Abstract

Objective

Inpatient Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) ethnicity data are available but not always collected and data quality can be unreliable. This may have implications when assessing outcomes by ethnicity. An alternative method for assigning ethnicity is using naming algorithms. We investigate if the association between ethnicity and cancer incidence varied dependent on how ethnic group was assigned.

Design

Population-based cancer registry cohort study.

Setting

Yorkshire, UK.

Participants

Cancer registrations from 1998 to 2009 in children and young people (0–29 years) from a specialist cancer register in Yorkshire, UK (n=3998) were linked to inpatient HES data to obtain recorded ethnicity. Patients’ names, recorded in the cancer register, were matched to an ethnic group using the naming algorithm software Onomap. Each source of ethnicity was categorised as white, South Asian (SA) or Other, and a further two indicators were defined based on the combined ethnicities of HES and Onomap, one prioritising HES results, the other prioritising Onomap.

Outcomes

Incidence rate ratios (IRR) between ethnic groups were compared using Poisson regression for all cancers combined, leukaemia, lymphoma and central nervous system (CNS) tumours.

Results

Depending on the indicator used, 7.1%–8.6% of the study population were classified as SA. For all cancers combined there were no statistically significant differences between white and SA groups using any indicator; however, for lymphomas significant differences were only evident using one of the ‘Combined’ indicators (IRR=1.36 (95% CI 1.08 to 1.71)), and for CNS tumours incidence was lower using three of the four indicators. For the other ethnic group the IRR for all cancers combined ranged from 0.78 (0.65 to 0.94) to 1.41 (1.23 to 1.62).

Conclusions

Using different methods of assigning ethnicity can result in different estimates of ethnic variation in cancer incidence. Combining ethnicity from multiple sources results in a more complete estimate of ethnicity than the use of one single source.

Keywords: Ethnicity, Hospital Episode Statistics, naming algorithm, childhood cancer

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We compared ethnic differences in cancer incidence trends in 0–29 years using ethnicity recorded in Hospital Episode Statistics and results from the naming algorithm program Onomap.

Combining ethnicity data from more than once source ensured complete ethnicity information was available for all patients in the study.

We considered three broad ethnic groups, white, South Asian and Other, but were unable to look at specific ethnic groups within these due to small sample sizes.

Name analysis is limited for the classification of ethnicity particularly to individuals of mixed ethnicities.

Introduction

In order to investigate ethnic differences in health, reliable and complete data on ethnic group must be collected. Ideally this information will be collected at the individual level through a self-reported choice within a pre-established classification of ethnic groups, such as those defined by the Office for National Statistics.1 However in routine data sets this information is not always collected or the quality of the data collected may be unreliable.

Since 1995 in England it has been mandatory to collect ethnic group data for all hospital inpatient admissions, which are recorded in Hospital Episode Statistics (HES),2 which should be self-reported by the patient. Initially high levels of missing ethnic codes (either reported as ‘not known’ or ‘not stated’) were reported; in 1996/1997, 44% of inpatient admissions had missing ethnicity recorded.3 However, over time the completeness of ethnicity recording has improved; the percentage of hospital admissions with a missing ethnic group recorded decreased to 14% in 2011/2012.4 Analysis by patient age has shown that children have the highest percentage of missing ethnicity data within HES.5 Furthermore, there is evidence of incorrect coding of ethnicity within HES, which is particularly an issue for non-white patients.4 6

When routinely collected self-reported ethnicity data are not available, naming algorithm software provides a cost-effective method to assign an ethnic group to each individual, provided there is access to the individual’s name.7 When some degree of ethnicity information is already available, name-based classification can provide complementary information to help detect inconsistencies and complete missing data.7

South Asians include individuals whose ancestry is in the countries of the Indian subcontinent, including India, Pakistan and Bangladesh,8 and they make up the largest minority ethnic group in England and Wales, comprising 5.3% of the England and Wales population in the 2011 census.9 Two commonly used naming program to classify individuals into South Asian or non-South Asian groups are Nam Pehchan10 and South Asian Names and Group Recognition Algorithm (SANGRA).11

More recently Onomap has been developed, based on surnames and forenames from public name registers from over 26 countries, which classifies individual names into cultural ethnic or linguistic groups.12 13 It includes all ethnic minority groups in the UK, and unlike Nam Pehchan and SANGRA is not limited to the South Asian group only. The Onomap taxonomy classifies names into one of 185 different types, which are nested within 66 subgroups, which are then nested within 16 larger groups. Onomap has been validated based on regional data in Scotland on two data sets, birth registrations and a school pupil census, with the sensitivity for South Asians ranging from 72% to 75%.14 Onomap defines one group of names as Muslim with origins in the Middle East and this group cannot be directly mapped to the South Asian group. However, in the birth registration study,14 when this group was added to the South Asian group, the sensitivity increased to 90%.14 Onomap has also been validated with HES-recorded ethnicity in patients with cancer in the West Midlands with a sensitivity of 99.8% for white patients and 82% for South Asians, but it was very low for black and Chinese/Other groups (4% and 0%, respectively).15 This study assumed that HES-recorded ethnicity was the ‘gold standard’ and excluded 23% of patients as they did not have a valid ethnic group recorded in HES.15 Neither of these studies used the alternative ethnic group indicators to assess ethnic differences in health outcomes.

In this study we examined cancer incidence trends in children and young people, specifically focusing on groups where routine HES ethnicity data are more likely to be missing,5 using data from the Yorkshire Specialist Register of Cancer in Children and Young People (YSRCCYP).16 Our first aim was to determine the level of agreement between HES and Onomap. Second we investigated if the association between ethnicity and cancer incidence trends varied according to the ethnicity source used.

Methods

Data were extracted from the YSRCCYP database,16 which is a population-based register of children and young people (0–29 years) diagnosed with cancer residing in the Yorkshire and Humber region.16 Data on all registered patients diagnosed between 1998 and 2009 were extracted. Diagnoses were categorised into histological groups according to the International Classification of Childhood Cancer, 3rd Edition.17 We analysed incidence rates for all cancers combined and the three most common diagnostic groups in this age group: leukaemia, lymphoma and central nervous system (CNS) tumours. Other data items extracted included age at diagnosis, year of diagnosis and sex. Patients’ names were available from the YSRCCYP database only and not from HES data.

HES ethnicity

Patients were linked to inpatient HES data (1996–2015) using National Health Service (NHS) number, date of birth, sex and postcode by NHS Digital using their standard deterministic algorithm18; 97.7% of patients were matched to at least one hospital admission. Ethnicity recorded in HES is based on ethnic groups used in the census, and different ethnic groups were recorded in HES from 2001 onwards to reflect changes to the census ethnic group categories,19 for example the inclusion of mixed and Other Asian groups was only available from 2001 onwards. We initially considered five higher level ethnic groups (white, South Asian (including Indian, Pakistani and Bangladeshi), black, Chinese and Other (including mixed and Other South Asian)) (see online supplementary table 1). Within HES data each patient may have more than one admission and multiple ethnic codes may be recorded. For patients with multiple ethnicities recorded (based on the five categories above) (n=195, 5%), the most common ethnic group was assigned to each individual.4 20 21 Due to small numbers in the black and Chinese groups, ethnicity was then categorised as white, South Asian or Other.

bmjopen-2017-016332supp001.pdf (10KB, pdf)

Onomap ethnicity

The surname and forename recorded in the YSRCCYP database for each person were matched to an Onomap type, which is the lowest level in the Onomap classification system. As above, we initially defined individuals into five higher level ethnic groups (see online supplementary table 2) but then aggregated these to white, South Asian or Other to be consistent with the ethnicity groups from HES. Details of the Onomap types included in each of the ethnic groups are shown in online supplementary table 2. The South Asian group includes Indian, Pakistani and Bangladeshi, and a further Onomap type ‘South Asian’. Names that Onomap was unable to recognise were classified as missing (n=14, 0.4%).

Supplementary table 3 shows the numbers in each of the five-category ethnic groups and subgroups for HES and Onomap.

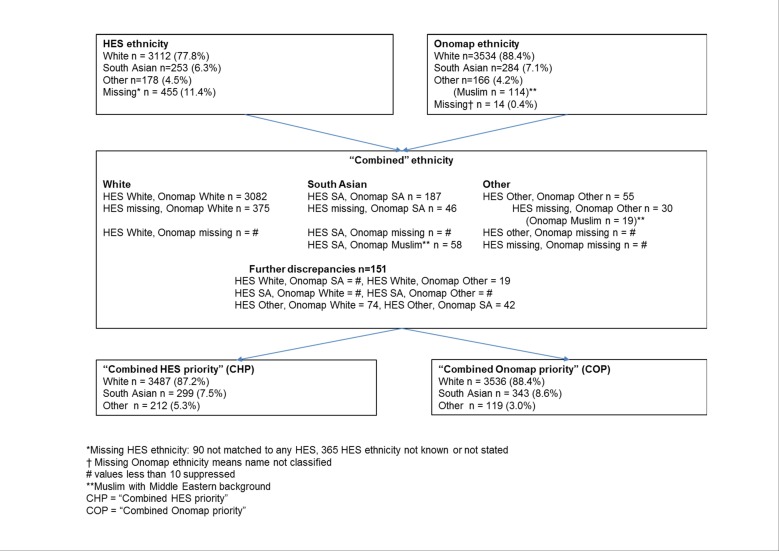

Combined ethnicity

Two further ethnic group indicators were defined based on the combined results of the HES and Onomap ethnic groups (shown in figure 1). If both sources agreed then this group was assigned to each patient. If either source was missing (unclassified in the case of Onomap) but the other was not, then we used the available ethnic group. A further Onomap type is the Muslim group, which is defined as having origins in the Middle East and this group cannot be directly mapped to the South Asian group.14 Where Onomap assigned Muslim and HES was recorded as South Asian, we assigned a South Asian ethnicity. If Onomap and HES ethnic groups were missing, then we assigned the individual to the Other ethnic group (as not picked up as either of white or South Asian origin in the naming algorithm). There were still 151 (3.8%) patients with discrepancies between the two classifications; therefore, we created two further ethnic group indicators: one where these patients were assigned to the HES ethnic group (labelled ‘Combined HES priority’ (CHP)) and another where they were assigned to the Onomap ethnic group (labelled ‘Combined Onomap priority’ (COP)).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of ethnic classification for YSRCCYP data. HES, Hospital Episode Statistics; SA, South Asian; YSRCCYP, Yorkshire Specialist Register of Cancer in Children and Young People.

We included four ethnic group indicator variables based on different sources in our analysis: HES, Onomap and ‘Combined HES priority’ and ‘Combined Onomap priority’, which included the combined categories of HES and Onomap as described above and shown in figure 1.

Populations at risk

Denominators for 1998–2009 for the Yorkshire and Humber region were aggregated from the local government districts which comprise the study area. Midyear population estimates by sex, year, 5-year age band and ethnic group (white, South Asian and Other) were obtained from the ‘ETHPOP’ database for 2001–2009.22 Data for the midyears prior to 2001 were estimated by back-casting the population. The 1998–2009 time-series of annual estimates by ethnic group were constrained to be consistent with the official midyear estimates.23 The ethnic group population estimates were based on broad ethnic groups; therefore, the South Asian group included the Other South Asian category, which was included in the 2001 census but not prior to this. In the 2001 census the Other South Asian group made up 0.5% of the England and Wales population.9 While inclusion of this group in the population denominators may bias our results as there was a discrepancy between the included ethnicities in our numerator and denominator, this was likely to be small as the estimation of rates is much more sensitive to changes in the numerator compared with the denominator.24

Statistical analysis

Agreement between ethnicity from HES and Onomap was measured by the kappa statistic. Direct age standardised incidence rates (ASR) were calculated according to the European Standard population and reported per 1 000 000 person years. Rates over time were presented using four 3-year time periods. Incidence rates were modelled using Poisson regression adjusting for 5-year age group, sex and year of diagnosis. All rates and models were calculated for each of the four ethnic group indicators for all cancers combined, then separately for leukaemia, lymphoma and CNS tumours.

Results

Between 1998 and 2009, 3998 children and young people (0–29 years) were diagnosed with a primary cancer in the Yorkshire and Humber region. Onomap was unable to classify 14 names (0.4%) while HES ethnicity was missing in 455 (11.4%) patients; 90 of these did not match to any HES data while for the remaining 365 ethnic group was not known or not stated in the HES data. After excluding missing data, 87%–88% of the study population were classified as white. The percentage of patients classified as South Asian was 7.1% for HES and Onomap, 7.5 for CHP and 8.6% for COP (table 1). The percentage of patients in the Other ethnic group ranged from 3.0% (COP) to 5.3% (CHP). There was excellent agreement between HES and Onomap ethnic groups (kappa=94.1%).

Table 1.

Ethnic group classification by source, n (%)

| Ethnic group | HES | HES % excluding missing | Onomap | CHP | COP |

| White | 3112 (77.8) | (87.8) | 3534 (88.4) | 3487 (87.2) | 3536 (88.4) |

| South Asian | 253 (6.3) | (7.1) | 284 (7.1) | 299 (7.5) | 343 (8.6) |

| Other | 178 (4.5) | (5.0) | 166 (4.2) | 212 (5.3) | 119 (3.0) |

| Missing | 455 (11.4) | 14 (0.4) |

CHP, ‘Combined HES priority’; COP, ‘Combined Onomap priority’; HES, Hospital Episode Statistics.

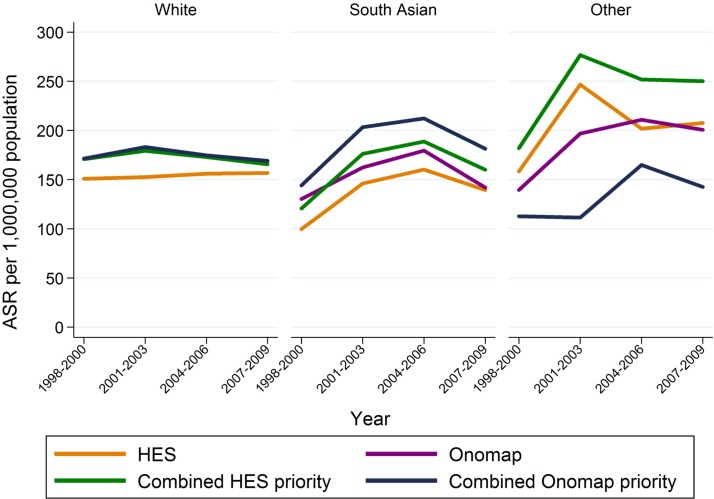

For the white group using HES only provided lower estimates of incidence rates than using Onomap or either of the ‘Combined’ indicators, which all produced similar rates (figure 2, table 2): for all cancers combined, ASR for HES 154 per 1 000 000 population (95% CI 149 to 159) compared with 174 for Onomap (95% CI 168 to 180), 172 for CHP (95% CI 166 to 177) and 174 for COP (95% CI 169 to 180). For the South Asian group, the ASRs were lowest based on HES (ASR=138 (95%CI 121 to 155)) and highest based on COP (ASR=187 (95% CI 167 to 206)). The ASRs for the Other group showed the greatest variability ranging from 135 (95% CI 110 to 159)) based on COP to 241 (95% CI 209 to 274)) based on CHP. These trends were also observed across diagnostic groups (table 2).

Figure 2.

Trends in ASR by ethnic group using different ethnicity classifications, all cancers combined. ASR, age standardised incidence rate; HES, Hospital Episode Statistics.

Table 2.

ASR (95% CI) (directly standardised to the European Standard population) per 1 000 000 population by ethnic group, for all cancers and by diagnostic group, 0–29 years, Yorkshire, 1998–2009

| Ethnic classification and group | All cancers | Leukaemia | Lymphoma | CNS tumours | ||||

| ASR | (95% CI) | ASR | (95% CI) | ASR | (95% CI) | ASR | (95% CI) | |

| HES | ||||||||

| White | 154.0 | (148.5 to 159.4) | 32.5 | (30.0 to 35.1) | 28.4 | (26.1 to 30.7) | 29.1 | (26.7 to 31.5) |

| South Asian | 137.6 | (120.6 to 154.6) | 27.5 | (19.9 to 35.2) | 29.7 | (21.8 to 37.5) | 21.2 | (14.5 to 27.8) |

| Other | 203.6 | (173.6 to 233.6) | 25.6 | (14.9 to 36.3) | 41.2 | (27.9 to 54.6) | 38.4 | (25.2 to 51.5) |

| Onomap | ||||||||

| White | 174.2 | (168.4 to 180.0) | 34.7 | (32.1 to 37.4) | 32.6 | (30.2 to 35.1) | 31.0 | (28.6 to 33.4) |

| South Asian | 154.3 | (136.3 to 172.3) | 29.1 | (21.3 to 37.0) | 38.6 | (29.6 to 47.6) | 19.9 | (13.5 to 26.4) |

| Other | 189.9 | (160.9 to 218.9) | 37.4 | (24.4 to 50.4) | 31.0 | (19.5 to 42.5) | 36.2 | (23.5 to 49.0) |

| CHP | ||||||||

| White | 171.9 | (166.1 to 177.6) | 34.5 | (31.8 to 37.1) | 32.4 | (29.9 to 34.8) | 30.6 | (28.2 to 33.0) |

| South Asian | 162.5 | (144.1 to 181.0) | 34.6 | (26.0 to 43.1) | 35.7 | (27.1 to 44.3) | 21.2 | (14.5 to 27.8) |

| Other | 241.4 | (208.8 to 274.0) | 33.6 | (21.3 to 45.8) | 47.7 | (33.4 to 62.1) | 44.0 | (30.0 to 58.0) |

| COP | ||||||||

| White | 174.3 | (168.5 to 180.1) | 34.8 | (32.1 to 37.4) | 32.6 | (30.2 to 35.1) | 31.0 | (28.6 to 33.4) |

| South Asian | 186.5 | (166.8 to 206.3) | 36.3 | (27.5 to 45.0) | 44.5 | (34.9 to 54.2) | 23.9 | (16.8 to 30.9) |

| Other | 135.1 | (110.8 to 159.4) | 23.2 | (13.0 to 33.4) | 22.9 | (13.1 to 32.8) | 29.1 | (17.6 to 40.5) |

ASR, age standardised rate; CHP, ‘Combined HES priority’; COP, ‘Combined Onomap priority’; HES, Hospital Episode Statistics; CNS, central nervous system.

For all cancers combined, generally the trends over time were in the same direction for all four indicators for the white and South Asian groups; for the white group the rates were stable over time and there was some indication of an increase over time for South Asians. For the Other ethnic group the direction of the trends varied by indicator mainly due to small numbers within this group (figure 2).

Results from the Poisson regression models (table 3) showed that for all cancers combined, statistically significant differences between ethnic groups were evident using three of the four indicators but with differing direction of associations found between the white and Other ethnic groups. Incidence was 32% higher in the Other ethnic group based on HES (95% CI 1.13 to 1.53), 41% higher based on Onomap (95% CI 1.23 to 1.62) and 22% lower based on COP (95% CI 0.65 to 0.94). For lymphoma incidence was higher in South Asians when using COP only (incidence rate ratio=1.36 (95% CI 1.08 to 1.71)), while for CNS tumours relatively consistent differences were found based on three indicators (HES, Onomap and CHP), where incidence was between 27% and 35% lower in South Asians compared with whites.

Table 3.

IRR and 95% CI from multivariable models by ethnic group, for all cancers and by diagnostic group, 0–29 years, Yorkshire, 1998–2009

| Ethnic classification and group | All cancers | Leukaemia | Lymphoma | CNS tumours | ||||

| IRR | (95% CI) | IRR | (95% CI) | IRR | (95% CI) | IRR | (95% CI) | |

| HES | ||||||||

| White | 1 | – | 1 | – | 1 | – | 1 | – |

| South Asian | 0.90 | (0.79 to 1.02) | 0.85 | (0.64 to 1.13) | 1.04 | (0.79 to 1.38) | 0.73 | (0.53 to 1.01) |

| Other | 1.32 | (1.13 to 1.53) | 0.79 | (0.52 to 1.21) | 1.46 | (1.05 to 2.04) | 1.30 | (0.92 to 1.85) |

| Onomap | ||||||||

| White | 1 | – | 1 | – | 1 | – | 1 | – |

| South Asian | 0.89 | (0.79 to 1.00) | 0.84 | (0.64 to 1.12) | 1.18 | (0.92 to 1.50) | 0.65 | (0.47 to 0.91) |

| Other | 1.09 | (0.93 to 1.27) | 1.08 | (0.76 to 1.54) | 0.97 | (0.66 to 1.41) | 1.15 | (0.80 to 1.65) |

| CHP | ||||||||

| White | 1 | – | 1 | – | 1 | – | 1 | – |

| South Asian | 0.95 | (0.84 to 1.07) | 1.01 | (0.78 to 1.31) | 1.10 | (0.86 to 1.42) | 0.70 | (0.50 to 0.96) |

| Other | 1.41 | (1.23 to 1.62) | 0.98 | (0.68 to 1.43) | 1.50 | (1.10 to 2.04) | 1.43 | (1.03 to 1.98) |

| COP | ||||||||

| White | 1 | – | 1 | – | 1 | – | 1 | – |

| South Asian | 1.07 | (0.96 to 1.20) | 1.05 | (0.81 to 1.35) | 1.36 | (1.08 to 1.71) | 0.78 | (0.57 to 1.05) |

| Other | 0.78 | (0.65 to 0.94) | 0.67 | (0.43 to 1.05) | 0.72 | (0.47 to 1.12) | 0.93 | (0.62 to 1.38) |

Models adjusted for age group, sex and year.

CHP, ‘Combined HES priority’; CNS, central nervous system; COP, ‘Combined Onomap priority’; HES, Hospital Episode Statistics; IRR, incidence rate ratio.

Discussion

It is essential to have valid and complete ethnicity data in order to investigate differences between ethnic groups and develop strategies to tackle inequalities and allocate resources appropriately.25 We set out to determine if using different sources of ethnicity data would result in different conclusions being made when assessing ethnic inequalities in cancer incidence in children and young people, comparing ethnic groups recorded in HES and ethnic groups based on patient names obtained from the Onomap program. These two sources were then combined to create alternative ethnic groups using information from both sources. Our results show that in general incidence trends over time were similar in direction regardless of the ethnicity source used. However, the size of the estimates and the magnitude of the differences between ethnic groups varied depending on the indicator used. This may even lead to differences in statistical significance and therefore different conclusions being drawn: for example, considering all cancers combined, the two combined indicators resulted in differing directions of associations between the white and Other ethnic groups. However for CNS tumours three of the four indicators produced similar estimates.

Some studies have found incidence rates in children and young adults to be higher in South Asians for all cancers combined,26–28 while others have found similar rates in South Asians and non-South Asians.16 29 30 These studies included a variety of sources to assign ethnic group, including Nam Pehchan,26 30 a combination of Nam Pehchan and SANGRA,29 a combination of Nam Pehchan and HES,16 HES alone but only including the Indian group,27 and ethnicity recorded in medical records.28 Several of these studies used a dichotomous classification of South Asian and non-South Asians.16 26 29 30 In our study we were able to consider three ethnic groups white, South Asian and Other, although the numbers in the Other group were based on relatively small numbers. Childhood cancers are rare and our analysis showed that grouping a few cases in different groups may change the direction and statistical significance of results, as we observed for the Other group for all cancers combined.

It is now mandatory to collect ethnicity data in HES.2 Although the completeness of this information has improved over time, there are still a substantial percentage of HES episodes without ethnicity recorded,3 including 9% of our study population. These patients were excluded for the analysis of HES data and we observed that the ASR for the white group based on HES ethnicity alone was lower compared with the other ethnicity indicators, which suggests that missing HES ethnicity data may be more likely for white patients. Another issue with using HES ethnicity is that it is collected for each admission and patients in this study may have had more than one hospital admission (94% of patients had more than one admission with a median of 17 admissions per patient (IQR 7–37)), and therefore potentially more than one ethnic group recorded; this applied to 5% of our study population. Several studies have recommended assigning the most common ethnic group as this uses the most information for each patient4 20 21; we also adopted this strategy to deal with multiple recordings of ethnicity. Of the 5% of patients with more than one ethnic group recorded, according to the most common HES ethnic group, 37% were white, 30% South Asian and 33% Other, compared with Onomap ethnic group distribution of 46% white, 35% South Asian and 19% Other (agreement of 63%). We only considered three broad ethnic groups, but further discrepancies may be evident when considering the full range of ethnic groups recorded in HES. The validity of HES-recorded ethnicity has been compared with self-reported survey data for patients with cancer in England in 2011 and found that 5% of patients had ethnicity incorrectly recorded in their HES record, with greater levels of incorrect coding for ethnic groups other than white British.6 Another study assessing the completeness and usability of HES data in England from 1997 to 2001 found different ethnic groups were recorded for 6% of inpatients with ethnicity recorded on more than one occasion.4 Not only is it important to ensure the completeness of HES ethnicity, the accuracy of the data needs to be improved particularly for ethnic groups other than white British. Users of HES data should be aware of the potential misclassification of ethnicity within the data.

Onomap has been validated in several studies,14 including against HES15; however, these studies did not assess any outcomes in relation to the different ethnicity sources. Onomap has also been used to assign missing ethnicity information for patients when it was lacking from other hospital and clinical data sets.31 We used Onomap to assign ethnic group when HES data were missing, but our combined indicators also considered both sources of ethnic group to improve precision. For example, Onomap classified 3% of our study patients as Muslim with origins in the Middle East, and this group could not be mapped directly to be of South Asian origin14; however, by combining with HES data, we were able to define these patients as South Asian if this was also recorded in HES. When combining HES and Onomap ethnic groups, there were still a small number of discrepancies between the two sources and we found that using either source to assign ethnic group resulted in very similar patterns of trend and conclusions for the white and South Asian group but not for the Other group, mainly due to the small sample size.

Ethnic group information has been included in UK censuses since 1991 and provides important denominator data for the calculation of rates.32 In this study we use these denominators for all calculations of rates regardless of the indicator used (HES or Onomap or the ‘Combined’ indicators). Unfortunately we were unable to estimate the population denominator for the South Asian group excluding the Other South Asian group; therefore, there was a slight discrepancy between the definitions of the South Asian group in the numerator and denominator for the calculation of rates. However, we think this will have limited impact on our results as population estimates are in themselves an estimate and therefore prone to error, and these were based on ethnicity collected from the census combined with other sources, all of which may also be prone to classification bias.33 Further, the estimation of the rates is much more sensitive to changes in the numerator rather than the denominator, particularly in this study where we have calculated rates per million population as standard in childhood cancer epidemiology. Therefore even with these caveats the population denominator data used represent the best available data to estimate these rates and are still valid.

One of the main limitations of name analysis is the classification of ethnicity to individuals of mixed ethnicities and women’s ethnicity in mixed marriages.7 Names analysis also may not be able to distinguish between names that are common to more than one ethnic group. Over time as population trends change, such as increases in marriage between ethnic groups, the use of names analysis may be more limited.7 34 In the future we may need to collect more than ethnicity data alone and include additional items such as language and religion to represent the multidimensionality of ethnicity.35 This may be further complicated in studies of children and young people as a proxy report (from parent or carer, for example) may be needed for infants and young children until children reach an age when they are able to report their own ethnic group; therefore, depending on the age range of the study, there may be more than one method used to ascertain ethnicity.

In our study we used three broad ethnic groups, white, South Asian and Other. Although there is heterogeneity within these broad ethnic groups, we were unable to look at specific ethnic groups within these due to small sample sizes. Much of our South Asian group was of Pakistani origin, which reflects the ethnic distribution of the Yorkshire and Humber region.36 Ideally we would consider the Pakistani, Indian and Bangladeshi groups as separate groups; however, this was not possible in this study due to small numbers in the Indian and Bangladeshi groups. Due to changes in the census ethnic categories over time, we were unable to include the Other South Asian group in the South Asian group as this information was not available in HES prior to 2001, so was included in the Other ethnic group. The Other group comprises a heterogeneous mix of ethnicities, therefore limiting the interpretation of the results, but they were included in this study for completeness.

Many studies lack information on the methods used to record and classify ethnic groups35 and exclude patients where ethnicity data are missing. It is important that individuals with missing ethnicity are not excluded, and alternative methods, such as linking to other data sources and utilising naming algorithms, are used to assign an ethnic group.25 This study proposes an alternative method to combine two commonly used ethnicity sources in epidemiological studies. If ethnicity is not self-assigned by patients in a source but names are available, it seems likely that Onomap has the potential to provide results with research utility. Further examination and validation of these methods in other studies is needed.

Conclusions

Self-reported ethnicity is the gold standard; however, this is not always available, and in routine data sets such as HES may be incomplete or inaccurate, and therefore other ways to obtain ethnicity data may be needed, including the application of naming algorithms. Utilising different ethnicity sources alone may result in different conclusions regarding inequalities between ethnic groups; therefore, combining ethnicity from more than one source, even if incomplete, provides a more complete and robust estimate of ethnicity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Paula Feltbower for meticulous data collection, and the cooperation of all oncologists, pathologists, GPs and medical records staff in Yorkshire. We thank the NHS Digital for provision of linked HES data.

Footnotes

Contributors: LS, PN, RCP and RGF contributed to the study concept and design. LS analysed the data and drafted the manuscript. LS, PN, MK, SF, LKF, RCP and RGF contributed to the interpretation of results and critical revision of the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the Candlelighters Trust, which funded the Yorkshire Specialist Register of Cancer in Children and Young People.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The YSRCCYP has ethical approval from the Northern and Yorkshire Research Ethics Committee (MREC/00/03/001) and approval for holding identifiable patient data from the National Information Governance Board for Health and Social Care under section 251 of the NHS Act (2006).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data from the YSRCCYP are not publicly available. The data supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article.

References

- 1. Office for National Statistics. Measuring equality: a guide for the collection and classification of ethnic group, national identity and religion data in the UK. London, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Executive NHS. Collection of ethnic group data for admitted patients (EL/94/77) Executive NHS. Leeds, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Aspinall PJ. The mandatory collection of data on ethnic group of inpatients: experience of NHS trusts in England in the first reporting years. Public Health 2000;114:254–9. 10.1016/S0033-3506(00)00340-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mathur R, Bhaskaran K, Chaturvedi N, et al. . Completeness and usability of ethnicity data in UK-based primary care and hospital databases. J Public Health 2014;36:684–92. 10.1093/pubmed/fdt116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Health and Social Care Information Centre. How good is HES ethnicity coding and where do the problems lie?. 2004.

- 6. Saunders CL, Abel GA, El Turabi A, et al. . Accuracy of routinely recorded ethnic group information compared with self-reported ethnicity: evidence from the English Cancer Patient Experience survey. BMJ Open 2013;3:e002882 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mateos P. A review of name-based ethnicity classification methods and their potential in population studies. Popul Space Place 2007;13:243–63. 10.1002/psp.457 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bhopal R. Glossary of terms relating to ethnicity and race: for reflection and debate. J Epidemiol Community Health 2004;58:441–5. 10.1136/jech.2003.013466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Office for National Statistics. Ethnicity and National Identity in England and Wales 2011. London 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cummins C, Winter H, Cheng KK, et al. . An assessment of the Nam Pehchan computer program for the identification of names of south Asian ethnic origin. J Public Health Med 1999;21:401–6. 10.1093/pubmed/21.4.401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nanchahal K, Mangtani P, Alston M, et al. . Development and validation of a computerized South Asian Names and Group Recognition Algorithm (SANGRA) for use in British health-related studies. J Public Health Med 2001;23:278–85. 10.1093/pubmed/23.4.278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. OnoMAP. http://www.onomap.org/ (accessed Aug 2015).

- 13. Mateos P, Longley PA, O’Sullivan D. Ethnicity and population structure in personal naming networks. PLoS One 2011;6:e22943 10.1371/journal.pone.0022943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lakha F, Gorman DR, Mateos P. Name analysis to classify populations by ethnicity in public health: validation of Onomap in Scotland. Public Health 2011;125:688–96. 10.1016/j.puhe.2011.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ryan R, Vernon S, Lawrence G, et al. . Use of name recognition software, census data and multiple imputation to predict missing data on ethnicity: application to cancer registry records. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2012;12:3 10.1186/1472-6947-12-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. van Laar M, McKinney PA, Parslow RC, et al. . Cancer incidence among the south Asian and non-south Asian population under 30 years of age in Yorkshire, UK. Br J Cancer 2010;103:1448–52. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Steliarova-Foucher E, Stiller C, Lacour B, et al. . International Classification of Childhood Cancer, third edition. Cancer 2005;103:1457–67. 10.1002/cncr.20910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. NHS Digital. Hospital Episode Statistics. http://content.digital.nhs.uk/hes (accessed Nov 2016).

- 19. Health and Social Care Information Centre. HES Data Dictionary: Admitted Patient Care (APC) Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) Data Dictionary. 2016.

- 20. Downing A, West RM, Gilthorpe MS, et al. . Using routinely collected health data to investigate the association between ethnicity and breast cancer incidence and survival: what is the impact of missing data and multiple ethnicities? Ethn Health 2011;16:201–12. 10.1080/13557858.2011.561301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. National Cancer Intelligence Network. Cancer Incidence and Survival By Major Ethnic Group, England, 2002 - 2006. 2009.

- 22. Rees P, Wohland P, Norman P, et al. . A local analysis of ethnic group population trends and projections for the UK. J Popul Res 2011;28:149–83. 10.1007/s12546-011-9047-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lomax N, Norman P. Estimating Population Attribute Values in a Table: “Get Me Started in” Iterative Proportional Fitting. The Professional Geographer 2016;68:451–61. 10.1080/00330124.2015.1099449 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Norman P, Simpson L, Sabater A. ‘Estimating with Confidence’ and hindsight: new UK small-area population estimates for 1991. Popul Space Place 2008;14:449–72. 10.1002/psp.492 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Aspinall PJ, Jacobson B. Why poor quality of ethnicity data should not preclude its use for identifying disparities in health and healthcare. Qual Saf Health Care 2007;16:176–80. 10.1136/qshc.2006.019059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cummins C, Winter H, Maric R, et al. . Childhood cancer in the south Asian population of England (1990-1992). Br J Cancer 2001;84:1215–8. 10.1054/bjoc.2001.1775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sayeed S, Barnes I, Cairns BJ, et al. . Childhood cancer incidence in British Indians & Whites in Leicester, 1996-2008. PLoS One 2013;8:e61881 10.1371/journal.pone.0061881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Powell JE, Parkes SE, Cameron AH, et al. . Is the risk of cancer increased in Asians living in the UK? Arch Dis Child 1994;71:398–403. 10.1136/adc.71.5.398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. McKinney PA, Feltbower RG, Parslow RC, et al. . Patterns of childhood cancer by ethnic group in Bradford, UK 1974-1997. Eur J Cancer 2003;39:92–7. 10.1016/S0959-8049(02)00488-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Winter H, Cheng KK, Cummins C, et al. . Cancer incidence in the south Asian population of England (1990-92). Br J Cancer 1999;79:645–54. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Morris M, Woods LM, Rogers N, et al. . Ethnicity, deprivation and screening: survival from breast cancer among screening-eligible women in the West Midlands diagnosed from 1989 to 2011. Br J Cancer 2015;113:548–55. 10.1038/bjc.2015.204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Aspinall PJ. The utility and validity for public health of ethnicity categorization in the 1991, 2001 and 2011 British Censuses. Public Health 2011;125:680–7. 10.1016/j.puhe.2011.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Simpson L, Warren J, Jivraj S. Do people change their ethnicity over time ethnic identity and inequalities in Britain. Bristol: The dynamics of diversity Policy Press, 2015:79–92. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Brant LJ, Boxall E. The problem with using computer programmes to assign ethnicity: immigration decreases sensitivity. Public Health 2009;123:316–20. 10.1016/j.puhe.2009.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Iqbal G, Gumber A, Johnson MR, et al. . Improving ethnicity data collection for health statistics in the UK. Diversity in Health & Care 2009;6. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Office for National Statistics. Census gives insights into characteristics of Yorkshire and the Humber’s population. London: 2012. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2017-016332supp001.pdf (10KB, pdf)