Abstract

Introduction

The care of cancer survivors after primary adjuvant treatment is recognised as a distinct phase of the cancer journey. Recent research highlights the importance of lifestyle factors in treating symptoms, potentially decreasing risk of a cancer recurrence and modifying the risk of developing other chronic illnesses that are increased in the cancer population. Survivorship services aim to deliver care that addresses these issues. The overall aims are to determine the health status of cancer survivors and to evaluate the services offered by the Sydney Survivorship Centre (SSC).

Methods and analysis

This is an observational single-centre study evaluating the longitudinal physical and psychological health, symptoms, quality of life and lifestyle (physical activity and nutrition) of early stage cancer survivors attending the multidisciplinary Sydney Survivorship Clinic and survivors (at any stage of the cancer journey) and caregivers participating in SSC courses. Evaluation of patient satisfaction is included. Patient-reported outcomes and patient characteristics will be summarised using descriptive statistics with Spearman rank sum correlation coefficients to determine associations between patient-reported outcomes. Regression modelling may be used to further evaluate associations and to investigate risk factors and predictors of health outcomes. Qualitative data will be analysed using thematic analysis to identify themes. Sample size will be determined by attendance of consenting patients at clinics and courses.

Ethics and dissemination

The study has received ethics approval from the Concord Repatriation General Hospital Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC/14/CRGH/23). The results will be published and presented at appropriate conferences.

This study will provide important information regarding the health status and needs of Australian cancer survivors and the ability of the survivorship centre to address these needs. These data will shape the future direction of survivorship care in Australia and facilitate the design of interventions or measures to provide better quality of care to this patient population.

Keywords: cancer survivorship, quality of life, survivorship clinic

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Large, longitudinal follow-up with comprehensive assessment of health and well-being of cancer survivors attending a multidisciplinary survivorship centre after primary adjuvant treatment.

Observational cohort study.

Sample size determined by number of patients attending programme and giving consent to deidentified data being used.

Introduction

Until relatively recently, the focus of cancer treatment and research was on the acute treatment of cancer and monitoring for disease recurrence. In 2005, the groundbreaking Institute of Medicine (IOM) report ‘Lost in Transition’ identified the substantial failure of current follow-up care to comprehensively address the needs of adult cancer survivors.1 Through the IOM, the distinct needs of adult cancer survivors have been recognised along with the importance of helping survivors live with the longer-term physical, psychological and practical effects of cancer and its treatment.1

By the broadest definition, a person becomes a cancer survivor when they are diagnosed with cancer, a state that continues throughout the remainder of their life.1 There are estimated to be more than 25 million cancer survivors worldwide, a number that is projected to increase rapidly due to our ageing population, improved screening leading to earlier detection of cancer and improvements in cancer treatments.

Even cancer survivors with no evidence of disease recurrence experience greater ongoing health problems than the general population. Cancer survivors are known to be at increased risk of cardiovascular disease, type II diabetes, metabolic syndrome and osteoporosis, in addition to the risk of a cancer recurrence or a second primary cancer.1–5 There are a number of identified lifestyle risk factors associated with cancer risk and recurrence and the chronic diseases that accompany them. These lifestyle risk factors are modifiable and include obesity, physical inactivity, smoking and inadequate fruit and vegetable intake.6

In an attempt to better address the needs of adult cancer survivors, some cancer centres have established survivorship services, centres or clinics. These services are designed to help survivors and their caregivers better manage their disease and any lasting effects of treatment, beyond the period of acute diagnosis and treatment.5 In addition, many try to facilitate survivors enacting lifestyle changes to increase their physical activity and maintain a healthy weight, in order to aid recovery and improve health-related quality of life (QOL) and possibly for long-term survival.7 Psychological support is an important feature of most programmes and may include psycho-oncology consultations with a clinical psychologist to manage specific concerns such as fear of cancer recurrence, anxiety or depression; general or disease-specific support groups; or counselling support from allied health professionals.8 9

The IOM recommended, with the support of a number of peak bodies including the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), that all cancer survivors transitioning from active to the post-treatment phase should receive an individualised treatment and survivorship care plan (SCP).1 This should include a summary of cancer treatment received and recommendations regarding future clinical care and coordination, including the frequency and nature of surveillance based on the best available evidence. A number of SCP templates are freely available, including generic and disease specific templates from ASCO and Livestrong, which include information on potential late and long-term effects from the cancer and/or treatment(s). Despite recommendations from oncology organisations that SCP should be used, there is limited evidence that they improve long-term outcomes for cancer survivors although survivor satisfaction with the SCP is generally high.10

The Sydney Survivorship Centre (SSC) was established in September 2013 at the Concord Cancer Centre in Sydney. It includes (1) a multidisciplinary survivorship clinic for patients with localised cancer who have completed primary treatment with curative intent (eg, surgery, chemotherapy and radiation therapy) without evidence of cancer recurrence and (2) a range of programmes to support lifestyle change. At the initial clinic visit, patients see a multidisciplinary team (MDT) comprising a medical oncologist or haematologist, a cancer nurse specialist, a dietitian, a clinical psychologist and an accredited exercise physiologist (AEP). Prior to attendance at each clinic, patients complete a number of questionnaires assessing symptoms, physical activity, diet, QOL and well-being and are asked to fill in an evaluation after each clinic. Education regarding healthy lifestyle and encouragement to maintain a healthy weight is an important focus of every clinic. An individualised SCP is developed for each oncology patient.

Approximately two-thirds of survivors attend the clinic once and then return to their regular medical team for ongoing follow-up. At the request of the caring team, the remainder continue follow-up through the survivorship clinic. On subsequent visits, they see the medical oncologist and tumour-specific nurse specialist, with referral to other health professionals and/or programmes as required.

In response to the high proportion of survivors who were overweight or obese, and the increasing evidence supporting obesity as a risk factor for cancer recurrence,11 we established a weight management clinic focused on dietary modification, exercise and behavioural change for those with early stage solid tumours, who have a body mass index >25 kg/m2. The intervention was based on a recent systematic review that reported dietary modification involving restrictions of energy and fat intake and promotion of exercise and behavioural changes were the key components for successful weight loss and maintenance.12

The SSC opened the Survivorship Cottage in May 2014. The cottage is located in the grounds of the hospital, away from the main buildings, and surrounded by gardens and furnished in a homely manner. This is where the majority of the courses are held for cancer survivors at any stage of their cancer journey and their caregivers, with a focus on healthy lifestyle and well-being. The Exercise and Nutrition Routine Improving Cancer Health (ENRICH)13 programme is a 6-week exercise and healthy eating course offered in collaboration with the Cancer Council New South Wales and held regularly throughout the year. Other courses include mindfulness meditation, medical QiGong, yoga, acupuncture, music and art therapy, including scrap-booking, card making, floral design and individual one-off workshops. Courses are selected based on some level of evidence for their efficacy in cancer survivors.14–20 The courses are offered weekly for 10 weeks coinciding with school terms, with four terms each year. Commitment to a full term is required. In addition, we provide support groups and public fora on topics of interest to cancer patients and their caregivers and families.

In keeping with the ASCO guidelines,5 research is an integral component of the survivorship centre. The major research aims of the centre are: (1) to determine the health status, needs, symptoms, QOL and lifestyle characteristics of cancer survivors attending the Sydney Survivorship Clinic or participating in courses; (2) to evaluate changes over time in these variables; (3) to determine risk factors that may affect cancer survivors’ clinical outcomes (eg, metabolic syndrome, obesity and inactivity); (4) to evaluate patients’ and/or their caregivers/family members’ experience with services offered by the SSC, and (5) to evaluate the MDT approach in addressing cancer survivors’ needs.

Methods and analysis

This is a single-site longitudinal study led by the Survivorship Research Group, University of Sydney, and the SSC, Concord Cancer Centre. Patient-reported outcome (PRO) data are collected as part of standard care and for quality assurance.

SSC Clinic

The SSC clinic commenced in September 2013.

Eligibility

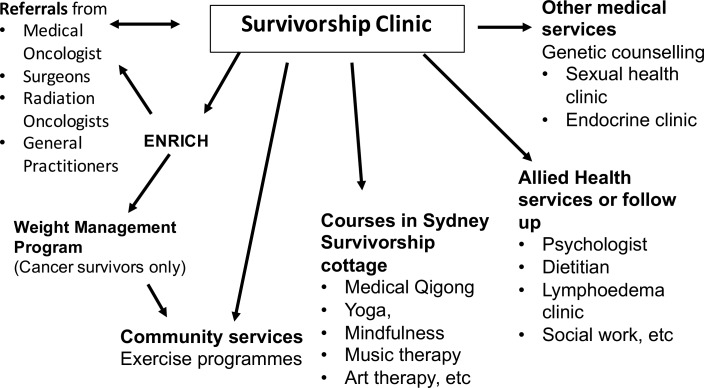

Medical oncology or haematology patients who have completed primary adjuvant treatment for early stage cancer and have no evidence of a cancer recurrence are eligible to attend the survivorship clinic. Patients with breast cancer may be receiving hormonal treatment and/or targeted therapy such as trastuzumab. Figure 1 depicts the referral pathway.

Figure 1.

Referral pathway through the Sydney Survivorship Clinic, centre and courses.

Procedure

Prior to attending the survivorship clinic, patients are sent a package containing printed PRO questionnaires assessing symptoms, psychological well-being, distress, QOL, physical activity, dietary intake and performance status. They are asked to bring the completed questionnaires to their appointment. Those with incomplete questionnaires are asked to finalise them during the clinic visit. Patients with insufficient English or poor literacy skills can have assistance from a health translator, family members or clinic staff during the clinic appointment.

Medical information and weight history are obtained from the medical record. Anthropometry (height and weight) is obtained at the initial visit by clinic staff. An SCP is prepared for oncology patients prior to their initial visit, by either the medical oncologist or the registrar. This plan is refined with the patient after consultation with the MDT members and a copy posted to them after the clinic. Haematology patients may receive a detailed letter from the haematologist with recommendations rather than a formal SCP.

Patients are asked to complete an evaluation form after each clinic visit. In addition, those who have given verbal permission to be contacted subsequently will be asked to complete a satisfaction survey over the phone or in person to provide feedback on how useful the SCP has been, how they used it and if it has been revised. This will be approximately 6 months after their initial visit. A subset of patients will be invited to participate in a qualitative interview to explore, in depth, their experience of the survivorship service.

Sydney survivorship courses

The courses were gradually introduced from 2014.

Eligibility

Posters advertising the programmes are displayed in the Concord Cancer Centre waiting areas. Patients with any stage cancer are able to self-refer to participate in survivorship courses. Patients from the Concord Cancer Centre receive priority for courses, but patients from surrounding hospitals are able to attend if space permits. Carers can accompany a patient and participate if space permits.

Measures used for survivorship clinic and courses

Outcome measures used in this study are comprehensive assessments of patient self-report symptoms, QOL, distress and lifestyle factors. The schedule of assessments and details of measures are outlined in table 1a, b.

Table 1.

(a) Sydney Survivorship Clinic

| Assessment | Initial visit | Follow-up* | |

| Demographics and cancer/cancer treatment characteristics | X | ||

| Clinical examination | X | X | |

| Anthropometry •Weight •Weight history |

X X |

X | |

| Blood tests: As per standard of care For example, colorectal cancer survivors: CEA every 3 months Other blood tests only as clinically indicated |

X | X | |

| Imaging/procedures: As per ASCO guidelines Breast cancer: mammogram and/or breast ultrasound annually. Colorectal cancer: CT chest/abdomen/pelvis annually for 5 years. Colonoscopy: 1 year after diagnosis then frequency dependent on the result Results of other procedures as ordered by oncology team as part of standard of care. |

X | X | |

| PRO | |||

| Distress (Distress Thermometer)22 | X | X | |

| Symptoms (Patient’s Disease and Treatment Assessment Form)21 | X | X | |

| Sedentary time (Sitting Questionnaire)25 | X | X* | |

| Physical activity (Active Australia Questionnaire)24 | X | X* | |

| Three-day food diary and food questionnaire | X | X* | |

| QOL questionnaire (FACT-G)23 | X | X* | |

| ECOG Performance Status26 | X | X | |

| Evaluation | SSC feedback questionnaire | X | |

| SSC satisfaction survey | X | X | |

| Treatment and survivorship plan evaluation | X | X* |

*Follow-up will be individualised depending on tumour type and stage of disease but will generally be every 3–6 months. With the exception of the Distress Thermometer, Patient’s Disease and Treatment Assessment Form and the self-rated performance status, questionnaires will not be completed more frequently than every 6 months.

ASCO, American Society of Clinical Oncology; CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; ECOG, Eastern Co-operative Oncology Group; FACT-G, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy—General; PRO, patient-reported outcome; SSC, Sydney Survivorship Centre; QOL, quality of life.

(b) Courses for Sydney Survivorship Centre

| Assessment | Initial visit | Conclusion of programme |

| Baseline demographics and disease characteristics | X | |

| Questionnaires: | X | X |

| • FACT-G23 | X | X |

| • FACT-F subscale27 | X | X |

| • FACT-Sp subscale*28 | X | X |

| • Patient’s Disease and Treatment Assessment Form21 | X | X |

| • Distress Thermometer22 | X | X |

| • Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale29 | X | X |

| Participant evaluation | X | X |

*Only for medical Qigong, yoga, mindfulness, acupuncture and music and well-being.

FACT, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (G, general; F, fatigue; Sp, spirituality).

End points

The global aim of this multifaceted project is to evaluate the SSP clinic and programmes. We aim to assess changes in the end points, stated below, over time.

Survivorship clinic

Incidence and severity of symptoms that may be associated with cancer and/or treatment—as assessed by the Patient’s Disease and Treatment Assessment Form.21 This is a 48-item questionnaire assessing symptoms with responses ranging from 0 to 10 (no trouble at all to worst I can imagine) over the previous month.

Distress—as assessed by the Distress Thermometer.22 This asks participants to rate their level of distress over the previous week from 0 to 10 (no distress to extreme distress).

QOL as assessed by the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy—General (FACT-G).23 This 27-item questionnaire assesses physical, social, emotional and functional well-being over the previous week, with ratings from 0 to 4 (not at all to very much).

Physical activity and sedentary behaviour—as assessed by the Active Australia Exercise Questionnaire24 and the Sitting Questionnaire25 and AEP consultation. Active Australia is a four-item questionnaire evaluating the time spent performing physical activity and the intensity of the activity in the previous week. The Sitting Questionnaire is a two-item questionnaire assessing the time usually spent sitting, on a weekday and on a weekend.

Dietary intake and behaviour—as assessed by an in-house 3-day food diary and food questionnaire and dietitian consultation. The four-item food questionnaire assesses changes made to diet since a cancer diagnosis/treatment, average number of serves of fruit, vegetables, dairy and soft drinks daily and alcohol intake.

Eastern Co-operative Oncology Group Performance Status26—as assessed by both clinician and participant.

Clinical assessments: medical and physical assessment by doctor and nurse, fear of cancer recurrence assessed by clinical psychologist, anthropometric assessment.

Effectiveness of MDT in addressing survivors’ needs measured by change in outcomes, for example, QOL, sedentary behaviour, etc.

Use and effectiveness of treatment and SCP. To determine the incidence of patients attending the survivorship clinic who receive a survivorship plan, are referred to other health professionals from clinic and use the SCP (eg, show other health professionals and carry out the clinic recommendations). Whether patients found the SCP helpful, did it contain new information, and suggestions for improvement.

Clinical progress as determined by results of clinical examination, blood tests and/or imaging ordered as part of standard of care.

Effectiveness of surveillance system: total number of cases of cancer recurrence and disease-free survival.

Patients’ experience with Sydney Survivorship Clinic, developed by the authors, asking patients to rate how useful the session with each member of the MDT was and how well their questions were answered. They also rate how worthwhile it was attending the clinic and give reasons for their answer and comment on the length and timing of the clinic in their cancer journey. Finally, they are asked whether they would recommend the clinic to others and any additional information or services they would have liked to receive.

Specific SSC programmes

Weight management programme

Facilitated and supervised by AEP and dietitian

Eligibility: body mass index >25 kg/m2; attendance at the Sydney Survivorship Clinic, completion of the Exercise and Nutrition Routine Improving Cancer Health 6-week lifestyle programme

Attendance (number of enrolees, proportion completing programmes and reasons for non-attendance)

QOL, symptoms, food intake, exercise behaviour, knowledge/practice and changes compared with baseline assessment

Lifestyle outcomes: anthropometry measurements, vital signs, aerobic capacity and muscular strength—weeks 0, 12 and 26 and then every 6 months until 2 years

Blood results collected as part of standard of care

Patient experience as measured by a satisfaction survey and interview (see online supplementary appendix table 1)

bmjopen-2016-014803supp001.pdf (83.7KB, pdf)

Mindfulness, QiGong, yoga, music therapy, art therapy or similar courses

Attendance (number of enrolees, proportion completing programmes and reasons for non-attendance)

Clinical outcomes: demographics, cancer diagnosis and treatment

Symptoms: assessed by the Patient’s Disease and Treatment Assessment Form21

Psychosocial outcomes (completed preintervention and postintervention)

QOL and fatigue assessed by the FACT-G23 and the 13-item FACT Fatigue subscale27

Spiritual well-being assessed by the 12-item FACT Spiritual subscale28 (for mindfulness, yoga medical Qigong, acupuncture and medical well-being courses)

Symptoms of anxiety and depression assessed by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale29

Distress assessed by the Distress Thermometer22

Eastern Co-operative Oncology Group Performance Status (patient rated)26

Participant satisfaction questionnaire at the end of programme only

In-depth qualitative exploration of patient experience

Cancer survivors and/or caregivers/family members will be invited to participate in focus group(s) and/or interviews to provide in-depth feedback about their experience of SSC services and information about unmet needs to guide the direction of the SSC clinic or programmes. Both focus groups and telephone interviews are offered to ensure maximum access for individual participants via these flexible options. Consenting individuals will attend a focus group meeting, a face-to-face interview or a telephone interview with staff of the University of Sydney who are not involved in their clinical care. All interviews are semistructured, following an ethics approved interview guide developed for the clinic and each programme.

To monitor changing experiences of the clinic over time, groups of attendees will be purposively sampled periodically on the basis of their disease group, side effect profile and the programmes attended.

Qualitative data will be transcribed verbatim and analysed using thematic analysis.

Data analysis and statistical issues

This protocol describes a data collection process that is ongoing as part of service evaluation. The sample included in each analysis will be dependent on the specific questions asked, with specific hypotheses developed prior to analyses, and the sample size determined for each proposed analysis. The sample size will be determined by attendance of consenting patients at clinics and courses. It is estimated that the survivorship clinic will see 100 new patients per year, of whom 90% will consent to the use of their deidentified data. The first evaluation of initial clinic visits will be performed after 3 years, with an estimated sample size of 300 new patients. This would be considered of clinical significance for determining health status. Approximately 25% of the medical oncology patients receive their follow-up at the survivorship clinic. We will perform a longitudinal analysis once we have a 3-year follow-up for 150 patients. A 3-year disease-free survival is considered a surrogate marker for overall survival for some common tumour types,30 and this time frame would provide important information on longitudinal health status of survivors.

Outcomes and patient characteristics will be summarised using standard descriptive statistics for each group. Missing data on the PRO will be handled according to the guidelines for each questionnaire. Comparison of results between groups (eg, comparing PRO between tumour types) will be performed using Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables, Cochran-Armitage test for trend for ordinal variables and exact χ2 tests for categorical variables. Spearman rank sum correlation coefficients will be used to determine associations between PROs. Regression modelling may be used to further evaluate associations and to investigate risk factors and predictors of health outcomes.

For longitudinal changes in PROs, a 10% change in the scale from baseline will be considered a clinically meaningful change.31 A comparison of change over time in symptoms and behaviours will be performed. Changes in PRO at each time point will be analysed, and regression analyses may be subsequently performed for major health status outcomes, to adjust for variables such as time since treatment completion and tumour site.

Qualitative data analysis

Interview data will be analysed using thematic analysis with at least two people involved in the analysis. Data coding will occur within a framework using MS Office Excel.32 Rigour will be ensured through multiple readings of the data, multiple coders, cross-coding and member checking of themes with attendees of the clinic.

Discussion

Survivorship concerns are increasingly recognised as poorly addressed in many standard follow-up appointments. There is considerable debate and a lack of evidence regarding how best to follow-up cancer survivors. Multidisciplinary clinics have the capacity to provide holistic care with a focus on education for lifestyle issues, prevention of long-term side effects and psychological well-being, but they are resource intensive for staff.

Physically active lifestyle and healthy weight have been shown in observational studies to decrease the risk of common cancers and cancer recurrence. Studies have also shown that physical activity and healthy nutrition can improve symptoms associated with cancer treatment and decrease the risk of chronic diseases that are commonly found in cancer survivors, including metabolic syndrome, obesity, type II diabetes, cardiovascular disease and osteoporosis.33 Although a number of cancer organisations have published recommendations regarding exercise and weight, the majority of patients with cancer are overweight or obese, and most do not meet the guidelines of 150 min/week of moderate intensity physical activity, two sessions of resistance exercise/week and minimising sedentary activities, despite the increasing evidence for benefit.33 34 This suggests that cancer survivors require additional support and education to facilitate instituting important lifestyle changes.

The SSC has the potential to improve physical and psychological well-being and QOL for cancer survivors. This study will obtain unique data regarding the benefits of an MDT survivorship clinic for patients with cancer who have completed primary adjuvant treatment and evaluation of the courses offered by the SSC for patients at any stage of the cancer journey and their caregivers/family. This will help determine whether assessing health status and providing education and lifestyle programmes facilitate adoption and adherence to a healthy lifestyle, and whether this can lead to improvement in well-being. Further, it will evaluate the SCP through usage in routine clinical practice, as well as gaining information about who uses the SSC programmes, and patient (and caregiver) satisfaction with the clinic and courses.

The strengths of the study are that it will provide a large sample size with longitudinal follow-up with comprehensive assessment of health and well-being of cancer survivors attending a multidisciplinary survivorship centre after primary adjuvant treatment. Limitations of the study include that it is an uncontrolled, observational cohort study, with the sample size dependent on the number of patients attending the clinic and programmes who consent to their deidentified data being used.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval has been obtained from Concord Repatriation General Hospital Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC/14/CRGH/23). Patients attending clinics and courses at the SSC are given the option of a tick box to ‘opt out’ if they do not wish their deidentified data to be used for research purposes.

Dissemination plan

Study results will be disseminated through a series of peer-reviewed publications and conference presentations.

Data storage and security

Questionnaires are part of standard medical care and are kept in patient‘s oncology subfile. Data are entered into a specifically designed REDCap database, which is password protected and kept on a secure University of Sydney website. Records are identified by a study ID number, and a master list with names kept separately. Data can only be accessed by authorised research team members. Data will be retained in perpetuity after conclusion of the study. After each patient is discharged from the survivorship service through completion of follow-up, disease recurrence or death their data will be fully anonymised by destruction of their details from the master list.

Conclusion

Survivorship services are expanding in Australia and globally. The SSC is the only multidisciplinary clinic of its kind in Australia. This study will provide important information about the health status of Australian cancer survivors and enable us to better understand the symptoms, lifestyle and risk factors of our patient population. This will facilitate the design of supportive measures or interventions to better address these issues.

bmjopen-2016-014803supp002.docx (32.3KB, docx)

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the following people for their assistance with database design and entry. Database design: Anne Warby. Data entry: Erika Jungfer, Loraine Fong and Christopher Mo.

Footnotes

Contributors: JLV, CT, JDT, HD: study concept and design, and writing of the protocol and manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Health Research Ethics Committee, Concord Repatriation General Hospital.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Hewitt ME, Ganz PA; Institute of Medicine (US), American Society of Clinical Oncology (US). From cancer patient to cancer survivor: lost in transition :an American Society of Clinical Oncology and Institute of Medicine Symposium. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Baade PD, Fritschi L, Eakin EG. Non-cancer mortality among people diagnosed with cancer (Australia). Cancer Causes Control 2006;17:287–97. 10.1007/s10552-005-0530-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Holmes MD, Chen WY, Feskanich D, et al. Physical activity and survival after breast cancer diagnosis. JAMA 2005;293:2479–86. 10.1001/jama.293.20.2479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Meyerhardt JA, Giovannucci EL, Holmes MD, et al. Physical activity and survival after colorectal cancer diagnosis. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:3527–34. 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.0855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McCabe MS, Bhatia S, Oeffinger KC, et al. American society of clinical oncology statement: achieving high-quality cancer survivorship care. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:631–40. 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.6854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute Cancer Research.. Food, nutrition, physical activity, and the prevention of cancer: a global perspectiveWashington, DC: World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute Cancer Research, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hewitt ME, Greenfield S, Stovall E; Committee on Cancer Survivorship: Improving Care and Quality of Life, National Cancer Policy Board (U.S.). From cancer patient to cancer survivor: lost in transition. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jacobsen PB. Clinical practice guidelines for the psychosocial care of cancer survivors: current status and future prospects. Cancer 2009;115(18 Suppl):4419–29. 10.1002/cncr.24589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cancer Australia. Clinical guidance for responding to suffering in adults with cancer. Clinical guidelines Sydney: Cancer Australia, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kinnane N, Moore R, Jefford M, et al. ; Survivorship care plans: literature review. Melbourne: Australian Cancer Survivorship Centre, Peter MacCallum, Cancer Centre, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Demark-Wahnefried W, Platz EA, Ligibel JA, et al. The role of obesity in cancer survival and recurrence. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2012;21:1244–59. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ramage S, Farmer A, Eccles KA, et al. Healthy strategies for successful weight loss and weight maintenance: a systematic review. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 2014;39:1–20. 10.1139/apnm-2013-0026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. James EL, Stacey FG, Chapman K, et al. Impact of a nutrition and physical activity intervention (ENRICH: exercise and nutrition routine improving cancer health) on health behaviors of cancer survivors and carers: a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. BMC Cancer 2015;15:710 10.1186/s12885-015-1775-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Buffart LM, van Uffelen JG, Riphagen II, et al. Physical and psychosocial benefits of yoga in cancer patients and survivors, a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Cancer 2012;12:559 10.1186/1471-2407-12-559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lengacher CA, Reich RR, Paterson CL, et al. Examination of broad symptom improvement resulting from mindfulness-based stress reduction in breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:2827–34. 10.1200/JCO.2015.65.7874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Tao WW, Jiang H, Tao XM, et al. Effects of acupuncture, tuina, tai chi, Qigong, and traditional Chinese medicine five-element music therapy on symptom management and quality of life for cancer patients: a meta-analysis. J Pain Symptom Manage 2016;51:728–47. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.11.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhou K, Li X, Li J, et al. A clinical randomized controlled trial of music therapy and progressive muscle relaxation training in female breast cancer patients after radical mastectomy: results on depression, anxiety and length of hospital stay. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2015;19:54–9. 10.1016/j.ejon.2014.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chiu HY, Shyu YK, Chang PC, et al. Effects of acupuncture on menopause-related symptoms in breast cancer survivors: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Cancer Nurs 2016;39:228–37. 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Oh B, Butow P, Mullan B, et al. Impact of medical Qigong on quality of life, fatigue, mood and inflammation in cancer patients: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Oncol 2010;21:608–14. 10.1093/annonc/mdp479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wood MJ, Molassiotis A, Payne S. What research evidence is there for the use of art therapy in the management of symptoms in adults with cancer? A systematic review. Psychooncology 2011;20:135–45. 10.1002/pon.1722 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Stockler MR, O’Connell R, Nowak AK, et al. ; Zoloft’s Effects on Symptoms and Survival Time Trial Group. Effect of sertraline on symptoms and survival in patients with advanced cancer, but without major depression: a placebo-controlled double-blind randomised trial. Lancet Oncol 2007;8:603–12. 10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70148-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tuinman MA, Gazendam-Donofrio SM, Hoekstra-Weebers JE. Screening and referral for psychosocial distress in oncologic practice: use of the distress thermometer. Cancer 2008;113:870–8. 10.1002/cncr.23622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, et al. The functional assessment of cancer therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol 1993;11:570–9. 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.3.570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Brown WJ, Trost SG, Bauman A, et al. Test-retest reliability of four physical activity measures used in population surveys. J Sci Med Sport 2004;7:205–15. 10.1016/S1440-2440(04)80010-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Marshall AL, Miller YD, Burton NW, et al. Measuring total and domain-specific sitting: a study of reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2010;42:9 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181c5ec18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, et al. Toxicity and response criteria of the eastern cooperative oncology group. Am J Clin Oncol 1982;5:649–56. 10.1097/00000421-198212000-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yellen SB, Cella DF, Webster K, et al. Measuring fatigue and other anemia-related symptoms with the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) measurement system. J Pain Symptom Manage 1997;13:63–74. 10.1016/S0885-3924(96)00274-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Peterman AH, Fitchett G, Brady MJ, et al. Masuring spiritual well-being in people with cancer: the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy—Spiritual Well-being scale (FACIT-Sp). Ann Behav Med 2002;24:49–58. 10.1207/S15324796ABM2401_06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bjelland I, Dahl AA, Haug TT, et al. The validity of the hospital anxiety and depression scale. An updated literature review. J Psychosom Res 2002;52:69–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sargent DJ, Wieand HS, Haller DG, et al. Disease-free survival versus overall survival as a primary end point for adjuvant colon cancer studies: individual patient data from 20,898 patients on 18 randomized trials. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:8664–70. 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.6071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Osoba D, Rodrigues G, Myles J, et al. Interpreting the significance of changes in health-related quality-of-life scores. J Clin Oncol 1998;16:139–44. 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.1.139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N. Qualitative research in health care. analysing qualitative data. BMJ 2000;320:114–6. 10.1136/bmj.320.7227.114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Rock CL, Doyle C, Demark-Wahnefried W, et al. Nutrition and physical activity guidelines for cancer survivors. CA Cancer J Clin 2012;62:242–74. 10.3322/caac.21142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schmitz KH, Courneya KS, Matthews C, et al. American College of Sports Medicine roundtable on exercise guidelines for cancer survivors. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2010;42:1409–26. 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181e0c112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2016-014803supp001.pdf (83.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2016-014803supp002.docx (32.3KB, docx)