio-economic classification based on occupation. 2015. http://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/lifeexpectancies/bulletins/trendinlifeexpectancyatbirthandatage65bysocioeconomicpositionbasedonthenationalstatisticssocioeconomicclassificationenglandandwales/2015-10-21/ (accessed 21 Mar 2017).

- 28.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. The growing gap in Life Expectancy by Income: implications for Federal Programs and Policy responses. Committee on the Long-Run Macroeconomic effects of the Aging U.S. Population-Phase II. Committee on Population, Division of Behavioral and Social Sciences and Education. Board on Mathematical Sciences and their applications, Division on Engineering and Physical Sciences. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2015. http://www.nap.edu/catalog/19015/the-growing-gap-in-life-expectancy-by-income-implications-for/ (accessed 21 March 2017). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chetty R, Stepner M, Abraham S, et al. . The association between income and life expectancy in the United States, 2001-2014. JAMA 2016;315:1750–66. 10.1001/jama.2016.4226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Raalte AA, Kunst AE, Deboosere P, et al. . More variation in lifespan in lower educated groups: evidence from 10 European countries. Int J Epidemiol 2011;40:1703–14. 10.1093/ije/dyr146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Case A, Deaton A. Rising morbidity and mortality in midlife among white non-Hispanic Americans in the 21st century. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2015;112:15078–83. 10.1073/pnas.1518393112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Meara ER, Richards S, Cutler DM. The gap gets bigger: changes in mortality and life expectancy, by education, 1981-2000. Health Aff 2008;27:350–60. 10.1377/hlthaff.27.2.350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sasson I. Diverging trends in cause-specific mortality and life years lost by educational attainment: evidence from United States vital statistics data, 1990-2010. PLoS One 2016;11:e0163412 10.1371/journal.pone.0163412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Olshansky SJ, Antonucci T, Berkman L, et al. . Differences in life expectancy due to race and educational differences are widening, and many may not catch up. Health Aff 2012;31:1803–13. 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang Z, Vaupel J. The age separating early deaths from late deaths. Demogr Res 2009;20:721–30. 10.4054/DemRes.2009.20.29 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brønnum-Hansen H, Baadsgaard M. Increase in social inequality in health expectancy in Denmark. Scand J Public Health 2008;36:44–51. 10.1177/1403494807085193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brønnum-Hansen H, Eriksen ML, Andersen-Ranberg K, et al. . Persistent social inequality in life expectancy and disability-free life expectancy-outlook for differential pension age in Denmark? Scand J Pub Health. 2017. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-014489supp001.jpg (528.7KB, jpg)

bmjopen-2016-014489supp002.jpg (378.5KB, jpg)