Abstract

Objectives

The aim of this research is to evaluate the relative cost-effectiveness of functional and anatomical strategies for diagnosing stable coronary artery disease (CAD), using exercise (Ex)-ECG, stress echocardiogram (ECHO), single-photon emission CT (SPECT), coronary CT angiography (CTA) or stress cardiacmagnetic resonance (C-MRI).

Setting

Decision-analytical model, comparing strategies of sequential tests for evaluating patients with possible stable angina in low, intermediate and high pretest probability of CAD, from the perspective of a developing nation’s public healthcare system.

Participants

Hypothetical cohort of patients with pretest probability of CAD between 20% and 70%.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

The primary outcome is cost per correct diagnosis of CAD. Proportion of false-positive or false-negative tests and number of unnecessary tests performed were also evaluated.

Results

Strategies using Ex-ECG as initial test were the least costly alternatives but generated more frequent false-positive initial tests and false-negative final diagnosis. Strategies based on CTA or ECHO as initial test were the most attractive and resulted in similar cost-effectiveness ratios (I$ 286 and I$ 305 per correct diagnosis, respectively). A strategy based on C-MRI was highly effective for diagnosing stable CAD, but its high cost resulted in unfavourable incremental cost-effectiveness (ICER) in moderate-risk and high-risk scenarios. Non-invasive strategies based on SPECT have been dominated.

Conclusions

An anatomical diagnostic strategy based on CTA is a cost-effective option for CAD diagnosis. Functional strategies performed equally well when based on ECHO. C-MRI yielded acceptable ICER only at low pretest probability, and SPECT was not cost-effective in our analysis.

Keywords: cost-benefit analysis, coronary disease, diagnosis, cardiovascular imaging

Strengths and limitations of this study.

There is no evidence that diagnostic test selection impacts cardiovascular event rates in stable coronary artery disease (CAD), and economic results may help guide choice among tests.

Our results show that incorporating coronary CT into the Brazilian Public Health System would add a cost-effective option for CAD diagnosis.

Among currently available technologies, the demonstration that stress echocardiography is more cost-effective than single-photon emission CT from this perspective may improve public resource allocation.

Cost-effectiveness results are useful to establish the ‘standard’ test for routine use, but flexibility in the choice among tests is still important, allowing physicians to select the best strategy for each particular case.

Introduction

Proper evaluation and diagnosis of coronary artery disease (CAD) is an essential part of public health strategies, given the importance of CAD in worldwide morbidity and mortality.1 When a patient presents with chest pain symptoms, his or her probability of having CAD can vary from less than 10% to more than 90%, depending on clinical and epidemiological characteristics.2 In the frequent cases with intermediate pretest probability, additional diagnostic tests can aid in clinical decision making and risk stratification.

Nowadays, several non-invasive tests for diagnosing CAD are widely available and have varying accuracy and costs. In Brazil, the Unified National Health System (Sistema Único de Saúde—SUS) currently reimburses exercise (Ex)-ECG, stress echocardiography (ECHO) and nuclear stress testing (SPECT) but not coronary CT angiography (CTA) or stress cardiac magnetic resonance (C-MRI).3

Recommendations for diagnostic test selection are not uniform in current practice guidelines,2 4 5 and in many, if not most occasions, the choice among these tests is determined primarily by individual physician preference and/or local availability. This may overlook several other important factors, from the efficacy of each test for a given pretest probability to economic issues such as added cost per diagnosis when an inexpensive test such as Ex-ECG is systematically replaced by a more expensive, although more accurate test such as SPECT.

Recently published data from a large randomised trial shows that anatomical testing using CTA results in similar long-term event rates as functional testing with Ex-ECG, SPECT or ECHO.6 These results should increment the importance of economic data in the decision-making process for test selection.

We aimed to compare the cost-effectiveness, measured as cost per correct diagnosis, of various functional and anatomical testing strategies for patients with suspected CAD. This information can supplement efficacy data in decision-makers’ choice of approved exams for health plans, and provide grounds for the development of nationwide protocols for the management of stable angina.

Methods

Model

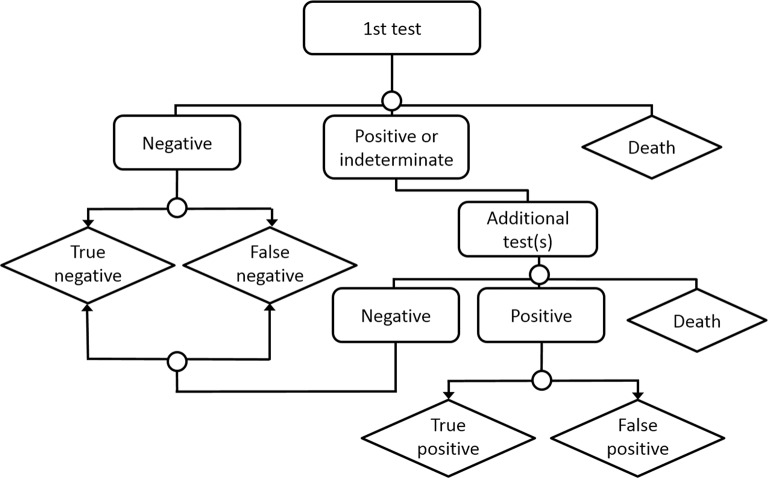

We built a decision-analytical model that compares different strategies for evaluating patients with possible stable angina from the public health system’s perspective. Figure 1 schematically depicts the model structure; a more detailed, technical depiction of the model structure is available in the online supplementary figure A. The model, developed in Treeage Pro 2013, is considered a hypothetical cohort of patients with pretest probability of CAD between 20% and 70%.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of model structure.

bmjopen-2016-012652supp001.pdf (567.6KB, pdf)

We defined eight functional strategies and three anatomical strategies based on clinically realistic sequences of tests (table 1); in each strategy, the patient undergoes an initial test, moving on to further testing in case of positive or indeterminate results. Negative results do not generate additional tests. Strategy 1, for example, begins with Ex-ECG as a first test. Patients with positive or indeterminate results undergo the second test, ECHO; if the second test is positive or indeterminate, patients move on to invasive coronary angiography (CA) as the final test. In scenarios with high pretest probability, we also considered strategies that use CA as first test, reserving non-invasive test for equivocal CA results, such as coronary lesions of unknown haemodynamic significance.

Table 1.

Test sequence in each modelled strategy

| First test | Second test | Third test | |

| Strat. 1 | Exercise ECG | Stress echocardiography | Coronary angiography |

| Strat. 2 | Exercise ECG | Coronary CT angiography | Coronary angiography |

| Strat. 3 | Exercise ECG | SPECT | Coronary angiography |

| Strat. 4 | Exercise ECG | Coronary angiography | |

| Strat. 5 | SPECT | Coronary angiography | |

| Strat. 6 | Stress echocardiography | Coronary angiography | |

| Strat. 7 | Stress echocardiography | Coronary CT angiography | Coronary angiography |

| Strat. 8 | Stress cardiac MRI | Coronary angiography | |

| Strat. 9 | Coronary CT angiography | Coronary angiography | |

| Strat. 10* | Coronary angiography | Stress echocardiography | |

| Strat. 11* | Coronary angiography | SPECT |

*Strategies 10 and 11, in which invasive coronary angiography is the first test, are only considered in scenarios with high pretest probability. SPECT, single-photon emission CT.

Outcomes

The model ends with a test result (positive or negative), potentially true or false depending on the accuracy of the tests, resulting in final costs per correct diagnosis. There is also a small risk of death due to test-related adverse events (table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of tests, range of values used in sensitivity analysis and costs

| Test | Sensitivity (%) (range) |

Specificity (%) (range) |

Indeterminate (%) |

Mortality (‰) |

Cost (I$) |

Sources |

| Ex-ECG | 65 (42–92) | 67 (43–83) | 18 | 0.05 | 16 | 3 16 17 |

| ECHO | 85 (83–87) | 77 (74–80) | 15 | 0.05 | 87 | 3 18 19 |

| SPECT | 87 (84–88) | 64 (60–76) | 6.9 | 0.05 | 419 | 3 18 19 |

| CTA | 88 (83–92) | 87 (80–92) | 2 | 0.01 | 101 | 3 20–22 |

| MRI | 89 (88–94) | 80 (75–87) | 5 | 0.01 | 200 | 3 19 23 |

| CA | 100 | 100 | 10 | 0.2 | 325 | Assumption3 4 24 |

CA, invasive coronary angiography; CTA, CT coronary angiogram; ECHO, stress echocardiogram; Ex-ECG, exercise ECG; SPECT, single-photon emission CT.

Data sources

After systematic review of previous studies of accuracy, we used available data from published meta-analyses of test performance and risks to populate the model (table 2).

Brazilian National Health System (Sistema Único de Saúde—SUS) 2013 reimbursement rates were the source of costs for diagnostic tests for currently reimbursed tests3; costs of CTA and MRI were estimated based on rates for currently reimbursed tests (chest CT and rest C-MRI), inflated proportionally to cost differences among these tests in the private sector7 (table 2).

All costs were converted from Brazilian real to international dollars (I$), using the World Bank’s latest available purchasing power parity conversion factor of 1.89.8

Assumptions

We assumed 100% sensitivity and specificity for CA, since it is the gold standard for diagnosing coronary artery disease. Another assumption was that for the last test in any strategy, whether it is CA (as in strategies 1–9) or a non-invasive test (as in strategies 10–11), the probability of indeterminate results is zero.

We assumed myocardial infarction (MI) as an example of serious investigation-related complication, and applied SUS data regarding average national costs for MI admissions in 2012, I$ 1670,3 as reference for cost of complications (including death).

Separate analyses were performed, with low (20%), medium (50%) and high (70%) pretest probabilities of CAD, corresponding to the range of pretest probability in which non-invasive tests are most useful, according to the American Heart Association’s guidelines on stable angina.2

Sensitivity analysis

Aiming to test the robustness of the model and the weight of individual parameters on results, during sensitivity analysis, we varied test accuracies and rates of complications and indeterminacy around their 95% CIs. Alternative costs of tests ranged from half the original values to double those values.

In addition to one-way and two-way sensitivity analyses, we performed probabilistic sensitivity analysis with 10 000 samples, with simultaneous variation of model parameters around their CIs. We used beta distributions for test accuracies and gamma distributions for costs.

Additionally, taking into account that in some situations, CA may be considered an unacceptable first test due to patient or physician preferences, we considered an alternative scenario excluding strategies that begin with CA (strategies 10 and 11).

Willingness to pay

There is no broadly accepted willingness-to-pay (WTP) threshold for additional costs per correct diagnosis. For results per quality-adjusted life years, the WHO recommends a WTP threshold between one and three times a nation’s gross domestic product (per capita for middle-income countries.9 For Brazil, these figures are I$ 11 700 to 35 200 per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY).

Since per-diagnosis results could be considered to be of a lower magnitude than per-QALY results, we did not make any assumption regarding lower limit of WTP but rather chose to describe the main findings.

Results

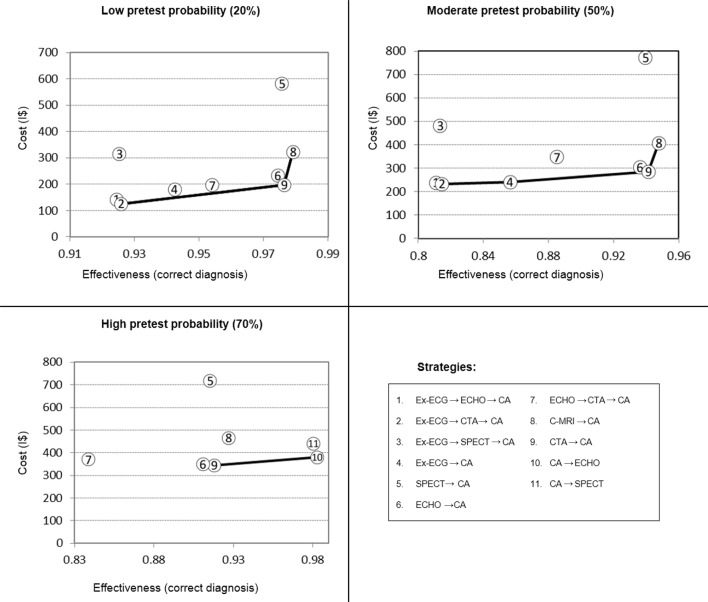

Table 3 shows average costs, accuracy and comparative cost-effectiveness results from testing a population with low (20%) to high (70%) pretest probability of CAD with each diagnostic strategy. In Figure 2, cost-effectiveness results for each pretest probability are illustrated, excluding dominated strategies.

Table 3.

Base-case results for different pretest probabilities. Dominated strategies not shown, except when significant uncertainty regarding dominance on sensitivity analysis

| Pretest probability | Strategy | Avg cost per patient (I$) | C-E (I$/diag) |

ICER (I$/diag) |

Accuracy (%) | FN (%) |

Deaths (%) | Invasive CA (%) | Negative invasive CA (%) |

| Low | 2 (Ex-ECG→CTA → CA) | 125 | 135 | - | 93 | 7.4 | 0.009 | 18 | 5 |

| 1 (Ex-ECG → ECHO → CA) | 141 | 153 | - | 92 | 7.6 | 0.012 | 25 | 12 | |

| 9 (CTA → CA) | 197 | 202 | 1420* | 98 | 2.4 | 0.007 | 29 | 12 | |

| 8 (C-MRI → CA) | 315 | 322 | 47 800† | 98 | 2.1 | 0.008 | 37 | 19 | |

| Moderate | 2 (Ex-ECG → CTA → CA) | 188 | 231 | - | 81 | 18.5 | 0.013 | 35 | 3 |

| 4 (Ex-ECG → CA) | 205 | 240 | 415‡ | 86 | 14.3 | 0.017 | 58 | 23 | |

| 9 (CTA → CA) | 269 | 286 | 750§ | 94 | 5.9 | 0.011 | 51 | 7 | |

| 6 (ECHO → CA) | 286 | 305 | - | 94 | 6.4 | 0.017 | 61 | 17 | |

| 8 (C-MRI → CA) | 385 | 407 | 17 800† | 95 | 5.2 | 0.012 | 57 | 12 | |

| High | 4 (Ex-ECG → CA) | 222 | 278 | - | 80 | 20.1 | 0.018 | 63 | 14 |

| 9 (CTA → CA) | 317 | 345 | 790§ | 92 | 8.2 | 0.014 | 66 | 4 | |

| 6 (ECHO → CA) | 320 | 351 | - | 91 | 8.9 | 0.019 | 71 | 10 | |

| 10 (CA → ECHO) | 373 | 381 | 273† | 98 | 1.7 | 0.02 | 100 | 30 |

*ICER vs strategy 1.

†ICER vs strategy 9.

‡ICER vs strategy 2.

§ICER vs strategy 4.

Avg, average; CA, invasive coronary angiography; C-E, cost-effectiveness; C-MRI, cardiac MRI; CTA, CT coronary angiogram; ECHO, stress echocardiogram; Ex-ECG, exercise ECG; FN, false-negative; ICER, incremental cost-effectiveness ratio.

Figure 2.

Base-case cost-effectiveness results for predefined risk categories. Strategies 1–4 excluded from high-probability analysis (see text for details). CA, invasive coronary angiography; CTA, CT coronary angiogram; ECHO, stress echocardiogram; Ex-ECG, exercise ECG; SPECT, single-photon emission CT.

Low pretest probability (20%)

With low probability of CAD, strategy 2 (Ex-ECG → CTA → CA) was the least costly strategy, with a mean cost per diagnosis of I$ 135 while retaining good overall performance (92.6% correct diagnosis, 5% invasive CA in patients without CAD). Upgrading to strategy 9 (CTA → CA) increases effectiveness to 97.6% of correct diagnosis, with mean cost per diagnosis I$ 200 and incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of I$ 1420. Substituting strategy 9 with strategy 8 (C-MRI → CA) modestly increases diagnostic accuracy to 97.9% but raises mean cost per diagnosis to I$ 320, resulting in a much higher ICER of I$ 47 800.

The other strategies were either absolutely or relatively dominated. However, strategy 1 (Ex-ECG → ECHO → CA) had accuracy results that were practically identical to strategy 2 (92.4% correct diagnosis), with mean cost per diagnosis only marginally higher, I$ 150.

Moderate pretest probability (50%)

In moderate CAD probability scenario, strategy 2 (Ex-ECG → CTA → CA) remained the least costly strategy, at I$ 230 per correct diagnosis; however, in this scenario, this strategy resulted in a relatively low overall accuracy of 81%, with over 18% false negative final diagnoses. Strategy 4 (Ex-ECG → CA) improves overall accuracy to 86%, with 14% false negative results and costs I$ 240 per correct diagnosis. Resulting in an ICER versus strategy 2 of I$ 415.

In this range of pretest probability, the strategy based on CTA coronary angiography as initial test (strategy 9) yields significantly better outcomes, with 94% overall accuracy. Mean cost per diagnosis is I$ 285, resulting in an ICER versus strategy 4 of I$ 750 per correct diagnosis. Strategy 8, based on C-MRI, raises accuracy to 95%, while increasing mean cost per diagnosis to I$ 410. ICER for strategy 8 versus strategy 9 is I$ 17 800 per correct diagnosis.

Remaining strategies have been dominated by strategies 2, 4, 9 and 10. Once again, it should be noted that strategy 6 (Echo → CA) yields accuracy results very close to the ones obtained with strategy 9 (93.6%) at a marginally higher mean cost per diagnosis of I$ 305.

High pretest probability (70%)

With a higher prevalence of CAD, strategies that involve two non-invasive tests before CA are dominated by strategy 4 (Ex-ECG → CA), which results in 80% correct identification at I$ 280 per diagnosis. However, in this range of CAD risk, strategy 4 results in 20% false-negative results, seriously hindering its usefulness in practice.

If strategies with false-negative rates above 20% (1-4) are excluded from analysis, strategy 9 (CTA → CA) emerges as an attractive option, with overall accuracy of 92% and mean cost per diagnosis of I$ 345. Strategy 6 (Echo → CA) results in practically identical effectiveness (91%) at a somewhat higher cost per diagnosis of I$ 400.

A strategy based on invasive CA as first test (strategy 10) results in 98% accuracy, mean cost per diagnosis I$ 346 and ICER I$ 273 versus strategy 9.

Sensitivity analysis, scenario analysis and radiation exposure

In one-way sensitivity analysis, the choice between CTA and ECHO-based strategies was sensitive to procedure costs and test sensitivity. For instance, in low probability scenarios, CTA dominates ECHO if it costs less than I$ 129, has higher cost and higher effectiveness with costs between I$ 129 and 182 and is extensively dominated by ECHO at higher costs. With high pretest probability, ECHO is the preferred non-invasive method if it costs up to I$ 56; and at its maximum price, ECHO is dominated by CTA.

Variation in cost and accuracy of other tests modified cost per diagnosis for each strategy but did not alter base-case results to the extent of changing preferred strategies.

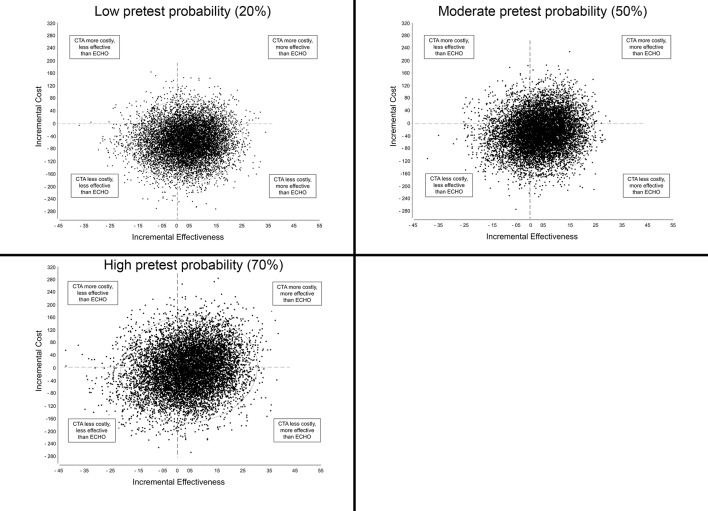

In probabilistic sensitivity analysis, there was significant overlap between CTA and ECHO in terms of cost-effectiveness, demonstrating a high level of uncertainty as to which of the two strategies would be preferred (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Scatterplot of incremental cost-effectiveness of strategy 9 (CTA-CA) versus strategy 6 (ECHO-CA). ECHO, stress echocardiogram; CTA, CT coronary angiogram; CA, invasive coronary angiography. Dotted line represents willingness-to-pay threshold; ellipse contains 95% of outputs.

In the alternative scenario that excludes CA as an initial test, even in the high pretest probability group, strategy 8, based on C-MRI as first test, becomes the strategy with highest accuracy, with an ICER versus strategy 9 (CTA → CA) slightly above $12 200 with 70% pretest probability.

Focusing on currently available imaging modalities, we performed two-way sensitivity analysis on the choice between ECHO-based and SPECT-based strategies, which showed ECHO-based strategies to be dominant across the defined spectrum of sensitivity analysis. SPECT-based strategies are preferred only if the cost of SPECT is no more than 10% higher than the cost of ECHO.

Average radiation dose per patient varied between 3.9 mSv for strategy 1 (Ex-ECG → ECHO → CA) and 16.4 mSv for strategy 5 (SPECT → CA). For strategy 9, based on CTA, mean exposure was 15.1 mSv, and for strategy 8, based on C-MRI, it was 5.7 mSv (see online supplementary table A).

Discussion

Significant interest has been placed on the choice between functional and anatomical strategies for CAD diagnosis. In the management of acute coronary syndrome, CTA outperformed functional testing in three clinical trials.10–12 However, in stable CAD, randomised data on the clinical impact of selecting a functional or anatomical strategy have only recently been published.

In the PROMISE trial,6 an anatomical strategy based on CTA as initial test resulted in similar clinical outcomes over 2 years when compared with functional testing. The CTA strategy, probably due to its high sensitivity, resulted in a lower rate of invasive CA with no evidence of CAD in the first 90 days. Coronary revascularisation was more frequent with CTA, but long-term clinical significance of this finding is uncertain.

This similar performance of anatomical and functional strategies should prompt physicians and decision makers to look beyond clinical outcomes in the selection of tests, taking into account information such as cost-effectiveness, resource use and environmental impact. Recent studies suggest CTA may be a cost-effective option in developed countries.13–15

In this study, we performed a cost-effectiveness analysis to assess currently available strategies for investigating chest pain in Brazil, and to compare them with new ones, that could become available on inclusion of CTA and C-MRI among reimbursed tests.

Our study showed that, from the economic perspective, the choice of functional test (Ex-ECG, ECHO, SPECT or C-MRI) influences whether a functional or anatomical strategy would be preferable.

The least costly diagnostic strategies are conservative ones, using Ex-ECG as a ‘gatekeeper’, and proceeding to a second round of non-invasive tests when results are positive. These low-cost strategies have the disadvantage of generating a larger number of false-positive initial tests, thus subjecting patients without CAD to additional tests. Furthermore, their performance deteriorates as pretest probability rises, so that at 70% pretest probability their false-negative rate is above 20%. Therefore, such strategies may be an option for constrained budgets or lack of alternatives, but only when pretest probability is low or moderate (≤50%).

As pretest probability increased, costs per correct (positive or negative) diagnosis becomes higher for strategies based on sequential tests, since positive initial tests are more frequent, leading to further testing in more patients. This is particularly true for conservative strategies that require two non-invasive tests before proceeding to invasive CA. Strategies based on CTA and ECHO as initial test, result in almost superimposable cost-effectiveness results. These strategies would increase accuracy, at an ICER versus Ex-ECG-based strategies well below I$ 11 909 per correct diagnosis. This makes them attractive options across the entire spectrum of pretest probabilities.

Diagnostic strategies based on C-MRI showed to be highly effective, but their relatively high (estimated) cost resulted in unfavourable ICERs in moderate-risk and high-risk scenarios. If C-MRI costs could be reduced to figures lower than I$ 200 estimated, it could become cost-effective enough to recommend for widespread implementation in SUS. Nonetheless, it is important to emphasise that, for this cost, availability and acquisition values were not taken into account.

Non-invasive strategies based on SPECT generated consistently unfavourable results due to the high cost of SPECT when compared with other non-invasive tests and have been dominated in all scenarios. In addition, radiation-related risks were not included in our short-term model because potential effects of radiation exposure take more than a decade to manifest. Still, this could be an additional cause for concern regarding widespread use of tests such as SPECT and CTA.

Our study’s main limitation is that, since public health system does not reimburse CTA and C-MRI, we had to estimate procedure costs from private practice. In case of incorporation of these tests into the public system, actual reimbursement values may vary, although we did not expect significant discrepancy based on previous cases. Still, our results were robust even when we halved or doubled the value of our initial cost estimate.

Current practice in Brazil usually prioritises SPECT-based over ECHO-based strategies for diagnosing CAD. Based on the national database, in the year 2013, the Brazilian public health system reimbursed over 1 00 000 SPECT tests and less than 19 000 ECHO tests for outpatients.3 Our results suggest that ECHO-based strategies should be more widely employed in SUS, especially considering their absence of radiation and low costs for implementation and maintenance.

Updating reimbursement values for ECHO may stimulate the availability of this test in the public health system, and seems justified, since our sensitivity analysis showed that ECHO would remain more cost-effective than SPECT even with costs up to four times higher than current rates.

Conclusions

For the diagnosis of stable CAD, strategies based on exercise ECG are the least expensive, but their lower effectiveness means they are best suited for constrained budgets, and only when pretest probability is low or moderate.

Regarding technologies that are currently available in SUS, stress echocardiography is more cost-effective than SPECT and should generally be preferred if available.

Incorporation of coronary CT into SUS would add a cost-effective option for CAD diagnosis. Stress C-MRI yielded acceptable ICER only at low pretest probability. Our results suggest that the immediate incorporation of coronary CT into SUS is advisable if actual test costs can match our estimated cost of I$ 100 per test. Incorporation of stress C-MRI should be considered only if its costs can be reduced to values significantly lower than our estimate of I$ 200.

bmjopen-2016-012652supp002.pdf (124.8KB, pdf)

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: EGB and CAP designed thestudy, with input from LEPR and SFS. EGB and SFS collected thedata. EGB analysed the datawith input from all authors. All authors contributed to theinterpretation of the results andwrite up for publication.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Correction notice: This article has been corrected since it published. Figure 1 has been replaced with the correct figure for this paper.

References

- 1.Global Burden of Disease Study 2013 Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 301 acute and chronic diseases and injuries in 188 countries, 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2013. Lancet 2015;386:743–800. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60692-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fihn SD, Gardin JM, Abrams J, et al. . ACCF/AHA/ACP/AATS/PCNA/SCAI/STS guideline for the diagnosis and management of patients with stable ischemic heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines, and the American College of Physicians, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Circulation 2012;2012:e354–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ministério Da Saúde do Brasil. Datasus, 2013. http://www.datasus.gov.br.

- 4.Cooper A, Timmis A, Skinner J. Assessment of recent onset chest pain or discomfort of suspected cardiac origin: summary of NICE guidance. BMJ 2010;340:c1118 10.1136/bmj.c1118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Montalescot G, Sechtem U, Achenbach S, et al. . 2013 ESC guidelines on the management of stable coronary artery disease: the Task Force on the management of stable coronary artery disease of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J 2013;34:2949–3003. 10.1093/eurheartj/eht296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Douglas PS, Hoffmann U, Patel MR, et al. . Outcomes of anatomical versus functional testing for coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med 2015;372:1291–300. 10.1056/NEJMoa1415516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Associação Médica Brasileira. Classificação brasileira hierarquizada de procedimentos médicos (CBHPM. São Paulo: Associação Médica Brasileira, 2013:206. [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Bank. World development indicators & global development finance. 2012. http://databank.worldbank.org.

- 9.WHO Commission on MacroEconomics and Health. Macroeconomics and health: investing in health for economic development Report of the commission on macroeconomics and health. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2001:200. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cury RC, Budoff M, Taylor AJ. Coronary CT angiography versus standard of care for assessment of chest pain in the emergency department. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr 2013;7:79–82. 10.1016/j.jcct.2013.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoffmann U, Truong QA, Schoenfeld DA, et al. . Coronary CT angiography versus standard evaluation in acute chest pain. N Engl J Med 2012;367:299–308. 10.1056/NEJMoa1201161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldstein JA, Chinnaiyan KM, Abidov A, et al. . The CT-STAT (Coronary Computed Tomographic Angiography for Systematic Triage of Acute chest pain patients to treatment) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;58:1414–22. 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.03.068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Genders TS, Petersen SE, Pugliese F, et al. . The optimal imaging strategy for patients with stable chest pain: a cost-effectiveness analysis. Ann Intern Med 2015;162:474–84. 10.7326/M14-0027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nielsen LH, Olsen J, Markenvard J, et al. . Effects on costs of frontline diagnostic evaluation in patients suspected of angina: coronary computed tomography angiography vs. conventional ischaemia testing. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging 2013;14:449–55. 10.1093/ehjci/jes166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zeb I, Abbas N, Nasir K, et al. . Coronary computed tomography as a cost-effective test strategy for coronary artery disease assessment - a systematic review. Atherosclerosis 2014;234:426–35. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2014.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mowatt G, Vale L, Brazzelli M, et al. . Systematic review of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness, and economic evaluation, of myocardial perfusion scintigraphy for the diagnosis and management of angina and myocardial infarction. Health Technol Assess 2004;8:iii1–iv207. 10.3310/hta8300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patterson RE, Eisner RL, Horowitz SF. Comparison of cost-effectiveness and utility of exercise ECG, single photon emission computed tomography, positron emission tomography, and coronary angiography for diagnosis of coronary artery disease. Circulation 1995;91:54–65. 10.1161/01.CIR.91.1.54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fleischmann KE, Hunink MG, Kuntz KM, et al. . Exercise echocardiography or exercise SPECT imaging? A meta-analysis of diagnostic test performance. JAMA 1998;280:913–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Toronto Health Economics and Technology Assessment (THETA). Relative Cost-effectiveness of five Non-invasive cardiac imaging technologies for diagnosing coronary artery disease in Ontario. 2010. http://www.theta.utoronto.ca/papers/theta_report_007.pdf.

- 20.Arbab-Zadeh A, Miller JM, Rochitte CE, et al. . Diagnostic accuracy of computed tomography coronary angiography according to pre-test probability of coronary artery disease and severity of coronary arterial calcification. the CORE-64 (Coronary artery evaluation using 64-Row Multidetector Computed Tomography Angiography) International Multicenter Study. J Am Coll Cardiol 2012;59:379–87. 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.06.079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mowatt G, Cummins E, Waugh N, et al. . Systematic review of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of 64-slice or higher computed tomography angiography as an alternative to invasive coronary angiography in the investigation of coronary artery disease. Health Technol Assess 2008;12:iii–iv. ix-143 10.3310/hta12170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cooper A, Calvert N, Skinner J, et al. . Chest pain of recent onset: assessment and diagnosis of recent onset chest Pain or Discomfort of Suspected Cardiac Origin. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2010:393. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hamon M, Fau G, Née G, et al. . Meta-analysis of the diagnostic performance of stress perfusion cardiovascular magnetic resonance for detection of coronary artery disease. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2010;12:29 10.1186/1532-429X-12-29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patel MR, Peterson ED, Dai D, et al. . Low diagnostic yield of elective coronary angiography. N Engl J Med 2010;362:886–95. 10.1056/NEJMoa0907272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-012652supp001.pdf (567.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-012652supp002.pdf (124.8KB, pdf)