Abstract

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D). Although glycaemic control reduces microvascular complications, the effect of intensive treatment strategies or individual drugs on macrovascular diseases is still debated. RNA oxidation is associated with increased mortality in patients with T2D. Inspired by animal studies showing effect of a sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitor (empagliflozin) on oxidative stress and a recent trial evaluating empagliflozin that demonstrated improved cardiovascular outcomes in patients with T2D at high risk of cardiovascular events, we hypothesise that empagliflozin lowers oxidative stress.

Methods and analysis

In this randomised, double-blinded and placebo-controlled study, 34 adult males with T2D will be randomised (1:1) to empagliflozin or placebo once daily for 14 days as add-on to ongoing therapy. The primary endpoints will be changes in 24-hour urinary excretion of 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanosine (8-oxoGuo) and 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2’-deoxyguanosine (8-oxodG) determined before and after intervention (by ultra-performance liquid chromatography tandem mass-spectrometry). Additionally, fasting levels of malondialdehyde (MDA) will be determined in plasma before and after intervention (by high-performance liquid chromatography). Further, the plasma levels of iron, transferrin, transferrin-saturation, and ferritin are determined to correlate the iron metabolism to the markers of oxidative modifications.

Ethics and dissemination

The study protocol has been approved by the Regional Committee on Biomedical Research Ethics (approval number H-16017433), the Danish Medicines Agency, and the Danish Data Protection Agency, and will be carried out under the surveillance and guidance of the GCP unit at Bispebjerg Frederiksberg Hospital, University of Copenhagen in compliance with the ICH-GCP guidelines and in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The results of this study will be presented at national and international conferences, and submitted to a peer-reviewed international journal with authorship in accordance with Internation Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) Recommendations state.

Trial registration

Study name: EMPOX; Pre-results: clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02890745). Protocol version 5.1 - August, 2016.

Keywords: Diabetes Mellitus, Type 2; Empagliflozin; Oxidative modifications; Oxidative Nucleic Acid Modifications; 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2-deoxyguanosine; 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanosine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study will investigate the effect of empagliflozin on urinary excretion of 8-oxoGuo, since 8-oxoGuo is a prognostic biomarker for mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes (T2D).

The trial design will be randomised, double blinded and placebo controlled.

The methods for analysis of the outcomes are precise and reliable.

A limitation is that the study outcome is not mortality in a long-term follow-up, but a biomarker prognostic for mortality in patients with T2D.

Introduction

Diabetes is an increasing health issue affecting around 422 million people in the world, a doubling in prevalence since 1980.1 More than 90% have type 2 diabetes (T2D). Patients with T2D have increased risk of developing cardiovascular diseases.2

The treatment target and strategy of T2D are individualised based on disease complications and comorbidity, with glycaemic control as the major focus.3 Although glycaemic control reduces the risk of microvascular complications,4 the effect of intensive treatment strategies or individual drugs on macrovascular diseases is still debated.5–10

T2D is in general characterised as a metabolic disease with insulin resistance and defect insulin production.11 Additionally, increased oxidative nucleic acid modifications have been observed.12–14 Of particular importance, RNA oxidation measured by urinary excretion of 8-oxo-7,8-dihydriguanosiene (8-oxoGuo) has been shown to be associated with increased mortality in both newly diagnosed patients with T2D13 and in patients with a 6-year disease duration of T2D.14 However, still no drug treatments have been demonstrated to reduce urinary excretion of 8-oxoGuo.15–18

Empagliflozin is a selective sodium/glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT-2)-inhibitor that increases urinary excretion of glucose, and thereby improves glycaemia in patients with T2D.19 Recently, the cardiovascular outcome trial EMPA-REG-OUTCOME study demonstrated that empagliflozin added to standard care in doses of 10 or 25 mg once daily compared with placebo treatment reduces all-cause mortality and death from cardiovascular causes in patients with T2D and high-risk of cardiovascular disease.20 The effect of empagliflozin occurred fast, only 3 months after treatment initiation.21 The mode of action behind these effects of empagliflozin remains debated. Additional effects to empagliflozin treatment such as lowering blood pressure and increased diuresis have been suggested, but not confirmed as explanatory.22 23

Empagliflozin reduces multiple markers of oxidative modifications in rat models of type 1 diabetes.24 25 In addition, it has been reported that empagliflozin lowers 8-iso prostaglandin f2α (8-iso-PGF2α) (a marker of lipid peroxidation) in patients with T2D. However, the methodologyfor determining 8-iso-PGF2α, was not reported.26

Several biomarkers of oxidative modifications are proven potential clinical relevant for different diseases.27 Studies have demonstrated inconsistency between markers of oxidative modifications in different cellular compartments.13 14 28 Hereby, this study differentiates the effect of empagliflozin on three different cellular compartments.

Iron contributes to increased levels of oxidative modifications, and iron is hypothesised to be associated with development of diabetes.29 This study evaluates the correlation of iron, transferrin, transferrin saturation and ferritin with the markers of oxidative modifications.

Hypothesis and aims

We hypothesise that empagliflozin lowers oxidative nucleic acid modifications, measurable by urinary excretion of 8-oxoGuo and 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2’-deoxyguanosine (8-oxodG). Further, we evaluate if there is a compartmentalisation of oxidative modifications in the organism and within the cell by also measuring the effect of empagliflozin on lipid peroxidation by plasma levels of malondialdehyde (MDA).

In addition to our primary hypothesis, this study investigates whether iron, transferrin, transferrin saturation, and ferritin are correlated to the levels of oxidative modifications (8-oxoGuo, 8-oxodG, and MDA) in patients with T2D.

Study objectives

The primary objectives are 24-hour urinary excretion of 8-oxoGuo and 8-oxodG before and after treatment with empagliflozin compared with placebo as a measurement of whole-body RNA oxidation and DNA oxidation, respectively.30

The secondary objectives encompass the concentration of MDA in plasma before and after treatment with empagliflozin compared with placebo treatment as a measurement of lipid peroxidation.31

Further, this study determines the concentration of iron, transferrin, transferrin saturation, and ferritin before and after the intervention to confirm and further explore the association between the iron metabolism and oxidative modifications.

Methods and analysis

The protocol is developed in accordance with the Standard Protocol Items: Recommendations for Interventional Trials (SPIRIT) recommendation.32 33 The SPIRIT 2013 Checklist for this protocol is available as "supplementary data".

The trial is registered at http://clinicaltrials.gov (pre-results: NCT02890745). Important changes in the protocol will be registered at the website, and addressed to the Danish Medicines Agency and the Regional Committee on Biomedical Research Ethics.

Trial design and setting

The trial will be randomised, placebo controlled, and double blinded with two parallel groups.

Participants will be recruited from the diabetes outpatient clinic, Department of Medicine, Gentofte Hospital, University of Copenhagen, Hellerup, Denmark in relation to outpatient consultations. The recruitment continues until 34 participants have completed the trial successfully.

Eligibility of participants

Inclusion criteria

Male diagnosed with T2D

Age: 18–75 years

HbA1c: 6.5%–9.0%

Capable of understanding oral and written information

Caucasian

Exclusion criteria

Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) <60 mL/hour/1.73 m2

Currently receiving insulin treatment

Coronary artery bypass grafting, percutaneous coronary intervention, acute coronary syndrome, stroke, lung embolism, deep vein thrombosis or transitory cerebral ischaemia within 6 months

Genital infection within 14 days

Plasma alanine aminotransferase ≥3 times upper normal limit

Treatment with SGLT-2 inhibitor within 2 months

Hyperglycaemic symptoms

Psychiatric disorder

Intolerance to empagliflozin or other agents relevant to study

Non-compliant

Intervention

Participants will be randomised to receive once-daily empagliflozin 25 mg or placebo (in the morning) for 2 weeks as add-on to ongoing therapy. Empagliflozin and placebo will be manufactured and labelled by Boehringer Ingelheim. The dosage of empagliflozin is standard medical treatment of T2D.34 Possible administration of sulfonylurea drugs to participants will be paused 1 week before the start visit and during the intervention to avoid hypoglycaemia during the trial. Otherwise, there will be no restriction to concomitant treatment. Participants will be encouraged not to change their lifestyle (i.e. diet, exercise and smoking status) during the trial.

Trial medicines comply with Good Manufacturing Practice regulations.35 Participants receive text message reminders of medicine intake during the intervention period.

Participants will be evaluated compliant to medicine intake at an adherence level of at least 65%.

Outcomes

Primary outcome measurements

The primary outcome of the trial will be the difference between 24-hour urinary excretion of 8-oxoGuo and 8-oxodG before and after the intervention, which will be compared between the two treatment groups.

Secondary outcome measurements

The secondary outcome will be the difference between MDA in plasma before and after the intervention, which will be compared between the two groups. Further, this study correlates the concentration of iron, transferrin, transferrin saturation, and ferritin with the urinary excretion of 8-oxoGuo and 8-oxodG.

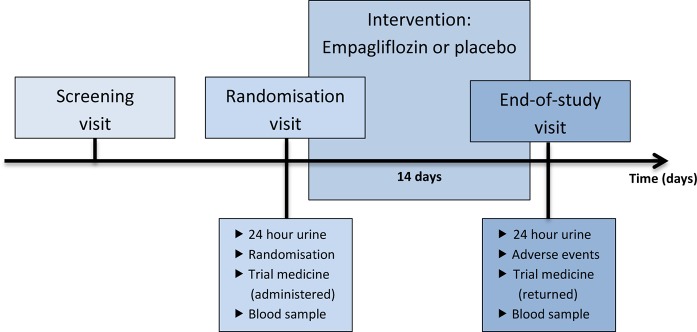

Participant timeline

Participant timeline is illustrated in figure 1. Potential participants will be informed about the trial in relation to their outpatient consultation at the hospital. If they are interested in participating, a screening visit will be conducted after informed consent. At the screening visit, eligibility will be investigated. Blood pressure, pulse, height, and weight will be measured.

Figure 1.

Participant timeline.

Participants will be fasting at the randomisation and end-of-study visit. At the randomisation visit, trial medicine will be dispensed to participants, and 24-hour urine sample and a venous blood sample will be collected. After a 14-day treatment schedule, the end-of-study visit will take place. Participants will deliver the 24-hour urine sample and excess trial medicine, and a venous blood sample will be collected. All adverse events will be registered.

The 24-hour urine sample will be collected from the morning of the day before the visit to the morning of the day of the visit. The participant will empty his bladder in the morning before the collection of 24-hour urine begins.

The first participant’s screening visit is expected to be on 25 October 2016. The last participant’s end-of-study visit is expected to be on 31 July 2017.

Sample size

An a priori power calculation has been performed with type I error risk of 5% and type II error risk of 20%. Values of the primary outcomes are about 30 nmol with SD of 6 nmol per 24 hour based on baseline values from the PENTRIOX trial.36 Smoking increases urinary excretion of 8-oxodG by 50% (95% CI 31% to 69%).37 We wish to be able to detect an effect size of 20%, since we do not believe smaller changes are clinically relevant. The type 1 and type 2 errors are set at conventional values.

The power calculation based on these assumptions estimated 17 participants in each group using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Assignment of intervention

The randomisation will be carried out through a simple randomisation with a 1:1 allocation ratio from a computer-generated list of random numbers.

The list of random numbers will be made by an employee who otherwise will be uninvolved in the study. The allocation sequence will be concealed from the investigators and healthcare staff enrolling and assessing participants.

The physicians responsible for the treatment of patients with T2D in the outpatient clinic will inform potential participants about the trial and will offer them an information meeting. At the information meeting, ELL, LKK, and/or VC will inform potential participants about the trial, and the potential participants will receive written information as well. The screening visit will be performed by ELL, LKK, and/or VC after written informed consent is obtained. ELL, JR, TV, and FKK will be responsible for the enrolment of participants and assignment of intervention. The end-of-study visit will be performed by ELL, LKK, and/or VC. HEP is the sponsor-investigator of the study. JR is the principal investigator of the study.

Only HEP, ELL, LKK, and VC will have access to the final dataset until after analysis of the data. After analysis and code break of the trial all investigators have full access to the dataset.

Participants, research coordinator, investigators and laboratory technicians will be blinded until data are analysed.

Code break of a participant’s trial medicine will occur only under exceptional circumstances when knowledge of treatment is absolutely necessary. Only the principal investigator and an employee who is otherwise uninvolved in the study will be able to perform a code break. Since they will not be part of the data analysis, a potential code break will not be of critical importance.

Data collection, analysis and management

Urine and plasma samples will be collected at the randomisation visit and the end-of-study visit. In order to improve adherence of the 24-hour urine sample, participants will receive three text message reminders of the sample collection during the sample collection period. If participants record loss of a urine void, 150 mL will be added to the recorded diuresis. Participants will be evaluated for their compliance to 24-hour urinary collection at an adherence level of at least 75%.

Urine samples will be stored at −20°C until data analysis. The samples will be analysed after last participant’s end-of-study visit by ultra-performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS). The frozen urine samples will be heated to 37°C and centrifuged at 10 000 g for 5 min prior to addition of lithium acetate and internal standard. The chromatographic separation will be performed by an Acquity UPLC I-class system with an Acquity UPLC BEH Shield RP18 column (1.7 µm, 2.1×100 mm) (Waters, Milford, Massachusetts, USA) with mobile phases A: 5 mM ammonium acetate and B: acetonitrile. The mass spectrometric detection will be performed by a Xevo TQ-S triple quadrulope mass spectrometer (Waters, Milford, Massachusetts, USA) with Intellistart function (MassLynx V.4.1).18 Further details of the method and quality control are described elsewhere.18 Liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) is the preferred method to determine urinary excretion of 8-oxoGuo and 8-oxodG due to the high specificity.38

Plasma samples will be stored at −80°C until data analysis. The samples will be analysed after last participant’s end-of-study visit by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). Phosphotungstic acid will be added to the samples before centrifuged for 3 min at 16 000 g. Then butylated hydroxytoluene will be added to avoid further peroxidation. Thiobarbituric acid (TBA) reagent and acetic acid will be added and the mixture will be heated to 95°C for 60 min to form MDA(TBA)2 adduct. MDA(TBA)2 will be determined by HPLC with fluorescence detection (excitation, 515 nm; emission).31 Further details of the method and quality control are described elsewhere.31 The HPLC method has a high specificity, thus preferred for determining MDA.39

The study will collect demographic and baseline information from the participant’s physicians.

All data will be written in Case Report Form (CRF). CRFs will only be available for investigators and research coordinator, stored at trial site locked away according to ICH-GCP guidelines.40 The data will be entered into a locked database by double data entry after last participant’s end-of-study visit.

The trial will be monitored by the GCP unit, Bispebjerg Hospital, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen, Denmark. The GCP unit and the Danish Medicines Agency will be able to conduct an audit of the trial independent of sponsor-investigator and investigators.

The treatment period will be short, and empagliflozin is in general well tolerated. Therefore, only few adverse reactions are to be expected. Participants will be informed of possible adverse reactions and told to contact an investigator if he experiences a possible adverse reaction. Adverse events will be registered at the end-of-study visit. All adverse events will be reported to the Danish Medicines Agency and the Regional Committee on Biomedical Research Ethics at the end of trial.

Fatal or life-threatening Suspected Unexpected Serious Adverse Reactions (SUSARs) will be reported to Danish Medicines Agency and the Regional Committee on Biomedical Research Ethics within 7 days. Other SUSARs will be reported to Danish Medicines Agency and the Regional Committee on Biomedical Research Ethics within 15 days. The participants will be insured by the Capital Region of Denmark, Gentofte Hospital. Principal investigator will have the final decision on whether an adverse event requires additional treatment, exclusion from the trial, or termination the entire trial.

Statistical analysis

All analyses will be conducted per protocol. Any drop-out of the trial will be described in the results.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics will be compared using a Student’s t-test. If the two groups are not equal after randomisation in demographic or clinical parameters then a logistic regression will be used to correlate the result for these parameters.

The difference in primary and secondary outcomes before and after intervention will be compared between the groups using Student’s t-test.

Data will be evaluated for normal distribution using graphical illustration and the Shapiro-Wilk test, and further validated using a non-parametric test. If data are not normally distributed, data will be log-transformed before analyses or subjected to a non-parametric test for analysis.

A two-sided p<0.05 will be considered statistically significant.

Strengths and limitations

The study explores if empagliflozin influences oxidation of nucleic acids as a prerequisite before conducting a controlled trial with oxidative stress and mortality as endpoints.The strength of this study is the randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blinded trial design. The biomarker 8-oxoGuo is prognostic for mortality in patients with T2D, and the methods for analysis of both primary and secondary outcomes are precise and reliable. A limitation is that the study outcome is not mortality with a long-term follow up, but a biomarker prognostic for mortality in patients with T2D.

ETHICS AND DISSEMINATION

The study has received approval from the Regional Committee on Biomedical Research Ethics (approval number H-16017433), the Danish Medicines Agency, and the Danish Data Protection Agency. The study is performed with informed consent from participants in agreement to the Declaration of Helsinki. Additional plasma samples will be stored at -80˚C for use in future research, locked away at the Department of Pharmacology, University Hospital Rigshospitalet. The results of the study will be presented at national and international conferences, and submitted at a peer-review international journal.

bmjopen-2016-014728supp001.jpg (8KB, jpg)

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: This study is based on an idea of HEP. HEP, ELL, VC, LKK, TV, FKK and JR contributed to the trial design. ELL wrote the first protocol draft. HEP, VC, LKK, TV, FKK and JR contributed to the development of study protocol and approved the final draft.

Funding: This study is sponsor-investigator-initiated and investigator-driven and financed by an unrestricted grant from Boehringer Ingelheim. Empagliflozin and placebo are manufactured and provided by Boehringer Ingelheim. VC has received the Faculty PhD Scholarship from the Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, University of Copenhagen.

Competing interests: JR has received lecture fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly and Company, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novo Nordisk and Sanofi, and is a member of the Advisory boards of Novo Nordisk, Merck Sharp & Dohme and Sanofi. TV has received lecture fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly and Company, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novo Nordisk, Novartis, Sanofi, and Zealand Pharma, and is a member of the Advisory Boards of Amgen, Novo Nordisk, Merck Sharp & Dohme and Bristol-Myers Squibb/AstraZeneca. FKK has received lecture fees from, is a member of the Advisory Boards of, has consulted for, and/or received research support from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Eli Lilly, Gilead Sciences, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novo Nordisk, Ono Pharmaceuticals, Sanofi and Zealand Pharma. ELL has received a 12 months scholarship from Boehringer Ingelheim. All other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. Global Report on Diabetes. 2016. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/204871/1/9789241565257_eng.pdf

- 2. Shah AD, Langenberg C, Rapsomaniki E, et al. Type 2 diabetes and incidence of cardiovascular diseases: a cohort study in 1·9 million people. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2015;3:105–13. 10.1016/S2213-8587(14)70219-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al. Management of hyperglycaemia in type 2 diabetes, 2015: a patient-centred approach. Update to a position statement of the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Diabetologia 2015;58:429–42. 10.1007/s00125-014-3460-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Patel A, MacMahon S, Chalmers J, et al. Intensive blood glucose control and vascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2008;358:2560–72. 10.1056/NEJMoa0802987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Turnbull FM, Abraira C, Anderson RJ, et al. Intensive glucose control and macrovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia 2009;52:2288–98. 10.1007/s00125-009-1470-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Currie CJ, Peters JR, Tynan A, et al. Survival as a function of HbA1c in people with type 2 diabetes: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2010;375:481–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61969-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Scirica BM, Bhatt DL, Braunwald E, et al. Saxagliptin and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med 2013;369:1317–26. 10.1056/NEJMoa1307684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. White WB, Cannon CP, Heller SR, et al. Alogliptin after acute coronary syndrome in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2013;369:1327–35. 10.1056/NEJMoa1305889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Green JB, Bethel MA, Armstrong PW, et al. Effect of sitagliptin on cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2015;373:232–42. 10.1056/NEJMoa1501352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pfeffer MA, Claggett B, Diaz R, et al. Lixisenatide in patients with type 2 Diabetes and acute coronary syndrome. N Engl J Med 2015;373:2247–57. 10.1056/NEJMoa1509225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Defronzo RA. Banting lecture. From the triumvirate to the ominous octet: a new paradigm for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes 2009;58:773–95. 10.2337/db09-9028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Broedbaek K, Weimann A, Stovgaard ES, et al. Urinary 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2’-deoxyguanosine as a biomarker in type 2 diabetes. Free Radic Biol Med 2011;51:1473–9. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Broedbaek K, Siersma V, Henriksen T, et al. Urinary markers of nucleic acid oxidation and long-term mortality of newly diagnosed type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes Care 2011;34:2594–6. 10.2337/dc11-1620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Broedbaek K, Siersma V, Henriksen T, et al. Association between urinary markers of nucleic acid oxidation and mortality in type 2 diabetes: a population-based cohort study. Diabetes Care 2013;36:669–76. 10.2337/dc12-0998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Glintborg B, Weimann A, Kensler TW, et al. Oltipraz chemoprevention trial in Qidong, People’s Republic of China: unaltered oxidative biomarkers. Free Radic Biol Med 2006;41:1010–4. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.06.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Broedbaek K, Henriksen T, Weimann A, et al. Long-term effects of Irbesartan treatment and smoking on nucleic acid oxidation in patients with type 2 diabetes and microalbuminuria: an Irbesartan in patients with type 2 diabetes and microalbuminuria (IRMA 2) substudy. Diabetes Care 2011;34:1192–8. 10.2337/dc10-2214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Poulsen HE, Specht E, Broedbaek K, et al. RNA modifications by oxidation: a novel disease mechanism? Free Radic Biol Med 2012;52:1353–61. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rasmussen ST, Andersen JT, Nielsen TK, et al. Simvastatin and oxidative stress in humans: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Redox Biol 2016;9:32–8. 10.1016/j.redox.2016.05.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ferrannini E, Solini A. SGLT2 inhibition in diabetes mellitus: rationale and clinical prospects. Nat Rev Endocrinol 2012;8:495–502. 10.1038/nrendo.2011.243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zinman B, Wanner C, Lachin JM, et al. Empagliflozin, Cardiovascular Outcomes, and mortality in type 2 Diabetes. N Engl J Med 2015;373:2117–28. 10.1056/NEJMoa1504720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Abdul-Ghani M, Del Prato S, Chilton R, et al. SGLT2 inhibitors and Cardiovascular risk: lessons learned from the EMPA-REG OUTCOME Study. Diabetes Care 2016;39:717–25. 10.2337/dc16-0041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tikkanen I, Chilton R, Johansen OE. Potential role of sodium glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors in the treatment of hypertension. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 2016;25:81–6. 10.1097/MNH.0000000000000199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sattar N, McLaren J, Kristensen SL, et al. SGLT2 inhibition and cardiovascular events: why did EMPA-REG Outcomes surprise and what were the likely mechanisms? Diabetologia 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Oelze M, Kröller-Schön S, Welschof P, et al. The sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitor empagliflozin improves diabetes-induced vascular dysfunction in the streptozotocin diabetes rat model by interfering with oxidative stress and glucotoxicity. PLoS One 2014;9:e112394–13. 10.1371/journal.pone.0112394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cheng ST, Chen L, Li SY, et al. The effects of Empagliflozin, an SGLT2 Inhibitor, on pancreatic β-Cell Mass and Glucose Homeostasis in type 1 Diabetes. PLoS One 2016;11:e0147391–12. 10.1371/journal.pone.0147391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nishimura R, Tanaka Y, Koiwai K, et al. Effect of empagliflozin monotherapy on postprandial glucose and 24-hour glucose variability in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, 4-week study. Cardiovasc Diabetol 2015;14:11 10.1186/s12933-014-0169-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Frijhoff J, Winyard PG, Zarkovic N, et al. Clinical relevance of biomarkers of oxidative stress. Antioxid Redox Signal 2015;23:1144–70. 10.1089/ars.2015.6317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Broedbaek K, Poulsen HE, Weimann A, et al. Urinary excretion of biomarkers of oxidatively damaged DNA and RNA in hereditary hemochromatosis. Free Radic Biol Med 2009;47:1230–3. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Stroh M, Swerdlow RH, Zhu H. Common defects of mitochondria and iron in neurodegeneration and diabetes (MIND): a paradigm worth exploring. Biochem Pharmacol 2014;88:573–83. 10.1016/j.bcp.2013.11.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Poulsen HE, Nadal LL, Broedbaek K, et al. Detection and interpretation of 8-oxodG and 8-oxoGua in urine, plasma and cerebrospinal fluid. Biochim Biophys Acta 2014;1840:801–8. 10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lykkesfeldt J. Determination of malondialdehyde as dithiobarbituric acid adduct in biological samples by HPLC with fluorescence detection: comparison with ultraviolet-visible spectrophotometry. Clin Chem 2001;47:1725–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chan A-W, Tetzlaff JM, Altman DG, et al. Research and Reporting methods annals of internal medicine SPIRIT 2013 Statement : defining Standard Protocol items for clinical trials. 2015;1 10.7326/0003-4819-158-3-201302050-00583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chan AW, Tetzlaff JM, Gøtzsche PC, et al. SPIRIT 2013 explanation and elaboration: guidance for protocols of clinical trials. BMJ 2013;346:e7586 10.1136/bmj.e7586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Jardiance®. http://pro.medicin.dk/Medicin/Praeparater/7463 (accessed 10 Jun 2016).

- 35. European-Commision. Good manufacturing practice. Medicinal products for human and vetrinary use. Annex 13. Investigational medicinal products. 2010;4. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Larsen EL, Cejvanovic V, Kjaer LK, et al. Clarithromycin, trimethoprim, and penicillin and oxidative nucleic acid modifications in humans: randomised, controlled trials. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2017. 10.1111/bcp.13261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Loft S, Vistisen K, Ewertz M, et al. Oxidative DNA damage estimated by 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine excretion in humans: influence of smoking, gender and body mass index. Carcinogenesis 1992;13:2241–7. 10.1093/carcin/13.12.2241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Weimann A, Broedbaek K, Henriksen T, et al. Assays for urinary biomarkers of oxidatively damaged nucleic acids. Free Radic Res 2012;46:531–40. 10.3109/10715762.2011.647693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lykkesfeldt J. Malondialdehyde as biomarker of oxidative damage to lipids caused by smoking. Clin Chim Acta 2007;380:50–8. 10.1016/j.cca.2007.01.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. ICH Harmonised Tripartite Guideline. Guideline for Good Clinical practice E6(R1). ICH Harmon Tripart Guidel 1996. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-014728supp001.jpg (8KB, jpg)